A. Dataset

This study uses an open-source anomaly dataset based on the Train Ticket benchmark system as the experimental data source. Train Ticket is a representative microservice application for ticket purchasing. It contains about 41 microservices. These services cover gateways, orders, payments, users, notifications, and other functional components. The system supports containerized and Kubernetes-based deployment. It can effectively simulate cross-service call relationships and runtime fluctuations in real cloud native environments.

Specifically, we adopt the publicly released dataset titled "Anomalies in Microservice Architecture (train-ticket) based on version configurations." The dataset uses Train Ticket as the running platform. It provides multiple anomaly scenarios triggered by changes in versions and dependency configurations. It also collects three key types of observability data in parallel. These include service logs, Jaeger distributed traces, and Prometheus metric data. This design forms a comprehensive monitoring view that covers structural dependencies, temporal evolution, and multi-source signals. The data are organized using a directory schema of "changed microservice_third party library_version_collection date." This structure facilitates mapping anomalies to specific service changes and their impact scope.

The dataset aligns directly with the theme of this paper on microservice anomaly detection based on cross-service temporal contrastive learning. On one hand, logs, metrics, and traces provide natural carriers for cross-service temporal alignment and multi-view augmentation. They support the construction of positive and negative samples at both service and system levels. On the other hand, performance degradation and behavioral anomalies caused by version or dependency changes show clear cross-service propagation and coupling. This property can help the model learn representation boundaries between normal collaborative patterns and abnormal deviation patterns. With open accessibility, complete modalities, and well-defined anomaly causes, this dataset offers a stable and reproducible foundation. It supports the structure, temporal joint modeling, and cross-service alignment learning in our method.

A. Experimental Results

This paper first conducts a comparative experiment, and the experimental results are shown in

Table 1.

In terms of overall performance, the proposed method achieves the best results across all four evaluation metrics. This indicates that cross-service temporal representations and the contrastive learning mechanism can capture collaborative behaviors and anomalous deviations more effectively in microservice systems. Compared with other methods, the advantage of ACC suggests a more stable global identification capability. The model maintains higher classification accuracy under complex dependency structures. This also shows that structured temporal representations play an important role in reducing both false positives and false negatives.

A closer look at Precision shows that the proposed method provides stronger positive discrimination than the other models. This means the model can distinguish normal and abnormal behaviors more precisely under disturbances such as runtime fluctuations and call chain changes. It does not produce excessive false alarms due to local errors or transient resource jitter. For real operational settings, higher Precision is especially valuable. It reduces ineffective alerts and improves the efficiency of operational resource allocation.

The method also remains superior on Recall. This suggests that the cross-service temporal alignment mechanism can describe anomaly propagation with higher sensitivity. It is more likely to capture deeper fault manifestations. Many traditional methods rely more on local service views. They therefore struggle to reflect the temporal transmission characteristics of call dependencies. In contrast, this cross-service contrastive framework can interpret anomalous signals under multi-service interactions in a more comprehensive way. This leads to higher recall.

Finally, the F1-Score further confirms stronger overall performance. It reflects an effective balance between accurate identification and comprehensive coverage. Compared with baseline models, this advantage suggests that cross-service contrastive learning improves representation quality. It also helps establish more robust decision boundaries for mapping anomalies at both service and system levels. Overall, these results indicate that the framework is suitable for complex and dynamic microservice environments. It has the potential to support more reliable anomaly detection and system-level early warning capabilities.

This paper also presents the impact of the learning rate on the experimental results, as shown in

Table 2.

The learning rate sensitivity results show a clear trend. As the learning rate is gradually reduced from 0.0006, the model improves steadily on ACC, Precision, Recall, and F1-Score. This suggests that a higher learning rate makes parameter updates too aggressive. It introduces more structural noise during cross-service temporal feature extraction. The representation space becomes less stable. With a lower learning rate, the model can better exploit cross-service contrastive relations for consistent alignment. This leads to more robust system-level anomaly representations.

The Precision trend further indicates that an overly large learning rate can cause the model to overfit local service patterns. It then fails to capture truly system-correlated anomalous features. When the learning rate falls within 0.0003 to 0.0001, Precision rises noticeably. This implies that the model can achieve more accurate anomaly identification in cross-service collaborative structural representations. This is crucial for reducing false alerts. Microservice systems often experience large business fluctuations. A high false alarm rate can directly undermine the reliability of automated operations.

Recall increases as the learning rate decreases. This indicates that the temporal representations generated by contrastive learning generalize better under lower learning rates. The model becomes more capable of capturing anomaly propagation along call chains. Compared with other training settings, a lower learning rate allows the model to aggregate multi-scale cross-service variations more effectively. This improves coverage of implicit degradation and link-level propagation anomalies.

The F1-Score trend provides a comprehensive view. Model performance becomes more stable as the learning rate decreases. The best balance is achieved at 0.0001 and 0.0002. This suggests that the collaborative representations formed by cross-service temporal contrastive learning benefit from small step updates. The optimization converges more reliably. The model can more fully characterize internal normal patterns and abnormal deviation patterns. This enhances the stability and credibility of anomaly detection decisions.

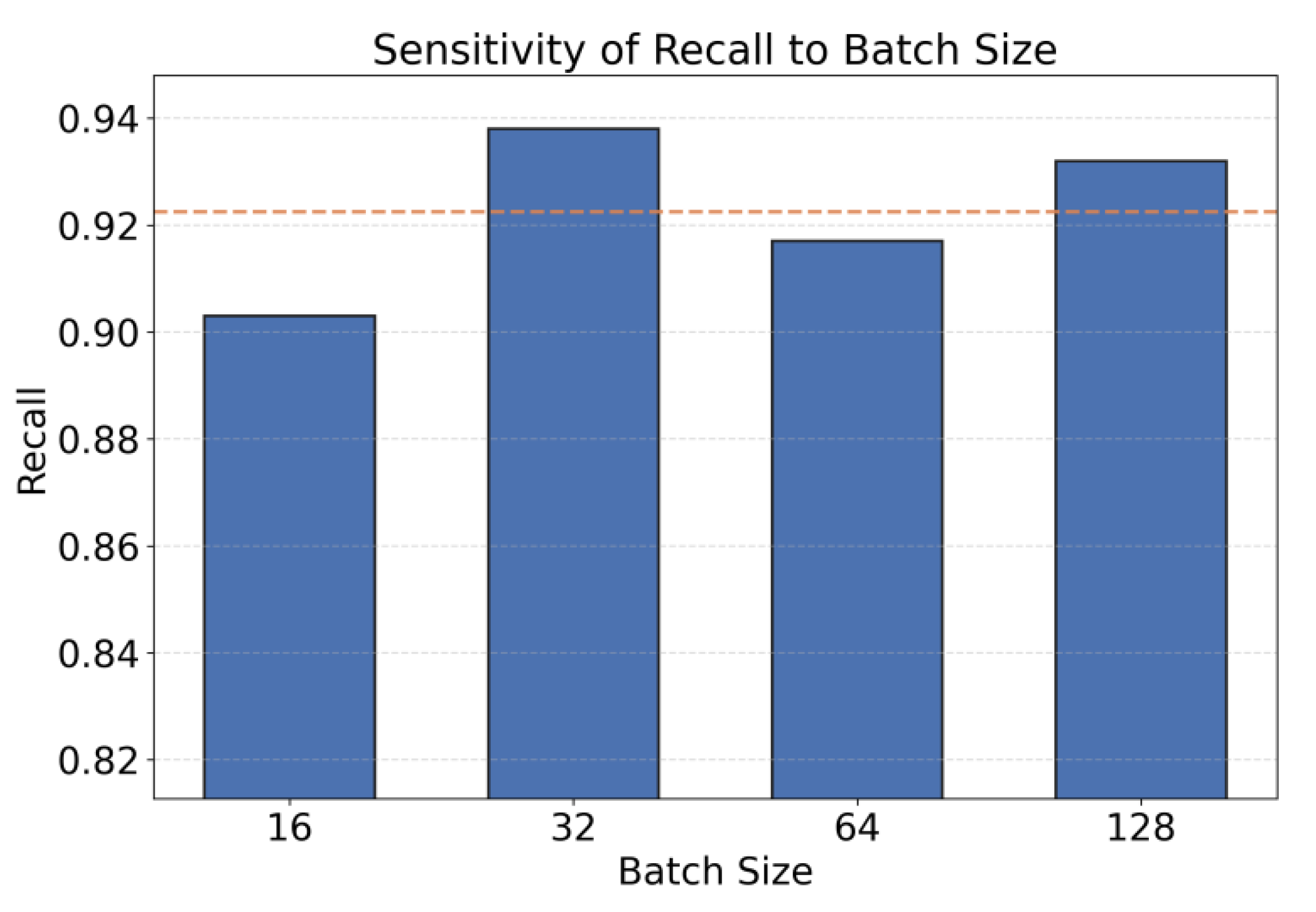

The impact of different batch sizes on cross-service contrastive learning is mainly reflected in two aspects: gradient estimation stability and representation space structure. Smaller batches can introduce more randomness, making cross-service time-series segments exhibit richer perturbation patterns during training, which is beneficial for contrastive learning to uncover more detailed differential features. However, this may also lead to excessively large gradient variance, affecting the stability of optimization convergence. Larger batches tend to provide smoother gradient estimates, enabling cross-service collaborative patterns to form a clearer aggregation structure in the representation space, but there is a risk of decreased sensitivity to local anomaly signals. Therefore, it is necessary to systematically examine the sensitivity of cross-service contrastive learning under different batch sizes, focusing on recall, an indicator that directly reflects anomaly coverage capability, to characterize the balance between "stable training" and "anomaly capture capability," and to provide an operational adjustment basis for hyperparameter configuration in actual deployment. The experimental results are shown in

Figure 2.

The overall trend shows that different batch sizes have a clear impact on recall. This suggests a coupled relationship between the stability of cross-service contrastive learning, the optimization path, and the batch scale. With a larger batch, gradient estimates become smoother. Cross-service collaborative patterns in the representation space are easier to extract. This provides more consistent statistical cues for identifying anomaly propagation paths. Therefore, the model needs a relatively large batch to fully reveal the contribution of cross-service dependency structures to anomaly detection.

When the batch size is adjusted from 16 to 32, recall increases significantly. This indicates that small batches introduce high variance gradients. Such variance can hinder the convergence of the contrastive objective. Stable association patterns among key services then become difficult to form. In contrast, a batch size of 32 offers a more stable update rhythm for service level contrastive relations. It helps the model capture propagation dynamics along call chains. This improves recall.

It is worth noting that recall drops when the batch size increases to 64. This shows that an excessively large batch does not necessarily yield better cross-service anomaly representations. Overly smooth gradient updates may reduce sensitivity to fine-grained anomaly patterns. Some local propagation anomalies may become less visible. This implies that cross-service anomaly detection does not rely only on scaling the batch size. It requires a balance between extracting collaborative structures and preserving sensitivity to details.

When the batch size is further expanded to 128, recall rises again. This suggests that with higher sampling coverage, the overall dependency structure of the system is characterized more completely. The propagation paths of cross-service anomalies are more likely to be captured by aligned representations. This pattern also implies a possible mapping between batch size and dependency complexity. Thus, selecting an appropriate batch scale is an important lever for optimizing the performance of cross-service temporal contrastive learning.

The length of the time window directly determines the range of historical context that the model can observe across service time sequences, thus affecting the discriminability of anomaly patterns and the optimization difficulty of the contrastive learning objective. When the window is too short, the model can only see local fluctuations, making it difficult to perceive delay propagation and multi-scale superposition effects along the service chain; when the window is too long, it may introduce a large amount of background information unrelated to the current anomaly, causing noise interference when the contrastive learning constructs "normal collaborative patterns" and "abnormal deviation patterns" in the representation space. Therefore, it is necessary to systematically examine the sensitivity of a single model on multiple metrics around different time window lengths, and to analyze the nonlinear relationship between window length and cross-service contrastive learning performance through visual line analysis, providing a more operational basis for selecting the granularity of time sequence modeling in microservice anomaly detection. The experimental results are shown in

Figure 3.

These results indicate that the length of the time window has a significant impact on representation stability for cross-service anomaly detection. On ACC, performance increases as the window grows from 16 to 48. It then slightly decreases when the window is further extended to 64 and 80. This pattern suggests two risks. A short window cannot capture the temporal propagation of cross-service dependencies. A long window may introduce noisy information and weaken structured linkage signals. Therefore, the time window should balance the coverage of temporal information and the level of noise. This balance is necessary to realize the advantage of contrastive learning for cross-service behavior modeling.

The changes in Precision and Recall show that the middle range performs best. This indicates that a moderate window helps the model distinguish normal collaborative patterns from abnormal deviation paths. When the window is too small, the main issue is insufficient information. The model cannot reveal cascading propagation among microservices. When the window is too large, it includes a longer history. It may also introduce background changes that are unrelated to the current anomaly. This can reduce discriminative capacity. This observation reflects the core value of cross-service contrastive learning. It does not depend only on local samples. It relies on multi-scale real collaborative behaviors. It also needs to avoid interference from irrelevant context.

Finally, the F1 trend shows that a window length of 48 achieves a more balanced overall performance. This highlights an important point for cross-service anomaly detection. Temporal modeling should not pursue longer ranges without restraint. In systems with complex call structures, a moderate window is more conducive to learning stable service correlation features. This suggests that time scale selection is closely related to the model's ability to capture anomaly propagation. Optimizing the time window from a system perspective is an important support for improving robustness and generalization in cross-service contrastive learning frameworks.

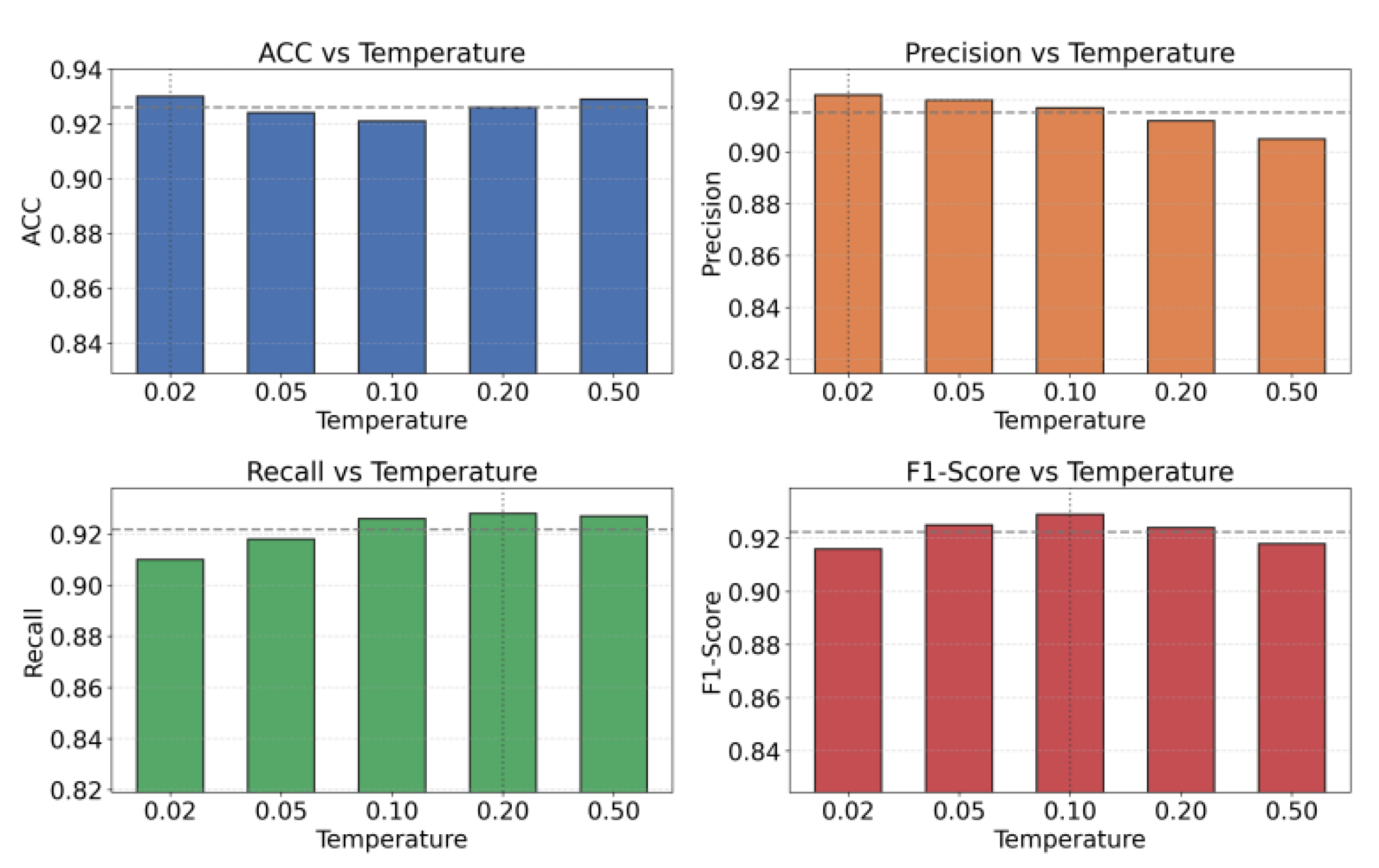

The temperature coefficient in the contrastive loss directly controls the "sharpness" of the similarity between positive and negative samples in softmax normalization, thus affecting the strength with which contrastive learning brings positive samples closer and pushes negative samples further apart in the representation space. In cross-service anomaly detection scenarios, if the temperature coefficient is too small, the model may overemphasize a few extreme negative samples, resulting in an overly tight representation space and difficulty in maintaining structural diversity between different services; if the temperature coefficient is too large, the differences between positive and negative samples are over-smoothed, weakening the ability to distinguish anomaly propagation patterns. Therefore, it is necessary to systematically examine the sensitivity of a single model on multiple metrics around different temperature coefficients to characterize the balance between "contrast strength" and cross-service representation quality. The experimental results are shown in

Figure 4.

Across different temperature settings, the results indicate that neither a lower temperature nor a higher temperature is universally better. The key is to balance contrastive force and structural separability. When the temperature is too low, the model overemphasizes differences among samples. The cross-service temporal representation space becomes overly compact. Local service fluctuations can be amplified into anomalous features. This harms overall representation stability. In contrast, an excessively high temperature weakens sample discrimination. The model then fails to capture structural characteristics of cross-service anomaly propagation. This reduces anomaly recognition capability.

Among the metrics, the trends of F1 and Recall suggest that a middle temperature range provides a better balance. This implies that a moderate temperature helps construct a more structural service representation space. Such a space can capture key propagation paths in cross-service correlation modeling. It also preserves robust sensitivity to anomalies along service call chains. In other words, the temperature coefficient influences more than the loss scale in this framework. It implicitly shapes the geometry of the cross-service representation space.

Precision and ACC remain relatively stable, but they still decline under extreme temperatures. This indicates that temperature changes affect how the model delineates boundaries between anomalous patterns and normal collaborative behaviors. Cross-service anomalies often involve multi-scale propagation and link-level resonance. Temperature adjustment, therefore, controls the strength of aggregation and separation in the contrastive space. An appropriate temperature promotes reasonable alignment of cross-service temporal information. It helps the model maintain high anomaly sensitivity at the structural modeling level. It also avoids incorrect decisions caused by excessive alignment or excessive dispersion.