1. Introduction

Vaccination is one of the most effective public health interventions in human society, credited with the eradication and control of numerous infectious diseases (Nath, 2023; Coccia, 2016). However, vaccine schedules have become increasingly complex and concentrated—especially in the first year of life—with differences in vaccines and doses between countries (CDC, 2025; Coccia, 2021; Coccia and Bellitto, 2018; Institute of Medicine. 2013; National Academies of Sciences, 2024). Nath (2023) acknowledges that while modern vaccines are safe, side effects—including those affecting the nervous system—remain a concern and merit ongoing surveillance. Doja and Roberts (2006) emphasize that rigorous epidemiological methods are essential to guide evidence-based health policies. Mawson and Jacob (2025) suggest that concentration of vaccines and preterm birth may interact to increase risks of adverse effects (Institute of Medicine, 2012), but in literature lacks a standardized metric to quantify this relationship (cf., National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, 2025). Surveillance systems and WHO’s global pharmacovigilance programs are essential, but they must be complemented by proactive research directed to improve vaccine scheduling, reducing vaccine concentration and possible neurodevelopmental outcomes by balancing vaccine administration in infancy (Institute of Medicine, 2004; Magazzino et al., 2022; Coccia, 2022; 2022a, 2022b, 2023). Children in modern society receive more vaccines at earlier ages than ever before (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, 2024). In many countries, including the United States and Japan, infants are administered up to 20 doses of vaccines covering 13 or more diseases before their first birthday (CDC, 2025; Japanese Pediatric Society, 2025). Although vaccination is an effective public health intervention, these intensive immunization schedules (having a concentrated administration from 0 to 12 months of different vaccines in childhood) may trigger neurodevelopmental outcomes and other size effects (Institute of Medicine, 20024, 2012; Mawson & Jacob, 2025; National Academies of Sciences, 2024). A main gap in literature is the lack of a standardized metric to assess vaccine exposure intensity in infants, in particular an index that can assess the concentration and cumulative vaccine exposure in early infancy by integrating three key dimensions: the number of vaccines, the intensity of doses, and the age at administration. Without such a tool, it is difficult to compare vaccine schedules in infants between countries to evaluate the potential impact on possible neurodevelopmental outcomes and other size effects. In this context, the main research question guiding this study is:

Can an age-adjusted vaccine exposure index serve as a valid and reliable tool for improving infant immunization schedules across countries, thereby reducing early-life vaccine concentration and supporting healthier outcomes in population?

Answering this question has significant implications for both scholars and health policymakers. For researchers, this index provides a new methodological approach to study vaccine safety, neurodevelopment, and public health outcomes. For policymakers, it offers a data-driven foundation for improving immunization schedules to align them with epidemiological evidence. This study addresses that question and gap in literature by proposing the Age-adjusted Vaccine Exposure Index (VEI) —a composite measure that captures the number of vaccines and timing of administration in infants ≤1 year, offering a measure of early-life vaccine concentration. The proposed age-adjusted vaccine exposure index (VEI) is designed in a way that is comparable across countries. In particular, VEI mainly incorporates, total number of vaccines administered before 12 months and the age (months in infants) at administration of these vaccines. By aggregating these variables, the VEI provides a simple an interpretable score that reflects the intensity and timing of vaccine exposure in infancy. This index can be used to compare countries, assess trends in vaccination over time, and evaluate associations with neurodevelopmental outcomes. The goal of this research is fundamentally to inform safer and developmentally sensitive vaccination policies that unequivocally maintain or enhance comprehensive immunization coverage while diligently minimizing potential adverse effects, particularly neurological ones, through optimized scheduling. Hence, the core scientific contribution of this study is the introduction of the Vaccine Exposure Index (VEI)—a novel, standardized metric designed to precisely quantify the intensity of cumulative vaccine exposure in infants less than one year old. This metric fills a significant and crucial methodological gap in the current scientific literature, which predominantly focuses only on national coverage rates and lacks the tools to assess the developmental burden of varying immunization schedules. The VEI is not a tool for questioning vaccine coverage, but a simple mechanism for optimization. By allowing for cross-country benchmarking and identification of "best practices" (where high coverage is achieved with lower early-life exposure intensity), this study directly aligns with recent calls from public health authorities for enhanced vaccine safety surveillance and evidence-based health policy reform, ultimately aiming to bolster public trust and ensure the long-term sustainability of comprehensive, early-life immunization programs in society. Nath (2023) argues that there is an urgent need for coordinated global action involving manufacturers, healthcare agencies, scientists, and legislators to investigate vaccine-related neurological adverse events and develop strategies to prevent them, improving national immunization program schedules in countries. The VEI can serve as a valuable tool in this effort in order to identify high-risk schedules, monitor trends, and design interventions that balance disease prevention with neurodevelopmental safety. The introduction of the VEI aims to optimize vaccine scheduling, not to question safety or advocate reduction in vaccine use. It has significant implications for public health, such as countries with high VEI scores may consider revising their vaccine schedules to reduce dose intensity in the first year of life in infants (Ramachandran and Grose, 2024). The Vaccine Exposure Index (VEI) is also an essential tool that enables robust international comparisons (global benchmarking) and the identification of best practices—those successful models that achieve and sustain high vaccination coverage and public safety while minimizing early-life vaccine intensity (GBD, 2023; Haeuser et al., 2025). By addressing a critical gap in the existing literature and providing a standardized framework for evidence-based cross-national analysis, the VEI directly contributes to health policy optimization grounded in the foundational necessity of high vaccination coverage. It links this coverage with enhanced vaccine safety, offering a mechanism to minimize neurodevelopmental disorders by adjusting administration timing and scheduling. Overall, while vaccines are unequivocally essential for public health, optimizing their administration—especially in the timing and concentration in the first year of life—is a necessary step that may help reduce potential side effects and support healthier developmental outcomes. Hence, the VEI offers a scientifically rigorous path forward for researchers, clinicians, and policymakers seeking to achieve a superior balance between maximum immunization efficacy and enhanced neurological safety in society, ultimately reinforcing the long-term public acceptance and success of comprehensive immunization programs.

Next section describes the conceptual framework of vaccinometrics with proposed age-adjusted vaccine exposure index (VEI) in immunization schedule for infants to 12 months and an empirical evidence of this index considering the autism spectrum disorder (ASD) between countries, a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by impairments in social interaction, communication, and behavior, which has seen a marked rise in prevalence globally (Talantseva et al., 2023; Grosvenor et al., 2024). Research supports that autism is primarily a genetic condition, with minimal influence from environmental factors (National Academies of Sciences, 2025). For example, Bailey et al. (1995) demonstrated that monozygotic twins show a significantly higher concordance rate for autism compared to dizygotic twins, indicating a strong genetic basis. These findings suggest that genetic predisposition plays a role in autism development, while environmental contributions can be limited or non-causal. Despite many studies show no causal link between vaccines and autism (Gulati et al., 2025; National Academies of Sciences, 2025), the global prevalence of autism spectrum disorder in children is increasing (Issac et al., 2025) and environmental and healthcare-related exposures—including concentration of vaccines in nation childhood immunization schedules—have been proposed as possible contributing factors. Some scientific investigations have identified statistical associations between vaccine dose intensity and ASD incidence, particularly in high-income countries (Mawson and Jacob, 2025; Nath, 2023; Ramachandran and Grose, 2024). This study uses ASD as a case study to verify the goodness of proposed VEI directed to assess vaccination policies and some effects of intensive immunization schedules in countries. Therefore, discussions about vaccine timing and exposure should not be interpreted as implying causation between immunization and autism, as current scientific consensus attributes autism to genetic determinants. In short, proposed approach here is directed to optimize vaccine administration in immunization scheduling, not to advocate reduction in vaccine coverage.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Indicators of Vaccinometrics and Mathematical Formulation of Proposed Age-Adjusted Vaccine Exposure Index (VEI)

The components of age-adjusted vaccine exposure index (VEI) in immunization schedule for infants to 6 and 12 months in country are defined mathematically as follows.

- ○

Monthly vaccine exposure in infants (MVL)

These indicators indicate monthly vaccine exposure of infants in the proposed index VEI, as a consequence MVL6 months and MVL12 months are the numerator in the equations (eqs. 9-10).

- ○

Average Age of infants during vaccination (AA)

These indicators are used to normalize vaccinations in infants in the proposed index VEI, as a consequence AA6 months and AA12 months are the denominator in the next equations (eqs. 9-10).

Other useful indicators of vaccinometrics are:

- ○

Average number of vaccines (AV)

- ○

Average number of vaccine doses (AD)

The proposed age-adjusted vaccine exposure index (VEI) measures vaccine exposure in infants by combining two key indicators just defined: the monthly vaccine exposure serves as the numerator (eqs 1-2), while the average age of infants during immunization (eqs. 3-4) acts as the denominator, normalizing exposure across age groups. Mathematically,

Hence, this analytical approach provides a standardized metric for evaluating vaccine exposure in early infancy and enables the design of VEI for assessing childhood immunization schedules at 6 and 12 months, referred to as

VEI6 and

VEI12 given by:

Where:

= Total monthly vaccine exposure administered from birth to 6 months.

= Total monthly vaccine exposure administered from birth to 12 months.

and = Average age of infants during vaccination in respective periods.

The VEI index has the following property:

- ○

Lower VEI indicates a lower concentration of vaccines in childhood immunization schedule of country

- ○

Higher VEI indicates a higher concentration of vaccines in childhood immunization schedule of country

The age-adjusted vaccine exposure index (VEI) is an increasing function from the value 0 (no vaccination and vaccine exposure in infants) to higher values, indicating a high vaccine exposure (vaccines × doses) in infants to 6 and 12 months. Moreover, VEI is not intended to model immunological mechanisms such as immune memory, cross-reactivity, or trained immunity. Rather, it serves as a comparative metric for evaluating vaccine scheduling intensity across countries during the first year of life. The index accounts for the number, timing, and concentration of vaccine doses, providing a standardized measure of early-life vaccine exposure. This quantitative approach robustly supports essential cross-country analysis and crucial health policy evaluation without, in any way, questioning the commitment to comprehensive vaccine coverage. Consequently, the VEI provides a unique, evidence-based tool for enhanced surveillance, offering a structured framework for monitoring and strategically mitigating potential developmental risks associated with intense early-life scheduling. The central, novel perspective of this study is to strongly encourage a scientifically grounded shift toward developmentally sensitive immunization strategies. This strategy seeks to expertly balance the paramount goal of disease prevention (maintaining or improving high vaccine coverage) with the commitment to long-term neurological health. In doing so, the VEI lays vital groundwork for future studies directed at rigorously optimizing the health policies governing national immunization program schedules across all countries, ensuring both maximum public health protection and enhanced vaccine safety.

2.2. Data and Empirical Evidence to Validate Age-Adjusted Vaccine Exposure Index (VEI)

This study applies the age-adjusted vaccine exposure index (VEI) to real-world immunization schedules from a sample of 12 countries to evaluate its effectiveness and validate its utility as a surveillance tool directed to optimize vaccine scheduling. While most vaccination metrics focus on population-level coverage, VEI introduces an individual-scale measure of early-life vaccine exposure, considering the number, intensity, and timing of doses during the first year of life. By calculating VEI scores for national schedules, the study identifies patterns in vaccine concentration and age distribution, enabling cross-country comparisons. VEI suggests that countries with higher scores often administer more vaccines at younger ages, including birth doses. VEI can serve as a proxy for exposure intensity and help assess whether scheduling practices align with developmental immunology principles. The Vaccine Exposure Index (VEI) absolutely does not question or advocate for a reduction in vaccine coverage. Instead, it provides a structured, quantitative framework for optimizing the timing and concentration of vaccination doses with the explicit dual goal of minimizing potential neurodevelopmental risks while rigorously maintaining maximum disease prevention. By applying the VEI to diverse, real-world immunization schedules globally, this study demonstrates its practical potential for guiding evidence-based, scientifically informed policy adjustments. Hence, this study lays the essential groundwork for implementing developmentally sensitive immunization strategies, ensuring that national programs can achieve superior safety and efficacy, thereby sustaining high public confidence and comprehensive coverage.

2.3. Sample of Countries for Empirical Evidence

The validation of the proposed age-adjusted vaccine exposure index (VEI) in infant immunization schedules (0–12 months) is done measuring concentration of vaccines in infants and using Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) as a reference condition of possible disorders. Although extensive research shows no causal link between vaccines and ASD (Gulati et al., 2025), some studies report statistical associations between vaccine dose intensity and ASD prevalence, especially in high-income countries (Mawson and Jacob, 2025; Nath, 2023). Given the global rise in ASD (Talantseva et al., 2023; Grosvenor et al., 2024), this study evaluates VEI’s effectiveness across countries to assess whether intensive childhood immunization schedules having a concentration of vaccines to 12 months correlates with differential levels of ASD in countries. This study is based on real data from national immunization schedules in a sample of advanced countries, comparable for public health sector and policy, with varying autism prevalence: Singapore, South Korea, Japan, Australia, Canada, the United States, Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Finland, Italy, and the United Kingdom. These countries were selected because they share similar diagnostic standards for autism, maintain a low threshold for diagnosis, and offer high-quality healthcare systems. Additionally, their immunization programs are broadly comparable, making them suitable for cross-country analysis of vaccine scheduling patterns and early-life exposure. As specific cases, we also analyze India and China, two large and high populated countries, different from our basic sample for their socioeconomic indicators, to assess robustness of proposed index VEI.

2.4. Empirical Data and Sources for Statistical Analysis

The data and sources are indicated in

Table 1 with specific variables used and their definitions.

2.5. Statistical Analysis Procedure to Validate Proposed Age-Adjusted Vaccine Exposure Index (VEI)

The analysis is based on the mentioned sample of countries, analyzing all information in table 1 from national immunization schedules in countries. The study design focuses on logical groupings for measuring the proposed vaccinometrics and the index VEI in infants, and whether statistical evidence supports the hypothesis that the autism incidence between countries can be explained by the level of vaccine exposure index in infants (concentration of manifold vaccines). The first categorization under study to assess the proposed age-adjusted vaccine exposure index (VEI) in infant immunization schedules (0–12 months) is between:

- ○

Higher Autism rate countries: Singapore, South Korea, Japan, Australia, Canada, USA (see, World Population Review, 2025).

- ○

Lower Autism rate countries: Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Finland, Italy, UK (see, World Population Review, 2025).

The study design also focuses on other logical groupings to analyze the VEI index, considering:

- ○

countries that administer vaccines at birth versus other that start later

- ○

countries that administer vaccine for varicella, hepatis B and Japanese encephalitis versus other countries that do not consider these vaccines in the childhood vaccination schedule.

Firstly, the variables in

Table 1 are analyzed with descriptive statistics given by arithmetic mean, standard deviation, skewness and kurtosis to assess the distributions and their normality. Variables with non-normal distribution are transformed into log-scale, to have a normal distribution for appropriate and robust parametric analyses.

Secondly, proposed metrics for infants ≤1 year and less than 6 months, were also analyzed using the Independent Samples t-Test to determine whether there was statistical evidence that the associated means over time are significantly different between the two main reference groups (countries with higher vs. lower average values of autism rate per 100k people). The hypotheses used for the Independent Samples t-Test are:

H’0: µ1 = µ2, the two-population means of groups are equal between

H’1: µ1 ≠ µ2, the two-population means of groups are not equal

Thirly, partial correlation between autism rate 2021 per 100k people and proposed metrics (controlling % vaccination rate for diptheria, tetanus, and pertussis, measles and polio disease), with test of significance having one-tailed, is applied.

Fourthly, an analysis of dependence was performed using a series of linear regression models for the overall sample given by 12 countries. The linear model of simple regression considers the autism rate 2021 per 100k as a function both of monthly vaccine exposure to 12 months in infants or age-adjusted vaccine exposure index (VEI). The basic linear model is:

y = dependent variable (log Autism rate 2021 per 100k)

x= explanatory variable: log monthly vaccine exposure to 12 months in infants or log age-adjusted vaccine exposure index (VEI)

α = constant; β = regression coefficient; u = error term; i= countries

The model is extended with a multivariate regression considering the Autism rate per 100k people on explanatory variables given simultaneously by both age-adjusted vaccine exposure index and % vaccination rate for diptheria, tetanus, and pertussis, measles and polio disease. The specification of the

log-

log model is:

where:

y = Autism rate per 100k people, dependent variable

x1 = age-adjusted vaccine exposure index (VEI) to 12 months

x2 = Vaccination rate for Diptheria, Tetanus, and Pertussis, Measles and Polio diseases

u =error term, i=country.

Graphical representation of the regression line is basic lo locate countries in the space, also considering a vertical and horizontal lines indicating average values of variables. These lines create four quadrants. Each quadrant is labeled with a policy implications. Statistical analyses are done with SPSS software 29.00.

3. Results

Descriptive statistics in

Table 2 shows arithmetic mean and standard deviation of basic variables and vaccinometrics under study here in countries categorized per main groups and if some types of vaccines are or not administered. First of all, group of countries having a higher average of autism rate of 1273.33 per 100,000 people, called higher autism rate countries, vs. the second group that has a lower average rate of autism (834.44 per 100k people), shows a marginal higher percent vaccination rate for diseases (diptheria, tetanus, and pertussis, measles and polio) of 95% vs. 94.5%; moreover average age of infants during the vaccination by 12 months, according to national immunization program schedules in these countries, is lower (4.9 months) in the group with higher average rate of autism (results also show that average age of infants during the vaccination by 6 months is lower −3.09 months− always in countries having higher average rate of autism). As far as total average number of vaccines and doses to 12 months, in countries having a higher autism rate is higher with about 15 vaccines and 20 doses vs. 8 vaccines and 9 doses in countries with a lower autism rate; whereas average number of vaccines and doses to 6 months has a similar situation: in higher autism rate countries is higher (about 10 vaccines and 15 doses vs. 9 vaccines and 6.5 doses in countries with a lower autism rate). Moreover, countries having a higher autism rate administer about 1.2 vaccines and 1.64 doses per month by 1 year in infants vs. 0.7 vaccines and 0.8 doses per month in infants of countries with lower autism rate; in the period of 6 months, similar situation. This result generates an average monthly vaccine exposure to 12 months (vaccines × doses / 12 months) in infants of countries having a higher autism rate of about 24.3 vs. about 7 in infants of countries with lower autism rate, whereas average monthly vaccine exposure to 6 months (vaccines × doses / 6 months) in infants of countries having a higher autism rate is about 24.2 vs. about 8.4 in infants of countries with lower autism rate. The combined vaccine exposure index to 12 months in infants (VEI12), which is a main synthesis of these metrics based on both vaccine exposure and average age of infants according to the immunization program schedule, shows in countries with higher autism rate an average value of 5, whereas VEI12 is 1.25 in lower autism rate countries. VEI at 6 months in countries with higher autism rate is 8 vs. 3 in lower autism rate countries. The comparative analysis considering other logical categorization shows the following results. We report only the index VEI at 12 months for the sake of briefness. For details see

Table 2. Countries that do not vaccine at the birth have a VEI12=1 vs. VEI12=5 in countries that vaccine at birth; moreover, countries that do not administer varicella vaccine have a VEI12=1 vs. VEI12=4.6 (higher vaccine exposure) in countries that administer this vaccine; countries that do not administer hepatitis B vaccine have a VEI12=1.2 vs. VEI12=4.01 (higher vaccine exposure) in countries that administer it. Finally two countries (South Korea and Japan) administer also Japanese encephalitis vaccine, results show a very high average VEI12=5.8 (high vaccine exposure) associated with one of the highest incidence of autism rate worldwide (1450 per 100k people; World Population Review, 2025). In short, countries with a higher rate of autism tend to have a lower average age of infants during vaccine administration according to national immunization schedule and a higher average number of vaccines and doses (high concentration), including vaccination at birth, varicella and hepatitis B vaccines, which generate a higher early-life vaccine exposure both a 6 and 12 months. As a consequence VEI provide a main proxy of possible risks of adverse effects in infants having less than or equal to 1 year, when undergoing to a high concentration of vaccines.

In

Table 3, except vaccination rate total and average age infants vaccinated to 6 months, the statistical analysis of the Independent Samples Test has significance levels with

p-value < .001,

p-value < .01 or

p-value < .05 in variables under study, as a consequence we can reject the null hypothesis, and conclude that the mean of proposed metrics for the group of higher autism rate countries is significantly different and higher than second group including countries with lower autism rate per 100k people.

Partial correlation in

Table 4 shows that Autism rate per 100k people (controlling vaccination rate % rate for diptheria, tetanus, and pertussis, measles and polio diseases in population) has a negative significant coefficient with average age in infants vaccinated to 12 months (r=−0.71,

p-value< 0.01): i.e., vaccinations in younger infants are associated with a high ASD risk; whereas it has a positive significant coefficient with total vaccines done to 12 months (r=0.87,

p-value< 0.001), with total vaccines done to 6 months (r=0.77,

p-value< 0.01), with total doses done to 12 months (r=0.79,

p-value< 0.01), with total doses done to 6 months (r=0.80,

p-value< 0.001), with total vaccine exposure to 12 months (r=0.85,

p-value< 0.001), with total vaccine exposure to 6 months (r=0.83,

p-value< 0.001), and especially with vaccine exposure index (VEI) to 12 months (r=0.85,

p-value< 0.001) and with vaccine exposure index (VEI) to 6 months (r=0.80,

p-value< 0.001): i.e., concentration of vaccines in infants having less than 12 months is associated with a higher autism risk. In short,

Table 4 about the relationship between variables and test of association suggests that rates of autism tend to have a negative correlation with average age of infants during vaccinations at 12 months and a positive association with average number of vaccines and doses at 6 and 12 months, and proposed vaccine exposure index (VEI) at 6 and 12 months: therefore concentration of vaccines at younger infants seems to be associated with a higher autism risk.

Parametric estimates in

Table 5 of the linear model based on autism rate as function of monthly vaccine exposure in infants to 1 year (

log-log model) show that a 1% increase in the monthly vaccine exposure to infants ≤ 1 year, it increases the level of autism rate by 0.16% (

p-value 0.05). Estimated relation based on autism rate as function of vaccine exposure index (VEI) in infants to 1 year also shows that a 1% increase in this VEI index (that combines monthly vaccine exposure index and average age of infants ≤ 1 year), it increases the level of autism rate by 0.14% (

p-value 0.05). Multivariate regression also in

Table 5 shows stronger results. Partial coefficient of vaccine exposure index in infants ≤ 1 year (controlling vaccination rate for diptheria, tetanus, and pertussis, measles and polio diseases) suggests that a 1% growth, it increases the autism rate per 100k people by 0.16 (

p-value 0.001). The coefficient of determination R

2 explains about 78% of the variance in the data. The

F ratio of the variance explained by the model to the unexplained variance is significant (

p-value<0.001), then predictors reliably predict response variable (i.e., autism rate). These results seem to show a main relation of autism rates increases driven by a high concentration of vaccines and related doses to infants ≤ 1 year.

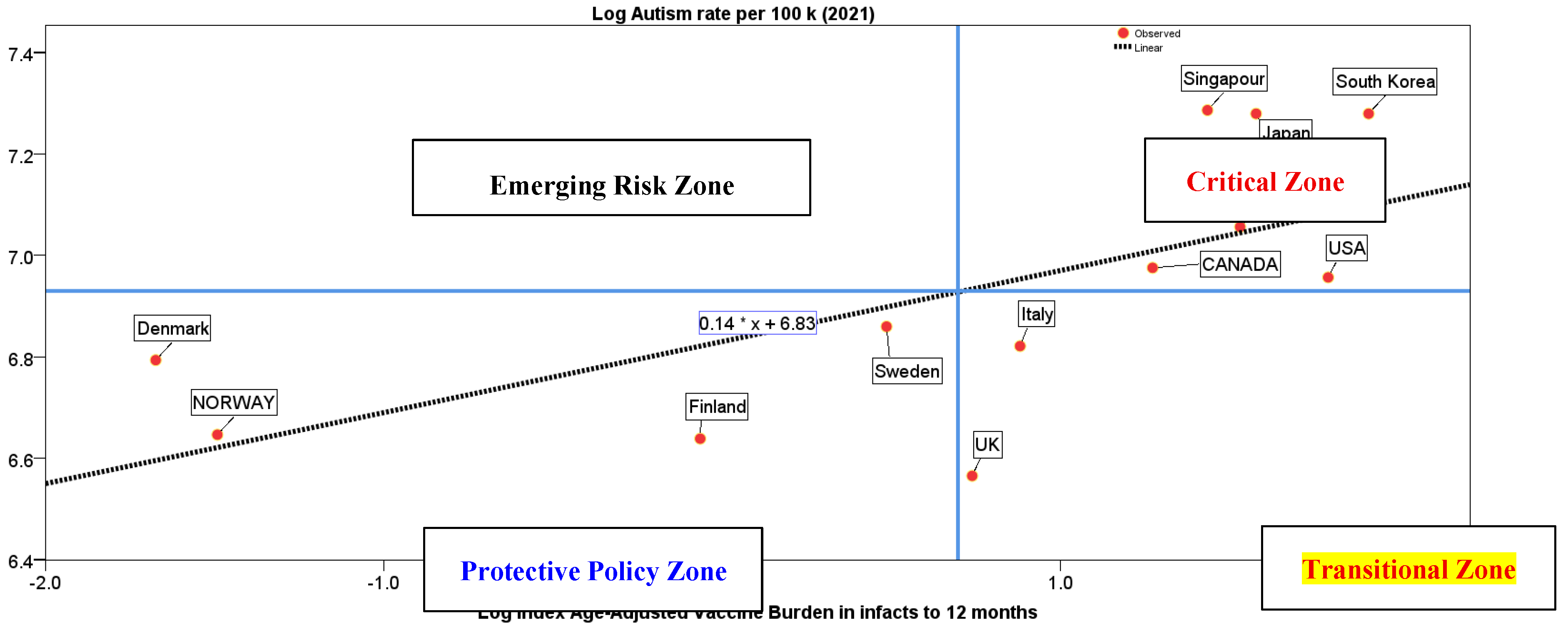

Figure 1 shows the graphical representation of the relation of autism rate on vaccine exposure index in infants ≤ 1 year with the location of countries under study.

Figure 1 also has vertical and horizontal lines indicating average values that create 4 quadrants. Countries are concentrated in three main quadrants.

Figure 1 presents a compelling visual analysis of the relationship between the Age-adjusted Vaccine exposure Index (VEI) and autism rates in infants ≤1 year across a sample of countries. The scatterplot is divided into four quadrants by vertical and horizontal lines representing the average values of VEI and autism incidence. This quadrant-based categorization reveals distinct patterns in national immunization strategies and their potential associations with neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Bottom-Left Quadrant (Low VEI, Low Autism Rate) includes countries such as Norway, Denmark, Finland, and Sweden. These nations administer fewer vaccine doses in the first year of life and exhibit lower autism rates. These Scandinavian countries with lower VEI scores demonstrate that high immunization coverage can be achieved without early and intensive vaccine schedules. These nations delay non-critical vaccines, avoid vaccination at birth, and exclude certain vaccines like varicella and hepatitis B from the first months of life. Their approach aligns with developmental biology and supports healthier neurodevelopmental outcomes, as suggested by Mawson and Jacob (2025), who emphasize the importance of timing in vaccine exposure. In short, these countries demonstrate that it is possible to maintain high vaccination coverage while minimizing early-life vaccine exposure. Their policies reflect a cautious approach that prioritizes long-term neurological health alongside disease prevention. These countries serve as models for developmentally sensitive immunization strategies. Their schedules could inform revisions in countries with higher VEI scores.

Top-Right Quadrant (High VEI, High Autism Rate). Countries including Australia, Canada, the United States, Singapore, Japan, and South Korea are positioned here. These nations administer a higher number of vaccine doses to infants under one year, often starting at birth, and show above-average autism rates. Their schedules tend to be more intensive, with early and frequent vaccinations (Frenkel, 2021). These countries with high VEI scores often administer multiple vaccines to 0-6 months and maintain dense schedules through the first year. While these programs aim to maximize protection, they may inadvertently increase the risk of adverse effects, particularly in vulnerable populations. In the U.S., autism prevalence rose from 1 in 150 children in 2000 to 1 in 31 by 2022 (CDC, 2025a). During this period, the infant immunization schedule expanded from approximately 11 vaccines to 15 before age one (CDC, 2025b). This intensification of early-life vaccine exposure may contribute to neurodevelopmental stress, particularly in vulnerable populations. International trends mirror this trajectory. Australia’s infant schedule increased from about 9 vaccines in 1994 to 14 in 2025, especially for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children (Australian Government, 2025). Japan’s 2025 schedule includes early administration of BCG, DPT-IPV-Hib, and pneumococcal vaccines, with multiple doses before 6 months (Japan Pediatric Society, 2025; Japan, 2025). While these programs aim to maximize protection against infectious diseases, the elevated VEI scores suggest a greater early-life vaccine exposure, which may warrant further investigation into potential neurodevelopmental risks, especially in vulnerable populations. Health policy reassessment in these nations should consider delaying non-essential vaccines, reducing dose intensity, and tailoring schedules for at-risk infants, such as those born preterm or with a family history of neurodevelopmental disorders. The VEI enables cross-country comparisons for optimizing vaccine schedules to balance efficacy and safety. Hence, by integrating VEI into national health planning, policymakers can identify high-vaccine exposure schedules, monitor trends, and design interventions that reduce early-life vaccine exposure. As Doja and Roberts (2006) argue, evidence-based policy must be grounded in rigorous epidemiological analysis—precisely what the VEI enables. Ultimately, the VEI supports a shift from one-size-fits-all immunization toward personalized, developmentally informed vaccination strategies, improving both safety and public trust (Coccia, 2023, 2022, 2022a).

Bottom-Right Quadrant (High VEI, Low Autism Rate). Italy and the United Kingdom occupy this quadrant. Although their autism rates are below the average, their VEI scores are relatively high. In particular, Italy’s 2025 schedule shows early and intensive vaccine administration, including hexavalent vaccines and MenB within the first months. Vaccines in national immunization program schedules of these countries have considerably increased compared to 1980s-2000s period (Italy, 2025). This positioning may indicate a transitional phase in vaccine policy, with tendencies toward more intensive schedules and critical zone. These countries could benefit from re-evaluating their immunization strategies, potentially aligning more closely with the Nordic model to reduce early-life exposure without compromising coverage. A Surveillance Enhancement health policy can be integrating VEI into existing pharmacovigilance systems to improve early detection of adverse trends and support evidence-based policy reform.

Top-Left Quadrant (Low VEI, High Autism Rate). Notably, no countries in the study fall into this quadrant. This absence reinforces the hypothesis that higher vaccine exposure may be associated with higher autism rates, although causality cannot be inferred.

In brief, the VEI provides a powerful tool for evaluating and improving infant immunization schedules. This study suggests that vaccine efficacy and safety can be balanced through thoughtful scheduling. VEI application can optimize vaccine scheduling, minimize potential side effects, and guide global health policy toward more balanced and individualized vaccination strategies for a vast and safe coverage in society. As Doja and Roberts (2006) emphasize, rigorous epidemiological methods are essential to disentangle associations and inform evidence-based policy.

4. Discussion

This study introduces the age-adjusted Vaccine Exposure Index (VEI) as a crucial, novel metric specifically engineered to optimize national immunization schedules by adjusting the timing and intensity of doses without, under any circumstances, compromising the essential goals of vaccine safety or comprehensive vaccine coverage to face diseases. The empirical evidence analyzes national immunization schedules from a group of 12 advanced countries: Singapore, South Korea, Japan, Australia, Canada, the United States, Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Finland, Italy, and the United Kingdom. These countries were selected because they share similar diagnostic standards and criteria for autism, maintain a low threshold for diagnosis and high-quality healthcare systems. The immunization programs of these advanced countries are broadly comparable, making them suitable for cross-country evaluation of early-life vaccine exposure and meaningful comparisons of scheduling intensity and timing using the VEI without confounding factors such as limited healthcare access or inconsistent reporting. Highly populated countries such as India and China were excluded from the main analysis to avoid distortions in statistical analysis. However, a preliminary comparison of these two countries having the majority of the global population reveals notable differences. According to World Population Review (2025), autism rate per 100,000 population is estimated at 484 in China and 509 in India. Vaccination coverage in 2023 for DTP3 (diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis), Polio (POL3) and MCV1 (measles) was 97% in China and slightly lower in India (91% for DTP3 and Polio, 93% for MCV1). Immunization schedules indicate that by 12 months, infants in China typically receive about 10 vaccines and 12 doses (Chinese CDC, 2021), whereas in India, the vaccination schedule includes approximately 14 vaccines and 19 doses (Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, 2018). These basic information show that India has a higher autism prevalence, although causality is not implied, reflecting greater cumulative exposure in vaccines compared to China (

Table 6).

These preliminary results underscore the potential of a comparative tool for evaluating vaccine scheduling intensity and guiding developmentally sensitive immunization strategies across diverse health systems. The findings suggest that countries with higher autism prevalence tend to exhibit elevated VEI values, reflecting concentrated vaccine administration at younger ages and higher dose intensity (Casey et al., 2020). To reiterate, while these results do not establish causality, they highlight the importance of considering developmental immunology when designing vaccination schedules. The findings based on statistical evidence here suggest that early and intensive vaccine exposure may be associated with increased autism prevalence, although causality is not claimed. In fact, regression models provide additional insight. Multivariate regression, controlling for core vaccination rates, shows a 0.16% increase in autism rate per 1% rise in VEI. These findings align with existing literature that has explored the potential neurodevelopmental effects of vaccine exposure. Tomljenovic and Shaw (2011) raised concerns about aluminum adjuvants in vaccines and their role in neuroimmune disorders. Ramachandran and Grose (2024) documented rare but serious neurological events following varicella vaccination, while Mawson and Jacob (2025) suggested that cumulative exposure may interact with developmental vulnerabilities. In general, the infant immune system is still developing during the first year of life, and exposure to multiple immunological stimuli in a short timeframe could potentially influence neurodevelopment in vulnerable populations (Shapiro et al., 2021; Tomljenovic & Shaw, 2011). In particular, the concept of proposed age-adjusted vaccine exposure (VEI) aligns with emerging insights into immune ontogeny. Brophy-Williams et al. (2021) emphasize that the neonatal immune system undergoes rapid maturation, and early antigen exposure can shape lifelong immune trajectories. This underscores the need for developmentally sensitive scheduling, as timing influences both protective efficacy and immune programming. Similarly, Pasetti et al. (2020) demonstrate that maternal immunity and early-life exposures interact to determine infant immune responses, reinforcing the rationale for balancing vaccine timing with physiological readiness. From a mechanistic perspective, Garcia-Fogeda et al. (2023) review within-host antibody dynamics, showing that immune responses vary significantly with age and prior exposures. High-intensity vaccination in the first months may alter antibody kinetics, potentially affecting long-term immunity. Instead, Pollard and Bijker (2021) further argue that vaccination policies must integrate principles of immunological development to optimize outcomes, a goal consistent with the VEI framework. Recent work on immune response variability across the life course (Metcalf et al., 2025) suggests that early immune experiences can lead to convergence or divergence in later responses, influencing susceptibility to disease and possibly neurodevelopmental trajectories. While the debate on vaccines and autism remains contentious, these findings support continued investigation into how exposure patterns and concentration of vaccines in childhood immunizations—not vaccine presence per se—might interact with neurodevelopmental processes. Technological advances offer opportunities to refine such analyses. Anderson et al. (2025) and Elfatimi et al. (2025) highlight the role of computational tools and AI in modeling vaccine effects and predicting outcomes, which could enhance the predictive power of indices like VEI. Moreover, predictive markers of immunogenicity (Van Tilbeurgh et al., 2021) and exposome-based immunity training (Adams et al., 2020) suggest that exposure order and intensity matter for immune system calibration, lending theoretical support to the idea of adjusting schedules to reduce clustering of doses in early infancy.

The study here highlights the importance of considering vaccine timing and intensity in immunization policy (Hughes et al., 2016). By integrating vaccine concentration and age, it offers a practical tool for surveillance and evidence-based scheduling adjustments. This proposed approach here seeks to harmonize disease prevention with developmental health, advancing a paradigm of precision vaccinology. Hence, these insights are valuable for researchers, clinicians, and policymakers seeking to balance the benefits of immunization with the imperative of neurological safety.

5. Conclusions

The introduction of the age-adjusted vaccine exposure index (VEI) provides a novel framework for complementing global efforts to optimize immunization strategies. The larger significance of this vaccine exposure index (VEI) as a novel and standardized metric is to fill a critical gap in the literature, where most studies have focused on vaccine efficacy and population-level coverage, but few have addressed the individual-level intensity and timing of vaccine administration during the most sensitive stages of neurodevelopment in infants. By integrating the number of vaccines, doses, and age of administration, the VEI provides a comprehensive measure of early-life vaccine exposure, enabling researchers and policymakers to assess the developmental appropriateness of national immunization schedules. This approach responds to growing concerns in the scientific community about the potential impact of early and intensive vaccine exposure on neurodevelopmental outcomes, especially in vulnerable populations like preterm infants (Davis et al., 1999; Fortmann et al., 2022; Schmitt et al., 2025). In fact, immunization programs, such as those in the United States, Japan, etc. have historically prioritized high coverage and disease prevention (Roper et al., 2021), yet recent discourse and proposed VEI index here emphasize tailoring schedules to developmental immunology. This aligns with Sustainable Development Goals, where immunization is recognized as a cornerstone of child health and equity (Decouttere et al., 2021). Modeling studies underscore the complexity of immune system development and vaccine response. Morrocchi et al. (2024) highlight in vitro models that simulate neonatal immune responses, revealing that timing and antigen load significantly influence immunogenicity. These findings support the rationale behind VEI, which integrates age and vaccine intensity to monitor exposure patterns. Similarly, Pickering et al. (2020) stress that vaccine licensure and recommendations must consider evolving evidence on safety and efficacy, reinforcing the need for adaptive scheduling frameworks. Safety remains a critical dimension of immunization policy. Conklin et al. (2021) review historical vaccine safety concerns, noting that transparent surveillance tools are essential for maintaining public trust. VEI serves this role by enabling cross-country comparisons and identifying schedules with concentrated early exposure, which may warrant further evaluation. Moreover, maternal immunization strategies—advocated by Quincer et al. (2024) and Santilli et al. (2025)—illustrate how timing adjustments can enhance infant protection without reducing coverage, a principle consistent with VEI’s objectives. Global health frameworks emphasize leveraging vaccines to reduce antimicrobial resistance (Vekemans et al., 2021), underscoring the importance of maintaining robust immunization while refining schedules for developmental sensitivity. The VEI reframes the research problem by shifting the focus from binary debates about vaccine safety to a quantitative, comparative, and developmental perspective. This reframing opens new perspectives for research, including personalized immunization strategies, and cross-national benchmarking of best practices (Kargı and Coccia, 2024; Coccia, 2023; Rodewald et al., 2023; Shattock et al. 2024). In particular, the age-adjusted vaccine exposure index (VEI) goes beyond traditional linear parameters such as the number of vaccines or antigen quantity administered in infancy. While these metrics provide a basic measure of immunization intensity, they fail to capture the complex immunological processes that shape early-life immune development. VEI introduces a multidimensional perspective by integrating timing, dose concentration, and age-adjusted exposure, offering insights into how clustered vaccinations may interact with critical developmental stages. By quantifying exposure, VEI provides a proxy for evaluating these complex interactions indirectly. High VEI values indicate schedules with concentrated early dosing, which could intensify immune programming effects. This does not imply risk or causality but highlights the need for developmentally sensitive scheduling that considers immunological plasticity during infancy. By integrating epidemiological patterns with immunological modeling, VEI offers a data-driven approach to harmonize disease prevention and long-term health, paving the way for precision vaccinology and informed policy reforms. Thus, VEI complements existing vaccinology principles by bridging quantitative measures with qualitative aspects of immune system maturation, supporting a more holistic approach to immunization policy. For policymakers globally, the VEI offers a highly practical and powerful tool for evidence-based reform. Its specific aim is to optimize the timing and administration of vaccine and immunization scheduling by strategically maintaining high, comprehensive coverage while simultaneously reducing the intensity of early-life vaccine exposure. This dual-focus approach has the potential to minimize adverse effects, crucially leading to significantly improved public trust in national immunization programs. In doing so, this research contributes fundamentally to a more robust, balanced, and developmentally informed approach to global vaccination policy, ensuring that essential disease protection is achieved with the highest possible standards of safety and public confidence (Benati and Coccia, 2022; Kargı et a., 2023).

5.1. Health Policy Implications of This Study

The age-adjusted vaccine exposure index (VEI) is not merely an analytical metric; it is a practical tool intended to inform immunization policy and promote developmentally sensitive strategies. By quantifying cumulative vaccine exposure in infants under one year, VEI enables policymakers to evaluate the intensity of national schedules and identify opportunities for optimization. This approach moves beyond coverage rates to address how vaccine clustering and early administration may interact with infant immune development. The health policy implications of this study are substantial, offering a new framework for evaluating and improving national immunization schedules through the proposed age-adjusted vaccine exposure index (VEI).

Figure 1 illustrates how countries cluster into distinct quadrants based on their VEI scores and autism rates. Countries such as Norway, Denmark, Finland, and Sweden, located in the bottom-left quadrant, exemplify best practices. These nations maintain high vaccination coverage while minimizing early-life vaccine exposure through delayed administration of non-critical vaccines and lower dose intensity. Their developmentally sensitive schedules suggest that it is possible to balance disease prevention with long-term neurological health. In contrast, countries in the top-right quadrant—including Australia, Canada, the United States, Singapore, Japan, and South Korea—administer a higher number of vaccines and doses at earlier ages, often starting at birth. These intensive schedules are associated with higher VEI scores and elevated autism rates, raising concerns about potential neurodevelopmental risks, especially in vulnerable populations. While these programs aim to maximize protection, they may benefit from reassessing the timing and intensity of vaccine delivery. Italy and the United Kingdom, positioned in the bottom-right quadrant, show relatively high VEI scores but lower autism rates. This aspect may reflect a transitional phase in policy, suggesting an opportunity to align more closely with Nordic models to reduce early-life exposure without compromising coverage in order to optimize vaccine scheduling.

Generally speaking, VEI supports several health policy applications. First, it can guide adjustments in vaccine spacing, reducing concentrated dosing during critical developmental windows without compromising protection. Second, it helps prioritize at-risk infant groups, such as those with prematurity or underlying conditions, by tailoring schedules to minimize early-life exposure intensity. Third, VEI allows policymakers to evaluate cumulative exposure thresholds, ensuring that schedules remain within developmentally appropriate limits. VEI index also facilitates comparative analysis of national schedules, enabling countries to benchmark their practices against models with lower VEI scores—such as Scandinavian nations that achieve high coverage while delaying non-essential vaccines and avoiding birth doses. Integrating VEI into WHO and national guidelines would advance precision vaccinology, harmonizing disease prevention with long-term health. Currently, global recommendations prioritize coverage and disease prevention, but they rarely account for cumulative exposure intensity during critical developmental phases in infants. VEI could serve as an analytical tool within existing frameworks, complementing WHO’s principles of safety, efficacy, and equity. For example, national immunization technical advisory groups (NITAGs) could use VEI to evaluate proposed schedules, identifying periods of concentrated dosing and assessing whether adjustments—such as delaying non-essential vaccines beyond the neonatal phase—might reduce theoretical risks without compromising protection. This proposed approach aligns with WHO’s emphasis on adaptive strategies for diverse populations and supports harmonization across countries by enabling cross-schedule comparisons. Furthermore, VEI could be integrated into digital health platforms and surveillance systems, providing policymakers with real-time insights into exposure patterns and facilitating predictive modeling for long-term outcomes. In short, the Vaccine Exposure Index (VEI) provides the necessary quantitative evidence to fundamentally shift immunization policy away from a rigid, one-size-fits-all approach and firmly toward personalized, evidence-based vaccination policies. These strategies are meticulously designed to rigorously maintain the highest possible immunization coverage for the population while simultaneously optimizing scheduling to respect the critical principles of developmental biology—thereby ensuring both comprehensive disease prevention and enhanced safety for every child.

These implementations in best practices of public health and practical policy implications are also supported by the fact that VEI fully respects ethical principles by relying exclusively on publicly available data from national immunization schedules. No individual-level or sensitive health information is used, ensuring compliance with privacy and confidentiality standards. This proposed approach guarantees transparency and reproducibility, as all calculations are based on standardized, open-access sources. Furthermore, the fundamental purpose of the Vaccine Exposure Index (VEI) is unequivocally not to question or undermine comprehensive coverage, but rather to furnish policymakers with a robust, evidence-based tool for optimizing immunization strategies in a meticulously developmentally sensitive and safety-conscious manner. The ethical integrity of this metric also extends to fostering essential stakeholder engagement. By presenting results in a transparent, clear, and comparative format, the VEI facilitates constructive dialogue among health authorities, pediatric experts, public health organizations, and the public. Its potential integration into key decision-making frameworks—such as WHO guidelines or national technical advisory groups—would directly support inclusive, data-driven policy development. This ensures that any recommendations derived from the VEI are strongly grounded in rigorous scientific evidence and are perfectly aligned with global health priorities, including equity and the paramount goal of universal disease prevention. To put it differently, the VEI promotes responsible innovation in vaccinology by enabling crucial cross-country benchmarking and identifying validated best practices that achieve safety and high coverage, all without imposing reductionist or prescriptive changes to essential immunization programs. The goal of VEI is improving public health outcomes while maintaining trust in immunization programs. Overall, then, policymakers can use the Vaccine Exposure Index (VEI) to benchmark immunization schedules, identify practices with high cumulative vaccine exposure, and design interventions that minimize early-life exposure in infants under 12 months. This approach also encourages reconsidering the routine addition of every newly approved vaccine to schedules within the first year of life, helping to avoid excessive concentration and potential related risks. In this policy perspective, countries with lower VEI scores, such as those in Scandinavia, demonstrate that high coverage can be achieved with less intensive schedules, offering models for reform. As a consequence, the VEI thus supports a shift toward personalized, developmentally informed immunization strategies, enhancing both safety and public trust in vaccination programs.

5.2. Limitations and Future Prospects

To conclude, this study introduces the age-adjusted vaccine exposure index (VEI) as a novel metric to quantify early-life vaccine exposure in infants under 12 months, offering a standardized framework for comparing national immunization schedules. The findings, based on empirical evidence, suggest that early and intensive vaccine schedules may be associated with increased neurodevelopmental risks, although causality is not claimed. However, this study has some limitations. First, the analysis is based on cross-sectional data of a small sample of countries and two large nations that needs to be extended to confirm the predictions and policy implications of proposed metrics and theoretical framework. Second, autism prevalence data may vary in accuracy and diagnostic criteria between and within countries, potentially affecting comparability. Third, the VEI does not yet account for individual-level factors, such as genetic susceptibility or preterm birth, which may influence neurodevelopmental outcomes (Pichichero, 2014; Sadeck and Kfouri, 2023). Future research should explore longitudinal studies to examine the effects of vaccine timing and intensity over time and space in a large sample of countries, particularly in vulnerable populations. Additionally, integrating individual-level health data with national immunization schedules could refine the VEI and support personalized vaccine strategies. These directions would strengthen the evidence base and enhance the utility of the VEI as a policy tool for improving public health policies in global vaccination practices while safeguarding infant health in society.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: References of National Immunization Program Schedules for countries under study.

Author Contributions

Mario Coccia “Conceptualization; methodology; software; validation; formal analysis; investigation; data curation; writing—original draft preparation; writing—review and editing; visualization; supervision.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request to the authors..

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VEI |

Age-adjusted Vaccine exposure Index |

References

- Adams, K.; Weber, K.S.; Johnson, S.M. Exposome and immunity training: How pathogen exposure order influences innate immune cell lineage commitment and function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5-TR (5th edition, text revision); American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, L.N.; Hoyt, C.T.; Zucker, J.D.; McNaughton, A.D.; Teuton, J.R.; Karis, K.; Arokium-Christian, N.N.; Warley, J.T.; Stromberg, Z.R.; Gyori, B.M.; et al. Computational tools and data integration to accelerate vaccine development: challenges, opportunities, and future directions. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1502484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australia (2025) Australian Government, Department of Health, Disability and Ageing, National Immunization Program for children. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/topics/immunisation/when-to-get-vaccinated/national-immunisation-program-schedule, https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2025-09/national-immunisation-program-schedule_0.pdf.

- Australian Government (1999) Department of Health and Aged Care, Communicable Diseases Intelligence. In n. 6 - 10 June 1999, Immunisation coverage in Australian children: a systematic review 1990-1998 – Appendix; Volume 23. Available online: https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/cda-pubs-cdi-1999-cdi2306-cdi2306a7.htm (accessed on October 2025).

- Bailey, A.; Le Couteur, A.; Gottesman, I.; Bolton, P.; Simonoff, E.; Yuzda, E.; Rutter, M. Autism as a strongly genetic disorder: evidence from a British twin study. Psychol. Med. 1995, 25, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benati, I.; Coccia, M. Global analysis of timely COVID-19 vaccinations: improving governance to reinforce response policies for pandemic crises. Int. J. Heal. Gov. 2022, 27, 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brophy-Williams, S.; Fidanza, M.; Marchant, A.; Way, S.; Kollmann, T.R. One vaccine for life: Lessons from immune ontogeny. J. Paediatr. Child Heal. 2021, 57, 782–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canada (2025), Government of Canada, Recommended immunization schedules: Canadian Immunization Guide. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/canadian-immunization-guide-part-1-key-immunization-information/page-13-recommended-immunization-schedules.html#p1c12a2.

- Benzaken, C.L.; Miller, J.D.; Onono, M.; Young, S.L. Development of a cumulative metric of vaccination adherence behavior and its application among a cohort of 12-month-olds in western Kenya. Vaccine 2020, 38, 3429–3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çatlı, N.E.; Özyurt, G. The relationship between autism and autism spectrum disorders and vaccination: review of the current literature. Trends Pediatr. 2025, 6, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Data and Statistics on Autism Spectrum Disorder. 27 May 2025. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/autism/data-research/index.html#cdc_data_surveillance_section_3-cdcs-addm-network.

- CDC. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). 2025a. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/autism/data-research/index.html#cdc_data_surveillance_section_3-cdcs-addm-network (accessed on October 2025).

- CDC. Recommended Childhood Immunization Schedule -- United States, 2000. 2025b. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm4902a4.htm (accessed on October 2025).

- Chinese center for disease control and prevention. 2021. Available online: https://en.chinacdc.cn/health_topics/immunization/202203/t20220302_257317.html.

- Coccia, M. Problem-driven innovations in drug discovery: Co-evolution of the patterns of radical innovation with the evolution of problems. Heal. Policy Technol. 2016, 5, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M. Effects of human progress driven by technological change on physical and mental health. Studi Di Sociol. 2021, 2021, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M. COVID-19 in society between 2020 (without vaccinations) and 2021 (with vaccinations): A case study. Journal of Social and Administrative Sciences. J. Adm. Soc. Sci. – JSAS 2022, 9, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M. Improving preparedness for next pandemics: Max level of COVID-19 vaccinations without social impositions to design effective health policy and avoid flawed democracies. Environ. Res. 2022, 213, 113566–113566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coccia, M. COVID-19 pandemic over 2020 (with lockdowns) and 2021 (with vaccinations): similar effects for seasonality and environmental factors. Environ. Res. 2022, 208, 112711–112711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coccia, M. Optimal levels of vaccination to reduce COVID-19 infected individuals and deaths: A global analysis. Environ. Res. 2021, 204, 112314–112314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M. Relation between COVID-19 vaccination and economic development of countries. Turk. Econ. Rev. 2022, 9, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M. COVID-19 Pandemic Crisis: Analysis of origins, diffusive factors and problems of lockdowns and vaccinations to design best policy responses Vol.2; (e-Book); KSP Books: Kadikoy, Istanbul, Turkey, 2023; ISBN 978-625-7813-54-9. [Google Scholar]

- Coccia, M. COVID-19 Vaccination is not a Sufficient Public Policy to face Crisis Management of next Pandemic Threats. Public Organ. Rev. 2022, 23, 1353–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M.; Bellitto, M. Human progress and its socioeconomic effects in society. J. Econ. Soc. Thought 2018, 5, 160–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conklin, L.; Hviid, A.; A Orenstein, W.; Pollard, A.J.; Wharton, M.; Zuber, P. Vaccine safety issues at the turn of the 21st century. BMJ Glob. Heal. 2021, 6, e004898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.L.; Rubanowice, D.; Shinefield, H.R.; Lewis, N.; Gu, D.; Black, S.B.; DeStefano, F.; Gargiullo, P.; Mullooly, J.P.; Thompson, R.S.; et al. Immunization Levels Among Premature and Low-Birth-Weight Infants and Risk Factors for Delayed Up-to-Date Immunization Status. JAMA 1999, 282, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decouttere, C.; De Boeck, K.; Vandaele, N. Advancing sustainable development goals through immunization: a literature review. Glob. Heal. 2021, 17, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denmark. Statens Serum Institut. Childhood vaccination programme. 2025. Available online: https://en.ssi.dk/vaccination/the-danish-childhood-vaccination-programme.

- Doja, A.; Roberts, W. Immunizations and Autism: A Review of the Literature. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. / J. Can. des Sci. Neurol. 2006, 33, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elfatimi, E.; Lekbach, Y.; Prakash, S.; BenMohamed, L. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in the development of vaccines and immunotherapeutics—yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Front. Artif. Intell. 2025, 8, 1620572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estes, A.; Munson, J.; Rogers, S.J.; Greenson, J.; Winter, J.; Dawson, G. Long-term outcomes of early intervention in 6-year-old children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2015, 54, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finland. Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare. Vaccination programme for children and adults. 2025. Available online: https://thl.fi/en/topics/infectious-diseases-and-vaccinations/information-about-vaccinations/vaccination-programme-for-children-and-adults.

- Fortmann, M.I.; Dirks, J.; Goedicke-Fritz, S.; Liese, J.; Zemlin, M.; Morbach, H.; Härtel, C. Immunization of preterm infants: current evidence and future strategies to individualized approaches. Semin. Immunopathol. 2022, 44, 767–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frenkel, L.D. The global burden of vaccine-preventable infectious diseases in children less than 5 years of age: Implications for COVID-19 vaccination. How can we do better? Allergy Asthma Proc. 2021, 42, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Fogeda, I.; Besbassi, H.; Larivière, Y.; Ogunjimi, B.; Abrams, S.; Hens, N. Within-host modeling to measure dynamics of antibody responses after natural infection or vaccination: A systematic review. Vaccine 2023, 41, 3701–3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeuser, E.; Byrne, S.; Nguyen, J.; Raggi, C.; A McLaughlin, S.; Bisignano, C.; A Harris, A.; E Smith, A.; A Lindstedt, P.; Smith, G.; et al. Global, regional, and national trends in routine childhood vaccination coverage from 1980 to 2023 with forecasts to 2030: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2023. Lancet 2025, 406, 235–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Santomauro, D.F.; E Erskine, H.; Herrera, A.M.M.; Miller, P.A.; Shadid, J.; Hagins, H.; Addo, I.Y.; Adnani, Q.E.S.; Ahinkorah, B.O.; Ahmed, A.; et al. The global epidemiology and health burden of the autism spectrum: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Psychiatry 2024, 12, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosvenor, L.P.; Croen, L.A.; Lynch, F.L.; Marafino, B.J.; Maye, M.; Penfold, R.B.; Simon, G.E.; Ames, J.L. Autism Diagnosis Among US Children and Adults, 2011-2022. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2442218–e2442218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulati, S.; Sharawat, I.K.; Panda, P.K.; Kothare, S.V. The vaccine–autism connection: No link, still debate, and we are failing to learn the lessons. Autism 2025, 29, 1639–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeuser, E.; Byrne, S.; Nguyen, J.; Raggi, C.; A McLaughlin, S.; Bisignano, C.; A Harris, A.; E Smith, A.; A Lindstedt, P.; Smith, G.; et al. Global, regional, and national trends in routine childhood vaccination coverage from 1980 to 2023 with forecasts to 2030: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2023. Lancet 2025, 406, 235–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlin, P; Magiati, I. Autism spectrum disorder: outcomes in adulthood. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2017, 30, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M.M.; Katz, J.; Englund, J.A.; Khatry, S.K.; Shrestha, L.; LeClerq, S.C.; Steinhoff, M.; Tielsch, J.M. Infant vaccination timing: Beyond traditional coverage metrics for maximizing impact of vaccine programs, an example from southern Nepal. Vaccine 2016, 34, 933–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Institute of Medicine Immunization Safety Review: Vaccines and Autism; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine. Adverse Effects of Vaccines: Evidence and Causality; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine. The Childhood Immunization Schedule and Safety: Stakeholder Concerns, Scientific Evidence, and Future Studies; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issac, A.; Halemani, K.; Shetty, A.; Thimmappa, L.; Vijay, V.; Koni, K.; Mishra, P.; Kapoor, V. The global prevalence of autism spectrum disorder in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osong Public Heal. Res. Perspect. 2025, 16, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Italy (2025), Regione Lombardia, Calendario Vaccinale. Available online: https://www.wikivaccini.regione.lombardia.it/wps/portal/site/wikivaccini/DettaglioRedazionale/vaccinazioni-disponibili/calendario-vaccinale.

- Japan. Changes in the Immunization Schedule Recommended by the Japan Pediatric Society. 2025. Available online: https://www.jpeds.or.jp/uploads/files/20250205_Immunization_Schedule_english.pdf.

- Japanese Pediatric Society. Changes in the Immunization Schedule Recommended. 2025. Available online: https://www.jpeds.or.jp/uploads/files/20250205_Immunization_Schedule_english.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Kargı, B.; Coccia, M.; Uçkaç, B.C. How does the wealth level of nations affect their COVID-19 vaccination plans? Econ. Manag. Sustain. 2023, 8, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargı, B.; Coccia, M. Rethinking the Role of Vaccinations in Mitigating COVID-19 Mortality: A Cross-National Analysis. KMÜ Sosyal ve Ekonomik Araştırmalar Dergisi. KMU J. Soc. Econ. Res. 2024, 26, 1173–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.K.Y.; Weiss, J.A. Priority service needs and receipt across the lifespan for individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2017, 10, 1436–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, C.; Charman, T.; Havdahl, A.; Carbone, P.; Anagnostou, E.; Boyd, B.; Carr, T.; de Vries, P.J.; Dissanayake, C.; Divan, G.; et al. The Lancet Commission on the future of care and clinical research in autism. Lancet 2022, 399, 271–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magazzino, C.; Mele, M.; Coccia, M. A machine learning algorithm to analyse the effects of vaccination on COVID-19 mortality. Epidemiology Infect. 2022, 150, e168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mawson, AR; Jacob, B. 2025) Vaccination and Neurodevelopmental Disorders: A Study of Nine-Year-Old Children Enrolled in Medicaid. Science, Public Health Policy and the Law 6, 55–61. Available online: https://publichealthpolicyjournal.com/vaccination-and-neurodevelopmental-disorders-a-study-of-nine-year-old-children-enrolled-in-medicaid/ (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Metcalf, C.J.E.; Graham, A.L.; Yates, A.J.; Cummings, D.A.T. Convergence and divergence of individual immune responses over the life course. Science 2025, 389, 604–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of health; family welfare. Government of India, National Health Mission, National Immunization Schedule. 2018. Available online: https://nhm.gov.in/New_Updates_2018/NHM_Components/Immunization/report/National_%20Immunization_Schedule.pdf.

- Miravalle, A.A.; Schreiner, T. Neurologic complications of vaccinations. Handb Clin Neurol. 2014, 121, 1549–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrocchi, E.; van Haren, S.; Palma, P.; Levy, O. Modeling human immune responses to vaccination in vitro. Trends Immunol. 2023, 45, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, A. Neurologic Complications With Vaccines: What We Know, What We Don't, and What We Should Do. Neurology 2023, 101, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences; Engineering; and Medicine. Statement on CDC’s Changes to Guidance on Vaccines and Autism. 2025. Available online: https://www.nationalacademies.org/news/statement-on-cdc-s-changes-to-guidance-on-vaccines-and-autism?utm_source=NASEM+News+and+Publications&utm_campaign=b32b20d912-NAP+Mail+New+2025.11.24&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_-1c0f2fa5e6-112916397&mc_cid=b32b20d912&mc_eid=ddceeca657 (accessed on December 2025).

- National Academies of Sciences; Engineering; and Medicine. Guidance on Routine Childhood Immunizations; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences; Engineering; and Medicine. The Comprehensive Autism Care Demonstration: Solutions for Military Families; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences; Engineering; and Medicine. Vaccine Risk Monitoring and Evaluation at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norway. Norwegian Institute of Public Health. Vaccination of children in Norway. [Internet]. Oslo: The Norwegian Directorate of Health; updated Thursday, April 4, 2024 [retrieved Friday, October 3, 2025. 2025. Available online: https://www.helsenorge.no/en/information-in-english/vaccination-of-children/.

- Pasetti, M.F.; Ackerman, M.E.; Hoen, A.G.; Alter, G.; Tsang, J.S.; Marchant, A. Maternal determinants of infant immunity: Implications for effective immunization and maternal-child health. Vaccine 2020, 38, 4491–4494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichichero, M.E. Challenges in vaccination of neonates, infants and young children. Vaccine 2014, 32, 3886–3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, L.K.; Meissner, H.C.; Orenstein, W.A.; Cohn, A.C. Principles of vaccine licensure, approval, and recommendations for use. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2020, 95, 600–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollard, A.J.; Bijker, E.M. A guide to vaccinology: from basic principles to new developments. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 21, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Principi, N.; Esposito, S. Aluminum in vaccines: Does it create a safety problem? Vaccine 2018, 36, 5825–5831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quincer, E.M.; Cranmer, L.M.; Kamidani, S. Prenatal maternal immunization for infant protection: A review of the vaccines recommended, infant immunity and future research directions. Pathogens 2024, 13, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramachandran, P.; Grose, C. Serious neurological adverse events in immunocompetent children and adolescents caused by viral reactivation in the years following varicella vaccination. Rev. Med Virol. 2024, 34, e2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuters. Autism rates: Why are they on the rise. By Nancy Lapid. 17 April 2025. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/why-are-autism-rates-rising-2025-01-14/.

- Rodewald, L.; Maes, E.; Stevenson, J.; Lyons, B.B.; Stokley, S.; Szilagyi, P. Immunization performance measurement in a changing immunization environment. Pediatrics 1999, 103, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roper, L.; Hall, M.A.K.; Cohn, A. Overview of the United States’ Immunization Program. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 224, S443–S451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadarangani, M.; Kollmann, T.; Bjornson, G.; Heath, P.; Clarke, E.; Marchant, A.; Levy, O.; Leuridan, E.; Ulloa-Gutierrez, R.; Cutland, C.L.; et al. The Fifth International Neonatal and Maternal Immunization Symposium (INMIS 2019): Securing Protection for the Next Generation. mSphere 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeck, L.d.S.R.; Kfouri, R.d.Á. An update on vaccination in preterm infants. J. de Pediatr. 2023, 99, S81–S86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandbank, M.; Bottema-Beutel, K.; LaPoint, S.C.; I Feldman, J.; Barrett, D.J.; Caldwell, N.; Dunham, K.; Crank, J.; Albarran, S.; Woynaroski, T. Autism intervention meta-analysis of early childhood studies (Project AIM): updated systematic review and secondary analysis. BMJ 2023, 383, e076733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santilli, V.; Sgrulletti, M.; Costagliola, G.; Beni, A.; Mastrototaro, M.F.; Montin, D.; Rizzo, C.; Martire, B.; del Giudice, M.M.; Moschese, V. Maternal Immunization: Current Evidence, Progress, and Challenges. Vaccines 2025, 13, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, C.; Goedicke-Fritz, S.; Fortmann, I.; Zemlin, M. Vaccinations in preterm infants: Which and when? Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2025, 30, 101670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Real Reasons Autism Rates Are Up in the U.S. By Jessica Wright & Spectrum, March 3. Scientific American. 2017. Available online: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-real-reasons-autism-rates-are-up-in-the-u-s/#.

- Shapiro, G.K.; Kaufman, J.; Brewer, N.T.; Wiley, K.; Menning, L.; Leask, J.; Abad, N.; Betsch, C.; Bura, V.; Correa, G.; et al. A critical review of measures of childhood vaccine confidence. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2021, 71, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shattock, A.J.; Johnson, H.C.; Sim, S.Y.; Carter, A.; Lambach, P.; Hutubessy, R.C.W.; Thompson, K.M.; Badizadegan, K.; Lambert, B.; Ferrari, M.J.; et al. Contribution of vaccination to improved survival and health: modelling 50 years of the Expanded Programme on Immunization. Lancet 2024, 403, 2307–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singapour. Government of Singapore, Communicable Diseases Agency, Vaccinations, Table 1: National Childhood Immunisation Schedule. 2025. Available online: https://www.cda.gov.sg/public/vaccinations and https://isomer-user-content.by.gov.sg/18/00b7fdea-24a1-4c26-b67e-d6618f31d6cb/NCIS_Sept%202025.pdf.

- South Korea. Vaccination for infants, Yangcheon-Gu Office, Seul. 2025. Available online: https://www.yangcheon.go.kr/english/english/04/10402030000002016110903.jsp.

- Sweden. Vaccination programmes. The Public Health Agency of Sweden. 2025. Available online: https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/the-public-health-agency-of-sweden/communicable-disease-control/vaccinations/vaccination-programmes/ (accessed on October 2025).

- Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment. SBU Yellow Report No. 191; Vaccines to Children: Protective Effect and Adverse Events: A Systematic Review [Internet]. Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment (SBU): Stockholm, Feb 2009. [PubMed]

- Talantseva, O.I.; Romanova, R.S.; Shurdova, E.M.; Dolgorukova, T.A.; Sologub, P.S.; Titova, O.S.; Kleeva, D.F.; Grigorenko, E.L. The global prevalence of autism spectrum disorder: A three-level meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1071181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]