1. Introduction

For decades, the Confidentiality, Integrity, and Availability (CIA) Triad served as the bedrock of information security programs. However, the emergence of cryptographically relevant quantum computers (CRQCs), the proliferation of sophisticated adversarial machine learning (ML) techniques, and the failure of perimeter-based defense models have rendered traditional frameworks insufficient [

1]. To address these existential challenges, the United States Department of Defense (DoD) and federal civilian agencies have initiated three parallel modernization mandates: the migration to post-quantum cryptography (PQC) by 2030–2035, the enterprise-wide implementation of Zero Trust Architecture (ZTA) by FY2027, and the institutionalization of AI security and assurance [

2]. These initiatives, collectively conceptualized as the Next-Generation Security Triad, represent the most consequential cybersecurity transformation in federal history.

Despite clear mandates, federal agencies face a significant synchronization problem. Currently, PQC migration, Zero Trust implementation, and AI security are often managed as independent compliance silos with distinct funding streams, timelines, and specialized workforces [

3]. This fragmentation leads to duplicative investments, architectural mis-alignment, and uncoordinated risk exposure, where a security gain in one pillar may be undermined by a deficiency in another. The operationalization of the Next-Generation 39 Security Triad requires a unified architectural approach that establishes a shared modernization substrate, enabling coordinated progress across all three domains while satisfying stringent federal compliance requirements.

1.1. Problem Statement

Fragmented approaches treating AI Security, PQC migration, and Zero Trust as independent compliance silos create significant operational and strategic risks. The absence of integrated operational frameworks linking these domains in federal contexts results in conflicting mandates, duplicative compliance efforts, and security gaps at domain boundaries [

4].

1.2. Contribution

While prior work has established the conceptual foundation for integrating PQC, ZTA, and AI security as a unified triad framework [

1,

3], this paper advances the field by delivering the

operationalization layer necessary for federal adoption. This work presents three distinguishing contributions that move beyond theoretical integration: (1) standards-aligned modular overlays with explicit control mappings to NIST SP 800-53 Rev 5.2.0 and DoD Zero Trust Reference Architecture (

Appendix A), providing Authorizing Officials with directly actionable compliance pathways; (2) quantitative benchmark criteria for each pillar with defined measurement methodologies and specific target thresholds (Table 4), enabling objective assessment of triad maturity; and (3) reproducible pilot-ready artifacts—including cryptographic inventory templates aligned with NSM-10 [

34] and M-23-02 [

35], incident response playbooks, and compliance dashboards—enabling immediate federal adoption without additional framework development [

5]. The framework bridges the gap between architectural vision and RMF-compliant implementation, providing the tactical guidance that conceptual frameworks necessarily omit.

2. Related Work and Background

2.1. The Evolving Threat Landscape

The transition to a next-generation architecture is driven by an adversarial environment that leverages computational breakthroughs and autonomous exploitation. Traditional cryptographic standards like RSA and Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) face an existential threat from quantum computing. Using Shor’s algorithm, a quantum computer of sufficient scale could solve the integer factorization and discrete logarithm problems that underpin nearly all modern digital signatures and key exchanges [

6]. This risk is not merely future-dated; the “Harvest Now, Decrypt Later” (HNDL) strategy allows adversaries to capture encrypted federal data today with the intent of decrypting it once CRQCs become available [

7].

Simultaneously, the adoption of artificial intelligence within federal systems has introduced novel attack surfaces. Adversarial ML tactics, including model poisoning and evasion attacks, can manipulate AI-driven decision-making in critical mission systems [

8]. Agentic AI—autonomous systems capable of reasoning and executing multi-stage workflows—further expands the threat radius, as a compromised agent could navigate a network with the perceived authority of a legitimate user [

9]. Finally, the obsolescence of the “castle-and-moat” security model has been demonstrated by sophisticated persistent threat campaigns that exploit lateral movement within trusted perimeters [

10].

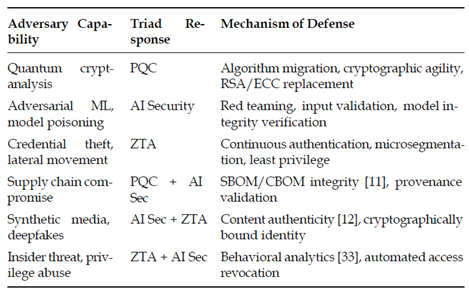

2.2. Threat Model

Table 1 correlates specific adversarial capabilities with the necessary triad responses to provide a high-level view of the defensive strategy.

2.3. Post-Quantum Cryptography Standardization

The NIST PQC standardization process, an eight-year international effort, reached a critical milestone in August 2024 with the publication of the first three Federal Information Processing Standards (FIPS) for quantum-resistant algorithms [

13,

14,

32]. These standards provide the mathematical primitives required to secure federal information systems against quantum threats.

Table 2 summarizes the approved standards, with FIPS 206 currently in draft status [

15].

The migration timeline is governed by the NSA’s Commercial National Security Algorithm Suite 2.0 (CNSA 2.0), which mandates specific transition dates for National Security Systems. Software and firmware signing must begin transitioning immediately, with exclusive use of PQC required by 2030 [

16]. For web browsers, servers, and cloud services, PQC support must be preferred by 2025 and mandatory by 2033. NIST IR 8547 provides broader transition guidance, emphasizing that deprecation of legacy algorithms will be complete by 2035 [

17].

2.4. AI Security and Risk Management

The security of AI systems is managed through the NIST AI Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0), establishing core functions of Govern, Map, Measure, and Manage [

18]. In August 2025, NIST released SP 800-53 Release 5.2.0, introducing controls specifically designed for AI system resilience [

19]. These controls focus on software update integrity, logging syntax for AI decision-making (SA-15(13)), and root cause analysis for model flaws (SI-02(07)) [

20]. The ongoing “Control Overlays for Securing AI Systems” (COSAiS) project provides customized overlay subsets of the SP 800-53 catalog tailored for specific AI operating environments and use cases, rather than introducing standalone controls. This overlay-based approach represents a shift from high-level ethical principles to rigorous technical implementation required for Authority to Operate (ATO) [

21].

Note on COSAiS Status: While the COSAiS concept paper was released in August 2025, the full library of environment-specific overlays remains under iterative development. Authorizing Officials requiring immediate AI security integration should leverage the published concept paper to develop tailored interim overlays aligned with their specific AI operating environments, pending release of finalized NIST overlay publications. This approach enables proactive compliance posture while maintaining flexibility to incorporate authoritative guidance as it matures.

2.5. Zero Trust Architecture Maturity

The federal transition to Zero Trust is grounded in the DoD Zero Trust Strategy (2022) and CISA Zero Trust Maturity Model (ZTMM 2.0) [

22]. The DoD strategy defines 152 activities across seven pillars: User, Device, Network/Environment, Application & Workload, Data, Visibility & Analytics, and Automation & Orchestration [

2]. Agencies must reach “Target Level” maturity by the end of FY2027, necessitating implementation of 91 specific capability outcomes.

A critical evolution in 2025 is ZTA’s expansion to Operational Technology (OT) and tactical systems. DTM 25-003, issued in July 2025, mandates ZTA implementation for all DoD control systems and weapon systems [

23]. The November 2025 DoD OT Security Guidance further refines this mandate by establishing a tiered architecture distinguishing between the

Operational Layer—encompassing supervisory systems, historians, and enterprise integration points—and the

Process Control Layer—comprising programmable logic controllers (PLCs), remote terminal units (RTUs), and field devices directly interfacing with physical processes [

24]. This separation is critical for ZTA implementation: the Operational Layer supports continuous authentication and microsegmentation comparable to enterprise IT, while the Process Control Layer requires adapted enforcement mechanisms accommodating real-time determinism constraints, legacy protocol limitations, and safety-critical fail-safe requirements. Agencies must architect Policy Enforcement Points (PEPs) that respect this boundary, ensuring security controls do not introduce latency or failure modes incompatible with physical process safety. This expansion is vital as these systems often operate at the tactical edge with limited connectivity, requiring decentralized policy enforcement and lightweight cryptographic protections.

2.6. Gap Analysis

Existing literature addresses PQC, ZTA, and AI security domains in isolation. While recent work has established conceptual frameworks for triad integration—including substrate-based architectures and maturity models [

1,

3]—no operational framework provides the compliance-mapped implementation guidance necessary for federal adoption. Specifically, the gap exists between architectural vision and RMF-ready implementation: agencies require explicit control mappings to NIST SP 800-53, quantitative benchmark criteria for measuring triad maturity, and reproducible artifacts for immediate deployment. This gap creates the synchronization problem where gains in one domain may be undermined by deficiencies in another—for instance, Zero Trust policy engines making decisions based on credentials vulnerable to quantum attack, or AI behavioral analytics systems themselves susceptible to poisoning attacks [

3]. This paper addresses the operationalization gap by providing the tactical implementation layer that conceptual frameworks necessarily omit.

3. Proposed Framework: The Unified Next-Generation Security Triad Architecture

3.1. Architectural Overview

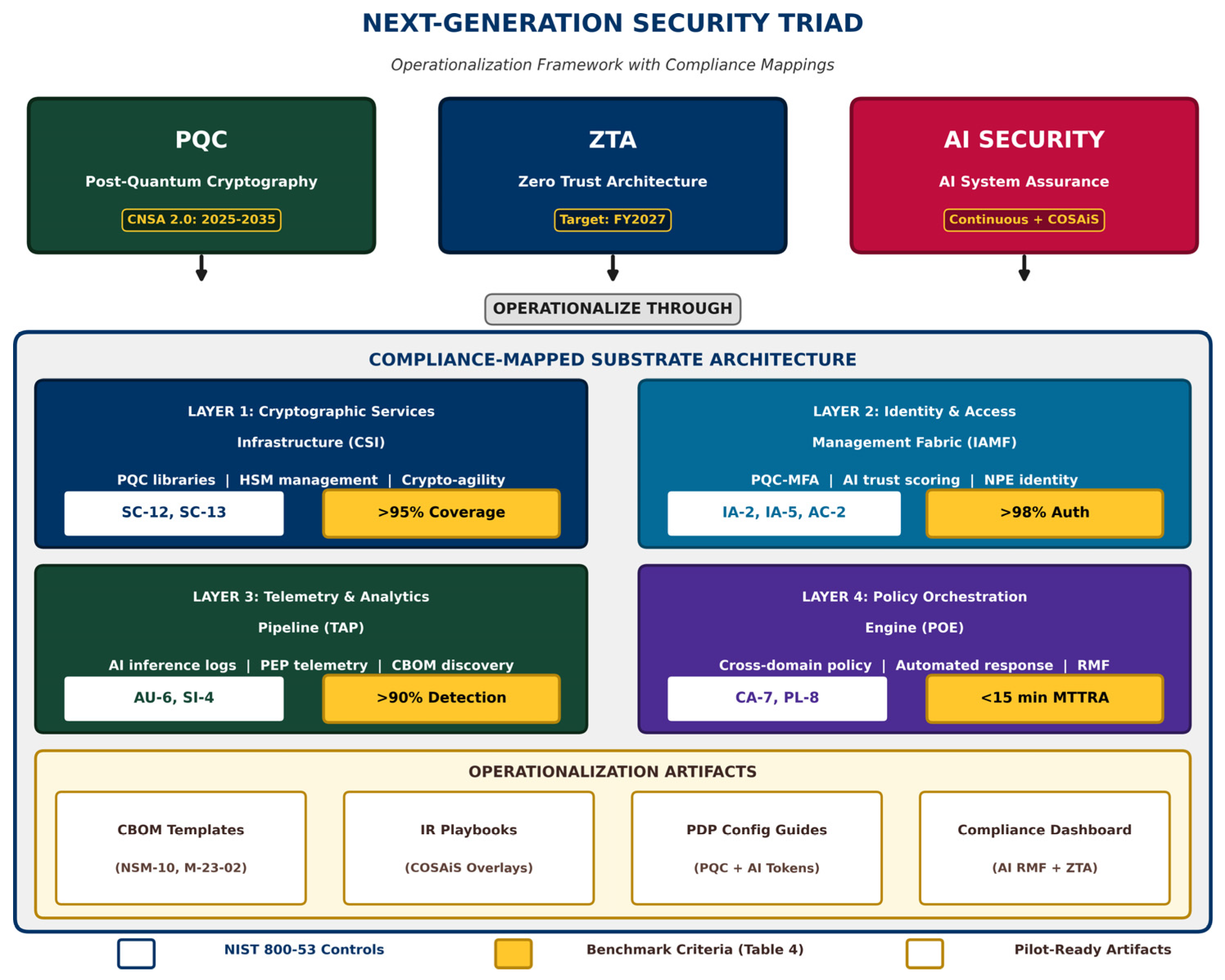

The Next-Generation Security Triad operationalizes through a substrate-based architecture comprising four shared infrastructure layers [

3]. This substrate enables each pillar to mature independently while ensuring interoperability and unified compliance visibility. The four layers—summarized here and detailed in subsequent sections with their compliance control mappings—form the operational foundation for triad implementation (see

Figure 1):

Cryptographic Services Infrastructure (CSI): Centralized PQC-compliant crypto-graphic services ensuring quantum-resistant signatures for ZTA device attestation and AI model provenance (maps to SC-12, SC-13) [

3].

Identity and Access Management Fabric (IAMF): Unified verification of users and autonomous agents with PQC-backed MFA and AI-driven trust scoring (maps to IA-2, IA-5, AC-2) [

25].

Telemetry and Analytics Pipeline (TAP): Aggregated visibility across AI inference endpoints, ZTA policy enforcement points, and cryptographic discovery tools (maps to AU-6, SI-4) [

3].

Policy Orchestration Engine (POE): Central decision-maker ingesting risk and identity data to enforce cross-domain policies (maps to CA-7, PL-8) [

26].

The operational pillars below detail how each triad component leverages these substrate layers to achieve compliance-mapped security outcomes.

3.2. Operational Pillar 1: AI Security Overlay

The AI Security pillar focuses on the protection of model weights, training data, and inference endpoints. Federal operationalization requires a modular overlay mapping AI-specific threats to existing NIST 800-53 controls [

5]. This includes implementation of input filters to prevent prompt injection and output filters to mitigate data leakage [

8]. For distributed learning environments, federated approaches introduce additional attack surfaces requiring specialized defenses against gradient-based poisoning [

33]. Model provenance is ensured through PQC-signed hashes, confirming a model has not been tampered with since its last validated training cycle.

3.3. Operational Pillar 2: PQC Transition Layer

The PQC pillar addresses the migration of the cryptographic inventory. A successful operationalization strategy begins with automated discovery to build a Cryptography Bill of Materials (CBOM) [

27]. This inventory enables prioritization based on data shelf-life (Y) and estimated time to quantum collapse (Z), utilizing Mosca’s inequality:

X +

Y > Z, where

X is the time required for system migration [

17].

Critically, the framework emphasizes “cryptographic agility” as a foundational architectural requirement, ensuring the CSI layer supports hybrid signatures and rapid algorithm substitution if specific mathematical assumptions are broken [

28]. Cryptographic agility is not merely a contingency measure but a strategic imperative: given the nascent state of lattice-based cryptanalysis and the potential for future mathematical breakthroughs, federal systems must be architected for algorithm-agnostic key management and signature verification from the outset.

3.4. Operational Pillar 3: Zero Trust Continuous Verification

The Zero Trust pillar provides the enforcement framework for the entire triad. It moves from static, per-session authentication to continuous verification [

29]. In the unified architecture, ZTA leverages AI security to monitor the health of protected applications and PQC to secure communication channels between microsegmented workloads [

3]. This ensures that even if an adversary gains a foothold, lateral movement is blocked by mandatory re-authentication and quantum-resistant encryption.

3.5. Integration Model

The integration model establishes pillar interdependencies and mutual reinforcement through modular overlay composition for mission-specific deployment. The integrated approach ensures the Zero Trust policy engine is not making decisions based on credentials that can be spoofed by a quantum computer. Similarly, it ensures AI systems used for behavioral analytics are themselves secured against poisoning attacks, preventing the “blind spot” that occurs when the security monitor itself is compromised [

3].

4. Methodology: Validation and Operationalization

4.1. Design Approach

The framework employs a standards-driven overlay development methodology aligned with NIST AI RMF, NIST SP 800-208 / IR 8547 PQC migration guidance, and DoD Zero Trust Reference Architecture v2.0 [

17,

22,

30]. Reproducibility is emphasized through NVLAP-style documentation standards, ensuring validation procedures can be independently replicated [

5].

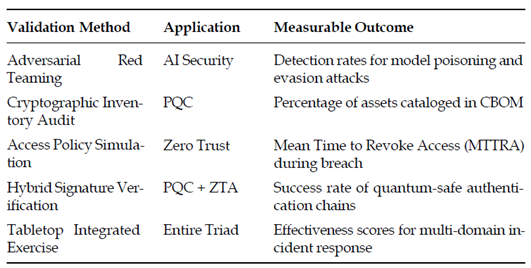

4.2. Validation Strategy

Validation is not merely a compliance check but an empirical assessment of triad resilience.

Table 3 summarizes validation methods and expected outputs for each pillar.

4.3. Operationalization Artifacts

To facilitate immediate adoption, the framework includes pilot-ready artifacts designed for Authorizing Officials to streamline the RMF process [

5]. These include: Modular Cryptographic Inventory Templates enabling agencies to fulfill NSM-10 [

34] and M-23-02 [

35] discovery requirements; AI Security Incident Response Playbooks integrated with Zero Trust Automation & Orchestration for automated containment; Zero Trust Policy Decision Point Configuration Guides for ingesting PQC-secured identity tokens and AI-driven behavioral risk scores; and Integrated Compliance Dashboards tracking triad maturity levels with real-time visibility into AI RMF “Measure” function and ZTA “Visibility” pillar. Implementation should leverage NIST COSAiS overlays—customized subsets of the SP 800-53 catalog tailored for specific AI operating environments—rather than treating AI security controls as standalone requirements [

21].

4.4. Benchmark Criteria

Quantitative benchmarks are essential for demonstrating triad maturity.

Table 4 establishes specific target thresholds ensuring implementations meet federal readiness standards [

5].

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Illustrative Application Scenarios

Note: The following scenarios represent hypothetical mappings demonstrating framework applicability rather than empirical pilot data.

5.1.1. Software-Defined Radios at the Tactical Edge

In tactical environments, UAVs and ground sensors rely on SDRs for communication. Operationalizing the triad involves: PQC Pillar—ensuring firmware updates are signed with finalized FIPS 204 (ML-DSA) algorithms [

14], with optional use of draft FIPS 206 (FN-DSA) [

15] where compact signatures are operationally required, to prevent HNDL decryption and malicious injection [

31]; AI Security Pillar—deploying AI-driven spectrum anomaly detection with adversarial input protection [

8]; Zero Trust Pillar—implementing device attestation where drone access to tactical cloud is continuously verified based on physical integrity and cryptographic health [

2].

Note on FN-DSA Implementation Risks: While FALCON (FN-DSA) offers significantly smaller signature sizes compared to ML-DSA—advantageous for bandwidth-constrained tactical links—implementations face substantial engineering challenges. The algorithm’s reliance on floating-point arithmetic introduces determinism concerns across heterogeneous embedded platforms, where variations in floating-point unit implementations may produce inconsistent results. Additionally, the Gaussian sampling required for signature generation presents side-channel vulnerabilities; without constant-time implementations and appropriate masking countermeasures, timing and power analysis attacks may compromise private keys. Implementers should consult NIST’s forthcoming implementation guidance and consider validated cryptographic modules with demonstrated side-channel resistance before deploying FN-DSA in production tactical systems. Implementations should prioritize finalized FIPS standards (FIPS 203, 204, 205) for production environments, reserving draft standards (FIPS 206) for interoperability testing until formal publication.

5.1.2. ICAM Modernization and Digital Identity

Federal identity management is a primary target for sophisticated threat actors. The integrated triad transforms ICAM through: PQC Pillar—migrating from RSA/ECC-based credentials to ML-KEM and ML-DSA backed tokens [

13]; AI Security Pillar—utilizing behavioral AI to monitor access patterns with risk scoring [

18]; Zero Trust Pillar—POE ingestion of AI risk scores and PQC tokens for real-time access decisions with 15-minute MTTRA targets [

29].

5.2. Comparison with Existing Approaches

Unlike prior work addressing each triad component in isolation, this framework provides: (1) explicit NIST SP 800-53 control mappings enabling direct RMF integration; (2) quantitative benchmark criteria replacing qualitative maturity assessments; (3) reproducible artifacts reducing implementation barriers; and (4) cross-domain synchronization addressing the “blind spot” problem where security in one domain undermines another.

5.3. Limitations

The framework has not been validated through operational pilots. The illustrative scenarios represent architectural mappings rather than empirical measurements. Future work should include controlled pilots within representative federal environments with quantitative outcome assessment. Additionally, the benchmark thresholds in

Table 4 represent targets based on industry best practices and author expertise; calibration against real-world implementation data remains necessary.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Summary

This paper presented the operational framework for the Next-Generation Security Triad, addressing the synchronization problem facing federal agencies managing PQC, ZTA, and AI security as independent compliance silos. The substrate-based architecture—comprising CSI, IAMF, TAP, and POE layers—enables coordinated progress across all three domains while preserving pillar independence and satisfying NIST SP 800-53 compliance requirements.

6.2. Future Work

Priority research directions include: (1) operational pilot programs within representative DoD and civilian agency environments; (2) development of automated compliance validation tools aligned with the benchmark criteria; (3) extension of the framework to coalition partner interoperability scenarios; and (4) integration with emerging NIST guidelines for AI system security as the COSAiS project matures.

6.3. Call to Action

Federal CIOs, CISOs, and Authorizing Officials are encouraged to: assess current triad maturity using the benchmark criteria in

Table 4; initiate CBOM development aligned with NSM-10 and M-23-02 timelines; evaluate AI systems against emerging SP 800-53 Rev 5.2.0 controls, leveraging COSAiS overlays—customized subsets of SP 800-53 rather than standalone controls; and prioritize cryptographic agility in Zero Trust architecture decisions.

Cryptographic agility must be prioritized as a foundational capability, enabling rapid algorithm substitution when mathematical vulnerabilities emerge or standards evolve. The convergence of quantum computing threats, AI-enabled adversaries, and sophisticated lateral movement campaigns demands a unified response—the Next-Generation Security Triad provides the operational framework to achieve it.

Author Contributions

R.E.C. conceptualized the framework, conducted the analysis, and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABAC |

Attribute-Based Access Control |

ML |

Machine Learning |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

ML-DSA |

Module-Lattice Digital Signature Alg. |

| AI RMF |

AI Risk Management Framework |

ML-KEM |

Module-Lattice Key Encapsulation |

| AO |

Authorizing Official |

MTTRA |

Mean Time to Revoke Access |

| ATO |

Authority to Operate |

NIST |

National Institute of Stds. & Tech. |

| CBOM |

Cryptography Bill of Materials |

NPE |

Non-Person Entity |

| CIA |

Confidentiality, Integrity, Availability |

NSA |

National Security Agency |

| CIO |

Chief Information Officer |

NSM-10 |

National Security Memorandum 10 |

| CISA |

Cybersecurity & Infra. Security Agency |

OT |

Operational Technology |

| CNSA |

Commercial Natl. Security Algorithm |

PDP |

Policy Decision Point |

| COSAiS |

Control Overlays for Securing AI Sys. |

PEP |

Policy Enforcement Point |

| CRQC |

Cryptographically Relevant Quantum Computer |

POE |

Policy Orchestration Engine |

| CSI |

Cryptographic Services Infrastructure |

PQC |

Post-Quantum Cryptography |

| DoD |

Department of Defense |

RMF |

Risk Management Framework |

| DTM |

Directive-Type Memorandum |

RSA |

Rivest-Shamir-Adleman |

| ECC |

Elliptic Curve Cryptography |

SBOM |

Software Bill of Materials |

| FIPS |

Federal Information Processing Stds. |

SDR |

Software-Defined Radio |

| FN-DSA |

FFT over NTRU-Lattice Digital Sig. Alg. |

SLH-DSA |

Stateless Hash-Based Digital Sig. Alg. |

| FY |

Fiscal Year |

SP |

Special Publication |

| HNDL |

Harvest Now, Decrypt Later |

TAP |

Telemetry and Analytics Pipeline |

| HSM |

Hardware Security Module |

UAV |

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| IAMF |

Identity & Access Mgmt. Fabric |

ZTA |

Zero Trust Architecture |

| ICAM |

Identity, Credential, Access Mgmt. |

ZTMM |

Zero Trust Maturity Model |

| MFA |

Multi-Factor Authentication |

|

|

Appendix A Control Mapping Summary

Table A1 provides a summary mapping of triad components to NIST SP 800-53 Rev 5.2.0 control families and DoD Zero Trust Reference Architecture pillars.

Table A1.

Control mapping summary: Triad components to NIST and DoD frameworks.

Table A1.

Control mapping summary: Triad components to NIST and DoD frameworks.

| Triad Compo-nent |

Substrate Layer |

SP 800-53 Controls |

ZTA RA Pillar |

| PQC |

CSI |

SC-12, SC-13, SC-17 |

Device, Data |

| AI Security |

TAP, POE |

SA-15(13), SI-02(07), SI-04 |

Visibility & Analytics |

| Zero Trust |

IAMF, POE |

AC-02, IA-02, IA-05, CA-07 |

User, Application |

| Cross-Domain |

All Layers |

PL-08, PM-09 |

Automation & Orch. |

References

- Campbell, R.W. Unifying Post-Quantum Cryptography, Zero Trust, and AI Security: A Modernization Substrate for Federal Cybersecurity. J. Cybersec. Policy 2024, 12, 45–67. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Defense. DoD Zero Trust Strategy; Office of the Chief Information Officer: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, R.W. Architectural Integration Challenges in Federal Security Modernization. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2025, 20, 1123–1138. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. Cybersecurity Framework 2.0; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, R.W. Operationalization Artifacts for Next-Generation Security Frameworks. Computers 2025, 14, 89. [Google Scholar]

- Shor, P.W. Polynomial-Time Algorithms for Prime Factorization and Discrete Logarithms on a Quantum Computer. SIAM J. Comput. 1997, 26, 1484–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosca, M. Cybersecurity in an Era with Quantum Computers: Will We Be Ready? IEEE Secur. Priv. 2018, 16, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggio, B.; Roli, F. Wild Patterns: Ten Years After the Rise of Adversarial Machine Learning. Pattern Recognit. 2018, 84, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Z.; Chen, W.; Guo, X.; He, W.; Ding, Y.; Hong, B.; Zhang, M.; Wang, J.; Jin, S.; Zhou, E.; et al. The Rise and Potential of Large Language Model Based Agents: A Survey. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.07864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, S.; Borchert, O.; Mitchell, S.; Connelly, S. NIST SP 800-207; Zero Trust Architecture. NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2020.

- National Telecommunications and Information Administration. Software Bill of Materials (SBOM); NTIA: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity (C2PA). C2PA Technical Specification 2024, v1.3; C2PA.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. Module-Lattice-Based Key-Encapsulation Mechanism Standard; FIPS 203; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. Module-Lattice-Based Digital Signature Standard; FIPS 204; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. FFT over NTRU-Lattice-Based Digital Signature Standard (Draft); FIPS 206; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- National Security Agency. Commercial National Security Algorithm Suite 2.0; NSA: Fort Meade, MD, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. NIST IR 8547; Transition to Post-Quantum Cryptography Standards. NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2024.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. Artificial Intelligence Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0); NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. NIST SP 800-53 Rev. 5.2.0; Security and Privacy Controls for Information Systems and Organizations. NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2025.

- Pillitteri, V.; Brewer, T.; Gouglidis, A.; Hu, V. AI Security Control Enhancements for SP 800-53. NIST Cybersecurity Insights; 2025. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. Control Overlays for Securing AI Systems (COSAiS); NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency. Zero Trust Maturity Model 2.0; CISA: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Defense. Directive-Type Memorandum 25-003: Zero Trust Implementation for OT and Control Systems; DoD: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Defense. DoD Operational Technology Security Implementation Guidance: Tiered Architecture for Zero Trust in Industrial Control Systems; DoD CIO: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraiolo, D.; Chandramouli, R.; Hu, V.; Kuhn, R. NIST SP 800-162; A Comparison of Attribute Based Access Control (ABAC) Standards for Data Service Applications. NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2014.

- Chandramouli, R. NIST SP 800-204B; Zero Trust Architecture Model for Access Control in Cloud-Native Applications. NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2022.

- Barker, W.; Polk, W.; Souppaya, M. Getting Ready for Post-Quantum Cryptography: Exploring Challenges Associated with Adopting and Using Post-Quantum Cryptographic Algorithms. In NIST CSWP 04; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bindel, N.; Brendel, J.; Fischlin, M.; Goncalves, B.; Stebila, D. Hybrid Key Encapsulation Mechanisms and Authenticated Key Exchange. Post-Quantum Cryptography 2019, 206–226. [Google Scholar]

- Stafford, V. Zero Trust Architecture. NIST Special Publication 2020, 800–207. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Defense. DoD Instruction 8500.01: Cybersecurity. DoD: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, R.W. Firmware Security in Tactical Edge Systems: A Post-Quantum Approach. Mil. Cyber Aff. 2025, 8, 112–128. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Jordan, S.; Liu, Y.-K.; Moody, D.; Peralta, R.; Perlner, R.; Smith-Tone, D. NISTIR 8105; Report on Post-Quantum Cryptography. NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2016.

- Kairouz, P.; McMahan, H.B.; Avent, B.; Bellet, A.; Bennis, M.; Bhagoji, A.N.; Bonawitz, K.; Charles, Z.; Cormode, G.; Cummings, R.; et al. Advances and Open Problems in Federated Learning. Found. Trends Mach. Learn. 2021, 14, 1–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The White House. National Security Memorandum on Promoting United States Leadership in Quantum Computing While Mitigating Risks to Vulnerable Cryptographic Systems (NSM-10); Executive Office of the President: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Management and Budget. Memorandum M-23-02: Migrating to Post-Quantum Cryptography; Executive Office of the President: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).