1. Introduction

Lava flows represent complex thermofluid phenomena in which a solidified surface layer forms as a result of surface cooling during flow. Understanding the influence of such a solidified surface layer on fluid flow is a fundamental problem, not only in geophysical contexts but also in a wide range of engineering applications. In mechanical engineering, similar phenomena are exemplified by the formation, deformation, and fracture of solidification shells and thin surface skins in continuous casting. Related surface-solidification phenomena are also observed in welding processes, where thin solidified layers can appear on the surface of molten pools and are associated with weld surface formation [

1]. These geophysical and engineering phenomena share essential characteristics.

In lava flows, it is known that two types of solidified surface layers are formed depending on the surface cooling conditions [

2]. When the cooling rate is high, the lava surface undergoes supercooling and becomes an amorphous glass. As a result, a thin solidified layer (skin) is formed, which deforms plastically. On the other hand, when the cooling rate is low, crystallization progresses and a rigid solidified layer (crust) is formed.

Based on observations of flowing lava, Hon et al. [

3] described the advance of lava accompanied by the skin and the crust. The advance is interpreted as a repeated sequence of the processes outlined below. Initially, a plastically deformable skin with a thickness of approximately 1–2 mm forms on the lava surface. This skin retains the high-temperature lava inside and suppresses its motion. As the flow velocity decreases and cooling progresses further, a rigid crust begins to grow from the skin. When the crust thickness reaches several centimeters, it becomes strong enough to halt the incoming lava. Subsequently, when the crust is locally broken due to an increase in internal pressure, the interior lava flows out again, and the surface returns to a state without a solidified layer.

Furthermore, the rheological properties of lava flows are known to change from Newtonian to non-Newtonian behavior due to the presence of crystals and bubbles within the lava [

4]. It has been reported that silicate melts and lavas with a low crystal fraction can be treated as Newtonian fluids over a wide range of temperatures and strain rates [

5,

6]. On the other hand, lavas with a high crystal fraction exhibit Bingham behavior with a finite yield stress [

2]. This change in rheological properties has a significant influence on lava flow dynamics. In addition, lava is also a glass-forming liquid that forms an amorphous glass upon rapid cooling. Its viscosity shows a strong temperature dependence near the glass transition temperature [

7].

For the mitigation of damage caused by lava flows, accurate prediction of lava flow behavior is an important social demand. Many previous studies have focused on lava properties and characteristic flow phenomena. These factors must be appropriately incorporated into predictive models. In the context, numerous studies have been conducted on lava flows using a variety of approaches, including field studies [

3,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11], experimental modeling [

4,

12,

13,

14], and numerical simulations [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25].

Field studies include observations of lava flow behavior and cooling processes [

3], as well as analyses of the rheological properties of remelted samples of solidified lava [

7,

8]. In addition, direct measurements of flowing lava have been conducted to evaluate rheological properties, surface temperature, and flow velocity [

9]. However, due to the low frequency of eruptions accompanied by lava flows and the complexity of the phenomena, there are limitations to achieving a comprehensive understanding based only on field observations.

Therefore, analog experiments and numerical simulations play an important role in the study of lava flows. In analog experiments, polyethylene glycol (PEG) is often used to model lava. The materials can reproduce the formation of a rigid crust associated with surface cooling [

12,

13,

14]. Based on these analog experiments, Lyman et al. [

13,

14] extended the similarity solution for viscosity-dominated gravity currents proposed by Huppert [

26]. They incorporated non-Newtonian behavior and introduced the formation of a surface crust as a stopping condition for the flow. On the other hand, these models do not account for the influence of a plastic surface skin on flow behavior.

In numerical simulations, models based on the shallow water equation are widely used in operational forecasting of lava inflow areas [

15]. Because these equation treats velocity and temperature distributions as depth-averaged quantities, it is difficult to directly represent phenomena that involve vertical structure, such as viscosity changes associated with surface cooling and the formation of a solidified surface layer.

Phase changes by cooling and deformation of solid–liquid interfaces complicate numerical simulations. For this reason, several previous studies have proposed simplified models for heat transport and phase change. For example, Starodubtsev et al. [

18,

19] represented solidification behavior indirectly by introducing a time-dependent viscosity model, without solving heat transport. In addition, mesh-based computational methods such as finite volume and finite element methods have the disadvantage of requiring remeshing to accurately treat the deformation of the solid–liquid interface [

16,

17]. In contrast, smoothed particle hydrodynamics (SPH) which is one of mesh-free particle methods, is well suited for simulating flows with phase change and free surfaces. Despite this advantage, only a few studies have reported lava flow simulations that consider heat transport and solidification using particle methods [

20,

21,

22,

24,

25].

Hérault et al. [

24] conducted lava flow simulations for the actual topography of Mt. Etna, considering heat transport, temperature-dependent viscosity, and non-Newtonian rheology. Through qualitative comparisons with observed volcanic landforms and numerical results, they demonstrated the necessity of modeling lava flows as non-Newtonian fluids with temperature-dependent viscosity. However, this study did not provide a detailed discussion of the specific shapes or formation processes of characteristic lava flow structures, such as lava levees and lava accumulations. Tomita et al. [

25] conducted SPH simulations of lava flows using molten metal as an analog material. Under simplified conditions, they successfully reproduced the morphology of characteristic lava flow structures and discussed their geometrical features. Nevertheless, previous studies [

20,

21,

22,

24,

25] have not sufficiently considered the formation of a surface skin or its influence on flow behavior.

Therefore, the objective of this study is to clarify the influence of the plastic surface skin on lava flow behavior. In this study, two-dimensional SPH simulations are conducted to analyze the flow of a virtual fluid representing lava. The fluid flows down on a horizontal plate while forming a plastically deformable surface skin. The plastic surface skin is represented as a low-temperature, high-viscosity region, through the introduction of a temperature-dependent viscosity.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Validation of Numerical Simulations via Comparison with Similarity Solutions

In this study, numerical simulations were considered for a Newtonian fluid with constant viscosity that is instantaneously released onto a horizontal plate. The simulation results are compared with known theoretical scaling laws formulated for viscous-dominated flows [

26], as follows:

where

L is the flow length,

g is the gravitational acceleration,

q represents the cross-sectional area of the released fluid. The constant

is a dimensionless coefficient determined by the similarity solution [

26]. In the case of a two-dimensional flow,

.

denotes the density difference between the fluid and the ambient medium. In the present simulations, the ambient medium is not modeled. Therefore,

is taken as

. This assumption is reasonable for lava flows, since

.

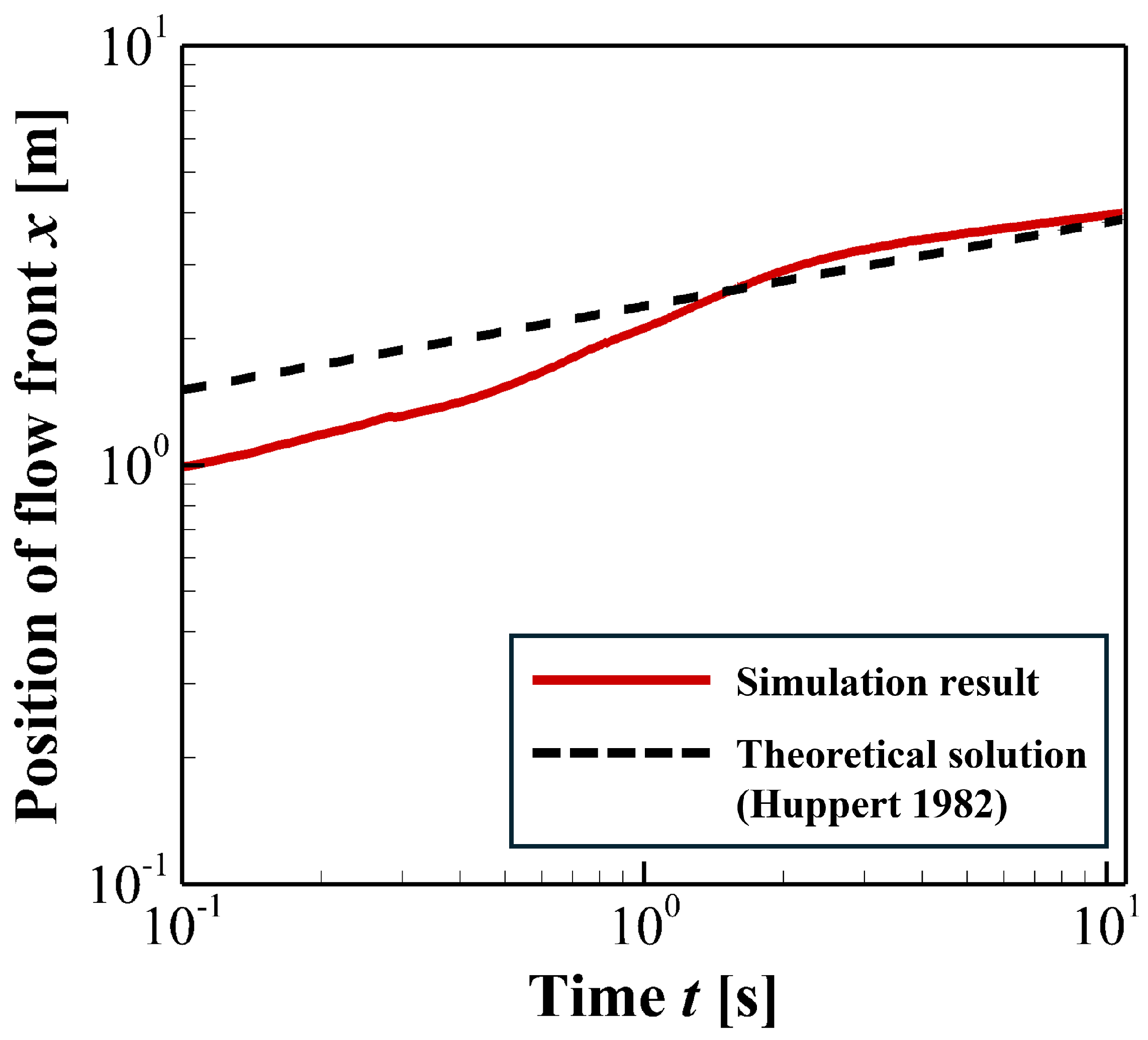

Figure 4 compares the simulated flow length of condition

N with the theoretical solution proposed by Huppert [

26]. To compare the simulation results with the theoretical scaling, it is necessary to identify the time range in which the flow is dominated by viscous effects. In actual physical processes, the early stage flow behavior is influenced by inertial slumping, which precedes the viscous-dominated flow [

13]. Therefore, this initial transient stage should be excluded from the quantitative comparison.

According to the scaling relation given by Equation

25, the flow length follows

in the viscous-dominated flow. When the flow follows the scaling, the quantity

becomes constant. Therefore, the compensated quantity

is introduced and evaluated to diagnose the transition to the viscous-dominated flow.

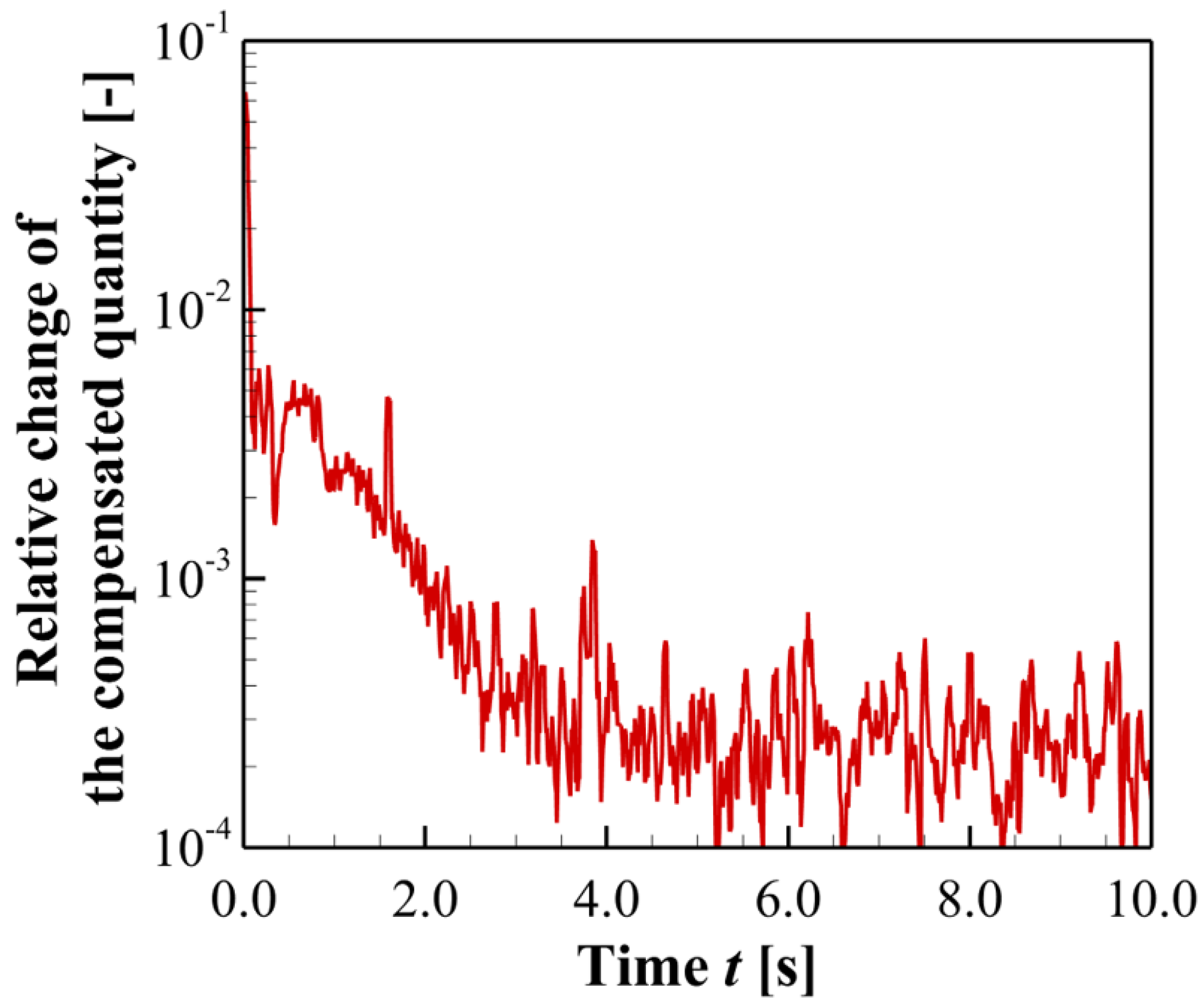

Figure 5 shows the time evolution of the relative change of the compensated quantity, described as

. As time progresses, the magnitude of the relative change decreases. After approximately

, the relative change remains at a low level of order

. Based on

Figure 5,

is adopted as the viscous-dominated regime.

For the data within the viscous-dominated regime, the relative root-mean-square error (rRMSE) between the simulation result of condition

N and the theoretical solution proposed by Huppert [

26] is evaluated. The resulting rRMSE is

. This result indicates that the simulation results agree with the theoretical scaling within a relative error of approximately

.

In the following analysis, the time exponent is fixed to , and only the constant is treated as a fitting parameter. The value of is determined by minimizing the rRMSE between the simulation result and the theoretical scaling. As a result, the optimal value is found to be , while the theoretical value is . With this optimized prefactor, the rRMSE is reduced to . This result indicates that the temporal scaling predicted by the theory is well reproduced by the simulation.

These results indicate that the numerical simulations show reasonable agreement with the known theoretical scaling laws. This agreement supports the validity of the simulations for the Newtonian condition.

For Bingham fluids, Lyman [

13] proposed a theoretical model that describes the final stopping position of a flow front. This model is derived from the static balance between the yield stress and the gravitational driving force. The theoretical stopping length

is given by

In this study, the numerical simulation results of condition B are compared with this theoretical prediction, with a focus on the final flow length at stopping.

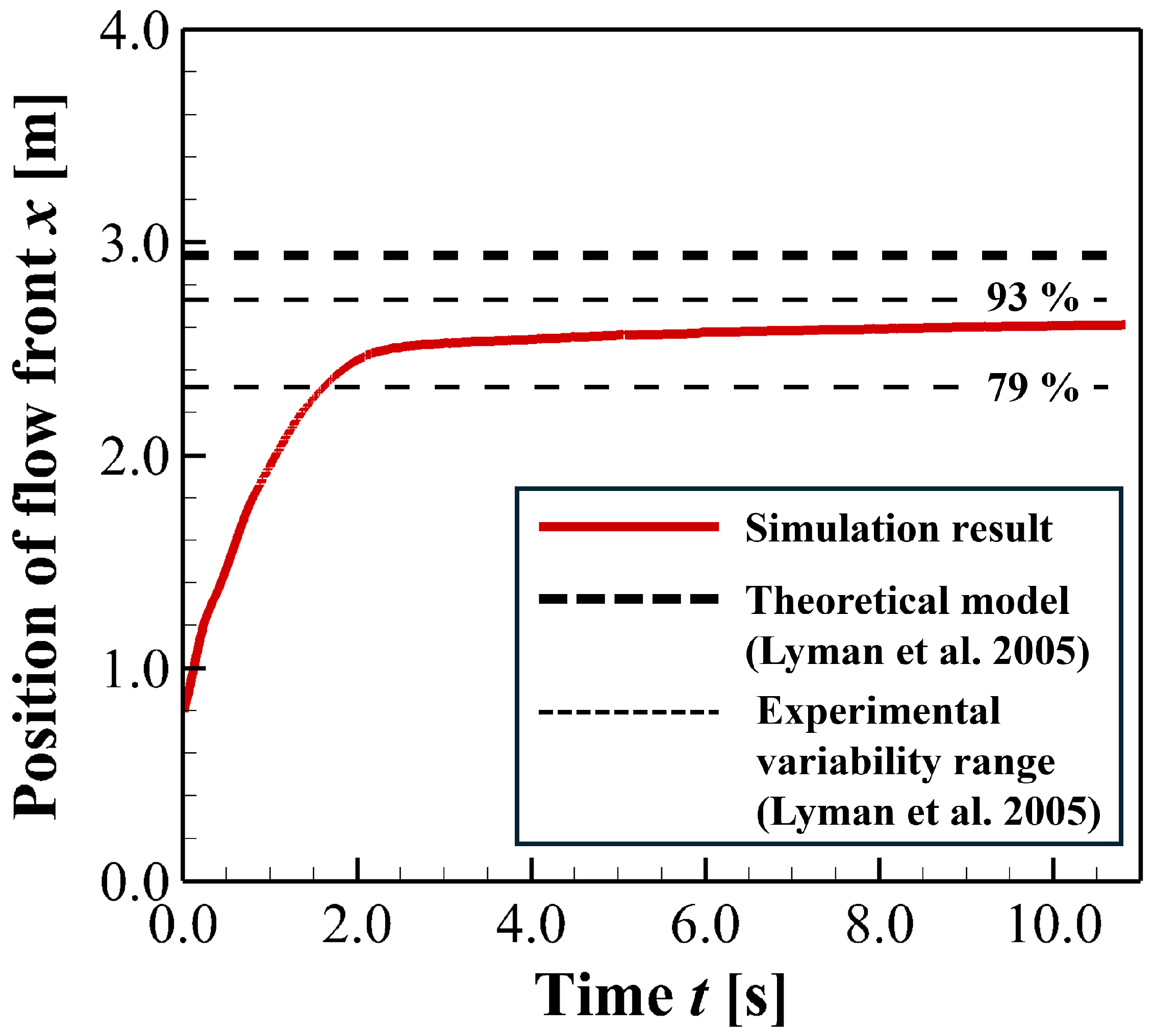

Figure 6 shows the temporal evolution of the flow front position obtained from the numerical simulation for condition

B. The final stopping position predicted by the theoretical model of Lyman [

13] is also shown for comparison.

As shown here, the stopping length measured from the origin in the simulation is approximately

. In contrast, the theoretical model predicts a stopping length of

. The stopping length obtained from the numerical simulation corresponds to approximately

of the theoretical prediction. Lyman [

13] reported that, for Bingham fluids, the experimentally observed stopping lengths range from

to

of the theoretical values. In

Figure 6, the thin dashed lines indicate this experimentally observed variability range. The result of simulation is within the variability range reported in previous experimental validations.

The result of simulation is within the experimentally observed variability range indicated by the thin dashed lines in

Figure 6.

Based on the comparison described above, these results indicate that the numerical simulations show reasonable agreement with the theoretical model for Bingham fluids. This agreement supports the validity of the simulations in capturing the stopping behavior both qualitatively and quantitatively.

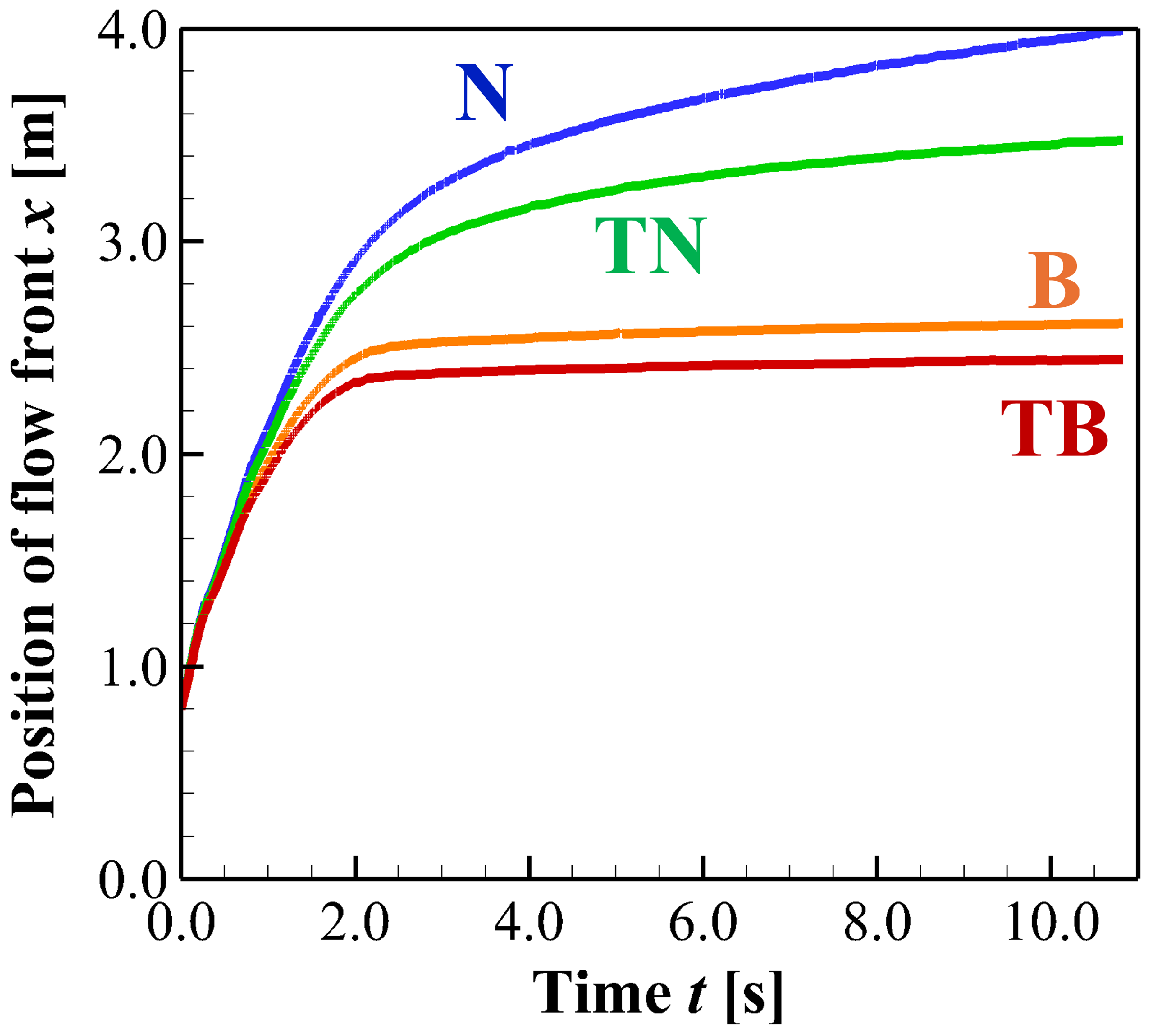

3.2. Effects of Bingham Behavior on Flow Deceleration and Distance

Figure 7 shows the time evolution of the flow front position for each condition. The blue, green, orange, and red lines correspond to the conditions

N,

TN,

B, and

TB, respectively.

As shown in

Figure 7, a clear difference is observed in the approach to the stopped state between Newtonian fluids (

N and

TN) and Bingham fluids (

B and

TB). For conditions

N and

TN, the flow velocity decreases gradually. In contrast, for conditions

B and

TB, the flow undergoes a rapid decrease in velocity before reaching the stopped state.

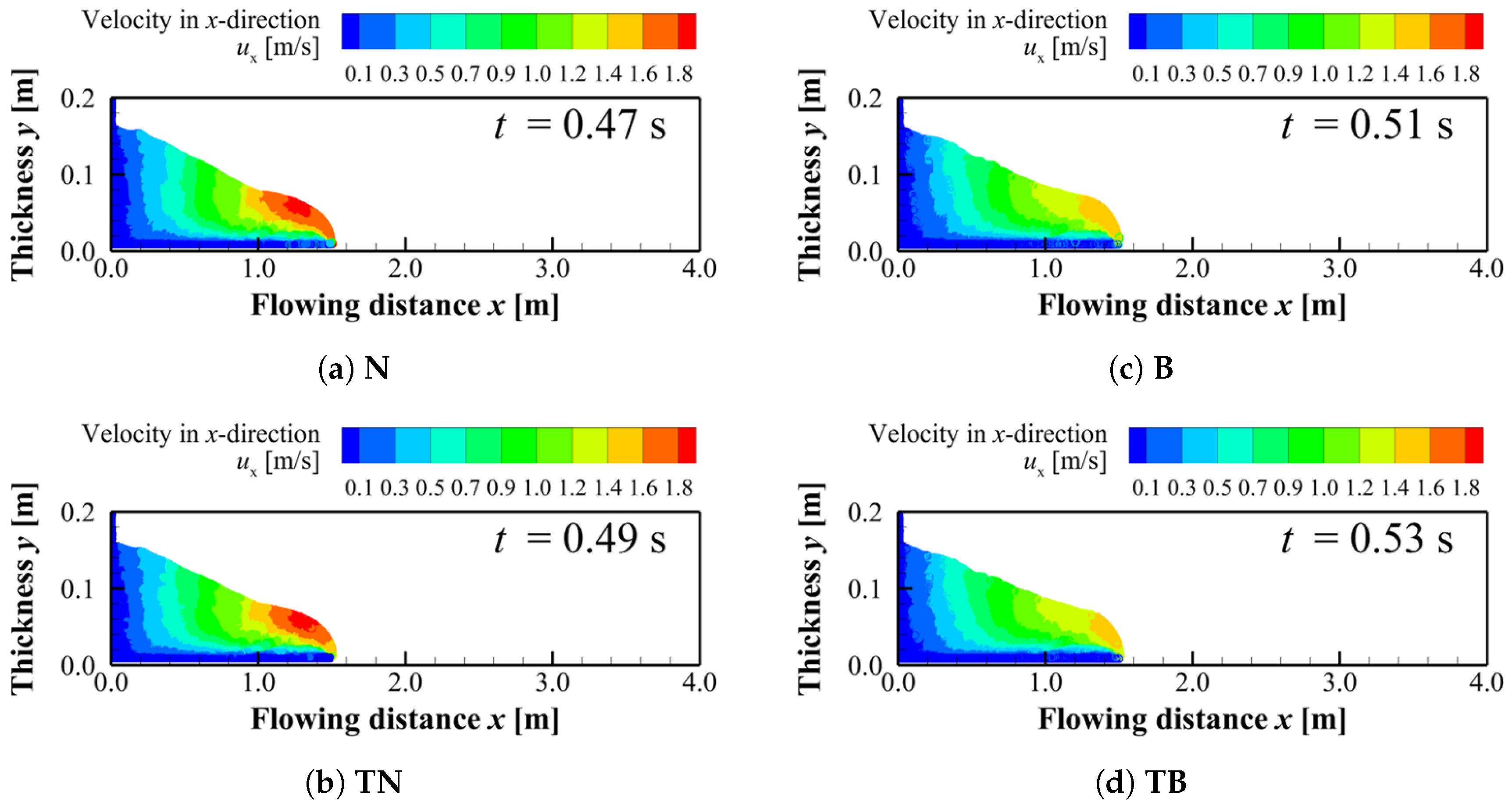

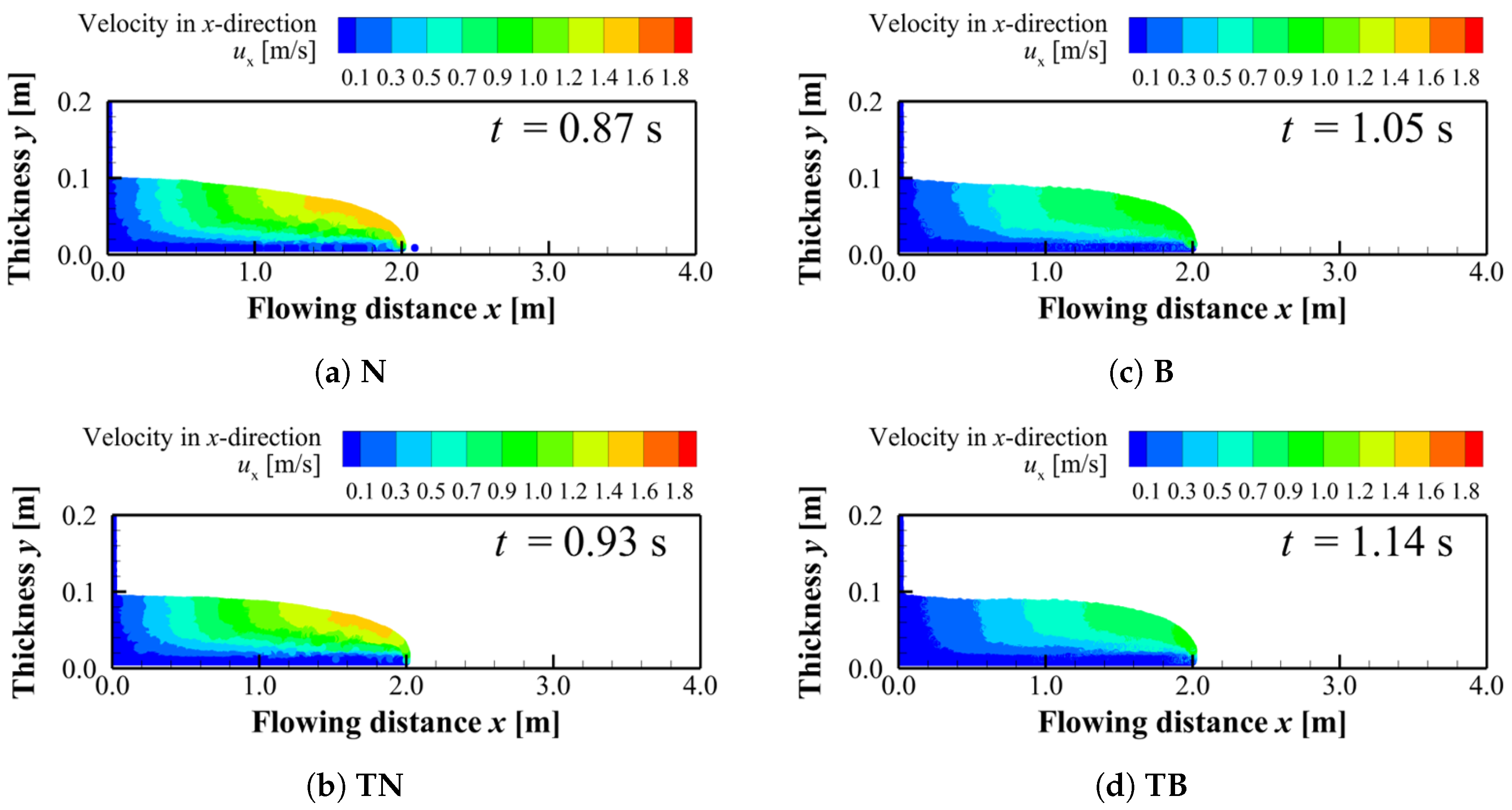

Figure 8 shows the velocity distributions in the

x-direction for each condition when the flow front reaches

. It should be noted that the aspect ratio is changed for visibility in the figures. A difference is observed in the spatial extent of the region with velocities higher than

between Newtonian fluids (conditions

N and

TN) and Bingham fluids (conditions

B and

TB). On the other hand, no significant difference is found in this high-velocity region between the two Newtonian conditions (

N and

TN). A similar result is obtained between the two Bingham conditions (

B and

TB).

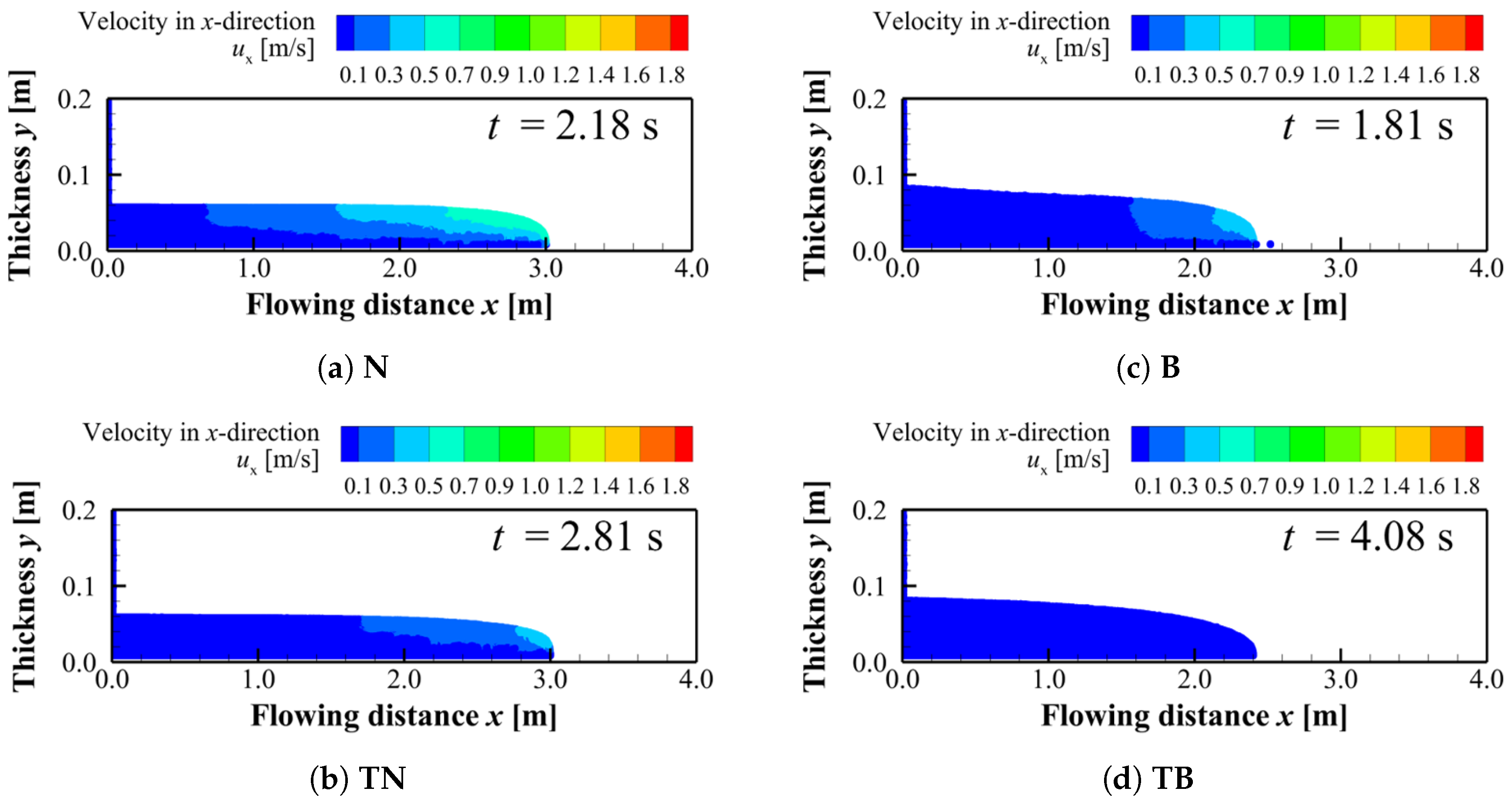

Figure 9 shows the velocity distributions in the

x-direction for each condition when the flow front reaches

. The Bingham fluids (

Figure 9 and

Figure 9) exhibit lower velocities than the Newtonian fluids (

Figure 9 and

Figure 9). The region with velocities higher than

disappears in the Bingham conditions.

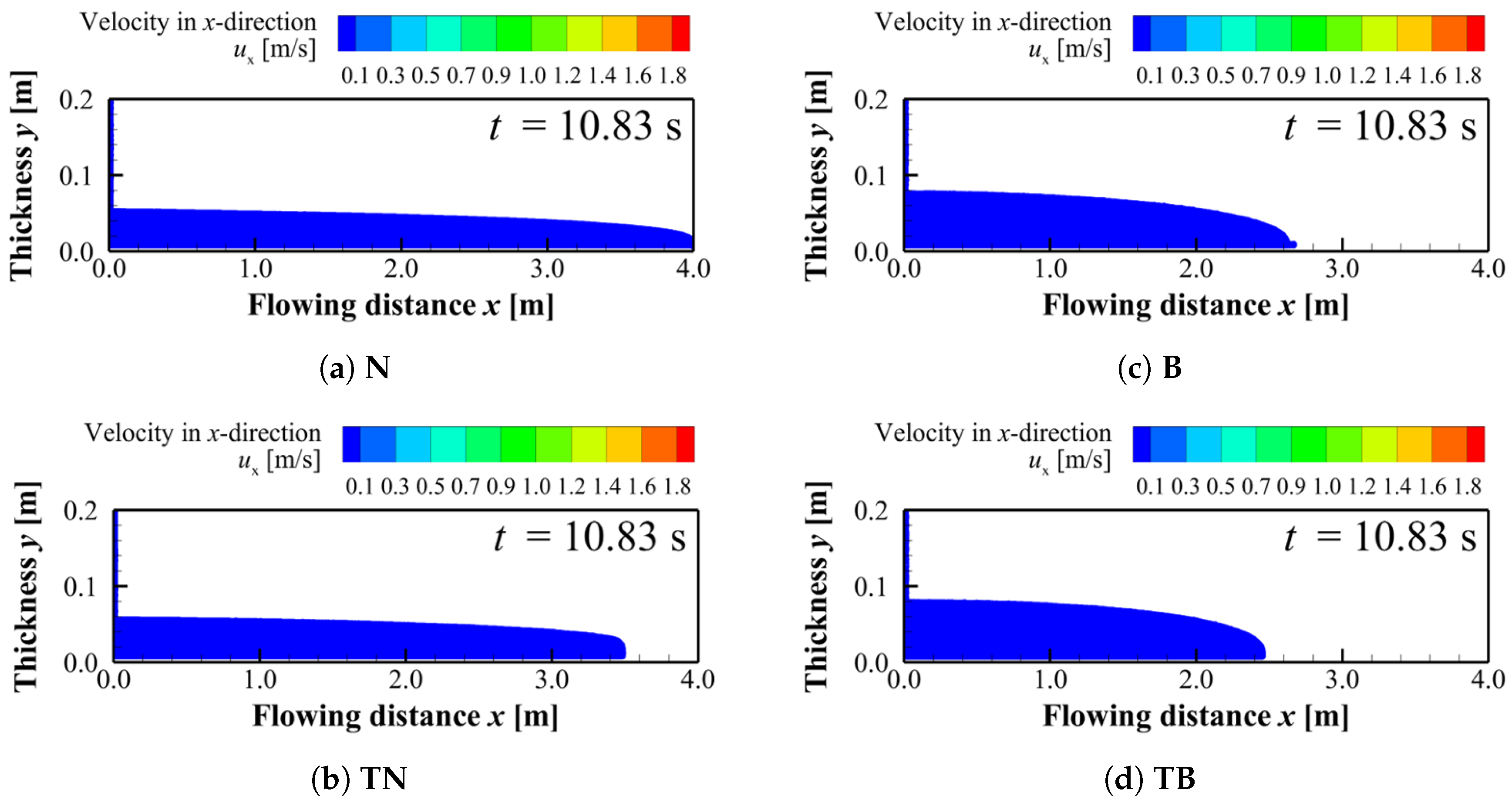

Figure 10 shows the velocity distributions in the

x-direction for each condition when the flow front reaches

for Newtonian conditions (

N and

TN) and

for Bingham conditions (

B and

TB). In addition,

Figure 11 shows the velocity distributions at

when the flow under condition

N reaches the domain boundary. A comparison between

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 for condition

TB shows that the flow front exhibits almost no further displacement. This observation allows the Bingham flows under condition

TB to be regarded as stopped at the final stage. In particular, as shown in

Figure 10, the flow under condition

TB has already lost most of its velocity at

.

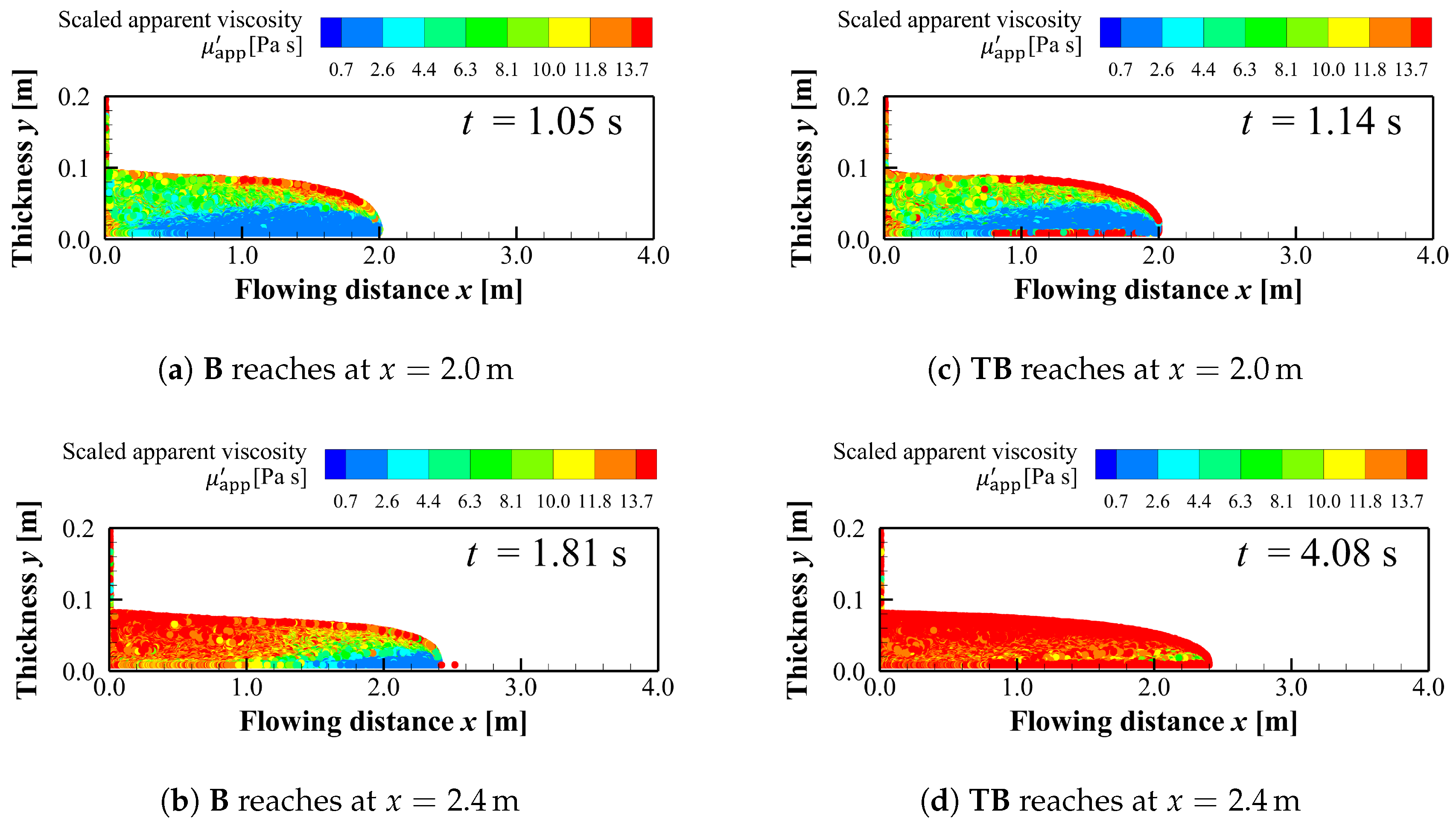

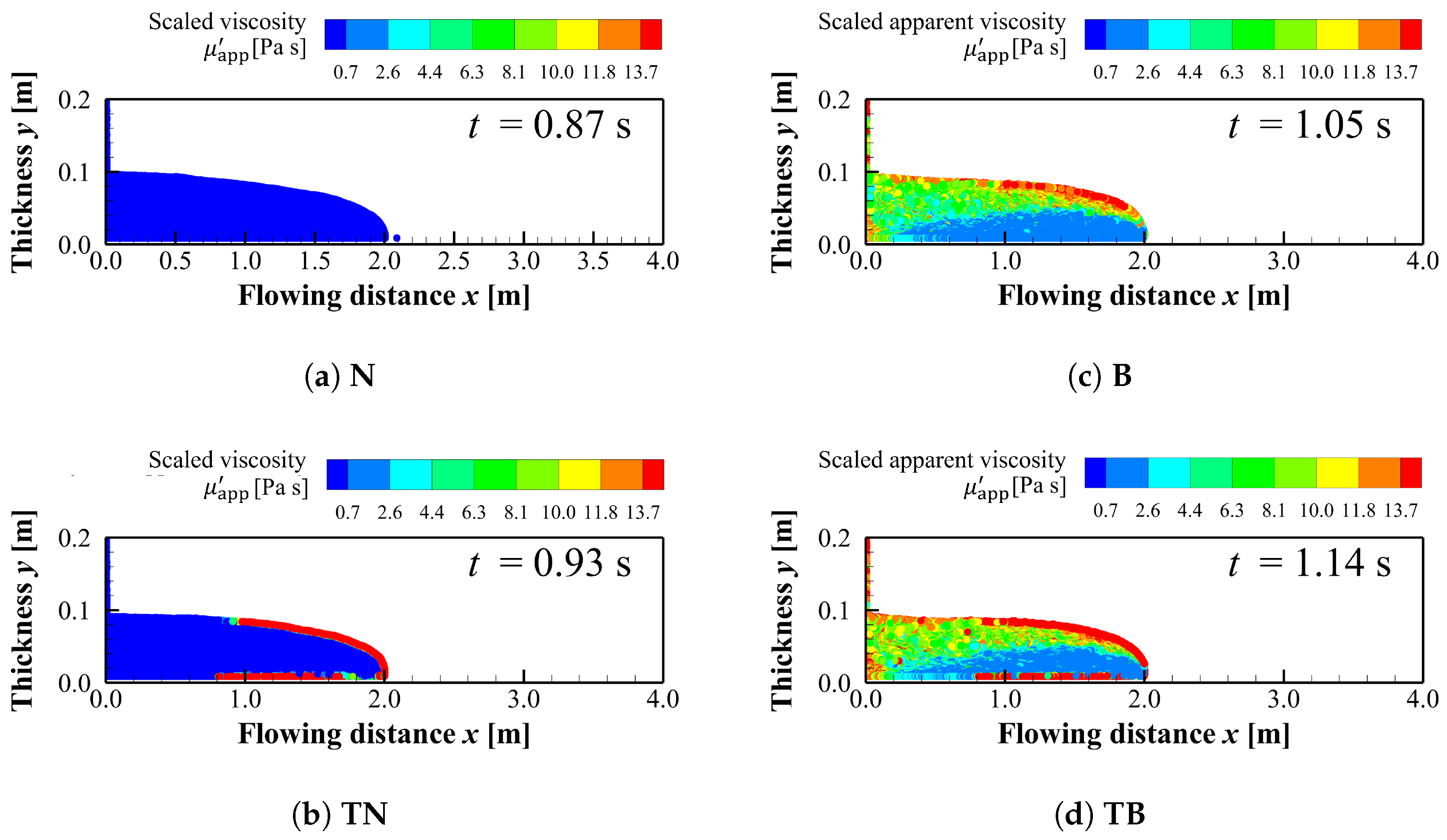

Figure 12 shows the apparent viscosity distributions for conditions

B and

TB when the flow reaches at

and

. Here, the apparent viscosity distribution under condition

TB at

(

Figure 12) is compared with that at

(

Figure 12), where the flow is still advancing. This comparison shows that the apparent viscosity increases over the entire flow region during this time. A similar comparison is conducted for condition

B. The apparent viscosity distribution at

(

Figure 12) is compared with that at

(

Figure 12). The increase in the apparent viscosity is found to start from the upstream region.

Figure 12 and

Figure 12 are compared with the velocity distributions at the same times (

Figure 9 and

Figure 10). The upstream region exhibits lower velocities than the downstream region. This observation indicates that the apparent viscosity increases in regions where the flow velocity decreases.

Therefore, a feedback process within the Bingham fluid model is suggested. A decrease in flow velocity reduces the velocity gradient. This reduction leads to an increase in the apparent viscosity. The increased apparent viscosity further decreases the flow velocity. The repetition of this process can cause a rapid decrease in velocity and eventually lead to a stopping of the flow.

Through this feedback process, the simulation captures behavior that is consistent with the characteristics of a Bingham fluid. In actual Bingham fluids, a decrease in the velocity gradient causes the shear stress to fall below the yield stress. As a result, the fluid exhibits solid-like behavior.

In this simulation, the Bingham fluid behavior was confirmed to have an influence on the flow deceleration and on the flowing distance. These results are consistent with the understanding [

24] that non-Newtonian fluid models are required for accurate prediction of lava flow behavior.

3.3. Effects of Skin Formation on Flow Deceleration and Distance

As shown in

Figure 7, the time evolution of the flow front position indicates that conditions

N and

TN exhibit similar gradual deceleration trends. However, at the same elapsed time for both conditions, condition

TN exhibits a shorter flowing distance than condition

N. This difference in flowing distance is found to increase as time progresses.

Similarly, conditions B and TB exhibit similar abrupt deceleration trends. However, at the same elapsed time for both conditions, condition TB exhibits a shorter flowing distance than condition B. As a result, the final stopping distance under condition TB is smaller than that under condition B.

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 show the velocity distributions in the

x-direction for four conditions. First, the velocity distributions of the two Newtonian fluids under conditions

N and

TN are compared. When the flow front reaches

(

Figure 8 and

Figure 8), the velocity distributions under conditions

N and

TN are similar. When the flow front reaches

(

Figure 9 and

Figure 9), the spatial extent of the region with velocities between

and

is smaller under condition

TN than under condition

N. When the flow front reaches

(

Figure 10 and

Figure 10), the difference in velocity between conditions

N and

TN becomes more pronounced.

Similarly, the velocity distributions of the two Bingham fluids under conditions

B and

TB are compared. When the flow front reaches

(

Figure 8 and

Figure 8), the velocity distributions under conditions

B and

TB are similar, as in the Newtonian conditions. When the flow front reaches

(

Figure 9 and

Figure 9), the velocity under condition

TB is lower overall than that under condition

B. When the flow front reaches

(

Figure 10 and

Figure 10), the flow under condition

TB has lost most of its velocity, and the front position shows almost no further change, even at

(

Figure 11). On the other hand, at

(

Figure 10), the flow under condition

B continues to advance. At

, the front position under condition

B (

Figure 11) is located further downstream than that under condition

TB (

Figure 11).

Figure 13 shows the apparent viscosity distributions at the time when flows reach at

for each condition. Under the temperature-dependent conditions

TN (

Figure 13) and

TB (

Figure 13), a high-viscosity region with

is observed at the flow surface.

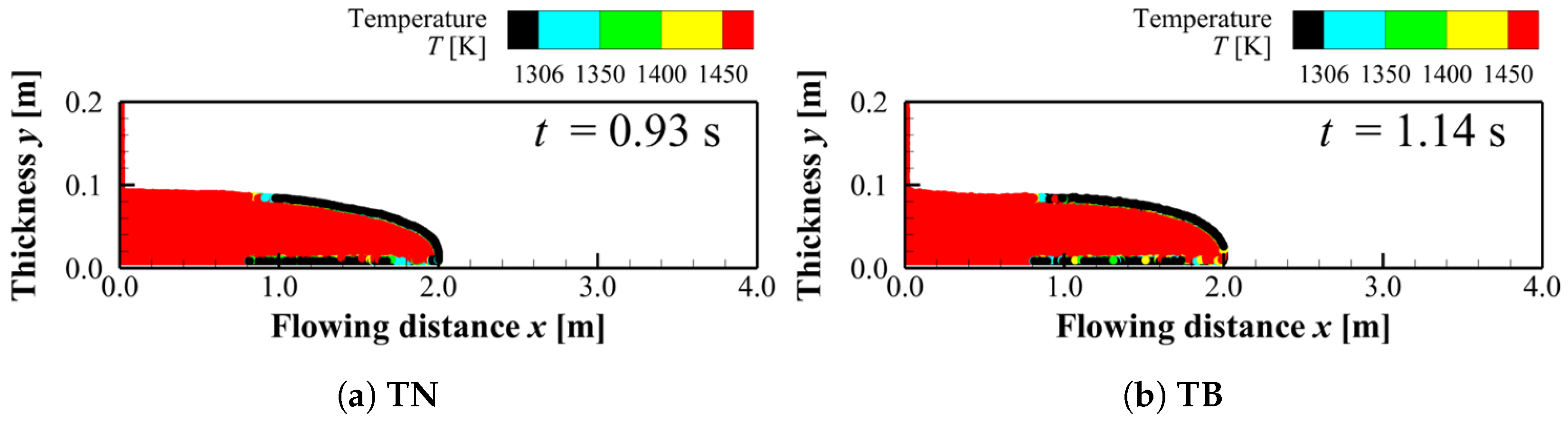

Figure 14 shows the temperature distributions at the time when flows reach at

for conditions

TN and

TB. A comparison between

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 indicates that this surface region satisfies

and

. A similar relationship between the apparent viscosity (

Figure 13) and temperature (

Figure 14) is also observed in the condition

TB. This result shows that the surface layer is represented as a low-temperature, high-viscosity skin.

Figure 13 for condition

N and

Figure 13 for condition

TN show that the scaled viscosity

inside the flow is mostly lower than

. This observation indicates that cooling-induced skin formation occurs only at the flow surface.

Similarly,

Figure 13 for condition

B and

Figure 13 for condition

TB show comparable viscosity distributions inside the flow. This result indicates that skin formation due to cooling is confined to the flow surface, even for the Bingham fluid conditions.

On the other hand,

Figure 12 and

Figure 12 show the apparent viscosity distributions when the flow fronts reach

. At this stage,

Figure 12 and

Figure 12 indicate that the apparent viscosity inside the flow is overall higher under condition

TB than under condition

B. This result suggests that the velocity reduction process associated with Bingham behavior occurs at a shorter flowing distance under condition

TB than under condition

B.

From the above comparisons of the velocity distributions and the time evolution of the flow front positions, the effects of the surface skin are examined for both the Newtonian conditions (

N and

TN) and the Bingham conditions (

B and

TB). These results indicate that the cooling-induced surface skin suppresses the flow and reduces the flow velocity. This interpretation is consistent with qualitative observations of lava flows. In such flows, a plastically deformable surface skin formed at the flow surface retains the internal lava near the flow front [

3].

Under condition TN, the suppression of the flow by the surface skin causes the flow to exhibit longer arrival times at corresponding positions than under condition N. Similarly, under condition TB, the surface skin causes the Bingham related velocity reduction to occur at a shorter flowing distance than under condition B. As a result, this behavior leads to a difference in the final stopping position of the flow.

These results suggest that surface skin formation plays a role in the flow characteristics of lava flows, and that accurate simulation of lava flow behavior requires viscosity models that appropriately account for both non-Newtonian behavior and skin formation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.T.; Methodology, S.T.; software, S.T., H.K.; validation, S.T.; formal Analysis, S.T., T.S., S.M., J.Y., M.S. (Makoto Sugimoto), H.K. and M.S. (Masaya Shigeta); investigation, S.T.; discussion, S.T., T.S., S.M., J.Y., M.S. (Makoto Sugimoto), H.K. and M.S. (Masaya Shigeta); writing—original draft preparation, S.T.; writing—review and editing, J.Y., M.S.(Makoto Sugimoto), H.K. and M.S. (Masaya Shigeta); visualization, S.T.; supervision, M.S. (Masaya Shigeta); project administration, M.S. (Masaya Shigeta); resources, M.S.(Makoto Sugimoto), M.S. (Masaya Shigeta); funding acquisition, M.S. (Masaya Shigeta). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

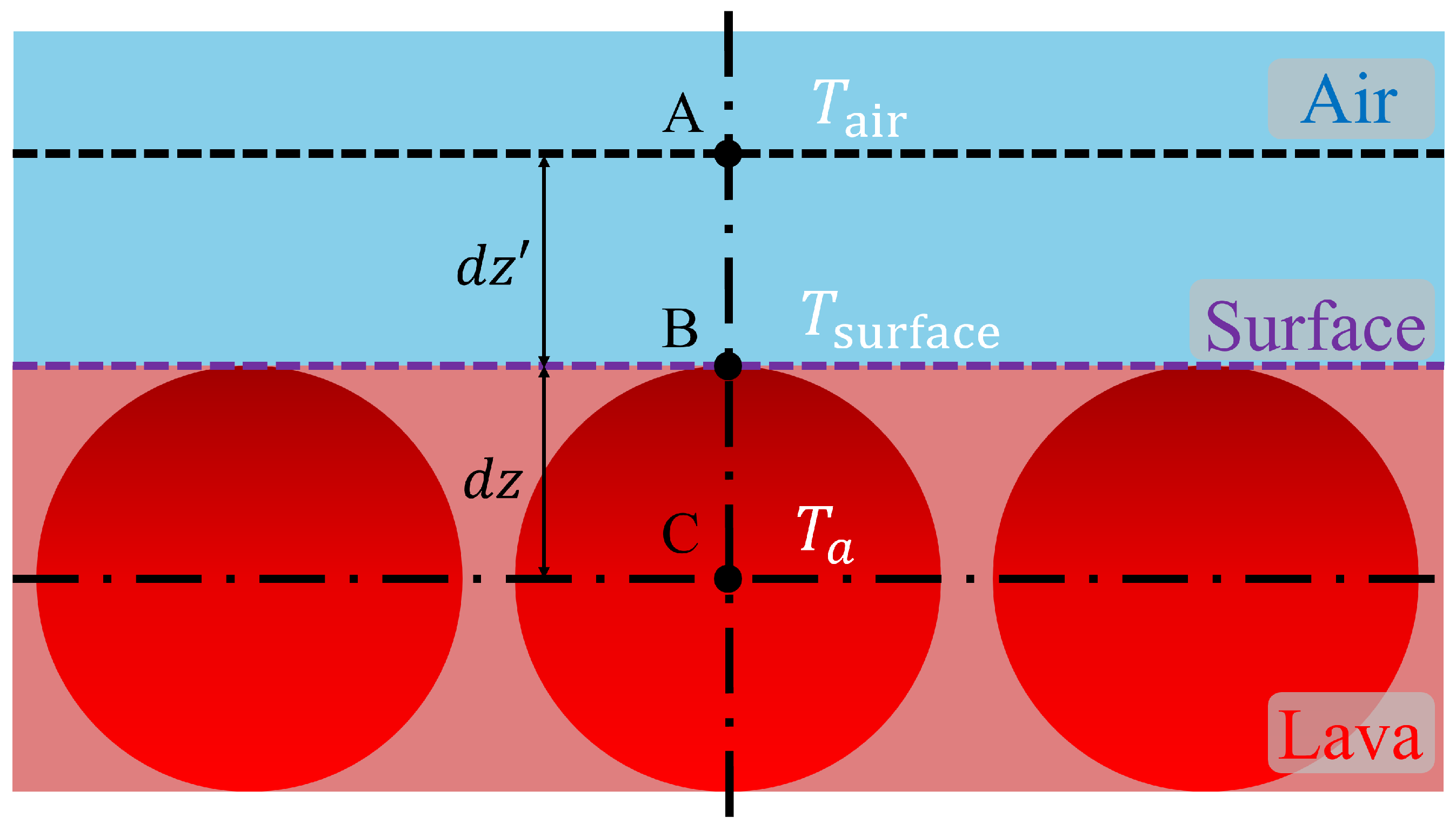

Figure 1.

Conceptual diagram of heat flux ambient air employed in the formulation.

Figure 1.

Conceptual diagram of heat flux ambient air employed in the formulation.

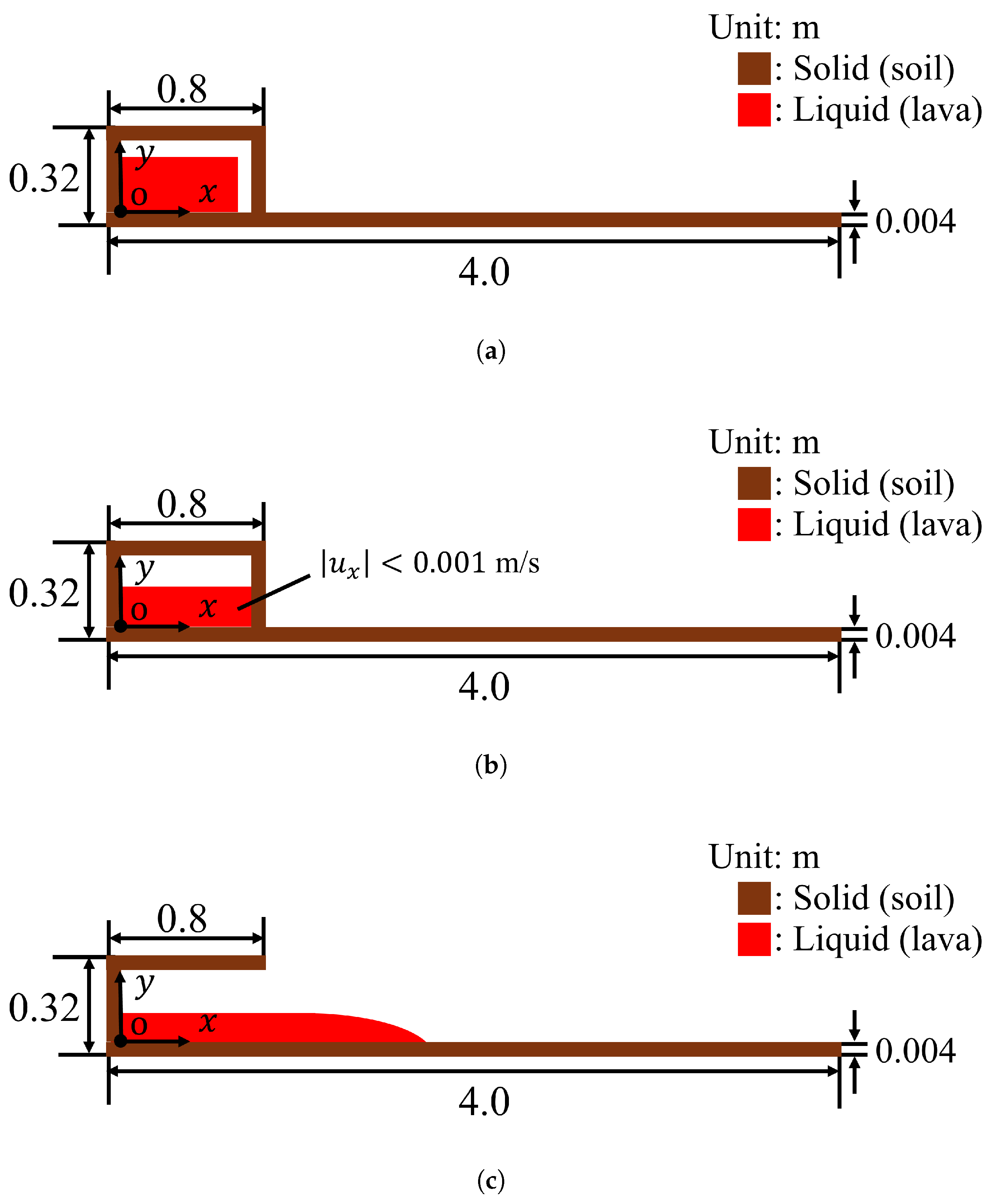

Figure 2.

Computational domain: (a) before the dam-break simulation, (b) at initial condition of lava flow simulation, and (c) after the wall is removed. Brown area represents solid particles, and red area denotes liquid particles.

Figure 2.

Computational domain: (a) before the dam-break simulation, (b) at initial condition of lava flow simulation, and (c) after the wall is removed. Brown area represents solid particles, and red area denotes liquid particles.

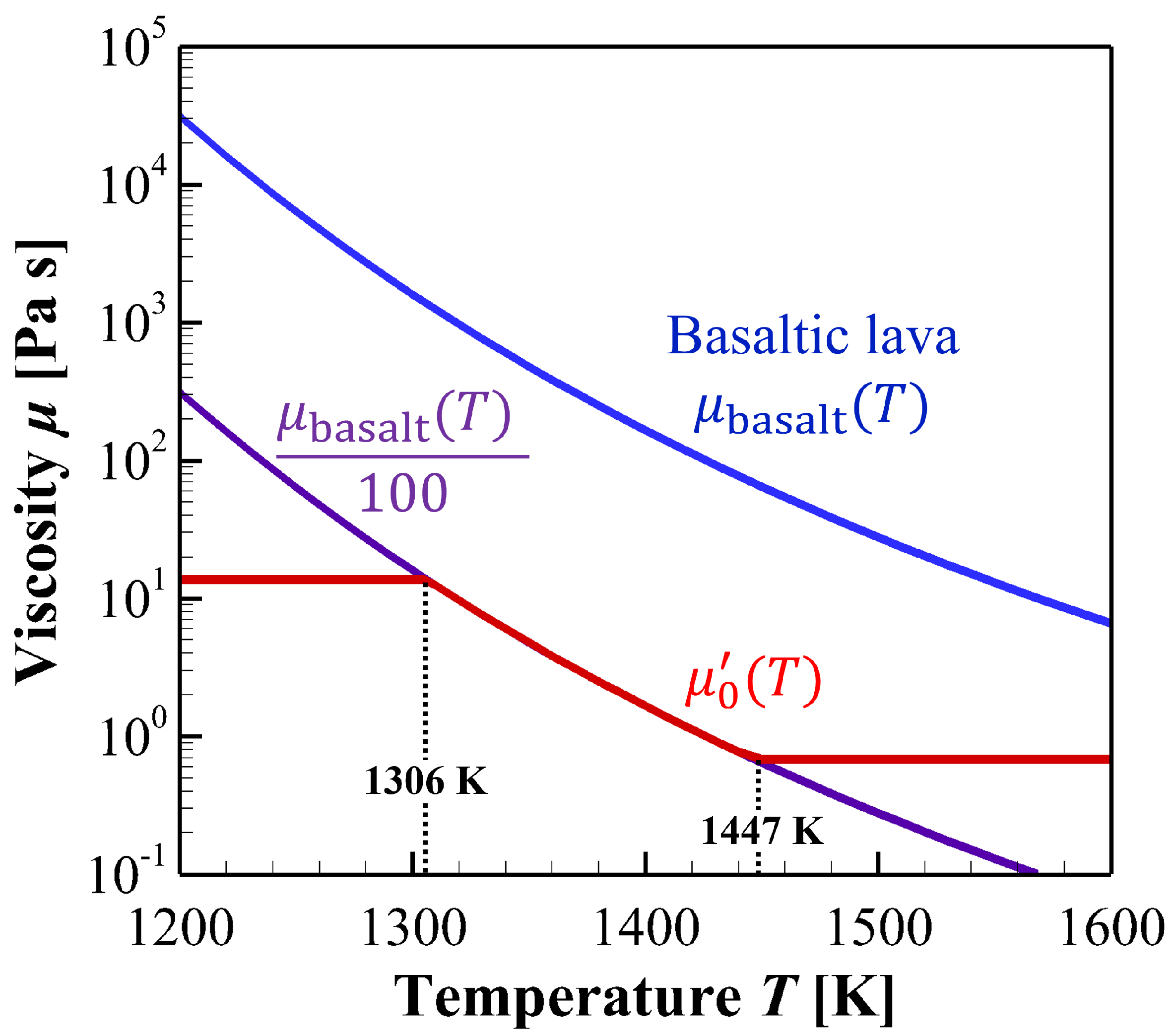

Figure 3.

Temperature dependency of viscosity. The blue curve represents the viscosity of basaltic lava, . The purple curve shows the scaled viscosity, . The red curve, , denotes the temperature-dependent viscosity applied in the simulations with limited range.

Figure 3.

Temperature dependency of viscosity. The blue curve represents the viscosity of basaltic lava, . The purple curve shows the scaled viscosity, . The red curve, , denotes the temperature-dependent viscosity applied in the simulations with limited range.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the simulated flow length (condition

N) with the theoretical scaling proposed by Huppert [

26]. The solid line represents the simulation result, and the dashed line denotes the theoretical solution.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the simulated flow length (condition

N) with the theoretical scaling proposed by Huppert [

26]. The solid line represents the simulation result, and the dashed line denotes the theoretical solution.

Figure 5.

Temporal evolution of the relative change of the compensated quantity . The vertical axis represents the relative change between consecutive time steps, defined as . The time interval between successive data points is .

Figure 5.

Temporal evolution of the relative change of the compensated quantity . The vertical axis represents the relative change between consecutive time steps, defined as . The time interval between successive data points is .

Figure 6.

Temporal evolution of the flow front position obtained from the numerical simulation for condition

B. The solid line represents the simulation result. The thick dashed line indicates the theoretical stopping position predicted by Lyman [

13]. The thin dashed lines represent the experimentally observed variability range of the stopping lengths, corresponding to 79–93% of the theoretical prediction.

Figure 6.

Temporal evolution of the flow front position obtained from the numerical simulation for condition

B. The solid line represents the simulation result. The thick dashed line indicates the theoretical stopping position predicted by Lyman [

13]. The thin dashed lines represent the experimentally observed variability range of the stopping lengths, corresponding to 79–93% of the theoretical prediction.

Figure 7.

Time evolution of the flow front position for each condition. The blue, green, orange, and red lines correspond to the conditions N, TN, B, and TB, respectively.

Figure 7.

Time evolution of the flow front position for each condition. The blue, green, orange, and red lines correspond to the conditions N, TN, B, and TB, respectively.

Figure 8.

x-directional velocity distributions when the flow front reaches at : (a) N, (b) TN, (c) B and (d) TB.

Figure 8.

x-directional velocity distributions when the flow front reaches at : (a) N, (b) TN, (c) B and (d) TB.

Figure 9.

x-directional velocity distributions when the flow front reaches at : (a) N, (b) TN, (c) B and (d) TB.

Figure 9.

x-directional velocity distributions when the flow front reaches at : (a) N, (b) TN, (c) B and (d) TB.

Figure 10.

x-directional velocity distribution when the flow front reaches at for N and TN and at for B and TB: (a) N, (b) TN (), (c) B and (d) TB ().

Figure 10.

x-directional velocity distribution when the flow front reaches at for N and TN and at for B and TB: (a) N, (b) TN (), (c) B and (d) TB ().

Figure 11.

x-directional velocity distribution at (when the flow front of condition N reaches the domain boundary): (a) N, (b) TN, (c) B and (d) TB.

Figure 11.

x-directional velocity distribution at (when the flow front of condition N reaches the domain boundary): (a) N, (b) TN, (c) B and (d) TB.

Figure 12.

Viscosity distributions for B and TB: (a) at the time B reaches at , (b) at the time B reaches at , (c) at the time TB reaches at and (d) at the time TB reaches at ,

Figure 12.

Viscosity distributions for B and TB: (a) at the time B reaches at , (b) at the time B reaches at , (c) at the time TB reaches at and (d) at the time TB reaches at ,

Figure 13.

Viscosity distributions at the time when the flow fronts reach

: (

a)

N, (

b)

TN, (

c)

B (reprinted from

Figure 12), (

d)

TB (reprinted from

Figure 12).

Figure 13.

Viscosity distributions at the time when the flow fronts reach

: (

a)

N, (

b)

TN, (

c)

B (reprinted from

Figure 12), (

d)

TB (reprinted from

Figure 12).

Figure 14.

Temperature distribution at the time when the flow fronts reach : (a) TN, (b) TB.

Figure 14.

Temperature distribution at the time when the flow fronts reach : (a) TN, (b) TB.

Table 1.

Computational conditions.

Table 1.

Computational conditions.

| Parameter |

Value |

Unit |

| Dimension number

|

2 |

- |

| Diameter of computational particle H

|

|

|

| Time step

|

|

|

| Gravitational acceleration g

|

|

|

| Thermal conductivity of soil

|

|

|

| Specific heat of soil

|

|

|

| Density of soil

|

|

|

| Temperature of air

|

300 |

|

| Thermal conductivity of air

|

|

|

| Distance from surface particles to air

|

|

|

Table 2.

Physical properties of basaltic lava.

Table 2.

Physical properties of basaltic lava.

| Property |

Value |

Unit |

| Density

|

|

|

| Scaled apparent viscosity

|

–

|

|

| Fitting parameter for viscosity model

|

|

- |

| Yield stress

|

|

|

| Thermal conductivity

|

–

|

|

| Specific heat at constant pressure

|

–

|

|

| Emissivity

|

|

- |