1. Introduction

Dementia is a major neurocognitive disorder with a rapidly increasing global prevalence and an escalating socioeconomic burden; population aging further amplifies long-term care demands and pressures on healthcare systems [

1]. Dementia is a syndrome with heterogeneous etiologies, but Alzheimer’s disease is widely recognized as the most common underlying cause [

2]. Against this backdrop, there is growing demand for safe, accessible, and everyday-integrable non-pharmacological (or adjunctive) interventions that may complement the limitations of disease-modifying or symptomatic drug approaches [

1,

2].

From a neural-oscillation perspective, gamma-band activity has been discussed as a key mechanism supporting information exchange and cognition through coordinated neuronal communication [

3]. In Alzheimer’s disease and related cognitive impairment, converging evidence indicates alterations in network activity and oscillatory dynamics, including disruptions that implicate gamma-band function, raising the possibility that gamma dysregulation is linked to cognitive decline and may represent a plausible target for noninvasive neuromodulation [

4,

5].

In this context, 40-Hz sensory stimulation and entrainment research has expanded rapidly in recent years. Preclinical studies have shown that 40-Hz patterned stimulation can induce gamma-related responses in targeted neural circuits and may modulate Alzheimer’s disease–relevant pathology and neuroinflammatory processes in animal models [

7,

8,

9]. Multisensory paradigms (e.g., combined auditory and visual stimulation) have further been suggested to influence broader brain regions than unimodal stimulation, supporting continued investigation of 40-Hz–based approaches as a platform for probing network- and cellular-level mechanisms linked to cognition [

8,

9].

Human research on 40-Hz gamma-frequency stimulation is also accumulating. Feasibility and pilot studies in individuals with mild probable Alzheimer’s dementia have indicated that daily at-home 40-Hz sensory stimulation can be deliverable and well-tolerated, while also yielding measurable entrainment-related signals and exploratory outcomes relevant to brain structure and function [

6]. In addition, work focusing on auditory stimulation has prospectively assessed the safety and acceptability of 40-Hz amplitude-modulated auditory stimulation delivered via smartphones in healthy older adults [

10]. Qualitative research has also begun to examine how older adults with mild cognitive impairment (mild cognitive impairment, MCI) experience and appraise 40-Hz sound- and music-based interventions, explicitly foregrounding user experience, perceived burden, and acceptability-related determinants [

11].

Nevertheless, much of the 40-Hz entrainment literature has primarily emphasized either (1) experimental confirmation of changes in neurophysiological, pathological, or cognitive indicators [

6,

7,

8,

9] or (2) short-term evaluation centered on tolerability, adverse effects, and adherence [

6,

10,

11]. By contrast, implementation-oriented questions remain comparatively underdeveloped—namely, which delivery channels, everyday contexts, content designs, and interaction patterns shape real-world acceptability and sustained use. Implementation research emphasizes that acceptability should be treated as a distinct, conceptually grounded implementation outcome rather than being reduced to the absence of adverse events [

12]. Further, the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability conceptualizes acceptability as a multi-construct concept (e.g., affective attitude, burden, perceived effectiveness, ethicality, intervention coherence, opportunity costs, self-efficacy), underscoring the need to explicate user-perceived mechanisms that determine continued engagement [

13].

Soundscapes—defined as the acoustic environment as perceived and/or experienced in context—provide a naturalistic medium for designing auditory interventions at the level of “experience,” rather than as isolated tones [

14]. This framing is particularly relevant because simple 40-Hz auditory stimuli are often perceived as unpleasant when presented alone, which constitutes a practical barrier to sustained use [

11,

17]. To mitigate this barrier, prior approaches have combined 40-Hz stimulation with music or embedded 40-Hz components within musical structures (e.g., “gamma music”), reporting more favorable subjective impressions alongside robust 40-Hz auditory steady-state responses [

11,

17]. However, music-based delivery can be strongly preference-dependent and may introduce personalization and operational complexity (e.g., genre/track selection, managing repetition fatigue), as reflected in qualitative accounts of user experience and acceptability [

11]. In contrast, nature-based soundscapes have been studied as broadly restorative auditory environments, with evidence linking exposure to nature sounds to stress recovery relative to environmental noise and indicating associations between positive soundscape perceptual constructs and health-related outcomes [

15,

16]. Accordingly, soundscapes may offer a pragmatic pathway to transform 40-Hz auditory stimulation into a more context-compatible and sustainable listening experience for everyday routines [

14,

15,

16].

Importantly, waveform and signal-design choices may jointly influence both user experience and entrainment-related neural responsiveness. Comparative work manipulating auditory stimulus waveforms and listening states has reported that 40-Hz sinusoidal stimulation (relative to square-wave stimulation) can elicit stronger 40-Hz neural responses under specific conditions, highlighting a practical design trade-off space for auditory entrainment implementations [

18]. Against this background, the present study adopts a 40-Hz sine-wave implementation layered onto natural soundscapes (rather than amplitude modulation), enabling empirical examination of user-perceived acceptability and implementation considerations in a more naturalistic auditory medium.

Therefore, this qualitative exploratory study characterizes user-perceived acceptability and implementation considerations for a 40-Hz additive sine-wave–layered soundscape intervention. Distinct from prior work focusing on amplitude-modulated auditory stimulation or music-based “gamma” content, we examine a nature-based soundscape medium as a less preference-dependent delivery pathway and explicitly map findings to implementation outcomes and acceptability constructs. As an implementation-first deliverable, we translate interview evidence into actionable system-level requirements for scalable deployment (e.g., ambient playback, low-friction automation, acoustic safeguards;

Table 6), thereby specifying practical UX and delivery parameters that remain under-articulated in the 40-Hz auditory stimulation literature.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Reporting Framework

We conducted a qualitative exploratory study to examine user-perceived acceptability and implementation considerations for a 40-Hz sine-wave–integrated soundscape intervention. The study procedures and analytic outputs were documented to support transparent qualitative reporting in accordance with SRQR and COREQ [

20,

21]. To enable structured interpretation of acceptability and implementation-related findings, we used Proctor et al.’s implementation outcomes framework [

12] and the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability (TFA) [

13] to inform the interview guide and results mapping. Participants were assigned to one soundscape set (waves vs forest; between-participants) and completed a within-participant comparison of 40-Hz inclusion (40-Hz–ON vs 40-Hz–OFF) within the assigned set.

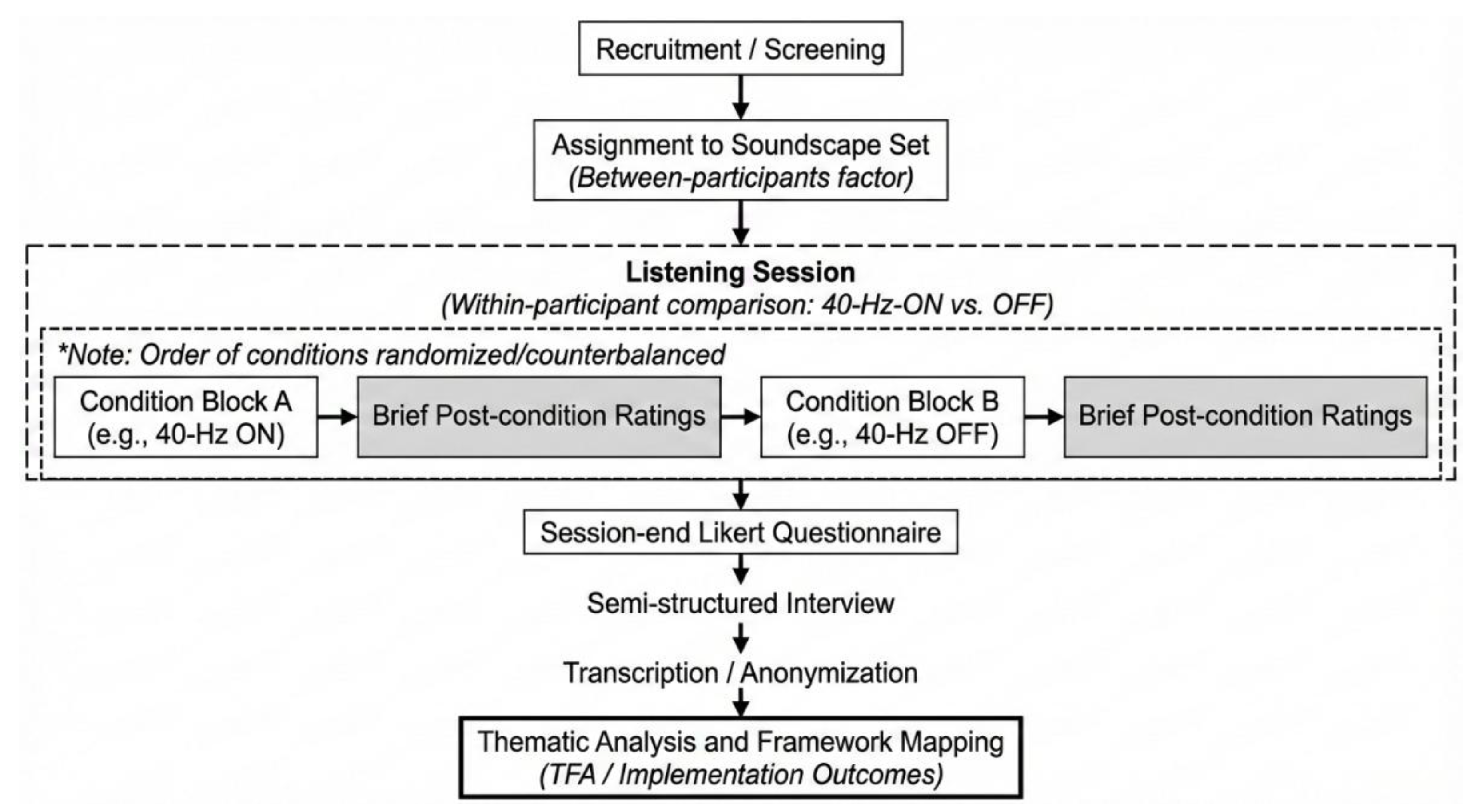

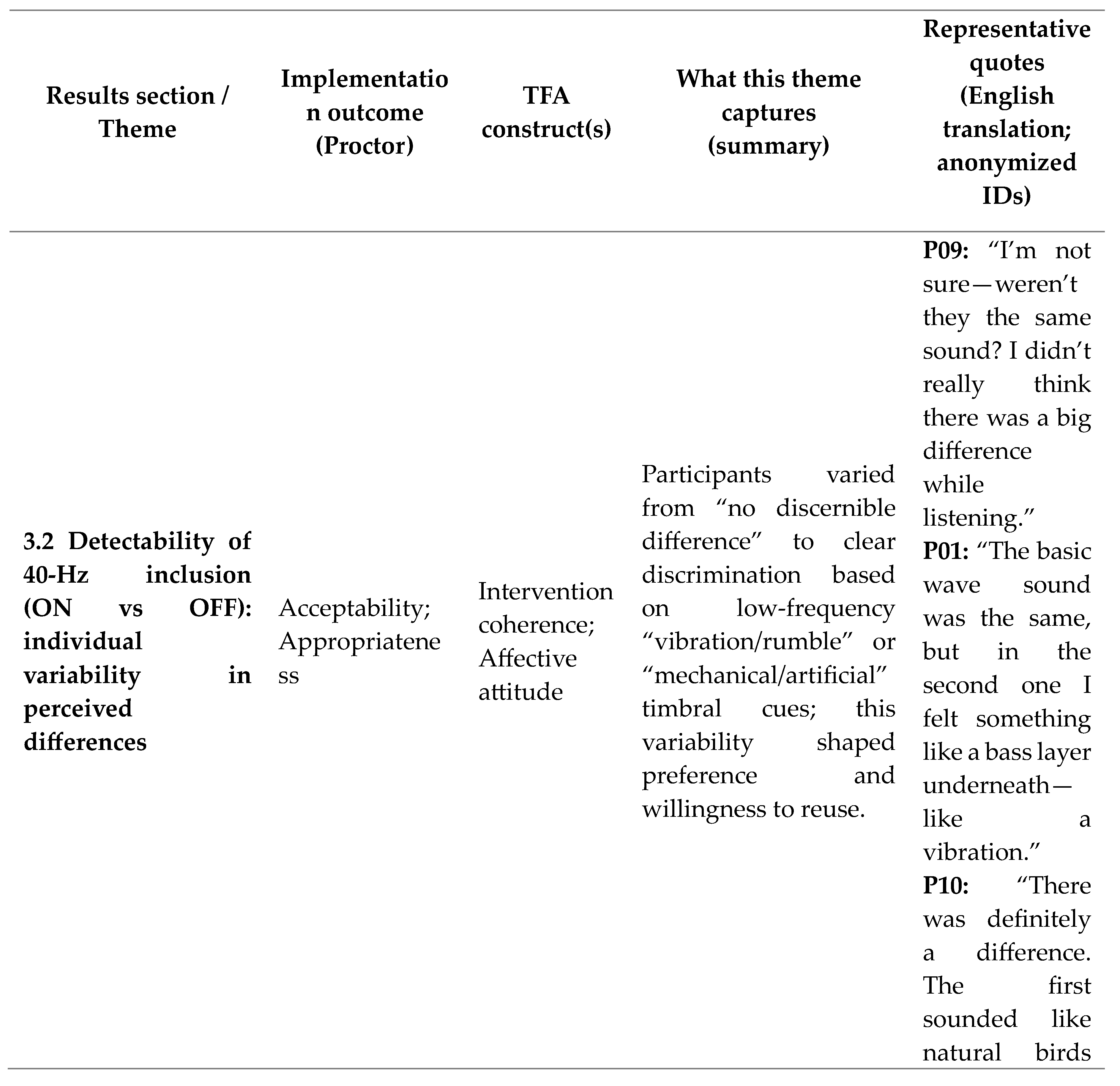

Figure 1.

Study flow and assessment timeline. Participants were recruited and screened, assigned to a soundscape set (between-participants), and completed a listening session comparing 40-Hz–ON and 40-Hz–OFF conditions within participants. After each condition, brief post-condition ratings were collected, followed by a session-end Likert questionnaire, a semi-structured interview, transcription/anonymization, and thematic analysis with framework mapping (TFA and implementation outcomes).

Figure 1.

Study flow and assessment timeline. Participants were recruited and screened, assigned to a soundscape set (between-participants), and completed a listening session comparing 40-Hz–ON and 40-Hz–OFF conditions within participants. After each condition, brief post-condition ratings were collected, followed by a session-end Likert questionnaire, a semi-structured interview, transcription/anonymization, and thematic analysis with framework mapping (TFA and implementation outcomes).

2.2. Ethics

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the investigators’ institution (IRB No. KMU-202509-HR-503). All participants provided written informed consent after receiving information about study purpose, procedures, potential discomfort, and the right to withdraw. Interviews were audio-recorded with consent, transcribed verbatim, and anonymized by removing personally identifying information.

2.3. Participants and Recruitment

Participants were recruited in Seoul, Republic of Korea, via online announcements and professional networks. Inclusion criteria were: (1) age ≥ 40 years, (2) no substantial difficulty in everyday listening, and (3) ability to complete the listening and interview procedures. Exclusion criteria were: (1) history of major neurological disorders (e.g., epilepsy), (2) conditions likely to materially affect listening experience or fatigue/discomfort, and (3) any circumstance judged by the research team to make participation inappropriate.

Eleven adults participated (middle-aged, n = 5; older adults, n = 6). Seven participants were male and four were female. Soundscape set assignment (waves vs forest) was used to diversify content exposure across participants while keeping the 40-Hz comparison within-participants. Participants were assigned anonymized identifiers (P01–P11). Condition order by participant is reported in

Table 1.

2.4. Auditory Stimuli

2.4.1. Stimulus Conditions and Structure

Two soundscape content sets were prepared: Set A (waves) and Set B (forest). Within each set, two stimulus conditions were created: a 40-Hz–OFF control (soundscape without the added 40-Hz component; A′/B′) and a 40-Hz–ON layered condition (soundscape with an added 40-Hz sine-wave component; A/B). The 40-Hz component was generated as a pure 40-Hz sine wave and additively layered onto the soundscape (i.e., not amplitude modulation). For the layered stimuli, the 40-Hz sine wave was mixed identically into the left and right channels using a consistent mixing template and routing procedure across files. Although the exact component-to-soundscape gain value was not retained as a separately logged parameter, balancing decisions followed the same production constraints for all layered files, including (i) loudness-matching targets relative to the corresponding 40-Hz–OFF masters and (ii) conservative true-peak management constraints (

Table 2), thereby maintaining procedural consistency across stimuli.

For clarity and consistency across figures and text, we use the terms “40-Hz–OFF” and “40-Hz–ON” to denote the absence versus presence of the added 40-Hz sine-wave layer, respectively; thus, 40-Hz–OFF corresponds to the soundscape-only control and 40-Hz–ON corresponds to the soundscape + 40 Hz condition. Throughout the manuscript, primes (A′, B′) denote the 40-Hz–OFF control stimuli, and non-primed labels (A, B) denote the 40-Hz–ON layered stimuli. Unless a step is explicitly described as condition-specific, preprocessing and mastering procedures were applied identically across 40-Hz–OFF and 40-Hz–ON stimuli, such that “soundscape-only” denotes only the absence of the added 40-Hz component (not the absence of preprocessing).

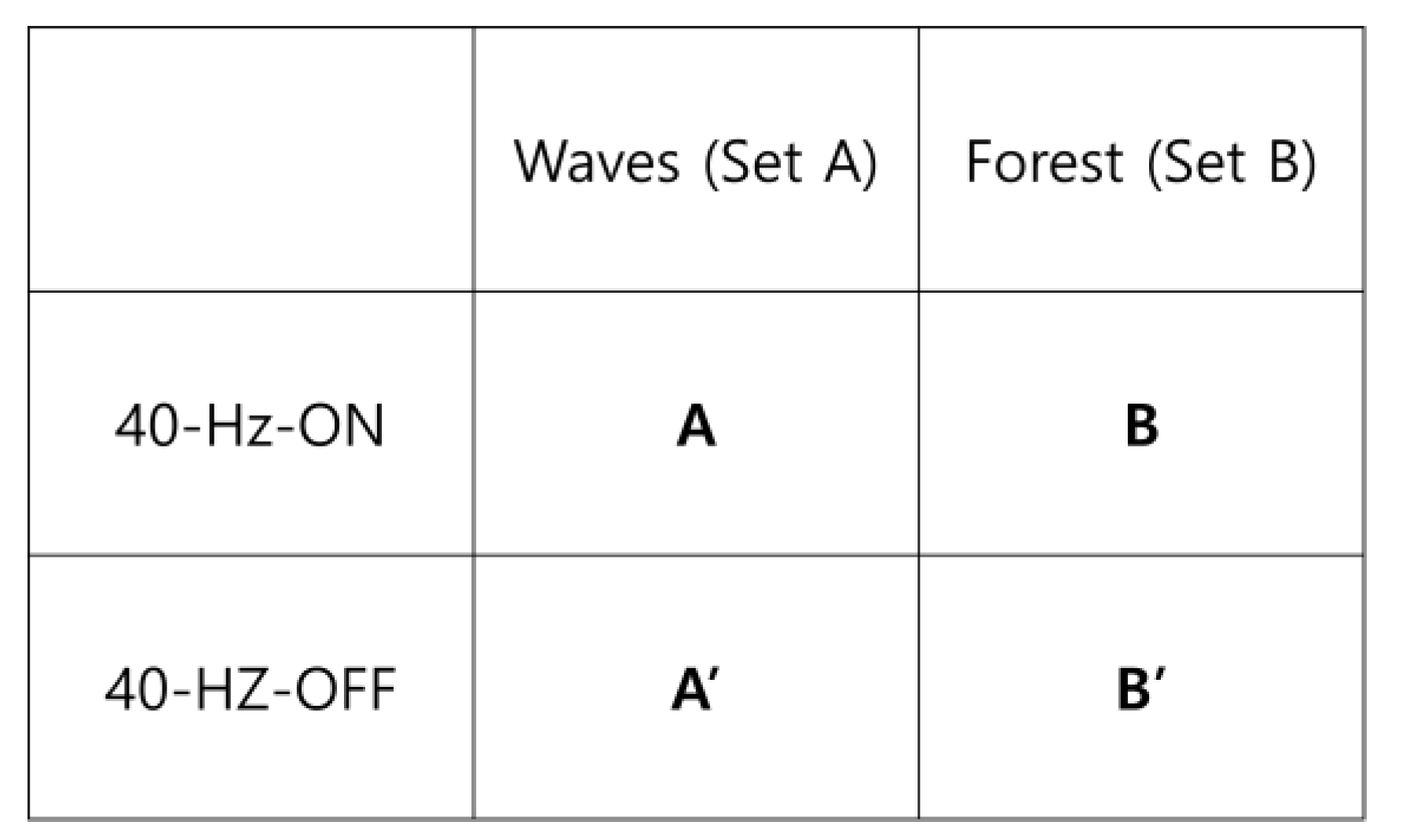

Figure 2.

Stimulus structure (2×2 schematic). Soundscape content (waves/forest) × 40-Hz layer (OFF = soundscape-only control; ON = soundscape + 40 Hz).

Figure 2.

Stimulus structure (2×2 schematic). Soundscape content (waves/forest) × 40-Hz layer (OFF = soundscape-only control; ON = soundscape + 40 Hz).

2.4.2. File Format and Production Workflow

All stimuli were produced as stereo WAV files (24-bit, 48 kHz) using a consistent production/mastering workflow. Technical QC checks included true peak, clipping, and DC offset verification (

Table 2).

2.4.3. High-Pass Filtering Prior to Layering

To standardize low-frequency energy across stimuli and minimize potential interaction between the base soundscape and the added 40-Hz component, the base soundscapes were high-pass filtered at 78 Hz (96 dB/oct) prior to final rendering. This preprocessing was applied identically to both the 40-Hz–OFF controls (A′, B′) and the 40-Hz–ON layered stimuli (A, B). For the layered stimuli, the 40-Hz sine wave was added after high-pass filtering so that the 40-Hz component itself was not attenuated.

2.4.4. Loudness Control and Technical Verification

Integrated loudness (LUFS) and true peak were targeted and monitored during production to minimize perceived level differences between conditions. Spectrogram inspection was performed for the layered stimuli (A, B), whereas numeric loudness/peak readouts were retained for the soundscape-only controls (A′, B′) and the 40-Hz reference track.

Table 2.

Technical specifications and quality-control metrics for auditory stimuli.

Table 2.

Technical specifications and quality-control metrics for auditory stimuli.

| Stimulus |

Content |

Condition |

File format |

Sampling rate /

bit depth

|

Pre-processing |

40-Hz implementation |

Integrated loudness (LUFS) |

True peak (dBTP),

L / R

|

Loudness range (LRA, LU) |

Clipping (count) |

DC offset |

| A′ |

Waves soundscape |

40-HZ-OFF

(Soundscape-only control) |

WAV (stereo) |

48 kHz / 24-bit |

HPF 78 Hz (96 dB/oct) |

None |

-18.0 |

-6.36 / -6.35 |

9.7 |

0 |

-0.001% |

| A |

Waves soundscape |

40-HZ-ON

(Soundscape

+ 40-Hz ; layered) |

WAV (stereo) |

48 kHz / 24-bit |

HPF 78 Hz (96 dB/oct) |

40-Hz sine-wave layering |

Target matched to A′

(-18.0) |

— (constraint: ≤ -6 dBTP) |

— (target matched to A′: 9.7) |

0 |

~ 0% |

| B′ |

Forest soundscape |

40-HZ-OFF

(Soundscape-only control) |

WAV (stereo) |

48 kHz / 24-bit |

HPF 78 Hz (96 dB/oct) |

None |

-19.7 |

-8.57 / -8.73 |

5.1 |

0 |

0.000% |

| B |

Forest soundscape |

40-HZ-ON

(Soundscape

+ 40-Hz ; layered) |

WAV (stereo) |

48 kHz / 24-bit |

HPF 78 Hz (96 dB/oct) |

40-Hz sine-wave layering |

Target matched to B′

(-19.7) |

— (constraint: ≤ -8 dBTP) |

— (target matched to B′: 5.1) |

0 |

~ 0% |

| — (reference) |

40-Hz component only |

Reference track |

WAV (stereo) |

48 kHz / 24-bit |

None |

40-Hz sine wave |

-20.3 |

-12.97 / -12.97 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.000% |

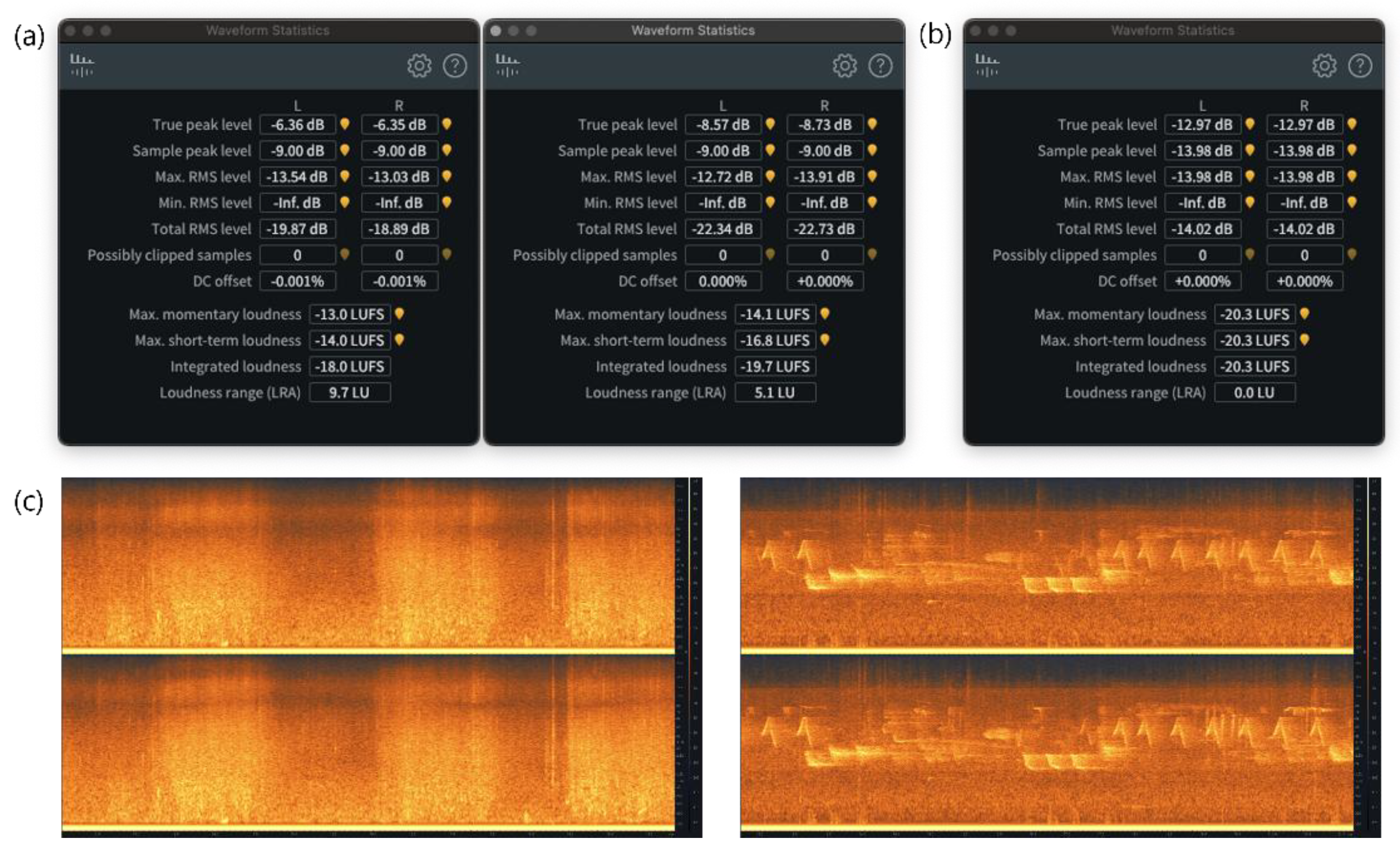

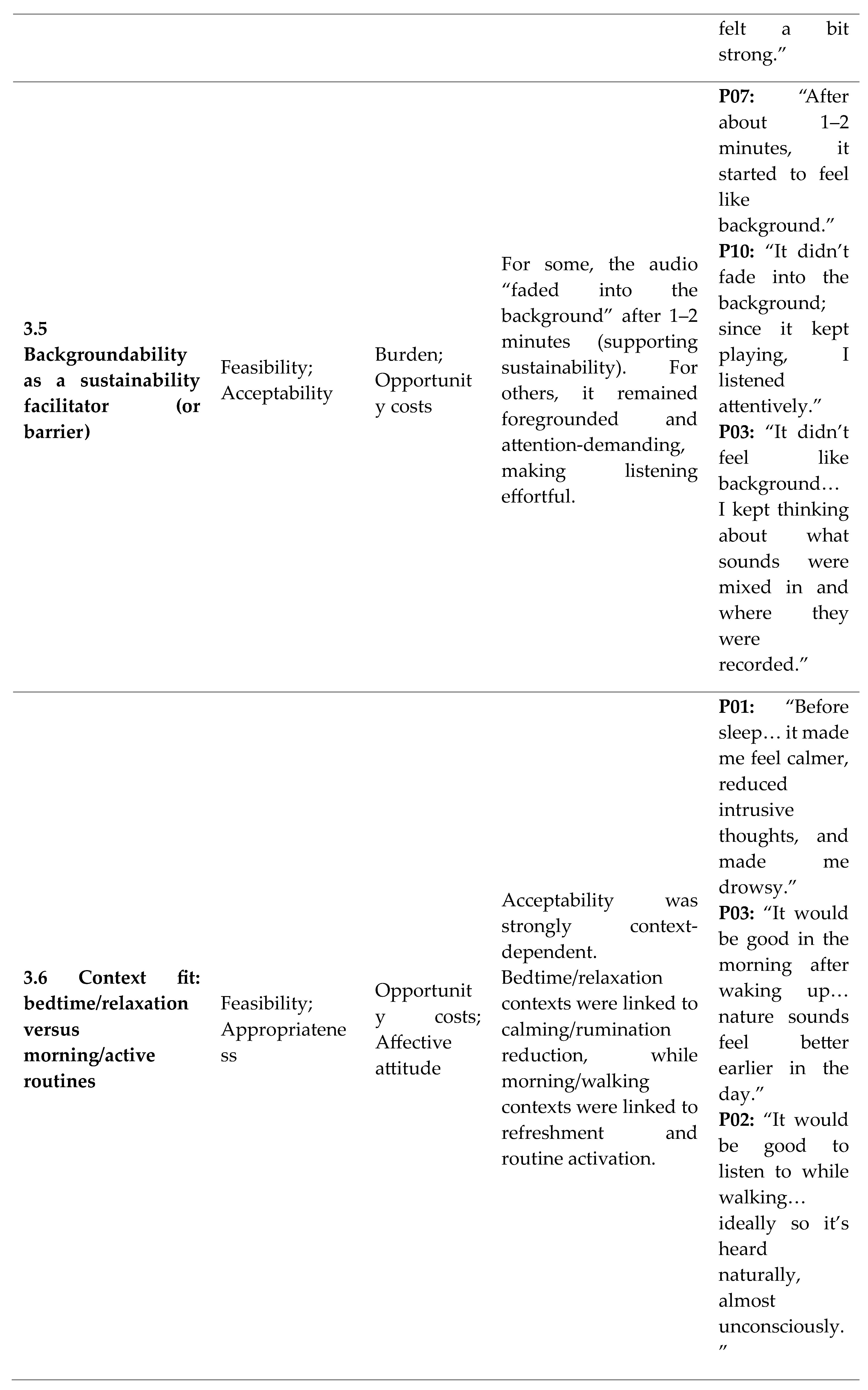

Figure 3.

Technical verification panel. (a) loudness statistics for soundscape-only; (b) loudness statistics for 40-Hz component; (c) spectrogram confirming the 40-Hz component in the layered stimuli.

Figure 3.

Technical verification panel. (a) loudness statistics for soundscape-only; (b) loudness statistics for 40-Hz component; (c) spectrogram confirming the 40-Hz component in the layered stimuli.

2.5. Procedure

Each participant was assigned to one soundscape set (Set A: waves or Set B: forest) and completed a within-participant comparison of two conditions within that assigned set. For clarity, “40-Hz–OFF” denotes the soundscape-only control (A′/B′), whereas “40-Hz–ON” denotes the layered stimulus with an added 40-Hz sine-wave component (A/B). Condition order (OFF

→ON vs. ON

→OFF) was counterbalanced across participants to reduce order effects (

Table 1).

All sessions were conducted in Seoul, Republic of Korea, in a rented residence-hotel setting to support comfortable, low-distraction listening. This setting was selected to approximate a comfortable everyday listening context and to reduce environmental distractions that could confound perceived acceptability. Participants listened in a quiet private room in a seated, relaxed posture. Audio was played from a laptop-based media player with the operating-system and player volume preset at session start and held constant across conditions; sound pressure level was not individually calibrated. Participants listened using wired in-ear earphones (Sony XBA-A2; hybrid 3-way system: 12-mm dynamic driver + dual balanced armature drivers; impedance 32 Ω at 1 kHz; sensitivity 108 dB/mW; frequency response 4–40,000 Hz) [

22].

Each condition comprised seven cycles of 50 s playback followed by 10 s silence (approximately 7 min per condition). A 10 min washout period was provided between conditions. Immediately after each condition, participants completed brief post-condition ratings (e.g., discomfort, fatigue, preference, willingness to reuse) to support real-time interview probing and recall of condition-specific impressions. These brief ratings were treated as part of the qualitative elicitation procedure and were not analyzed as standalone quantitative outcomes in this exploratory manuscript, because they were intentionally brief prompts rather than a validated measurement set for statistical comparison. After completing both conditions, participants additionally completed a session-end 7-point Likert appraisal for the 40-Hz–ON stimulus to provide a descriptive complement focused on the intended intervention stimulus.

2.6. Qualitative Data Collection and Framework Mapping

Semi-structured interviews were conducted in Korean immediately after the listening session and lasted approximately 30 min per participant. To minimize distractions and support candid responses, interviews were conducted in a separate vacant private room after the listening session. The interview guide covered: (i) overall experience and affective response, (ii) discomfort/burden and anticipated sustainability, (iii) perceived understanding and sense-making of the intervention, (iv) perceived value and expected benefits, (v) delivery-channel and context preferences (personal listening vs. ambient/space playback; privacy; environmental noise), (vi) dosage preferences (session length, frequency, volume), and (vii) interaction design requirements (automation, minimized manipulation, fatigue management, and guidance). The guide was mapped a priori to Proctor’s implementation outcomes [

12] and TFA constructs [

13] to support structured reporting in the Results (

Table 3).

2.7. Analysis

All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and anonymized prior to analysis. We conducted an inductive thematic analysis following Braun and Clarke [

23]. Transcripts were read iteratively to generate initial codes, which were refined through repeated comparison across participants and consolidated into candidate themes. Throughout the later analytic stages, themes were interpreted and organized using the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability (TFA) [

13] and Proctor et al.’s implementation outcomes [

12] as sensitizing frameworks to support structured reporting.

To enhance analytic rigor, two researchers independently coded an initial subset of transcripts to align coding decisions and develop a shared codebook. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved by consensus, after which the remaining transcripts were coded using the refined codebook with periodic consensus checks. Coding and theme management were conducted using spreadsheet-based coding matrices (Microsoft Excel), and an audit trail (memos and code/theme logs) was maintained to document analytic decisions. Given the exploratory purpose and sample size, themes are presented to reflect the range of perspectives rather than to imply frequency or saturation-based completeness.

Likert responses were analyzed descriptively. Item-wise responses were summarized primarily using medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), with means and standard deviations additionally reported for transparency. Distributions were visualized using boxplots with overlaid individual data points. No inferential statistical testing was performed.

2.8. Rigor

We reported study context, participant characteristics, data collection, and analysis procedures in line with SRQR and COREQ recommendations [

20,

21]. We also preserved an audit trail of analytic decisions (coding memos and theme logs) to enhance trustworthiness.

Quoted excerpts were translated from Korean to English for reporting; translations were reviewed for clarity and meaning preservation prior to finalization. Quote translations were produced by bilingual researchers and reviewed through discussion to resolve ambiguities and preserve meaning; no formal back-translation was performed.

3. Results

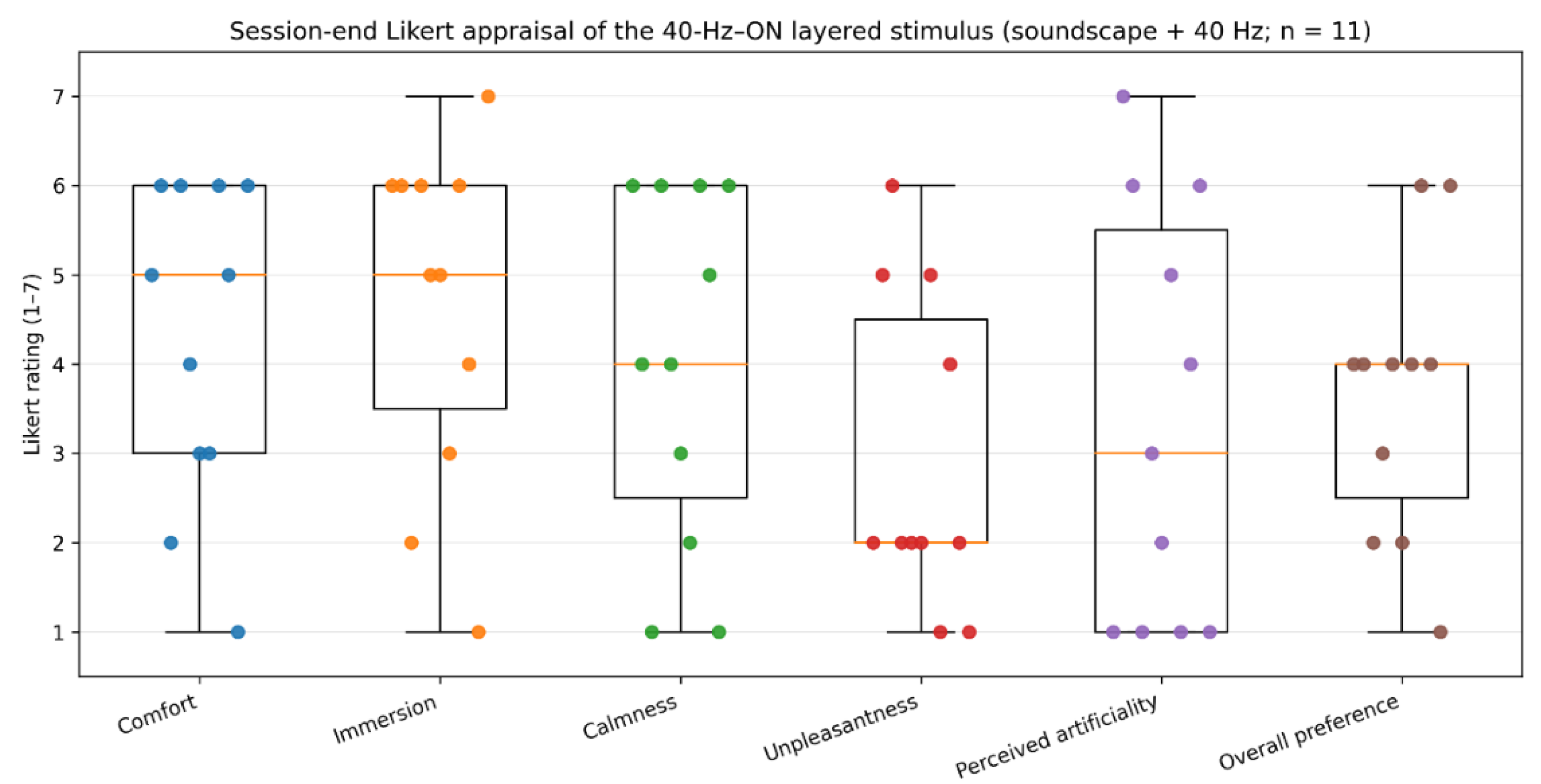

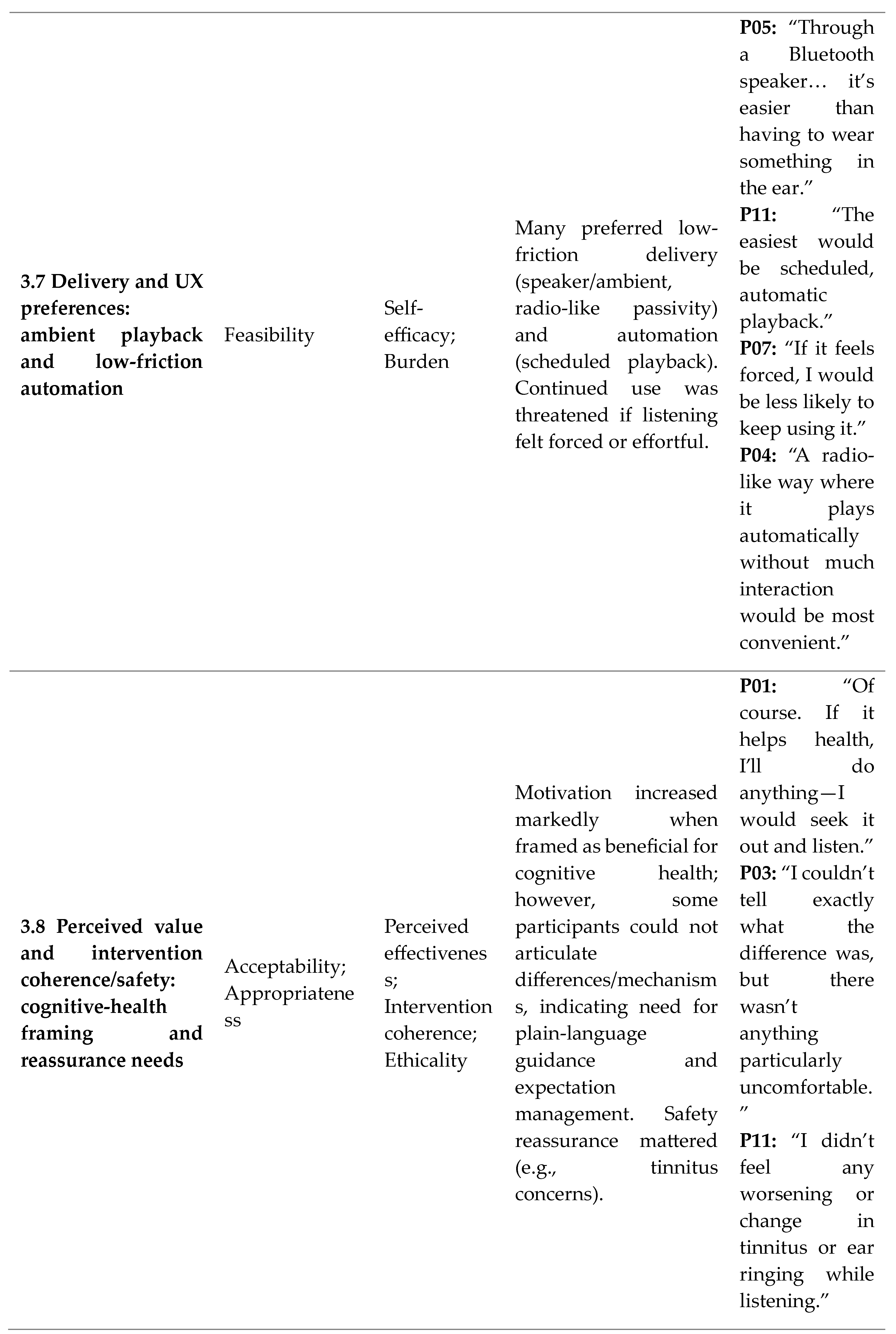

3.1. Session-end Likert Appraisal of the 40-Hz–ON Layered Stimulus (n = 11)

On 7-point Likert appraisals of the 40-Hz–ON layered stimulus (soundscape + 40-Hz sine-wave component), comfort (median 5, IQR 3–6), immersion (median 5, IQR 3.5–6), and calmness (median 4, IQR 2.5–6) were generally reported at mid-to-high levels. Unpleasantness was relatively low (median 2, IQR 2–4.5), whereas perceived artificiality showed substantial inter-individual variability (median 3, IQR 1–5.5; range 1–7). Overall preference was moderate (median 4, IQR 2.5–4; range 1–6). Descriptive statistics are summarized in

Table 4 and distributions are visualized in

Figure 4; no inferential testing was performed. The session-end questionnaire was intentionally administered for the 40-Hz–ON stimulus to summarize acceptability of the intended intervention stimulus; condition-by-condition immediate ratings were collected to support interview probing and were not intended as quantitative endpoints; therefore, we report the session-end appraisal focused on the intended intervention stimulus (40-Hz–ON).

3.2. Detectability of 40-Hz Inclusion: Individual Variability in Perceived Differences Between 40-Hz–ON and 40-Hz–OFF Conditions

Consistent with the mixed design, participants completed a within-participant comparison of 40-Hz inclusion (40-Hz–ON vs. 40-Hz–OFF) within an assigned soundscape set (waves vs. forest). Interview responses ranged from “no noticeable difference” to clear discrimination based on perceptual cues. Some participants reported that the two versions felt essentially the same and were uncertain whether any difference existed (e.g., P09). Others differentiated the versions via low-frequency sensations described as “vibration” or “bass-like rumble” (e.g., P01). A subset characterized one version as having a salient “mechanical/artificial” timbre (e.g., P10), suggesting that subtle timbral artifacts can meaningfully shape preference and willingness to reuse.

3.3. Affective Acceptability Hinges on Perceived Naturalness Versus “Mechanical/Artificial” Cues

Many participants described the stimulus as broadly listenable and tolerable, particularly when the soundscape was perceived as naturalistic and restorative (e.g., P03). However, acceptability decreased sharply for some participants when the listening experience was dominated by salient artificial or mechanical cues (e.g., P10). Importantly, participants’ accounts suggested that acceptability was shaped less by the concept of “40 Hz” itself than by experienced timbre/texture—whether the layered elements blended naturally or drew attention as an intrusive artifact (e.g., P02).

3.4. Burden and Fatigue: Onset Impressions, Level Sensitivity, and Repetition-Related Effort

Most participants did not report major fatigue. Nevertheless, several noted that the initial moment could feel loud, abrupt, or momentarily uncomfortable, and then became more tolerable as listening continued (e.g., P03; P05). Reports of bothersome moments pointed to early level impressions and specific recurrent sound elements as potential triggers (e.g., P07). These findings emphasize practical design needs such as gentle onset handling (e.g., fade-in), conservative default levels, and repetition-fatigue management to support sustained use.

3.5. Backgroundability as a Sustainability Facilitator

Some participants reported that the sound became background-like within 1–2 minutes (e.g., P07), which aligned with comfort and anticipated sustainability. Conversely, when listeners remained analytically attentive to layered elements, the experience did not “fade” and could become effortful (e.g., P10; P03). This suggests that optimizing for background listening—minimizing attention-grabbing repetitions and salient artificial cues—may enhance real-world feasibility.

3.6. Context Fit: Bedtime/Relaxation Versus Morning/Active Routines

Participants proposed bedtime relaxation and morning refreshment/walking contexts as plausible use scenarios. Bedtime listening was associated with relaxation and reduced intrusive thoughts, facilitating drowsiness and perceived readiness for sleep (e.g., P01). In contrast, morning contexts were linked to refreshment and routine activation (e.g., P03). Some also highlighted walking as a feasible everyday setting, ideally enabling effortless, low-attention listening (e.g., P02). These patterns support routine-based presets (e.g., “Sleep routine,” “Morning routine”) that match listening contexts and reduce decision-making burden.

3.7 Delivery and UX Preferences: Ambient Playback and low-Friction Automation

While a minority preferred earphones for personal control, many participants favored ambient speaker playback as more natural and less effortful than wearing earphones (e.g., P05). Participants also expressed a clear preference for low-friction automation, such as timer-based scheduled playback (“set-and-forget”) and an easily accessible stop function (e.g., P11). Moreover, continued use was threatened when listening felt mandatory or externally imposed (e.g., P07), underscoring the importance of autonomy-supportive UX and flexible, user-controlled scheduling.

3.8. Perceived Value and Intervention Coherence: Cognitive-Health Framing and Guidance Needs

Willingness to use increased substantially when the intervention was framed as potentially beneficial for cognitive health (e.g., memory maintenance) (e.g., P01). This highlights perceived effectiveness as a strong acceptability driver. However, participants also indicated gaps in intervention coherence: some could not articulate what differed between versions or how the stimulus might work, despite describing the experience as tolerable (e.g., P03). In addition, reassurance around safety perceptions (e.g., concerns about tinnitus or ear ringing) appeared important for ethical acceptability (e.g., P11). Accordingly, implementation should provide plain-language explanations and expectation management without overclaiming, accompanied by appropriate disclaimers. A structured mapping of interview-derived themes to implementation outcomes and TFA constructs is provided in

Table 5.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Findings

This study provides an implementation-first account of the practical potential for integrating additive 40-Hz sine-wave layering (i.e., not amplitude modulation) into nature-based soundscapes as an everyday-compatible listening medium. Distinct from prior acceptability work centered on amplitude-modulated auditory stimulation or music-based gamma content, our contribution is to (i) examine a soundscape-based intervention intended to reduce music preference dependence and (ii) translate user evidence into concrete UX and deployment requirements for scalable delivery (

Table 6).

Using a mixed design in which participants completed a within-participant comparison of 40-Hz inclusion (40-Hz–ON vs. 40-Hz–OFF) within an assigned soundscape set (waves vs. forest), we found that acceptability was heterogeneous rather than uniform. In the descriptive session-end appraisal of the intended intervention stimulus (40-Hz–ON; n = 11), comfort and immersion were typically rated at moderate-to-high levels (medians = 5), calmness was moderate (median = 4), and unpleasantness was relatively low (median = 2), although perceived artificiality showed the widest variability.

Interview data clarified why this variability matters for real-world uptake: acceptability was shaped less by “40 Hz” as a concept than by perceptual salience—whether the added layer blended naturally or became noticeable as low-frequency “vibration/rumble” or a “mechanical/artificial” timbre. When such cues were salient, they became decisive drivers of aversion for a subset; conversely, when the soundscape remained naturalistic and “backgroundable,” participants anticipated greater sustainability. Together, these findings support a cautious but positive interpretation: soundscapes can function as a promising delivery pathway for 40-Hz auditory stimulation, provided that acoustic salience is carefully managed and the listening experience is designed for everyday context fit and low burden.

4.2. Implementation Implications for Scalable Delivery and UX

Participant feedback highlighted actionable determinants for real-world deployment. First, delivery modality mattered: several participants perceived earphone-based listening as effortful, while speaker-based ambient playback was described as more natural and potentially more sustainable. This suggests that scalable delivery should incorporate space-oriented options (e.g., living rooms/bedrooms/relaxation areas) rather than relying solely on personal listening.

Second, interaction burden was central to anticipated adherence. Participants repeatedly emphasized minimal manipulation, favoring one-tap start, scheduled or timer-based playback (“set-and-forget”), and an easily accessible quick stop. A sense of obligation (“having to listen every day”) was described as a barrier, indicating that routine integration should prioritize autonomy and optionality, enabling users to pause, skip, or discontinue with minimal friction.

Third, practical safeguards are required to address acoustic acceptability. Reports of startle-like onset impressions and aversion to low-frequency rumble or mechanical/artificial timbre in a subset support the need for gentle onset handling (fade-in), conservative default levels, simple volume guidance, and sensitivity-oriented options (e.g., lower-intensity or alternative mixes). Finally, willingness increased under a cognitive-health framing, but this should be paired with evidence-aligned, non-exaggerated explanations and appropriate disclaimers to strengthen intervention coherence.

Table 6.

Actionable implementation requirements derived from user feedback. The table summarizes deployment and UX requirements implied by participant accounts, including delivery modality (ambient/space playback vs personal listening), automation and manipulation burden, autonomy and routine flexibility, onset and level handling, acoustic acceptability safeguards, context-based presets, and coherence-focused guidance. Requirements are intended to inform future prototyping and field deployment rather than to imply efficacy.

Table 6.

Actionable implementation requirements derived from user feedback. The table summarizes deployment and UX requirements implied by participant accounts, including delivery modality (ambient/space playback vs personal listening), automation and manipulation burden, autonomy and routine flexibility, onset and level handling, acoustic acceptability safeguards, context-based presets, and coherence-focused guidance. Requirements are intended to inform future prototyping and field deployment rather than to imply efficacy.

| Domain |

Actionable requirement

(what to implement)

|

Operational specification (UX/deployment) |

| Delivery modality |

Support ambient/space playback in addition to personal listening |

Provide a “Speaker/Ambient mode” (e.g., living room/bedroom/relaxation area) alongside an earphone/headphone mode; include brief guidance on when each mode is recommended (privacy vs effort-free use). |

| Interaction burden |

Minimize manipulation via one-tap start, scheduled/timer playback, and quick stop |

Implement: (i) one-tap start of the last-used routine, (ii) scheduled playback and/or timer (“set-and-forget”), (iii) an always-accessible quick stop; keep controls sparse (start/stop, level, schedule). |

| Autonomy and optionality |

Ensure routines feel optional, not mandatory |

Allow skip/pause/discontinue without penalties; frame routines as user-chosen presets rather than daily obligations; avoid messaging that implies “must listen every day.” |

| Acoustic acceptability safeguards |

Provide gentle onset handling and sensitivity-oriented options |

Default fade-in at session start; conservative default level; simple volume guidance; offer “lower-intensity” or alternative mixes for users sensitive to low-frequency rumble or “mechanical/artificial” timbre. |

| Level handling and guidance |

Use conservative defaults and simple guidance rather than calibration-heavy protocols |

Set a comfortable default playback level; provide a short prompt (“keep at a comfortable level; stop if uncomfortable”); optionally include a brief first-use “comfort check.” |

| Coherence-focused guidance |

Provide plain-language explanation with non-exaggerated framing and disclaimers |

Add a concise “What this is / What to expect” description; avoid efficacy claims; include a clear disclaimer (e.g., not a medical device; not a treatment) and expectation management. |

4.3. Limitations

Several limitations should be considered. This study was not designed to test efficacy or to draw causal conclusions about 40-Hz–related outcomes; rather, it focused on acceptability and implementation determinants. The sample size was small and recruitment was geographically localized, which may limit transferability. Playback volume was preset without individualized sound pressure level calibration; therefore, perceptual differences may have been influenced by individual sensitivity and listening context. High-pass filtering (78 Hz, 96 dB/oct) was applied identically across conditions; therefore, perceived differences between 40-Hz–ON and 40-Hz–OFF conditions are unlikely to be attributable to differences in high-pass filtering. However, the exact component-to-soundscape mixing level was not retained as a separately logged parameter. The Likert questionnaire served as a descriptive complement and should not be interpreted as inferential evidence.

5. Conclusions

This qualitative exploratory study suggests that integrating an additively layered 40-Hz sine wave into nature-based soundscapes can be acceptable as an everyday listening experience, although responses are heterogeneous and sensitive to timbral salience and usage context. Session-end appraisals of the intended intervention stimulus (40-Hz–ON) indicated mid-to-high comfort and immersion with a low median unpleasantness; however, interviews showed that perceived low-frequency “vibration/rumble” and “mechanical/artificial” timbral cues could become decisive drivers of aversion for a subset, whereas “backgroundable” naturalistic listening supported anticipated sustainability.

From an implementation perspective, scalable uptake is likely to depend on space-oriented ambient playback options, ultra-low-friction automation and control, acoustic acceptability safeguards (e.g., fade-in and conservative default levels), and coherence-focused guidance with evidence-aligned framing and appropriate disclaimers (

Table 6). Future studies should evaluate these implementation refinements in larger and more diverse samples, including target populations such as older adults with MCI. Longitudinal field trials will be important to examine sustained use, routine integration, and preference drift over time, alongside downstream neurophysiological or clinical outcomes assessed in appropriately powered designs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.N. and K.L.; Methodology, K.N. and K.L.; Software, K.N.; Validation, K.N.; Formal analysis, K.N.; Investigation, K.N. and K.L.; Resources, K.N.; Data curation, K.N.; Writing—original draft preparation, K.N.; Writing—review and editing, K.N.; Visualization, K.N.; Supervision, K.N.; Project administration, K.N.; Funding acquisition, K.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.