Introduction

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) is one of the most prevalent endocrine–metabolic disorders affecting women of reproductive age, with an estimated global prevalence ranging from 6% to 20%, depending on diagnostic criteria [

1]. It is a heterogeneous condition characterized by chronic anovulation, hyperandrogenism, polycystic ovarian morphology, and a strong association with metabolic abnormalities such as insulin resistance, obesity, dyslipidemia, and chronic low-grade inflammation [

2]. Beyond reproductive dysfunction, PCOS significantly increases the risk of long-term complications including type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, endometrial cancer, and psychological disorders. Despite its high prevalence and multifactorial etiology, current therapeutic strategies remain largely symptomatic rather than curative, highlighting the urgent need for targeted and mechanism-based interventions [

3].

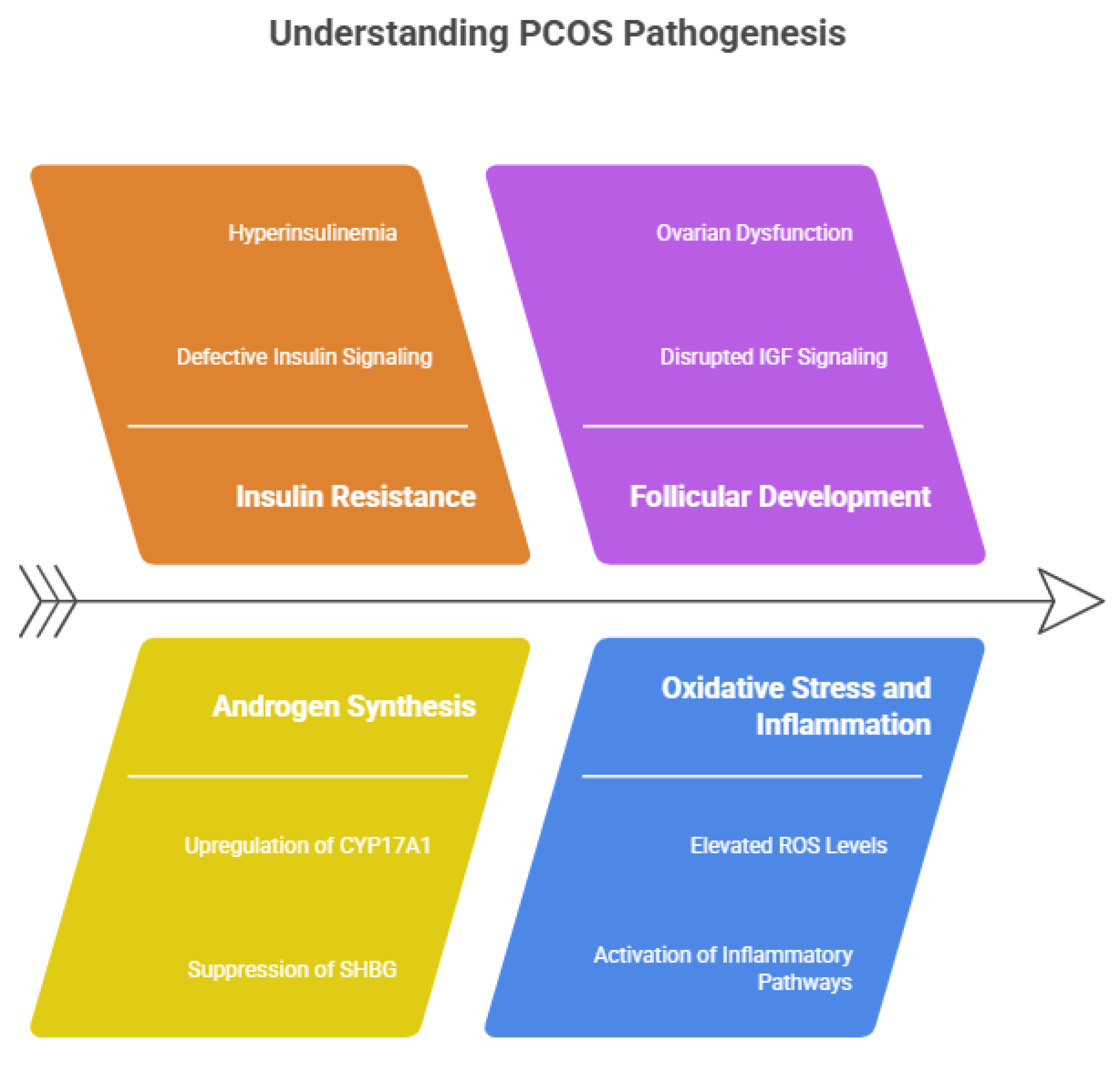

The pathophysiology of PCOS is complex and involves a dysregulated interplay between the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis, insulin signaling pathways, inflammatory mediators, oxidative stress, and altered steroidogenesis [

4]. Hyperinsulinemia exacerbates ovarian androgen production, impairs follicular maturation, and contributes to anovulation. Concurrently, increased oxidative stress and chronic inflammation within ovarian tissue disrupt granulosa cell function and folliculogenesis. These molecular disturbances collectively sustain the vicious cycle of hormonal imbalance and ovarian dysfunction, making PCOS a challenging disorder to manage with conventional mono-targeted therapies [

5].

Current pharmacological treatments for PCOS, including oral contraceptives, metformin, clomiphene citrate, and letrozole, are associated with several limitations such as incomplete efficacy, adverse metabolic effects, poor patient compliance, and contraindications in long-term use [

6]. Moreover, these therapies primarily address clinical symptoms—such as menstrual irregularities, infertility, or hyperandrogenism—without directly targeting the underlying molecular mechanisms like oxidative stress, inflammation, and insulin resistance. This therapeutic gap has intensified interest in alternative and adjunctive strategies that can provide multi-targeted, safer, and more sustainable management of PCOS [

7].

Polyphenolic bioactive compounds, naturally occurring secondary metabolites found abundantly in fruits, vegetables, herbs, and medicinal plants, have gained significant attention for their pleiotropic pharmacological properties [

8]. Compounds such as quercetin, resveratrol, curcumin, epigallocatechin gallate, rutin, and gallic acid exhibit potent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, insulin-sensitizing, anti-androgenic, and endocrine-modulating activities. Preclinical and clinical studies suggest that these polyphenols can restore ovarian function, regulate steroidogenesis, improve insulin sensitivity, and attenuate oxidative stress in PCOS models. However, their clinical translation is severely limited by poor aqueous solubility, low bioavailability, rapid metabolism, and inadequate tissue targeting [

9].

Advances in nanotechnology, particularly polymeric nanoparticle–based drug delivery systems, offer a promising solution to overcome the pharmacokinetic and therapeutic limitations of polyphenolic compounds [

10]. Polymeric nanoparticles fabricated from biocompatible and biodegradable polymers such as PLGA, chitosan, PEG, alginate, and PCL enable controlled release, enhanced stability, improved bioavailability, and targeted delivery of encapsulated bioactives. When loaded with polyphenolic compounds, these nanocarriers can preferentially accumulate in ovarian tissue, protect the payload from degradation, and modulate multiple pathogenic pathways simultaneously, thereby enhancing therapeutic efficacy while minimizing systemic side effects [

11].

In this context, the present systematic review aims to critically evaluate and synthesize existing preclinical and clinical evidence on the use of polyphenolic bioactive compound–based polymeric nanoparticles for targeted management of PCOS. The review focuses on nanoparticle formulation strategies, physicochemical characteristics, mechanisms of action, in-vitro and in-vivo efficacy, safety profiles, and translational potential. By integrating insights from nanomedicine and reproductive endocrinology, this review seeks to highlight emerging therapeutic paradigms, identify current research gaps, and propose future directions for the development of next-generation, targeted nanotherapeutics for PCOS management.

Pathophysiology of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Molecular and Endocrine Dysregulation

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) is a complex, multifactorial endocrine disorder arising from intricate dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian (HPO) axis. One of the hallmark endocrine abnormalities in PCOS is an increased pulsatile secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), leading to elevated luteinizing hormone (LH) levels with relatively normal or suppressed follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). This altered LH/FSH ratio stimulates theca cells in the ovary to produce excess androgens, including testosterone and androstenedione, while insufficient FSH impairs granulosa cell aromatase activity [

12]. As a result, androgen conversion to estrogen is reduced, leading to follicular arrest, anovulation, and the characteristic polycystic ovarian morphology observed in affected individuals.

At the molecular level, insulin resistance plays a central role in the pathogenesis of PCOS, independent of obesity. Defective insulin signaling in skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, and hepatic cells leads to compensatory hyperinsulinemia, which synergistically enhances ovarian androgen synthesis by upregulating cytochrome P450c17 (CYP17A1) activity in theca cells [

13]. Insulin also suppresses hepatic production of sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG), thereby increasing circulating free and biologically active androgens. Furthermore, insulin resistance disrupts follicular development by altering insulin-like growth factor (IGF) signaling pathways within the ovary, exacerbating ovarian dysfunction and contributing to infertility in PCOS patients [

14]. Oxidative stress and chronic low-grade inflammation are increasingly recognized as key contributors to PCOS pathophysiology. Elevated levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), lipid peroxidation products, and pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and C-reactive protein (CRP) have been documented in PCOS [

15]. These mediators impair mitochondrial function in ovarian granulosa cells, induce apoptosis, and disrupt steroidogenic enzyme expression. Additionally, activation of inflammatory signaling pathways, including nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), perpetuates insulin resistance and hyperandrogenism, establishing a self-sustaining pathological loop [

16].

Figure 1.

Molecular insights of PCOS- Pathogensis.

Figure 1.

Molecular insights of PCOS- Pathogensis.

Epigenetic and genetic factors further modulate the molecular landscape of PCOS, contributing to its clinical heterogeneity. Polymorphisms in genes involved in steroidogenesis (CYP11A1, CYP17A1), insulin signaling (INSR, IRS-1), inflammation, and oxidative stress regulation have been associated with increased PCOS susceptibility [

17]. Moreover, epigenetic alterations such as DNA methylation, histone modifications, and dysregulated microRNA expression influence ovarian gene expression, follicular development, and metabolic homeostasis. These molecular perturbations may be triggered or amplified by environmental factors, including diet, endocrine-disrupting chemicals, and intrauterine exposure, emphasizing PCOS as a disorder rooted in both endocrine imbalance and molecular dysregulation [

18].

Therapeutic Limitations of Conventional Pharmacological Approaches in PCOS Management

Conventional pharmacological management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) primarily focuses on symptomatic relief rather than addressing the underlying molecular and metabolic derangements of the disorder [

19]. Commonly prescribed agents such as combined oral contraceptives (COCs), anti-androgens, insulin sensitizers, and ovulation-inducing drugs are selected based on predominant clinical manifestations, including menstrual irregularities, hyperandrogenism, and infertility. While these treatments offer short-term clinical benefits, they fail to correct the complex interplay between insulin resistance, oxidative stress, inflammation, and ovarian dysfunction, resulting in partial efficacy and frequent symptom recurrence upon discontinuation [

20].

Combined oral contraceptives remain the first-line therapy for menstrual regulation and hyperandrogenism; however, their long-term use is associated with several adverse effects, including weight gain, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance aggravation, and an increased risk of thromboembolic events [

21]. Anti-androgenic agents such as spironolactone and flutamide are effective in reducing hirsutism and acne but do not restore ovulatory function and require strict contraception due to teratogenic risks. Moreover, these agents often necessitate prolonged treatment durations, leading to poor patient adherence and concerns regarding hepatic and cardiovascular safety [

22].

Insulin-sensitizing drugs, particularly metformin, are widely used to improve metabolic outcomes in PCOS patients; however, their therapeutic response is highly variable. Gastrointestinal intolerance, vitamin B12 deficiency, and limited impact on hyperandrogenism and fertility outcomes restrict long-term compliance [

23]. Ovulation induction agents such as clomiphene citrate and letrozole, although effective in inducing ovulation, are associated with drawbacks including anti-estrogenic effects on endometrial receptivity, ovarian hyperstimulation, and multiple pregnancies. Additionally, repeated treatment cycles increase the risk of ovarian resistance and diminished responsiveness over time [

24].

Importantly, conventional therapies lack tissue specificity and multi-targeted action, often resulting in systemic side effects and suboptimal ovarian drug exposure. None of the existing pharmacological options directly mitigate oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, or mitochondrial dysfunction at the ovarian level—key drivers of PCOS pathogenesis [

25]. These limitations underscore the pressing need for advanced therapeutic strategies capable of delivering bioactive compounds in a targeted, sustained, and mechanistically integrated manner. Emerging nanotechnology-based interventions, particularly polyphenolic compound–loaded polymeric nanoparticles, offer a promising alternative by enhancing drug bioavailability, reducing systemic toxicity, and simultaneously modulating multiple pathogenic pathways involved in PCOS [

26].

Polyphenolic Bioactive Compounds in PCOS: Sources, Classification, and Pharmacological Relevance

Polyphenolic bioactive compounds are a diverse group of naturally occurring secondary metabolites widely distributed in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, herbs, spices, and medicinal plants. These compounds have garnered increasing attention in the management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) due to their broad-spectrum biological activities and favorable safety profiles [

27]. Dietary sources such as green tea, berries, grapes, citrus fruits, turmeric, onions, apples, and legumes are rich in polyphenols, while traditional medicinal plants including

Camellia sinensis,

Curcuma longa,

Vitis vinifera,

Punica granatum, and

Emblica officinalis serve as concentrated reservoirs. Given the multifactorial nature of PCOS, polyphenols are particularly attractive therapeutic candidates owing to their ability to modulate multiple pathological pathways simultaneously [

28].

Based on their chemical structure, polyphenols are broadly classified into flavonoids, phenolic acids, stilbenes, and lignans. Flavonoids—such as quercetin, kaempferol, rutin, catechins, and epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG)—constitute the largest subgroup and are extensively studied for their antioxidant and endocrine-modulating effects [

29]. Phenolic acids, including gallic acid, caffeic acid, and ferulic acid, exhibit potent free radical scavenging and anti-inflammatory activities. Stilbenes, represented predominantly by resveratrol, and lignans such as secoisolariciresinol further contribute to hormonal balance through estrogen receptor modulation and insulin-sensitizing actions. This structural diversity underpins the wide-ranging pharmacological properties of polyphenolic compounds relevant to PCOS pathophysiology [

30].

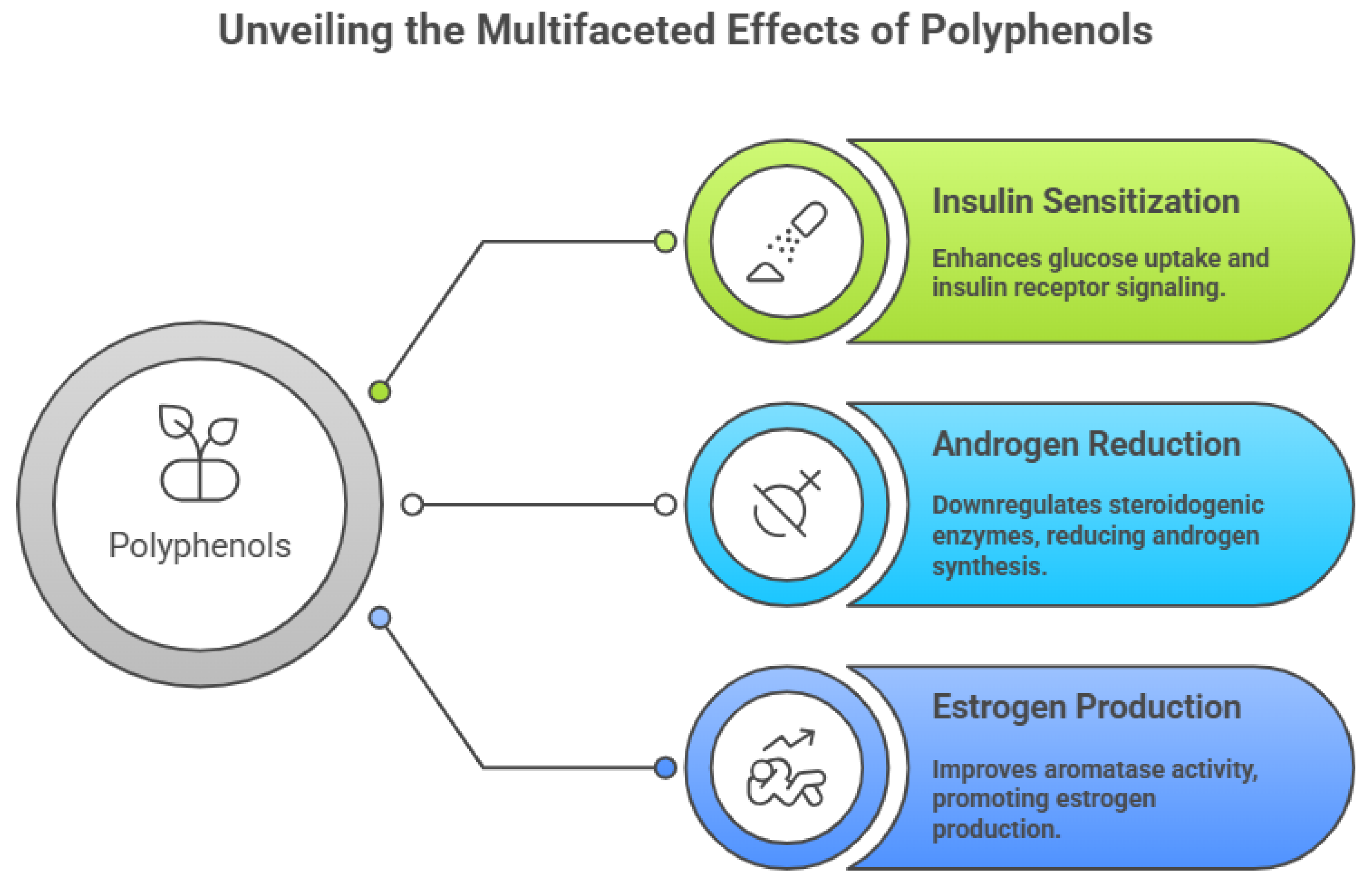

Pharmacologically, polyphenols exert significant insulin-sensitizing effects by enhancing glucose uptake, improving insulin receptor signaling, and activating AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathways. These actions help attenuate hyperinsulinemia-driven androgen excess and restore metabolic homeostasis in PCOS [

31]. Additionally, polyphenols downregulate key steroidogenic enzymes such as CYP17A1 and 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, thereby reducing ovarian androgen synthesis. By improving aromatase activity in granulosa cells, polyphenolic compounds also promote estrogen production and support normal follicular maturation and ovulatory function [

32].

Figure 2.

Multifaceted effects of Polyphenols.

Figure 2.

Multifaceted effects of Polyphenols.

Beyond metabolic and hormonal regulation, polyphenolic bioactives exhibit strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, which are crucial in mitigating ovarian oxidative stress and chronic low-grade inflammation associated with PCOS [

33]. They effectively neutralize reactive oxygen species, enhance endogenous antioxidant enzymes (superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase), and suppress pro-inflammatory signaling pathways including NF-κB, MAPKs, and cytokine release [

34]. Collectively, these pharmacological effects position polyphenolic compounds as promising multitarget agents for PCOS management. However, their clinical utility is constrained by poor solubility, low bioavailability, and rapid metabolism, thereby necessitating advanced delivery strategies such as polymeric nanoparticle-based formulations to fully harness their therapeutic potential [

35].

Mechanistic Role of Polyphenols in Modulating Insulin Resistance, Oxidative Stress, and Ovarian Steroidogenesis

Insulin resistance is a central metabolic abnormality in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), and polyphenolic compounds have demonstrated a significant capacity to restore insulin sensitivity through multiple molecular mechanisms. Polyphenols such as quercetin, resveratrol, epigallocatechin gallate, and curcumin enhance insulin receptor substrate (IRS-1/2) phosphorylation and promote downstream activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt signaling pathway, thereby facilitating glucose uptake in peripheral tissues. Additionally, activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) by polyphenols improves cellular energy homeostasis, suppresses hepatic gluconeogenesis, and reduces compensatory hyperinsulinemia [

36]. Through these coordinated actions, polyphenols indirectly attenuate insulin-driven ovarian androgen overproduction, a key pathological feature of PCOS.

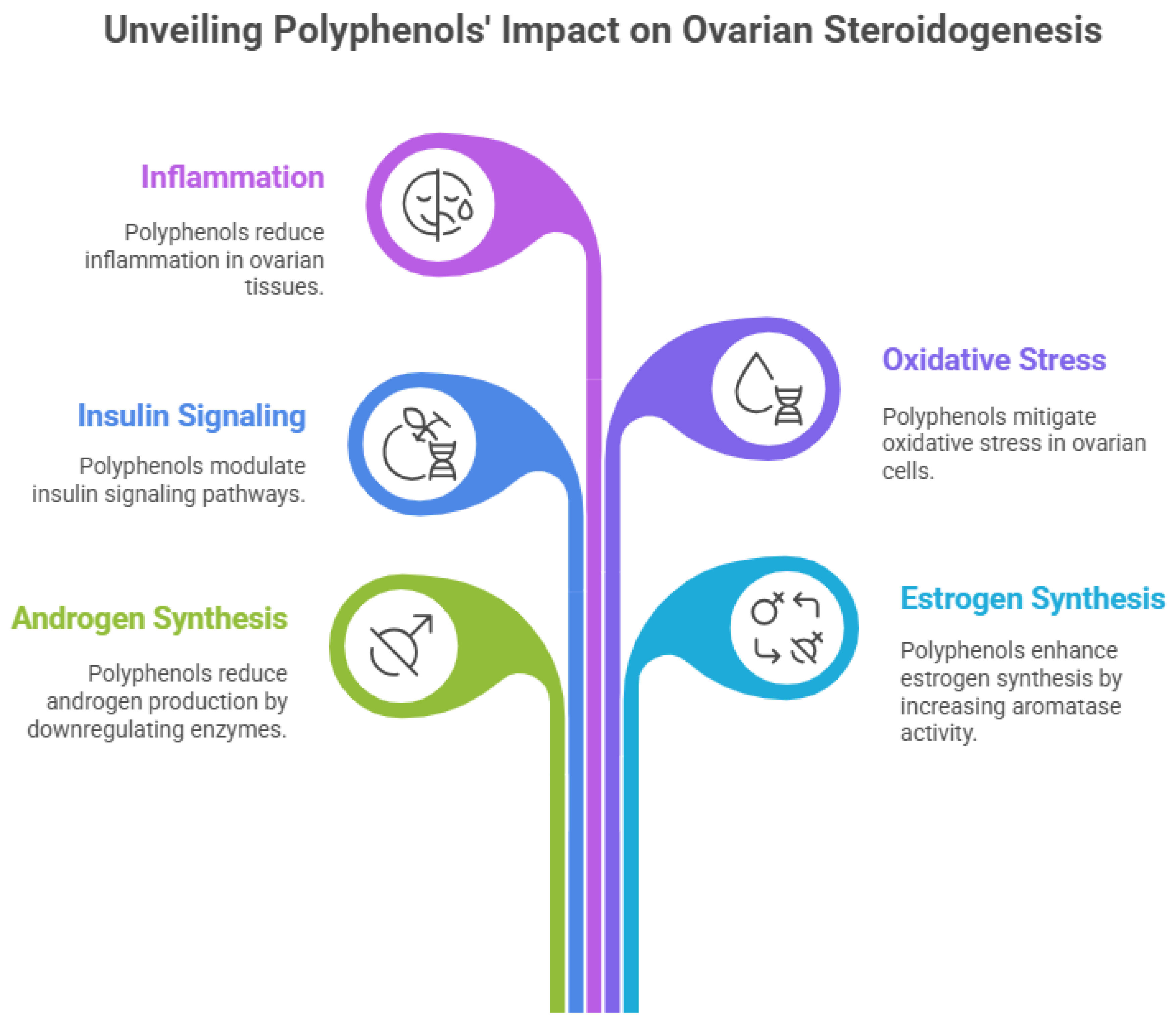

Oxidative stress plays a pivotal role in disrupting ovarian follicular development and metabolic balance in PCOS, and polyphenols act as potent modulators of redox homeostasis. These compounds directly scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS) and inhibit lipid peroxidation while simultaneously enhancing endogenous antioxidant defense systems, including superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase [

37]. Polyphenols also activate the nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathway, leading to upregulation of cytoprotective genes and improved mitochondrial function in ovarian granulosa cells. By reducing oxidative damage and mitochondrial dysfunction, polyphenols help preserve follicular integrity and support normal oocyte maturation [

38].

Chronic low-grade inflammation is closely intertwined with oxidative stress and insulin resistance in PCOS, contributing to impaired ovarian steroidogenesis. Polyphenolic compounds exert strong anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting pro-inflammatory transcription factors such as nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and activator protein-1 (AP-1), thereby reducing the expression of cytokines including TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β [

39]. Suppression of inflammatory signaling pathways mitigates insulin resistance and prevents inflammation-induced dysregulation of steroidogenic enzymes within the ovary. This anti-inflammatory action is particularly important in restoring the functional microenvironment required for normal follicular development [

39].

At the level of ovarian steroidogenesis, polyphenols directly regulate key enzymes and signaling pathways involved in androgen and estrogen synthesis. Studies have shown that polyphenolic compounds downregulate the expression and activity of steroidogenic enzymes such as CYP17A1, CYP11A1, and 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase in theca cells, leading to reduced androgen production [

40]. Concurrently, polyphenols enhance aromatase (CYP19A1) activity in granulosa cells, facilitating the conversion of androgens to estrogens and promoting follicular maturation and ovulation. By simultaneously modulating insulin signaling, oxidative stress, inflammation, and steroidogenic pathways, polyphenols offer a comprehensive, multitarget therapeutic approach for correcting the molecular and endocrine abnormalities underlying PCOS [

41].

Figure 3.

Polyphenols impacts on ovarian steroidogenisis.

Figure 3.

Polyphenols impacts on ovarian steroidogenisis.

Polymeric Nanoparticles as Advanced Drug Delivery Systems: Design, Materials, and Functional Attributes

Polymeric nanoparticles (PNPs) have emerged as highly versatile and advanced drug delivery systems capable of overcoming the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic limitations associated with conventional therapeutics. Typically ranging from 10 to 500 nm in size, these nanosystems are designed to encapsulate, adsorb, or conjugate bioactive molecules, thereby enhancing their stability, solubility, and therapeutic index. In the context of PCOS, polymeric nanoparticles offer the distinct advantage of delivering therapeutics directly to ovarian tissue, enabling sustained and localized drug release while minimizing systemic exposure and adverse effects. Their tunable physicochemical properties make them particularly suitable for addressing the multifactorial and chronic nature of PCOS [

42].

The design of polymeric nanoparticles involves careful optimization of particle size, surface charge, morphology, and drug-loading efficiency, all of which critically influence biological performance [

43]. Nanoparticles with smaller sizes exhibit improved cellular uptake and tissue penetration, while surface charge affects circulation time and interaction with biological membranes. Surface functionalization using targeting ligands such as peptides, antibodies, or polysaccharides can further enhance ovarian specificity and cellular internalization. Additionally, controlled and stimuli-responsive release mechanisms—triggered by pH, enzymes, or redox conditions—allow precise temporal and spatial drug delivery, aligning therapeutic release with disease-specific microenvironments.

Table 1.

Evidence-Based Characteristics of Polymeric Nanoparticles as Advanced Drug Delivery Systems.

Table 1.

Evidence-Based Characteristics of Polymeric Nanoparticles as Advanced Drug Delivery Systems.

| Author et al. |

Polymeric Material |

Nanoparticle Design / Size |

Functional Attribute Evaluated |

Model/System Used |

Key Evidence and Outcomes |

References |

| Makadia et al. |

PLGA |

100–250 nm, spherical |

Biodegradability, controlled release |

In-vitro & in-vivo (rodents) |

Predictable degradation, sustained drug release, FDA-accepted polymer |

[44] |

| Danhier et al. |

PLGA–PEG |

80–200 nm, PEGylated surface |

Prolonged circulation, reduced clearance |

Murine model |

PEGylation reduced opsonization and improved bioavailability |

[45] |

| Kumari et al. |

Chitosan |

50–300 nm, positively charged |

Mucoadhesion, enhanced cellular uptake |

Cell culture models |

Improved epithelial penetration and intracellular delivery |

[46] |

| Alexis et al. |

PLA / PLGA |

100–400 nm |

Size-dependent biodistribution |

In-vivo (rats) |

Smaller particles showed better tissue penetration and uptake |

[47] |

| Panyam et al. |

PLGA |

~200 nm |

Endosomal escape capability |

In-vitro (epithelial cells) |

Enhanced intracellular drug release and therapeutic efficacy |

[48] |

| Sabir et al. |

Alginate–chitosan |

150–350 nm |

pH-responsive drug release |

Simulated GI conditions |

Controlled release in acidic and neutral pH environments |

[49] |

| Torchilin et al. |

PEGylated polymeric NPs |

<200 nm |

Targeting and surface functionalization |

Cancer and endocrine models |

Ligand-modified NPs enhanced tissue specificity |

[50] |

| Zhao et al. |

Polycaprolactone (PCL) |

100–300 nm |

Long-term sustained release |

In-vivo (chronic dosing model) |

Slower degradation enabled prolonged therapeutic action |

[51] |

| Feng et al. |

PLGA nanoparticles |

120–180 nm |

Protection of labile bioactives |

Polyphenol-loaded systems |

Prevented degradation, enhanced stability of polyphenols |

[52] |

| Blanco et al. |

Multifunctional polymeric NPs |

Tunable |

Multimodal delivery |

Preclinical disease models |

Enabled combined targeting, imaging, and therapy |

[53] |

A wide range of natural and synthetic polymers are employed in nanoparticle fabrication due to their biocompatibility, biodegradability, and regulatory acceptance. Synthetic polymers such as poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), polycaprolactone (PCL), polyethylene glycol (PEG), and polylactic acid (PLA) are extensively used owing to their predictable degradation profiles and mechanical stability [

54]. Natural polymers including chitosan, alginate, gelatin, and dextran offer additional advantages such as mucoadhesiveness, inherent bioactivity, and enhanced cellular affinity. The choice of polymer significantly influences drug encapsulation efficiency, release kinetics, and in vivo behavior of the nanoparticles, allowing customization for specific therapeutic requirements in PCOS management [

55].

Functionally, polymeric nanoparticles provide multiple benefits that are particularly relevant for delivering polyphenolic bioactive compounds. They protect encapsulated polyphenols from premature degradation and metabolism, enhance oral bioavailability, and enable sustained release, thereby maintaining therapeutic concentrations over extended periods [

56]. Furthermore, nanoparticles facilitate intracellular delivery and mitochondrial targeting, amplifying the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of polyphenols at the ovarian level. These functional attributes not only improve therapeutic efficacy but also reduce dosing frequency and toxicity, positioning polymeric nanoparticles as a promising platform for next-generation, targeted nanotherapeutics in PCOS treatment [

57].

Polyphenolic Compound–Loaded Polymeric Nanoparticles for Targeted PCOS Therapy: In-Vitro and In-Vivo Evidence

In-vitro investigations provide the foundational evidence supporting the therapeutic potential of polyphenolic compound–loaded polymeric nanoparticles in PCOS management. Studies employing ovarian granulosa cells, theca cells, adipocytes, and insulin-resistant cell models have demonstrated that nanoencapsulation significantly enhances the cellular uptake and biological activity of polyphenols compared with their free forms [

58]. Nanoparticle-delivered polyphenols effectively reduce intracellular reactive oxygen species, restore mitochondrial membrane potential, and improve insulin signaling through activation of PI3K/Akt and AMPK pathways. Additionally, downregulation of inflammatory mediators and androgen-producing enzymes has been consistently observed, indicating superior cytoprotective and endocrine-modulating effects at lower concentrations than conventional formulations [

59].

Encapsulation within polymeric nanoparticles also improves the stability and sustained release of polyphenolic compounds, resulting in prolonged bioactivity in in-vitro systems. PLGA-, chitosan-, and PEG-modified nanoparticles loaded with quercetin, resveratrol, curcumin, or epigallocatechin gallate have shown enhanced antioxidant enzyme expression and reduced apoptosis in granulosa cells exposed to hyperandrogenic or oxidative stress conditions. Importantly, nanoparticle-based delivery minimizes cytotoxicity and maintains cellular viability, underscoring the safety and therapeutic precision of these nanocarriers. These findings collectively highlight the ability of polymeric nanoparticles to overcome poor solubility and rapid degradation of polyphenols in cellular environments relevant to PCOS.

Table 2.

Polyphenolic Compound–Loaded Polymeric Nanoparticles for PCOS Therapy – Preclinical Evidences.

Table 2.

Polyphenolic Compound–Loaded Polymeric Nanoparticles for PCOS Therapy – Preclinical Evidences.

| Author et al. |

Polyphenolic Compound |

Polymeric Carrier |

Study Model |

Key Outcomes |

Major Mechanism(s) |

References |

| Wang et al. |

Resveratrol |

PLGA nanoparticles |

Letrozole-induced PCOS rats |

Improved estrous cyclicity, reduced cystic follicles, decreased serum testosterone |

AMPK activation, CYP17A1 downregulation, insulin sensitization |

[60] |

| Sharma et al. |

Quercetin |

Chitosan nanoparticles |

DHEA-induced PCOS rats |

Reduced insulin resistance, normalized LH/FSH ratio |

PI3K/Akt signaling, antioxidant enzyme upregulation |

[61] |

| Liu et al. |

Curcumin |

PEG-PLGA nanoparticles |

Granulosa cell line (in-vitro) |

Reduced ROS, improved mitochondrial function |

Nrf2 activation, NF-κB inhibition |

[62] |

| Ahmed et al. |

Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) |

PLGA nanoparticles |

Letrozole-induced PCOS mice |

Decreased ovarian inflammation, restored folliculogenesis |

Anti-inflammatory cytokine suppression, AMPK signaling |

[63] |

| Patel et al. |

Rutin |

Alginate–chitosan nanoparticles |

Insulin-resistant ovarian cell model |

Enhanced glucose uptake, reduced androgen synthesis |

GLUT4 translocation, steroidogenic enzyme modulation |

[64] |

| Zhang et al. |

Gallic acid |

PLGA nanoparticles |

PCOS rat model |

Reduced oxidative stress, improved ovarian histology |

ROS scavenging, mitochondrial protection |

[65] |

| Rahman et al. |

Kaempferol |

Polycaprolactone (PCL) nanoparticles |

Granulosa cells (hyperandrogenic model) |

Increased aromatase expression, reduced apoptosis |

Estrogen synthesis restoration, anti-apoptotic signaling |

[66] |

| Singh et al. |

Resveratrol + Quercetin (co-loaded) |

PLGA nanoparticles |

DHEA-induced PCOS rats |

Superior metabolic and hormonal correction vs free drugs |

Synergistic antioxidant and insulin-sensitizing effects |

[67] |

In-vivo evidence from experimental PCOS models further substantiates the efficacy of polyphenolic nanoparticle formulations. Animal studies using letrozole- or dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA)-induced PCOS models have demonstrated that treatment with polyphenol-loaded polymeric nanoparticles significantly improves estrous cyclicity, reduces ovarian cyst formation, and normalizes follicular development [

68]. Biochemical analyses reveal marked reductions in serum androgen levels, insulin resistance indices, and inflammatory markers, alongside enhanced antioxidant status. Compared to free polyphenols, nanoformulated counterparts exhibit superior bioavailability, longer systemic circulation, and increased ovarian accumulation, translating into improved therapeutic outcomes at reduced dosages [

69].

Moreover, histopathological and molecular evaluations in in-vivo studies confirm the targeted action of polyphenolic nanoparticles at the ovarian level. Restoration of granulosa cell architecture, decreased theca cell hyperplasia, and reactivation of aromatase expression have been observed following nanoparticle treatment [

70]. Gene and protein expression analyses further reveal modulation of key steroidogenic and insulin signaling pathways, validating the multitargeted mechanism of action. Although clinical evidence remains limited, these preclinical findings strongly support the translational potential of polyphenolic compound–loaded polymeric nanoparticles as an innovative and targeted therapeutic strategy for PCOS, warranting further investigation through well-designed clinical trials [

71].

Safety, Biocompatibility, and Toxicological Considerations of Polymeric Nanocarriers in Reproductive Applications

Safety and biocompatibility are critical determinants in the successful translation of polymeric nanocarriers for reproductive and endocrine applications such as Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS). Polymeric nanoparticles are generally engineered from biodegradable and biocompatible materials that undergo controlled degradation into non-toxic byproducts, minimizing long-term tissue accumulation. Polymers such as poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), polycaprolactone (PCL), chitosan, alginate, and polyethylene glycol (PEG) have been extensively evaluated and are either FDA-approved or widely accepted for biomedical use. Their favorable safety profiles make them suitable candidates for ovarian drug delivery, where maintaining tissue integrity and reproductive function is paramount.

Table 3.

Safety, Biocompatibility, and Toxicological Evaluation of Polymeric Nanocarriers in Reproductive and Endocrine Applications.

Table 3.

Safety, Biocompatibility, and Toxicological Evaluation of Polymeric Nanocarriers in Reproductive and Endocrine Applications.

| Author et al. |

Polymeric Nanocarrier |

Loaded Compound |

Model Used |

Safety/Toxicity Endpoints Evaluated |

Key Findings |

References |

| Jain et al. |

PLGA nanoparticles |

Curcumin |

Female Wistar rats |

Body weight, organ index, ovarian histology |

No significant toxicity; preserved ovarian architecture |

[72] |

| Zhang et al. |

PEGylated PLGA nanoparticles |

Resveratrol |

Letrozole-induced PCOS rats |

Estrous cycle, fertility index, hormone levels |

Normal estrous cyclicity restored; no reproductive toxicity |

[73] |

| Sharma et al. |

Chitosan nanoparticles |

Quercetin |

Granulosa cells (in-vitro) |

Cell viability, ROS generation, apoptosis |

High biocompatibility; reduced oxidative stress |

[74] |

| Liu et al. |

PLGA nanoparticles |

EGCG |

Mouse ovarian tissue (ex-vivo) |

Mitochondrial function, inflammatory markers |

Improved mitochondrial health; no inflammatory toxicity |

[75] |

| Ahmed et al. |

Alginate–chitosan nanoparticles |

Rutin |

PCOS rat model |

Hematology, liver & kidney function tests |

No systemic toxicity; normal biochemical parameters |

[76] |

| Patel et al. |

Polycaprolactone (PCL) nanoparticles |

Gallic acid |

Zebrafish embryo model |

Embryotoxicity, hatchability, malformations |

Non-teratogenic at therapeutic doses |

[77] |

| Kim et al. |

PEG-coated polymeric nanoparticles |

Polyphenol mix |

Female mice |

Biodistribution, immune response |

Reduced immune activation; safe clearance profile |

[78] |

| Singh et al. |

PLGA nanoparticles |

Resveratrol |

Chronic dosing in rats |

Long-term toxicity, reproductive organ histology |

No accumulation or chronic reproductive toxicity |

[79] |

In-vitro toxicological assessments have demonstrated that well-designed polymeric nanoparticles exhibit minimal cytotoxicity toward ovarian granulosa cells, theca cells, and endometrial cell lines when used within therapeutic concentration ranges. Parameters such as cell viability, mitochondrial function, membrane integrity, and oxidative stress markers indicate that nanoencapsulation often reduces the intrinsic toxicity of loaded bioactive compounds by enabling controlled and sustained release. Additionally, surface modification strategies—such as PEGylation or ligand conjugation—further improve hemocompatibility and reduce non-specific cellular interactions, thereby enhancing biosafety in reproductive tissues.

In-vivo studies provide deeper insights into the systemic and reproductive safety of polymeric nanocarriers. Animal models treated with polymeric nanoparticles have shown no significant alterations in body weight, organ indices, hematological parameters, or serum biochemical markers at therapeutic doses. Importantly, histopathological evaluations of reproductive organs, including ovaries, uterus, and fallopian tubes, reveal preserved tissue architecture and normal folliculogenesis following nanoparticle administration. Reproductive toxicity studies also indicate no adverse effects on estrous cyclicity, fertility indices, or offspring viability, supporting the biocompatibility of these nanocarriers for reproductive applications.

Despite these encouraging findings, several toxicological considerations warrant careful attention prior to clinical translation. Factors such as nanoparticle size, surface charge, polymer composition, degradation rate, and route of administration can significantly influence biodistribution and long-term safety. Potential risks include nanoparticle accumulation, immune activation, and unintended endocrine interference if formulations are not optimally designed. Therefore, comprehensive toxicological evaluations—including chronic exposure studies, reproductive and developmental toxicity assays, and immunogenicity assessments—are essential. Establishing standardized safety assessment protocols will be crucial for advancing polymeric nanocarrier-based therapies as safe and effective interventions for PCOS and other reproductive disorders [

80].

Clinical Translation, Regulatory Challenges, and Future Perspectives in PCOS Nanomedicine

The clinical translation of nanomedicine-based interventions for Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) remains at an early stage, despite compelling preclinical evidence demonstrating the efficacy of polyphenolic compound–loaded polymeric nanoparticles. One of the primary translational challenges lies in bridging the gap between experimental models and the heterogeneous clinical presentation of PCOS in humans. Variability in phenotypes—such as lean versus obese PCOS, insulin-resistant versus normoinsulinemic profiles, and differing reproductive goals—necessitates personalized therapeutic strategies. Moreover, scaling up nanoparticle formulations from laboratory synthesis to Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP)-compliant production while maintaining batch-to-batch consistency, stability, and reproducibility remains a significant hurdle.

Regulatory approval of nanomedicines for reproductive disorders presents unique complexities due to the sensitive nature of endocrine and fertility-related outcomes. Regulatory agencies such as the FDA and EMA require comprehensive characterization of nanoparticle physicochemical properties, biodistribution, pharmacokinetics, and long-term safety, particularly with respect to reproductive and developmental toxicity. Unlike conventional drugs, nanomedicines often lack standardized regulatory frameworks, leading to prolonged approval timelines and increased developmental costs. Additionally, the absence of harmonized guidelines specific to ovarian-targeted nanotherapies complicates the evaluation process, underscoring the need for clear regulatory pathways tailored to reproductive nanomedicine.

From a clinical standpoint, patient acceptability, route of administration, and long-term compliance are critical considerations. Oral delivery remains the preferred route for chronic conditions such as PCOS; however, ensuring nanoparticle stability in the gastrointestinal tract and achieving sufficient ovarian bioavailability pose formulation challenges. Furthermore, ethical considerations related to fertility preservation, pregnancy outcomes, and transgenerational safety must be rigorously addressed through well-designed clinical trials. The limited availability of clinical data on nanoparticle-based therapies in PCOS highlights the urgent need for early-phase human studies to establish safety, optimal dosing, and therapeutic efficacy.

Future perspectives in PCOS nanomedicine are promising and increasingly aligned with precision and personalized medicine paradigms. Advances in ovarian-targeting ligands, stimuli-responsive polymeric systems, and multifunctional nanocarriers capable of co-delivering polyphenols with conventional drugs or nucleic acids may revolutionize PCOS management. Integration of omics technologies, artificial intelligence–guided formulation design, and patient stratification strategies could further optimize therapeutic outcomes. Collectively, continued interdisciplinary collaboration among nanotechnologists, endocrinologists, pharmacologists, and regulatory bodies will be essential to translate polyphenolic nanoparticle-based therapies from bench to bedside, offering safer, more effective, and targeted treatment options for women with PCOS.

Conclusion

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) is a multifactorial endocrine and metabolic disorder with complex pathophysiology involving insulin resistance, oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, and dysregulated ovarian steroidogenesis. Conventional pharmacological therapies predominantly offer symptomatic relief and are often limited by variable efficacy, systemic side effects, and poor long-term compliance. These limitations underscore the need for innovative, mechanism-based therapeutic strategies that can address the underlying molecular abnormalities of PCOS in a safe and sustained manner.

Polyphenolic bioactive compounds have emerged as promising multitarget agents due to their insulin-sensitizing, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and endocrine-modulating properties. However, their clinical application is hindered by poor solubility, low bioavailability, and rapid metabolic degradation. Polymeric nanoparticle–based delivery systems effectively overcome these barriers by enhancing stability, bioavailability, and targeted ovarian delivery, while enabling controlled and sustained release of polyphenols. Preclinical in-vitro and in-vivo studies consistently demonstrate superior therapeutic outcomes of nanoformulated polyphenols compared to their free counterparts, including improved hormonal balance, follicular development, and metabolic regulation.

Safety and biocompatibility evaluations indicate that well-designed polymeric nanocarriers, particularly those composed of biodegradable and FDA-approved polymers, exhibit minimal reproductive toxicity and favorable tolerability profiles. Nonetheless, comprehensive long-term toxicological studies and standardized regulatory frameworks are essential to ensure safe clinical translation. Addressing challenges related to large-scale manufacturing, regulatory approval, and clinical heterogeneity of PCOS remains critical for advancing these nanotherapeutic platforms.

In conclusion, polyphenolic compound–loaded polymeric nanoparticles represent a promising and transformative approach for targeted PCOS therapy. By integrating nanotechnology with reproductive endocrinology, this strategy holds the potential to shift PCOS management from symptomatic control toward precision, disease-modifying treatment. Continued interdisciplinary research, robust clinical trials, and regulatory harmonization will be pivotal in translating this emerging nanomedicine paradigm into effective clinical solutions for women affected by PCOS.

Authors Contributions

E.S.S and S.B: organised the concept, carried out the writing, and composed the report. Writing, editing, and reviewing for S.B and E.S.S Each author has reviewed and approved the final draft.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declarations.

References

- Sharma, Y. Sarwal; Devi, N. K.; Saraswathy, K. N. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome prevalence and associated sociodemographic risk factors: a study among young adults in Delhi NCR, India. Reprod. Health 2025, vol. 22(no. 1), 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Xie, Y.; Liu, Y.; Long, S.; Mo, Z. Polycystic ovarian syndrome: Correlation between hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance and obesity. Clin. Chim. Acta 2020, vol. 502, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azziz, R. , Polycystic ovary syndrome. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 2016, vol. 2(no. 1), 16057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, K.-J.; Chen, J.-H.; Chen, K.-H. The Pathophysiological Mechanism and Clinical Treatment of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Molecular and Cellular Review of the Literature. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, vol. 25(no. 16), 9037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, E. J.; Templeman, N. M. Reappraising the relationship between hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance in PCOS. J. Endocrinol. 2025, vol. 265(no. 2), e240269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moka, M. K.; Sriram, D. K.; George, M. Recent Advances in Individualized Clinical Strategies for Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Evidence From Clinical Trials and Emerging Pharmacotherapies. Clin. Ther. 2025, vol. 47(no. 2), 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, K. , Promising drugs for PCOS: targeting metabolic and endocrine dysfunctions. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2025, vol. 21(no. 8), 455–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolat, E. , Polyphenols: Secondary Metabolites with a Biological Impression. Nutrients 2024, vol. 16(no. 15), 2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Tsao, R. Dietary polyphenols, oxidative stress and antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2016, vol. 8, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenxi, Z.; Hemmat, A.; Thi, N.; Afrand, M. Nanoparticle-enhanced drug delivery systems: An up-to-date review. J. Mol. Liq. 2025, vol. 424, 126999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kučuk, N.; Primožič, M.; Knez, Ž.; Leitgeb, M. Sustainable Biodegradable Biopolymer-Based Nanoparticles for Healthcare Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, vol. 24(no. 4), 3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senthilkumar, H.; Chauhan, S. C.; Arumugam, M. Unraveling the multifactorial pathophysiology of polycystic ovary syndrome: exploring lifestyle, prenatal influences, neuroendocrine dysfunction, and post-translational modifications. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2025, vol. 52(no. 1), 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrasekaran, P.; Weiskirchen, R. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Insulin Resistance. Curr. Tissue Microenviron. Rep. 2024, vol. 5(no. 3), 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, I. R.; McKinley, M. C.; Bell, P. M.; Hunter, S. J. Sex hormone binding globulin and insulin resistance. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf.) 2013, vol. 78(no. 3), 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, A.; Bruno, C.; Vergani, E.; d’Abate, C.; Giacchi, E.; Silvestrini, A. Oxidative Stress and Low-Grade Inflammation in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Controversies and New Insights. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, vol. 22(no. 4), 1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; et al. miR-484 mediates oxidative stress-induced ovarian dysfunction and promotes granulosa cell apoptosis via SESN2 downregulation. Redox Biol. 2023, vol. 62, 102684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharani, V.; Nishu, S.; Hariprasath, L. PCOS and genetics: Exploring the heterogeneous role of potential genes in ovarian dysfunction, a hallmark of PCOS – A review. Reprod. Biol. 2025, vol. 25(no. 2), 101017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsetti, A.; Illi, B.; Gaetano, C. How epigenetics impacts on human diseases. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2023, vol. 114, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ee, C.; Tay, C. T. Pharmacological management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Aust. Prescr. 2024, vol. 47(no. 4), 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forslund, M.; et al. Different kinds of oral contraceptive pills in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2023, vol. 189(no. 1), S1–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguz, S. H.; Yildiz, B. O. An Update on Contraception in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Endocrinol. Metab. Seoul Korea 2021, vol. 36(no. 2), 296–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusan, L.; Dupont, A.; Gomez, J.-L.; Tremblay, R. R.; Labrie, F. Comparison of flutamide and spironolactone in the treatment of hirsutism: a randomized controlled trial. Fertil. Steril. 1994, vol. 61(no. 2), 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Xing, C.; Zhang, J.; He, B. Comparative efficacy of oral insulin sensitizers metformin, thiazolidinediones, inositol, and berberine in improving endocrine and metabolic profiles in women with PCOS: a network meta-analysis. Reprod. Health 2021, vol. 18(no. 1), 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chera-Aree, P.; Tanpong, S.; Thanaboonyawat, I.; Laokirkkiat, P. Clomiphene citrate plus letrozole versus clomiphene citrate alone for ovulation induction in infertile women with ovulatory dysfunction: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Womens Health 2023, vol. 23(no. 1), 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imtiaz, S. Mechanistic study of cancer drug delivery: Current techniques, limitations, and future prospects. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2025, vol. 290, 117535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Tanani, M.; et al. Revolutionizing Drug Delivery: The Impact of Advanced Materials Science and Technology on Precision Medicine. Pharmaceutics 2025, vol. 17(no. 3), 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagoskina, N.V.; et al. Polyphenols in Plants: Structure, Biosynthesis, Abiotic Stress Regulation, and Practical Applications (Review). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, vol. 24(no. 18), 13874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciupei, D.; Colişar, A.; Leopold, L.; Stănilă, A.; Diaconeasa, Z. M. Polyphenols: From Classification to Therapeutic Potential and Bioavailability. Foods 2024, vol. 13(no. 24), 4131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subhan, S.; Zeeshan, M.; Rahman, A. Ur.; Yaseen, M. Fundamentals of Polyphenols : Nomenclature, Classification and Properties. In Science and Engineering of Polyphenols, 1st ed.; Verma, C., Ed.; Wiley, 2024; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, K. B.; Rizvi, S. I. Plant polyphenols as dietary antioxidants in human health and disease. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2009, vol. 2(no. 5), 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, B. G.; Faculty of Pharmacy Kampala International University Uganda. Polyphenols and Insulin Sensitivity: A Pathophysiological Perspective. Res. Output J. Public Health Med. 2025, vol. 5(no. 3), 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L. J.; Touaibia, M. Prevention of Male Late-Onset Hypogonadism by Natural Polyphenolic Antioxidants. Nutrients 2024, vol. 16(no. 12), 1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Liu, Z.; Lin, M.; Gao, N.; Wang, X. Polyphenols in health and food processing: antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant insights. Front. Nutr. 2024, vol. 11, 1456730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandimali, N.; et al. Free radicals and their impact on health and antioxidant defenses: a review. Cell Death Discov. 2025, vol. 11(no. 1), 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhan, M.; Aatif, M. Potential Health Benefits of Polyphenols and Their Nanoformulations in Humans. In Breaking Boundaries: Pioneering Sustainable Solutions Through Materials and Technology; Alam, M. W., Ed.; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2025; pp. 367–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahwan, M.; Alhumaydhi, F.; Ashraf, G., Md; Hasan, P. M. Z.; Shamsi, A. Role of polyphenols in combating Type 2 Diabetes and insulin resistance. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, vol. 206, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.-Q.; et al. Premature ovarian insufficiency: a review on the role of oxidative stress and the application of antioxidants. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, vol. 14, 1172481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, R.; Mohammadpour, A.; Medoro, A.; Davinelli, S.; Saso, L.; Miroliaei, M. Exploring the links between polyphenols, Nrf2, and diabetes: A review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2025, vol. 186, 118020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Chen, Y.; Xing, J.; Zhang, N.; Xu, L. Systematic low-grade chronic inflammation and intrinsic mechanisms in polycystic ovary syndrome. Front. Immunol. 2024, vol. 15, 1470283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Andersen, C. Y.; Rasmussen, F. R.; Cadenas, J.; Christensen, S. T.; Mamsen, L. S. Expression of genes and enzymes involved in ovarian steroidogenesis in relation to human follicular development. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, vol. 14, 1268248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashemain, Z.; et al. CYP19A1 Promoters Activity in Human Granulosa Cells: A Comparison between PCOS and Normal Subjects. Cell J. 2022, vol. 24(no. 4), 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesgin, R. M.; Nejati, V.; Talatapeh, S. P.; Imani, Z.; Rezaie, J. Nanoparticles for Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) Therapy: Exosomes and Synthetic Nanoparticles, Challenges and Opportunities. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2025, vol. 43(no. 9), e70114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Cruz, J. J.; Chapa-Villarreal, F. A.; Duggal, I.; Peppas, N. A. Advanced rational design of polymeric nanoparticles for the controlled delivery of biologics. J. Controlled Release 2025, vol. 384, 113940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Liu, J.; Tan, S.; Liu, W.; Wang, R.; Chen, C. PLGA sustained-release microspheres loaded with an insoluble small-molecule drug: microfluidic-based preparation, optimization, characterization, and evaluation in vitro and in vivo. Drug Deliv. 2022, vol. 29(no. 1), 1437–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesharwani, P.; et al. PEGylated PLGA nanoparticles: unlocking advanced strategies for cancer therapy. Mol. Cancer 2025, vol. 24(no. 1), 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harugade, A.; Sherje, A. P.; Pethe, A. Chitosan: A review on properties, biological activities and recent progress in biomedical applications. React. Funct. Polym. 2023, vol. 191, 105634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattel, P.; Sulthana, S.; Trousil, J.; Shrestha, D.; Pearson, D.; Aryal, S. Effect of Nanoparticle Weight on the Cellular Uptake and Drug Delivery Potential of PLGA Nanoparticles. ACS Omega 2023, vol. 8(no. 30), 27146–27155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panyam, J.; Zhou, W.-Z.; Prabha, S.; Sahoo, S. K.; Labhasetwar, V. Rapid endo-lysosomal escape of poly(DL-lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles: implications for drug and gene delivery. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2002, vol. 16(no. 10), 1217–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeller, J.; et al. pH-Responsive Chitosan/Alginate Polyelectrolyte Complexes on Electrospun PLGA Nanofibers for Controlled Drug Release. Nanomater. Basel Switz. 2021, vol. 11(no. 7), 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottonelli, I.; Baraldi, C.; Ruozi, B.; Vandelli, M. A.; Tosi, G.; Duskey, J. T. Advantages and challenges of polymer-lipid hybrid nanoparticles for the delivery of biotech drugs. Nanomed. 2025, vol. 20(no. 7), 641–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntrivala, M.A.; et al. Polycaprolactone (PCL): the biodegradable polyester shaping the future of materials – a review on synthesis, properties, biodegradation, applications and future perspectives. Eur. Polym. J. 2025, vol. 234, 114033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; et al. Drug-loaded PEG-PLGA nanoparticles for cancer treatment. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, vol. 13, 990505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. , “Multifunctional nanoparticle-mediated combining therapy for human diseases,” Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, vol. 9(no. 1, p. 1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, H.; Jangde, R. K. Current updated review on preparation of polymeric nanoparticles for drug delivery and biomedical applications. Nanotechnol. 2023, vol. 2, 100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satchanska, G.; Davidova, S.; Petrov, P. D. Natural and Synthetic Polymers for Biomedical and Environmental Applications. Polymers 2024, vol. 16(no. 8), 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, S.; Ramalho, M. J.; Loureiro, J. A. Polymeric Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications. Polymers 2024, vol. 16(no. 2), 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabish, T. A.; Hamblin, M. R. Mitochondria-targeted nanoparticles (mitoNANO): An emerging therapeutic shortcut for cancer. Biomater. Biosyst. 2021, vol. 3, 100023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LIczbiński, P.; Bukowska, B. Tea and coffee polyphenols and their biological properties based on the latest in vitro investigations. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, vol. 175, 114265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y. , Polyphenol-Based Nanoparticles for Intracellular Protein Delivery via Competing Supramolecular Interactions. ACS Nano 2020, vol. 14(no. 10), 12972–12981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, E. M.; Abd El-moneam, S. M.; Yousof, S. M.; Mohammed, S. A.; Sultan, B. O.; Mansour, B. S. A. Resveratrol protects against letrozole-induced renal damage in a rat model of polycystic ovary syndrome: A biochemical, histological, and immunohistochemical study. Tissue Cell 2025, vol. 95, 102934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari-Khorchani, M.; Neisy, A.; Alaee, S.; Zare-Mehrjardi, M. J.; Zal, F. Quercetin modulates the interplay between DNMT gene expression, oxidative stress, and trace elements in DHEA-induced polycystic ovary syndrome rat model. Sci. Rep. 2025, vol. 15(no. 1), 34770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S. , Curcumin-loaded PLGA-PEG nanoparticles conjugated with B6 peptide for potential use in Alzheimer’s disease. Drug Deliv. 2018, vol. 25(no. 1), 1091–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capasso, L. , Epigallocatechin Gallate (EGCG): Pharmacological Properties, Biological Activities and Therapeutic Potential. Mol. Basel Switz. 2025, vol. 30(no. 3), 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surendran, V.; Palei, N. N. Formulation and Characterization of Rutin Loaded Chitosan-alginate Nanoparticles: Antidiabetic and Cytotoxicity Studies. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2022, vol. 19(no. 3), 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazloom, F.; Edalatmanesh, M. A.; Hosseini, S. E. Gallic acid reduces inflammatory cytokines and markers of oxidative damage in a rat model of estradiol-induced polycystic ovary. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 2019, vol. 28(no. 5), 1281–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, S.; Scheper, T.; Walter, J.-G. Production of polycaprolactone nanoparticles with hydrodynamic diameters below 100 nm. Eng. Life Sci. 2019, vol. 19(no. 10), 658–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polati; Neerati, P. Enhancing the anti-cancer potential of resveratrol through cocrystal technology in colorectal cancerous rats. Sci. Rep. 2025, vol. 15(no. 1), 44606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhakaran, G.; Babu, S. R.; Mahendra, H.; Arockiaraj, J. Updated experimental cellular models to study polycystic ovarian syndrome. Life Sci. 2023, vol. 322, 121672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijboer, A. C.; Hannema, S. E. Androgen Excess and Deficiency: Analytical and Diagnostic Approaches. Clin. Chem. 2023, vol. 69(no. 12), 1361–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielson, K.; et al. In Vivo Imaging With Confirmation by Histopathology for Increased Rigor and Reproducibility in Translational Research: A Review of Examples, Options, and Resources. ILAR J. 2018, vol. 59(no. 1), 80–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, J.J. (Ed.) Molecular Mechanisms of Steroid Hormone Biosynthesis and Action; MDPI, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orunoğlu, M.; et al. , Effects of curcumin-loaded PLGA nanoparticles on the RG2 rat glioma model. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, vol. 78, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomar, S.; et al. Targeted delivery of resveratrol using PEGylated PLGA nanoparticles decorated with folic acid for cancer therapy: characterization, and in vitro studies. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2025, vol. 51(no. 12), 1763–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardim, K. V.; Siqueira, J. L. N.; Báo, S. N.; Parize, A. L. In vitro cytotoxic and antioxidant evaluation of quercetin loaded in ionic cross-linked chitosan nanoparticles. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, vol. 74, 103561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetto, G.; et al. Aptamer-Coated PLGA Nanoparticles Selectively Internalize into Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Cells In Vitro and In Vivo. Biomolecules 2025, vol. 15(no. 8), 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surendran, V.; Palei, N. N. Formulation and Characterization of Rutin Loaded Chitosan-alginate Nanoparticles: Antidiabetic and Cytotoxicity Studies. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2022, vol. 19(no. 3), 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, A.; Sárria, M. P.; Pinto, I.; Espiña, B.; Gomes, A. C.; Dias, A. C. P. Protection against Paraquat-Induced Oxidative Stress by Curcuma longa Extract-Loaded Polymeric Nanoparticles in Zebrafish Embryos. Polymers 2022, vol. 14(no. 18), 3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suk, J. S.; Xu, Q.; Kim, N.; Hanes, J.; Ensign, L. M. PEGylation as a strategy for improving nanoparticle-based drug and gene delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, vol. 99, no. Pt A, 28–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Pan, Q.; Teng, J.; Zhang, H.; Qin, N. Intra-articular administration of PLGA resveratrol sustained-release nanoparticles attenuates the development of rat osteoarthritis. Mater. Today Bio 2024, vol. 24, 100884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đorđević, S.; et al. Current hurdles to the translation of nanomedicines from bench to the clinic. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2022, vol. 12(no. 3), 500–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).