Submitted:

29 December 2025

Posted:

30 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

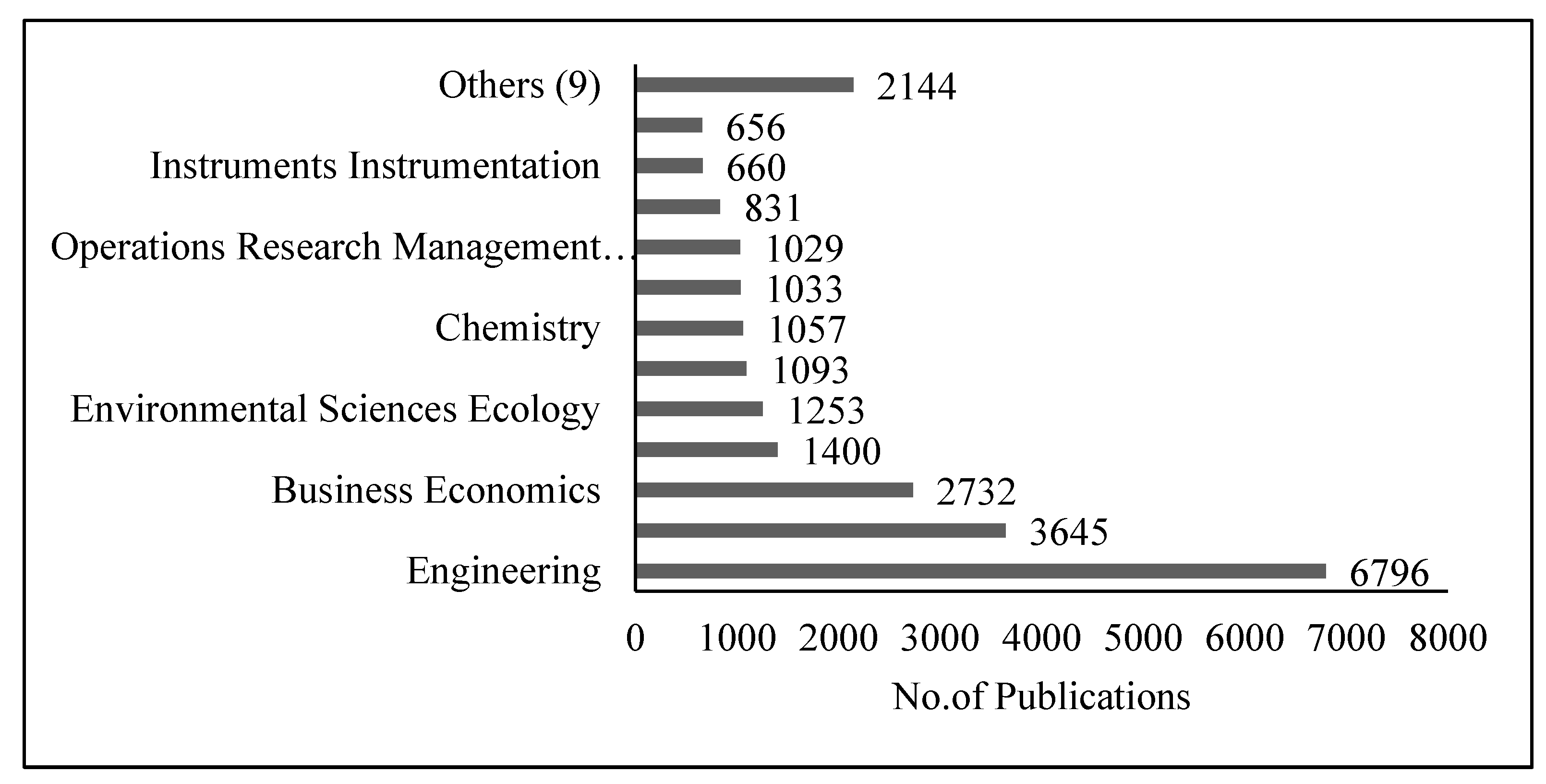

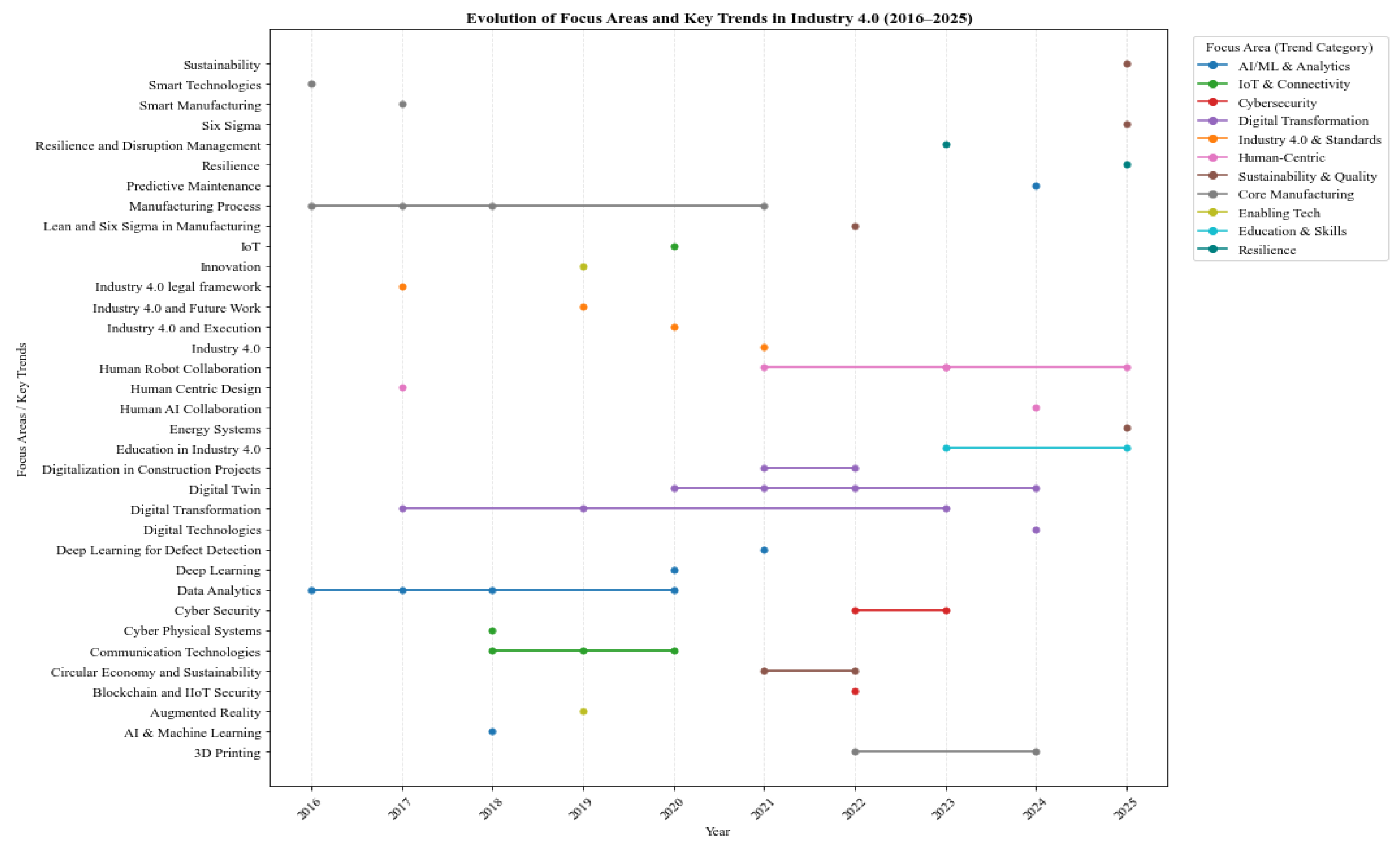

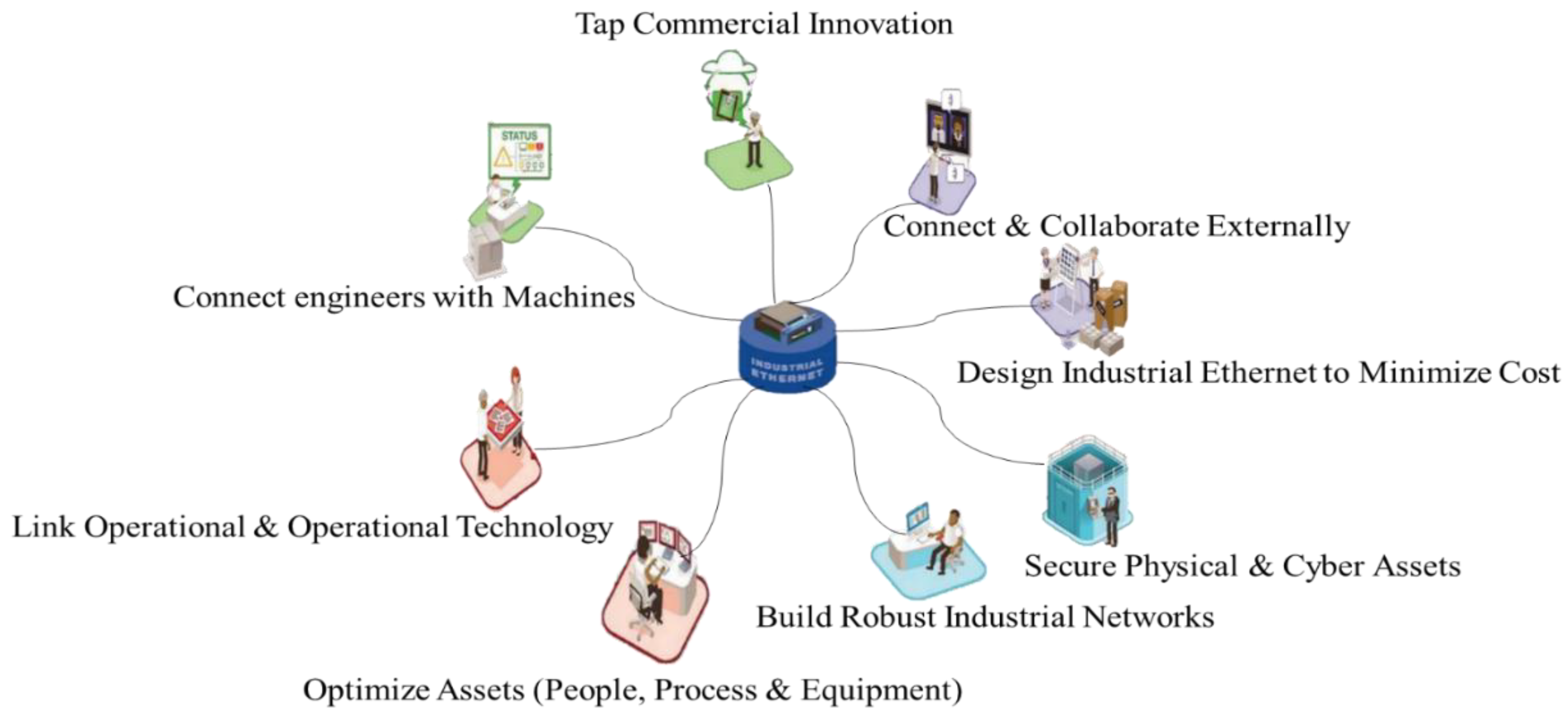

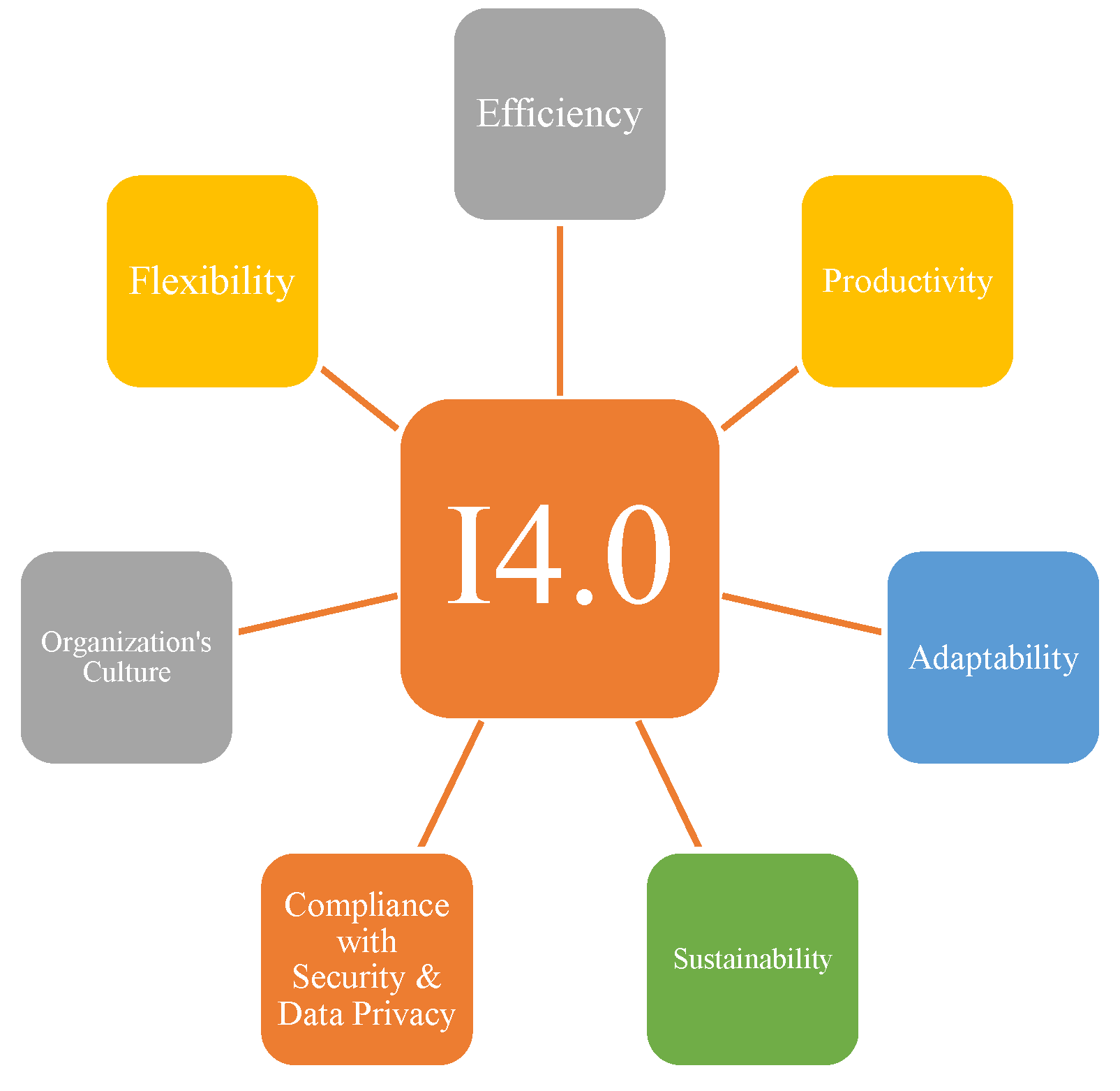

This study aims to achieve an understanding of Industry 4.0 and examine its advantages and drawbacks. The research study offers a thorough literature review on the evolution of technological trends related to Industry 4.0 over the past decade, including an in-depth analysis of its potential to support the entire organizational value chain, thereby augmenting and enhancing the existing supply chain infrastructure of the firm. It is widely recognized that the implementation of Industry 4.0 presents various challenges and inherent limitations. Is it attainable & sustainable? This study is comprehensive, drawing upon a literature review encompassing 15,053 papers up to 2024. The chosen articles are centered around the concept of "Industry 4.0" and its various interpretations. Moreover, to discern emerging themes through an extensive literature review encompassing 15,053 papers, a year-wise topic modelling approach was utilized, employing the BERTopic methodology. The research indicates that engineering and computer science are the predominant disciplines addressing the complexities of Industry 4.0. The findings underscored the complexities encountered in the implementation of I4.0 tools, encompassing adaptability, flexibility, organizational culture, and efficiency. This paper elucidates the diverse technologies linked to Industry 4.0 that have ignited a dialogue in the realms of innovation and technology. The array of technological advancements, including the Internet of Things (IoT) and blockchain, presents significant advantages and sustainability over time. This work will help academics to further research in Industry 4.0 and provide insights into areas where additional research can be conducted.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Methodology Description and Keyword Selection

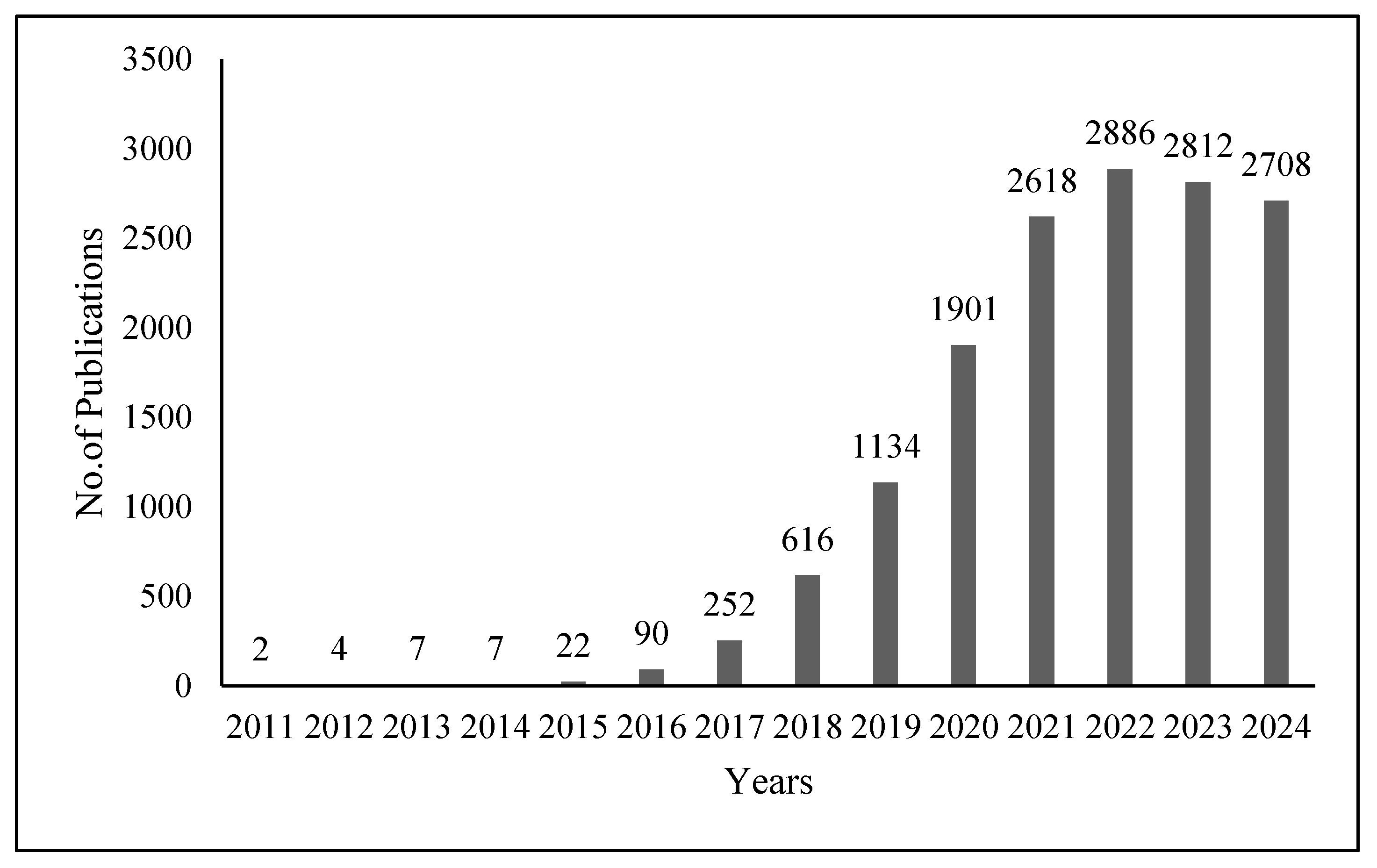

2.2. No. of Publications

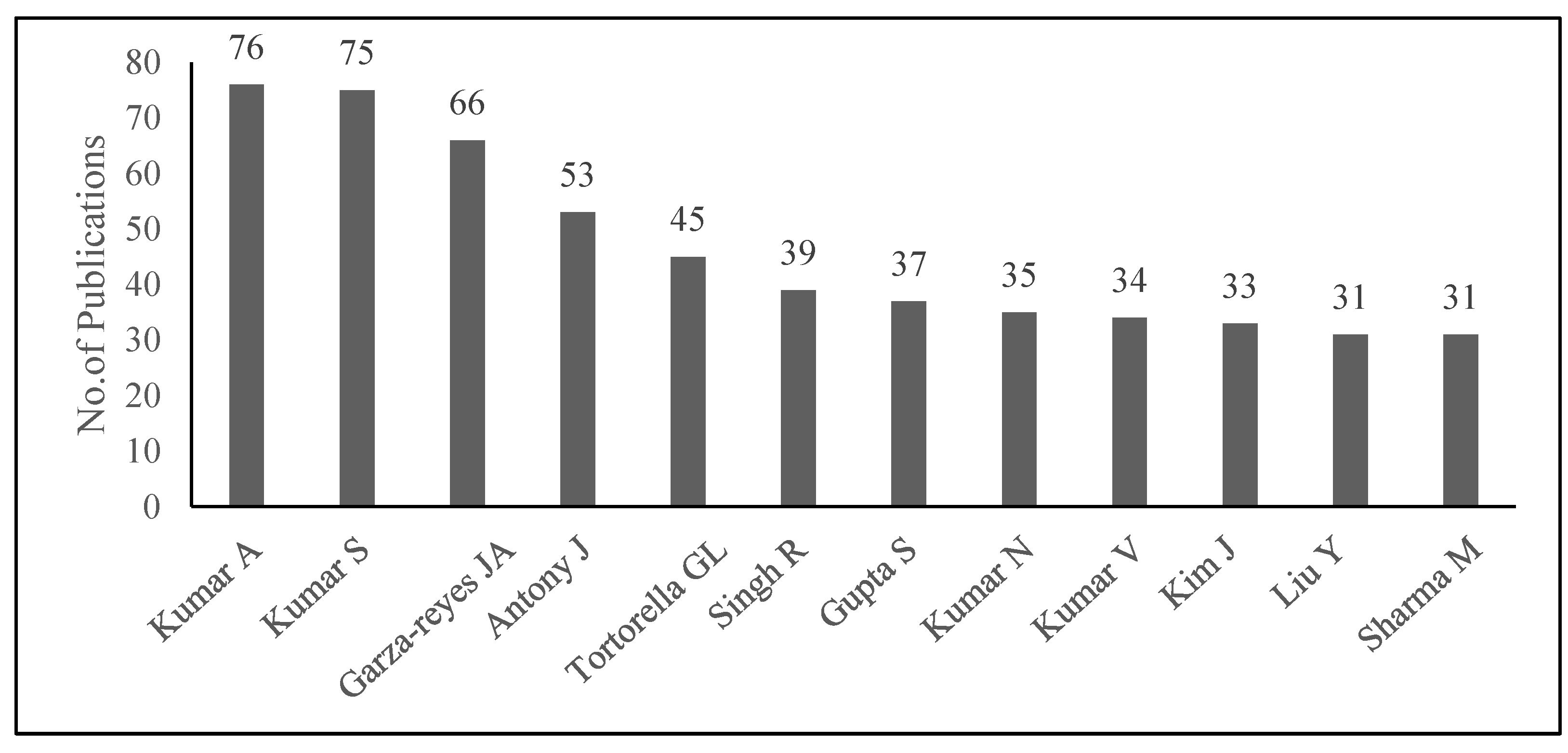

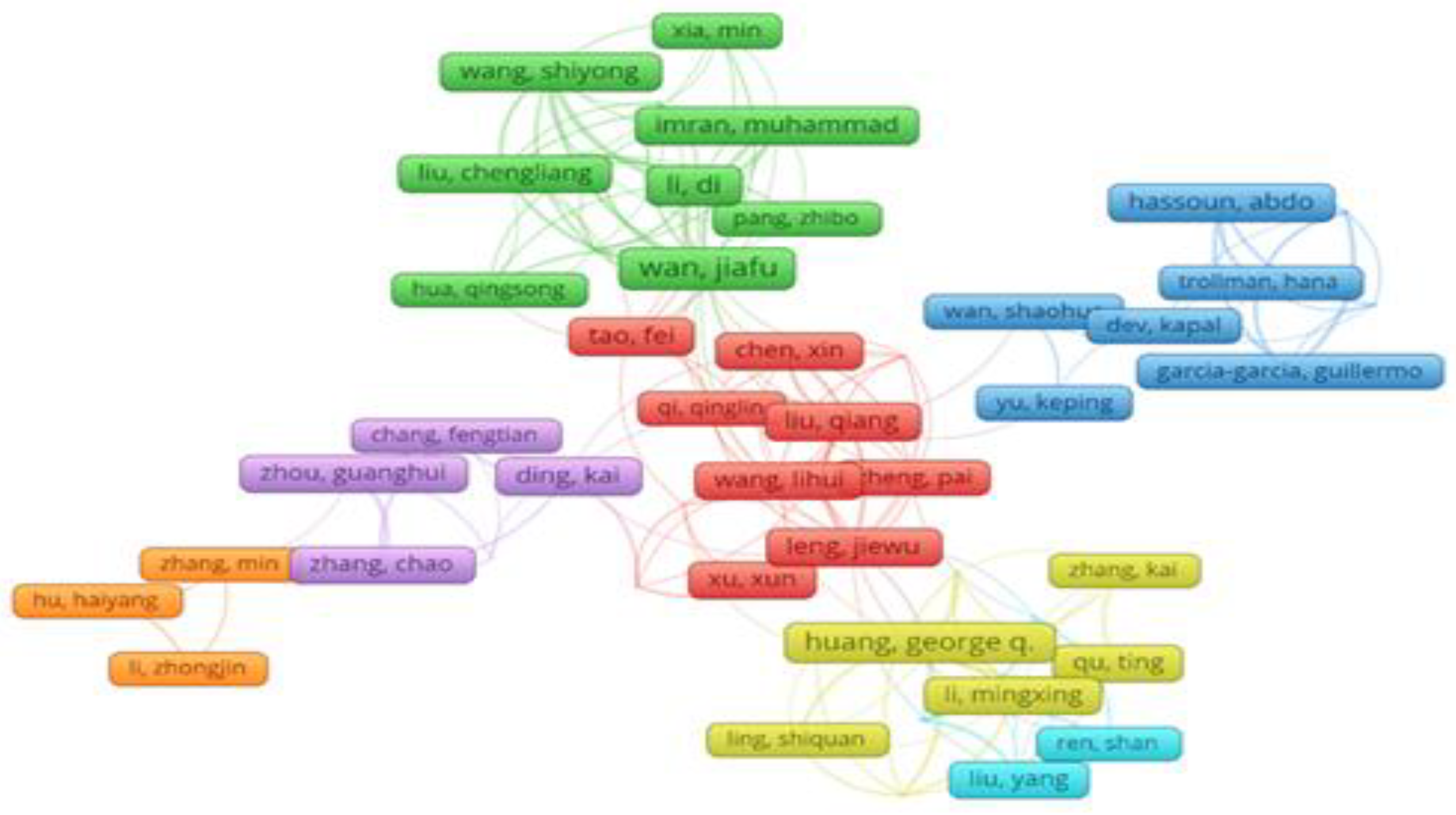

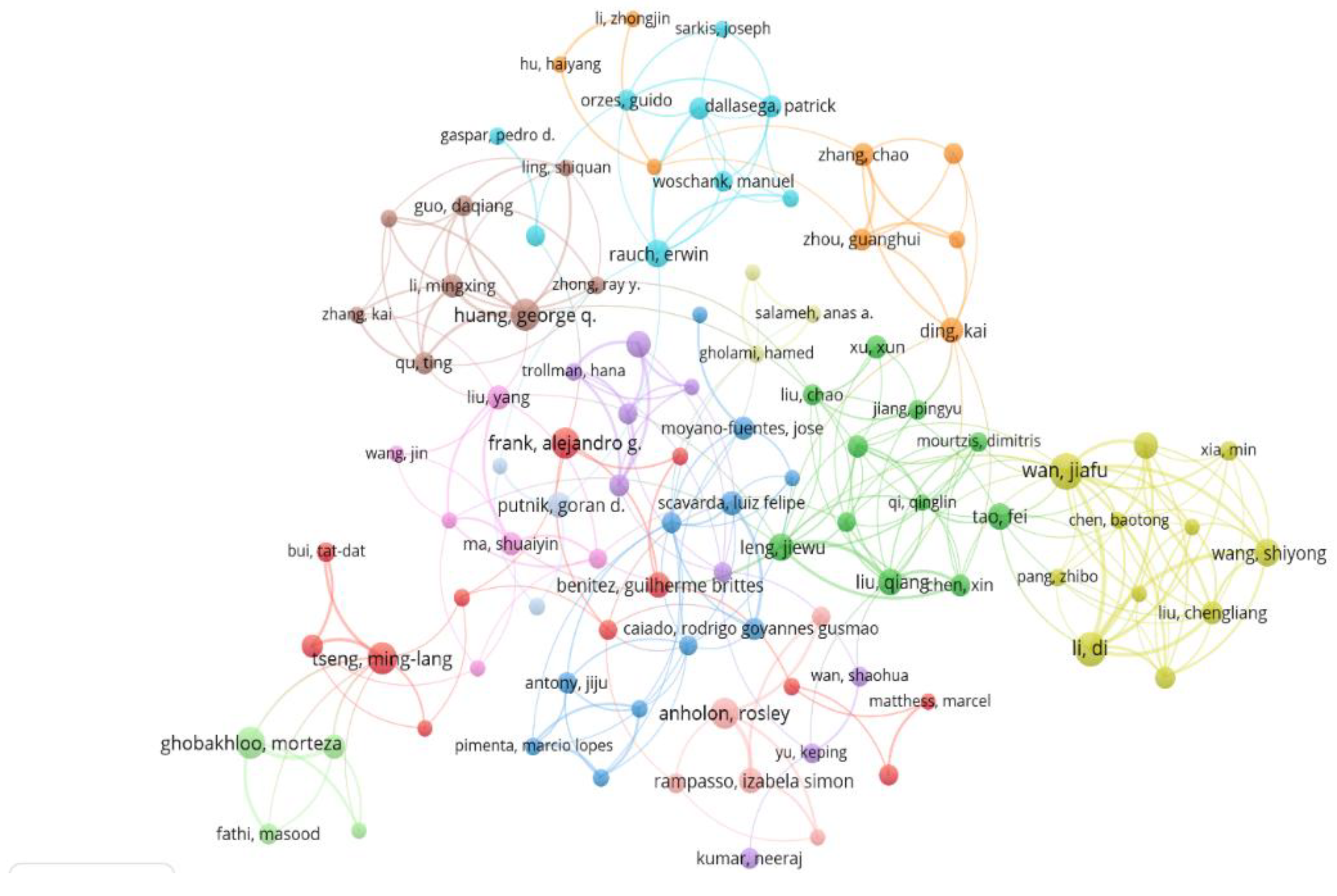

2.3. Highly Cited Authors

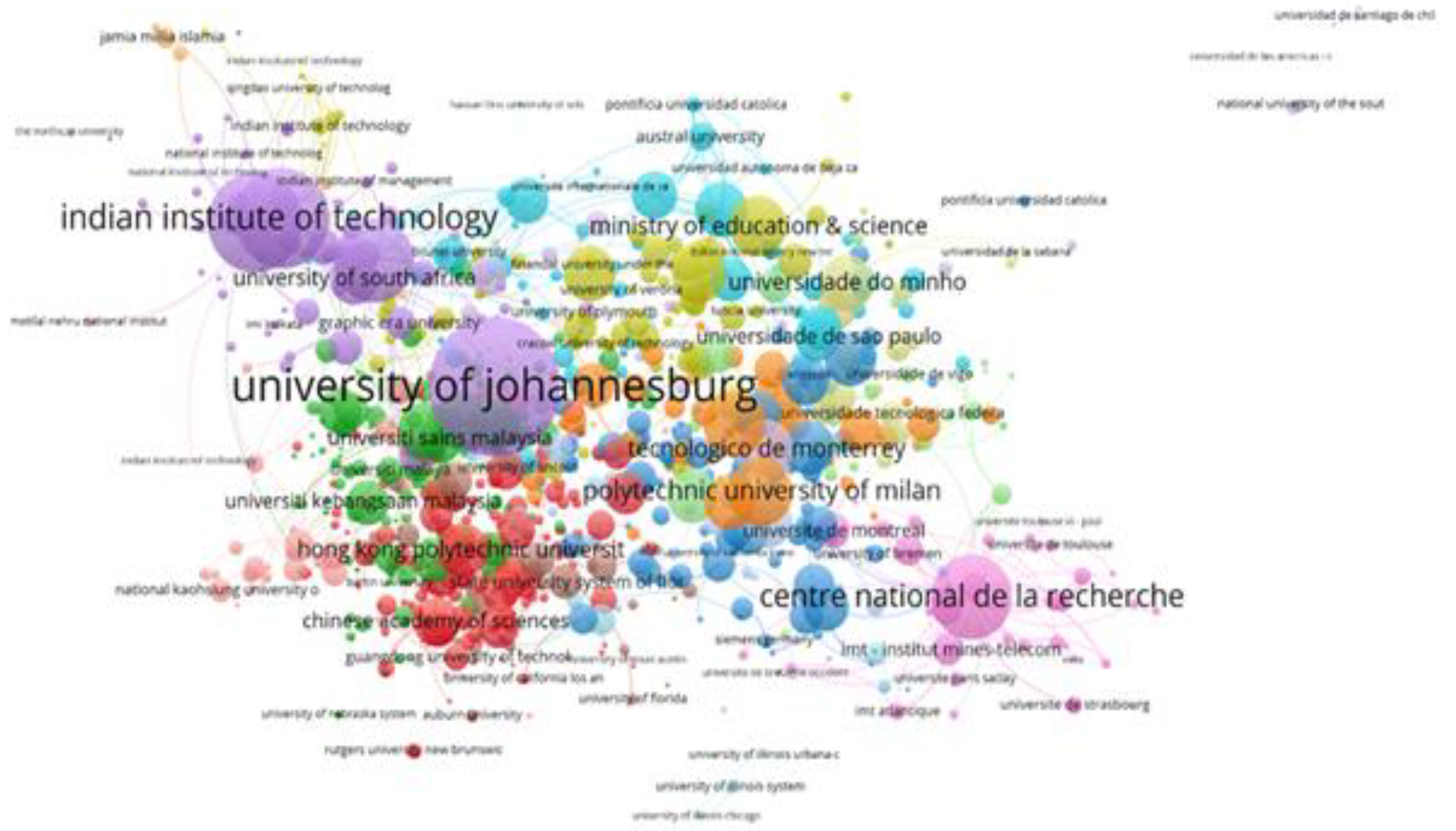

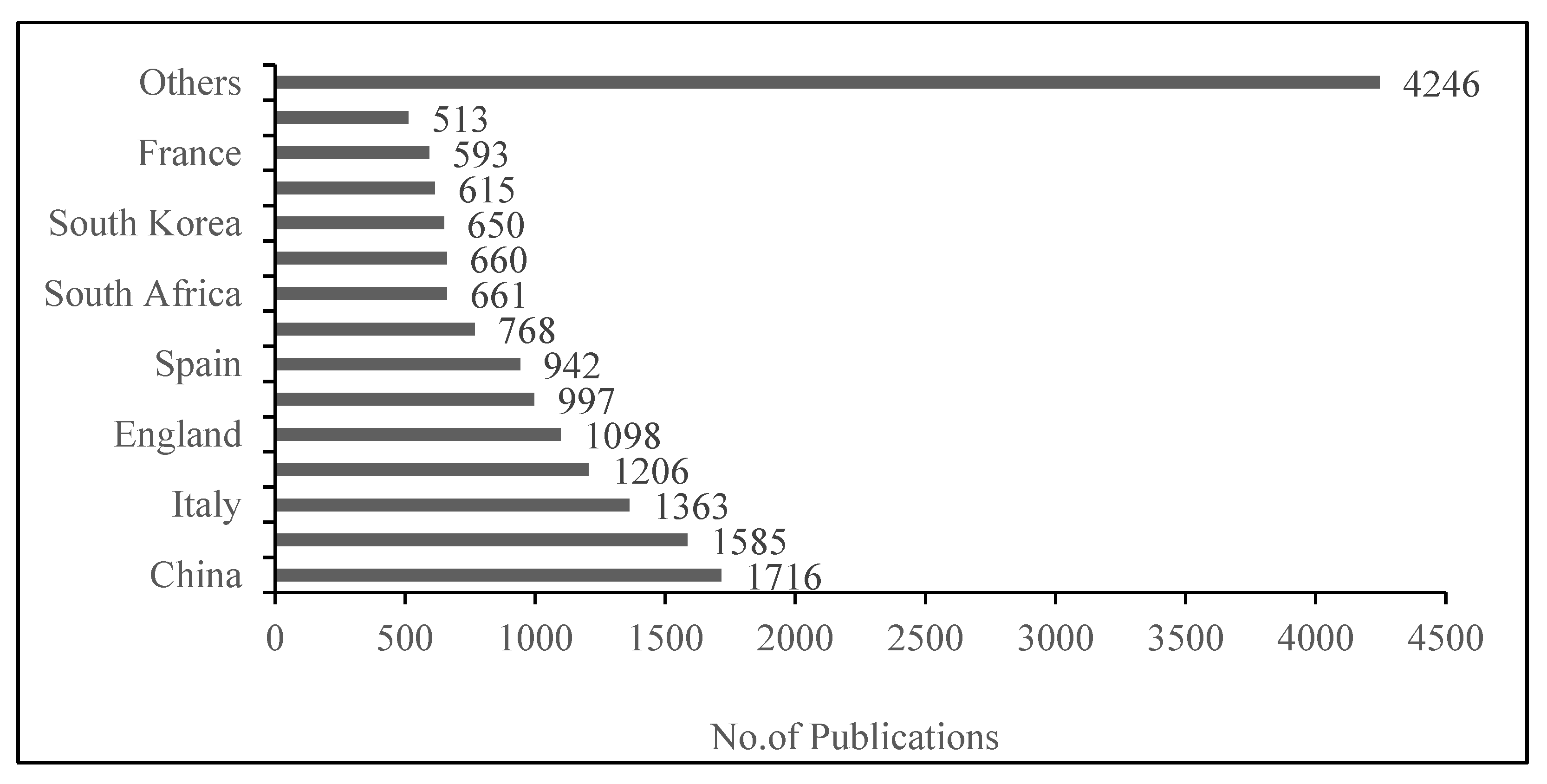

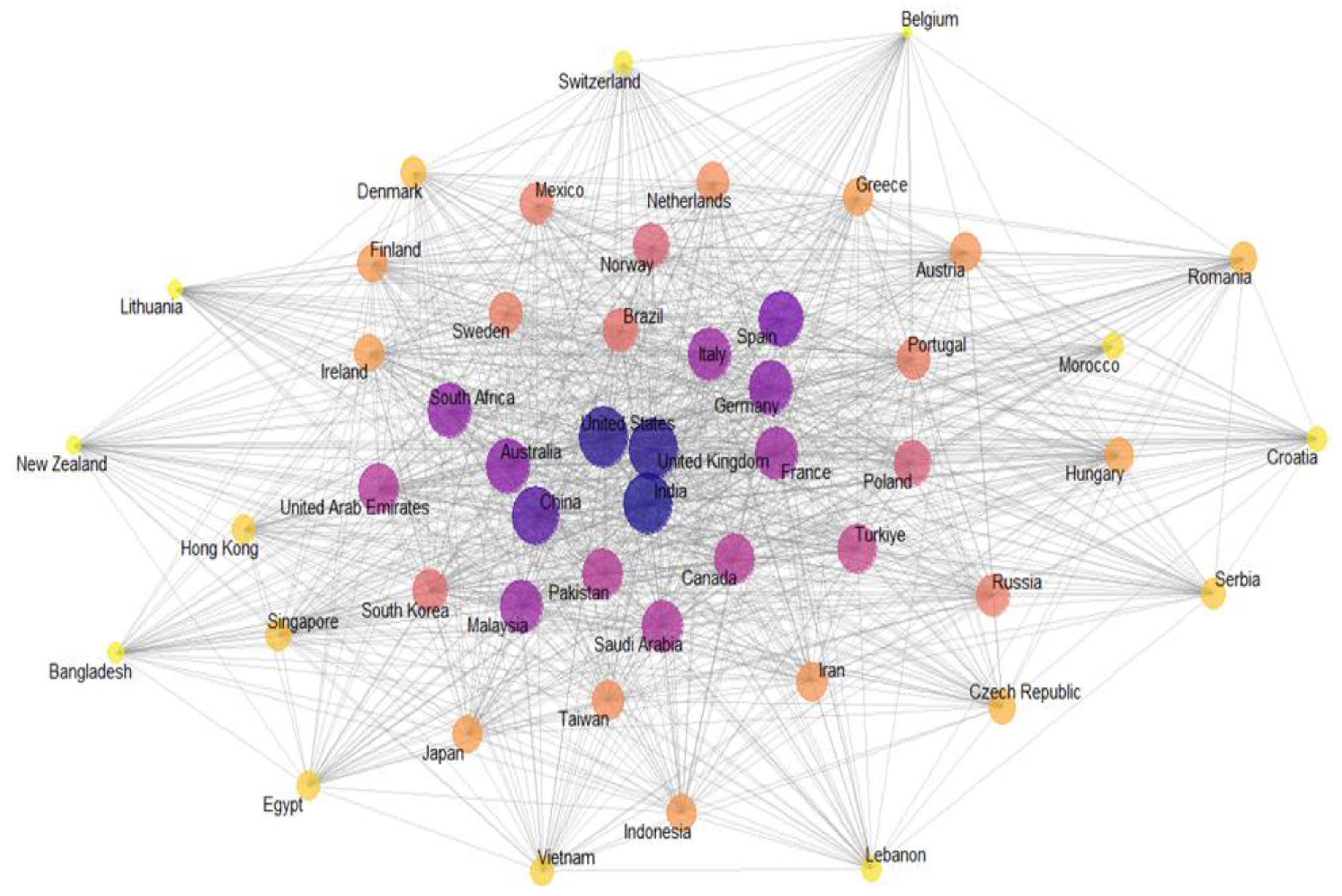

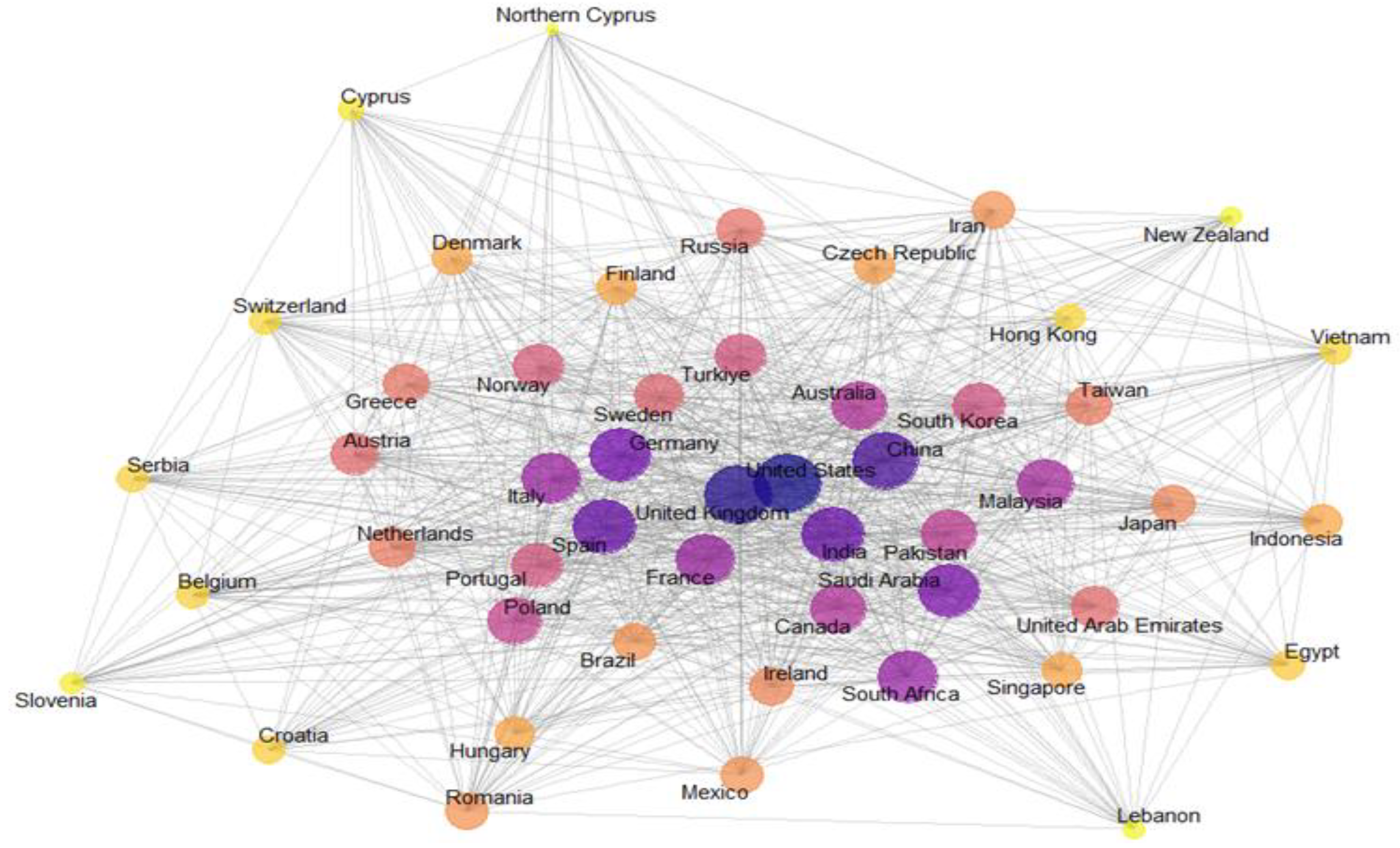

2.4. Country-Wise Publications

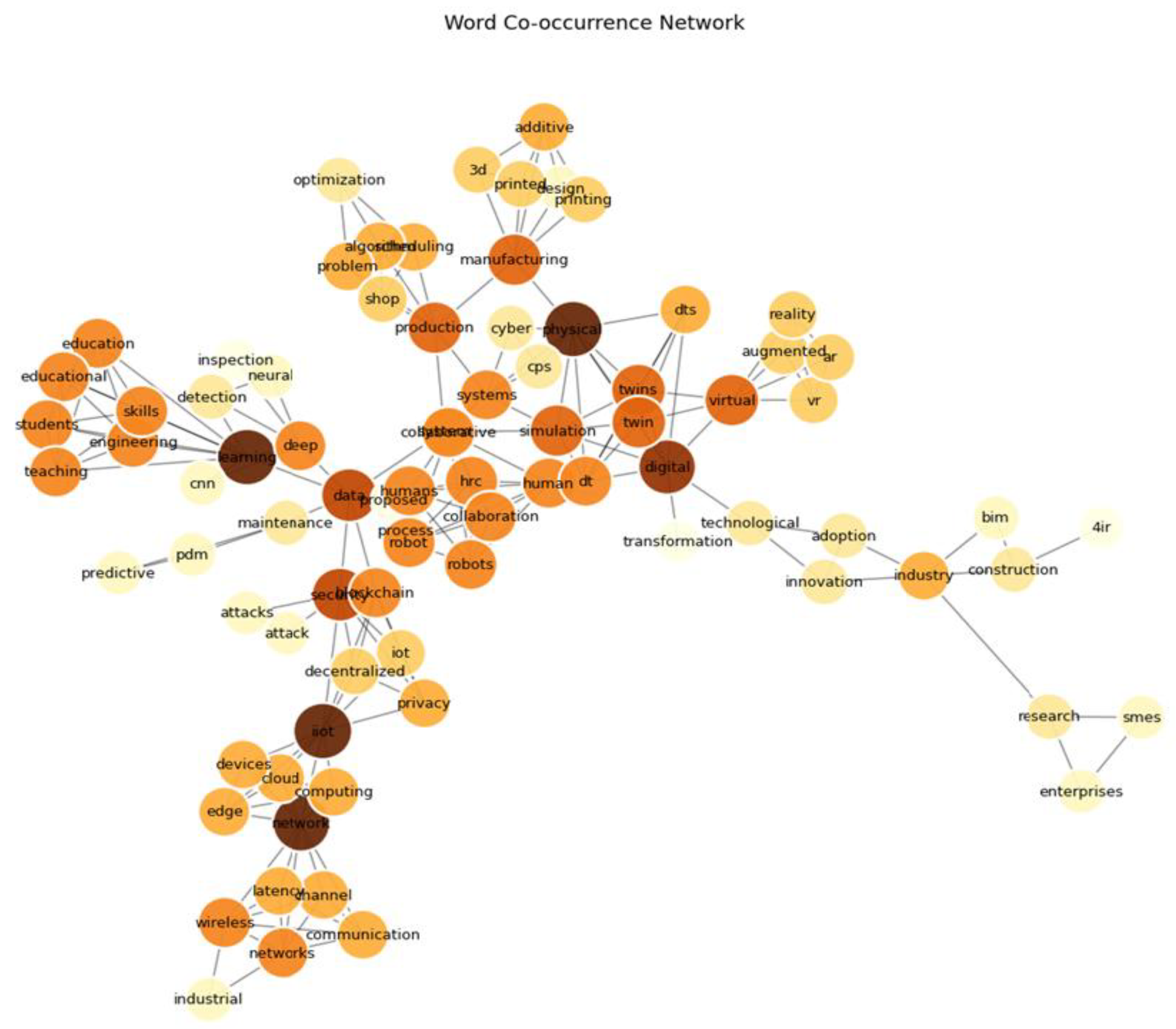

3. Emerging Research Areas from the Literature Review on I4.0

4. Attributes Emerging from the Literature Review of I4.0

4.1. Openness to Change & Agility in I4.0

4.1.1. Risk in I4.0

4.1.2. Resilience in I4.0

5. Discussion and Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SCM | Supply Chain Management |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| CNC | Computer Numerical Control |

| CPT | Cyber Physical Technology |

Appendix A

| Top Publishers | Publications |

| MDPI AG | 2995 |

| Elsevier | 2737 |

| Springer Nature | 1407 |

| IEEE | 1274 |

| Taylor & Francis | 1068 |

| Emerald | 1057 |

| Wiley | 477 |

| Sage | 228 |

| Frontiers Media Sa | 130 |

| Aosis | 90 |

| Hindawi | 89 |

| Walter De Grutyer | 86 |

| World Scientific | 75 |

| Polska Akad Nauk | 73 |

| Inderscience | 69 |

| Los Press | 63 |

| Wiley - Hindawi | 63 |

| IGI Global | 56 |

| Routledge | 55 |

| Sciendo | 54 |

| Tech Science Press | 51 |

Appendix B

| Journal Name | Publications |

| Sustainability | 711 |

| Applied Sciences Basel | 479 |

| IEEE Access | 416 |

| Sensors | 410 |

| International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology | 214 |

| IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics | 198 |

| Computers Industrial Engineering | 190 |

| International Journal of Production Research | 184 |

| Technological Forecasting and Social Change | 178 |

| Electronics | 161 |

| Computers in Industry | 160 |

| Energies | 151 |

| Processes | 151 |

| Journal of Manufacturing Systems | 143 |

| Journal of Cleaner Production | 132 |

| Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management | 111 |

| International Journal of Computer Integrated Manufacturing | 108 |

| IEEE Internet of Things Journal | 96 |

| Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing | 91 |

| Machines | 90 |

| Production Planning Control | 86 |

| International Journal of Production Economics | 84 |

| Journal of Industrial Information Integration | 83 |

| IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management | 76 |

| TQM Journal | 74 |

| International Journal of Interactive Design and Manufacturing | 68 |

| Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing | 64 |

| Buildings | 59 |

| Annals of Operations Research | 56 |

| Benchmarking an International Journal | 56 |

| Manufacturing Letters | 56 |

| Heliyon | 55 |

| Business Strategy and the Environment | 54 |

| Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence | 54 |

| Expert Systems with Applications | 51 |

Appendix C

| Year | Technologies | Trends |

| 2016 | Smart Technologies Data Analysis Manufacturing Process |

Smart Technologies in Manufacturing Process |

| 2017 | Industry 4.0 legal framework Manufacturing process Smart Manufacturing Data Analysis Digital Transformation Human Centric Design |

Industry 4.0 legality Smart Technologies in Manufacturing Human Centric Design |

| 2018 | Communication Technologies Cyber Physical Systems AI & Machine Learning Manufacturing Process Data Analytics |

Cyber Physical Systems AI & Machine Learning Communication Technologies |

| 2019 | Industry 4.0 and Future Work Communication Technologies Augmented Reality Digital Transformation Innovation |

Industry 4.0 and Future Work Communication Technologies Digital Transformation |

| 2020 | IoT Deep Learning Communication Technologies Digital Twins Industry 4.0 and Execution Data Analysis |

IoT Communication Technologies Digital Twins |

| 2021 | Digital Twin Digitalization in Construction Projects Industry 4.0 Manufacturing Process Circular Economy and Sustainability Deep Learning for Defect Detection Human Robot Collaboration |

Digital Twin Circular Economy and Sustainability Human Robot Collaboration Manufacturing Process in Industry 4.0 |

| 2022 | Digital Twin 3D Printing Blockchain and IIoT Security Digitalization in Construction Projects Cyber Security Circular Economy and Sustainability Practices in I4.0 Lean and Six Sigma in Manufacturing |

Digital Twin IIoT Security & Cyber Security Circular Economy and Sustainability Practices in I4.0 |

| 2023 | Education in Industry 4.0 Cybersecurity Digital Transformation Human Robot Collaboration Resilience and Disruption Management Human Robot Collaboration |

Cybersecurity Digital Transformation Human Robot Collaboration Resilience |

| 2024 | Digital Twin Digital Technologies 3D Printing Human AI Collaboration Predictive Maintenance |

Digital Twin Digital Technologies Human Robot Collaboration |

| 2025 | Education in Industry 4.0 Human Robot Collaboration Resilience Sustainability Energy Systems Six Sigma |

Human Robot Collaboration Resilience Sustainability |

References

- Aceto, G., Persico, V., & Pescapé, A. (2020). Industry 4.0 and Health: Internet of Things, Big Data, and Cloud Computing for Healthcare 4.0. Journal of Industrial Information Integration, 18, 100129. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A. (2022). China Industry 4.0 Market Size. Retrieved on June 14, 2025, from https://straitsresearch.com/report/industry-4.0-market/china#:~:text=The%20China%20Industry%204.0%20market,period%20(2024%2D2032).

- Belden (2022). The Connected Factory in Action. Retrieved on April 15, 2022, from www.belden.com .

- Brennan, L., Brian, F., Professor Paul Coughlan, P., Ferdows, K., Godsell, J., Golini, R.,... Taylor, M. (2015), Manufacturing in the world: where next? International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 35(9), 1253-1274. [CrossRef]

- Büchi, G., Cugno, M., & Castagnoli, R. (2020). Smart factory performance and Industry 4.0 Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 150, 119790. [CrossRef]

- Buer, S.-V., Strandhagen, J. O., & Chan, F. T. S. (2018). The link between Industry 4.0 and lean manufacturing: mapping current research and establishing a research agenda. International Journal of Production Research, 56(8), 2924-2940. [CrossRef]

- Carter, C. R., & Washispack, S. (2018). Mapping the Path Forward for Sustainable Supply Chain Management: A Review of Reviews. Journal of Business Logistics, 39(4), 242-247.

- Castelo-Branco, I., Cruz-Jesus, F., & Oliveira, T. (2019). Assessing Industry 4.0 Readiness in Manufacturing: Evidence from the European Union. Computers in Industry, 107, 22-32. [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M. (1996). From brand values to customer value. Journal of Marketing Practice: Applied Marketing Science, 2(1), 55-66. [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M., & Lee, H. (2004). Mitigating supply chain risk through improved confidence. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 34(5), 388-396. [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M., & Peck, H. (2004). Building the Resilient Supply Chain. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 15(2), 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Cimini, C., Boffelli, A., Lagorio, A., Kalchschmidt, M., & Pinto, R. (2021). How do industry 4.0 technologies influence organisational change? An empirical analysis of Italian SMEs. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 32(3), 695-721. [CrossRef]

- Consultancy.eu. (2020). How Industry 4.0 is making supply chains more agile and flexible. Retrieved on May 18, 2022 from https://www.consultancy.eu/news/4538/how-industry- 40-is-making-supply-chains-more-agile-and-flexible.

- Cook, D.J., Mulrow, C.D., & Haynes, R.B. (1997). Systematic reviews: synthesis of best evidence for clinical decisions. Ann Intern Med, 126(5), 376 – 380. 10.7326/0003-4819-126-5-199703010-00006. PMID: 9054282.

- Cousens, A., Szwejczewski, M., & Sweeney, M. (2009). A process for managing manufacturing flexibility. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 29(4), 357- 385. [CrossRef]

- D’Aveni, R. (2015). The 3-D Printing Revolution. Harvard Business Review, 2015(May), 40-48. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2015/05/the-3-d-printing-revolution.

- Dalenogare, L. S., Benitez, G. B., Ayala, N. F., & Frank, A. G. (2018). The expected contribution of Industry 4.0 technologies for industrial performance. International Journal of Production Economics, 204, 383-394. [CrossRef]

- Dani, S. (2010). Managing Risk in Virtual Enterprise Networks. In Managing Risk in Virtual Enterprise Networks (pp. 72-91). [CrossRef]

- Davis, T. (1993). Effective Supply Chain Management. MIT Sloan Management Review, 34(4), 35–46. Retrieved from https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/effective-supply-chain- management/.

- De Toni, A., & Tonchia, S. (1998). Manufacturing flexibility: A literature review. International Journal of Production Research, 36(6), 1587-1617. [CrossRef]

- Demetriou, G. A. (2011). Mobile Robotics in Education and Research. In Mobile Robots - Current Trends. [CrossRef]

- Dess, G.G., & Picken, J. (2000). Changing roles: leadership in the 21st century. Organizational Dynamics, 28, pp. 18 – 34. [CrossRef]

- Durach, C. F., Wiengarten, F., & Choi, T. Y. (2020). Supplier–supplier coopetition and supply chain disruption: first-tier supplier resilience in the tetradic context. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 40(7/8), 1041-1065. [CrossRef]

- Enke, J., Glass, R., Kreß, A., Hambach, J., Tisch, M., & Metternich, J. (2018). Industry 4.0 – Competencies for a modern production system. Procedia Manufacturing, 23, 267-272. [CrossRef]

- Eyers, D., & Dotchev, K. (2010). Technology review for mass customisation using rapid manufacturing. Assembly Automation, 30(1), 39-46. [CrossRef]

- Fatorachian, H., & Kazemi, H. (2018). A critical investigation of Industry 4.0 in manufacturing: theoretical operationalisation framework. Production Planning & Control, 29(8), 633-644. [CrossRef]

- Fink, A. (1998). Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From Paper to the Internet. SAGE publications, pp.280, ISBN 0761909052. Gallagher, K. (2014). Print-on-Demand: New Models and Value Creation. Publishing Research Quarterly, 30(2), 244-248. [CrossRef]

- Gamache, S., Abdul-Nour, G., & Baril, C. (2020). Evaluation of the influence parameters of Industry 4.0 and their impact on the Quebec manufacturing SMEs: The first findings. Cogent Engineering, 7(1), 1771818. [CrossRef]

- Gao, J., Barzel, B., & Barabási, A.-L. (2016). Universal resilience patterns in complex networks. Nature, 530(7590), 307-312. [CrossRef]

- Gerwin, D. (1987). An Agenda for Research on the Flexibility of Manufacturing Processes. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 7(1), 38-49. [CrossRef]

- Ghadge, A., Dani, S., & Kalawsky, R. (2012). Supply chain risk management: present and future scope. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 23(3), 313-339. [CrossRef]

- Ghadge, A., Karantoni, G., Chaudhuri, A., & Srinivasan, A. (2018). Impact of additive manufacturing on aircraft supply chain performance. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 29(5), 846-865. [CrossRef]

- Ghadge, A., Weiß, M., Caldwell, N. D., & Wilding, R. (2019). Managing cyber risk in supply chains: a review and research agenda. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 25(2), 223-240. [CrossRef]

- Ghobakhloo, M. (2018). The future of manufacturing industry: a strategic roadmap toward Industry 4.0. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 29(6), 910-936. [CrossRef]

- Ghobakhloo, M. (2020). Industry 4.0, digitization, and opportunities for sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production, 252, 119869. [CrossRef]

- Ghobakhloo, M., & Ching, N. T. (2019). Adoption of digital technologies of smart manufacturing in SMEs. Journal of Industrial Information Integration, 16, 100107. [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, A. (2016). Smart Factories. In Industry 4.0: The Industrial Internet of Things (pp. 217- 230). Berkeley, CA: Apress. [CrossRef]

- Ginsberg, A., & Venkatraman, N. (1985). “Contingency perspective of organizational strategy: a critical review of the empirical research”. Administrative science quarterly, 86, pp. 513 – 524.

- Goldman, S. L. (1995). Agile competitors and virtual organizations. Strategies for enriching the customer. Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York, The University of California, 414 pp. ISBN : 0442019033 .

- Gunasekaran, A., & Ngai, E. W. T. (2005). Build-to-order supply chain management: a literature review and framework for development. Journal of Operations Management, 23(5), 423-451. [CrossRef]

- Gunasekaran, A., Subramanian, N., & Tiwari, M. K. (2016). Information technology governance in Internet of Things supply chain networks. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(7). [CrossRef]

- Gurtu, A. (2019). The Strategy of Combining Products and Services: A Literature Review. Services Marketing Quarterly, 40(1), 82-106. [CrossRef]

- Gurtu, A., & Johny, J. (2019). Potential of blockchain technology in supply chain management: a literature review. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 49(9), 881-900. [CrossRef]

- Gurtu, A., & Johny, J. (2021). Supply Chain Risk Management: Literature Review. Risks, 9(1), 16. [CrossRef]

- Gurtu, A., Searcy, C., & Jaber, M. Y. (2015). An analysis of keywords used in the literature on green supply chain management. Management Research Review, 38(2), 166-194. [CrossRef]

- Han, H., & Trimi, S. (2022). Towards a data science platform for improving SME collaboration through Industry 4.0 technologies. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 174. [CrossRef]

- Heng, S. (2014). Industry 4.0: Upgrading of Germany’s Industrial Capabilities on the Horizon. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=2656608.

- Hero, F. (2021), Industry 4.0: A Key Enabler of Resilient Supply Chains. Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/sap/2021/04/12/industrial-i0t-the-key-component-to-a- resilient-supply-chain/.

- Huang, C.-J., Talla Chicoma, E. D., & Huang, Y.-H. (2019), Evaluating the Factors that are Affecting the Implementation of Industry 4.0 Technologies in Manufacturing MSMEs, the Case of Peru. Processes, 7(3), 161. Retrieved from https://www.mdpi.com/2227- 9717/7/3/161.

- Ivanov, D., & Sokolov, B. (2012). The inter-disciplinary modelling of supply chains in the context of collaborative multi-structural cyber-physical networks. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 23(8), 976-997. [CrossRef]

- Jazdi, N. (2014). Cyber-physical systems in the context of Industry 4.0. Paper presented at the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Automation, Quality and Testing, Robotics held on 22 – 24 May 2014, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, pp. 1 – 4. [CrossRef]

- Jede, A., & Teuteberg, F. (2015). Integrating cloud computing in supply chain processes. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 28(6), 872-904. [CrossRef]

- Jereb, B., Cvahte, T., & Rosi, B. (2012). Mastering supply chain risks. Serbian Journal of Management, 7(2), 271-285. [CrossRef]

- Jüttner, U., Peck, H., & Christopher, M. (2010). Supply chain risk management: outlining an agenda for future research. International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications, 6(4), 197-210. [CrossRef]

- Kache, F., & Seuring, S. (2017). Challenges and opportunities of digital information at the intersection of Big Data Analytics and supply chain management. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 37(1), 10-36. [CrossRef]

- Kayikci, Y., Subramanian, N., Dora, M., & Bhatia, M. S. (2020). Food supply chain in the era of Industry 4.0: blockchain technology implementation opportunities and impediments from the perspective of people, process, performance, and technology. Production Planning & Control, 33(2-3), 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Kerin, M., & Pham, D. T. (2019). A review of emerging Industry 4.0 technologies in remanufacturing, Journal of Cleaner Production, 237, 117805. [CrossRef]

- Ketchen, D. J., & Craighead, C. W. (2020). Research at the Intersection of Entrepreneurship, Supply Chain Management, and Strategic Management: Opportunities Highlighted by COVID-19. Journal of Management, 46(8), 1330-1341. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N., Kumar, G., & Singh, R. K. (2021). Big data analytics application for sustainable manufacturing operations: analysis of strategic factors. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy, 23(3), 965-989. [CrossRef]

- Lasi, H., Fettke, P., Kemper, H.-G., Feld, T., & Hoffmann, M. (2014). Industry 4.0. Wirtschaftsinformatik, 56(4), 261-264. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. L. (2002), Aligning Supply Chain Strategies with Product Uncertainties. California Management Review, 44(3), 105-119. [CrossRef]

- Leong, G. K., Snyder, D. L., & Ward, P. T. (1990). Research in the process and content of manufacturing strategy. Omega, 18(2), 109-122. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Li, D., Wan, J., Vasilakos, A. V., Lai, C.-F., & Wang, S. (2017). A review of industrial wireless networks in the context of Industry 4.0. Wireless Networks, 23(1), 23-41. [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y., Deschamps, F., Loures, E. d. F. R., & Ramos, L. F. P. (2017). Past, present and future of Industry 4.0 - a systematic literature review and research agenda proposal. International Journal of Production Research, 55(12), 3609-3629. [CrossRef]

- Lichtblau, K., Stuch, V., Bertenrath, R., Blum, R., Bleider, M., & Millack, A (2016). IMPLUS, Industry 4.0 readiness, VDMA. Digitalization & Industry 4.0 - vdma.org - VDMA Retrieved on 14 June, 2025.

- Lin, C.-Y., & Jung, C. (2011). Influences of individual, organisational and environmental factors on technological innovation in Taiwan’s logistics industry. Chang Jung University, Taiwan.

- MacCarthy, B. L., Blome, C., Olhager, J., Srai, J. S., & Zhao, X. (2016). Supply chain evolution – theory, concepts and science. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 36(12), 1696-1718. [CrossRef]

- Manavalan, E., & Jayakrishna, K. (2019). A review of the Internet of Things (IoT) embedded sustainable supply chain for Industry 4.0 requirements. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 127, 925-953. [CrossRef]

- Manuj, I., & Mentzer, J. T. (2008). Global supply chain risk management strategies. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 38(3), 192-223. [CrossRef]

- Meredith, J. (1993). “Theory Building through Conceptual Methods,” International Journal of Operations & Production Management, Vol. 13, No.5, pp. 3 – 11. [CrossRef]

- Micheli, G. J. L., Cagno, E., & Zorzini, M. (2008). Supply risk management vs supplier selection to manage the supply risk in the EPC supply chain. Management Research News, 31(11), 846-866. [CrossRef]

- Miller, K. D. (1992). A Framework for Integrated Risk Management in International Business. Journal of International Business Studies, 23(2), 311-331. DOI:DOI: 10.1057/palgrave.jibs0270.

- Mittal, S., Khan, M. A., Romero, D., & Wuest, T. (2018). A critical review of smart manufacturing & Industry 4.0 maturity models: Implications for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Journal of Manufacturing Systems, 49, 194–214. [CrossRef]

- Neal, A. D., Sharpe, R. G., Conway, P. P., & West, A. A. (2019). smaRTI—A cyber-physical intelligent container for Industry 4.0 manufacturing. Journal of Manufacturing Systems, 52, 63-75. [CrossRef]

- Oesterreich, T. D., & Teuteberg, F. (2016). Understanding the implications of digitisation and automation in the context of Industry 4.0: A triangulation approach and elements of a research agenda for the construction industry. Computers in Industry, 83, 121-139. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S., Singh, R. K., & Gunasekaran, A. (2021). Supply chain risks in Industry 4.0 environment: review and analysis framework. Production Planning & Control, 1-28. [CrossRef]

- Papert, M., & Pflaum, A. (2017). Development of an Ecosystem Model for the Realization of Internet of Things (IoT) Services in Supply Chain Management. Electronic Markets, 27(2), 175-189. [CrossRef]

- Partanen, J., & Holmström, J. (2014). Digital manufacturing-driven transformations of service supply chains for complex products. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 19(4), 421-430. [CrossRef]

- Pettit, T. J., Croxton, K. L., & Fiksel, J. (2013). Ensuring Supply Chain Resilience: Development and Implementation of an Assessment Tool. Journal of Business Logistics, 34(1), 46-76. [CrossRef]

- Pittaway, L., Robertson, M., Munir, K., Denyer, D., & Neely, A. (2004). “Networking and innovation: a systematic review of the evidence”. 5-6 (3-4), pp. 137 – 168. [CrossRef]

- Power, D. (2005). Supply chain management integration and implementation: a literature review. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 10(4), 252-263. [CrossRef]

- Prater, E. (2005). A framework for understanding the interaction of uncertainty and information systems on supply chains. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 35(7), 524-539. [CrossRef]

- Radenkovic, D., Solouk, A., & Seifalian, A. (2016). Personalized development of human organs using 3D printing technology. Med Hypotheses, 87, 30-33. [CrossRef]

- Ralston, P., & Blackhurst, J. (2020). Industry 4.0 and resilience in the supply chain: a driver of capability enhancement or capability loss? International Journal of Production Research, 58(16), 5006-5019. [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishna, S., Ngowi, A., Jager, H. D., & Awuzie, B. O. (2020). Emerging Industrial Revolution: Symbiosis of Industry 4.0 and Circular Economy: The Role of Universities. Science, Technology and Society, 25(3), 505-525. [CrossRef]

- Rauch, E. (2020). Industry 4.0+: The Next Level of Intelligent and Self-optimizing Factories. 3rd International Conference on Design, Simulation, Manufacturing. The Innovation Exchange, Springer Cham. [CrossRef]

- Reischauer, G. (2018). Industry 4.0 as policy-driven discourse to institutionalize innovation systems in manufacturing. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 132, 26-33. [CrossRef]

- Richards, C. W. (1996). Agile manufacturing: beyond lean? Production and Inventory Management Journal, 37(2), 60-64.

- Rostow, W. W. (2019). Essays on a Half Century. New York: Routledge. ISBN:9780429036750. [CrossRef]

- Russo, A. (2020). Recession and Automation Changes Our Future of Work, But there are Jobs Coming. World Economic Forum. Retrieved on 14 June, 2025. https://www.weforum.org/press/2020/10/recession-and-automation-changes-our-future-of-work-but-there-are-jobs-coming-report-says-52c5162fce/ .

- Sanchez Rodrigues, V., Stantchev, D., Potter, A., Naim, M., & Whiteing, A. (2008). Establishing a transport operation focused uncertainty model for the supply chain. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 38(5), 388-411. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Rodrigues, V., Potter, A., & Naim, M. M. (2010). Evaluating the causes of uncertainty in logistics operations. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 21(1), 45-64. [CrossRef]

- Santos, R. C., & Martinho, J. L. (2019). An Industry 4.0 maturity model proposal. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 31(5), 1023-1043. [CrossRef]

- Sarvari, P. A., Ustundag, A., Cevikcan, E., Kaya, I., & Cebi, S. (2018). Technology Roadmap for Industry 4.0. In Industry 4.0: Managing The Digital Transformation (pp. 95-103). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Seuring, S., & Müller, M. (2008). From a literature review to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management. Journal of Cleaner Production, 16(15), 1699-1710. [CrossRef]

- Sheffi, Y., & Rice Jr., J. B. (2005). A Supply Chain View of the Resilient Enterprise. MIT Sloan Management Review, 47(1), 41.

- Shrouf, F., Ordieres, J., & Miragliotta, G. (2014). Smart factories in Industry 4.0: A review of the concept and of energy management approached in production based on the Internet of Things paradigm. Paper presented at the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management, Selangor, Malaysia, pp. 697 – 701. [CrossRef]

- Simangunsong, E., Hendry, L. C., & Stevenson, M. (2012). Supply-chain uncertainty: a review and theoretical foundation for future research. International Journal of Production Research, 50(16), 4493-4523. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R. K., & Gurtu, A. (2021). Embracing advanced manufacturing technologies for performance improvement: an empirical study. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 29(6), 1979-1998. [CrossRef]

- Sommer, L. (2015). Industrial revolution - industry 4.0: Are German manufacturing SMEs the first victims of this revolution? Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management, 8(5), 1512- 1532. [CrossRef]

- Sonar, H., Mukherjee, A., Gunasekaran, A., & Singh, R. K. (2022). Sustainable supply chain management of automotive sector in context to the circular economy: A strategic framework. Business Strategy and the Environment, 31(7), 3635-3648. [CrossRef]

- Strandhagen, J. W., Alfnes, E., Strandhagen, J. O., & Vallandingham, L. R. (2017). The fit of Industry 4.0 applications in manufacturing logistics: a multiple case study. Advances in Manufacturing, 5(4), 344-358. [CrossRef]

- Tao, F., Zhang, H., Liu, A., & Nee, A. Y. C. (2019). Digital Twin in Industry: State-of-the-Art. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, 15(4), 2405-2415. [CrossRef]

- Thomé, A. M. T., Scavarda, L. F., & Scavarda, A. J. (2016). Conducting systematic literature review in operations management. Production Planning & Control, 27(5), 408-420. [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.-H., Park, H.-S., Nguyen, Q.-V., & Hoang, T.-D. (2019). Development of a Smart Cyber- Physical Manufacturing System in the Industry 4.0 Context. Applied Sciences, 9(16), 3325. [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D., Denyer, D., & Smart, P. (2003). “Towards a methodology for developing evidence – informed management knowledge by means of systematic review”. British Journal of Management, 14(3), pp. 207 – 222. [CrossRef]

- Tushman, M.L., & O’Reilly, C.A. (1996). Ambidextrous organizations: managing evolutionary and revolutionary change. California Management Review, 38, pp. 8-30. [CrossRef]

- Vendrell-Herrero, F., Bustinza, O. F., Parry, G., & Georgantzis, N. (2017). Servitization, digitization and supply chain interdependency. Industrial Marketing Management, 60, 69-81. [CrossRef]

- Vogel-Heuser, B., & Hess, D. (2016). Guest Editorial Industry 4.0–Prerequisites and Visions. IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering, 13(2), 411-413. [CrossRef]

- Wagire, A. A., Rathore, A. P. S., & Jain, R. (2019). Analysis and synthesis of Industry 4.0 research landscape. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 31(1), 31–51. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. (2018). Impacts of supply chain uncertainty and risk on the logistics performance. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 30(3), 689-704. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., Wan, J., Zhang, D., Li, D., & Zhang, C. (2016). Towards smart factory for industry 4.0: a self-organized multi-agent system with big data-based feedback and coordination. Computer Networks, 101, 158-168. [CrossRef]

- Weyer, S., Schmitt, M., Ohmer, M., & Gorecky, D. (2015). Towards Industry 4.0 - Standardization as the crucial challenge for highly modular, multi-vendor production systems. IFAC- PapersOnLine, 48(3), 579-584. [CrossRef]

- Wieland, A. (2020). Dancing the Supply Chain: Toward Transformative Supply Chain Management. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 57(1), 58-73. [CrossRef]

- Wieland, A., & Wallenburg, C. M. (2013). The influence of relational competencies on supply chain resilience: a relational view. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 43(4), 300-320. [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum, (2022). What is “Industry 4.0” and What will it mean for developing countries?. Retrieved on 14 June 2025. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2022/04/what-is-industry-4-0-and-could-developing-countries-get-left-behind/ .

- Wu, L., Yue, X., Jin, A., & Yen, D. C. (2016). Smart supply chain management: a review and implications for future research. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 27(2), 395-417. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R. Y., Xu, X., Klotz, E., & Newman, S. T. (2017). Intelligent Manufacturing in the Context of Industry 4.0: A Review, Engineering, 3(5), 616-630. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.