Submitted:

24 December 2025

Posted:

25 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Main Groups of Aroma Active Components in Different Cheese Varieties

3. Examples of Cheese Aroma Studies Employing GC-O during the Period 2002-2022

3.1. Hard Cheeses (49-56% of Water)

3.2. Semi-Hard Cheeses (54-63% of Water)

3.3. Soft Cheeses (> 67% of Water)

3.4. Blue Mold Ripened Cheeses

3.5. Goat Milk Cheeses

3.6. Ewes Milk Cheeses

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aday, S.; Karagul-Yuceer, Y. Physicochemical and sensory properties of Mihalic cheese. Int. J. Food Prop. 2014, 17, 2207–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akira, A.; Kazuhiko, T.; Kenichi, U. (1996). Method for improving flavor of food or drink. U.S. Patent No 5,496,580. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

- Arora, G.; Cormier, F.; Lee, B. Analysis of odor-active volatiles in Cheddar cheese headspace by multidimensional GC/MS/sniffing. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1995, 43, 748–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avsar, Y.K.; Karagul-Yuceer, Y.; Drake, M.A.; Singh, T.K.; Yoon, Y.; Cadwallader, K.R. Characterization of nutty flavor in cheddar cheese. J. Dairy Sci. 2004, 87, 1999–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belitz, H.-D.; Grosch, W.; Schieberle, P. (2009). Food Chemistry. 4th edition. Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. [CrossRef]

- Berdagué, JL; Tournayre, P.; Cambou, S. Novel multi-gas chromatography-olfactometry device and software for the identification of odour-active compounds. J. Chromatogr. A 2007, 1146, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonini, A.; Dellacassa, E.; Ares, G.; Daners, G.; Godoy, A.; Boido, E.; Fariña, L. Fecal descriptor in honey: indole from a floral source as an explanation. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2022, 102, 6780–6785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscaini, E.; Van Ruth, S.; Biasoli, F.; Gasperi, F.; Märk, T.D. Gas Chromatography?Olfactometry (GC-O) and Proton Transfer Reaction?Mass Spectrometry (PTR-MS) Analysis of the flavor profile of Grana Padano, Parmigiano Reggiano, and Grana Trentino cheeses. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 1782–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carunchia-Whetstine, M.E.; Karagul-Yuceer, Y.; Avsar, Y.K.; Drake, M.A. Identification and quantification of character aroma components in fresh Chevre-style goat cheese. J. Food Sci. 2003, 68, 2441–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carunchia-Whetstine, M.E.; Cadwallader, K.R.; Drake, M.A. Characterization of Aroma Compounds Responsible for the Rosy/Floral Flavor in Cheddar Cheese. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 3126–3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhou, W.; Yu, H.; Yuan, J.; Tian, H. Evaluation of the perceptual interactions among aldehydes in a Cheddar cheese matrix according to odor threshold and aroma intensity. Molecules 2020, 25, 4308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhou, W.; Yu, H.; Yuan, J.; Tian, H. Characterization of major odor-active compounds responsible for nutty flavor in Cheddar cheese according to Chinese taste. Flav. Fragr. J. 2021, 36, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Liu, Z.; Yu, H.; Xu, Z.; Tian, H. Flavoromic determination of lactones in cheddar cheese by GC-MS-olfactometry, aroma extract dilution analysis, aroma recombination and omission analysis. Food Chem. 2022, 368, 130736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, K.R.; Reineccius, G.A. Aroma extract dilution analysis of aged Cheddar cheese. J. Food Sci. 1995, 60, 218–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornu, A.; Rabiau, N.; Kondjoyan, N.; Verdier-Metz, I.; Pradel, P.; Tournayre, P.; Berdague, J.L.; Martin, B. Odour-active compound profiles in Cantal-type cheese: Effect of cow diet, milk pasteurization and cheese ripening. Int. Dairy J. 2009, 19, 588–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curioni, P.M.G.; Bosset, J.O. Key odorants in various cheese types as determined by gas chromatography-olfactometry. Int. Dairy J. 2002, 12, 959–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Acampora Zellner, B.; Dugo, P.; Dugo, G.; MondelloL. Gas chromatography-olfactometry in food flavour analysis. J. Chromatogr. A 2008, 1186, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jesus Filho, M.; Klein, B.; Wagner, R.; Godoy, H.T. Key aroma compounds of Canastra cheese: HS-SPME optimization assisted by olfactometry and chemometrics. Food Res. Int. 2021, 150, 110788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dellacassa, E.; Minteguiaga, M. (2023). "Gas Chromatography-Olfactometry (GC-O) of essential oils and volatile extracts", in Essential Oils: Extraction Methods and Applications, ed. Inamuddin (New York, NY: Wiley-Scrivener), in press.

- Frank, D.C.; Owen, C.M.; Patterson, J. Solid phase microextraction (SPME) combined with gas-chromatography and olfactometry-mass spectrometry for characterization of cheese aroma compounds. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2004, 37, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, J.E.; Acree, T.E. Gas Chromatography Olfactometry (GC/O) of dairy products. Int. Dairy J. 1998, 8, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchsmann, P.; Stern, M.T.; Brügger, Y.-A.; Breme, K. Olfactometry Profiles and Quantitation of Volatile Sulfur Compounds of Swiss Tilsit Cheeses. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 7511–7521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, G.H.; Steltenkamp, R.; Tisserand, G.A. The gas chromatograph with human sensor: perfumer model. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1964, 116, 711–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gripon, J.C. (1997). "Flavour and texture in soft cheese", in Microbiology and Biochemistry of Cheese and Fermented Milk, ed. A. Law (New York, NY: Springer), 193-206.

- Guneser, O.; Karagul-Yuceer, Y. Characterisation of aroma-active compounds, chemical and sensory properties of acid-coagulated cheese: Circassian cheese. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2011, 64, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y.; Benoist, D.M.; Ameerally, A.; Drake, M.A. Sensory and chemical properties of Gouda cheese. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 1967–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karahadian, C.; Josephson, D.B.; Lindsay, R.C. Contribution of Penicillium sp. to the flavors of Brie and Camembert Cheese. J. Dairy Sci. 1985, 68, 1865–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubí?ková, J; Grosch, W. Evaluation of potent odorants of Camembert cheese by dilution and concentration techniques. Int. Dairy J. 1997, 7, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariaca, R.; Bosset, J.O. Instrumental analysis of volatile (flavour) compounds in milk and dairy products. Lait 1997, 77, 13–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moio, L.; Langlois, D.; Etievant, P.; Addeo, F. Powerful odorants in bovine, ovine, caprine and water buffalo milk determined by means of gas chromatography-olfactometry. J. Dairy Res. 1993, 60, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poveda, J.M.; Sánchez-Palomo, E.; Pérez-Coello, M.S.; Cabezas, L. Volatile composition, olfactometry profile and sensory evaluation of semi-hard Spanish goat cheeses. Dairy Sci. Technol. 2008, 88, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, M.; Reineccius, G. Potent aroma compounds in Parmigiano Reggiano cheese studied using a dynamic headspace (purge-trap) method. Flavour Fragr. J. 2003a, 18, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, M.; Reineccius, G. Static Headspace and Aroma Extract Dilution Analysis of Parmigiano Reggiano cheese. J. Food Sci. 2003b, 68, 794–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, M.; Reineccius, G. Quantification of aroma compounds in Parmigiano Reggiano cheese by a dynamic headspace Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry technique and calculation of odor activity value. J. Dairy Sci. 2003c, 86, 770–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roger, S.; Degas, C.; Gripon, J.C. Production of phenyl ethyl alcohol and its esters during ripening of traditional camembert. Food Chem. 1988, 28, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sádecká, J; Kolek, E.; Pangallo, D.; Valík, L.; Kuchta, T. Principal volatile odorants and dynamics of their formation during the production of May Bryndza cheese. Food Chem. 2014, 150, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sádecká, J.; Šaková, N.; Pangallo, D.; Kore?ová, J.; Kolek, E.; Puškarová, A.; Bu?ková, M.; Valík, L.; Kuchta, T. Microbial diversity and volatile odour-active compounds of barrelled ewes’ cheese as an intermediate product that determines the quality of winter bryndza cheese. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 70, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Liu, J. GC-O-MS technique and its applications in food flavor analysis. Food Res. Int. 2018, 114, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.; Wick, C.; Castada, H.Z.; Kent, K.; Harper, W.J. Discrimination of Swiss cheese from 5 different factories by high impact volatile organic compound profiles determined by odor activity value using Selected Ion Flow Tube Mass Spectrometry and odor threshold. J. Food Sci. 2013, 78, C1509–C1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, M.; Martin, C.; Mercier, F.; Tournayre, P.; Berdagué, J-L; Thomas-Danguin, T.; Guichard, E. Investigating semi-hard cheese aroma: Relationship between sensory profiles and gas chromatography-olfactometry data. Int. Dairy J. 2012, 26, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Xu, X.; Chen, C.; Yu, H. Flavoromics approach to identifying the key aroma compounds in traditional Chinese milk fan. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 9639–9650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Yang, Z.J.; Wang, Y.D.; Cao, Y.P.; Wang, B.; Liu, Y. The key aroma compounds and sensory characteristics of commercial Cheddar cheeses. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 7555–7571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zabaleta, L.; Gourrat, K.; Barron, L.J.B.; Albisua, M.; Guichard, E. Identification of odour-active compounds in ewes’ raw milk commercial cheeses with sensory defects. Int. Dairy J. 2016, 58, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Shi, X.; Wang, B. A Review on the General Cheese Processing Technology, Flavor Biochemical Pathways and the Influence of Yeasts in Cheese. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 703284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

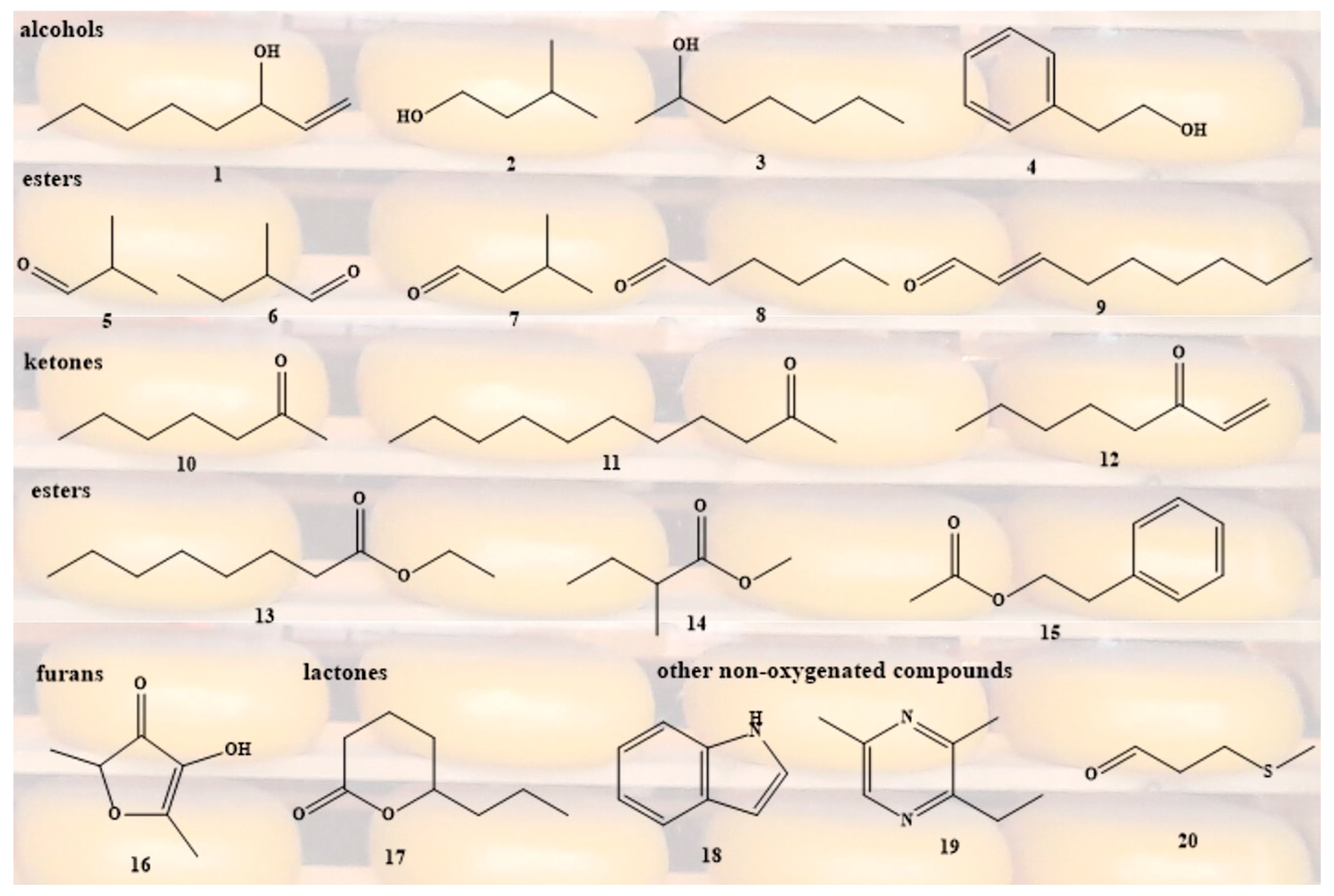

| Compound | Odour descriptor | Thresholds (µg/kg)1 |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-octen-3-ol (1) | mushrooms, green | 1 | Wang et al. (2021) |

| 3-methyl-1-butanol (2) | alcoholic, winey, fruity | 4750 | Qian & Reineccius (2003c) |

| 2-heptanol (3) | mushroom | 410 | Qian & Reineccius (2003c) |

| 2-phenylethanol (4) | floral | 9 | Gripon (1997) |

| 2-methylpropanal (5) | Pungent, varnish, fruity | 150 | Qian & Reineccius (2003c) |

| 2-methylbutanal (6) | Malty, almond, cacao, apple-like | 175 | Chen et al. (2020) |

| 3-methylbutanal (7) | Malty, nutty, almond, cocoa | 150 | Chen et al. (2020) |

| n-hexanal (8) | green, grassy | 5 | Wang et al. (2021) |

| 2-(E)-nonenal (9) | cucumber | 0.3 | Wang et al. (2021) |

| 2-heptanone (10) | fruity, sweet | 1500 | Qian & Reineccius (2003c) |

| 2-undecanone (11) | floral | 6.2 | Wang et al. (2021) |

| 1-octen-3-one (12) | mushroom, green | 0.06 | Wang et al. (2021) |

| ethyl octanoate (13) | pineapple and apple, brandy nuance | 32 | Qian & Reineccius (2003c) |

| methyl-2-methylbutanoate (14) | fruity, apple, green | 5 (water) | Akira et al. (1996) |

| phenylethyl acetate (15) | fresh, fruity, pear | 20 | Roger et al. (1988) |

| furaneol (16) | pineapple, strawberry | 25 | Wang et al. (2021) |

| δ-octalactone (17) | coconut | 8.5 | Wang et al. (2021) |

| indole (18) | musty | 64 (honey) | Bonini et al. (2022) |

| 2,3-diethyl-5-methylpyrazine (19) | burnt coffee, nutty, roasted | 3.74 | Taylor et al. (2015) |

| methional (20) | potato | 0.25 | Wang et al. (2021) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).