Research in Context

Evidence before this study: AI systems have demonstrated strong diagnostic performance for selected diabetes complications (eg, autonomous diabetic retinopathy detection) and growing evidence supports AI-enabled diabetic foot assessment using smartphone-based workflows. However, clinic-wide, end-to-end AI models remain uncommon and often lack explicit interoperability, governance, and prospective implementation evaluation plans [

8,

9,

18,

21].

Added value of this study: We provide a detailed blueprint of a fully AI-first diabetes clinic tailored to Saudi Arabia’s high-prevalence context and mature national digital health programmes. We specify minimum data elements, interoperability (FHIR; NPHIES; SeHE), human-in-the-loop safety controls, and a governance pathway aligned with Saudi privacy, cybersecurity, and device regulations [

1,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

Implications of all the available evidence: If implemented with robust governance and rigorous prospective evaluation, an AI-first clinic could accelerate earlier diagnosis, increase complication screening coverage, and reduce complication-related morbidity while standardising evidence-based care across geography. The Saudi context—high burden and rapidly evolving digital infrastructure—offers a practical testbed for scalable, exportable models of AI-enabled chronic disease care [

1,

22,

23].

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes is a leading driver of premature mortality and disability worldwide. In 2024, the IDF estimated 589 million adults aged 20–79 years living with diabetes globally (1 in 9), with 43% undiagnosed; diabetes caused an estimated 3.4 million deaths and global health expenditure reached USD 1.015 trillion [

1]. The burden is amplified by chronic complications that are often preventable or detectable earlier: diabetic kidney disease affects roughly 30–40% of people with diabetes; diabetic foot ulcers occur in an estimated 19–34% over a lifetime; diabetic peripheral neuropathy affects about 30% of people with diabetes globally; and diabetic retinopathy affects about 22% of adults with diabetes, with about 6% having vision-threatening disease [

2,

3,

4,

5].

Saudi Arabia exemplifies this challenge and opportunity. IDF 2024 estimates indicate 5.34 million adults (20–79 years) living with diabetes in Saudi Arabia, an age-standardised prevalence of 23.1%, and 43.6% undiagnosed [

1]. In parallel, Saudi Arabia is investing in national digital transformation: the NPHIES health information exchange and payer–provider interoperability programme, together with unified national identity, e-prescribing, and platform governance, can enable systematic data capture, longitudinal risk stratification, and coordinated care at scale [

16,

17].

Yet safe scaling of AI in routine care requires more than point solutions. It requires interoperable data flows, clinical accountability, privacy and cybersecurity compliance, and prospective evaluation using AI-specific methodological guidance. We therefore propose a clinic-wide “AI-first” model that treats AI as infrastructure rather than an add-on [

10,

11,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

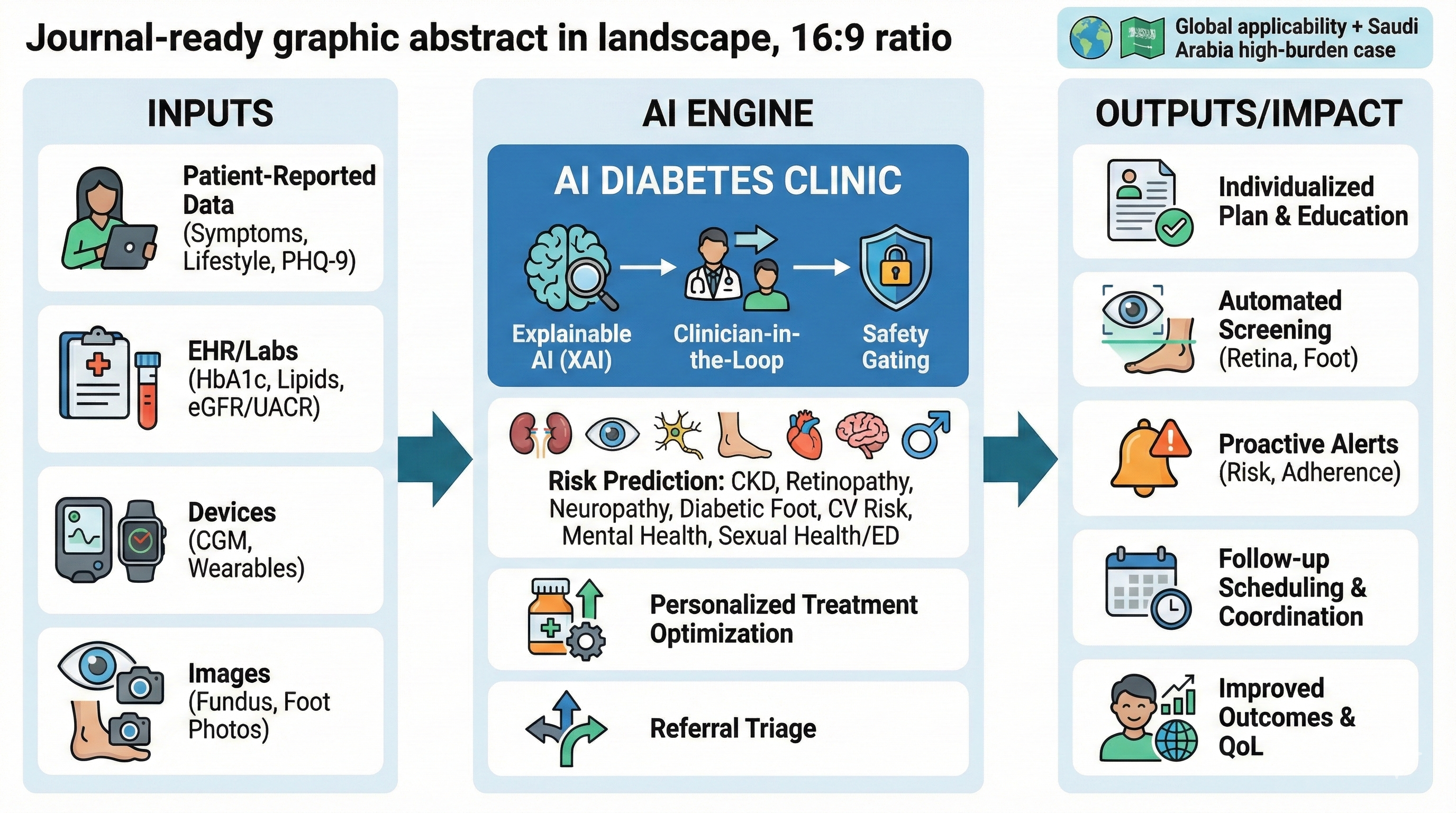

Vision and Objectives

The proposed AI diabetes clinic is designed to: (1) shorten time to diagnosis and risk stratification; (2) optimise personalised treatment aligned with evidence-based guidelines; (3) automate high-frequency screening for retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, and diabetic foot disease; (4) detect deterioration early using continuous data streams; and (5) improve patient experience and equity while protecting privacy and security [

1,

6,

7,

10,

11,

13,

14].

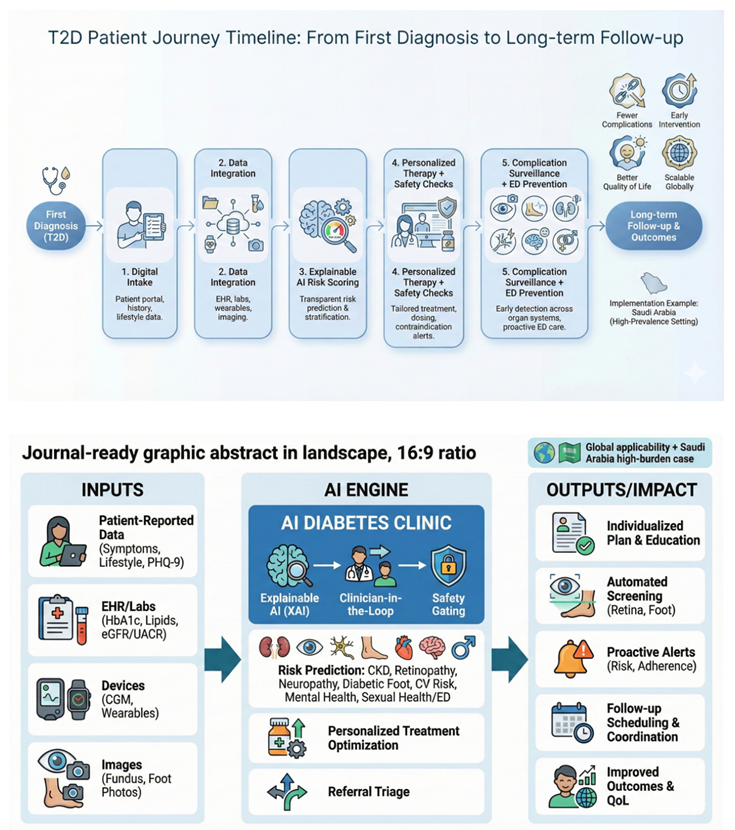

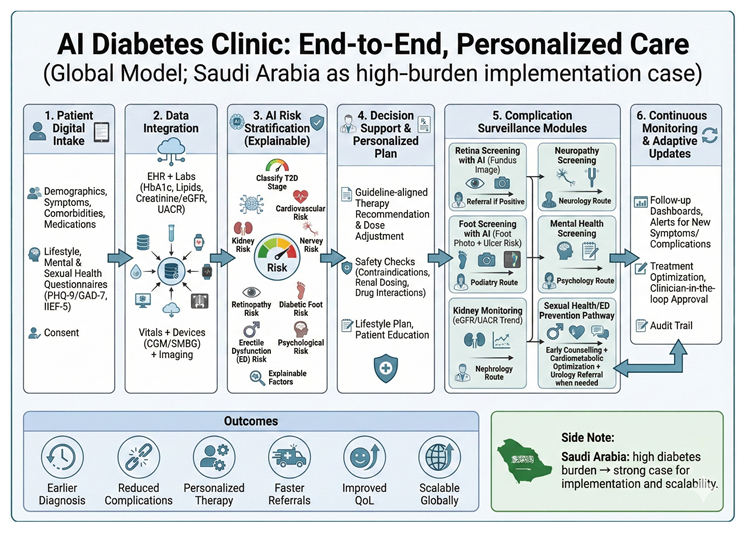

End-to-End Patient Journey

The patient uses a bilingual (Arabic/English) app to create or link a longitudinal profile and complete structured intake: demographics, symptoms, medications, allergies, lifestyle, family history, social determinants, and patient goals. Patients can upload external laboratory results and home-monitoring data when interoperability feeds are unavailable. A structured “concerns” module captures fears (eg, blindness, dialysis, amputation) and preferences that shape shared decision-making [

13,

14].

Before the clinician encounter, AI services ingest intake data and integrate available EHR, lab, imaging, and pharmacy data via a FHIR-based interoperability layer. The system generates a pre-visit summary, problem list, risk stratification, and a draft care plan that the clinician reviews, edits, and signs (human-in-the-loop) [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

Data Layer and Interoperability

Interoperability is foundational. The blueprint assumes a FHIR-based clinical data model for problems, medications, laboratory observations, procedures, and imaging metadata. Alignment with national platforms (NPHIES implementation guides) and health information exchange policies (SeHE) should be treated as early design constraints rather than late-stage integrations [

15,

16,

17].

Minimum dataset elements include HbA1c, fasting plasma glucose, lipids, blood pressure, BMI/waist circumference, eGFR, urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio, liver enzymes, and medication history, plus complications status and screening results (retina, foot, kidney). The AI layer should explicitly model data completeness and uncertainty to avoid unsafe recommendations when safety-critical variables are missing [

6,

7,

18].

Core AI Services

We propose five core AI services: (1) diagnostic confirmation and phenotyping; (2) personalised treatment selection and titration; (3) complication screening (retina, kidney, neuropathy/foot); (4) remote monitoring and early warning; and (5) psychosocial and sexual health triage. Each service operates under clearly defined intended use, performance thresholds, and clinical override rules [

6,

7,

8,

9,

12,

18].

1) Diagnostic Confirmation and Phenotyping

For newly diagnosed or suspected type 2 diabetes, the system validates diagnostic criteria, checks for red flags (eg, possible type 1 diabetes or ketosis risk), and classifies phenotype features relevant to therapy choice: obesity, CKD, ASCVD risk, heart failure risk, hypoglycaemia risk, and frailty. Outputs are evidence-linked and explanation-aware to reduce automation bias [

6,

18].

2) Guideline-Concordant Treatment Optimisation

The treatment engine is a constrained optimisation system: it proposes therapy options and titration plans consistent with current standards, patient preferences, comorbidities, contraindications, and local formulary constraints. Recommendations should be traceable to guideline logic (eg, prioritising cardiovascular and kidney protection where indicated) and include monitoring plans and safety checks [

6,

7,

18].

3) AI-Enabled Screening for Complications

Retinopathy: The clinic deploys AI-assisted fundus imaging to triage and refer patients for ophthalmology review. Autonomous AI models have demonstrated potential to expand screening capacity when embedded into clinical workflows with clear escalation and quality assurance [

8].

Kidney disease: Automated interpretation of eGFR and albuminuria trends supports early detection of CKD progression, medication safety checks, and risk-based follow-up intervals. The clinic should follow evidence-based evaluation and management principles and explicitly manage nephrotoxic exposure and dosing adjustments [

7].

Neuropathy and foot disease: AI-enabled foot assessment can combine structured clinical exam inputs (eg, monofilament, vibration, pulse status) with smartphone imaging and tele-podiatry to identify ulcers and high-risk feet. Large multicentre studies have reported promising performance for AI-based ulcer detection using smartphone and cloud workflows [

9].

4) Remote Monitoring and Early Warning

Remote monitoring integrates glucometer/CGM data, blood pressure, weight, activity, and medication adherence signals. Temporal models flag patterns suggestive of deterioration (eg, rising glucose variability, recurrent hypoglycaemia, rapid weight loss, declining eGFR), prompting nurse outreach or clinician review. Alert thresholds must be calibrated to avoid alarm fatigue, and monitoring performance must be continuously audited [

6,

18,

21].

5) Psychological, Neurological, and Sexual Health Triage

Diabetes care requires systematic detection of depression and anxiety and proactive discussion of sexual dysfunction and neuropathy symptoms. The clinic integrates validated short instruments (PHQ-9, GAD-7, IIEF-5) with AI-assisted triage to behavioural health, sexual medicine, or neurology services, with culturally sensitive workflows and clinician oversight [

26,

27,

28].

Erectile dysfunction (ED) is frequent in men with diabetes; a large meta-analysis reported a pooled prevalence of 52.5% and substantially higher odds compared with controls [

29]. Because ED can precede overt cardiovascular events and may identify men with high cardiometabolic risk, evaluation should incorporate cardiovascular risk assessment and guideline-based triage (including consideration of occult coronary disease when clinically appropriate) [

30]. In the AI diabetes clinic, ED risk prediction combines longitudinal glycaemic exposure, blood pressure, lipids, obesity, smoking, medication profiles, and neuropathy markers with brief patient-reported measures to trigger early counselling, optimisation of cardiometabolic therapy, and timely initiation of first-line ED treatments or referral to urology/andrology as needed [

31,

32].

Clinician Cockpit and Human-in-the-Loop Safety

The clinician cockpit consolidates longitudinal trends, complication screening status, AI-generated summaries with uncertainty estimates, and safety-critical checklists. AI outputs are advisory and require clinician sign-off with audit trails, unless a module is explicitly authorised for autonomous use under regulatory clearance [

12,

18,

21].

Data Governance, Privacy, and Cybersecurity

A clinic-wide AI model concentrates risk if governance is weak. Saudi implementation should adhere to the Personal Data Protection Law implementing regulations, including purpose limitation, lawful processing, and cross-border transfer controls as applicable [

10].

Cybersecurity should meet national baseline expectations (NCA Essential Cybersecurity Controls) and include AI-specific threat modelling (eg, prompt injection, model inversion, supply-chain compromise). Security-by-design should include audit logs, role-based access, encryption at rest and in transit, incident response procedures, and third-party risk management [

11,

14].

Health information exchange and platform governance should align with national policies (SeHE) and payer integration standards (NPHIES) where relevant. The clinic should publish data dictionaries, model cards, and subgroup performance audits to reduce inequitable outcomes [

13,

16,

17,

21].

Regulatory Pathway and Quality Management

AI modules used for diagnosis, screening, or treatment recommendations may be regulated as medical devices (SaMD). Each module’s intended use should be mapped to regulatory classification, and development should follow SFDA guidance for AI/ML-enabled devices, including quality management, clinical evaluation planning, and post-market surveillance [

12].

Telehealth delivery must comply with national telemedicine policy and legal requirements, including clinician licensing, consent, documentation, and escalation pathways for urgent care. This is essential for mixed-mode clinics that blend in-person imaging with remote follow-up [

24,

25].

Evaluation Strategy

Evaluation should proceed in stages. Early-stage testing should follow structured clinical AI implementation and safety guidance, focusing on workflow integration, failure modes, and human factors. Subsequent prospective studies should use pragmatic designs (eg, stepped-wedge or cluster randomised trials) with pre-specified endpoints and AI-specific reporting standards [

18].

Primary outcomes might include change in HbA1c at 6–12 months, time to treatment intensification, screening completion rates for retina/foot/kidney, rate of severe hypoglycaemia, and unplanned diabetes-related acute care. Secondary outcomes should include patient-reported outcomes, equity metrics, and cost-effectiveness [

6,

7,

21].

Model development and validation should be reported with TRIPOD+AI, and clinical trials should use CONSORT-AI and SPIRIT-AI extensions. Continuous monitoring should include dataset shift detection, calibration drift, and real-world performance stratified by subgroup [

19,

20,

21].

Implementation in Saudi Arabia: A Pragmatic Roadmap

Phase 0 (0–3 months): establish governance (clinical safety board, data governance council), map regulatory pathways, and define minimum dataset and interoperability interfaces with EHRs and national platforms [

10,

11,

12,

15,

16,

17].

Phase 1 (3–12 months): deploy patient intake and clinician cockpit, integrate treatment optimisation, and implement AI-enabled pilots for retinopathy and diabetic foot screening in selected primary care sites linked to specialist hubs (eg, SVH services) [

8,

9,

22,

24,

25].

Phase 2 (12–24 months): scale to regional networks, add remote monitoring and psychosocial/sexual health triage, and run a pragmatic trial comparing AI-first clinics with usual care, with continuous post-deployment monitoring and model updating policies [

18,

19,

20,

21,

33].

Scalability and Global Relevance

Although designed for Saudi Arabia, the architecture is intentionally modular and can be adapted to other settings. Countries with fragmented systems can adopt patient-owned intake and screening modules first, then progressively integrate payer and health-information exchange interfaces as infrastructure matures [

1,

15,

18].

Limitations and Open Challenges

Clinic-wide AI risks include automation bias, inequitable performance across subgroups, alert fatigue, and over-reliance on incomplete data. Saudi-specific challenges include variation in data availability across regions, Arabic language model performance, and ensuring privacy and cybersecurity compliance across a multi-vendor ecosystem. These risks mandate staged deployment, strong human oversight, and transparent reporting of real-world performance [

10,

11,

13,

14,

18,

21].

Conclusion

Saudi Arabia’s high diabetes prevalence and rapidly evolving digital-health infrastructure create a timely opportunity to pilot an AI-first diabetes clinic that standardises high-quality care, increases screening coverage, and reduces complications. Success requires governance-by-design, interoperable data, regulation-aware development, and rigorous prospective evaluation. If achieved, the model could become a scalable blueprint for AI-enabled chronic disease care globally [

1,

6,

10,

11,

12,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22].

Patent Notice

Patent owners: Amr Kamel Khalil Ahmed; Sharifa Mohlhal Shani Rodaini.

This concept is registered as a patent and is legally protected. Unauthorised copying, reproduction, distribution, disclosure, publication, or commercial use is prohibited without the written permission of the patent owners.

Author Contributions

AA conceived the study, drafted the manuscript, and approved the final version. Additional contributors to be added upon submission.

Funding

No specific funding was received for this work.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable (conceptual blueprint). Any future prospective evaluation will require local ethics approval and patient consent where relevant.

Data Availability Statement

No individual participant data were generated or analysed in this conceptual manuscript. For future trials, de-identified datasets and code sharing should follow institutional and national policies.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no competing interests.

References

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas (11th edn): Global factsheet (Diabetes around the world—2024); International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2025; Available online: https://diabetesatlas.org/media/uploads/sites/3/2025/04/IDF_Atlas_11th_Edition_2025_Global-Factsheet.pdf (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- McDermott, K.; Fang, M.; Boulton, A.J.M.; Selvin, E.; Hicks, C.W. Etiology, epidemiology, and disparities in the burden of diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Diabetes Federation. Diabetes and kidney disease – 2023. IDF Diabetes Atlas report; International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2023; Available online: https://diabetesatlas.org/media/uploads/sites/3/2025/03/Diabetes-and-kidney-disease-2023.pdf (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- He, H.; Zhu, S. Prevalence of diabetic peripheral neuropathy in the global diabetic population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prim Care Diabetes 2020, 14, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, Z.L.; Tham, Y.C.; Yu, M.; et al. Global prevalence of diabetic retinopathy and projection of burden through 2045: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology published online. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. Standards of Care in Diabetes—2025. Diabetes Care 2025, 48 Suppl 1. Available online: https://ada.silverchair-cdn.com/ada/content_public/journal/care/issue/48/supplement_1/5/toc.pdf (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- KDIGO KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2024, 105(4S). Available online: https://kdigo.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/KDIGO-2024-CKD-Guideline.pdf (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- Abràmoff, M.D.; Lavin, P.T.; Birch, M.; Shah, N.; Folk, J.C. Pivotal trial of an autonomous AI-based diagnostic system for detection of diabetic retinopathy in primary care offices. npj Digit Med. 2018, 1, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artificial intelligence for automated detection of diabetic foot ulcers using smartphone and cloud-based technologies. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2023. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0168822723007143 (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- Saudi Data; AI Authority. Personal Data Protection Law: Implementing Regulation (English); SDAIA: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia,, 2024. Available online: https://sdaia.gov.sa/en/PDPL/Regulations/Personal%20Data%20Protection%20Law%20Implementing%20Regulation.pdf (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- National Cybersecurity Authority (Saudi Arabia). Essential Cybersecurity Controls (ECC-2-2024); NCA: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2024; Available online: https://cdn.nca.gov.sa/api/files/public/upload/da829b21-c4ef-4a6e-9f6e-82690d612ee9_ECC-2-2024-.pdf (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- Saudi Food and Drug Authority. Guidance for the submission of medical device(s) incorporating Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning (MDS-G010); SFDA: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2023. Available online: https://www.sfda.gov.sa/sites/default/files/2023-11/MDS-G010_0.pdf (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- World Health Organization. Ethics and governance of artificial intelligence for health: WHO guidance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/350567/9789240037403-eng.pdf (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. Artificial Intelligence Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0); NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2023. Available online: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/ai/NIST.AI.100-1.pdf (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- HL7. FHIR Release 4 (R4) Specification. HL7. 2019. Available online: https://hl7.org/fhir/R4/ (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- National Health Information Center (Saudi Arabia). NPHIES: Implementation Guides (HL7 FHIR); NHIC: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2025; Available online: https://fhir.nphies.sa/ (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- National Health Information Center (Saudi Arabia). Saudi Health Information Exchange (SeHE): Policies and Frameworks (v1.0); NHIC: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2023. Available online: https://nhic.gov.sa/en/ehealthlegislation/documents/sehe-policy-v1.0.pdf (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- Vasey, B.; Nagendran, M.; Campbell, B.; et al. Reporting guideline for clinical evaluation of AI decision-support systems: DECIDE-AI. Nat Med 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Cruz Rivera, S.; Moher, D.; Calvert, M.J.; Denniston, A.K. SPIRIT-AI; CONSORT-AIWorking Group Reporting guidelines for clinical trials evaluating artificial intelligence interventions: CONSORT-AIextension. BMJ 2020, 370, m3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz Rivera, S.; Liu, X.; Chan, A.-W.; et al. SPIRIT-AI extension: Guidance for clinical trial protocols for interventions involving artificial intelligence. Lancet Digit Health 2020, 2, e549–e560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, G.S.; Dhiman, P.; Andaur Navarro, C.L.; et al. TRIPOD+AI statement: Updated reporting guidance for studies developing, validating, or updating prediction models that use machine learning or artificial intelligence. BMJ 2024. Available online: https://bmj.com/content/385/bmj-2023-078414. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health (Saudi Arabia). Seha Virtual Hospital (SVH); Ministry of Health: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2025. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/Projects/Pages/seha-virtual-hospital.aspx (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- Saudi Press Agency. Guinness World Records records Seha Virtual Hospital as the largest virtual hospital in the world; Saudi Press Agency, 2023; Available online: https://www.spa.gov.sa/en/N2047456 (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- National Health Information Center (Saudi Arabia). Telemedicine Policy; NHIC: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2022. Available online: https://nhic.gov.sa/en/ehealthlegislation/Documents/Telemedicine%20Policy.pdf (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- Ministry of Health (Saudi Arabia). Legal regulations for telehealth services (Telehealth Legal Regulations); Ministry of Health: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2023; Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sa/Ministry/Policies/Documents/Telehealth-Legal-Regulations.pdf (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006, 166(10), 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, R.C.; Cappelleri, J.C.; Smith, M.D.; Lipsky, J.; Peña, B.M. Development and evaluation of an abridged, 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 1999, 11(6), 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouidrat, Y.; Pizzol, D.; Cosco, T.; Thompson, T.; Carnaghi, M.; Bertoldo, A.; et al. High prevalence of erectile dysfunction in diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 145 studies. Diabet Med. 2017, 34(9), 1185–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kloner, R.A.; Burnett, A.L.; Miner, M.; Blaha, M.J.; Ganz, P.; Goldstein, I.; et al. Princeton IV consensus guidelines: PDE5 inhibitors and cardiac health. J Sex Med. 2024, 21(2), 90–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnett, A.L.; Nehra, A.; Breau, R.H.; et al. Erectile dysfunction: AUA guideline. J Urol. 2018, 200(3), 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Association of Urology. EAU Guidelines on Sexual and Reproductive Health: Management of erectile dysfunction. 2025. Available online: Uroweb.org/guidelines/sexual-and-reproductive-health/chapter/management-of-erectile-dysfunction. (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- World Health Organization. Ethics and governance of artificial intelligence for health: Guidance on large multi-modal models; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240084759.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |