Submitted:

24 December 2025

Posted:

26 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Statement

2.2. Study Site

2.3. Experimental Design

2.4. Data Processing

2.4.1. Mortality

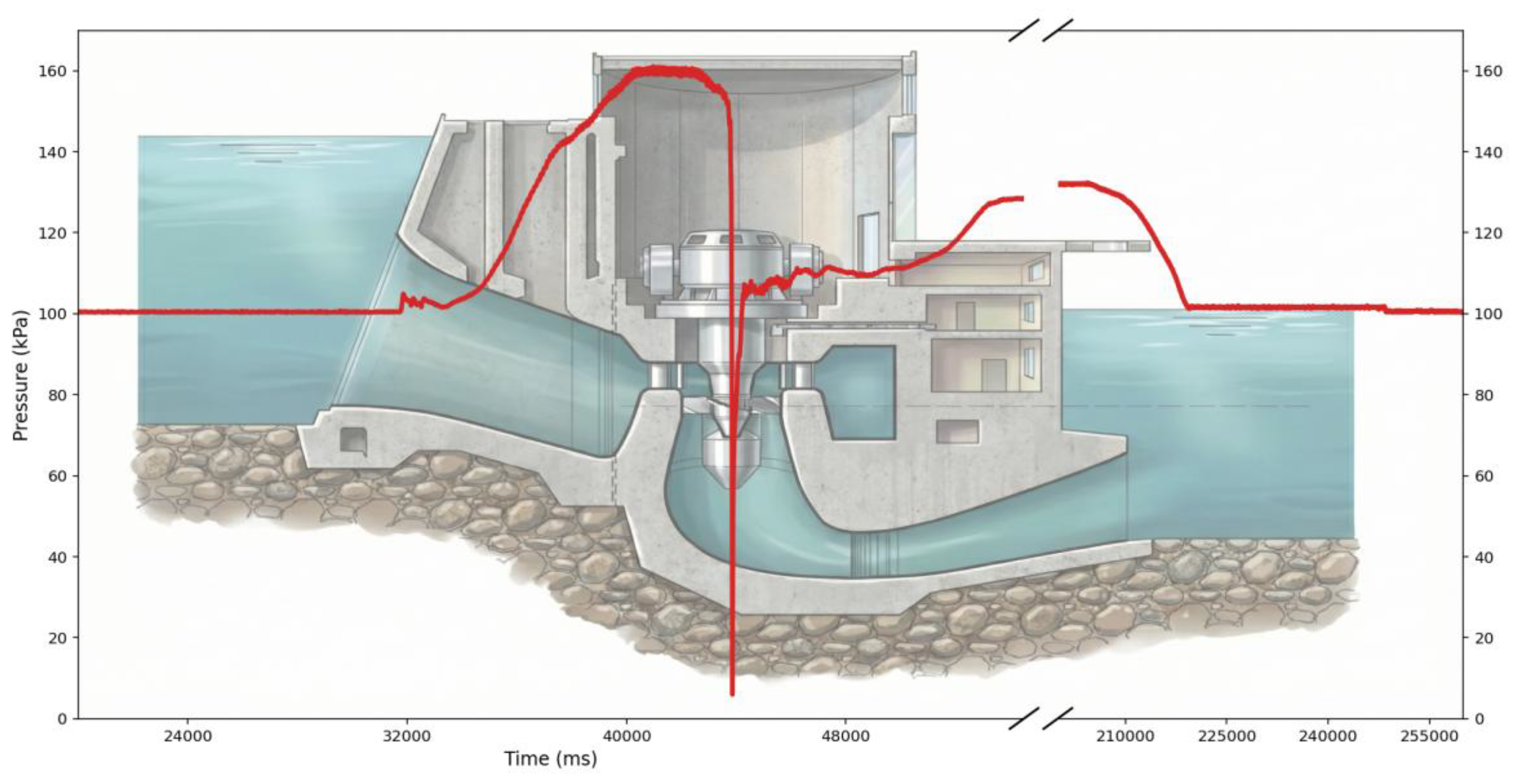

2.4.2. Pressure Profile

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

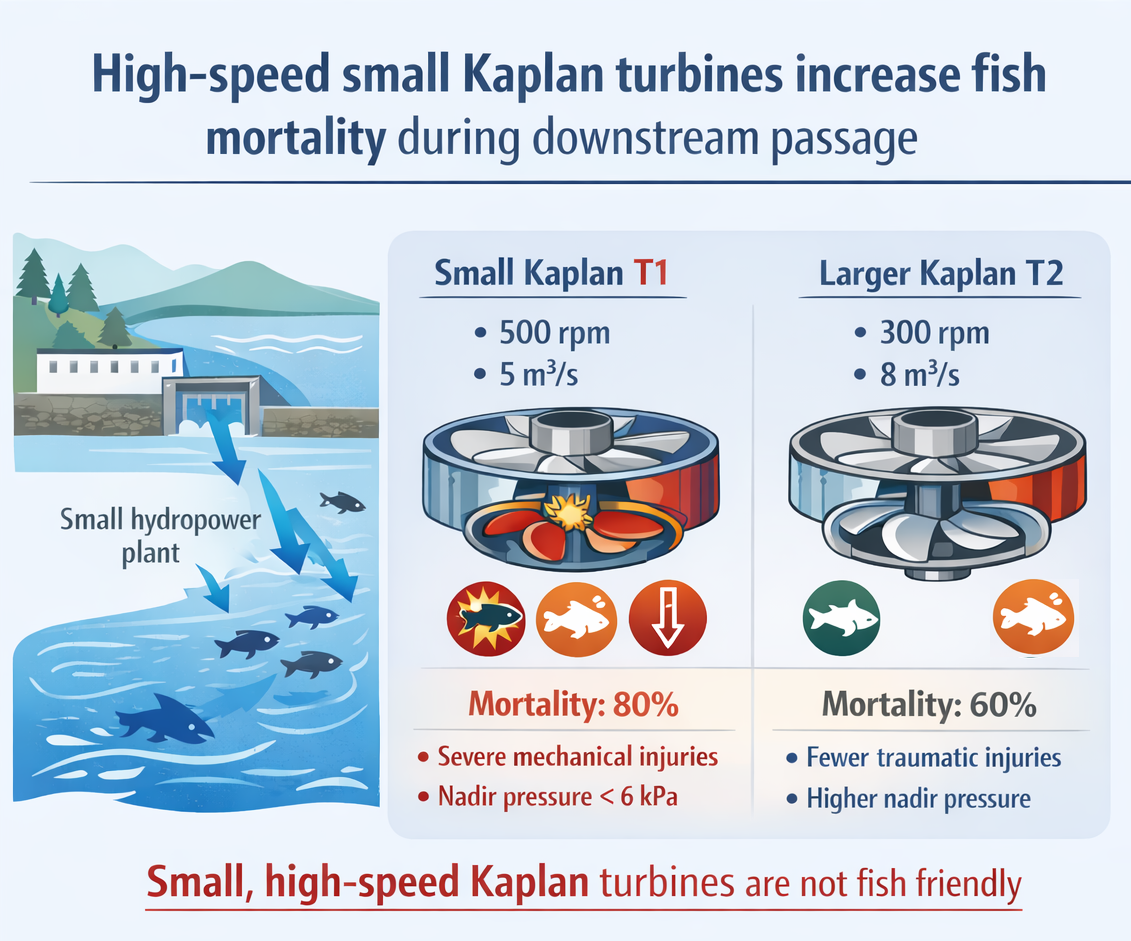

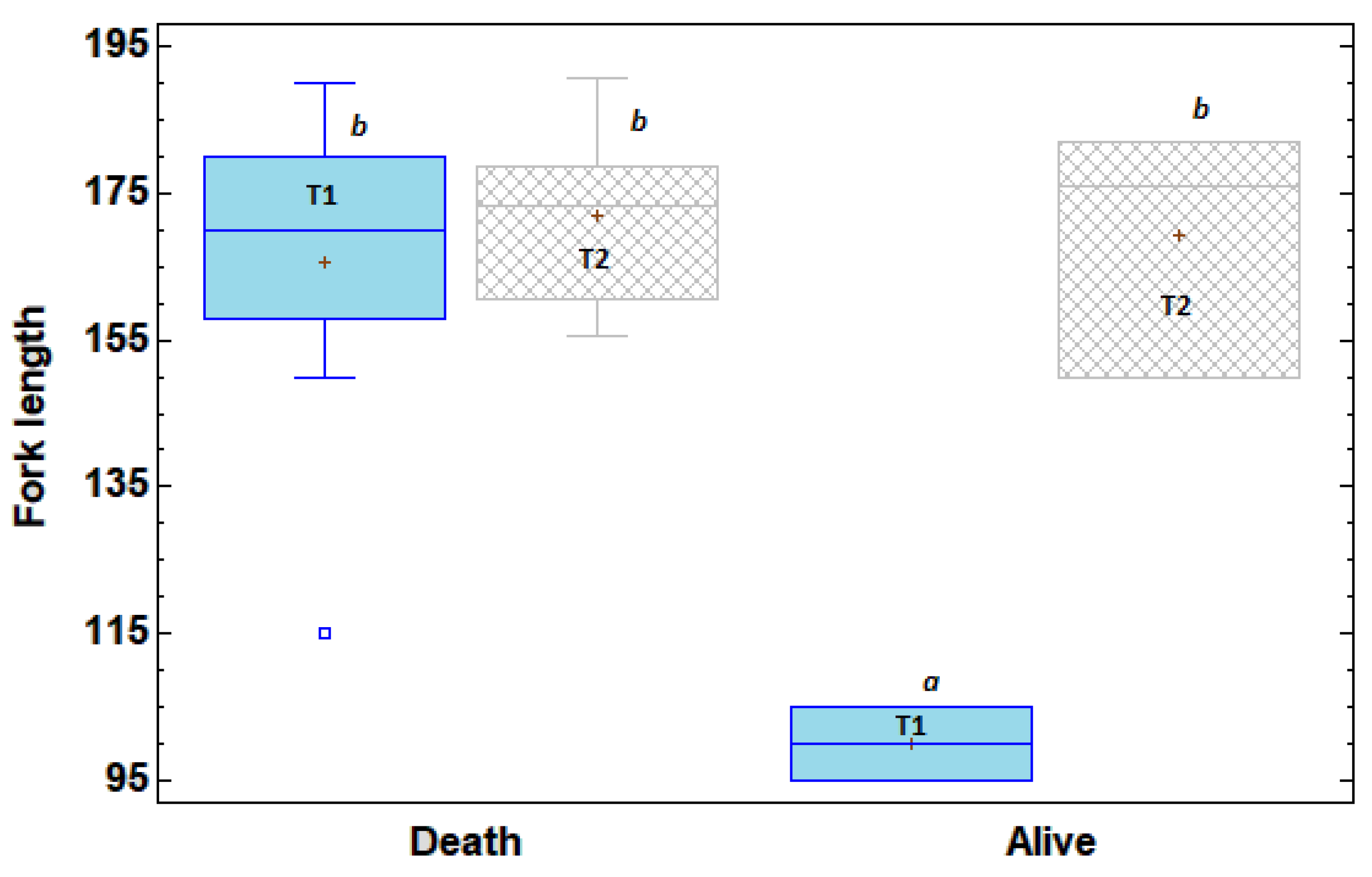

3.1. Mortality

a) Experimental mortality (Me)

b) Mortality (M)

3.2. Pressure Profile

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Management Applications

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Celestino, L.F.; Sanz-Ronda, F.J.; Miranda, L.E.; Makrakis, M.C.; Dias, J.H.P.; Makrakis, S. Bidirectional connectivity via fish ladders in a large Neotropical river. River Res. Appl. 2019, 35, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes Celestino, L.; Sanz-Ronda, F.J.; Miranda, L.E.; Cavicchioli Makrakis, M.; Dias, J.H.P.; Makrakis, S. Bidirectional connectivity via fish ladders in a large Neotropical river: Response to a comment. River Res. Appl. 2020, 36, 1377–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, M.C.; Baras, E.; Thom, T.J.; Duncan, A.; Slavík, O. Migration of freshwater fishes; Wiley Online Library: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

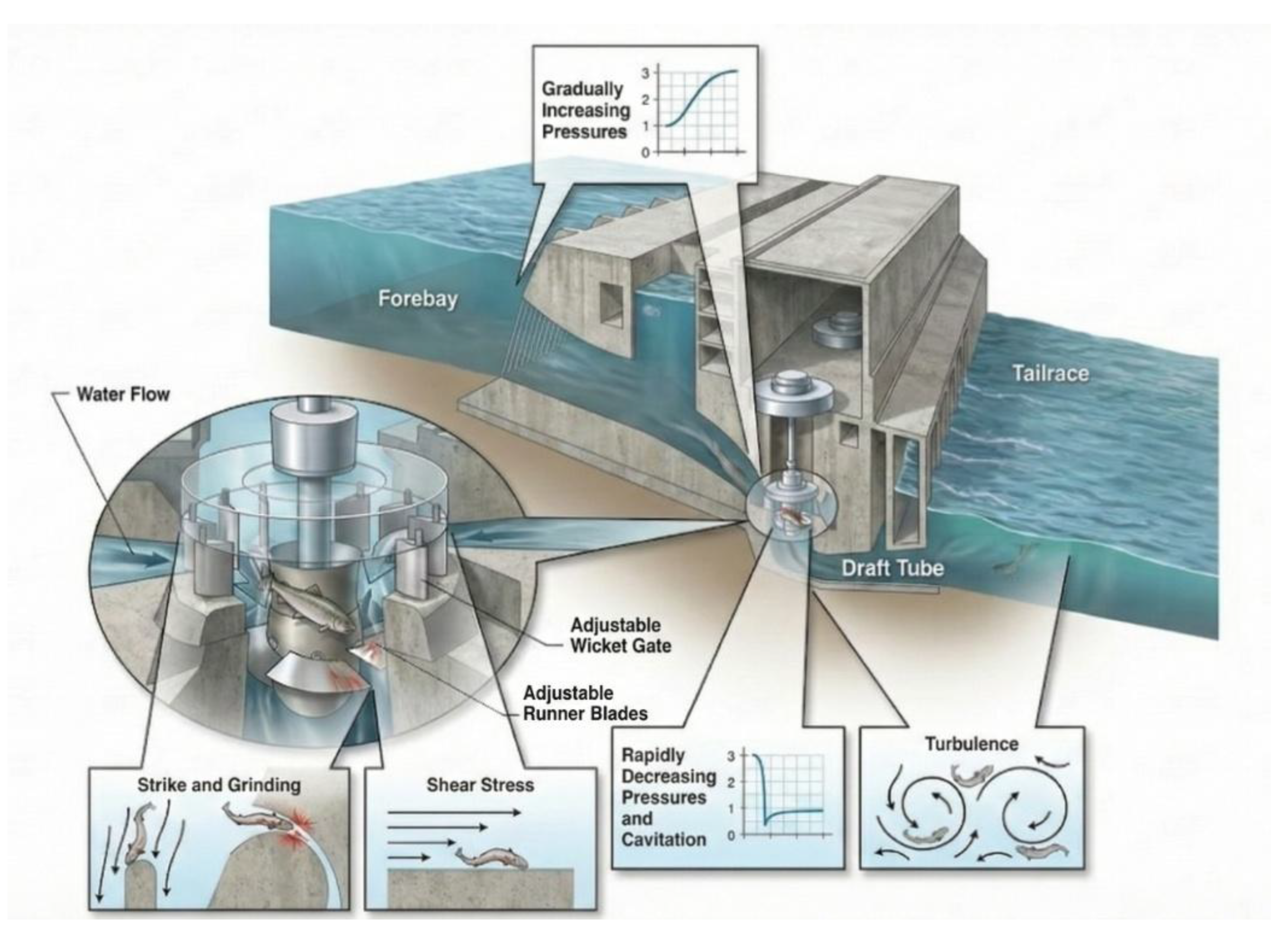

- Pracheil, B.M.; DeRolph, C.R.; Schramm, M.P.; Bevelhimer, M.S. A fish-eye view of riverine hydropower systems: the current understanding of the biological response to turbine passage. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2016 262 2016, 26, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Ronda, F.J.; Fuentes-Pérez, J.F.; García-Vega, A.; Bravo-Córdoba, F.J. Fishways as Downstream Routes in Small Hydropower Plants: Experiences with a Potamodromous Cyprinid. Water 2021, 13, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwevers, U.; Adam, B. Fish protection technologies and fish ways for downstream migration; Springer, 2020; Vol. 279. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, M.; Knott, J.; Pander, J.; Geist, J. Experimental comparison of fish mortality and injuries at innovative and conventional small hydropower plants. J. Appl. Ecol 2022, 59, 2360–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarestrup, K.; Jepsen, N.; Rasmussen, G.; Okland, F. Movements of two strains of radio tagged Altlantic salmon, Salmo salar L., smolts through a reservoir. Fish. Manag. Ecol. 1999, 6, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepsen, N.; Aarestrup, K.; Økland, F.; Rasmussen, G. Survival of radiotagged Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.)–and trout (Salmo trutta L.) smolts passing a reservoir during seaward migration. Hydrobiologia 1998, 371, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karppinen, P.; Hynninen, M.; Vehanen, T.; Vähä, J. Variations in migration behaviour and mortality of Atlantic salmon smolts in four different hydroelectric facilities. Fish. Manag. Ecol. 2021, 28, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cada, G.F.; Coutant, C.C.; Whitney, R.R. Development of biological criteria for the design of advanced hydropower turbines; EERE Publication and Product Library: Washington, DC (United States), 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R.S.; Pflugrath, B.D.; Colotelo, A.H.; Brauner, C.J.; Carlson, T.J.; Deng, Z.D.; Seaburg, A.G. Pathways of barotrauma in juvenile salmonids exposed to simulated hydroturbine passage: Boyle’s law vs. Henry’s law. Fish. Res. 2012, 121, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Zhang, F.; Shi, X.; Adu-Poku, K.A.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, S. A systematic investigation on the damage characteristics of fish in axial flow pumps. Processes 2022, 10, 2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neitzel, D.A.; Dauble, D.D.; Čada, G.F.; Richmond, M.C.; Guensch, G.R.; Mueller, R.P.; Abernethy, C.S.; Amidan, B. Survival estimates for juvenile fish subjected to a laboratory-generated shear environment. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 2004, 133, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pflugrath, B.D.; Harnish, R.A.; Rhode, B.; Engbrecht, K.; Beirao, B.; Mueller, R.P.; McCann, E.L.; Stephenson, J.R.; Colotelo, A.H. The susceptibility of Juvenile American shad to rapid decompression and fluid shear exposure associated with simulated hydroturbine passage. Water 2020, 12, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radinger, J.; van Treeck, R.; Wolter, C. Evident but context-dependent mortality of fish passing hydroelectric turbines. Conserv. Biol. 2022, 36, e13870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Algera, D.A.; Rytwinski, T.; Taylor, J.J.; Bennett, J.R.; Smokorowski, K.E.; Harrison, P.M.; Clarke, K.D.; Enders, E.C.; Power, M.; Bevelhimer, M.S. What are the relative risks of mortality and injury for fish during downstream passage at hydroelectric dams in temperate regions? A systematic review. Environ. Evid. 2020, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čada, G.F. The development of advanced hydroelectric turbines to improve fish passage survival. Fisheries 2001, 26, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincer, I.; Ishaq, H. Renewable Hydrogen Production; Elsevier, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, I.; Hendricks, D.; Jawaid, T.S.; Rutz, D.; Steller, J. Small Hydropower Technologies—European State-of-the-Art Innovations; WIP Renewable Energies: Munich, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Halder, P.; Doppalapudi, A.T.; Azad, A.K.; Khan, M.M.K. Chapter 7 - Efficient hydroenergy conversion technologies, challenges, and policy implication. In; Azad, A.K.B.T.-A. in C.E.T., Ed.; Academic Press, 2021; pp. 295–318. ISBN 978-0-12-821221-9. [Google Scholar]

- CHD Consultoría y asistencia para la inspección y vigilancia del cumplimiento del condicionado de las concesiones de aprovechamientos hidroeléctricos en la Confederación Hidrográfica del Duero. Clave: 02.803.267/0811. In forme técnico; Confederación Hidrográfica del Duero.: Valladolid, Spain, 2011.

- Checa-Díaz, J.M. Consulting Engineer in HGM. Personal Comunication, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Sale, M.J.; Cada, G.F.; Carlson, T.J.; Dauble, D.D.; Hunt, R.T.; Sommers, G.L. DOE Hydropower Program Annual Report for FY 2002 (DOE ID-11107); U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Wind and Hydropower Technologies, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Z.; Carlson, T.J.; Ploskey, G.R.; Richmond, M.C.; Dauble, D.D. Evaluation of blade-strike models for estimating the biological performance of Kaplan turbines. Ecol. Modell. 2007, 208, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Raben, K. Regarding the problem of mutilations of fishes by hydraulic turbines. Die Wasserwirtschaft 1957, 4, 97–100. [Google Scholar]

- Montén, E. Fish and turbines: fish injuries during passage through power station turbines; Norstedts Tryckeri: Stockholm, Sweden, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bosc, S.; Larinier, M. Définition d’une statégie de réouverture de la Garonne et de l’Ariège à la dévalaison des salmonidés grands migrateurs: simulation des mortalités induites par les aménagements hydroélectriques lors de la migration de dévalaison; Irstea: Toulouse,France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Larinier, M.; Dartiguelongue, J. La circulation des poissons migrateurs: le transit à travers les turbines des installations hydroélectriques. Bull. Français la Pêche la Piscic. 1989, 1–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutschmann, P.; Kampa, E.; Wolter, C.; Albayrak, I.; David, L.; Stoltz, U.; Schletterer, M. Novel Developments for Sustainable Hydropower; Springer Nature, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, W.M.S.; Burch, R.L. The principles of humane experimental technique.; Universities Federation For Animal Welfare (UFAW): Wheathampstead, UK, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- MAPAMA Anuario de aforos 2019-2020. Estación 1106 río Bidasoa en Endarlatza; Ministerio de Agricultura y Pesca Alimentación y Medio Ambiente: Madrid, Spain, 2023.

- Horreo, J.L.; Machado-Schiaffino, G.; Griffiths, A.M.; Bright, D.; Stevens, J.R.; Garcia-Vazquez, E. Atlantic salmon at risk: apparent rapid declines in effective population size in southern European populations. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 2011, 140, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicola, G.G.; Elvira, B.; Jonsson, B.; Ayllón, D.; Almodóvar, A. Local and global climatic drivers of Atlantic salmon decline in southern Europe. Fish. Res. 2018, 198, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Vega, A.; Fuentes-Pérez, J.F.; Bravo-Córdoba, F.J.; Elso, J.; Ardaiz-Ganuza, J.; Sanz-Ronda, F.J. Assessing Trends and Challenges: Insights From 30 Years of Monitoring and Management of Threatened Southern Atlantic Salmon Populations. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2025, 35, e70052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Ronda, F.J.; Manzano, S.; Bravo-Córdoba, F.J.; Fuentes-Pérez, J.F.; García-Vega, A.; Valbuena-Castro, J. Evaluación de la mortalidad de la fauna piscícola asociada al descenso por turbinas en centrales hidroeléctricas del río Bidasoa. Resultados preliminares. Technical report, Project LIFE21-NAT-ES-LIFE KANTAU-RIBAI (101074197). 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Navarre Registro ictiológico de Navarra (1978-2015). Base de datos inédita. 2016.

- Ballesteros, F.; Vázquez, V.M. Evaluación de las mortalidad de peces tras su paso por turbinas hidroeléctricas en ríos del norte de España. Ecología 2001, 275–284. [Google Scholar]

- Skalski, J.R.; Townsend, R.; Lady, J.; Giorgi, A.E.; Stevenson, J.R.; McDonald, R.D. Estimating route-specific passage and survival probabilities at a hydroelectric project from smolt radiotelemetry studies. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2002, 59, 1385–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heisey, P.G.; Mathur, D.; D’Allesandro, L. A new technique for assessing fish passage survival at hydro power stations. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the workshop on fish passage at hydroelectric developments, 1993; pp. 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Tuononen, E.I.; Cooke, S.J.; Timusk, E.R.; Smokorowski, K.E. Extent of injury and mortality arising from entrainment of fish through a Very Low Head hydropower turbine in central Ontario, Canada. Hydrobiologia 2022, 849, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salalila, A.; Martinez, J.; Tate, A.; Acevedo, N.; Salalila, M.; Deng, Z.D. Balloon Tag Manufacturing Technique for Sensor Fish and Live Fish Recovery. J. Vis. Exp. 2023, e65632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathur, D.; Heisey, P.G.; Euston, E.T.; Skalski, J.R.; Hays, S. Turbine passage survival estimation for chinook salmon smolts (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) at a large dam on the Columbia River. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1996, 53, 542–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MyCircuits The Sentinel board. Available online: https://github.com/MyCircuitsTV/Sentinel (accessed on 17 Sep 2023).

- Adafruit Industries Adafruit BNO055 Absolute Orientation Sensor. Adafruit Industries. Available online: https://learn.adafruit.com/adafruit-bno055-absolute-orientation-sensor (accessed on 25 Feb 2020).

- Becker, J.M.; Abernathy, C.S.; Dauble, D.D. Identifying the effects on fish of changes in water pressure during turbine passage; EERE Publication and Product Library: Washington, DC (United States), 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, R.; Deschênes, C.; O’Neil, C.; Leclerc, M. VLH: development of a new turbine for very low head sites. Proceeding 15th Waterpower 2007, 10, 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, J.J.; Deng, Z.D.; Titzler, P.S.; Duncan, J.P.; Lu, J.; Mueller, R.P.; Tian, C.; Trumbo, B.A.; Ahmann, M.L.; Renholds, J.F. Hydraulic and biological characterization of a large Kaplan turbine. Renew. energy 2019, 131, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, M.; Pander, J.; Geist, J. Evaluation of external fish injury caused by hydropower plants based on a novel field-based protocol. Fish. Manag. Ecol. 2017, 24, 240–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boys, C.A.; Pflugrath, B.D.; Mueller, M.; Pander, J.; Deng, Z.D.; Geist, J. Physical and hydraulic forces experienced by fish passing through three different low-head hydropower turbines. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2018, 69, 1934–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, T.C.; Hecker, G.E.; Faulkner, H.B.; Jansen, W. Development of a more fish-tolerant turbine runner, advanced hydropower turbine project; Worcester Polytechnic Inst.: Holden, MA (United States); Alden Research Lab …, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- EPRI Report No. TR-101231, Project 2694-01.; EPRI Fish entrainment and turbine mortality review and guidelines. Prepared by Stone & Webster Environmental Services. Electric Power Research Institute: California, USA, 1992.

- Pflugrath, B.D.; Mueller, R.P.; Deters, K.A.; Watson, S.M.; Schneider, A.D.; Deng, Z.D. Maximizing Safe Passage for Large Fish: Evaluating Survival of Rainbow Trout Through a Novel Hydropower Turbine. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2025, 100801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Turbine | N | Fork length (mm)* | |

| Mean ± SD | Range | ||

| T1 (Ø: 1.20 m) | 2 | 153 ± 14 | 95 - 190 |

| T2 (Ø: 1.50 m) | 20 | 161 ± 7 | 130 - 190 |

| Turbine | Fork length | After turbine |

After 24 hours |

Cause of death | Injury type | Me just after turbine passage | Me after 24 hours |

| T1 | 15 | Dead | Turbine passage | Decapitation | 45.5%* (5/11) |

81.8%* (9/11) | |

| 15.8 | Dead | Turbine passage | Decapitation | ||||

| 17.8 | Dead | Turbine passage | Decapitation | ||||

| 16.4 | Dead | Turbine passage | Decapitation | ||||

| 17 | Dead | Turbine passage | Decapitation | ||||

| 19 | Alive | Dead | Turbine passage | Stomach rupture | |||

| 11.5 | Alive | Dead | Turbine passage | Eye embolism | |||

| 18 | Alive | Dead | Undetermined | ||||

| 18.5 | Alive | Dead | Undetermined | ||||

| 9.5 | Alive | Alive | |||||

| 10.5 | Alive | Alive | |||||

| T2 | 17.5 | Dead | Turbine passage | Decapitation | 11.1%* (1/9) |

66.7%* (6/9) | |

| 15.5 | Alive | Dead | Turbine passage | Eye embolism | |||

| 17.8 | Alive | Dead | Turbine passage | Stomach rupture | |||

| 16 | Alive | Dead | Turbine passage | Spinal cord brake | |||

| 19 | Alive | Dead | Undetermined | ||||

| 17 | Alive | Dead | Undetermined | ||||

| 15 | Alive | Alive | |||||

| 18.2 | Alive | Alive | |||||

| 17.6 | Alive | Alive |

|

MORTALITY (M ± SE) |

Mc = 5% | Mc = 20% | ||||

| M (%) | SE | IC (95%) | M (%) | SE | IC (95%) | |

| T1* | 80.9 | 10.8 | 56.8 – 100 | 77.3 | 11.1 | 52.6 – 100 |

| T2* | 64.9 | 9.9 | 42.1 – 87.7 | 58.3 | 10.8 | 33.4 – 83.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).