Submitted:

29 December 2025

Posted:

30 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Profile publicly documented PVS activities, or lack thereof, in countries previously endemic for LF.

- Examine documented barriers and facilitators to the implementation of PVS strategies, and how these vary by context.

- Compare alignment of PVS activities with recently released recommendations in the WHO’s Monitoring and epidemiological assessment of mass drug administration in the global programme to eliminate lymphatic filariasis guidelines [13].

- Identify knowledge gaps in PVS implementation methods that may be addressed through further operational research.

2. Materials and Methods

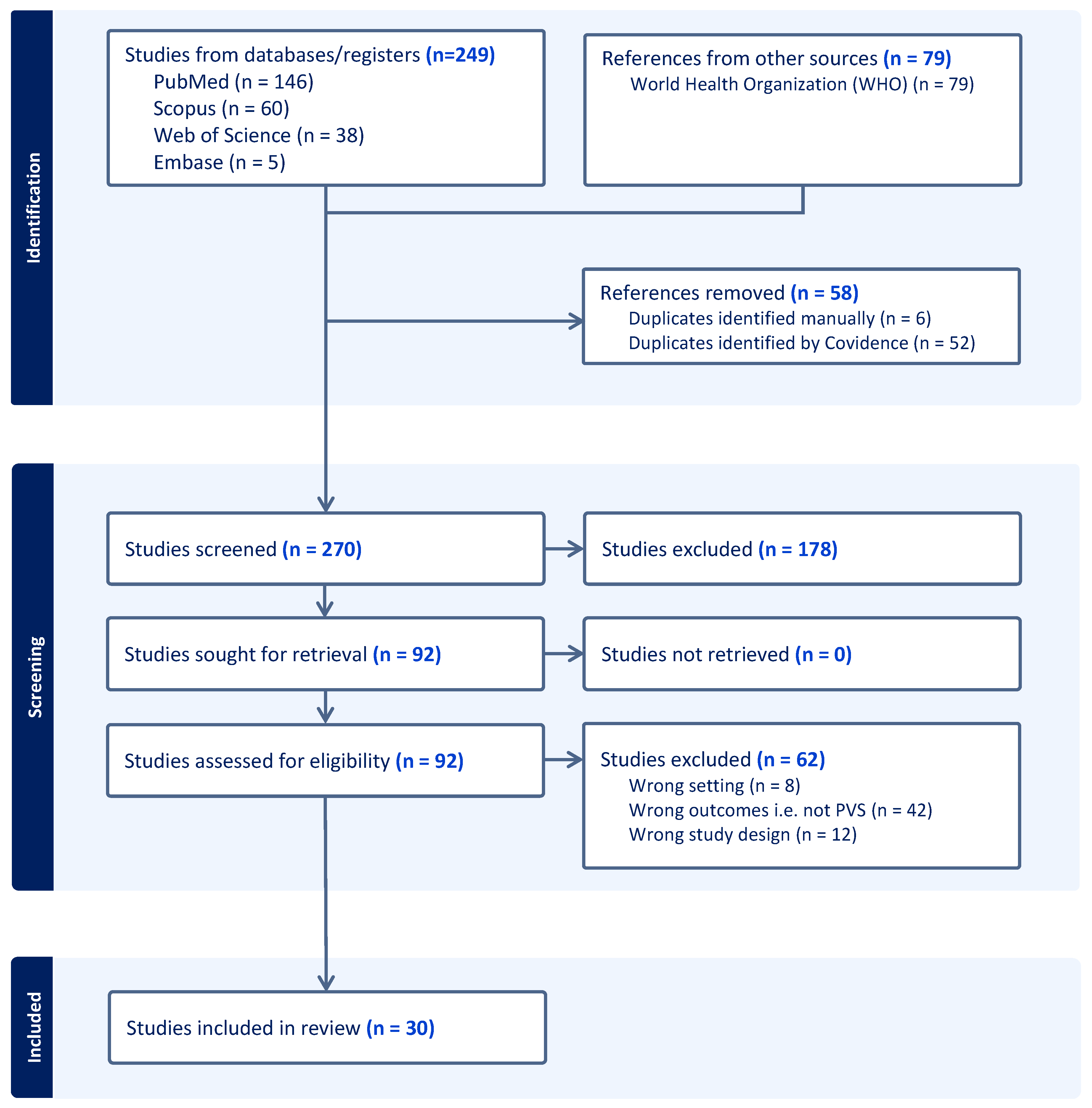

2.1. Identifying Studies

| PICOT | Component | Search Term | Add with |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Countries that have been validated as having eliminated LF by WHO | "Bangladesh"[Mesh] OR Bangladesh* OR "Cambodia"[Mesh] OR Cambodia* OR China [MeSH] OR Cook Island* OR "Egypt"[Mesh] OR Egypt* OR Kiribati* OR “i-Kiribati” OR "Laos"[Mesh] OR Laos OR "Malawi"[Mesh] OR Malawi* OR Maldiv* OR Marshall Island* OR Niue* OR Palau* OR “Republic of Korea”[Mesh] OR “South Korea” OR "Sri Lanka"[Mesh] OR Sri Lanka* OR "Thailand"[Mesh] OR Thai* OR "Togo"[Mesh] OR Togo* OR Tonga* OR Vanuatu* OR "Vietnam"[Mesh] OR Vietnam* OR "Yemen"[Mesh] OR Yemen* OR “Wallis and Futuna” OR Wallis* OR Futuna* OR "Brazil"[Mesh] OR Brazil* OR “Timor-Leste”[Mesh] OR Timor* | AND |

| Exposure or intervention | Lymphatic filariasis | "Elephantiasis, Filarial"[Mesh] OR "lymphatic filariasis" OR elephantias* OR filaria* OR “filarial elephantiasis” OR filarial lympho*dema OR "Wuchereria bancrofti" OR "Brugia malayi" OR "Brugia timori" OR Bancrofti* OR Brugia* | AND |

| Outcome | Post-validation surveillance | "post-elimination" OR "post-validation" OR elimination OR validation OR "Sentinel Surveillance"[Mesh] OR “sentinel surveillance” OR “Public Health Surveillance” [Mesh] OR “public health surveillance” OR "Population Surveillance"[Mesh] OR “population surveillance” OR "Monitoring, Physiologic"[Mesh] OR “physiologic monitoring” OR "Epidemiological Monitoring"[Mesh] OR "Mass Screening"[Mesh] OR “mass screening” | AND |

| Comparator | N/A | N/A | |

| Time | Jan 2007– Jun 2025 (inclusive) | Jan 2007– Jun 2025 (inclusive) | AND |

2.2. Data Management, Study Screening and Selection

- • described PVS activities conducted between January 1, 2007, to July 30, 2025 (inclusive) in a country or territory that has been validated by WHO as having eliminated LF as a public health problem;

- • were original research, activity reports, protocols, or WHO grey literature describing population-level surveillance; and

- • were published between January 1, 2007, and July 30, 2025 (inclusive).

- • described surveillance activities that occurred before validation by WHO of elimination of LF; or

- • did not describe population-level surveillance activities (such as diagnostic validation and modelling studies, letters, editorials and commentary articles).

2.3. Data Extraction

- Publication information: year of publication, country of study setting, publication funding sources

- LF epidemiology: causative pathogen (W. bancrofti or Brugia spp.), year in which LF was validated as eliminated, targeted high-risk or priority populations (e.g. historic hot spots)

- PVS activities: years in which PVS activities were conducted, type of surveillance activities conducted, frequency of activities, sampling design (targeted or population-representative), surveillance type (active, passive, sentinel), type of testing (antigen, antibody, microfilaria, MX/PCR of mosquito samples), other activities (including risk reduction and vector management)

- Operational challenges or enablers: PVS activity funding sources; staffing and resources; technical capacity; and social, political, or economic drivers of PVS program implementation

2.4. Analysis

Ethical Considerations and Funding

3. Results

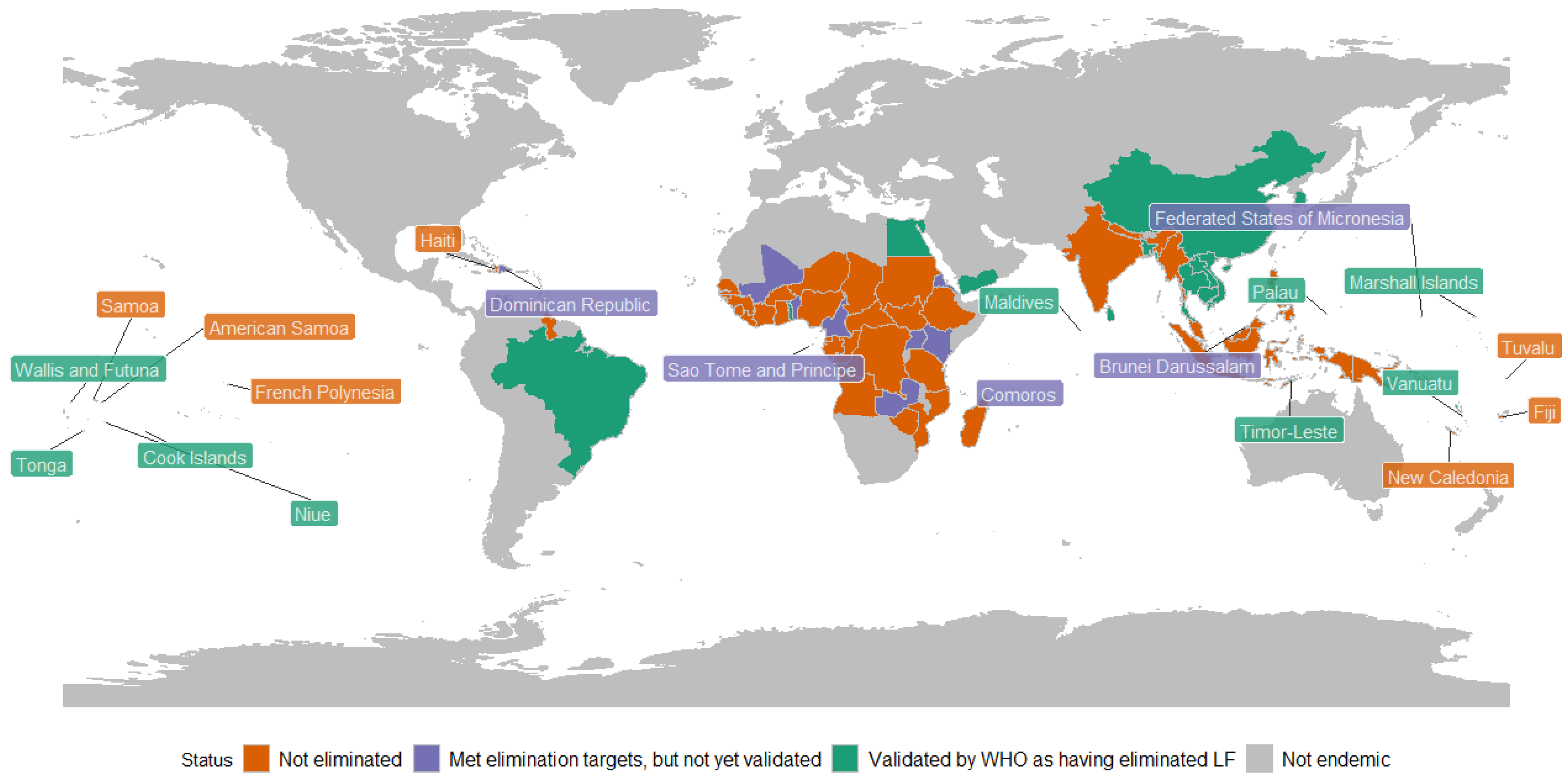

3.1. Lymphatic Filariasis Elimination

3.2. Post-Validation Surveillance Activities

WHO-Recommended PVS Strategies

Other Surveillance Strategies

3.3. Diagnostic Testing Methods

3.4. Frequency of PVS

3.5. Health System Constraints and Enablers

| WHO region | Country | Constraints | Enablers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financing | Health workforce & technical capacity | Accessing PVS diagnostic tools and supplies | Policies and guidelines | Policies and guidelines | Health workforce & technical capacity | Infrastructure development | Data development | Health education | ||

| AFRO | Malawi | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Togo | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| SEAR | Bangladesh | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Maldives | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Sri Lanka | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |||

| Thailand | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| WPRO | Cambodia | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| China | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| South Korea | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Tonga | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Vanuatu | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| No. documents describing theme | 10 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 2 | |

| No. countries in which theme occurred | 8 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 2 | |

| Country | Year LF eliminated | WHO region | Type of LF | Reference | Year published | Activities | Priority populations* | Years conducted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | 2007 | WPR | W. bancrofti, B. malayi | Sun et al. [32] | 2020 | Targeted surveys | Historic hotspots | 2008 |

| W. bancrofti, B. malayi | Huang et al. [33] | 2020 | Targeted surveys, MX; MMDP | Historic hotspots | 1982–1992^ | |||

| W. bancrofti, B. malayi | Qian et al. [31] | 2019 | Health-facility based passive surveillance | Population-wide | 1980 onwards^ | |||

| W. bancrofti, B. malayi | WHO [30] | 2018 | Targeted surveys; passive surveillance | Migrants from endemic countries | 2007 onwards | |||

| W. bancrofti, B. malayi | Yang et al. [29] | 2014 | Targeted surveys, MMDP (incl. the establishment of new facilities) | Migrants from endemic countries | 2007 onwards | |||

| W. bancrofti, B. malayi | Sudomo et al. [28] | 2010 | MMDP | Migrants from endemic countries | 2007 onwards | |||

| W. bancrofti, B. malayi | WHO [27] | 2009 | Targeted surveys; MX; MMDP | Areas known to have weak surveillance systems and/or symptomatic cases, migrants from endemic countries | 2007 onwards | |||

| South Korea | 2008 | WPR | B. malayi | Riches et al. [42] | 2020 | MX | Historic hotspots | 2011 |

| W. bancrofti, B. malayi | Bahk et al. [30] | 2018 | Sentinel surveillance | Migrants from endemic countries | Unspecified | |||

| B. malayi | WHO [30] | 2018 | Targeted surveys; MX | Historic hotspots | School surveys 2009–2011; MX 2008 onwards | |||

| W. bancrofti, B. malayi | WHO [27] | 2009 | Targeted surveys; MX | Historic hotspots | 2009 | |||

| Cambodia | 2016 | WPR | W. bancrofti | WHO [26] | 2017 | Integrated surveillance | Historic hotspots | Unspecified |

| Maldives | 2016 | SEAR | W. bancrofti | WHO [25] | 2025 | School-based surveys, targeted surveys | Migrants from endemic countries | 2016 onwards |

| W. bancrofti | WHO [34] | 2024 | Targeted surveys | Historic hotspots; migrants from endemic countries | 2016 onwards | |||

| W. bancrofti | WHO [38] | 2023 | Targeted surveys, integrated surveillance, integrated MX, MMDP | Migrants from endemic countries | 2016 onwards | |||

| W. bancrofti | WHO [37] | 2020 | Targeted surveys; integrated MX | Migrants from endemic countries | 2016 onwards | |||

| Niue | 2016 | WPR | W. bancrofti | Craig et al. [39] | 2025 | Integration into STEPs | Migrants from endemic countries | 2024 |

| Sri Lanka | 2016 | SEAR | W. bancrofti, B. malayi | WHO [25] | 2025 | Targeted surveys, MX | Unspecified | 2017 onwards |

| W. bancrofti, B. malayi | WHO [34] | 2024 | Targeted surveys | Historic hotspots; migrants from endemic countries | Unspecified | |||

| W. bancrofti, B. malayi | Gunaratna et al. [46] | 2024 | MMDP | Unspecified | 2016 onwards | |||

| W. bancrofti, B. malayi | WHO [38] | 2023 | Targeted surveys, MX | Migrants from endemic countries | 2016 onwards | |||

| W. bancrofti, B. malayi | Mallawarachchi et al. [45] | 2021 | Targeted surveys, MX, cat and dog serosurveys | Historic hotspots | After 2018 (years unspecified) | |||

| B. malayi | WHO [37] | 2020 | Targeted surveys, integrated MX, MMDP | Migrants from endemic countries | Unspecified | |||

| W. bancrofti, B. malayi | Rahman et al. [19] | 2019 | Targeted surveys | Historic hotspots | 2018 | |||

| B. malayi | Mallawarachchi et al. [44] | 2018 | Targeted surveys; dog serosurveys | Historic hotspots | 2016–2017 | |||

| W. bancrofti, B. malayi | WHO [26] | 2017 | Targeted surveys | Historic hotspots | 2017 onwards | |||

| W. bancrofti | Rao et al. [43] | 2017 | Targeted surveys; MX | Historic hotspots | 2015–2017 | |||

| Vanuatu | 2016 | WPR | W. bancrofti | WHO [26] | 2017 | Integrated surveillance | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Thailand | 2017 | WPR | W. bancrofti, B. malayi | WHO [25] | 2025 | Targeted surveys, cat serosurveys, integration with NCD screening | Migrants from endemic countries | 2017 onwards |

| W. bancrofti, B. malayi | WHO [34] | 2024 | Targeted surveys | Historic hotspots; migrants from endemic countries | 2017 onwards | |||

| W. bancrofti, B. malayi | Meetham et al. [48] | 2023 | Targeted surveys, cat serosurveys | Historic hotspots; migrants from endemic countries | 2017 onwards | |||

| W. bancrofti, B. malayi | WHO [38] | 2023 | Targeted surveys, MX, cat serosurveys | Migrants from endemic countries | 2017 onwards | |||

| W. bancrofti, B. malayi | Bizhani et al. [47] | 2021 | Targeted surveys | Migrants from endemic countries | 2017 onwards | |||

| B. malayi | WHO [37] | 2020 | Targeted surveys, MX | Historic hotspots, migrants from endemic countries | 2017 onwards | |||

| Togo | 2017 | AFR | W. bancrofti | Dorkenoo et al. [50] | 2021 | Targeted surveys, MX, MMDP, cat serosurveys | Migrants from endemic countries | 2018 |

| W. bancrofti | Dorkenoo et al. [49] | 2018 | MX | Historic hotspots | 2016–2017 | |||

| Tonga | 2017 | WPR | W. bancrofti | Lawford et al. [51] | 2025 | Targeted surveys, health-facility based screening | Historic hotspots | 2024 |

| Egypt | 2018 | EMR | W. bancrofti | WHO [34] | 2024 | Unspecified PVS, MMDP | Unspecified | After 2018 (years unknown) |

| Palau | 2018 | WPR | W. bancrofti | WHO [40] | 2020 | Targeted surveys | Migrants from endemic countries | 2017 onwards |

| Wallis and Futuna | 2015 | WPR | W. bancrofti | Couteaux et al. [52] | 2025 | Targeted surveys; health-facility based screening | Areas with greater prevalence of hypereosinophilia | 2024 |

| Kiribati | 2019 | WPR | W. bancrofti | WHO [35] | 2023 | Integrated surveillance | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Yemen | 2019 | EMR | W. bancrofti | WHO [34] | 2024 | Unspecified PVS, MMDP | Unspecified | After 2019 (years unknown) |

| W. bancrofti | WHO [53] | 2022 | Integrated surveillance and MX, MMDP | Unspecified | Unknown | |||

| Malawi | 2020 | AFR | W. bancrofti | Barrett et al. [36] | 2024 | MMDP | Unspecified | 2020 onwards |

| Bangladesh | 2023 | SEAR | W. bancrofti | WHO [25] | 2025 | Targeted surveys, health-facility based screening | Historic hotspots; areas of low socioeconomic status | 2023 onwards |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFR | WHO African Region |

| AMR | WHO Region of the Americas |

| DALY | disability-adjusted life-years |

| ELISA | enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| EMR | WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region |

| FTS | Filarial test strip |

| GBD | Global Burden of Disease |

| GPELF | Global Program for the Elimination of Lymphatic Filariasis |

| HERA | The University of Queensland's Health Research Accelerator initiative |

| IRIS | WHO Institutional Repository for Information Sharing |

| Lao PDR | Lao People’s Democratic Republic |

| LF | Lymphatic filariasis |

| MDA | Mass drug administration |

| MMDP | Morbidity management and disability prevention |

| MX | Molecular xenomonitoring |

| NCD | Non-communicable disease |

| NTD | Neglected tropical disease |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| PICOT | The Population, Intervention/Exposure, Comparator, Outcome and Time framework |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines |

| PVS | Post-validation surveillance |

| RDT | Rapid diagnostic test |

| RMI | Republic of the Marshall Islands |

| SEAR | WHO South-East Asian Region |

| STEPs | WHO STEPwise approach to non-communicable disease risk factor survey |

| TAS | Transmission assessment survey |

| USD | United States dollars |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| WPR | WHO Western Pacific Region |

Appendix A: Search Terms by Database

| Database | Search terms |

| PubMed | ("Bangladesh"[Mesh] OR Bangladesh* OR "Cambodia"[Mesh] OR Cambodia* OR Cook Island* OR "Egypt"[Mesh] OR Egypt* OR Kiribati* OR "I-Kiribati" OR "Laos"[Mesh] OR Laos OR "Malawi"[Mesh] OR Malawi* OR Maldiv* OR Marshall Island* OR Niue* OR Palau* OR "Sri Lanka"[Mesh] OR Sri Lanka* OR "Thailand"[Mesh] OR Thai* OR "Togo"[Mesh] OR Togo* OR Tonga* OR Vanuatu* OR "Vietnam"[Mesh] OR Vietnam* OR "Yemen"[Mesh] OR Yemen* OR "Wallis and Futuna" OR Wallis* OR Futuna* OR "Brazil"[Mesh] OR Brazil* OR "Timor-Leste"[Mesh] OR Timor*) AND ("Elephantiasis, Filarial"[Mesh] OR "lymphatic filariasis" OR elephantias* OR filaria* OR "filarial elephantiasis" OR filarial lympho*dema OR "Wuchereria bancrofti" OR "Brugia malayi" OR "Brugia timori" OR Bancrofti* OR Brugia*) AND ("Sentinel Surveillance"[Mesh] OR "sentinel surveillance" OR "Public Health Surveillance"[Mesh] OR "public health surveillance" OR "Population Surveillance"[Mesh] OR "population surveillance" OR "Monitoring, Physiologic"[Mesh] OR "physiologic monitoring" OR "Epidemiological Monitoring"[Mesh] OR "epidemiological monitoring" OR "Mass Screening"[Mesh] OR "mass screening") AND ("post-elimination" OR "post-validation" OR elimination OR validation) AND (PUBYEAR > 2006 AND PUBYEAR < 2026) |

| Scopus | (Bangladesh* OR Cambodia* OR Cook Island* OR Egypt* OR Kiribati* OR “I-Kiribati” OR Lao* OR Malawi* OR Maldiv* OR Marshall Island* OR Niue* OR Palau* OR Sri Lanka* OR Thai* OR Togo* OR Tonga* OR Vanuatu* OR Vietnam* OR Yemen* OR Wallis* OR Futuna* OR Brazil* OR Timor*) AND ("lymphatic filariasis" OR "elephantiasis" OR "filarial elephantiasis" OR "Wuchereria bancrofti" OR "Brugia malayi" OR "Brugia timori" OR "filarial infection”) AND ("sentinel surveillance" OR "public health surveillance" OR "population surveillance" OR "physiologic monitoring" OR "epidemiological monitoring" OR "mass screening") AND ("post-elimination" OR "post-validation" OR elimination OR validation) AND (PUBYEAR > 2006 AND PUBYEAR < 2026) |

| Embase | (Bangladesh* OR Cambodia* OR Cook Island* OR Egypt* OR Kiribati* OR “I-Kiribati” OR Lao* OR Malawi* OR Maldiv* OR Marshall Island* OR Niue* OR Palau* OR Sri Lanka* OR Thai* OR Togo* OR Tonga* OR Vanuatu* OR Vietnam* OR Yemen* OR Wallis* OR Futuna* OR Brazil* OR Timor*) AND ("lymphatic filariasis" OR "elephantiasis" OR "filarial elephantiasis" OR "Wuchereria bancrofti" OR "Brugia malayi" OR "Brugia timori" OR "filarial infection”) AND ("sentinel surveillance" OR "public health surveillance" OR "population surveillance" OR "physiologic monitoring" OR "epidemiological monitoring" OR "mass screening") AND ("post-elimination" OR "post-validation" OR elimination OR validation) AND [2007-2025]/py |

| Web of Science | (Bangladesh* OR Cambodia* OR Cook Island* OR Egypt* OR Kiribati* OR “I-Kiribati” OR Lao* OR Malawi* OR Maldiv* OR Marshall Island* OR Niue* OR Palau* OR Sri Lanka* OR Thai* OR Togo* OR Tonga* OR Vanuatu* OR Vietnam* OR Yemen* OR Wallis* OR Futuna* OR Brazil* OR Timor*) AND ("lymphatic filariasis" OR "elephantiasis" OR "filarial elephantiasis" OR "Wuchereria bancrofti" OR "Brugia malayi" OR "Brugia timori" OR "filarial infection”) AND ("sentinel surveillance" OR "public health surveillance" OR "population surveillance" OR "physiologic monitoring" OR "epidemiological monitoring" OR "mass screening") AND ("post-elimination" OR "post-validation" OR elimination OR validation) AND [2007-2025]/py |

| WHO IRIS | (Bangladesh* OR Cambodia* OR Cook Island* OR Egypt* OR Kiribati* OR “I-Kiribati” OR Lao* OR Malawi* OR Maldiv* OR Marshall Island* OR Niue* OR Palau* OR Sri Lanka* OR Thai* OR Togo* OR Tonga* OR Vanuatu* OR Vietnam* OR Yemen* OR Wallis* OR Futuna* OR Brazil* OR Timor*) AND ("lymphatic filariasis" OR "elephantiasis" OR "filarial elephantiasis" OR "Wuchereria bancrofti" OR "Brugia malayi" OR "Brugia timori" OR "filarial infection”) AND ("sentinel surveillance" OR "public health surveillance" OR "population surveillance" OR "physiologic monitoring" OR "epidemiological monitoring" OR "mass screening") AND ("post-elimination" OR "post-validation") [1] AND Date issued: [2007 TO 2025] |

| 1 The terms ‘validation’ and ‘post-validation’ refer to distinct stages of the elimination process in WHO publications; the terms ‘elimination’ and ‘validation’ were removed when searching this database to maintain specificity. | |

References

- Ichimori, K.; Graves, P.M. Overview of PacELF-the Pacific Programme for the Elimination of Lymphatic Filariasis. Trop Med Health 2017, 45, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lymphatic Filariasis. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/lymphaticfilariasis/modules/W_bancrofti_LifeCycle_lg.jpg (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- World Health Organization. Lymphatic filariasis (Elephantiasis). Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/lymphatic-filariasis (accessed on 3/12/2024).

- World Health Organization; Regional Office for South-East. FAQs: Frequently asked questions on Lymphatic Filariasis (elephantiasis); WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia: New Delhi, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstraat, K.; van Brakel, W.H. Social stigma towards neglected tropical diseases: a systematic review. Int Health 2016, 8, i53–i70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, C.G.; Bettis, A.A.; Chu, B.K.; English, M.; Ottesen, E.A.; Bradley, M.H.; Turner, H.C. The Health and Economic Burdens of Lymphatic Filariasis Prior to Mass Drug Administration Programs. Clin Infect Dis 2020, 70, 2561–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottesen, E.A.; Hooper, P.J.; Bradley, M.; Biswas, G. The Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis: Health Impact after 8 Years. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2008, 2, e317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/control-of-neglected-tropical-diseases/lymphatic-filariasis/global-programme-to-eliminate-lymphatic-filariasis (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Kapa, D.R.; Mohamed, A.J. Progress and impact of 20 years of a lymphatic filariasis elimination programme in South-East Asia. International Health 2021, 13, S17–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deribe, K.; Bakajika, D.K.; Zoure, H.M.G.; Gyapong, J.O.; Molyneux, D.H.; Rebollo, M.P. African regional progress and status of the programme to eliminate lymphatic filariasis: 2000-2020. International Health 2021, 13, S22–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collyer, B.S.; Irvine, M.A.; Hollingsworth, T.D.; Bradley, M.; Anderson, R.M. Defining a prevalence level to describe the elimination of Lymphatic Filariasis (LF) transmission and designing monitoring & evaluating (M&E) programmes post the cessation of mass drug administration (MDA). PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2020, 14, e0008644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Monitoring and epidemiological assessment of mass drug administration in the global programme to eliminate lymphatic filariasis: a manual for national elimination programmes, 2nd ed; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- World Health; O. Ending the neglect to attain the sustainable development goals: a framework for monitoring and evaluating progress of the road map for neglected tropical diseases 2021−2030; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Validation of elimination of lymphatic filariasis as a public health problem; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. Ending the neglect to attain the Sustainable Development Goals: A road map for neglected tropical diseases 2021–2030; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. Global programme to eliminate lymphatic filariasis: Progress report on mass drug administration in 2007; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, A.; Sanikullah, K. Post-validation surveillance for lymphatic filariasis. COR-NTD Meeting for the Pacific Islands 2024 Breakout Reports 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.A.; Yahathugoda, T.C.; Tojo, B.; Premaratne, P.; Nagaoka, F.; Takagi, H.; Kannathasan, S.; Murugananthan, A.; Weerasooriya, M.V.; Itoh, M. A surveillance system for lymphatic filariasis after its elimination in Sri Lanka. PARASITOLOGY INTERNATIONAL 2019, 68, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawford, H.; Tukia, O.; Takai, J.; Sheridan, S.L.; Ward, S.; Jian, H.; Martin Mario, B.; 'Ofanoa, R.; Lau, C. Localised Transmission of Lymphatic Filariasis in Tonga Seven Years after Validation of Elimination as a Public Health Problem. Preprints with The Lancet 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Lymphatic Filariasis Status of Mass Drug Administration: 2025. Available online: https://apps.who.int/neglected_diseases/ntddata/lf/lf.html (accessed on 20/11/2025).

- Lawford, H.; Jian, H.; Tukia, O.; Takai, J.; Couteaux, C.; Thein, C.; Jetton, K.; Tabunga, T.; Bauro, T.; Nehemia, R.; et al. Barriers and Facilitators to Implementing Post-Validation Surveillance of Lymphatic Filariasis in Pacific Island Countries and Territories: A Conceptual Framework Developed from Qualitative Data. SSRN 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, S.; Kyngas, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Meeting of the National Programme Managers and Regional Technical Advisory Group for Lymphatic Filariasis Elimination Kathmandu, Nepal. 25-27 June 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/SEA-NCD-111 (accessed on 21/07/2025).

- World Health Organization; Regional Office for the Western Pacific. Informal Consultation on Post-elimination Surveillance of Neglected Tropical Diseases, Siem Reap, Cambodia, 13-14 June 2017: meeting report; WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific: Manila, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Western Pacific. First Mekong-Plus Programme Managers Workshop on Lymphatic Filariasis and Other Helminthiasis; WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific: Phnom Penh, Cambodia; Manila, 23-26 March 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sudomo, M.; Chayabejara, S.; Duong, S.; Hernandez, L.; Wu, W.-P.; Bergquist, R. Chapter 8 - Elimination of Lymphatic Filariasis in Southeast Asia. In Advances in Parasitology; Zhou, X.-N., Bergquist, R., Olveda, R., Utzinger, J., Eds.; Academic Press, 2010; Volume 72, pp. 205–233. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G.J.; Liu, L.; Zhu, H.R.; Griffiths, S.M.; Tanner, M.; Bergquist, R.; Utzinger, J.; Zhou, X.N. China's sustained drive to eliminate neglected tropical diseases. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2014, 14, 881–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Western Pacific. Programme Managers Meeting on Neglected Tropical Diseases in the Asia Subregion, Manila, Philippines, 13-14 March 2019 : meeting report. Manila, 2018.

- Qian, M.B.; Chen, J.; Bergquist, R.; Li, Z.J.; Li, S.Z.; Xiao, N.; Utzinger, J.; Zhou, X.N. Neglected tropical diseases in the People's Republic of China: Progress towards elimination. Infectious Diseases of Poverty 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, D.J.; Fang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Contributions to the lymphatic filariasis elimination programme and post-elimination surveillance in China by NIPD-CTDR. Adv Parasitol 2020, 110, 145–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Deng, X.; Kou, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Cheng, P.; Gong, M. Elimination of Lymphatic Filariasis in Shandong Province, China, 1957-2015. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases 2020, 20, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization = Organisation mondiale de la; S. Global programme to eliminate lymphatic filariasis: progress report, 2023 = Programme mondial pour l’élimination de la filariose lymphatique: rapport de situation, 2023. Weekly Epidemiological Record = Relevé épidémiologique hebdomadaire 2024, 99, 565–576. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global report on neglected tropical diseases 2023; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, C.; Chiphwanya, J.; Matipula, D.E.; Douglass, J.; Kelly-Hope, L.A.; Dean, L. Addressing the Syndemic Relationship between Lymphatic Filariasis and Mental Distress in Malawi: The Potential of Enhanced Self-Care. Trop Med Infect Dis 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization; Regional Office for South-East. Report on the virtual meeting of the regional programme review group (RPRG) for lymphatic filariasis, soil-transmitted helminthiasis and schistosomiasis in the WHO South-East Asia Region; World Health Organization. Regional Office for South-East Asia: New Delhi, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Health, Organization. Regional Office for South-East, A. Meeting of National Programme Managers for lymphatic filariasis, soil-transmitted helminthiasis and schistosomiasis and the Regional Programme Review Group of the WHO South-East Asia Region. New Delhi, 2023.

- Craig, A.T.; Lawford, H.; Mokoia, G.; Ikimau, M.; Fetaui, P.; Marqardt, T.; Lau, C.L. Integrating post-validation surveillance of lymphatic filariasis with the WHO STEPwise approach to non-communicable disease risk factor surveillance in Niue, a study protocol. PLoS One 2025, 20, e0315625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Programme Managers Meeting on Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTD) in the Pacific, Nadi, Fiji, 20-22 February 2018 : meeting report. 2020.

- Bahk, Y.Y.; Shin, E.H.; Cho, S.H.; Ju, J.W.; Chai, J.Y.; Kim, T.S. Prevention and control strategies for parasitic infections in the Korea centers for disease control and prevention. Korean Journal of Parasitology 2018, 56, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riches, N.; Badia-Rius, X.; Mzilahowa, T.; Kelly-Hope, L.A. A systematic review of alternative surveillance approaches for lymphatic filariasis in low prevalence settings: Implications for post-validation settings. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2020, 14, e0008289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.U.; Samarasekera, S.D.; Nagodavithana, K.C.; Dassanayaka, T.D.M.; Punchihewa, M.W.; Ranasinghe, U.S.B.; Weil, G.J. Reassessment of areas with persistent Lymphatic Filariasis nine years after cessation of mass drug administration in Sri Lanka. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2017, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallawarachchi, C.H.; Nilmini Chandrasena, T.G.A.; Premaratna, R.; Mallawarachchi, S.; de Silva, N.R. Human infection with sub-periodic Brugia spp. in Gampaha District, Sri Lanka: a threat to filariasis elimination status? Parasit Vectors 2018, 11, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallawarachchi, C.H.; Chandrasena, T.; Withanage, G.P.; Premarathna, R.; Mallawarachchi, S.; Gunawardane, N.Y.; Dasanayake, R.S.; Gunarathna, D.; de Silva, N.R. Molecular Characterization of a Reemergent Brugia malayi Parasite in Sri Lanka, Suggestive of a Novel Strain. Biomed Res Int 2021, 2021, 9926101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunaratna, I.E.; Chandrasena, N.; Vallipuranathan, M.; Premaratna, R.; Ediriweera, D.; de Silva, N.R. The impact of the National Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis on filariasis morbidity in Sri Lanka: Comparison of current status with retrospective data following the elimination of lymphatic filariasis as a public health problem. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2024, 18, e0012343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizhani, N.; Hashemi Hafshejani, S.; Mohammadi, N.; Rezaei, M.; Rokni, M.B. Lymphatic filariasis in Asia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Parasitol Res 2021, 120, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meetham, P.; Kumlert, R.; Gopinath, D.; Yongchaitrakul, S.; Tootong, T.; Rojanapanus, S.; Padungtod, C. Five years of post-validation surveillance of lymphatic filariasis in Thailand. INFECTIOUS DISEASES OF POVERTY 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorkenoo, M.A.; de Souza, D.K.; Apetogbo, Y.; Oboussoumi, K.; Yehadji, D.; Tchalim, M.; Etassoli, S.; Koudou, B.; Ketoh, G.K.; Sodahlon, Y.; et al. Molecular xenomonitoring for post-validation surveillance of lymphatic filariasis in Togo: no evidence for active transmission. Parasit Vectors 2018, 11, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorkenoo, M.A.; Tchankoni, M.K.; Yehadji, D.; Yakpa, K.; Tchalim, M.; Sossou, E.; Bronzan, R.; Ekouevi, D.K. Monitoring migrant groups as a post-validation surveillance approach to contain the potential reemergence of lymphatic filariasis in Togo. Parasit Vectors 2021, 14, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawford, H.L.S.; Tukia, O.; Takai, J.; Sheridan, S.; Ward, S.; Jian, H.; Martin, B.M.; Ofanoa, R.; Lau, C.L. Persistent lymphatic filariasis transmission seven years after validation of elimination as a public health problem: a cross-sectional study in Tonga. The Lancet Regional Health - Western Pacific 2025, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couteaux, C.; Demaneuf, T.; Bien, L.; Munoz, M.; Worms, B.; Chesimar, S.; Takala, G.; Lie, A.; Jessop, V.; Selemago, M.K.; et al. Postelimination Cluster of Lymphatic Filariasis, Futuna, 2024. Emerg Infect Dis 2025, 31, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Eastern, M. Summary report on the twentieth meeting of the Regional Programme Review Group and national neglected tropical diseases programme managers, virtual meeting; WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean: Cairo, Egypt, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. PCT Databank - Lymphatic filariasis. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/control-of-neglected-tropical-diseases/data-platforms/pct-databank/lymphatic-filariasis (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Naing, C.; Whittaker, M.A.; Tung, W.S.; Aung, H.; Mak, J.W. Prevalence of zoonotic (brugian) filariasis in Asia: A proportional meta-analysis. Acta Trop 2024, 249, 107049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization = Organisation mondiale de la; S. Global programme to eliminate lymphatic filariasis: progress report, 2022 – Programme mondial pour l’élimination de la filariose lymphatique: rapport de situation, 2022. Weekly Epidemiological Record = Relevé épidémiologique hebdomadaire 2023, 98, 489–501. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington, H.; Asugeni, J.; Jimuru, C.; Gwalaa, J.; Ribeyro, E.; Bradbury, R.; Joseph, H.; Melrose, W.; MacLaren, D.; Speare, R. A practical strategy for responding to a case of lymphatic filariasis post-elimination in Pacific Islands. Parasit Vectors 2013, 6, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badia-Rius, X.; Adamou, S.; Taylor, M.J.; Kelly-Hope, L.A. Morbidity hotspot surveillance: A novel approach to detect lymphatic filariasis transmission in non-endemic areas of the Tillabéry region of Niger. Parasite Epidemiology and Control 2023, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, H.; Moloney, J.; Maiava, F.; McClintock, S.; Lammie, P.; Melrose, W. First evidence of spatial clustering of lymphatic filariasis in an Aedes polynesiensis endemic area. Acta Trop 2011, 120 Suppl 1, S39–S47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington, C.H.; Radday, J.; Streit, T.G.; Boyd, H.A.; Beach, M.J.; Addiss, D.G.; Lovince, R.; Lovegrove, M.C.; Lafontant, J.G.; Lammie, P.J.; et al. Spatial clustering of filarial transmission before and after a Mass Drug Administration in a setting of low infection prevalence. Filaria Journal 2004, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, C.L.; Won, K.Y.; Becker, L.; Soares Magalhaes, R.J.; Fuimaono, S.; Melrose, W.; Lammie, P.J.; Graves, P.M. Seroprevalence and Spatial Epidemiology of Lymphatic Filariasis in American Samoa after Successful Mass Drug Administration. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2014, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 6Craig, A.C., Clément; Jetton, Ken; Nehemia, Roger; Sokana, Oliver; Tong, Tanebu; Bauro, Temea; Baratio, Taulanga; Tukia, Ofa; Takai, Joseph; Viali, Satupaitea; Gama Soares, Noel; Ome-Kaius, Maria; Yohogu, Mary; Volavola, Litiana; Tatui, Patricia; Taleo, Fasihah; Saketa, Sala; Tucker, Andie; Mackenzie, Charles; Gass, Katherine; Jian, Holly; Lau, Colleen; Lawford, Harriet. Enablers of Post-Validation Surveillance for Lymphatic Filariasis in the Pacific Islands: A Nominal Group Technique and Expert Elicitation. Preprints with The Lancet, 2025.

- PATH. Landscaping report: Integrated surveillance planning toolkit for neglected tropical diseases in post–validation or verification settings; PATH: Seattle, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

| WHO region | Country | Year LF eliminated | WHO-recommended PVS activities | Other surveillance activities | Sustained surveillance^ | Alignment with 2025 WHO guidelines (≥2 strategies + sustained surveillance) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Targeted surveys |

Integration into existing standardised surveys |

Health facility-based screening | Molecular xenomonitoring | Morbidity management and disability prevention | Vector surveys | Animal reservoir surveys | |||||

| AFR | Malawi | 2020 | 1 | ||||||||

| Togo | 2017 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||||||

| AMR | Brazil* | 2024 | |||||||||

| EMR | Egypt | 2018 | 1 | ||||||||

| Yemen | 2019 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| SEAR | Bangladesh | 2023 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Maldives | 2016 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Sri Lanka | 2016 | 8 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 2 | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Thailand | 2017 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 3 | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Timor Leste* | 2024 | ||||||||||

| WPR | Cambodia | 2016 | 1 | ✓ | |||||||

| China | 2007 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Cook Islands* | 2016 | ||||||||||

| Kiribati | 2019 | 1 | |||||||||

| Lao PDR* | 2023 | ||||||||||

| RMI* | 2017 | ||||||||||

| Niue | 2016 | 1 | |||||||||

| Palau | 2018 | 1 | |||||||||

| South Korea | 2008 | 2 | 4 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Tonga | 2017 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Vanuatu | 2016 | 1 | |||||||||

| Viet Nam* | 2018 | ||||||||||

| Wallis & Futuna | 2018 | 1 | |||||||||

| No. documents describing activities | 28 | 10 | 4 | 18 | 11 | 2 | 5 | - | - | ||

| No. countries in which activities occurred | 9 | 9 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 2 | 2 | - | - | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).