Submitted:

04 January 2026

Posted:

07 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

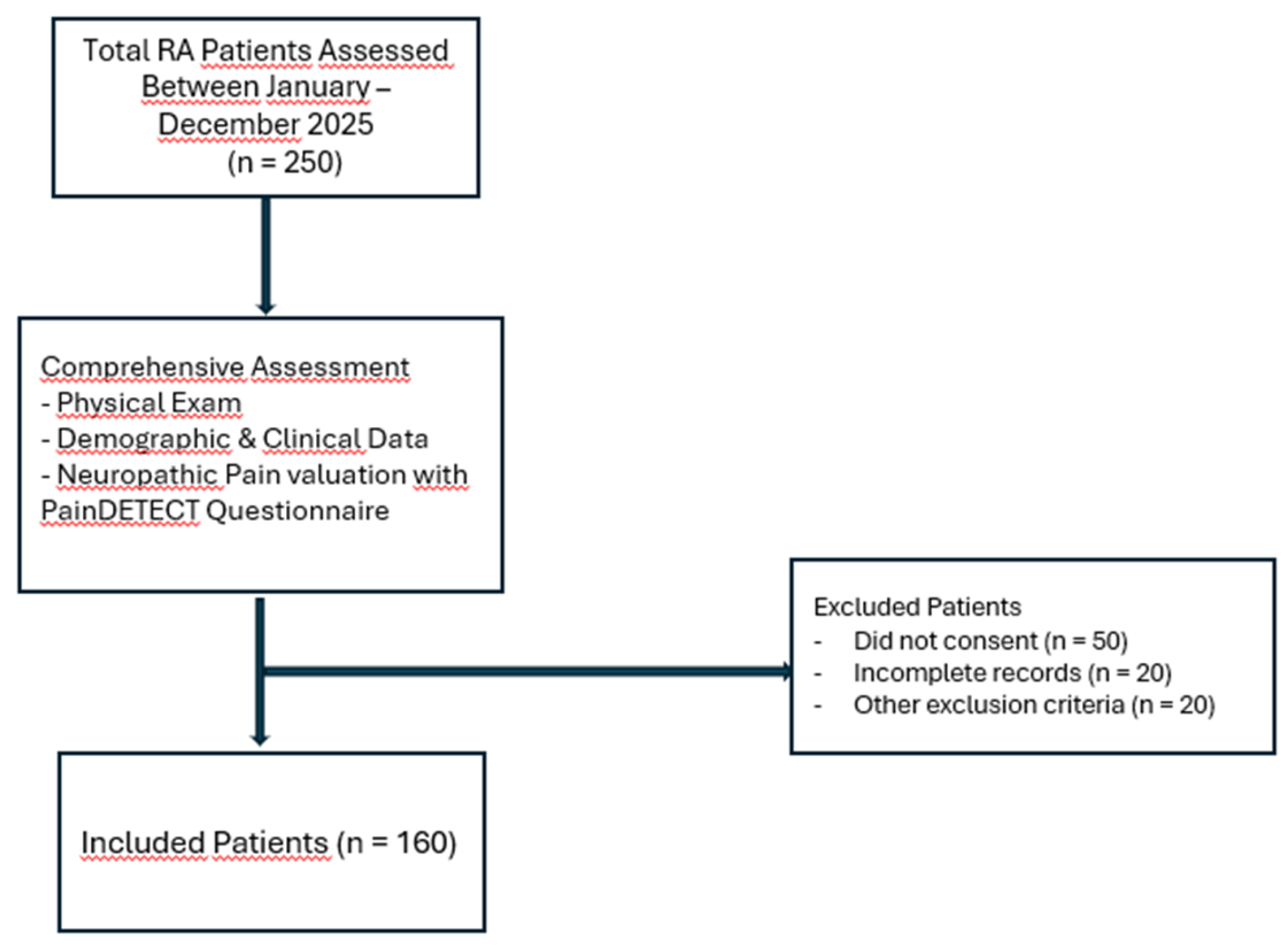

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Ethics

Study Population

Clinical and Laboratory Assessment

Patient-Reported Outcome Measures

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SD: | Standard Deviation |

| BMI: | Body Mass Index |

| IQR: | Interquartile Range |

| csDMARDs: | Conventional Synthetic Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs |

| DMARD: | Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drug |

| TNFi / TNF: | Tumor Necrosis Factor Inhibitors |

| JAKi / JAK: | Janus Kinase Inhibitors |

| DAS28: | Disease Activity Score in 28 Joints |

| CRP: | C-Reactive Protein |

| ESR: | Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate |

| VAS: | Visual Analogue Scale |

| FACIT-F: | Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Fatigue |

| PSQI: | Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index |

| SF-36: | 36-Item Short Form Health Survey |

| PF: | Physical Functioning |

| RP: | Role Physical |

| RE: | Role Emotional |

| VT: | Vitality |

| SF: | Social Functioning |

| MH: | Mental Health |

| BP: | Bodily Pain |

| GH: | General Health |

References

- Zhang A, Lee YC. Mechanisms for Joint Pain in Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA): from Cytokines to Central Sensitization. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2018 Oct;16(5):603-610. [CrossRef]

- Perniola S, Bruno D, Di Mario C, Campobasso D, Calabretta M, Gessi M, Petricca L, Tolusso B, Alivernini S, Gremese E. Residual pain and fatigue are affected by disease perception in rheumatoid arthritis in sustained clinical and ultrasound remission. Clin Rheumatol. 2025 Mar;44(3):1019-1029. [CrossRef]

- Walsh DA, McWilliams DF. Pain in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2012 Dec;16(6):509-17. [CrossRef]

- Das D, Choy E. Non-inflammatory pain in inflammatory arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2023 Jul 5;62(7):2360-2365. [CrossRef]

- Minhas D, Murphy A, Clauw DJ. Fibromyalgia and centralized pain in the rheumatoid arthritis patient. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2023 May 1;35(3):170-174. [CrossRef]

- Lee YC, Cui J, Lu B, Frits ML, Iannaccone CK, Shadick NA, Weinblatt ME, Solomon DH. Pain persists in DAS28 rheumatoid arthritis remission but not in ACR/EULAR remission: a longitudinal observational study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011 Jun 8;13(3):R83. [CrossRef]

- Trouvin AP, Attal N, Perrot S. Assessing central sensitization with quantitative sensory testing in inflammatory rheumatic diseases: A systematic review. Joint Bone Spine. 2022 Oct;89(5):105399. [CrossRef]

- Koop SM, ten Klooster PM, Vonkeman HE, Steunebrink LM, van de Laar MA. Neuropathic-like pain features and cross-sectional associations in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015 Sep 3;17(1):237. [CrossRef]

- Kelleher EM, Meouchi R, Irani A. Beyond Inflammation: Why Understanding the Brain Matters in Inflammatory Arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2025 Nov 14. [CrossRef]

- Georgopoulos V, Smith S, McWilliams DF, Ferguson E, Wakefield R, Platts D, Ledbury S, Wilson D, Walsh DA. Contribution of inflammation markers and quantitative sensory testing (QST) indices of central sensitisation to rheumatoid arthritis pain. Arthritis Res Ther. 2024 Oct 8;26(1):175. [CrossRef]

- Belančić A, Sener S, Sener YZ, Fajkić A, Vučković M, Markotić A, Benić MS, Potočnjak I, Pavlović MR, Radić J, Radić M. Effects of Janus Kinase Inhibitors on Rheumatoid Arthritis Pain: Clinical Evidence and Mechanistic Pathways. Biomedicines. 2025 Oct 5;13(10):2429. [CrossRef]

- Taylor PC, Lee YC, Fleischmann R, Takeuchi T, Perkins EL, Fautrel B, Zhu B, Quebe AK, Gaich CL, Zhang X, Dickson CL, Schlichting DE, Patel H, Durand F, Emery P. Achieving Pain Control in Rheumatoid Arthritis with Baricitinib or Adalimumab Plus Methotrexate: Results from the RA-BEAM Trial. J Clin Med. 2019 Jun 12;8(6):831. [CrossRef]

- McWilliams DF, Walsh DA. Pain mechanisms in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2017 Sep-Oct;35 Suppl 107(5):94-101. Epub 2017 Sep 29. PMID: 28967354.

- Tański W, Szalonka A, Tomasiewicz B. Quality of Life and Depression in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients Treated with Biologics - A Single Centre Experience. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2022 Mar 3;15:491-501. [CrossRef]

- Vergne-Salle P, Pouplin S, Trouvin AP, Bera-Louville A, Soubrier M, Richez C, Javier RM, Perrot S, Bertin P. The burden of pain in rheumatoid arthritis: Impact of disease activity and psychological factors. Eur J Pain. 2020 Nov;24(10):1979-1989. [CrossRef]

- Fitzcharles MA, Shir Y. Management of chronic pain in the rheumatic diseases with insights for the clinician. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2011 Aug;3(4):179-90. [CrossRef]

- Sebba A. Pain: A Review of Interleukin-6 and Its Roles in the Pain of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Open Access Rheumatol. 2021 Mar 5;13:31-43. [CrossRef]

- Baerwald C, Stemmler E, Gnüchtel S, Jeromin K, Fritz B, Bernateck M, Adolf D, Taylor PC, Baron R. Predictors for severe persisting pain in rheumatoid arthritis are associated with pain origin and appraisal of pain. Ann Rheum Dis. 2024 Sep 30;83(10):1381-1388. [CrossRef]

- Alkan H, Ardic F, Erdogan C, Sahin F, Sarsan A, Findikoglu G. Turkish version of the painDETECT questionnaire in the assessment of neuropathic pain: a validity and reliability study. Pain Med. 2013 Dec;14(12):1933-43. [CrossRef]

- Webster K, Cella D, Yost K. The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) Measurement System: properties, applications, and interpretation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003 Dec 16;1:79. [CrossRef]

- Akman T, Yavuzsen T, Sevgen Z, Ellidokuz H, Yilmaz AU. Evaluation of sleep disorders in cancer patients based on Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2015 Jul;24(4):553-9. [CrossRef]

- Çelik D, Çoban Ö. Short Form Health Survey version-2.0 Turkish (SF-36v2) is an efficient outcome parameter in musculoskeletal research. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2016 Oct;50(5):558-561. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed S, Magan T, Vargas M, Harrison A, Sofat N. Use of the painDETECT tool in rheumatoid arthritis suggests neuropathic and sensitization components in pain reporting. J Pain Res. 2014 Oct 14;7:579-88. [CrossRef]

- Mesci N, Mesci E, Kandemir EU, Kulcu DG, Celik T. Impact of central sensitization on clinical parameters in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. North Clin Istanb. 2024 Apr 22;11(2):140-146. [CrossRef]

- Lee YC, Chibnik LB, Lu B, Wasan AD, Edwards RR, Fossel AH, Helfgott SM, Solomon DH, Clauw DJ, Karlson EW. The relationship between disease activity, sleep, psychiatric distress and pain sensitivity in rheumatoid arthritis: a cross-sectional study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(5):R160. [CrossRef]

- Rutter-Locher Z, Arumalla N, Norton S, Taams LS, Kirkham BW, Bannister K. A systematic review and meta-analysis of questionnaires to screen for pain sensitisation and neuropathic like pain in inflammatory arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2023 Aug;61:152207. [CrossRef]

- Berrichi I, Taik FZ, Haddani F, Soba N, Fourtassi M, Abourazzak FE. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Central Sensitization in Patients with Chronic Inflammatory Rheumatic Disease. Curr Rheumatol Rev. 2025;21(4):418-423. [CrossRef]

- Barnabe C, Bessette L, Flanagan C, Leclercq S, Steiman A, Kalache F, Kung T, Pope JE, Haraoui B, Hochman J, Mosher D, Thorne C, Bykerk V. Sex differences in pain scores and localization in inflammatory arthritis: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Rheumatol. 2012 Jun;39(6):1221-30. [CrossRef]

- Vogel K, Muhammad LN, Song J, Neogi T, Bingham CO, Bolster MB, Marder W, Wohlfahrt A, Clauw DJ, Dunlop D, Lee YC. Sex Differences in Pain and Quantitative Sensory Testing in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2023 Dec;75(12):2472-2480. [CrossRef]

- Sarzi-Puttini P, Zen M, Arru F, Giorgi V, Choy EA. Residual pain in rheumatoid arthritis: Is it a real problem? Autoimmun Rev. 2023 Nov;22(11):103423. [CrossRef]

- Rifbjerg-Madsen S, Christensen AW, Christensen R, Hetland ML, Bliddal H, Kristensen LE, Danneskiold-Samsøe B, Amris K. Pain and pain mechanisms in patients with inflammatory arthritis: A Danish nationwide cross-sectional DANBIO registry survey. PLoS One. 2017 Jul 7;12(7):e0180014. [CrossRef]

- Saitou M, Noda K, Matsushita T, Ukichi T, Kurosaka D. Central sensitisation features are associated with neuropathic pain-like symptoms in patients with longstanding rheumatoid arthritis: a cross-sectional study using the central sensitisation inventory. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2022 May;40(5):980-987. [CrossRef]

- Cao Y, Fan D, Yin Y. Pain Mechanism in Rheumatoid Arthritis: From Cytokines to Central Sensitization. Mediators Inflamm. 2020 Sep 12;2020:2076328. [CrossRef]

- Paroli M, Sirinian MI. Pathogenic Crosstalk Between the Peripheral and Central Nervous System in Rheumatic Diseases: Emerging Evidence and Clinical Implications. Int J Mol Sci. 2025 Jun 24;26(13):6036. [CrossRef]

- Chimenti RL, Frey-Law LA, Sluka KA. A Mechanism-Based Approach to Physical Therapist Management of Pain. Phys Ther. 2018 May 1;98(5):302-314. [CrossRef]

- Bäckryd E, Ghafouri N, Gerdle B, Dragioti E. Rehabilitation interventions for neuropathic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Rehabil Med. 2024 Aug 5;56:jrm40188. [CrossRef]

- Finan PH, Goodin BR, Smith MT. The association of sleep and pain: an update and a path forward. J Pain. 2013 Dec;14(12):1539-52. [CrossRef]

- Haack M, Simpson N, Sethna N, Kaur S, Mullington J. Sleep deficiency and chronic pain: potential underlying mechanisms and clinical implications. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020 Jan;45(1):205-216. [CrossRef]

| Variable | RA Patients (n=160) | |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 51.41 ± 13.48 | |

| Gender, n (%) | Female | 131 (81.8%) |

| Male | 29 (18.2%) | |

| BMI (kg/m²), mean ± SD | 27.56 ± 5.20 | |

| Education Level, n (%) | Illiterate | 49 (30.6%) |

| Primary | 55 (34.4%) | |

| Middle | 13 (8.1%) | |

| High School | 27 (16.9%) | |

| University | 16 (10.0%) | |

| Marital Status, n (%) | Single | 18 (11.3%) |

| Married | 123 (76.9%) | |

| Widowed | 19 (11.9%) | |

| Smoking Status, n (%) | Non-smoker | 121 (75.6%) |

| Smoker | 39 (24.4%) | |

| Disease duration (years), median (IQR) | 8,00 (0,75–40,00) | |

| Prescribed RA medications, n (%) | csDMARDs | 50 (31.2%) |

| Anti TNFi | 45 (28.1%) | |

| JAKi | 40 (25%) | |

| Rituximab | 5 (3.1%) | |

| Tocilizumab | 12 (7.5%) | |

| Abatacept: | 8 (5%) | |

| DAS28 (0–10), mean ± SD | 2.73 (0.77–6.35) | |

| DAS28, n (%) | <2,6 | 72 (45%) |

| 2,6–3,2 | 32 (20%) | |

| 3,2–5,1 | 45 (28.1%) | |

| >5,1 | 11 (6.9%) | |

| Neuropathic Pain , n (%) | Likely neuropathic pain | 36 (22.5%) |

| Unclear pain type | 24 (15%) | |

| Likely non-neuropathic pain | 100 (62.5%) | |

| Variable | Neuropathic Pain (+) Mean ± SD (n: 36) | Neuropathic Pain (–) Mean ± SD (n: 124) | p-value |

| Age (years) | 52.09 ± 13.64 | 51.19 ± 13.42 | 0.696 |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 27.28 ± 6.31 | 27.76 ± 5.01 | 0.593 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 11.40 ± 15.62 | 8.83 ± 15.58 | 0.341 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 20.43 ± 12.83 | 15.97 ± 13.99 | 0.051 |

| DAS28 | 2.87 ± 0.68 | 2.26 ± 0.86 | <0.001 |

| Tender joint count | 1.40 ± 2.07 | 2.16 ± 2.41 | 0.041 |

| Swollen joint count | 0.13 ± 0.50 | 0.15 ± 0.77 | 0.906 |

| Disease duration (years) | 9.58 ± 7.54 | 8.51 ± 7.44 | 0.34 |

| FACIT-F | 23.13 ± 11.89 | 38.19 ± 12.61 | <0.001 |

| PSQI | 10.80 ± 3.35 | 7.08 ± 3.79 | <0.001 |

| SF-36 PF | 57.56 ± 20.50 | 74.40 ± 19.07 | <0.001 |

| VAS (pain) | 60.89 ± 17.94 | 38.73 ± 18.58 | <0.001 |

| SF-36 RP | 15.00 ± 27.39 | 49.83 ± 41.42 | <0.001 |

| SF-36 RE | 38.52 ± 48.18 | 80.22 ± 38.64 | <0.001 |

| SF-36 VT | 28.78 ± 15.34 | 47.53 ± 20.44 | <0.001 |

| SF-36 SF | 52.50 ± 16.98 | 74.83 ± 18.71 | <0.001 |

| SF-36 MH | 54.93 ± 16.98 | 69.23 ± 16.81 | <0.001 |

| SF-36 BP | 34.56 ± 14.64 | 55.02 ± 20.14 | <0.001 |

| SF-36 GH | 22.78 ± 13.51 | 41.00 ± 18.76 | <0.001 |

| Variable | Neuropathic Pain (+) n : 36 (%) | Neuropathic Pain (–) n: 124 (%) | p-value |

| Sex | <0.001 | ||

| – Female | 29 (80.5%) | 102 (82.2%) | |

| – Male | 7 (19.5%) | 22 (7.8%) | |

| Smoking | 0.593 | ||

| – Non-smoker | 25 (69.4%) | 96 (77.4%) | |

| – Smoker | 11 (30.6%) | 28 (22.6%) | |

| Treatment Group | 0.707 | ||

| – JAK | 9 (25%) | 31 (25%) | |

| – TNF | 11 (30.5%) | 34 (27.4%) | |

| – DMARD | 12 (33.3%) | 38 (30.6%) | |

| – Others | 4 (11.2%) | 21 (17%) |

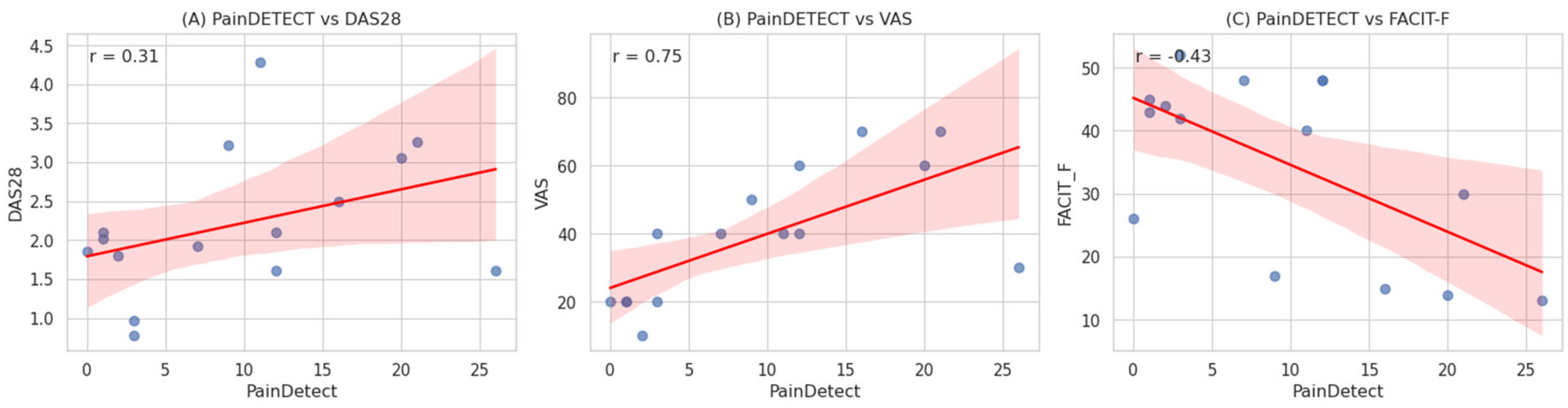

| Variable | r | p-value |

| DAS28 | 0.527 | <0.01 |

| VAS (pain) | 0.650 | <0.01 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 0.235 | <0.01 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 0.150 | <0.01 |

| FACIT-F (fatigue) | −0.456 | <0.01 |

| PSQI | 0.318 | <0.01 |

| SF-36 PF | −0.690 | <0.01 |

| SF-36 RP | −0.706 | <0.01 |

| SF-36 RE | −0.567 | <0.01 |

| SF-36 VT | −0.634 | <0.01 |

| SF-36 SF | −0.703 | <0.01 |

| SF-36 MH | −0.665 | <0.01 |

| SF-36 BP | −0.689 | <0.01 |

| SF-36 GH | −0.661 | <0.01 |

| Predictor | B | Std. Error | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) |

| Constant | -0.017 | 2.698 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.995 | 0.983 |

| Age | 0.007 | 0.019 | 0.121 | 1 | 0.728 | 1.007 |

| BMI | 0.037 | 0.042 | 0.780 | 1 | 0.377 | 1.038 |

| CRP | -0.001 | 0.014 | 0.002 | 1 | 0.962 | 0.999 |

| ESR | -0.005 | 0.022 | 0.050 | 1 | 0.823 | 0.995 |

| DAS28 | -0.138 | 0.464 | 0.089 | 1 | 0.766 | 0.871 |

| FACIT | 0.040 | 0.032 | 1.539 | 1 | 0.215 | 1.041 |

| VAS | 0.039 | 0.014 | 7.439 | 1 | 0.006 | 0.961 |

| SF36-PF | -0.008 | 0.017 | 0.204 | 1 | 0.652 | 0.992 |

| SF36-RP | 0.007 | 0.010 | 0.466 | 1 | 0.495 | 1.007 |

| SF36-RE | 0.001 | 0.007 | 0.013 | 1 | 0.910 | 1.001 |

| SF36-VT | -0.017 | 0.031 | 0.297 | 1 | 0.586 | 0.983 |

| SF36-MH | -0.011 | 0.022 | 0.226 | 1 | 0.634 | 0.989 |

| SF36-SF | 0.032 | 0.021 | 2.295 | 1 | 0.130 | 1.032 |

| SF36-BP | -0.001 | 0.022 | 0.002 | 1 | 0.961 | 0.999 |

| SF36-GH | 0.024 | 0.022 | 1.253 | 1 | 0.263 | 1.025 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).