1. Introduction

The B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) protein family plays a vital role in apoptosis regulation by controlling the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria. Hence, it could affect cell survival and death pathways[

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. In place of an anti-apoptotic protein, BCL-2 inhibits programmed cell death, which means its dysregulation is associated with various cancers, such as breast cancer, lung cancer and leukemia. In fact, promoting the survival of malignant cells induces treatment resistance [

6,

7,

8]. For instance, BCL2 upregulation in both chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a hallmark for disease progression and treatment response [

9]. Additionally, BCL-2 upregulation disrupts the apoptotic balance. Subsequently, therapeutic resistance develops, underscoring the need for targeted inhibition to achieve better mediating outcomes [

10,

11].

The first selective BCL2 inhibitor, ABT-199 (venetoclax), was introduced in 2013 [

12]. Venetoclax is a selective BCL-2 inhibitor approved in 2016 for relapsed or refractory CLL. Ever since, the usage of this drug has been expanded as the first-line treatment along with hypomethylating agents for AML patients [

13,

14,

15]. Venetoclax induces apoptosis in cancer cells through binding to the BH3 site of BCL-2. This attachment interrupts BCL-2 interactions with BAX and BAK, which are pro-apoptotic proteins [

16]. Clinical trials have demonstrated greater efficacy in achieving deep remissions in CLL and an overall survival benefit in AML, especially in elderly or unfit patients [

17]. A notable challenge in the venetoclax-treated patients is the development of acquired resistance driven by BCL-2 mutations. For example, the G101V mutation in BCL-2 decreases binding affinity, as reported in hematologic cancers. Around 30% of venetoclax-relapsed CLL patients have this mutation [

18]. Researchers also propose the same pattern in breast cancer, promoting a heterogeneous genome. This underscores the need to discover novel BCL-2 inhibitors [

12,

19,

20].

The second-generation of BCL-2 inhibitors is Sonrotoclax (BGB-11417). It performs as an effective and selective one due to its functionality for both wild-type (WT) and G101V-mutated BCL-2. Additionally, in preclinical models and ongoing trials, Sonrotoclax overcomes venetoclax resistance. To this end, it could be an outstanding option for BCL-2-responsive solid tumors and other varieties of malignancies [

21,

22,

23]. Moreover, the cooperation of Sonrotoclax with Zanubrutinib determines enhanced potency, selectivity, and tolerability of CLL, AML, and other B-cell malignancies. This result has been reported from phase 1/2 clinical trials, with early data showing considerable undetectable minimal residual disease (MRD) [

24,

25]. The latest 2025 studies have drawn attention to Sonrotoclax's capability to synergize with radiotherapy in solid tumors. This could occur as a result of non-apoptotic BCL-2 functions, thereby increasing anti-tumor immune responses [

26].

However, while preclinical data demonstrates that Sonrotoclax potently inhibits BCL-2 G101V, the structural and dynamic basis for its ability to overcome a mutation that so drastically disrupts venetoclax binding remains unclear. It could achieve this through superior affinity for the distorted groove, or through a fundamentally different mechanism of inhibition.

In the structural aspect, Venetoclax and Sonrotoclax function as BH3 mimetics that bind to the hydrophobic BH3-binding groove of BCL-2, which is a flexible region containing four subsites (P1-P4) formed with alpha-helices 2-5 [

27]. Venetoclax resides in the P2 and P4 pockets using its chlorophenyl and azaindole moieties. Subsequently, it creates vital hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions with residues such as Asp103, Arg146, and Phe104, implying pro-apoptotic partners [

12]. Sonrotoclax binds to BCL2 with higher affinity than venetoclax, caused by a different binding mode within the P2 pocket [

28]. Sonrotoclax, with a modified scaffold, was designed to target the P2 pocket via additional Π-stacking with Trp188 and tighter packing in the P4 subsite, interactions that are well-defined in static crystal structures. However, the stability of these specific contacts under the dynamic perturbations of the G101V mutation remains to be fully characterized in solution Consequently, it has 10- to 100-fold higher affinity [

29]. Mutations like G101V propose a bulkier valine side chain at the edge of the P4 pocket, triggering a steric clash that displaces Glu152. In addition, it disrupts the hydrogen-bond network, which is pivotal for venetoclax binding, resulting in a decrease in affinity by over 180-fold [

21]. In contrast, Sonrotoclax's optimized geometry accommodates this alteration, maintaining potent inhibition through forming alternative contacts, hence from crystal structures (PDB: 8HOH) [

28]. Such mutations induce conformational shifts in the BH3 groove, boosting flexibility and solvent exposure, which could propagate to adjacent helices and impair overall anti-apoptotic function, thereby conferring drug resistance [

16].

Furthermore, developing a new drug is an expensive and time-consuming procedure. Although for a novel medicine announcement, usually more than 14 years and 2.6 billion dollars are required [

30]. In silico dysfunctionality interpretation of discovered drugs would be a strategic solution for the high rate of cancer mortality and the slow drug development. In fact, this method could be a notable time- and budget-saver. The breakthroughs in computational methods have revolutionized drug discovery, especially in virtual screening. Remarkably, traditional molecular docking is mostly ineffective at capturing the dynamic nature of proteins. Methodological advances have enabled the detailed characterization of protein-ligand interactions from multiple dimensions. For example, several methods could be applied, ranging from quantum-mechanical calculations to thermodynamic stability and dynamics assessments, to time-resolved trajectory analyses. Meanwhile, for the oncotherapy target, the BCL-2-BH4 domain, many studies have employed virtual screening to identify small molecules. As a result, they were able to predict its activity and the origin of cell death in tumor cells [

31,

32].

This study performs computational methods to distinguish the binding dynamics of Venetoclax and Sonrotoclax to BCL-2 WT and G101V forms. Primary structures were generated via AlphaFold for prediction [

25]. Afterwards, molecular dynamics simulations (MDS), docking, and analyses such as root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF), buried surface area (BSA), protein-ligand interaction fingerprint (ProLIF), and MM/GBSA binding free energies were performed. Crystal structures of BCL-2 G101V with venetoclax (PDB: 6O0L) and Sonrotoclax (PDB: 8HOH) served as benchmarks. Therefore, the primary purpose of these investigations is to determine whether Sonrotoclax overcomes resistance by establishing a more stable canonical binding mode or by employing a novel, dynamic mechanism of inhibition. At the end, all this data would suggest strategies to combat BCL-2 inhibitor resistance.

2. Results

For each system, the energy and equilibration analyses were initially performed to validate the simulations. The energy and equilibration analyses include total energy, temperature, pressure, box dimensions, and volume. Next, the pocket residues were identified in each system within 5 Å of the ligand. The RMSD was calculated for the ligand and the pocket residues. The RMSF was determined for the ligand and the entire protein, with pocket residues marked. Additionally, the BSA analysis was calculated using the following formula:

State-resolved was evaluated by monitoring the center-of-mass (COM) distance, minimum heavy-atom distance, protein–ligand contacts, and hydrogen bonds throughout the simulation. All the factors were calculated between ligand and pocket, and also ligand and the backbone atoms of the protein to reveal whether or not the ligand is fully unbound, has a weak bonding, or has bound on the surface of the protein (not the BH3 pocket). A ligand was considered “BH3-bound” when the COM distance < 1.0 nm AND contacts >= 3 AND at least one key interaction (H-bond/salt bridge to BH3 core residues). It falls under the “weakly-bound” category when the minimum distance is < 0.5 nm, OR it shows intermittent contacts. It is regarded as “surface-bound” when the COM distance < 2.0 nm, AND Contacts >= 1, AND NOT meeting BH3 criteria. Finally, it is considered “unbound” when the COM distance > 2.5 nm AND Minimum distance > 1.0 nm AND Contacts == 0. If the ligand and protein do not fall under any of the mentioned groups, it is noted as “Ambig”.

In the next step, per-residue interaction occupancies were computed using the protein ligand interaction fingerprint (ProLIF), restricting the analysis to frames classified as BH3-bound and non-BH3-bound by our distance/contacts criteria. Tables for each run are available in the Supplementary file.

Finally, the MM/GBSA binding free energy analysis was calculated after excluding the unbound frames according to the criteria we introduced, using the following formula [

47,

48]:

The MM/GBSA was measured for the 3*1501 frames across all four systems from frame 500 to 2001. The first 499 frames of each run were excluded since the systems are just getting equilibrated at the first 50 ns of the simulations.

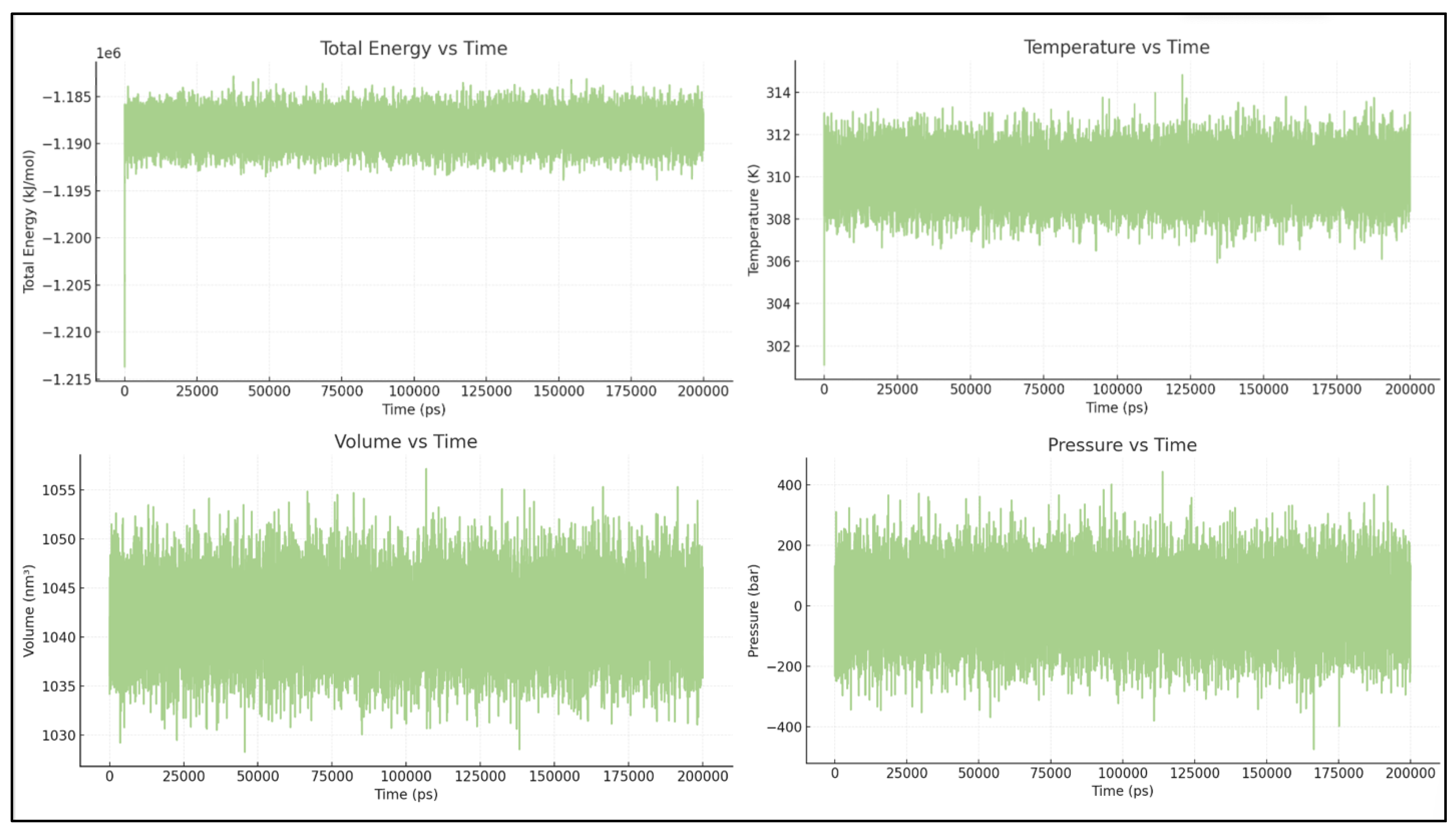

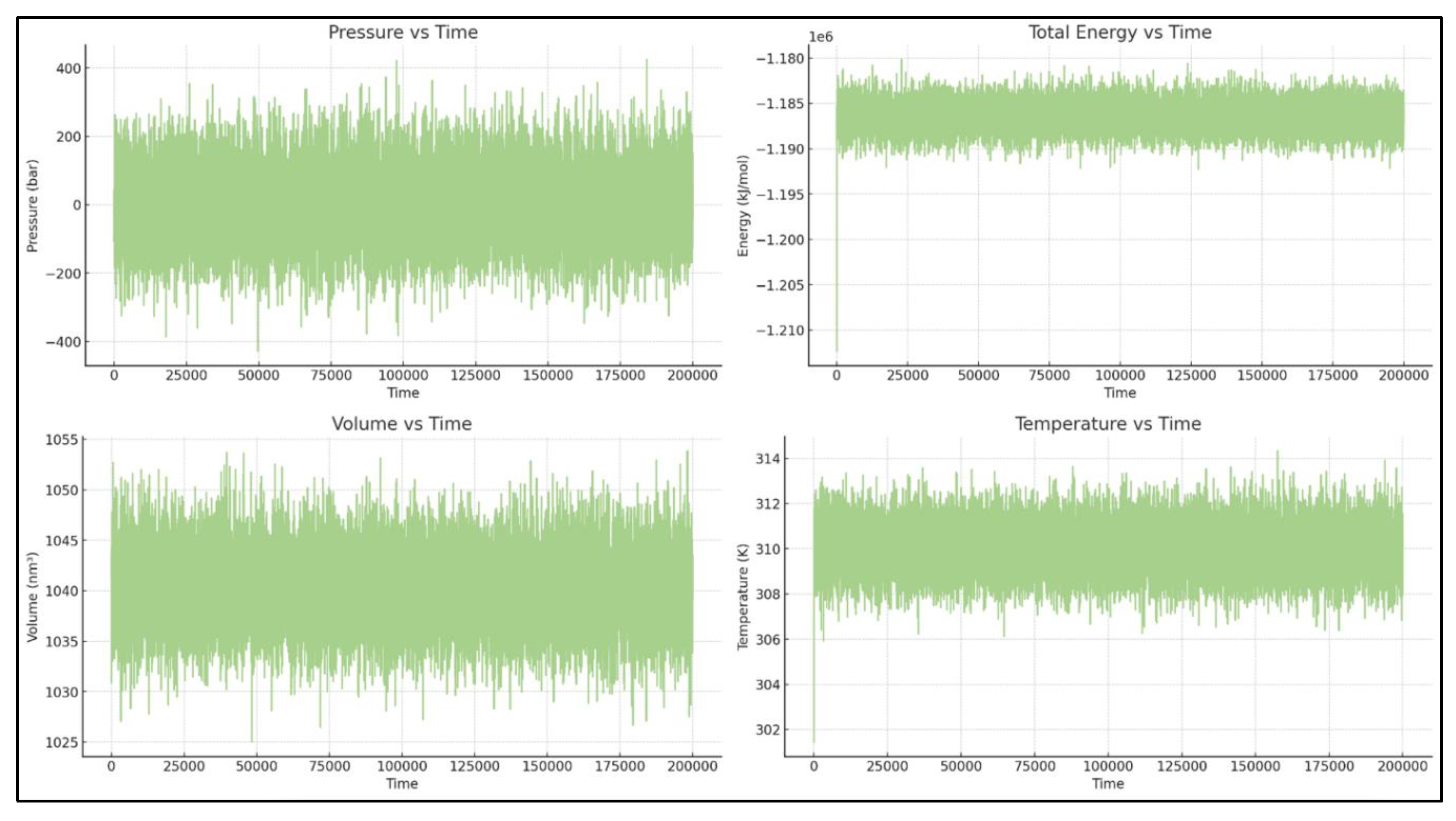

2.1. BCL2-WT Bound to Venetoclax

The simulation conditions, including temperature, total energy, and volume, are well-controlled. The only significant fluctuation is in pressure, which is expected for NPT simulations over short timescales. [See

Figure 1]

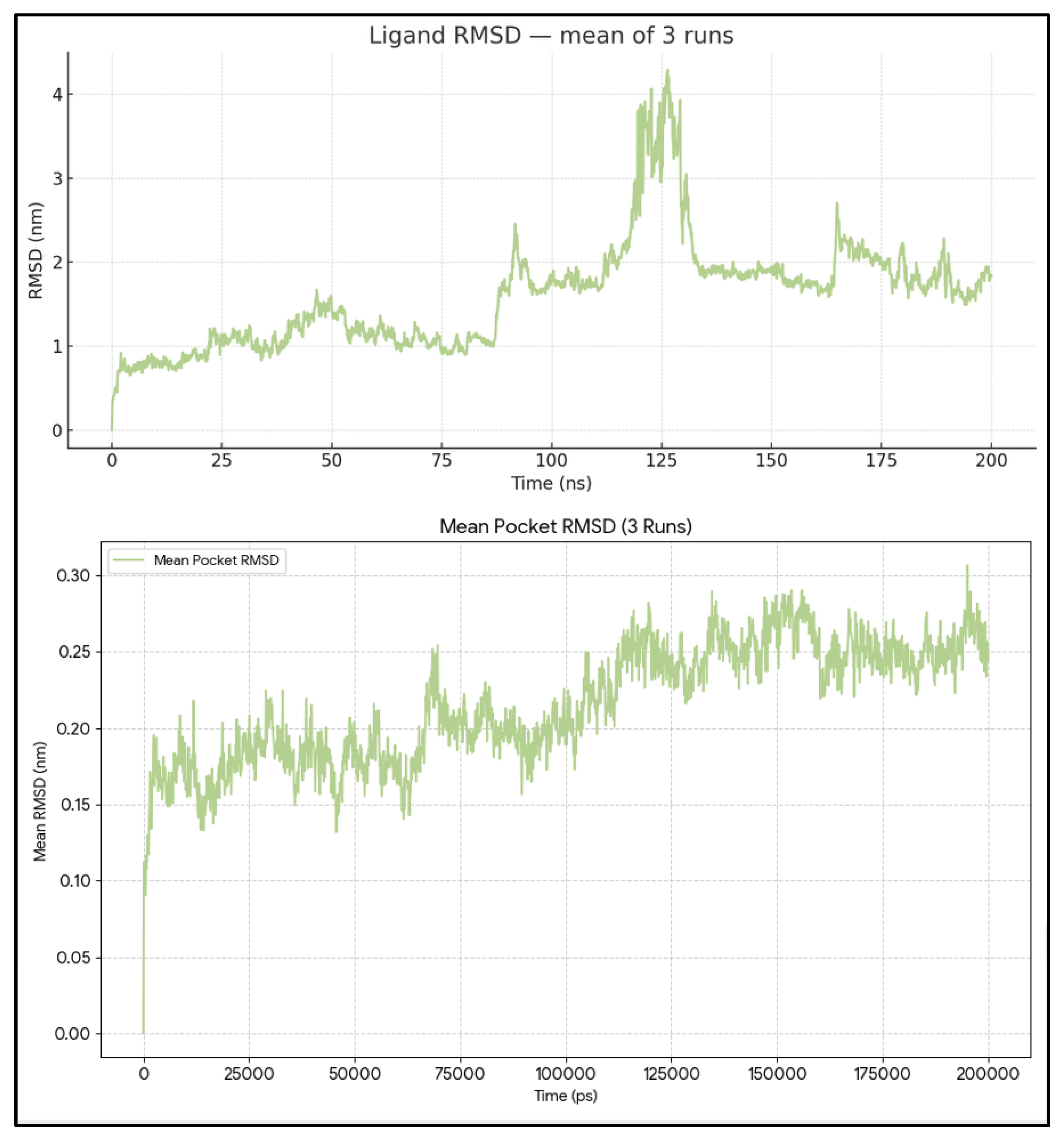

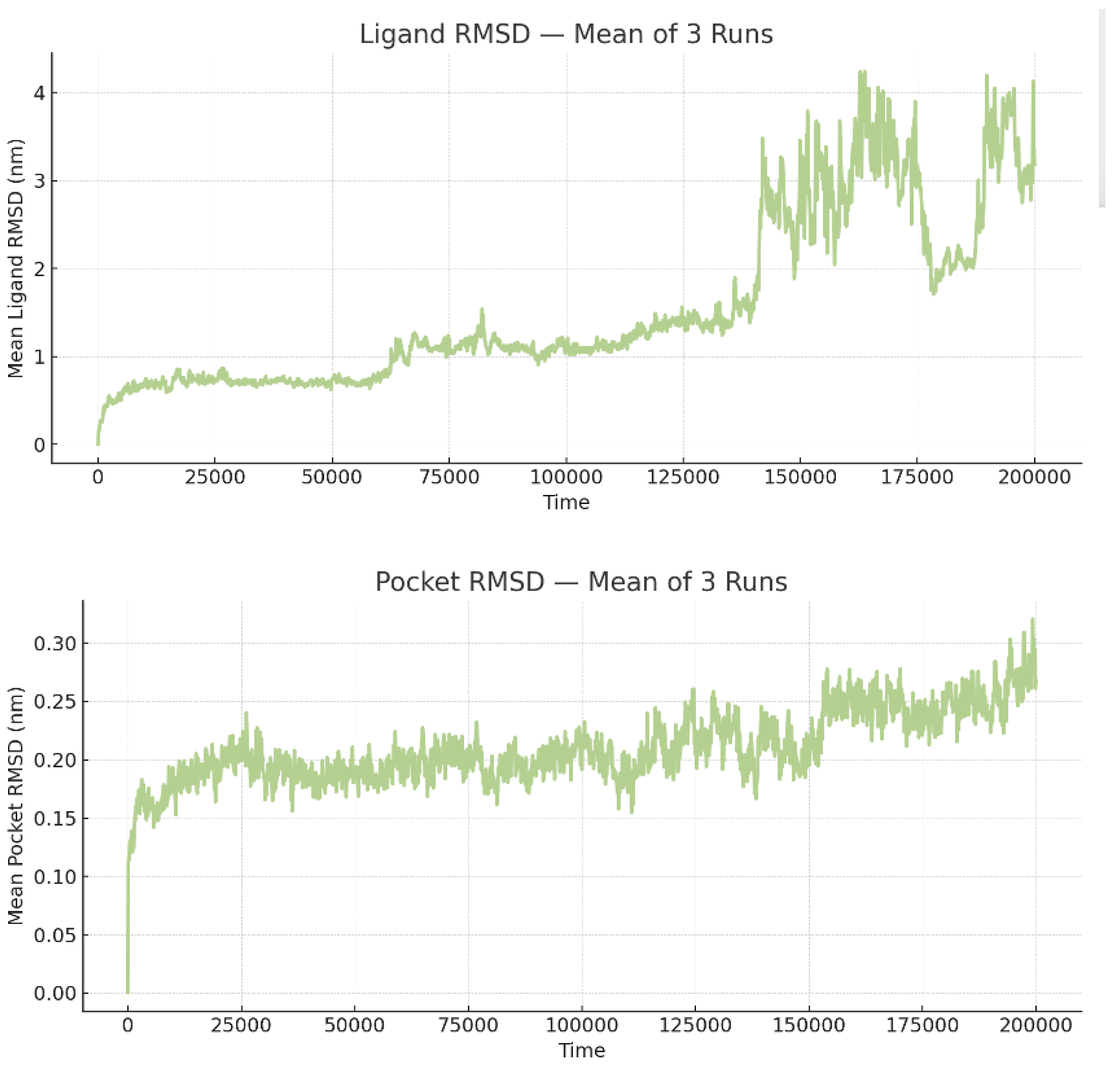

The RMSD of the pocket is relatively low and stable without extreme spikes. Most fluctuations in the pocket RMSD range from 0.0 nm to ~0.3 nm (Mean = 0.21 ± 0.3 nm). The minor fluctuations are likely due to regular protein-breathing motions rather than compromising the overall integrity of the binding site.

The ligand RMSD shows some variability. Across 3 independent simulations, the ligand RMSD averaged 1.60 ± 0.78 nm (mean ± SD), with values ranging from 0.00 to 7.97 nm. The averaged profile shows three regimes. During 0–90 ns, the ligand remains compact, with a mean RMSD of ~1.0–1.2 nm and most values <~1.5 nm, showing a slight positive drift, consistent with local relaxation around the docked pose. Between ~90–140 ns, the mean exhibits a sharp escalation culminating in a global peak around ~125 ns, which is due to the heterogeneous behavior among replicates (one run samples a high-RMSD excursion up to ~8 nm, another sits on a mid-RMSD plateau around ~3 nm, while the third stays near ~1 nm). After ~140 ns, the mean re-equilibrates to ~1.7–2.0 nm with reduced, though non-negligible, fluctuations, suggesting the system settles into a more displaced binding mode than at the start (

Figure 2).

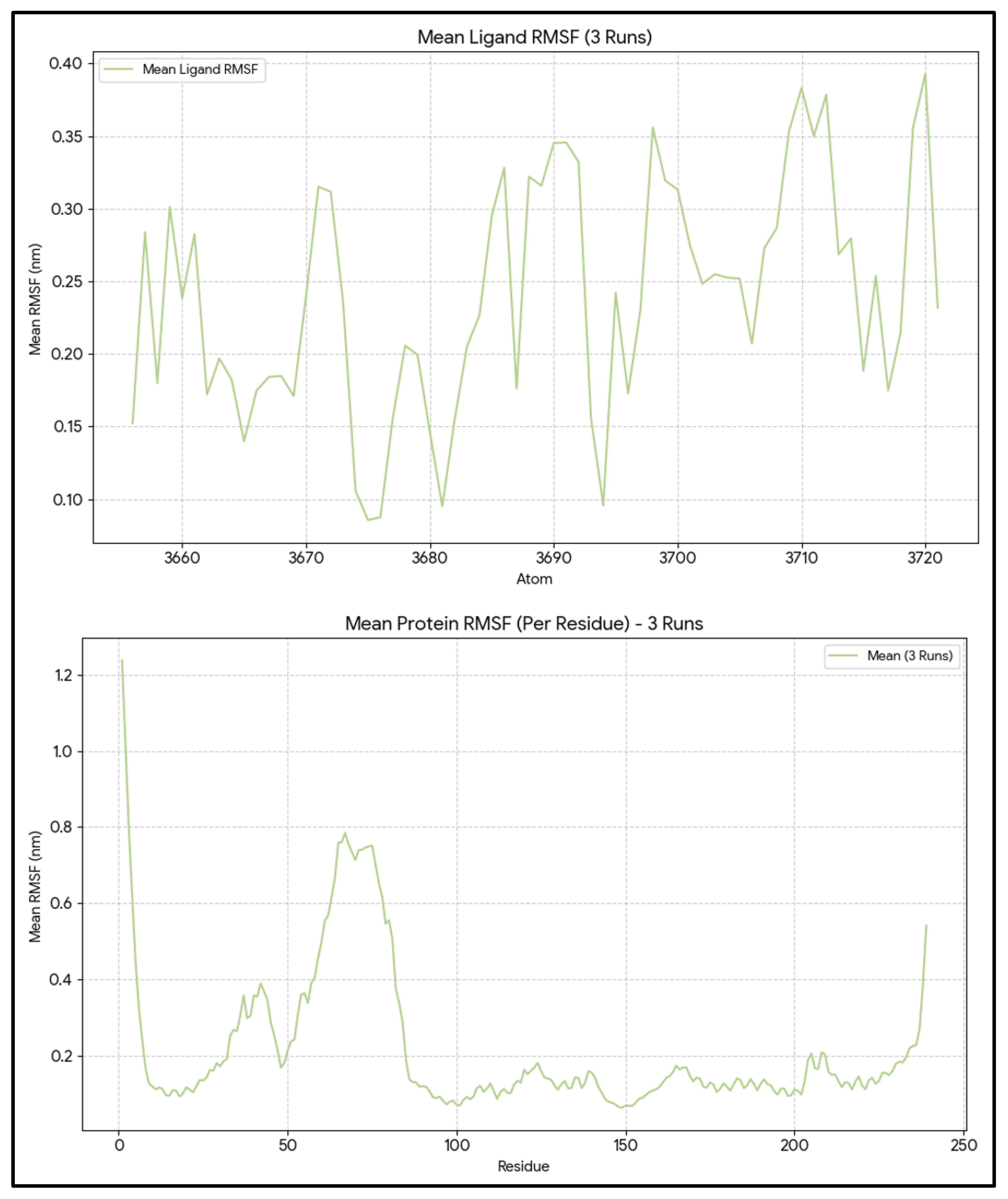

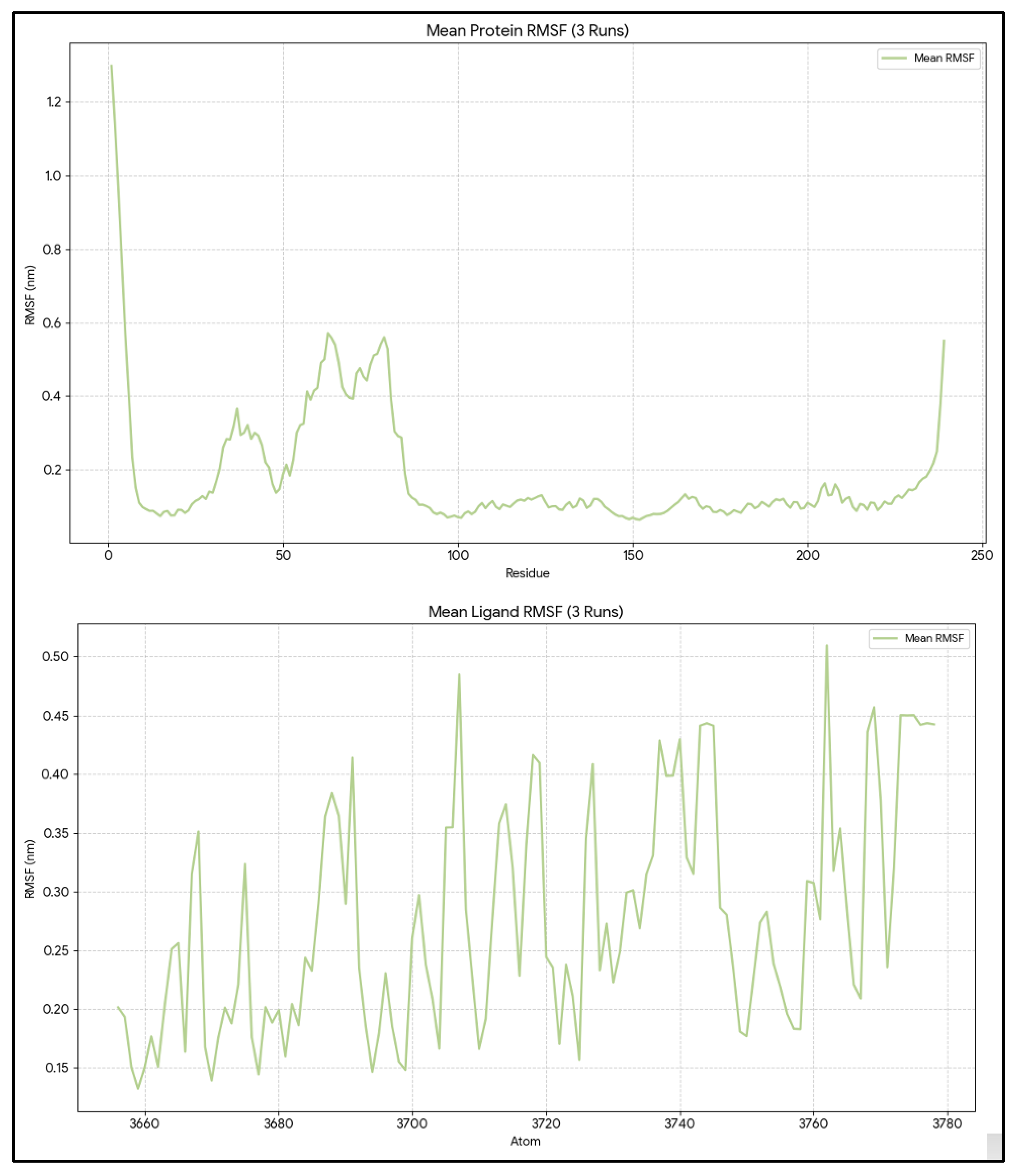

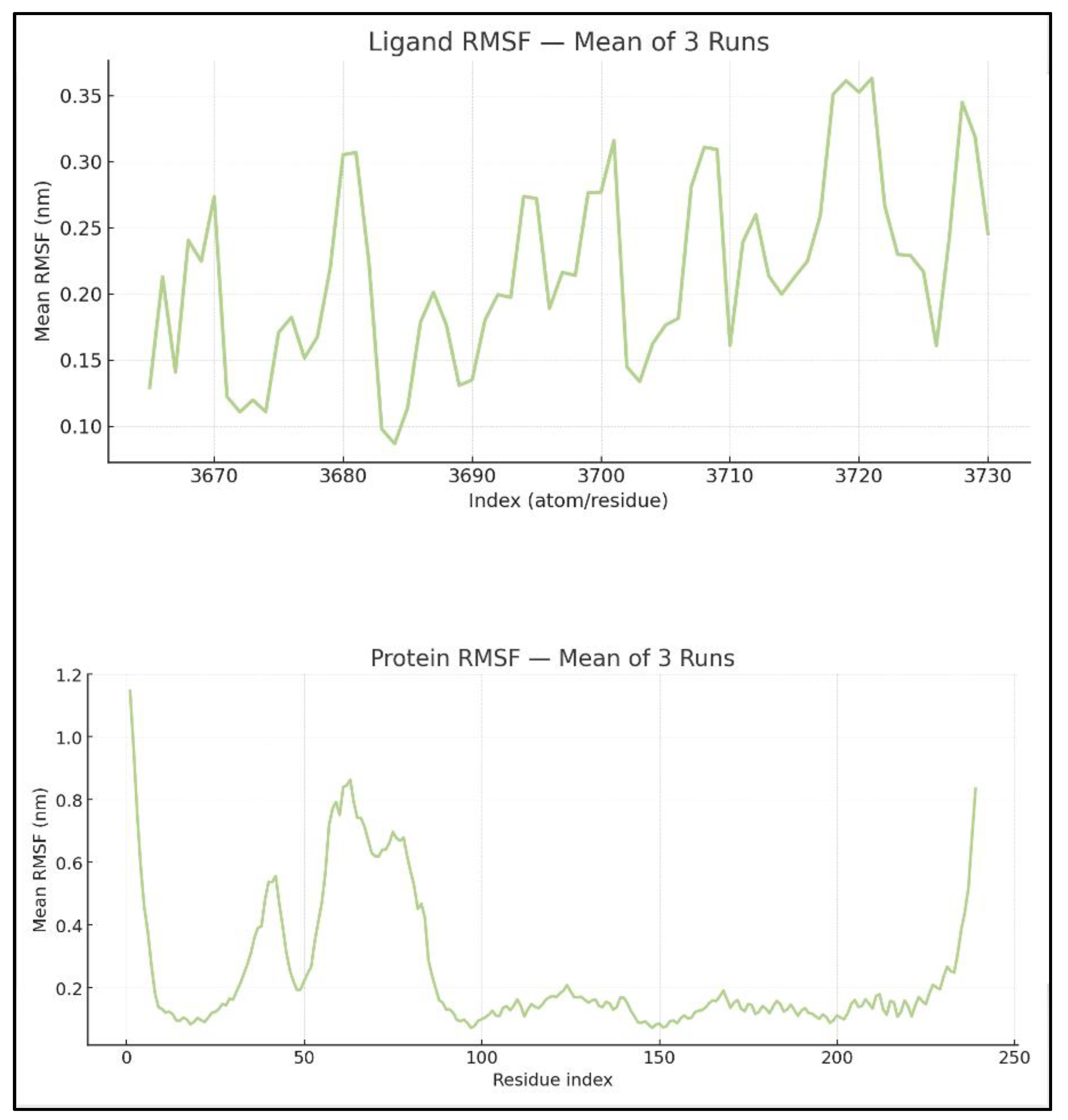

The mean RMSF for 239 protein residues was 0.22 ± 0.01 nm, with values ranging from 0.05 to 1.29 nm (

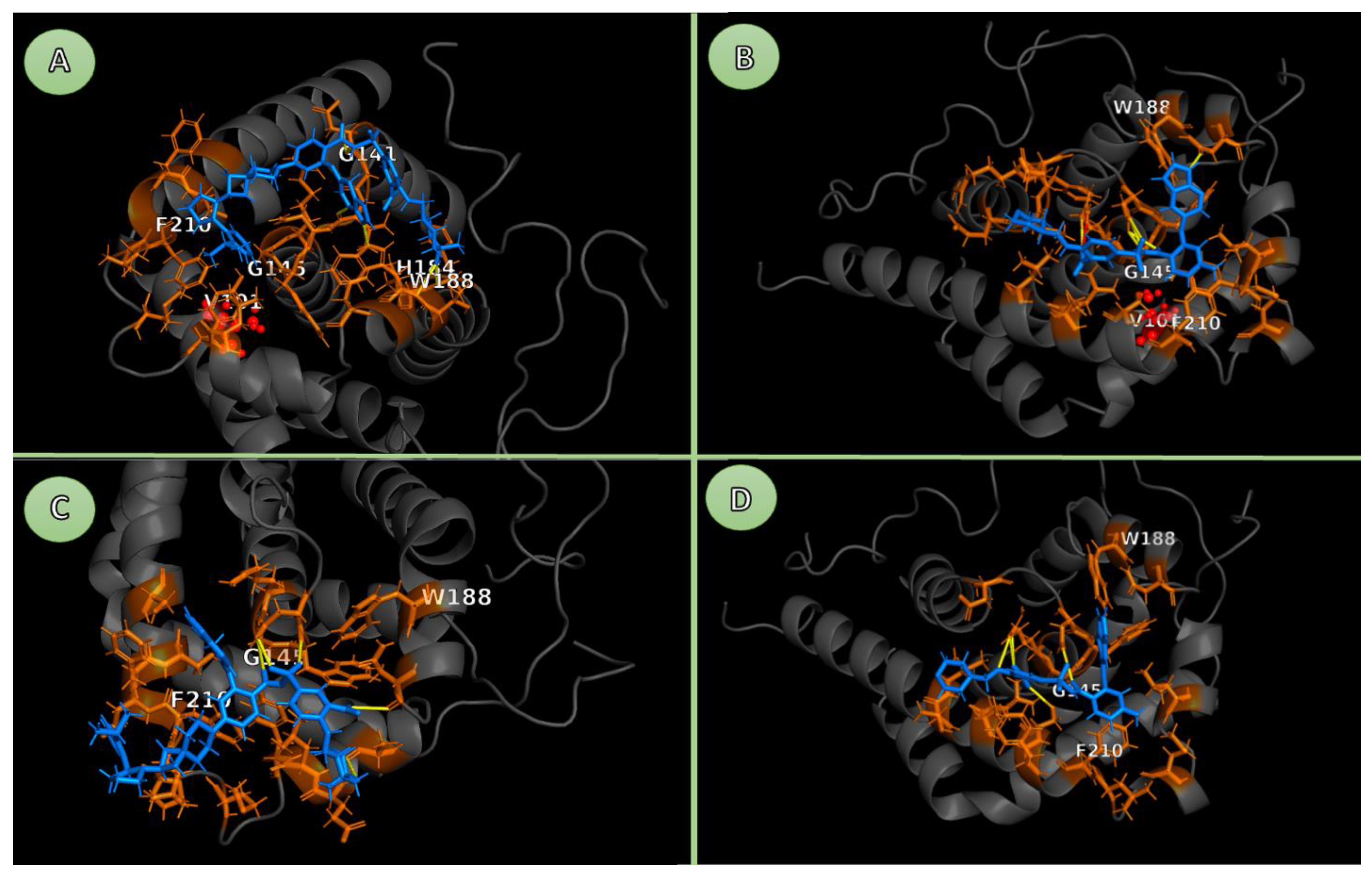

Figure 3). The mean RMSF for residues in the pocket, selected within 5 Å of the ligand (residue numbers: 140, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 188, 192, 201, 202, 206, 209, 210, 212, 213, 215, 216, 217, 219, 220, 223), was 0.12 ± 0.03 nm (minimum = 0.07 nm and maximum = 0.20 nm), indicating that the pocket residues are more rigid than the rest of the protein. This pattern is typical of a well-formed groove designed to contain a bulky ligand such as venetoclax. The ligand RMSF averaged 0.24 ± 0.01 nm, with values ranging from 0.08 to 0.43 nm. By aligning the ligand_rmsf.xvg file with the .gro file of the complex and the ligand_SASA. In the xvg file, it was shown that the atoms with the highest RMSF are mostly on the periphery of the ligand rather than in its compact core. The flexibility of the peripheral ligand, combined with the rigidity of the protein pocket, except for a few edge residues with elevated RMSF, supports a stable, well-packed complex that allows limited local rearrangement rather than extensive disruption of the binding site.

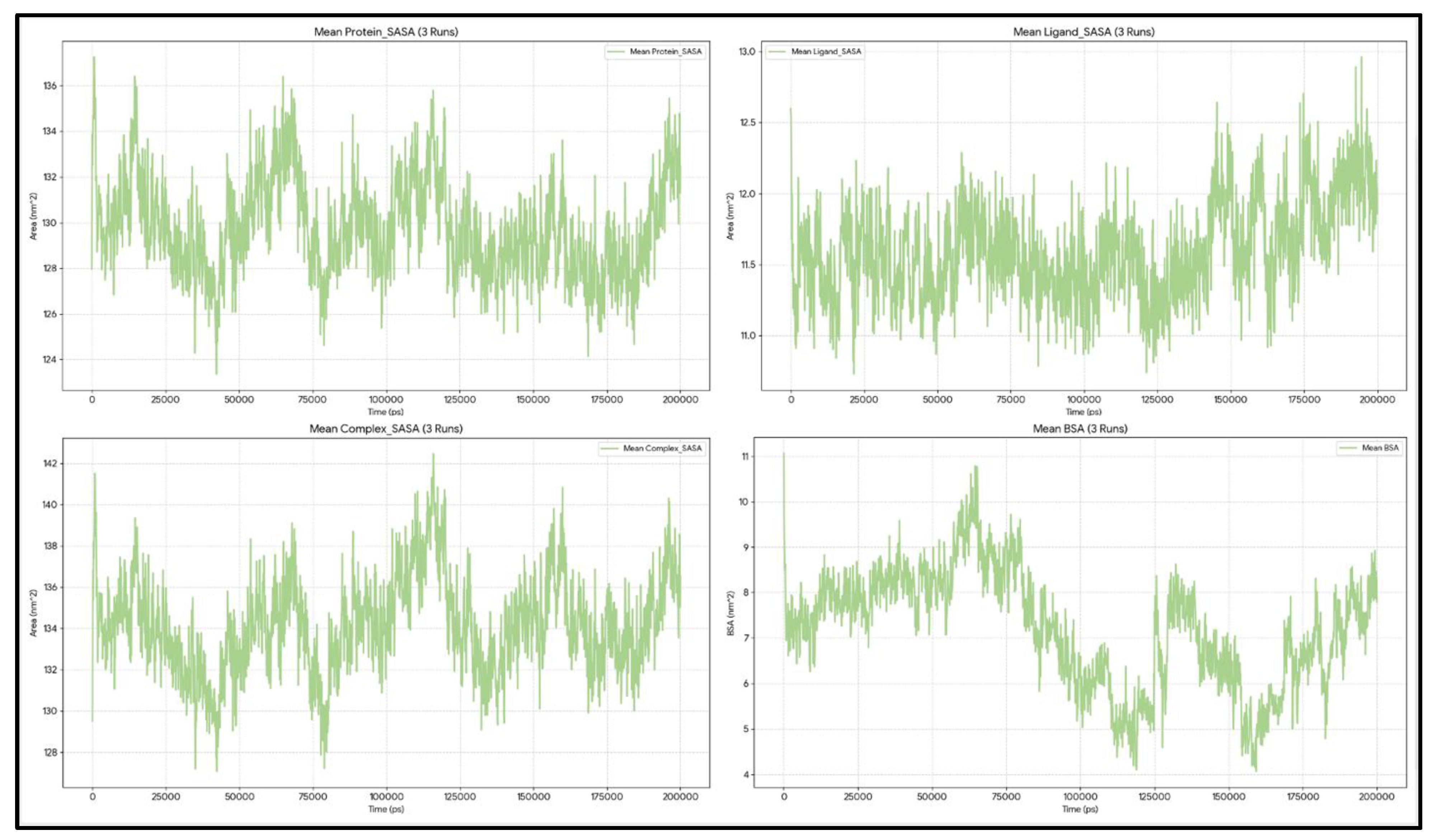

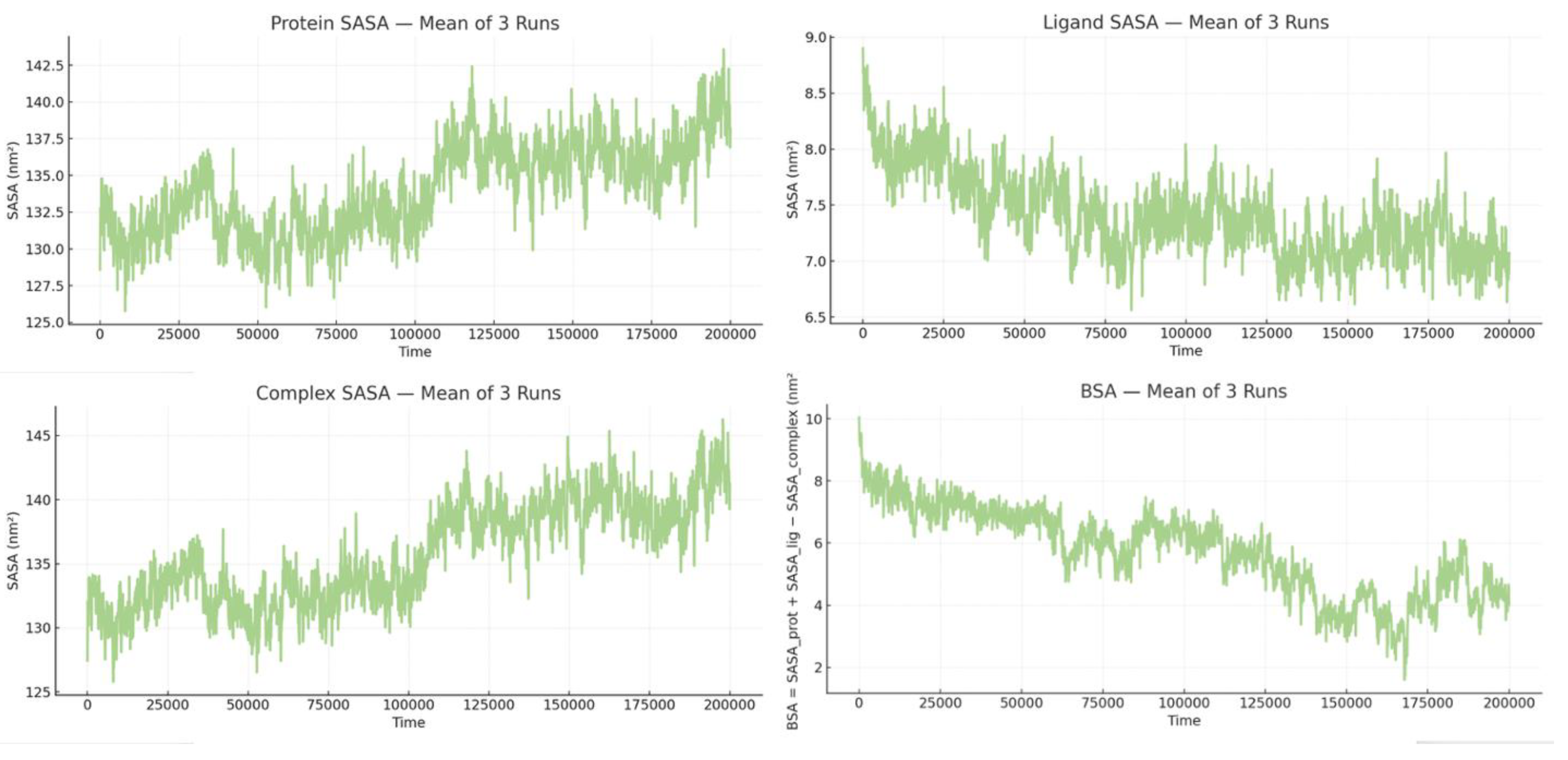

The average protein SASA across the three independent runs is 130.98 nm², with a standard deviation (SD) of 2.26 nm². The minimum and maximum SASA of the protein across all frames are 117.25 and 151.44 nm², respectively (

Figure 4).

The ligand SASA is generally stable around 8.19 ± 0.14 nm². The minimum SASA of Venetoclax observed across all simulations is ~6.46 nm², and the maximum SASA of the ligand is ~9.40 nm². Moreover, the ligand linear slope was ~−0.0 nm²/ns.

The ligand and protein (referred to as the complex) SASA during the 6003 frames of the work was, on average, ~133.14 nm² with an SD of ~2.26. The minimum SASA of the complex across all runs occurred at ~94.5 ns with a value of ~119.36 nm², and the maximum reached ~152.53 nm² at ~171.0 ns.

Taken together, the average BSA over 600 ns was 6.03 ± 1.81 nm², with minimum and maximum values of approximately 0.0 and 11.61 nm², respectively. The statistics indicate that the interface is primarily well-formed. The BSA exceeds 6 nm² in about 56% of frames, demonstrating strong burial. In roughly 38% of frames, the BSA is between 3 and 6 nm², and in about 5% of frames, it is less than 3 nm². From 0 to 50 ns, the window is the tightest, with a BSA of approximately 5.79 nm², a protein SASA of about 131.02 nm², and a complex SASA of roughly 133.47 nm². During 50–150 ns, burial remains similarly strong, with a BSA around 6.34 nm², a protein SASA near 130.53 nm², and a complex SASA close to 132.43 nm², all at their lowest points. In the final 50 ns (150–200 ns), the window widens, showing a BSA around 5.65 nm², a protein SASA of about 131.85 nm², and a complex SASA approximately 134.25 nm². During this period, a brief opening event occurred at ~164.7 ns, when the BSA decreased to about 3.65 nm² but did not result in disengagement. Notably, the ligand SASA varies minimally across frames (from around 6.5 to 9.4 nm²), indicating that the interface’s looseness or tightness is mainly driven by the protein/pocket conformation, as reflected in the protein/complex SASA.

Analysis of BCL2-WT-venetoclax across three replicates revealed a divergent binding landscape. Two trajectories showed stable, canonical binding with high BH3 occupancy (50.9% and 57.2%), while a third replicate mainly exhibited weak binding (90.6%) with minimal BH3 engagement (7.3%). Despite this, all systems showed dynamic binding, with short-lived BH3 dwell times (1.4-2.2 ns) and rapid state changes. The consistent protein engagement (≤6.4% unbound) across all replicates highlights a stable yet conformationally flexible binding mechanism (

Tables S11-S13 of the Supplementary file).

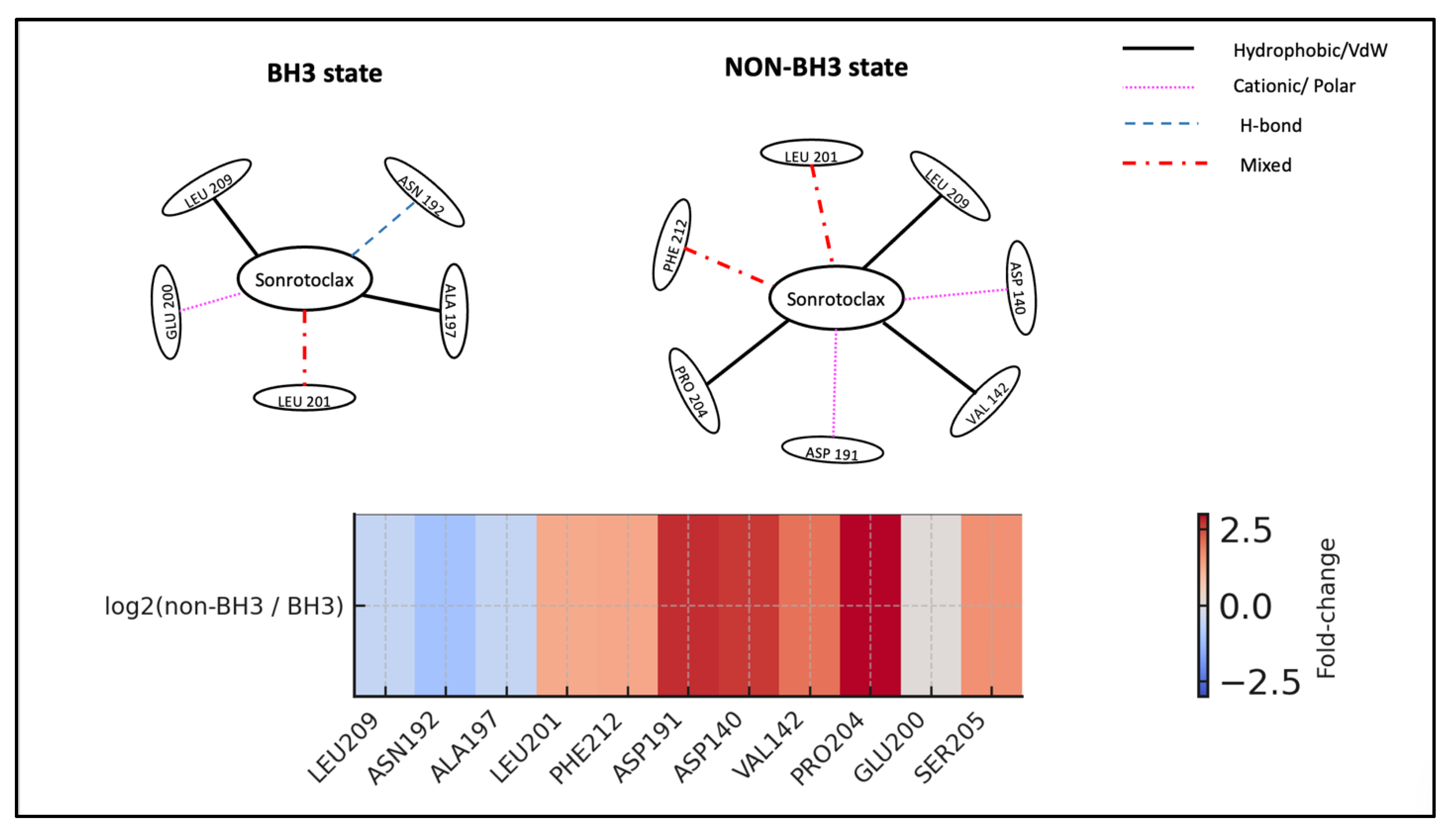

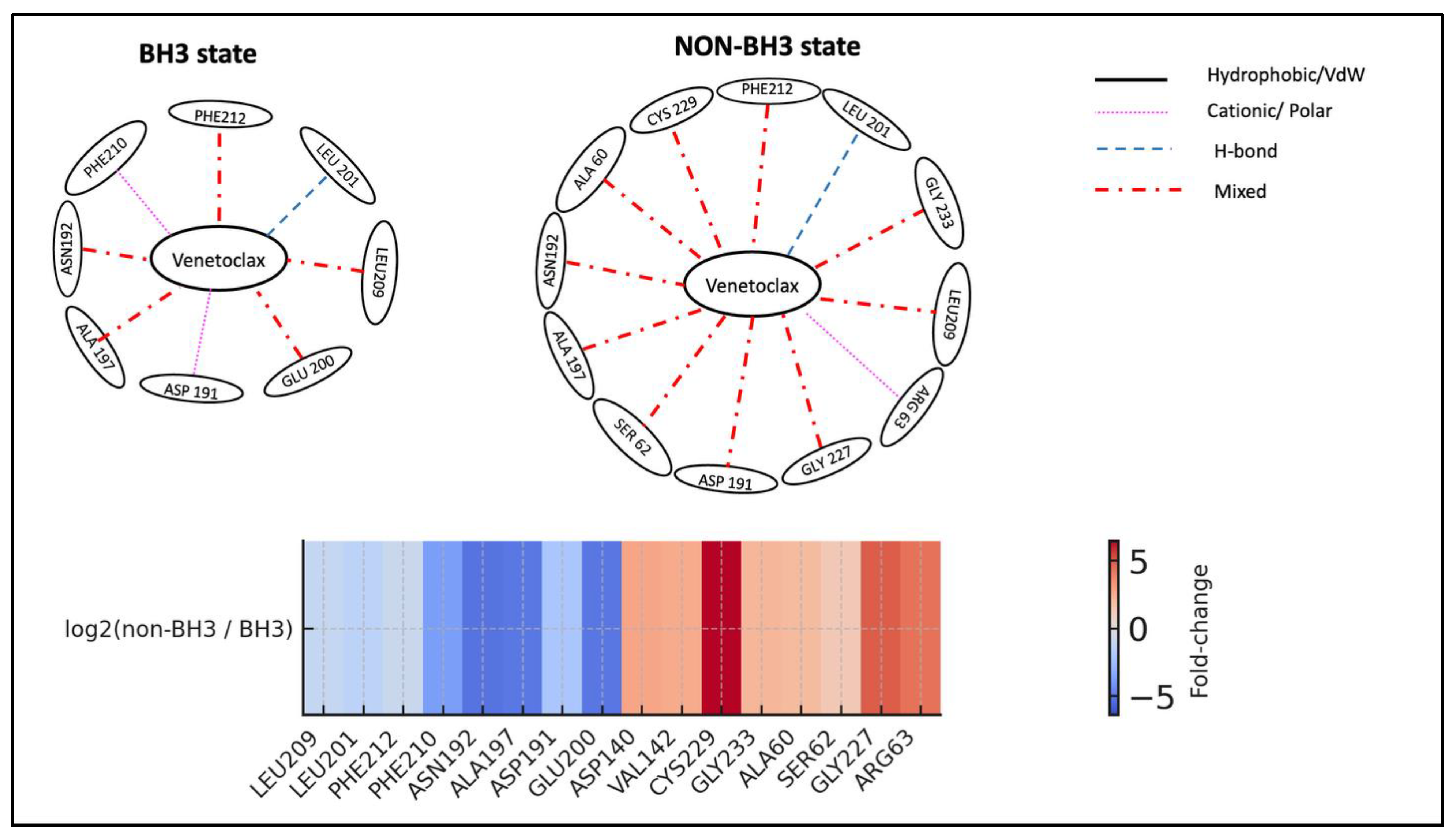

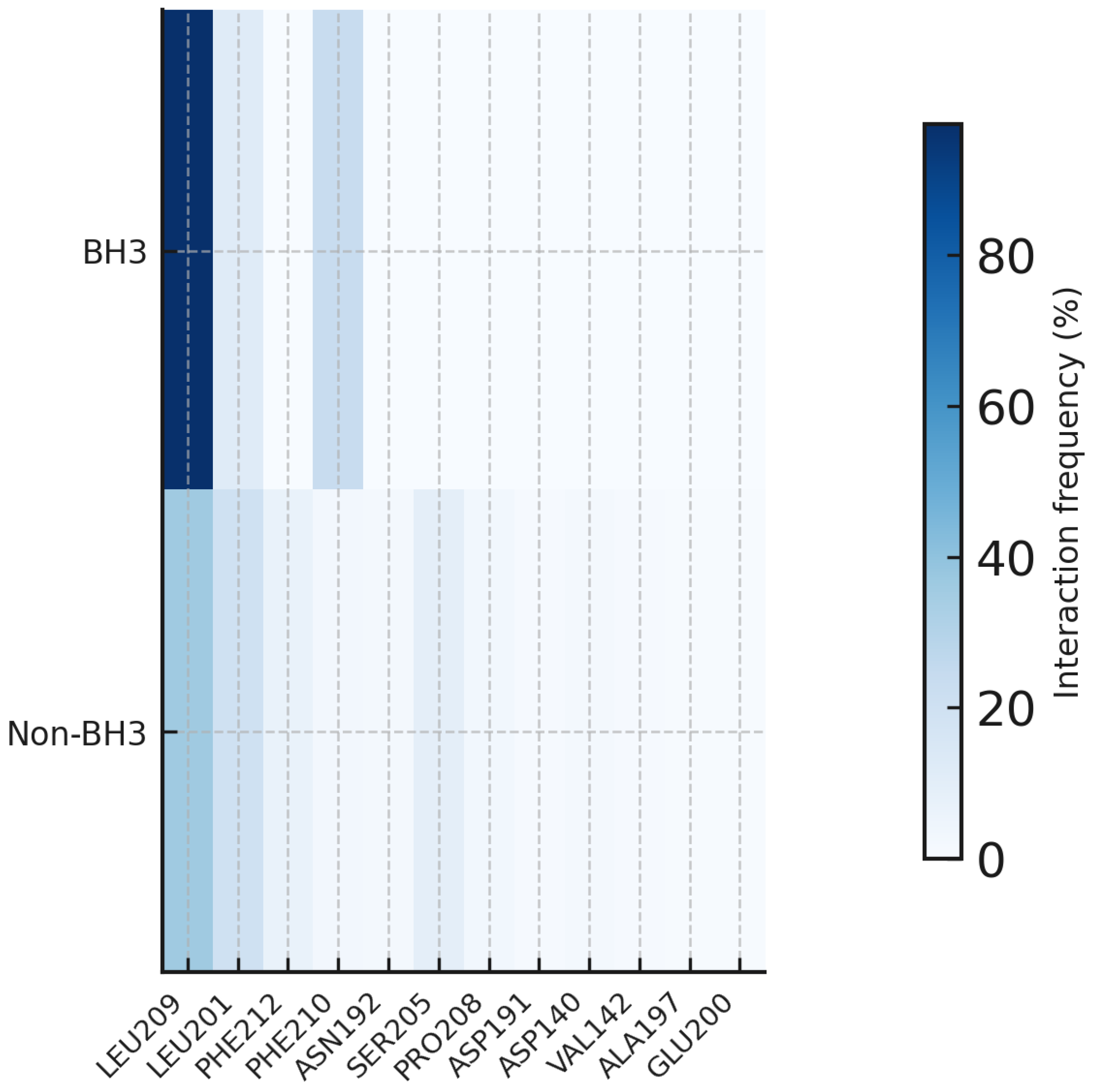

State-resolved interaction fingerprinting revealed that LEU209 serves as the primary anchor for Venetoclax binding to BCL2-WT in both BH3 and non-BH3 states. However, the integrity of this core and its associated network showed notable variability. In replicates with stable BH3 engagement, a consistent hydrophobic core involving LEU201 and PHE212 was observed. Conversely, trajectories with more “weak” states mainly showed a breakdown of this specific network, where LEU209's role is simplified, and contacts spread to more peripheral residues. This indicates that although venetoclax has a clearly defined binding epitope, its effectiveness can be affected by disruptions to key stabilizing interactions that support deep-pocket engagement (

Figure 5) (

Tables S14-S16 of the Supplementary file).

According to the MM/GBSA energy analysis, the overall binding energy is -17.32 ± 9.56 kcal/mol, indicating a favorable interaction between BCL2-WT and Venetoclax (

Table 1). The high SD value shows significant variability across the simulation. The binding is primarily supported by van der Waals (VdW) interactions (-24.80 kcal/mol) and electrostatic interactions (-13.09 kcal/mol), with VdW interactions being more significant. The non-polar solvation energy (ESURF) also provides a small favorable contribution of -3.50 kcal/mol. The main challenge to binding comes from the polar solvation energy, which is 24.07 kcal/mol. This reflects the energy penalty caused by desolvating polar groups on both the ligand and the protein as they bind, removing them from the favorable aqueous environment. The SD of the total binding energy is 9.56 kcal/mol, indicating a high level of dynamism in the interactions. The binding energy is not perfectly stable, suggesting that shifts in ligand pose or protein conformation influence the interaction strength over time. The standard deviations for the VdW (12.37) and Electrostatic (11.00) components are also very significant, further supporting the idea of highly dynamic interactions (

Table 1)

Overall Picture

The collective results from MD simulations provide a comprehensive overview of the BCL2-WT-Venetoclax complex as both a stable and highly dynamic system. The integrity of the binding pocket is maintained throughout, and the ligand persistently resides within the canonical BH3 groove. The observed RMSD and state-residence analyses consistently point to the existence of multiple metastable states, including a tightly bound pose and a more dispersed ensemble. Importantly, major fluctuations are due to in-pocket reorientation and ligand conformational changes, not dissociation. This conclusion is strongly supported by the stable BSA and consistently low ligand solvent exposure.

The dynamic binding equilibrium involves intermittent, high-affinity interactions with the canonical BH3 motif, which is anchored by key hydrophobic residues such as LEU209 and LEU201, with periods of weaker binding occurring within the same groove. This dynamic nature is quantitatively reflected in the MM/GBSA binding free energy, which is, on average, favorable (-17.32 ± 9.56 kcal/mol) but exhibits significant fluctuations. Strong VdW forces mainly drive the binding.

Overall, these data demonstrate that the BCL2-WT/Venetoclax complex has a stable binding interface that permits significant ligand flexibility, allowing Venetoclax to adopt a variety of configurations while remaining securely bound within the hydrophobic groove.

2.2. BCL2-WT Bound to Sonrotoclax

The simulation conditions are well controlled, allowing us to proceed with the rest of the analysis (

Figure 6).

The pocket RMSD analysis shows that the pocket remains extremely stable throughout the 600 ns (mean = 0.20 ± 0.05 nm). Across three independent simulations, the ligand RMSD averaged 1.53 ± 0.93 nm, with values ranging from 0.00 to 8.62 nm. The mean RMSD reveals three phases: an initial compact state; a transition period around ~90–140 ns with the most significant growth and variability, driven by Run 3 reaching approximately 8 nm and a simultaneous upward trend in Run 2, while Run 1 remains comparatively moderate; and a later plateau near ~1.8–2.0 nm that shows slight relaxation after around 170 ns. Because visual inspection confirms that the ligand remains bound throughout all spikes, the average curve probably reflects pose remodeling rather than unbinding (

Figure 7).

The mean RMSF of the protein is approximately 0.18 ± 0.03 nm, ranging from 0.06 to 1.45 nm. The N-terminus, C-terminus, and loop regions exhibit higher RMSF values, indicating increased flexibility. Meanwhile, the protein contains several stable regions, likely corresponding to its core secondary structures such as alpha-helices or beta-sheets. Notably, the pocket residues (143, 144, 145, 146, 188, 192, 193, 196, 197, 198, 200, 201, 202, 206, 208, 209, 210, 211, 212, 213, 216) are very stable and rigid. The RMSF values are consistently low (mean ~0.11 nm, max ~0.16 nm), suggesting these residues are well-structured and show little fluctuation, which is typical for a deep binding cleft that accommodates a ligand.

Sonrotoclax’s mean RMSF is approximately 0.28 ± 0.07 nm, with a range from about 0.07 to 0.58 nm. The atoms with low RMSF values (minimum ~0.07 nm) are part of the ligand's core structure, which remains rigidly held within the BCL2 binding pocket. Additionally, analysis of the ligand_rmsf.xvg file, the .gro file of the complex, and the ligand_sasa.xvg file shows that the regions of the ligand with high flexibility are primarily located at the edges and solvent-exposed substituents rather than the buried core (

Figure 8).

Across three independent simulations, the ligand's SASA averaged 11.60 ± 0.69 nm², with values ranging from 9.39 to 14.00 nm². The ligand's SASA remains relatively small but dynamic, fluctuating instead of settling at a single value. This indicates that parts of the ligand are mobile and periodically become more or less exposed to the solvent.

The SASA analysis of the protein showed an average of 129.75 ± 3.13 nm², with values ranging from 116.65 to 145.38 nm². The complex SASA mean was also calculated as 134.16 ± 3.68 nm², with a minimum of 120.03 nm² and a maximum of 150.50 nm².

After pooling the three trajectories, the mean BSA of this system is ~7.2 nm², with noticeable variability ranging from 0.00 to 12.67 nm

² and a SD of 2.66 nm

² (

Figure 9).

State-resolved analysis of BCL2-WT-Sonrotoclax revealed dynamic binding behavior, with a notable difference between replicates. However, all trajectories maintained nearly continuous protein engagement (≤15.1% unbound) while sampling different binding landscapes. One replicate showed balanced BH3 and weak binding (50.9%/49.1%), another showed predominantly weak binding (67.5%), and a third showed both weak binding and occasional dissociation events. BH3-bound states were generally short-lived (mean dwell times 1.5-2.0 ns), with rapid transitions between binding modes indicating a highly dynamic equilibrium (

Tables S25-S27 of the Supplementary file).

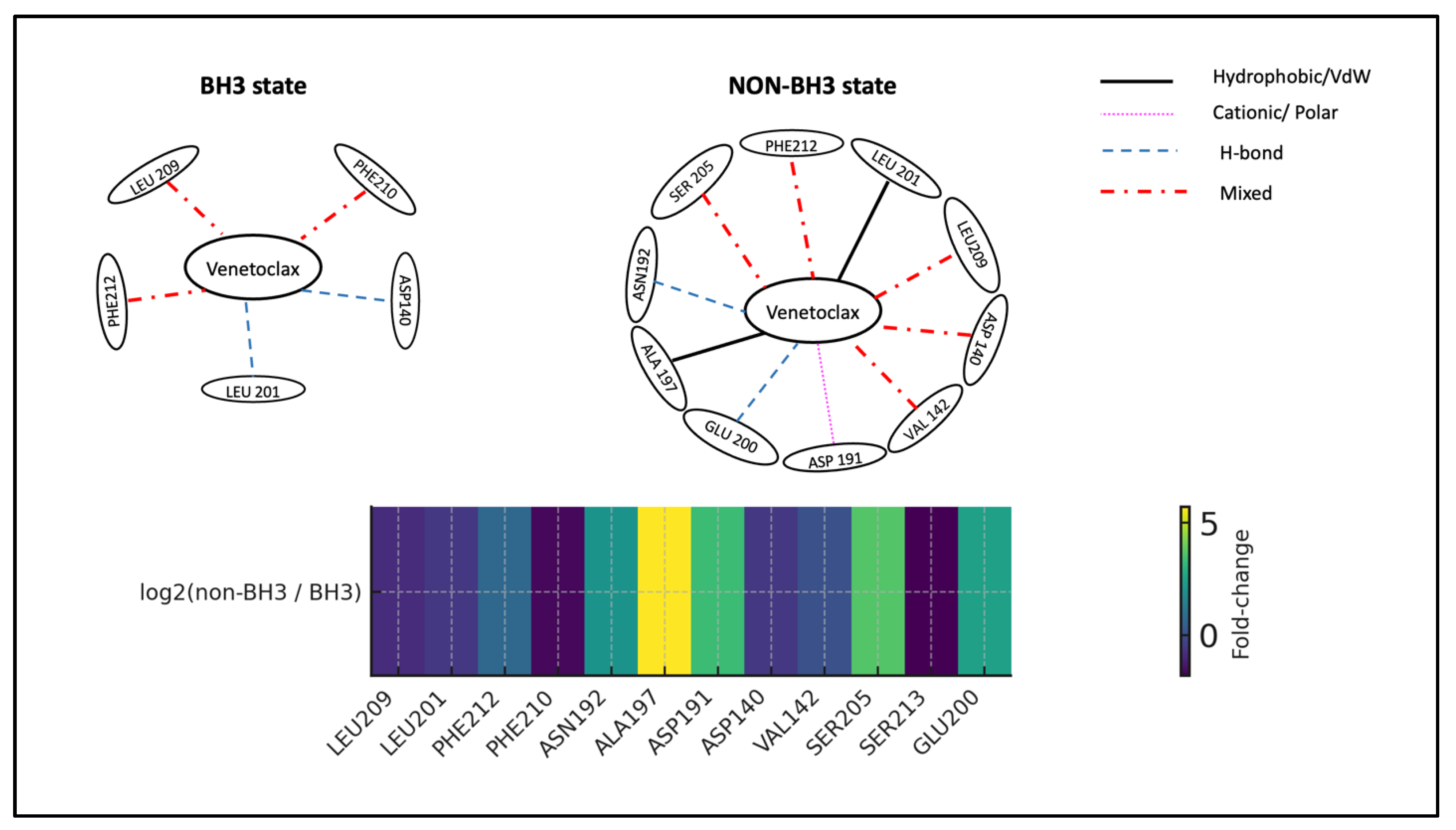

State-resolved interaction analysis indicates that Sonrotoclax may employ different molecular recognition strategies depending on its binding state. During canonical BH3 engagement, the ligand primarily interacts with LEU209, with support from ASN192 and ALA197. In non-BH3 states, while LEU209 mostly plays a central role, its role is reduced compared to the BH3-bound phases. Moreover, peripheral residues, such as PRO204, occasionally serve as key stabilizers instead of LEU209. This flexible binding interface, characterized by state-dependent residue participation, suggests Sonrotoclax can sustain protein engagement through adaptable interaction networks rather than rigid, lock-and-key mechanisms (

Figure 10) (

Tables S28-S30 of the Supplementary file).

The average total binding energy is -18.29 kcal/mol, indicating favorable binding between Sonrotoclax and BCL2-WT. This high SD (10.26) suggests significant fluctuations and instability in the binding energy over time, despite the overall favorable average. Additionally, the large SD of the VdW (15.04), Electrostatic (11.99), and Polar Solvation (16.79) terms further confirms that the individual interactions contributing to binding are highly variable. The VdW interactions are the strongest favorable contributor with -28.01 kcal/mol; subsequently, the Electrostatic interactions with -12.38 kcal/mol. The most opposing interaction is polar solvation, with a score of 25.92 kcal/mol, still not strong enough to cause desolvation. In conclusion, while the average binding is favorable, the binding interaction is highly dynamic and unstable, as evidenced by the large SD in the total binding energy (

Table 2).

Overall Picture

By integrating analytical data, a clear picture of Sonrotoclax's binding behavior with BCL2-WT is revealed. The ligand interacts with BCL2-WT through a dynamic balance between canonical BH3 binding and alternative modes, rather than holding a single static pose. This dynamic is also evident in significant fluctuations in ligand RMSD and in stable BSA values. The binding mechanism exhibits considerable variability across replicates, with individual trajectories capturing different parts of the energy landscape. Despite this, Sonrotoclax maintains persistent contact with the protein through adaptive interaction networks. In BH3-bound states, the ligand primarily anchors via LEU209, with support from contacts from ASN192 and ALA197. During transitions to non-BH3 states, the interaction network undergoes significant molecular rewiring. This binding flexibility is further reflected in the MM/GBSA results, where the strongly favorable average binding energy (-18.29 kcal/mol) coexists with high SDs across all energy components, indicating multiple competing binding modes. The pocket remains consistently rigid (RMSF ~0.11 nm) throughout these transitions, suggesting that the observed dynamics are mainly due to ligand adaptability rather than major conformational changes in the protein. In summary, Sonrotoclax binding to BCL2-WT exhibits conformational heterogeneity and state-dependent interaction networks, with the ligand maintaining persistent engagement through adaptive molecular recognition. This dynamic binding behavior could contribute to its clinical effectiveness by enabling robust target inhibition across different conformational states.

2.3. BCL2-G101V Bound to Venetoclax

According to the energy and equilibration analysis (

Figure 11), the system's initial position is appropriate, allowing the rest of the analysis to proceed.

Thermodynamic and box-dimension traces demonstrating that the G101V–Venetoclax simulations are well equilibrated and suitable for downstream analyses.

The mean ligand RMSD clearly drifts from an initially tight pose to a much looser, displaced state, with an average of 1.55 ± 0.61 nm, ranging from 0.00 to 9.60 nm. Quantitatively, the mean curve shows a baseline of approximately 0.62 nm in the first 10% of frames, increasing to about 2.86 nm in the last 10% of frames, indicating more than a 4.5-fold rise. The overall min/max range is 0.00-4.24 nm, with a slight, positive linear trend (slope ≈ 1.45×10⁻⁵ nm/ns) that highlights gradual divergence. Notably, the largest excursions occur later in the trajectory, with peak values around 4.14–4.24 nm between 162.6–189.8 ns, signifying sustained ligand displacement rather than transient movement. This pattern—low RMSD early, progressive increase, and late high-RMSD plateaus—suggests a transition from a bound, well-aligned pose to an unbound or partially disengaged state.

In contrast, the binding pocket remains highly rigid and stable throughout the simulation, with a mean of 0.21 ± 0.05 nm and values ranging from 0.00 to 0.49 nm (

Figure 12).

RMSD of BH3 pocket residues and Venetoclax showing a rigid groove but progressive ligand displacement and late high-RMSD plateaus consistent with partial unbinding.

The protein RMSF ranges from 0.07 to 1.14 nm, averaging 0.24 ± 0.21 nm. Fluctuations vary by structure, with terminal regions and loops more flexible, while the core includes stable alpha-helices and beta-sheets. Additionally, the pocket residues of the BCL2-G101V (136, 137, 138, 139, 140, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 188, 192, 201, 202, 206, 209, 210, 212, 213, 216, 217, 220, 223) are considerably more rigid, with a mean of 0.13 ± 0.21 nm (Min = 0.08 nm, Max = 0.17 nm). This indicates a well-defined and stable binding site. The ligand RMSF shows a moderate fluctuation range from 0.08 to 0.36 nm, with a mean of 0.21 ± 0.07 nm. A clear distinction exists between a rigid core (Min RMSF = 0.08 nm) and more flexible peripheral groups (

Figure 13).

The mean SASA/BSA profiles from three runs show a progressive loss of interfacial burial. Quantitatively, the ligand SASA remains modest and relatively tight overall (7.40 ± 0.38 nm²), but it decreases from the first 10% (8.04 nm²) to the last 10% of the trajectory (7.07 nm²), representing a 12.1% reduction. This suggests that as the complex loosens, the ligand surface initially partially occluded by the protein becomes less opposed by the same interfacial area of the complex (Figure 15). In contrast, protein SASA increases from 131.05 to 138.06 nm², a 5.35% rise, and the complex SASA increases even more, from 131.37 to 140.52 nm², reflecting a 6.97% increase. These changes are consistent with pocket opening, reorientation, and increased solvent exposure. Most importantly, the mean BSA has a broad distribution (5.72 ± 1.41 nm² overall) but decreases by about 40% over time, from 7.72 to 4.61 nm² (−40.4% from early to late windows). This continuous decline in buried area, coupled with the rising complex and protein SASA, indicates a loosening and partial separation of the interface rather than just side-chain breathing. (

Figure 14).

Protein, ligand, and complex SASA together with BSA over time, revealing increasing solvent exposure and ~40% loss of buried surface area consistent with interface loosening.

State-resolved analysis of BCL2-G101V-Venetoclax revealed notable replicate-dependent responses to the mutation. The system showed three distinct behavioral patterns: one replicate maintained substantial BH3 binding (50.7%) but experienced significant dissociation periods (23.3% unbound); another showed a continuous engagement (53.4% BH3, 46.4% weak, 0% unbound); while a third mainly exhibited weak binding (59.9%) with reduced BH3 occupancy (27.4%).

This variability was further evident in binding kinetics, where BH3 dwell times ranged widely from short-lived engagements of 1.9 ns to more stable binding episodes of 6.75 ns. The significant differences across replicates suggest that the G101V mutation creates an unstable energy landscape in which Venetoclax samples multiple binding states, ranging from productive BH3 engagement to extended weak binding or partial dissociation, potentially explaining the heterogeneous clinical responses observed with this resistance mutation (

Tables S39-S41 of the Supplementary file).

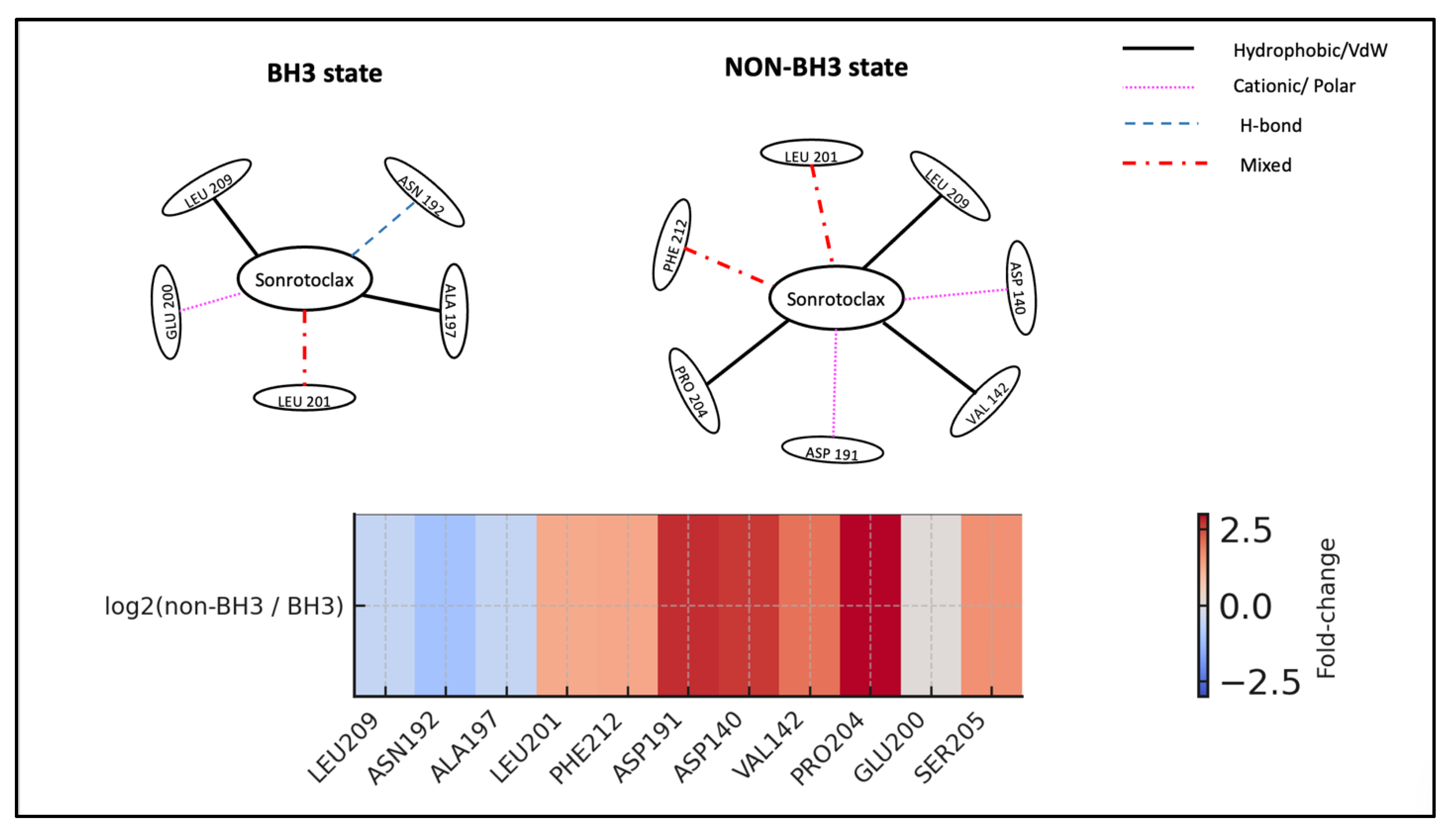

Mirroring the state-resolved analysis, the BCL2-G101V-Venetoclax interactions also uncovered three distinct molecular strategies for overcoming the resistance mutation. In one trial, the ligand remained in both BH3 and non-BH3-bound states through adaptive interactions with the primary anchors LEU209 and LEU201. A second trial showed complete binding-site migration in the non-BH3 states, with the ligand moving to a solvent-exposed surface region dominated by CYS229 and GLY233, indicating a clear resistance mechanism. Most surprisingly, a third trial demonstrated a paradoxical reinforcement of LEU209 interactions, with increased hydrogen bonding and cationic character, suggesting occasional mutational override ability. This notable heterogeneity in molecular response strategies provides a structural basis for the variable clinical effectiveness of venetoclax against G101V mutants. It also highlights the mutation's role in destabilizing productive binding, without uniformly preventing it (

Figure 15) (

Tables S42-S44 of the Supplementary file).

The average total binding energy for BCL2-G101V with venetoclax is -16.54 kcal/mol, indicating favorable binding despite the resistance mutation. The SD of 6.25 kcal/mol suggests fluctuations in binding energy over time, though with less variability than observed with the wild-type protein. The SD of the VdW (7.86), Electrostatic (8.99), and Polar Solvation (9.89) terms indicate moderately dynamic interactions. VdW interactions are the strongest favorable contributor at -26.09 kcal/mol, followed by electrostatic interactions at -10.41 kcal/mol. The primary opposing force remains polar solvation energy at 23.49 kcal/mol, which is outweighed by the favorable binding contributions. In summary, while the G101V mutation reduces binding affinity compared to WT, Venetoclax maintains favorable binding through persistent VdW and electrostatic interactions, with reduced energetic variability suggesting a more constrained binding landscape in the mutant system (

Table 3).

Overall Picture

The G101V mutation causes significant instability in the BCL2-Venetoclax complex, leading to a heterogeneous and weakened binding environment. Although the binding pocket itself remains structurally stable, an increasing ligand RMSD and approximately a 40% reduction in BSA over time support continuous and progressive ligand displacement. This shift from an initially bound position to a more relaxed, disengaged state is the key characteristic of the mutant complex.

The system does not adopt a single resistant state but instead explores multiple, different binding fates. State-resolved analyses show significant variation between replicates, where Venetoclax may temporarily engage with the canonical BH3 groove adaptively; or completely shift to a solvent-exposed peripheral site; or, in some cases, strengthen interactions with key anchors such as LEU209.

Despite this instability, the MM/GBSA binding free energy remains favorable (-16.54 kcal/mol), primarily due to ongoing VdW interactions. However, the lower energy variation compared to the WT suggests a more limited but overall weaker binding landscape. Overall, these findings illustrate that the G101V mutant is not simply a switch for resistance but acts as a molecular fault line that destabilizes the native binding mode, permitting various ligand pathways that collectively diminish the drug's effectiveness.

2.4. BCL2-G101V Bound to Sonrotoclax

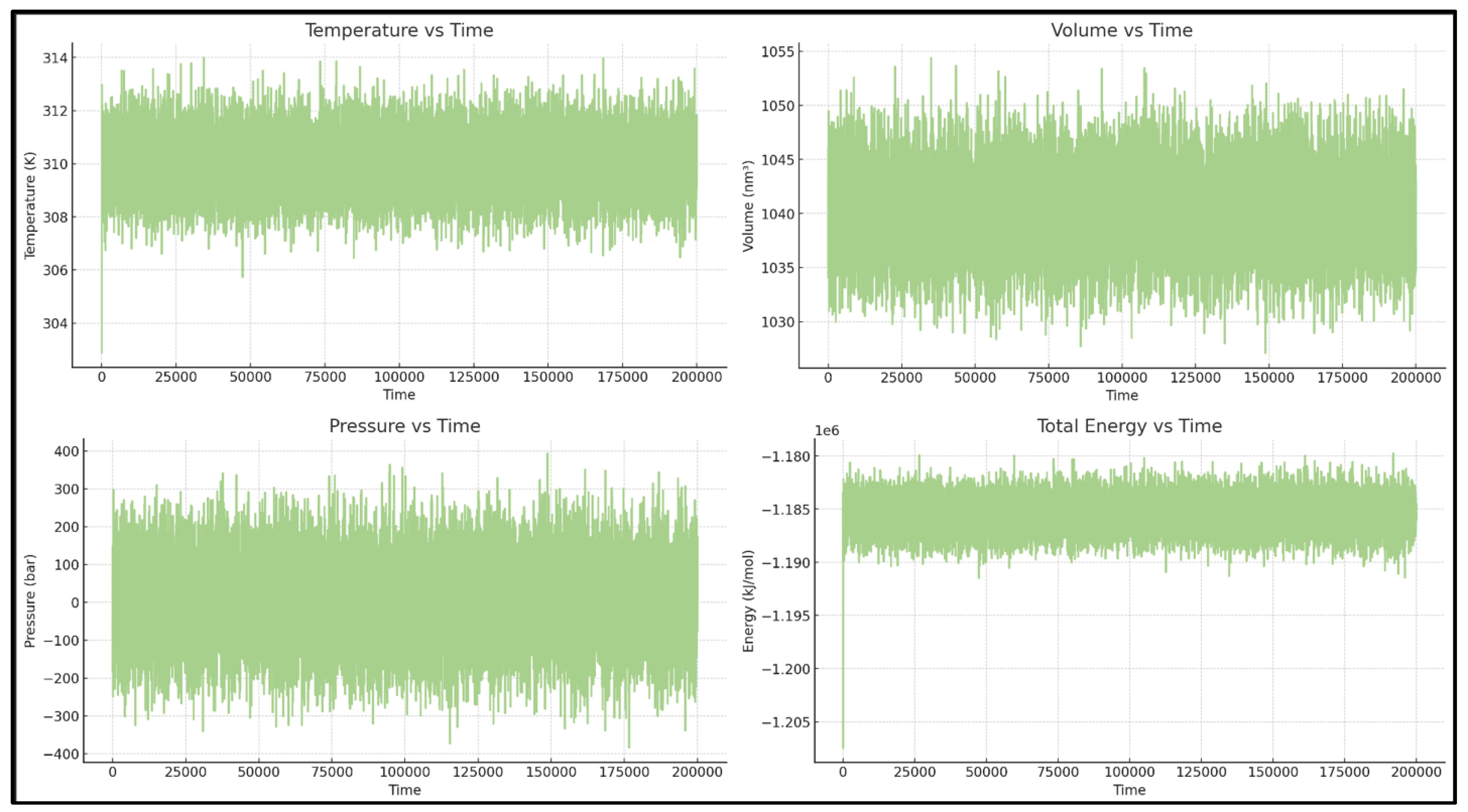

According to the energy and equilibration plots, the system is appropriate for running the next analysis (

Figure 16).

Time series of key thermodynamic variables confirming stable conditions for the G101V–Sonrotoclax simulations.

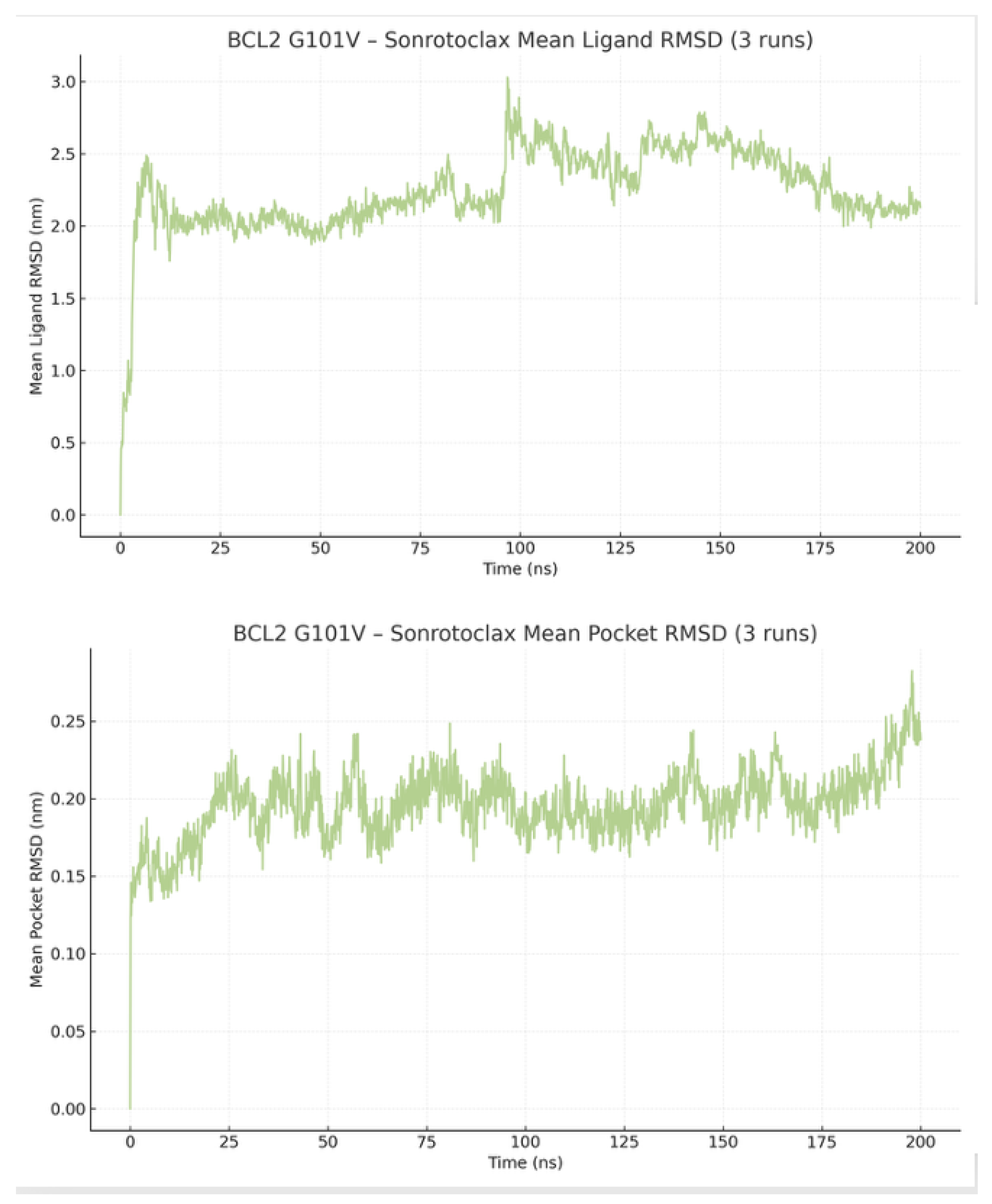

The RMSD of the pocket residues remains highly stable throughout the simulation, with a mean of 0.196 nm and a SD of 0.022 nm. The RMSD plot for Sonrotoclax is also relatively stable, although a detectable jump is observed, with a mean of 2.24 ± 0.11 nm and a range of 0.00 to 4.44 nm (

Figure 17).

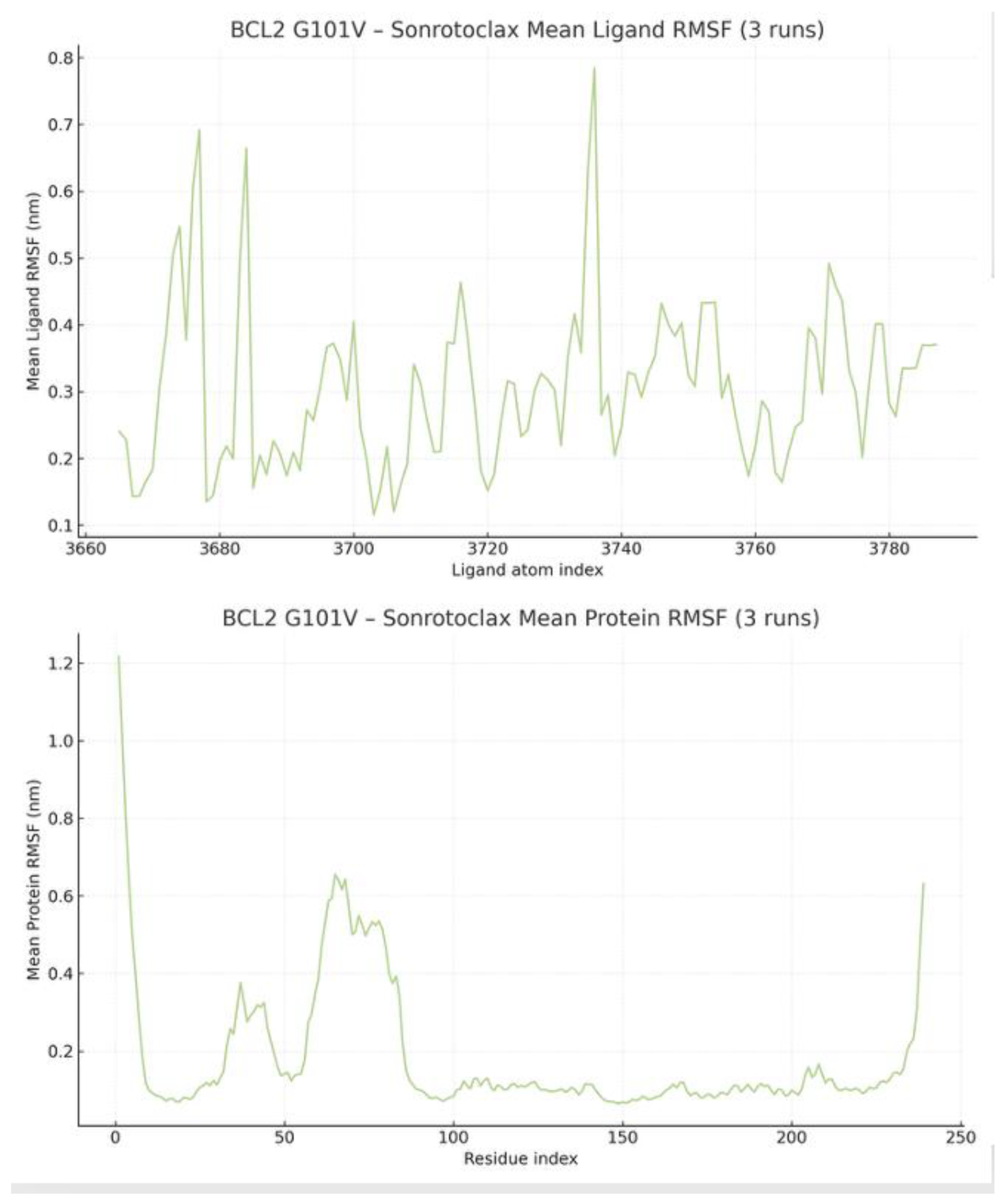

The protein RMSF, as expected, is high in the N-terminus and C-terminus regions. The more stable regions of the protein, such as alpha-helices, exhibit low RMSF values, with fluctuations typically below 0.10 nm. The pocket residues, including 143, 144, 145, 146, 188, 192, 193, 196, 197, 198, 200, 201, 202, 206, 208, 209, 210, 211, 212, 213, 216, are uniformly low. They range from 0.07 nm to 0.17 nm, indicating that the binding pocket is a highly stable and rigid part of the protein structure.

The ligand is not uniformly rigid. It has parts that are very stable and highly mobile, ranging from 0.12 to 0.78 nm. The mean RMSF of the Sonrotoclax is 0.30 nm with a SD of 0.12 (

Figure 18).

Per-residue RMSF of mutant BCL-2 and atom-wise RMSF of Sonrotoclax demonstrating a uniformly rigid pocket and a ligand with a stable core and flexible solvent-exposed groups.

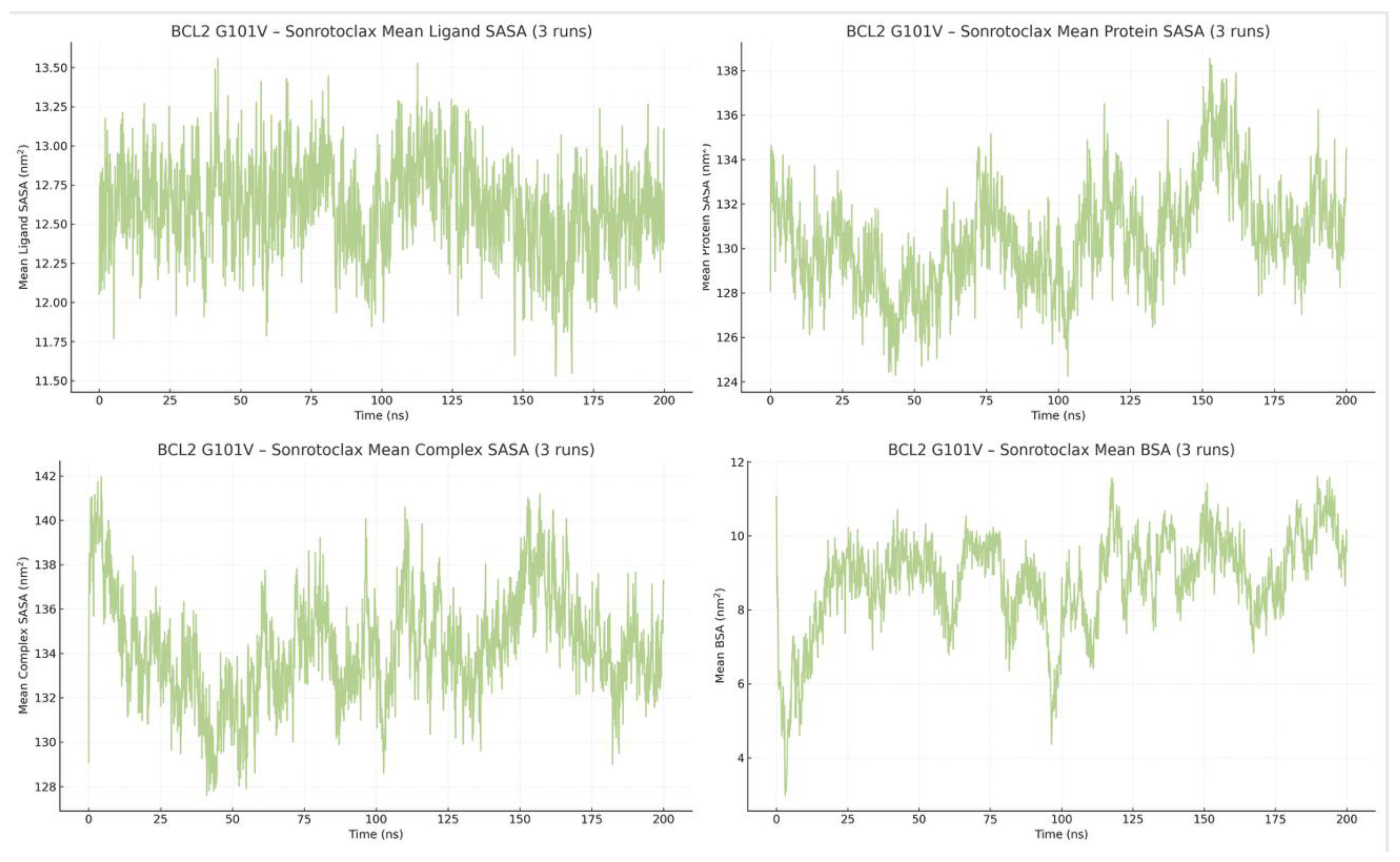

Across the three independent simulations of BCL2-G101V bound to Sonrotoclax, solvent exposure and interface burial remained highly consistent. The mean protein SASA trace was narrowly distributed around 130.46 ± 1.36 nm² (range 117.77 to 148.17 nm²), while the mean complex SASA was 134.28 ± 1.55 nm² (range 121.23 to 153.78 nm²). The ligand SASA itself stayed relatively low and stable across runs (mean ≈ 12.61 ± 0.06 nm², range ≈ 10.73 to 14.09 nm²), indicating that Sonrotoclax is predominantly shielded from solvent. Consistent with this, the mean BSA across the three trajectories was 8.79 ± 1.29 nm² (range 2.99–11.59 nm²), supporting a compact BCL2-G101V–Sonrotoclax complex that maintains a persistently buried, yet dynamically breathing, binding interface throughout the simulations (

Figure 19).

Protein, ligand, and complex SASA and corresponding BSA across three trajectories showing tightly clustered traces and a consistently high buried interface, indicative of a compact complex.

State-resolved analysis of BCL2-G101V-Sonrotoclax reveals a fundamentally altered binding mechanism that explains its ability to overcome the G101V resistance mutation. Contrary to restoring stable, canonical BH3 engagement, Sonrotoclax adopts a strategy of persistent “frustrated binding”, maintaining near-continuous protein association (≤0.4% unbound) through overwhelmingly weak interactions, held for 75-99% of simulation time [

49,

50,

51]. This near-perpetual occupancy of the binding region, despite minimal deep-pocket engagement, suggests a model in which Sonrotoclax inhibits the G101V mutant not through high-affinity BH3 binding but by creating a kinetic barrier, effectively “blocking” the pocket via prolonged, though weak, association. This mechanism of action, transitioning from a traditional occupancy-driven inhibition to a potentially kinetics-driven “blockade”, offers a structural explanation for its clinical effectiveness against a mutation that drastically disrupts Venetoclax's binding mode (

Tables S53-S55 of the Supplementary file).

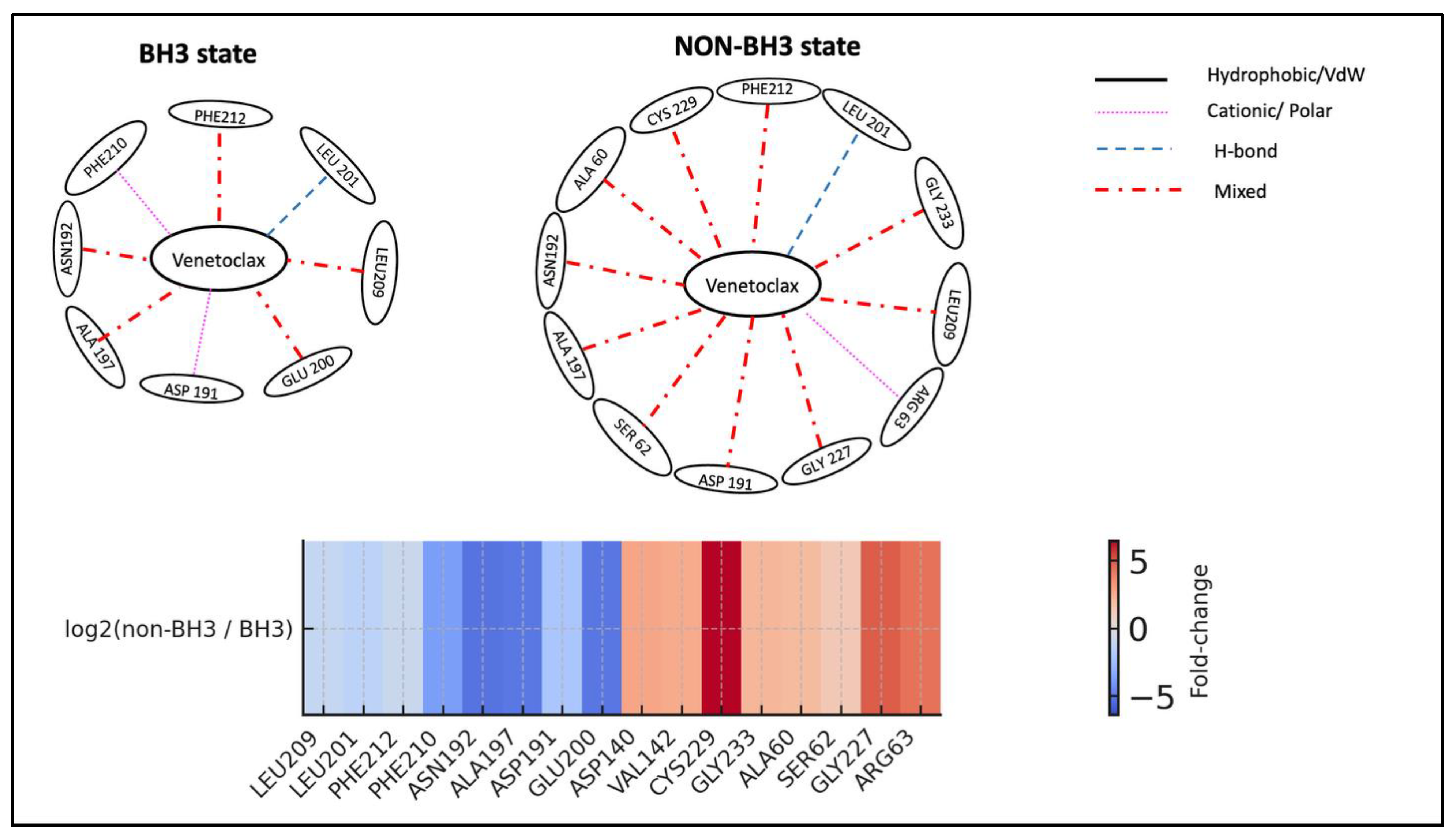

Interaction fingerprinting demonstrates that the effectiveness of Sonrotoclax against the G101V mutant results from adaptive plasticity rather than from sustained occupation of the BH3. However, the mutation prevents deep-pocket engagement and reduces BH3-bound states to almost zero. Sonrotoclax remains a potent inhibitor by shifting to a primary strategy of sustained, weak binding. A flexible interaction network facilitates this. The conserved anchor LEU209 is complemented by alternative residues, such as SER205, in shallow binding modes. Notably, while crystallographic studies highlight a critical Π-stacking interaction with TRP188, our solution-phase simulations reveal that this contact becomes transient in the G101V mutant. Instead, the ligand adapts by recruiting alternative polar partners like SER205 (23.6% occupancy) and PRO208 to maintain high-affinity engagement despite the loss of the canonical tryptophan anchor. This ability to form multiple, non-canonical interaction sets, ensuring continuous protein occupancy, underpins its capacity to overcome venetoclax resistance (

Figure 20) (

Tables S56-S58 of the Supplementary file).

The average total binding energy is -20.99 ± 8.06 kcal/mol. This negative value indicates that binding between Sonrotoclax and the BCL-2 G101V mutant is generally favorable. VdW interactions are the main positive contributor to binding. Additionally, electrostatic interactions also contribute beneficially. Lastly, nonpolar solvation energy provides a minor beneficial contribution, while polar solvation energy opposes binding, as expected.

The SD value of the total binding energy is quite high, signaling significant fluctuation and instability in the binding interaction over time. The high SD in electrostatic and polar solvation further reinforces this observation (

Table 4).

Overall Picture

Integrating structural, energetic, and state-resolved analyses reveals a coherent, yet somewhat paradoxical, mechanism for Sonrotoclax's action against the BCL2-G101V mutant. Despite the near-total ablation of stable BH3 engagement (≤4% occupancy), Sonrotoclax maintains a potent and even marginally stronger binding affinity (-20.99 kcal/mol) compared to the WT system. The ligand avoids a single, deep-binding pose. However, it shows a persistent, "frustrated" binding state, maintaining near-continuous protein association (99.7% weak binding) through constant conformational sampling within the binding groove. This is further supported by a consistently buried interface (BSA ~8.8 nm²). Energetically, this dynamic blockade is driven by a robust and enhanced VdW contribution (-33.53 kcal/mol), supplemented by favorable electrostatic interactions. The high SD across all energy components is a direct reflection of this dynamic binding process, in which the ligand samples multiple shallow interaction networks. The conserved anchor LEU209 is key, but its role is fluid, supported by adaptive interactions with residues like SER205.

In conclusion, Sonrotoclax overcomes the G101V mutation not by restoring the deep, static binding characteristic of Venetoclax, but rather through a strategy of dynamic occupancy and kinetic trapping. Maintaining a consistent, shallow presence in the binding groove likely creates a functional blockade that prevents BCL2 from engaging its pro-apoptotic partners, providing a compelling structural and energetic rationale for its clinical efficacy against this resistant mutant.

3. Discussion

The main question we sought to answer in this work is the primary reason for Sonrotoclax's greater effectiveness against BCL2-G101V compared with Venetoclax. Based on our results, we hypothesize that while Venetoclax relies on a precise, deep-pocket "lock-and-key" fit to inhibit BCL2, Sonrotoclax circumvents resistance through a "Dynamic Blockade" mechanism, maintaining high-affinity inhibition through surface-associated, adaptive interactions rather than rigid deep-groove insertion.

The first notable matter is the absence of the 101st residue as a pocket residue in both crystal structures (8HOH and 6O0L) and our models, thereby shrouding the mechanism of its mutation in obscurity (

Tables S1 and S2 in the Supplementary file). Birkinshaw

et al. [

52] have answered this controversy in their crystal structure study. According to them, this mutation acts in an indirect, second-shell manner rather than by creating a new direct contact with the drug. In the 6O0L structure, G101V is located on the α2 helix within the BH3 motif, near A100 and D103 residues, disturbing the neighboring E152 side chain, thereby intruding into the P2 pocket and partially occluding the binding site for Venetoclax’s chlorophenyl group. The mentioned “knock-on effect” of V101 on E152 provides a structural explanation for the ~180-fold loss of Venetoclax affinity observed experimentally, while preserving binding to BH3 peptides that engage the canonical groove. Moreover, in these crystal structures, not residue 101, but other neighboring residues such as A100, D103, and E152 lie within hydrogen-bonding or van der Waals contact range of Venetoclax [

52].

To explore the dynamic effects of the G101V mutation beyond the static view offered by crystallography, we used a solution-phase molecular dynamics approach. In our BCL2 G101V models, created by starting from an AlphaFold template, relaxing the apo-like BH3 groove for 50 ns of MD, and then docking Venetoclax or Sonrotoclax, the ligands settle into positions that are deeper and slightly shifted within the groove compared to the crystallographic Venetoclax/Sonrotoclax complexes. In this configuration, residue 101 is still located adjacent to A100, D103, F104, V148, E152, and other helix residues that define the P2/P4 lip, indicating a second-shell location on α2, but both residue 101 and E152 lie farther from the docked ligands than in 6O0L/8HOH. While we observe that residue 101 retains a second-shell location on the α2 helix, our simulations reveal an alternative, metastable binding mode distinct from the specific V101–E152–ligand triad reported in crystal structures. This approach was chosen to identify alternative binding modes and second-shell allosteric changes that crystal lattice packing forces might hide. Therefore, our simulations probe the functional energy landscape of the mutant receptor rather than strictly replicating the exact crystallographic pose. Within this framework, our simulations are best judged by whether they reproduce the qualitative experimental pattern of G101V-mediated resistance, rather than the exact crystal pose, which is consistent with our results [

28].

Our analysis first established that the dynamics of both Sonrotoclax and Venetoclax within the BH3 groove are intrinsic to the WT background. Both of them revealed significant fluctuations in their RMSDs, indicating that conformational sampling and pose mobility are not, in themselves, indicative of poor binding. (Figure 3 and Figure 8) Crucially, despite these fluctuations, both ligands maintained high binding free energies (-17.32 kcal/mol for Venetoclax and -18.29 kcal/mol for Sonrotoclax) and a BSA > 6.0 nm² in most frames (Figure 5 and Figure 10). This dynamic behavior is consistent with a model of conformational selection or induced fit, which is common for high-affinity ligands in flexible binding sites [

11,

53,

54]. At a global level, our simulations show that, in BCL2-WT, both ligands mostly stay associated with the BH3 groove while switching between BH3-like and non-BH3 poses. Across three 200 ns trajectories, WT Venetoclax sampled ~15 ns of UNBOUND frames in total, whereas Sonrotoclax showed unbinding only in a single trajectory (~30 ns), remaining fully bound in the other two.

By introducing the G101V mutation, stark changes in Venetoclax behavior are detectable. While the pocket of the protein stays relatively stable, Venetoclax undergoes a progressive and sustained displacement, supported by its RMSD values (~ 0.00 nm at first and a ~4.14–4.24 nm plateau RMSD in approximately the last 50 ns). (Figure 13) This deviation reflects functional decoupling rather than simple conformational sampling, as evidenced by a ~40% reduction in BSA over time (7.72 nm

² to 4.61 nm²). (Figure 15) Our state classification analysis and interaction fingerprints reinforce this interpretation. Venetoclax does not simply oscillate between equivalent poses within the pocket; it exhibits long-lived unbound phases based on COM distance, minimum distance, contacts, and hydrogen-bond criteria for dissociation. (

Tables S38-S43 of the Supplementary file and Figure 16) Perceptibly, Venetoclax loses almost all BH3 interaction network when it gets unbound, including the LEU209/LEU201/PHE210 hydrophobic core and auxiliary contacts to residues such as ASN192 and SER205, which are characteristic of productive binding in the BH3 pocket.

Compared with Venetoclax, Sonrotoclax exhibits a fundamentally different response to the same mutation. Despite fluctuations in ligand RMSD within the BCL2-G101V, the pocket RMSD remains low, the complex BSA remains high, and the ligand SASA does not show a sustained increase that would suggest genuine disengagement from the groove (Figure 18 and Figure 20).

Furthermore, the state analysis demonstrates a consistent presence of Sonrotoclax in the bound state, predominantly in the weak state. Notably, the unbound time is negligible across all three replicates (less than 2 ns out of 600 ns) (

Tables S51-S53 of the Supplementary file). Even though the state analysis reported Sonrotoclax as dominantly weakly bound, its binding free energy is higher than that of Venetoclax (-20.99 Kcal/mol vs -16.54 kcal/mol). (

Table 4 ) This finding is consistent with its demonstrated preclinical efficacy against this mutant [

28].

We propose that the geometric mobility concurrent with energetic stability is a hallmark of entropy-enthalpy compensation, a phenomenon often observed in robust drug design [

55]. Venetoclax is not able to achieve a similarly favorable balance upon reorienting in the mutated pocket. Meanwhile, the Sonrotoclax exploits the plasticity of the pocket [

11]. The highly non-specific VdW contribution of -33.53 kcal/mol in anchoring Sonrotoclax counterbalances the loss of specific polar contacts. The ProLIF analysis further clarifies this complexity. Instead of relying on a single, rigid BH3-bound pose, Sonrotoclax maintains a continuous hydrophobic anchor on LEU209 and a flexible, rewiring network of auxiliary contacts involving residues such as ASN192, ALA197, SER205, and neighboring leucine at the C-terminal rim. Various subsets of these interactions are utilized when the ligand reorients within the groove, but at least part of the network remains engaged at almost all times (

Tables S54-S56 of the Supplementary file). The “anchor switching” mechanism of Sonrotoclax mimics that of second-generation HIV protease inhibitors, such as Darunavir. These inhibitors overcome resistance by fitting into the "substrate envelope" and adapting to backbone flexibility [

56,

57].

Due to the aforementioned data, the Sonrotoclax does not play its role by being a static plug, but rather as a dynamic substitute that saturates the BH3 groove, thereby prolonging residence time (

Tables S51-S53 of the Supplementary file), thus blocking pro-apoptotic binding partners through kinetic occupancy rather than static affinity. As a result, it prevents the engagement of pro-apoptotic BH3-only proteins like BIM or BAD, thereby inducing apoptosis even in the presence of the resistance mutation [

58,

59,

60].

This mechanistic insight addresses a vital clinical paradox. If the G101V mutation acted as a strict "hard off" switch (steric exclusion), Venetoclax would show zero affinity. However, G101V causes about a 180-fold change in affinity rather than a complete loss, indicating a resistance mechanism in which high concentrations can still bind, though limited in practice by toxicity. Our simulations reveal the structural basis for this leakiness: the mutation doesn’t form a rigid barrier but instead creates a chaotic energy landscape. In this setting, Venetoclax’s effectiveness becomes probabilistic and delicate, explaining the subclonal persistence seen in patients. Conversely, Sonrotoclax's "Dynamic Blockade" provides strong, state-independent inhibition that remains effective even in this fluctuating conformational state, potentially controlling resistant subclones before they cause full relapse.

Collectively, our work offers a mechanistic model that goes beyond a simple affinity-based explanation. While the Venetoclax resistance results from the disruption of a specific, high-precision binding mode, Sonrotoclax's effectiveness stems from its inherent molecular flexibility. As a result, it governs a dynamic, sustained blockade of the BH3 groove that remains resilient in spite of the allosteric perturbations induced by the G101V mutation. The Dynamic Blockade mechanism offers a blueprint for rationally designing “frustrated” inhibitors that can tolerate allosteric groove mutations by initially focusing on a sustained hydrophobic anchor residue, secondly, a flexible linker that permits minor rewiring, and finally a polar cap that prevents complete dissociation.

5. Conclusions

This study establishes the molecular foundations for Sonrotoclax's superior efficacy compared to Venetoclax, accounting for the mutated BCL2-G101V form. The findings outline a shift away from the ‘lock-and-key’ paradigm, exemplified by the rigid-body correlation. However, it has already been found in numerous drug molecules, particularly anticancer drugs, that shift towards dynamic blockades. The G101V mutation indirectly interrupts venetoclax's precise interactions through a "knock-on effect" on neighboring residues, illustrated by means of detailed MDS and energetic analyses. As a notable example, E152 would correlate with increased ligand mobility, decreased BSA, and frequent dissociation. Nonetheless, Sonrotoclax influences conformational flexibility and entropy-enthalpy compensation to sustain high-affinity binding. As well as groove perturbations adoption via switching the anchor, reminiscent of darunavir's substrate envelope strategy in HIV protease inhibitors. Subsequently, this would guarantee prolonged residence time and effective blockade of pro-apoptotic partners. The mentioned adaptive paradigm could be more than just a solution for the clinical paradox of partial resistance. Besides, it would underscore the importance of dynamic simulations in capturing metastable states beyond static crystallography. In consequence, supporting conformational selection and prompted fit models. Considering visualized drug attachment and its structural impact on function, our approach enables more accurate therapeutic optimization or repurposing. Collectively, suggesting a cost-effective alternative to old methods of drug development pipelines, which require extensive time and resources.

Nevertheless, some limitations of this method warrant mention. The computational origin of our method has stood on force field calculations and solvation models. To this end, it might not fully represent the expected physiological environment, such as cellular crowding or pH variations. While our 200 ns simulation clarifies local dynamics, it would be challenging to capture rare events or long-term conformational changes within a brief time frame. Although for processes such as ligand debonding, a nanosecond scale is not sufficient, a microsecond scale is necessary. Moreover, whereas our models reproduce qualitative resistance patterns, discrepancies with crystal structures (for example, in specific pose reproduction) suggest possible biases arising from primary docking or ensemble selection. Validation of these in silico predictions requires wet-lab analysis and clinical validation via biochemical or cellular viability studies.

For future directions, delving deeper into analyses of other clinically relevant BCL-2 mutations that disrupt the BH3 groove and confer venetoclax resistance would broaden the applicability of the "Dynamic Blockade" model. In addition to single-mutation models, upcoming studies should investigate the underlying interplay between G101V and E152. Our findings and the literature suggest that the true disruption does not arise from G101V alone, but rather from its ripple into E152 and the downstream reconfiguration of the P2/P4 pocket. This means that simultaneous mutations at G101V and E152 would provide a clear insight into the whole allosteric cascade. Furthermore, longer simulations, improved sampling techniques (for example, metadynamics), or integration with machine learning could refine predictions of allosteric effects. Finally, these visions provide an outline for engineering "frustrated" inhibitors that are resilient to allosteric mutations. The primary focus of dissociation prevention could be on several markers, including sustained hydrophobic anchors, flexible linkers, and polar caps. Having all these in mind, the suggested strategies could be a breakthrough in overcoming resistance to BCL-2-targeted therapies.

Figure 1.

Energy and equilibration of BCL2-WT bound to the Venetoclax system. Time series of temperature, total energy, pressure, and box dimensions confirming stable simulation conditions for the WT-Venetoclax systems.

Figure 1.

Energy and equilibration of BCL2-WT bound to the Venetoclax system. Time series of temperature, total energy, pressure, and box dimensions confirming stable simulation conditions for the WT-Venetoclax systems.

Figure 2.

Pocket RMSD of BCL2-WT and Venetoclax. Time evolution of the pocket RMSD showing a highly stable BH3 groove with only minor fluctuations consistent with normal protein breathing motions. Ligand RMSD traces from three 200-ns simulations illustrating initial relaxation of the docked pose followed by sampling of multiple in-pocket configurations without sustained unbinding.

Figure 2.

Pocket RMSD of BCL2-WT and Venetoclax. Time evolution of the pocket RMSD showing a highly stable BH3 groove with only minor fluctuations consistent with normal protein breathing motions. Ligand RMSD traces from three 200-ns simulations illustrating initial relaxation of the docked pose followed by sampling of multiple in-pocket configurations without sustained unbinding.

Figure 3.

Per-residue RMSF of BCL2-WT and atom-wise RMSF of Venetoclax. RMSF profile of all BCL-2 residues with pocket residues highlighted, together with atom-wise RMSF of Venetoclax, demonstrating a rigid BH3 groove and flexible ligand periphery.

Figure 3.

Per-residue RMSF of BCL2-WT and atom-wise RMSF of Venetoclax. RMSF profile of all BCL-2 residues with pocket residues highlighted, together with atom-wise RMSF of Venetoclax, demonstrating a rigid BH3 groove and flexible ligand periphery.

Figure 4.

SASA and BSA dynamics for the BCL2-WT–Venetoclax complex. Protein, ligand, and complex SASA traces and derived BSA over 600 ns, showing a largely well-buried interface with occasional breathing events but no persistent interface loss.

Figure 4.

SASA and BSA dynamics for the BCL2-WT–Venetoclax complex. Protein, ligand, and complex SASA traces and derived BSA over 600 ns, showing a largely well-buried interface with occasional breathing events but no persistent interface loss.

Figure 5.

State-dependent interaction reconfiguration of Venetoclax at the BCL2-WT BH3 pocket. The top figure shows schematic interaction networks for Venetoclax in BH3 (left) and non-BH3 (right) states. In the BH3 state, binding primarily involves canonical pocket residues LEU209 and LEU201, along with additional contacts from PHE210, PHE212, and ASP140. In the non-BH3 state, LEU209 and LEU201 remain engaged, but the interaction pattern shifts toward alternative partners, including ASN192, ALA197, ASP191, SER205, GLU200, and VAL142, indicating a more distributed and polar contact network. Edge styles and colors encode interaction types as shown in the legend (black solid = hydrophobic/VdW, purple dotted = cationic/polar, blue dashed = H-bond, red dash-dot = mixed). The bottom figure summarizes these changes with a heatmap of contact frequencies for key residues. For each residue, the color encodes the log₂ fold-change in interaction frequency between non-BH3 and BH3 states [log₂(% non-BH3 frames with interaction / % BH3 frames with interaction)], using PROLIF occupancies averaged across three independent simulations. Negative values reflect residues more involved in BH3 states, such as LEU209 and LEU201. Conversely, positive values highlight residues that become more significant in non-BH3 states, including ASN192, ALA197, ASP191, and SER205, illustrating the shift from a LEU209/LEU201-centered canonical BH3 anchoring to a diversified non-BH3 interaction network.

Figure 5.

State-dependent interaction reconfiguration of Venetoclax at the BCL2-WT BH3 pocket. The top figure shows schematic interaction networks for Venetoclax in BH3 (left) and non-BH3 (right) states. In the BH3 state, binding primarily involves canonical pocket residues LEU209 and LEU201, along with additional contacts from PHE210, PHE212, and ASP140. In the non-BH3 state, LEU209 and LEU201 remain engaged, but the interaction pattern shifts toward alternative partners, including ASN192, ALA197, ASP191, SER205, GLU200, and VAL142, indicating a more distributed and polar contact network. Edge styles and colors encode interaction types as shown in the legend (black solid = hydrophobic/VdW, purple dotted = cationic/polar, blue dashed = H-bond, red dash-dot = mixed). The bottom figure summarizes these changes with a heatmap of contact frequencies for key residues. For each residue, the color encodes the log₂ fold-change in interaction frequency between non-BH3 and BH3 states [log₂(% non-BH3 frames with interaction / % BH3 frames with interaction)], using PROLIF occupancies averaged across three independent simulations. Negative values reflect residues more involved in BH3 states, such as LEU209 and LEU201. Conversely, positive values highlight residues that become more significant in non-BH3 states, including ASN192, ALA197, ASP191, and SER205, illustrating the shift from a LEU209/LEU201-centered canonical BH3 anchoring to a diversified non-BH3 interaction network.

Figure 6.

Energy and equilibration of BCL2-WT bound to Sonrotoclax system. Time series of temperature, total energy, pressure, and box dimensions confirming stable simulation conditions for the WT–Sonrotoclax systems.

Figure 6.

Energy and equilibration of BCL2-WT bound to Sonrotoclax system. Time series of temperature, total energy, pressure, and box dimensions confirming stable simulation conditions for the WT–Sonrotoclax systems.

Figure 7.

Ligand and pocket RMSD of the BCL2-WT–Sonrotoclax complex. RMSD of BH3 pocket residues and Sonrotoclax across three trajectories, indicating a rigid groove and ligand pose remodeling within the pocket rather than complete dissociation.

Figure 7.

Ligand and pocket RMSD of the BCL2-WT–Sonrotoclax complex. RMSD of BH3 pocket residues and Sonrotoclax across three trajectories, indicating a rigid groove and ligand pose remodeling within the pocket rather than complete dissociation.

Figure 8.

RMSF of BCL2-WT and Sonrotoclax. Per-residue RMSF of BCL-2 and atom-wise RMSF of Sonrotoclax showing very low flexibility in pocket residues and higher mobility in solvent-exposed ligand substituents.

Figure 8.

RMSF of BCL2-WT and Sonrotoclax. Per-residue RMSF of BCL-2 and atom-wise RMSF of Sonrotoclax showing very low flexibility in pocket residues and higher mobility in solvent-exposed ligand substituents.

Figure 9.

SASA and BSA time series for BCL2-WT–Sonrotoclax. Protein, ligand, and complex SASA traces and corresponding BSA distribution demonstrating a consistently well-buried interface with modest fluctuations over 600 ns.

Figure 9.

SASA and BSA time series for BCL2-WT–Sonrotoclax. Protein, ligand, and complex SASA traces and corresponding BSA distribution demonstrating a consistently well-buried interface with modest fluctuations over 600 ns.

Figure 10.

State-dependent interaction rewiring of Sonrotoclax at the BCL2-WT BH3 pocket. The top figure shows schematic representations of BH3-bound (left) and non-BH3 (right) binding modes of Sonrotoclax derived from state-resolved PROLIF analysis. In the BH3-bound state, Sonrotoclax is anchored by LEU209 with supporting contacts from ASN192, ALA197, and LEU201, consistent with a compact canonical BH3 engagement. In non-BH3 states, the interaction pattern shifts toward LEU201, PHE212, ASP191, PRO204, and additional pocket residues, with LEU209 playing a reduced role, reflecting a switch to alternative stabilization networks. The bottom figure presents a residue role-transition heatmap summarizing state-dependent changes in Sonrotoclax–BCL2-WT contacts. Negative values (blue) indicate residues preferentially engaged in BH3 states, such as LEU209, ASN192, ALA197, GLU200, while positive values (red) highlight residues more frequently contacted in non-BH3 states, including LEU201, PHE212, ASP191, ASP140, VAL142, PRO204, SER205, providing a compact quantitative “role-switch” summary as Sonrotoclax transitions from canonical BH3 anchoring to non-canonical binding modes.

Figure 10.

State-dependent interaction rewiring of Sonrotoclax at the BCL2-WT BH3 pocket. The top figure shows schematic representations of BH3-bound (left) and non-BH3 (right) binding modes of Sonrotoclax derived from state-resolved PROLIF analysis. In the BH3-bound state, Sonrotoclax is anchored by LEU209 with supporting contacts from ASN192, ALA197, and LEU201, consistent with a compact canonical BH3 engagement. In non-BH3 states, the interaction pattern shifts toward LEU201, PHE212, ASP191, PRO204, and additional pocket residues, with LEU209 playing a reduced role, reflecting a switch to alternative stabilization networks. The bottom figure presents a residue role-transition heatmap summarizing state-dependent changes in Sonrotoclax–BCL2-WT contacts. Negative values (blue) indicate residues preferentially engaged in BH3 states, such as LEU209, ASN192, ALA197, GLU200, while positive values (red) highlight residues more frequently contacted in non-BH3 states, including LEU201, PHE212, ASP191, ASP140, VAL142, PRO204, SER205, providing a compact quantitative “role-switch” summary as Sonrotoclax transitions from canonical BH3 anchoring to non-canonical binding modes.

Figure 11.

Energy and equilibration profiles for BCL2-G101V bound to Venetoclax.

Figure 11.

Energy and equilibration profiles for BCL2-G101V bound to Venetoclax.

Figure 12.

Pocket and ligand RMSD of Venetoclax in complex with BCL2-G101V.

Figure 12.

Pocket and ligand RMSD of Venetoclax in complex with BCL2-G101V.

Figure 13.

RMSF of BCL2-G101V and Venetoclax. RMSF profiles of mutant BCL-2 and Venetoclax demonstrating stable pocket residues, flexible termini/loops, and modest ligand flexibility concentrated in peripheral groups.

Figure 13.

RMSF of BCL2-G101V and Venetoclax. RMSF profiles of mutant BCL-2 and Venetoclax demonstrating stable pocket residues, flexible termini/loops, and modest ligand flexibility concentrated in peripheral groups.

Figure 14.

Time evolution of SASA and BSA for BCL2-G101V–Venetoclax.

Figure 14.

Time evolution of SASA and BSA for BCL2-G101V–Venetoclax.

Figure 15.

State-dependent interaction rewiring of Venetoclax at the BCL2-G101V BH3 pocket. Top: Shows schematic interaction networks for Venetoclax in the BH3 (left) and NON-BH3 (right) states of BCL2-G101V. In the BH3 state, Venetoclax stays anchored by key groove residues LEU209 and LEU201, with additional contacts to PHE212, PHE210, ASN192, ALA197, ASP191, and GLU200, suggesting the mutant can still support a near-native binding mode temporarily. In the NON-BH3 state, interactions with LEU209, LEU201, ASN192, and ALA197 persist, but the network shifts toward an alternative surface involving CYS229, GLY233, ALA60, SER62, GLY227, and ARG63, indicating partial ligand migration away from the main BH3 pocket. Edge styles and colors represent interaction types (black solid = hydrophobic/VdW, magenta dotted = cationic/polar, blue dashed = H-bond, red dash-dot = mixed). Bottom: presents a heatmap summarizing the log₂(non-BH3 / BH3) contact frequencies for key residues. The diverging color scale from blue to red emphasizes residues that are relatively enriched in BH3 (blue; e.g., LEU209, LEU201, PHE212) versus those mainly involved in NON-BH3 states (red; e.g., CYS229, GLY233, ALA60, SER62, GLY227, ARG63). Collectively, the panels demonstrate how the G101V mutation enables Venetoclax to maintain weaker anchoring at the BH3 groove while promoting a non-canonical, solvent-exposed binding site that may contribute to resistance.

Figure 15.

State-dependent interaction rewiring of Venetoclax at the BCL2-G101V BH3 pocket. Top: Shows schematic interaction networks for Venetoclax in the BH3 (left) and NON-BH3 (right) states of BCL2-G101V. In the BH3 state, Venetoclax stays anchored by key groove residues LEU209 and LEU201, with additional contacts to PHE212, PHE210, ASN192, ALA197, ASP191, and GLU200, suggesting the mutant can still support a near-native binding mode temporarily. In the NON-BH3 state, interactions with LEU209, LEU201, ASN192, and ALA197 persist, but the network shifts toward an alternative surface involving CYS229, GLY233, ALA60, SER62, GLY227, and ARG63, indicating partial ligand migration away from the main BH3 pocket. Edge styles and colors represent interaction types (black solid = hydrophobic/VdW, magenta dotted = cationic/polar, blue dashed = H-bond, red dash-dot = mixed). Bottom: presents a heatmap summarizing the log₂(non-BH3 / BH3) contact frequencies for key residues. The diverging color scale from blue to red emphasizes residues that are relatively enriched in BH3 (blue; e.g., LEU209, LEU201, PHE212) versus those mainly involved in NON-BH3 states (red; e.g., CYS229, GLY233, ALA60, SER62, GLY227, ARG63). Collectively, the panels demonstrate how the G101V mutation enables Venetoclax to maintain weaker anchoring at the BH3 groove while promoting a non-canonical, solvent-exposed binding site that may contribute to resistance.

Figure 16.

Energy and equilibration profiles for BCL2-G101V bound to Sonrotoclax.

Figure 16.

Energy and equilibration profiles for BCL2-G101V bound to Sonrotoclax.

Figure 17.

RMSD of BH3 pocket residues and Sonrotoclax in the BCL2-G101V complex.

Figure 17.

RMSD of BH3 pocket residues and Sonrotoclax in the BCL2-G101V complex.

Figure 18.

RMSF of BCL2-G101V and Sonrotoclax.

Figure 18.

RMSF of BCL2-G101V and Sonrotoclax.

Figure 19.

SASA and BSA profiles for BCL2-G101V–Sonrotoclax demonstrating persistent burial.

Figure 19.

SASA and BSA profiles for BCL2-G101V–Sonrotoclax demonstrating persistent burial.

Figure 20.

Residue role-change heatmap for BCL2-G101V with Sonrotoclax. This figure presents a residue-resolved heatmap of interaction frequencies for BCL2-G101V-Sonrotoclax, comparing the rare BH3-bound state (top row) with the predominant non-BH3-bound state (bottom row). The x-axis lists key pocket and alternative-network residues (LEU209, LEU201, PHE212, PHE210, ASN192, SER205, PRO208, ASP191, ASP140, VAL142, ALA197, GLU200). The color scale indicates the percentage of frames in which each residue interacts with the ligand (from white = 0% to dark blue = highest occupancy). LEU209 remains a dominant anchor in both states, while canonical BH3-supporting residues such as LEU201 and PHE210 show reduced or more uneven engagement outside the BH3 state. Conversely, residues like SER205 and PRO208 mainly appear in the non-BH3 state, highlighting the alternative stabilization network that supports non-productive surface binding in the G101V mutant.

Figure 20.

Residue role-change heatmap for BCL2-G101V with Sonrotoclax. This figure presents a residue-resolved heatmap of interaction frequencies for BCL2-G101V-Sonrotoclax, comparing the rare BH3-bound state (top row) with the predominant non-BH3-bound state (bottom row). The x-axis lists key pocket and alternative-network residues (LEU209, LEU201, PHE212, PHE210, ASN192, SER205, PRO208, ASP191, ASP140, VAL142, ALA197, GLU200). The color scale indicates the percentage of frames in which each residue interacts with the ligand (from white = 0% to dark blue = highest occupancy). LEU209 remains a dominant anchor in both states, while canonical BH3-supporting residues such as LEU201 and PHE210 show reduced or more uneven engagement outside the BH3 state. Conversely, residues like SER205 and PRO208 mainly appear in the non-BH3 state, highlighting the alternative stabilization network that supports non-productive surface binding in the G101V mutant.

Table 1.

Pooled MM/GBSA-GB energies (WT-Venetoclax, runs 1–3, UNBOUND removed in runs 1 & 3).

Table 1.

Pooled MM/GBSA-GB energies (WT-Venetoclax, runs 1–3, UNBOUND removed in runs 1 & 3).

| Energy Component |

Average (kcal/mol) |

Standard Deviation (kcal/mol) |

| Van der Waals (VdW) |

-24.80 |

12.37 |

| Electrostatic (EEL) |

-13.09 |

11.00 |

| Polar Solvation (EGB) |

24.07 |

14.02 |

| Non-polar Solvation (ESURF) |

-3.50 |

1.77 |

| Total Binding Energy (Total)¹ |

-17.32 |

9.56 |

Table 2.

Pooled MM/GBSA-GB energies (WT-Sonrotoclax, runs 1–3, UNBOUND removed in runs 1 & 3).

Table 2.

Pooled MM/GBSA-GB energies (WT-Sonrotoclax, runs 1–3, UNBOUND removed in runs 1 & 3).

| Energy Component |

Average (kcal/mol) |

Standard Deviation (kcal/mol) |

| Van der Waals (VdW) |

-28.01 |

15.04 |

| Electrostatic (EEL) |

-12.38 |

11.99 |

| Polar Solvation (EGB) |

25.92 |

16.79 |

| Non-polar Solvation (ESURF) |

-3.81 |

2.03 |

| Total Binding Energy (TOTAL) |

-18.29 |

10.26 |

Table 3.

Pooled MM/GBSA-GB energies (G101V–venetoclax, runs 1–3, UNBOUND removed in runs 1 & 3).

Table 3.

Pooled MM/GBSA-GB energies (G101V–venetoclax, runs 1–3, UNBOUND removed in runs 1 & 3).

| Energy Component |

Average (kcal/mol) |

Standard Deviation (kcal/mol) |

| Van der Waals (VdW) |

-26.09 |

7.86 |

| Electrostatic (EEL) |

-10.41 |

8.99 |

| Polar Solvation (EGB) |

23.49 |

9.89 |

| Non-polar Solvation (ESURF) |

-3.53 |

1.03 |

| Total Binding Energy (Total) |

-16.54 |

6.25 |

Table 4.

Pooled MM/GBSA-GB energies (G101V–Sonrotoclax, runs 1–3, UNBOUND removed in runs 1 & 3).

Table 4.

Pooled MM/GBSA-GB energies (G101V–Sonrotoclax, runs 1–3, UNBOUND removed in runs 1 & 3).

| Energy Component |

Average (kcal/mol) |

Standard Deviation (kcal/mol) |

| Van der Waals (VdW) |

-33.53 |

11.64 |

| Electrostatic (EEL) |

-12.91 |

13.43 |

| Polar Solvation (EGB) |

29.88 |

14.99 |

| Non-polar Solvation (ESURF) |

-4.43 |

1.51 |

| Total Binding Energy (Total) |

-20.99 |

8.06 |