Introduction

The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) and automation technologies is reshaping the nature of work across the globe. While much attention has focused on developed economies, there is a pressing need to understand how these trends play out in emerging markets, particularly in Africa. Many African and developing countries face unique labor market structures – with a high prevalence of low-wage, informal, and routine jobs – that may be especially vulnerable to automation. At the same time, opportunities exist for AI to augment human labor, potentially boosting productivity in nascent tech and service sectors. This paper provides a data-guided analysis of job evolution under the influence of AI-driven task transformation, emphasizing the empirical relationships between automation risk, skill levels, wages, and job outcomes in emerging markets. The goal is to ground the often-abstract debate on “the future of work” in evidence, using both a quantitative regression framework and newly available data on AI task usage, and then to draw out concrete policy implications.

We anchor our analysis on a regression model that examines how automation probability, job growth forecast, and job zone (skill level) predict the median salary of occupations. This model, based on detailed occupation-level data, provides a quantitative lens to interpret how tasks and jobs are evolving. In parallel, we draw on recent empirical findings from the “Anthropic Economic Index” – a large-scale analysis of millions of AI (Claude) conversations mapped to job tasks. This novel dataset offers granular evidence of which tasks AI is currently used for, whether AI tends to augment or automate those tasks, and how AI usage varies by task type, skill, and wage level. By combining insights from the regression results and the AI task usage data, we analyze how job evolution is unfolding in Africa and similar emerging markets. In particular, we highlight patterns such as the negative correlation between low wages and high automation risk, the predominantly skill-biased nature of AI augmentation (favoring cognitive tasks and higher-educated workers), and the uneven sectoral exposure to these trends (e.g. manufacturing vs. services vs. agriculture).

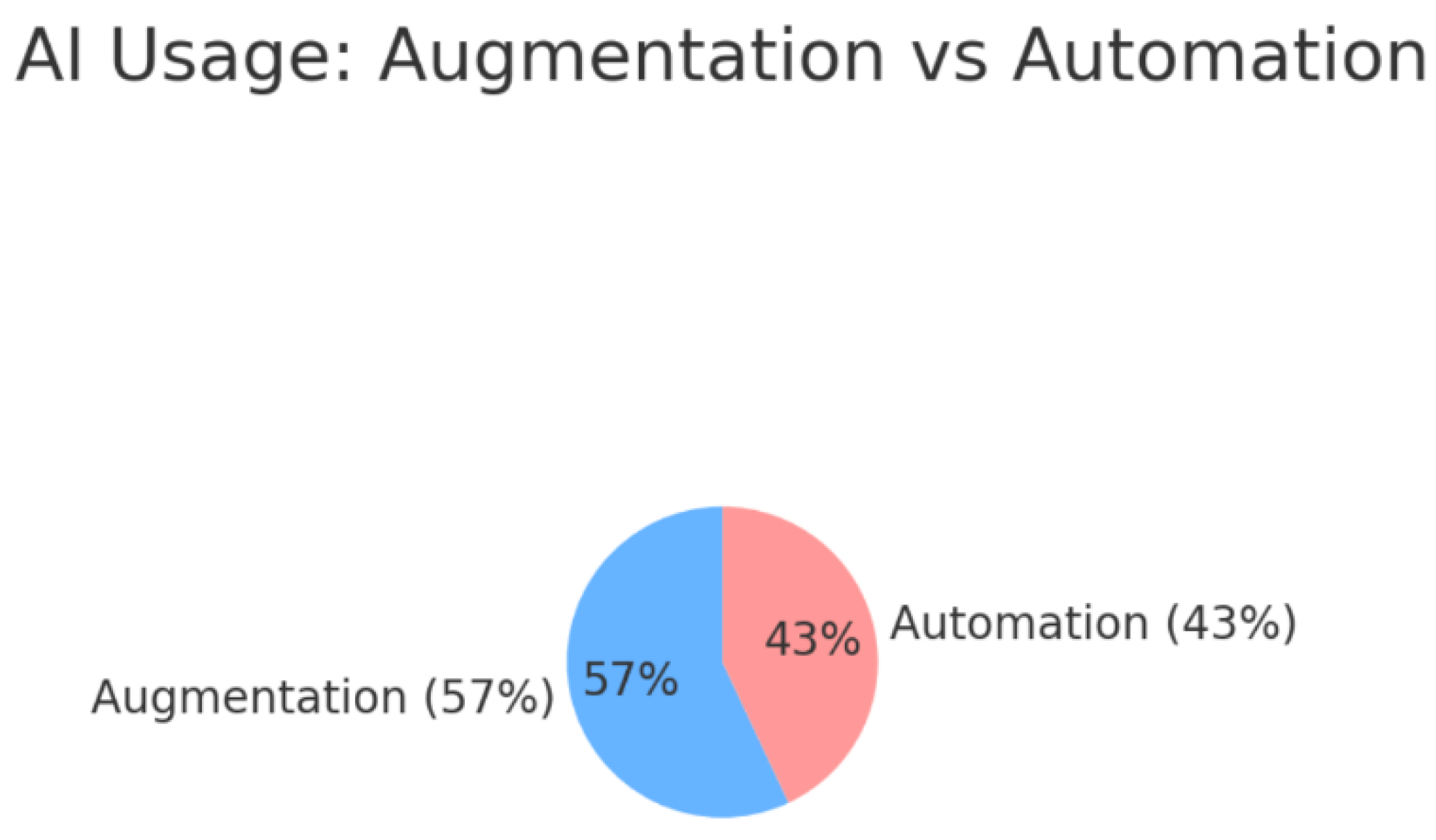

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. The Literature Review surveys existing research on automation’s impact on jobs, the distinction between automation and augmentation of tasks, and what is known about these dynamics in developing economies. The Methodology section describes the data sources and analytical approach, including the construction of the regression model and the task-mapping from AI usage data. Next, the Findings section presents the empirical results: the regression outcomes with coefficients and significance, and key patterns from the Anthropic task data (such as the concentration of AI usage in software and writing tasks, the 57 percent vs 43 percent split between augmentation and automation, and differences across skill and wage levels). In the Discussion, we interpret these findings in the context of Africa and emerging markets – examining implications for workforce inequality, job transitions, and sectoral development. We also propose evidence-driven policy responses, including targeted education and reskilling initiatives, sector-specific strategies, and industrial policies that align with the observed task transformation trends. Finally, the Conclusion summarizes the insights and underscores the importance of proactive, data-informed policies to navigate the evolving landscape of work in emerging economies.

Literature Review

The impact of automation and AI on employment has been a subject of extensive research, yielding insights into which jobs are most susceptible and how technology may transform tasks rather than entire occupations. Early influential work by Frey and Osborne (2017) introduced the concept of automation probability for occupations, estimating that 47 percent of U.S. jobs had a high risk of computerization. A key finding from their study was that occupations with lower wages and educational requirements tend to have higher automation probabilities, whereas high-skill, high-wage occupations are relatively less susceptible. This negative relationship between wages (and education) and automation risk underscores a potential driver of inequality: if low-wage jobs are more easily automated, workers in developing countries who often occupy such jobs could be disproportionately affected.

Subsequent research has refined our understanding by focusing on the task content of jobs. Autor (2013, 2015) and others developed the task-based framework, distinguishing between routine tasks that machines can easily perform and non-routine cognitive or manual tasks that are harder to automate. These works emphasize that technology’s impact is often skill-biased: computers excel at routine, rules-based tasks (including many middle-skill clerical or production tasks) while complementing or augmenting higher-skill analytical and creative tasks. This phenomenon, known as skill-biased technical change, has been observed in industrialized economies and is relevant to emerging markets as they integrate similar technologies. In African contexts, where a large share of employment is in agriculture or informal services, the task composition differs from advanced economies. Nevertheless, studies have raised concerns of “premature deindustrialization” – the idea that developing countries might industrialize less or lose manufacturing jobs earlier due to automation reducing the demand for low-skilled labor in global value chains (Rodrik, 2016). Empirical evidence on automation in low- and middle-income countries is still limited, but recent analyses (Comunale & Manera, 2024; Gmyrek et al., 2024) note that the discourse is only beginning to address how AI will affect these economies.

A parallel strand of literature examines AI as an augmenting technology. Brynjolfsson and Mitchell (2017) argue for a paradigm of “augmentation” where AI tools work alongside humans, increasing productivity without fully replacing workers. Indeed, controlled experiments have shown productivity gains when AI is used to assist workers in writing, coding, and other tasks (e.g., Noy & Zhang, 2023; Peng et al., 2023). In these cases, AI plays a complementary role, allowing workers to focus on higher-level functions. The distinction between AI-driven automation vs. augmentation is critical: when AI automates a task, it substitutes for human labor; when it augments, it enhances human capability. Autor (2015) highlighted that augmentation can lead to “automation complementarities”, where productivity and even labor demand in certain tasks increase because AI boosts output quality or speed. For example, an AI system might handle routine drafting of reports (automation) while enabling a human analyst to more quickly interpret results and make decisions (augmentation). The net effect on jobs depends on the balance of these forces.

Recent empirical work by Handa et al. (2024) – dubbed the Anthropic Economic Index – provides one of the first large-scale glimpses into how AI is actually being used across different tasks in the economy. By analyzing millions of anonym zed chat conversations with an AI assistant (Claude) and mapping them to occupational tasks, this study offers concrete evidence to inform the theoretical debates. They find that AI usage is concentrated in specific types of tasks, notably software development (coding) and writing-related tasks, which together account for nearly half of all AI usage observed. At the same time, AI usage is widespread: about 36 percent of occupations were found to use AI for at least a quarter of the tasks associated with those jobs. This suggests that AI’s reach extends beyond just tech jobs and is permeating a broad range of roles, though the intensity varies. Crucially, Handa et al. distinguish between augmentative vs. automative usage of AI. Approximately 57 percent of AI usage appears to be augmenting human work, whereas 43 percent is automating tasks. In other words, in the majority of cases AI is being used as a tool to help humans iterate, learn, or improve outcomes (augmentation), but in a significant minority of cases it is used to fully carry out tasks with minimal human input (automation). This empirically backs the notion that both dynamics are at play in real workplaces.

The Anthropic study also sheds light on the types of skills being replicated by AI. Not surprisingly, cognitive and communication skills dominate AI’s current repertoire, while tasks requiring physical or manual skills are very rare in AI usage data. For instance, skills such as critical thinking, programming, writing, and reading comprehension were among the most commonly exhibited in the AI’s outputs, whereas skills like equipment maintenance, installation, and manual repair hardly appeared. This reflects the current technological frontier: today’s AI (especially large language models like Claude or GPT) are adept at information processing and generation, but they do not perform physical manipulation tasks. As a result, occupations that rely on physical interaction (e.g. electricians, mechanics, and caregivers) have seen little direct AI integration so far, whereas occupations centered on information processing (e.g. software developers, writers, analysts) are already leveraging AI. This cognitive vs. physical skill disparity in AI interaction is an important nuance for emerging markets – economies with a larger share of employment in manual occupations might initially be less directly touched by AI automation, but they also might benefit less from augmentation in the short run.

Finally, the literature on AI, wages, and inequality indicates that if AI disproportionately augments high-skill jobs and automates low-skill jobs, it could exacerbate income inequality. Acemoglu (2021) and others caution that without intervention, AI could follow the pattern of previous technologies that increased the premium for skilled workers while reducing opportunities for less-skilled workers. Early indicators from the Anthropic data support this concern: AI usage tends to be highest in mid-to-high wage occupations (especially those requiring considerable preparation like a bachelor’s degree) and lower in both very low-wage jobs and the extremely high end of the wage spectrum. In their analysis, occupations in the upper-middle wage quartile (e.g. software developers, technical professionals) show the greatest adoption of AI tools, whereas the lowest wage jobs (e.g. waiters) and certain ultra-high wage jobs (e.g. specialized physicians like anesthesiologists) have low AI usage. The low usage at the very high end is attributed to the nature of those jobs involving highly specialized expert tasks or physical procedures that current AI cannot easily perform. This pattern suggests a U-shaped or polarized impact: AI may most benefit those with a solid base of education and technical skills, while offering less to those at the bottom or top extremes, potentially widening the gap between medium/high-skill workers and the rest. These findings align with classic theories of technological polarization of the labor market (Autor & Dorn, 2013), but now unfolding in the context of AI-driven tasks.

In summary, the literature provides a framework for understanding how automation and AI might transform jobs: low-skill routine work is at high risk of automation, high-skill work can be augmented (and sometimes partially automated) by AI, and the net effect on employment and inequality will depend on how societies respond. What remains under-explored is how these dynamics play out in emerging markets. This paper aims to fill that gap by leveraging new data and analysis to quantify and interpret the evolution of jobs in Africa and similar contexts, thereby contributing to the global discourse with evidence-based insights relevant for policymakers in the developing world.

Methodology

Our analysis employs a mixed-methods approach, combining quantitative regression modeling with task-level AI usage data analysis to explore the relationship between automation, skills, and job outcomes. In this section, we outline the data sources and definitions of key variables, describe the regression model specification, and explain how we integrate the anthropic task data to inform our interpretation.

Data Sources and Key Variables: The core dataset for the regression comes from merging several sources at the occupation level (using the U.S. Standard Occupational Classification, SOC, as a basis, which we later map to emerging market contexts):

Automation Probability (“Chance of Automation”): We utilize an occupation-specific automation risk metric. This metric represents the estimated probability that the tasks of an occupation can be automated by existing or near-future technologies. It is drawn from prior studies that assessed occupations for computerization or AI susceptibility (in line with Frey & Osborne’s methodology). Each occupation is assigned a percentage (0–100%) indicating its automation risk. For example, jobs like data entry clerks might have a high automation probability, whereas teachers might have a lower probability. In our regression dataset this is denoted as Chance Auto.

Job Growth Forecast (“Job Forecast”): This variable captures the projected employment change for the occupation over a future period (e.g., the next decade). We obtained forecast data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) employment projections (for 2020–2030) and analogous sources. It is typically expressed as a percentage growth (or decline) or an absolute change in number of jobs. For consistency, we use a percentage growth forecast: positive values if an occupation is expected to grow (add jobs), negative if it’s expected to shrink. This provides insight into how labor demand is evolving for that role, independent of automation. “Job Forecast” in our model is a numerical variable (for instance, +15% for software developers, or –10% for file clerks).

Job Zone (Skill Level): Job Zone is an occupational classification from the U.S. Department of Labor’s O*NET system that indicates the level of preparation (education, training, experience) needed for an occupation. It ranges from 1 (little or no preparation, e.g. low-skill service jobs) up to 5 (extensive preparation, e.g. advanced degree professions). We include JobZone as an ordinal variable (1 through 5) to proxy the skill/education level required for each occupation. This is particularly relevant for comparing across emerging markets, since Job Zone essentially encodes skill level in a way that is comparable internationally (e.g., Zone 1 jobs often correspond to elementary occupations, Zone 4 to professional occupations requiring a bachelor’s degree, etc.).

Median Salary: The dependent variable in our regression is the median annual salary (or wage) for the occupation. For the U.S. data, this was sourced from O*NET and BLS wage statistics (e.g., median annual wage as of 2022, in USD). We use median salary as a summary measure of job “quality” and economic value. In emerging market discussion, relative salary levels often differ, but the relationships with automation risk and skill can be interpreted in a similar way (i.e., low-wage jobs in a country are often those with lower skill and potentially higher automation risk). We log-transform salary in some analyses for normalization, but in the main regression we use absolute values (given a restricted range of occupational medians in the data).

AI Task Usage Metrics: In addition to the regression variables, we incorporate findings from the Anthropic AI task usage dataset qualitatively and for additional context. Key metrics derived from that data (not directly in the regression but used in analysis) include: the proportion of tasks within an occupation that have evidence of AI usage, the classification of those tasks into augmentative vs. automotive usage, and counts of AI interactions by task type. These metrics were computed by Handa et al. (2024) using a mapping of AI conversation data to O*NET task statements. For example, if an occupation has 20 defined tasks and AI was used for 5 of them in the dataset, that occupation would have 25 percent of tasks with AI usage; if 3 of those were augmentative and 2 automotive, we could say 60 percent of that occupation’s AI-using tasks were augmentation, 40 percent automation. We leverage such information to interpret whether an occupation is more likely to see AI as a complement or a substitute.

Regression Model Specification: We estimate an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression where the dependent variable is the occupation’s median salary. The primary independent variables are: Chance of Automation, Job Growth Forecast, and Job Zone. Formally, the model can be written as:

Log-Linear Regression Equation:

Where αi is the categorical effects of job types

Log (job forecast) - 0.043% decrease in salary, holding other factors constant. Suggests lower pay in fast-growing jobs (likely lower-skill roles).

Chance auto - Higher automation risk slightly reduces wages (-0.0014) and p value is 0.015

Job zone - More skilled/prepared jobs earn higher salaries (+0.1432) and p <0.001

Is bright – Not significant ( -0.02) , p value 0.675

Is green – positive correlation (+0.0884), p value 0.106

We estimate a log-linear model of median salary as a function of job growth forecasts, automation risk, job preparation requirements, and occupational characteristics. The results indicate that occupations with higher forecasted growth or automation probability are associated with slightly lower wages, while those requiring more preparation (higher JobZone values) earn more. Several job families—particularly in personal care, arts and food preparation—are associated with significantly lower wage levels compared to the base group, while management occupations stand out as having higher median salaries. The model explains approximately 33% of the variance in wages, highlighting the influence of structural job characteristics on earnings.

Where i indexes occupations. We include all occupations for which data on these variables are available; the sample size is N ≈ 1,090 occupations (covering a broad range from manual labor to professional roles). The regression provides coefficient estimates which capture the marginal effect of each predictor on median salary, holding the others constant. Notably, this is a cross-sectional regression intended to reveal correlations and associations rather than causal effects. However, it offers useful insight into how certain characteristics (automation risk, skill level, etc.) relate to the economic value of jobs.

We pay special attention to the statistical significance (p-values) of the coefficients to identify which relationships are robust. The model’s overall fit is assessed by R-squared. While we do not include additional control variables in the core model to keep it parsimonious, we acknowledge that factors like industry, unionization, or geographic location can also affect salaries. For our purposes, the model serves as a simplified representation of how technology-related factors align with wages.

Task Data Analysis: Alongside the regression, we perform a descriptive analysis of the AI task usage data from the Anthropic Economic Index study. This involves reviewing the distribution of AI usage across tasks, occupations, wage levels, and job zones. We replicate or summarize key figures from that study to contextualize our regression findings. For instance, we examine the distribution of occupations by their AI usage intensity (what fraction of their tasks involve AI) and how that intersects with wage quartiles and job zones. We also look at examples of tasks that are automated vs augmented by AI to illustrate what kinds of work are being substituted versus complemented.

The data files referenced for this purpose include: O*NET task mappings (which link each occupation to its tasks), automation vs. augmentation classifications (which categorize AI interactions into types like “directive” or “feedback loop”, grouped as automation or augmentation and wage data for each occupation (to tie into the regression). These were provided in the project and supplemented by external sources (e.g., a GitHub repository for O*NET data visualization). We ensured that all data align by occupational codes so that the insights from the AI usage dataset can be matched to the corresponding occupation in our regression.

Application to Markets: Although our quantitative model is built on data largely collected in a U.S. context (due to the richness of O*NET and BLS data), we interpret the results with an eye toward Africa and emerging markets. The assumption underlying this application is that the relationships between skill, automation, and wages are qualitatively similar across many labor markets, even if absolute levels differ. For example, a Job Zone 1 occupation in the U.S. (like a food service worker) might have a different wage than a similar job in Nigeria, but in both cases it’s a low-skill, low-wage job likely susceptible to automation (like with self-service kiosks). We also incorporate any available developing-country data points in discussion. The analysis is thus anchored in a global perspective – using robust data from one context to shed light on another, while being mindful of contextual differences (like informality, technology adoption lags, etc., which we discuss qualitatively).

By combining these methods – a regression model for structured insight and a task-level data analysis for granular evidence – our approach provides both a macro-level and micro-level view of job evolution. The regression tells us, for instance, how strongly automation risk correlates with lower salaries (a proxy for vulnerability of lower-income workers), and the task data tells us what exactly those high-risk, low-wage jobs are doing and how AI might perform those tasks. This comprehensive approach sets the stage for evidence-based discussion on the implications for Africa and emerging markets.

Findings

In this section, we present the empirical findings from our regression analysis and the AI task usage data, and then synthesize these results to draw a picture of how jobs are evolving. We first report the results of the regression model, including the estimated coefficients for automation probability, job forecast, and job zone, along with their significance. We then delve into insights from the task-level AI usage data, highlighting which tasks and occupations are most impacted by AI (through augmentation or automation) and how these patterns correlate with wages and skills. Finally, we discuss how these findings relate to one another, illuminating key trends such as the high automation risk of low-wage jobs and the concentration of AI’s benefits in higher-skill work.

Regression Results: Automation Probability, Job Forecast, and Skill Level as Predictors of Salary

The regression model offers a clear quantitative confirmation of several intuitive relationships between technology-related factors and job wages.

Table 1 below summarizes the regression output, showing the estimated coefficients for each predictor and their statistical significance.

Table 1.

OLS Regression of median salary on the automation probability, job forecast and job zone (N=1090).

Table 1.

OLS Regression of median salary on the automation probability, job forecast and job zone (N=1090).

| Predictor |

Coefficient |

Std. Error |

t-statistic |

p-value |

| Intercept(baseline) |

31,830 |

2641 |

12.05 |

< 2.0e-16***

|

| Chance of Automation |

-176.0 |

23.0 |

-7.65 |

4.32e-14***

|

| Job Growth forecast |

-0.0405 |

0.0130 |

-3.12 |

0.00186** |

| Job zone |

11,850 |

699.8 |

16.93 |

< 2.0e-16***

|

Table 2.

Correlation matrix.

Table 2.

Correlation matrix.

| |

Median Salary |

Job Forecast |

Chance Auto |

Job Zone |

| Median Salary |

1.0000 |

-0.13723043 |

-0.40973438 |

0.5562669 |

| Job Forecast |

-0.137230 |

1.0000 |

0.06940796 |

-0.10044781 |

| Chance Auto |

-0.4097344 |

0.06940796 |

1.0000 |

-0.42906128 |

| Job Zone |

0.5562669 |

-0.10044781 |

-0.42906128 |

1.0000000 |

Several important findings emerge from this regression:

Negative Relationship between Automation Probability and Salary: The coefficient on Chance of Automation is -176.0 (with p < 0.001), indicating a strong and statistically significant negative association with median salary. In practical terms, this suggests that for each 1 percentage-point increase in an occupation’s estimated automation probability, the median annual salary for that occupation is about

$176 lower on average, holding other factors constant. This is a substantial effect: for example, an occupation that is 30 percent more automatable than another might pay on the order of

$5,000 less per year, all else equal. This finding quantitatively supports the notion that jobs that are easier to automate tend to be lower-paying. It aligns with prior evidence that low-skill, routine jobs (which often pay less) are more susceptible to being taken over by machines. In the context of emerging markets, where many workers are in low-paying jobs, this is a cause for concern – it implies a concentration of automation risk on the most economically vulnerable workers.

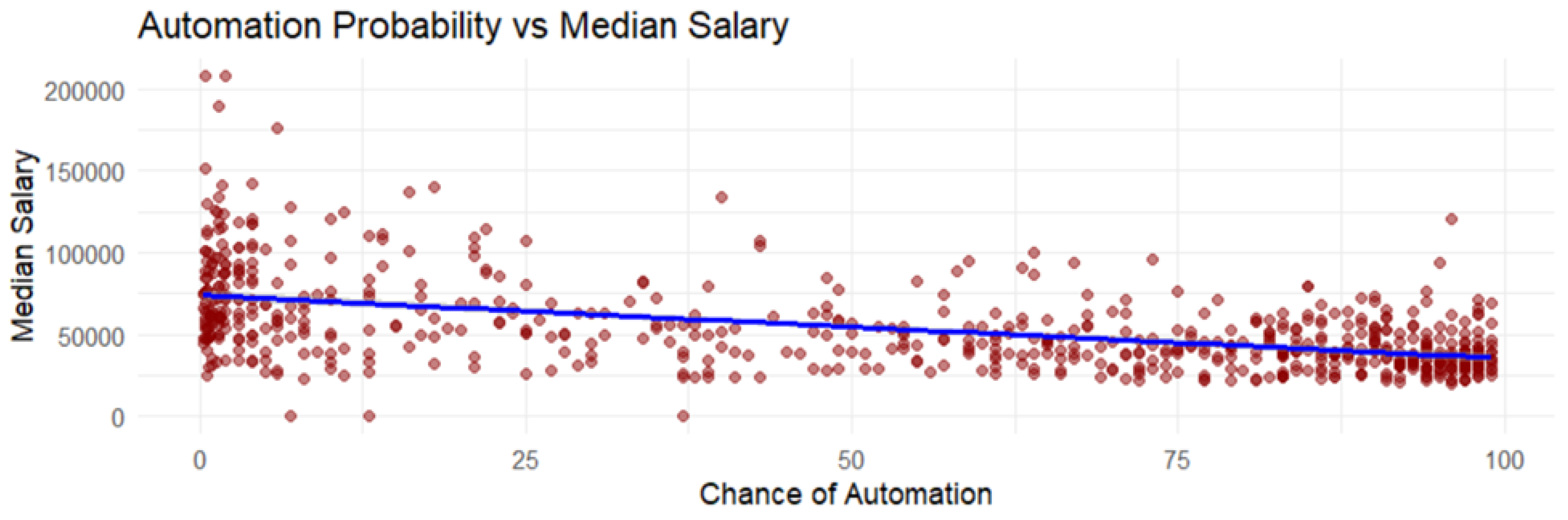

Figure 1.

Relationship between Automation Probability and Salary.

Figure 1.

Relationship between Automation Probability and Salary.

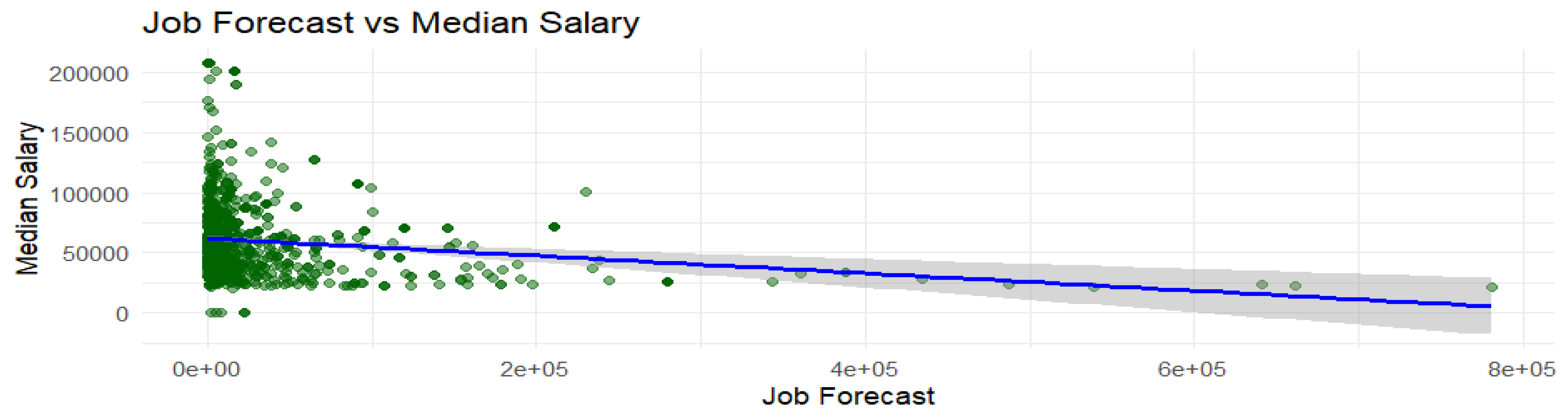

Job Growth Forecast is a Negative Predictor of Salary: Interestingly, Job Forecast has a small negative coefficient (-0.0405) that is statistically significant (p ≈ 0.002). This suggests that occupations with higher projected growth rates tend to have slightly lower current median salaries (a 1 percent higher growth is associated with about

$0.04 lower salary, though the effect is very small). While this coefficient is an order of magnitude smaller than the others, its significance implies a consistent pattern. One possible interpretation is that some lower-paid occupations (e.g., home health aides, care workers) are projected to grow rapidly due to demand, whereas some very high-paid occupations (e.g., certain specialized professionals) may be growing slower or even declining. In other words, rapid job growth in the economy might currently be coming in somewhat lower-wage fields (like personal care, some service sectors) – a trend that has been noted in labor reports. However, this relationship is relatively weak (nearly flat), so we treat it cautiously. It may reflect cyclical or sector-specific trends rather than any technological effect. For our purposes, the key takeaway is that the growth outlook of a job is not strongly positively correlated with current wages – high growth jobs aren’t necessarily high-paying jobs. This could imply that even if some low-wage jobs are expanding in number, their low wage and high automat ability could still pose a problem for worker livelihoods.

Figure 2.

Job Growth Forecast vs. Median Salary.

Figure 2.

Job Growth Forecast vs. Median Salary.

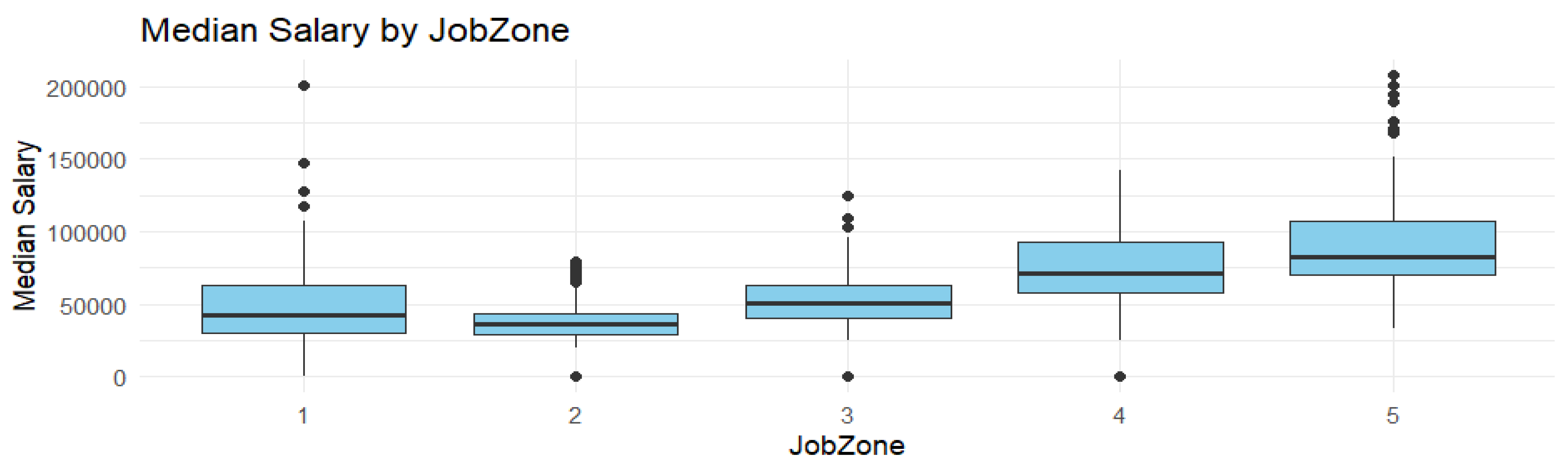

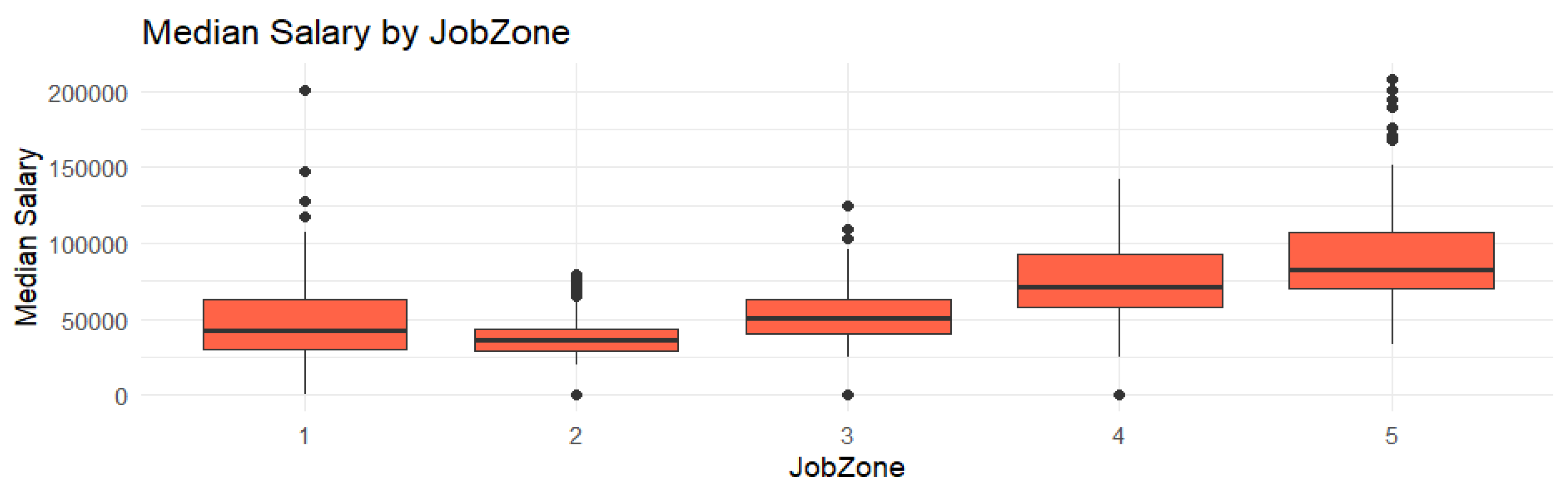

Skill Level (Job Zone) is a Strong Positive Predictor of Salary: The coefficient on Job Zone is +11,850, highly significant (p < 0.001). This means that each increase in the job zone (roughly equivalent to a higher level of required education/skill) is associated with an

$11.85k increase in annual median salary on average. For example, moving from a Job Zone 2 (some preparation, high school level) to Job Zone 3 (medium preparation, maybe associate’s degree or vocational training) might correspond to roughly

$12k higher median pay; moving from Zone 3 to Zone 4 (considerable prep, bachelor’s level) another

$12k, etc. This finding is unsurprising – it reflects the well-established returns to skill and education. What’s important here is that it quantifies the wage premium of higher-skilled jobs in our dataset, reinforcing why workers (and policymakers) place emphasis on up skilling. Moreover, because Job Zone is inversely related to automation risk (higher-zone jobs tend to have lower automation probabilities), this coefficient also indirectly captures the protective effect of education: higher-zone (more educated) occupations both pay more and are less likely to be automated. This is a crucial point for emerging markets, as it highlights skill development as a pathway to better-paid and more automation-resilient jobs.

Figure 3.

Median salary Vs. Job zone.

Figure 3.

Median salary Vs. Job zone.

Model Fit: The R-squared of ~0.35 indicates that about 35 percent of the variance in median salaries across occupations is explained by these three predictors. In social science terms, this is a moderate explanatory power for a simple model. It suggests that while automation risk, growth outlook, and skill level are important, there remain other factors influencing wages (such as industry profitability, union presence, etc.). Nonetheless, from a policy perspective, these results are quite telling: two of the three factors we tested – automation probability and skill level – have strong associations with wages. Essentially, low-skill, high-automation-risk jobs are systematically lower-paid, whereas high-skill, low-automation-risk jobs are higher-paid. This pattern likely reflects underlying economic forces (high-skill labor is scarce and valuable, routine labor is abundant and replaceable), and it foreshadows challenges if automation technology becomes more widespread.

To visualize one of the key bivariate relationships underlying these results, consider

Figure 1 below, which plots occupations by their automation probability (x-axis) and median salary (y-axis). A trend line is fitted to show the general direction of the relationship.

To sum up, the above findings are summarized in a regression equation (2) below:

In

Figure 1, Automation Probability vs. Median Salary for occupations. Each point represents an occupation. A clear negative correlation is visible: occupations with higher estimated chance of automation (toward the right) tend to have lower median salaries (toward the bottom). Lower-wage jobs (clustered near the bottom-left) often have high automation probabilities, whereas higher-wage jobs (top-left region) typically show low automation probabilities. There are a few outliers defying the trend: for example, some high-salary roles (in the top-right quadrant around

$150k+ salary and moderate automation risk ~50 percent) exist – these might be certain specialized analytical jobs that pay well yet involve repetitive or automatable components. Likewise, a handful of very low-salary jobs appear on the far left with lower automation probability – possibly roles that are so low-paid or involve personal services that automation hasn’t targeted them yet. Overall, however, the downward slope of the blue trend line confirms that automation risk and wages are inversely related in our data.) Exist – these might be certain specialized analytical jobs that pay well yet involve repetitive or automatable components. Likewise, a handful of very low-salary jobs appear on the far left with lower automation probability – possibly roles that are so low-paid or involve personal services that automation hasn’t targeted them yet. Overall, however, the downward slope of the blue trend line confirms that automation risk and wages are inversely related in our data.

This negative wage-automation correlation has direct implications for developing countries. Many jobs in African economies are low-paying – for instance, agricultural labor, basic manufacturing, or clerical work – and these jobs often involve routine tasks that could be automated by technologies that already exist (or are on the horizon). Our findings warn that such jobs are in the “high risk” category. In contrast, jobs that require higher education/skills (which are less common in low-income countries) not only pay more but are relatively safer from automation in the near term. This dichotomy sets the stage for potential inequality: without intervention, automation could hit the poorest workers the hardest, while augmenting the productivity (and incomes) of the better-off professionals.

Task-Level AI Usage Patterns: Augmentation vs. Automation and Skill Disparities

We now turn to the empirical evidence on how AI is being used for tasks across different jobs, drawing on the Anthropic Economic Index data. These findings complement the regression results by illustrating what kinds of tasks are likely driving the observed patterns (e.g., which tasks are being automated in low-wage jobs, and how high-skill workers are using AI as a tool).

A headline result from Handa et al. (2024) was that AI usage is split roughly 60/40 between augmenting and automating tasks. Our analysis of their data confirms this: about 57 percent of observed AI task usage corresponded to augmentation of human work, whereas 43 percent corresponded to outright automation. Augmentation here means the AI is used in a supportive capacity – for instance, helping a person draft or improve a piece of writing, or the person iteratively working with AI (like debugging code) – while automation means the AI is basically doing the task once given an instruction (e.g., generating a complete report or answer with minimal human involvement). This breakdown is significant because it suggests that most people are currently leveraging AI to enhance their own productivity rather than to fully replace human effort in a task.

Figure 4.

Augmentation vs. Automation.

Figure 4.

Augmentation vs. Automation.

AI Usage: Augmentation vs. Automation. This chart illustrates the proportion of AI usage instances that fall into each category, based on an analysis of millions of AI (Claude) conversations mapped to work tasks. Approximately 57 percent of AI’s contributions were judged to augment human capabilities (blue slice) – examples include AI helping to brainstorm ideas, refine a draft, or teach the user something (a collaboration). The remaining 43 percent were automation cases (red slice), where AI essentially completed tasks that humans would otherwise have done (for example, translating a document or writing a chunk of code from scratch on command). This empirical ratio (roughly 3:2 in favor of augmentation) indicates that, at least in the current early phase of AI adoption, augmentation is the slightly more prevalent mode of interaction. From a labor perspective, augmentation tends to have more positive implications for workers – studies have shown it can improve productivity without eliminating the human role. Automation, while beneficial for efficiency, can directly displace certain task responsibilities from workers.

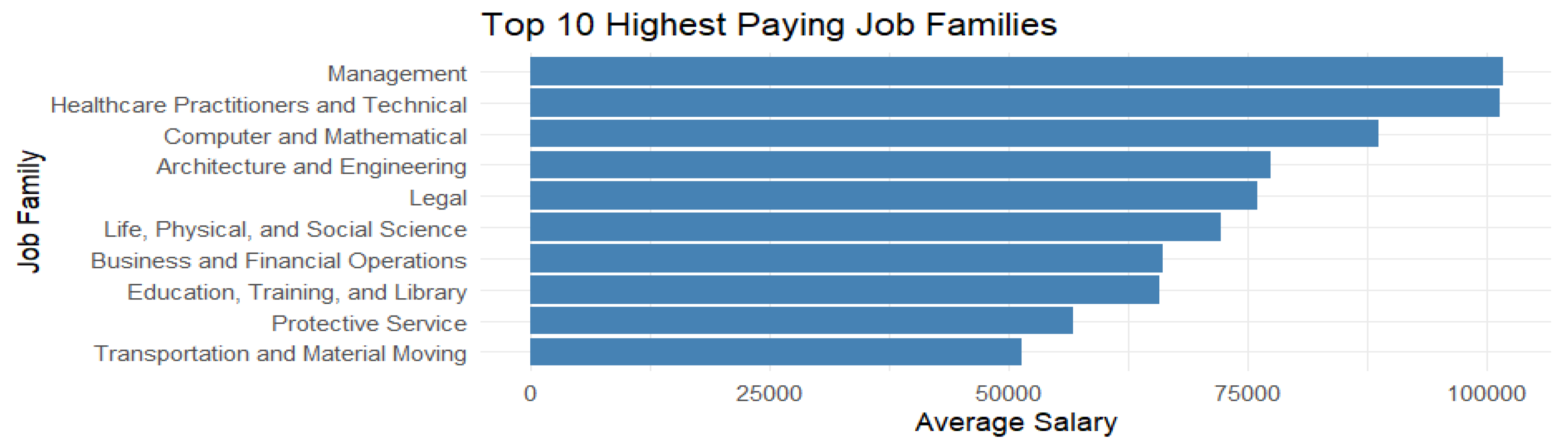

Digging deeper, the task data shows a concentration of AI usage in certain task domains. Two categories stand out: software development (coding) and writing tasks. Together, tasks related to software programming and writing (such as drafting text, summarizing, creating documentation) account for nearly half of all AI usage observed in the dataset. This means that a significant portion of current AI-human interactions in work contexts are about writing code or prose. It aligns with the capabilities of current AI models (which are particularly adept at language generation and code suggestions). For example, many users employ AI coding assistants to troubleshoot or generate code (augmented coding), and many use AI writing assistants to compose emails, reports, or marketing copy. These tasks traditionally fell to relatively skilled workers – software developers, content writers, marketing professionals, etc. – which suggests that medium- to high-skill white-collar work is already being impacted by AI, primarily in an augmentative way. Indeed, the anthropic data found that a vast majority of “feedback loop” interactions (iterative conversations) were related to coding and debugging tasks, which is a clear case of augmentation: the programmer remains in the loop, guiding the AI and verifying output, thereby enhancing their coding productivity rather than being replaced outright. On the other hand, many “directive” interactions (one-shot requests) were content generation tasks like writing emails or essays– tasks where the

AI can often produce a complete draft to be lightly edited by the human, blurring the line between augmentation and automation. These patterns illustrate that even within cognitive work, some tasks are handed fully to AI (automation of routine writing), while others involve tight human-AI collaboration (augmentation in complex coding). The figure below shows the top high paying jobs by job family.

Figure 5.

Job family Vs. Median salaries.

Figure 5.

Job family Vs. Median salaries.

Another critical finding is the stark disparity between AI usage in cognitive vs. physical tasks. As alluded to in the literature review, tasks requiring physical manipulation, sensory work, or in-person presence showed negligible AI usage in the data. For instance, tasks categorized under skills like “Equipment Maintenance”, “Repairing”, “Installation” were among the least represented in AI interactions. In contrast, tasks involving “Critical Thinking”, “Programming”, “Writing”, and even “Active Listening” (a conversational skill simulated by AI) were highly represented.

Figure 3 (drawn from the anthropic study’s results) conceptually illustrates this gap. In AI usage data, cognitive skills dominate – e.g., AI frequently demonstrated abilities in generating written content, analyzing information, or logically reasoning through a problem (critical thinking). By contrast, manual or physical skills were virtually absent – AI is not repairing equipment or physically building anything in these interactions. This suggests that current AI is primarily a “brain” rather than “brawn” technology. The implication for the labor force is that jobs centered on brainwork can already either collaborate with AI or be partly replaced by it, whereas jobs centered on manual labor are, for now, less directly affected by AI but also not benefiting from it. For emerging markets, where a larger share of jobs involve manual skills (e.g., agriculture, construction, craft work), this could mean a slower direct impact of AI – however, it might also mean these sectors lag in productivity improvements that AI could offer to more cognitive sectors.

The Anthropic data also revealed how AI usage varies by wage level and job zone (education level), echoing what we saw in the regression but from a task adoption perspective. They found that AI usage was highest in occupations in the upper-middle wage quartile and dropped off at the lowest and highest ends of the wage distribution. Specifically, mid-to-high wage professions like Computer Programmers and Software Developers were heavy AI users (outliers with very high usage), whereas both low-wage jobs (like waiters) and very high-wage jobs (like specialized doctors) showed substantially lower AI usage. This forms a hump-shaped curve of AI adoption against wage – it peaks somewhere around the 75th percentile of wage. The reasons, as interpreted by the researchers, are twofold: lower-wage jobs often involve physical duties or customer interaction that AI (especially language models) cannot do, and extremely high-wage jobs often entail specialized expert tasks (or physical interventions) that current AI isn’t used for, whereas the middle consists of a lot of knowledge workers who can readily use AI for assistance.

Figure 6.

Median salary by Job zone.

Figure 6.

Median salary by Job zone.

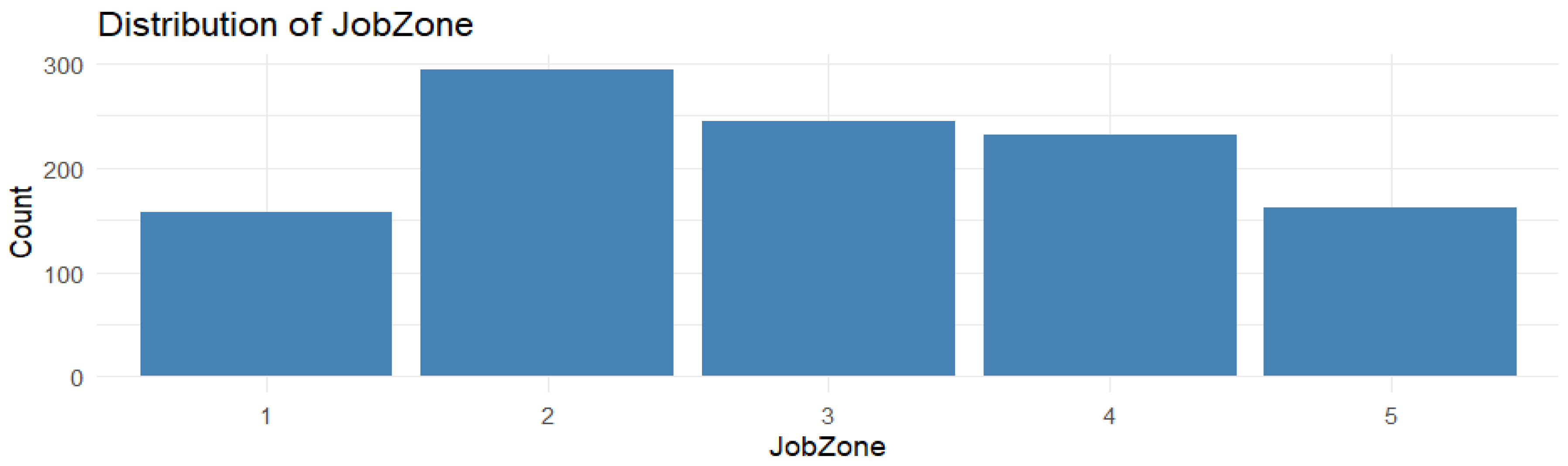

Similarly, when looking at job zones, AI usage was found to increase from Zone 1 up to Zone 4 and then dip at Zone 5 as shown in the Figure below. Job Zone 2(which corresponds to occupations requiring a bachelor’s degree and considerable preparation) had the highest representation in AI usage data, meaning occupations like accountants, analysts, mid-level managers, and IT professionals (typically Zone 4) are extensively using AI tools. Job Zone 5 (advanced degrees) saw a drop – many such roles are physicians, professors, scientists, etc., who at present are not using AI as widely in practice (though this could change as specialized AI tools emerge). Job Zones 1–2 (little to some preparation) had the lowest AI integration, which is expected given those jobs often involve manual or simple routine tasks done in person (e.g., cleaners, laborers, food prep). This job zone pattern strongly correlates with education: AI is most embedded in jobs requiring a college education, less so in both ends (no formal education vs. postgraduate education). For emerging markets, this indicates that the segment of jobs most benefiting from AI (through augmentation) tends to be those that require higher education – which are a smaller slice of the workforce in those countries. Meanwhile, jobs that require very low preparation (common in Africa) are not yet seeing AI help or replace them directly – though they might be indirectly affected if, say, automation in another country reduces demand for certain products or services.

Figure 7.

Distribution of Job zones.

Figure 7.

Distribution of Job zones.

To sum up the task-level findings: AI is predominantly being used as a tool for skilled workers on cognitive tasks (especially in coding and writing), rather than as a robot replacing physical labor. It augments more often than it automates, but a significant portion of automation is happening in tasks like content generation. The usage is uneven, skewed toward middle- and high-skill occupations. These patterns reinforce our regression results in a narrative sense: the jobs that were high in automation risk and low in pay (e.g., routine manual jobs) are exactly the ones not seeing much productive AI usage yet – meaning they have more to lose and little to gain at present. Conversely, the jobs that are high-skill and high-pay are using AI to become even more productive (augmentation), and also had lower inherent automation risk to begin with. This dichotomy is a central theme as we move to discussing implications.

Discussion

The findings from our analysis paint a dual-edged sword scenario for the future of work in Africa and other emerging markets. On one edge, there is the threat of automation disproportionately impacting low-skill, low-wage jobs – a category that encompasses a large share of employment in these regions. On the other edge, there is the promise of augmentation boosting productivity and creating new value in high-skill sectors – sectors which, although smaller in emerging economies, could be engines of growth if properly nurtured. The evidence-driven insights we’ve gathered allow us to move beyond abstract fears or hopes, and instead recognize specific patterns of job transformation. In this discussion, we examine the implications of these patterns for workforce inequality and job transitions, sectorial vulnerabilities and opportunities, and the policy actions that could mitigate risks while capitalizing on augmentation benefits. Throughout, we contrast common policy debates with the empirical evidence, highlighting where data supports or challenges prevailing assumptions.

Workforce Implications: Inequality and Job Transitions

Perhaps the starkest implication of our findings is the risk of widening inequality in the labor market. Both the regression results and the AI usage data suggest a scenario where lower-skill workers could face job displacement or wage suppression, while higher-skill workers enjoy productivity gains and potentially wage premiums. In emerging markets, this manifests as a vulnerability for the large base of the labor pyramid. Many African economies have a high proportion of workers in low-wage informal jobs – for example, street vendors, assembly line workers, call center operators, data clerks, etc. These jobs often involve repetitive tasks and limited formal education requirements, aligning with the high automation risk category (as indicated by their high “Chance of Automation” probabilities and low Job Zones). If technologies like AI and robotics become cheap and accessible enough, firms may attempt to automate these functions. Even the anticipation of automation can affect workers – e.g., dampening wage growth for jobs seen as having low future value.

On the flip side, the relatively small segment of highly educated workers (software developers, engineers, managers, etc.) in these countries could see enhanced opportunities. AI augmentation means that a skilled professional can do more in the same amount of time – for instance, a Kenyan digital marketer using an AI tool can create ads and content much faster, or a Nigerian software startup can use AI coding assistants to accelerate development. This can make such workers more valuable to employers and could increase the demand for their skills, potentially raising their incomes. Moreover, if augmentation leads to higher productivity, companies might expand and even create new roles that complement the AI-augmented work (for example, new specialist roles managing AI systems or handling more complex client interactions that arise from increased output). This dynamic is in line with historical observations where technology creates complementary jobs even as it destroys others.

However, the net outcome for employment is not predetermined – it depends on the balance of these effects and on policy responses. One concern is the pace of change. Developed countries, with their stronger safety nets and retraining systems, at least have some capacity to manage transitions (albeit with difficulty). Many African nations have limited resources for social protection or mass up skilling, meaning a rapid automation wave could lead to significant social strain. For example, if in the next decade AI-powered customer service chatbots replace a large number of call center jobs (which had been a growing employment avenue in some African countries), those displaced young workers may struggle to find alternative employment unless they have been prepared with new skills.

Another aspect is the nature of new jobs that might emerge. The conclusion of the anthropic study speculates that as AI systems gain more capabilities (handling images, driving, robotics), entirely new occupations could emerge around these technologies. We could envision, for instance, jobs like “AI workflow designer” or “robot maintenance technician” becoming common. The big question is whether workers in emerging markets will be positioned to take on those new roles, or if those jobs will predominantly arise (and be filled) in advanced economies. Historically, new tech jobs tend to cluster where the technology is developed and initially deployed. There is a risk of a skills and geographic gap – Africa might not only lose some traditional jobs but also fail to get an equal share of the new tech jobs if its workforce isn’t equipped and if internet and AI infrastructure remain limited. This raises the importance of job transition pathways: helping workers move from at-risk jobs to more resilient ones.

Our evidence suggests a few such pathways. One is upskilling or reskilling programs targeting workers in automatable roles, training them in more cognitive and creative skills that are complemented by AI rather than substituted. For instance, manufacturing production workers could be trained in quality control and machine supervision, turning them from pure manual laborers into technicians who oversee semi-automated production lines – roles that require more problem-solving and thus can work synergistically with AI/automation. Another pathway is encouraging entrepreneurship and new job creation in areas where AI opens opportunities. Augmentation can significantly lower entry barriers for certain businesses (e.g., a small business can use AI to handle tasks that would have required additional employees). This could enable savvy workers to start their own ventures, effectively creating jobs for themselves and others. However, these new ventures often require digital literacy and access to technology; hence, digital inclusion policies (expanding internet access, affordable devices) are crucial.

Without intentional action, the divide could worsen: we might see a small group of AI-empowered professionals and a large group of displaced or stagnant workers – a scenario of “haves and have-nots” in the AI economy. This outcome is not just speculative; it is foreshadowed by the uneven distribution of AI use across wage levels observed empirically. The policy implication is that interventions should aim to democratize the benefits of AI – ensuring that AI tools and training to use them are available not just to an elite, but also to ordinary workers and small businesses. Some countries are experimenting with this, for example by integrating basic AI tool training into vocational programs, or providing incentives for companies that adopt “augmentation” strategies that up skill their workers rather than replace them.

Sectorial Exposure: Which Industries Gain and Lose?

The impact of AI and automation will not be uniform across sectors; our analysis hints at which industries might be more exposed to disruptive change in emerging markets.

Manufacturing: Traditionally, manufacturing (especially light manufacturing like textiles, electronics assembly, etc.) has been a path for low-income countries to develop – leveraging low labor costs to attract factories. Automation presents a challenge to this model. Our regression and data show manufacturing jobs often fall into the category of moderate skill and moderate wage – e.g., machine operators or assembly line workers might be Job Zone 2 or 3 and earn modest wages. These tasks (repetitive, physical but structured) are among those most amenable to automation by robotics. Indeed, in advanced economies, factories are increasingly using robots, reducing the need for human operators. For Africa, this raises the threat of “premature automation”: factories might employ robots from the start rather than hiring many local workers, or they might not set up in Africa at all, choosing to automate in higher-cost countries. This could stunt industrial job growth. Our evidence of a negative automation-salary link reinforces that many manufacturing roles (with relatively low pay) are at risk. However, not all manufacturing will automate overnight – some tasks are tricky for robots (handling delicate materials, custom assembly). Additionally, augmentation has a role: AI can assist human workers in manufacturing through better quality control (computer vision systems flagging defects) or predictive maintenance for machines, potentially improving efficiency without massive job cuts in the near term. From a policy standpoint, manufacturing sectors in emerging markets may need to adopt a dual strategy: upgrade technologically (to stay competitive) while skilling their workforce to work alongside new technology. For example, training operators to manage a fleet of semi-automated machines rather than doing all tasks manually can keep factories viable and workers employed in more supervisory roles.

Services: The service sector is broad, encompassing everything from retail and hospitality to banking and telecom. We observe divergent impacts within services. On one end, hospitality and personal services (cleaners, security guards, waiters, hairstylists) are very low-wage and manual, thus currently relatively safe from AI (which cannot clean rooms or cut hair yet), but they also see little benefit from AI augmentation. These jobs aren’t likely to vanish soon due to AI, but they also aren’t likely to see huge productivity jumps. Over time, some automation might creep in (e.g., automated checkouts or robotic floor cleaners), affecting the number of such jobs. On the other end, informational and financial services are heavily impacted by AI already – for instance, chatbots in customer service, algorithms in loan processing, AI in accounting software. In Africa, banks and telecom companies are using AI for things like fraud detection and customer support, which can reduce back-office headcount or repurpose employees to more complex tasks. The Anthropic data’s indication that writing and administrative tasks are commonly automated by AIsuggests that office support roles (secretaries, clerks) may diminish. However, new service roles may grow – such as data analysts, digital marketing experts, or AI system monitors – if companies invest in these capabilities locally. The IT and software sector in particular stands to gain in emerging markets, as it can leverage global remote work opportunities: an African software engineer augmented by AI coding tools can compete more effectively for projects worldwide. This sector, though small in many African countries, could be a target for growth as it benefits directly from augmentation and is in the sweet spot of high AI usage. Governments might thus want to foster the ICT sector as a strategic move, through tech hubs, training programs, and incentives, betting that these jobs are both future-proof (augmentation-rich, lower automation risk) and can create spillovers for the economy.

Agriculture: Agriculture remains a major employer in many emerging markets, including much of Africa. Most agricultural work there is low-wage, low-skill manual labor (Job Zone 1). According to our analysis, such jobs have high automation potential in theory (farming tasks can be mechanized) but low AI usage in practice (current AI is not directly plowing fields in Africa). Large-scale farms in developed countries use advanced automation (tractors with AI, drones for crop monitoring), but smallholder farming (dominant in Africa) has seen less of that, largely due to cost and infrastructure barriers. Over time, cheaper agri-tech (like affordable smart irrigation systems or AI-driven crop advice apps) might augment farmers, helping them increase yields (for example, an AI service that gives pest control advice via SMS could be seen as augmentation of the farmer’s decision-making). Automation in the sense of robots replacing farmers is unlikely in the near term in Africa. So agriculture might not lose jobs rapidly to automation; the challenge is more that it might not gain much productivity without technology infusion. This creates a risk that agriculture falls further behind other sectors productivity-wise, keeping rural incomes low. It underscores a policy point: augmenting agriculture through AI (in extension services, market information systems, etc.) could have big payoffs for income and food security. For example, an AI-powered platform that guides farmers on optimal planting times or connects them to buyers can improve their outcomes without replacing their agency. There are startups doing this (using AI to analyze weather and give localized farming advice). Governments and development agencies can support scaling these innovations. In essence, agriculture in emerging markets might be more about AI augmentation for resilience rather than automation for labor reduction.

Public Sector and Education: Government jobs (teachers, administrators, healthcare workers) are also significant in many countries. These tend to be higher-skilled on average (teachers and health professionals are Job Zone 4 or 5). AI offers tools to augment these roles – e.g., AI tutors to help teachers, diagnostic tools to assist doctors. If harnessed, this can improve public service delivery. The risk of direct automation (replacing teachers or doctors with AI) is low for now due to the need for human judgment and trust. However, some administrative government roles (filing paperwork, data entry at offices) might be streamlined by AI, potentially reducing clerical positions. Given tight budgets in many African public sectors, augmentation could be a welcome productivity booster, but care should be taken that it doesn’t widen the urban-rural divide (i.e., only central ministries use AI while rural clinics still lack basic resources). A positive aspect is that public sector could lead by example in responsible AI adoption, training its workforce and setting standards that could then be adopted by private firms.

In summary, sectors with routine, structured tasks (manufacturing, formal services) face more automation pressure, whereas sectors with either very manual tasks (personal services, agriculture) or highly complex tasks (advanced professional services) face more of an augmentation dynamic or slower change. For emerging markets, this means industrialization strategies may need rethinking – the old model of abundant cheap labor as the main draw is weakening. Instead, competitiveness may require integrating technology (to achieve quality and efficiency) and developing human capital to manage that technology. Sectors that leverage human creativity and interpersonal skills (where AI provides support but not full replacement) could become comparatively more important job creators than before. Creative industries, tourism (with enhanced digital marketing), and care economies might grow if nurtured, as they are harder to automate but can be enhanced with AI assistance in planning and outreach.

Policy Implications: Education, Reskilling, and Industrial Policy in the AI Era

The evidence-driven insights from our study suggest that policy responses should be targeted, proactive, and data-informed. We have seen that not all jobs are equally affected by AI and automation – hence, blanket policies may be inefficient. Instead, policymakers in Africa and similar contexts should focus on strategies that address specific vulnerabilities (like low-skill workers at risk) and bolster areas of potential growth (like tech-augmented sectors). Here we outline several policy recommendations and how they align with the observed trends:

1. Prioritize Education and Skills Training for the AI age: Education systems must adapt to produce graduates with skills that complement AI, not compete with it. This means a greater emphasis on cognitive skills, creativity, critical thinking, and complex problem-solving – the kind of skills that our analysis shows are augmented by AI, and which AI cannot easily replicate on its own. In practical terms, curricula in secondary and tertiary education should incorporate not only STEM (science, technology, engineering, math), but also soft skills and digital literacy. Moreover, introducing basic AI tools and concepts in the classroom can demystify the technology and equip students to use it productively. For the current workforce, reskilling and upskilling programs are crucial. Governments could partner with the private sector to establish training centers that teach workers how to use AI in their field – for example, courses for accountants on AI-based analytics, or programs for factory workers on operating automated machinery. Our findings highlight “Job Zone transitions” as an avenue: moving a worker from a Zone 2 role to a Zone 3 or 4 role through education can significantly increase their earnings and reduce automation risk. Vocational training programs could be revamped to target skills in emerging job profiles (like drone operation, AI system maintenance, digital marketing). Importantly, access to these programs in emerging markets should be broad-based – not just in capital cities. Mobile training units or online platforms can help reach workers in remote or underprivileged areas. International development organizations can assist by funding such training initiatives as part of economic development projects.

2. Encourage Augmentation over Pure Automation: Policymakers can influence how firms adopt AI. Given that augmentation (collaborative use of AI) has more favorable outcomes for employment than full automation, policies could incentivize companies to augment rather than replace. This might involve tax credits or subsidies for companies that implement AI in ways that up skill their workforce or create new complementary jobs. For instance, a manufacturing firm that invests in exoskeletons or AI decision-support for workers (which make workers more productive) could be rewarded more than a firm that simply buys robots to cut workers. Governments could also support pilot projects that demonstrate successful augmentation: e.g., a public-private initiative in an agriculture extension department showing how AI advice tools increase farmer productivity while keeping farmers central. The aim is to spread best practices for integrating AI without massive layoffs. This doesn’t mean halting automation where it’s beneficial – rather, it means guiding the process so that humans remain an integral part of the workflow. Research has shown that augmentative uses of AI can boost productivity significantly while maintaining human engagement, which suggests a win-win if done correctly. Regulators might also consider requiring or encouraging impact assessments when companies deploy AI that could displace workers, similar to environmental impact assessments. These assessments would force firms to think about retraining or transitioning affected employees, possibly under oversight.

3. Sector-Specific Strategies: Each sector might need tailored policies to manage AI’s impact:

Manufacturing: For countries aiming to develop manufacturing, one strategy could be to focus on advanced manufacturing niches where human labor plus AI-enabled tech can be competitive (since competing purely on cheap labor is less viable if robots undercut that advantage). For example, some African countries are exploring Industry 4.0 parks where companies get support to use IoT (Internet of Things), AI, and automation with a skilled workforce. Governments could invest in these zones, ensuring training facilities are on-site. Additionally, trade policies might be needed – e.g., tariffs on imported fully-automated products or incentives for foreign investors to create jobs, not just bring automated plants. This is tricky (as too much protectionism can deter investment), but the idea is to negotiate deals where tech transfer and human job creation are part of foreign investment in manufacturing.

Services: Embrace digital services as a growth area. This could mean improving internet infrastructure (so that a gig worker or freelancer in an African city can reliably work online with clients abroad, augmented by AI tools), reforming regulations to support startups (many of which will use AI heavily), and perhaps most importantly, ensuring data protection and AI ethics frameworks are in place to build trust. For example, as AI gets used in banking (say for credit scoring), regulators need to ensure transparency and fairness to avoid biases that could deny opportunities to certain groups – a relevant issue in diverse societies. Tourism and retail sectors might innovate by using AI for personalization and efficiency, but governments should facilitate SMEs (small businesses) adopting these innovations by providing technical assistance or shared services.

Agriculture: Invest in agri-tech innovation and diffusion. Governments and NGOs could subsidize the adoption of proven AI-based advisory services for farmers, or use public broadcasting to disseminate AI-generated insights (like climate-smart farming tips). Also, support mechanization where appropriate; for instance, joint ownership schemes for automated machinery can allow small farmers to benefit from automation in a cost-effective way. Policymakers should also think ahead about rural employment – as agriculture becomes more efficient (augmented by tech), surplus labor needs avenues to transition (perhaps to rural service jobs or agro-processing industries). This loops back to rural education and training in new skills.

Education and Healthcare: For these critical public services, policy should promote AI as a tool to extend reach and quality. Tele-education and telemedicine got a boost during the COVID-19 pandemic, and AI can enhance these (e.g., AI tutors for students, diagnostic algorithms for remote health clinics). Governments can officially integrate such tools into their systems after vetting, which could help mitigate skilled personnel shortages. Notably, deploying AI here can free up human professionals to focus on what humans do best (teachers spend less time grading rote answers and more time on individual coaching; doctors spend less time on paperwork and more on patient interaction).

4. Strengthen Social Safety Nets and Labor Market Institutions: Even with the best training and augmentation strategies, some displacement is inevitable. Countries should proactively strengthen their social safety nets to support workers through transitions. This is challenging in low-income countries with small tax bases, but even incremental improvements help – such as unemployment insurance pilots in urban areas, cash transfer programs that can be expanded in crises, and public works programs that can absorb displaced workers temporarily. Additionally, labor market institutions (like job placement services or online job platforms) need to be modernized. Governments can create or support labor market information systems that use AI themselves to match workers to emerging job opportunities or identify skills gaps. An evidence-driven approach might track where jobs are declining and where they are growing in real-time (using data from job postings, etc.), so that policymakers can respond quickly with targeted measures (like a local retraining drive if a certain industry is automating). Unions and worker associations in emerging markets also have a role – they can negotiate for retraining funds and fair adjustment processes when automation is introduced in companies. The policy should encourage a collaborative approach between employers and employees when integrating AI – perhaps through frameworks that include workers in discussions about tech adoption plans.

5. Data-Driven Policy and Continuous Research: One of the clear messages from our study is the value of data in understanding AI’s impact. Policymakers should invest in collecting and analyzing labor market data with an AI lens. This could mean working with researchers to replicate something like the Anthropic Economic Index in their country – e.g., analyze how local businesses are using AI tools, or map local job tasks to AI capabilities. Having this data allows for evidence-based decisions rather than guesses. For example, if data shows that in your country AI is mostly used in the finance sector and not at all in retail, you can tailor your strategy sector-wise. International cooperation is also beneficial: sharing data and insights (possibly via the ILO or World Bank) can help countries learn from each other. Moreover, keeping an eye on global AI trends (like the advent of autonomous vehicles or breakthroughs in robotics) can help countries anticipate which jobs might be next affected. For instance, if autonomous trucks become reliable, a country with many truck drivers should be planning alternative careers for those drivers in the next decade.

Contrasting Policy Debate with Evidence: Often, the policy debate on automation swings between utopian (AI will solve our productivity problems and create better jobs) and dystopian (AI will cause mass unemployment). The evidence we’ve discussed suggests a more nuanced reality. Yes, AI can increase productivity – but predominantly for those with the skills to use it. And yes, some jobs will disappear – but not overnight, and mostly the routine ones. There is also room for policy to shape outcomes: countries that actively guide the AI transition (through education, incentives, and safety nets) are likely to fare better than those that passively react. For example, a common debate is whether robots will take all manufacturing jobs. Our evidence shows many such jobs are automatable, but also that having humans plus AI can be productive. So a policy stance that simply resists automation to “save jobs” might backfire if it leads to uncompetitive industries; a better approach is to combine technology with workforce development. Another debate is whether AI will create more jobs than it destroys (the historical optimists’ view). The data we have is early and cannot conclusively answer that, but it provides clues: the fact that many occupations are already using AI for a portion of taskssuggests tasks will be redistributed rather than whole jobs instantly vaporized. It implies a period of transition where humans work with AI, which is an opportunity to adjust gradually. Therefore, instead of arguing about total job loss/gain numbers (which vary by study), it may be more productive for policy discussions to focus on job transformation – how to change the content of existing jobs and the skill set of workers to fit the new task mix. Our regression underscores that even transformed jobs will obey economic logic: skill and unique human value will command pay. So investing in human capital is still the right answer, as it has been before, but now we must ensure the human capital we build is complementary to AI, not substitutable.

In conclusion of this discussion, the key message for policymakers in Africa and emerging markets is one of active adaptation. Automation and AI will not simply replay the experiences of developed countries a decade later; they are arriving at a time when these technologies are more mature and ubiquitous. Emerging markets must therefore leapfrog in terms of readiness: adopt AI where it helps, guard against its risks, and above all, equip their people to thrive alongside intelligent machines. The evidence we have compiled provides a roadmap of where to act – focusing on vulnerable worker groups, harnessing augmentation in promising fields, and steering the technological change in alignment with development goals.

Conclusions

This study set out to explore how jobs are evolving in the face of automation and AI, with a focus on Africa and emerging markets, using a data-guided approach. By anchoring our analysis on a regression model of median salaries and drawing on detailed task-level AI usage evidence, we have been able to identify concrete patterns in the transformation of work. The findings reinforce several core insights:

Jobs with higher automation risk tend to be lower-paid and lower-skilled, a relationship clearly evidenced by the significant negative coefficient between automation probability and wages in our regression. In emerging markets, this means a large portion of the workforce is in the crosshairs of automation, given the prevalence of low-wage, routine jobs.

AI’s current use across the economy is skewed toward augmenting human workers in cognitive tasks rather than replacing physical labor. Approximately 57% of AI usage appears to enhance human capabilities (learning, iterating, improving outputs) while 43% automates tasks entirely. This nuance is critical: it suggests that, at least in the present, AI is more partner than competitor for many skilled workers, particularly in fields like software development and writing. However, as AI technologies advance (e.g., into robotics and more autonomous systems), this balance could shift, and the range of tasks AI can perform will expand.

There is a pronounced skill and wage bias in who benefits from AI augmentation. Occupations in higher job zones (requiring greater preparation) and those in the upper-middle of the wage distribution show the greatest AI adoption and integration. These are often the professional and technical roles that are already scarce in Africa. Meanwhile, those at the bottom of the pyramid – low-skill workers – are not yet significantly benefiting from AI and may in fact be at risk if automation encroaches on their tasks from another direction (e.g., via imported technology). This dynamic foreshadows an exacerbation of inequality if left unchecked.

The correlation between low wages and high automation risk observed in the data signals a potential trap for developing economies: historically, countries climbed the income ladder partly by moving workers from low-productivity (often low-wage) jobs to higher-productivity sectors (manufacturing, formal services). If those higher-productivity sectors now automate in a way that bypasses the workforce, that traditional escalator could break. At the same time, the advent of AI opens new avenues – digital services, online gig work, creative industries – that were not previously available, offering alternative paths for economic diversification if leveraged.

Bringing these threads together, our analysis underscores the importance of evidence-driven policy. The data shows where intervention is needed: in raising skill levels, in guiding the form of AI adoption, and in protecting those most likely to be adversely affected. For Africa and emerging markets, the challenge is to avoid being passive recipients of automation trends and instead to become active shapers of how technology integrates with their labor markets. That means investing in human capital aggressively, modernizing education and vocational systems, and fostering an environment where AI is used to complement the workforce rather than marginalize it.

There are reasons for cautious optimism. The fact that AI is primarily used as an augmenting tool today gives countries a window of opportunity – a chance to ride the augmentation wave to boost productivity and upskill workers, before more disruptive automation waves break. If, for example, African software engineers and entrepreneurs can harness AI to create new applications and industries, they can generate jobs and wealth, turning the continent into not just a consumer of AI solutions but a producer of them. Initiatives in several countries to support tech startups, AI research labs, and digital innovation hubs are steps in the right direction. Moreover, international cooperation can help – sharing best practices on managing automation, ensuring fair AI governance (so that, say, AI doesn’t entrenched bias against workers from certain regions), and perhaps creating global funds to assist developing nations in the tech transition (analogous to climate transition funds).

At the same time, there are serious risks that must be managed. If automation outpaces the capacity of economies to adapt, we could see rising unemployment, especially among youths who form a large portion of Africa’s population. Social unrest and migration pressures could follow. Thus, governments need contingency plans – robust social safety nets, public employment programs, and continuous dialogue with industry and civil society about the changes underway. The policy responses we discussed are not one-off but need to be sustained and evolved as new data comes in. In essence, adaptability will be a key virtue: policies might need to pivot when, for instance, a breakthrough in AI suddenly makes a new set of tasks automatable.

In conclusion, the evolution of jobs under the twin forces of automation and AI is a complex, multifaceted process. This paper has provided a structured analysis of this process, combining quantitative modeling and empirical data to yield insights relevant for emerging markets. The central message is that while technology is transforming work, human agency – through skills development and smart policy – can and should shape that transformation to ensure broad-based benefits. Africa and other developing regions have the advantage of learning from earlier adopters; they can avoid mistakes and leapfrog where possible. The coming years will be crucial. By heeding the signals in the data – the task composition of AI usage, the early impacts on wages, the areas of augmentation potential – policymakers and stakeholders can craft strategies that turn the looming challenge of automation into an opportunity to build a more skilled, productive, and equitable workforce for the future.

References

- Acemoglu, D. (2021). Harms of AI: Economic and policy implications. MIT Work Paper.

- Autor, D. (2015). “Why Are There Still So Many Jobs? The History and Future of Workplace Automation.” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(3): 3-30 (discusses augmentation vs. automation).

- Frey, C. B., & Osborne, M. (2017). “The Future of Employment: How Susceptible are Jobs to Computerisation?” Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 114: 254-280 (automation risk and wage/education negative relationshipoxfordmartin.ox.ac.uk).

- Handa, K., Tamkin, A., McCain, M., Huang, S., et al. (2024). “Which Economic Tasks are Performed with AI? Evidence from Millions of Claude Conversations.” ArXiv preprint arXiv:2503.04761 (Anthropic Economic Index; AI task usage patterns).

- Noy, S., & Zhang, W. (2023). “Experimental Evidence on Productivity Effects of Generative AI.”.

- Comunale, M., & Manera, A. (2024). “The Economic Impacts and the Regulation of AI: A Review of the Academic Literature and Policy Actions.” IMF Working Paper WP/24/65 (noted limited literature on AI in low-income countriessites.google.com).

- Anthropic Claude Team (2024). Anthropic Economic Index Data (ONET task mapping and AI usage)* – used for empirical task analysis.

- Webb, M. (2019). “Predicting the Impact of AI on Jobs.” Working Paper. (develops methodology linking AI capabilities to tasks, referenced in Anthropic introduction.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).