Submitted:

29 December 2025

Posted:

30 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

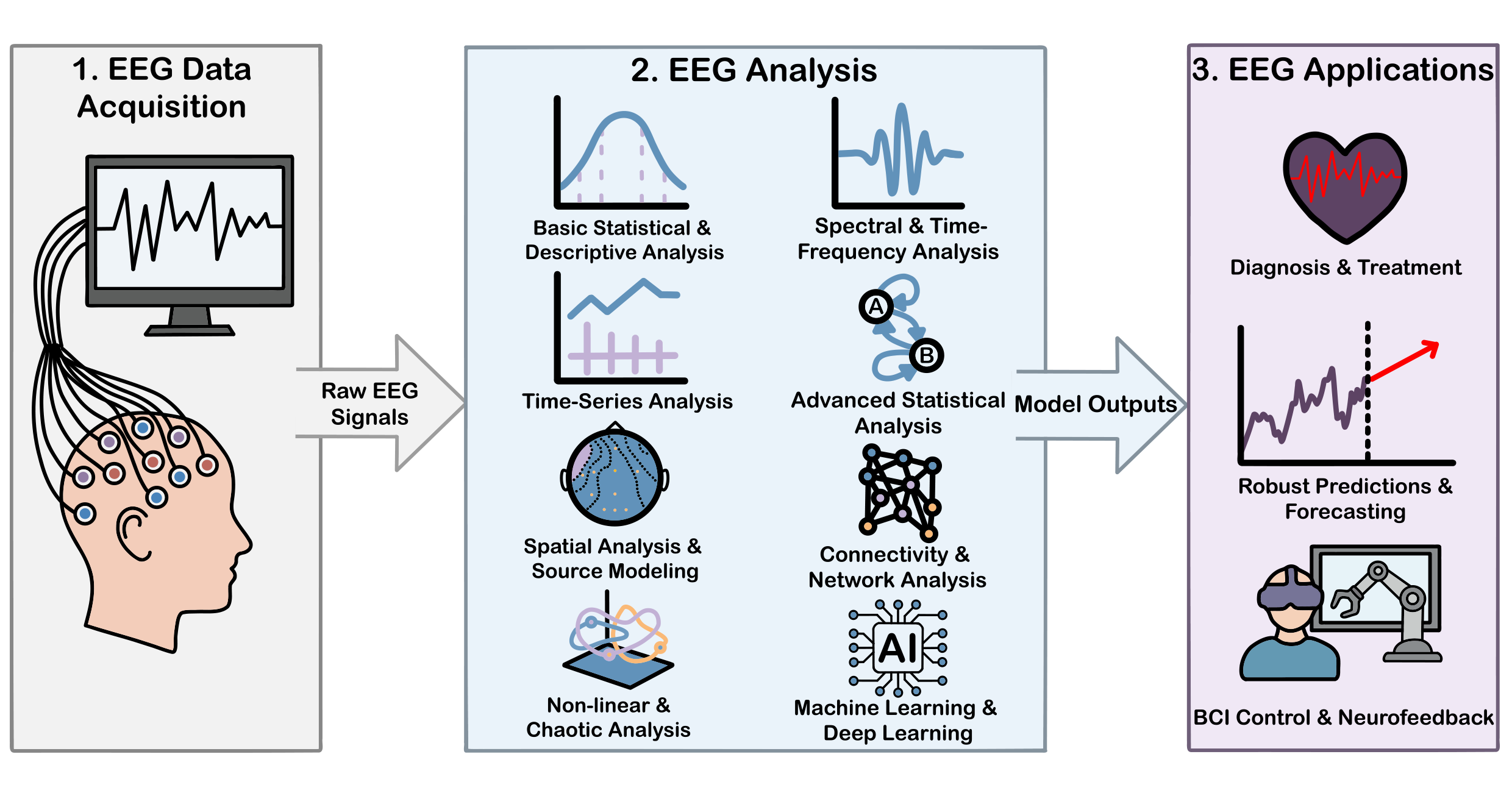

Electroencephalography (EEG) has transitioned from a subjective observational method into a data-intensive analytical field that utilises sophisticated algorithms and mathematical modeling. This progression encompasses developments in signal preprocessing, artifact removal, and feature extraction techniques including time-domain, frequency-domain, time-frequency, and nonlinear complexity measures. To provide a holistic foundation for researchers, this review begins with the neurophysiological basis, recording technique and clinical applications of EEG, while maintaining its primary focus on the diverse methods used for signal analysis. It offers an overview of traditional mathematical techniques used in EEG analysis, alongside contemporary, state-of-the-art methodologies. Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) architectures, such as Support Vector Machines (SVMs), Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), and transformer models, have been employed to automate feature learning and classification across diverse applications. We conclude that the next generation of EEG analysis will likely converge into Neuro-Symbolic architectures, synergising the generative power of foundation models with the rigorous interpretability of signal theory.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

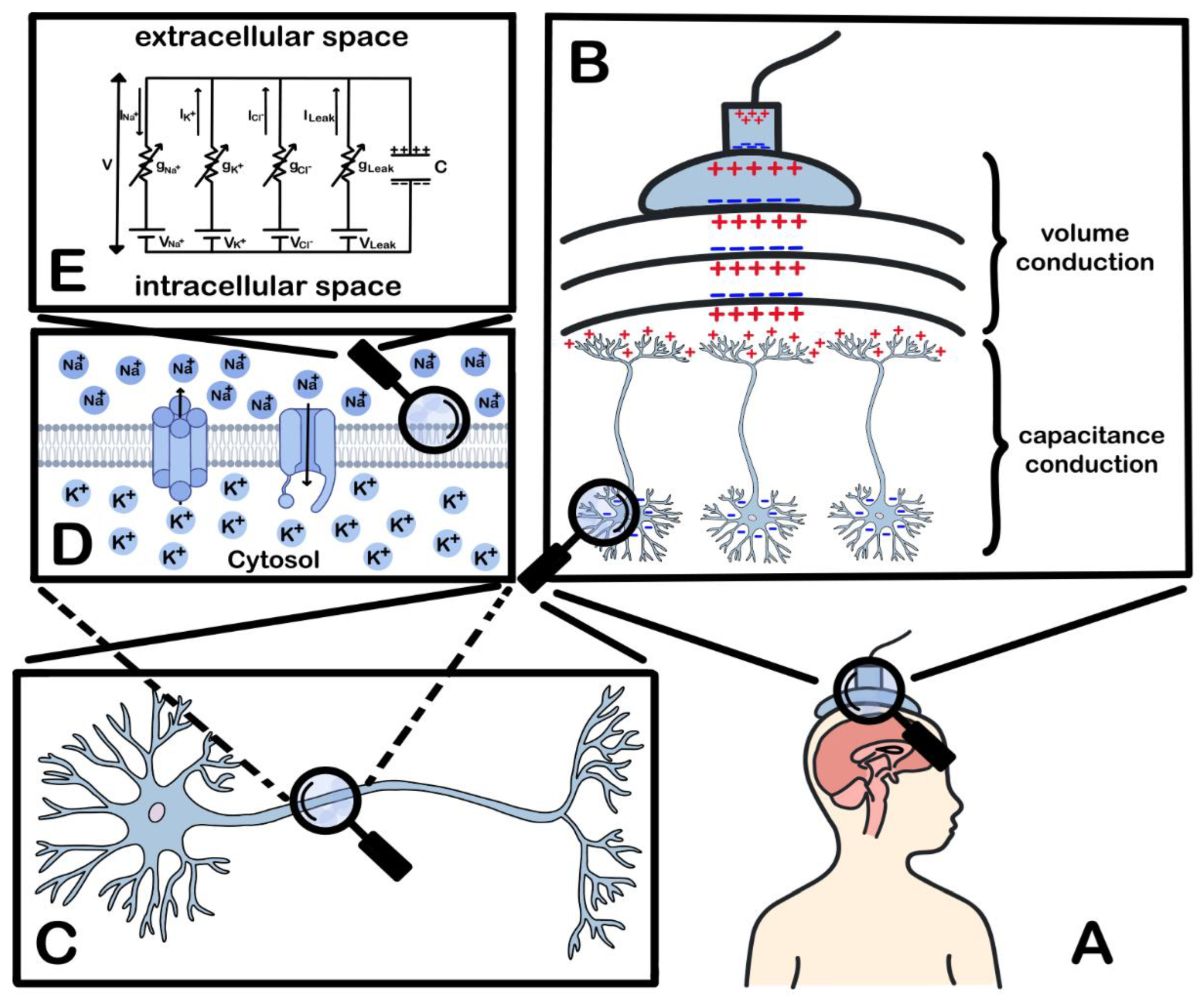

2. Biophysical Principles and Neurophysiological Basis

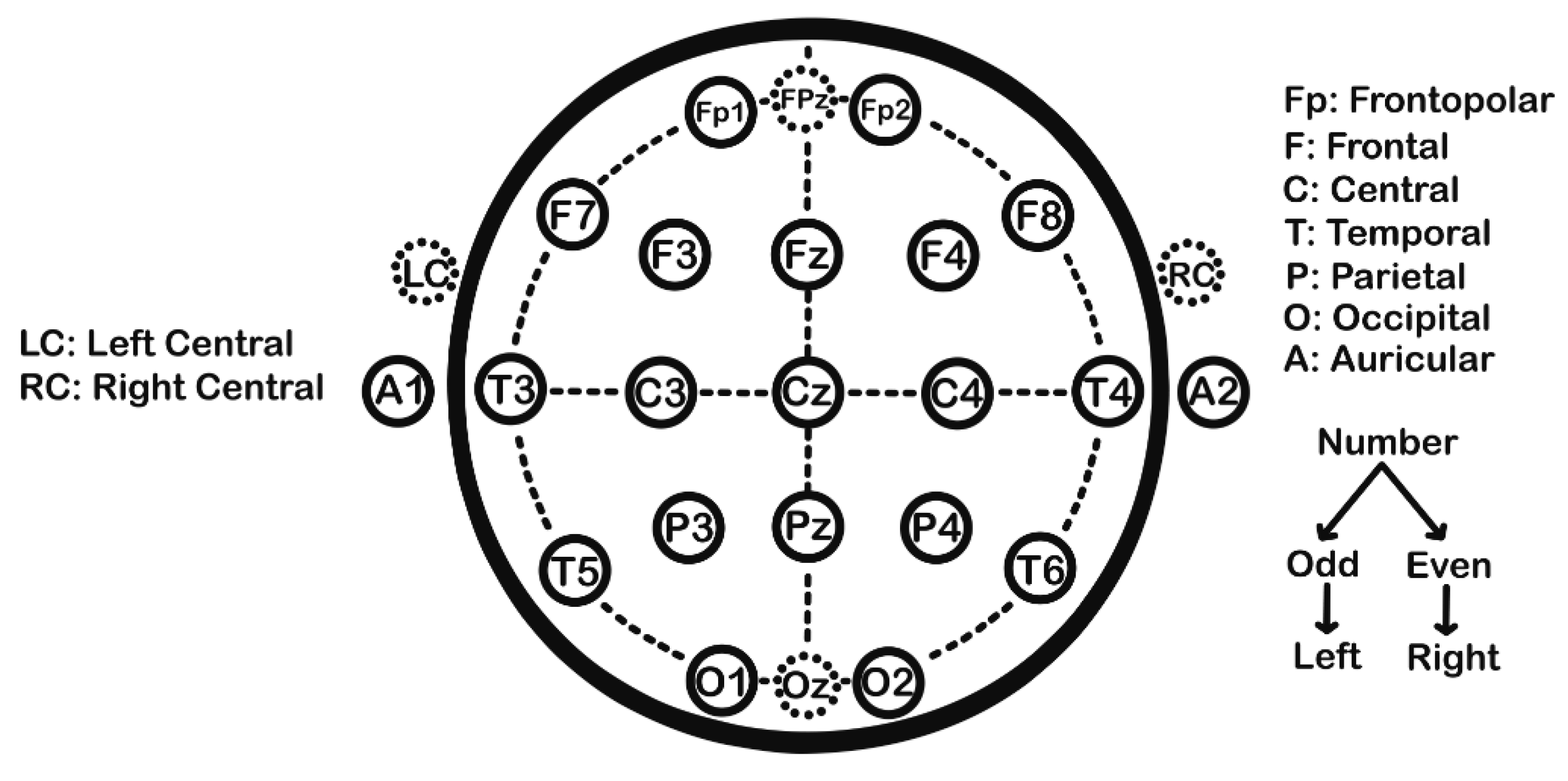

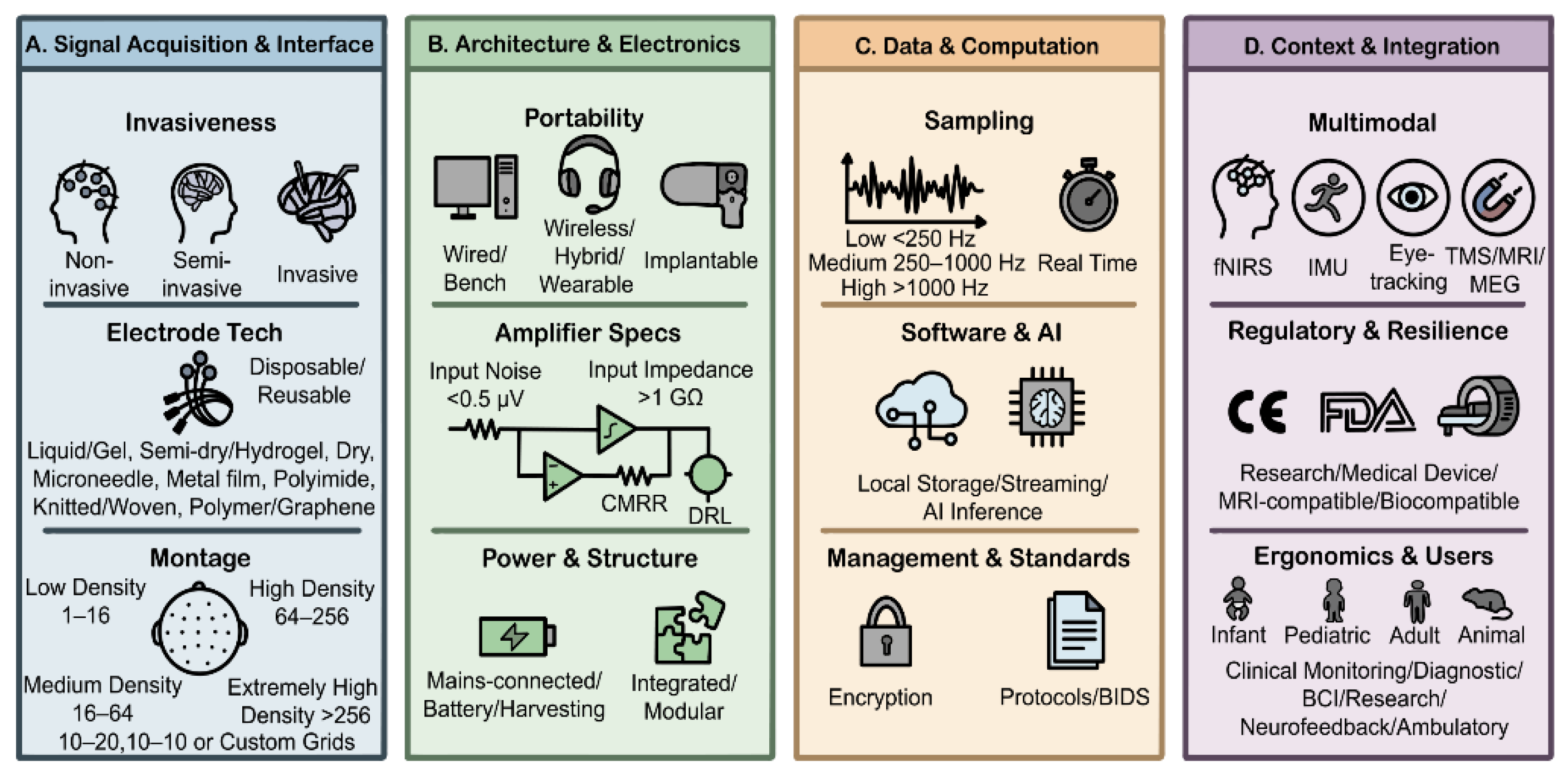

3. Recording Technique

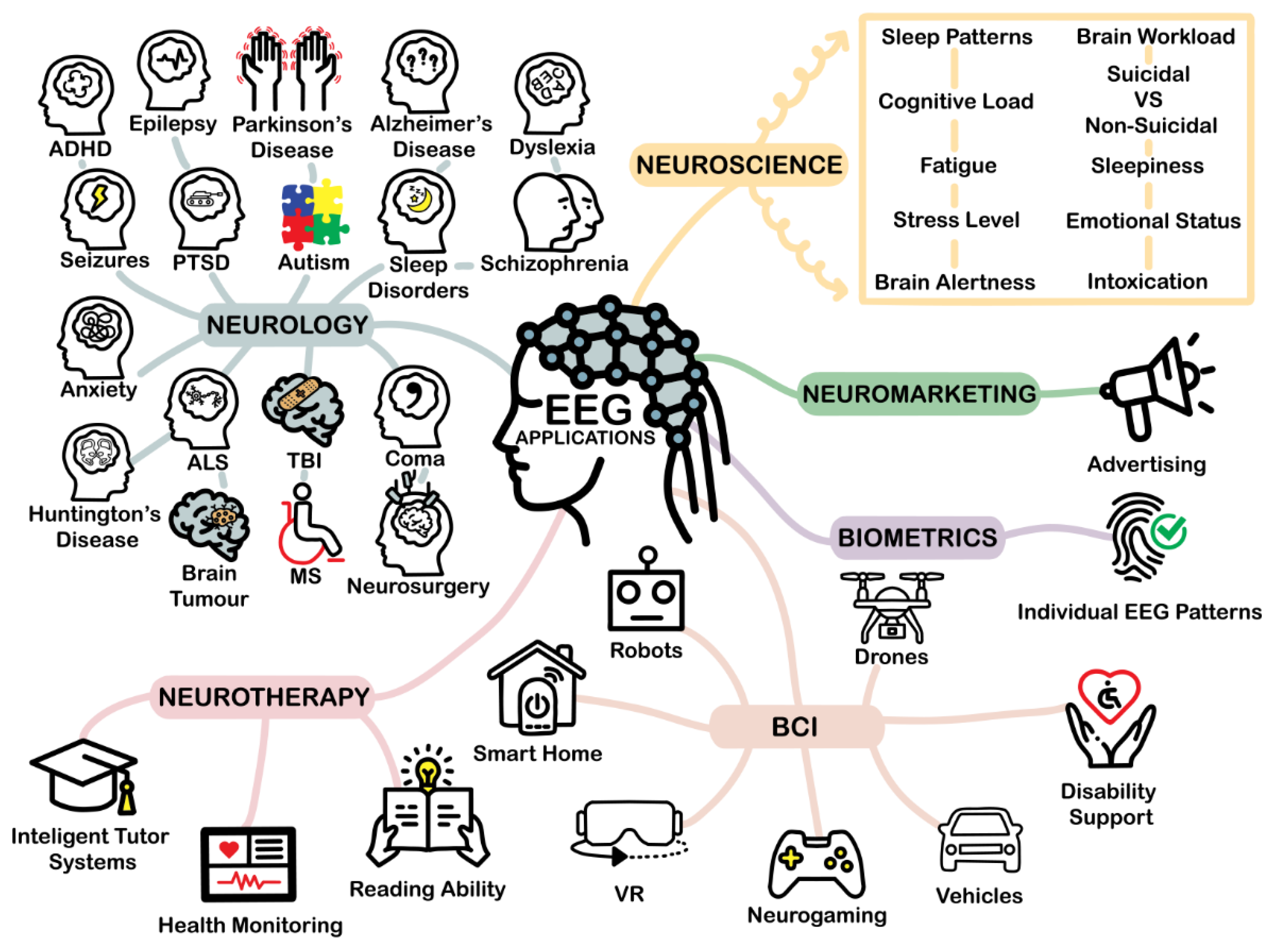

4. Applications

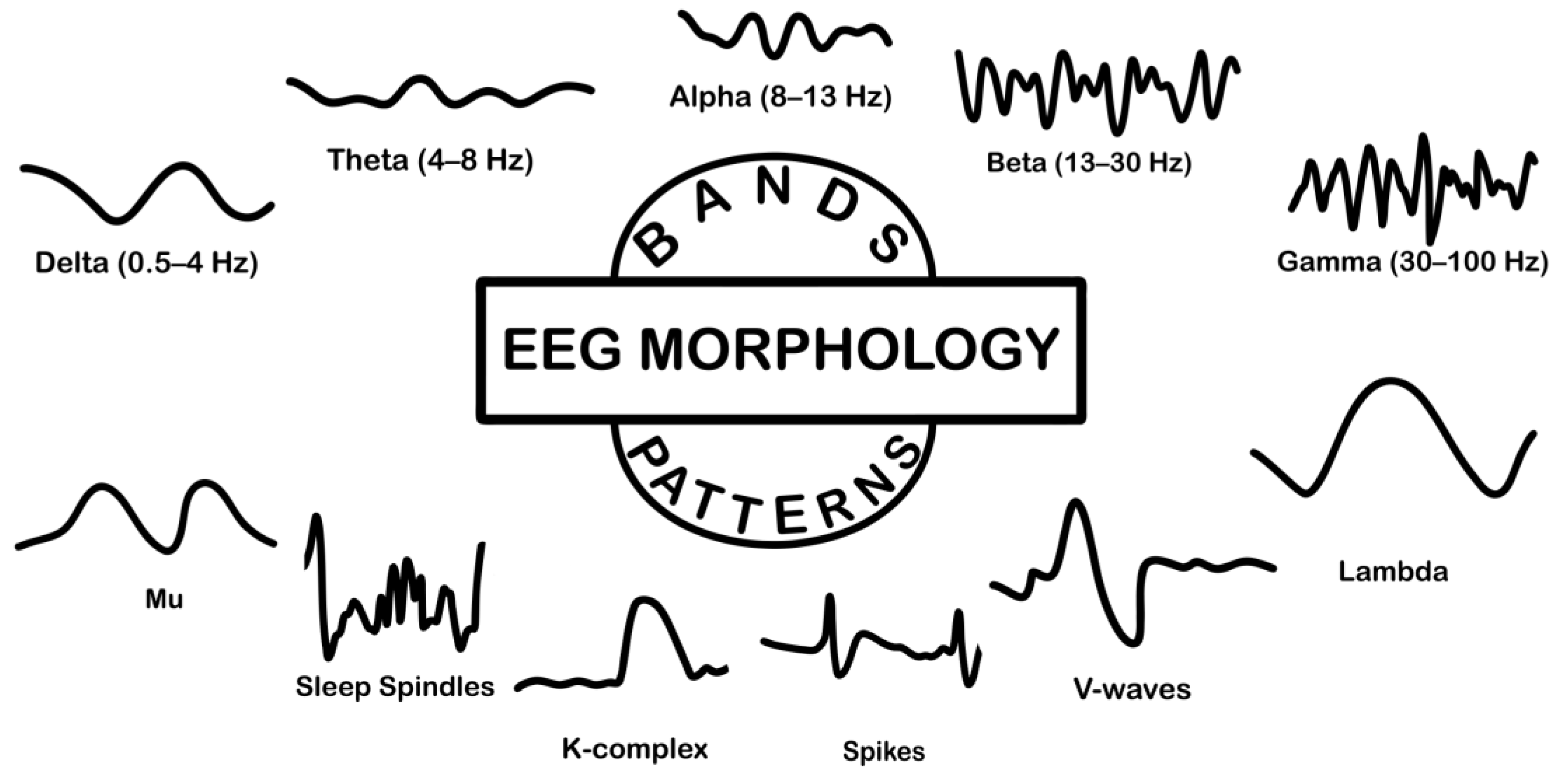

5. Basic Characteristics

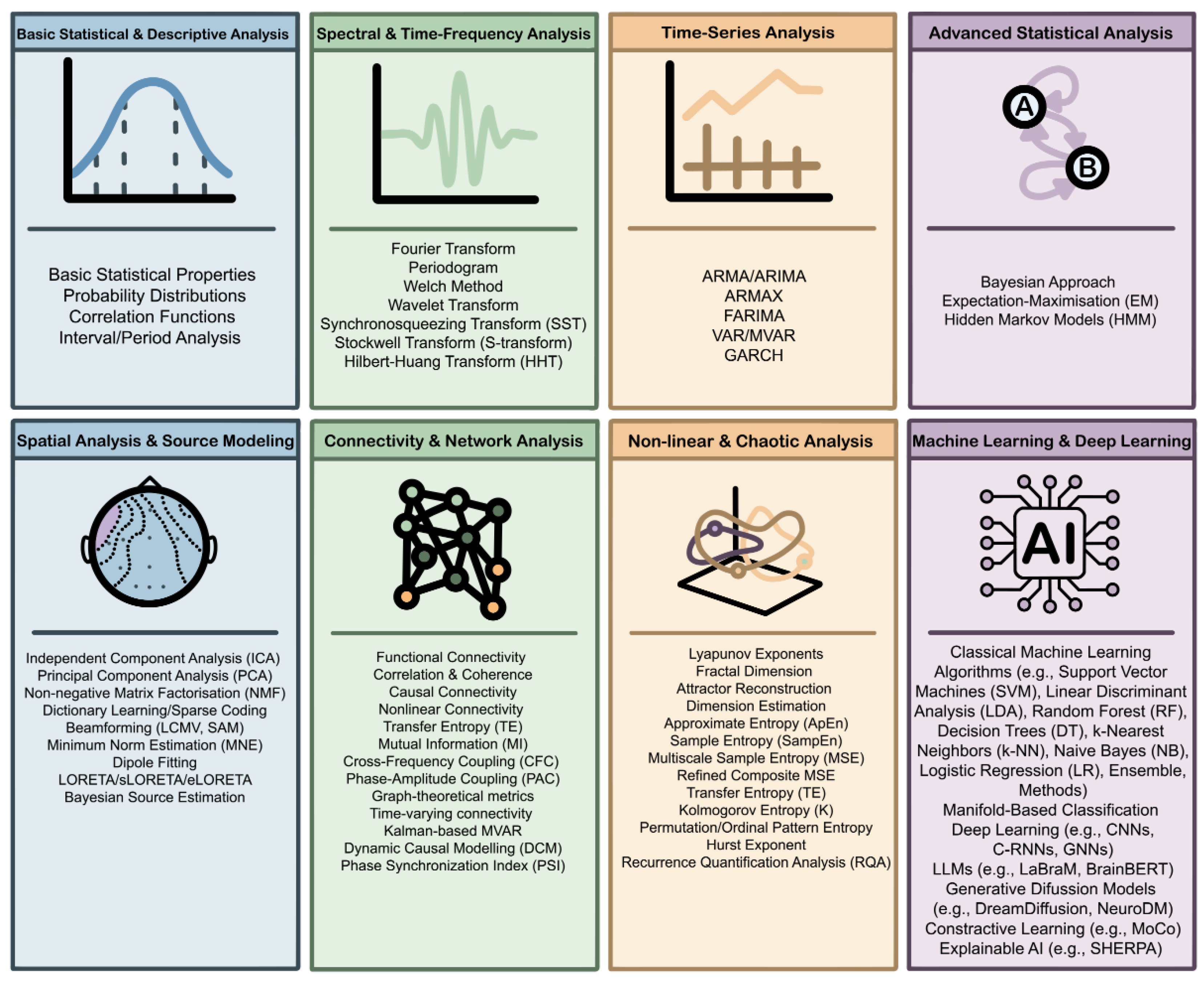

6. Methods for EEG Processing

6.1. Basic Statistical & Descriptive Analysis

6.2. Spectral & Time-Frequency Analysis

6.3. Time-Series Analysis

6.4. Advanced Statistical Analysis

6.5. Spatial Analysis & Source Modeling

6.6. Connectivity & Network Analysis

6.7. Nonlinear & Chaotic Analysis

6.8. Machine Learning & Deep Learning

7. Future Trajectory and Evolution

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EEG | Electroencephalography |

| HH | Hodgkin-Huxley |

| LFPs | local field potentials |

| AHPs | afterhyperpolarisations |

| ADCs | analog-to-digital converters |

| ECoG | electrocorticography |

| BCI | brain-computer interfaces |

| RMS | Root Mean Square |

| CMRR | Common Mode Rejection Ratio |

| TTL | Transistor-Transistor Logic |

| PTP | Peak-to-Peak |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| BLE | Bluetooth Low Energy |

| BIDS | Brain Imaging Data Structure |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| EGD | Esophagogastroduodenoscopy |

| TMS | Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation |

| fMRI | functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| MEG | Magnetoencephalography |

| CTFT | Continuous Time Fourier Transform |

| DFT | Discrete Fourier Transform |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| SFFT | Short-Time Fourier Transform |

| PSD | power spectral density |

| CWT | Continuous Wavelet Transform |

| DWT | Discrete Wavelet Transform |

| MRA | multiresolution analysis |

| WPD | Wavelet Packet Decomposition |

| ERPs | Event Related Potentials |

| SST | Synchrosqueezing Transform |

| WT | Wavelet Transform |

| S-transform | Stockwell Transform |

| EMD | Empirical Mode Decomposition |

| IMFs | Intrinsic Mode Functions |

| AR | Autoregressive |

| MA | Moving Average |

| ARMA | Autoregressive Moving Average |

| ARIMA | Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average |

| ARMAX | Autoregressive Moving Average with Exogenous Inputs |

| FARIMA | Fractional ARIMA |

| VAR | Vector Autoregressive |

| MVAR | Multivariate VAR |

| DTF | Directed Transfer Function |

| PDC | Partial Directed Coherence |

| GARCH | Generalised Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| BIC | Bayesian Information Criterion |

| EM | Expectation-Maximisation |

| HMM | Hidden Markov Models |

| DCM | Dynamic Causal Modelling |

| ICA | Independent Component Analysis |

| IVA | Independent Vector Analysis |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| NMF | Non-Negative Factorisation |

| EMD | Empirical Mode Decomposition |

| MNE | Minimum-Norm Estimate |

| DTF | Directed Transfer Function |

| PDC | Partial Directed Coherence |

| TE | Transfer Entropy |

| MI | Mutual Information |

| PLV | Phase-Locking Value |

| PLI | Phase-Lag Index |

| AEC | Amplitude Envelope Correlation |

| CFC | Cross-Frequency Coupling |

| PAC | Phase-Amplitude Coupling |

| PSI | Phase Synchronisation Index |

| ApEn | Approximate entropy |

| SampEn | Sample Entropy |

| MSE | Multiscale Sample Entropy |

| RCMSE | Refined Composite MSE |

| K | Kolmogorov entropy |

| PE | Permutation entropy |

| H | Hurst exponent |

| RQA | Recurrence Quantification Analysis |

| SVM | Support Vector Machines |

| SPD | Symmetric Positive Definite |

| AIRM | Affine Invariant Riemannian Metric |

| TSM | Tangent Space Mapping |

| RPA | Riemannian Procrustes Analysis |

| CNNs | Convolutional Neural Networks |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| GRU | Gated Recurrent Units |

| C-RNN | Convolutional-Recurrent Neural Network |

| GNNs | Neural Networks |

| LLMs | Large Language Models |

| DDPMs | Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models |

| EV-Transformer | EEG-Visual-Transformer |

| SSM | Structured State-Space Model |

| MoCo | Momentum Contrast |

| CPC | Contrastive Predictive Coding |

| XAI | Explainable AI |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| LRP | Layer-wise Relevance Propagation |

| SHERPA | SHAP-based ERP Analysis |

Appendix A

References

- Klonowski, W. Everything You Wanted to Ask about EEG but Were Afraid to Get the Right Answer. Nonlinear Biomed Phys 2009, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.Q.; Ibrahim, H.; Abdullah, M.Z.; Abdullah, J.M.; Suandi, S.A.; Azman, A. Artifacts and Noise Removal for Electroencephalogram (EEG): A Literature Review. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Symposium on Computer Applications & Industrial Electronics (ISCAIE), IEEE, April 2018; pp. 326–332.

- Nolte, G.; Bai, O.; Wheaton, L.; Mari, Z.; Vorbach, S.; Hallett, M. Identifying True Brain Interaction from EEG Data Using the Imaginary Part of Coherency. Clinical Neurophysiology 2004, 115, 2292–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardey, J.; Roberts, S.; Tarassenko, L. A Review of Parametric Modelling Techniques for EEG Analysis. Med Eng Phys 1996, 18, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subha, D.P.; Joseph, P.K.; Acharya U, R.; Lim, C.M. EEG Signal Analysis: A Survey. J Med Syst 2010, 34, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siuly, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y. EEG Signal Analysis and Classification; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-47652-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, R.; Meena, H.K. Emerging Trends in EEG Signal Processing: A Systematic Review. SN Comput Sci 2024, 5, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafaei, E.; Hosseini, M. Transformers in EEG Analysis: A Review of Architectures and Applications in Motor Imagery, Seizure, and Emotion Classification. Sensors 2025, 25, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G. Statistical Analysis. In EEG Signal Processing and Feature Extraction; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2019; pp. 335–375. [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, S.; Zito, J.; Rao, V.R.; Vannucci, M. Time-Series Analysis. In Statistical Methods in Epilepsy; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, 2024; pp. 166–200. [Google Scholar]

- Obermaier, B.; Guger, C.; Neuper, C.; Pfurtscheller, G. Hidden Markov Models for Online Classification of Single Trial EEG Data. Pattern Recognit Lett 2001, 22, 1299–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koles, Z.J. Trends in EEG Source Localization. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1998, 106, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiarion, G.; Sparacino, L.; Antonacci, Y.; Faes, L.; Mesin, L. Connectivity Analysis in EEG Data: A Tutorial Review of the State of the Art and Emerging Trends. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pritchard, W. s.; Duke, D. w. Measuring Chaos in the Brain: A Tutorial Review of Nonlinear Dynamical Eeg Analysis. International Journal of Neuroscience 1992, 67, 31–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.; Torres, J.; Murhekar, A.; Liu, C.; Mishra, A.; Gwizdka, J.; Roychowdhury, S. A Survey on Bridging EEG Signals and Generative AI: From Image and Text to Beyond. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.-B.; Zhao, L.-M.; Lu, B.-L. Large Brain Model for Learning Generic Representations with Tremendous EEG Data in BCI. Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2024) 2024.

- Li, Z.; Zheng, W.-L.; Lu, B.-L. Gram: A Large-Scale General EEG Model for Raw Data Classification and Restoration Tasks. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2025 - 2025 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), IEEE, April 6 2025; pp. 1–5.

- Luo, J.; Yang, L.; Liu, Y.; Hu, C.; Wang, G.; Yang, Y.; Yang, T.-L.; Zhou, X. Review of Diffusion Models and Its Applications in Biomedical Informatics. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2025, 25, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkin, A.L.; Huxley, A.F. Resting and Action Potentials in Single Nerve Fibres. J Physiol 1945, 104, 176–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catterall, W.A.; Raman, I.M.; Robinson, H.P.C.; Sejnowski, T.J.; Paulsen, O. The Hodgkin-Huxley Heritage: From Channels to Circuits. The Journal of Neuroscience 2012, 32, 14064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkin, A.L.; Huxley, A.F.; Katz, B. Measurement of Current-Voltage Relations in the Membrane of the Giant Axon of Loligo. J Physiol 1952, 116, 424–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgkin, A.L.; Huxley, A.F. A Quantitative Description of Membrane Current and Its Application to Conduction and Excitation in Nerve. J Physiol 1952, 117, 500–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett, M.W.; Larkman, P.M. The Action Potential. Pract Neurol 2007, 7, 192. [Google Scholar]

- Ahlfors, S.P.; Han, J.; Belliveau, J.W.; Hämäläinen, M.S. Sensitivity of MEG and EEG to Source Orientation. Brain Topogr 2010, 23, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Broek, S.P.; Reinders, F.; Donderwinkel, M.; Peters, M.J. Volume Conduction Effects in EEG and MEG. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1998, 106, 522–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, A.F.; Bolger, D.J. The Neurophysiological Bases of EEG and EEG Measurement: A Review for the Rest of Us. Psychophysiology 2014, 51, 1061–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzsáki, G.; Anastassiou, C.A.; Koch, C. The Origin of Extracellular Fields and Currents — EEG, ECoG, LFP and Spikes. Nat Rev Neurosci 2012, 13, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, R.K.; Chaudhury, A. Structure Activity Relationship of Synaptic and Junctional Neurotransmission. Autonomic Neuroscience 2013, 176, 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, S.; Okada, Y. Contributions of Principal Neocortical Neurons to Magnetoencephalography and Electroencephalography Signals. J Physiol 2006, 575, 925–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunne, J. Workshops (WS) Workshop 1: Electroencephalogram (EEG) WS1.1. The Origin of EEG, Recording Techniques and Quality. Clinical Neurophysiology 2021, 132, e51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usakli, A.B. Improvement of EEG Signal Acquisition: An Electrical Aspect for State of the Art of Front End. Comput Intell Neurosci 2010, 2010, 630649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittingstall, K.; Stroink, G.; Gates, L.; Connolly, J.F.; Finley, A. Effects of Dipole Position, Orientation and Noise on the Accuracy of EEG Source Localization. Biomed Eng Online 2003, 2, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doschoris, M.; Kariotou, F. Mathematical Foundation of Electroencephalography. In Electroencephalography; InTech, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Næss, S.; Chintaluri, C.; Ness, T. V.; Dale, A.M.; Einevoll, G.T.; Wójcik, D.K. Corrected Four-Sphere Head Model for EEG Signals. Front Hum Neurosci 2017, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallez, H.; Vanrumste, B.; Grech, R.; Muscat, J.; De Clercq, W.; Vergult, A.; D’Asseler, Y.; Camilleri, K.P.; Fabri, S.G.; Van Huffel, S.; et al. Review on Solving the Forward Problem in EEG Source Analysis. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2007, 4, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grech, R.; Cassar, T.; Muscat, J.; Camilleri, K.P.; Fabri, S.G.; Zervakis, M.; Xanthopoulos, P.; Sakkalis, V.; Vanrumste, B. Review on Solving the Inverse Problem in EEG Source Analysis. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2008, 5, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acharya, J.N.; Hani, A.; Cheek, J.; Thirumala, P.; Tsuchida, T.N. American Clinical Neurophysiology Society Guideline 2: Guidelines for Standard Electrode Position Nomenclature. Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology 2016, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Homan, R.W.; Herman, J.; Purdy, P. Cerebral Location of International 10–20 System Electrode Placement. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1987, 66, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cascino, G.D. Current Practice of Clinical Electroencephalography. In Neurology, 2nd Ed. ed; 1991; Volume 41, p. 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klem, G.H.; Lüders, H.; Jasper, H.H.; Elger, C.E. The Ten-Twenty Electrode System of the International Federation. The International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol Suppl 1999, 52, 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Jurcak, V.; Tsuzuki, D.; Dan, I. 10/20, 10/10, and 10/5 Systems Revisited: Their Validity as Relative Head-Surface-Based Positioning Systems. Neuroimage 2007, 34, 1600–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, S.R.; Sullivan, L.; Sabau, D.; San-Juan, D.; Dombrowski, K.E.; Halford, J.J.; Hani, A.J.; Drislane, F.W.; Stecker, M.M. American Clinical Neurophysiology Society Guideline 1: Minimum Technical Requirements for Performing Clinical Electroencephalography. Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology 2016, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Guo, X. Application and Development of EEG Acquisition and Feedback Technology: A Review. Biosensors (Basel) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbabi, T.; Bouafif, L.; Cherif, A. A Review of Non Invasive Methods of Brain Activity Measurements via EEG Signals Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Advanced Systems and Emergent Technologies (IC_ASET) 2023; pp. 1–6.

- Knierim, M.T.; Bleichner, M.G.; Reali, P. A Systematic Comparison of High-End and Low-Cost EEG Amplifiers for Concealed, Around-the-Ear EEG Recordings. Sensors 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haneef, Z.; Yang, K.; Sheth, S.A.; Aloor, F.Z.; Aazhang, B.; Krishnan, V.; Karakas, C. Sub-Scalp Electroencephalography: A next-Generation Technique to Study Human Neurophysiology. Clinical Neurophysiology 2022, 141, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.K.; Mittal, S. Invasive Electroencephalography Monitoring: Indications and Presurgical Planning. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2014, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, L.; Ventrella, D.; Carnicer-Lombarte, A.; Elmi, A.; Troughton, J.G.; Mariello, M.; El Hadwe, S.; Woodington, B.J.; Bacci, M.L.; Malliaras, G.G.; et al. Origami-Inspired Soft Fluidic Actuation for Minimally Invasive Large-Area Electrocorticography. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 6290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, A.S.-M.S.; Menaker, S.A.; Chan, J.L.; Mamelak, A.N. Placement of Stereotactic Electroencephalography Depth Electrodes Using the Stealth Autoguide Robotic System: Technical Methods and Initial Results. Operative Neurosurgery 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Pei, W. Implantable Intracortical Microelectrodes: Reviewing the Present with a Focus on the Future. Microsyst Nanoeng 2023, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niso, G.; Romero, E.; Moreau, J.T.; Araujo, A.; Krol, L.R. Wireless EEG: A Survey of Systems and Studies. Neuroimage 2023, 269, 119774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Qian, W.; Razansky, D.; Yu, X.; Qian, C. WISDEM: A Hybrid Wireless Integrated Sensing Detector for Simultaneous EEG and MRI. Nat Methods 2025, 22, 1944–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casson, A.J. Wearable EEG and Beyond. Biomed Eng Lett 2019, 9, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhinav, V.; Basu, P.; Verma, S.S.; Verma, J.; Das, A.; Kumari, S.; Yadav, P.R.; Kumar, V. Advancements in Wearable and Implantable BioMEMS Devices: Transforming Healthcare Through Technology. Micromachines (Basel) 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samimisabet, P.; Krieger, L.; De Palol, M.V.; Gün, D.; Pipa, G. Enhancing Mobile EEG: Software Development and Performance Insights of the DreamMachine. HardwareX 2025, 23, e00689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, H.; Yang, Q.; Guo, C.; Zhu, S.; Shu, X. State of the Art of Non-Invasive Electrode Materials for Brain–Computer Interface. Micromachines (Basel) 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Xue, H.; Xia, L.; Li, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Fan, X.; Sun, K.; Wang, H.; Hamalainen, T.; Zhang, C.; et al. A Tough Semi-Dry Hydrogel Electrode with Anti-Bacterial Properties for Long-Term Repeatable Non-Invasive EEG Acquisition. Microsyst Nanoeng 2025, 11, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, F.; Fan, M.; Feng, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, C.; Zheng, J.; Wang, C.; Zhou, J. Advancements in Dry and Semi-Dry EEG Electrodes: Design, Interface Characteristics, and Performance Evaluation. AIP Adv 2025, 15, 040703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Gordo, M.A.; Sanchez-Morillo, D.; Valle, F.P. Dry EEG Electrodes. Sensors 2014, 14, 12847–12870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, A.; Kirkup, L. A Direct Comparison of Wet, Dry and Insulating Bioelectric Recording. Physiol Meas 2000, 21, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Xu, X.; Huang, S.; Huang, X.; Liu, Z.; Yao, C.; He, M.; Chen, J.; Chen, H.; Liu, J.; et al. Multichannel Microneedle Dry Electrode Patches for Minimally Invasive Transdermal Recording of Electrophysiological Signals. Microsyst Nanoeng 2024, 10, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, H.; Ntolkeras, G.; Warbrick, T.; Jaschke, M.; Gupta, R.; Lev, M.H.; Peters, J.M.; Grant, P.E.; Bonmassar, G. Aluminum Thin Film Nanostructure Traces in Pediatric EEG Net for MRI and CT Artifact Reduction. Sensors 2023, 23, 3633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, S.; Kullmann, A.; Mertens, S.; Rosa, D.; Diaz-Botia, C.A. Electrochemical Testing of a New Polyimide Thin Film Electrode for Stimulation, Recording, and Monitoring of Brain Activity. Micromachines (Basel) 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Euler, L.; Guo, L.; Persson, N.-K. Textile Electrodes: Influence of Knitting Construction and Pressure on the Contact Impedance. Sensors 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyseowicz, A.; Minta, D.; Gryglewicz, G. Conductive Polymer/Graphene-Based Composites for Next Generation Energy Storage and Sensing Applications. ChemElectroChem 2023, 10, e202201145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oostenveld, R.; Praamstra, P. The Five Percent Electrode System for High-Resolution EEG and ERP Measurements. Clinical Neurophysiology 2001, 112, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, A.; Moctezuma, L.A.; Giraldo, E.; Molinas, M. Automated Methodology for Optimal Selection of Minimum Electrode Subsets for Accurate EEG Source Estimation Based on Genetic Algorithm Optimization. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 11221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, G.; Pei, W.; Tian, S.; Chen, X.; Gao, X.; Wang, Y. High-Density EEG Enables the Fastest Visual Brain-Computer Interfaces. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Teplan, M. FUNDAMENTALS OF EEG MEASUREMENT. Measurement Science Review 2002, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, Y.M.; Cauwenberghs, G. Wireless Non-Contact EEG/ECG Electrodes for Body Sensor Networks. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Body Sensor Networks 2010; pp. 297–301.

- Vanhatalo, S.; Palva, J.M.; Andersson, S.; Rivera, C.; Voipio, J.; Kaila, K. Slow Endogenous Activity Transients and Developmental Expression of K+–Cl− Cotransporter 2 in the Immature Human Cortex. European Journal of Neuroscience 2005, 22, 2799–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, T.; Kothe, C.; Chi, Y.M.; Ojeda, A.; Kerth, T.; Makeig, S.; Cauwenberghs, G. Tzyy-Ping Jung Real-Time Modeling and 3D Visualization of Source Dynamics and Connectivity Using Wearable EEG. In Proceedings of the 2013 35th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), IEEE, July 2013; pp. 2184–2187.

- Pernet, C.R.; Appelhoff, S.; Gorgolewski, K.J.; Flandin, G.; Phillips, C.; Delorme, A.; Oostenveld, R. EEG-BIDS, an Extension to the Brain Imaging Data Structure for Electroencephalography. Sci Data 2019, 6, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleury, M.; Figueiredo, P.; Vourvopoulos, A.; Lécuyer, A. Two Is Better? Combining EEG and FMRI for BCI and Neurofeedback: A Systematic Review. J Neural Eng 2023, 20, 051003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yu, K.; Bi, Y.; Ji, X.; Zhang, D. Strategic Integration: A Cross-Disciplinary Review of the FNIRS-EEG Dual-Modality Imaging System for Delivering Multimodal Neuroimaging to Applications. Brain Sci 2024, 14, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adnan Khan, M.D.S.; Hoq, Md.T.; Zadidul Karim, A.H.M.; Alam, Md.K.; Howlader, M.; Rajkumar, R.K. Energy Harvesting—Technical Analysis of Evolution, Control Strategies, and Future Aspectsa. Journal of Electronic Science and Technology 2019, 17, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BAVEL, M.; Leonov, V.; Yazicioglu, R.; Torfs, T.; Van Hoof, C.; Posthuma, N.; Vullers, R. Wearable Battery-Free Wireless 2-Channel EEG Systems Powered by Energy Scavengers. Sensors and Transducers 2008, 94, 103–115. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary, S.K.; Bera, T.K. Designing of Battery-Based Low Noise Electroencephalography (EEG) Amplifier for Brain Signal Monitoring: A Simulation Study. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 6th International Conference on Condition Assessment Techniques in Electrical Systems (CATCON), IEEE, December 17 2022; pp. 422–426.

- Soufineyestani, M.; Dowling, D.; Khan, A. Electroencephalography (EEG) Technology Applications and Available Devices. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 7453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Värbu, K.; Muhammad, N.; Muhammad, Y. Past, Present, and Future of EEG-Based BCI Applications. Sensors 2022, 22, 3331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, N.S.; Belhaouari, S.B. EEG Signal Processing for Medical Diagnosis, Healthcare, and Monitoring: A Comprehensive Review. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 143116–143142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Salinas, J.S.; Wróblewska, A.; Kucewicz, M.T. Detection of EEG Activity in Response to the Surrounding Environment: A Neuro-Architecture Study. Brain Sci 2025, 15, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Li, M.D. Digital Psychiatry: Concepts, Framework, and Implications. Front Psychiatry 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkowski, J.; Saab, M. AI-Based EEG Analysis: New Technology and the Path to Clinical Adoption. Clinical Neurophysiology 2025, 179, 2110994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Karwowski, W.; Fafrowicz, M.; Hancock, P.A. Neuroergonomics Applications of Electroencephalography in Physical Activities: A Systematic Review. Front Hum Neurosci 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khondakar, Md.F.K.; Sarowar, Md.H.; Chowdhury, M.H.; Majumder, S.; Hossain, Md.A.; Dewan, M.A.A.; Hossain, Q.D. A Systematic Review on EEG-Based Neuromarketing: Recent Trends and Analyzing Techniques. Brain Inform 2024, 11, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.-C.; Kuo, P.-C. Adaptive Learning System for E-Learning Based on EEG Brain Signals. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 6th Global Conference on Consumer Electronics (GCCE), IEEE, October 2017; pp. 1–2.

- Cheng, M.-Y.; Yu, C.-L.; An, X.; Wang, L.; Tsai, C.-L.; Qi, F.; Wang, K.-P. Evaluating EEG Neurofeedback in Sport Psychology: A Systematic Review of RCT Studies for Insights into Mechanisms and Performance Improvement. Front Psychol 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatar, A.B. Biometric Identification System Using EEG Signals. Neural Comput Appl 2023, 35, 1009–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre Cordeau, J. Monorhythmic Frontal Delta Activity in the Human Electroencephalogram: A Study of 100 Cases. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1959, 11, 733–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harmony, T.; Fernández, T.; Silva, J.; Bernal, J.; Díaz-Comas, L.; Reyes, A.; Marosi, E.; Rodríguez, M.; Rodríguez, M. EEG Delta Activity: An Indicator of Attention to Internal Processing during Performance of Mental Tasks. International Journal of Psychophysiology 1996, 24, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.D.; Arduini, A.A. HIPPOCAMPAL ELECTRICAL ACTIVITY IN AROUSAL. J Neurophysiol 1954, 17, 533–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snipes, S.; Krugliakova, E.; Meier, E.; Huber, R. The Theta Paradox: 4-8 Hz EEG Oscillations Reflect Both Sleep Pressure and Cognitive Control. The Journal of Neuroscience 2022, 42, 8569–8586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aird, R.B.; Gastaut, Y. Occipital and Posterior Electroencephalographic Ryhthms. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1959, 11, 637–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klimesch, W. Alpha-Band Oscillations, Attention, and Controlled Access to Stored Information. Trends Cogn Sci 2012, 16, 606–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, J.D.; Carrie, J.R.G.; Borda, R.P.; Kellaway, P. The Effects of Dalmane (Flurazepam Hydrochloride) on Human EEG Characteristics. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1973, 34, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.J.; Cohen, L.G.; Bönstrup, M. Beta Rhythm Events Predict Corticospinal Motor Output. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 18305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Kohn, A. Gamma Rhythms in the Brain. PLoS Biol 2011, 9, e1001045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satapathy, S.K.; Dehuri, S.; Jagadev, A.K.; Mishra, S. Introduction. In EEG Brain Signal Classification for Epileptic Seizure Disorder Detection; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Urrestarazu, E.; Jirsch, J.D.; LeVan, P.; Hall, J. High-Frequency Intracerebral EEG Activity (100–500 Hz) Following Interictal Spikes. Epilepsia 2006, 47, 1465–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.; Maunsell, J.H.R. Different Origins of Gamma Rhythm and High-Gamma Activity in Macaque Visual Cortex. PLoS Biol 2011, 9, e1000610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchins, T.; Vivanti, G.; Mateljevic, N.; Jou, R.J.; Shic, F.; Cornew, L.; Roberts, T.P.L.; Oakes, L.; Gray, S.A.O.; Ray-Subramanian, C.; et al. Mu Rhythm. In Encyclopedia of Autism Spectrum Disorders; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2013; pp. 1940–1941. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, L.M.J.; Lüthi, A. Sleep Spindles: Mechanisms and Functions. Physiol Rev 2020, 100, 805–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cash, S.S.; Halgren, E.; Dehghani, N.; Rossetti, A.O.; Thesen, T.; Wang, C.; Devinsky, O.; Kuzniecky, R.; Doyle, W.; Madsen, J.R.; et al. The Human K-Complex Represents an Isolated Cortical Down-State. Science (1979) 2009, 324, 1084–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Rosa, A.C.; Kemp, B.; Paiva, T.; Lopes da Silva, F.H.; Kamphuisen, H.A.C. A Model-Based Detector of Vertex Waves and K Complexes in Sleep Electroencephalogram. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1991, 78, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gélisse, P.; Crespel, A. Powerful Activation of Lambda Waves with Inversion of Polarity by Reading on Tablet. Epileptic Disorders 2024, 26, 254–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich, F. Epilepsy. In Network Neuroscience; Elsevier, 2016; pp. 297–308. [Google Scholar]

- Siebert, W.M.C. Processing Neuroelectric Data; Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Research Laboratory of Electronics. Technical report 351; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Lilliefors, H.W. On the Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test for Normality with Mean and Variance Unknown. J Am Stat Assoc 1967, 62, 399–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, J. Comments on Estimations and Tests of EEG Amplitude Distributions. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1974, 37, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldensohn, E.S. Handbook of Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. Neurology 1975, 25, 299–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjorth, B. EEG Analysis Based on Time Domain Properties. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1970, 29, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, P.; Kleiner, B.; Gasser, T.; Dumermuth, G. Statistical Methods for Investigating Phase Relations in Stationary Stochastic Processes. IEEE Transactions on Audio and Electroacoustics 1971, 19, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumermuth, G.; Huber, P.J.; Kleiner, B.; Gasser, T. Analysis of the Interrelations between Frequency Bands of the EEG by Means of the Bispectrum a Preliminary Study. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1971, 31, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saltzberg, B.; Burch, N.R. Period Analytic Estimates of Moments of the Power Spectrum: A Simplified EEG Time Domain Procedure. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1971, 30, 568–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendling, F.; Congendo, M.; Lopes da Silva, F.H. EEG Analysis: Theory and Practice; Schomer, D.L., Lopes da Silva, F.H., Eds.; Oxford University Press, 2017; Vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Rasoulzadeh, V.; Erkus, E.C.; Yogurt, T.A.; Ulusoy, I.; Zergeroğlu, S.A. A Comparative Stationarity Analysis of EEG Signals. Ann Oper Res 2017, 258, 133–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlattmann, P. An Introduction to Statistical Concepts for the Analysis of EEG Data and the Planning of Pharmaco-EEG Trials. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol 2002, 24 Suppl C, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Matousˇek, M.; Volavka, J.; Roubícˇek, J.; Chamrád, V. The Autocorrelation and Frequency Analysis of the EEG Compared with GSR at Different Levels of Activation. Brain Res 1969, 15, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Drongelen, W.; Nordli, D.R.; Taha, M. Approaches for Interchannel EEG Analysis. medRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, Q.-Q.; Chen, H.; Hu, X.-Q.; Li, W.-G.; Bai, Y.; Han, J.-X.; Wang, Y.; Liang, Z.-H.; Chen, D.; et al. The Applied Principles of EEG Analysis Methods in Neuroscience and Clinical Neurology. Mil Med Res 2023, 10, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, N.R. Period Analysis of the Clinical Electroencephalogram. In The Nervous System and Electric Currents; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1971; pp. 55–56. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Stoica, P. Spectral Analysis of Signals; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2005; ISBN 978-3-031-01397-3. [Google Scholar]

- EEG Signal Processing and Feature Extraction; Hu, L., Zhang, Z., Eds.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2019; ISBN 978-981-13-9112-5. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Fahoum, A.S.; Al-Fraihat, A.A. Methods of EEG Signal Features Extraction Using Linear Analysis in Frequency and Time-Frequency Domains. ISRN Neurosci 2014, 2014, 730218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabidi, A.; Mansor, W.; Lee, Y.K.; Che Wan Fadzal, C.W.N.F. Short-Time Fourier Transform Analysis of EEG Signal Generated during Imagined Writing. In Proceedings of the 2012 International Conference on System Engineering and Technology (ICSET), IEEE, September 2012; pp. 1–4.

- Díaz López, J.M.; Curetti, J.; Meinardi, V.B.; Farjreldines, H.D.; Boyallian, C. FFT Power Relationships Applied to EEG Signal Analysis: A Meeting between Visual Analysis of EEG and Its Quantification. medRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.H.; Uddin, M.B. Detection of Sleep Arousal from STFT-Based Instantaneous Features of Single Channel EEG Signal. Physiol Meas 2024, 45, 105005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lew, R.; Dyre, B.P.; Werner, S.; Wotring, B.; Tran, T. Exploring the Potential of Short-Time Fourier Transforms for Analyzing Skin Conductance and Pupillometry in Real-Time Applications. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting 2008, 52, 1536–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; G, G.; Anand, R.S. Epileptic Seizure Detection Using STFT Based Peak Mean Feature and Support Vector Machine. In Proceedings of the 2021 8th International Conference on Signal Processing and Integrated Networks (SPIN), IEEE, August 26 2021; pp. 1131–1136.

- CADZOW, J.A. Spectral Analysis. In Handbook of Digital Signal Processing; Elsevier, 1987; pp. 701–740. [Google Scholar]

- Akin, M.; Kiymik, M.K. Application of Periodogram and AR Spectral Analysis to EEG Signals. J Med Syst 2000, 24, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, P. The Use of Fast Fourier Transform for the Estimation of Power Spectra: A Method Based on Time Averaging over Short, Modified Periodograms. IEEE Transactions on Audio and Electroacoustics 1967, 15, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babadi, B.; Brown, E.N. A Review of Multitaper Spectral Analysis. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2014, 61, 1555–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, L. Brief Historical Introduction to Wavelet Transforms. Int J Math Educ Sci Technol 1998, 29, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrence, C.; Compo, G.P. A Practical Guide to Wavelet Analysis. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 1998, 79, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, N. Wavelets for EEG Analysis. In Wavelet Theory; IntechOpen, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gokhale, M.Y.; Khanduja, D.K. Time Domain Signal Analysis Using Wavelet Packet Decomposition Approach. International Journal of Communications, Network and System Sciences 2010, 03, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosala, B.; Dindayal Kapgate, P.; Jain, P.; Nath Chaurasia, R.; Gupta, M. Wavelet Transforms for Feature Engineering in EEG Data Processing: An Application on Schizophrenia. Biomed Signal Process Control 2023, 85, 104811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyasseri, Z.A.A.; Khader, A.T.; Al-Betar, M.A.; Abasi, A.K.; Makhadmeh, S.N. EEG Signals Denoising Using Optimal Wavelet Transform Hybridized With Efficient Metaheuristic Methods. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 10584–10605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbina Fredes, S.; Dehghan Firoozabadi, A.; Adasme, P.; Zabala-Blanco, D.; Palacios Játiva, P.; Azurdia-Meza, C. Enhanced Epileptic Seizure Detection through Wavelet-Based Analysis of EEG Signal Processing. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 5783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, H.U.; Ullah, R.; Reza, M.F.; Malik, A.S. Single-Trial Extraction of Event-Related Potentials (ERPs) and Classification of Visual Stimuli by Ensemble Use of Discrete Wavelet Transform with Huffman Coding and Machine Learning Techniques. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2023, 20, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Cao, H.; Wang, S.; Chen, X. Time-Reassigned Synchrosqueezing Transform: The Algorithm and Its Applications in Mechanical Signal Processing. Mech Syst Signal Process 2019, 117, 255–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cura, O.K.; Akan, A. Classification of Epileptic EEG Signals Using Synchrosqueezing Transform and Machine Learning. Int J Neural Syst 2021, 31, 2150005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degirmenci, D.; Yalcin, M.; Ozdemir, M.A.; Akan, A. Synchrosqueezing Transform in Biomedical Applications: A Mini Review. In Proceedings of the 2020 Medical Technologies Congress (TIPTEKNO), IEEE, November 19 2020; pp. 1–5.

- Stockwell, R.G.; Mansinha, L.; Lowe, R.P. Localization of the Complex Spectrum: The S Transform. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 1996, 44, 998–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attoh-Okine, N.O.; Huang, N.E. The Hilbert-Huang Transform in Engineering; Taylor & Francis, 2005; ISBN 9780849334221. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Ying, Q.; Luo, Z.; Fan, Y. Analysis and Research on EEG Signals Based on HHT Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2016 Sixth International Conference on Instrumentation & Measurement, Computer, Communication and Control (IMCCC), IEEE, July 2016; pp. 563–566.

- Slivinskas, V.; Šimonyte, V. On the Foundation of Prony’s Method. IFAC Proceedings Volumes 1986, 19, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauer, J.F.; Demeure, C.J.; Scharf, L.L. Initial Results in Prony Analysis of Power System Response Signals. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 1990, 5, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maris, E. A Resampling Method for Estimating the Signal Subspace of Spatio-Temporal Eeg/Meg Data. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2003, 50, 935–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, P.A.; Whittle, P. Hypothesis Testing in Time Series Analysis. J R Stat Soc Ser A 1951, 114, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippmann, R.P. Pattern Classification Using Neural Networks. IEEE Communications Magazine 1989, 27, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Box, G.E.P.; Pierce, D.A. Distribution of Residual Autocorrelations in Autoregressive-Integrated Moving Average Time Series Models. J Am Stat Assoc 1970, 65, 1509–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, D.J.; Box, G.E.P.; Jenkins, G.M. Time Series Analysis Forecasting and Control. Operational Research Quarterly (1970-1977) 1971, 22, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, S.M.; Frei, M.G.; Osorio, I.; Pasik-Duncan, B.; Radel, J. EEG Ocular Artifact Removal through ARMAX Model System Identification Using Extended Least Squares. Commun Inf Syst 2003, 3, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wairagkar, M.; Hayashi, Y.; Nasuto, S.J. Modeling the Ongoing Dynamics of Short and Long-Range Temporal Correlations in Broadband EEG During Movement. Front Syst Neurosci 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera, R.E.; Sun, M.; Dahl, R.E.; Ryan, N.D.; Sclabassi, R.J. Vector Autoregressive Model Selection in Multichannel EEG. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 19th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. “Magnificent Milestones and Emerging Opportunities in Medical Engineering” (Cat. No.97CH36136); IEEE; pp. 1211–1214.

- Endemann, C.M.; Krause, B.M.; Nourski, K. V.; Banks, M.I.; Veen, B. Van Multivariate Autoregressive Model Estimation for High-Dimensional Intracranial Electrophysiological Data. Neuroimage 2022, 254, 119057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettiarachchi, I.T.; Mohamed, S.; Nyhof, L.; Nahavandi, S. An Extended Multivariate Autoregressive Framework for EEG-Based Information Flow Analysis of a Brain Network. In Proceedings of the 2013 35th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), IEEE, July 2013; pp. 3945–3948.

- Bressler, S.L.; Kumar, A.; Singer, I. Brain Synchronization and Multivariate Autoregressive (MVAR) Modeling in Cognitive Neurodynamics. Front Syst Neurosci 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follis, J.L.; Lai, D. Modeling Volatility Characteristics of Epileptic EEGs Using GARCH Models. Signals 2020, 1, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Nyholt, D.R. Marker Selection by Akaike Information Criterion and Bayesian Information Criterion. Genet Epidemiol 2001, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wang, X.; Li, F.; Zhang, R.; Ma, T.; Peng, Y.; Lei, X.; Tian, Y.; Guo, D.; Liu, T.; et al. Autoregressive Model in the Lp Norm Space for EEG Analysis. J Neurosci Methods 2015, 240, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, M.U.; Rashad, A.; Basalamah, A.; Tariq, M. Detection of Epilepsy Seizures in Neo-Natal EEG Using LSTM Architecture. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 179074–179085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabioun, M. Autistic Recognition from EEG Signals by Extracted Features from Several Time Series Models. preprint Research Square 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghsoudi, R.; White, C.D. Real-Time Identification of Parameters of the ARMA Model of the Human EEG Waveforms. Biomed Sci Instrum 1993, 29, 191–198. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, S.M. Bayesian Statistics. In Encyclopedia of Social Measurement; Elsevier, 2005; pp. 135–144. [Google Scholar]

- Dimmock, S.; O’Donnell, C.; Houghton, C. Bayesian Analysis of Phase Data in EEG and MEG. Elife 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.E.; Dutt, D.N. An Expectation-Maximization Algorithm Based Kalman Smoother Approach for Event-Related Desynchronization (ERD) Estimation from EEG. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2007, 54, 1191–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezugwu, A.E.; Ikotun, A.M.; Oyelade, O.O.; Abualigah, L.; Agushaka, J.O.; Eke, C.I.; Akinyelu, A.A. A Comprehensive Survey of Clustering Algorithms: State-of-the-Art Machine Learning Applications, Taxonomy, Challenges, and Future Research Prospects. Eng Appl Artif Intell 2022, 110, 104743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, M.; Ferreira, P.G. Hidden Markov Models. In Bioinformatics Algorithms; Elsevier, 2018; pp. 255–273. [Google Scholar]

- Palma, G.R.; Thornberry, C.; Commins, S.; Moral, R. de A. Understanding Learning from EEG Data: Combining Machine Learning and Feature Engineering Based on Hidden Markov Models and Mixed Models. Neuroinformatics 2023, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Friston, K.J.; Harrison, L.; Penny, W. Dynamic Causal Modelling. Neuroimage 2003, 19, 1273–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiebel, S.J.; Garrido, M.I.; Moran, R.J.; Friston, K.J. Dynamic Causal Modelling for EEG and MEG. Cogn Neurodyn 2008, 2, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makeig, S.; Jung, T.-P.; Bell, A.J.; Sejnowski, T.J. Independent Component Analysis of Electroencephalographic Data. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 8 (NIPS 1995) 1995.

- Moosmann, M.; Eichele, T.; Nordby, H.; Hugdahl, K.; Calhoun, V.D. Joint Independent Component Analysis for Simultaneous EEG–FMRI: Principle and Simulation. International Journal of Psychophysiology 2008, 67, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z. Independent Vector Analysis: Model, Applications, Challenges. Pattern Recognit 2023, 138, 109376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, C.P.A.; Aristimunha, B.; Dos Santos, L.H.; Pinaya, W.H.L.; de Camargo, R.Y.; Fantinato, D.G.; Neves, A. Applying Independent Vector Analysis on EEG-Based Motor Imagery Classification. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2023 - 2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), IEEE, June 4 2023; pp. 1–5.

- Subasi, A.; Ismail Gursoy, M. EEG Signal Classification Using PCA, ICA, LDA and Support Vector Machines. Expert Syst Appl 2010, 37, 8659–8666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillis, N. The Why and How of Nonnegative Matrix Factorization. ArXiv 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, G.; Zhou, T.; Luo, S.; Mahini, R.; Xu, J.; Chang, Y.; Cong, F. Assessment of Nonnegative Matrix Factorization Algorithms for Electroencephalography Spectral Analysis. Biomed Eng Online 2020, 19, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Wang, S.; Rosenberger, J.; Su, J.; Liu, H. A Sparse Dictionary Learning Framework to Discover Discriminative Source Activations in EEG Brain Mapping. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2017; 31. [CrossRef]

- Barthélemy, Q.; Gouy-Pailler, C.; Isaac, Y.; Souloumiac, A.; Larue, A.; Mars, J.I. Multivariate Temporal Dictionary Learning for EEG. Computational Neuroscience 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OK, F.; Rajesh, R. Empirical Mode Decomposition of EEG Signals for the Effectual Classification of Seizures. In Advances in Neural Signal Processing; IntechOpen, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ShahbazPanahi, S.; Jing, Y. Recent Advances in Network Beamforming. In Academic Press Library in Signal Processing; Elsevier, 2018; Volume 7, pp. 403–477. [Google Scholar]

- Westner, B.U.; Dalal, S.S.; Gramfort, A.; Litvak, V.; Mosher, J.C.; Oostenveld, R.; Schoffelen, J.-M. A Unified View on Beamformers for M/EEG Source Reconstruction. Neuroimage 2022, 246, 118789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauk, O. Keep It Simple: A Case for Using Classical Minimum Norm Estimation in the Analysis of EEG and MEG Data. Neuroimage 2004, 21, 1612–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dattola, S.; Morabito, F.C.; Mammone, N.; La Foresta, F. Findings about LORETA Applied to High-Density EEG—A Review. Electronics (Basel) 2020, 9, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastola, S.; Jahromi, S.; Chikara, R.; Stufflebeam, S.M.; Ottensmeyer, M.P.; De Novi, G.; Papadelis, C.; Alexandrakis, G. Improved Dipole Source Localization from Simultaneous MEG-EEG Data by Combining a Global Optimization Algorithm with a Local Parameter Search: A Brain Phantom Study. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeramalla, S.K.; Talari, V.K.H.R. Multiple Dipole Source Localization of EEG Measurements Using Particle Filter with Partial Stratified Resampling. Biomed Eng Lett 2020, 10, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara, M.A.; Corsi-Cabrera, M. EEG Coherence or EEG Correlation? International Journal of Psychophysiology 1996, 23, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Shin, Y.; Sunwoo, J.-S.; Son, H.; Lee, S.-B.; Chu, K.; Jung, K.-Y.; Lee, S.K.; Kim, Y.-G.; Park, K.-I. Increased Coherence Predicts Medical Refractoriness in Patients with Temporal Lobe Epilepsy on Monotherapy. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 20530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awais, M.A.; Yusoff, M.Z.; Khan, D.M.; Yahya, N.; Kamel, N.; Ebrahim, M. Effective Connectivity for Decoding Electroencephalographic Motor Imagery Using a Probabilistic Neural Network. Sensors 2021, 21, 6570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursino, M.; Ricci, G.; Magosso, E. Transfer Entropy as a Measure of Brain Connectivity: A Critical Analysis With the Help of Neural Mass Models. Front Comput Neurosci 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, S.H.; Jin, S.-H.; Kim, S.Y.; Ham, B.-J. EEG in Schizophrenic Patients: Mutual Information Analysis. Clinical Neurophysiology 2002, 113, 1954–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baselice, F.; Sorriso, A.; Rucco, R.; Sorrentino, P. Phase Linearity Measurement: A Novel Index for Brain Functional Connectivity. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2019, 38, 873–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfrich, R.F.; Herrmann, C.S.; Engel, A.K.; Schneider, T.R. Different Coupling Modes Mediate Cortical Cross-Frequency Interactions. Neuroimage 2016, 140, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, J.; Zheng, S.; Lei, C.; Peng, H.; Hu, B. Exploratory Cross-Frequency Coupling and Scaling Analysis of Neuronal Oscillations Stimulated by Emotional Images: An Evidence From EEG. IEEE Trans Cogn Dev Syst 2023, 15, 1732–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haan, W.; AL Pijnenburg, Y.; Strijers, R.L.; van der Made, Y.; van der Flier, W.M.; Scheltens, P.; Stam, C.J. Functional Neural Network Analysis in Frontotemporal Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease Using EEG and Graph Theory. BMC Neurosci 2009, 10, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagnotta, M.F.; Plomp, G. Time-Varying MVAR Algorithms for Directed Connectivity Analysis: Critical Comparison in Simulations and Benchmark EEG Data. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0198846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiebel, S.J.; Garrido, M.I.; Moran, R.J.; Friston, K.J. Dynamic Causal Modelling for EEG and MEG. Cogn Neurodyn 2008, 2, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawano, T.; Hattori, N.; Uno, Y.; Kitajo, K.; Hatakenaka, M.; Yagura, H.; Fujimoto, H.; Yoshioka, T.; Nagasako, M.; Otomune, H.; et al. Large-Scale Phase Synchrony Reflects Clinical Status After Stroke: An EEG Study. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2017, 31, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pritchard, W. s.; Duke, D. w. Measuring Chaos in the Brain: A Tutorial Review of Nonlinear Dynamical Eeg Analysis. International Journal of Neuroscience 1992, 67, 31–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradhan, N.; Narayana Dutt, D. A Nonlinear Perspective in Understanding the Neurodynamics of EEG. Comput Biol Med 1993, 23, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, L.; Taylor, P.; Bellenger, C.; Grimshaw, P.; Crowther, R.G. The Application of the Lyapunov Exponent to Analyse Human Performance: A Systematic Review. J Sports Sci 2023, 41, 1994–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affinito, M.; Carrozzi, M.; Accardo, A.; Bouquet, F. Use of the Fractal Dimension for the Analysis of Electroencephalographic Time Series. Biol Cybern 1997, 77, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereda, E.; Gamundi, A.; Rial, R.; González, J. Non-Linear Behaviour of Human EEG: Fractal Exponent versus Correlation Dimension in Awake and Sleep Stages. Neurosci Lett 1998, 250, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, Z.J.; Pham, T.; Chen, S.H.A.; Makowski, D. Brain Entropy, Fractal Dimensions and Predictability: A Review of Complexity Measures for EEG in Healthy and Neuropsychiatric Populations. European Journal of Neuroscience 2022, 56, 5047–5069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kannathal, N.; Choo, M.L.; Acharya, U.R.; Sadasivan, P.K. Entropies for Detection of Epilepsy in EEG. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2005, 80, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, X.; Potter, T.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y. Single-Trial EEG Emotion Recognition Using Granger Causality/Transfer Entropy Analysis. J Neurosci Methods 2020, 346, 108904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aftanas, L.I.; Lotova, N. V; Koshkarov, V.I.; Pokrovskaja, V.L.; Popov, S.A.; Makhnev, V.P. Non-Linear Analysis of Emotion EEG: Calculation of Kolmogorov Entropy and the Principal Lyapunov Exponent. Neurosci Lett 1997, 226, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, S.; Zhou, W.; Yuan, Q.; Cai, D.; Zeng, Y. EEG Non-Linear Feature Extraction Using Correlation Dimension and Hurst Exponent. Neurol Res 2011, 33, 908–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahmiri, S. Generalized Hurst Exponent Estimates Differentiate EEG Signals of Healthy and Epileptic Patients. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2018, 490, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niknazar, M.; Mousavi, S.R.; Vosoughi Vahdat, B.; Sayyah, M. A New Framework Based on Recurrence Quantification Analysis for Epileptic Seizure Detection. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform 2013, 17, 572–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabani, H.; Mikaili, M.; Noori, S.M.R. Assessment of Recurrence Quantification Analysis (RQA) of EEG for Development of a Novel Drowsiness Detection System. Biomed Eng Lett 2016, 6, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaat, M.; Awadalla, M.; Abdel-Hamid, L. Recurrence Quantification Analysis (RQA) Features vs. Traditional EEG Features for Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnosis. Inteligencia Artificial 2025, 28, 170–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Mou, C. Survey on the Research Direction of EEG-Based Signal Processing. Front Neurosci 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, M.; Karwowski, W.; Farahani, F. V; Fiok, K.; Taiar, R.; Hancock, P.A.; Al-Juaid, A. Neural Decoding of EEG Signals with Machine Learning: A Systematic Review. Brain Sci 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Raja, R.; Srivastava, S.; Sharma, P.C.; Gangrade, J.; R, M. Analysis of EEG Signals and Data Acquisition Methods: A Review. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Eng Imaging Vis 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M.-P.; Hosseini, A.; Ahi, K. A Review on Machine Learning for EEG Signal Processing in Bioengineering. IEEE Rev Biomed Eng 2021, 14, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Näher, T.; Bastian, L.; Vorreuther, A.; Fries, P.; Goebel, R.; Sorger, B. Riemannian Geometry Boosts Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy-Based Brain-State Classification Accuracy. Neurophotonics 2025, 12, 045002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wosiak, A.; Tereszczuk, A.; Żykwińska, K. Determining Levels of Affective States with Riemannian Geometry Applied to EEG Signals. Applied Sciences 2025, 15, 10370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mashhadani, Z.; Bayat, N.; Kadhim, I.F.; Choudhury, R.; Park, J.-H. The Efficacy and Utility of Lower-Dimensional Riemannian Geometry for EEG-Based Emotion Classification. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 8274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibermacine, I.E.; Russo, S.; Tibermacine, A.; Rabehi, A.; Nail, B.; Kadri, K.; Napoli, C. Riemannian Geometry-Based EEG Approaches: A Literature Review. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo, F.; Zhang, X.; Tang, F.; Yu, Y.; Liu, L. Riemannian Transfer Learning Based on Log-Euclidean Metric for EEG Classification. Front Neurosci 2024, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleuzé, A.; Mattout, J.; Congedo, M. Tangent Space Alignment: Transfer Learning for Brain-Computer Interface. Front Hum Neurosci 2022, 16, 1049985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawhern, V.J.; Solon, A.J.; Waytowich, N.R.; Gordon, S.M.; Hung, C.P.; Lance, B.J. EEGNet: A Compact Convolutional Network for EEG-Based Brain-Computer Interfaces. J Neural Eng 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirrmeister, R.T.; Springenberg, J.T.; Fiederer, L.D.J.; Glasstetter, M.; Eggensperger, K.; Tangermann, M.; Hutter, F.; Burgard, W.; Ball, T. Deep Learning with Convolutional Neural Networks for EEG Decoding and Visualization. Hum Brain Mapp 2017, 38, 5391–5420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, Md.R.; Massicotte, D.; Nougarou, F.; Massicotte, P.; Zhu, W.-P. S-Convnet: A Shallow Convolutional Neural Network Architecture for Neuromuscular Activity Recognition Using Instantaneous High-Density Surface EMG Images. In Proceedings of the 2020 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), IEEE, July 2020; pp. 744–749.

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, G.; You, F.; Kuang, S.; Sun, L. A Multi-Branch 3D Convolutional Neural Network for EEG-Based Motor Imagery Classification. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2019, 27, 2164–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craik, A.; He, Y.; Contreras-Vidal, J.L. Deep Learning for Electroencephalogram (EEG) Classification Tasks: A Review. J Neural Eng 2019, 16, 031001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schirrmeister, R.T.; Springenberg, J.T.; Fiederer, L.D.J.; Glasstetter, M.; Eggensperger, K.; Tangermann, M.; Hutter, F.; Burgard, W.; Ball, T. Deep Learning with Convolutional Neural Networks for EEG Decoding and Visualization. Hum Brain Mapp 2017, 38, 5391–5420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altaheri, H.; Muhammad, G.; Alsulaiman, M.; Amin, S.U.; Altuwaijri, G.A.; Abdul, W.; Bencherif, M.A.; Faisal, M. Deep Learning Techniques for Classification of Electroencephalogram (EEG) Motor Imagery (MI) Signals: A Review. Neural Comput Appl 2023, 35, 14681–14722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, Y.; Banville, H.; Albuquerque, I.; Gramfort, A.; Falk, T.H.; Faubert, J. Deep Learning-Based Electroencephalography Analysis: A Systematic Review. J Neural Eng 2019, 16, 051001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.R.; Ding, Y.; Sen, S. SSL-SE-EEG: A Framework for Robust Learning from Unlabeled EEG Data with Self-Supervised Learning and Squeeze-Excitation Networks. 47th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC 2025) 2025.

- Klepl, D.; Wu, M.; He, F. Graph Neural Network-Based EEG Classification: A Survey. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng 2024, 32, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klepl, D.; Wu, M.; He, F. Graph Neural Network-Based EEG Classification: A Survey. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2023.

- Zhang, Y.; Liao, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhang, X.; Huang, L. Emotion Recognition of EEG Signals Based on Contrastive Learning Graph Convolutional Model. J Neural Eng 2024, 21, 046060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrani, G.; Adadi, A.; Berrada, M.; Souirti, Z.; Boujraf, S. EEG Signal Analysis Using Deep Learning: A Systematic Literature Review. In Proceedings of the 2021 Fifth International Conference On Intelligent Computing in Data Sciences (ICDS), IEEE, October 20 2021; pp. 1–8.

- Ye, W.; Zhang, Z.; Teng, F.; Zhang, M.; Wang, J.; Ni, D.; Li, F.; Xu, P.; Liang, Z. Semi-Supervised Dual-Stream Self-Attentive Adversarial Graph Contrastive Learning for Cross-Subject EEG-Based Emotion Recognition. IEEE Trans Affect Comput 2025, 16, 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, H. Transformer-Based EEG Decoding: A Survey. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuruppu, G.; Wagh, N.; Varatharajah, Y. EEG Foundation Models: A Critical Review of Current Progress and Future Directions. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Subramaniam, V.; Yaari, A.U.; Kreiman, G.; Katz, B.; Cases, I.; Barbu, A. BrainBERT: Self-Supervised Representation Learning for Intracranial Recordings. Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2023) 2023.

- Wu, D.; Li, S.; Yang, J.; Sawan, M. Neuro-BERT: Rethinking Masked Autoencoding for Self-Supervised Neurological Pretraining. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform 2024, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.; Torres, J.; Murhekar, A.; Liu, C.; Mishra, A.; Gwizdka, J.; Roychowdhury, S. A Survey on Bridging EEG Signals and Generative AI: From Image and Text to Beyond. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torma, S.; Szegletes, L. Generative Modeling and Augmentation of EEG Signals Using Improved Diffusion Probabilistic Models. J Neural Eng 2025, 22, 016001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Chen, X.; Shen, Y.; Nieuwoudt, M.; Pun, C.-M.; Wang, S. Generative AI Enables EEG Data Augmentation for Alzheimer’s Disease Detection Via Diffusion Model. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Symposium on Product Compliance Engineering - Asia (ISPCE-ASIA), IEEE, November 4 2023; pp. 1–6.

- Alexandre, H. de L.; Lima, C.A. de M. Synthetic EEG Generation Using Diffusion Models for Motor Imagery Tasks. 13th Brazilian Conference on Intelligent Systems (BRACIS 2024) 2025.

- Bai, Y.; Wang, X.; Cao, Y.; Ge, Y.; Yuan, C.; Shan, Y. DreamDiffusion: Generating High-Quality Images from Brain EEG Signals. 18th European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV 2024). 2023.

- Qian, D.; Zeng, H.; Cheng, W.; Liu, Y.; Bikki, T.; Pan, J. NeuroDM: Decoding and Visualizing Human Brain Activity with EEG-Guided Diffusion Model. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2024, 251, 108213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puah, J.H.; Goh, S.K.; Zhang, Z.; Ye, Z.; Chan, C.K.; Lim, K.S.; Fong, S.L.; Woon, K.S.; Guan, C. EEGDM: EEG Representation Learning via Generative Diffusion Model. Preprint 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Li, H.; Sun, X.; Kang, H.; An, S.; Wang, G.; Gao, Z. Self-Supervised Contrastive Learning for EEG-Based Cross-Subject Motor Imagery Recognition. J Neural Eng 2024, 21, 026038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, W.; Gu, Y.; Guo, S.; Ma, Y.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y. Self-Supervised Learning for Electroencephalogram: A Systematic Survey. journal ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hallgarten, P.; Bethge, D.; Özdcnizci, O.; Grosse-Puppendahl, T.; Kasneci, E. TS-MoCo: Time-Series Momentum Contrast for Self-Supervised Physiological Representation Learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 31st European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO), IEEE, September 4 2023; pp. 1030–1034.

- Kostas, D.; Aroca-Ouellette, S.; Rudzicz, F. BENDR: Using Transformers and a Contrastive Self-Supervised Learning Task to Learn From Massive Amounts of EEG Data. Front Hum Neurosci 2021, 15, 653659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarela, M.; Podgorelec, V. Recent Applications of Explainable AI (XAI): A Systematic Literature Review. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 8884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, W.; Khan, M.S.; Qasem, S.N.; Ghaban, W.; Saeed, F.; Hanif, M.; Ahmad, J. An Explainable and Efficient Deep Learning Framework for EEG-Based Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease and Frontotemporal Dementia. Front Med (Lausanne) 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvester, S.; Sagehorn, M.; Gruber, T.; Atzmueller, M.; Schöne, B. SHAP Value-Based ERP Analysis (SHERPA): Increasing the Sensitivity of EEG Signals with Explainable AI Methods. Behav Res Methods 2024, 56, 6067–6081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, Z. Applications and Advances of Combined FMRI-FNIRs Techniques in Brain Functional Research. Front Neurol 2025, 16, 1542075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, X.; Liu, C.; Gao, C.; Deng, Z.; Guan, W.; Gong, Y. A Multi-Branch Network for Integrating Spatial, Spectral, and Temporal Features in Motor Imagery EEG Classification. Brain Sci 2025, 15, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codina, T.; Blankertz, B.; von Lühmann, A. Multimodal FNIRS-EEG Sensor Fusion: Review of Data-Driven Methods and Perspective for Naturalistic Brain Imaging; Imaging neuroscience: Cambridge, Mass., 2025; Volume 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichy, R.M.; Oliva, A. A M/EEG-FMRI Fusion Primer: Resolving Human Brain Responses in Space and Time. Neuron 2020, 107, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, S.; Kang, P.; Moosmann, J.; Liu, M.; Bonazzi, P.; Rosipal, R.; Magno, M. On-Device Learning of EEGNet-Based Network For Wearable Motor Imagery Brain-Computer Interface. In Proceedings of the 2024 ACM International Symposium on Wearable Computers (ISWC ’24). 2024. [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Chen, J.; Ren, L.; Wang, X.; Li, D.; Zhang, H. Reviewing CAM-Based Deep Explainable Methods in Healthcare. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhl, E. The Challenge of Wearable Neurodevices for Workplace Monitoring: An EU Legal Perspective. Frontiers in Human Dynamics 2024, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).