Submitted:

23 December 2025

Posted:

24 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

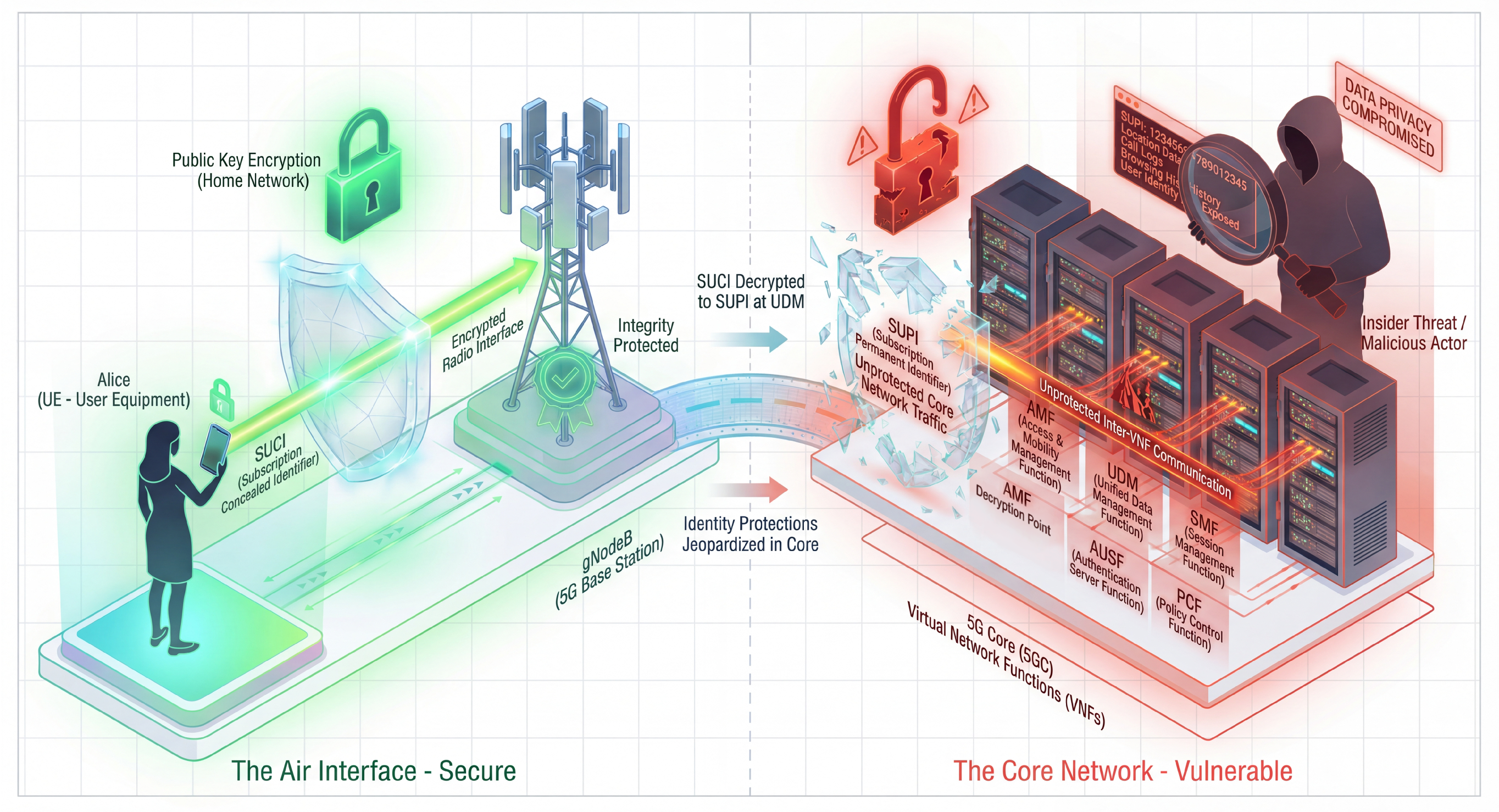

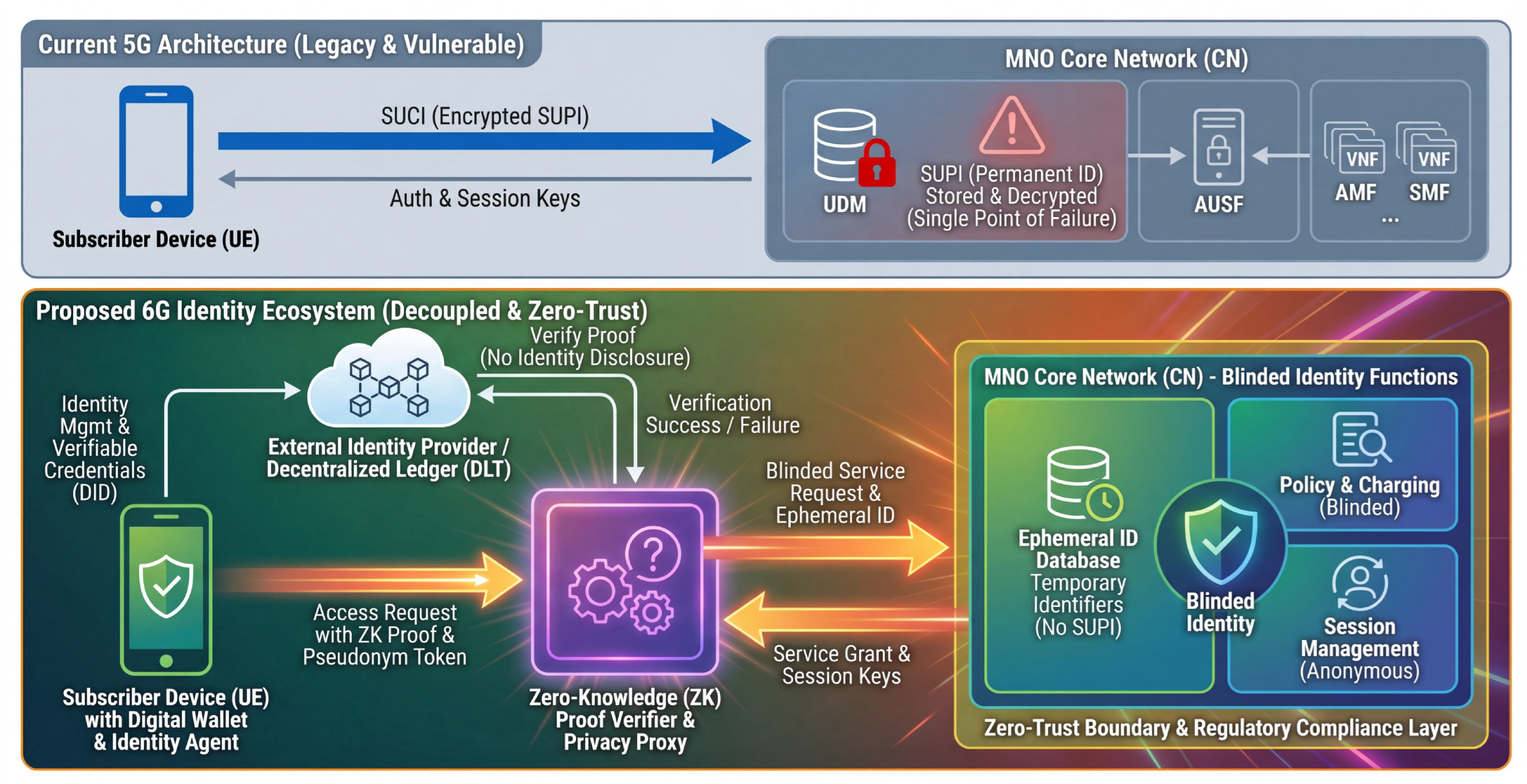

1.1. Identity Protections and Needs in 5G

2. Background

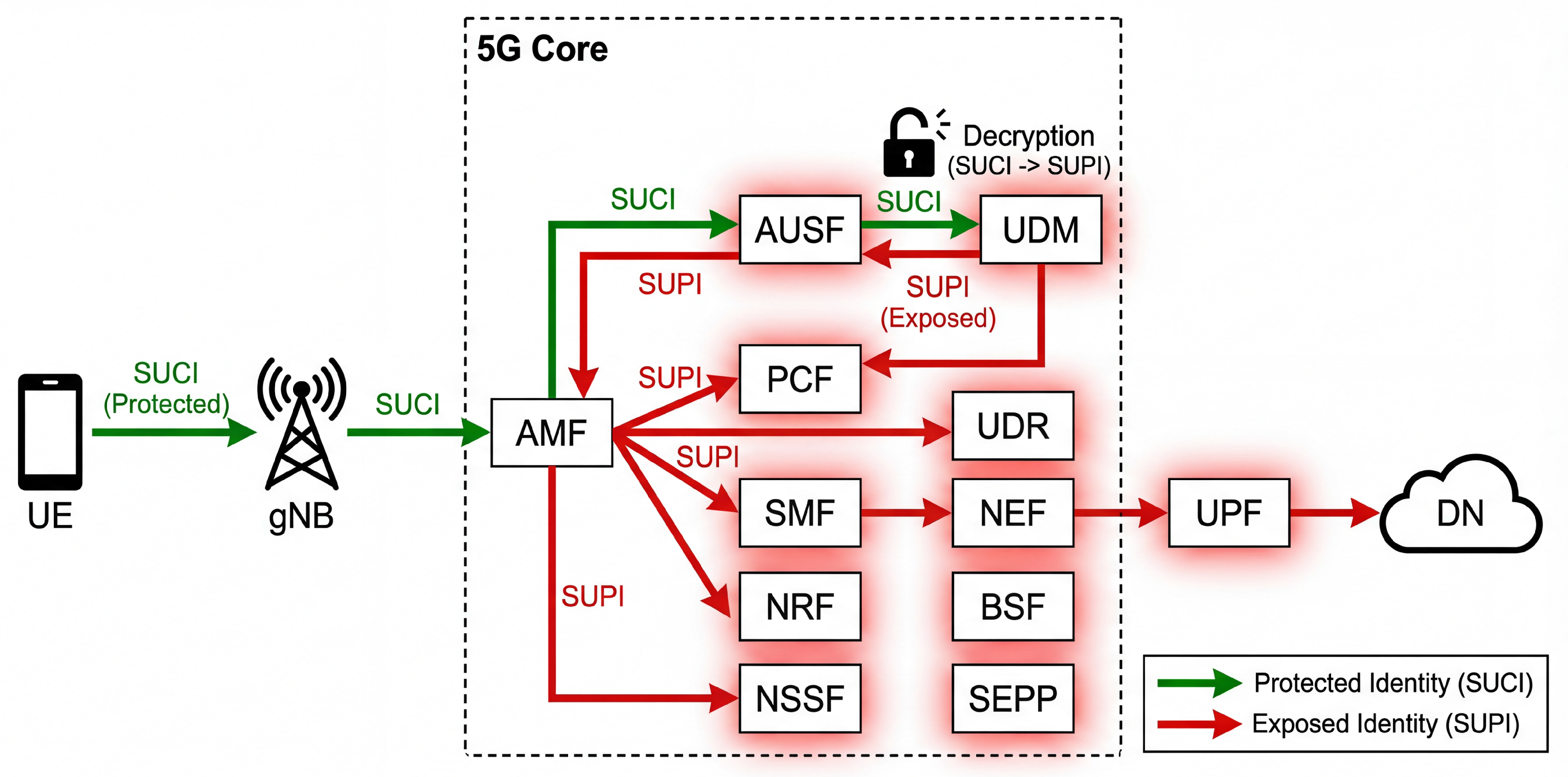

2.1. Standard 5G Authentication and Data Exposure

2.2. Insider Threats and Architectural Vulnerabilities

2.3. MNO Threat Modeling

3. Related Works

3.1. Current 5G Subscriber Identity Protection Proposals

3.2. Self-Sovereign Identity Proposals for 6G

4. The Need for Subscriber Identity Privacy in 5G/6G Core Networks

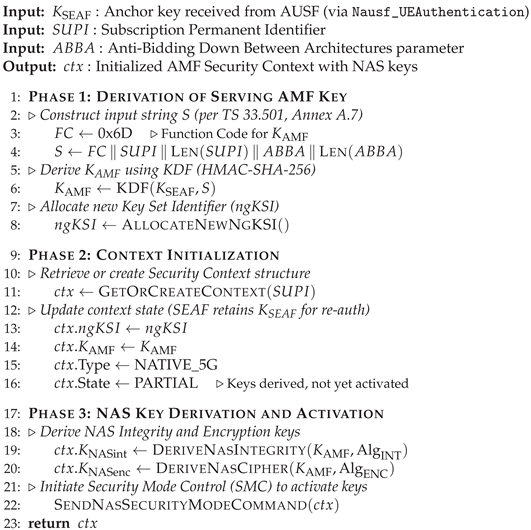

| Algorithm 1:Derivation of and Network Context Setup |

|

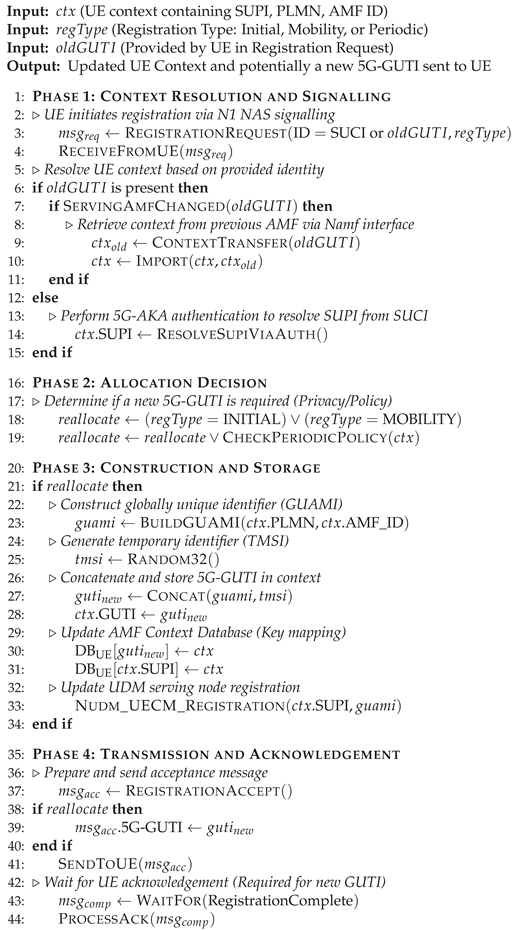

| Algorithm 2:5G-GUTI Allocation and Context Storage at AMF |

|

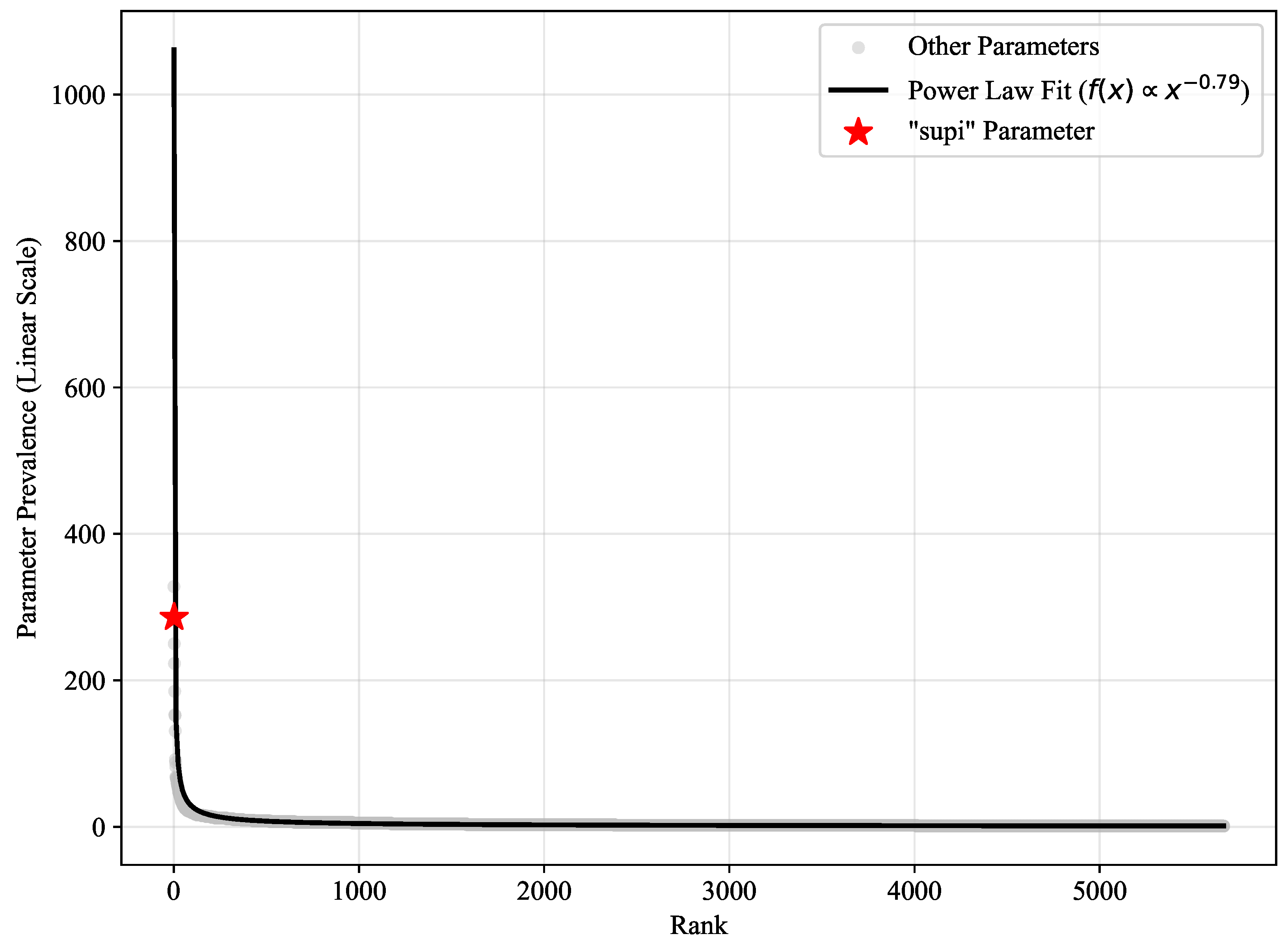

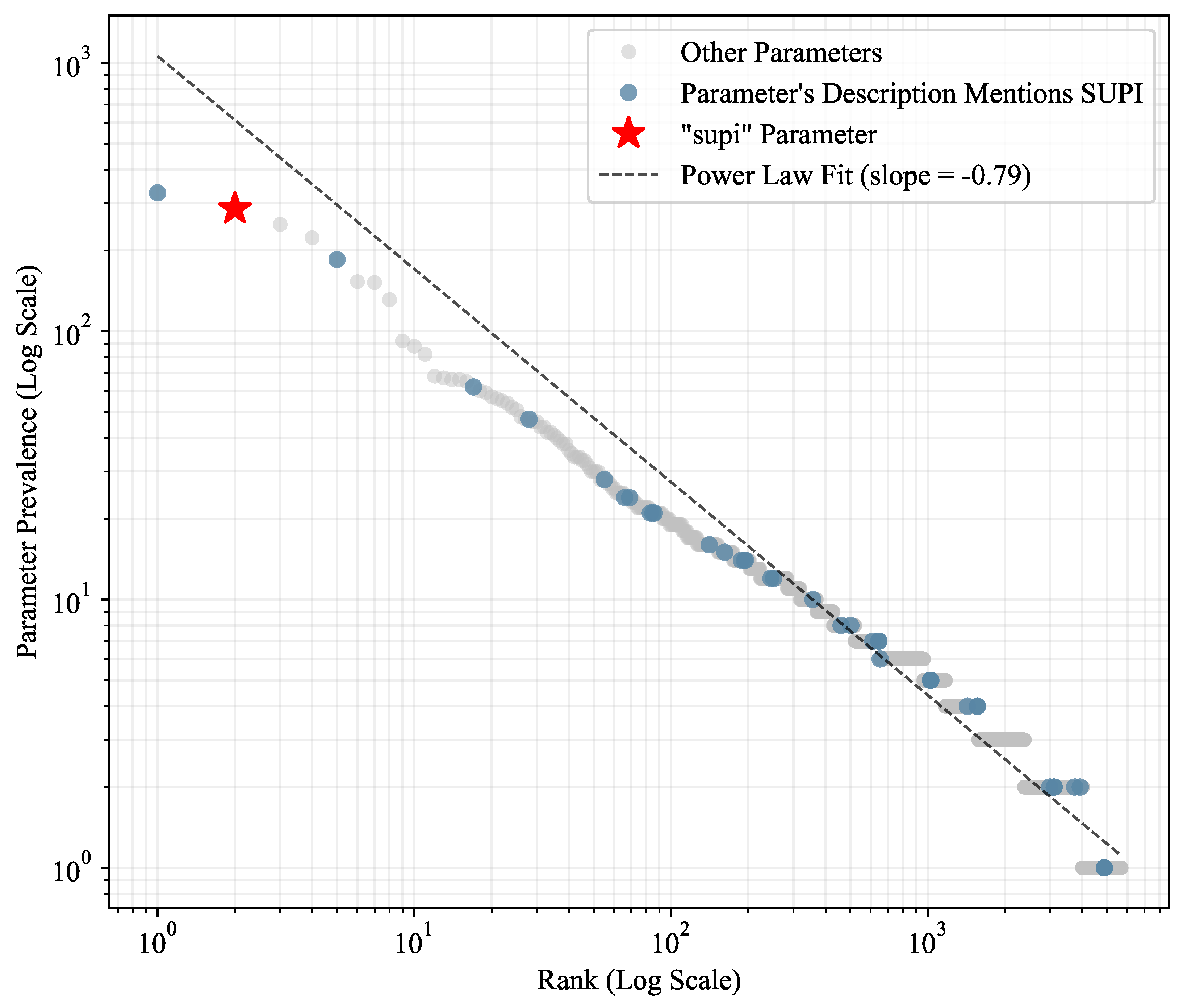

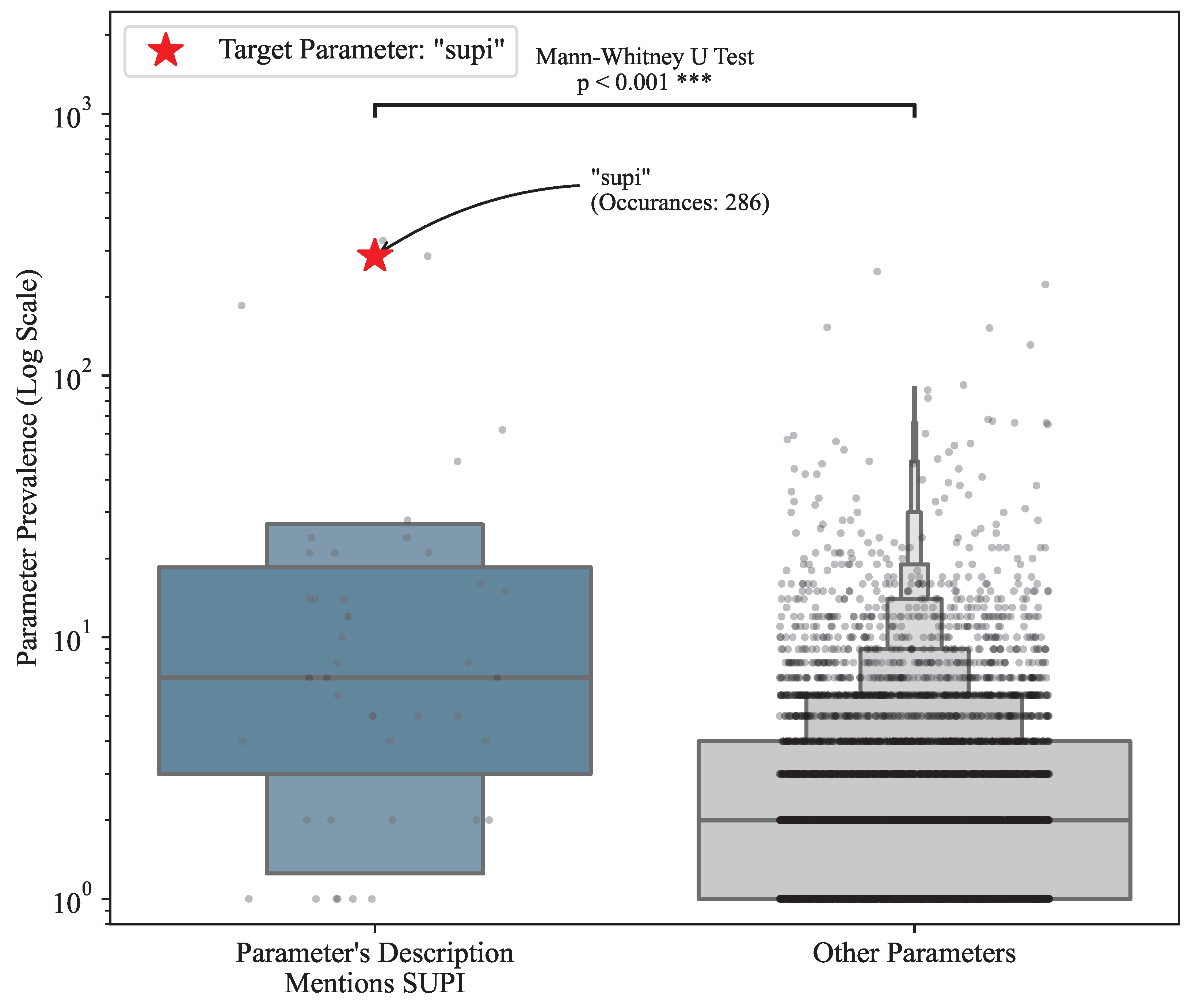

5. Analysis of 5G VNF API Parameter Prevalence and Risks

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fang, H.; Wang, X.; Xiao, Z.; Hanzo, L. Autonomous collaborative authentication with privacy preservation in 6G: From homogeneity to heterogeneity. IEEE Network 2022, 36, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, B.; Liu, J.; Wu, Y.; Kato, N. Security and privacy on 6G network edge: A survey. IEEE communications surveys & tutorials 2023, 25, 1095–1127. [Google Scholar]

- US Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency. Joint Statement by FBI and CISA on PRC Activity Targeting Telecommunications. 2024. Available online: https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/news/joint-statement-fbi-and-cisa-prc-activity-targeting-telecommunications.

- 3GPP. Security architecture and procedures for 5G System. Technical Specification (TS) 33.501, 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP). 2018. Available online: https://portal.3gpp.org/desktopmodules/Specifications/SpecificationDetails.aspx?specificationId=3169.

- Ferrag, M.A.; Maglaras, L.; Argyriou, A.; Kosmanos, D.; Janicke, H. Security for 4G and 5G cellular networks: A survey of existing authentication and privacy-preserving schemes. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2018, 101, 55–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homoliak, I.; Toffalini, F.; Guarnizo, J.; Elovici, Y.; Ochoa, M. Insight into insiders and it: A survey of insider threat taxonomies, analysis, modeling, and countermeasures. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2019, 52, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Ma, M.; Li, H.; Ma, R.; Sun, Y.; Yu, P.; Xiong, L. A survey on security aspects for 3GPP 5G networks. IEEE communications surveys & tutorials 2019, 22, 170–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potential Threat Vectors to 5G Infrastructure. In Analysis paper; Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), 2021.

- Yu, H.; Du, C.; Xiao, Y.; Keromytis, A.; Wang, C.; Gazda, R.; Hou, Y.T.; Lou, W. Aaka: An anti-tracking cellular authentication scheme leveraging anonymous credentials. In Proceedings of the Network and Distributed System Security (NDSS) Symposium 2024, 2024; Internet Society. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: ://www.fcc.gov/document/fcc-fines-largest-wireless-carriers-sharing-location-data (accessed on 08-12-2025).

- Hoffman-Andrews, J. Verizon Injecting Perma-Cookies to Track Mobile Customers, Bypassing Privacy Controls — eff.org. Available online: https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2014/11/verizon-x-uidh (accessed on 08-12-2025).

- Wiquist, W. FCC Settles Verizon "Supercookie" Probe. Available online: https://www.fcc.gov/document/fcc-settles-verizon-supercookie-probe (accessed on 08-12-2025).

- Parkin, J. Identity and security in 5G authentication. PhD thesis, Master’s thesis, University of Waterloo, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chlosta, M.; Rupprecht, D.; Pöpper, C.; Holz, T. 5G SUCI-Catchers: Still catching them all? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 14th ACM Conference on Security and Privacy in Wireless and Mobile Networks, 2021; pp. 359–364. [Google Scholar]

- rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP). Technical Report TR 33.846; Study on authentication enhancements in the 5G system (5GS). 3GPP, 2021.

- Arapinis, M.; Mancini, L.; Ritter, E.; Ryan, M.; Golde, N.; Redon, K.; Borgaonkar, R. New privacy issues in mobile telephony: fix and verification. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2012 ACM conference on Computer and communications security, 2012; pp. 205–216. [Google Scholar]

- 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP). Study on 5G security enhancement against false base stations (FBS). Technical Report TR 33.809; 3GPP. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, X.; Xie, M.; Yang, X.; Ning, J.; Qin, B.; Zhang, H.; Yu, Y. Anonymous Authentication and Key Agreement, Revisited. Cryptology ePrint Archive; 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Eleftherakis, S.; Otim, T.; Santaromita, G.; Zayas, A.D.; Giustiniano, D.; Kourtellis, N. Demystifying Privacy in 5G Stand Alone Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 30th Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking, New York, NY, USA, 2024; ACM MobiCom ’24; pp. 1330–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzon, S.R.; Yildiz, H.; Küpper, A. Decentralized identifiers and self-sovereign identity in 6g. IEEE network 2022, 36, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzon, S.R.; Yildiz, H.; Küpper, A. Towards decentralized identity management in multi-stakeholder 6G networks. In Proceedings of the 2022 1st International Conference on 6G Networking (6GNet), 2022; IEEE; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Hu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, T. A blockchain-based user-centric identity management toward 6G networks. Digital Communications and Networks; 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.Y.; Xiao, S.H.; Cao, B.; et al. Primer for Trustworthy 6G: Unified Self-Sovereign Identifier System. ZTE Technology Journal 2025, 31, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobel, D. IMSI catcher. In Chair for Communication Security, Ruhr-Universität Bochum; 2007; Volume 14. [Google Scholar]

- Scalise, P.; Hempel, M.; Sharif, H. A Survey of 5G Core Network User Identity Protections, Concerns, and Proposed Enhancements for Future 6G Technologies. Future Internet 2025, 17, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GPP. System architecture for the 5G System (5GS). Technical Specification (TS) 23.501, 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP). 2017. Available online: https://portal.3gpp.org/desktopmodules/Specifications/SpecificationDetails.aspx?specificationId=3144.

- Sharma, S. Reallocation of Temporary Identities: Applying 5G Cybersecurity and Privacy Capabilities (Draft). 2024. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/pubs/cswp/36/c/reallocation-of-temporary-identities-applying-5g-c/ipd (accessed on 11-12-2025).

- de Gregorio, J. GitHub - jdegre/5GC_APIs: RESTful APIs of main Network Functions in the 3GPP 5G Core Network. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/jdegre/5GC_APIs (accessed on 06-12-2025).

- GPP. 5G System; Technical Realization of Service Based Architecture; Stage 3. Technical Specification (TS) 29.500, 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP). 2018. Available online: https://portal.3gpp.org/desktopmodules/Specifications/SpecificationDetails.aspx?specificationId=3338.

- GPP. 5G System; Unified Data Management Services; Stage 3. Technical Specification (TS) 29.503, 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP). 2018. Available online: https://portal.3gpp.org/desktopmodules/Specifications/SpecificationDetails.aspx?specificationId=3342.

- GPP. 5G System; Session Management Services; Stage 3. Technical Specification (TS) 29.502, 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP). 2018. Available online: https://portal.3gpp.org/desktopmodules/Specifications/SpecificationDetails.aspx?specificationId=3340.

- GPP. 5G System; Session Management Policy Control Service; Stage 3. Technical Specification (TS) 29.512, 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP). 2018. Available online: https://portal.3gpp.org/desktopmodules/Specifications/SpecificationDetails.aspx?specificationId=3352.

- GPP. Telecommunication management; Charging management; 5G system, charging service; Stage 3. Technical Specification (TS) 32.291, 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP). 2018. Available online: https://portal.3gpp.org/desktopmodules/Specifications/SpecificationDetails.aspx?specificationId=3398.

- Barabási, A.L.; Bonabeau, E. Scale-free networks. Scientific american 2003, 288, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, M.E. Power laws, Pareto distributions and Zipf’s law. Contemporary physics 2005, 46, 323–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pósfai, M.; Barabási, A.L. Network science; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016; Vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

| Threat Model | Adversary Behavior & Privacy Implications |

|---|---|

| The Trusted Model | Assumes the Home Network (HN) is a benevolent custodian. Security focuses solely on attacks outside of the cellular infrastructure ecosystem. This model is considered obsolete due to the complexity of modern supply chains and the software-based nature of current 5G networks, which opens the door to third-party vendor or insider attacks [8]. |

| Honest-but-Curious (HbC) | The MNO faithfully executes network protocols (no service disruption or packet dropping) but analyzes all accessible traffic to profile users. Privacy schemes like AAKA [9] generally target this adversary, who leverages user trust to passively mine behavioral data for advertising purposes [10]. |

| Malicious-but-Cautious | An active adversary that may deviate from protocol (e.g., selling real-time location data, injecting headers) but only when the risk of detection is low. This model reflects an MNO balancing aggressive monetization against the risk of regulatory penalties or reputational damage [11,12]. |

| Coerced Model | An MNO compelled by legal jurisdiction or Lawful Interception (LI) mandates to break user privacy, or an MNO that has been attacked and these interfaces seized by adversaries. This renders user identity privacy assumptions void, regardless of the MNO’s internal integrity [3]. |

| Derived Key | Input KEY to KDF | FC | Signature | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0x6A | SNN (serving network name) | len(SNN) | SQN ⊕ AK | len(SQN ⊕ AK) | |||

| 0x6C | SNN | len(SNN) | – | – | |||

| 0x6D | SUPI | len(SUPI) | ABBA | len(ABBA) | |||

| 0x69 | type=0x01 (NAS-enc) | len(0x01) | NAS alg id (1 octet) | 0x0001 | |||

| 0x69 | type=0x02 (NAS-int) | 0x0001 | NAS alg id (1 octet) | 0x0001 | |||

| (initial) | 0x6E | UL NAS COUNT (4 octets) | 0x0004 | Access type: 0x01 (3GPP) / 0x02 (non-3GPP) | 0x0001 | ||

| NH (Next Hop) | 0x6F | SYNC-input (new or previous NH) | 0x0020 | – | – | ||

| or NH | 0x70 | Target PCI | 0x0002 | Target ARFCN-DL | len(ARFCN-DL) | ||

| or | 0x69 | type=0x03 (RRC-enc) | 0x0001 | AS alg id (1 octet) | 0x0001 | ||

| or | 0x69 | type=0x04 (RRC-int) | 0x0001 | AS alg id (1 octet) | 0x0001 | ||

| or | 0x69 | type=0x05 (UP-enc) | 0x0001 | AS alg id (1 octet) | 0x0001 | ||

| or | 0x69 | type=0x06 (UP-int) | 0x0001 | AS alg id (1 octet) | 0x0001 |

| Interaction & Standard | Resource URI | Identity Inclusion (Schema) |

|---|---|---|

| Authentication (AUSF → UDM) TS 29.503 [3] | .../nudm-ueau/v1/{supi}/security-information/generate-auth-data | URI Path Parameter |

| Registration (AMF → UDM) TS 29.503 [3] | .../nudm-uecm/v1/{supi}/registrations/amf-3gpp-access | URI Path Parameter |

| Session Creation (AMF → SMF) TS 29.502 [3] | .../nsmf-pdusession/v1/sm-contexts | JSON Body:{ "supi": "imsi-001...", ...} |

| Policy Control (SMF → PCF) TS 29.512 [3] | .../npcf-smpolicycontrol/v1/sm-policies | JSON Body:{ "supi": "imsi-001...", ...} |

| Charging & Billing (SMF → CHF) TS 32.291 [3] | .../nchf-convergedcharging/v3/chargingdata | JSON Body:{ "subscriberIdentifier": "imsi-001...", ...} |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).