1. Introduction

Platelet concentrates (PCs) are indispensable blood components used in the management of hematologic malignancies, bone marrow failure syndromes, and patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (1). They are primarily transfused prophylactically to prevent hemorrhage in thrombocytopenic patients. PCs are prepared by differential centrifugation of whole blood—yielding platelet-rich plasma (PRP) or buffy coat (BC) fractions—or by apheresis, which selectively collects platelets from a single donor using automated systems. Regardless of preparation method, platelet products are typically leukoreduced, depleted of erythrocytes, and suspended in autologous plasma or platelet additive solutions (PAS) to improve stability during storage (2-4). Platelet storage at 22–24 °C is limited to 3–5 days due to the risk of bacterial contamination and the development of platelet storage lesion (PSL)—a progressive deterioration involving structural, biochemical, and functional changes that compromise transfusion efficacy (5, 6). PSL manifests as morphological alterations, spontaneous granule release, decreased responsiveness to agonists such as adenosine diphosphate (ADP), and receptor shedding. In particular, metalloproteinase-mediated cleavage of key glycoproteins, including GPIbα and GPV, leads to impaired adhesion and aggregation (7, 8).

While several PSL-associated changes are irreversible, some metabolic impairments may be reversible if not accompanied by phosphatidylserine (PS) exposure. Nonetheless, PSL can trigger platelet apoptosis, characterized by PS externalization, microvesicle formation, and enhanced activation (7, 9). These processes contribute to inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects and accelerate the clearance of senescent platelets by macrophages in the spleen and liver (10). Ensuring the structural and functional integrity of platelets during storage is essential for transfusion efficacy and safety. Conventional quality assessments—such as platelet count, pH, and visual inspection—are inadequate to fully capture platelet functionality (11-13). Flow cytometry has emerged as a sensitive technique for evaluating platelet quality through analysis of surface receptor expression (e.g., GPIbα, GPVI, αIIbβ3), annexin V binding, and RNA content using thiazole orange (TO), which differentiates young from aged platelets (14-16). Despite these advances, variability in transfusion outcomes and platelet refractoriness persists, underscoring the need for improved biomarkers of storage-induced alterations.

This study aims to evaluate the molecular and functional changes in platelet membrane glycoproteins during storage, focusing on the expression dynamics of GPIbα, GPVI, αIIbβ3, and CD9, alongside RNA content analysis. The findings are expected to enhance understanding of PSL mechanisms and identify potential indicators of platelet quality and transfusion performance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Citrate, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), disodium hydrogen phosphate (Na₂HPO₄), and dipotassium phosphate (K₂HPO₄) were procured from Merck (Kilsyth, Victoria, Australia). Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (Tris), sodium chloride (NaCl), and potassium chloride (KCl) were obtained from Amresco (Solon, Ohio, USA). Paraformaldehyde (PFA) was sourced from BHD Laboratory Supplies (United Kingdom). Thiazole orange (TO) fluorescent dye was acquired from Sigma-Aldrich (USA). Bovine serum albumin (BSA) was also obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Missouri, USA).

2.2. Antibodies

Murine monoclonal antibody AK2, which specifically recognizes the extracellular domain of glycoprotein Ib alpha (GPIbα), was utilized as previously described (17). The murine monoclonal antibody 1G5, directed against the extracellular domain of glycoprotein VI (GPVI), was generated using conventional hybridoma technology (Sigma, St. Louis, IL, USA) and its purification and characterization have been documented in prior studies (17, 18). Monoclonal antibodies targeting αIIbβ3 integrin (CD41a) and human CD9 were acquired from Becton Dickinson (San Jose, CA, USA). Additionally, a polyclonal rabbit anti-human GPVI antibody was employed as previously reported (17). All antibodies were conjugated with phycoerythrin (PE) to enable quantitative analysis by flow cytometry.

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Preparation of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and platelet-poor plasma (PPP)

Venous blood samples were drawn from healthy volunteers into tubes containing 3.2% (w/v) trisodium citrate as the anticoagulant. To obtain PRP, the collected blood was centrifuged at 100 × g for 20 minutes. PPP was then produced by centrifuging the resulting PRP at 300 × g for 10 minutes. The supernatant was gently aspirated, transferred into Eppendorf tubes, and centrifuged again at maximum speed for 2 minutes to eliminate any remaining platelets. The clarified plasma was stored at –80 °C until use. Platelet counts were measured in both whole blood and PRP.

Expired platelet concentrate units obtained through apheresis-where platelets were collected and all other blood components returned to the donor-were also included. Details regarding the platelet additive solution (PAS), the PAS-to-plasma ratio, and the composition of the storage bag (including plasticizers) were recorded. Whole blood from healthy donors and the expired platelet concentrate units were supplied by the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at King Abdulaziz Medical City for use in this study.

2.3.2. Single staining of platelet (surface expression level) measurements

Flow cytometry was employed to quantify the surface expression of platelet membrane receptors, including GPIbα, GPVI, αIIbβ3, and CD9. PRP, obtained from either healthy donors or platelet concentrate units, was incubated with PE-conjugated monoclonal antibodies specific to each receptor (PE-AK2, PE-1G5, PE-CD41a, and PE-anti-CD9), while unstained samples served as negative controls. To inhibit metalloproteinase-mediated proteolytic cleavage of surface receptors, 10 mM EDTA was added. Samples were incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature in the dark to protect the fluorochrome from photobleaching. Following incubation, platelets were washed twice by centrifugation with 0.5 mL of Tris-saline buffer supplemented with 5 mM EDTA. Stained platelets were then analyzed using flow cytometry, with detection performed through the FL2 channel.

2.3.3. Plasma soluble GPVI measurement by ELISA

Concentrations of soluble glycoprotein VI (sGPVI) in plasma samples obtained from healthy donors or platelet concentrates was measured as previously described (18). In brief, 96-well microplates were coated with a polyclonal anti-GPVI antibody at a concentration of 1 µg/mL and incubated for 1 hour at room RT. Wells were subsequently washed with phosphate-buffered saline containing Tween-20 (PBS-T) and blocked with bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 hour to prevent non-specific binding. Following another washing step, plasma samples (diluted 1:10 in PBS) or recombinant GPVI (spiked into GPVI-depleted plasma) were added in duplicate wells. Detection was performed using the monoclonal anti-GPVI antibody 1A12 at a concentration of 1 µg/mL, followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody at a 1:500 dilution. Finally, enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) substrate was added, and signal detection was carried out using a PerkinElmer luminescence detection system.

2.3.4. Thiazole orange staining (TO)

Thiazole orange (TO), a nucleic acid–binding fluorochrome, was employed to quantify platelet ribonucleic acid (RNA) content, thereby facilitating the distinction between (young) and (aged) platelet populations. TO is a metachromatic fluorochrome with high affinity for nucleic acids and was utilized to assess the RNA content of platelets, enabling differentiation between immature (young) and mature (aged) platelet subpopulations. In brief, 20 μL of PRP was mixed with 15 μL of PBS containing 5 mM EDTA to preserve physiological pH and inhibit calcium-dependent platelet activation. Subsequently, 5 μL of 4% PFA was added to achieve fixation, and the samples were incubated for 10 minutes at room temperature in the dark. For RNA staining, TO stock solution (1 mg/mL) was diluted in PBS containing 5 mM EDTA to a final concentration of 1 μg/mL. A volume of 0.5 μL of this working solution was then added to the fixed platelet suspension and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature, protected from light to prevent photobleaching. Following staining, platelet samples were analyzed using flow cytometry, and fluorescence was detected in the FL1 channel. The proportion of reticulated platelets—defined as those exhibiting TO fluorescence indicative of residual RNA—was quantified and expressed as a percentage of the total platelet population. A threshold of 1% TO-positive platelets served as the reference standard for identifying and evaluating the fraction of reticulated (young) platelets.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Comparisons between two groups were performed using the Student’s t-test, while multiple group comparisons were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Graphical representations and statistical calculations were generated using GraphPad Prism software, version 9.4.1 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Differences were considered statistically significant at a threshold of P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Analysis of Platelet Surface Receptor Expression in healthy donors

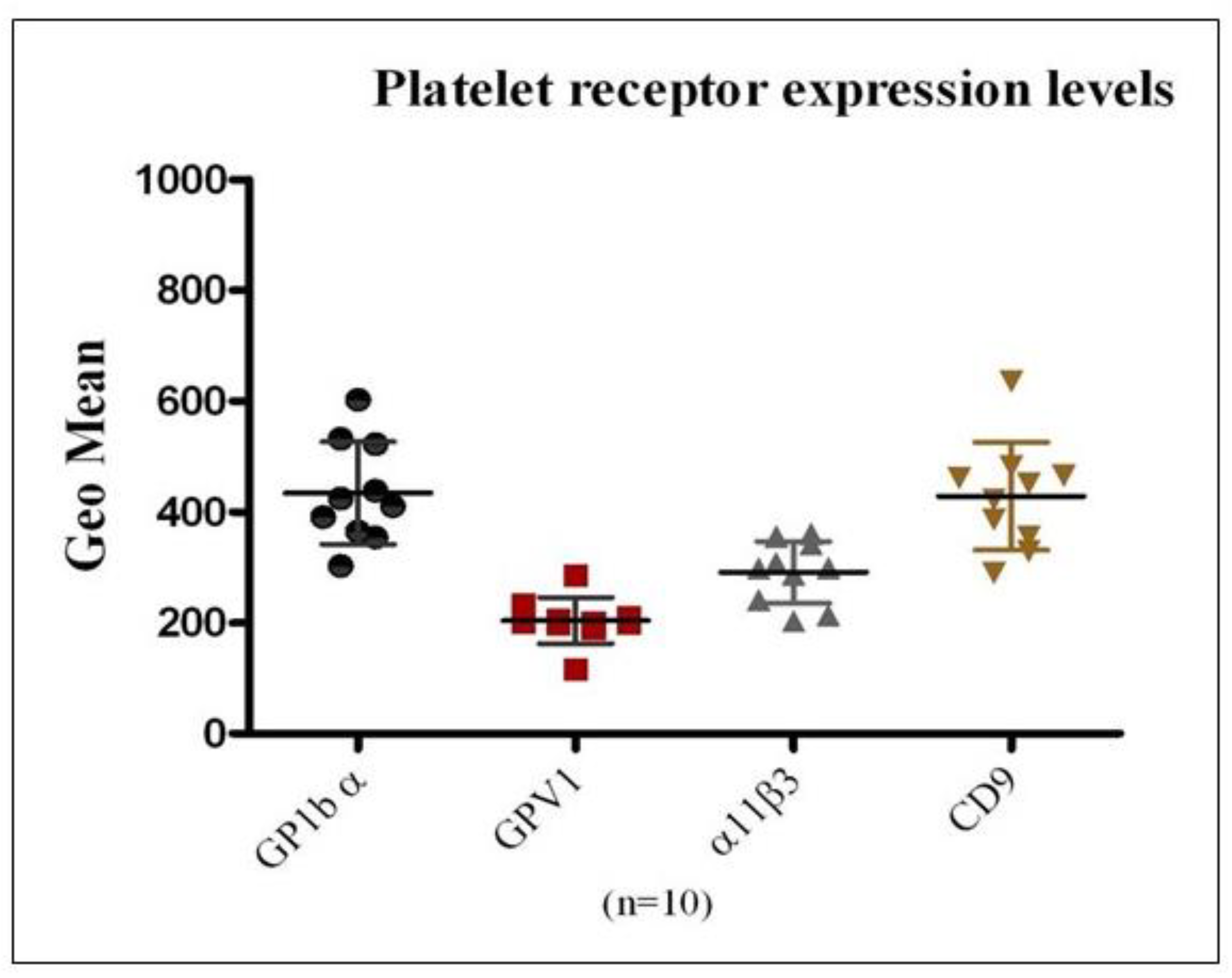

To evaluate the applicability of flow cytometry for the precise quantification of platelet membrane receptor expression and to establish reference ranges for receptor density, surface levels of GPIbα, GPVI, αIIbβ3 integrin, and CD9 were analyzed in platelets obtained from ten healthy donors. PE-conjugated monoclonal antibodies specific to each receptor were employed, and data were reported as mean ± SEM (

Figure 1). Among the receptors examined, GPIbα and CD9 demonstrated higher mean surface expression relative to GPVI and αIIbβ3 integrin. Considerable inter-individual variability in receptor expression was also observed across the donor cohort, highlighting inherent biological heterogeneity in platelet receptor profiles.

3.2. Quantitative Analysis of Platelet Surface Receptor Expression in Platelet Concentrate Units

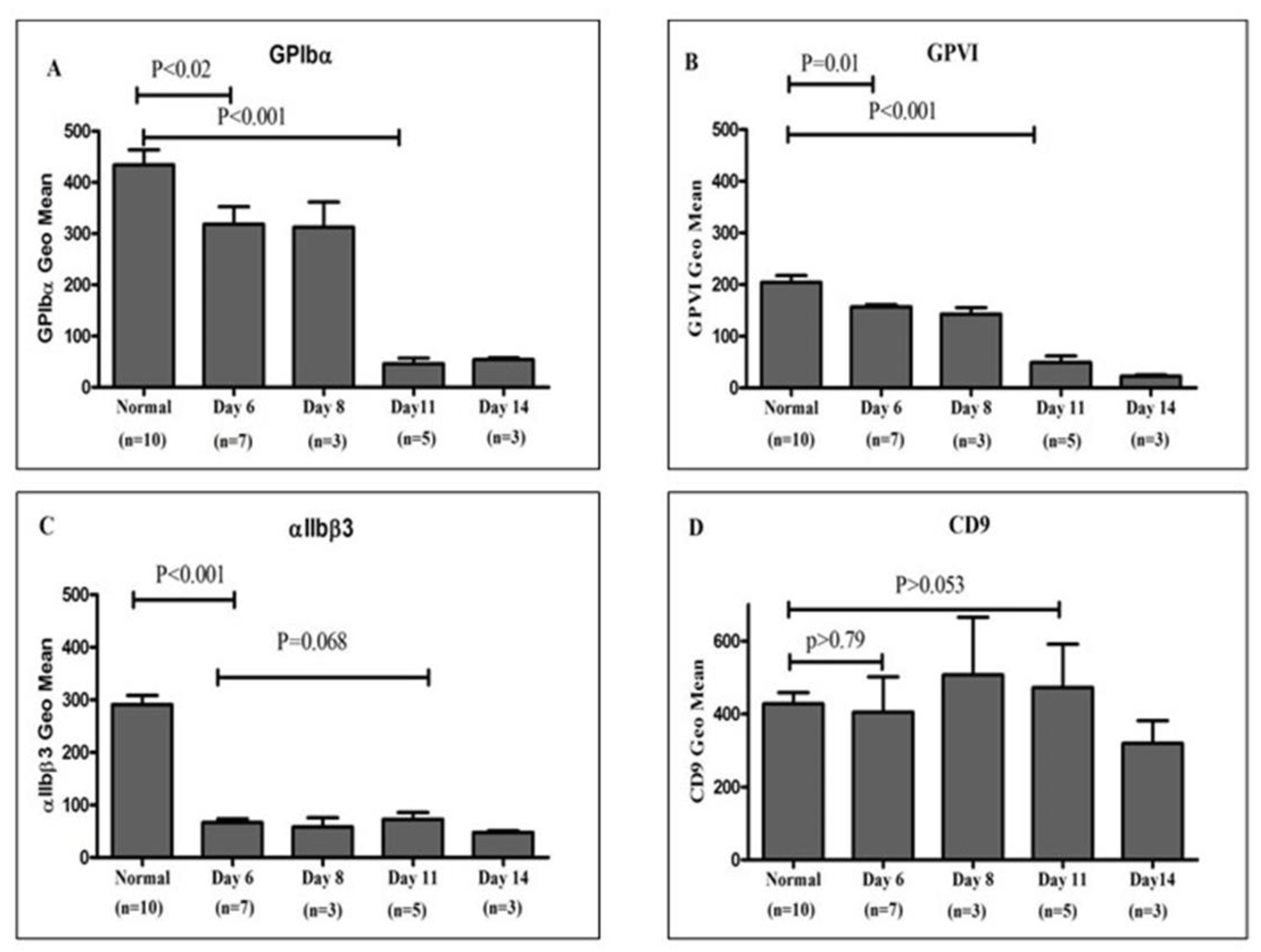

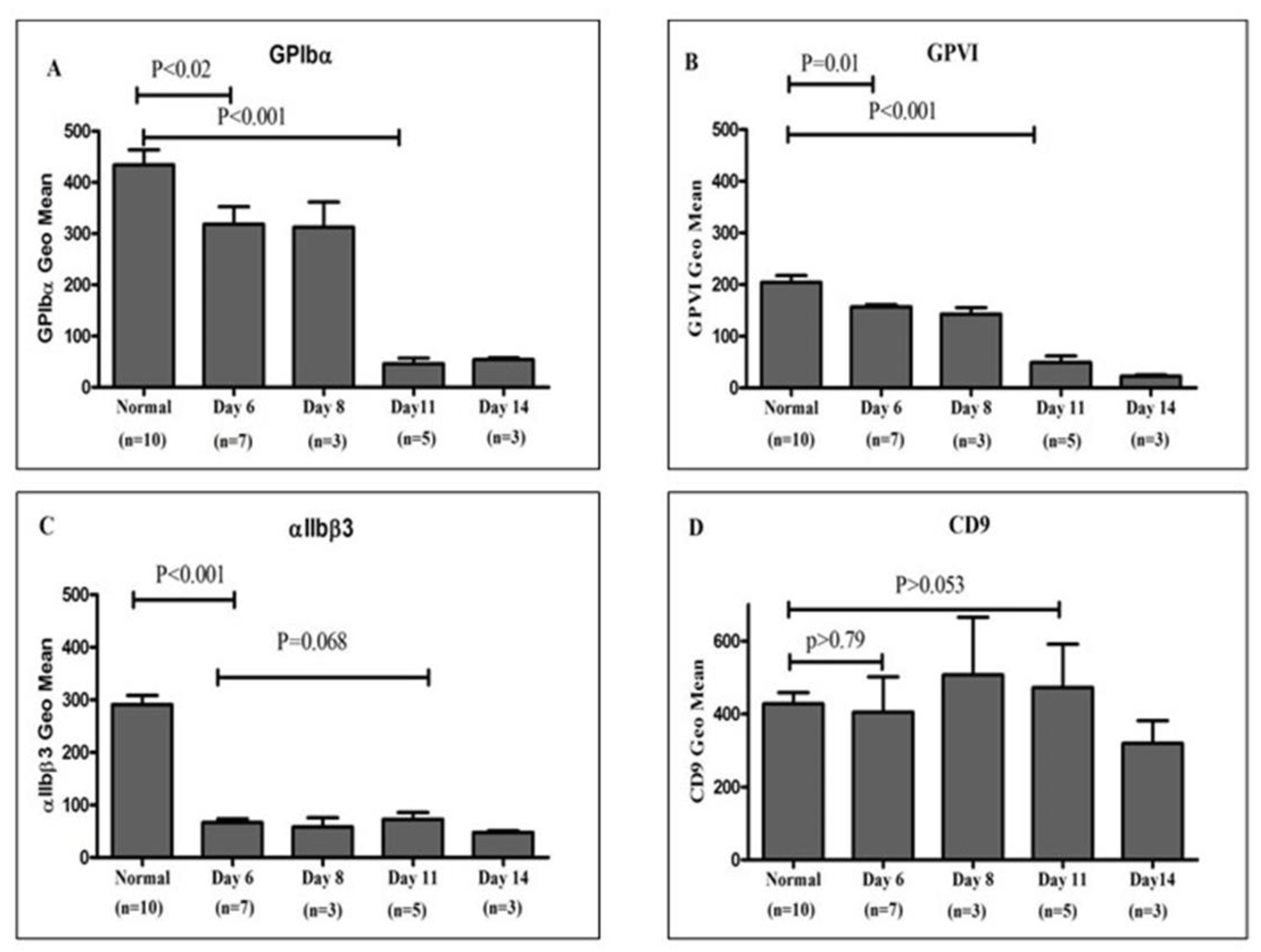

Nineteen platelet concentrate units, routinely prepared and provided by the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at King Abdulaziz Medical City, were analyzed to evaluate the surface expression of platelet membrane receptors GPIbα, GPVI, αIIbβ3 integrin, and CD9. The units were maintained under standard storage conditions at room temperature (22–24 °C) with continuous agitation and were assessed individually on days 6, 8, 11, and 14 of storage. Comparative analysis, as illustrated in

Figure 2, shows receptor expression levels in stored platelet units relative to freshly isolated platelets from healthy donors. A progressive decline in GPVI and GPIbα expression was observed over the storage period, reaching statistical significance by day 11 (P < 0.05). In contrast, integrin αIIbβ3 expression decreased markedly as early as day 6, followed by relative stabilization through day 11. CD9 expression demonstrated variable patterns throughout storage, without a consistent temporal trend.

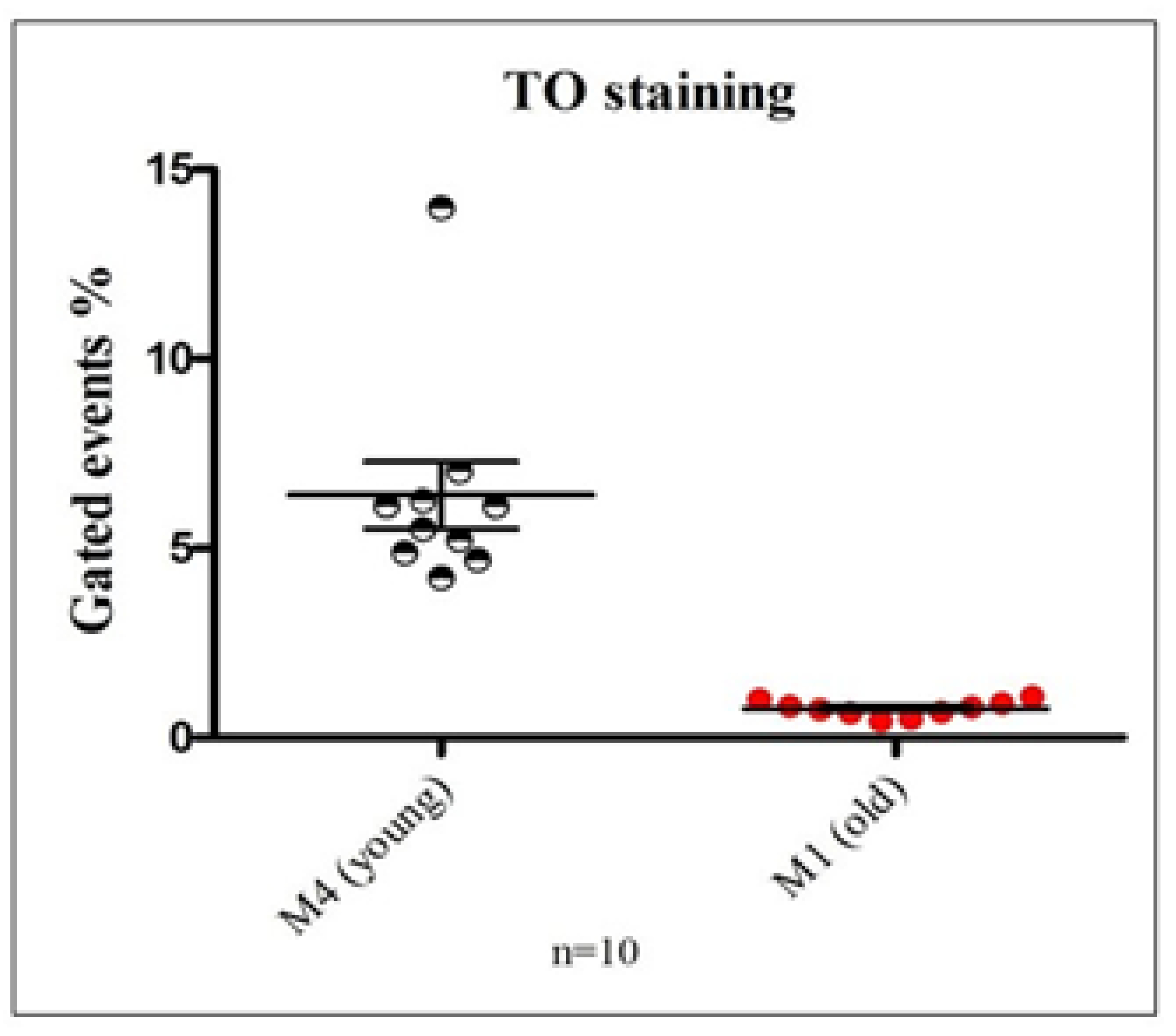

3.3. Quantitative Assessment of Platelet mRNA Content in Healthy Donors

To determine the proportion of young versus aged platelets in circulation, samples from 10 healthy individuals were analyzed using TO staining and flow cytometry to assess mRNA content. The percentage of events detected within the M1 (young platelets) and M4 (aged platelets) flow cytometric gates was compared (

Figure 3). The data revealed a significantly higher proportion of M1 events relative to M4, indicating that approximately 6% of circulating platelets in healthy individuals exhibit elevated RNA content consistent with newly formed, reticulated platelets. These findings demonstrate the assay’s sensitivity in distinguishing between young and senescent platelet populations.

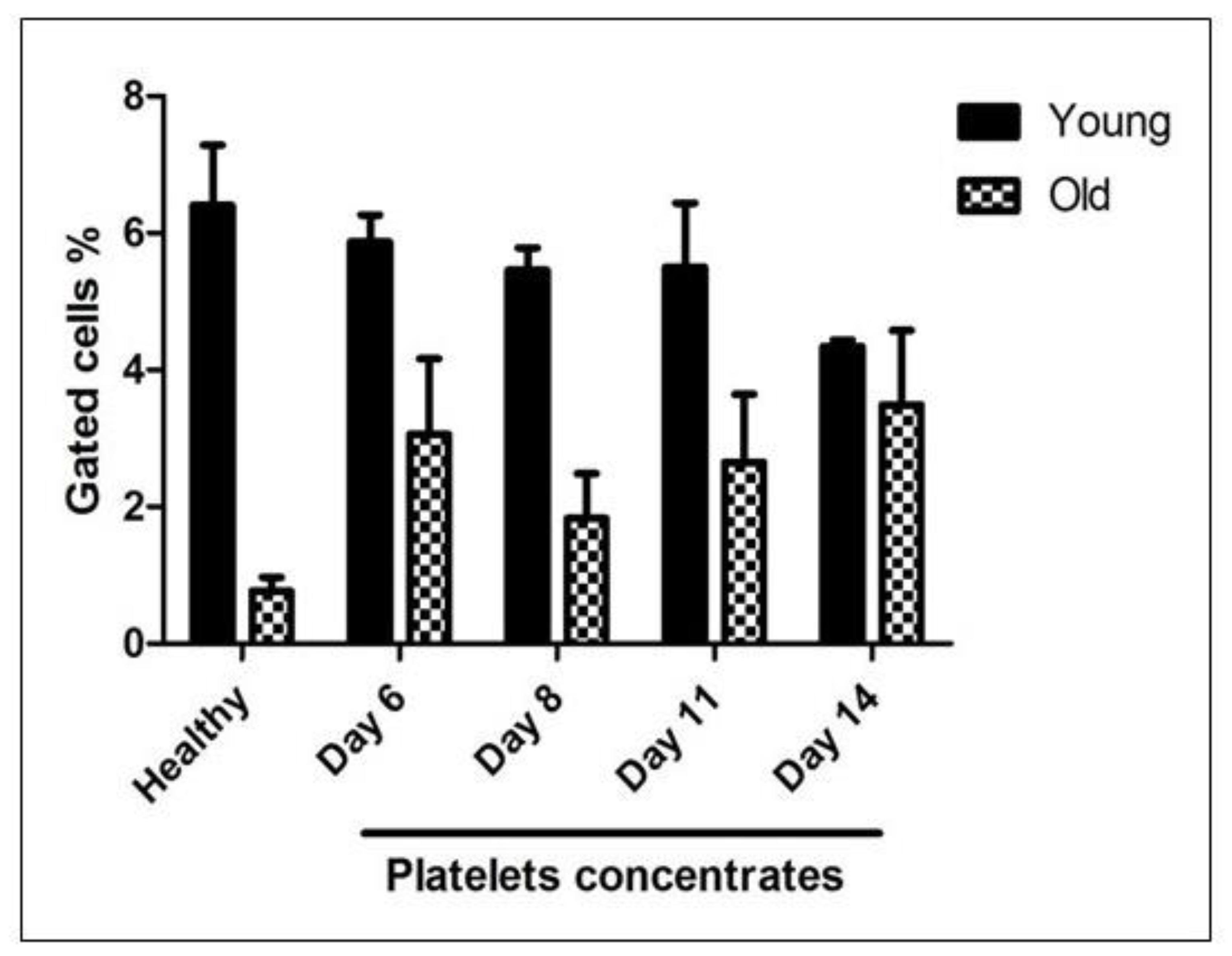

3.4. Measurement of mRNA Content in Stored Platelet Concentrates

As illustrated in

Figure 4, the proportion of events within the M1 gate—representing young, RNA-rich platelets—progressively declined in platelet concentrate samples throughout the storage duration. Conversely, the percentage of events within the M4 gate—indicative of aged, RNA-depleted platelets—was consistently higher in stored platelet concentrates compared to those from healthy donors. Notably, the proportion of senescent platelets increased steadily over time, reaching its peak by day 14 of storage.

3.5. Measurement of Soluble GPVI in Platelet Concentrates Using ELISA

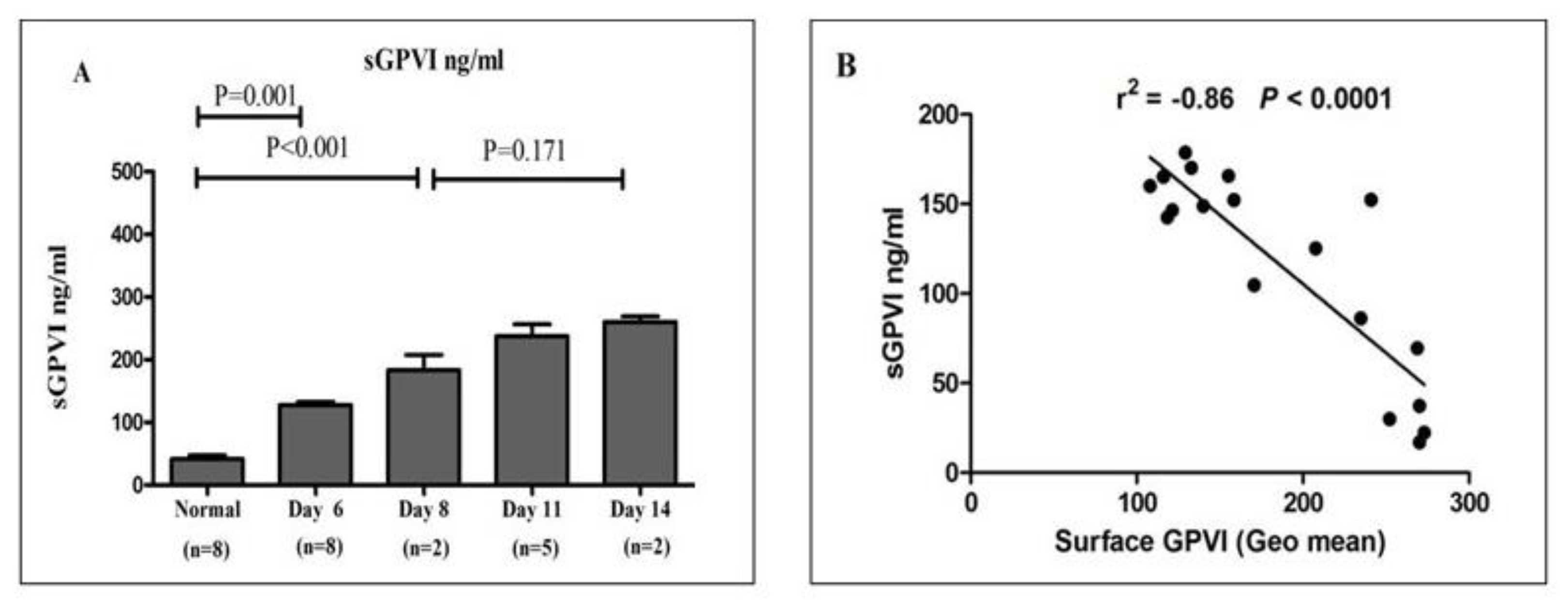

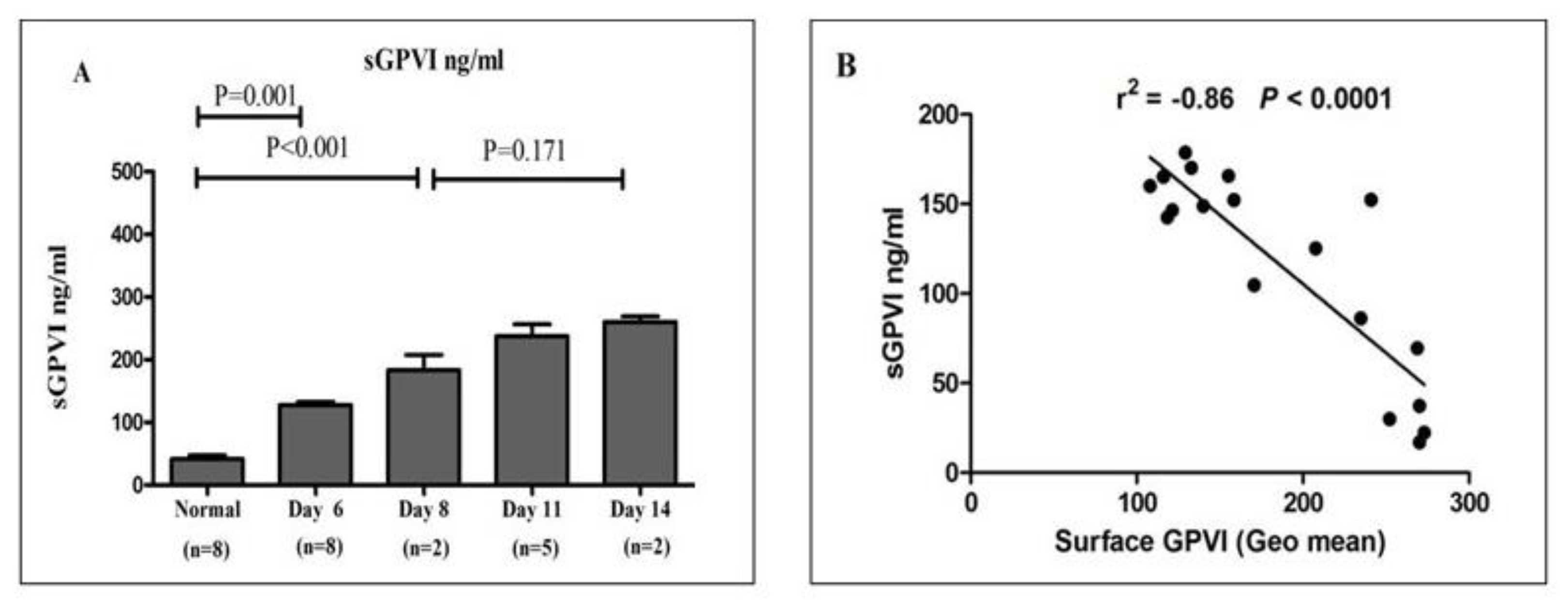

Soluble glycoprotein VI (sGPVI) levels were determined in plasma samples derived from healthy donors and platelet concentrates stored for varying durations. As depicted in

Figure 5, sGPVI concentrations were significantly elevated in platelet concentrate-derived plasma by day 6 of storage when compared to plasma from healthy individuals. Moreover, sGPVI levels continued to increase progressively throughout the storage period, peaking on day 14, indicating enhanced receptor shedding during extended storage.

4. Discussion

The evaluation of platelet quality for transfusion purposes during storage remains a critical challenge, despite extensive in vitro characterization of PSLs. Platelet functionality is largely governed by surface receptors, including GPIb-IX-V, GPVI, and αIIbβ3, which mediate adhesion, activation, and aggregation (19-23). In this study, flow cytometry was employed as a sensitive and quantitative approach to investigate platelet receptor expression, providing novel insights into platelet biology and storage-induced alterations. The research focused on assessing both the surface expression of key platelet receptors and the mRNA content in platelets derived from PRP of healthy donors and pooled platelet concentrate units. Flow cytometric assays were optimized using PRP from healthy donors, enabling precise quantification of receptor density through PE-conjugated, affinity-purified monoclonal antibodies, and establishing baseline reference ranges for normal platelet receptor expression.

The presented result of surface expression level assessment in healthy individuals and in expired pooled platelet concentrates showed that GPIbα and GPVI expression levels were significantly reduced at Day 6 (p <0.05) compared to normal donors, remained stable up to Day 11, and markedly dropped at Day 11 (p <0.001), with progressive reduction over the storage period (

Figure 1 & Figure 2). Generally, GPIbα is a glycoprotein expressed on the platelet surface at almost 25,000 copies, and has a key role in regulating coagulation at the surface of activated platelets (24, 25). However, the absence or reduction of expression of GPIbα level causes defective platelet adhesion and bleeding disorders (25). GPVI plays a major role in regulated platelet adhesion to collagen and is a trigger for platelet activation. It presents on the platelet surface with 5,000- 6,000 copies (26). But, dysfunction or reduced levels of GPVI lead to impaired adhesion and thrombus formation. Following the presented result, that indicates this finding is consistent with the previously published findings (27) that GPIbα and GPVI are reduced during platelet aging and storage, which results in activation of proteolysis mechanisms (28, 29). There is evidence of metalloproteinase-mediated soluble ectodomain fragment GPIbα (glycocalicin) and metalloproteinase-mediated soluble GPVI ectodomin in plasma. However, in vivo GPIbα shows constitutive shedding and reduced levels in normal platelet, whereas GPVI is mainly entirely intact on the surface of healthy platelets (18, 29). Eventually, the alteration in the expression of these receptors during platelet concentrate storage will promote unexpected functions and down- regulated mechanisms.

Integrin αIIbβ3 (GPIIb, IIIa) has a low affinity for ligand binding until activated by inside-out activation of αIIbβ3 altering receptor conformation and have the capability to promote platelet aggregation by binding fibrinogen or VWF to form fibrin clots. αIIbβ3 is the most frequently expressed glycoprotein on the platelet surface, with almost 30,000 copies (30, 31). Abnormalities in expression level of αIIbβ3 will cause defective platelet aggregation and other clinical platelet concerns. This assay showed that αIIbβ3 expression level was markedly decreased from Day 6 after platelet storage (p <0.001) and remained stable up to Day 14 (

Figure 2). A previous paper stated that αIIbβ3 is lost through isolated platelets or platelet storage periods and could be due to storage over time, significantly promoting platelet activation as a result of rapid platelet aggregated formation (30). Also, through this presented study, surface expression level of CD9 was not changed significantly with age of platelet storage compared to that of healthy donors (p>0.05;

Figure 2). There is no clear evidence for this variation of CD9 expression level during platelet storage. CD9 is a member of the tetraspanin family that is involved in regulation of signal transduction in platelets and other cells (32).

The nucleic acid dye TO in the study of the mRNA content of platelets is an established assay for assessing platelet activity and distinguishing platelet aging. The presented results showed the optimized population of M1 and M4 using healthy individuals (

Figure 3). As shown in

Figure 4, the percentage of events in M1, corresponding to young platelets, was gradually decreased in platelet concentrates over the storage period. Furthermore, the percentage of events in M4, corresponding to old platelets, was higher in stored platelet concentrates compared to healthy donors. The percentage of old platelets was increased gradually during storage to reach a maximum at Day 14. The events were calculated and presented as mean Mean ± SEM. Prior studies showed that the content of mRNA in platelets is influenced by long-term storage (39). Through activation of metalloproteinase-mediated soluble GPVI ectodomin shedding, full-length GPVI of ~62 kDa is significantly cleaved into a ~55-kDa soluble fragment and a ~7-kDa remnant, which remains platelet-associated. This suggests that assessment of GPVI levels during platelet storage may be a biomarker (33, 36). Therefore, in this project, sGPVI measurements in plasma samples obtained from healthy donors or platelet concentrates stored over time were performed by ELISA. The results demonstrated that sGPVI levels are higher in platelet concentrates Day 6 compared to healthy levels; also, sGPVI progressively increased over storage time to reach the maximum at Day 14. In addition, this study showed the correlation between sGPVI in plasma and GPVI surface levels (Geo mean). GPVI was significantly decreased, whereas sGPVI markedly increased during platelet storage over time (

Figure 5).

5. Conclusion

In summary, the present study demonstrates that platelet count and MPV do not consistently correlate with surface receptor expression in stored platelets. Importantly, flow cytometry–based analysis of platelet receptor expression and mRNA content revealed novel insights into storage-associated alterations. Specifically, the surface levels of key adhesion receptors, including GPIbα, GPVI, and αIIbβ3 integrin, exhibited a progressive decline over the storage period, whereas CD9 expression remained largely stable, indicating that receptor loss is selective for adhesion molecules. The observed increase in sGPVI further supports the utility of monitoring GPVI shedding as a biomarker for platelet storage lesions. Continuous monitoring of platelet receptor expression at early storage time points (Days 1–5) and employing repeated measurements could enhance the accuracy and reproducibility of these assessments. Overall, these findings advance our understanding of platelet receptor biology, the molecular mechanisms underlying storage-induced functional decline, and the potential for mRNA content analysis to serve as a complementary tool in evaluating platelet quality, with significant implications for transfusion medicine.

Authors’ contributions

NMA was responsible for the conception and design of the study, performing the experiments, validating the results, and drafting the manuscript. AMA, TB, HAM, and BMA participated in conducting the experiments, collecting and analyzing the data, and co-authoring the results section. All authors reviewed and revised the manuscript for intellectual content, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for all aspects of the work.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the King Abdullah International Medical Research Center (KAIMRC) under approval number NRR25/123/5. The requirement for obtaining informed consent was waived by the IRB due to the nature of the study.

Availability of data and materials

Data can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author, Dr. Naif M. Alhawiti, upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank the KAIMRC for their invaluable support in conducting this research and for covering the publication fees. We also extend our gratitude to all the staff and colleagues who contributed to the successful completion of this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted without any commercial or financial relationships construed as potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Junt, T.; Shcherbina, S.; Chen, Z.; Massberg, S.; Goerge, T.; Krueger, A.; et al. Dynamic visualization of thrombopoiesis within bone marrow. Science 2007, 317, 1767–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, P.; Devine, D.V. Proteomics meets blood banking: identification of protein targets for the improvement of platelet quality. J Proteomics 2010, 73(3), 436–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawaz, M. Platelets. Lancet 2000, 355(9214), 1531–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga-Szabo, D.; Pleines, I.; Nieswandt, B. Cell adhesion mechanisms in platelets. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008, 28(3), 403–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, H.; Freedman, J. Platelets in hemostasis and thrombosis: role of integrins and their ligands. Transfus Apher Sci. 2003, 28(3), 257–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, R.K.; Berndt, M.C. Platelet physiology and thrombosis. Thromb Res. 2004, 114(5–6), 447–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiess, B.D. Platelet transfusions: the science behind safety, risks and appropriate applications. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2010, 24(1), 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cauwenberghs, S.; van Pampus, E.; Curvers, J.; Akkerman, J.W.; Heemskerk, J.W. Hemostatic and signaling functions of transfused platelets. Transfus Med Rev. 2007, 21(4), 287–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, D.E.; Hallam, T.J.; Somers, M.C. Agonist selectivity and second messenger concentration in Ca²⁺ mediated secretion. Nature 1982, 296(5854), 256–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelson AD, editor. Platelets. San Diego: Academic Press; 2002. p. 65–84.

- Rivera, J.; Lozano, M.L.; Navarro-Nunez, L.; Vicente, V. Platelet receptors and signaling in the dynamics of thrombus formation. Haematologica 2009, 94(5), 700–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, R.K.; Berndt, M.C. Platelet physiology and thrombosis. Thromb Res. 2004, 114, 447–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, R.K.; Gardiner, E.E.; Shen, Y.; Whisstock, J.C.; Berndt, M.C. Glycoprotein Ib-IX-V. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2003, 35(8), 1170–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, R.K.; López, J.A.; Berndt, M.C. Molecular mechanisms of platelet adhesion and activation. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1997, 29(1), 91–105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nieswandt, B.; Moers, A.; Sachs, U.J. Platelets in atherothrombosis: lessons from mouse models. J Thromb Haemost. 2005, 3(8), 1725–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, R.K.; Denuja, K.; Gardiner, E.E.; Berndt, M.C. Platelet receptor proteolysis: a mechanism for downregulating platelet reactivity. Thromb Haemost. 2007, 98, 1109–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tamimi, M.F.; Arthur, J.F.; Shen, Y.; Moroi, M.; Berndt, M.C.; Andrews, R.K.; Gardiner, E.E. Anti-glycoprotein VI monoclonal antibodies directly aggregate platelets independently. Platelets 2009, 20, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tamimi, M.F.; Moroi, M.; Gardiner, E.E.; Berndt, M.C.; Andrews, R.K. Measuring soluble platelet glycoprotein VI in human plasma by ELISA. Platelets 2009, 20, 143–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jian L. Qiao SY, Gardiner. E.E and Andrews.R. K. Proteolysis of platelet receptors in humans and other

species. Walter de Gruyter New York. 2010; 391:893-900.

- Massberg, S.; Gawaz, M.; Gruner, S.; Schule, V.; Konrad, I.; Zohlnhofer, D.; et al. A critical role of glycoprotein VI for platelet recruitment to the injured arterial wall in vivo. J Exp Med. 2003, 197, 41–9. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao JL, Shi Y, Gardiner EE, Andrews RK. Proteolysis of platelet receptors in humans and other species.

New York: Walter de Gruyter; 2010. p. 391–900.

- Shattil, S.J.; Hoxie, J.A.; Cunningham, M.; Brass, L.F. Changes in the platelet membrane glycoprotein IIb-IIIa complex during activation. J Biol Chem. 1985, 260, 11107–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamatic-Crew, V.; Burton, N.; Kagan, A.; Green, C.A.; Levene, C.; Flinter, F.; et al. CD151, the first member of the tetraspanin (TM4) superfamily detected on erythrocytes, is essential for the correct assembly of human basement membranes in kidney and skin. Blood 2004, 104(8), 217–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian L. Qiao SY, Gardiner. E.E and Andrews.R. K. Proteolysis of platelet receptors in humans and other

species. Walter de Gruyter New York. 2010; 391:893-900.

- Cheng, H.Y.; Yuan, R.; Li, S.; Liu, J.; Ruan, C.; Dai, K. Shear-induced interaction of platelets with von Willebrand factor results in glycoprotein GPIbα shedding. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009, 297, H2128–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massberg, S.; Gawaz, M.; Gruner, S.; Schule, V.; Konrad, I.; Zohlnhofer, D.; et al. A critical role of glycoprotein VI for platelet recruitment to the injured arterial wall in vivo. J Exp Med. 2003, 197, 41–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Yan, R.; Li, S.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, J.; Ruan, C.; Dai, K. Shear-induced interaction of platelets with von Willebrand factor results in glycoprotein GPIbα shedding. The American Physiological Society 2009, 297, H2128–H35. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H.Y.; Yuan, R.; Li, S.; Liu, J.; Ruan, C.; Dai, K. Shear-induced interaction of platelets with von Willebrand factor results in glycoprotein GPIbα shedding. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009, 297, H2128–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavda, N.J.; Porter, J.M.; Harrison, P.; Patterson, D.; Machin, S.J. Rapid flow cytometric quantitation of reticulated platelets in whole blood. Platelets 1996, 7, 189–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, H.; Freedman, J. Platelets in hemostasis and thrombosis: role of integrins and their ligands. Transfusion and Apheresis Science 2003, 28(3), 257–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, R.K.; Berndt, M.C. Platelet physiology and thrombosis. Thrombosis Research 2004, 114(5-6), 447–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schubert, P.; Devine, D.V. Proteomics meets blood banking: Identification of protein targets for the improvement of platelet quality. Journal of Proteomics 2010, 73(3), 436–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga-Szabo, D.; Pleines, I.; Nieswandt, B. Cell adhesion mechanisms in platelets. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 2008, 28(3), 403–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apelseth, T.O.; Hervig, T.; Bruserud, Ø. Current practice and future directions for optimization of platelet transfusions in patients with severe therapy-induced cytopenia. Blood reviews 2011, 25(3), 113–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroncek, D.F.; Rebulla, P. Platelet transfusions. Lancet 2007, 370(9585), 427–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Procházková, R.; Andrýs, C.; Hubácková, L.; Krejsek, J. Markers of platelet activation and apoptosis in platelet concentrates collected by apheresis. Transfus Apher Sci. 2007, 37(2), 115–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Quantitative Analysis of Platelet Surface Receptor Expression in PRP from Healthy Donors: This figure presents the geometric mean fluorescence intensity Mean ± SEM for the surface expression of platelet receptors GPIbα, GPVI, αIIbβ3 integrin, and CD9, as assessed in PRP from ten healthy donors using flow cytometry. The results demonstrate the capability of the assay to accurately quantify receptor density on the platelet surface. Expression levels differed across receptor types within individual donors and also showed notable inter-individual variability for the same receptor.

Figure 1.

Quantitative Analysis of Platelet Surface Receptor Expression in PRP from Healthy Donors: This figure presents the geometric mean fluorescence intensity Mean ± SEM for the surface expression of platelet receptors GPIbα, GPVI, αIIbβ3 integrin, and CD9, as assessed in PRP from ten healthy donors using flow cytometry. The results demonstrate the capability of the assay to accurately quantify receptor density on the platelet surface. Expression levels differed across receptor types within individual donors and also showed notable inter-individual variability for the same receptor.

Figure 2.

Temporal Analysis of Platelet Surface Receptor Expression in Stored Platelet Concentrates Compared to Healthy Donors: This figure depicts a comparative analysis of the surface expression profiles of platelet membrane receptors GPIbα, GPVI, αIIbβ3 integrin, and CD9 in platelet concentrate units stored at 22–24 °C over a 14-day period, relative to freshly isolated platelets from healthy donors. Flow cytometric measurements were performed on days 6, 8, 11, and 14 post-collection to quantitatively assess receptor expression. Data are presented as mean fluorescence intensity ± SEM for GPIbα (A), GPVI (B), αIIbβ3 (C), and CD9 (D). Results demonstrate a significant reduction in GPIbα and GPVI surface expression by day 6, with a marked decline observed by day 11, continuing through day 14 (A, B). αIIbβ3 integrin expression also decreased substantially by day 6 and remained consistently low throughout the storage period (C). Conversely, CD9 levels remained largely stable across all time points, showing no significant differences compared to platelets from healthy donors (D).

Figure 2.

Temporal Analysis of Platelet Surface Receptor Expression in Stored Platelet Concentrates Compared to Healthy Donors: This figure depicts a comparative analysis of the surface expression profiles of platelet membrane receptors GPIbα, GPVI, αIIbβ3 integrin, and CD9 in platelet concentrate units stored at 22–24 °C over a 14-day period, relative to freshly isolated platelets from healthy donors. Flow cytometric measurements were performed on days 6, 8, 11, and 14 post-collection to quantitatively assess receptor expression. Data are presented as mean fluorescence intensity ± SEM for GPIbα (A), GPVI (B), αIIbβ3 (C), and CD9 (D). Results demonstrate a significant reduction in GPIbα and GPVI surface expression by day 6, with a marked decline observed by day 11, continuing through day 14 (A, B). αIIbβ3 integrin expression also decreased substantially by day 6 and remained consistently low throughout the storage period (C). Conversely, CD9 levels remained largely stable across all time points, showing no significant differences compared to platelets from healthy donors (D).

Figure 3.

Quantification of young and old platelet populations in healthy donors using thiazole orange (TO)–based mRNA staining: This figure illustrates the differential distribution of platelet subpopulations based on RNA content assessed via TO staining and flow cytometric analysis. Region M1 was defined as the TO-negative population, representing senescent or "old" platelets with minimal residual mRNA, whereas region M4 corresponded to the TO-positive population, indicative of "young" platelets with higher RNA content. The graph depicts the proportion of events gated in M4 and M1 regions, expressed as mean ± SEM, highlighting the predominance of young platelets in circulation among healthy individuals.

Figure 3.

Quantification of young and old platelet populations in healthy donors using thiazole orange (TO)–based mRNA staining: This figure illustrates the differential distribution of platelet subpopulations based on RNA content assessed via TO staining and flow cytometric analysis. Region M1 was defined as the TO-negative population, representing senescent or "old" platelets with minimal residual mRNA, whereas region M4 corresponded to the TO-positive population, indicative of "young" platelets with higher RNA content. The graph depicts the proportion of events gated in M4 and M1 regions, expressed as mean ± SEM, highlighting the predominance of young platelets in circulation among healthy individuals.

Figure 4.

Quantification of mRNA content in platelet concentrates using TO staining: Platelets obtained from healthy donors and stored platelet concentrate units at multiple time points were stained with TO and analyzed by flow cytometry to evaluate RNA content. Populations corresponding to TO^high (M4, representing young, RNA-rich platelets) and TO^low/negative (M1, representing senescent, RNA-depleted platelets) were quantified and expressed as mean ± SEM. The data reveal a progressive reduction in the proportion of young (M4) platelets over the storage period, accompanied by a concomitant increase in aged (M1) platelets. These results demonstrate the effectiveness of TO staining as a sensitive and reliable approach for distinguishing platelet age and monitoring senescence during storage.

Figure 4.

Quantification of mRNA content in platelet concentrates using TO staining: Platelets obtained from healthy donors and stored platelet concentrate units at multiple time points were stained with TO and analyzed by flow cytometry to evaluate RNA content. Populations corresponding to TO^high (M4, representing young, RNA-rich platelets) and TO^low/negative (M1, representing senescent, RNA-depleted platelets) were quantified and expressed as mean ± SEM. The data reveal a progressive reduction in the proportion of young (M4) platelets over the storage period, accompanied by a concomitant increase in aged (M1) platelets. These results demonstrate the effectiveness of TO staining as a sensitive and reliable approach for distinguishing platelet age and monitoring senescence during storage.

Figure 5.

Quantitative analysis of sGPVI in plasma from healthy donors and stored platelet concentrates: (A) sGPVI concentrations were measured in plasma derived from 10 healthy donors and from platelet concentrate units stored under standard blood bank conditions across multiple time points. The results, expressed as mean ± SEM, indicate that sGPVI levels were significantly elevated in stored platelet concentrates by day 6 relative to healthy donor samples. Furthermore, a progressive increase in sGPVI concentration was observed over the storage period, reaching peak levels on day 14. Statistical comparisons were performed using Student’s t-test. (B) A negative correlation was observed between sGPVI concentration (ng/mL) and the surface expression of membrane-bound GPVI (expressed as geometric mean fluorescence intensity), demonstrating that as platelet storage time increased, membrane-bound GPVI levels declined while soluble GPVI levels concurrently rose. These findings suggest that GPVI shedding is enhanced during platelet storage.

Figure 5.

Quantitative analysis of sGPVI in plasma from healthy donors and stored platelet concentrates: (A) sGPVI concentrations were measured in plasma derived from 10 healthy donors and from platelet concentrate units stored under standard blood bank conditions across multiple time points. The results, expressed as mean ± SEM, indicate that sGPVI levels were significantly elevated in stored platelet concentrates by day 6 relative to healthy donor samples. Furthermore, a progressive increase in sGPVI concentration was observed over the storage period, reaching peak levels on day 14. Statistical comparisons were performed using Student’s t-test. (B) A negative correlation was observed between sGPVI concentration (ng/mL) and the surface expression of membrane-bound GPVI (expressed as geometric mean fluorescence intensity), demonstrating that as platelet storage time increased, membrane-bound GPVI levels declined while soluble GPVI levels concurrently rose. These findings suggest that GPVI shedding is enhanced during platelet storage.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |