Submitted:

01 January 2026

Posted:

04 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

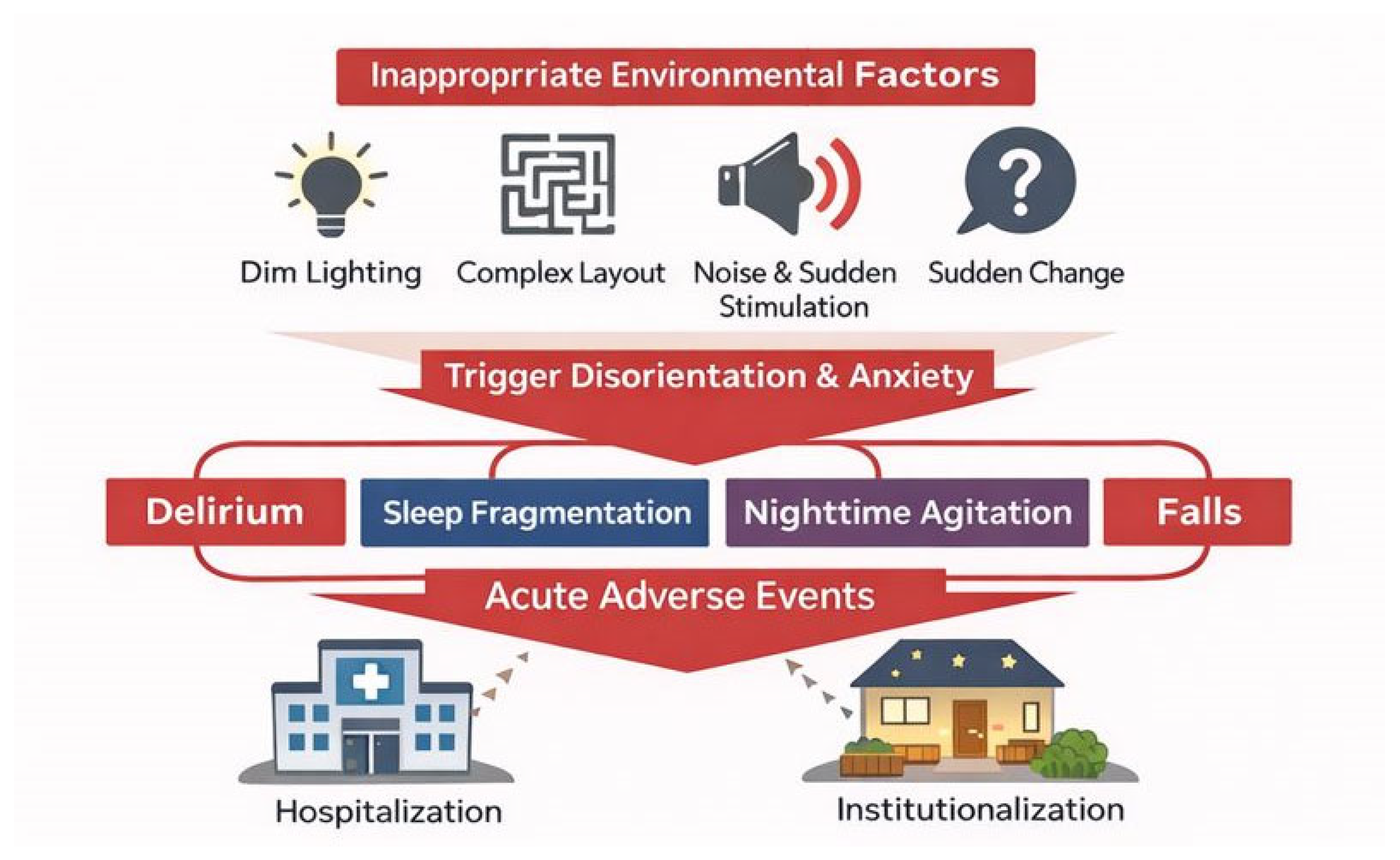

1.1. Redefining the "Environment" in Dementia Care

1.2. Limitations of Conventional Environmental Design Approaches

- Major renovations or dedicated equipment are feasible.

- Caregivers are consistently able to optimize environmental conditions.

- The person with dementia can understand and adapt to changes in the environment.

2. Constraints on Environmental Interventions in Dementia Care

2.1. Cognitive Constraints: Impaired Processing of Temporal and Spatial Cues

2.2. Emotional and Behavioral Constraints: Overstimulation and Reactive BPSD

2.3. Implementation Constraints: Person-Dependent Environmental Management

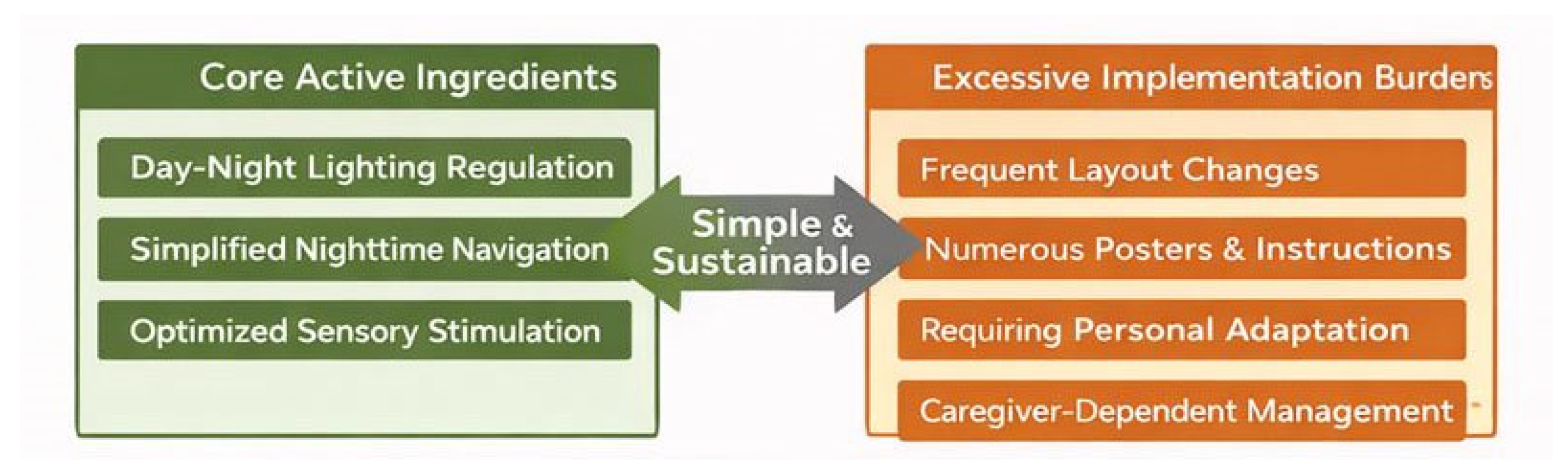

3. Differentiating Core Active Ingredients from Excessive Implementation Burdens

3.1. Core Active Ingredients in Environmental Interventions

- Lighting that clarifies temporal cues for day and night

- Simplification of nighttime pathways and assurance of visibility

- Optimization of sensory stimulation

3.2. Implementation Burdens to Be Eliminated

- Frequent rearrangement of furniture or layout

- Excessive signage and information displays

- Requiring the person with dementia to understand and adapt to environmental changes

- Management dependent on caregiver attention and vigilance

4. Dementia-Adapted Minimal Environmental Intervention Model

4.1. Minimal Component ①: Bright Days, Dark Nights

- Daytime: Maximize natural light and maintain sufficient indoor brightness.

- Nighttime: Use minimal lighting only to ensure footpath visibility.

4.2. Minimal Component ②: Fixed Nighttime Pathways

- Establish a consistent route from bed to toilet.

- Avoid rearranging furniture.

4.3. Minimal Component ③: Reduced Sensory Load

- Avoid keeping the television on continuously or at high volume.

- Minimize nighttime verbal interactions and sudden physical contact.

5. Implementation Protocol (Summary)

- Frequency: Continuous (applied at all times)

- Responsible party: The environment itself (do not place responsibility on the person with dementia)

- Inspection: Simple weekly checks

6. Implications for Research, Practice, and Policy

7. Conclusion

Appendix

- Care workers engaged in facility-based or home-based dementia care

- Family caregivers supporting individuals with dementia

- Medical and welfare professionals seeking to integrate environmental adjustments into daily care without excessive burden

- Individuals with mild to moderate dementia

- Individuals prone to instability in orientation to time, place, or situation

- Individuals exhibiting nighttime agitation, falls, delirium, or hypersensitivity to sensory stimuli

- Persistent severe agitation or aggression, where environmental adjustments alone are insufficient to ensure safety

- Medically unstable conditions such as acute delirium, infection, or severe pain

- Situations where acute-phase medical symptoms requiring clinical judgment take priority

- Do not require the individual to understand, learn, or adapt to the environment

- Avoid interventions that rely on explanations, memory, or judgment

- Avoid sudden stimuli or environmental changes

- If anxiety, confusion, or fear reactions are observed, reduce or stop the intervention immediately

- Keep lighting, pathways, and layout as fixed and consistent as possible

- Do not create environments that change from day to day

- Do not rely on the individual’s attention, judgment, or effort

- Aim to create a state in which “safety is ensured even if the person does nothing”

- Environmental adjustments: Applied continuously

- Inspection and confirmation: Simple checks conducted approximately once per week

- The individual's familiar living environment

- Does not assume major renovations or the use of special equipment

- Makes use of existing resources such as furniture, lighting, and acoustic conditions

- Prevent day-night reversal, nighttime agitation, and delirium

- Support the stabilization of circadian rhythms

- During the daytime, ensure the environment is as bright as possible, using natural and indoor light

- During the nighttime, avoid excessive lighting and use only minimal foot-level lighting as needed

- Do not suddenly switch on ceiling lights at night

- Avoid frequent changes to the color or position of lighting

- Prevent falls, disorientation, and anxiety reactions during the night:

- Fix the route from bed to toilet

- Remove obstacles from walkways

- Install minimal lighting that allows clear visibility of the floor

- Frequent rearrangement of furniture layout

- Temporarily placing objects along the walking path

- Prevent the onset of BPSD, delirium, and anxiety reactions

- Avoid leaving the TV or radio on continuously or at high volume

- Reduce sudden verbal interactions or physical contact during the night

- Minimize unpredictable sounds and light stimuli

- It is not necessary to enforce total silence

- The problems arise from stimuli that are:

- Explaining the reasons for environmental changes and expecting the individual to understand

- Using signs, labels, or notices as cognitive compensation

- Safety measures that depend on the individual's attention or judgment

- Frequent redecorating or rearranging of furniture

- Light intensity (may be reduced if needed)

- Level of sensory stimulation (sound, light, human traffic)

- Degree of pathway simplification

- Clear increase in anxiety, fear, or confusion

- Worsening of nighttime agitation or delirium

- Cases where fall risk increases as a result of the intervention

- The intervention carries extremely low physical invasiveness

- The greatest risk is overzealous environmental modifications driven by good intentions

- Do not aim for a perfect environment

- The mere fact that the environment remains stable is, in itself, the most effective intervention

- The relationship between lighting environment, circadian rhythm, sleep, and delirium

- The relationship between environmental factors, falls, and BPSD

- The positioning of environmental adjustments as a form of non-pharmacological intervention

- Supplementary material to describe the content of interventions

- Documentation of implementation methods and fidelity

- Clarification of the definition of non-pharmacological interventions

- A simple manual for care workers

- Handout materials for family caregivers

- Shared reference for aligning care policies and environmental strategies

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).