1. Introduction

Serious games, games designed for purposes beyond entertainment, have a long heritage, with Clark Abt (1987) credited as an early pioneer (Abt, 1987). These games have been applied in diverse domains such as education, business, marketing, and healthcare, leveraging narrative and interactive multimedia to engage learners (Michael & Chen, 2005; Rieber, 2005). They are often integrated into game-based learning strategies: serious games serve as tools to make instruction more immersive and motivating, and game-based learning approaches commonly reframe learning tasks as game-like challenges to heighten interest and effectiveness (Becker, 2021). With the rise of digital and distance education, such game-based approaches are valued for sustaining learner engagement: they let students learn by doing and experiment with complex, low-stakes problem-solving tasks while receiving immediate feedback on performance (Gee, 2003). For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, instructors used serious games to complement online courses and sustain student motivation and engagement (Arias-Calderón et al., 2022; Nieto-Escamez & Roldán-Tapia, 2021). Some empirical works show that well-designed educational games promote active participation, creativity, collaboration, and complex problem solving, thereby fostering higher-order cognitive skills (Nieto-Escamez & Roldán-Tapia, 2021; Rondon et al., 2013).

Building on the tradition, educators have explored a variety of serious game formats and game-based learning contents to enhance pedagogy, among which virtual escape rooms have emerged as a particularly compelling approach (Hill Jr et al., 2020; Hodhod et al., 2023; Jaffray et al., 2021; Löffler et al., 2021; Nkongolo, 2024). These immersive learning environments combine interactive problem-solving, narrative-driven scenarios, and time-bound challenges to simulate real-world experiences in a gamified setting. In cybersecurity education, escape rooms are particularly valuable, offering simulations that bridge the gap between theoretical instruction and real-world application. This format promotes sustained engagement and deepens conceptual understanding by requiring learners to apply knowledge in authentic contexts (Pramod, 2024). Additionally, virtual escape rooms may offer an inherent advantage in addressing academic integrity concerns in the era of generative AI. The interactive nature of these environments requires students to demonstrate skills through authentic performance rather than textual artifacts alone. As researchers note in their analyses of generative AI's impact on assessment, task-based evaluations requiring real-time interaction with dynamic systems present significant challenges for current AI systems (Nikolic et al., 2024). Cybersecurity escape rooms like those developed by Spatafora et al. and Löffler et al. exemplify this approach by requiring learners to navigate sequential challenges, manipulate virtual objects, and apply domain knowledge contextually, assessment formats that leverage the distinctive capabilities of human problem-solving in authentic scenarios rather than relying on static, text-based responses that may be more vulnerable to AI-generated content (Löffler et al., 2021; Spatafora et al., 2024) .

In addition to enhancing learning outcomes, game-based learning materials, such as educational escape rooms, inherently exemplify active learning strategies that engage students through interactive problem-solving, collaboration, and real-time decision-making (Abdelghani et al., 2023; Reddy & Johnson, 2024). These immersive experiences foster deeper cognitive engagement, making it challenging for students to engage in academic dishonesty, which might be facilitated by AI tools by supplying solutions (Reddy & Johnson, 2024). By embedding learning within interactive and collaborative contexts, educational escape room can reduce opportunities for misconduct and promote a deeper understanding of the material. Moreover, when designing assessments using a game-based interactive environment, it can offer a resilient alternative to traditional formats like essays and reports, which are increasingly susceptible to AI-assisted generation (Bond et al., 2019; Nikolic et al., 2024; Rodríguez-Rivera et al., 2025; Zawacki-Richter et al., 2019).

However, despite their pedagogical potential, significant gaps remain in the use of virtual escape rooms for cybersecurity governance and policy education. Existing approaches in this area often rely on abstract, lecture-based, or text-heavy instructional methods, which can result in low engagement and limited practical application of theoretical concepts (Hodhod et al., 2023) (Pramod, 2024; Rawlinson & Whitton, 2024; Scherb et al., 2023; Spatafora et al., 2024; Stephen Hart a, 2020). Moreover, few studies have empirically examined the effectiveness of escape rooms in improving student engagement and in fostering the application of cybersecurity governance and policy principles (Pramod, 2024; Rawlinson & Whitton, 2024; Scherb et al., 2023; Spatafora et al., 2024; Stephen Hart a, 2020). Addressing this gap is essential to developing more impactful educational strategies, particularly in preparing students to apply governance, compliance, and risk management frameworks in professional settings.

This paper addresses this gap by introducing a virtual escape room specifically designed to teach cybersecurity governance and policy through immersive and engaging gameplay. The virtual escape room consists of sequentially unlocked challenges, requiring students to solve real-world governance problems, align policies with cybersecurity standards, and manage risk under realistic constraints. Employing a design-based research approach, this study evaluates the effectiveness of the escape room in improving student engagement, conceptual understanding, and practical skills in cybersecurity governance and policymaking. The primary contribution of this paper is twofold: (1) it presents a rigorously developed educational tool tailored to the unique demands of cybersecurity governance education, and (2) it provides empirical evidence demonstrating the tool’s effectiveness in overcoming limitations of traditional pedagogical methods, including challenges in student engagement and assessment integrity in a generative AI-influenced learning environment.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 presents a short review of the literature on game-based learning and serious games in cybersecurity education.

Section 3 outlines our research methodology and game development process.

Section 4 presents the implementation details of the escape room, including its architecture and learning integration.

Section 5 discusses evaluation findings, examining student engagement and learning outcomes. Finally,

Section 6 concludes with key insights and potential directions for future research.

2. Background Study

2.1. The Evolving Challenges in Cybersecurity Education

The rapid digital transformation of business and society has elevated cybersecurity from a narrow technical concern to a critical organizational priority. As more critical infrastructure and sensitive data move online, cyber breaches now pose potentially existential threats to organizations of all sizes (Forum, 2025). This heightened threat landscape has driven an unprecedented demand for skilled cybersecurity professionals, yet the supply of qualified experts consistently falls short. Recent industry projections forecast a workforce gap of approximately 4.8 million cybersecurity positions worldwide in 2025 (ISC², 2023). This shortage is especially acute in areas like cybersecurity governance, policy development, and strategic risk management, domains that underpin an organization’s security resilience but traditionally receive less attention in technical training.

Traditional cybersecurity education approaches have struggled to address emerging workforce needs. Conventional pedagogies dominated by lecture-based instruction and text-driven assessments often fail to develop the multifaceted competencies essential for real-world cybersecurity governance. These critical competencies include risk assessment prioritization, policy framework alignment, regulatory compliance evaluation, and collaborative security decision-making. Students frequently struggle to translate abstract governance concepts into practical skills, especially when theory must be applied within complex organizational environments (Pramod, 2024). This theory-practice gap highlights the limitations of passive learning methods in cybersecurity education.

The challenge has been further compounded by the rise of generative AI technologies, which are disrupting traditional assessment models in higher education (Hoernig et al., 2024; Nikolic et al., 2024). Standard learning materials, including assignments long used to teach and evaluate students’ understanding of security concepts, can now be partially or wholly generated by AI tools. As a result, students may heavily rely on AI output instead of working on their own and submit AI-produced work that appears competent on the surface yet reflects only superficial comprehension, undermining the authenticity of learning outcomes. These trends have prompted educators to seek more innovative, experience-based pedagogical strategies that actively engage learners and are resilient to academic dishonesty.

Our escape room design responds to these educational challenges by embedding core cybersecurity governance competencies into an interactive, experience-based format. Each of the three zones in the game targets specific learning outcomes: Zone 1 (Risk Maze) strengthens risk identification and prioritization through spatial decision-making tasks; Zone 2 (Framework Matching) supports the development of policy framework evaluation by challenging students to classify and align governance standards; and Zone 3 (Policy Drafting) guides learners through the structured creation of cybersecurity policies in response to dynamic, scenario-based prompts. These mechanics immerse students in realistic decision-making environments, requiring the practical application of abstract concepts. By encouraging active problem-solving and contextual thinking, the escape room helps mitigate the theory-practice divide often observed in traditional instruction, while simultaneously reducing opportunities for generative AI misuse in assessments (Hill Jr et al., 2020).

2.2. Game-Based Learning as an innovative solution

One response to these challenges is the integration of game-based learning as a recognised variety of serious games into cybersecurity education. Serious games, defined as games designed for a purpose beyond entertainment, create interactive and immersive environments that actively involve learners in problem-solving and decision-making tasks. In recent years, the field has evolved to include more specific approaches such as game-based learning (GBL), educational games, and simulation-based learning, though all share the fundamental goal of embedding educational content within engaging game experiences. Serious games are designed for a purpose beyond entertainment, create interactive and immersive environments that actively involve learners in problem-solving and decision-making tasks (Boyle et al., 2016). By embedding educational content within engaging game narratives, serious games can provide meaningful context for learning, increase student motivation, and improve knowledge retention compared to traditional passive instruction (Girard et al., 2013). A growing body of research, including recent meta-analyses, has documented the educational benefits of serious games across disciplines: they can enhance student engagement and motivation, improve conceptual understanding, and develop critical thinking and problem-solving skills (Pacheco-Velázquez et al., 2023; Spatafora et al., 2024; Zhonggen, 2019). Importantly, game-based learning offers a safe, low-risk setting for students to practice complex skills and apply theoretical knowledge to realistic scenarios. The interactivity and immediate feedback inherent to games allow learners to learn from mistakes and refine their understanding in a supportive, hands-on manner (Girard et al., 2013). Given the dynamic and practical nature of the cybersecurity field, these attributes make serious games a particularly attractive approach for bridging the gap between theory and practice in cybersecurity education.

In cybersecurity education, the application of serious games is still emerging but shows considerable potential. Because cybersecurity concepts (especially in governance and policy) can be abstract and challenging to grasp through traditional teaching methods alone, simulated environments can bring these concepts to life. Early studies have explored using serious games to teach fundamental cybersecurity topics such as network defense, incident response, and ethical hacking, demonstrating that students can learn technical content effectively through gameplay (Calvano et al., 2023; Hill Jr et al., 2020). Others have created simulation games that capture the adversarial nature of cybersecurity, placing learners in attacker/defender scenarios, to let students experience the dynamic interplay of threats and defenses in a controlled setting (Calvano et al., 2023; Manuel Arias-Calderón 1, 2022; Scherb et al., 2023). Through these initiatives’ improvements in student engagement, knowledge retention, and self-efficacy, suggesting that game-based learning can make cybersecurity concepts more tangible and memorable for learners.

2.3. Educational Escape Rooms: Bridging Theory and Practice

Within this broader movement, educational escape rooms have gained traction as an especially engaging genre of serious games for teaching cybersecurity. Educational escape rooms adapt the popular entertainment concept of escape-room games, where individuals or teams solve puzzles to “escape” a themed scenario, into a learning experience with defined educational objectives. The idea draws inspiration from high-intensity training exercises (for example, military team simulations that build problem-solving and decision-making under pressure) combined with commercial escape-room games' storytelling and puzzle elements. In an educational escape room, participants work collaboratively against the clock to solve a series of interconnected puzzles and challenges, uncover clues, and achieve a specific goal (such as resolving a simulated cybersecurity incident) in order to “escape” or complete the scenario (Jaffray et al., 2021; Spatafora et al., 2024). Crucially, these puzzles are designed to reinforce learning outcomes: the game’s narrative and challenges are aligned with the subject matter being taught. This format naturally encourages teamwork, communication, and active problem-solving, as students must apply their knowledge and think critically to progress through the game.

Recent studies and reviews indicate that escape rooms can offer many of the same benefits as other serious games, often to an even greater degree (Fotaris & Mastoras, 2019; Gordillo & López-Fernández, 2024). Systematic reviews of educational escape rooms have identified heightened motivation and engagement as hallmark outcomes of this approach, alongside improvements in teamwork and communication skills fostered by the collaborative nature of the game (Fotaris & Mastoras, 2019; Veldkamp et al., 2020). Veldkamp et al. (Veldkamp et al., 2020) systematically reviewed 68 empirical studies on educational escape rooms and reported generally positive effects on student motivation and interest. However, they also stressed that the effectiveness of these rooms depends on specific design features. Elements such as a coherent narrative, alignment between learning objectives and puzzle design, appropriate challenge levels with feedback, and the promotion of collaboration were identified as crucial to ensuring engagement. Thus, while educational escape rooms can be motivational, their impact is contingent on thoughtful and context-sensitive design.

Löffler et al. developed CySecEscape 2.0 (Löffler et al., 2021), a virtual escape room aimed at raising cybersecurity awareness among employees in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Their evaluation used a combination of think-aloud protocols, direct observation, and post-game surveys to assess engagement. Players were observed discussing decoys, persisting through non-obvious puzzles, and even exploring hidden solution paths such as inspecting the game’s source code, behaviors that reflected deep cognitive involvement. Similarly, Jaffray et al. introduced SherLOCKED, (Jaffray et al., 2021) a detective-themed serious game for undergraduate cybersecurity education. Engagement in this case was primarily measured through post-game surveys capturing changes in self-reported confidence, alongside qualitative feedback. However, they claimed that students’ participation in the game survey was higher than in the previous (generally) course-wise survey. In their feedback, students highlighted the game’s narrative, immediate feedback, and retro-style interface as key elements sustaining their attention and motivation. Many expressed willingness to reuse the game for revision, indicating lasting interest beyond initial exposure.

Furthermore, an emerging advantage of educational escape rooms in the current academic landscape is that they could offer resistance to generative AI-based cheating. Traditional written assessments have become increasingly vulnerable to AI-generated answers, as noted by Hoernig et al. (Hoernig et al., 2024) and Nikolić et al. (Nikolic et al., 2024). In contrast, the hands-on, interactive challenges in an escape room are not easily replicated by a language model. Solving an escape room typically requires real-time human problem-solving, the manipulation of clues or objects (in a virtual environment), and context-specific reasoning that goes beyond retrieving information. These activities remain difficult for AI to perform convincingly, meaning that a student must engage directly with the material to succeed. Thus, escape-room-based assessments can uphold academic integrity by ensuring the work is genuinely the student’s own, even as generative AI tools proliferate.

Despite the promise of serious games and escape rooms, it is important to acknowledge that the research in this area is still nascent, and several challenges remain. In this study, we directly tackle these limitations by (1) conducting a longitudinal pre-/post-test analysis to measure real-world skill transfer from the game to authentic cybersecurity tasks, (2) applying a mixed-methods approach, including think-aloud protocols and focus-group interviews, to identify design best practices, and (3) validating our 3-zone escape-room framework at scale through a controlled classroom trial.

Moreover, current serious games do not always tackle the specific issues of student disengagement in lecture-based courses, or may not fully capture the complexity of practical cybersecurity work (Hill Jr et al., 2020; Pacheco-Velázquez et al., 2023). In particular, few or no educational games focus on the governance and policy aspects of cybersecurity, which are critical for developing well-rounded professionals. There is a clear need for continued research and development to refine educational escape rooms and other serious games so that they effectively complement traditional instruction and address these gaps.

A critical shortcoming in current serious game-based cybersecurity education is the underutilization of established learning theories as a foundation for design and evaluation. Many existing cybersecurity games and educational escape rooms are developed ad hoc, with little explicit alignment to pedagogical frameworks. This lack of theoretical grounding means that while such games can be engaging, they may not fully leverage how students learn best, and/or these are not claimed. Constructivist learning theory, for example, posits that learners actively construct knowledge through experience (as emphasized by Piaget (Piaget, 1976) and Vygotsky (Vygotsky, 1978)) rather than passively receive information.

In practice, this implies that an educational game should prompt learners to experience challenges, reflect on outcomes, and abstract lessons to apply in new situations. Frameworks like Kolb’s experiential learning cycle provide a concrete model for this process, detailing how learners progress through concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation (Forum, 2025). An escape room aligned with Kolb’s cycle would not only immerse students in realistic cybersecurity scenarios but also ensure structured debriefings and opportunities for experimentation, thus transforming gameplay into lasting knowledge.

Similarly, Csikszentmihályi’s (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990) flow theory offers design guidance by suggesting that optimal learning occurs when challenges are balanced with player skill, goals are clear, and feedback is immediate. A serious game grounded in flow principles can keep students in a state of focused immersion, which enhances engagement and motivation. However, most cybersecurity education games do not always explicitly incorporate these principles, resulting in missed opportunities to maximize learning efficacy. This theoretical gap in current designs potentially limits their educational impact, as activities may not consistently facilitate deep reflection or maintain the optimal challenge–skill balance needed for sustained engagement.

In addition to the overarching need for stronger theoretical underpinnings, several other critical gaps are evident in existing cybersecurity serious games:

Limited Focus on Governance and Policy: Most cybersecurity games emphasize hands-on technical skills (e.g., cryptography, network defense) while neglecting broader governance, compliance, and policy topics. As a result, learners get little exposure to management-level cybersecurity decision-making and frameworks. This gap is problematic because organizational security relies not only on technical expertise but also on understanding policies, standards, and human factors.

Minimal Empirical Validation: There is a lack of rigorous evaluation of learning outcomes in many game-based cybersecurity interventions. Few studies go beyond anecdotal evidence or simple pre/post surveys to empirically validate that players of these serious games retain knowledge or perform better in real-world scenarios. Without robust assessments (e.g., controlled studies or long-term follow-ups), it remains unclear how effective these games truly are in building cybersecurity competencies.

Lack of Industry Alignment: Current cybersecurity games often show minimal alignment with industry practices and needs. Few are developed with direct input from industry professionals or mapped to widely used frameworks and certifications. Consequently, the scenarios and skills practiced in-game may not translate neatly to the challenges faced in the workplace. This gap in industry relevance means students might enjoy the game but still struggle to apply their knowledge on the job. Strengthening ties between game design and cyber industry standards (for example,

integrating content from frameworks like NIST or ISO 27001) is largely an unmet need.

Table 1 presents a comparative summary of some existing serious games in cybersecurity education. It also highlights the focus, and some specific gaps identified in the literature, providing a clear context for our contribution. Overall, addressing the gap of theoretical grounding remains essential; by explicitly integrating constructivist principles and models, serious games in cybersecurity education can be designed to support deeper, more effective learning. In parallel, tackling additional limitations related to content coverage (particularly in governance and policy), empirical evaluation, accessibility, and alignment with industry standards will significantly enhance the impact and relevance of these tools. Our work responds directly to these identified needs by developing a theory-informed, governance-focused educational escape room designed for accessibility, engagement, and academic integrity.

3. Research Methodology and System Development

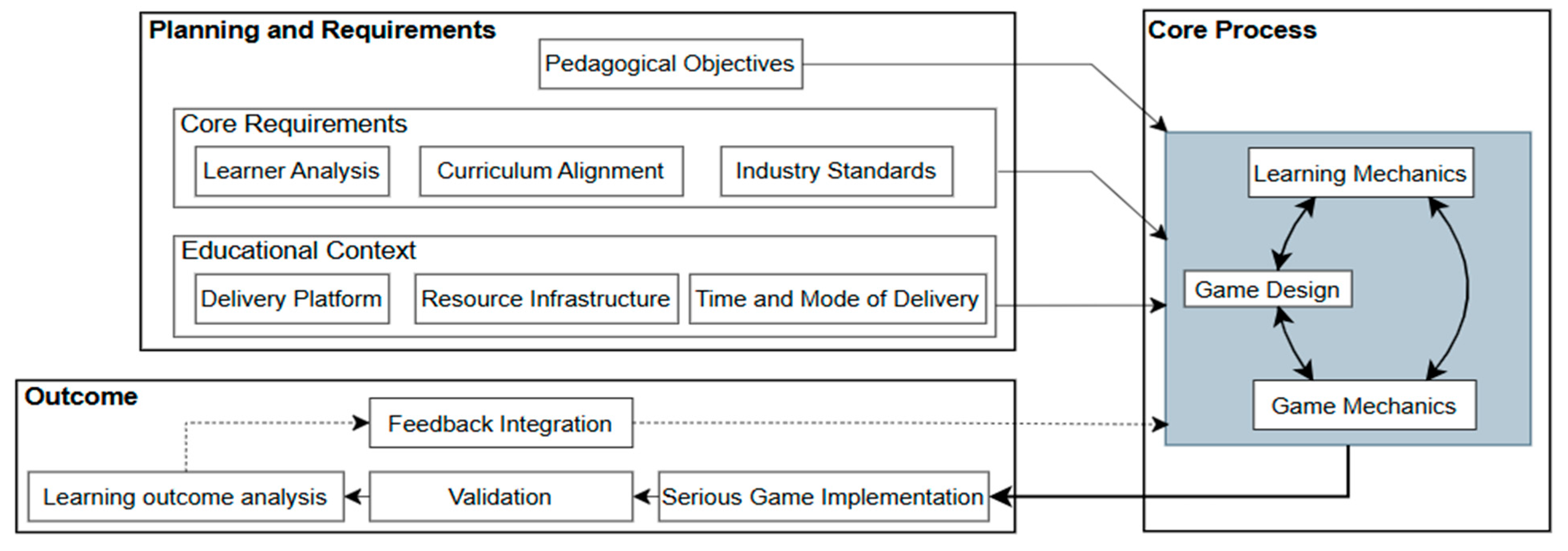

The system development of the cybersecurity governance escape room was guided by a structured methodology comprising three interconnected phases:

Planning & Requirements, Process, and

Output, as shown in

Figure 1. This methodology extends beyond conventional serious game development frameworks (Kulshrestha et al., 2021) by addressing the distinctive challenges associated with cybersecurity education, particularly in governance and policy development (Scherb et al., 2023). Each phase is described in the following section.

3.1. Planning & Requirements Phase

In the Planning and Requirements phase, we established clear Pedagogical Objectives grounded in constructivist learning theory. Following constructivist principles, the escape room’s learning goals have been crafted to promote active learner engagement and hands-on experiential learning, rather than passive knowledge transfer. Specifically, players would actively solve problems and apply cybersecurity governance concepts in context, enabling them to “learn by doing” in realistic scenarios. The pedagogical objectives were designed to leverage key constructivist principles. For instance, we implemented Vygotsky's Zone of Proximal Development by creating challenges that begin with basic governance concepts that students can solve independently, then gradually progress to more complex problems that stretch their capabilities. This scaffolding is evident in the progression from simple risk identification in Zone 1 to the more complex policy drafting tasks in Zone 3. The escape room also incorporates social constructivist elements through classroom implementation, where students typically work in small groups of 2-3 at shared computer stations. While the game itself runs on individual machines, the classroom setting encourages peer discussion, collaborative problem-solving, and knowledge sharing. During implementation, we observed students actively discussing potential solutions, explaining concepts to each other, and collectively working through challenges. This approach creates cognitive conflict another key constructivist principle as students must reconcile different interpretations and approaches when solving puzzles, leading to deeper understanding through social negotiation of meaning.

This cumulative structure supports learners in building conceptual understanding through active participation and contextual problem-solving, which is one of the core principles of constructivist and experiential learning (Efgivia et al., 2021; Hein, 1991; Reigeluth, 2013; Wu et al., 2012). These pedagogically driven requirements, active engagement, experiential learning, collaboration, meaningful context, and scaffolded learning guided the development of learning outcomes, ensuring that the escape room’s educational goals were aligned with how learners construct, apply, and deepen knowledge through authentic experiences.

Beyond the pedagogical foundations, this phase also involved a thorough analysis of the learner profile and requirements and alignment with academic and industry standards. We conducted a Learner Analysis to understand the target audience (e.g., university cybersecurity and business students), their prior knowledge of governance concepts, and any misconceptions to address. This informed the difficulty level and scaffolding of puzzles. Curriculum Alignment was performed to map the game’s learning outcomes to course or program learning objectives as mentioned in appendix A, for example, if a learning outcome was to “formulate an incident response policy,” a corresponding problem/puzzle was planned to have players actually draft or critique a policy. In addition, relevant Industry Standards and frameworks (such as ISO 27001 governance standards or NIST cybersecurity framework principles) were reviewed and integrated into the content to increase authenticity. By incorporating industry terminology and scenarios (for instance, a puzzle might involve implementing a control from a well-known security framework), the game ensured that students learned concepts aligned with professional practice. This attention to industry alignment at the requirements stage is a notable strength of our approach, directly addressing the common lack of real-world governance focus in cybersecurity games.

Finally, the Delivery Platform, Resource Infrastructure, and Time/Mode of Delivery were decided: a flexible web-based virtual escape room platform (built with Unity3D) that could be accessed remotely was chosen as it required standard hardware, thus minimizing technical barriers for broad accessibility. Key practical constraints (e.g., session duration, group size, and available technology) were factored into the design requirements. In summary, the Planning & Requirements phase produced a blueprint for the escape room that melded sound pedagogical theory with curriculum needs and industry context, setting the stage for an educational experience targeting governance competencies in an engaging way.

3.2. Core Phase: Iterative Design Approach

The Core Phase involved an iterative, cyclical approach to designing and developing the UNSW Cyber Escape Room, emphasizing continuous refinement based on structured feedback. A critical part of this phase was adopting the Learning Mechanics–Game Mechanics (LM–GM) framework (Arnab et al., 2015), and Lim et al. (Lim et al., 2015)), selected due to its proven effectiveness in systematically aligning educational goals with engaging game elements. Specifically, LM–GM helped ensure that each puzzle’s design directly supported intended learning mechanics through suitable and engaging game mechanics. For example, analyzing cybersecurity policies and conducting risk assessments were matched with timed challenges and risk-versus-reward decision puzzles, respectively. This prevented divergence between the game's educational and entertainment elements, embedding every learning activity within an interactive, enjoyable format.

Initially, three primary iterations were conducted, each addressing specific design components and feedback from diverse stakeholders, including cybersecurity educators, industry practitioners, and student test groups. The first iteration focused on creating preliminary prototypes of each of the three interactive zones: Risk Maze, Framework Matching, and Policy Drafting. These initial prototypes underwent evaluation through internal testing and expert reviews, emphasizing the effectiveness of mapping game mechanics to learning mechanics.

Substantial feedback from the first iteration highlighted several critical points for improvement, including the clarity of puzzle instructions, user interface intuitiveness, and difficulty balancing. Specifically, stakeholders noted that puzzles in Zone 2 (Framework Matching) required clearer instructions and that Zone 3 (Policy Drafting) puzzles initially proved overly complex, resulting in user frustration.

In response, a second iteration introduced significant refinements: instructions were simplified with explicit, context-sensitive hints; puzzle complexity was recalibrated to better match students' skill levels as per Csikszentmihalyi’s Flow Theory (1990), ensuring an optimal challenge-skill balance (Sweetser & Wyeth, 2005). Furthermore, narrative enhancements were integrated across all zones, reinforcing thematic coherence and better contextualizing puzzles within real-world cybersecurity scenarios.

The third and final iteration involved extensive playtesting with representative student groups in classroom settings, focusing on usability and engagement metrics. Feedback from these sessions led to further fine-tuning, including adjustments to time constraints and the implementation of adaptive feedback systems providing immediate corrective guidance, essential for maintaining player engagement and educational efficacy.

Overall, the iterative design approach enabled systematic refinement through cycles of prototyping, testing, and revising. This approach ensured the escape room maintained a robust alignment between educational objectives and game mechanics, optimizing user engagement and learning effectiveness. Key iterative changes included simplified puzzle instructions, balanced puzzle difficulty, enhanced narrative coherence, and dynamic feedback mechanisms, directly addressing initial concerns and significantly improving the educational impact and usability of the final escape room design.

3.3. Output Phase: Implementation and Validation

3.3.1. Serious Game Implementation and Validation

In the Output phase the fully developed cybersecurity governance escape room was realized, and a cycle of evaluation and feedback ensured its effectiveness. This phase began with the Serious Game Implementation, assembling all the designed puzzles, narrative elements, and technical components into a cohesive virtual escape room experience. The game was built according to the specifications and mappings from the Core Process, resulting in a functional prototype that could be deployed in a classroom or training setting.

Next, we conducted a Learning Outcome Analysis and Validation study to verify that playing the escape room indeed achieved the pedagogical objectives set out in the planning phase. This validation involved qualitative and quantitative evaluation methods (as detailed in the Evaluation section of the paper): for example, in some cases, we gathered data on players’ performance in the game (which puzzles they solved, hints used, etc.), administered pre- and post-game assessments of their governance knowledge, and collected feedback through surveys and debriefing interviews.

3.3.2. Iterative refinements

By analyzing this data, we could determine whether each governance competency was addressed (e.g., did students show improvement in understanding policy frameworks or risk assessment after the game?). Where the outcomes fell short, we looped back into minor revisions of the game design, as shown in

Figure 1, where the Feedback Integration element feeds into the validation and implementation boxes.

Concretely, early testing with a small student group and a subject-matter expert revealed a few issues (for instance, one puzzle on compliance standards was too difficult and caused frustration). We responded by adjusting that puzzle (simplifying the clues and adding an in-game hint), illustrating how feedback was incorporated to refine the final output. This iterative improvement continued until the escape room met its learning objectives with a high degree of learner engagement and satisfaction.

3.3.3. Final deliverables

The Output phase thus produced the final deliverables of the project: (a) the implemented escape room game (ready for broader use in cybersecurity education), and (b) a set of validation results and feedback insights demonstrating the game’s educational effectiveness. By the end of the phase, we had a validated serious game that was both pedagogically effective and practically viable.

This validation was in the form of an in-class activity for Master of Cyber Security students taught online at UNSW. Through an in-class evaluation, this validation shows the effectiveness of the game’s implementation. Unlike many existing cybersecurity games that lack explicit connections to learning theories or focus only on technical skills, our escape room embodies a research-based design linking every game element to an educational purpose (

Appendix B).

Moreover, the inclusion of governance content and alignment with industry standards throughout the design process addresses a noted gap in cybersecurity education games; few prior works in cybersecurity education have targeted governance and policy skills in an immersive, gamified format. Our methodology’s strong foundation in constructivist principles and the LM–GM mapping framework demonstrates a level of design rigor and intentionality that is a novel contribution to serious game research in this domain.

In sum, this three-phase approach ensured that the game development was driven by pedagogy and validated by evidence, yielding an escape room that not only engages players but also reliably imparts key cybersecurity governance competencies. This structured, theory-informed design process can serve as a model for future serious game developments in cybersecurity and beyond, showing how careful mapping of learning objectives to game mechanics, coupled with iterative testing and feedback, can produce effective and innovative educational tools.

4. Development of UNSW Cyber Escape Room

The UNSW Cyber Escape Room represents a game-based learning environment designed to enhance cybersecurity education in governance, policy, and risk management. In this section, we presented the development stages including game architecture problem sets.

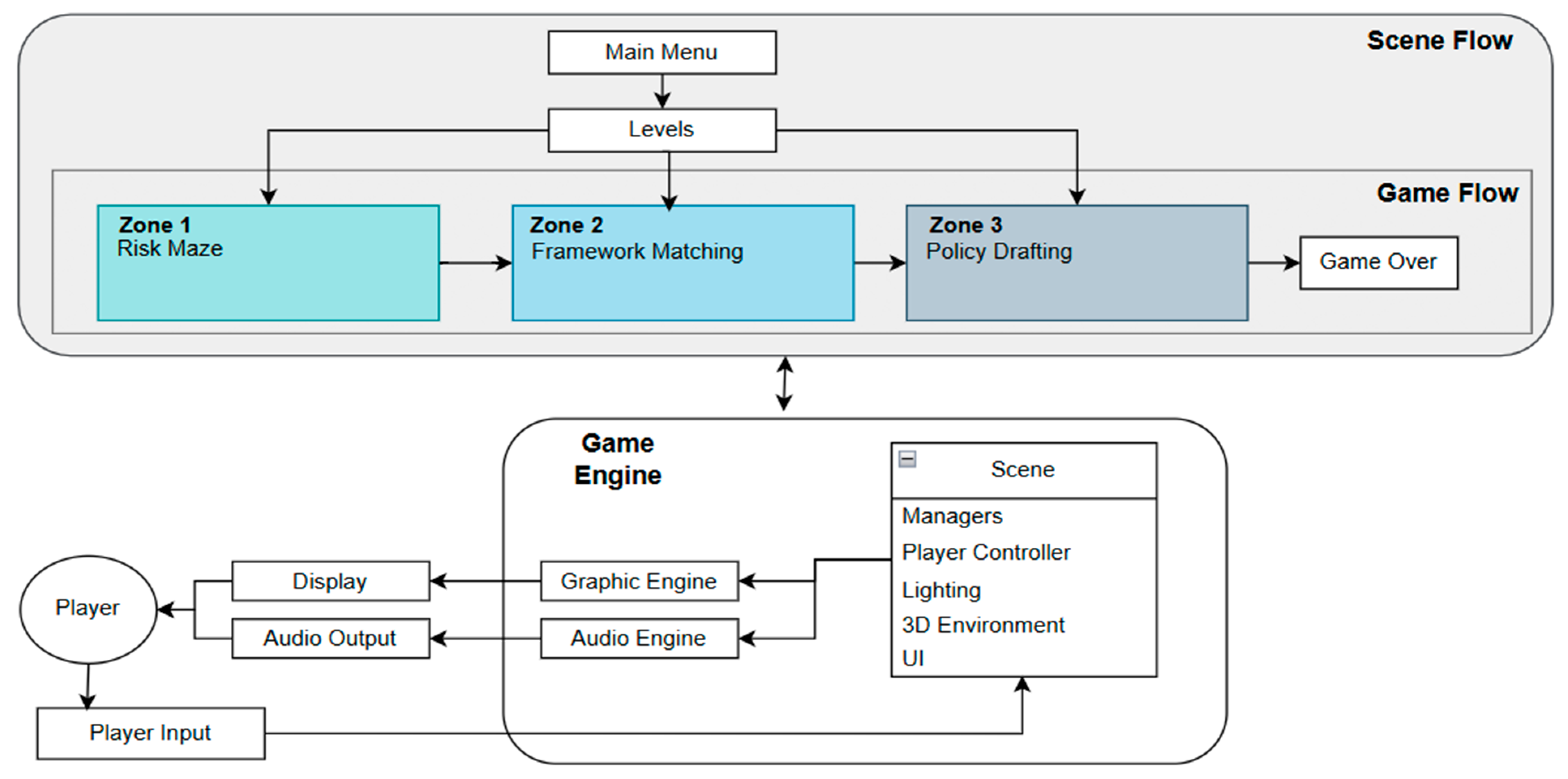

4.1. Game Architecture Overview

The game environment consists of several individual rooms, each representing a different aspect of cybersecurity, governance, policy, or risk management. Students can either work alone or work collaboratively, sharing a common screen in classroom settings to solve puzzles, decipher clues, and apply their knowledge of cybersecurity Governance and Policy concepts to progress through the game.

The architecture of the cybersecurity governance escape room was systematically designed to integrate pedagogical principles with immersive game mechanics. As illustrated in

Figure 2, the architecture comprises two primary layers: the Scene Flow and the Game Engine.

The Scene Flow governs the game’s narrative structure and progression. It begins with a Main Menu, allowing players to navigate different levels. The Game Engine underpins the functional aspects of the game, handling both graphical and computational components. The engine includes the following subsystems:

Graphic Engine: Responsible for rendering the virtual environment and visual elements.

Audio Engine: Manages sound effects and auditory feedback, enhancing engagement.

Scene Management: Governs different game environments, including player interactions, lighting, and UI components.

Player Controller: Facilitates user input and interaction, allowing players to navigate the escape room effectively.

The Player Interaction Loop ensures real-time engagement, integrating user inputs with graphical and auditory feedback mechanisms. Players interact with the system through inputs, which are processed by the game engine, triggering responsive audiovisual outputs that drive gameplay progression. This architecture fosters an engaging yet structured learning experience, seamlessly integrating educational objectives with dynamic gameplay elements.

4.2. Problem Formulation and Game Mechanics

The Scene Flow governs the game’s narrative structure and progression. It begins with a Main Menu (i.e., Landing Page), allowing players to navigate to learn instructions on gameplay. The game consists of three sequential zones:

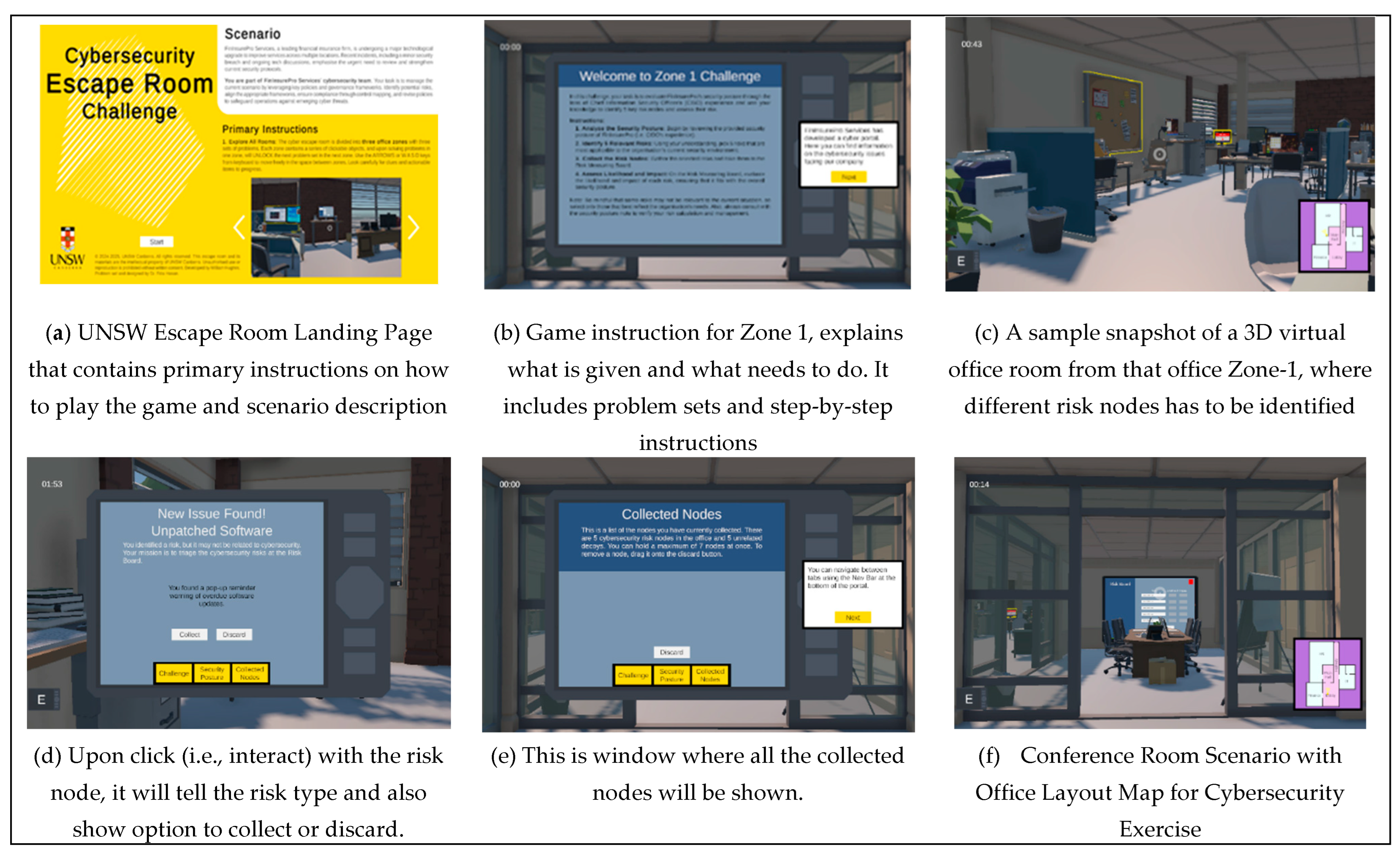

Figure 3.

Snap of various stages of the developed UNSW Escape Room: Zone-1 Game Scenario and Game Mechanics.

Figure 3.

Snap of various stages of the developed UNSW Escape Room: Zone-1 Game Scenario and Game Mechanics.

Zone 1 - Risk Maze: The Risk Maze zone employs spatial navigation mechanics to develop students' ability to identify and prioritize cybersecurity risks in organizational contexts. This zone utilizes the following mechanics:

Problem-based scenarios: Each room section presents context-specific risk scenarios derived from industry case studies, requiring students to apply the NIST Risk Management Framework methodology.

Progressive complexity structure: Challenges increase in complexity through a scaffolded approach, beginning with straightforward risk identification tasks and advancing to scenarios requiring nuanced trade-off decisions between competing security priorities.

Interactive decision points: At key junctures, students encounter interactive terminals that require risk classification according to industry standard matrices (likelihood × impact), with immediate feedback mechanisms that explain misalignments.

Visual metaphor integration: The physical layout of the maze visually reinforces risk management concepts, with path blockages representing security controls and alternative routes demonstrating risk acceptance strategies.

Technical implementation includes proximity-triggered event systems, rule-based evaluation algorithms for student responses, and dynamic feedback delivery through in-game interfaces. Each risk scenario is mapped to specific learning objectives from established cybersecurity governance frameworks (NIST CSF, ISO 27001), ensuring curriculum alignment.

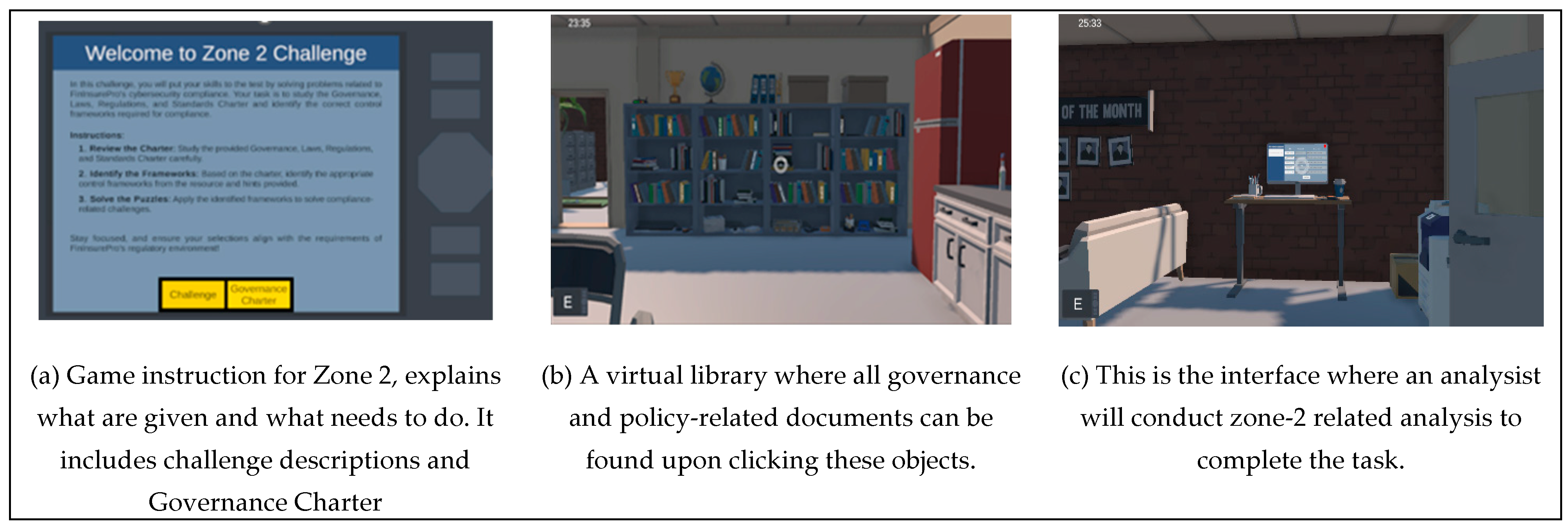

Zone 2 - Framework Matching: The Framework Matching zone reinforces students' understanding of cybersecurity governance frameworks through classification and pattern recognition mechanics. This zone incorporates:

Sorting and classification mechanics: Interactive panels require students to match security controls to appropriate frameworks (e.g., NIST CSF, ISO 27001, GDPR), with increasing complexity as students’ progress.

Framework comparison challenges: Advanced puzzles require identifying overlapping requirements across different standards, highlighting commonalities and differences in approaches.

Contextual application scenarios: Industry-specific vignettes require students to identify which frameworks apply in different regulatory environments, with failure triggering remedial information.

Terminology recognition exercises: Students must recognize framework-specific terminology and requirements through a series of matching challenges with time constraints.

Implementation leverages a database of framework controls mapped to specific requirements, a rule-based evaluation engine that assesses student sorting accuracy, and adaptive difficulty adjustment based on performance metrics. Visual feedback mechanisms indicate correct and incorrect associations, with the system tracking performance to adjust subsequent challenge difficulty.

Figure 4.

Snap of various stages of the developed game from Zone 2.

Figure 4.

Snap of various stages of the developed game from Zone 2.

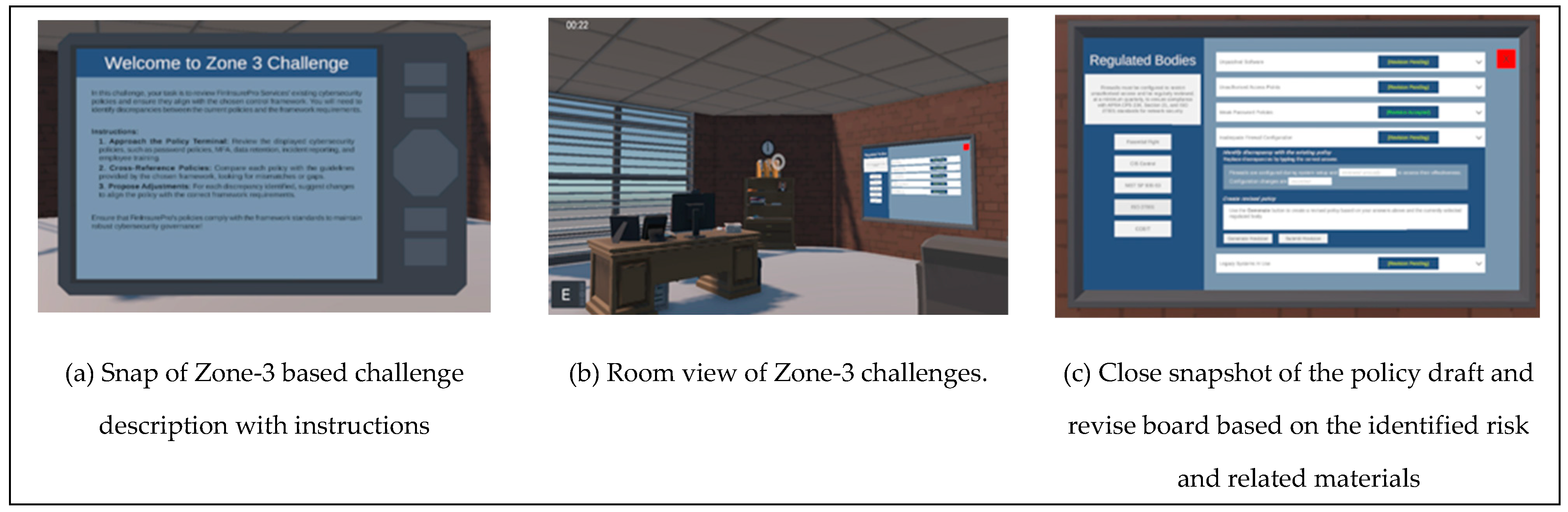

Zone 3 - Policy Revisioning and Drafting: The Policy Drafting zone challenges students to synthesize their knowledge into actionable policy documents through structured composition mechanics:

Template-based composition system: Students work with interactive policy templates containing mandatory elements (scope, roles, compliance requirements, enforcement mechanisms) that must be populated based on previous zone findings.

Component selection mechanics: The interface presents policy element options that students must evaluate and select based on organizational context and identified risks.

Policy evaluation algorithms: The system evaluates drafted policies against multi-dimensional criteria, including completeness, framework alignment, risk coverage, and stakeholder impact.

Revision and feedback loops: Students receive structured feedback on policy drafts, identifying gaps or inconsistencies that require revision before zone completion.

Technical implementation includes a component-based policy assembly system, rule-based validation engines that evaluate policy completeness and effectiveness, and visual indicators that highlight gaps in coverage. The system maintains coherence across zones by requiring policies to address specific risks identified in Zone 1 and incorporate appropriate frameworks from Zone 2.

Figure 5.

Snap of various stages of the developed game from Zone 3.

Figure 5.

Snap of various stages of the developed game from Zone 3.

The zone employs a structured policy template with interactive elements that guide students through the policy creation process while allowing creative problem-solving within governance constraints. Technically, this is implemented through a component-based system where students select and arrange policy elements from a pre-validated library of options, with the game engine evaluating policy completeness based on the inclusion of essential components such as scope, roles, and responsibilities, compliance requirements, and enforcement mechanisms. The system uses rule-based validation to ensure policies address the specific risks identified in Zone 1 and incorporate appropriate frameworks from Zone 2, creating a cohesive learning progression across all three zones. Real-time feedback is provided through visual indicators that highlight gaps or inconsistencies in the drafted policies, prompting students to refine their work until it meets the established criteria for effectiveness.

5. Evaluation, Results, and Discussion

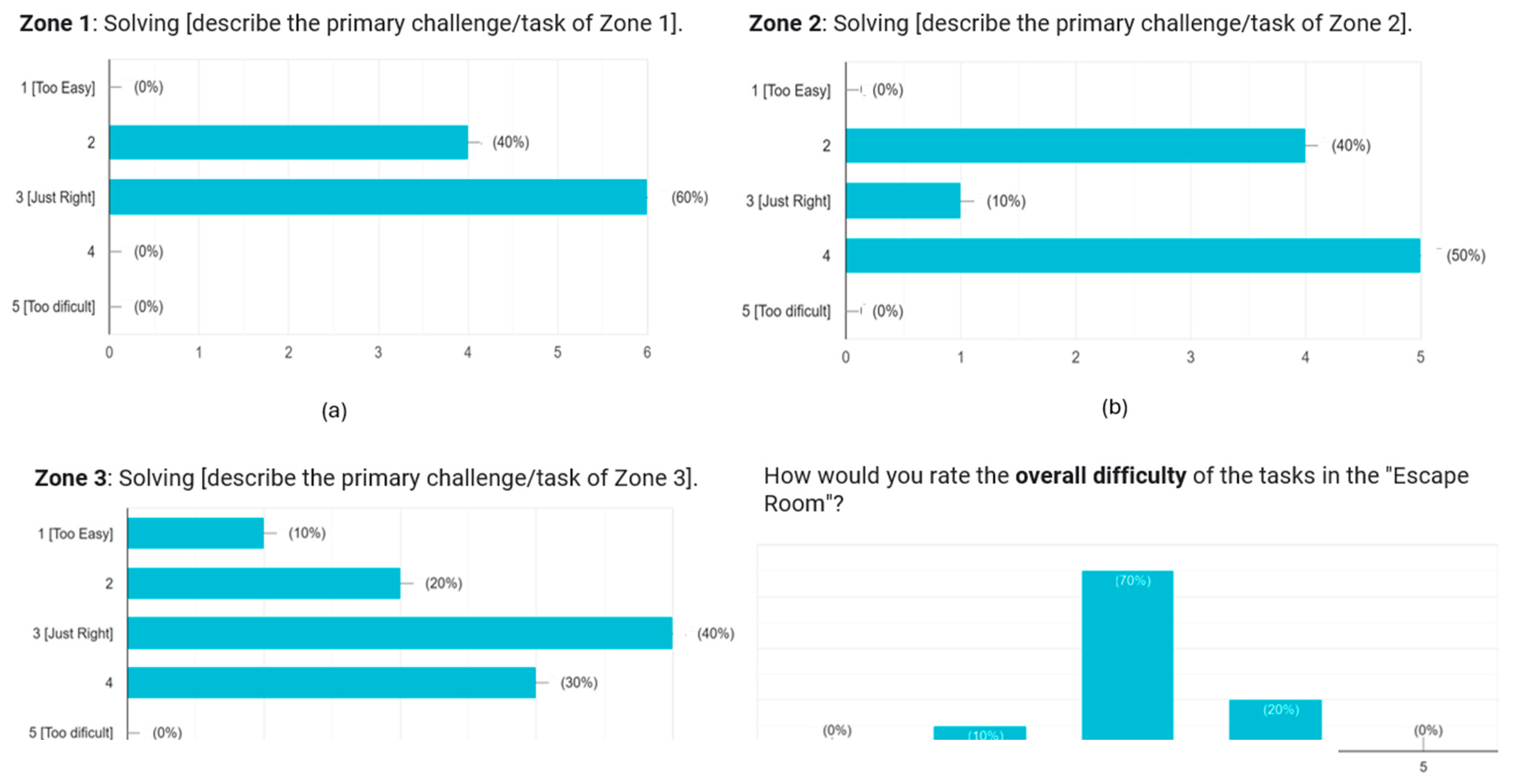

To evaluate the effectiveness of the virtual escape room in teaching cybersecurity governance and policy, an in-class activity and post-session survey were conducted. The evaluation focused on four key areas: student engagement, motivation, perceived difficulty, and overall learning effectiveness.

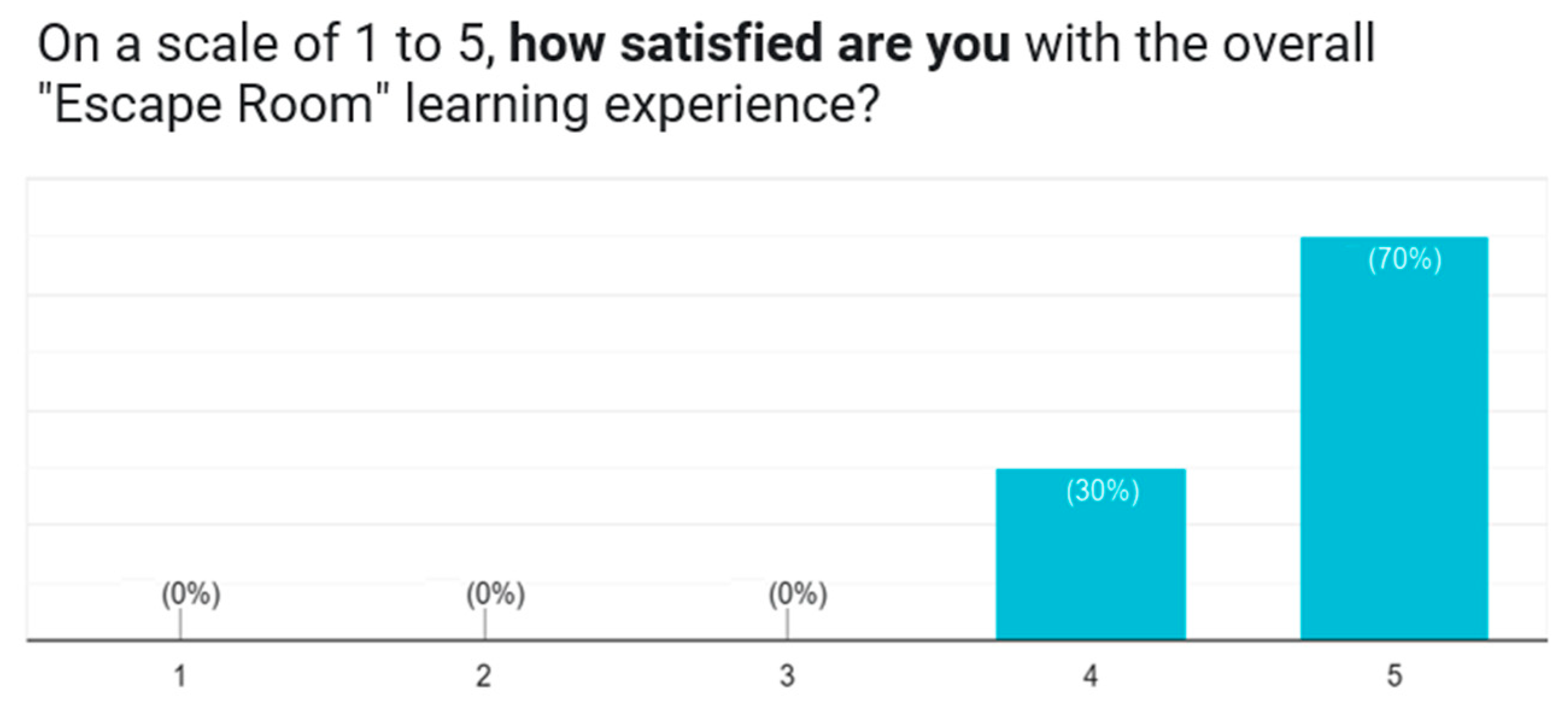

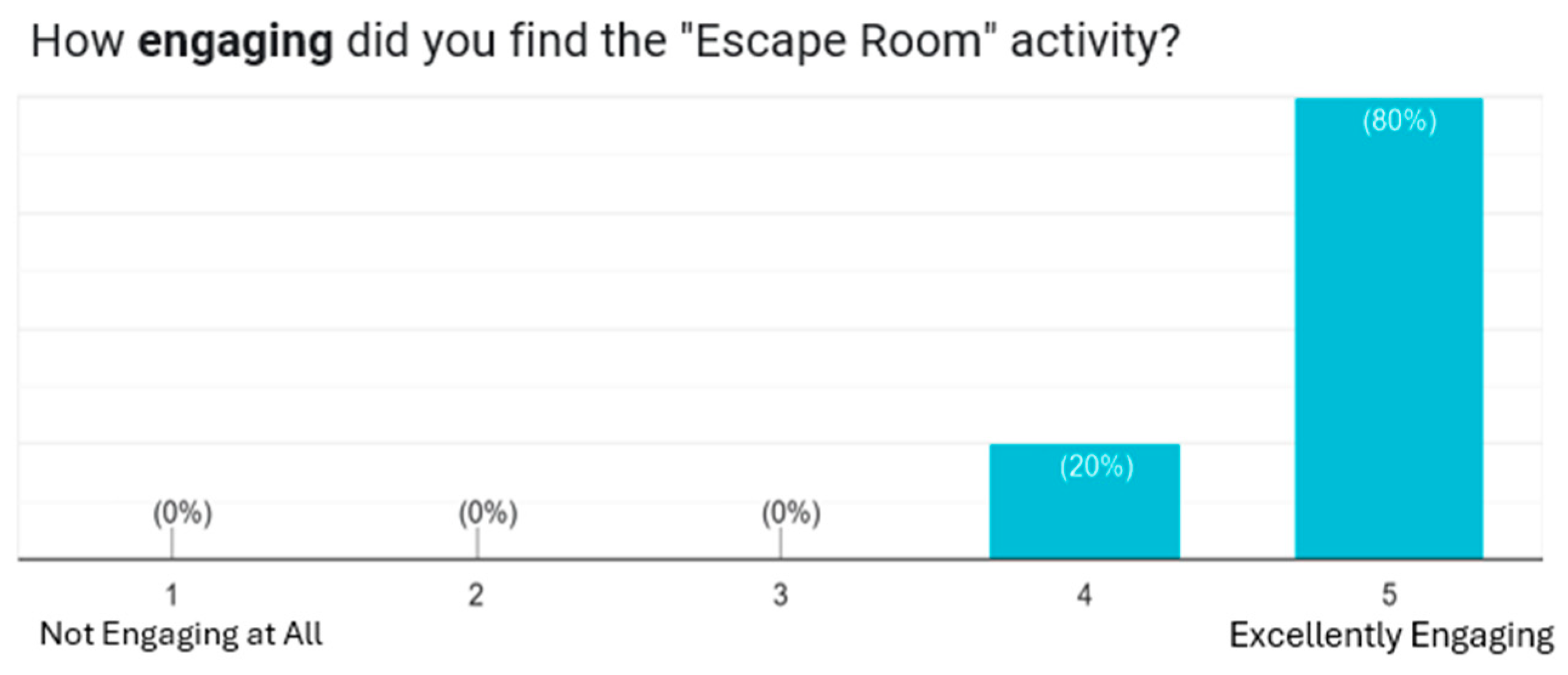

Student engagement was assessed through a structured survey administered to a class of 20 cybersecurity students at UNSW during Term 3, 2025. In response to the question "How engaging did you find the Escape Room activity?", 80% of students gave the highest rating (5), while the remaining 20% rated it as 4 (

Figure 6). These results suggest a high level of engagement with the activity.

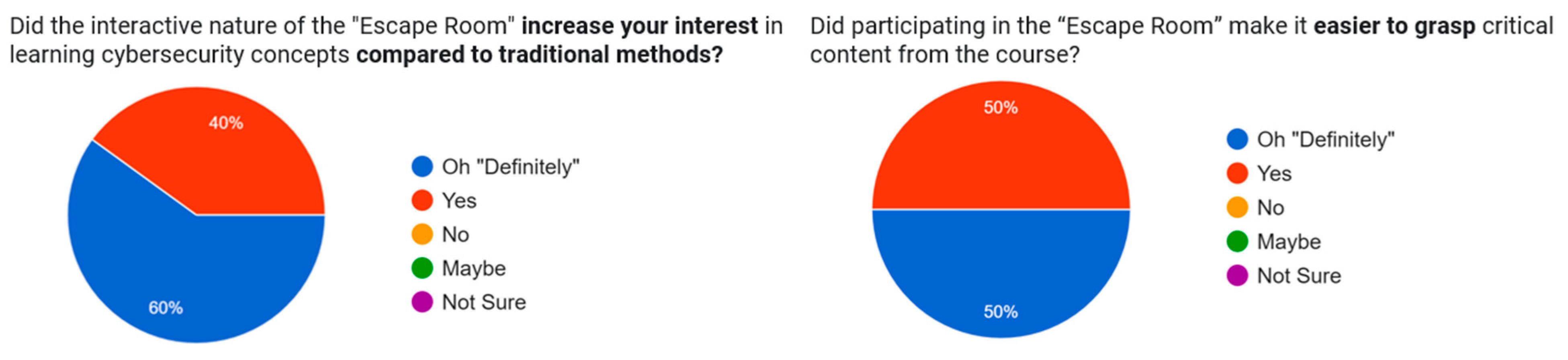

When asked whether the interactive nature of the escape room increased their interest in learning cybersecurity concepts compared to traditional methods, all students responded positively. Specifically, 60% selected "Oh Definitely" and 40% chose "Yes", indicating a strong motivational impact (

Figure 7a). Similarly, in response to the question "Did participating in the Escape Room make it easier to grasp critical content from the course?", all students affirmed the positive impact (

Figure 7b). This feedback highlights the effectiveness of interactive, game-based learning approaches in enhancing student motivation for learning complex topics such as cybersecurity governance.

Another important aspect of our evaluation focused on the difficulty calibration of the escape room challenges. Students were asked to assess the difficulty level of the activities, providing insights into whether the challenges were appropriately calibrated for their knowledge level and learning progression. The feedback regarding difficulty level suggests that the escape room achieved an appropriate balance between challenge and accessibility. Most students rated the difficulty in the mid-range of the scale, indicating that the activities were neither too simple to be engaging nor too complex to be discouraging. This balanced difficulty level is particularly important in educational games, where excessive difficulty can lead to frustration and disengagement, while insufficient challenge can result in limited learning outcomes. The progressive difficulty structure across the three zones (Risk Maze, Framework Matching, and Policy Drafting) appears to have been effective in scaffolding students' learning experiences. This structured progression allowed students to build confidence with foundational concepts before engaging with more complex governance challenges, contributing to the overall positive engagement metrics metrics (Andrew J.A. Seyderhelm and Karen L. Blackmore, 2023).

Figure 8.

Student's Survey on Difficulty Calibration.

Figure 8.

Student's Survey on Difficulty Calibration.

Figure 9.

Student's Survey on overall satisfaction.

Figure 9.

Student's Survey on overall satisfaction.

Additionally, overall satisfaction with the escape room experience was measured through the question, "On a scale of 1 to 5, how satisfied are you with the overall Escape Room learning experience?"

Responses indicated notably high satisfaction, with 70% of students rating their satisfaction at the highest level (5), and 21.4% rating it as 4. Only a small minority (7.1%) expressed dissatisfaction with a rating of 1, as depicted in

Figure 7.

Overall, the survey data indicates that the escape room format effectively supported our core development philosophy of enhancing student engagement with cybersecurity governance and policy concepts, which are often perceived as abstract and less engaging in traditional lecture formats. The strong positive response regarding increased interest in learning cybersecurity concepts demonstrates that the gamified approach effectively overcame engagement barriers associated with these topics.

While our evaluation is limited by the sample size and scope of feedback collected, the consistently positive responses suggest that the escape room format offers a promising approach to cybersecurity governance education. The interactive nature of the experience transforms abstract concepts into engaging learning activities that resonate with students while providing assessment opportunities resistant to generative AI circumvention through their dynamic, contextual nature.

6. Conclusion and Future Work

This paper introduces the UNSW Cyber Escape Room, an innovative virtual experience tailored for cybersecurity governance and policy education. Built as a 3D virtual environment, it realistically simulates a virtual company to guide students through risk-informed policy development. The escape room comprises three progressive zones: Risk Maze, Framework Matching, and Policy Drafting. Each zone presents interactive, scenario-based challenges designed to effectively connect theoretical cybersecurity concepts with real-world practical applications. Student responses to the structured post-activity survey reported high levels of engagement and enthusiasm toward the learning experience. The game's calibrated difficulty level was perceived as appropriately challenging, promoting active involvement and critical thinking. Moreover, the design of the activity supports academic integrity through its inherent resistance to generative AI misuse in assessment contexts. The methodological approach employed, integrating clear learning objectives, interactive gameplay, and iterative refinements, provides a flexible framework adaptable to diverse educational settings. Future research should explore detailed assessments of knowledge gains, skill progression, and long-term retention to further demonstrate the value and effectiveness of gamification in cybersecurity education.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, KFH, and WH; methodology, KFH and WH; software, KFH and WH.; validation, CC and ST; formal analysis, KFH, AR, CC and ST; investigation, KFH, WH, AR; resources, KFH and WH; data curation, KFH, AR, ST; writing—original draft preparation, KFH and AR.; writing—review and editing, KFH, AR, CC and ST; visualization, KFH, AR.; project administration, KFH; funding acquisition, KFH. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Ethical approval for this research was granted by the University of New South Wales (UNSW) Human Research Ethics Committee (Reference Number: iRECS9450) for the project titled “Escape Room Survey CSPS.”

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the CDI Fund and the UNSW Canberra Education Innovation Grant 2025, University of New South Wales (UNSW), which made this research possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

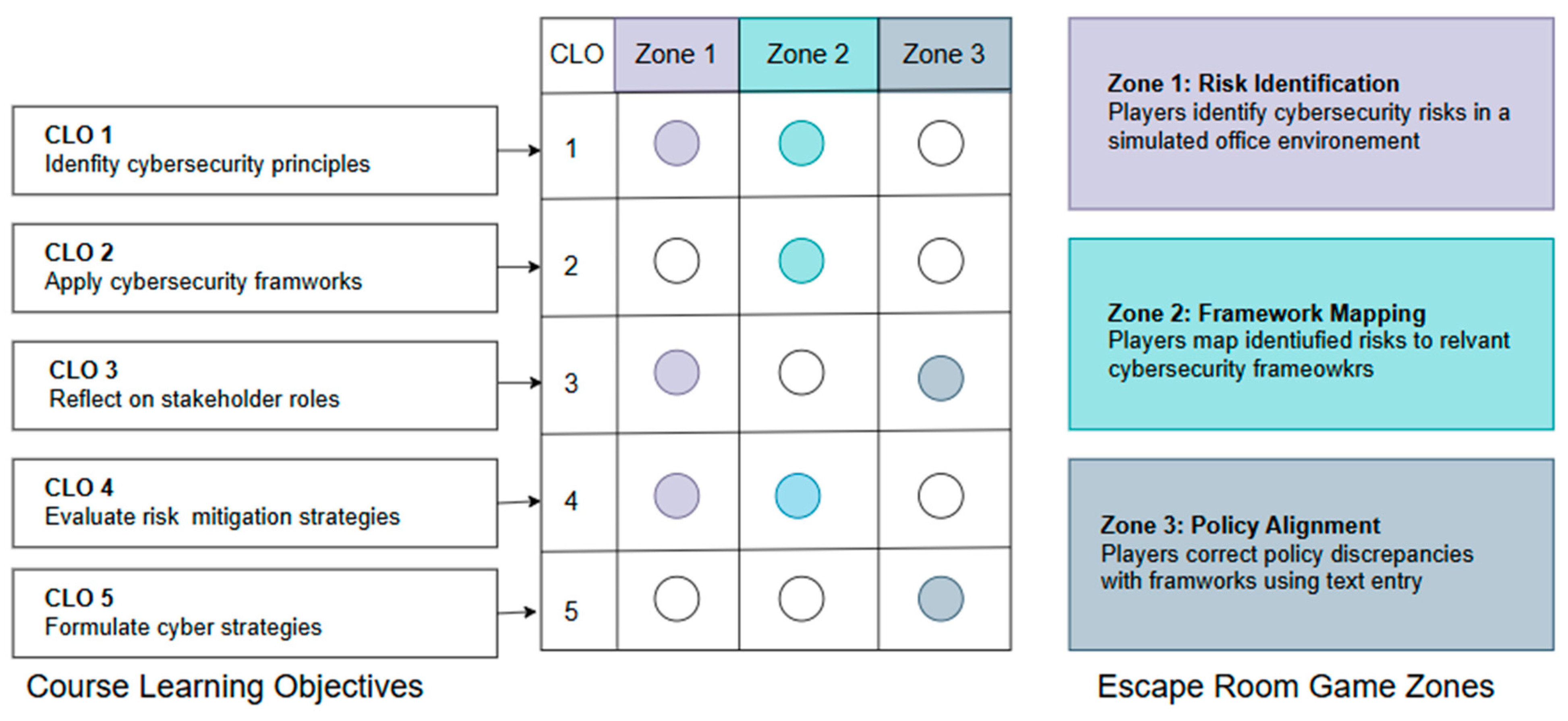

Appendix A. Learning Objectives and Game Mechanics Mapping

This appendix illustrates how the UNSW Cyber Escape Room systematically addresses course learning objectives (CLOs) through specific game mechanics implemented across three sequential zones.

Figure 4 provides a visual mapping of these relationships.

Figure 10.

Course Learning Objectives to Escape Room Game Zones Mapping.

Figure 10.

Course Learning Objectives to Escape Room Game Zones Mapping.

The escape room's architecture employs targeted game mechanics to operationalize each learning objective:

Zone 1: Risk Identification implements CLO1, CLO3, and CLO4 by placing players in a simulated office environment where they must identify cybersecurity risks and evaluate their impact and likelihood. This zone presents cybersecurity from a bottom-up employee perspective, supporting reflection on stakeholder roles (CLO3) while providing contextual framing for risk evaluation (CLO4).

Zone 2: Framework Mapping addresses CLO1, CLO2, and CLO4 through mechanics that require players to correlate previously identified risks with appropriate cybersecurity frameworks. Players must read framework descriptions and use dropdown interfaces to match frameworks with specific risks, demonstrating their ability to apply governance frameworks in context (CLO2) while evaluating mitigation strategies (CLO4).

Zone 3: Policy Alignment focuses on CLO3 and CLO5 by shifting to the policy maker's perspective. Players identify and correct inconsistencies in cybersecurity policies using text entry fields. This practical application requires formulating appropriate policy responses based on the frameworks established in Zone 2, directly supporting CLO5's emphasis on policy development.

The sequential progression through these zones creates an integrated learning experience where knowledge from earlier zones informs tasks in subsequent zones. This design ensures comprehensive coverage of all course learning objectives while reinforcing connections between risk identification, framework application, and policy formulation in cybersecurity governance.

Appendix B. Mapping of Game Elements to Learning Theories

This appendix provides a detailed mapping between specific elements of the UNSW Cyber Escape Room and the learning theories explicitly mentioned in the paper that informed their design.

| Game Element |

Implementation Details |

Supporting Learning Theory |

Theoretical Principle Applied |

| Progressive Zone Structure |

Three sequential zones with increasing complexity (Risk Maze → Framework Mapping → Policy Alignment) |

Constructivism |

Zone of Proximal Development: Challenges begin with basic governance concepts and gradually progress to more complex problems |

| Bottom-up to Policy Maker Perspective Shift |

Zone 1 (employee perspective) to Zone 3 (policy maker perspective) |

Constructivism |

Cognitive Conflict: Players experience both employee and policy-maker viewpoints, leading to deeper understanding through reconciling different perspectives |

| Interactive Risk Nodes |

Clickable elements in Zone 1 requiring classification by impact and likelihood |

Learning Mechanics-Game Mechanics model |

Explicit mapping of learning objective (risk evaluation) to game mechanics (classification) |

| Framework Description Analysis |

Reading and matching frameworks to risks using dropdowns in Zone 2 |

Learning Mechanics-Game Mechanics model |

Learning mechanics (analyzing frameworks) mapped to game mechanics (selection interface) |

| Calibrated Challenge Progression |

Progressive difficulty structure from Zone 1 through Zone 3 |

Flow Theory |

Challenge-Skill Balance: Maintaining engagement through optimal difficulty calibration |

| Policy Correction Mechanics |

Text-entry fields for revising inconsistent policies in Zone 3 |

Learning Mechanics-Game Mechanics model |

Learning mechanics (policy formulation) mapped to game mechanics (text entry composition) |

| Interactive Risk Nodes |

Clickable elements in Zone 1 requiring classification by impact and likelihood |

Learning Mechanics-Game Mechanics model |

Explicit mapping of learning objective (risk evaluation) to game mechanics (classification) |

This mapping demonstrates how the UNSW Cyber Escape Room systematically applies theoretical principles to create an educational experience where each zone's mechanics directly support specific learning objectives. By grounding design choices in established learning theories including constructivism, flow theory, and the LM-GM model, the escape room creates a research-based learning environment where every interactive element serves a specific pedagogical purpose aligned with course learning objectives.

References

- Abdelghani, R., Sauzéon, H., & Oudeyer, P.-Y. (2023). Generative AI in the Classroom: Can Students Remain Active Learners? arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.03192.

- Abt, C. C. (1987). Serious games. University press of America.

- Andrew J.A. Seyderhelm and Karen L. Blackmore, P. (2023). How Hard Is It Really? Assessing Game-Task Difficulty Through Real-Time Measures of Performance and Cognitive Load. Sage Journals.

- Arias-Calderón, M., Castro, J., & Gayol, S. (2022). Serious games as a method for enhancing learning engagement: Student perception on online higher education during COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 889975.

- Arnab, S., Lim, T., Carvalho, M. B., Bellotti, F., De Freitas, S., Louchart, S., Suttie, N., Berta, R., & De Gloria, A. (2015). Mapping learning and game mechanics for serious games analysis. British journal of educational technology, 46(2), 391-411.

- Becker, K. (2021). What’s the difference between gamification, serious games, educational games, and game-based learning. Academia Letters, 209(2), 1-4.

- Bond, M., Zawacki-Richter, O., & Nichols, M. (2019). Revisiting five decades of educational technology research: A content and authorship analysis of the British Journal of Educational Technology. British journal of educational technology, 50(1), 12-63.

- Boyle, E. A., Hainey, T., Connolly, T. M., Gray, G., Earp, J., Ott, M., Lim, T., Ninaus, M., Ribeiro, C., & Pereira, J. (2016). An update to the systematic literature review of empirical evidence of the impacts and outcomes of computer games and serious games. Computers & Education, 94, 178-192.

- Calvano, M., Caruso, F., Curci, A., Piccinno, A., & Rossano, V. (2023). A Rapid Review on Serious Games for Cybersecurity Education: Are" Serious" and Gaming Aspects Well Balanced? IS-EUD Workshops,.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. Haper and Row.

- Efgivia, M. G., Rinanda, R. A., Hidayat, A., Maulana, I., & Budiarjo, A. (2021). Analysis of constructivism learning theory. 1st UMGESHIC International Seminar on Health, Social Science and Humanities (UMGESHIC-ISHSSH 2020),.

- Forum, W. E. (2025). Global Cybersecurity Outlook 2025. https://reports.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Global_Cybersecurity_Outlook_2025.pdf.

- Fotaris, P., & Mastoras, T. (2019). Escape rooms for learning: A systematic review. Proceedings of the European Conference on Games Based Learning,.

- Gee, J. P. (2003). What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy. Computers in entertainment (CIE), 1(1), 20-20.

- Girard, C., Ecalle, J., & Magnan, A. (2013). Serious games as new educational tools: how effective are they? A meta-analysis of recent studies. Journal of computer assisted learning, 29(3), 207-219.

- Gordillo, A., & López-Fernández, D. (2024). Are educational escape rooms more effective than traditional lectures for teaching software engineering? A randomized controlled trial. IEEE Transactions on Education.

- Hein, G. E. (1991). Constructivist learning theory. Institute for Inquiry, 14.

- Hill Jr, W. A., Fanuel, M., Yuan, X., Zhang, J., & Sajad, S. (2020). A survey of serious games for cybersecurity education and training.

- Hodhod, R., Hardage, H., Abbas, S., & Aldakheel, E. A. (2023). Cyberhero: an adaptive serious game to promote cybersecurity awareness. Electronics, 12(17), 3544.

- Hoernig, S., Ilharco, A., Pereira, P. T., & Pereira, R. (2024). Generative AI and Higher education: Challenges and opportunities. Institute of Public Policy.

- ISC². (2023). Cybersecurity workforce study 2023. https://www.isc2.org/Research/2023-Cybersecurity-Workforce-Study.

- Jaffray, A., Finn, C., & Nurse, J. R. (2021). Sherlocked: A detective-themed serious game for cyber security education. International Symposium on Human Aspects of Information Security and Assurance,.

- Kulshrestha, S., Agrawal, S., Gaurav, D., Chaturvedi, M., Sharma, S., & Bose, R. (2021). Development and validation of serious games for teaching cybersecurity. Serious Games: Joint International Conference, JCSG 2021, Virtual Event, January 12–13, 2022, Proceedings 7,.

- Lim, T., Carvalho, M. B., Bellotti, F., Arnab, S., De Freitas, S., Louchart, S., Suttie, N., Berta, R., & De Gloria, A. (2015). The LM-GM framework for serious games analysis. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh.

- Löffler, E., Schneider, B., Zanwar, T., & Asprion, P. M. (2021). Cysecescape 2.0—a virtual escape room to raise cybersecurity awareness. International Journal of Serious Games, 8(1), 59-70.

- Malcolm Ryan, M. M., Vedant Sansare, Paul Formosa, Deborah Richards, Michael Hitchens. (2020). Design of a Serious Game for Cybersecurity Ethics Training.

- Manuel Arias-Calderón 1, J. C., Silvina Gayol 1. (2022). Serious Games as a Method for Enhancing Learning Engagement: Student Perception on Online Higher Education During COVID-19.

- Michael, D. R., & Chen, S. L. (2005). Serious games: Games that educate, train, and inform. Muska & Lipman/Premier-Trade.

- Nieto-Escamez, F. A., & Roldán-Tapia, M. D. (2021). Gamification as online teaching strategy during COVID-19: A mini-review. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 648552.

- Nikolic, S., Sandison, C., Haque, R., Daniel, S., Grundy, S., Belkina, M., Lyden, S., Hassan, G. M., & Neal, P. (2024). ChatGPT, Copilot, Gemini, SciSpace and Wolfram versus higher education assessments: an updated multi-institutional study of the academic integrity impacts of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) on assessment, teaching and learning in engineering. Australasian journal of engineering education, 29(2), 126-153.

- Nkongolo, M. (2024). CyberMoraba: A game-based approach enhancing cybersecurity awareness.

- Pacheco-Velázquez, E., Salinas-Navarro, D. E., & Ramírez-Montoya, M. S. (2023). Serious games and experiential learning: options for engineering education. International Journal of Serious Games, 10(3), 3-21.

- Papaioannou, T., Kokotos, S. E., & Tsohou, A. (2025). Educational escape rooms for raising information privacy competences: An empirical validation. International Journal of Information Security, 24(3), 1-24.

- Piaget, J. (1976). Piaget’s theory. Springer.

- Pramod, D. (2024). Gamification in cybersecurity education; a state of the art review and research agenda. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education.

- Rawlinson, R. E., & Whitton, N. (2024). Escape rooms as tools for learning through failure. Electronic Journal of e-Learning, 22(4).

- Reddy, M., & Johnson, C. (2024). Games and Gamification: Can Playful Student Engagement Improve Academic Integrity? In Second Handbook of Academic Integrity (pp. 1597-1610). Springer.

- Reigeluth, C. M. (2013). Instructional-design theories and models: A new paradigm of instructional theory, Volume II. Routledge.

- Rieber, L. P. (2005). Multimedia learning in games, simulations, and microworlds. The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning, 549-567.

- Rodríguez-Rivera, P., Rodríguez-Ferrer, J. M., & Manzano-León, A. (2025). Designing digital escape rooms with generative ai in university contexts: A qualitative study. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 9(3), 20.

- Rondon, S., Sassi, F. C., & Furquim de Andrade, C. R. (2013). Computer game-based and traditional learning method: a comparison regarding students’ knowledge retention. BMC medical education, 13, 1-8.

- Scherb, C., Heitz, L. B., Grimberg, F., Grieder, H., & Maurer, M. (2023). A serious game for simulating cyberattacks to teach cybersecurity. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.03062.

- Spatafora, A., Wagemann, M., Sandoval, C., Leisenberg, M., & Vaz de Carvalho, C. (2024). An Educational Escape Room Game to Develop Cybersecurity Skills. Computers, 13(8), 205.

- Stephen Hart a, A. M. a., Federica Paci b, Vladimiro Sassone a. (2020). Riskio: A Serious Game for Cyber Security Awareness and Education.

- Sweetser, P., & Wyeth, P. (2005). GameFlow: a model for evaluating player enjoyment in games. Computers in entertainment (CIE), 3(3), 3-3.

- Veldkamp, A., Van De Grint, L., Knippels, M.-C. P., & Van Joolingen, W. R. (2020). Escape education: A systematic review on escape rooms in education. Educational Research Review, 31, 100364.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes (Vol. 86). Harvard university press.

- Wu, W. H., Hsiao, H. C., Wu, P. L., Lin, C. H., & Huang, S. H. (2012). Investigating the learning-theory foundations of game-based learning: a meta-analysis. Journal of computer assisted learning, 28(3), 265-279.

- Zawacki-Richter, O., Marín, V. I., Bond, M., & Gouverneur, F. (2019). Systematic review of research on artificial intelligence applications in higher education–where are the educators? International journal of educational technology in higher education, 16(1), 1-27.

- Zhonggen, Y. (2019). A meta-analysis of use of serious games in education over a decade. International Journal of Computer Games Technology, 2019(1), 4797032.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).