Submitted:

01 January 2026

Posted:

05 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

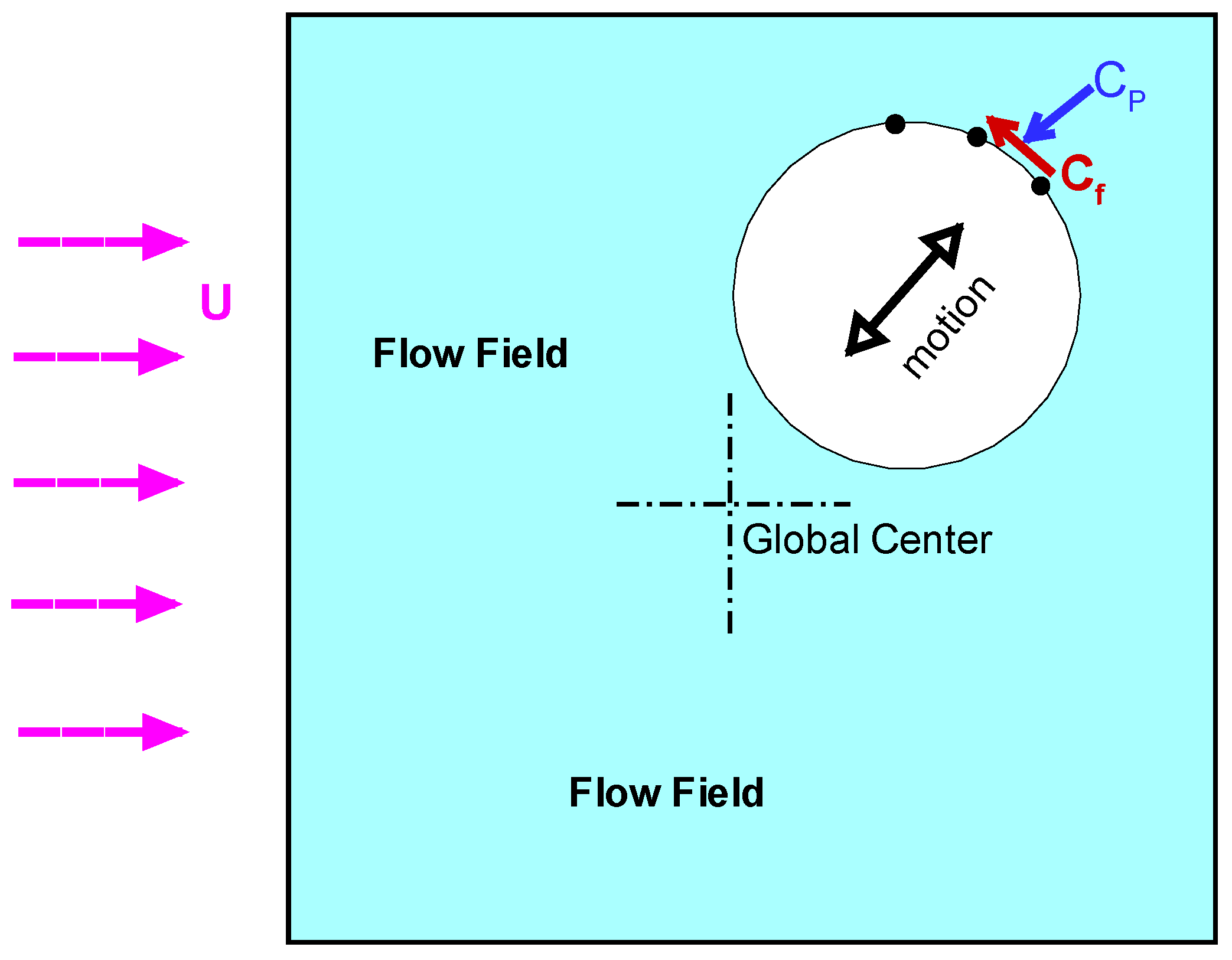

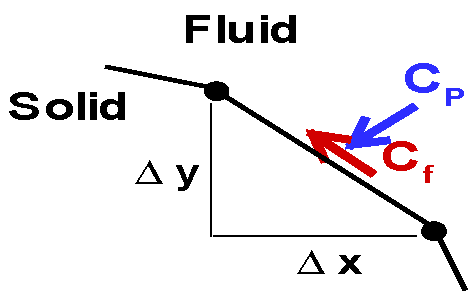

2. Flow Analysis

3. Model Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature (Greek Letters First)

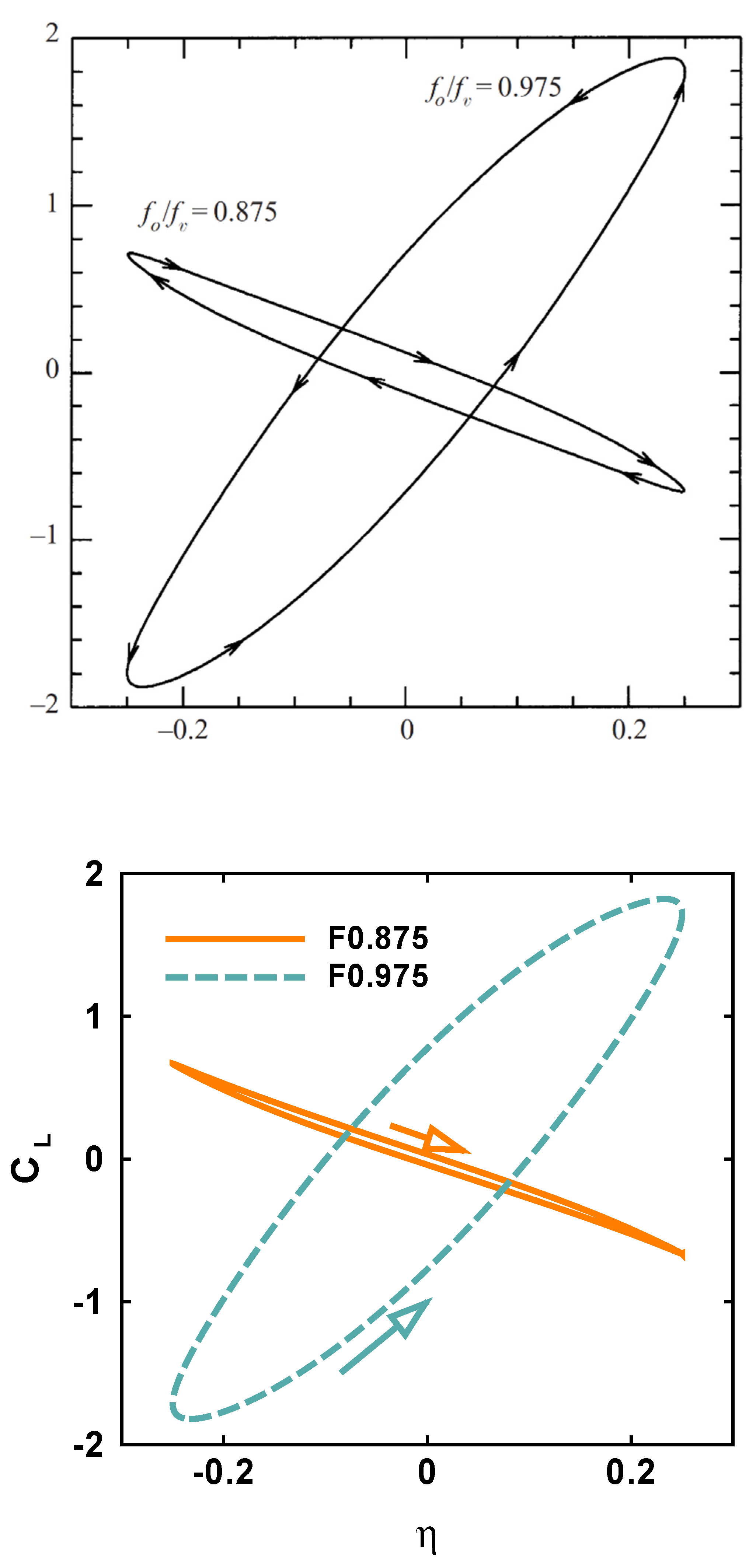

| η | Cross-stream displacement of the cylinder (expressed as a fraction of the cylinder diameter D) |

| ν | Kinematic viscosity of the fluid, ν = μ/ρ |

| ρ | Density of the fluid |

| μ | Dynamic viscosity of the fluid |

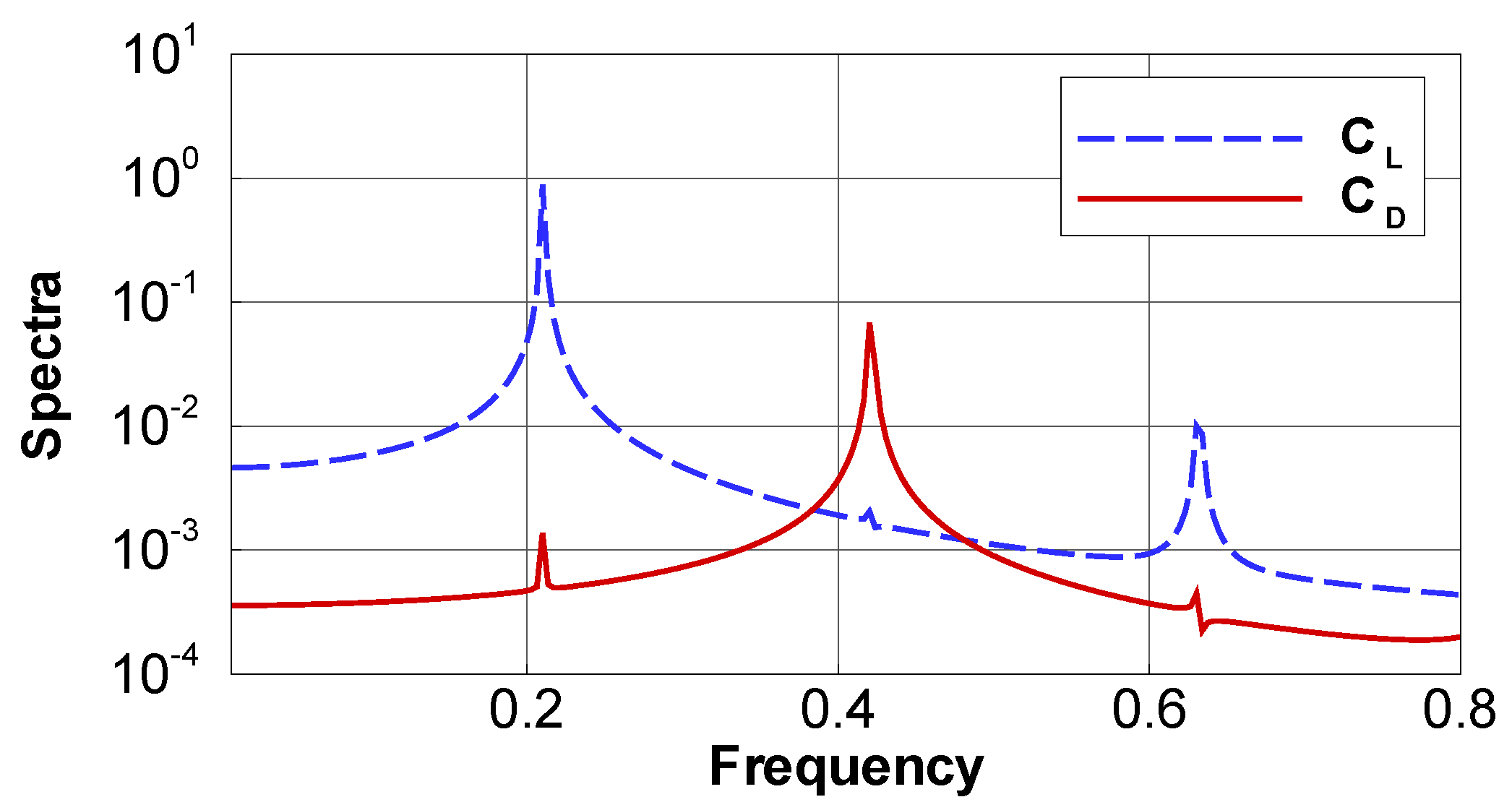

| Ω | Nondimensional angular frequency of the applied exciting harmonic vibration of the cylinder |

| ωS | Nondimensional Strouhal angular frequency (for a fixed cylinder), ωS = 2 π fS |

| ψ | Phase angle (angle of a frequency component relative to a1L) |

| a1L | Frequency component of CL at ωS (or Ω) |

| a2L | Frequency component of CL at 2 ωS (or 2 Ω) |

| a3L | Frequency component of CL at 3 ωS (or 3 Ω) |

| a1D | Frequency component of CD at ωS (or Ω) |

| a2D | Frequency component of CD at 2 ωS (or 2 Ω) |

| CD | Drag coefficient (time-dependent) |

| Cf | Friction coefficient (time-dependent) |

| CL | Lift coefficient (time-dependent) |

| CP | Pressure coefficient (time-dependent) |

| D | Diameter of the cylinder |

| L | Length of the cylinder (L =1 for the present two-dimensional flows) |

| fS | Nondimensional Strouhal cyclic frequency (for a fixed cylinder) |

| p | Pressure |

| Re | Reynolds number, Re = ρ U D/μ = U D/ν |

| U | Free-stream velocity |

References

- Odru, P.; Poirette, Y.; Stassen, Y.; Saint Marcoux, J. F.; Abergel, L. Composite Riser and Export Line Systems for Deep Offshore Applications; American Society of Mechanical Engineers Digital Collection, 2009; pp. 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, A.; Broglia, R.; Di Mascio, A.; Campana, E. F.; Rocco, P. Numerical Investigation of the Unsteady Flow at High Reynolds Number Over a Marine Riser With Helical Strakes; American Society of Mechanical Engineers Digital Collection, 2008; pp. 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. Proposed 2MW Wind Turbine for Use in Thumrait, Dhofar, Sultanate of Oman. Journal of Sustainable Energy Engineering 2019, 6(4), 252–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierella, F.; Sætran, L. Wind Tunnel Investigation on the Effect of the Turbine Tower on Wind Turbines Wake Symmetry. Wind Energy 2017, 20(10), 1753–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Al Badi, O. R. H.; Al Rashdi, M. H. S.; Al Balushi, H. M. E. Proposed 2MW Wind Turbine for Use in the Governorate of Dhofar at the Sultanate of Oman. Science Journal of Energy Engineering 2019, 7(2), 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R. L. A Numerical Analysis of the Flow Field Surrounding a Solar Chimney Power Plant. Master of Science in Engineering; Stellenbosch: University of Stellenbosch, University of Stellenbosch: South Africa, 2004. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10019.1/16337 (accessed on 2025-06-05).

- Gondchawar, A.; Kanabar, B.; Bhoraniya, R. Comprehensive Review of Hybrid Solar Updraft Tower Power Generation Systems for Electricity Production in Tropical Regions. Int J Energ Water Res 2025, 9(4), 2849–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papailiou, K. O. Overhead Lines. In Springer Handbook of Power Systems; Papailiou, K. O., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 611–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIver, C.; Cruden, A.; Leithead, W. E.; Bertinat, M. P. Effect of Wind Turbine Wakes on Wind-Induced Motions in Wood-Pole Overhead Lines. Wind Energy 2015, 18(4), 643–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, C.; Yang, Y.; Niu, K.; Xu, W.; Wang, D.; Zhang, L.; Chen, C.; Yang, Y.; Niu, K.; Xu, W.; Wang, D. Anti-Overturning Performance of Prefabricated Foundations for Distribution Line Poles. Buildings 2025, 15(15). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, A. D.; Gairola, A.; Ganju, E.; Gupta, A. Design Wind Loads on Reinforced Concrete Chimney—An Experimental Case Study. Procedia Engineering 2011, 14, 1252–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, Z.; Sun, X.; Su, N.; Peng, S. Interference Effects between Two Tall Chimneys on Wind Loads and Dynamic Responses. Journal of Wind Engineering and Industrial Aerodynamics 2020, 206, 104227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Al Kamzari, A. A.; Al-Hatmi, T. K.; Al Alawi, O. S.; Al-Zadjali, H. A.; Al Haseed, M. A.; Al Daqaq, K. H.; Al-Aliyani, A. R.; Al-Aliyani, A. N.; Al Balushi, A. A.; Al Shamsi, M. H. Energy Analyses for a Steam Power Plant Operating under the Rankine Cycle. In First International Conference on Engineering, Applied Sciences and Management (UoB-IEASMA 2021); Al Kalbani, A. S., Kanna, R., EP Rabai, L. B., Ahmad, S., Valsala, S., Eds.; IEASMA Consultants LLP: Virtual, 2021; pp 11–22.

- Marzouk, O. A. Expectations for the Role of Hydrogen and Its Derivatives in Different Sectors through Analysis of the Four Energy Scenarios: IEA-STEPS, IEA-NZE, IRENA-PES, and IRENA-1.5 °C. Energies 2024, 17(3), 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easter, N.; Gao, M.; Krishnamurthy, R. M.; Kompally, S.; Coates, T. Implication of Fractographic Analysis of the Crack in an Above Ground Pipeline—Potential Role of Hydrogen. OnePetro 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Marzouk, O. A. 2030 Ambitions for Hydrogen, Clean Hydrogen, and Green Hydrogen. Engineering Proceedings 2023, 56(1), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Solar Heat for Industrial Processes (SHIP): An Overview of Its Categories and a Review of Its Recent Progress. Solar 2025, 5(4), 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckling of Thin Metal Shells; Teng, J. G., Rotter, J. M., Eds.; CRC Press: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancourt-Tovar, M.; Cuan-Urquizo, E.; Roman-Flores, A. Design and Micro-Mechanics Characterization of Additively Manufactured Architected Cylindrical Structures. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences 2025, 294, 110199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Manthari, M. S.; Azeez, C.; Sankar, M.; Pushpa, B. V. Numerical Study of Laminar Flow and Vortex-Induced Vibration on Cylinder Subjects to Free and Forced Oscillation at Low Reynolds Numbers. Fluids 2024, 9(8), 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, P. J.; Hunt, B. L. Out-of-Plane Force on a Circular Cylinder at Large Angles of Inclination to a Uniform Stream. The Aeronautical Journal 1973, 77(745), 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civrais, C. H. B.; White, C.; Steijl, R. Influence of Anharmonic Oscillator Model for Flows over a Cylindrical Body. AIP Conference Proceedings 2024, 2996(1), 080008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Detailed and Simplified Plasma Models in Combined-Cycle Magnetohydrodynamic Power Systems. International Journal of Advanced and Applied Sciences 2023, 10(11), 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constante-Amores, C. R.; Linot, A. J.; Graham, M. D. Dynamics of a Data-Driven Low-Dimensional Model of Turbulent Minimal Pipe Flow. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2025, 1020, A58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Nayfeh, A. H. Control of Ship Roll Using Passive and Active Anti-Roll Tanks. Ocean Engineering 2009, 36(9), 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Reduced-Order Modeling (ROM) of a Segmented Plug-Flow Reactor (PFR) for Hydrogen Separation in Integrated Gasification Combined Cycles (IGCC). Processes 2025, 13(5), 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Kou, J.; Wang, Z. Nonlinear Aerodynamic Reduced-Order Model for Limit-Cycle Oscillation and Flutter. AIAA Journal 2016, 54(10), 3304–3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, R. E. D.; Hassan, A. Y. The Lift and Drag Forces on a Circular Cylinder in a Flowing Fluid. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A. Mathematical and Physical Sciences 1997, 277(1368), 32–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Urban Air Mobility and Flying Cars: Overview, Examples, Prospects, Drawbacks, and Solutions. Open Engineering 2022, 12(1), 662–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickery, B. J. Fluctuating Lift and Drag on a Long Cylinder of Square Cross-Section in a Smooth and in a Turbulent Stream. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 1966, 25(3), 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, D.-M.; Roh, T.-S.; Lee, H. J. Drag Reduction Effect by Counter-flow Jet on Conventional Rocket Configuration in Supersonic/Hypersonic Flow. Journal of Aerospace System Engineering 2020, 14(4), 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Massaro, D.; Karp, M.; Jansson, N.; Markidis, S.; Schlatter, P. Direct Numerical Simulation of the Turbulent Flow around a Flettner Rotor. Sci Rep 2024, 14(1), 3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, M.; Fakhri Vayqan, H.; Rabiee, A. H. Impact of Temperature-Induced Buoyancy on the 2DOF-VIV of a Heated/Cooled Cylinder. Arab J Sci Eng 2025, 50(4), 2807–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, T.; Shigeta, T.; Kasai, M.; Nonomura, T. Schlieren Visualization and Drag Measurement on Compressible Flow over a Circular Cylinder at Reynolds Number of $$\mathcal {O}(10^2)$$. Exp Fluids 2025, 66(5), 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, M. K.; Kang, C.-K.; Landrum, D. B.; Aono, H.; Mathis, S. L.; Lee, T. Effects of Flight Altitude on the Lift Generation of Monarch Butterflies: From Sea Level to Overwintering Mountain. Bioinspir. Biomim. 2021, 16(3), 034002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharrouba, M.; Pierson, J.-L.; Magnaudet, J. Flow Structure and Loads over Inclined Cylindrical Rodlike Particles and Fibers. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2021, 6(4), 044308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartlen, Ro. T.; Currie, I. G. Lift-Oscillator Model of Vortex-Induced Vibration. Journal of the Engineering Mechanics Division 1970, 96(5), 577–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, E. A. Low-Dimensional Control of the Circular Cylinder Wake. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 1998, 371, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leontini, J. S.; Jacono, D. L.; Thompson, M. C. A Numerical Study of an Inline Oscillating Cylinder in a Free Stream. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2011, 688, 551–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naudascher, E. Flow-Induced Streamwise Vibrations of Structures. Journal of Fluids and Structures 1987, 1(3), 265–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobari, M. R. H.; Naderan, H. A Numerical Study of Flow Past a Cylinder with Cross Flow and Inline Oscillation. Computers & Fluids 2006, 35(4), 393–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stansby, P. K. The Locking-on of Vortex Shedding Due to the Cross-Stream Vibration of Circular Cylinders in Uniform and Shear Flows. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 1976, 74(4), 641–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. A Flight-Mechanics Solver for Aircraft Inverse Simulations and Application to 3D Mirage-III Maneuver. Global Journal of Control Engineering and Technology 2015, 1, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Urso, B.; Van Handel, R.; Odom, B.; Hanneke, D.; Gabrielse, G. Single-Particle Self-Excited Oscillator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 94(11), 113002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappauf, J.; Hetzler, H. On a Hybrid Approximation Concept for Self-Excited Periodic Oscillations of Large-Scale Dynamical Systems. PAMM 2021, 21(1), e202100143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minorsky, N. Self-Excited Oscillations in Dynamical Systems Possessing Retarded Actions. J. Appl. Mech 2021, 9(2), A65–A71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skop, R. A.; Griffin, O. M. A Model for the Vortex-Excited Resonant Response of Bluff Cylinders. Journal of Sound and Vibration 1973, 27(2), 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blevins, R. D. Flow Induced Vibration of Bluff Structures. PhD in Engineering Mechanics, California Institute of Technology (Caltech): Pasadena, California, USA, 1974. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/bed7d14a974e2b448029fb25620d77f3 (accessed on 2025-06-03).

- Di Silvio, G.; Angrilli, F.; Zanardo, A. Fluidelastic Vibrations: Mathematical Model and Experimental Result. Meccanica 1975, 10(4), 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landl, R. A Mathematical Model for Vortex-Excited Vibrations of Bluff Bodies. Journal of Sound and Vibration 1975, 42(2), 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, I.; Scanlan, R. H.; Jones, N. P. Vortex-Induced Vibration of Circular Cylinders. II: New Model. Journal of Engineering Mechanics 1993, 119(11), 2288–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skop, R. A.; Balasubramanian, S. A New Twist on an Old Model for Vortex-Excited Vibrations. Journal of Fluids and Structures 1997, 11(4), 395–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenk, S.; Nielsen, S. R. K. Energy Balanced Double Oscillator Model for Vortex-Induced Vibrations. Journal of Engineering Mechanics 1999, 125(3), 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mureithi, N. W.; Goda, S.; Kanki, H.; Nakamura, T. A Nonlinear Dynamics Analysis of Vortex-Structure Interaction Models. Journal of Pressure Vessel Technology 2001, 123(4), 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchinetti, M. L.; de Langre, E.; Biolley, F. Coupling of Structure and Wake Oscillators in Vortex-Induced Vibrations. Journal of Fluids and Structures 2004, 19(2), 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.-J.; Perkins, N. C. Two-Dimensional Vortex-Induced Vibration of Cable Suspensions. Journal of Fluids and Structures 2002, 16(2), 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Cheng, L.; Tong, F. Hydrodynamic Force of an Obliquely Oscillating Cylinder in Steady Flow; American Society of Mechanical Engineers Digital Collection, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, E.; Zhao, M.; Wu, H.; Taheri, E.; Zhao, M.; Wu, H. Numerical Investigation of the Vibration of a Circular Cylinder in Oscillatory Flow in Oblique Directions. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2022, 10(6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. Q.; So, R. M. C.; Chan, K. T. A Non-Linear Fluid Force Model for Vortex-Induced Vibration of an Elastic Cylinder. Journal of Sound and Vibration 2003, 260(2), 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awrejcewicz, J. Resonance; 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, F.; Chaney, R.; Tseng, R. Resonance. In The Physics of Destructive Earthquakes; Morgan & Claypool Publishers: San Rafael, California, USA, 2018; Vol. The Physics of Destructive Earthquakes, pp. 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignolet, M.; Red-Horse, J. ARMAX Identification of Vibrating Structures—Model and Model Order Estimation. In 35th Structures, Structural Dynamics, and Materials Conference; 1994, AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics]: Hilton Head, South Carolina, USA; p. AIAA-94-1525-CP. [CrossRef]

- Chen-xu, N.; Jie-sheng, W. Auto Regressive Moving Average (ARMA) Prediction Method of Bank Cash Flow Time Series. In 2015 34th Chinese Control Conference (CCC); 2015, pp. 4928–4933. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L. Auto Regressive Moving Average (ARMA) Modeling Method for Gyro Random Noise Using a Robust Kalman Filter. Sensors 2015, 15(10), 25277–25286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, S.; Avital, E. J.; Williams, J. J. R.; Chatjigeorgiou, I. K. A Fluid–Structure Interaction (FSI) Solver for Evaluating the Impact of Circular Fish Swimming Patterns on Offshore Aquaculture. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2025, 237, 110625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarsenov, E.; Batay, S.; Baidullayeva, A.; Zhao, Y.; Wei, D.; Ng, E. Y. K.; Sarsenov, E.; Batay, S.; Baidullayeva, A.; Zhao, Y.; Wei, D.; Ng, E. Y. K. High Fidelity 2-Way Dynamic Fluid-Structure-Interaction (FSI) Simulation of Wind Turbines Based on Arbitrary Hybrid Turbulence Model (AHTM). Energies 2025, 18(16). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huera-Huarte, F. Vortex-Induced Vibration of Flexible Cylinders in Cross-Flow. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics 2025, 57((Volume 57), 285–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, T.; Dong, Y.; Frangopol, D. M.; Li, Z. Fatigue Reliability Assessment of Vortex-Induced Vibration for Long Flexible Cylinders Based on HOM-IMEM. Engineering Structures 2026, 348, 121802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xu, W.; Ma, Y. Vortex-Induced Vibration (VIV) Fatigue Damage Characteristics of Submarine Multispan Pipelines. Ocean Engineering 2025, 324, 120666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Tang, H.; Xie, L. A Deep Modal Model for Reconstructing the VIV Response of a Flexible Cylinder with Sparse Sensing Data. Ocean Engineering 2025, 326, 120871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. G.; Liu, Y.; Lu, J. Fluid–Structure Interaction of Single Flexible Cylinder in Axial Flow. Computers & Fluids 2012, 56, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, K.; Prethiv Kumar, R.; Nallayarasu, S.; Liu, Y. Frequency-Domain Analysis of Vortex-Induced Vibration of Flexible Cantilever Cylinder with Various Aspect Ratios. Ocean Engineering 2025, 320, 120204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCaria, V.; Iliescu, T.; Layton, W.; McLaughlin, M.; Schneier, M. An Artificial Compression Reduced Order Model. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 2020, 58(1), 565–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polifke, W. Black-Box System Identification for Reduced Order Model Construction. Annals of Nuclear Energy 2014, 67, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Sun, J.; Chang, X.; Zhang, W.; Arcucci, R.; Guo, Y.; Pain, C. C. Data-Driven Reduced Order Model with Temporal Convolutional Neural Network. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering 2020, 360, 112766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, R. Researching the Teaching-Research Nexus: A Critical Review. Australian Journal of Education 1996, 40(1), 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. University Role in Promoting Leadership and Commitment to the Community. In Inaugural International Forum on World Universities; Davos, Switzerland, 2008.

- Neumann, R. Perceptions of the Teaching-Research Nexus: A Framework for Analysis. High Educ 1992, 23(2), 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimmitt, N. THE POWER OF PROJECT BASED LEARNING: EXPERIENTIAL EDUCATION TO DEVELOP CRITICAL THINKING SKILLS FOR UNIVERSITY STUDENTS. CBU International Conference Proceedings 2017, 5, 575–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Jul, W. A. M. H. R.; Al Jabri, A. M. K.; Al-ghaithi, H. A. M. A. Construction of a Small-Scale Vacuum Generation System and Using It as an Educational Device to Demonstrate Features of the Vacuum. International Journal of Contemporary Education 2018, 1(2), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurdinger, S.; Qureshi, M. Enhancing College Students’ Life Skills through Project Based Learning. Innov High Educ 2015, 40(3), 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallar, B. L.; Kimber, M. L. Numerical Investigation of Force Coefficient Data for Multiple Flow Past Cylinder Configurations. In 10th Thermal and Fluids Engineering Conference (TFEC); 2025, Begel House Inc.: Washington, D.C., USA; pp. 469–478. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Validating a Model for Bluff-Body Burners Using the HM1 Turbulent Nonpremixed Flame. Journal of Advanced Thermal Science Research 2016, 3(1), 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, M. N.; Abuelyamen, A.; Parezanović, V. B.; Alkaabi, A. K.; Alameri, S. A.; Afgan, I. A Comprehensive Review, CFD and ML Analysis of Flow around Tandem Circular Cylinders at Sub-Critical Reynolds Numbers. Journal of Wind Engineering and Industrial Aerodynamics 2025, 257, 105998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Accurate Prediction of Noise Generation and Propagation. In 18th Engineering Mechanics Division Conference of the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE-EMD); 2007, Zenodo: Blacksburg, Virginia, USA; pp. 1–6.

- Grimm, V.; Heinlein, A.; Klawonn, A. Learning the Solution Operator of Two-Dimensional Incompressible Navier-Stokes Equations Using Physics-Aware Convolutional Neural Networks. Journal of Computational Physics 2025, 535, 114027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, K. A.; Chiang, S. T. Computational Fluid Dynamics—Volume 1, 4. ed., 2. print.; Engineering Education System: Wichita, Kansas, USA, 2004.

- Zhang, Y.; Rabczuk, T.; Lin, J.; Lu, J.; Chen, C. S. Numerical Simulations of Two-Dimensional Incompressible Navier-Stokes Equations by the Backward Substitution Projection Method. Applied Mathematics and Computation 2024, 466, 128472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparrow, E. M.; Cess, R. D. Temperature-Dependent Heat Sources or Sinks in a Stagnation Point Flow. Appl. sci. Res. 1961, 10(1), 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Feng, X.; Yang, X.; Shen, Y.; Zhao, H.; Bai, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhang, T.; Zheng, X. Near-Field Thermal Radiation for Enhanced Heat Transfer: Classification, Challenges, and Prospects. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2025, 218, 115836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Temperature-Dependent Functions of the Electron–Neutral Momentum Transfer Collision Cross Sections of Selected Combustion Plasma Species. Applied Sciences 2023, 13(20), 11282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoranz, A.; Flores, O.; García-Villalba, M. Turbulent Heat Transfer and Secondary Flows in a Non-Uniformly Heated Pipe with Temperature-Dependent Fluid Properties. International Journal of Heat and Fluid Flow 2025, 115, 109791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhuri, N. J. P.; Shamshuddin, MD.; Salawu, S. O. Finite Element Simulation of Magneto-Thermal Transport in Hybrid Nanofluid Flow over a Rotating Disk Influenced by Ohmic Heating. J Therm Anal Calorim 2025, 150(23), 19605–19621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dondapati, R. S.; Rao, V. V. CFD Analysis of Cable-In-Conduit Conductors (CICC) for Fusion Grade Magnets. IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity 2012, 22(3), 4703105–4703105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Airfoil Design Using Genetic Algorithms. In The 2007 International Conference on Scientific Computing (CSC’07), The 2007 World Congress in Computer Science, Computer Engineering, and Applied Computing (WORLDCOMP’07); 2007, CSREA Press: Las Vegas, Nevada, USA; pp. 127–132.

- Hah, C. A Numerical Modeling of Endwall and Tip-Clearance Flow of an Isolated Compressor Rotor. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 1986, 108(1), 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, D. Numerical Simulation of Flow around a Transversely Oscillating Square Cylinder at Different Frequencies. Physics of Fluids 2025, 37(2), 025213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moin, P.; Mahesh, K. DIRECT NUMERICAL SIMULATION: A Tool in Turbulence Research. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics 1998, 30((Volume 30), 539–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. OpenFOAM Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) Solver for Magnetohydrodynamic Open Cycles, Applied to the Sakhalin Pulsed Magnetohydrodynamic Generator (PMHDG). Discover Applied Sciences 2025, 7(10), 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, B.; Özbey, M. Numerical Investigation of Friction Behavior in Microchannels with Hydrophobic Surface Properties Using VOF Model. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part E: Journal of Process Mechanical Engineering 2025, 09544089251374743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, R.; Vaessen, F. A New Compressibility Correction Method to Predict Aerodynamic Interaction between Lifting Surfaces. In 2013 Aviation Technology, Integration, and Operations Conference; 2013, AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics]: Los Angeles, California, USA; p. AIAA 2013-4299. [CrossRef]

- Sultanian, B. K. Fluid Mechanics and Turbomachinery: Problems and Solutions; CRC Press: Boca Raton, Florida, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaguti, M.; Jain, P. Numerical Study of a Viscous Fluid Flow Past a Circular Cylinder. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1966, 21(10), 2055–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowdy, D. G. Analytical Solutions for Uniform Potential Flow Past Multiple Cylinders. European Journal of Mechanics—B/Fluids 2006, 25(4), 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Seo, J.; Lee, I. A U-Net Based Reconstruction of High-Fidelity Simulation Results for Flow around a Ship Hull Based on Low-Fidelity Inviscid Flow Simulation. International Journal of Naval Architecture and Ocean Engineering 2025, 17, 100676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, K. A Method for Applying Viscous Corrections to Inviscid CFD Solutions for Engineering Applications Using Cart3D. In AIAA SCITECH 2025 Forum; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Orlando, Florida, USA, 2025; pp. AIAA 2025–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, W. Euler Equation Embedded Machine Learning Method for Wall Pressure and Skin Friction Distribution. Engineering Applications of Computational Fluid Mechanics 2025, 19(1), 2556450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. A Two-Step Computational Aeroacoustics Method Applied to High-Speed Flows. Noise Control Engineering Journal 2008, 56(5), 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pindado, S.; Meseguer, J. Wind Tunnel Study on the Influence of Different Parapets on the Roof Pressure Distribution of Low-Rise Buildings. Journal of Wind Engineering and Industrial Aerodynamics 2003, 91(9), 1133–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Assessment of Global Warming in Al Buraimi, Sultanate of Oman Based on Statistical Analysis of NASA POWER Data over 39 Years, and Testing the Reliability of NASA POWER against Meteorological Measurements. Heliyon 2021, 7(3), e06625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batten, W. M. J.; Bahaj, A. S.; Molland, A. F.; Chaplin, J. R. Hydrodynamics of Marine Current Turbines. Renewable Energy 2006, 31(2), 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, D. E. Fluid Biomechanics. In Nature’s Machines; Elsevier, 2017; pp. 51–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kida, S.; Miura, H. Swirl Condition in Low-Pressure Vortices. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1998, 67(7), 2166–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kida, S.; Goto, S.; Makihara, T. Low-Pressure Vortex Analysis in Turbulence: Life, Structure, and Dynamical Role of Vortices. In Tubes, Sheets and Singularities in Fluid Dynamics; Bajer, K., Moffatt, H. K., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2002; pp. 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razumnaya, A.; Tikhonov, Y.; Naidenko, D.; Linnik, E.; Lukyanchuk, I.; Razumnaya, A.; Tikhonov, Y.; Naidenko, D.; Linnik, E.; Lukyanchuk, I. Bernoulli Principle in Ferroelectrics. Nanomaterials 2025, 15(13). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidora, G.; Haley, A. L.; Cancelliere, N. M.; Pereira, V. M.; Steinman, D. A. Back to Bernoulli: A Simple Formula for Trans-Stenotic Pressure Gradients and Retrospective Estimation of Flow Rates in Cerebral Venous Disease. Journal of NeuroInterventional Surgery 2025, 17(9), 1005–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zdravkovich, M. Conceptual Overview of Laminar and Turbulent Flows Past Smooth and Rough Circular Cylinders. Wind Engineers, JAWE 1988, 1988(37), 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakeri, P.; Moschopoulos, P.; Dimakopoulos, Y.; Tsamopoulos, J. Scaling Analysis and Self-Similarity near Breakup of Elasto-Viscoplastic Liquid Threads under Creeping Flow. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2025, 1020, A37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guohui, H.; Dejun, S.; Xieyuan, Y. On the Topological Bifurcation of Flows around a Rotating Circular Cylinder. Acta Mech Sinica 1997, 13(3), 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wu, J. Flow-Induced Reconfiguration of and Force on Elastic Cantilevers. In Proceedings of the IUTAM Symposium on Turbulent Structure and Particles-Turbulence Interaction; Zheng, X., Balachandar, S., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 229–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, C.; Agrawal, R.; Wu, X. Correlation for Transitional Reynolds Number and Assessment of RANS for Bypass Transition. J. Fluids Eng 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P. Transition Reversal over a Blunt Plate at Mach 5. Part 2. The Role of Free-Stream-Disturbance Form. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2025, 1025, A54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmkuhl, O.; Rodríguez, I.; Borrell, R.; Chiva, J.; Oliva, A. Unsteady Forces on a Circular Cylinder at Critical Reynolds Numbers. Physics of Fluids 2014, 26(12), 125110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowen, F. E.; Perkins, E. W. DRAG OF CIRCULAR CYLINDERS FOR A WIDE RANGE OF REYNOLDS NUMBERS AND MACH NUMBERS; RESEARCH MEMORANDUM RM A52C20; NACA [United States National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics]: Washington, D.C, USA, 1952; pp. 1–28. Available online: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/19930087134/downloads/19930087134.pdf (accessed on 2025-11-06).

- Kološ, I.; Michalcová, V.; Lausová, L. Numerical Analysis of Flow Around a Cylinder in Critical and Subcritical Regime. Sustainability 2021, 13(4), 2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, Md. M.; Sakamoto, H. Investigation of Strouhal Frequencies of Two Staggered Bluff Bodies and Detection of Multistable Flow by Wavelets. Journal of Fluids and Structures 2005, 20(3), 425–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okajima, A. Strouhal Numbers of Rectangular Cylinders. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 1982, 123, 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, Q.; Huang, B.; Ouyang, Y. Adaptive ANCF Method Described by Arbitrary Lagrange-Euler Formulation with Application in Variable-Length Underwater Tethered Systems Moving in Limited Spaces. Ocean Engineering 2024, 297, 117059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Flow Control Using Bifrequency Motion. Theoretical and Computational Fluid Dynamics 2011, 25(6), 381–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Ma, S.; Qiu, W. Optimal Convergence of the Arbitrary Lagrangian–Eulerian Interface Tracking Method for Two-Phase Navier–Stokes Flow without Surface Tension. IMA Journal of Numerical Analysis 2025, draf003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Contrasting the Cartesian and Polar Forms of the Shedding-Induced Force Vector in Response to 12 Subharmonic and Superharmonic Mechanical Excitations. Fluid Dynamics Research 2010, 42(3), 035507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Levelized Cost of Green Hydrogen (LCOH) in the Sultanate of Oman Using H2A-Lite with Polymer Electrolyte Membrane (PEM) Electrolyzers Powered by Solar Photovoltaic (PV) Electricity. E3S Web of Conferences 2023, 469, 00101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, P. Computational Methods for Heat and Mass Transfer; Taylor & Francis: New York City, New York, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, S.; G, B. Benchmarking in CFD; American Society of Mechanical Engineers Digital Collection, 2009; pp. 1221–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, H. M.; Henderson, R. D. A Study of Two-Dimensional Flow Past an Oscillating Cylinder. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 1999, 385, 255–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhrawy, A. H.; Baleanu, D. A Spectral Legendre–Gauss–Lobatto Collocation Method for a Space-Fractional Advection Diffusion Equations with Variable Coefficients. Reports on Mathematical Physics 2013, 72(2), 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshko, A. On the Development of Turbulent Wakes from Vortex Streets; Technical Note NACA-TN-2913; NACA [United States National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics]. Washington, D.C., USA, 1953; pp. 1–77. Available online: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/19930083620/downloads/19930083620.pdf (accessed on 2025-06-03).

- Wen, C.-Y.; Yeh, C.-L.; Wang, M.-J.; Lin, C.-Y. On the Drag of Two-Dimensional Flow about a Circular Cylinder. Physics of Fluids 2004, 16(10), 3828–3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J. S.; Hanratty, T. J. Numerical Solution for the Flow around a Cylinder at Reynolds Numbers of 40, 200 and 500. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 1969, 35(2), 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, A. A.; Ferreira, J. M.; Chhabra, R. P. Steady Two-Dimensional Non-Newtonian Flow Past an Array of Long Circular Cylinders up to Reynolds Number 500: A Numerical Study. The Canadian Journal of Chemical Engineering 2005, 83(3), 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L. Development of Reduced-Order Models for Lift and Drag on Oscillating Cylinders with Higher-Order Spectral Moments. PhD in Engineering Mechanics, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (Virginia Tech), Blacksburg, Virginia, USA, 2004. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10919/29542 (accessed on 2025-06-03).

- Kuznetsov, A. P.; Sedova, Y. V.; Stankevich, N. V. Coupled Systems with Quasi-Periodic and Chaotic Dynamics. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 2023, 169, 113278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Liu, J. M. Chaotic Pulsing and Quasi-Periodic Route to Chaos in a Semiconductor Laser with Delayed Opto-Electronic Feedback. IEEE Journal of Quantum Electronics 2001, 37(3), 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Lu, M.; Ben-Jacob, E.; Onuchic, J. N. Periodic, Quasi-Periodic and Chaotic Dynamics in Simple Gene Elements with Time Delays. Sci Rep 2016, 6(1), 21037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modarres-Sadeghi, Y. Flow Around a Fixed Cylinder. In Introduction to Fluid-Structure Interactions; Modarres-Sadeghi, Y., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, R. A Study of Locking Phenomena in Oscillators. Proceedings of the IEEE 1973, 61(10), 1380–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, K. On the Period-Adding Phenomena at the Frequency Locking in a One-Dimensional Mapping. Prog Theor Phys 1982, 68(2), 669–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Huckaby, E. D. A Comparative Study of Eight Finite-Rate Chemistry Kinetics for CO/H2 Combustion. Engineering Applications of Computational Fluid Mechanics 2010, 4(3), 331–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, P.; Tognaccini, R. Turbulence Modeling for Low-Reynolds-Number Flows. AIAA Journal 2010, 48(8), 1673–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Z.; Cheng, L. Numerical Simulation of Three-Dimensional Flow around a Rectangular Cylinder. In Computational Fluid Dynamics 2002; Armfield, S. W., Morgan, P., Srinivas, K., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2003; pp. 775–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bookey, P.; Wyckham, C.; Smits, A.; Martin, P. New Experimental Data of STBLI at DNS/LES Accessible Reynolds Numbers. In 43rd AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit; 2005, AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics]: Reno, Nevada, USA; p. AIAA 2005-309. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yeo, K. S.; Khoo, B. C. DNS of Low Reynolds Number Turbulent Flows in Dimpled Channels. Journal of Turbulence 2006, 7, N37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Huckaby, E. D. Simulation of a Swirling Gas-Particle Flow Using Different k-Epsilon Models and Particle-Parcel Relationships. Engineering Letters 2010, 18(1). [Google Scholar]

- Freskos, G.; Penanhoat, O. Numerical Simulation of the Flow Field Around Supersonic Air-Intakes. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 1994, 116(1), 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Newman, J. C.; Anderson, W. K. A Streamline/Upwind Petrov Galerkin Overset Grid Scheme for the Navier-Stokes Equations with Moving Domains. In 32nd AIAA Applied Aerodynamics Conference; 2014, American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Atlanta, Georgia, USA; pp. AIAA 2014–2980. [CrossRef]

- Franke, R.; Rodi, W.; Schönung, B. Numerical Calculation of Laminar Vortex-Shedding Flow Past Cylinders. Journal of Wind Engineering and Industrial Aerodynamics 1990, 35, 237–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Fang, S.; Du, X. Flow around Square, Rounded, and Round-Convex Cylinders at Reynolds Numbers 20 to 22,000. Computers & Fluids 2025, 300, 106771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zhu, Y.; Hu, J.; Principe, J. C. System Parameter Identification: Information Criteria and Algorithms, 1st ed.; Elsevier: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mariotti, A.; Galletti, C.; Brunazzi, E.; Salvetti, M. V. Mixing Sensitivity to the Inclination of the Lateral Walls in a T-Mixer. Chemical Engineering and Processing—Process Intensification 2022, 170, 108699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Tilt Sensitivity for a Scalable One-Hectare Photovoltaic Power Plant Composed of Parallel Racks in Muscat. Cogent Engineering 2022, 9(1), 2029243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, C.; Hamada, A.; Ikuta, Y.; Shige, S.; Yamaji, M.; Tsuji, H.; Kubota, T.; Takayabu, Y. N. Spectral Latent Heating Retrieval for the Midlatitudes Using GPM DPR. Part I: Construction of Lookup Tables. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Chen, X.; Chen, H.; Song, S.; Li, S.; Hong, T.; Song, Z. Lookup Table-Based Computing: A Survey from Software Implementations to Hardware Architectures. ACM Comput. Surv. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppa, S.; Kaiktsis, L.; Frouzakis, C. E.; Triantafyllou, G. S. Computational Study of Three-Dimensional Flow Past an Oscillating Cylinder Following a Figure Eight Trajectory. Fluids 2021, 6(3), 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagat, K. C.; Soren, S. K.; Chaudhary, S. K. EXPERIMENTAL AND NUMERICAL ANALYSIS OF DIFFERENT AERODYNAMIC PROPERTIES OF CIRCULAR CYLINDER. International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology 2016, 3(9), 1112–1117. [Google Scholar]

- Prosser, D.; Smith, M. Aerodynamics of Finite Cylinders in Quasi-Steady Flow. In 53rd AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting; AIAA SciTech Forum; 2015, AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics]: Kissimmee, Florida, USA; p. AIAA 2015-1931. [CrossRef]

- Chabert d’Hières, G.; Davies, P. A.; Didelle, H. Experimental Studies of Lift and Drag Forces upon Cylindrical Obstacles in Homogeneous, Rapidly Rotating Fluids. Dynamics of Atmospheres and Oceans 1990, 15(1), 87–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, P. J.; Rand, D. A. Bifurcations of the Forced van Der Pol Oscillator. Quart. Appl. Math. 1978, 35(4), 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, R. S.; Machado, J. A. T.; Vinagre, B. M.; Calderón, A. J. Analysis of the Van Der Pol Oscillator Containing Derivatives of Fractional Order. Journal of Vibration and Control 2007, 13(9–10), 1291–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrón, M. A.; Sen, M. Synchronization of Four Coupled van Der Pol Oscillators. Nonlinear Dyn 2009, 56(4), 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cveticanin, L. On the Van Der Pol Oscillator: An Overview. Applied Mechanics and Materials 2013, 430, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mettin, R.; Parlitz, U.; Lauterborn, W. Bifurcation Structure of the Driven van Der Pol Oscillator. Int. J. Bifurcation Chaos 1993, 03(06), 1529–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacic, I. On the Motion of a Generalized van Der Pol Oscillator. Communications in Nonlinear Science and Numerical Simulation 2011, 16(3), 1640–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Mondal, J.; Chatterjee, S. Controlling Self-Excited Vibration Using Positive Position Feedback with Time-Delay. J Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2020, 42(9), 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Langre, E. Frequency Lock-in Is Caused by Coupled-Mode Flutter. Journal of Fluids and Structures 2006, 22(6), 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainal, A. A.; Ling, C. C. D.; Faisal, S. Y. Bifurcation of Rupture Path by Nonlinear Damping Force. Appl. Math. Mech.-Engl. Ed. 2011, 32(3), 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupi, F.; Niemann, H.-J.; Höffer, R. Aerodynamic Damping Model in Vortex-Induced Vibrations for Wind Engineering Applications. Journal of Wind Engineering and Industrial Aerodynamics 2018, 174, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitsev, S.; Shtempluck, O.; Buks, E.; Gottlieb, O. Nonlinear Damping in a Micromechanical Oscillator. Nonlinear Dyn 2012, 67(1), 859–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinett, I.; Rush, D.; Wilson, D. G. What Is a Limit Cycle? International Journal of Control 2008, 81(12), 1886–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.-M.; Yin, L.; Ao, P. Limit Cycle and Conserved Dynamics. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 2006, 20(07), 817–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thothadri, M.; Moon, F. C. Nonlinear System Identification of Systems with Periodic Limit-Cycle Response. Nonlinear Dyn 2005, 39(1), 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).