1. Introduction

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) remains the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, despite advances in lipid-lowering therapies. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) is a causal driver of atherogenesis, and both genetic and pharmacological studies consistently demonstrate a log-linear relationship between cumulative LDL-C exposure and cardiovascular risk [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Consequently, sustained LDL-C reduction is central to secondary prevention in patients with coronary artery disease.

Hepatic cholesterol homeostasis is tightly regulated through synthesis, intestinal absorption, and LDL receptor (LDLR)–mediated clearance. Statins inhibit HMG-CoA reductase, ezetimibe blocks cholesterol uptake via NPC1L1, and PCSK9 inhibitors enhance LDLR recycling. Despite these interventions, many very-high-risk patients fail to reach LDL-C targets in routine practice [

5,

6,

7,

8].

The 2025 ESC/EAS guidelines recommend LDL-C <55 mg/dL with ≥50% reduction from baseline in very-high-risk CCS patients [

5]. Achieving these goals often requires sequential, mechanistically complementary strategies.

Bempedoic acid (BA) is an oral prodrug selectively activated in the liver, inhibiting ATP citrate lyase (ACLY), a key enzyme linking carbohydrate metabolism to cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis by generating cytosolic acetyl-CoA upstream of HMG-CoA reductase [

9,

10,

11]. ACLY inhibition reduces hepatic cholesterol synthesis, upregulates LDLR expression, and lowers circulating LDL-C with minimal skeletal muscle exposure. Additionally, ACLY inhibition influences metabolic pathways beyond cholesterol synthesis, including urate handling via renal organic anion transporters [

12].

Randomized trials in the CLEAR program have shown BA provides additional LDL-C reduction and reduces cardiovascular events in statin-intolerant patients [

9,

12,

13,

14,

15]. However, real-world data examining metabolic and safety profiles of BA in patients receiving intensive lipid-lowering therapy are limited [

16,

17].

This study aimed to evaluate the clinical, metabolic, and renal effects of ACLY inhibition with BA in a real-world CCS cohort not achieving LDL-C targets, with emphasis on predictors of lipid response and phenotypic variability. Circulating lipid and metabolic phenotypes were interpreted as functional readouts of hepatic ACLY inhibition.

2. Results

2.1. Study Population

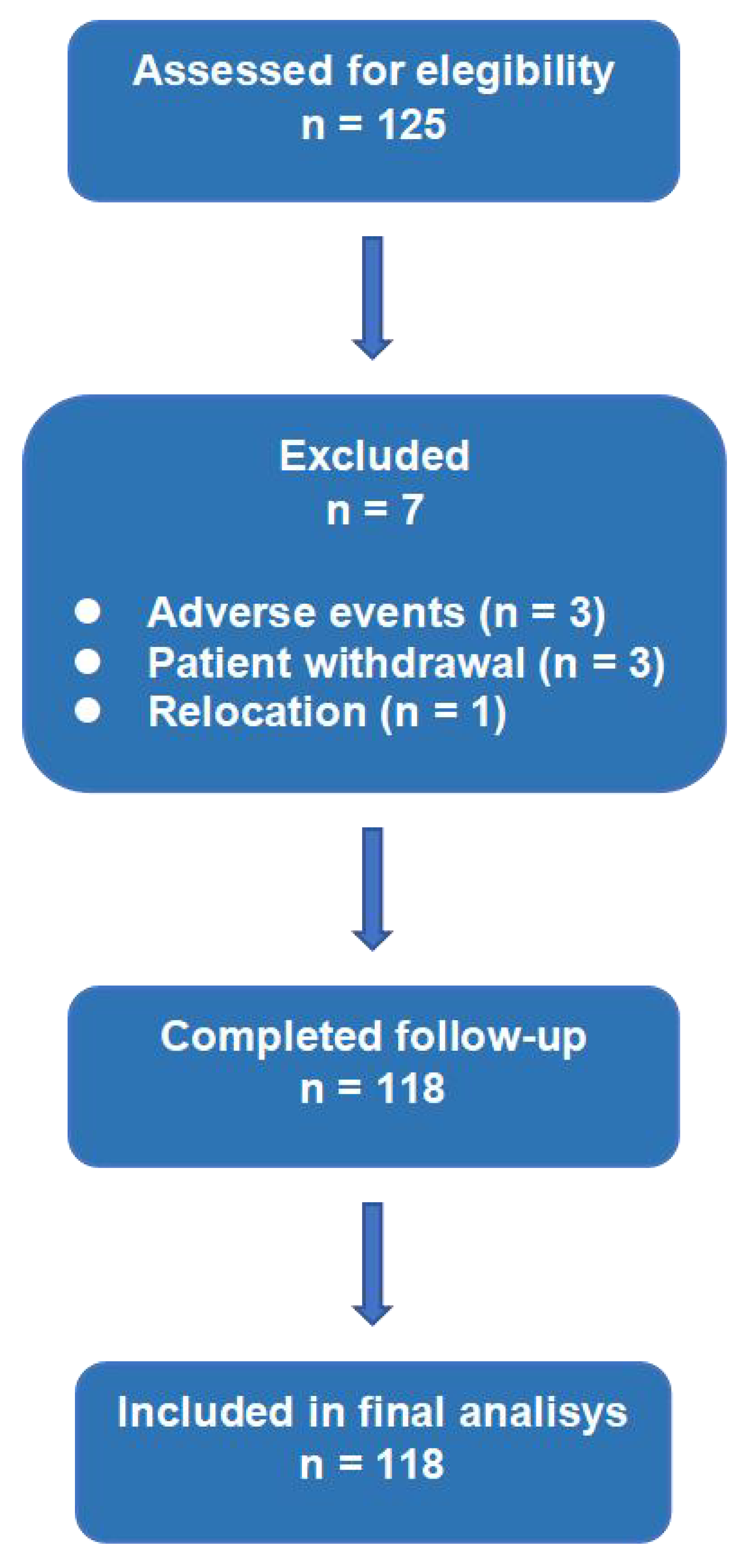

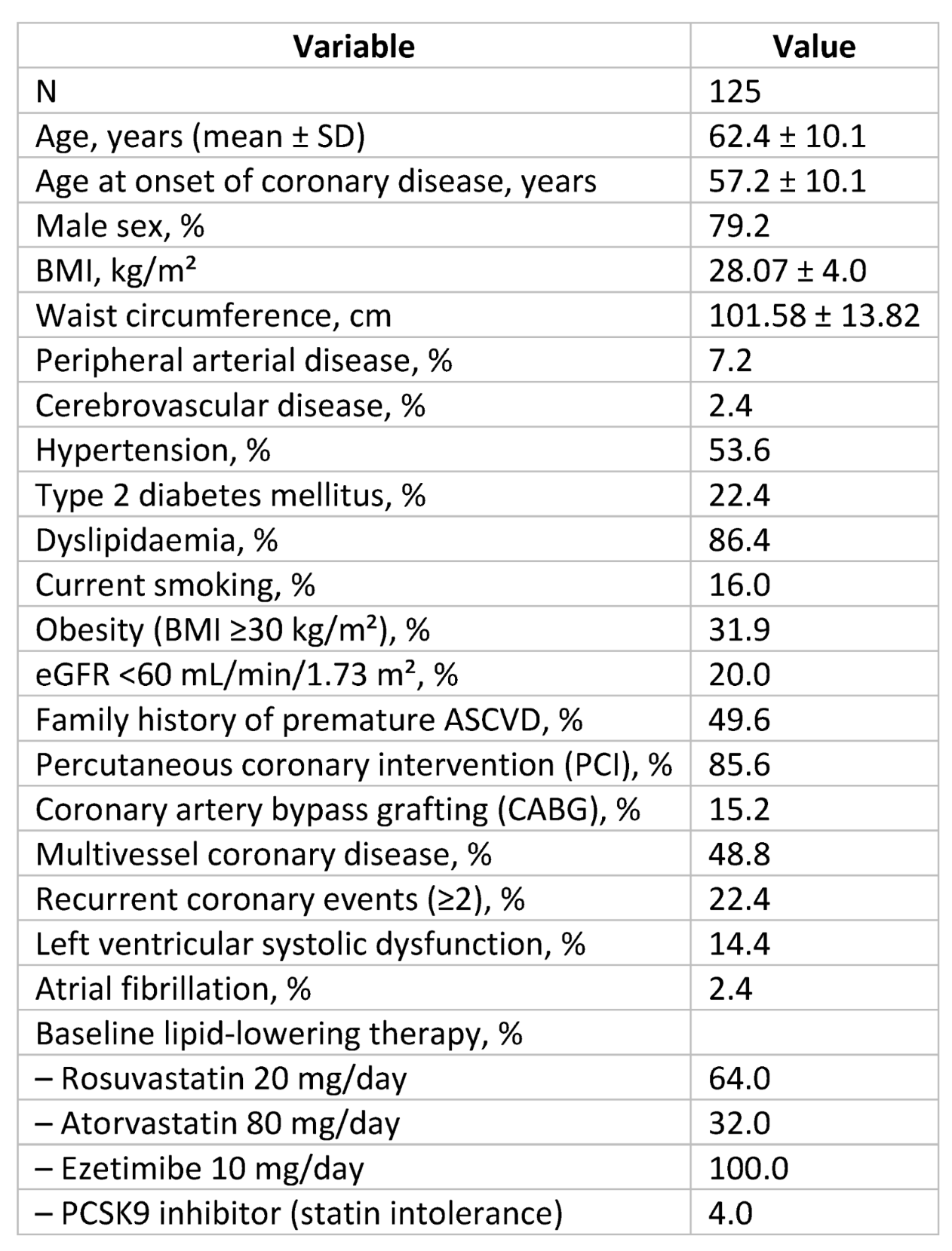

A total of 125 consecutive CCS patients were enrolled. Seven patients were excluded due to discontinuation or incomplete follow-up, leaving 118 patients for analysis (

Figure 1). Mean age was 62.4 ± 10.1 years, and 79.2% were male. Patients were on intensive therapy: high-intensity statin plus ezetimibe (n=112) or PCSK9 inhibitor plus ezetimibe (n=6). Baseline characteristics are summarized in

Table 1.

2.2. Effects on Lipid Profile

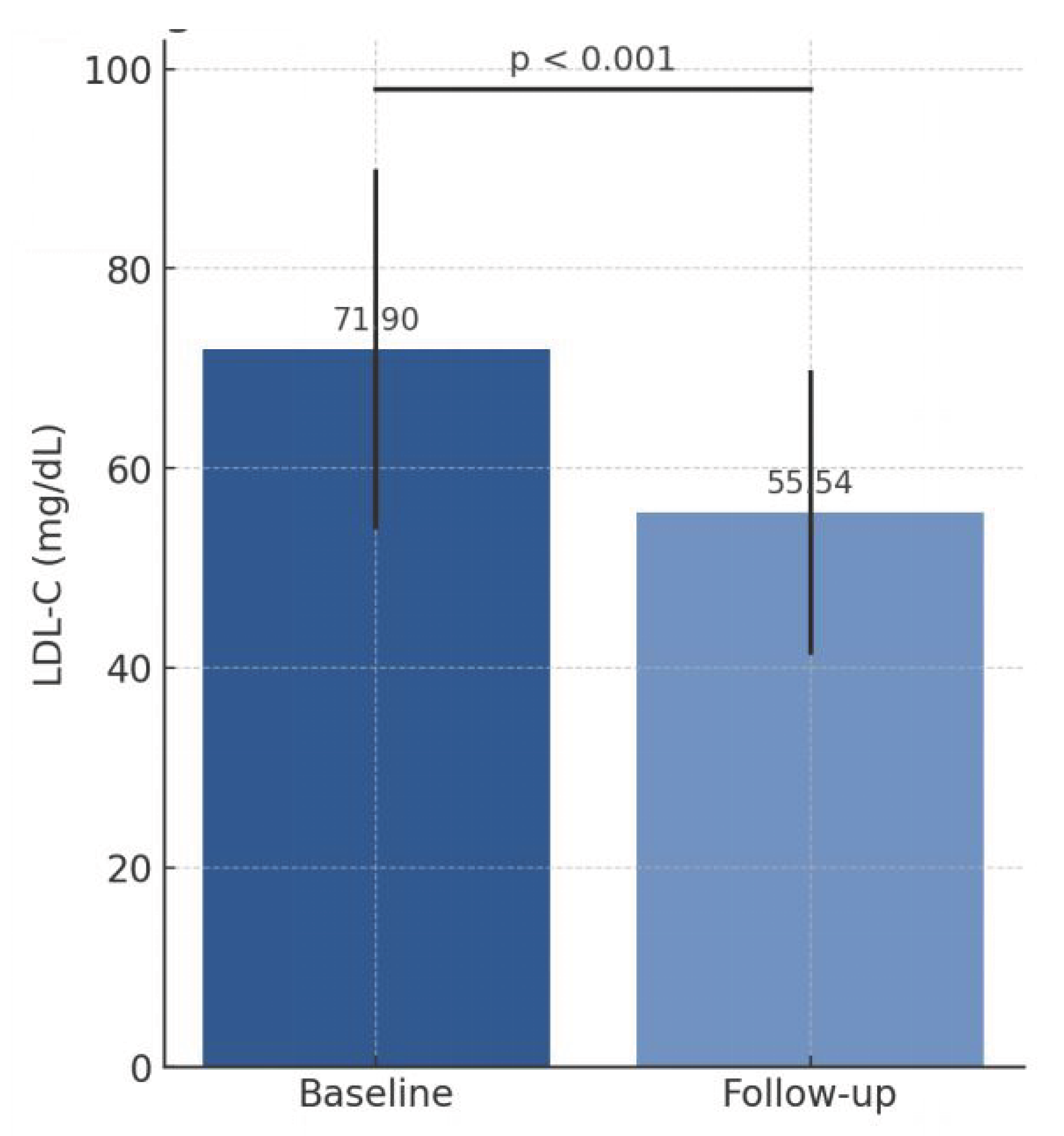

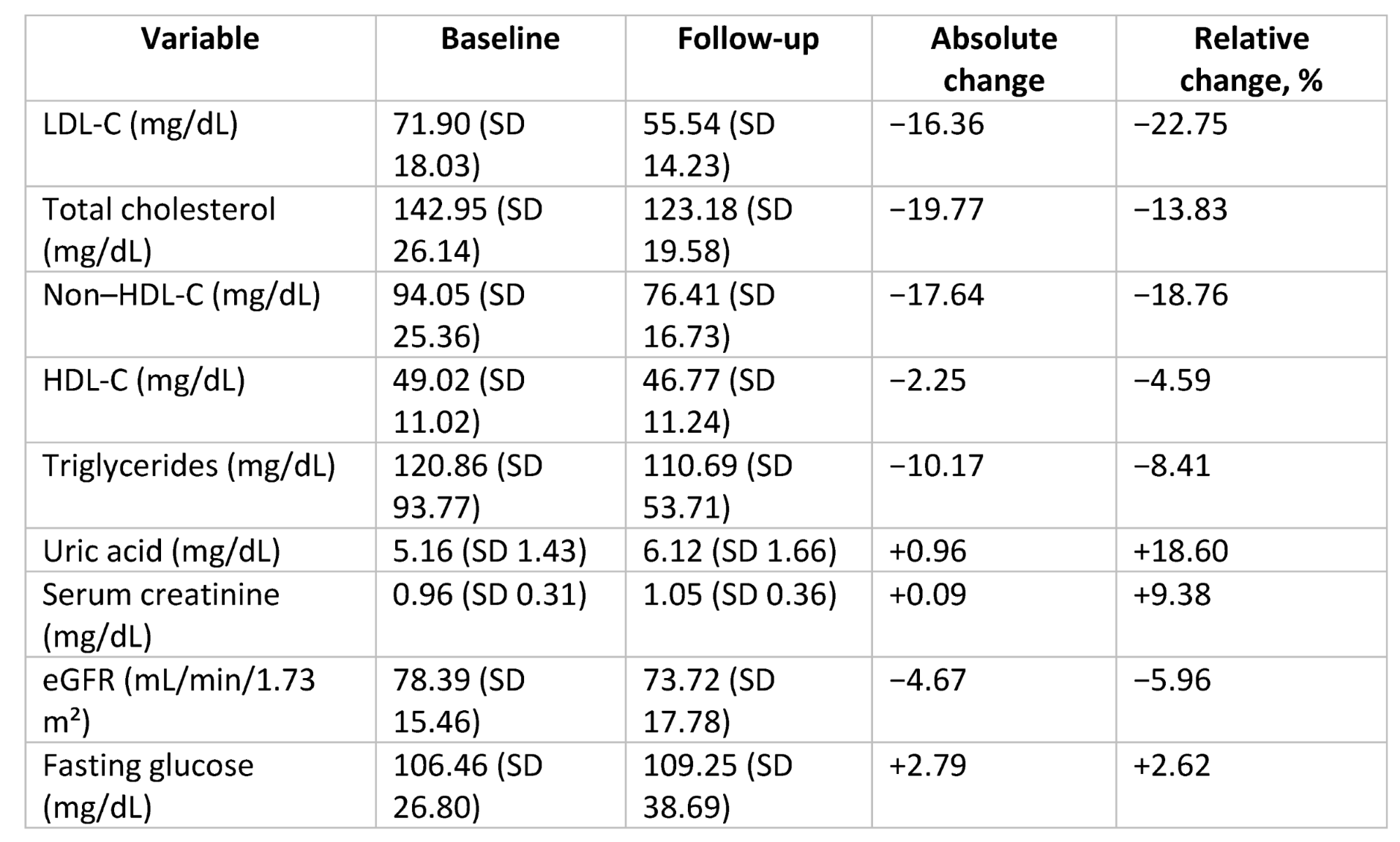

Addition of BA reduced LDL-C from 71.90 ± 18.03 mg/dL to 55.54 ± 14.23 mg/dL (absolute reduction 16.36 mg/dL, −22.75%, p < 0.001;

Table 2,

Figure 2). Total cholesterol and non–HDL-C decreased by 13.8% and 18.8%, respectively. Triglycerides and fasting glucose remained stable. HDL-C decreased slightly (−4.6%).

At follow-up, 48.3% achieved LDL-C <55 mg/dL. Considering historical untreated LDL-C, cumulative LDL-C reduction with sequential intensification reached 67.5%.

2.3. Interindividual Variability

No significant differences in LDL-C response between rosuvastatin- and atorvastatin-based regimens. PCSK9 inhibitor recipients had numerically larger reductions, but sample size was small. Approximately 13–14% of patients showed minimal or no LDL-C reduction, indicating heterogeneity in ACLY responsiveness.

2.4. Metabolic and Renal Effects

BA increased serum uric acid (+0.96 mg/dL, p < 0.001) without gout flares. Serum creatinine increased modestly; eGFR decreased ~6%, reversible and clinically non-relevant, consistent with tubular functional effects.

2.5. Predictors of LDL-C Reduction

Multivariable linear regression: higher historical untreated LDL-C (β = −0.515; p = 0.001) and diabetes mellitus (B = 13.8 mg/dL; p = 0.024) independently predicted greater LDL-C reduction.

2.6. Predictors of LDL-C Target Attainment

Binary logistic regression identified higher historical LDL-C (p = 0.026) and baseline uric acid (p = 0.026) as independent predictors of achieving LDL-C <55 mg/dL.

3. Discussion

Circulating lipid fractions and uric acid served as integrative markers of ACLY inhibition.

This real-world study demonstrates ACLY inhibition with BA provides substantial additional LDL-C reduction in CCS patients on intensive therapy. The 22.8% relative reduction aligns with pharmacodynamics and highlights the importance of upstream cholesterol synthesis inhibition. The modest HDL-C reduction is clinically negligible.

3.1. ACLY Inhibition as a Metabolic Lever

ACLY links glucose-derived citrate to cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis. Inhibiting ACLY reduces hepatic acetyl-CoA, attenuates cholesterol synthesis, and enhances LDLR-mediated clearance. Our findings support proportional LDL-C reduction across sequential therapies, consistent with log-linear LDL-C risk models [

1,

2,

3,

4].

3.2. Uric Acid as a Cardiometabolic Marker

Baseline uric acid association with LDL-C goal attainment may indicate a cardiometabolic phenotype responsive to combined cholesterol synthesis and absorption blockade. Genetic variability in ACLY or citrate flux may underlie interindividual differences.

3.3. Interindividual Variability

Heterogeneity in LDL-C response underscores the need to study genetic, metabolic, and pharmacokinetic determinants of ACLY responsiveness [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22].

3.4. Clinical Implications

BA can bridge conventional dual therapy and injectable agents, particularly in patients with high historical LDL-C exposure [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27].

3.5. Strengths and Limitations

Observational, single-centre design without control limits causal inference. Sample size was moderate; subgroup analyses, especially for PCSK9 inhibitors, were limited. No direct molecular or genetic biomarkers were assessed. Follow-up duration was short, and long-term cardiovascular outcomes were not evaluated. Strengths include prospective design, consecutive patient inclusion, and systematic safety assessment, enhancing translational relevance.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design and Population

Prospective, single-centre, observational study at Hospital Universitario San Pedro de Alcántara (Cáceres, Spain). 125 consecutive CCS patients ≥18 years with LDL-C ≥55 mg/dL despite ≥8 weeks of stable intensive therapy (high-intensity statin plus ezetimibe, or PCSK9 inhibitor plus ezetimibe in statin-intolerant patients) were included. Exclusions: age <18, pregnancy/breastfeeding, BA hypersensitivity, severe renal impairment (eGFR <30), chronic liver disease, active malignancy. Approved by CEIM; written informed consent obtained.

BA 180 mg/day added to background therapy. Baseline data: cardiovascular risk factors, comorbidities, prior interventions, anthropometrics, labs (total cholesterol, LDL-C, HDL-C, triglycerides, creatinine, eGFR, uric acid, fasting glucose). Follow-up labs ≥8 weeks after BA initiation; median 28 weeks (IQR 23–47). Adverse events and discontinuations recorded. LDL-C targets per 2025 ESC/EAS: <55 mg/dL for very-high-risk patients [

5].

4.2. Definition of Lipid Variables

Historical untreated LDL-C: first LDL-C measurement without therapy.

Pre-BA LDL-C: measurement immediately prior to BA initiation after ≥8 weeks of stable therapy.

LDL-C calculation: Friedewald formula if TG <150 mg/dL; standardized direct enzymatic assay if TG ≥150 mg/dL.

4.3. Study Endpoints

Primary: absolute and relative LDL-C change; proportion achieving LDL-C <55 mg/dL.

Secondary: changes in total cholesterol, non–HDL-C, HDL-C, TG, uric acid, creatinine, eGFR; tolerability; treatment discontinuation; predictors of LDL-C reduction and target attainment.

4.4. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables as mean ± SD or median [IQR]; normality assessed by Kolmogorov–Smirnov. Paired t-test/Wilcoxon for baseline vs. follow-up; categorical variables as counts/percentages, compared by χ2 or Fisher’s exact. Independent subgroups: unpaired t-test/Mann–Whitney U. Two-sided p<0.05 significant.

4.5. Regression Models

Multiple linear regression: independent predictors of absolute LDL-C reduction; variables with p<0.10 in univariable analyses included; multicollinearity assessed via VIF.

Binary logistic regression: factors associated with achieving LDL-C <55 mg/dL (forward stepwise); model calibration via Hosmer–Lemeshow, discrimination via ROC AUC.

Analyses performed with SPSS v29 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

5. Conclusions

In CCS patients not achieving LDL-C targets despite intensive therapy, ACLY inhibition with BA provides meaningful LDL-C reduction with acceptable metabolic and renal safety, supporting BA as a translational approach to hepatic cholesterol targeting and personalized lipid-lowering strategies.

Author Contributions

J.J. Gómez-Barrado: conceptualization, design, data collection, analysis, manuscript drafting. Y. Porras-Ramos, E. Jiménez-Baena, A.I. Fernández-Chamorro, P. Gómez-Turégano: manuscript revision, approval, accountability. All authors meet ICMJE criteria.

Funding

No external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon reasonable request to corresponding author, following institutional and ethical regulations.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to nursing and administrative staff of Cardiology Department, San Pedro de Alcántara Hospital, Cáceres, Spain.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

Ethics Statement

Study conducted per Declaration of Helsinki; approved by CEIM. Written informed consent obtained.

Declaration of Generative AI Use

ChatGPT (OpenAI) used for wording, translation, bibliography organization, and summarization. Authors reviewed, edited, and take full responsibility.

References

- Ference, B.A.; Ginsberg, H.N.; Graham, I.; Ray, K.K.; Packard, C.J.; Bruckert, E.; Hegele, R.A.; Krauss, R.M.; Raal, F.J.; Schunkert, H.; et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: Evidence from genetic, epidemiologic, and clinical studies. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 2459–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baigent, C.; Blackwell, L.; Emberson, J.; Holland, L.E.; Reith, C.; Bhala, N.; Peto, R.; Barnes, E.H.; Keech, A.; Simes, J.; et al. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: A meta-analysis of data from 170 000 participants in 26 randomized trials. Lancet 2010, 376, 1670–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, C.P.; Blazing, M.A.; Giugliano, R.P.; McCagg, A.; White, J.A.; Theroux, P.; Darius, H.; Lewis, B.S.; Ophuis, T.O.; Jukema, J.W.; et al. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 2387–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabatine, M.S.; Giugliano, R.P.; Keech, A.C.; Honarpour, N.; Wiviott, S.D.; Murphy, S.A.; Kuder, J.F.; Wang, H.; Liu, T.; Wasserman, S.M.; et al. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1713–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mach, F.; Baigent, C.; Catapano, A.L.; Koskinas, K.C.; Casula, M.; Badimon, L.; Chapman, M.J.; De Backer, G.G.; Delgado, V.; Ference, B.A.; et al. 2025 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: Lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, 74–111. [Google Scholar]

- Ballantyne, C.M.; Banach, M.; Barter, P.; Kastelein, J.J.P.; LaRosa, J.C.; Lepor, N.; Lorenzato, C.; Pedersen, T.R.; Tardif, J.C.; Wright, R.S.; et al. Efficacy and safety of bempedoic acid added to maximally tolerated statins: Pooled analysis from phase 3 trials. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e015149. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, A.C.; Leiter, L.A.; Stroes, E.S.G.; Baum, S.J.; Hanselman, J.C.; Jacobson, T.A.; Koren, M.J.; Laufs, U.; Leiter, L.A.; Robinson, J.G.; et al. Effect of bempedoic acid on LDL-C in patients with statin intolerance: The CLEAR Outcomes Trial. JAMA 2019, 321, 1148–1158. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt, D.L.; Lincoff, A.M.; Gibson, C.M.; Banach, M.; Ballantyne, C.M. Impact of bempedoic acid treatment on cardiovascular outcomes: Prespecified analysis from the CLEAR Outcomes randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2024, 9, 674–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, K.K.; Bays, H.E.; Catapano, A.L.; Lalwani, S.; Bloedon, L.T.; Sterling, L.R.; Shao, M.; Robinson, J.G.; Ballantyne, C.M. Safety and efficacy of bempedoic acid to reduce LDL cholesterol. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1022–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkosky, S.L.; Newton, R.S.; Day, E.A.; Ford, R.J.; Lhotak, S. Liver-specific ATP-citrate lyase inhibition with bempedoic acid improves lipid metabolism and reduces LDL-C. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, S.B.; Crass, R.L.; Chapel, S.; Shah, A. Pharmacodynamic modelling of bempedoic acid plus statin combinations. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 2022, 8, 578–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaidi, N.; Swinnen, J.V.; Smans, K. ATP-citrate lyase: A key player in cancer metabolism. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 3709–3714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wellen, K.E.; Thompson, C.B. Cellular metabolic stress: Considering how ATP-citrate lyase links metabolism to epigenetics and transcription. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; Danielson, E.; Fonseca, F.A.H.; Genest, J.; Gotto, A.M., Jr.; Kastelein, J.J.P.; Koenig, W.; Libby, P.; Lorenzatti, A.J.; MacFadyen, J.G.; et al. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 2195–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, C.P.; Blazing, M.A.; Giugliano, R.P.; McCagg, A.; White, J.A.; Theroux, P.; Darius, H.; Lewis, B.S.; Ophuis, T.O.; Jukema, J.W.; et al. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes (IMPROVE-IT). N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 2387–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, S.E.; Lincoff, A.M.; Brennan, D. Bempedoic acid and cardiovascular outcomes in statin-intolerant patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 1353–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banach, M.; Duell, P.B.; Gotto, A.M., Jr. Effect of bempedoic acid on atherogenic lipids. JAMA Cardiol. 2020, 5, 1124–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, K.K.; Nicholls, S.J.; Lincoff, A.M. Uric acid changes and gout incidence with bempedoic acid therapy. JACC Adv. 2025, 4, 102207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudano, I. Bempedoic acid: Results of the CLEAR program. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 27, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P. Inflammation and the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2024, 154, 107255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, K.K.; Aguiar, C.; Arca, M.; Connolly, D.L.; Eriksson, M.; Ferrières, J. SANTORINI Investigators. Combination therapy improves LDL management. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. Check DOI. 2024, 31, 1792–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostaza, J.M.; García-Ortiz, L.; Suárez-Tembra, M.A. Failure to achieve LDL-C goals in high-risk patients in Spain. Rev. Clin. Esp. 2025, 225, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jukema, J.W.; Gouni-Berthold, I. Early real-world insights on bempedoic acid and bempedoic acid plus ezetimibe. Atherosclerosis 2025, 407, 119582. [Google Scholar]

- Stulnig, T.M.; Gouni-Berthold, I.; Jukema, J.W. MILOS Austria real-world data on bempedoic acid. Atherosclerosis 2025, 407. [Google Scholar]

- Jadhav, S.B.; Crass, R.L.; Chapel, S. Pharmacodynamic modelling of bempedoic acid plus statins. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 2022, 8, 578–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, C.P. Patterns of statin intensification after myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 2190–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khunti, K. Adherence to lipid-lowering therapy in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2017, 40, 1233–1239. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |