1. Introduction

A mitigation strategy to reduce potentially harmful exposure to vibration and shocks is the use of suspension seats in vehicles that expose the operator/driver to whole-body vibration (WBV) exposure. A dedicated industry has engineered advanced, tailor-made passive and active suspension seats for applications in trucks, buses, off-road vehicles, rail transport, cranes, as well as construction and maintenance-of-way vehicles. Vehicles may be equipped with suspension seats by vehicle manufacturers or retrofitted to replace old seats by vehicle owner/user, but a mismatch and design errors may contribute to increased vibration exposure to the operator. Ideally, the seat should be matched to the vehicle characteristics, operator/driver tasks, provide ergonomic features and adjustments as well as driver comfort while attenuating safely input vibration and shocks. The seat should be designed to the lowest technically achievable vibration transfer considering the dominant frequency of the vehicle. This sentinel health event investigation was related to a Federal Employers Liability Act (FELA) injury claim of a maintenance-of-way tamper operator who suffered from a lower back disorder. An occupational sentinel health event refers to a disease, disability, or untimely death that is associated with workplace exposures. The occurrence of such an event may prompt epidemiological or industrial hygiene investigations and can provide valuable information for enhancing engineering controls and personal protective measures [

1,

2,

3]. The worker reported that the seat in a tamper railroad machine was causing discomfort, pain and harm and claimed that the seat was defective. A tamping machine or ballast tamper is a self-powered rail vehicle designed to accurately adjust the position of railway tracks. It does this by using mechanized tines to lift ties and align the track. These machines use hydraulic and mechanical processes to pack and align ballast using vibration under railway tracks to provide stability and safe, reliable train operations. The tamping machine work cycles include the tamping of ties, leveling of track, correcting horizontal alignment, and packing of ballast in a single pass all controlled by the operator and the automated programmable logic controllers.

2. Materials and Methods

Detailed whole-body vibration (WBV) exposure measurements were conducted according to current applicable technical standards and guidelines (i.e., ISO 2631-1; 1997, ANSI and ACGIH, etc.) on a 09-16 DYNACAT Continuous Action Tamper with Stabilizer (built by Plasser American Corp. in 2001, rebuilt 2015, Serial No. 3155; weight approximately 70 tons) operated by a Class I railroad in the USA during track repair service, using vibration measurement equipment to assess occupational exposure and potential health risks. WBV measurements were conducted during the night in Texas, USA as part of a FELA claim investigation. The tested operator seat of the tamper was evaluated for ergonomic features (i.e., adjustability, posture, and suspension quality). The operator seat spring system was manufactured by Grammer, Mfg. (Labeled: MSG85 (Inventory 1237860/Order DE115978360019/assembly 2014/32) and assembled with modifications by J.R. Merrit Controls, Inc. (Labeled: Part No LRC100-14649 Job No 69894, SF32516 1/21/2015, Serial No. 11488877) to allow for one-operator control of the tamper. The Grammer seat had a vertical and longitudinal shock absorber as well as a weight adjustment spring suspension system. The rotating seat had weight, height, for-after adjustments for the operator, a reclining backrest, headrest and on the left- and right-side consoles with adjustable rests, switches, knobs, handles and four monitors on both sides (see

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). The consoles and monitors were attached between the suspension system and seat pad and back rest (see

Figure 3). The operator has a seat height, fore/after adjustment. The vibration was measured utilizing the Svantek SV106 Human Vibration Meter & Analyzer (compliant with ISO 2631-1, ISO/EN 8041) serial No 46292, seat accelerometer: Svantek SV 38A, serial No 43850 and for the floor accelerometer: Svantek SV151, serial No 31377. Vehicle speed and location was monitored with a Garmin GPSMap 67i device. The railroad and operator consented to the measurement and audio-visual monitoring during a routine work cycle. The measuring devices and system were calibrated and checked to Svantek calibration factory conformity (Available upon request). The collected data (02/2025) was analyzed with the Svantek SvanPC++ software 3.5.2 (2025) in accordance with ISO 2631-1 (1997).

3. Results

The railway tamping machine used pick-shaped tines that moved in a vibrating motion and are powered by hydraulics that caused various vibration intensity. As it travels along the track, these tines repeatedly pressed into the ballast, compacting and tightening the balast stones beneath the ties through dynamic vibration while exposing the operator to WBV. The vibration measurements on the rotating pedestal and seat pad were done during the entire work cycles of the machine operator including moving to the work location, set-up of the machine operation, tamping and other routine work procedures. A total of 2 h of tamping data was recorded for this analysis. Data was evaluated using measurement segments of 15 min periods from the data logger files in the SVAN PC++ software, results are reported below (Table 1). Due to the multi-axis vibration exposure to the machine operator, the vector sum is likely a better expression of the seat vibrations. The average moving speed during tamping was 2.7 mph, with a maximum speed of 12 mph (moving to work location). The vibrations and shocks in the horizontal and vertical axis are explained by the forces and shocks from the tamping of ties and rail track, rhythmic machine travels, repetitive quick forward accelerations, braking maneuvers and the excessive wobble of the seat (loose/worn joints/bearing).

In the worst-case situation, the European directive for minimum health and safety requirements (EU Directive) action limit of 0.5 m/s

2 was exceeded using the vector sum result [

4]. Overall, the vibration attenuation performance of the seat was inconsistent showing reduced and increased vibration transfer (SEAT) values for all axes. Some of the Crest Factors (CF) in the forward (x), lateral (y) and vertical (z) direction reached or exceeded the critical value of >9 given by ISO 2631-1 (1997). The vibration dose ratio (VDV/awT¼) was not exceeded. The basic rms vibration values for each horizontal x-, y-, and vertical z-axis, the vector sum results a

v, the Crest factor (CF), MTVV and VDV/awT¼ values are listed in the table for the overall measured time period (t=2 h). Selected work cycle segments (each t= 15 minutes) with the highest SEAT or vector sum a

v results are also listed below.

Table 2.

Vibration measurement results of the operator seat system in a tamper.

Table 2.

Vibration measurement results of the operator seat system in a tamper.

| Measurement |

Basic Rms aw (seat pad) |

Vector Sum

(m/s2) |

SEAT axis - SEAT av |

| Tamper T* |

x y z (m/s2) |

av

|

x y z av

|

| 0.23 0.05 0.35 |

0.48 |

1.7 0.92 0.87 0.94 |

| |

|

|

| Tamper T* |

Crest Factor (CF) |

MTVV |

VDV VDV/awT¼ |

| x y z |

x y z |

x y z x y z |

| 7.31 11.37 13.01 |

0.65 0.39 1.35 |

2.99 0.85 5.1 1.4 1.66 1.6 |

| |

|

|

| |

Basic rms aw (seat pad) (m/s2) |

Vector Sum |

SEAT axis - SEAT av

|

Tamper t

Section highest SEAT value** |

x y z |

av

|

x y z av

|

| 0.24 0.05 0.32 |

0.47 |

1.09 1.25 1.33 1.18 |

Tamper t

Section highest vector sum** |

|

|

x y z |

| 0.24 0.07 0.43 |

0.55 |

1.09 0.86 0.74 0.83 |

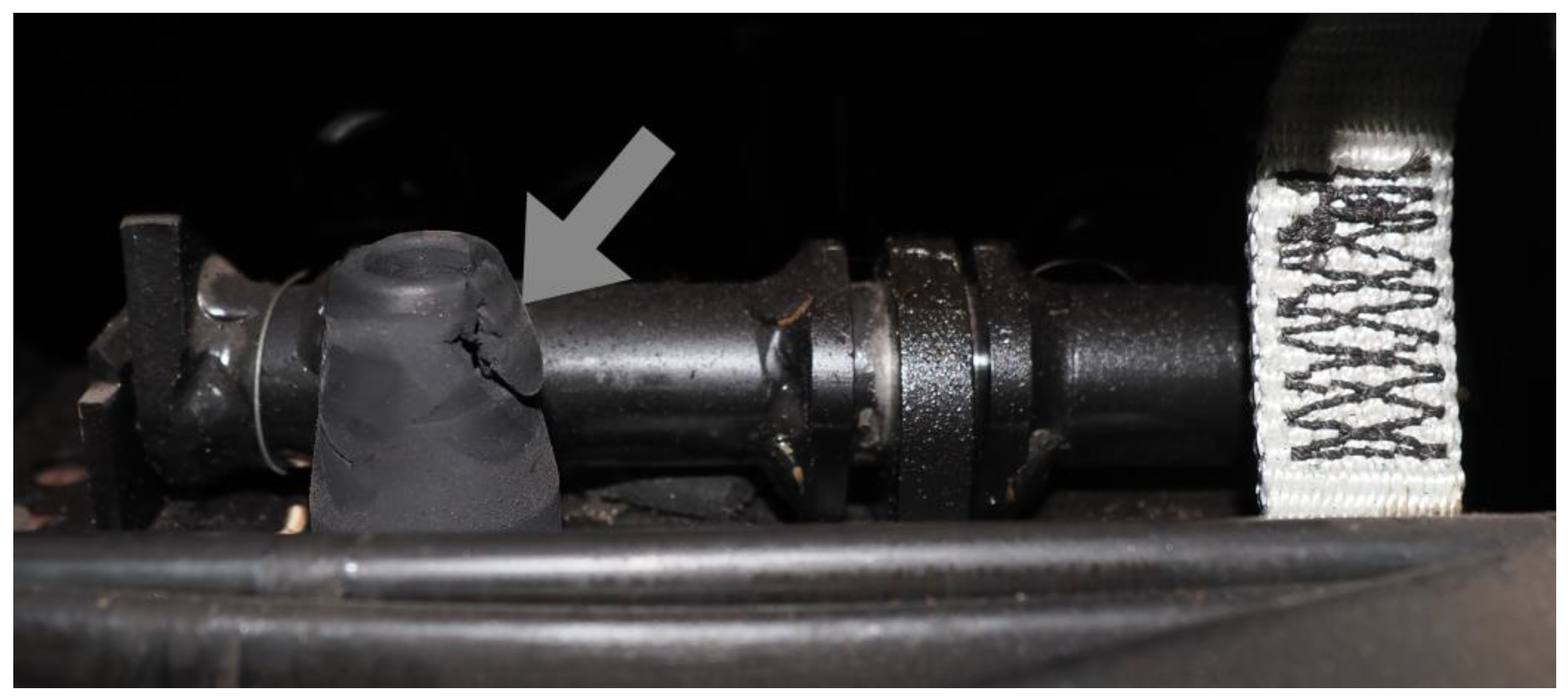

Importantly, as shown in

Figure 4., a rubber buffer located in the lower part of the seat spring system designed to control and stop excessive downward movement of the seat was broken and defective (arrow) and more likely than not renders the suspension system ineffective and unsafe in absorbing high input vibrations and shocks.

4. Discussion

Overall, the vibration measured with on the seat pad of the machine operator seat were similar and typical compared to other maintenance-of-way equipment measurements [

5]. Based on these results tamper operators should be monitored, and suitable exposure controls ought to be implemented. These include prevention measures such as medical surveillance, worker education, exposure time management and technical interventions such as undercarriage damping, suspension cabs and seat suspension [

6,

7,

8]. Early air-sprung suspension seats often amplified low-level chassis vibrations because their damping did not suit the vehicle's air suspension tuning. Adjustable seating enhances operator comfort and facilitates complex machine operation by mitigating low-frequency vibrations and sudden impacts; however, optimal performance depends on appropriate seat design, correct user adjustments, and regular maintenance. Nowadays, highly specialized seat manufacturers can provide customized seats that can reduce vibration transmission to the lowest level that can reasonably achieved. Good SEAT values in the vertical z-axis of 0.5, representing a 50% reduction, have been reported for Grammer Mfg. (series MSG95) seats without any attachments under laboratory conditions (personal communication). Poor selection of seat suspension systems can easily result in a higher vibration exposure than necessary as in this sentinel health event investigation [

9]. The seat suspension system must also be selected so that, in typical use, it is unlikely to hit its top or bottom end stops. Striking the end-stops creates shock vibrations, so increasing the risk of back injury [

6]. All seat suspension systems have a range of frequencies that they amplify. If the dominant frequencies of the vehicle vibration fall within this amplification range, the seat suspension will make the driver’s vibration exposure worse [

10]. ISO 10326 covers general seat testing, while ISO EN 7096:2000 (earthmoving), ISO EN 5007 (tractor), and EN 13490:2001 specify performance criteria for utility vehicle seats. ISO 10326-2 (2022) addresses laboratory evaluation for railway vehicles. However, under field conditions the performance of suspension seats may greatly differ from laboratory settings and active suspension seat do not necessarily provide superior performance [

11] [

12,

13,

14,

15]. [

16]. In an earlier study of a tamper machine (Hasco Mfg., Switch Tamper 6700 (ATS 9605), the vibration exposure levels were slightly higher (vector sum a

v 0.82, z=axis SEAT 0.91). The power spectral density (PSD) analysis of this Hasco tamper suspension seat indicated that the operator experienced vertical (z-axis) exposure to SEAT levels up to five times higher for frequencies below 10 Hz, coinciding with the human lumbar spine resonance range of 4 to 8 Hz [

17].

In this case investigation, the modified seat spring system of the tamper had several shortcomings. The additional attachments (control console on right and left side, the attached several monitors) added considerable weight additionally to the driver’s weight and likely caused the seat suspension system to bottom out, which in turn caused the rubber end-stops to break and exposed the operator to added shocks. The seat had excessive wobble and was not securely mounted and braced as required by the US Federal Railroad Act (FRA 49 CFR Ch. II (10–1–23 Edition) § 229.119 Cabs, floors, and passageways). The workers explained that the tamper vehicle is transported on railcars to the working locations and that the railcar vibration and handling would cause equipment inside the cab to be tossed around and bounced during transport. The added side consoles increase stress on seat joints and bearings. Engineering best practice is to mount heavy consoles and monitors separately from the seat suspension, as their weight restricts seat adjustment and adds unnecessary load.

The claimant, a longtime tamper operator, had reported at age 52 years debilitating neck and lower back disorders (spondylosis, discogenic pain, lumbar radiculopathy) consistent with the disorders shown in epidemiological and medical studies of WBV exposed workers [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. He was working for 26 years as a maintenance-of-way worker operating various specialized rail vehicles and tools [

29,

30]. He worked typically 8 to 12 hour shifts four days per week, plus overtime. He had a body weight of 90+ kg, and with that the tolerable weight tolerance of the seat was probably exceeded. Based on the overall findings and evidence it was concluded that the defective seat system was a contributing causal factor as defined by FELA. The case was settled out of court prior to this publication.

5. Study limitations

This investigation examined a single machine with a defective aftermarket seat, using vibration measurements from a track section chosen by railroad representatives. These findings may not necessarily reflect other tampers or suspension seats used in the rail industry, especially when proper inspection, repairs and maintenance are performed. Due to logistical constraints, we could not conduct a PSD analysis to identify dominant vehicle frequencies at this seat mount system; such data would aid seat engineering design and damper selection. However, a previous HASCO tamper measurements including PSD analyses provide relevant reference points [

5]. The operator's responsibilities are both varied and challenging; they must use their hands and feet to work the controls, keep an eye on the monitors, oversee the tamper as it adjusts the ties up close, and pay attention to the laser guidance system ahead and other crew members along the track. These demands cause the operator to frequently shift their upper body and head, often leaning forward and losing contact with neck and upper back supports. The height, body weight and experience/skill of other tamper operators as well as differences in track structural built may vary considerably and may modify vibration results [

31].

6. Conclusions

This investigation found that the tamper's modified seat spring system was faulty and unsafe. The aftermarket attachments increased the load, causing the suspension to bottom out and break rubber end-stops, exposing the operator to more preventable vibration and shocks. The seat also wobbled excessively and was insecurely mounted, issues that could be fixed with proper maintenance. Mounting heavy consoles and monitors apart from seat suspension avoids limiting seat adjustment and improves the SEAT performance. Effective collaboration among vehicle users, seat and vehicle engineers can reduce WBV exposure risk and improve safety and efficiency.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org, Video S1: Tamper Seating Investigation.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Acknowledgments

I want to thank Mr. Benno Goeres, Head of Seat Test Laboratory (retired), formerly: BIA/DGUV, St. Augustin, German, for his valuable input.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest. Author E.J. is US member of the ISO/TC 4 appointed by ISO Member Body ANSI (United States). E.J. has been evaluating and treating workers with WBV exposure and represented some in disability claims. He follows the Ethical Guidelines of the International Committee of Occupational Health (ICOH), American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (ACOEM), and the Association of Occupational and Environmental Clinics (AOEC) (all available online). This FELA claim case was settled out of court prior to this publication.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ANSI |

American National Standards Institute |

| CF |

Crest Factor |

| FELA |

Federal Employer Liability Act |

| FRA |

Federal Railroad Act (or Administration) |

| ISO |

International Standard Organization |

| MTVV |

Maximal Transient Vibration Value |

| SEAT |

Seat Effective Amplitude Transmissibility |

| VDV |

Vibration Dose Value |

| WBV |

Whole-body vibration |

References

- Mullan, R.J. and L.I. Murthy, Occupational sentinel health events: an up-dated list for physician recognition and public health surveillance. Am J Ind Med, 1991. 19(6): p. 775–99. [CrossRef]

- Rutstein, D.D., The principle of the sentinel health event and its application to the occupational diseases. Arch Environ Health, 1984. 39(3): p. 158. [CrossRef]

- Fubini, L., et al., [Not Available]. Med Lav, 2016. 107(3): p. 178–90.

- 2002/44, E.D., Directive 2002/44/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 June 2002 on the minimum health and safety requirements regarding the exposure of workers to the risks arising from physical agents (vibration). 2002, European Commision: Official Journal of the European Communities.

- Johanning, E., Vibration and shock exposure of maintenance-of-way vehicles in the railroad industry. Applied Ergonomics, 2011. 42(4): p. 555–562.

- Griffin, M.J.H., H.V.C.; Pitts, P.M.; Fischer, S.; Kaulbars, U.; Donati, P.M.; Bereton, P.F.;, Non-binding guide to good practice for implementing Directive 2002/44/EC (Vibrations at Work). 2008, Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg. p. 118.

- Donati, P.S., M; Szopa, J.; Starck, J..; Iglesias, E.G.; Senovilla, L.P.; Fischer, S.; Flaspoeler, E.; Reinert, D.; de Beeck, R.O.; , Workplace exposure to vibration in Europe: an expert review. 2008, European Agency for Safety and Health at Work: Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

- Johanning, E. and A. Turcot, Guide to the Effects of Vibration on Health—Quantitative or Qualitative Occupational Health and Safety Prevention Guidance? A Scoping Review. Vibration, 2025. 8(4): p. 63. [CrossRef]

- Conrad, L.F., et al., Selecting seats for steel industry mobile machines based on seat effective amplitude transmissibility and comfort. Work, 2014. 47(1): p. 123–36. [CrossRef]

- Sorainen, E., et al., Whole-body vibration of tractor drivers during harrowing. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J, 1998. 59(9): p. 642–4.

- Burdorf, A. and H. Zondervan, An epidemiological study of low-back pain in crane operators. Ergonomics, 1990. 33(8): p. 981–987. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. and X. Wang, A Review of Low-Frequency Active Vibration Control of Seat Suspension Systems. Applied Sciences, 2019. 9(16): p. 3326. [CrossRef]

- Blood, R.P., et al., Whole-body Vibration Exposure Intervention among Professional Bus and Truck Drivers: A Laboratory Evaluation of Seat-suspension Designs. J Occup Environ Hyg, 2015. 12(6): p. 351–62. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P.W., et al., A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Truck Seat Intervention: Part 1-Assessment of Whole Body Vibration Exposures. Ann Work Expo Health, 2018. 62(8): p. 990–999. [CrossRef]

- Davies, H.W., et al., Exposure to Whole-Body Vibration in Commercial Heavy-Truck Driving in On- and Off-Road Conditions: Effect of Seat Choice. Ann Work Expo Health, 2022. 66(1): p. 69–78. [CrossRef]

- Kia, K., et al., Evaluation of vertical and multi-axial suspension seats for reducing vertical-dominant and multi-axial whole body vibration and associated neck and low back joint torque and muscle activity. Ergonomics, 2022. 65(12): p. 1696–1710. [CrossRef]

- Johanning, E., Vibration and shock exposure of maintenance-of-way vehicles in the railroad industry. Appl Ergon, 2011. 42(4): p. 555–62. [CrossRef]

- Bovenzi, M. and C.T. Hulshof, An updated review of epidemiologic studies on the relationship between exposure to whole-body vibration and low back pain (1986-1997). Int.Arch.Occup.Environ.Health, 1999. 72(6): p. 351–365. [CrossRef]

- Bovenzi, M., M. Schust, and M. Mauro, An overview of low back pain and occupational exposures to whole-body vibration and mechanical shocks. Med Lav, 2017. 108(6): p. 419–433. [CrossRef]

- Wahlstrom, J., et al., Exposure to whole-body vibration and hospitalization due to lumbar disc herniation. Int Arch Occup Environ Health, 2018. 91(6): p. 689–694. [CrossRef]

- Johanning, E., Evaluation and management of occupational low back disorders. Am J Ind Med, 2000. 37(1): p. 94–111. [CrossRef]

- Hanumegowda, P.K. and S. Gnanasekaran, Risk factors and prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders in metropolitan bus drivers: An assessment of whole body and hand-arm transmitted vibration. Work, 2022. 71(4): p. 951–973. [CrossRef]

- Waters, T., et al., The impact of operating heavy equipment vehicles on lower back disorders. Ergonomics, 2008. 51(5): p. 602–636. [CrossRef]

- Teschke, K., et al., Whole Body Vibration and Back Disorders Among Motor Vehicle Drivers and Heavy Equipment Operators - A Review of the Scientific. 1999: Vancouver, BC.

- Seidel, H., On the relationship between whole-body vibration exposure and spinal health risk. Ind.Health, 2005. 43: p. 361–377. [CrossRef]

- Umer, W., et al., The prevalence of musculoskeletal symptoms in the construction industry: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Arch Occup Environ Health, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Przybyla, A.S., et al., Strength of the cervical spine in compression and bending. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2007. 32(15): p. 1612–20. [CrossRef]

- McBride, D., et al., Low back and neck pain in locomotive engineers exposed to whole-body vibration. Arch Environ Occup Health, 2014. 69(4): p. 207–13. [CrossRef]

- Landsbergis, P., et al., Occupational risk factors for musculoskeletal disorders among railroad maintenance-of-way workers. Am J Ind Med, 2020. 63(5): p. 402–416. [CrossRef]

- Johanning, E., M. Stillo, and P. Landsbergis, Powered-hand tools and vibration-related disorders in US-railway maintenance-of-way workers. Industrial Health, 2020. 58(6): p. 539–553. [CrossRef]

- Lynas, D. and R. Burgess-Limerick, Whole-Body Vibration Associated with Dozer Operation at an Australian Surface Coal Mine. Ann Work Expo Health, 2019. 63(8): p. 881–889. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).