Introduction

Infertility represents a major global health concern, affecting approximately 10–15% of couples of reproductive age worldwide, and is widely recognized as a condition with substantial psychological, social, and economic consequences[

1,

2]. Intrauterine insemination (IUI) combined with ovulation induction (OI) remains a first-line therapeutic approach for couples with unexplained infertility, mild male factor infertility, and selected cases of ovulatory dysfunction, particularly polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)[

3,

4]. Owing to its relative simplicity, lower cost, and minimal invasiveness compared with in vitro fertilization (IVF), IUI is frequently recommended before proceeding to more complex assisted reproductive technologies.

The success of IUI largely depends on the ovarian stimulation strategy, which aims to achieve optimal follicular development while preserving endometrial receptivity and minimizing adverse outcomes such as ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) and multiple gestations[

5]. Over the years, several pharmacological agents—including clomiphene citrate, aromatase inhibitors, and gonadotropins—have been used either alone or in combination to improve treatment efficacy[

6].

Recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone (rFSH) is widely used for ovarian stimulation in IUI cycles because of its potent and predictable effect on follicular recruitment and growth. Multiple randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses have demonstrated that gonadotropin-based stimulation protocols yield higher pregnancy rates per cycle compared with oral ovulation induction agents alone[

7,

8].However, these benefits are often accompanied by increased treatment costs, a higher incidence of multiple pregnancies, and an elevated risk of OHSS, particularly in women with PCOS or high ovarian reserve[

9].

In recent years, letrozole, a third-generation aromatase inhibitor, has emerged as an effective alternative for ovulation induction. Letrozole suppresses estrogen synthesis by inhibiting the aromatization of androgens to estrogens, leading to a transient hypoestrogenic state that enhances endogenous follicle-stimulating hormone secretion while preserving estrogen receptor sensitivity at the hypothalamic–pituitary level[

10].Unlike clomiphene citrate, letrozole does not exert prolonged anti-estrogenic effects on the endometrium or cervical mucus, thereby potentially improving endometrial receptivity.[

11].Large-scale clinical studies have demonstrated superior ovulation and live birth rates with letrozole compared with clomiphene citrate in women with PCOS, resulting in its adoption as a first-line treatment in this population[

12].

Beyond its use as monotherapy, letrozole has increasingly been incorporated into sequential or combination stimulation protocols with gonadotropins. This strategy aims to reduce gonadotropin requirements, promote favorable endometrial development, and limit the risk of excessive ovarian response[

13].Several studies suggest that letrozole combined with low-dose or delayed-onset gonadotropin stimulation may achieve pregnancy rates comparable to conventional gonadotropin protocols, while offering improved safety and cost-effectiveness[

14,

15].However, whether these apparent advantages translate into an independent improvement in pregnancy outcomes, or merely reflect underlying patient characteristics and ovarian reserve profiles, remains uncertain.

This study evaluates the clinical and pregnancy outcomes of letrozole with late-onset rFSH compared to conventional rFSH in IUI cycles, particularly focusing on pregnancy rates after adjusting for confounding factors. It aims to optimize reproductive outcomes while minimizing gonadotropin use and the risk of OHSS in women with PCOS or high AFC, and will also assess gonadotropin utilization, safety outcomes, and clinical efficiency in high-risk patients.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Study Population

This retrospective comparative cohort study was conducted at the University of Health Sciences, Assisted Reproductive Technologies Center, Adana City Hospital, between January 2022 and December 2025. The study evaluated IUI cycles performed in women presenting with infertility, defined as failure to achieve pregnancy after at least 12 months of regular unprotected intercourse.

A total of 764 IUI cycles were included in the final analysis. Eligible women were aged between 18 and 40 years, and at least one patent fallopian tube confirmed by hysterosalpingography, saline infusion sonography, or transvaginal ultrasonography. Both initial and subsequent IUI attempts during the study period were included. Following semen preparation, all male partners had a total progressive motile sperm count (TPMSC) of ≥1 × 10⁶.

Patients were categorized into two groups according to the ovarian stimulation protocol used:

Group 1 (Standard rFSH Group): Cycles stimulated exclusively with conventional recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone (rFSH), initiated on cycle day 2 or 3.

Group 2 (Letrozole + Late rFSH Group): Cycles stimulated with oral letrozole administered early in the follicular phase (cycle days 3–7), followed by late-onset gonadotropin stimulation initiated on cycle day 6 or later.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Adana City Hospital (Approval No: 11.20.2025-898), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to treatment. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Women were eligible for inclusion if they were ≤40 years of age, had a minimum infertility duration of 12 months, and exhibited a normal uterine cavity with at least one unobstructed fallopian tube. Adequate baseline ovarian reserve was required, defined as a basal follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) level <12 mIU/mL, along with normal thyroid-stimulating hormone and prolactin levels. Following semen preparation, male partners were required to have a TPMSC of at least 1 × 10⁶.

Exclusion criteria included a body mass index (BMI) ≥40 kg/m², potentially affecting uterine cavity integrity, advanced endometriosis (stage III–IV), or significant uterine or adnexal pathology. Patients with large intramural or submucosal fibroids causing cavity distortion, known breast pathology, or other contraindications to gonadotropin use were also excluded.

Ovarian Stimulation Protocols

Ovarian stimulation was performed using either a letrozole-based sequential protocol combined with gonadotropins or a gonadotropin-only regimen, according to routine clinical practice and physician discretion.

In Group 1, ovarian stimulation commenced on cycle day 2 or 3 using rFSH alone.

In Group 2, letrozole (2.5–5 mg/day; Novartis, Istanbul, Türkiye) was administered orally from cycle day 3 through day 7. Gonadotropin stimulation was initiated on cycle day ≥6 using recombinant FSH (rFSH; Gonal-F®, Merck Serono, Bari, Italy).

Initial gonadotropin doses ranged from 37.5 to 250 IU/day and were individualized based on female age, BMI, ovarian reserve markers (anti-Müllerian hormone [AMH] and antral follicle count), and previous ovarian response. Dose adjustments were made according to follicular growth during cycle monitoring.

A mild-to-moderate stimulation strategy was adopted in all cycles to promote mono- or bifollicular development and to minimize the risk of OHSS.

Cycle Monitoring and Data Collection

Follicular development and endometrial growth were monitored by transvaginal ultrasonography and serial serum estradiol (E2) measurements performed every 2–3 days. The following parameters were recorded for each cycle:

Duration of stimulation (days)

Total gonadotropin dose (IU)

Number of follicles measuring ≥17 mm

Number of follicles measuring ≥14-17 mm

Endometrial thickness on the day of ovulation trigger (mm)

Serum estradiol (E2) concentration on the trigger day (pg/mL)

Ovulation Trigger, Insemination Procedure, and Luteal Phase Support

Ovulation was triggered with a subcutaneous injection of recombinant human chorionic gonadotropin (r-hCG) (Ovitrelle® 250 μg/0.5 mL, Merck Serono) when at least one follicle reached a mean diameter of ≥17 mm.

Intrauterine insemination was performed 36–38 hours after hCG administration using a Soft-Pass Coaxial IUI catheter (Cook Medical, USA). Semen samples were processed using standard density gradient centrifugation techniques.

Cycles were cancelled if more than three dominant follicles developed in order to reduce the risk of multiple gestation and OHSS. All patients received luteal phase support with vaginal progesterone capsules (200 mg/day; Koçak Farma, Istanbul, Türkiye) for 14 days following insemination.

Serum β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) levels were measured 14 days after IUI. In cycles with positive β-hCG results, transvaginal ultrasonography was performed 20–25 days later to confirm clinical pregnancy.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure was pregnancy per cycle, defined as a positive serum β-hCG test. Secondary outcomes included clinical pregnancy, confirmed by visualization of a gestational sac with fetal cardiac activity on transvaginal ultrasound. Additional secondary outcomes comprised total gonadotropin dose administered, endometrial thickness on the day of hCG trigger, serum estradiol levels on the trigger day, number of follicles ≥17 mm, cycle cancellation rate, multiple pregnancy rate, and incidence of OHSS.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Supplementary analyses incorporating propensity score and regression modeling were conducted using appropriate statistical procedures. A two-sided p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Descriptive and Univariate Analyses

Normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Normally distributed continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, whereas non-normally distributed variables were summarized as median with interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages.

Between-group comparisons were conducted using the independent samples t-test for normally distributed variables and the Mann–Whitney U test for non-normally distributed variables. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate.

Multivariable Logistic Regression Analysis

To identify independent predictors of pregnancy and to account for confounding, multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed. Variable selection was guided by clinical relevance, biological plausibility, and prior literature, while avoiding over-adjustment and multicollinearity.

A parsimonious modeling strategy was adopted. Among correlated ovarian reserve parameters (polycystic ovary syndrome status, antral follicle count, and basal gonadotropins), AMH was selected as the primary representative marker of ovarian reserve. Variables reflecting downstream treatment decisions (total gonadotropin dose, initial stimulation dose, and hCG trigger day) were excluded to avoid adjustment for mediators.

The final multivariable model included:

female age,

stimulation protocol (letrozole plus late-onset rFSH vs conventional rFSH),

AMH level,

endometrial thickness on the day of hCG administration,

number of follicles ≥17 mm on the trigger day.

Model performance was assessed using the Omnibus test of model coefficients, Cox & Snell R², and Nagelkerke R². Model calibration was evaluated with the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test.

Assessment of Interaction Effects

Interaction terms between stimulation protocol and female age, as well as between stimulation protocol and AMH level, were incorporated into the multivariable logistic regression model to assess potential effect modification.

Propensity Score–Based Analyses

To further address baseline imbalances inherent to the non-randomized design, propensity score matching (PSM) was performed. Propensity scores were estimated using a logistic regression model including: female age, AMH, AFC, FSH) level, PCOS status.

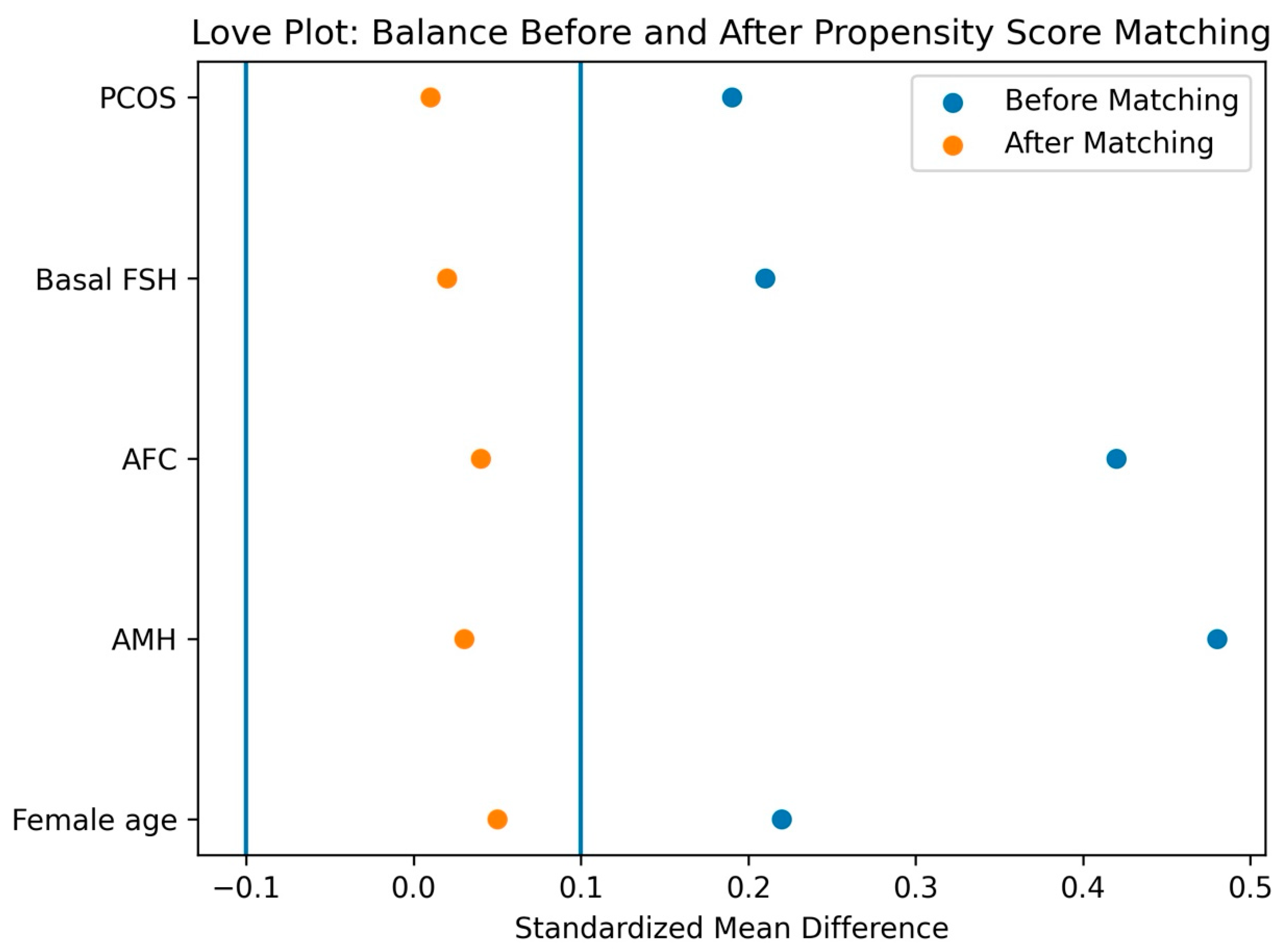

One-to-one nearest-neighbor matching without replacement was performed using a caliper width of 0.2 standard deviations of the logit of the propensity score. Covariate balance before and after matching was assessed using standardized mean differences (SMDs), with SMD <0.10 indicating adequate balance. Balance was graphically evaluated using Love plots.

Outcome Analysis in the Matched Cohort

In the matched sample, pregnancy rates were compared between groups. Treatment effects were estimated using matched odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) derived from McNemar’s test for paired binary outcomes. Risk differences (RDs) were also calculated to provide absolute effect estimates.

Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting (IPTW)

As a complementary approach, IPTW was applied to estimate the average treatment effect (ATE) in the full cohort. Stabilized inverse probability weights were calculated using the same propensity score model. Weighted logistic regression models were fitted, and treatment effects were expressed as ORs with 95% CIs.

Doubly Robust Estimation

To further strengthen causal inference, a doubly robust approach combining IPTW with multivariable outcome regression was employed. This method yields consistent estimates if either the propensity score model or the outcome model is correctly specified.

Sensitivity Analyses

Sensitivity analyses included variation of caliper widths (0.1–0.25 standard deviations), alternative weighting specifications in IPTW, and assessment of common support and overlap of propensity score distributions. Consistency in effect direction and magnitude across analyses was considered supportive of robustness.

Results

A total of 764 intrauterine insemination (IUI) cycles were included in the final analysis. Of these, 392 cycles were stimulated using a letrozole plus late-onset rFSH protocol, while 372 cycles received conventional rFSH stimulation. In the unadjusted analysis, the pregnancy rate per cycle was significantly higher in the letrozole plus late-rFSH compared with group the conventional rFSH group (14.8% vs. 9.9%, p = 0.042). (

Table 1) The prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) was also significantly higher in the letrozole plus late-rFSH group (32.4% vs. 16.6%, p = 0.001). Cycle cancellation rates were low in both groups and did not differ significantly (2.1% vs. 0.5%, p = 0.12).

With respect to pregnancy outcomes, miscarriage occurred in 14 cycles in the letrozole group and in 8 cycles in the conventional rFSH group, while ectopic pregnancy was rare in both groups. The number of ongoing pregnancies was higher in the letrozole group (24 vs. 5), whereas singleton live birth rates were comparable between groups. Twin and preterm deliveries were infrequent and did not demonstrate a consistent pattern favoring either protocol.

Baseline clinical and laboratory characteristics differed significantly between treatment groups (

Table 2). Women in the conventional rFSH group were slightly older and had a marginally higher body mass index. In contrast, ovarian reserve markers—including AMH levels and antral follicle count—were significantly higher in the letrozole plus late-onset rFSH group, while basal FSH levels were lower.

The letrozole plus late-onset rFSH protocol required a significantly lower total gonadotropin dose, indicating a clear gonadotropin-sparing effect, and, as a result, a lower medication cost for ovulation induction. However, the ovarian stimulation duration leading up to the hCG trigger day was similar between the two groups. Endometrial thickness on the trigger day was significantly thinner in the letrozole group compared with the conventional rFSH group.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to identify independent predictors of pregnancy (

Table 3). After adjust-ment for female age, stimulation protocol, AMH level, endometrial thickness on the day of hCG administration, and number of follicles ≥17 mm, female age emerged as the only independent predictor of pregnancy outcome (adjusted OR 0.70 per year in-crease; 95% CI 0.64–0.77; p <0.001).

The stimulation protocol did not demonstrate an independent association with pregnancy outcome after adjustment (adjusted OR 1.09; 95% CI 0.68–1.74; p = 0.657). Neither AMH level, endometrial thickness, nor follicle number independently predicted pregnancy. Interaction analyses revealed no significant effect modification by female age or AMH level, indicating that the absence of an independent protocol effect was consistent across different age groups and ovarian reserve strata.

In the overall cohort (n = 764), pregnancy per cycle occurred in 58/392 (14.8%) cycles using the sequential letrozole + late-onset rFSH protocol and in 37/372 (9.9%) cycles using conventional rFSH, corresponding to a crude risk difference of +4.8 percentage points and a crude odds ratio (OR) of 1.57 (95% CI 1.01–2.44; p = 0.044). (

Figure 1).

To reduce baseline confounding

, propensity score matching (PSM) was performed using female age, AMH, AFC, basal FSH, and PCOS status, yielding 287 well-balanced matched pairs

(all SMDs < 0.10

). In the matched cohort, pregnancy rates were 39/287 (13.6%) in the letrozole-based group and 32/287 (11.2%) in the conventional rFSH group (RD +2.4 pp), with no statistically significant difference (matched OR 1.24 [0.76–2.02]; p = 0.457) (

Table 4).

Outcome was pregnancy per cycle (positive serum beta-hCG). Treatment groups were conventional recombinant FSH stimulation (reference) and a sequential protocol of early letrozole followed by late-onset rFSH. Propensity scores were estimated using logistic regression including female age, AMH, total antral follicle count, basal day-3 FSH, and PCOS status. PSM used 1:1 nearest-neighbor matching without replacement with a caliper width of 0.2 SD of the logit of the propensity score. Covariate balance was assessed using standardized mean differences (SMD), with SMD <0.10 indicating adequate balance. Unadjusted comparisons used the chi-square test. Matched analyses used McNemar exact test; ORs were computed from discordant pairs. IPTW used stabilized inverse probability of treatment weights targeting the average treatment effect (ATE); treatment effects were estimated with weighted logistic regression using robust (sandwich) standard errors. Doubly robust estimates were obtained by fitting a weighted logistic regression additionally adjusted for the same baseline covariates. GEE logistic regression accounted for within-pair correlation in matched data (exchangeable working correlation; robust standard errors). Risk differences are reported in percentage points (pp). All p-values are two-sided.

Consistently, IPTW analyses produced weighted pregnancy rates of 14.5% vs 11.4%

(RD +3.2 pp) and a non-significant association (OR 1.33 [0.87–2.03]; p = 0.194). The doubly robust model similarly showed no independent protocol effect (OR 1.42 [0.92–2.18]; p = 0.113

). In the matched sample, GEE logistic regression accounting for within-pair correlation also confirmed no significant difference (OR 1.25 [0.74–2.12]; p = 0.386).

Table 5:

Pregnancy was defined as a positive serum β-hCG per cycle. Odds ratios (ORs) are reported for Letrozole + late-onset rFSH versus conventional rFSH (reference). Propensity scores were estimated using female age, anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), antral follicle count (AFC), basal follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) status. PSM used 1:1 nearest-neighbour matching without replacement with a caliper width of 0.2 standard deviations of the logit of the propensity score; covariate balance was assessed by standardized mean differences (SMD), with SMD <0.10 indicating adequate balance. Matched ORs and p-values were derived using McNemar’s exact test on discordant pairs. IPTW used stabilized ATE weights; ORs were estimated via weighted logistic regression with robust (sandwich) standard errors. Doubly robust estimates were obtained by IPTW-weighted outcome regression additionally adjusted for the same baseline covariates. GEE models accounted for within-pair correlation in the matched cohort (exchangeable correlation; robust standard errors). Risk differences (RDs) are expressed in percentage points (pp). Two-sided p-values are shown.

Despite a similar trigger timing (median 11 vs 11 days), the sequential letrozole + late-onset rFSH protocol required a substantially lower total gonadotropin dose (median 400 IU vs 750 IU; p<0.001), indicating a clinically meaningful gonadotropin-sparing effect and lower expected medication cost. Cycle cancellation rates were low in both groups (0.5% vs 2.2%; Fisher p = 0.058). OHSS could not be formally compared because an OHSS variable was not available in the exported dataset; therefore, safety inference is based on cancellation and downstream outcomes captured in the file.

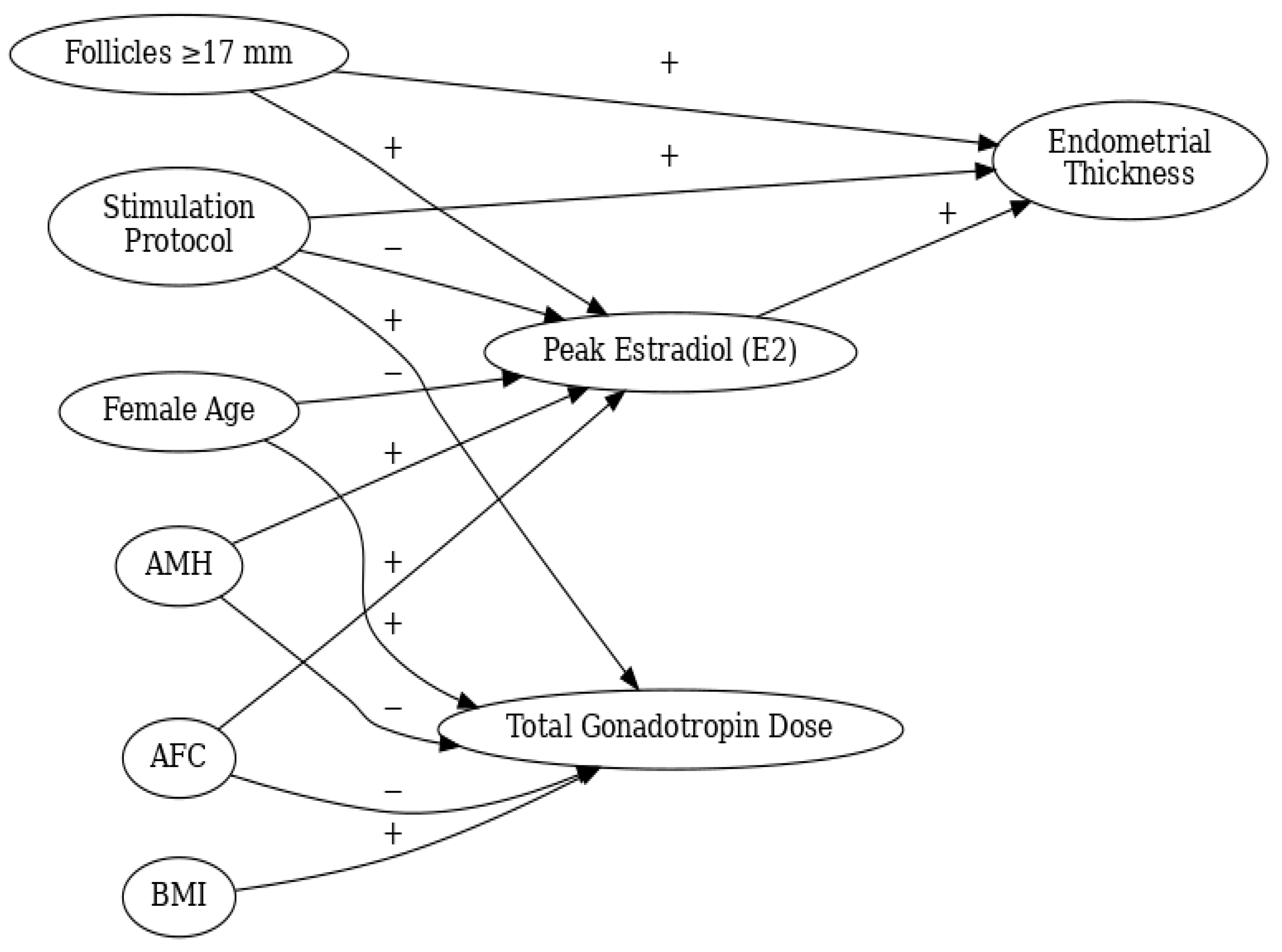

In mediation analyses

, endometrial thickness and peak estradiol did not demonstrate significant indirect effects on pregnancy, suggesting that protocol-related differences in these intermediate markers did not translate into measurable differences in pregnancy outcomes.

Figure 2:

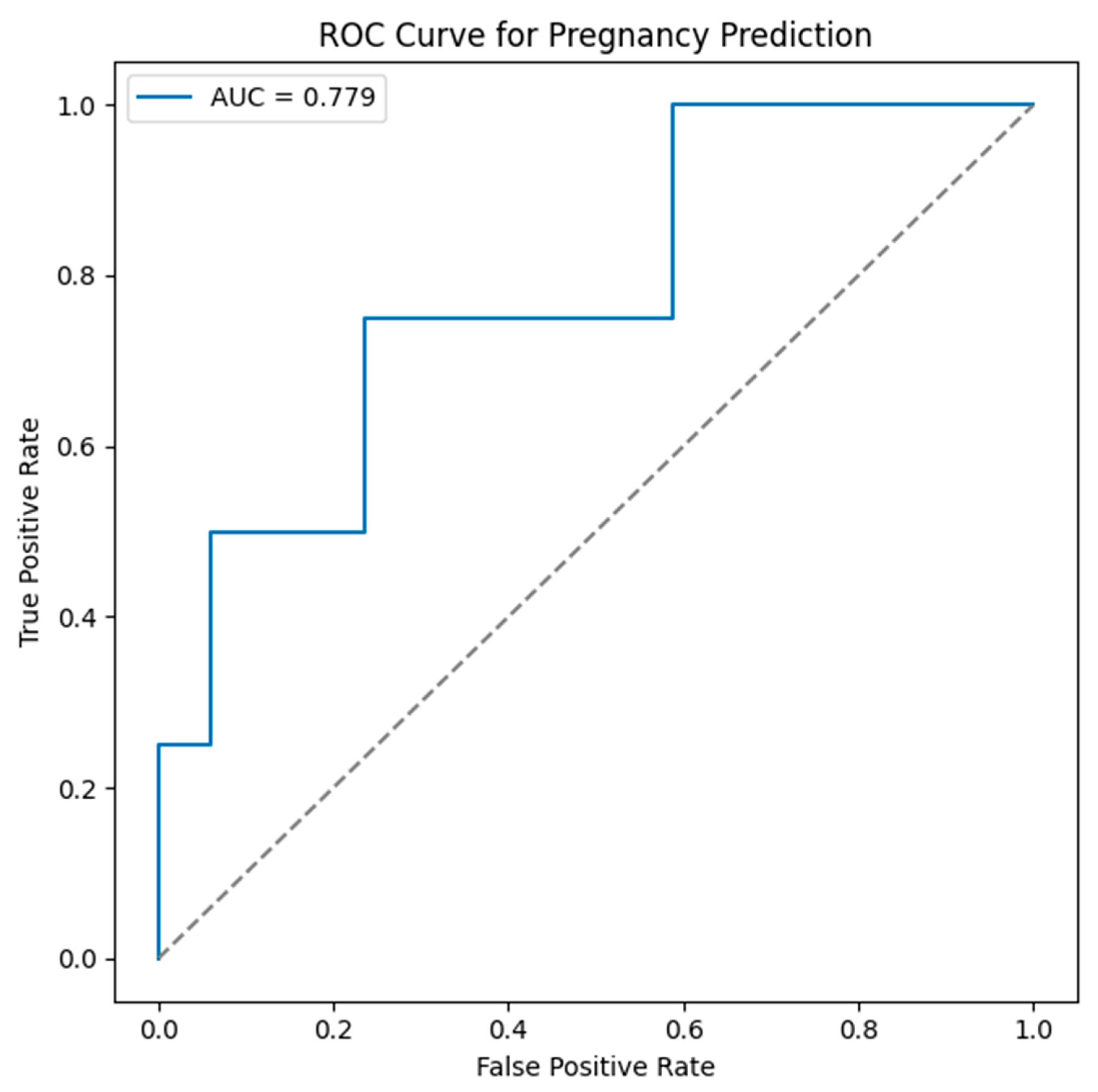

ROC analysis of the pregnancy prediction model including female age, AMH, and endometrial thickness showed moderate discrimination

(AUC = 0.779

). The optimal probability cut-off (Youden index) was 0.259, corresponding to sensitivity 0.75 and specificity 0.76

. The stimulation protocol was not included in the ROC model because it did not provide independent discriminatory value after confounding control.

Figure 3:

Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

The study’s strengths include a large cohort of 764 IUI cycles, providing strong statistical power and external validity, supported by various analytical methods that enhance causal inference. However, limitations include its retrospective design, which hinders definitive causal conclusions, potential residual confounding, and limitations in capturing long-term obstetric outcomes. The use of pregnancy per cycle as the primary outcome also raises concerns about generalizability due to the single-center nature of the research.

In this retrospective cohort of 764 IUI cycles, a sequential protocol using early letrozole followed by late-onset rFSH showed higher pregnancy rates in crude comparisons than conventional rFSH stimulation. However, after accounting for baseline prognostic differences using multivariable regression and causal-inference methods PSM, IPTW, and doubly robust estimation), the estimated protocol effect attenuated and was no longer statistically significant. This pattern is consistent with confounding by indication in routine fertility care, where stimulation choice is often tailored to ovarian reserve, PCOS phenotype, and perceived risk of over-response; imbalance in ovarian reserve markers such as AMH and antral follicle count can therefore materially inflate unadjusted contrasts between protocols [

16,

17,

18,

19]. While prior studies often reported higher crude pregnancy rates with gonadotropin-only stimulation compared to oral agents alone, our findings suggest that in routine practice, the apparent differences in protocols may reverse based on patient selection and ovarian reserve profiles. Additionally, these differences may diminish after adequately controlling for confounding factors [

5,

20,

21].

Clinically, the most actionable signal from our data is the gonadotropin-sparing profile of the sequential letrozole + late-onset rFSH strategy. While gonadotropin-stimulated IUI can improve fecundability compared with expectant management in selected populations, it carries higher medication burden and costs and may increase the probability of multifollicular recruitment in high-reserve patients[

5,

22,

23] . Mild-to-moderate stimulation approaches have therefore been advocated to optimize the balance between effectiveness, safety, and resource use in IUI[

5,

22,

23]. In this context, sequential letrozole–gonadotropin regimens have been proposed as a pragmatic means to reduce total gonadotropin exposure without compromising pregnancy outcomes, and prior studies using letrozole plus gonadotropins in IUI settings report broadly comparable reproductive outcomes under certain timing and dosing schemes[

24,

25]. Our findings align with this rationale: despite similar trigger timing and follicular response at trigger, total gonadotropin utilization was substantially reduced in the sequential group, implying lower expected medication costs and potentially improved access.

Safety considerations are central when selecting IUI stimulation protocols, particularly for women with PCOS or high ovarian reserve. Letrozole is well established for ovulation induction in PCOS and is recommended as a first-line agent based on superior live birth outcomes compared with clomiphene citrate [

26]. In our cohort, cycle cancellation was uncommon and did not suggest a clinically relevant feasibility or safety penalty with the sequential approach, including within higher-reserve phenotypes. Although OHSS is uncommon in IUI when mild stimulation and cancellation criteria are applied, retrospective datasets may incompletely capture OHSS events; therefore, inferences about safety should be interpreted alongside observable proxies such as cancellation rates, multifollicular recruitment, and multiple gestation outcomes[

5,

27].

Mechanistically, aromatase inhibition produces a transiently lower circulating estradiol milieu without prolonged estrogen receptor depletion, which may preserve endometrial receptivity relative to selective estrogen receptor modulators and supports the biological plausibility of letrozole-based strategies in IUI [

28]. Nevertheless, the clinical relevance of modest endometrial thickness differences—once minimal receptive thresholds are achieved—remains debated, and endometrial thickness has shown inconsistent predictive value across IUI/ART studies [

29]. In our analyses, protocol-related differences in intermediate variables (e.g., estradiol and endometrial thickness) did not translate into a statistically supported pathway to pregnancy, suggesting that overall reproductive potential and appropriate cycle feasibility are more influential determinants than small shifts in hormonal or endometrial parameters.

From a clinical perspective, propensity score analyses suggest that the observed intergroup differences are not predominantly influenced by the treatment protocol itself. Propensity score matching (PSM) accurately compares analogous patients at baseline, whereas inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) may induce instability with extreme scores. The data indicated that PSM achieved optimal equilibrium in essential prognostic factors, and pregnancy rates were comparable subsequent to matching. This corroborates the conclusion that the identified benefits stem from baseline disparities rather than treatment effectiveness. In general, when patients have similar baseline characteristics, decisions about stimulation strategies should be based on how easy they are to use, how safe they are, and how well they use resources, not on big differences in the chances of getting pregnant. [

18,

19].

Strengths of this study include the large real-world sample, detailed cycle-level data, and the use of multiple complementary analytic strategies to triangulate the protocol effect. Limitations include the retrospective single-center design, potential residual confounding from unmeasured factors (e.g., clinician preference, prior response history, adherence), and the primary endpoint of pregnancy per cycle rather than live birth. Future prospective studies that capture live birth and comprehensive obstetric/neonatal outcomes would strengthen clinical translation. Overall, our findings support individualized stimulation selection: sequential letrozole + late-onset rFSH appears to offer a gonadotropin-sparing alternative without evidence of compromised pregnancy outcomes after adjustment, particularly for patients in whom minimizing medication intensity is clinically desirable.

Clinical Implications and Individualized Treatment Strategies

These findings indicate that no single ovarian stimulation protocol is universally superior for all IUI patients, as treatment success mainly depends on individual factors like female age and ovarian reserve. While conventional rFSH stimulation shows better initial pregnancy rates, this does not hold after adjusting for baseline characteristics. The letrozole plus late-onset rFSH protocol can yield similar pregnancy outcomes in selected patients, with benefits in endometrial development and reduced estradiol exposure. This method is particularly advantageous for those at risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome or requiring a conservative approach, supporting the trend toward personalized ovarian stimulation based on patient-specific characteristics[

30,

31].

Conclusion

The implementation of early letrozole combined with late-onset rFSH in ovulation induction demonstrates improved pregnancy outcomes in IUI cycles, while significantly reducing gonadotropin usage. This approach minimizes treatment costs and pharmacological burden without compromising cycle success, maintaining similar ovulation induction durations and follicular responses compared to traditional rFSH protocols. It also presents a low cycle cancellation rate, indicating a favorable safety profile and reduced risk of ovarian hyperstimulation for women with PCOS or high AFC. Overall, the sequential letrozole + late rFSH method is validated as a cost-effective alternative to standard rFSH stimulation in IUI.

Author Contributions

E.Y, S.A, and U.Y. contributed to the conception and design of the study and drafted the manuscript. S.A. and E.Y. prepared all Figures. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Adana City Hospital Research Ethics Board (Approval number 898 and date of approval 20 November 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Written and verbal informed consent was obtained from all participating women prior to treatment.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the University of Health Sciences Adana City Hospital and all women who participated in the study for their valuable contributions and cooperation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Abbreviations:

ART – Assisted Reproductive Technologies

AMH – Anti-Müllerian Hormone

AFC – Antral Follicle Count

BMI – Body Mass Index

E2 – Estradiol

FSH – Follicle Stimulating Hormone

hCG – Human Chorionic Gonadotropin

IPTW – Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting

IU – International Unit

IUI – Intrauterine Insemination

IVF – In Vitro Fertilization

OHSS – Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome

PCOS -Polycystıc Ovary Syndrome

PSM – Propensity Score Matching

rFSH – Recombinant Follicle-Stimulating Hormone

TPMSC – Total Progressive Motile Sperm Count

References

- Boivin, J.; Bunting, L.; Collins, J.A.; Nygren, K.G. International estimates of infertility prevalence and treatment-seeking: potential need and demand for infertility medical care. Hum Reprod 2007, 22, 1506–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarenhas, M.N.; Flaxman, S.R.; Boerma, T.; Vanderpoel, S.; Stevens, G.A. National, regional, and global trends in infertility prevalence since 1990: a systematic analysis of 277 health surveys. PLoS Med 2012, 9, e1001356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intrauterine insemination. Hum Reprod Update 2009, 15, 265–277. [CrossRef]

- Cohlen, B.J. Should we continue performing intrauterine inseminations in the year 2004? Gynecol Obstet Invest 2005, 59, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantineau, A.E.; Cohlen, B.J.; Heineman, M.J. Ovarian stimulation protocols (anti-oestrogens, gonadotrophins with and without GnRH agonists/antagonists) for intrauterine insemination (IUI) in women with subfertility. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007, CD005356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamath, M.S.; Maheshwari, A.; Bhattacharya, S.; Lor, K.Y.; Gibreel, A. Oral medications including clomiphene citrate or aromatase inhibitors with gonadotropins for controlled ovarian stimulation in women undergoing in vitro fertilisation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017, 11, Cd008528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzick, D.S.; Carson, S.A.; Coutifaris, C.; Overstreet, J.W.; Factor-Litvak, P.; Steinkampf, M.P.; Hill, J.A.; Mastroianni, L., Jr.; Buster, J.E.; Nakajima, S.T. Efficacy of superovulation and intrauterine insemination in the treatment of infertility. New England Journal of Medicine 1999, 340, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessel, J.A.; Danhof, N.A.; van Eekelen, R.; Diamond, M.P.; Legro, R.S.; Peeraer, K.; D’Hooghe, T.M.; Erdem, M.; Dankert, T.; Cohlen, B.J.; et al. Ovarian stimulation strategies for intrauterine insemination in couples with unexplained infertility: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update 2022, 28, 733–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitwally, M.F.; Casper, R.F. Aromatase inhibition reduces the dose of gonadotropin required for controlled ovarian hyperstimulation. J Soc Gynecol Investig 2004, 11, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, R.F.; Mitwally, M.F. Aromatase inhibitors for ovulation induction. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2006, 91, 760–771. [Google Scholar]

- Casper, R.F. Letrozole versus clomiphene citrate: which is better for ovulation induction? Fertil Steril 2009, 92, 858–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legro, R.S.; Brzyski, R.G.; Diamond, M.P.; Coutifaris, C.; Schlaff, W.D.; Casson, P.; Christman, G.M.; Huang, H.; Yan, Q.; Alvero, R. Letrozole versus clomiphene for infertility in the polycystic ovary syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine 2014, 371, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizzi, F.J. Letrozole with or without gonadotropin as a first-line ovulation induction in anovulatory infertile women due to polycystic ovary syndrome. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research 2018, 11, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, S.; Kupesic-Plavsic, S.; Mulla, Z.D.; Dwivedi, A.K.; Crisp, Z.; Jose, J.; Noble, L.S. Ovulation induction and controlled ovarian stimulation using letrozole gonadotropin combination: A single center retrospective cohort study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2017, 218, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedaiwy, M.A.; Forman, R.; Mousa, N.A.; Al Inany, H.G.; Casper, R.F. Cost-effectiveness of aromatase inhibitor co-treatment for controlled ovarian stimulation. Human Reproduction 2006, 21, 2838–2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tal, R.; Seifer, D.B. Ovarian reserve testing: a user’s guide. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017, 217, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broer, S.L.; Broekmans, F.J.; Laven, J.S.; Fauser, B.C. Anti-Müllerian hormone: ovarian reserve testing and its potential clinical implications. Hum Reprod Update 2014, 20, 688–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, P.C. An Introduction to Propensity Score Methods for Reducing the Effects of Confounding in Observational Studies. Multivariate Behav Res 2011, 46, 399–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, E.A. Matching methods for causal inference: A review and a look forward. Stat Sci 2010, 25, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goverde, A.J.; McDonnell, J.; Vermeiden, J.P.; Schats, R.; Rutten, F.F.; Schoemaker, J. Intrauterine insemination or in-vitro fertilisation in idiopathic subfertility and male subfertility: a randomised trial and cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet 2000, 355, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeyneloglu, H.B.; Arici, A.; Olive, D.L.; Duleba, A.J. Comparison of intrauterine insemination with timed intercourse in superovulated cycles with gonadotropins: a meta-analysis. Fertil Steril 1998, 69, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- den Hartog, J.E.; Morre, S.A.; Land, J.A. Chlamydia trachomatis-associated tubal factor subfertility: Immunogenetic aspects and serological screening. Hum Reprod Update 2006, 12, 719–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, C.S.; Giovannucci, E.L.; Colditz, G.A.; Hunter, D.J.; Stampfer, M.J.; Rosner, B.; Speizer, F.E.; Willett, W.C. Dietary fiber and the risk of colorectal cancer and adenoma in women. N Engl J Med 1999, 340, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chason, R.J.; Levens, E.D.; Yauger, B.J.; Payson, M.D.; Cho, K.; Larsen, F.W. Balloon fluoroscopy as treatment for intrauterine adhesions: a novel approach. Fertil Steril 2008, 90, 2005 e2015–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessolle, L.; Biau, D. Proficiency in oocyte retrieval: how many procedures are necessary for training? Fertil Steril 2011, 96, e143; author reply e144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legro, R.S.; Brzyski, R.G.; Diamond, M.P.; Coutifaris, C.; Schlaff, W.D.; Casson, P.; Christman, G.M.; Huang, H.; Yan, Q.; Alvero, R.; et al. Letrozole versus clomiphene for infertility in the polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med 2014, 371, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smitz, J.; Dolmans, M.M.; Donnez, J.; Fortune, J.E.; Hovatta, O.; Jewgenow, K.; Picton, H.M.; Plancha, C.; Shea, L.D.; Stouffer, R.L.; et al. Current achievements and future research directions in ovarian tissue culture, in vitro follicle development and transplantation: implications for fertility preservation. Hum Reprod Update 2010, 16, 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.J.; Zhang, X.M.; Chiriboga, L.; Yee, H.; Perle, M.A.; Mittal, K. Spatial differences in biologic activity of large uterine leiomyomata. Fertil Steril 2006, 85, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasius, A.; Smit, J.G.; Torrance, H.L.; Eijkemans, M.J.; Mol, B.W.; Opmeer, B.C.; Broekmans, F.J. Endometrial thickness and pregnancy rates after IVF: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update 2014, 20, 530–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.H.; Speedy, S.E. The promised land of individualized ovarian stimulation: Are we there yet? Fertil Steril 2021, 115, 893–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauser, B.; Diedrich, K.; Devroey, P. Predictors of ovarian response: progress towards individualized treatment in ovulation induction and ovarian stimulation. Human reproduction update 2008, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).