1. Introduction

Teaching clinical skills is central to medical education, and the chosen instructional method has important implications for learner engagement, competence, and patient safety. Traditional approaches such as Halsted’s “see one, do one, teach one” model and conventional faculty demonstration emphasize observation followed by supervised performance, but often lack standardization and systematic learner involvement [

1]. Effective acquisition of these skills requires not only imitation but also structured observation, deliberate practice, dialogue, and timely feedback [

2]. In the conventional demonstration method, the instructor explains and performs the procedure in a single, often unstructured sequence, after which the trainee attempts the skill with minimal guidance and limited opportunities for interaction. This model is time-efficient, easy to organize, and therefore widely used in settings with constraints on faculty numbers and teaching time [

3,

4]. However, its largely passive format raises concerns about long-term skill acquisition, as students may not fully engage with the material, leading to weaker retention, lower proficiency, and delayed correction of errors due to restricted feedback opportunities [

5].

To address these limitations, structured stepwise models for procedural training have been developed, among which Peyton’s Four-Step Approach has gained particular prominence [

6]. Peyton’s method comprises four stages—demonstration, deconstruction, comprehension, and performance—that progressively shift responsibility from teacher to learner. By requiring the trainee to verbalize the procedure and then perform it, this approach integrates cognitive processing with psychomotor practice, encourages active participation, and facilitates immediate, targeted feedback. Randomized trials and systematic reviews indicate that Peyton’s approach can improve procedural performance, reduce time to competent execution, and enhance learner confidence compared with standard instruction, especially for complex skills and in settings with favourable teacher–student ratios.

However, implementation of Peyton’s Four-Step Approach is resource intensive. It was originally conceptualized for skills-lab teaching with a low student-to-teacher ratio, and later work has explored modifications and peer-led variants to accommodate larger groups. Evidence suggests that its effectiveness may be influenced by the nature of the task, the complexity of the procedure, and the learning environment and that outcome may be attenuated when delivered with higher learner numbers or less experienced instructors. In contrast, conventional demonstration remains widely used in routine clinical teaching, despite uncertainty about its comparative effectiveness for specific procedural skills and its impact on longer-term competence.

In otorhinolaryngology, foundational procedures such as anterior rhinoscopy, Trotter’s method, and anterior nasal packing are essential skills for interns and directly affect diagnostic accuracy and acute patient management. There is a relative paucity of data comparing structured stepwise methods like Peyton’s approach with conventional demonstration for teaching these ENT-specific skills. This study therefore sought to evaluate whether Peyton’s Four-Step Approach is more effective than conventional demonstration in teaching anterior rhinoscopy, Trotter’s method, and anterior nasal packing to ENT interns. The hypothesis was that Peyton’s method would result in higher OSCE scores and more favourable learner perceptions of skill acquisition and retention compared with traditional demonstration, thereby supporting its wider adoption in undergraduate ENT skills training.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This quasi-interventional study ran for three months (October-December 2024) at Government Medical College (GMC), Konni, after getting approval from the Institutional Research Committee (IRC).

2.2. Participants

We included interns doing their mandatory internship training at GMC Konni during the study period. We excluded anyone who didn’t want to take part in the OSCE exam. A total of 50 interns were recruited and randomly split into two equal groups using a lottery system (Group A: traditional demonstration, n=25; Group B: Peyton’s four-step method, n=25).

2.3. Intervention

Each group was broken into smaller batches of five interns. Both groups learned anterior rhinoscopy and anterior nasal packing using skill-lab models. Group A got standard faculty demonstration, while Group B used Peyton’s four-step approach with a different faculty member of similar experience. Both teachers were trained on both methods beforehand. Trotter’s method was taught and tested on simulated patients for both groups.

2.4. Data Collection

Skills were tested right after training using validated OSCE checklists for all three procedures. Students also filled out a questionnaire rating their experience with each teaching method.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Data was entered in Excel and analyzed with Jamovi software (version 2.3). We reported numbers as means ± standard deviations and compared groups using Mann-Whitney U tests. Performance was considered “good” if students scored ≥75% (22.5/30) across all skills. Categorical data was compared with Chi-square tests, with p<0.05 considered significant.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee and IRC. All participants gave written consent and could leave anytime. Random group assignment ensured fairness, no incentives were offered, and all data was kept anonymous and confidential.

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

Groups A (conventional demonstration) and B (Peyton’s four-step approach) were comparable in terms of gender distribution, with no significant differences (28 males [56%], 22 females [44%]).

Table 1 summarizes the baseline demographic characteristics of the 50 participants (25 per group).

3.2. Assessment Scores

Since scores for all three skills in both groups were non-normally distributed (Shapiro-Wilk test, p < 0.001), Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare demonstration and Peyton’s groups.

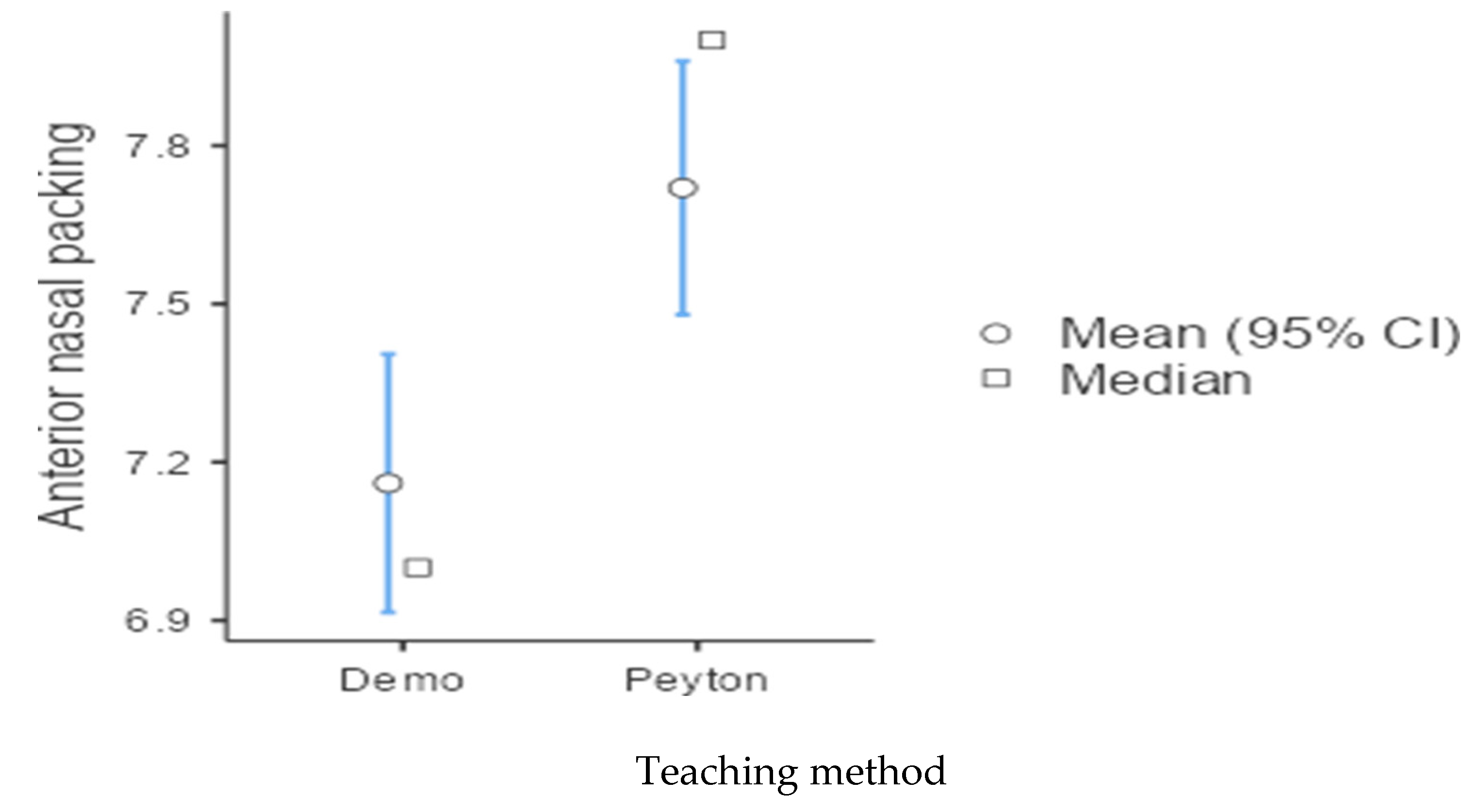

Table 2 presents the OSCE scores for each skill across groups. Significant differences favored Peyton’s method for Trotter’s method (p < 0.05) and anterior nasal packing (p < 0.05), but not for anterior rhinoscopy (p > 0.05).

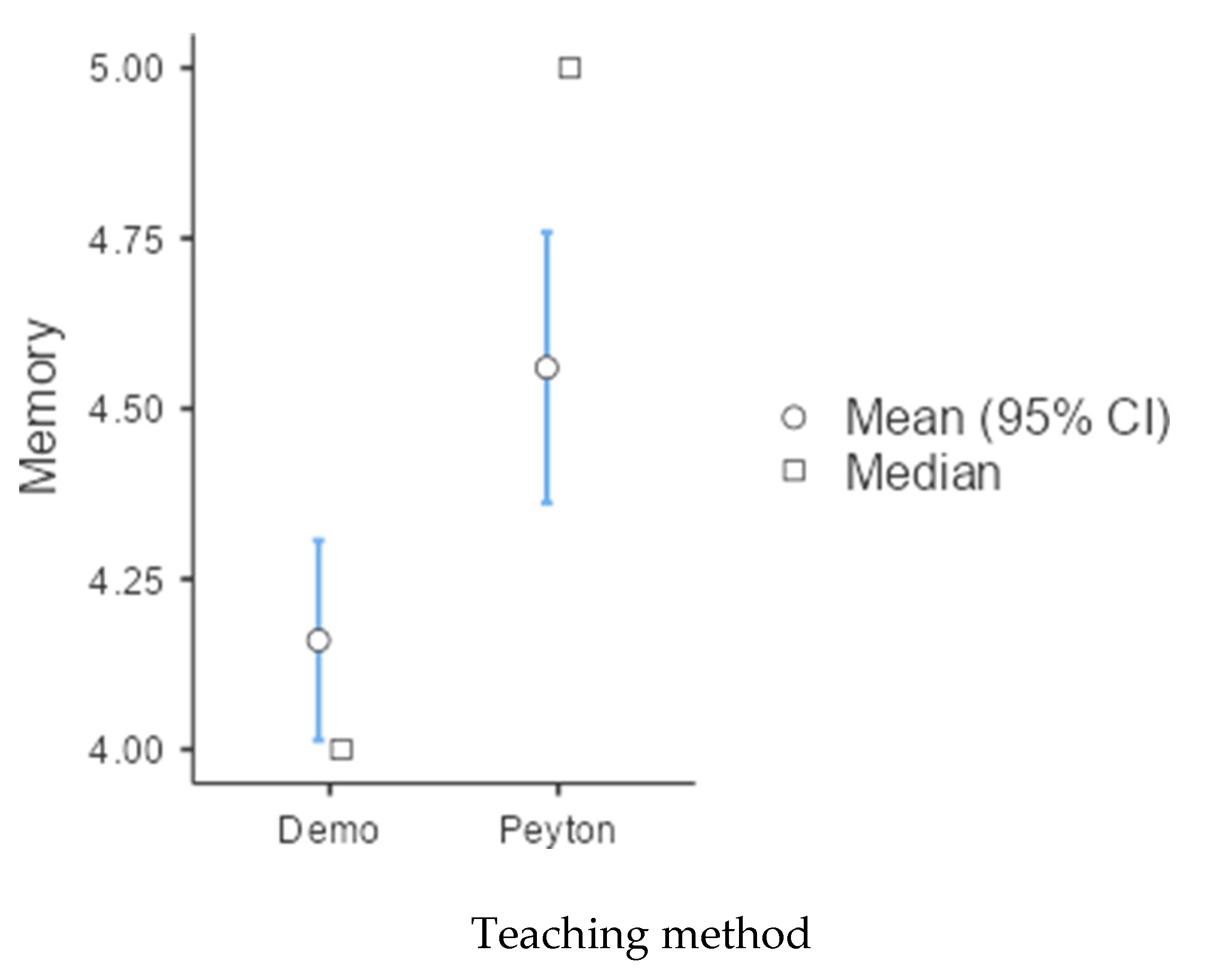

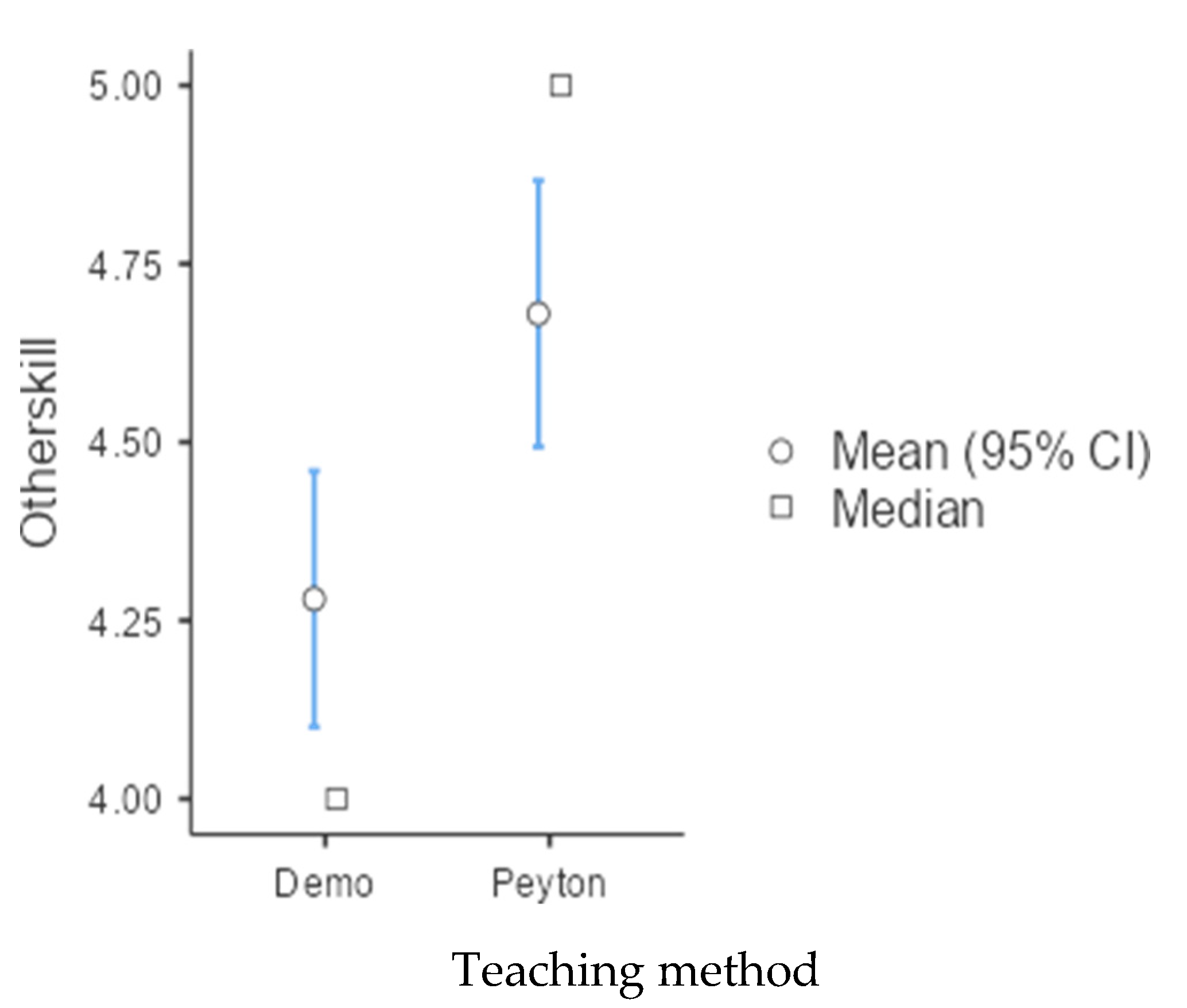

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 provide graphical representations of these comparisons.

3.3. Outcome Ratings

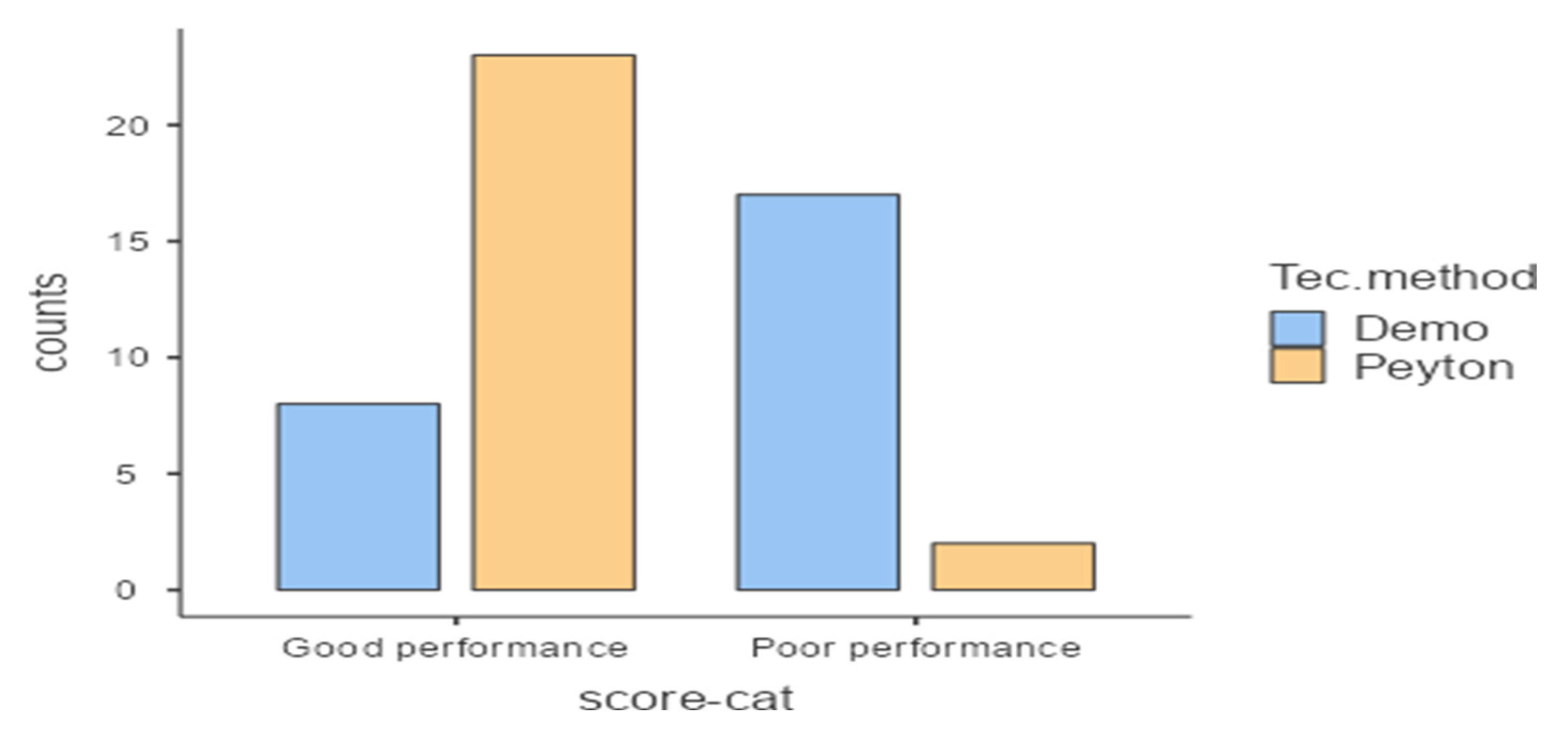

Chi-square testing indicated significantly higher good performance rates in Peyton’s group (92%) compared to the conventional group (32%; p < 0.001).

Table 3 shows the distribution of performance ratings, categorized as “good” (total score ≥75%, or 22.5/30 across skills).

Figure 4 illustrates this distribution graphically.

3.4. Perception Responses

Table 4 details Likert-scale questionnaire responses, analyzed via Mann-Whitney U tests. Peyton’s group reported significantly better skill memory recall (p = 0.004) and greater endorsement for applying the method to other skills (p = 0.005). No significant differences emerged in other perception domains (e.g., conceptual understanding, doubt clarification). These results reflect short-term learner perceptions post-training. This is also depicted in the figures 5 & 6 respectively.

Figure 6.

Teaching other Skills.

Figure 6.

Teaching other Skills.

4. Discussion

This study compared Peyton’s Four-Step Approach with traditional faculty demonstration when teaching three important ENT skills—anterior rhinoscopy, Trotter’s method, and anterior nasal packing—to interns at a government medical college. The results clearly showed that interns trained using Peyton’s method performed significantly better on the more challenging procedures: Trotter’s method (p=0.0098) and anterior nasal packing (p=0.004). Interestingly, for the simpler diagnostic skill of anterior rhinoscopy, both groups scored about the same. These findings make sense—they support the idea that Peyton’s structured, interactive approach really shines for skills that require more complex thinking, hand-eye coordination, and step-by-step practice, while it doesn’t offer much extra benefit for straightforward observation tasks that interns might pick up more easily either way.

Numerous studies have substantiated the advantages of Peyton’s Four-Step Approach over traditional methods in clinical skills training across various disciplines. In a study by Awad involving critical care nursing students, Peyton’s approach led to marked improvements in skill acquisition, self-confidence, and self-reported satisfaction, attributing these gains to the method’s emphasis on active participation and iterative feedback [

7]. Šurda et al. conducted a comprehensive review of ENT procedural education and concluded that passive observation, characteristic of conventional demonstration, results in slower skill acquisition, diminished learner confidence, and the necessity for repeated practice sessions to achieve mastery [

8]. Varghese’s comparative study of Peyton’s approach against conventional bedside teaching in medical students further corroborated its efficacy for clinical examination skills, noting sustained improvements in accuracy and speed [

9]. Similarly, Garg’s randomized controlled trial among undergraduates demonstrated that Peyton’s method facilitated faster skill mastery and translated to superior performance in authentic clinical scenarios [

10]. The modified Peyton’s approach for instructing small groups in skills-lab training sessions proved practicable, well-accepted by trainees, and easy for tutors to implement [

11].

These findings together show that Peyton’s step-by-step model—from the teacher quietly demonstrating, to students describing what they’re doing, then practicing under guidance, and finally doing it independently—really helps connect “knowing about” a skill with actually being able to do it well. This works especially well for procedures like nasal packing that need exact steps and good hand-eye coordination.

4.1. Memory Retention and Cognitive Reinforcement

A key strength of this study was the assessment of learner perceptions, which revealed a statistically significant preference for Peyton’s method in fostering memory recall of skills (p=0.004). This observation is consistent with Amaral et al.’s investigation into knowledge and skill retention among medical students, where structured teaching paradigms outperformed unstructured ones in promoting long-term encoding and retrieval [

12]. Giacomino et al.’s meta-analysis further provides robust evidence, pooling data from multiple randomized trials to confirm Peyton’s superior impact on procedural skill acquisition across health professions education [

13]. The cognitive benefits likely stem from the method’s deconstruction and comprehension phases, which compel learners to articulate procedural steps, thereby reinforcing neural pathways for both explicit memory (knowing “what” and “how”) and implicit memory (automatic execution). In contrast, conventional demonstration’s single-pass format may limit such deepening, leading to superficial familiarity rather than durable competence.

4.2. Student Satisfaction and Practical Implications

Interns trained via Peyton’s method consistently rated it higher across multiple domains, including conceptual clarity, doubt resolution, performance enhancement, and overall session interest, with the most pronounced difference in their endorsement for applying it to other skills (p=0.005). These perceptions echo Sherif et al.’s findings, where students perceived the video-modified Peyton’s 4-step technique as a well-structured, engaging, and adaptable method for learning spinal and neurological examinations in small groups, particularly valuing its integration of video-based instruction for understanding procedural steps [

14].

However, some studies have not found superiority for Peyton’s method. Traditional teaching and Peyton’s 4-step approach demonstrated equivalent effectiveness in teaching basic musculoskeletal ultrasound skills to undergraduate medical students, with qualitative analysis revealing high acceptance of both peer teaching strategies in a study by Gradl-Dietsch et al. [

15]. Despite the benefits, Peyton’s approach demands greater faculty time and preparation, as well as smaller group sizes for optimal delivery—challenges acknowledged in resource-constrained settings like ours, where we adapted it to cohorts of five using skill-lab models and simulated patients.

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

The study’s strengths include its forward-looking design, use of validated OSCE checklists, blind scoring by independent evaluators, and capturing both hard performance data and student feedback. On the flip side, it was done at just one center with a relatively small group of interns, only looked at immediate results rather than long-term skill retention, and didn’t test how skills held up over time. There’s also the chance that slight differences between the two teachers could have influenced results, even though they had similar experience and training.

4.4. Overall Impact

These results make a strong case for adding Peyton’s Four-Step Approach to ENT training programs, especially for moderately complex procedures. It could really help bridge the gap between classroom learning and real patient care, building student confidence and skills early on—which ultimately means safer patient care from new doctors. Future studies should test it across more hospitals, look at costs, and see if it works just as well for residents and in different training environments.

5. Conclusions

Peyton’s Four-Step Approach worked much better than traditional demonstration for teaching more complex ENT skills like Trotter’s method and nasal packing to interns. Students using this method got significantly higher OSCE scores (p<0.01) and reported better memory retention and overall satisfaction. For simpler tasks like anterior rhinoscopy, both groups performed about equally, but Peyton’s structured, hands-on style still led to greater student engagement, confidence, and skill mastery across the board.

These results make a clear case for adding Peyton’s approach to ENT training programs for medical students, especially using skill labs and simulated patients that work well even with limited time and faculty. By encouraging active practice and focused feedback, it overcomes the shortcomings of standard lectures and demos, helping new doctors become more competent sooner—which means safer patient care. Future studies across multiple centers should check long-term skill retention, how well it scales in different settings, and whether it’s cost-effective for wider use.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Sindhu Viswanath.; methodology, Gauri Priya and Lekshmi Reghunath.; software, Lekshmi Reghunath.; validation, Girish Subash and Gauri Priya.; formal analysis, Sindhu Viswanath.; investigation, Sindhu Viswanath and Girish Subash.; resources, Girish Subash and Lekshmi Reghunath.; data curation, Gauri Priya.; writing—original draft preparation, Sindhu Viswanath and Meer M Chisthi.; writing—review and editing, Sindhu Viswanath and Meer M Chisthi.; visualization, Gauri Priya.; supervision, Sindhu Viswanath and Girish Subash.; project administration, Sindhu Viswanath. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Government Medical College Konni (IRCNo:13/IRC/2024 October 2024).”.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the subjects to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results is available and will be provided on demand.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Dr Asha KP, Associate Professor, Department of Community Medicine at GMC Konni for helping us with the statistical analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Romero P, Günther P, Kowalewski KF, Friedrich M, Schmidt MW, Trent SM, De La Garza JR, Müller-Stich BP, Nickel F. Halsted’s “See One, Do One, and Teach One” versus Peyton’s Four-Step Approach: A Randomized Trial for Training of Laparoscopic Suturing and Knot Tying. J Surg Educ. 2018 Mar-Apr;75(2):510-515. Epub 2017 Aug 8. PMID: 28801083. [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal U, Supe A, Gupta P, Singh T. Producing Competent Doctors - The Art and Science of Teaching Clinical Skills. Indian Pediatr. 2017 May 15;54(5):403-409. Epub 2017 Feb 2. PMID: 28159947. [CrossRef]

- Burgess A, van Diggele C, Roberts C, Mellis C. Feedback in the clinical setting. BMC Med Educ. 2020 Dec 3;20(Suppl 2):460. PMID: 33272265; PMCID: PMC7712594. [CrossRef]

- Prober CG, Khan S. Medical education reimagined: a call to action. Acad Med. 2013 Oct;88(10):1407-10. PMID: 23969367. [CrossRef]

- Blue AV, Stratton TD, Plymale M, DeGnore LT, Schwartz RW, Sloan DA. The effectiveness of the structured clinical instruction module. Am J Surg. 1998 Jul;176(1):67-70. PMID: 9683137. [CrossRef]

- Walker M, Peyton R. Teaching in the theatre. In: Peyton JWR, Editor. Teaching and learning in medical practice. Rickmansworth, UK: Manticore Europe Limited; 1998. p. 171-80.

- Ahmed, F.R., Morsi, S.R., & Mostafa, H.M. (2018). Effect of Payton ‘ s Four Step Approach on Skill Acquisition , Self-Confidence and Self-Satisfaction among Critical Care Nursing Students . IOSR Journal of Nursing and Health Science (IOSR-JNHS)e-ISSN: 2320–1959.p- ISSN: 2320–1940 Volume 7, Issue 6 Ver. IV. (Nov.-Dec.2018), PP 38-47.

- Šurda P, Barac A, Mobaraki Deghani P, Jacques T, Langdon C, Pimentel J, Mathioudakis AG, Tomazic PV. Training in ENT; a comprehensive review of existing evidence. Rhinology Online. 2018;1:77-84. [CrossRef]

- Varghese S, Abraham L. Comparison of Peyton’s Four-Step Approach With the Conventional Bedside Technique in Teaching Clinical Examination Skills to Medical Students. Cureus. 2024 Feb 18;16(2):e54397. PMID: 38505435; PMCID: PMC10950315. [CrossRef]

- Garg R, Sharma G, Chaudhary A, Mehra S, Loomba PS, Chauhan VD. Evaluation of Peyton’s Four-Step Approach for Skill Acquisition in Undergraduate Medical Students: A Prospective Randomized Study. Med Rxiv 2023. 07.27.23293240.

- Nikendei C, Huber J, Stiepak J, Huhn D, Lauter J, Herzog W, Jünger J, Krautter M. Modification of Peyton’s four-step approach for small group teaching - a descriptive study. BMC Med Educ. 2014 Apr 2;14:68. PMID: 24690457; PMCID: PMC3976361. [CrossRef]

- Amaral F, Troncon LEA. Retention of Knowledge and Clinical Skills by Medical Students: A Prospective, Longitudinal, One-Year Study Using Basic Pediatric Cardiology as a Model. The Open Med Educ J. 2013;6:48-54. [CrossRef]

- Giacomino K, Caliesch R, Sattelmayer KM. The effectiveness of the Peyton’s 4-step teaching approach on skill acquisition of procedures in health professions education: A systematic review and meta-analysis with integrated meta-regression. Peer J. 2020 Oct 9;8:e10129. PMID: 33083149; PMCID: PMC7549471. [CrossRef]

- Sherif R, John E, McCarthy MJH. Exploring medical student perceptions of a video-modified Peyton’s 4-step technique for teaching spinal and neurological examinations. Med Educ Online. 2025 Dec;30(1):2519391. Epub 2025 Jun 16. PMID: 40518978; PMCID: PMC12172078. [CrossRef]

- Gradl-Dietsch G, Hitpaß L, Gueorguiev B, Nebelung S, Schrading S, Knobe M. Undergraduate Curricular Training in Musculoskeletal Ultrasound by Student Teachers: The Impact of Peyton’s Four-Step Approach. Z Orthop Unfall. 2019 Jun;157(3):270-278. English, German. Epub 2018 Oct 12. PMID: 30312980. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).