Submitted:

06 January 2026

Posted:

07 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Data

2.1. Data Processing of Rayleigh Wave Tomography

2.2. Data Processing of Ambient Noise Tomography

3. Methods

3.1. Phase Velocity Inversion with Surface Wave

3.2. Phase Velocity Inversion with Ambient Noise

3.3. Inversion for Shear Velocity

4. Results

4.1. Resolution Tests

4.2. The 2-D Phase Velocity Results

4.3. The 3-D Shear Wave Velocity Results

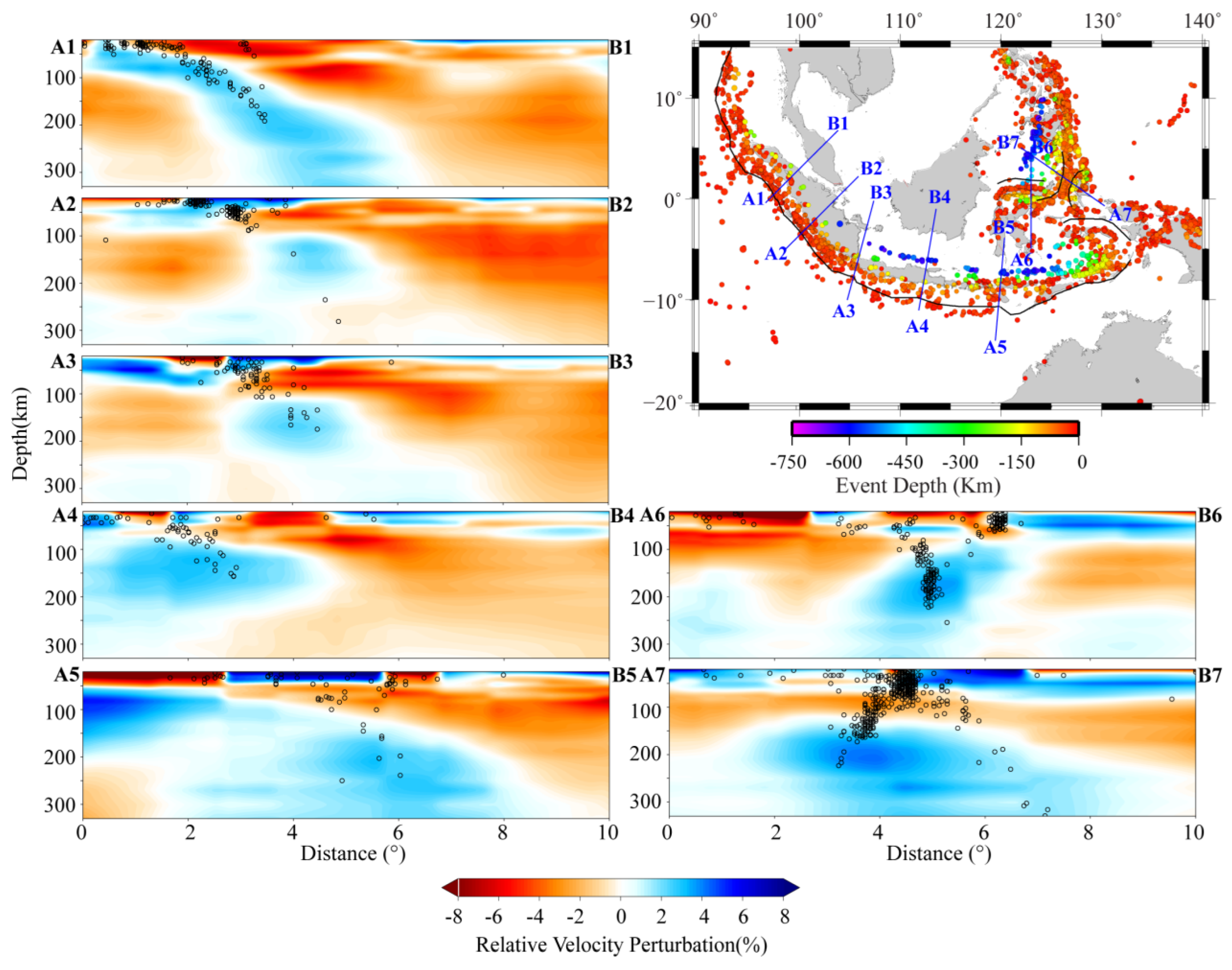

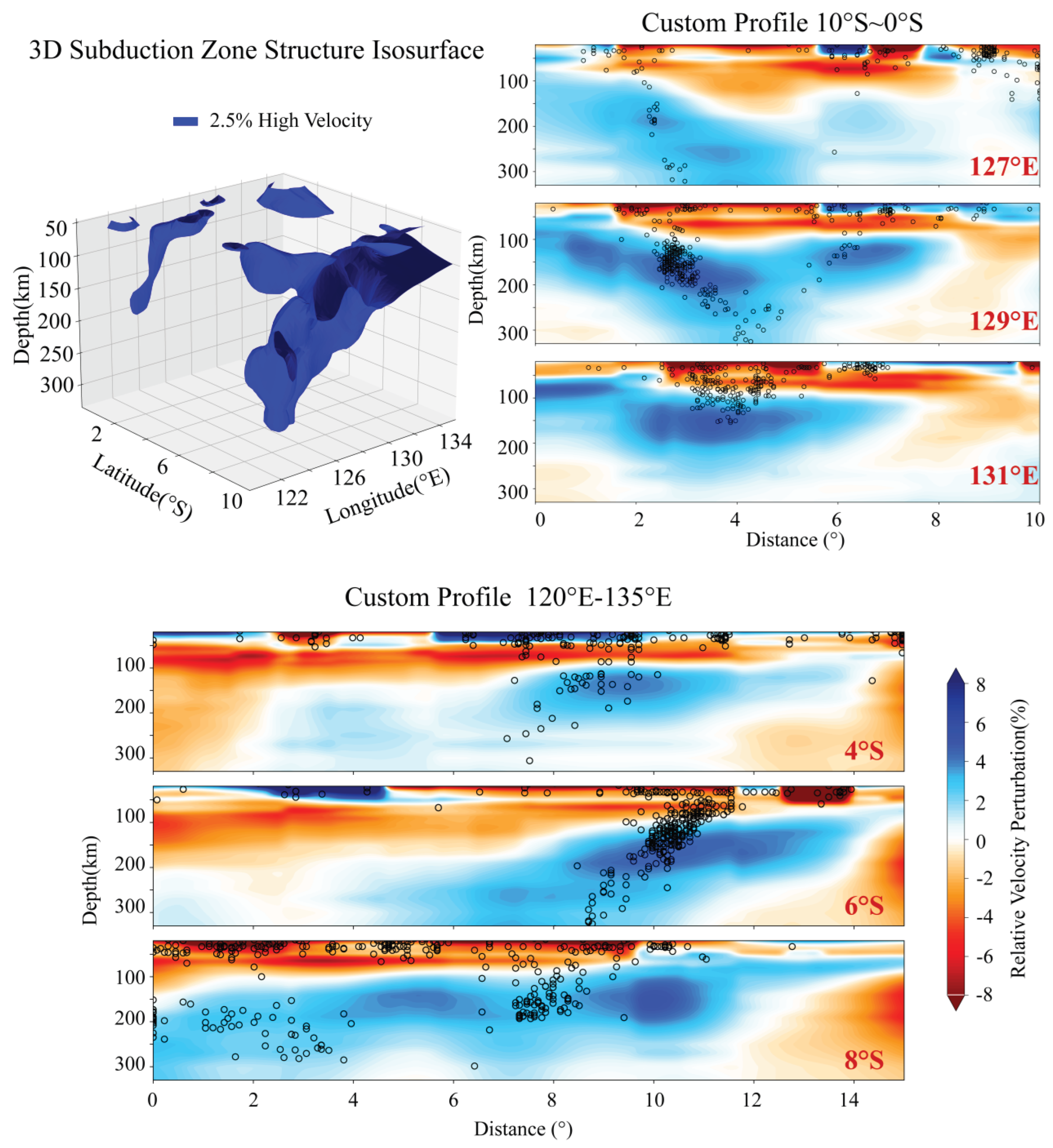

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparison with Previous Models

5.2. The Sunda-Java Trench

5.3. The Banda Arc

5.4. The Molucca Sea Arc-Arc Collision

6. Conclusions

References

- Amaru, M.L. Global travel time tomography with 3-D reference models. PhD thesis, Utrecht University, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sumatra: Geology, Resources and Tectonic Evolution. In Geol. Soc. London Mem.; Barber, A.J., Crow, M.J., Milsom, J.S., Eds.; 2005; Volume 31. [Google Scholar]

- Bensen, G.D.; Ritzwoller, M.H.; Barmin, M.; Levshin, A.L.; Lin, F.C.; Moschetti, M.P.; Shapiro, N.M.; Yang, Y. Processing seismic ambient noise data to obtain reliable broadband surface wave dispersion measurements. Geophys. J. Int. 2007, 169(3), 1239–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijwaard, H.; Spakman, W. Nonlinear global P-wave tomography by iterated linearized inversion. Geophys. J. Int. 2000, 141, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, P. An updated digital model of plate boundaries. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst 2003, 4(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, Y.; Prawirodirdjo, L.M.; Genrich, J.F.; Stevens, C.; McCaffrey, R.; Subarya, C.; Puntodewo, S.S.O.; Calais, E. Crustal motion in Indonesia from Global Positioning System measurements. J. Geophys. Res. 2003, 108, B8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowin, C.; Purdy, G.M.; Johnston, C.; Shor, G.; Lawver, L.; Hartono, H.M.S.; Jezek, P. Arc–continent collision in the Banda Sea region. AAPG Bull. 1980, 64, 868–915. [Google Scholar]

- Das, S. Seismicity gaps and the shape of the seismic zone in the Banda Sea region from relocated hypocenters. J. Geophys. Res. 2004, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Leo, J.F.; Wookey, J.; Hammond, J.O.S.; Kendall, J.-M.; Kaneshima, S.; Inoue, H.; Yamashina, T.; Harjadi, P. Mantle flow in regions of complex tectonics: Insights from Indonesia. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst 2012, 13, Q12008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djajadihardja, Y.S.; Taira, A.; Tokuyama, H.; Aoike, K.; Reichert, C.; Block, M.; Schluter, H.U.; Neben, S. Evolution of an accretionary complex along the north arm of the island of Sulawesi, Indonesia. Isl. Arc 2004, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, H.; Xu, Y.; Lebedev, S.; de Melo, B. C.; van der Hilst, R. D.; Wang, B.; Wang, W. The upper mantle beneath Asia from seismic tomography, with inferences for the mechanisms of tectonics, seismicity, and magmatism. Earth-Science Reviews 2024, 104841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichtner, A.; De Wit, M.J.; Van Bergen, M. Subduction of continental lithosphere in the Banda Sea region: Combining evidence from full waveform tomography and isotope ratios. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2010, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, D.W.; Webb, S.C.; Dorman, L.M.; Shen, Y. Phase velocities of Rayleigh waves in the MELT experiment on the East Pacific Rise. Science 1998, 280, 1235–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forsyth, D.W.; Li, A. Array analysis of two-dimensional variations in surface wave phase velocity and azimuthal anisotropy in the presence of multipathing interference. In Seismic Earth: Array Analysis of Broadband Seismograms; AGU Geophysical Monograph Series: Washington, DC, 2005; pp. 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield, T.; Gilligan, A.; Pilia, S.; Cornwell, D. G.; Tongkul, F.; Widiyantoro, S.; Rawlinson, N. Post-subduction tectonics of Sabah, northern Borneo, inferred from surface wave tomography. Geophysical Research Letters 2022, 49, e2021GL096117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R. Plate boundary evolution in the Halmahera region, Indonesia. Tectonophysics 1987, 144, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R.; Blundell, D.J. Tectonic evolution of SE Asia: Introduction. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 1996, 106(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R.; Wilson, M.E. Neogene sutures in eastern Indonesia. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2000, 18(6), 781–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R. Cenozoic geological and plate tectonic evolution of SE Asia and the SW Pacific: Computer-based reconstructions, models, and animations. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2001, 20, 351–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R. Cenozoic geological and plate tectonic evolution of SE Asia and the SW Pacific: computer-based reconstructions, model and animations. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2002, 20, 353–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R. The Eurasian SE Asian margin as a modern example of an accretionary orogen. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 2009, 318, 351–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R.; Spakman, W. Mantle structure and tectonic history of SE Asia. Tectonophysics 2015, 658, 14–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, W. Tectonics of the Indonesian region. U. S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1979, 1078, 345 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon, N.; Forsyth, D.W.; Weeraratne, D.S.; Yang, Y.; Webb, S.C. Mantle heterogeneity and off-axis volcanism on young Pacific lithosphere. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2011, 311, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinschberger, F.; Malod, J.; Rehault, J.; Villeneuve, M.; Royer, J.; Burhanuddin, S. Late Cenozoic geodynamic evolution of eastern Indonesia. Tectonophysics 2005, 91–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y.; Zhao, D.; Xu, Y.-G. P and S wave anisotropic tomography of the Banda subduction zone. Geophysical Research Letters 2023, 50, e2023GL105611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, L. A.; Hilton, D. R.; Fischer, T. P.; Hartono, U. Tracing magma sources in an arc-arc collision zone: Helium and carbon isotope and relative abundance systematics of the Sangihe Arc, Indonesia. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst 2004, 5, Q04J10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennett, B.L.N.; Engdahl, E.R. Travel times for global earthquake location and phase association. Geophys. J. Int. 1991, 105, 429–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, B.; Gahalaut, V.K. Slab detachment of subducted Indo-Australian plate beneath Sunda arc, Indonesia. Journal of Earth System Science 2011, 120(2), 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laske, G.; Masters, G.; Ma, Z.; Pasyanos, M. Update on CRUST1.0—a 1-degree Global Model of Earth’s crust. Geophys. Res. Abstr. 2013, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Le, B.M.; Yang, T.; Morgan, J.P. Seismic Constraints on Crustal and Uppermost Mantle Structure Beneath the Hawaiian Swell: Implications for Plume-Lithosphere Interactions. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2022, 127, e2021JB023822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, C.P.; Zhao, L.; Chen, Q.-F. Upper-mantle shear-wave structure under East and Southeast Asia from Automated Multimode Inversion of waveforms. Geophys. J. Int. 2015, 203, 707–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levshin, A.L.; Yanocskaya, T.B.; Lander, A.V.; Bukchin, B.G.; Barmin, M.P.; Ratnikova, L.I.; Its, E.N. Seismic surface waves in a laterally inhomogeneous Earth; Keilis-Borok, V.I., Ed.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, 1989; pp. 153–163. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, C.; Langston, C.A. Ambient seismic noise tomography and structure of eastern North America. J. Geophys. Res. 2008, 113, B03309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.C.; Ritzwoller, M.H.; Townend, J.; Bannister, S.; Savage, M.K. Ambient noise Rayleigh wave tomography of New Zealand. Geophysical Journal International 2007, 170(2), 649–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobkis, O.I.; Weaver, R.L. On the emergence of the Green’s function in the correlations of a diffusive field. J. acoust. Soc. Am. 2001, 110, 3011–3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaffery, R.; Silver, E.A. Crustal Structure of the Molucca Sea Collision Zone, Indonesia. The Tectonic and Geologic Evolution of Southeast Asian Seas and Islands—Geophysical Monograph 1980, 23. [Google Scholar]

- McCaffrey, R. Earthquakes and ophiolite emplacement in the Molucca Sea Collision Zone, Indonesia. Tectonics 1991, 10(2), 433–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.S.; O’Driscoll, L.J.; Roosmawati, N.; Harris, C.W.; Porritt, R.W.; West, A.J. Banda Arc Experiment—Transitions in the Banda Arc-Australian Continental Collision. Seismological Research Letters 2016, 87(6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, C.; Barckhausen, U.; Ehrhardt, A.; Engels, M.; Gaedicke, C.; Keppler, H.; Flueh, E.R.; Djajadihardja, Y.S.; Soemantri, D.; Seeber, L. From Subduction to Collision: The Sunda-Banda Arc Transition. Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union 2008, 89(6), 49–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagao, T.; Uyeda, S. Heat-flow distribution in Southeast Asia with consideration of volcanic heat. Tectonophysics 1995, 251, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.; Yang, T.; Le, B.M.; Dai, Y.; Xiao, H. The Magmatic Patterns Formed by the Interaction of the Hainan Mantle Plume and Lei–Qiong Crust Revealed through Seismic Ambient Noise Imaging. Geosciences 2024, 14, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planert, L.; Kopp, H.; Lueschen, E.; Mueller, C.; Flueh, E. R.; Shulgin, A.; Djajadihardja, Y.S.; Krabbenhoeft, A. Lower plate structure and upper plate deformational segmentation at the Sunda-Banda arc transition, Indonesia. Journal of Geophysical Research 2010, 115, B8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Press, W.H.; Teukolsky, S.A.; Vetterling, W.T.; Flannery, B.P. Numerical Recipes in FORTAN: The Art of Scientific Computing, 2nd edn; Cambridge Univ. Press, 1992; p. 963. [Google Scholar]

- Pubellier, M.; Monnier, C.; Maury, R.C.; Tamayo, R.A. Plate kinematics, origin and tectonic emplacement of supra-subduction ophiolites in SE Asia. Tectonophysics 2004, 9–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Replumaz, A.; Tapponnier, P. Reconstruction of the deformed collision zone Between India and Asia by backward motion of lithospheric blocks. Journal of Geophysical Research 2003, 108(B6), 2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, M. DISPER80: a subroutine package for the calculation of seismic normal mode solutions. In Seismological Algorithms: Computational Methods and Computer Programs; Doornbos, D.J., Ed.; Elsevier, 1988; pp. 293–319. [Google Scholar]

- Sdrolias, M.; Müller, R.D. Controls on back-arc basin formation. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst 2006, 7, Q04016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieh, K.; Natawidjaja, D. H. Neotectonics of the Sumatran fault, Indonesia. Journal of Geophysical Research 2000, 28295–28326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, E.A.; Moore, J.C. The Molucca Sea Collision Zone, Indonesia. Journal of Geophysical Research 1978, 1681–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarantola, A.; Valette, B. Generalized nonlinear inverse problems solved using the least squares criterion. Rev. geophys. Space Phys. 1982, 20(2), 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyokuni, G.; Zhao, D.; Kurata, K. Whole-mantle tomography of Southeast Asia: New insight into plumes and slabs. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 2022, 127, e2022JB024298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, R.L.; Lobkis, O.I. Diffuse fields in open systems and the emergence of the Green’s function. J. acoust. Soc. Am. 2004, 116, 2731–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widiyantoro, S.; Pesicek, J.D.; Thurber, C.H. Subducting slab structure below the eastern Sunda arc inferred from non-linear seismic tomographic imaging; Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 2011; Volume v.355, pp. 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Liu, F.; Harmon, N.; Phon Le, K.; Gu, S.; Xue, M. Lithospheric structure beneath Indochina block from Rayleigh wave phase velocity tomography. Geophys. J. Int. 2015, 200, 1582–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Xu, G.; Zhu, L.; Xiao, X. Mantle structure from inter-station Rayleigh wave dispersion and its tectonic implication in western China and neighboring regions. Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors 2005, 148(1), 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; van der Hilst, R.D.; de Hoop, M.V. Surface-wave array tomography in SE Tibet from ambient seismic noise and two-station analysis: I - Phase velocity maps. Geophysical Journal International 2006, 732–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenonos, A.; De Siena, L.; Widiyantoro, S.; et al. P and S wave travel time tomography of the SE Asia-Australia collision zone. Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors 2019, 293, 106267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).