1. Introduction

Degenerative retinal diseases precipitated by diabetes (diabetic retinopathy), premature birth (retinopathy of prematurity), increased intraocular pressure (glaucoma), and aging (age-related macular degeneration) represent leading causes of visual loss and blindness worldwide [

1,

2]. Despite significant advances in understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying these conditions, effective early interventions remain limited. Current therapies-including anti-VEGF agents, corticosteroids, laser photocoagulation, and surgical procedures-have improved outcomes for many patients but are often associated with limitations such as incomplete efficacy, recurrence of disease, adverse effects, and the need for repeated invasive treatments [

3,

4,

5].

For example, anti-VEGF therapy has revolutionized the management of neovascular retinal diseases but requires frequent intravitreal injections and may not be effective in all patients [

3,

4,

5]. Corticosteroids, while potent anti-inflammatory agents, carry risks of cataract formation and elevated intraocular pressure. Laser therapy can cause collateral damage to healthy retinal tissue, and surgical interventions are typically reserved for advanced stages of disease [

3,

4,

5].

Moreover, the posterior segment of the eye remains a challenging target for drug delivery due to anatomical and physiological barriers [

6,

7,

8]. Non-invasive yet effective delivery systems are still under development, and many promising compounds fail to reach therapeutic concentrations in retinal tissues when administered systemically or topically [

6,

7,

8].

Given these limitations, there is a pressing need for novel therapeutic strategies that are both effective and minimally invasive. One such emerging approach is the use of carbon monoxide (CO) therapy. Traditionally viewed as a toxic gas, CO has demonstrated cytoprotective properties at low concentrations, including anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, and vasodilatory effects. This review explores the therapeutic potential of CO and heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) induction in ocular diseases, summarizing current evidence and discussing delivery strategies, safety considerations, and future directions.

CO is classically considered a toxic gas. This is related to its well-known property of binding with high affinity to hemoglobin to generate carboxyhemoglobin (COHb). COHb decreases hemoglobin’s ability to carry oxygen, contributing to hypoxemia, tissue hypoxia, and, if in high concentrations not addressed rapidly, death. CO is also generated physiologically in the body as a byproduct of heme degradation in a reaction catalyzed by heme oxygenase enzymes. Heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) is essential to endogenous CO production. Several reports have highlighted the benefits of enhanced HO-1 expression and activity in a variety of disease model systems including in animal models of intestinal [

9,

10,

11], hepatic [

12,

13,

14], lung [

15,

16,

17], renal [

18,

19,

20], cardiac [

21,

22,

23], and ocular ischemic reperfusion injury [

24,

25,

26]. However, the detailed mechanisms to explain these effects, particularly whether or how they relate directly or indirectly to the modulation of CO levels, are unclear.

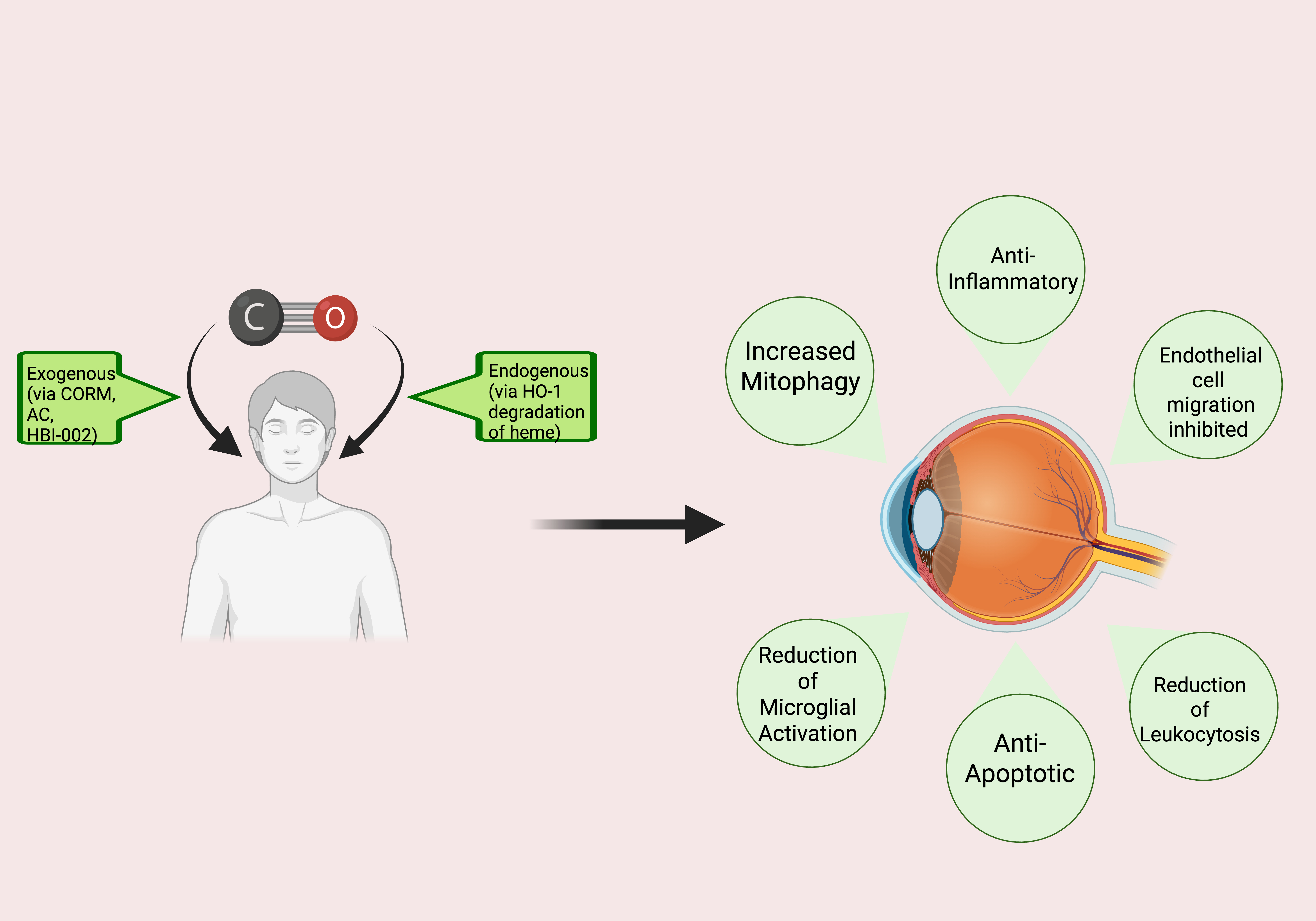

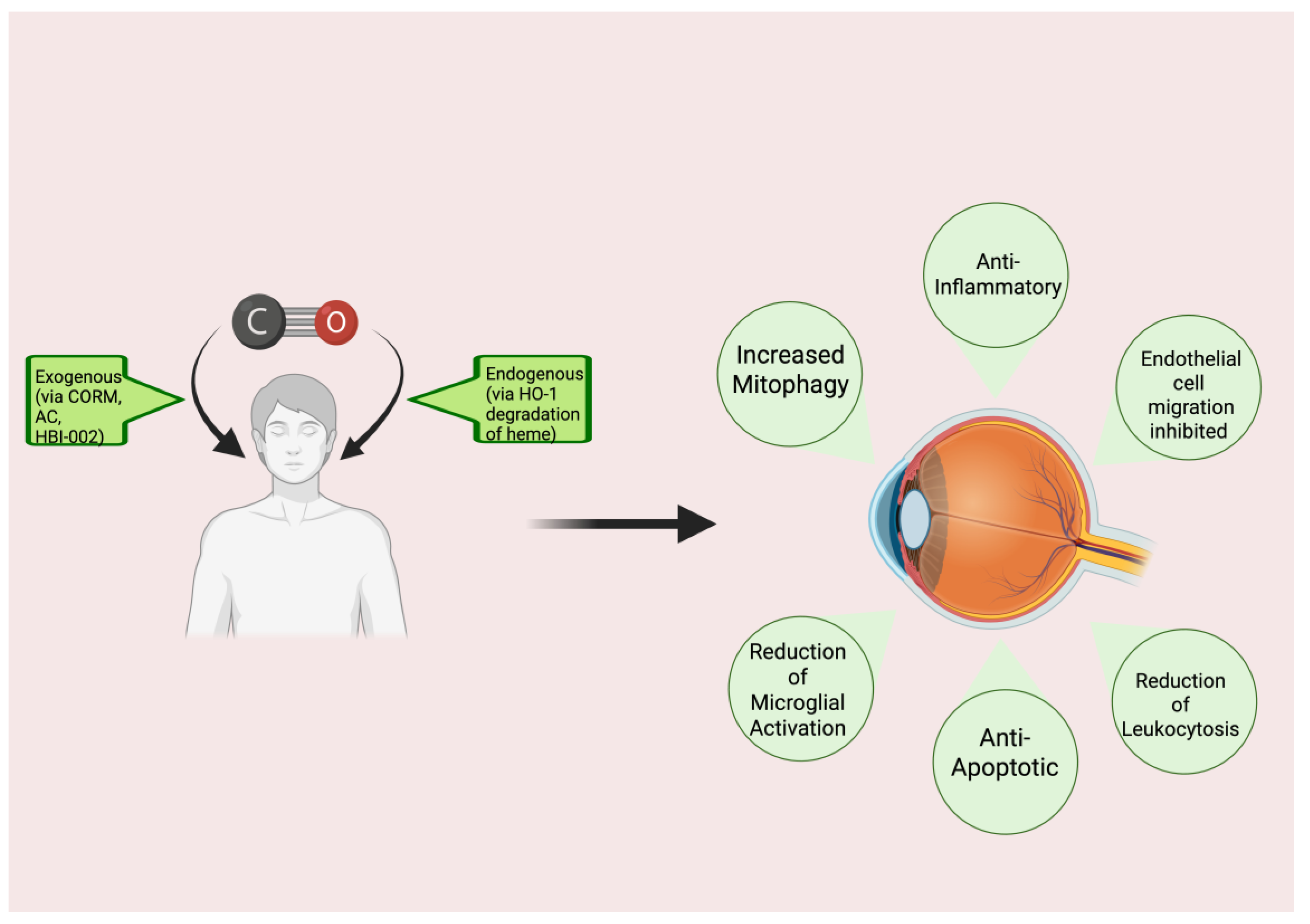

An increasing number of studies expose the robust and direct benefits of CO in a wide variety of clinical and pre-clinical scenarios, sparking increased interest in CO therapy. This fascinating area of research showcases CO in a light that contrasts starkly with traditional views. The current review focuses on the potential therapeutic effects of CO that could be realized in the eye (

Figure 1), providing information on the mechanism(s) of action, available pre-clinical and clinical evidence relevant to the utility of CO in retinal diseases, delivery methods, and safety considerations, as well as prospects and future directions.

2. Mechanisms of Action for Low-Dose CO

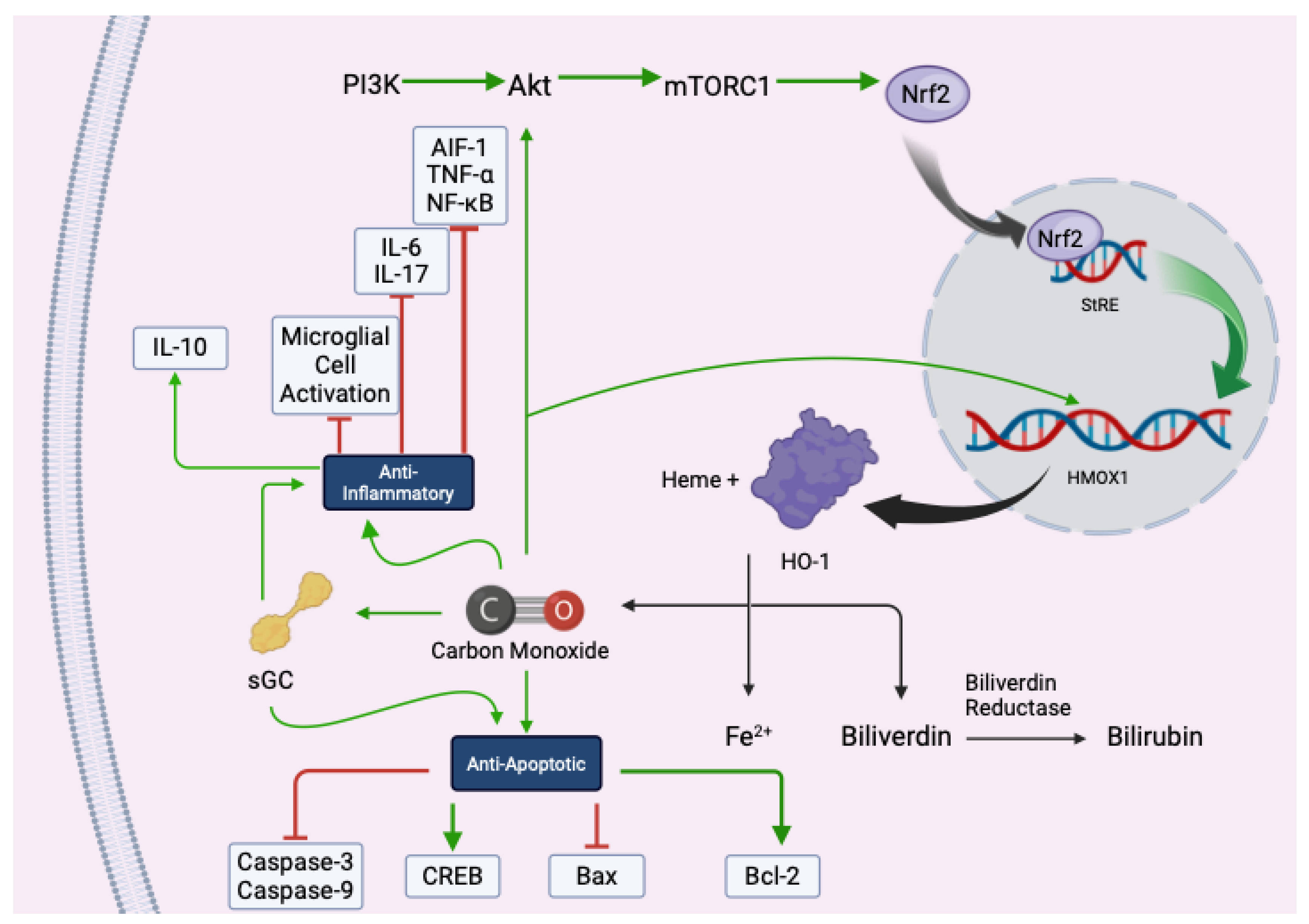

CO is produced during the enzymatic degradation of heme by heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), a stress-inducible enzyme that responds to various physiological insults. These effects are tightly regulated and dose-dependent, with low-dose CO triggering beneficial responses without inducing toxicity.

The cytoprotective actions of CO begin with the induction of HO-1, which catalyzes the breakdown of heme into biliverdin, free iron (Fe²⁺), and CO. Biliverdin is subsequently converted to bilirubin by biliverdin reductase, and both products contribute to the cellular antioxidant defense system [

27] (

Figure 2). HO-1 expression is regulated by the transcription factor Nrf2, which is activated via the PI3K/Akt/mTORC1 signaling pathway. Upon activation, Nrf2 translocates to the nucleus and binds to antioxidant response elements (AREs), promoting the transcription of HMOX1 and other genes involved in cytoprotection [

28,

29]. This pathway has been extensively studied in models of ischemia-reperfusion injury, neurodegeneration, and inflammation, underscoring its central role in CO-mediated cellular resilience.

CO also plays a critical role in modulating inflammation. It suppresses the activation of immune cells such as microglia and macrophages, leading to a reduction in pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 [

30,

31,

32]. Simultaneously, CO enhances the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines like IL-10, promoting the resolution of inflammation [

33]. In the central nervous system, CO downregulates allograft inflammatory factor-1 (AIF-1), a marker of microglial activation, thereby mitigating neuroinflammatory responses [

34]. These effects are mediated through mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling cascades, particularly p38 MAPK and ERK1/2, which regulate cytokine transcription and immune cell behavior (

Figure 2). Studies using inhaled-CO and CO-releasing molecules (CORMs) have confirmed these anti-inflammatory effects in various disease models, including sepsis, lung injury, and transplant rejection [

35].

In addition to its immunomodulatory properties, CO enhances antioxidant defenses and maintains redox homeostasis [

36]. Through HO-1 induction, CO increases intracellular levels of bilirubin, a potent scavenger of reactive oxygen species (ROS). It also modulates the activity of key antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, and glutathione peroxidase, thereby reducing oxidative damage [

36,

37]. CO has been shown to inhibit NADPH oxidase, a major source of superoxide in inflammatory cells, further limiting ROS production. Moreover, CO may interact with reactive nitrogen species (RNS) to form carbonate radicals, which modulate redox-sensitive signaling pathways and prevent excessive oxidative injury [

36]. These mechanisms have been validated in cardiovascular, renal, and neuroprotective models, demonstrating the role of CO in preserving cellular integrity under stress.

CO’s anti-apoptotic effects are equally significant. It activates soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC), leading to increased cyclic GMP (cGMP) levels and subsequent activation of cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB), a transcription factor that promotes cell survival [

38] (

Figure 2). CO also influences the expression of Bcl-2 family proteins, inhibiting pro-apoptotic Bax and enhancing anti-apoptotic Bcl-2, thereby stabilizing mitochondrial membranes and preventing cytochrome c release [

39,

40]. Furthermore, CO inhibits the activation of caspase-3 and caspase-9, key mediators of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway [

40,

41]. These protective effects have been observed in models of ischemia, neurodegeneration, and organ transplantation, where CO treatment significantly reduced tissue damage and improved functional outcomes.

3. Evidence from Preclinical Ocular Disease Studies

3.1. Animal Models

The benefits of CO therapy have also been realized in the eye, where the impact of CO therapy has mainly been cytoprotective. Indeed, many ocular disease models have been used to study the effects of CO. The most common model is the rodent model of ocular ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI). IRI occurs when the blood supply to a tissue, such as the retina, is inadequate; thus, the metabolic and oxygen needs of the tissue are not met [

42,

43]. Such ischemia can lead to angiogenesis. In the retina, the new vessels that form in response to tissue ischemia are fragile and prone to hemorrhage in the vitreous. The reperfusion of previously under-perfused tissue areas can additionally yield further damage due to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and pro-inflammatory molecules [

44,

45,

46]. Further, if left untreated, these new vascular tufts can lead to tractional retinal detachment and vision loss [

42,

43,

47]. Tissue ischemia occurs commonly in eye diseases such as glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, retinopathy of prematurity, and retinal vasculature occlusions [

43,

48,

49]; thus, information gleaned from the ocular IRI model is highly relevant. Ulbrich et al., using a rat model of retinal IRI, found that exogenously delivered CO reduced expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-6 (IL-6); this effect of CO, mediated by soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC), played a key role in protecting retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) from IRI-induced cell death [

50,

51]. Postconditioning with inhaled CO (250 ppm) in a rat IRI model reduced activation of microglia-neuroglia that can secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines upon activation. Moreover, retinal thickness was preserved in the CO-treated group compared to the IRI + air group [

52]. Additional research showed that CO, given post-IRI in a rat retina model, reduces allograft inflammatory factor 1 (AIF-1) expression, a protein implicated in microglial activation; thus, inflammation was reduced while RGCs were protected [

53]. These findings were replicated in additional studies, [

54], [

52], which showed that CO protected RGCs from IRI via reduced expression of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), an inflammatory mediator cytokine that is associated with neuronal cell death, [

53]. Schallner et al. found that postconditioning with 250 ppm inhaled CO reduced NF-kB expression and DNA binding in their rat model of retinal IRI; thus, inflammation and RGC death were reduced [

55]. Preconditioning with 250 ppm inhaled CO in a rat model of retinal IRI has been shown to increase heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) expression, a cytoprotective chaperone [

56]. Although the eye was not being studied, Beckman et al. noted increased phosphorylation of Akt as well as increased levels of HO-1 expression after treatment with inhaled CO (250 ppm) in a mouse model of Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) [

57]. Since retinopathy secondary to SCD is a common complication, this study further supports the benefit of CO in increasing levels of Akt and HO-1 and thereby protecting against retinal damage.

The efficacy of CO therapy has also been evaluated in models of optic nerve crush (ONC) [

55,

57] and ocular hypertension [

58], models that replicate key processes in human glaucoma and traumatic optic neuropathy, and in the rat model of autoimmune uveitis, a model consistent with robust general inflammation in the posterior segment [

59]. In these models, CO was found to reduce intraocular pressure and related ocular hypertension, and limit inflammation through the reduction of interleukin-17 (IL-17) expression and increased expression of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, resulting in improved histological scores.

Table 1 highlights the findings of these and other preclinical studies on the use of CO delivery to improve various ocular disease conditions.

CO, like HO-1, has extensive anti-apoptotic effects. Much evidence reveals that CO protects RGCs from apoptosis via suppression of caspase-3 [

50,

51,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61] and caspase-9 [

51]. The use of CORMs [

60] in combination with postconditioning with 250 ppm of inhaled CO [

59] reduced expression of Bax and increased expression of Bcl-2 in rat models of retinal IRI. Schallner et al. reduced Bax expression in their rat retinal IRI model via sGC stimulation using CORMs; however, no significant increase in Bcl-2 expression was noted [

61]. The difference in the effect of CORMs on Bcl-2 expression could be due to the timing of treatment. Schallner et al. preconditioned rat retinas with CORMs prior to IRI [

61], whereas Ulbrich et al. treated rat retinas with post-IRI [

60]. In any case, this CO therapy was protective of RGCs in both studies [

60,

61]. Moreover, preconditioning with inhaled CO (250 ppm) in a rat retinal IRI model increased the activity of cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB), a transcription factor implicated in neuronal plasticity, growth, and survival [

58]. The effects of CO on MAPKs have been controversial. For example, evidence suggests that CO stimulates p38 MAPK expression in models of retinal IRI to exert anti-apoptotic effects [

57,

58,

60]. In contrast, Schallner et al. noted less apoptosis secondary to decreased phosphorylation of p38 MAPK with inhaled CO (250 ppm) given post-IRI in a rat model [

59]. Several researchers noted that the timing of CO administration could differentially affect the expression of p38 MAPK [

58,

59]. In studies that showed increased p38MAPK expression, CO treatment, whether via CORM or inhalation, was preconditioned [

58] or administered quickly (< 3 hours) [

57,

60] after IRI. However, administration of 250 ppm inhaled CO immediately after, 1.5 hours, or 3 hours post-IRI resulted in decreased p38 MAPK activation [

59]. Research on CO’s effect on ERK1/2 MAPK has proven contradictory as well. In their rat model of IRI, Schallner et al. noted increased ERK1/2 phosphorylation after postconditioning with 250 ppm of inhaled CO; however, inhibition of ERK1/2 did not abrogate CO’s protective effects on RGCs [

59]. Ulbrich et al., using CORM ALF-186 in a rat model of retinal IRI, found that CO administration reduced ERK1/2 phosphorylation [

60].

3.2. Cellular Studies

The aforementioned studies demonstrate the controversy that surrounds CO’s actions on MAPK signaling pathways. Such discrepancies highlight the need for future studies on the effects of CO on MAPKs. Although research on CO’s direct effects on HO-1 in an ocular context is lacking, accumulating evidence suggests that exogenously delivered CO can, in turn, increase HO-1 expression. Yang et al., in their study of STAT3 activation in bovine endothelial cells, discovered that CORM-derived CO increased HO-1 protein levels [

62]. Moreover, CO, whether inhaled or from CORMs, increases Nrf2 mRNA and subsequently HO-1 mRNA expression and enzyme activity [

63]. Further study in a mouse model of cerebral ischemia revealed that inhaled CO (post-conditioned, 250 ppm) aids Nrf2 translocation into the nucleus, resulting in increased HO-1 expression [

64]. Additional evidence from a study of CORM-treated rat pheochromocytoma cells suggests that CO increases phosphorylation of Akt; inhibition of PI3K decreased cell viability [

65]. Taken together, CO seems to induce HO-1 expression via a PI3K/Akt/Nrf2 pathway similar to that shown previously in

Figure 2 [

63,

64,

65]. Zuckerbraun et al., using a rat model of liver injury, suggested that CO stimulates iNOS, producing nitric oxide (NO) that then stimulates HO-1 [

66]. In contrast, Schallner et al. did note that inhaled CO treatment post-IRI in the rat retina resulted in decreased HO-1 mRNA and protein expression. However, they state that this is likely due to a CO-mediated decrease in oxidative stress; since oxidative stress can stimulate HO-1, removing it would naturally decrease HO-1 expression [

59]. In any case, further studies on how CO interacts with HO-1 in the eye are needed, as most studies on the topic deal with different organ systems. Thus, tissue differences in relation to CO modulation of HO-1 must be investigated.

In a blue light-induced injury model, CORM-2 and CORM-3 demonstrated cytoprotective and anti-inflammatory effects in ARPE-19 cells via NF-kB activation. Compared to CORM-3, CORM-2 was more efficient in increasing levels of GSH synthesis enzymes, resulting in stronger cytoprotective effects in RPE cells. Lastly, this study demonstrated that CORM-2 and CORM-3 inhibit migration in VEGF-induced endothelial cells. Rosignol et al. administered CO to induce mitophagy in transgenic mice that expressed a

mito-quality control (QC) reporter. This

mito-QC model system allowed for the quantification of mitophagy, which is cytoprotective against and a potential therapeutic target for glaucoma. CORM-A1 induced mitophagy in the retinal ganglion cell and outer nuclear layers [

67].

4. Clinical Evidence

Most clinical trials studying the therapeutic efficacy and safety of carbon monoxide are focused on treating respiratory disease using inhaled CO (

Table 2). As of right now, there is no therapy for the inflammation that occurs from smoking-related chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Researchers found that low-dose CO inhalation in patients with stable COPD was feasible and safe relative to the peak carboxyhemoglobin levels of 3.1-4.5%. CO inhalation also led to reduced sputum eosinophils and improved responsiveness to methacholine in patients with stable COPD. Their findings indicate that CO inhalation might have therapeutic effects in COPD [

68].

Several studies have looked at CO inhalation efficacy in treating acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), a prevalent disease for which there is no effective pharmacologic therapy. One study administered bronchoscopic instillation of endotoxin (LPS) in healthy volunteers to model a pulmonary inflammatory response. Although CO did not demonstrate significant anti-inflammatory effects in the pilot study, data analysis for the main study remains ongoing [NCT00094406]. Another study assessed the efficacy of inhaled CO to treat idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) in an ambulatory setting. Despite increases in COHb, CO treatment did not significantly raise matrix metalloproteinase-7 (MMP7), a biomarker in IPF. This study demonstrated that inhaled CO is well tolerated and can be safely administered in patients with IPF. However, there were no observed differences in physiologic measures, acute exacerbations, hospitalization, death, or patient-reported outcomes between the subjects treated with CO and the control group [

69].

One study conducted a dose escalation trial to determine the feasibility and safety of inhaled CO in patients with sepsis-induced ARDS. By utilizing a personalized inhaled CO dosing algorithm, researchers found that the Coburn-Forster-Kane (CFK) equation was highly accurate at predicting COHb levels, which would ensure COHb levels remain in the target range during future clinical trials [

70]. To further this research, an ongoing study is exploring the safety and accuracy of the same CFK equation algorithm to achieve COHb of 6-8% in mechanically ventilated patients with sepsis-induced ARDS [NCT04870125]. This clinical trial has progressed to Phase II to assess the efficacy of low-dose inhaled CO in mechanically ventilated patients with ARDS [NCT03799874].

An oral liquid CO drug product, HBI-002, is also being studied in the clinic. A Phase 1 clinical trial investigating HBI-002 in healthy adult subjects has been completed [NCT03926819]. In this open-label study, HBI-002 was administered to a total of 20 subjects in a single ascending dose phase followed by a multiple daily dose phase with daily dosing for 7 days. This study demonstrated appropriate safety, with no Serious Adverse Events and only Grade 1 Adverse Events, as well as dose-dependent pharmacokinetics. In addition, a Phase 2a clinical study of HBI-002 in subjects with SCD is ongoing [NCT06144749]. This study is an open-label, ascending multiple-dose study with once daily dosing for 14 days, assessing safety, pharmacokinetics, and proof-of-concept efficacy.

5. Delivery Methods

5.1. Inhalation Therapy

Of course, the worry with inhaled CO is the risk of CO poisoning. This is due to the displacement of oxygen (O

2) from hemoglobin (Hb) by CO, which has a much higher affinity for Hb than O

2 [

71,

72,

73]. In addition, CO bound to Hb increases Hb’s affinity for O

2, thus inhibiting O

2 release to the tissues [

71,

72,

73,

74]. These effects combine to result in tissue hypoxia [

73,

74]. A carboxyhemoglobin (COHb) level of 15 to 20% does not seem to have severe side effects; thus, this is presumed to be the threshold for human CO tolerance [

75]. More than ten human studies with inhaled CO have shown no adverse effects [

76]. Resch et al. found that inhaled CO increased retinal and choroidal blood flow in human volunteers after inhalation of 500 ppm CO for 1 hour. The maximum COHb level was 8.7%, but CO inhalation was well-tolerated, and no headaches or discomfort were reported [

77]. Inhaled CO (100 or 150 ppm) in a clinical trial with COPD patients was well-tolerated. Median COHb was less than 4% with both CO doses, [

78]. Ren et al. maintained 10% COHb via inhaled CO (0.4% CO in air) for 8 hours in human volunteers without adverse events [

79]. Inhaled CO, either 250 ppm for 2 hours or 500 ppm for 1 hour, was used in a human model of LPS-induced systemic inflammation; COHb levels did not exceed 8%, vital signs remained normal, and no adverse events were noted [

80]. In a recent study of interstitial pulmonary fibrosis patients, inhaled CO (100 to 200 ppm) produced maximum COHb levels of 2.24 to 3.82%. The CO treatment was well-tolerated, and no statistical difference in adverse events was noted between the control and CO-treated groups [

69]. Based on the above results, CO treatment to achieve low COHb levels is safe and well-tolerated by human subjects. However, human studies with inhaled CO typically fail to produce therapeutic results. Despite CO’s safety in human models, inhaled CO in human trials of COPD [

78], LPS-induced systemic inflammation [

80], and interstitial pulmonary fibrosis [

69] have failed to produce efficacious results. This could be due to underdosing. However, inhaled CO suffers from several disadvantages. Patient compliance is a substantial barrier for inhaled CO. Although inhaled drugs are accepted intraoperatively, there is substantial patient and healthcare provider resistance to inhaled drugs in a nonoperative setting. Dosing accuracy is another substantial issue. Although intraoperative dosing of gases can be well controlled due to the constant monitoring of blood gases and other measures, with nonoperative therapeutic gas dosing there is a substantial risk of a patient not breathing the correct dose, whether due to incorrectly used administration equipment (e.g., incorrectly applied breathing mask), variable inhalation (differences in breathing volume and rate during administration), poor compliance with duration of inhalation, or changes in lung function (e.g., decreased due to infection). Also, inhaled CO lacks specificity, as it is systemically distributed once it reaches the lungs; thus, it is difficult to control its absorption, distribution, and tissue targeting [

75,

81,

82]. Moreover, Hb can serve as a “trap” for inhaled CO. That is, when the CO is bound to Hb, it may be restricted from reaching the site of injury in target tissues [

83]. Additionally, CO leaks can be a risk to clinical staff and patients [

81].

5.2. Carbon Monoxide-Releasing Molecules (CORMs)

The use of CORMs as a therapeutic has been a fascinating area of research. Indeed, this treatment modality holds the potential for the use of CO as therapy without the downsides of inhaled CO. CORMs are molecules composed of a backbone that release CO under certain conditions and/or stimuli [

83]. CORMs are also known as CO prodrugs. The backbone moiety of CORMs can consist of a range of molecules including organometallic and organic molecules, and both large and small molecules, and CORMs have been designed to be dosed orally, intravenously, and through other routes of administration. In fact, CORMS have been designed such that oxidative environments, light, heat, pH changes, etc., can be used to liberate CO from these CORMs, making them attractive candidates for treatment in a variety of ocular diseases [

83]. An additional advantage of certain, non-oral CORMs that are tissue-targeted over inhaled CO is minimal COHb elevation with treatment due to the tissue specificity of these CORMs [

75,

83]. Also, since these targeted CORMs theoretically only release CO when the target tissue is reached, the liberated CO does not fall victim to the “Hb trap” [

75]. Perhaps the most attractive aspect of CORMs is the customization offered by the ancillary ligands attached to them; these can be used to “fine-tune” the stability, solubility, pharmacokinetics, and CO-releasing trigger of the CORM [

82,

83]. Indeed, certain CORMs have been used in animal models of ocular disease with positive results. For example, CORM-A1 had anti-inflammatory effects in a rat model of autoimmune uveitis [

53], while ALF-186 has been shown to reduce inflammation [

55,

57] and apoptosis [

57,

60,

61] in rat models of IRI. However, CORMs have their downsides as well. A key concern is the pharmacological, metabolic, and toxic characteristics of the CORM backbone after CO release [

75,

82,

83]. Organometallic CORMs are often made using a variety of transition metals, such as Cr, Mo, Mn, Re, Fe, and Ru [

83], all of which can present toxicology concerns. For example, ruthenium-based CORMs (e.g., CORM-2) have been shown to be cytotoxic, and evidence suggests that Mn is neurotoxic, so the fate of the CORM backbone warrants concern [

84]. At least in part due to these toxicity concerns, small molecule organometallic CORMs have thus far not been studied in the clinic.

The CORMs that have advanced farthest in development are large molecule organometallic CORMs, the PEGylated COHb drugs. These intravenous drugs typically consist of human or bovine cell-free COHb molecules to which polyethylene glycol (PEG) has been attached. Ten clinical trials have been completed with this class of CORM, including a total of 320 study subjects in both Phase 1 and 2 studies. Studies with these molecules, which have included a total of 320 subjects [

76], have reported a toxicology profile similar to that reported for other cell-free hemoglobin (Hb) products (also termed Hb-based oxygen carriers). Reported AEs include cardiovascular issues (hypertension, troponin I increase, and a few myocardial infarction occurrences) as well as hematuria. These AEs are attributed to the effects of circulating free Hb, heme, and ferric iron and/or scavenging of nitric oxide (NO) by the heme moiety [

85,

86]. The companies developing PEG-COHb drug products focused on acute use of these molecules, rather than chronic use, likely due to the impact of free Hb toxicity. At present, it does not appear that any of these molecules are advancing in development.

There is increasing interest in developing “CO in a pill”, a solid oral CO drug that enables local release in the GI system. The potential to dose orally would provide a substantial advantage over inhaled CO and non-oral CORMs as oral dosing is the preferred modality for patients, providing improved ease of administration and patient compliance. However, as with inhaled CO, oral CORMs present with the downside of systemic exposure. Although oral organometallic CORMs have been developed (e.g. CORM-401) [

87], to avoid the abovementioned toxicity of organometallic backbones, organic CORMs (also termed organic CO prodrugs) are also being developed, and drug product candidates have been developed with the goal of minimizing the absorption of the backbone after CO release[

88,

89]. A number of organic CORMs are in early stage development, for example oxalyl saccharin, which has been studied in initial pharmacokinetic studies in mice, and none so far has advanced to the clinic. [

90]

The advent of nanomaterials offers another solution to potential organometallic CORM backbone toxicity [

91]. These materials, which can be conjugated to the organometallic CORM, may reduce the metal toxicity of the backbone. In addition, nanomaterials can be used to increase the solubility, stability, CO payload, and specificity of organometallic CORMs [

91]. Thus, nanomaterials could enhance the therapeutic effects of organometallic CORMs while reducing any potential side effects.

5.3. Oral Liquids Containing CO

Another method of CO administration that holds great promise is that of liquid CO formulations. These CO therapeutics contain CO that is not chemically bound to any molecule, and are designed to circumvent the aforementioned cons of inhaled CO and CORMs. Additionally, oral delivery of the liquid formulation provides a platform for feasibility and compliance, given the preference for oral dosing by patients, especially for chronic administration and for the administration of a therapeutic outside of hospital settings. HBI-002, a liquid CO drug product developed by Hillhurst Biopharmaceuticals, has been shown to be effective, including reducing inflammation, in animal models of SCD [

92], Parkinson’s disease, [

93] and anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity [

94], among other areas . HBI-002 is currently undergoing clinical testing. A Phase 1 clinical trial (NCT03926819) to assess the safety and pharmacokinetics of HBI-002 in healthy volunteers was completed and showed no adverse events of clinical significance. In addition, a Phase 2a clinical trial [NCT 06144749] in subjects with SCD is currently enrolling, and a Phase 2a clinical trial [NCT07005180] in subjects with Parkinson’s disease is reported to begin soon.

6. Safety Considerations

6.1. Toxicity and Dosage

Studies have shown that COHb levels below 10% are generally well tolerated in humans, with minimal side effects such as headaches or discomfort. For inhaled CO, safe dosage ranges typically fall between 100 and 250 ppm, depending on the duration and frequency of exposure [

95]. Clinical trials in patients with COPD, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, and sepsis-induced ARDS, among other areas, have used these ranges with good tolerability. Monitoring COHb levels is essential to avoid toxicity. Blood gas machines with co-oximetry that directly measure COHb from venous blood samples are widely used and readily available, and, for inhaled CO, algorithms like the Coburn-Forster-Kane (CFK) equation have proven effective in indirectly predicting safe COHb levels with inhaled CO [

96]. Side effects are rare at therapeutic doses but may include mild hypoxia, especially in individuals with pre-existing respiratory conditions. The development of CORMs and oral liquid CO drug products targets improved safety profiles by carefully controlling CO dosing, minimizing systemic COHb elevation, and/or enhancing tissue specificity.

6.2. Regulatory and Ethical Issues

The regulatory landscape for CO therapy is evolving. CO is classified as a medical gas by the FDA and other regulatory agencies [

97], and is used widely in pulmonary function testing (diffusion capacity of the lungs). At the same time, the potential toxicity of CO at high exposure is well known. The clinical testing of CO has taken place under the auspices of various regulatory agencies, including the FDA, EMA, and others. Numerous Phase I and II trials have been allowed by these regulatory agencies to assess the safety and, in certain studies, efficacy of inhaled CO, CORMs, and oral liquid CO [

76] . As with the development of all drugs, ethical considerations center around the balance between therapeutic benefit and potential toxicity. Informed consent, rigorous safety monitoring, and transparent communication of risks are essential in clinical trials, as is careful ethical oversight. Additionally, as is required in drug development the potential for off-target effects and long-term consequences of the use of CO must be addressed through the appropriate preclinical and clinical evaluations.

7. Prospects and Future Directions

7.1. Potential for Broader Applications

CO therapy, initially explored for retinal ischemia-reperfusion injury, holds promise for a broader spectrum of ocular diseases. In glaucoma models, CO has demonstrated the ability to lower intraocular pressure and protect retinal ganglion cells from apoptosis and inflammation. Autoimmune uveitis models have benefited from CO’s immunomodulatory effects, including suppression of Th17 responses and enhancement of IL-10 expression. Beyond the eye, CO therapy has shown therapeutic potential in systemic cardiovascular, pulmonary, hepatic, and renal diseases, mainly due to its anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, and vasodilatory properties. These findings suggest that CO-based treatments could be extended to other neurodegenerative and inflammatory conditions, provided delivery methods and safety profiles are optimized for each application.

7.2. Research Gaps and Challenges

Despite encouraging preclinical and early clinical data, several challenges must be addressed before CO therapy can be widely adopted. Mechanistically, the precise molecular pathways through which CO exerts its protective effects in ocular tissues remain incompletely understood, particularly regarding its interactions with MAPK signaling and HO-1 regulation. Delivery methods also pose significant hurdles; inhaled CO lacks tissue specificity, poses dosing issues, and carries risks of systemic toxicity, while CORMs require further refinement in pharmacokinetics, stability, and safety. Oral liquid drug products appear promising, but have yet to be assessed in large, later stage clinicals trials. Clinical trials have demonstrated appropriate safety but limited efficacy, potentially due to subtherapeutic dosing or poor tissue targeting. Regulatory approval is contingent on demonstrating appropriate benefit:risk along with clinical feasibility.. Future research should prioritize mechanistic studies, delivery optimization, and translational trials to fully realize the therapeutic potential of CO in retinal and systemic diseases.

8. Conclusion

The discovery of endogenous CO synthesis via HO-1 has positioned both HO-1 activators and CO as promising therapeutic agents. Both have demonstrated beneficial effects in preclinical models of various diseases, including ocular pathologies such as retinopathy and age-related degeneration. However, the precise molecular mechanisms by which HO-1 and CO exert their protective effects remain incompletely understood. Future research should aim to delineate these pathways more clearly, particularly focusing on the modulation of oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis.

For HO-1, the development of more selective inducers is critical to minimize off-target effects and enhance therapeutic precision. Comparative studies evaluating the efficacy of HO-1 induction versus direct CO administration are also needed to guide clinical translation. Although human studies involving CO inhalation have shown safety, they have largely failed to yield significant therapeutic outcomes-possibly due to subtherapeutic dosing. Future trials should consider higher inhaled CO doses with rigorous monitoring of vital signs and COHb levels to ensure both safety and efficacy.

CORMs offer a delivery strategy that has the potential to circumvent systemic CO exposure and COHb elevation. These compounds can be designed to localize CO release to target tissues, making them attractive candidates for ocular therapy. Comprehensive studies on the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and toxicity profiles of CORMs are essential to determine their suitability for human use. Additionally, nanomaterial-based delivery systems may enhance CORM stability and tissue specificity, particularly in the context of retinal disease.

Importantly, HBI-002, an orally bioavailable CO drug product, represents a novel and practical alternative to both inhaled CO and CORMs. Its ease of administration as compared with inhaled CO, favorable safety profile as compared with CORMS, and supportive clinical data thus far make it a compelling candidate for further investigation in ocular disease models. Future research should explore its therapeutic potential, optimal dosing strategies, and long-term effects in retinal pathologies.

In summary, HO-1 activation and CO, whether delivered via inhalation, CORMs, or drug products like HBI-002, hold significant promise as therapeutic agents for retinal diseases. Continued research is essential to refine and translate these approaches into safe, effective treatments for patients suffering from vision-threatening conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.N.J. and P.M.M.; methodology, M.R.L. and M.K.; software, N.N.; validation, M.R.L., M.K. and N.N.; formal analysis, R.N.J. and P.M.M.; investigation, M.R.L., M.K. and R.N.J.; resources, M.C.T.; data curation, M.C.T. and R.N.J.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R.L., M. K. and R.N.J.; writing—review and editing, M.C.T., E.G., A.G.,. R.N.J. and P.M.M.; visualization, N.N. and A.G.; supervision, R.N.J. and P.M.M.; project administration, A.G.; funding acquisition, E.G., R.N.J. and P.M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by NIH grant EY033264.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Akt |

Protein kinase B |

| AIF-1 |

Allograft inflammatory factor 1 |

| AMPK |

AMP activated protein kinase |

| CAT |

Catalase |

| CO |

Carbon monoxide |

| COHb |

Carboxyhemoglobin |

| CoPP |

Cobalt protoporphyrin |

| CORM |

Carbon monoxide releasing molecule |

| CREB |

cAMP response element-binding protein |

| ERK1/2 |

extracellular-signal-regulated kinase-1/2 |

| GPx |

Glutathione peroxidase |

| GSH |

Glutathione |

| GTR |

Glutathione reductase |

| Hb |

Hemoglobin |

| HO-1 |

Heme oxygenase 1 |

| HSP70 |

Heat shock protein 70 |

| IL-1b |

Interleukin-1-beta |

| IL-6 |

Interleukin-6 |

| IL-10 |

Interleukin-10 |

| IL-17 |

Interleukin-17 |

| IOP |

Intraocular pressure |

| IRI |

Ischemia-reperfusion injury |

| iNOS |

inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| JNK1/2 |

c-Jun N-terminal kinase-1/2 |

| Keap1 |

Kelch-like ECH-associated protein-1 |

| LPS |

Lipopolysaccharide |

| NO |

Nitric oxide |

| O2 |

Oxygen |

| ONC |

Optic nerve crush |

| MAPK |

Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MCP-1 |

monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 |

| MDA |

Malondialdehyde |

| mTORC1 |

Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 |

| NF-kB |

nuclear factor kappa-light chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| Nrf2 |

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor-2 |

| PI3K |

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase |

| RGC |

Retinal ganglion cell |

| ROS |

Reactive oxygen species |

| RPE |

Retinal pigment epithelial cells |

| Sal A |

Salvianolic acid A |

| sGC |

Soluble guanylate cyclase |

| SCD |

Sickle cell disease |

| SOD |

superoxide dismutase |

| StRE |

Stress response element |

| Treg Cells |

Regulatory T cells |

| Th17 Cells |

T helper 17 cells |

| TNF-a |

Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| VEGF |

Vascular endothelial growth factor |

References

- Kovacs-Valasek, A.; et al. Three Major Causes of Metabolic Retinal Degenerations and Three Ways to Avoid Them. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24(10). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C.; et al. Visual impairment and blindness caused by retinal diseases: A nationwide register-based study. J Glob Health 2023, 13, 04126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallsh, J.O.; Gallemore, R.P. Anti-VEGF-Resistant Retinal Diseases: A Review of the Latest Treatment Options. Cells 2021, 10(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.T.; et al. Updates on medical and surgical managements of diabetic retinopathy and maculopathy. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila) 2025, 14(2), 100180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahr, T.A.; Bakri, S.J. Update on the Management of Diabetic Retinopathy: Anti-VEGF Agents for the Prevention of Complications and Progression of Nonproliferative and Proliferative Retinopathy. Life (Basel) 2023, 13(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.Y.; et al. Overcoming Treatment Challenges in Posterior Segment Diseases with Biodegradable Nano-Based Drug Delivery Systems. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrimawithana, T.R.; et al. Drug delivery to the posterior segment of the eye. Drug Discov Today 2011, 16(5-6), 270–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, F.J.; et al. Challenges and opportunities for drug delivery to the posterior of the eye. Drug Discov Today 2019, 24(8), 1679–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.L.; et al. Glutamine ameliorates intestinal ischemia-reperfusion Injury in rats by activating the Nrf2/Are signaling pathway. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2015, 8(7), 7896–904. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.D.; et al. Sulforaphane protects liver injury induced by intestinal ischemia reperfusion through Nrf2-ARE pathway. World J Gastroenterol 2010, 16(24), 3002–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Q.; et al. Ginsenoside Rb1 attenuates intestinal ischemia reperfusion induced renal injury by activating Nrf2/ARE pathway. Molecules 2012, 17(6), 7195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joe, Y.; et al. Cilostazol attenuates murine hepatic ischemia and reperfusion injury via heme oxygenase-dependent activation of mitochondrial biogenesis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2015, 309(1), G21–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, I.R.; et al. Pharmacological preconditioning with simvastatin protects liver from ischemia-reperfusion injury by heme oxygenase-1 induction. Transplantation 2008, 85(5), 732–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; et al. Pretreatment with intrathecal or intravenous morphine attenuates hepatic ischaemia-reperfusion injury in normal and cirrhotic rat liver. Br J Anaesth 2012, 109(4), 529–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, M.C.; et al. Cepharanthine mitigates lung injury in lower limb ischemia-reperfusion. J Surg Res 2015, 199(2), 647–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, T.; et al. Carnosol Is a Potent Lung Protective Agent: Experimental Study on Mice. Transplant Proc 2015, 47(6), 1657–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.Y.; et al. Valproic acid attenuates acute lung injury induced by ischemia-reperfusion in rats. Anesthesiology 2015, 122(6), 1327–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.H.; et al. Propofol attenuation of renal ischemia/reperfusion injury involves heme oxygenase-1. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2007, 28(8), 1175–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; et al. Protective Effect of Tempol on Acute Kidney Injury Through PI3K/Akt/Nrf2 Signaling Pathway. Kidney Blood Press Res 2016, 41(2), 129–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; et al. Exendin-4 ameliorates renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in the rat. J Surg Res 2013, 185(2), 825–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwa, J.S.; et al. 2-methoxycinnamaldehyde from Cinnamomum cassia reduces rat myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury in vivo due to HO-1 induction. J Ethnopharmacol 2012, 139(2), 605–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirunavukkarasu, M.; et al. Resveratrol alleviates cardiac dysfunction in streptozotocin-induced diabetes: Role of nitric oxide, thioredoxin, and heme oxygenase. Free Radic Biol Med 2007, 43(5), 720–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peake, B.F.; et al. Hydrogen sulfide preconditions the db/db diabetic mouse heart against ischemia-reperfusion injury by activating Nrf2 signaling in an Erk-dependent manner. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2013, 304(9), H1215–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; et al. Overexpression of Heme Oxygenase-1 in Mesenchymal Stem Cells Augments Their Protection on Retinal Cells In Vitro and Attenuates Retinal Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury In Vivo against Oxidative Stress. Stem Cells Int 2017, 2017, 4985323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; et al. Sulforaphane protects rodent retinas against ischemia-reperfusion injury through the activation of the Nrf2/HO-1 antioxidant pathway. PLoS One 2014, 9(12), e114186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.H.; et al. Retinal protection from acute glaucoma-induced ischemia-reperfusion injury through pharmacologic induction of heme oxygenase-1. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2010, 51(9), 4798–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, M.P.; Bach, F.H. Heme oxygenase-1: from biology to therapeutic potential. Trends Mol Med 2009, 15(2), 50–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; et al. Activation of Nrf2/HO-1 signaling: An important molecular mechanism of herbal medicine in the treatment of atherosclerosis via the protection of vascular endothelial cells from oxidative stress. J Adv Res 2021, 34, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; et al. The NRF-2/HO-1 Signaling Pathway: A Promising Therapeutic Target for Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. J Inflamm Res 2024, 17, 8061–8083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; et al. Carbon Monoxide Controllable Targeted Gas Therapy for Synergistic Anti-inflammation. iScience 2020, 23(9), 101483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damasceno, R.O.S.; et al. Modulatory Role of Carbon Monoxide on the Inflammatory Response and Oxidative Stress Linked to Gastrointestinal Disorders. Antioxid Redox Signal 2022, 37(1-3), 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilska-Wilkosz, A.; Górny, M.; Iciek, M. Biological and Pharmacological Properties of Carbon Monoxide: A General Overview. Oxygen 2022, 2(2), 130–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.J.; et al. Carbon Monoxide Inhibits Tenascin-C Mediated Inflammation via IL-10 Expression in a Septic Mouse Model. Mediators Inflamm 2015, 2015, 613249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, N.L.; et al. Carbon Monoxide Modulation of Microglia-Neuron Communication: Anti-Neuroinflammatory and Neurotrophic Role. Mol Neurobiol 2022, 59(2), 872–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullotta, F.; di Masi, A.; Ascenzi, P. Carbon monoxide: an unusual drug. IUBMB Life 2012, 64(5), 378–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piantadosi, C.A. Carbon monoxide, reactive oxygen signaling, and oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med 2008, 45(5), 562–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consoli, V.; et al. Heme Oxygenase-1 Signaling and Redox Homeostasis in Physiopathological Conditions. Biomolecules 2021, 11(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Yang, X.; Wang, B. Carbon monoxide signaling and soluble guanylyl cyclase: Facts, myths, and intriguing possibilities. Biochem Pharmacol 2022, 200, 115041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; et al. Carbon monoxide modulates Fas/Fas ligand, caspases, and Bcl-2 family proteins via the p38alpha mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway during ischemia-reperfusion lung injury. J Biol Chem 2003, 278(24), 22061–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.S.; et al. Carbon monoxide modulates apoptosis by reinforcing oxidative metabolism in astrocytes: role of Bcl-2. J Biol Chem 2012, 287(14), 10761–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; et al. Carbon monoxide releasing molecule-2 attenuated ischemia/reperfusion-induced apoptosis in cardiomyocytes via a mitochondrial pathway. Mol Med Rep 2014, 9(2), 754–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogeris, T.; et al. Cell biology of ischemia/reperfusion injury. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 2012, 298, 229–317. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, N.N.; et al. Retinal ischemia: mechanisms of damage and potential therapeutic strategies. Prog Retin Eye Res 2004, 23(1), 91–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla Elsayed, M.E.A.; et al. Sickle cell retinopathy. A focused review. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2019, 257(7), 1353–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.; et al. Sickle cell retinopathy: A literature review. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992) 2017, 63(12), 1100–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarbin, M.A. Current concepts in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol 2004, 122(4), 598–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korthuis, R.J.; Granger, D.N. Reactive oxygen metabolites, neutrophils, and the pathogenesis of ischemic-tissue/reperfusion. Clin Cardiol 1993, 16((4) Suppl 1, I19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusari, J.; et al. Effect of brimonidine on retinal and choroidal neovascularization in a mouse model of retinopathy of prematurity and laser-treated rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011, 52(8), 5424–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; et al. Retinal ischemia and reperfusion causes capillary degeneration: similarities to diabetes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2007, 48(1), 361–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; et al. Low-dose carbon monoxide inhalation protects neuronal cells from apoptosis after optic nerve crush. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2016, 469(4), 809–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; et al. Preconditioning with carbon monoxide inhalation promotes retinal ganglion cell survival against optic nerve crush via inhibition of the apoptotic pathway. Mol Med Rep 2018, 17(1), 1297–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stagni, E.; et al. A water-soluble carbon monoxide-releasing molecule (CORM-3) lowers intraocular pressure in rabbits. Br J Ophthalmol 2009, 93(2), 254–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagone, P.; et al. Carbon monoxide-releasing molecule-A1 (CORM-A1) improves clinical signs of experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis (EAU) in rats. Clin Immunol 2015, 157(2), 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagni, E.; et al. Morphine-induced ocular hypotension is modulated by nitric oxide and carbon monoxide: role of mu3 receptors. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 2010, 26(1), 31–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbrich, F.; et al. The Carbon monoxide releasing molecule ALF-186 mediates anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects via the soluble guanylate cyclase ss1 in rats' retinal ganglion cells after ischemia and reperfusion injury. J Neuroinflammation 2017, 14(1), p. 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbrich, F.; et al. Carbon monoxide treatment reduces microglial activation in the ischemic rat retina. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2016, 254(10), 1967–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stifter, J.; et al. Neuroprotection and neuroregeneration of retinal ganglion cells after intravitreal carbon monoxide release. PLoS One 2017, 12(11), e0188444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, J.; et al. Preconditioning with inhalative carbon monoxide protects rat retinal ganglion cells from ischemia/reperfusion injury. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2010, 51(7), 3784–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schallner, N.; et al. Postconditioning with inhaled carbon monoxide counteracts apoptosis and neuroinflammation in the ischemic rat retina. PLoS One 2012, 7(9), e46479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbrich, F.; et al. The CORM ALF-186 Mediates Anti-Apoptotic Signaling via an Activation of the p38 MAPK after Ischemia and Reperfusion Injury in Retinal Ganglion Cells. PLoS One 2016, 11(10), e0165182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schallner, N.; et al. Carbon monoxide abrogates ischemic insult to neuronal cells via the soluble guanylate cyclase-cGMP pathway. PLoS One 2013, 8(4), e60672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.C.; et al. Carbon monoxide induces heme oxygenase-1 to modulate STAT3 activation in endothelial cells via S-glutathionylation. PLoS One 2014, 9(7), e100677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piantadosi, C.A.; et al. Heme oxygenase-1 regulates cardiac mitochondrial biogenesis via Nrf2-mediated transcriptional control of nuclear respiratory factor-1. Circ Res 2008, 103(11), 1232–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; et al. Carbon monoxide-activated Nrf2 pathway leads to protection against permanent focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke 2011, 42(9), 2605–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.H.; et al. Carbon monoxide produced by heme oxygenase-1 in response to nitrosative stress induces expression of glutamate-cysteine ligase in PC12 cells via activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Nrf2 signaling. J Biol Chem 2007, 282(39), 28577–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuckerbraun, B.S.; et al. Carbon monoxide protects against liver failure through nitric oxide-induced heme oxygenase 1. J Exp Med 2003, 198(11), 1707–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.M.; et al. Carbon monoxidereleasing molecules protect against blue light exposure and inflammation in retinal pigment epithelial cells. Int J Mol Med 2020, 46(3), 1096–1106. [Google Scholar]

- Aitkenhead, M.J.; Lumsdon, P.; Miller, D.R. Remote sensing-based neural network mapping of tsunami damage in Aceh, Indonesia. Disasters 2007, 31(3), 217–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas, I.O.; et al. A Phase II Clinical Trial of Low-Dose Inhaled Carbon Monoxide in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Chest 2018, 153(1), 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredenburgh, L.E.; et al. A phase I trial of low-dose inhaled carbon monoxide in sepsis-induced ARDS. JCI Insight 2018, 3(23). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, J.J.; et al. Carbon Monoxide Poisoning: Pathogenesis, Management, and Future Directions of Therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017, 195(5), 596–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichhorn, L. M. Thudium, and B. Juttner, The Diagnosis and Treatment of Carbon Monoxide Poisoning. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2018, 115(51-52), 863–870. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, L.K.; Clinical practice. Carbon monoxide poisoning. N Engl J Med 2009, 360(12), 1217–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, D.R. Inhaled Carbon Monoxide: From Toxin to Therapy. Respir Care 2017, 62(10), 1333–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foresti, R.; Bani-Hani, M.G.; Motterlini, R. Use of carbon monoxide as a therapeutic agent: promises and challenges. Intensive Care Med 2008, 34(4), 649–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomperts, E.; Gompertsd, A.; Levy, H. Clinical Trials of Low-Dose Carbon Monoxide, in Carbon Monoxide in Drug Discovery; 2022; pp. 511–527. [Google Scholar]

- Resch, H.; et al. Inhaled carbon monoxide increases retinal and choroidal blood flow in healthy humans. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2005, 46(11), 4275–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bathoorn, E.; et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of inhaled carbon monoxide in patients with COPD: a pilot study. Eur Respir J 2007, 30(6), 1131–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Dorrington, K.L.; Robbins, P.A. Respiratory control in humans after 8 h of lowered arterial PO2, hemodilution, or carboxyhemoglobinemia. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2001, 90(4), 1189–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, F.B.; et al. Effects of carbon monoxide inhalation during experimental endotoxemia in humans. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005, 171(4), 354–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knauert, M.; et al. Therapeutic applications of carbon monoxide. In Oxid Med Cell Longev; 2013; Volume 2013, p. 360815. [Google Scholar]

- Motterlini, R.; Otterbein, L.E. The therapeutic potential of carbon monoxide. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2010, 9(9), 728–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romao, C.C.; et al. Developing drug molecules for therapy with carbon monoxide. Chem Soc Rev 2012, 41(9), 3571–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winburn, I.C.; et al. Cell damage following carbon monoxide releasing molecule exposure: implications for therapeutic applications. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2012, 111(1), 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natanson, C.; et al. Cell-free hemoglobin-based blood substitutes and risk of myocardial infarction and death: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2008, 299(19), 2304–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alayash, A.I. Hemoglobin-Based Blood Substitutes and the Treatment of Sickle Cell Disease: More Harm than Help? Biomolecules 2017, 7(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crook, S.H.; et al. Mn(CO)4S2CNMe(CH2CO2H)], a new water-soluble CO-releasing molecule. Dalton Trans. 2011, 40(16), 4230–5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; et al. CO in a pill": Towards oral delivery of carbon monoxide for therapeutic applications. J Control Release 2021, 338, 593–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; et al. Towards "CO in a pill": Pharmacokinetic studies of carbon monoxide prodrugs in mice. J Control Release 2020, 327, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; et al. Activated charcoal dispersion of carbon monoxide prodrugs for oral delivery of CO in a pill. Int J Pharm 2022, 618, 121650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; et al. Emerging Delivery Strategies of Carbon Monoxide for Therapeutic Applications: from CO Gas to CO Releasing Nanomaterials. Small 2019, 15(49), p. e1904382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belcher, J.D.; et al. Oral carbon monoxide therapy in murine sickle cell disease: Beneficial effects on vaso-occlusion, inflammation and anemia. PLoS One 2018, 13(10), e0205194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, K.N.; et al. Neuroprotection of low dose carbon monoxide in Parkinson's disease models commensurate with the reduced risk of Parkinson's among smokers. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2024, 10(1), p. 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves de Souza, R.W.; et al. Beneficial Effects of Oral Carbon Monoxide on Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity. J Am Heart Assoc 2024, 13(9), p. e032067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, S.; et al. Carbon Monoxide as a Potential Therapeutic Agent: A Molecular Analysis of Its Safety Profiles. J Med Chem 2024, 67(12), 9789–9815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benignus, V.A.; Annau, Z. Carboxyhemoglobin formation due to carbon monoxide exposure in rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1994, 128(1), 151–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/d/2015-29989.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).