Submitted:

29 December 2025

Posted:

30 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

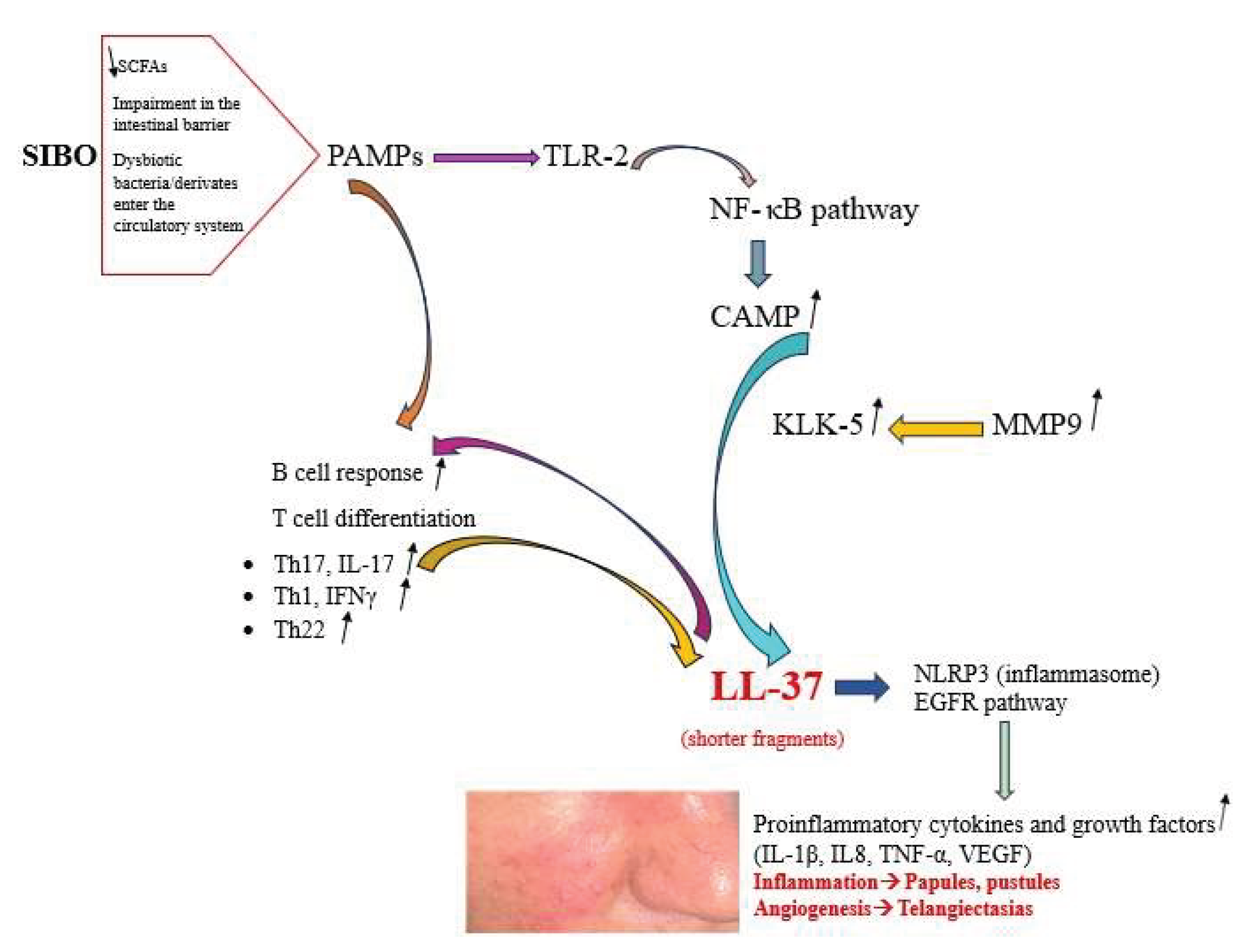

Rosacea is a chronic skin condition, characterized by persistent inflammation, manifesting primarily on the face and causing redness, papules, pustules, and phymatous changes. The etiology of rosacea is multifactorial, with immune system factors playing a crucial role in its pathogenesis. The scientific literature contains an increasing number of studies that suggest a correlation between rosacea and the gut microbiota. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) is defined as an excessive proliferation of potentially pathogenic bacteria within the small intestine of the gastrointestinal system. Multiple factors have been posited to explain the pathogenesis of rosacea, and the presence of SIBO has been identified as a potential factor in its occurrence. A decrease in the Lactobacillus genus, Prevotella copri, Lachnospiraceae, and Faecalibacterium within the gut microbiota may initiate inflammation related to rosacea. These bacterial species are crucial for regulating the intestinal mucosa. The findings indicate that there is an increase of Bacteriodes, Acidaminococcus and Megasphaera, and Ruminococcus in the gut microbiome of patients with rosacea. Probiotics can be advantageous for managing the intestinal microbiome, while Rifaximin treatment has shown efficacy in addressing inflammatory rosacea lesions associated related to SIBO. The present review has been undertaken with the objective of enhancing our comprehension of SIBO in rosacea. The emphasis has been placed on the pathogenetic mechanisms and the shift in the gut microbiota that will lead to understanding probiotic benefits and therapy options in rosacea patients.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth

3. Pathogenesis of Rosacea and Small Intestinal Bacteria Overgrowth

4. Preventive Effects of Probiotics on Rosacea

5. The Intestinal Microbiota in Rosacea Patients

6. Discussion

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gether, L.; Overgaard, L.K.; Egeberg. A.; Thyssen, J.P. Incidence and prevalence of rosacea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol 2018, 179, 282-289. [CrossRef]

- Sticchi, A.; Fiorito, F.; Kaleci, S.; Paganelli, A.; Manfredini, M.; Longo, C. Rosacea and treatment with retinoids: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther Adv Chronic Dis 2025, 16, 20406223251339964. [CrossRef]

- Ivanic, M.G.; Oulee, A.; Norden, A.; Javadi, S.S.; Gold, M.H.; Wu, J.J. Neurogenic Rosacea Treatment: A Literature Review. J Drugs Dermatol 2023, 22, 566-575. [CrossRef]

- Maden S. Rosacea: An Overview of Its Etiological Factors, Pathogenesis, Classification and Therapy Options. Dermato 2023, 3, 241-262.

- Sharma, A.; Kroumpouzos, G.; Kassir, M.; Galadari, H.; Goren, A.; Grabbe, S; Goldust M. Rosacea management: A comprehensive review. J Cosmet Dermatol 2022, 21, 1895-1904.

- Sánchez-Pellicer, P.; Eguren-Michelena, C.; García-Gavín, J.; Llamas-Velasco, M.; Navarro-Moratalla, L.; Núñez-Delegido, E.; Agüera-Santos, J.; Navarro-López, V. Rosacea, microbiome and probiotics: the gut-skin axis. Front Microbiol 2024, 14, 1323644. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.Y.; Chi, C.C. Rosacea, Germs, and Bowels: A Review on Gastrointestinal Comorbidities and Gut-Skin Axis of Rosacea. Adv Ther 2021, 38, 1415-1424. [CrossRef]

- Achufusi, T.G.O.; Sharma, A.; Zamora, E.A.; Manocha, D. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: Comprehensive Review of Diagnosis, Prevention, and Treatment Methods. Cureus 2020, 12, e8860.

- Zafar, H.; Jimenez, B.; Schneider, A. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: current update. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2023, 39, 522-528. [CrossRef]

- Sachdev, A.H.; Pimentel, M. Gastrointestinal bacterial overgrowth: pathogenesis and clinical significance. Ther Adv Chronic Dis 2013, 4, 223-231. [CrossRef]

- Skrzydło-Radomańska, B.; Cukrowska, B. How to Recognize and Treat Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth? J Clin Med 2022, 11, 6017. [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, M.; Saad, R.J.; Long, M.D.; Rao, S.S.C. ACG Clinical Guideline: Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Am J Gastroenterol 2020, 115, 165-178. [CrossRef]

- Belkaid, Y.; Naik, S. Compartmentalized and systemic control of tissue immunity by commensals. Nat Immunol 2013, 14, 646-653. [CrossRef]

- Takiishi, T.; Fenero, C.I.M.; Câmara, N.O.S. Intestinal barrier and gut microbiota: Shaping our immune responses throughout life. Tissue Barriers 2017, 5, e1373208. [CrossRef]

- Kinashi, Y.; Hase, K. Partners in Leaky Gut Syndrome: Intestinal Dysbiosis and Autoimmunity. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 673708. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Nascimento, L.; Massari, P.; Wetzler, L.M. The role of TLR2 in infection and immunity. Front Immunol 2012, 3, 79. [CrossRef]

- Ahn, C.S.; Huang, W.W. Rosacea pathogenesis. Dermatol Clin 2018, 36, 81–86.

- Yamasaki, K.; Kanada, K.; Macleod, D.T.; Borkowski, A.W.; Morizane, S.; Nakatsuji, T.; Cogen, A.L.; Gallo, R.L. TLR2 expression is increased in rosacea and stimulates enhanced serine protease production by keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol 2011, 131, 688-97. [CrossRef]

- Geng, R.S.Q.; Bourkas, A.N.; Mufti, A.; Sibbald, R.G. Rosacea: Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Correlates. J Cutan Med Surg 2024, 28, 178-189. [CrossRef]

- Meyer-Hoffert, U.; Schroder, J.M. Epidermal proteases in the pathogenesis of rosacea. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc 2011, 15, 16-23.

- Yamasaki, K.; Di Nardo, A.; Bardan, A.; Murakami, M.; Ohtake, T.; Coda, A.; Dorschner, R.A.; Bonnart, C.; Descargues, P.; Hovnanian. A.; Morhenn, V.B.; Gallo, R.L. Increased serine protease activity and cathelicidin promotes skin inflammation in rosacea. Nat Med 2007, 13, 975-980.

- Muto, Y.; Wang, Z.; Vanderberghe, M.; Two, A.; Gallo, R.L.; Di Nardo, A. Mast cells are key mediators of cathelicidin-initiated skin inflammation in rosacea. J Invest Dermatol 2014, 134, 2728-2736. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.H.; Hwang, I.; Lee, E.; Cho, H.J.; Ryu, J.H.; Kim, T.G.; Yu, J.W. Antimicrobial Peptide LL-37 Drives Rosacea-Like Skin Inflammation in an NLRP3-Dependent Manner. J Invest Dermatol 2021, 141, 2885-2894.e5. [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Zhou, F. Inflammasomes in Common Immune-Related Skin Diseases. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 882.

- Gerber, P.A.; Buhren, B.A.; Steinhoff, M.; Homey, B. Rosacea: The cytokine and chemokine network. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc 2011, 15, 40-47. [CrossRef]

- Sakabe, J.; Umayahara, T.; Hiroike, M.; Shimauchi, T.; Ito, T.; Tokura, Y. Calcipotriol increases hCAP18 mRNA expression but inhibits extracellular LL37 peptide production in IL-17/IL-22-stimulated normal human epidermal keratinocytes. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014 Sep;94(5):512-6. [CrossRef]

- Pasare, C.; Medzhitov, R. Control of B-cell responses by Toll-like receptors. Nature 2005, 438, 364–368.

- Kumar, V. Going, Toll-like receptors in skin inflammation and inflammatory diseases. EXCLI J 2021, 20, 52-79.

- Koh, A.; De Vadder, F.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Bäckhed, F. From Dietary Fiber to Host Physiology: Short-Chain Fatty Acids as Key Bacterial Metabolites. Cell 2016, 165, 1332-1345. [CrossRef]

- Trompette ,A.; Pernot, J.; Perdijk, O.; Alqahtani, R.A.A.; Domingo, J.S.; Camacho-Muñoz, D.; Wong, N.C.; Kendall, A.C.; Wiederkehr, A.; Nicod, L.P.; Nicolaou, A.; von Garnier, C.; Ubags, N.D.J.; Marsland, B.J. Gut-derived short-chain fatty acids modulate skin barrier integrity by promoting keratinocyte metabolism and differentiation. Mucosal Immunol 2022, 15, 908-926. [CrossRef]

- Salem, I.; Ramser, A.; Isham, N.; Ghannoum, M.A. The Gut Microbiome as a Major Regulator of the Gut-Skin Axis. Front Microbiol 2018, 9, 1459.

- Mahmud, M.R.; Akter, S.; Tamanna, S.K.; Mazumder, L.; Esti, I.Z.; Banerjee, S.; Akter, S.; Hasan, M.R.; Acharjee, M.; Hossain, M.S.; Pirttilä, A.M. Impact of gut microbiome on skin health: gut-skin axis observed through the lenses of therapeutics and skin diseases. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2096995.

- Qi, X.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wei, J.; Zhao, Z.; Li, J.; Chen, T. Probiotics suppress LL37 generated rosacea-like skin inflammation by modulating the TLR2/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway. Food Funct 2024, 15, 8916-8934.

- Yu, J.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, M.; Li, Q.; Cao, M.; Song, W.; Zhao, F.; Kwok, L-Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, R.; Sun, Z. Effect of combined probiotics and doxycycline therapy on the gut-skin axis in rosacea. mSystems 2024, 9, e0120124. [CrossRef]

- Gueniche, A.; Benyacoub, J.; Philippe, D.; Bastien, P.; Kusy, N.; Breton, L.; Blum, S.; Castiel-Higounenc, I. Lactobacillus paracasei CNCM I-2116 (ST11) inhibits substance P-induced skin inflammation and accelerates skin barrier function recovery in vitro. Eur J Dermatol 2010, 20, 731-737. [CrossRef]

- Fortuna, M.C.; Garelli, V.; Pranteda, G.; Romaniello, F.; Cardone, M.; Carlesimo, M.; Rossi, A. A case of Scalp Rosacea treated with low dose doxycycline and probiotic therapy and literature review on therapeutic options. Dermatol Ther 2016, 29, 249-251. [CrossRef]

- Manzhalii, E.; Hornuss, D.; Stremmel, W. Intestinal-borne dermatoses significantly improved by oral application of Escherichia coli Nissle 1917. World J Gastroenterol 2016, 22, 5415-5421.

- Pinchuk, I.V.; Bressollier, P.; Verneuil, B.; Fenet, B.; Sorokulova, I.B.; Mégraud, F.; Urdaci, M.C. In vitro anti-Helicobacter pylori activity of the probiotic strain Bacillus subtilis 3 is due to secretion of antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2001, 45, 3156-3161. [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Arrones, O.M.; Ortega-Quijano, D.; Perez-Brocal, V.; Fernandez-Nieto, D.; Jimenez, N.; de Las Heras, E.; Moya, A.; Perez-Garcia, B. Dysbiotic gut microbiota in patients with inflammatory rosacea: another clue towards the existence of a brain-gut-skin axis. Br J Dermatol 2021, 185, 655-657. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.J.; Lee, W.H.; Ho, H.J.; Tseng, C.H.; Wu, C.Y. An altered fecal microbial profiling in rosacea patients compared to matched controls. J Formos Med Assoc 2021, 120, 256-264. [CrossRef]

- Nam, J.H.; Yun, Y.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, H.N.; Jung, H.J.; Chang, Y.; Ryu, S.; Shin, H.; Kim, H.L.; Kim, W.S. Rosacea and its association with enteral microbiota in Korean females. Exp Dermatol 2018, 27, 37-42. [CrossRef]

- Guertler, A.; Hering, P.; Pacífico, C.; Gasche, N.; Sladek, B.; Irimi, M.; French, L.E.; Clanner-Engelshofen, B.M.; Reinholz, M. Characteristics of Gut Microbiota in Rosacea Patients-A Cross-Sectional, Controlled Pilot Study. Life (Basel) 2024, 14, 585.

- Li, J.; Yang, F.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, X. Causal relationship between gut microbiota and rosacea: a two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Front Med (Lausanne) 2024, 11, 1322685. [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.B.; Baiseitova, A.; Zahoor, M.; Ahmad, I.; Ikram, M.; Bakhsh, A.; Shah, M.A.; Ali, I.; Idress, M.; Ullah, R.; Nasr, F.A.; Al-Zharani, M. Probiotic significance of Lactobacillus strains: a comprehensive review on health impacts, research gaps, and future prospects. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2431643.

- Bedarf, J.R.; Hildebrand, F.; Coelho, L.P.; Sunagawa, S.; Bahram, M.; Goeser, F.; Bork, P.; Wüllner, U. Functional implications of microbial and viral gut metagenome changes in early-stage L-DOPA-naïve Parkinson’s disease patients. Genome Med 2017, 9, 39.

- Manor, O.; Dai, C.L.; Kornilov, S.A.; Smith, B.; Price, N.D.; Lovejoy, J.C.; Gibbons, S.M.; Magis, A.T. Health and disease markers correlate with gut microbiome composition across thousands of people. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 5206.

- Parodi, A.; Paolino, S.; Greco, A.; Drago, F.; Mansi, C.; Rebora, A.; Parodi, A.; Savarino, V. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in rosacea: clinical effectiveness of its eradication. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008, 6, 759-764.

- Drago, F.; De Col, E.; Agnoletti, A.F.; Schiavetti, I.; Savarino, V.; Rebora, A.; Paolino, S.; Cozzani, E.; Parodi, A. The role of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in rosacea: A 3-year follow-up. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016, 75, e113-5.

- Manfredini, M.; Barbieri, M.; Milandri, M.; Longo, C. Probiotics and Diet in Rosacea: Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 411. [CrossRef]

| Authors and year | Study design | Increased levels of intestinal microbiota | Decreased levels of intestinal microbiota | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moreno-Arrones et al. [39] 2021 | 15 PPR patients 12 (80%) females 15 controls 5 (33.3%) females LEfSe analysis |

Syntrophomonadaceae family, Anaerovorax genus, Bacteroidales sp., Tyzzerella sp., Lachnospiraceae family, Akkermansiamuciniphila, Parabacteroides distasonis |

Prevotella copri | The study outlines intestinal dysbiosis in rosacea patients. |

| Chen et al. [40] 2021 | 11 patients 4 ETR %36.3 7 PPR %63.7 90.9% female 110 controls 90.9% female LEfSe analysis |

Rhabdochlamydia, CF231, Bifidobacterium, Sarcina, Ruminococcus |

Lactobacillus, Megasphaera, Acidaminococcus, Haemophilus, Roseburia, Clostridium, Citrobacter |

Faecal microbiota profiles in rosacea patients associated with sulfur metabolism, cobalamin, and carbohydrate transport. |

| Nam et al. [41] 2018 | 12 patients 251 controls MetagenomeSeq |

Acidaminococcus, Megasphaera, |

Peptococcaceae, Methanobrevibacter, |

Patients diagnosed with rosacea exhibit a more abundant and distinct profile of enteral microbiota. |

| Guertler et al. [42] 2024 | 54 patients 39 females 15 males 50 controls MiSeq 16S rRNA sequencing |

Oscillobacter sp., Flavonifractorplauti,Ruminococccaceae UBA1819 |

Faecalibacteriumprausnitzii Lachnoospiraceae ND 3007 group sp, Ruminococcaceae | There is a decline in microbial richness and diversity in rosacea patients. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).