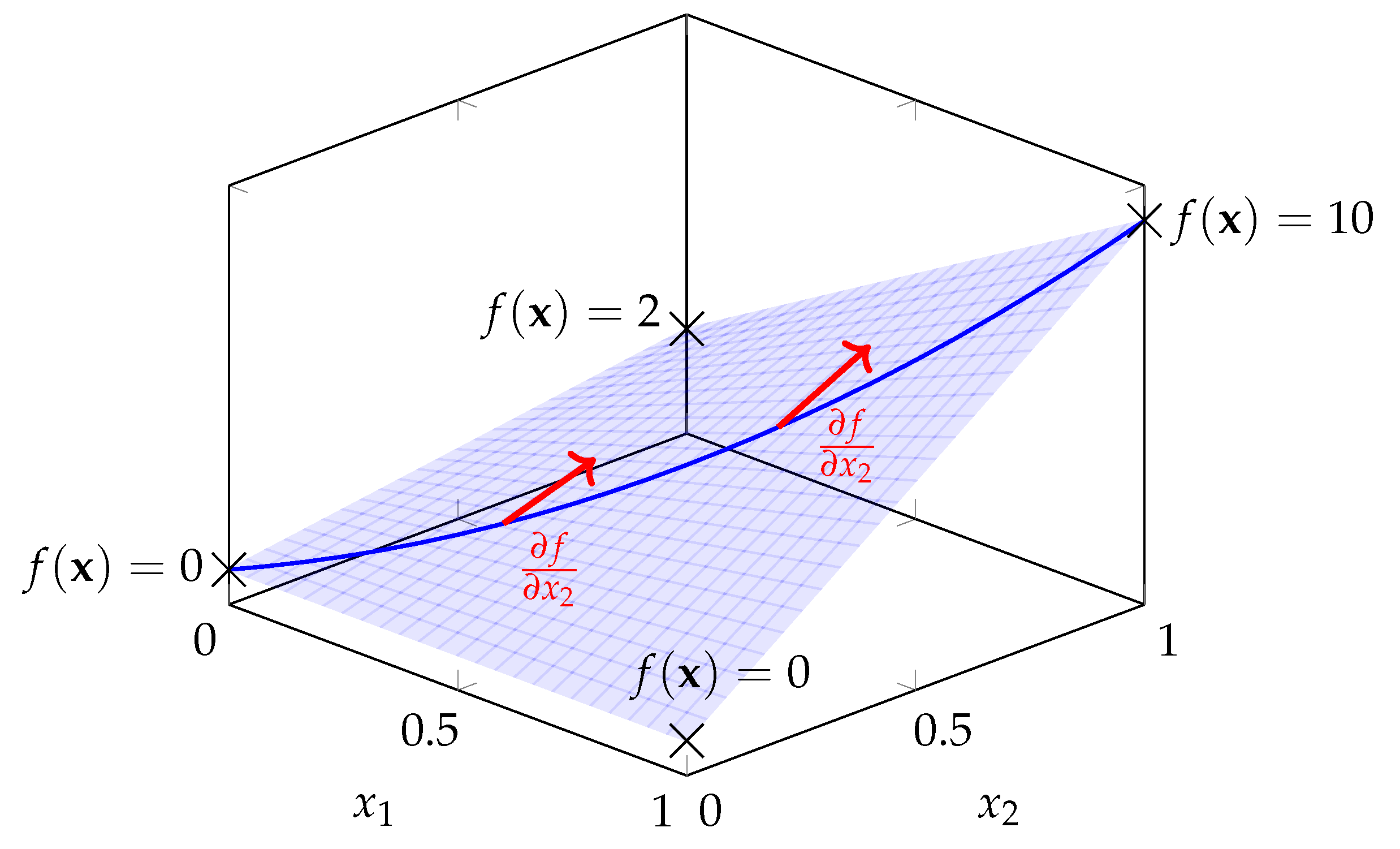

This section covers the idea of multilinear extensions of cooperative games and how this formulation of games can be used to approximate Shapley values of cooperative games. First, we provide a definition of multilinear extensions in

Section 5.1 and a representation of the Shapley value in their context in

Section 5.2. Afterwards, in

Section 5.3, we discuss an existing multilinear-extension-based approximation algorithm for the Shapley value which goes by the name Owen Sampling, was introduced in Okhrati and Lipani [

22] and is frequently applied in XAI applictions. Although it was previously noticed that Owen Sampling is biased, e.g. in [

12], we are the first to provide a detailed analysis of the bias. Then, we propose unbiased multilinear-extension-based algorithms in

Section 5.4 and

Section 5.5, with the latter subsection offering a stratified variant. These two unbiased multilinear-extension-based approaches serve as intermediary results for our investigations on the relations to our importance sampling framework on the coalition space from

Section 4.2. We discuss our results, conclusions and recommendations in the subsequent

Section 5.6 and

Section 5.7.

5.3. Owen Sampling (OS) for Computing Shapley Values According to Okhrati and Lipani

Since calculating (

30) or (

31) exactly requires

evaluations of

v, multilinear extensions cannot be used as an exact computation method for large

n when no a priori knowledge about the characteristic function is given, but instead serve as a starting point for the development of new approximation algorithms.

In this section, we introduce the

OS algorithm proposed by Okhrati and Lipani [

22]. To avoid confusion, we highlight that the name of this algorithm is based on Guillermo Owen, who published the idea of multilinear extensions of games [

20,

25] and defined the Shapley value in this setting [

20]. In particular, we emphasize that the algorithm is not related to the

Owen value [

32], a solution concept for cooperative games with a priori unions.

Okhrati and Lipani [

22] approximate (

29) by

with

being the discretization level. Note in passing that, contrary to the original algorithm in [

22], we adjusted the upper bound of the sum in (

32) from

Q to

to ensure that the sum includes exactly

Q terms, rather than

. Our adjustment is consistent with the source code provided with the original paper [

22] which is publicly available via

Since calculating

exactly in (

32) requires summing over all subsets

, the authors approximate (

31) by

whereby

denotes the

k-th sampled vector that is drawn according to the distribution from (

31) with all probabilities

for

being

, i.e.,

.

hereby is an additional parameter of the algorithm that specifies the number of evaluations per

q. Okhrati and Lipani [

22] fixed

for all

.

Thus, by combining (

32) and (

33), the estimator of the Shapley value for player

i is given by

It has been shown in the original paper Okhrati and Lipani [

22] that this estimator is consistent, i.e., for any

and

. Unfortunately, Okhrati and Lipani [

22] did not include a theoretical investigation of bias or variance. The bias of OS is discussed in [

12], where the authors concluded that OS is biased without giving a formal proof. We provide the latter in

Proposition 2. The OS estimator is biased, i.e., does not hold in the general case.

Proof. Let us fix an arbitrary player

whose Shapley value we want to estimate. We state that (

32) does not provide an unbiased approximation of (

29), resulting in a biased estimator

. To see this, consider the case

, where samples are drawn from

,

, and

, such that we have

Clearly, the last equality does not represent a valid relationship between the Shapley value and the Banzhaf value. E.g., consider a game with

players and the characteristic function

such that the Shapley values are given by

□

Proposition 2 establishes that the OS estimator is biased. (Formally, one might argue that Proposition 2 establishes the existence of a bias for the case

by counterexample. Although our proof is specific to this setting, the form of the OS estimator indicates that the bias persists for any finite

Q, see also the numerical results in [

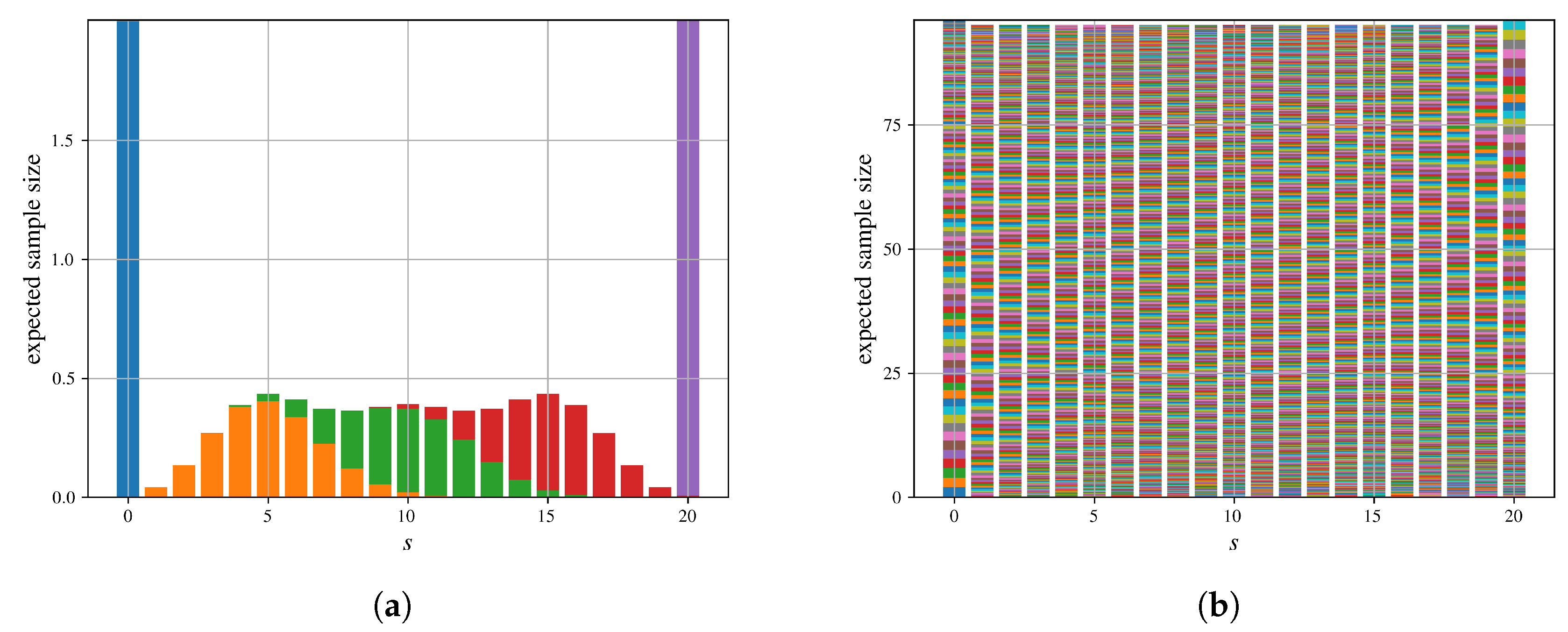

12]). The origin of that bias can be observed by visualizing the expected number of sampled coalitions per coalition size across different values of

Q, as illustrated in

Figure 2. Clearly, as

Q increases, the expected number of samples per coalition size approaches an equal distribution, as required by the Shapley definition. However, for the two finite values of

Q shown in

Figure 2, this equal distribution is never fully reached.

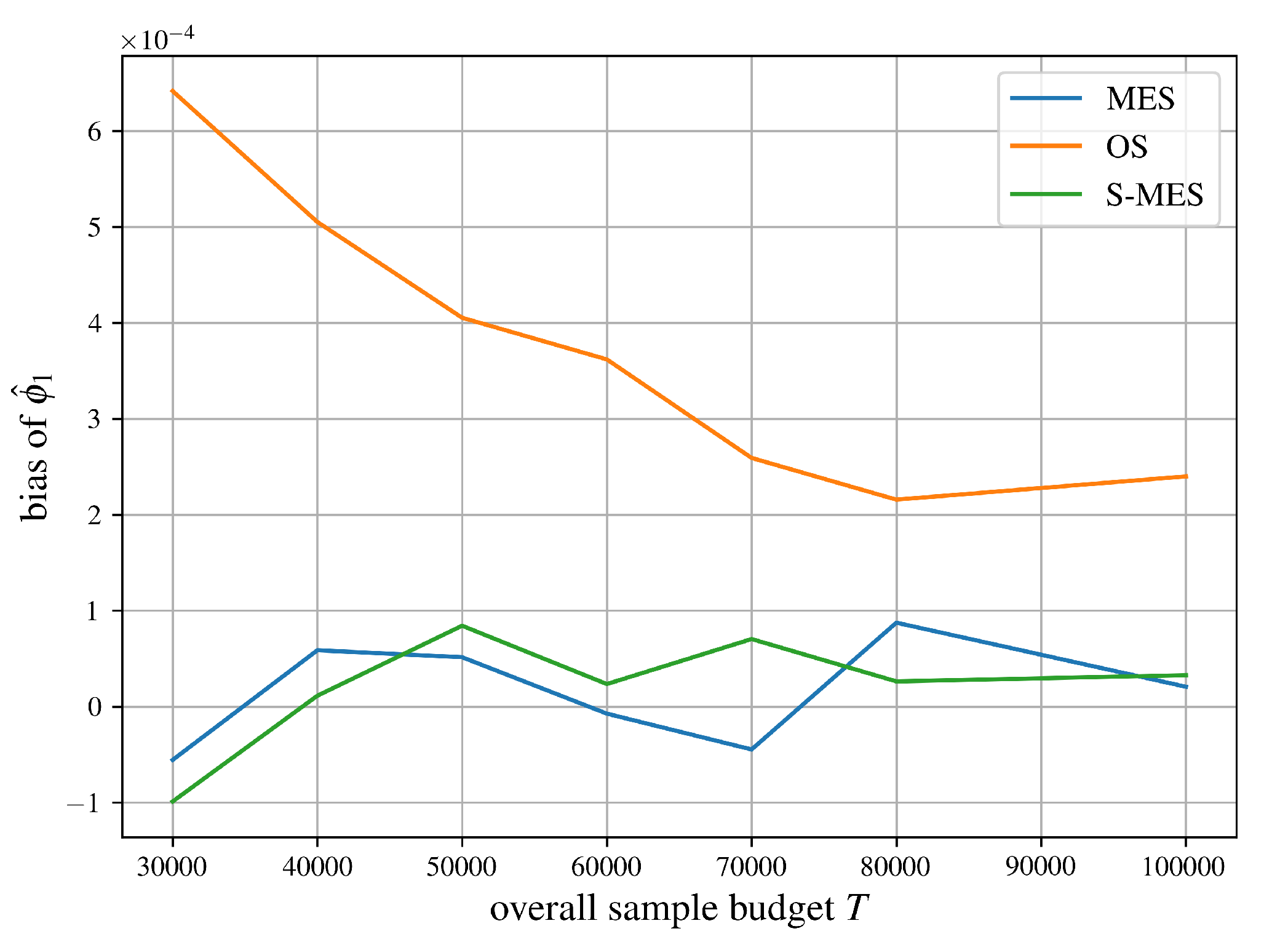

Additionally, we refer to

Figure 3 in

Section 6, which empirically validates the existence of a bias when executing OS.

Due to its biasedness, OS does not fit into the importance sampling framework defined by Theorem 1 since estimators of that framework are unbiased, see Proposition 1. Thus, we cannot use (

23) to calculate the variance of OS. As a solution, we propose an unbiased variant of OS in

Section 5.4, for which we will calculate the variance.

Algorithm 1 implements (

34) as a ready-to-use algorithm with some enhancements. When approximating the Shapley value of all players, these additional improvements reduce the number of evaluations of

v, and thus, increase convergence. In detail, by looking at Algorithm 1, one obtains that evaluations of

can be reused to update the Shapley value of each individual player, either as the minuend, if player

i is already included in the sampled coalition, or as the subtrahend, if excluded. Note that we force the exclusion of player

i in the subtrahend to avoid adding marginal contributions of zero. This approach reduces the number of evaluations of the characteristic function per iteration in line 3 from

to

. We use this implementation when comparing variances and convergence speeds in

Section 6.2.

|

Algorithm 1:OS |

- 1:

- 2:

fordo

- 3:

for times do

- 4:

Draw

- 5:

- 6:

for do

- 7:

if then

- 8:

- 9:

else

- 10:

- 11:

end if

- 12:

end for

- 13:

end for

- 14:

end for - 15:

|

Concluding this subsection, we highlight two more details. First, we note that approximations of the integral in (

29) other than (

32) have also been proposed. Mitchell et al. [

33] mentioned that they used the trapezoidal rule in their implementation of OS. On the other hand, Chen et al. [

12] mentioned that sampling

at random to approximate (

29) provides an unbiased estimator. While we assume the former variant to be biased as well, we will further study the latter approach in

Section 5.4.

Second, another algorithm proposed by Okhrati and Lipani [

22] called

halved Owen sampling uses antithetic sampling as a variance reduction technique [

12,

28,

34]. However, this method lies outside the scope of our paper. Similar to the OS estimator, the halved Owen sampling estimator remains biased. Rather than extending all following developments like the construction of an unbiased variant of OS to the antithetic case as well, we focus exclusively on the OS estimator. From the results of this paper, one could easily derive unbiased or stratified antithetic versions of OS. We refer to [

34] for more details on how unbiased antithetic variants of existing algorithms can be constructed.

5.4. Multilinear Extension Sampling for the Shapley Value (MES)

As discussed in the previous subsection, the OS estimator is biased, which motivates the introduction of two new unbiased variants of the estimator in this and the following subsection. Chen et al. [

12] proposed an algorithm called

random q as an alternative to OS. The idea is to sample points across the interval

at random, resulting in an unbiased estimator of the integral in (

29) even for small sample sizes. Although the authors refer to this algorithm at several points in their work, Chen et al. [

12], do not provide any theoretical analysis of their algorithm. This lack of theoretical grounding motivates a closer examination of

random q along with its advantages and limitations in comparison to other approaches.

From now on, we refer to this algorithm as

MES (for Multilinear Extension Sampling). In our implementation, we fix

due to the fact that we fail to see any justification in [

22] to set

. In particular, the authors stated in [

22] that the optimal choice of

is yet to be explored. In our opinion, there is no clear reason why the algorithm benefits from sampling more than one coalition for a given, sampled

q. Therefore, our proposed algorithm is controlled by one parameter

only, which specifies the number of random draws of

q and thus, implicitly, the number of sampled coalitions. The overall number of evaluations of

v is then given by

.

Proposition 3. The MES estimator is unbiased, i.e., .

Proof. Let us fix an arbitrary player

whose Shapley value we want to estimate. The sampling procedure of Algorithm 2 is equivalent to sampling

. Therefore, we obtain the estimator

where

denotes the

k-th sample obtained by first drawing

at random, and then sampling

.

Now, let

denote a random variable that is uniformly distributed across

with density

and concrete realizations

. Then,

whereby the closed-form solution of the integral directly comes from the beta function [

35,

36]. Note that we implicitly switched from vector notation to set notation in the step between (

36) and (

37), as described in

Section 2.1. □

|

Algorithm 2:MES |

- 1:

- 2:

fortimes do

- 3:

Draw

- 4:

Draw

- 5:

- 6:

for do

- 7:

if then

- 8:

- 9:

else

- 10:

- 11:

end if

- 12:

end for

- 13:

end for - 14:

|

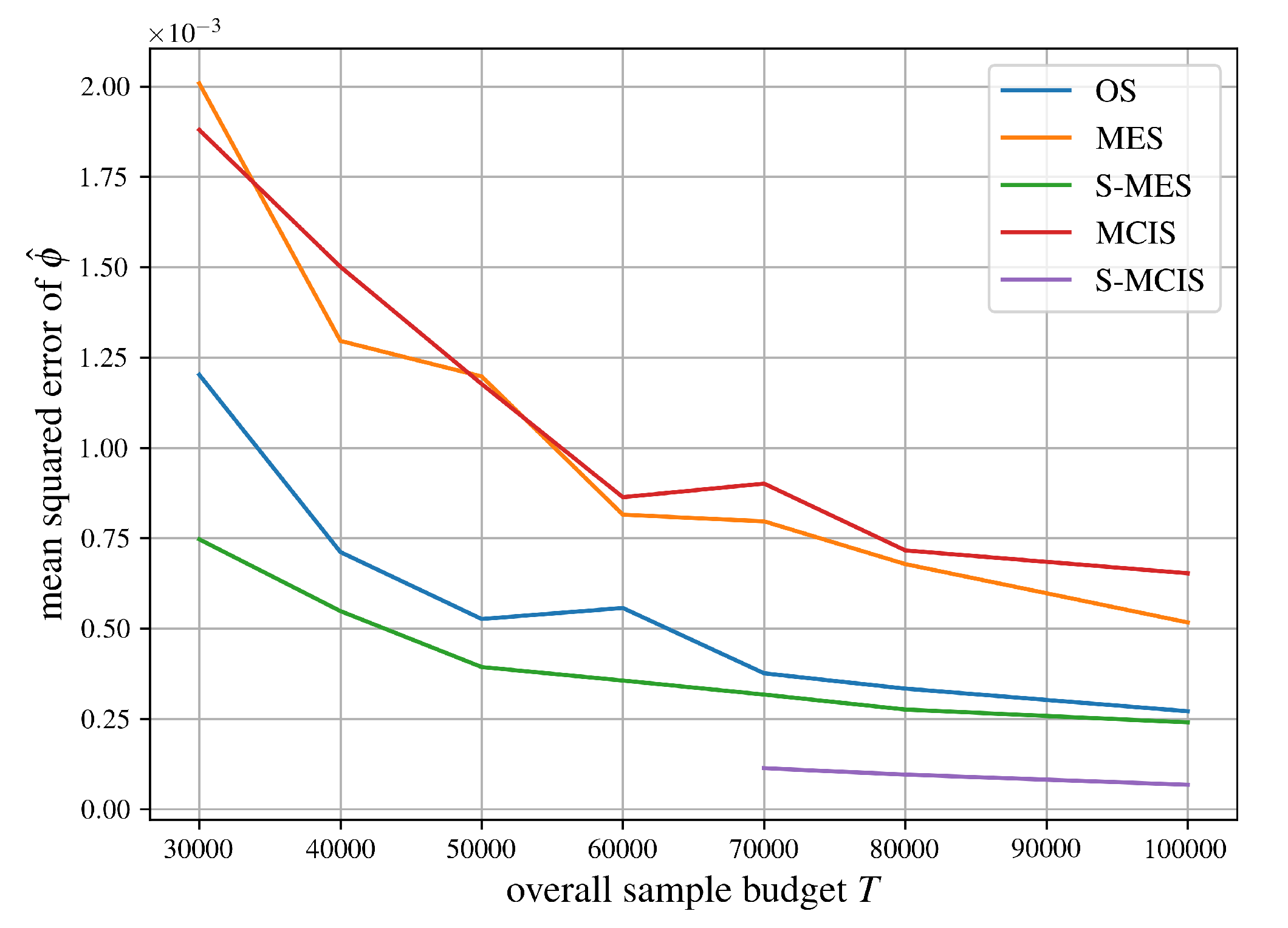

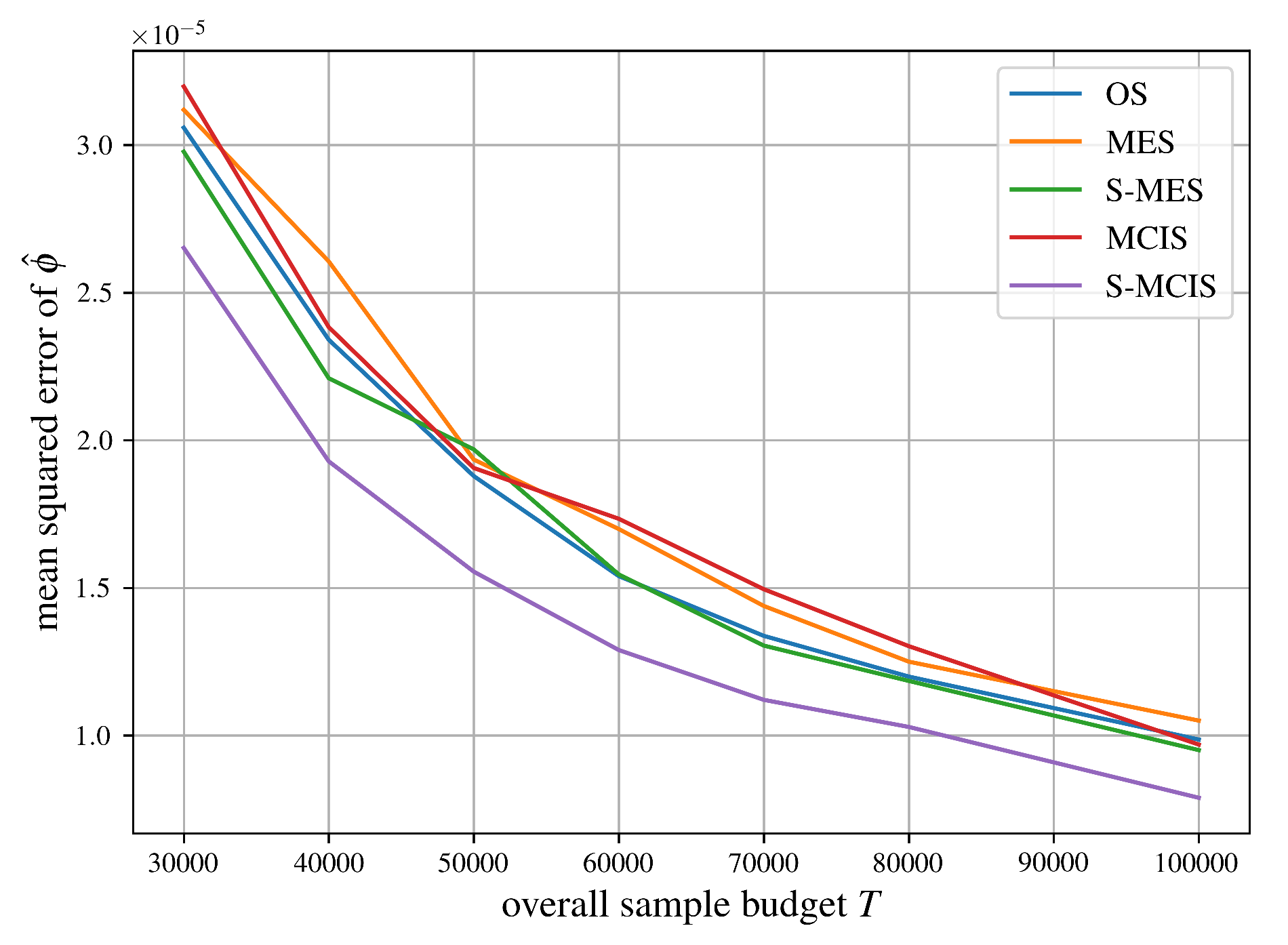

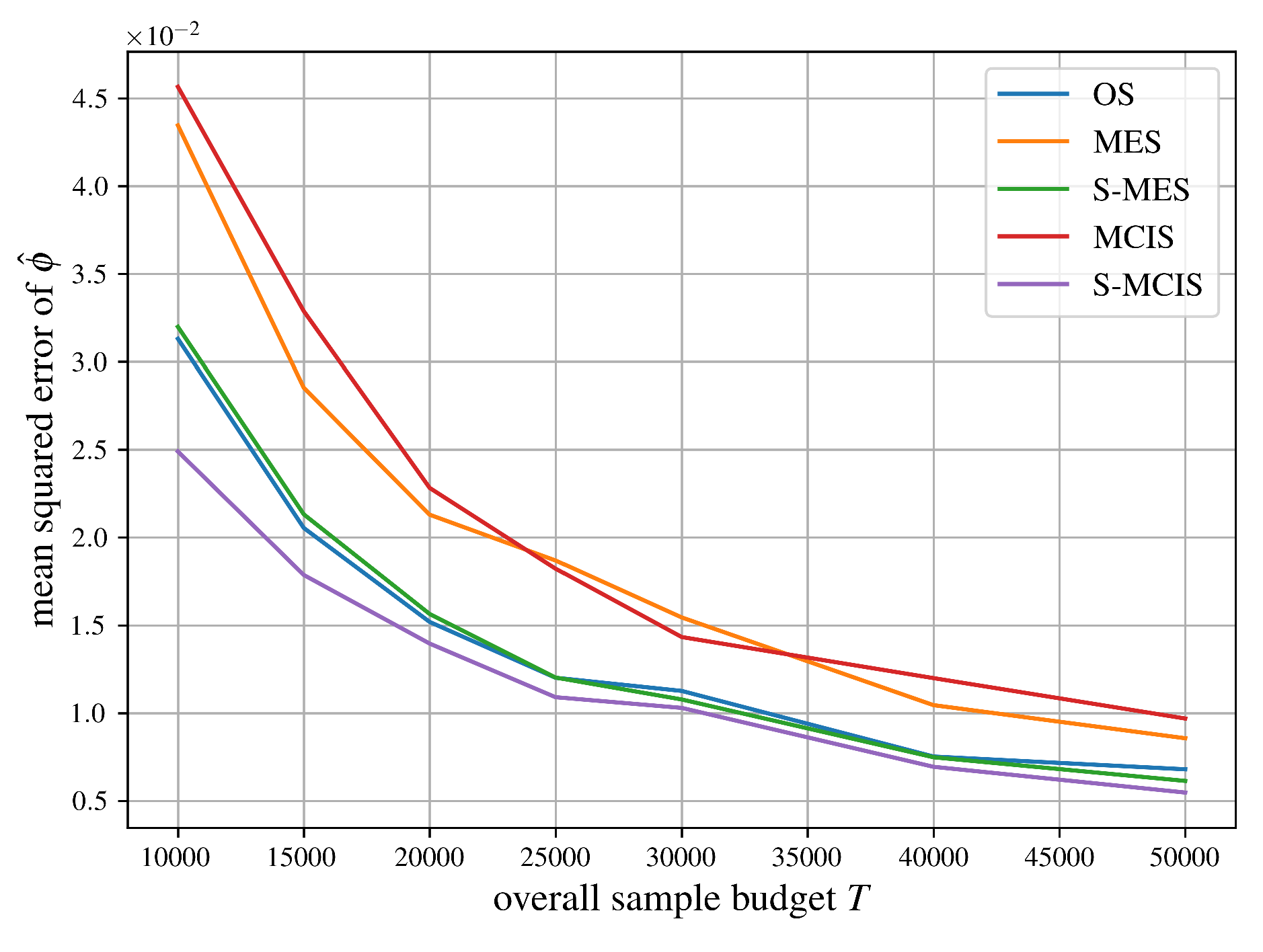

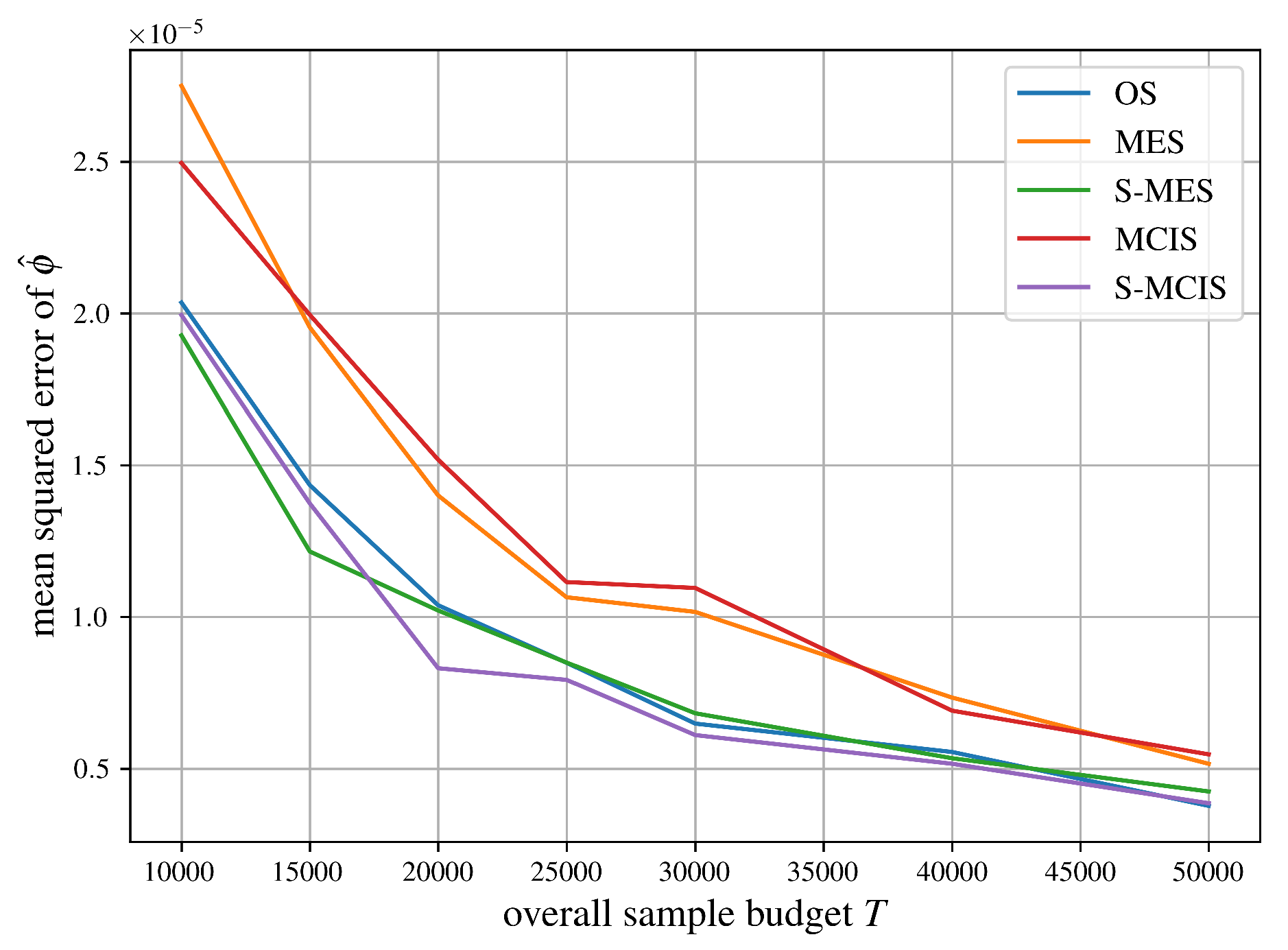

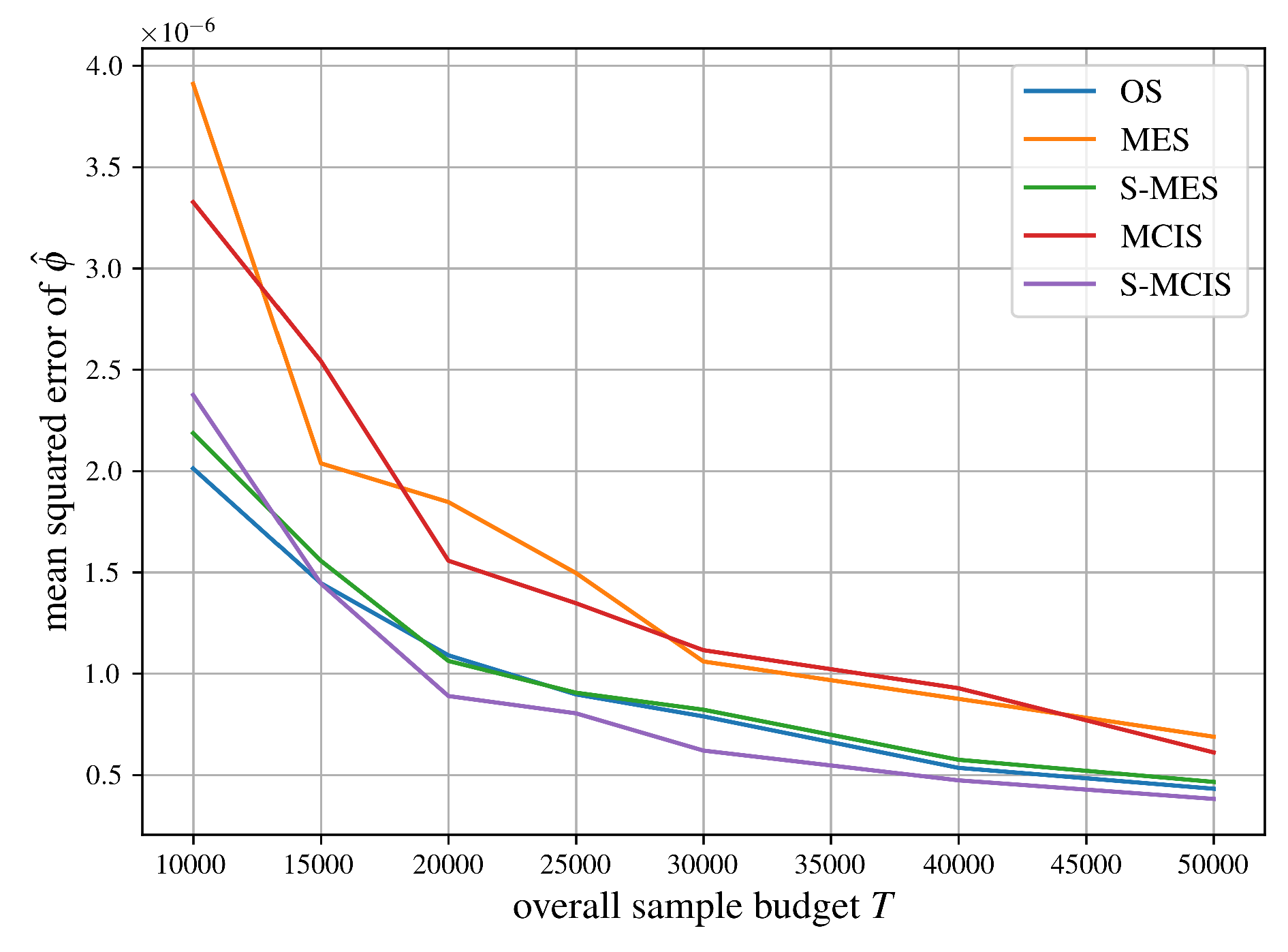

Empirical data given in

Figure 3 in

Section 6 supports the claim that MES is unbiased. Additionally, it is worth noting that MES may perform worse than OS, as shown in

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9. We attribute this observation to the fact that OS generates its

q-values systematically, which probably helps reduce its variance. Although we will later derive a theoretical variance for the MES estimator (see Corollary 1), we cannot compare it to OS since a theoretical variance analysis for OS has not been performed yet.

5.6. Comparison of MES and Marginal Contribution Importance Sampling (MCIS)

Let us revisit the marginal contribution importance sampling (MCIS) approach for the Shapley value defined by (

27), which we introduced at the end of

Section 4.2 in the context of our importance sampling framework on the coalition space. We observe

Theorem 2. MES is the same importance sampling estimator as MCIS.

Proof. Per definition, MCIS is an importance sampling estimator.

Now, let us fit the MES algorithm into the importance sampling framework from Theorem 1. From (

35), one obtains that it is based on marginal contributions as well, such that we have

.

Furthermore, from (

35), we retrieve

, if

. For the case

, we derive

whereby the last equality directly follows from the proof of Proposition 3, which is why we omit any intermediate steps here.

Since MES updates the estimator by adding with factor 1 (see Algorithm 2), we have , and thus, .

As a result, via (

26), one obtains

and that completes the proof. □

Proposition 5.

The variance of the MCIS estimator is given by

Proof. The proof is straightforward by inserting

,

, and

into (

23). □

Corollary 1.

The variance of the MES estimator is given by

Proof. The proof is straightforward taking into account that MES is the same estimator as MCIS (see Theorem 2) and the variance of MCIS is given by Proposition 5. □

We conclude: MCIS is unbiased, which can be obtained directly from Proposition 1 since MCIS belongs to the importance sampling framework defined by Theorem 1, and MES is unbiased, see Proposition 3. Additionally, via Proposition 5 and Corollary 1, we see that both algorithms share the same variance. As a result, we argue that the indirection introduced by Algorithm 2, i.e., sampling from the multilinear extension of v, does not have any advantages over sampling directly from the coalition space with probabilities .

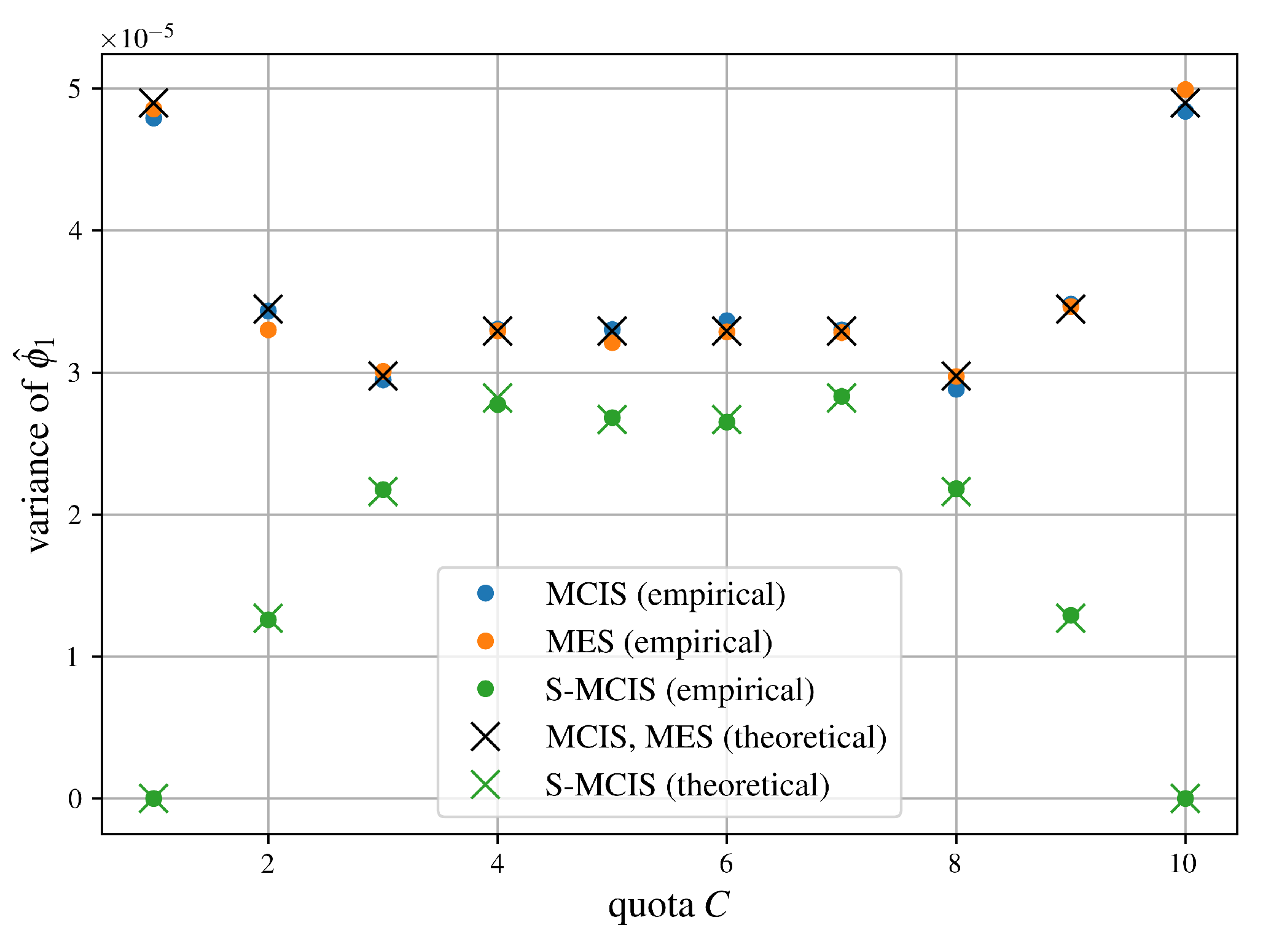

We refer to

Section 6, where

Figure 4 validates the proposed variances from Proposition 5 and Corollary 1.

To allow fair comparisons to other algorithms, we reuse evaluations of

v across players, as for all other algorithms. We refer to Algorithm 4 for a ready-to-use implementation of this improved variant, where the number of evaluations of

v is given by

and

is the adapted sampling distribution to achieve this improvement.

Proposition 6. In the context of Algorithm 4, (39) recovers the original sampling probabilities as defined in (26).

Proof. When sampling according to (

39), i.e.,

, the probability of sampling a subset of size

that can be used to update (

27) is given by

From (

40), we obtain that each coalition size without player

i is equally likely, as in (

26). Furthermore, from (

39), we see that each coalition has the same probability within equal-sized coalitions, such that sampling according to (

39) in Algorithm 4 is indeed equivalent to (

26). That completes the proof. □

|

Algorithm 4:MCIS |

- 1:

- 2:

fortimes do

- 3:

Draw

- 4:

- 5:

for do

- 6:

if then

- 7:

- 8:

else

- 9:

- 10:

end if

- 11:

end for

- 12:

end for - 13:

|

We acknowledge that Chen et al. [

12] already observed that MES is equivalent to sampling coalitions according to (

26), which aligns with our Theorem 2. This, however, does not diminish the novelty of our contribution. First, we establish MES within the general importance sampling framework proposed in Theorem 1. Second, the results in this subsection serve only as intermediate steps. While Chen et al. [

12] concluded that sampling

q at fixed intervals, as in the OS algorithm, outperforms MES and, therefore, MCIS, our contributions go beyond this: We develop an unbiased, stratified version of MES (named S-MES, see Algorithm 3) and compare it against other stratified sampling approaches (see

Section 5.7), resulting in new recommendations regarding the usage of multilinear extensions for approximating Shapley values.

5.7. Comparison of S-MES and Stratified Marginal Contribution Importance Sampling (S-MCIS)

In the previous subsection, we argued that there is no benefit of choosing the MES algorithm over the MCIS algorithm. In detail, we stated that sampling from the multilinear extension just mimics the true distribution, and thus, does not have any advantages.

Now, we consider the stratified case, i.e., S-MES from

Section 5.5, where the stratification is applied to the interval

. This stratification on the continuous interval

does not translate directly to the discrete space of coalitions. In S-MES, we first draw

for each stratum indexed by

. Then, from the perspective of a fixed player

, subsets are obtained by sampling i.i.d. according to

.

The discrete stratification scheme most consistent with the continuous scheme outlined above is stratifying by the size of coalitions excluding player i. Clearly, sampling from is always symmetric in a sense of coalitions of the same size having the same probability of being sampled, and therefore, we argue that a further, more fine-grained stratification in the discrete case would not be supported by S-MES. Conversely, it is also unclear how a less granular stratification could be justified by S-MES, since, clearly, each stratum implies distinct values , which imply unequal probabilities for different coalition sizes.

Thus, our proposed approximation named

S-MCIS is given by

where

is the number of marginal contributions where

i joins a coalition of size

. Hereby, for all

, the sample

is of size

and taken with uniform probability

.

From the definition above, one obtains that each stratum estimator

is the average marginal contribution of player

i to subsets of size

. Since this algorithm is meant to be the counterpart to S-MES and the stratified version of MCIS, we reuse evaluations of

v across players, similar to Algorithm 3 and 4. For simplicity, we aim for a proportional sample allocation (compare

Section 3.3) with respect to (

26), which is the case when all strata receive the same amount of samples

. Unfortunately, the values

from (

41) are estimators themselves and cannot be specified directly. Instead, we can only control the values

. Thus, to retrieve an approximate equal sample allocation across strata, we allocate the same amount of samples to each

, which is backed by the following proposition:

Proposition 7.

When for all and some constant , the expected sample sizes of all strata are equal, i.e.,

Proof. Let

be a random subset of size

s obtained via

. Then, for any

and

, we observe

Thus, whenever

for all

with

, we obtain

such that all

are equal. □

We refer the reader to Algorithm 5, which implements a ready-to-use implementation including the reuse of samples across players.

|

Algorithm 5:S-MCIS |

- 1:

- 2:

- 3:

fordo

- 4:

for times do

- 5:

Draw

- 6:

- 7:

for do

- 8:

if then

- 9:

- 10:

- 11:

else

- 12:

- 13:

- 14:

end if

- 15:

end for

- 16:

end for

- 17:

end for - 18:

- 19:

|

We note that S-MCIS is not the first stratified estimator for approximating Shapley values. In particular, we mention the

St-ApproShapley algorithm proposed by Castro et al. [

37], where stratification was applied based on the position of players in a random permutation. The idea is very similar to the stratification based on coalition sizes, since being in position

s in a permutation just means joining a coalition of size

. Additionally, we highlight the work of Maleki et al. [

38], where the authors proposed to stratify by coalition sizes similar to us. However, this manuscript does not aim to compare our S-MCIS algorithm to those and other stratified algorithms. Instead, we developed the S-MCIS algorithm solely for our analysis of sampling algorithms in the context of multilinear extensions.

It is worth noting that it is not guaranteed that holds for all strata, such that additional checks are required when implementing S-MCIS in the context of real-world applications. Our implementations do not include such checks. Instead, we rely on the following result:

Proposition 8.

Let τ denote the overall sample budget across all strata. Thus, we have as . Then, with probability approaching one asymptotically, each stratum estimator receives at least one sample, i.e.,

Proof. For

, the probability of a player

belonging to a random coalition of size

is given by

, while the probability of not belonging to a random coalition of size

is given by

. Thus, we have

Since

we can use the union bound [

39] and (

43) to derive

□

Now, let us analyze the properties of the S-MCIS estimator:

Proposition 9. The S-MCIS estimator is unbiased, i.e., .

Proof. Without loss of generality, we fix one player

. We denote by

the vector of all sampled coalitions of size

excluding player

i. Similarly, we define

as the vector of all sampled coalitions of size

that include player

i, with player

i subsequently removed.

Furthermore, the concatenation of those vectors is denoted by

with

being its length.

Thus, with

being the true average marginal contribution of player

i to all coalitions of size

, we get

Note that the equality between (

44) and (45) holds since the expressions inside the expectations in (

44) are sample means and the values

in (45) are population means. □

Proposition 10.

The variance of the S-MCIS estimator is approximately given by

as long as all are equal.

Proof. Let each

be an estimator of a linear solution concept

as defined by Theorem 1, i.e.,

such that, by using (

23), the variance of

is given by

Unfortunately,

itself is an estimator and not a fixed value. Therefore, we use its expectation given by (

42) with

in order to approximate (

48), which results in (

47).

□

In the following, we compare the variances of MCIS and S-MCIS.

Proposition 11.

By assuming that all are close enough to and all are equal, the variance of the S-MCIS estimator is always less or equal compared to the variance of the MCIS estimator, i.e.,

Proof. The proof is straightforward taking into account that S-MCIS constitutes a valid stratification of MCIS for each individual player in a sense of the definition provided in

Section 3.3. Additionally, by assuming that all

are close enough to

, we derive that S-MCIS uses a proportional sample allocation, since each subset size is equally likely in MCIS (compare (

26) and Proposition 6) and the expected sample size per stratum is equal over all strata in S-MCIS (see Proposition 7). Consequently, the variance reduction proof from

Section 3.3 holds, which completes the proof. □

Now, we compare the S-MES and S-MCIS estimator. From Propositions 4 and 9, we obtain that both algorithms are unbiased. Proposition 10 provides an approximated theoretical variance for the S-MCIS estimator, but we have not derived a theoretical variance for the S-MES algorithm. Therefore, in order to compare these algorithms and determine how to select among them, we state

Theorem 3.

By assuming that all are close enough to and all are equal, the variance of the S-MCIS estimator is always less or equal compared to the variance of the S-MES estimator, i.e.,

Proof. First, we note that the variance of MES and MCIS can be expressed similar to (

16), i.e.,

with

being defined in (

26).

Recall that stratification with proportional sample allocation removes the variance between stratum estimators, i.e., (50), such that the overall variance is just the expectation over all stratum estimators’ variances, i.e., (49). We refer to

Section 3.3 for more details.

As a result, the variance of the S-MCIS estimator is given by (49) only, since S-MCIS uses a proportional sample allocation. We refer to Propositions 7 and 11, which demonstrate that S-MCIS uses a proportional sample allocation scheme with respect to MCIS when assuming that all are close enough to .

In contrast, we argue that the same does not hold for S-MES. Since the stratification is performed over the continuous interval and coalitions are sampled in a second stage according to an i.i.d. Bernoulli distribution with parameter , any coalition size can theoretically occur in any stratum. Although this approach tends to reduce the variance — because coalition sizes follow a binomial distribution, assigning higher probabilities to subset sizes around , which could be interpreted as some sort of “weak stratification” — it does not completely eliminate the variance between stratum estimators, i.e., (50). Consequently, the non-negative term given by (50) may indeed be smaller than for its non-stratified variant MES, but unlike in the context of S-MCIS, this term does not vanish in general.

Thus, since both estimators’ variances additionally share the same term given by (49), one obtains that the overall variance of the S-MCIS estimator is always less or equal compared to the variance of the S-MES estimator. □

Our main finding in this and the previous subsection is that the indirections via multilinear extensions do not provide any benefit when seeing the characteristic function as a black box model and using Monte Carlo approximations. In detail, we found that one can easily derive the same estimator without the indirections caused by multilinear extensions (see Theorem 2) or derive an estimator with a variance that is less or equal in comparison to that of the respective multilinear-extension-based method, see Theorem 3. Furthermore, dropping the indirections via multilinear extensions allowed us to use the importance sampling framework from Theorem 1 to derive properties like the unbiasedness or variance of an obtained estimator, which in our view also speaks in favor of sampling directly on the coalition space.