1. Introduction

Pediatric palliative care is a multidisciplinary approach aimed at alleviating the physical, psychological, and social suffering of children with life-limiting conditions and supporting their families [

1]. While pediatric palliative care is well established in high-income countries, services in low- and middle-income settings remain underdeveloped [

2].

In Mexico, leading causes of pediatric mortality include cancer, neurological disorders, and congenital anomalies, with respective rates of 5.0, 3.8, and 3.7 deaths per 100,000 children [

3]. Despite this burden, few hospitals offer structured pediatric palliative care programs. Evidence on the benefits of pediatric palliative care for patients and families in low- and middle-income settings remains limited, underscoring the need for longitudinal assessments of quality of life in these populations. Families in these contexts often face additional socioeconomic and logistical stressors that worsen their quality of life.

Although most pediatric palliative care models are cancer-focused, children with other chronic, disabling conditions may have prolonged disease courses and complex care needs that warrant tailored palliative support.

This study aimed to evaluate the quality of life trajectories of patients and their families enrolled in a pediatric palliative care program. Demographic and clinical factors influencing changes in quality of life over time were also examined.

2. Materials and Methods

This prospective cohort study was conducted at the Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez, a tertiary referral center in Mexico City. Children aged 0–18 years with life-limiting or severe disabling conditions were referred to the pediatric palliative care Unit by their treating physicians. The unit offers integrated medical, psychological, and social care, along with home visits and telephone follow-up. Medical equipment is loaned to families in the Mexico City metropolitan area.

Upon enrollment, each family underwent a multidimensional assessment conducted by a pediatrician, psychologist, and social worker. Individualized care plans were developed focusing on symptom control, caregiver education, and coordination with local health services. Baseline information and demographic data were collected at the hospital for every new patient enrolled between 1 July 2021 and 28 February 2025. Follow-up telephone interviews were conducted at 3 and 6 months to assess the quality of life of both patients and their families.

Given the nature of pediatric palliative care populations, follow-up completeness was inherently influenced by disease severity and end-of-life processes, with attrition driven predominantly by mortality. Participant flow diagrams for the full cohort and the oncologic sub-cohort are provided in Figures S1 and S2.

Instruments: Quality of life was assessed using validated Spanish-language instruments: the PedsQL™ 3.0 Cancer Module for children aged 2–18 with cancer, and the

PedsQL™ 2.0 Family Impact Module for caregivers of all patients. Both use a 0–100 scale, with higher scores reflecting better quality of life [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Socioeconomic status was classified using the Mexican Association of Market and Opinion Intelligence (AMAI) index, which categorizes households from D (lowest) to AB (highest) based on education, housing, and access to resources [

12].

Analysis: Participants with more than 20% unanswered questionnaire items were excluded. Descriptive analyses were performed for baseline characteristics. Simple linear regression models were applied to examine associations between demographic and clinical factors and baseline quality-of-life scores, with coefficients reported to reflect the magnitude of differences between comparison groups.

To evaluate longitudinal changes in quality-of-life scores, linear mixed-effects models were fitted. Measurement timepoint (baseline, 3 months, and 6 months) and relevant covariates were included as fixed effects, along with interaction terms to assess whether trajectories differed by key factors. Participant-level random effects were specified using an unstructured covariance matrix. Models were estimated using maximum likelihood. Separate models were specified for each factor potentially associated with quality of life and its rate of change, including age group, sex, diagnostic category (oncologic, neurologic, and other), place of residence (Mexico City metropolitan area vs. non-metropolitan), socioeconomic status (AMAI D vs. higher), and survival time from baseline assessment. Survival time was included as a proxy for clinical status, assuming shorter survival reflected greater disease severity. A multivariable model was then used to assess whether differences in quality-of-life trajectories by place of residence persisted after adjustment for survival time; predicted trajectories are presented graphically.

Survival analysis was conducted using a Kaplan–Meier approach for all participants with available enrollment and exit dates. All analyses and visualizations were performed using Stata/MP version 14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Confidence intervals are reported to convey the precision of estimates.

3. Results

From the total of 183 patients admitted to the Palliative Care Service during the study period, 116 had an oncologic diagnosis and completed at least one PedsQL 3 Cancer Module, and 166 families completed at least one PedsQL Family Impact Module questionnaire. Patient characteristics and baseline scores are reported in

Table 1.

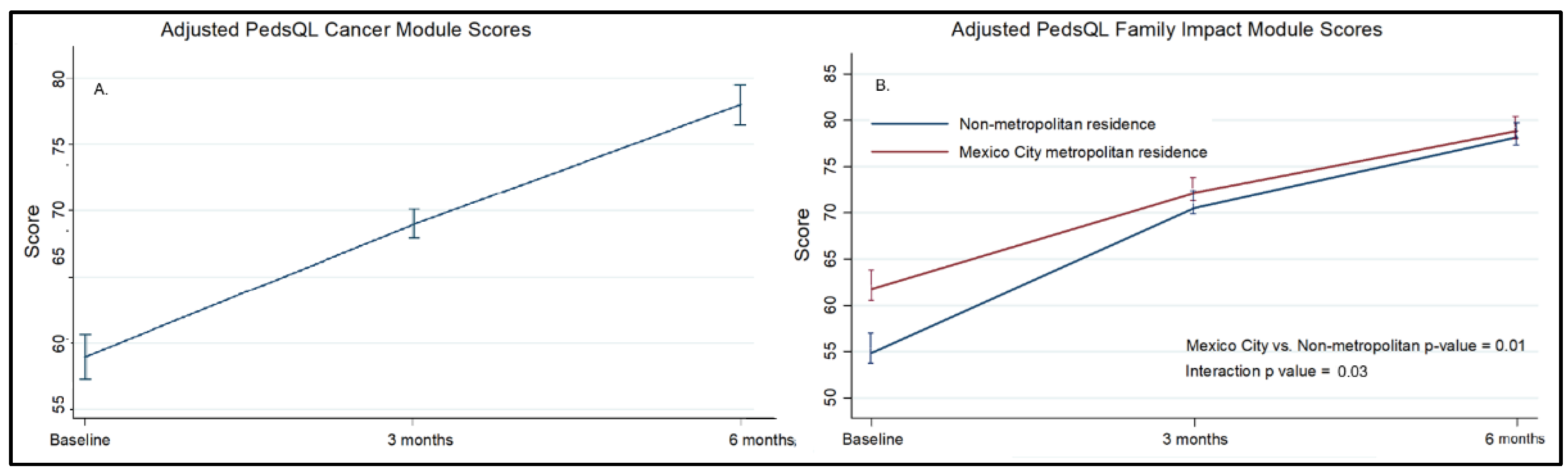

At baseline, the 116 oncologic patients had a mean score of 58.9. At three and six months, scores increased to 68.4 and 77.9, respectively (p < 0.001), with significant improvements observed across all subscales. The domains showing the most significant improvement were pain, procedural anxiety, and communication (

Table 1,

Table 2, and Figure S3).

Participants in the lower socioeconomic strata (AMAI categories D and D+) tended to have statistically non-significant lower baseline PedsQL Cancer Module scores than those in higher AMAI categories (mean difference: -6.32, 95% CI: -15.9 to 3.2). No significant associations were observed between baseline PedsQL Cancer Module scores and sex, age group, neoplasm type, place of residence or survival time (Table S3).

Caregivers of 166 children completed the PedsQL™ 2.0 Family Impact Module. Total scores improved from 60.1 to 78.8 over six months (p < 0.001), with significant gains in the emotional, cognitive, and family relationship domains (Table S2, Figure S4). Families of children in the age group of 5–7 years had lower scores over time (adjusted difference: −8.1, 95% CI: −15.9 to −3.8), as did those with an oncologic diagnosis (adjusted difference: −13.0, 95% CI: −19.6 to −6.3) and families living outside the Mexico City metropolitan area (adjusted difference: −8.6, 95% CI: −14.7 to −2.6). There was a significant interaction between time and location of residence, indicating a higher rate of improvement among families living in non-metropolitan areas (

Table S4). These associations persisted after multivariable analysis (Table S5).

Figure 1.

(A) PedsQL Cancer Module scores over time, adjusted for age. (B) PedsQL Family Impact Module scores over time by place of residence adjusted for age, oncologic diagnosis, and survival < 12 months. Bars represent standard errors. Full models are presented in Table S2 and Table S4.

Figure 1.

(A) PedsQL Cancer Module scores over time, adjusted for age. (B) PedsQL Family Impact Module scores over time by place of residence adjusted for age, oncologic diagnosis, and survival < 12 months. Bars represent standard errors. Full models are presented in Table S2 and Table S4.

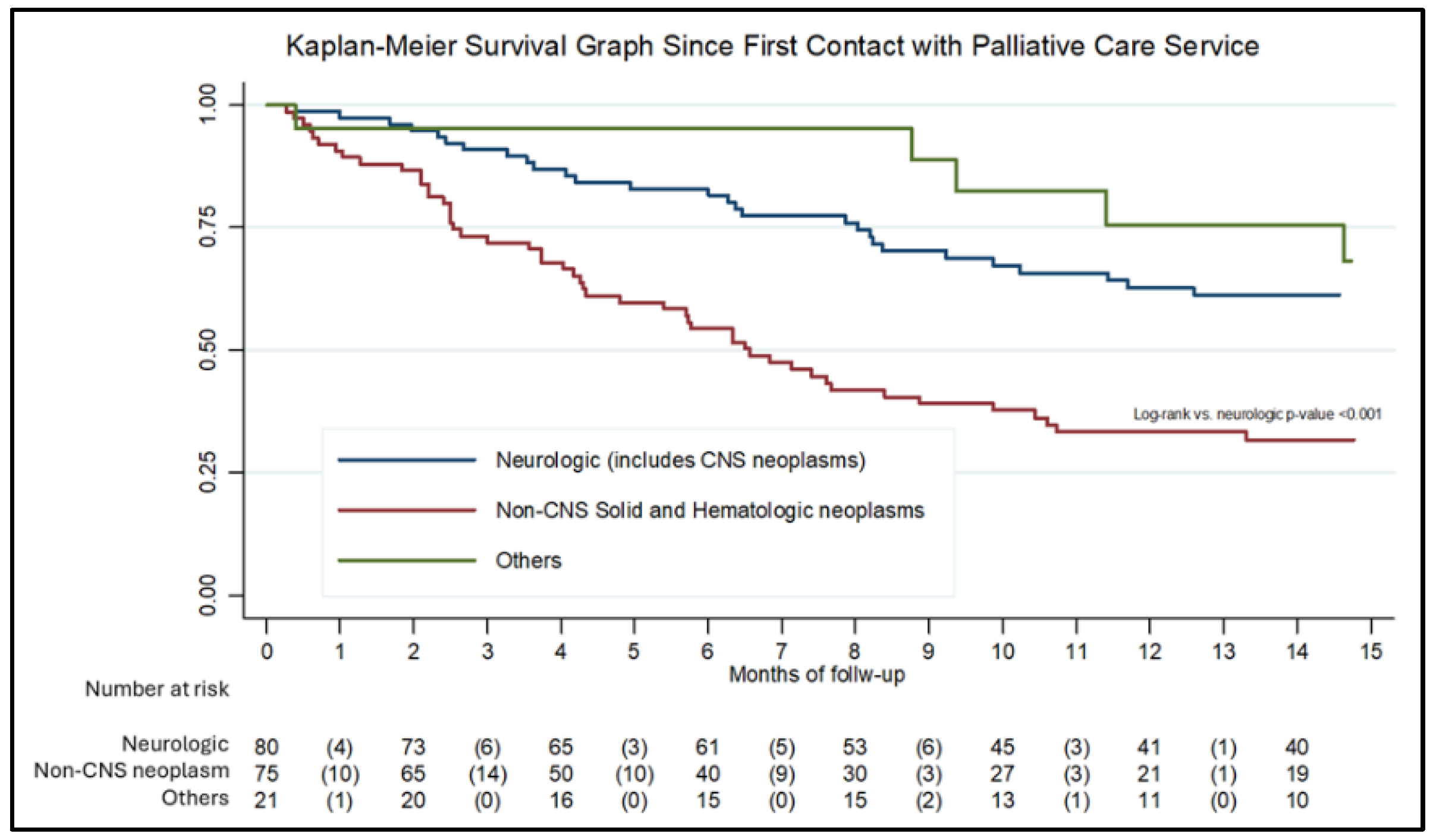

For the survival analysis, 176 records with complete date information were included.

Figure 2 presents the Kaplan–Meier survival curve. Median survival was 11.4 months for the overall cohort, 6.5 months for patients with non-CNS solid or hematologic neoplasms, and 29 months for patients with neurologic conditions, including CNS neoplasms. Most patients (68.7%) died at home, while the remainder died in the hospital. No significant associations were observed between diagnosis, place of residence, or socioeconomic status and the place of death.

4. Discussion

This study describes quality-of-life trajectories following enrollment in a structured pediatric palliative care program in a middle-income country. Overall, we observed improvements in reported quality of life among children and their families over time. These findings are consistent with global data showing that early palliative interventions improve symptom management and reduce psychosocial burden, particularly when care is delivered through multidisciplinary, family-centered models.

An important and unexpected finding was a significantly greater improvement in family quality of life scores among families living outside the Mexico City metropolitan area than among those living closer to the hospital. Although families living farther away had lower baseline scores, this difference in trajectory persisted after adjustment for survival time, which served as a proxy for clinical status. These results suggest that the observed improvement cannot be explained solely by baseline differences or selective mortality. One possible explanation is the reduction in travel burden and hospital visits after enrollment, as well as increased reliance on coordinated care, telephone follow-up, and home-based support. Together, these findings support the decentralization of pediatric palliative care services and highlight the potential role of telehealth and community-based outreach to improve access for families living far from tertiary care centers. Similar strategies involving multidisciplinary teams, local health services, and community participation have shown promising results in other low- and middle-income settings [

13,

14].

Families of children with non-oncologic conditions often face prolonged caregiving demands without clear prognostic timelines. Pediatric palliative care programs should adapt their models to provide sustained, longitudinal support for such populations, beyond the typical oncology-based frameworks.

Consistent with previous reports from high-income settings, our results align with those of Currow et al., who documented improvements in symptom control and patient-reported outcomes following structured, patient-centered palliative care programs [

15]. Similarly, a systematic review by Kaye et al. in pediatric oncologic populations identified enhanced symptom control, reduced intensive procedures, increased advanced care planning, and higher family satisfaction as outcomes associated with specialized palliative care services. These international findings underscore the importance of integrating pediatric palliative care services early in the disease course and tailoring them to the needs of both patients and their families, particularly in resource-constrained settings [

16]. A limitation of our study is the loss to follow-up among some participants.

Our data highlight prolonged survival among a subset of patients, particularly those with neurological disorders. This pattern has important implications for the planning of pediatric palliative care services as it reflects a growing burden of care associated with long-surviving, non-oncologic, and severely disabled patients who require sustained multidisciplinary support over an indefinite period. These findings underscore the need for health systems to recognize and adequately resource pediatric palliative care services not solely for terminal oncologic care but also for the growing population of children living with life-limiting conditions of diverse and often prolonged trajectories.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, this study’s single-arm design precludes causal inference. Second, although overall attrition was substantial, it was driven predominantly by mortality, which is inherent to pediatric palliative care populations. Third, the predominance of oncologic diagnoses may limit generalizability to non-cancer populations, although the inclusion of neurological and other conditions provides essential insight into heterogeneous trajectories of care. Although disease-specific PedsQL modules could provide additional insight into symptom burden among children with non-oncologic conditions, their use was not feasible in this study. The PedsQL Cancer Module was therefore restricted to oncologic patients, while the PedsQL Family Impact Module was applied uniformly to families of both oncologic and non-oncologic patients, reflecting the program’s family-centered approach. These findings underscore the importance of evaluating family outcomes across diagnostic categories and highlight the need for future funding and research to support the use of appropriate quality-of-life instruments in non-oncologic pediatric palliative care.

Despite these limitations, this study has several strengths, including a high follow-up rate among surviving participants, the use of validated Spanish-language instruments, and detailed longitudinal modeling of quality-of-life trajectories. From a policy perspective, our findings highlight the need for health systems to recognize pediatric palliative care not only as end-of-life oncologic care but also as a long-term service for children with diverse, often prolonged, life-limiting conditions. Expanding access to multidisciplinary palliative care, particularly for families outside metropolitan areas, may help reduce inequities and improve the quality of life of children and their caregivers. Future research should focus on identifying and elucidating modifiable components of palliative care programs that best explain improvements in quality of life, and on evaluating the program’s economic impact from families’ perspectives.

5. Conclusions

Pediatric palliative care services were associated with improvements in quality of life among children with life-limiting conditions and their families, especially in those residing outside the hospital’s metropolitan area. These findings highlight the importance of ensuring sustained and equitable access to pediatric palliative care, regardless of diagnosis, geographic location, or socioeconomic background.

Permission for the Use of Instruments

PedsQL™, Copyright © 1998 JW Varni, Ph.D. All rights reserved. Request #135535. For permission and access: Mapi Research Trust, Lyon, France.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: Characteristics of included participants; Table S2: PedsQL TM 3.0 Family Impact Module; Figure S1: PedsQL Cancer Module subscales over 6 months; Figure S2: PedsQL Family Impact subscales over 6 months. Figure S3: Kaplan–Meier survival function by diagnostic classification.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, JHGO and MFCP; methodology, MFCP; formal analysis, MFCP; investigation, MGMM, SEBT, PYM, and KMV; resources, JAGO; data curation MFCP, SEBT, and PYM; writing—original draft preparation, MFCP; writing—review and editing, JHGO; project administration JHGO; funding acquisition, JHGO. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fundación Gonzalo Rio Arronte.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Hospital Infantil de México–Federico Gómez (HIM 2020-013) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all participating caregivers.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff of the Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez for their support and collaboration, as well as all the voluntary staff who support the Palliative Care Service.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMAI |

Mexican Association of Market and Opinion Intelligence |

| CNS |

Central nervous system |

References

- al-Lamki, Z. Improving Cancer Care for Children in the Developing World: Challenges and Strategies. Current Pediatric Reviews 2017, 13, 13–23. [CrossRef]

- Knaul, F.M.; Arreola-Ornelas, H.; Kwete, X.J.; Bhadelia, A.; Rosa, W.E.; Touchton, M.; Méndez-Carniado, O.; Vargas Enciso, V.; Pastrana, T.; Friedman, J.R.; et al. The Evolution of Serious Health-Related Suffering from 1990 to 2021. The Lancet Global Health 2025, 13, e422–e436. [CrossRef]

- Castilla-Peon, M.F.; Rendón, P.L.; Gonzalez-Garcia, N. The Leading Causes of Death in the US and Mexico’s Pediatric Population. Frontiers in Public Health 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Robert, R.; Paxton, R.; Palla, S.; Yang, G.; Askins, M.; Joy, S.; Ater, J. Feasibility, Reliability, and Validity of the PedsQL. Pediatric Blood and Cancer 2012, 59, 703–707. [CrossRef]

- Varni, J.W.; Burwinkle, T.M.; Katz, E.R.; Meeske, K. The PedsQL in Pediatric Cancer. Cancer 2002, 94, 2090–2116. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Zamora, L.M.; Llamas-Peregrina, N.; Lona-Reyes, J.C.; Sánchez-Zubieta, F.A. Calidad de Vida en Niños con Cáncer. Revista Mexicana de Pediatría 2015, 82, 49–56.

- Varni, J.W.; Sherman, S.A.; Burwinkle, T.M.; Dickinson, P. The PedsQL Family Impact Module. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2004, 2, 55. [CrossRef]

- Mano, K.E.; Khan, K.A.; Ladwig, R.J.; Weisman, S.J. Impact of Pediatric Chronic Pain. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 2011, 36, 517–527. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Sun, L.; Wang, B.; Yang, X.; Shang, L.; Zhang, Y. HRQoL in Recurrent Respiratory Infections. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56945. [CrossRef]

- Medrano, G.R.; Berlin, K.S.; Davies, W.H. Utility of the PedsQL Family Impact Module. Quality of Life Research 2013, 22, 2899–2907. [CrossRef]

- Ortega, J.; Vázquez, N.; Caro, A.; Assalone, F. Psychometric Properties of the Spanish PedsQL FIM. Anales de Pediatria 2023, 98, 48-57 http://doi.org/10.1016/j.anpede.2022.10.007.

- Asociación Mexicana de Agencias de Inteligencia de Mercado y Opinión. AMAI 2018. Available online: https://www.amai.org/NSE/ (accessed 30 June 2025).

- Ulloa, Z.G.; García-Quintero, X.; Nakashima-Paniagua, Y.; et al. Community-Based Pediatric Palliative Care in Latin America. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2025, 69, e747–e754. [CrossRef]

- Mosha, N.F.V.; Ngulube, P. Implementing Palliative Care in LMICs. Inquiry: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing 2025, 62. [CrossRef]

- Currow, D.C.; Allingham, S.; Yates, P.; Johnson, C.; Clark, K.; Eagar, K. Improving National Hospice Outcomes. Supportive Care in Cancer 2015, 23, 307–315. [CrossRef]

- Kaye, E.C.; Weaver, M.S.; DeWitt, L.H.; et al. Specialty Palliative Care in Pediatric Oncology. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2021, 61, 1060–1079.e2. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |