1. Introduction

Revision total knee arthroplasty (rTKA) is among the most challenging procedures in reconstructive knee surgery. Successful outcomes depend on meticulous preoperative planning, accurate restoration of limb alignment and joint line height, and stable fixation on healthy bone stock [

1,

2]. Conventional revision strategies emphasize systematic exposure, implant removal, and reconstruction of bone defects using stems, augments, metaphyseal cones and constrained implants to restore the mechanical axis and knee stability [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Approaches such as those proposed by Abdel and Della Valle further highlight the importance of extensile exposure to manage complex revisions safely [

7]. As Laskin underscored in “Ten Steps to an Easier Revision TKA”, minimizing bone loss and restoring balance are key determinants of long-term success [

8]. In addition, as described by Morgan-Jones et al., the fixation of the implants is planned along three anatomical zones (i.e., epiphysis/joint surface, metaphysis, and diaphysis), with durable constructs achieving secure fixation in at least two of these three zones [

9]. Conventional revision techniques to achieve mechanical alignment may require additional bone resection and compromise the remaining metaphyseal bone stock, particularly when modular stems, augments and metaphyseal cones are required. This may limit further reconstructive options and increase the technical complexity of subsequent revisions.

Recent robotic-assisted systems have introduced new possibilities for an improved accuracy, reproducibility and personalization in knee arthroplasty. Both imageless second-generation platforms and CT-based robotic-arm systems allow three-dimensional planning, precise correction of deformities, and intraoperative gap assessment [

10]. These features can be leveraged not only in primary arthroplasty but also in selected revision TKA where bone stock is preserved and allow functional alignment principles instead of conventional mechanical alignment to optimize knee balance and biomechanics while limiting additional bone resection.

The goal of this technical note is to describe a reproducible, robotic-assisted, bone-preserving workflow for the revision of failed primary TKA with minimal metaphyseal bone stock loss using conventional posterior-stabilized components with short cemented stems. This concept builds on the bone-preserving principles previously detailed for robotic conversion of medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) to TKA and aims to provide a “bridge” between robotic-assisted primary and conventional revision TKA performed with mechanical technique and alignment [

11].

2. Surgical Technique

This protocol was developed to enable revision TKA workflow using advanced robotic assistance. The strategy emphasizes functional alignment, precise three-dimensional preoperative planning, and dynamic intraoperative adjustment based on real-time assessment of limb alignment, gap balance, and soft-tissue tension, in line with recently described robotic techniques [

11].

2.1. Preoperative Planning

For each case, a hip–knee–ankle CT scan is obtained according to a standard lower-limb protocol and uploaded into the Mako robotic software (Mako 3.1—Stryker, Mahwah, NJ, USA). A specific metal–artifact–reduction algorithm is not used at the time of image acquisition. Instead, artifact reduction is performed afterwards at the reconstruction console, where both a conventional bone-kernel series and a metal–artifact–reduced series are created. Residual artifacts related to the in situ TKA components are anticipated and considered when choosing the bone regions that will subsequently be used for registration and checkpoint validation.

The three-dimensional CT reconstruction is reviewed to evaluate bone stock, component position, global alignment of the limb, and the surrounding soft-tissue envelope. Particular focus is placed on metaphyseal bone quality, the size and location of bone defects, and the expected competence of the collateral ligaments based on combined clinical and imaging findings.

Within this framework, preoperative planning aims to define functional alignment targets that preserve metaphyseal bone and restore the joint-line height as close as possible to its anatomical position.

2.2. Patient Positioning and Approach

The patient is placed in the supine position on the operating table without the use of a tourniquet. The previous midline incision is incorporated whenever possible, and a standard medial parapatellar arthrotomy is carried out to expose the knee. The patella is everted laterally with care to protect the extensor mechanism. Synovectomy and debridement of fibrous tissue are performed as necessary to improve visualization while respecting the collateral ligaments. Synovial and periprosthetic tissue samples are harvested for microbiological culture and histopathological analysis according to our institutional protocol. The limb is then secured in a stable position to allow smooth tracking of the robotic arm and unrestricted range-of-motion testing throughout intraoperative assessment.

2.3. Pins Placement and Landmark Registration

Array pins for the robotic system (4 mm on the femoral side and 3 mm on the tibial side) are inserted according to the manufacturer’s protocol through the same medial parapatellar approach to minimize additional soft-tissue damage (

Figure 1). The polyethylene insert is then removed to expose the relevant reference surfaces.

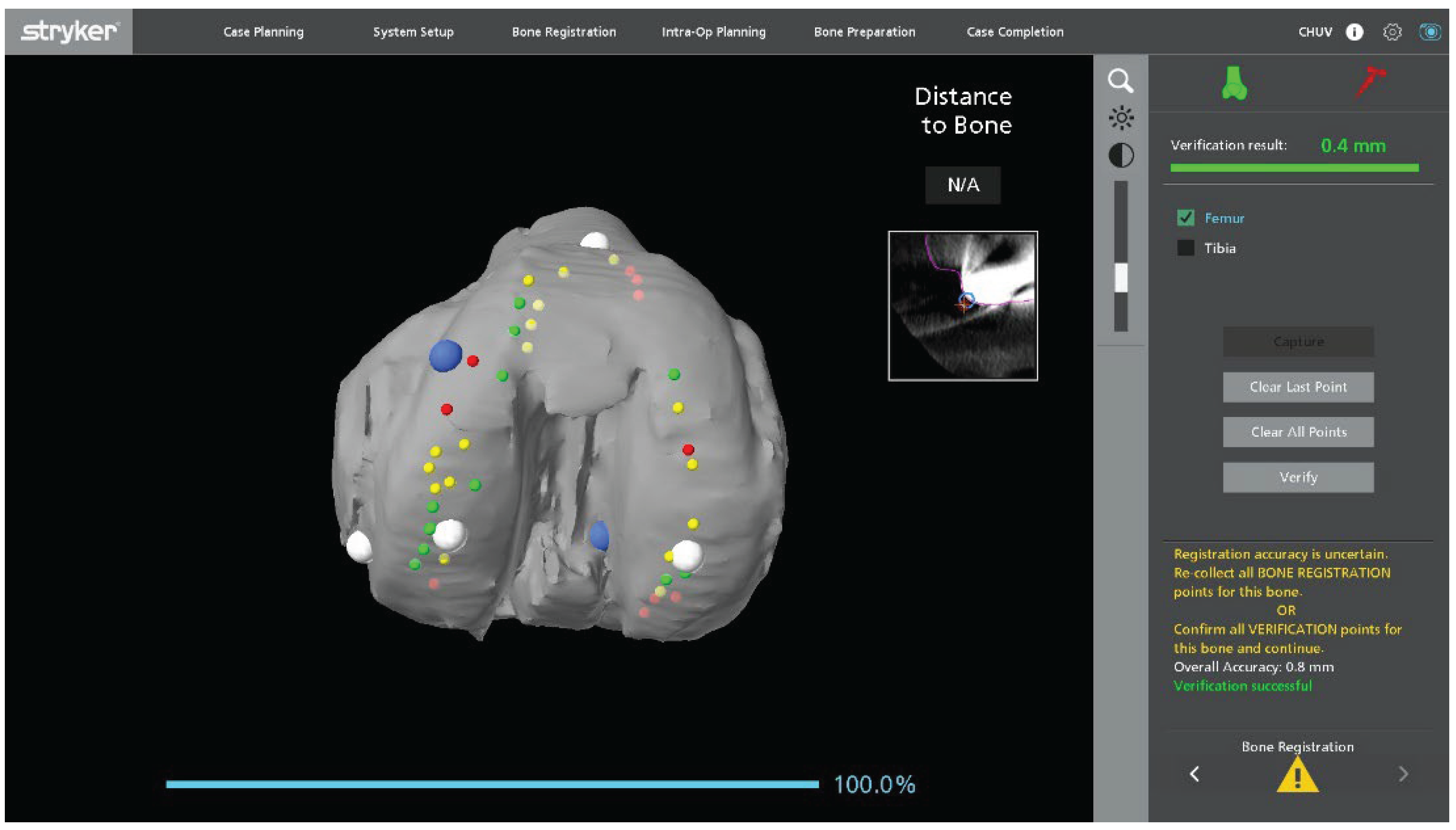

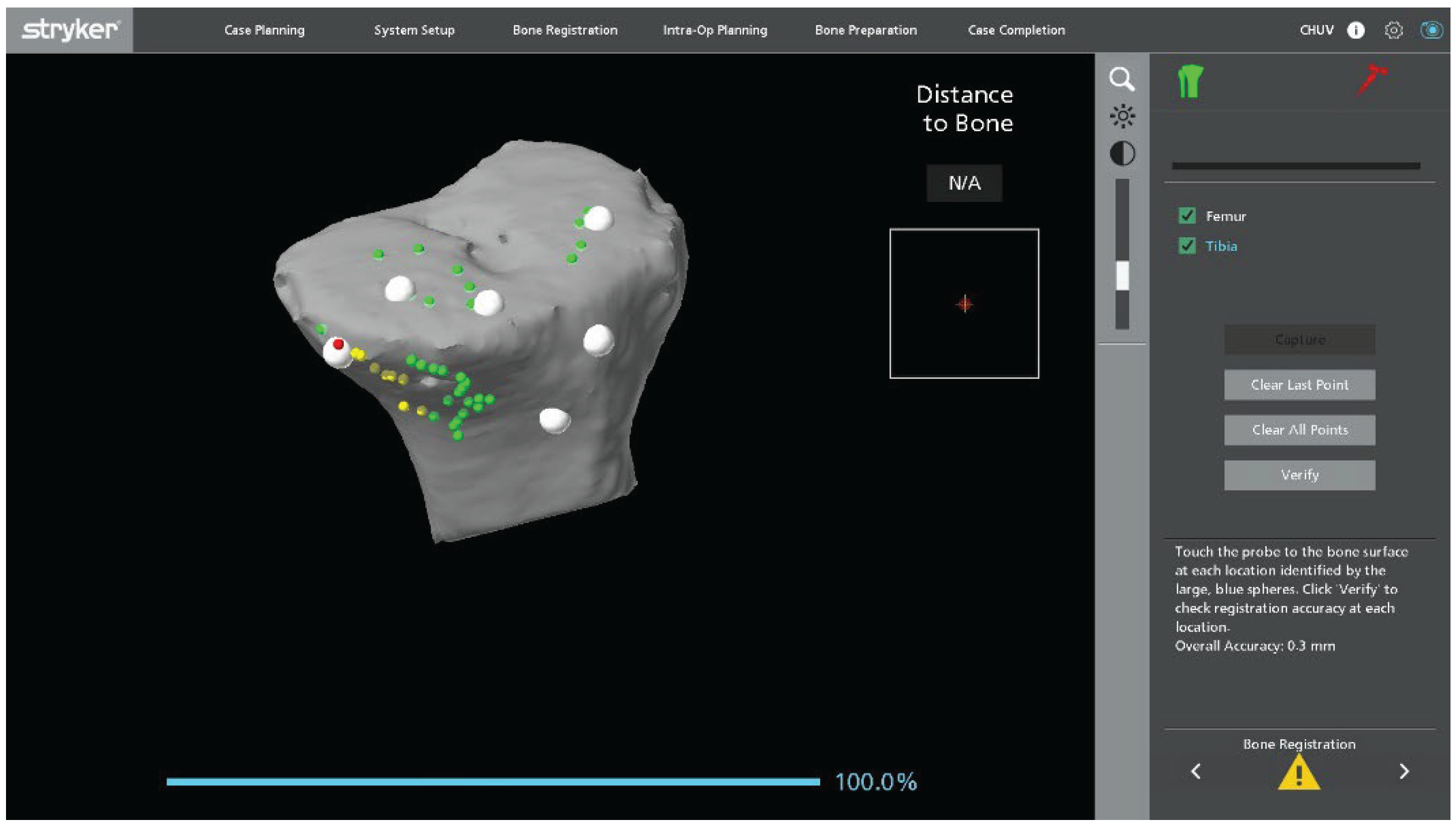

Registration landmarks are acquired directly on the in situ metallic femoral and tibial components as well as on the adjacent exposed bone (

Figure 1). On the femoral side, registration is guided by the internal and external condylar contours, using a central condylar axis on the component to reduce the influence of CT metal artifacts and improve mapping accuracy (

Figure 2). On the tibial side, points are collected over the central portion of the medial and lateral tibial plateau as well as on the metaphyseal bone (

Figure 3).

Once landmark acquisition is complete, the polyethylene insert is reinserted to allow dynamic intraoperative assessment of ligament balance. In mobile bearing designs, the definitive polyethylene insert can be reinserted. In fixed bearing implants, particularly when the locking mechanism is damaged or uncertain, a trial insert can be used to avoid compromising the final component. Registration accuracy is verified using the system’s checkpoints. If any checkpoint shows a residual error greater than 0.5 mm, both landmarks and checkpoints are repeated until all values fall within the acceptable tolerance.

2.4. Intraoperative Alignment and Ligament Balance Assessment

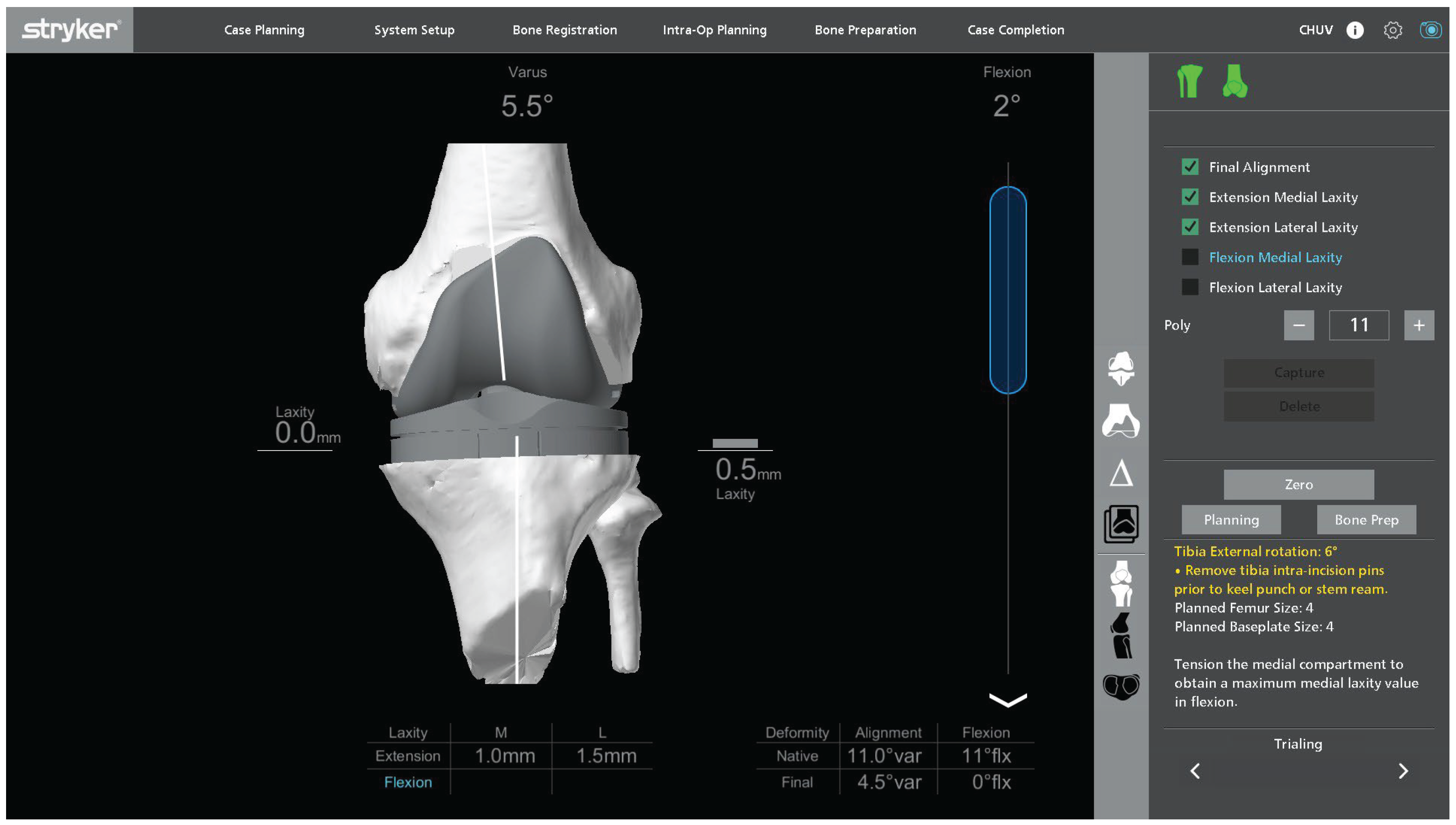

Once registration has been completed with the primary TKA components in situ, a first intraoperative assessment of functional alignment is carried out. In our technique, a functional alignment framework refers to using robot-assisted planning to optimize component positioning primarily through planned resections to achieve target gaps within predefined coronal and sagittal alignment boundaries. The targets include a hip-knee-ankle angle of approximately 180° ± 5° and restoration of joint-line height within ±2 mm of the native level. This planning also accounts for the restrictions imposed by short cemented stems due to potential cortical contact.

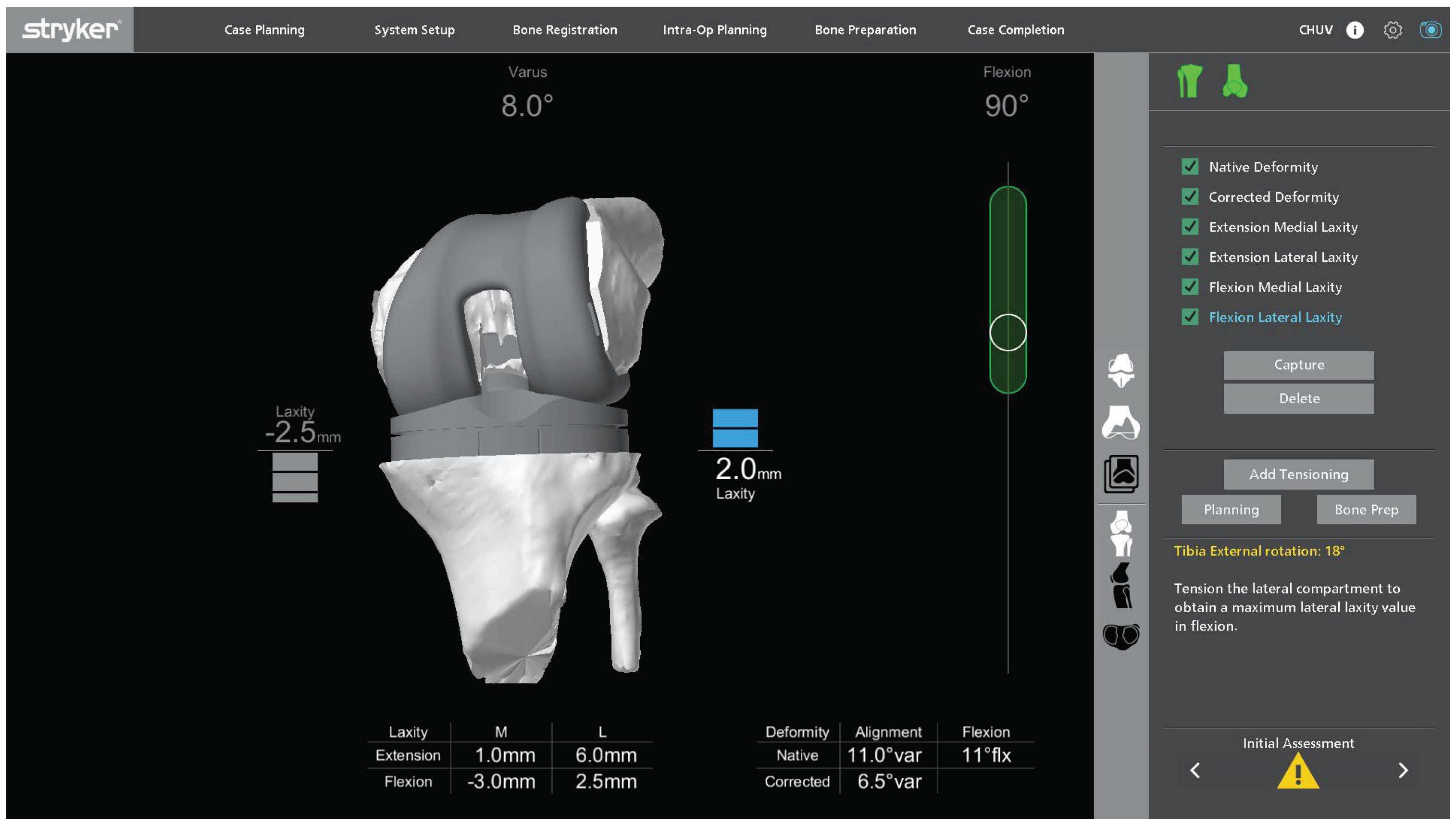

Figure 4 illustrates a representative example of this initial assessment performed under varus-valgus stress, which may reveal coronal malalignment and gap asymmetry prior to plan adjustment. The polyethylene insert is reinserted so that ligament behavior can be evaluated dynamically in flexion and extension. This provides immediate feedback on coronal and sagittal balance and helps determine whether the initial plan requires adjustment. The limb is then taken through a full range of motion, and the robotic system is used to monitor limb alignment and gap behavior in real time.

Varus-valgus stress is applied at different degrees of flexion to analyze collateral ligament function and quantify coronal laxity. The target is symmetric medial and lateral gaps in full extension. In flexion, a small lateral predominance is acceptable, with the lateral gap up to 2 mm larger than the medial gap at 90° of flexion, in keeping with functional alignment principles and individualized gap planning [

12].

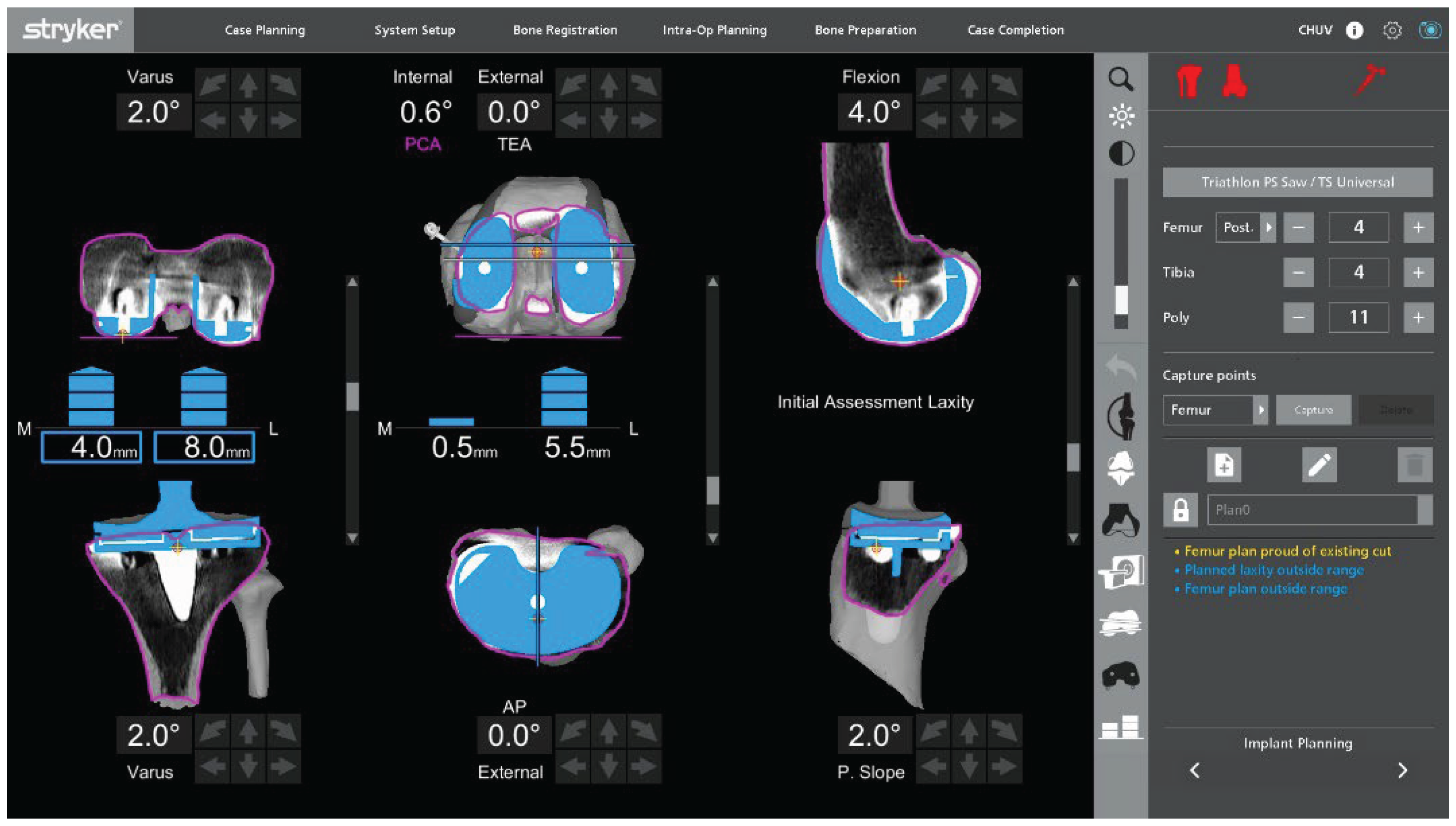

Under this functional-alignment philosophy, coronal and sagittal balance are primarily corrected by adjusting component positioning and planned resection levels (

Figure 5) rather than by performing extensive collateral ligament or soft-tissue releases. When adjusting tibial coronal alignment, the varus–valgus position of the tibial baseplate must be planned while projecting the femoral and tibial 50 mm short stems, ensuring that their tips do not impinge on the metaphyseal cortical bone.

2.5. Implant Removal

After finalizing of the planification, the femoral and tibial components are removed using thin osteotomes, flexible saw blades, and dedicated extraction instruments. Careful sequential release of the bone-metal or bone-cement interface is performed while minimizing lever forces to reduce the risk of iatrogenic metaphyseal defects or fracture.

On the tibial side, particular care is given around the keel or stem region to preserve remaining metaphyseal bone. All loose cement fragments and debris are removed under direct visualization. The femoral condyles, posterior cortex, and tibial plateaus are inspected to confirm that bone stock remains compatible with a bone-preserving revision strategy.

If a patellar button is present and well fixed, positioned, without macroscopic wear lesion, no revision of this component is performed. In cases with a native patella, resurfacing was systematically performed during the rTKA to reduce the risk of subsequent anterior knee pain and potential reoperation.

2.6. Robotic Planning and Bone Resection

After implant removal, the exposed bone surfaces are compared with the preoperative plan. If the extent or pattern of bone loss differs from the preoperative assessment, the robotic plan is adjusted accordingly while maintaining the bone-preserving philosophy.

Robotic-guided resections are then performed. Distal and posterior femoral resections are executed to restore joint line height, posterior condylar offset, and flexion–extension gap symmetry. Tibial resection is limited to the minimum depth required to obtain a flat, stable platform, preserving as much metaphyseal bone as possible. The robotic system provides real-time feedback on resection depth, orientation, and alignment, allowing fine-tuning before completing each cut.

2.7. Bone Defect Management

After bone resections, residual contained metaphyseal defects are addressed. Autologous cancellous bone graft is harvested from the resected femoral or tibial bone, or supplemented with morselized allograft chips, and impacted into the defect with a tamp to recreate a stable and supportive bed for the cemented implants.

This technique is intended for defects that remain compatible with primary resections and a standard tibial baseplate footprint. Larger segmental defects, extensive uncontained bone loss, or situations requiring structural support beyond local grafting are considered outside the indications of this bone-preserving technique and warrant traditional revision constructs with stems, augments, and/or metaphyseal cones [

13].

2.8. Final Implantation

Trial components are inserted to confirm flexion–extension gap balance, stability, and patellar tracking. Alignment and soft tissue tension are reassessed both without and with varus–valgus stress in full extension and at 90° of flexion. Polyethylene insert thickness is adjusted as needed to achieve the planned balance according to the preplanned functional alignment strategy (

Figure 6). The planned alignment, joint line position, and gap targets are achieved and confirmed intraoperatively using the robotic platform.

Once the surgeon is satisfied with stability, alignment, and tracking, definitive tibial preparation is performed, and definitive posterior-stabilized cemented components are implanted. Short 50 mm cemented stems are systematically used on both the tibial and femoral sides to enhance metaphyseal support while preserving overall bone stock. Cement is pressurized on both the femoral and tibial sides, ensuring adequate penetration into the prepared bone surfaces. Excess cement is removed, and the final component position is checked both visually and with the robotic system’s verification tools.

The patella is resurfaced as part of the procedure to reduce the risk of anterior knee pain and secondary procedures.

2.9. Irrigation and Closure

The joint is irrigated thoroughly with saline, and hemostasis is achieved. The arthrotomy is closed in a watertight fashion, followed by closure of subcutaneous tissues and skin according to standard practice. No drain is used routinely. Postoperative care follows an Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) pathway [

14]. A sterile dressing is applied for wound protection.

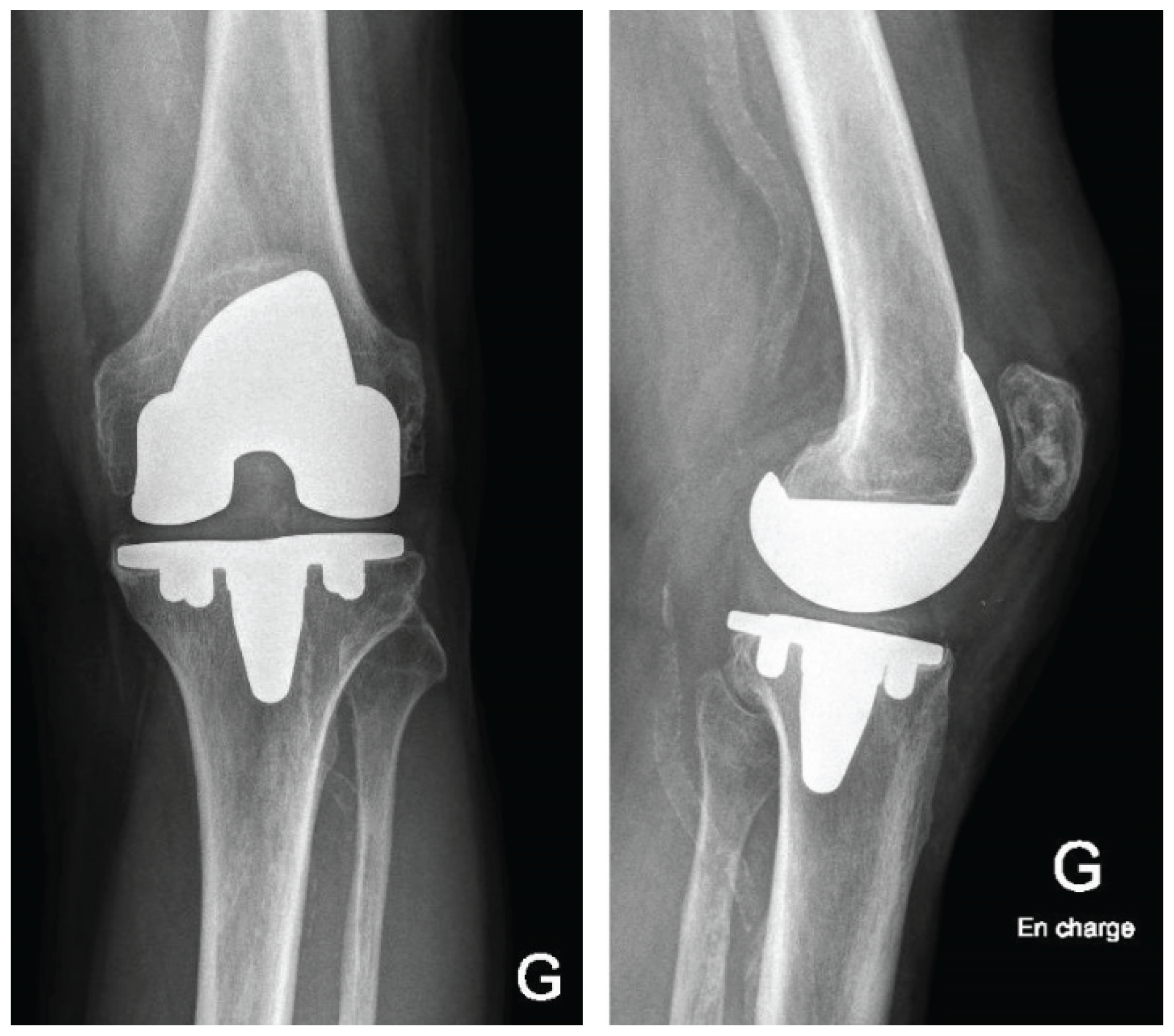

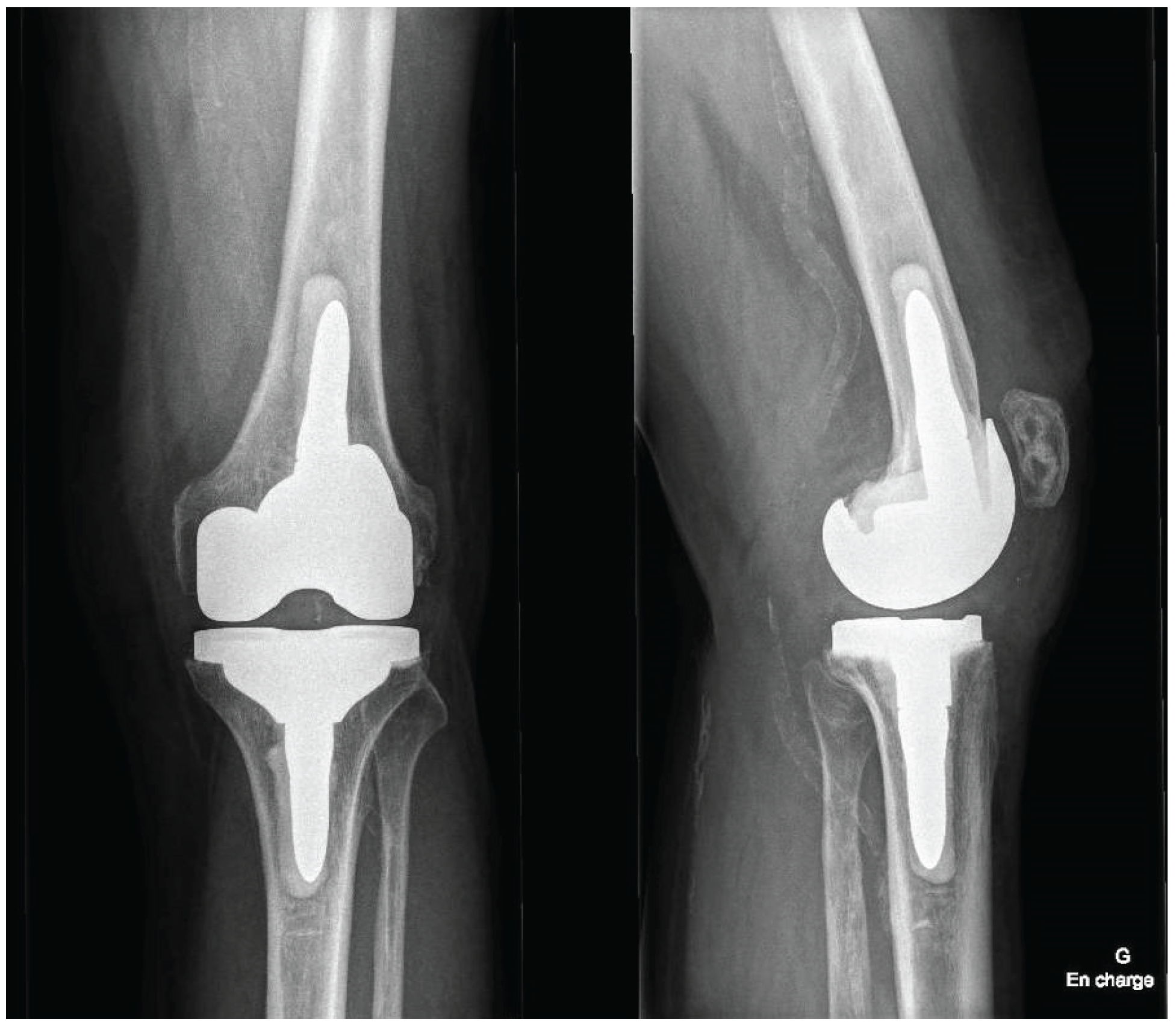

Postoperatively, patients follow a standardized rehabilitation program encouraging early mobilization and full weight-bearing as tolerated. Deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis and early quadriceps activation exercises are initiated according to institutional protocol. Postoperative radiographs of the knee and full-length lower limb are obtained to confirm accurate component positioning (

Figure 7).

3. Results

This described robotic workflow enabled stable registration on the in situ primary TKA components and facilitated controlled, bone-preserving implant removal. Functional-alignment planning combined with robotic guidance corrected the preoperative deformity towards the planned alignment target within predefined coronal and sagittal boundaries and restored full range of motion. Gap behavior consistent with functional-alignment principles was achieved without collateral ligament release or additional soft tissue balancing procedures. Final femoral and tibial component positioning closely matched the preoperative 3D plan, and postoperative radiographs confirmed restoration of limb alignment and appropriate component positioning.

4. Discussion

Revision TKA requires accurate management of bone loss, implant fixation, soft-tissue balance and stability. Classical revision concepts, as described by Dennis et al., further refined by Abdel and Laskin, emphasize systematic exposure, implant removal, restoration of the joint line, and reconstruction of bone defects using stems, augments, and constrained implants to restore alignment and stability [

1,

2,

7,

8]. While these strategies have yielded reliable outcomes, they often require substantial additional bone resection and may compromise the remaining metaphyseal bone stock, particularly in younger or more active patients [

1,

2,

3]. In selected cases with limited bone defects that do not require metaphyseal cones or long stems, the zonal fixation framework described by Morgan-Jones et al. supports a bone-preserving strategy, provided that stable fixation can still be achieved in at least two of the three zones (epiphysis, metaphysis, diaphysis) [

9].

Robotic assistance offers a potential paradigm shift in this setting. Cochrane et al. recently reported that robotic-assisted rTKA with a second-generation imageless system can achieve precise bone preparation and reproducible alignment with favorable early outcomes [

10]. By integrating three-dimensional planning, controlled bone resections, and real-time gap assessment, robotic workflows enhance intraoperative accuracy and standardization while maintaining the versatility to adapt to intraoperative findings. In parallel, bone-preserving, CT-based robotic workflows have been described for UKA-to-TKA conversion, further supporting the role of robotic assistance in complex knee reconstruction [

11].

In the present surgical technique, robotic assistance provided a controlled environment for applying the principles emphasized by Dennis and Laskin, namely to preserve bone, restore the joint line, and ensure stability, within a functional alignment framework [

1,

2,

8]. Fine-tuning of soft-tissue balance was achieved through dynamic intraoperative assessment rather than extensive collateral ligament releases, thereby supporting a bone-preserving strategy in selected cases with competent ligamentous structures.

Management of limited tibial metaphyseal defects followed the principles described by Huten et al., using impacted autologous cancellous graft beneath the tibial baseplate to restore a stable platform without resorting to stems or augments [

3,

12]. Current evidence summarized by Yapp et al., Ayekoloye et al., and Driesman et al. indicates that cemented constructs and stemmed revision strategies can provide reliable mid- to long-term survival in complex rTKA, and that cemented fixation remains a widely accepted option in this context [

4,

5,

6]. In this case, bone stock was preserved and the soft tissue envelope was intact. Therefore, cemented fixation using standard posterior stabilized components was considered sufficient. For limited bone defects, routine use of short 50 mm cemented stems provides additional metaphyseal support. This approach is consistent with the Morgan Jones zonal fixation concept because it secures epiphyseal and metaphyseal fixation in two of the three zones without the need for metaphyseal cones or long diaphyseal stems [

9].

Conceptually, this workflow extends the bone preserving robotic approach previously reported for UKA to TKA conversion to the setting of failed primary TKA [

11]. The goal is to implement a functional alignment strategy with conservative bone resections using a standardized and reproducible workflow. Alignment targets may be constrained by the use of 50 mm short cemented stems to avoid cortical tip contact. In appropriately selected patients, this approach also limits the routine need for augments or highly constrained implants.

This bone-preserving robotic workflow is intended for patients with preserved metaphyseal bone stock (with defects amenable to correction by primary resections and local grafting), competent collateral ligaments, and no clinical or radiological suspicion of periprosthetic joint infection. Cases with extensive bone loss, collateral ligament insufficiency or persistent instability throughout the arc of motion, suspected or confirmed infection, or severely compromised bone quality remain better suited to conventional revision-type constructs using stems, cones, augments, and higher levels of constraint [

1,

2,

3,

7].

This technical note is limited by its descriptive nature and the absence of systematic clinical and radiographic outcome data, which will be reported in a future study. Furthermore, this workflow should be restricted to high-volume surgeons familiar with both robotic-assisted TKA and rTKA principles, as a learning curve should be anticipated for surgeons new to robotic platforms. The technique is more straightforward in designs with modular or easily removable mobile polyethylene inserts. In fixed-bearing constructs, care must be taken not to damage the insert during removal so that it can be reinserted for intraoperative ligament balancing or use the trial component of the construct in place. In addition, when planning tibial coronal alignment, the position and length of the tibial and femoral stems must be considered to avoid impingement on the metaphyseal cortical bone, particularly in the presence of asymmetric defects. Larger prospective series and comparative studies are needed to evaluate the reproducibility, efficiency, and survivorship of robotic-assisted bone-preserving revision workflows compared with conventional revision techniques [

10,

11].

5. Conclusions

This technical note outlines a reproducible, accurate, bone-preserving, robotic-assisted workflow to revise failed primary TKA associated with minimal metaphyseal bone loss to rTKA with conventional posterior-stabilized components with short cemented stems within a functional-alignment framework The procedure integrates CT-based three-dimensional planning, registration on in situ implants, functional-alignment principles, and dynamic intraoperative ligament assessment to achieve stable fixation on preserved metaphyseal bone while restoring limb alignment and balanced gaps.

This approach is intended for carefully selected patients with adequate metaphyseal bone stock, competent collateral ligaments, and no evidence of periprosthetic joint infection, whereas cases with extensive bone loss, ligament insufficiency, infection, or compromised bone quality remain more appropriately managed with conventional revision-type constructs. We recommend that this workflow be implemented in centers with established experience in robotic TKA and revision knee arthroplasty. A consecutive case series is underway to refine indications and evaluate the safety, effectiveness, and implant survivorship of this bone-preserving robotic revision strategy.

Author Contributions

All authors read and approved the final version submitted for publication; JM: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing; AA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing; TR: Review and Editing; AF: Review and Editing; JW: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analyzed. De-identified operative images underlying the figures are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, subject to institutional and patient-privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to the work reported. Outside the submitted work, J.W. serves as a consultant for Stryker and Enovis, and receives royalties from Dedienne Santé. The technique described was developed independently by the authors. No author received funding, support, materials, or honoraria from Stryker (or any other company) for this study.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UKA |

Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty |

| TKA |

Total Knee Arthroplasty |

| rTKA |

Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty |

References

- Dennis, DA; Berry, DJ; Engh, G; et al. Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008, 16(8), 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis, DA. A Stepwise Approach to Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2007, 22(4) Suppl 1, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huten, D; Pasquier, G; Lambotte, JC. Techniques for Filling Tibiofemoral Bone Defects During Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2021, 107(1S), 102776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yapp, LZ; Scott, CEH; Baxendale-Smith, L; et al. Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty Using a Fully Cemented Single-Radius Condylar Constrained Prosthesis Has Excellent Ten-Year Survival and Improvements in Outcome Measures. Bone Joint J 2025, 107-B(10), 1036–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayekoloye, C; Radi, M; Backstein, D; Qa’oud, MA. Cemented Versus Hybrid Technique of Fixation of the Stemmed Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Literature Review. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2022, 30(9), e703–e713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driesman, AS; Macaulay, W; Schwarzkopf, R. Cemented Versus Cementless Stems in Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty. J Knee Surg. 2019, 32(8), 704–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel, MP; Della Valle, CJ. The Surgical Approach for Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty. Bone Joint J 2016, 98-B(1 Suppl A), 113–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laskin, RS. Ten Steps to an Easier Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2002, 17(4) Suppl 1, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan-Jones, R; Oussedik, SI; Graichen, H; Haddad, FS. Zonal fixation in revision total knee arthroplasty. Bone Joint J 2015, 97-B(2), 147–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cochrane, NH; Kim, BI; Stauffer, TP; et al. Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty With an Imageless, Second-Generation Robotic System. J Arthroplasty 2024, 39(8S1), S280–S284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahlouly, J; Antoniadis, A; Royon, T; Wegrzyn, J. Bone-Preserving Robotic Conversion of Medial UKA to TKA: A Step-by-Step Technique. J Clin Med. 2025, 14(21), 7887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shatrov, J.; Battelier, C.; Sappey-Marinier, E.; Gunst, S.; Servien, E.; Lustig, S. Functional Alignment Philosophy in Total Knee Arthroplasty—Rationale and technique for the varus morphotype using a CT based robotic platform and individualized planning. SICOT-J. 2022, 8, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durand, Y; Royon, T; Kaegi, M; Antoniadis, A; Wegrzyn, J. Impaction bone grafting using fresh-frozen femoral head addressing severe bone defect in complex primary and revision TKA: A technical note. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2025, 104314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, M; Albrecht, E; Koninckx, A; Wegrzyn, J. ERAS in the field of orthopedics: presentation of a multidisciplinary program designed to optimize care for patients undergoing hip or knee arthroplasty. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN 2025, 65, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).