1. Introduction

Industrial control systems (ICSs) are losing their clear perimeter due to the spread of the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) and the convergence of operational technology (OT) and information technology (IT)[

1]. Traditionally, ICSs were deployed in isolated networks using proprietary protocols and dedicated hardware. However, in recent years, Ethernet-based communication, standard protocols such as TCP/IP and Modbus/TCP, remote monitoring, and cloud integration have been widely adopted. Although these changes improve production efficiency and operational convenience, they also increase the number of paths through which cyberattackers can gain access to control networks[

2,

3,

4]. As a result, OT networks are no longer isolated environments, but complex cyber–physical systems interconnected with enterprise IT networks, external maintenance vendors, and remote-operation systems. Consequently, cyberattacks targeting OT/ICS environments are emerging as realistic threats, and attempts and incidents involving attacks on actual production facilities continue to be reported[

5].

OT/ICS systems are responsible for controlling physical processes and equipment in the real world. Unlike in IT environments, cyberattacks in OT/ICS can lead not only to data breaches but also to severe physical consequences such as production downtime, safety incidents, and malfunctioning equipment[

6]. For example, attacks that modify the control logic of programmable logic controllers (PLCs) or manipulate sensor and actuator signals can alter process conditions, causing equipment damage or degradation of product quality. However, there are several constraints on the application of cybersecurity measures in OT/ICS environments. Many devices are designed for long-term operation and therefore often lack modern security features, and because availability and safety are top priorities, applying patches or rebooting systems is difficult[

7]. In addition, the cost of interrupting production is extremely high, making it practically infeasible to perform active scanning or penetration tests on live systems for attack detection[

8,

9]. Due to these constraints, network-based intrusion detection systems (NIDSs) are attracting attention as a relatively feasible alternative for OT/ICS environments[

10].

OT/ICS network traffic exhibits domain-specific characteristics that depend on the configuration of processes and equipment. Each site has distinct register maps, control cycles, and communication patterns. In contrast to general IT environments, publicly available public datasets are scarce and it is difficult to collect traffic that covers various attack scenarios.

Conventional OT/ICS intrusion detection research has mainly focused on classifying normal and abnormal behavior using machine learning or deep learning models trained on features extracted from network traffic. Such approaches must often be redesigned whenever the environment changes, still require a sufficient amount of labeled data, and tend to respond primarily to numerical patterns rather than to the semantic meaning of actions. In contrast, large language models (LLMs) have shown promising applicability in various security domains beyond natural language processing, including code analysis and security log analysis[

11]. When network traffic or system logs are converted into natural language and provided as input to an LLM, it has been suggested that the model can infer “in what context and with what intent an action was taken” in a manner similar to human reasoning[

12,

13,

14]. In OT/ICS environments in particular, protocols with relatively simple request–response structures, such as Modbus/TCP, are widely used. This makes it natural to express each packet or transaction as a sentence describing which HMI or PLC accessed which register, using which function code, with what value, and under what periodic pattern.

However, to effectively train an LLM-based intrusion detection system, a sufficient amount of data is required. Publicly available OT/ICS traffic data are limited, and attack scenarios differ across industrial sites, making it difficult to construct and generalize such systems.

Therefore, this study aims to address the lack of training data for building LLM-based network intrusion detection systems in OT/ICS environments. To this end, we implement attack techniques from the MITRE ATT&CK for ICS framework in the publicly available ICSSIM simulation environment, collect normal and attack traffic, and generate synthetic attack data infused with domain knowledge using the GPT API. In addition, we fine-tune the Llama 3.1 8B Instruct model and quantitatively evaluate the detection performance of the proposed approach.

Contributions

We implement six attack scenarios based on MITRE ATT&CK for ICS in the ICSSIM simulation environment and propose a method for generating synthetic attack data that combines statistical information, the MITRE ATT&CK for ICS knowledge base, and expert domain knowledge.

We propose a method for representing network traffic as natural-language sentences for use as LLM training data and demonstrate its applicability to OT/ICS intrusion detection systems.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related work, including machine-learning- and deep-learning-based intrusion detection systems and the application of LLMs to cybersecurity. Section 3 introduces the ICSSIM-based smart-factory simulation environment and the threat model, and describes in detail the six OT/ICS attack scenarios designed on this basis. Section 4 explains the process of collecting normal and attack network traffic in the ICSSIM environment, converting it into natural language to construct an LLM training dataset, and generating GPT-based synthetic attack data by combining statistical information, MITRE ATT&CK for ICS, and domain expert knowledge. Section 5 presents the experimental setup for the proposed LLM-based intrusion detection system, including dataset partitioning, fine-tuning configurations for the Llama 3.1 8B Instruct model using QLoRA, prompt templates, evaluation metrics, and the overall experimental procedure. Section 6 quantitatively compares and analyzes the experimental results for each synthetic data composition case and for simulation-based attack data in terms of both binary classification and attack-type classification. Based on these results, Section 7 discusses the validity of the synthetic data, the strengths and limitations of LLM-based intrusion detection, and considerations for applying the approach to real OT/ICS environments. Finally, Section 8 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

Intrusion detection systems (IDSs) are generally categorized into signature-based and anomaly-based approaches. In particular, a large body of work has combined anomaly detection with machine learning or deep learning techniques [

15,

16]. Network-based IDSs typically extract various features from packets to classify traffic as normal or malicious, and ML/DL-based intrusion detection has been studied extensively across both IT and OT environments. Many studies have evaluated diverse classifiers, deep neural networks, and hybrid architectures using benchmark datasets such as KDD, NSL-KDD, and UNSW-NB15, reporting high accuracy. However, mismatches between the characteristics of these datasets and those of real-world environments have raised concerns and criticisms regarding their generalizability [

17,

18,

19]. In addition, in the OT/ICS domain, industrial protocols such as Modbus/TCP require domain-specific designs that reflect periodic communication patterns and process characteristics, and conventional models based on numerical feature vectors make it difficult to explain attack behavior in a form that is easily understandable to humans.

Recently, large language models (LLMs) have demonstrated outstanding performance not only in natural language generation and summarization but also in tasks such as code and log analysis, leading to growing interest in applying them to cybersecurity [

20,

21,

22]. LLMs have been explored as assistive tools for explaining security and log alerts in natural language and for supporting the generation of detection rules and search queries. There are also proposals in which an LLM-based agent aggregates the outputs of multiple ML-based IDSs, adapts to zero-day attacks, and provides explanations for detection results. Fernandez et al. compared classical machine learning classifiers with several open-source LLMs on IoT security logs and confirmed that LLMs can achieve superior performance in multiclass attack classification [

23]. Otoum et al. fine-tuned a lightweight LLM on an IoT-specific dataset and proposed a threat detection and prevention framework that provides real-time anomaly detection and automated response, demonstrating its scalability across diverse environments through Docker-based modular deployment [

24].

In the IT and IoT domains, ML/DL-based IDSs have been actively studied for many years [

25,

26,

27,

28], and more recently, various frameworks have been proposed that leverage LLMs to classify IoT traffic and logs, detect zero-day attacks and malware, and explain detection results [

29,

30,

31]. However, most of these studies focus on IT/IoT networks and generic protocols. To the best of our knowledge, there has been little work that converts traffic generated by industrial protocols used in OT/ICS environments, such as Modbus/TCP, into natural-language behavioral descriptions and trains and evaluates LLMs using synthetic attack data that combine MITRE ATT&CK for ICS with domain expert knowledge.

In this study, we target an OT/ICS smart-factory environment based on ICSSIM and (1) convert network traffic into natural-language descriptions that can be understood by LLMs, (2) generate synthetic attack data using the GPT API by incorporating normal traffic statistics, knowledge of MITRE ATT&CK for ICS tactics and techniques, and domain expert knowledge into prompts, and (3) fine-tune an LLM as an intrusion detection model and evaluate its performance on actual simulated attack traffic, thereby addressing this research gap.

3. Attack Scenarios

This section describes the six attack scenarios implemented in the ICSSIM-based smart-factory environment. All scenarios are built on the OT/ICS architecture of the bottle-filling plant modeled in ICSSIM and focus on network-observable behaviors of attack techniques defined in the MITRE ATT&CK for ICS framework. The attacker is assumed to be an insider who has already taken control of an HMI or PLC in the OT zone. Under this assumption, the NIDS is required to monitor HMI–PLC network traffic under internal compromise conditions and detect anomalous behavior.

3.1. ICSSIM Simulation

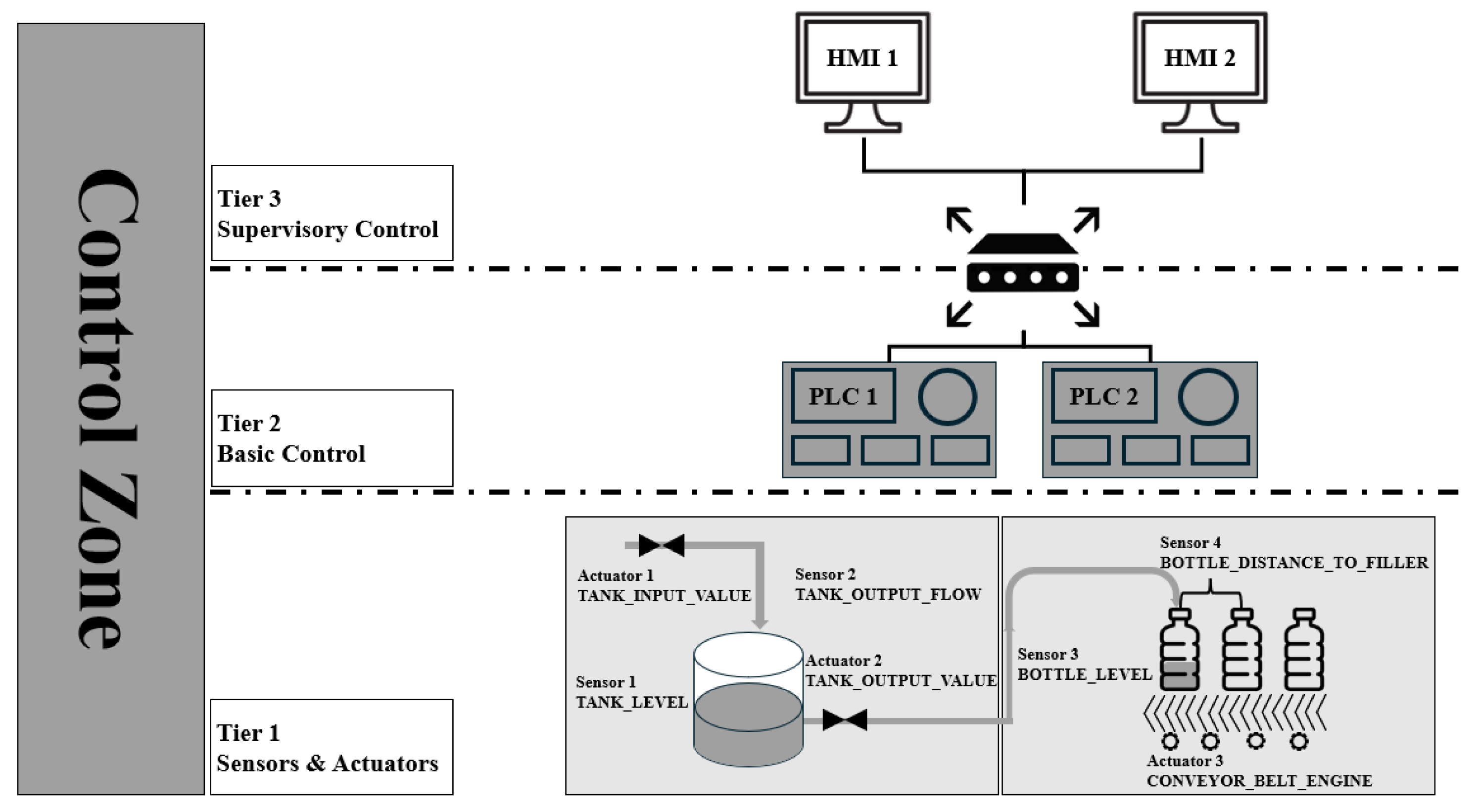

In this study, we leverage the ICSSIM simulation environment to evaluate an LLM-based intrusion detection system in OT/ICS settings. As shown in

Figure 1, ICSSIM is a framework designed to emulate realistic industrial traffic by implementing a virtual ICS composed of HMIs, PLCs, sensors, actuators, attacker nodes, and other components as containers, and by emulating the network interconnecting them [

32]. Each component runs in a separate Docker container, and a virtual switch forms the control network. This configuration enables the execution of various attack scenarios and the collection of both normal and attack traffic.

We configure a smart-factory environment consisting of HMIs, PLCs, sensors, and actuators based on the bottle-filling process provided by ICSSIM. Two PLCs are responsible for tank-level control and conveyor control, respectively, and two HMIs are assigned distinct roles: HMI1 for monitoring process status and HMI2 for issuing operational commands. Sensors measure process variables such as tank water level, flow rate, and bottle position, while actuators operate valves, pumps, and conveyor belts. Communication between HMIs and PLCs for control and monitoring is performed using the Ethernet-based Modbus/TCP protocol.

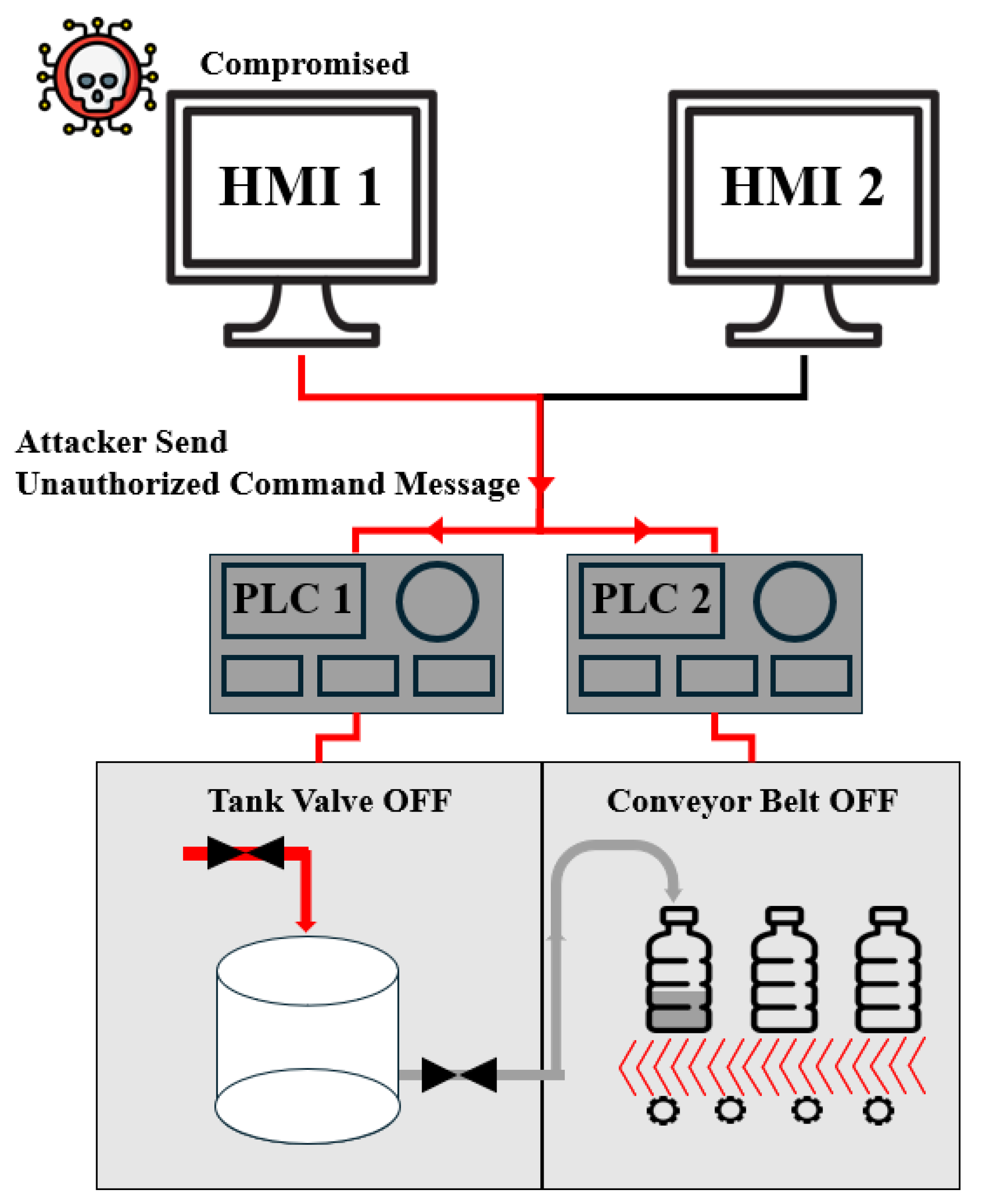

3.2. Threat Model and Design Principles

Although the ICSSIM architecture allows an attacker node to be directly connected to the control network to perform various attacks, it is rare in real industrial environments for an external attacker to obtain a dedicated node directly connected to the control network. In this study, we therefore assume a threat model in which an HMI or PLC inside the OT network has already been compromised by the attacker, for example through stolen credentials, infection of a maintenance workstation, or abuse of a remote access account. The main assumptions used to design the attack scenarios based on this threat model are summarized in

Table 1, and an example attack scenario is shown in

Figure 2.

Under these assumptions, the NIDS must detect anomalous behavior originating from internal HMIs or PLCs rather than focusing solely on the perimeter of the control network.

3.3. Remote System Discovery

The Remote System Discovery (T0846) attack involves an attacker-controlled internal device that scans the OT network to identify other control devices and collect information about their communication characteristics and service ports. In this scenario, we assume that HMI1 has been compromised by the attacker. From HMI1, the attacker performs a port scan over the internal control-network range (e.g., 192.168.0.1–255) to discover active hosts and open ports. The IP address and port ranges are divided into multiple segments that are scanned sequentially, and a sleep interval is inserted between segments so that the overall scan is carried out stealthily over an extended period. This avoids the sudden traffic spikes that occur when scanning the entire network in a short time, which can be easily detected by ICS operators or NIDSs.

During the Remote System Discovery attack, in addition to Modbus/TCP-based control traffic, TCP port-connection attempts and ARP-based host-discovery packets occur at a higher-than-normal frequency. As shown in

Figure 3, Wireshark captures repeatedly show ARP broadcasts of the form “Who has 192.168.0.x? Tell 192.168.0.21”. From a network perspective, this attack is characterized by (1) a single HMI performing port scans against multiple internal IP addresses, (2) an abnormal increase in the frequency of ARP broadcasts, and (3) repeated connection attempts to ports that are not normally used in the ICS environment. An LLM-based NIDS can be trained on natural-language descriptions of these characteristics to detect long-term, stealthy network-scanning patterns.

3.4. Unauthorized Command Message

The Unauthorized Command Message (T0855) attack forces control devices to execute commands that operators did not intend. A representative example is an unauthorized HMI issuing write commands to a PLC. In normal operation, HMI1 periodically sends read requests such as function code 3 (Read Holding Registers) to PLC1 and PLC2 for process monitoring, while HMI2 exclusively issues write commands required for process control (e.g., valve actuation, motor stop commands). In an Unauthorized Command Message attack, this separation of roles is violated. After compromising HMI1, the attacker sends write commands such as function code 16 (Write Multiple Registers) from HMI1 to the PLCs to perform unauthorized control actions such as stopping the conveyor belt or forcing pump operation.

From a network perspective, this attack is distinguishable from normal traffic in that write function codes (e.g., FC 6, 16) are observed from HMI1, which is supposed to be used only for monitoring, and these write operations are concentrated on specific registers that control the states of valves, pumps, and conveyors. By learning function-code and register-access patterns associated with each HMI role from natural-language descriptions, an LLM-based intrusion detection model can discriminate between legitimate control commands and Unauthorized Command Messages.

3.5. Modify Parameter

The Modify Parameter (T0836) attack changes parameters such as setpoints and thresholds used in control logic to abnormal values, causing the system to operate based on incorrect criteria. Although operators follow normal procedures, attacker-manipulated parameters can cause the control system to make incorrect decisions. In normal operation, setpoints and thresholds rarely change during runtime, and most Modbus/TCP write commands issued during operation are related to immediate control actions such as valve actuation, pump operation, and conveyor state changes.

In a Modify Parameter attack, we assume that HMI2, which has write privileges, has been compromised. The attacker sends write commands from HMI2 to relax configuration parameters such as upper and lower tank-level limits and flow-rate thresholds. From a network perspective, this attack uses the same HMI–PLC communication paths and the same Modbus/TCP protocol as normal traffic but differs in that transient write requests appear targeting configuration-parameter registers that are rarely modified during normal operation.

By learning natural-language descriptions that express behaviors such as sudden write requests to setpoints or thresholds during operation and changes to more permissive limits compared to normal values, an LLM-based NIDS can distinguish Modify Parameter attacks from ordinary control commands.

3.6. Remote System Information Discovery

The Remote System Information Discovery (T0888) attack collects operational information such as device vendor, product code, firmware version, and network configuration from control devices (PLCs, RTUs, HMIs, etc.) in the ICS network and later uses this information for vulnerability analysis and attack-path planning. In this scenario, we use the Modbus/TCP Read Device Identification function (function code 43/14) to gather detailed information about the control devices in the ICSSIM environment. In normal operation, HMIs primarily use function code 3 to read process status and sensor values, and requests using function code 43/14 for device identification rarely occur during runtime.

In the Remote System Information Discovery attack, we again assume that HMI1 has been compromised. HMI1 establishes Modbus/TCP sessions with each PLC and sends function code 43/14 (Read Device Identification) requests. As a result, the attacker obtains device-identification information such as vendor, product code, and firmware revision, as shown in

Figure 4.

From a network perspective, this attack uses the same HMI–PLC communication paths as normal control traffic but differs in that function code 43/14, which is rarely used during normal operation, appears repeatedly for multiple PLCs within a short period of time. By learning natural-language descriptions of such behavior, an LLM-based NIDS can recognize actions in which “an HMI queries vendor and firmware information from PLCs using the Read Device Identification function code (43/14)” as indicative of the Remote System Information Discovery stage.

3.7. Adversary-in-the-Middle (AiTM)

The Adversary-in-the-Middle (AiTM, T0830) attack places the attacker in the middle of the communication path between control devices, allowing the interception of packets, observation or modification of their contents, and retransmission. By obtaining this man-in-the-middle position, the attacker can manipulate sensor and actuator values or prepare follow-up attacks such as Spoof Reporting Message, Modify Parameter, and Unauthorized Command Message.

In this study, we implement a false data injection scenario in which Modbus/TCP traffic between HMIs and PLCs is intercepted in transit and response messages are manipulated. We assume that an HMI on the same network has been compromised by the attacker, and this HMI conducts ARP spoofing to poison the ARP tables of both the PLC and the legitimate HMI. As a result, the PLC misidentifies the attacker HMI’s MAC address as that of the legitimate HMI, and the legitimate HMI uses the attacker HMI’s MAC address instead of the PLC’s MAC address. Consequently, all Modbus/TCP packets between them are rerouted through the attacker HMI.

From this man-in-the-middle position, the attacker HMI passively monitors the traffic and selectively modifies certain register values representing process states in responses from the PLC to the HMI, then forwards the modified responses to the HMI as if they were sent by the PLC. From a network perspective, the AiTM attack exhibits the following characteristics: (1) during the ARP spoofing phase, the MAC address associated with a given IP address suddenly changes, or the attacker HMI sends a series of ARP replies to both the PLC and the legitimate HMI; and (2) during the Modbus/TCP phase, it appears that the HMI is still communicating directly with the PLC, but the actual source MAC address of response packets has changed. By learning natural-language descriptions of ARP and Modbus/TCP behavior, an LLM-based NIDS can detect such man-in-the-middle attack patterns.

3.8. Spoof Reporting Message

The Spoof Reporting Message (T0854) attack forges or tampers with the information that control devices report to upper-level HMIs or SCADA systems, thereby delivering false information that does not reflect the actual process state. The attacker’s goal is to conceal abnormal conditions or the impact of other attacks (e.g., Modify Parameter, Unauthorized Command Message) and to delay operators’ awareness of anomalies.

In this study, we implement scenarios in the ICSSIM environment in which registers representing sensor values and device states are reported to the HMI with falsified values. Spoofing is performed in two ways: (1) by modifying PLC internal logic so that state values included in response messages are manipulated, or (2) by intercepting PLC→HMI responses at an Adversary-in-the-Middle (AiTM) position, altering only the payload, and then forwarding the modified responses. In both cases, the physical behavior of field devices remains unchanged, but the HMI screens and alarm logic make decisions based solely on the manipulated reported values.

From a network perspective, Spoof Reporting Message attacks are difficult to detect because the communication peers, ports, function codes, and request intervals between HMIs and PLCs remain almost identical to those during normal operation, and only the register values in response messages are altered. Therefore, in our design, the LLM-based NIDS is trained on natural-language descriptions of inconsistencies between state values observed across different devices and paths, so that it can identify indications of Spoof Reporting Message attacks.

4. Training Data

This section describes the datasets used to train and evaluate the LLM-based intrusion detection model. We first explain how normal and attack network traffic are collected in the ICSSIM environment and how packets are preprocessed and converted into natural-language form. We then describe how normal data are constructed and how GPT-based synthetic attack data (malicious data) are generated.

4.1. Network Traffic Collection

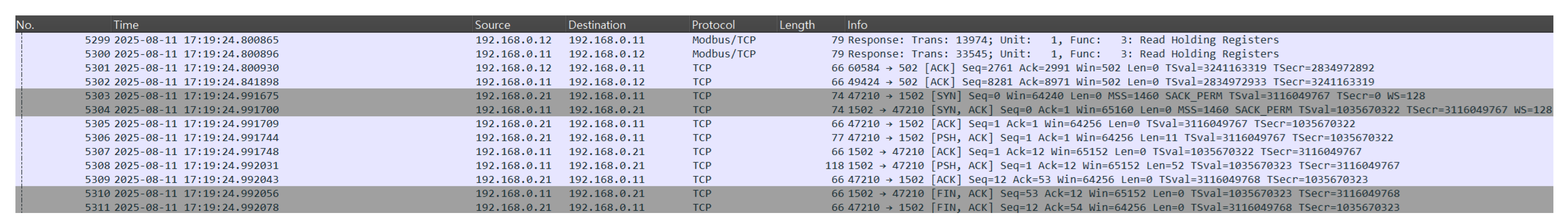

Network traffic was collected by running the ICSSIM-based OT/ICS environment described in

Section 3 in both normal-operation and attack-execution modes. For normal traffic, the system was operated for 12 hours, and all traffic between HMIs and PLCs was captured using Wireshark and stored in PCAP format.

For attack traffic, we implemented the six attack scenarios from

Section 3 in the ICSSIM environment. For each scenario, network traffic generated before, during, and after the attack was captured and stored as separate PCAP files. The collected PCAP files were then processed sequentially, and only the necessary fields were extracted from each packet and stored on a per-packet basis. As summarized in

Table 2, key fields from the IP and TCP headers and from Modbus/TCP and other protocol headers were saved in CSV format. Based on subsequent attack analysis, we selected a subset of fields from the CSV files that provide useful information for LLM training.

Because Modbus/TCP traffic is organized into request–response pairs, we matched each request with its corresponding response and constructed natural-language descriptions that combine the register-address information from the request with the register value from the response. As shown in

Table 3, each request–response pair can be represented as a sentence describing “which HMI or PLC read which register or modified which register value using which function code.”

By representing each packet (or query–response pair) as a single sentence in this way, we enable the LLM to interpret network packets as meaningful network behaviors rather than as lists of individual fields. The same format is used for attack traffic, but the attack type is not embedded directly in the sentence; instead, it is provided as a separate output label that serves as the ground truth for supervised learning during fine-tuning.

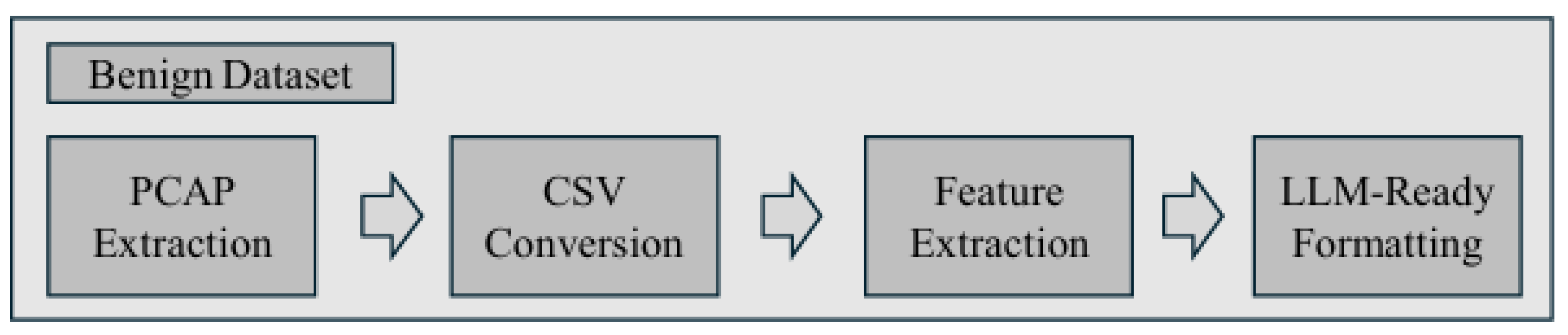

4.2. Benign Data

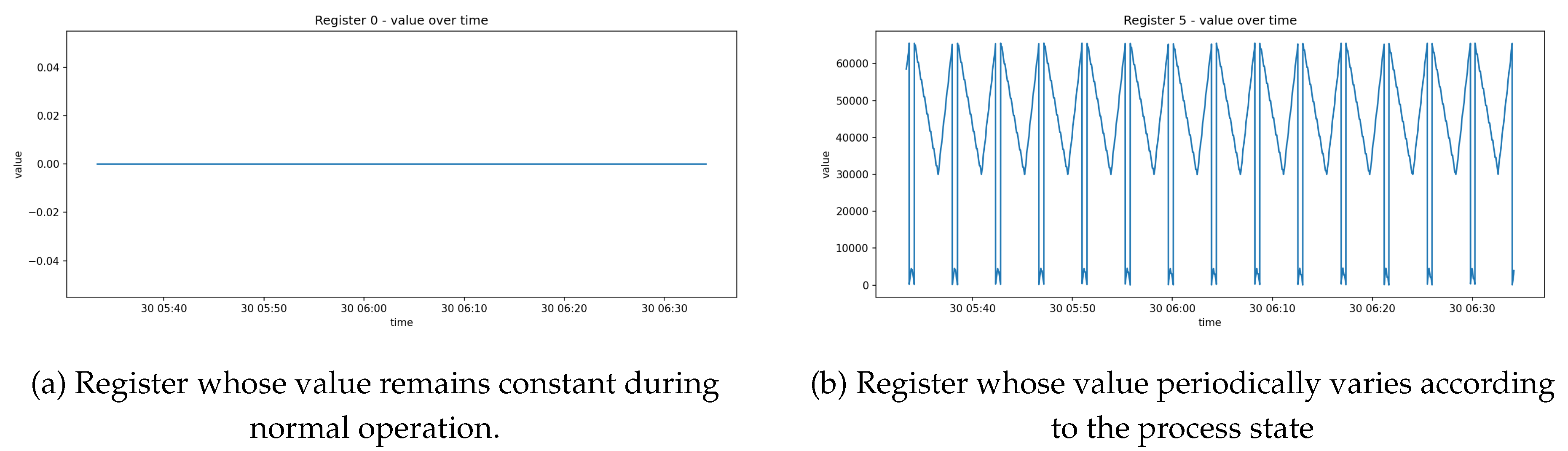

To construct the Benign dataset, we analyzed changes in register values after preprocessing the normal traffic and converting packets into natural-language form. As shown in

Figure 5, normal samples are obtained by extracting ICSSIM traffic, converting it to CSV format, and formatting it into LLM-ready sentences.

As shown in

Figure 6, some registers remain at a constant value, whereas others exhibit periodic patterns in which values repeatedly vary between a minimum and a maximum according to the process state. This reflects the characteristic behavior of OT environments, where devices operate according to fixed logic and register values form periodic patterns within specific ranges [

33].

Rather than naively expanding the amount of normal data, we selected normal samples based on the following rules:

For each register, we first include samples at the observed minimum and maximum values.

Within the range between the minimum and maximum, we randomly sample representative states of the register.

In this way, a relatively small amount of normal data can still capture the distribution of register values and the underlying process patterns, while mitigating severe class imbalance between normal and attack data that would arise from excessive expansion of normal samples. The selected normal data are then combined with the synthetic attack data described in

Section 4.3 and split into training, validation, and test datasets.

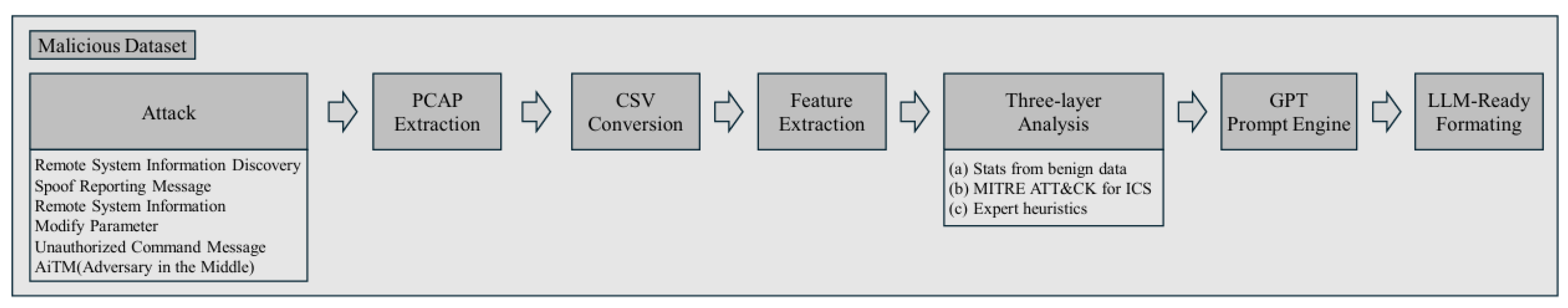

4.3. Synthetic Data (Attack Data)

In real OT/ICS environments, it is practically difficult to collect large volumes of attack traffic. The amount of attack data observed in real systems is therefore far from sufficient to design an intrusion detection system based solely on real attacks [

21,

34,

35]. As a result, when only real traffic is used, a severe class imbalance inevitably arises between normal and attack samples, and detection performance for the minority attack class can degrade.

To address this limitation, we generate synthetic data using GPT-4o based on the normal and attack traffic collected in the ICSSIM environment. The overall pipeline for generating synthetic attack data is shown in

Figure 7. In the synthetic data, the sentence itself does not include the attack type; instead, the attack type is assigned as a separate label for supervised learning.

When generating synthetic data, we provide GPT with the following three types of information:

Statistical knowledge derived from normal traffic: Using traffic collected during normal operation, we supply statistical analysis results such as the distribution of function codes, register addresses and ranges, packet lengths, and PLC–HMI communication pairs. This allows GPT to understand what types of network behaviors appear in the ICSSIM environment under normal operation.

Descriptions of tactics and techniques from MITRE ATT&CK for ICS for the six attack types: For each attack type, we include the tactics and technique descriptions defined in MITRE ATT&CK for ICS so that GPT can recognize the objectives and behavioral patterns of each attack in the ICSSIM environment.

Expert knowledge: We summarize observations obtained while actually executing each attack in the ICSSIM simulation environment, including HMI/PLC roles, changes in process flow, register access patterns, and the relationship between communication behavior and process state changes at the time of attack. This guides GPT to generate sentences that reflect how attacks would “actually manifest as network behavior” in this specific environment.

By combining these pieces of information, we construct prompts that encourage GPT to generate natural-language network-behavior descriptions that capture both normal behavior and the characteristics of each attack scenario in the ICSSIM simulation environment, rather than producing arbitrary text.

Depending on the level of information included in the prompts, we define the following three synthetic datasets:

Case 1: Synthetic data generated using only statistical knowledge derived from normal traffic.

Case 2: Synthetic data generated using both statistical knowledge and MITRE ATT&CK for ICS tactics and technique descriptions.

Case 3: Synthetic data generated using statistical knowledge, MITRE ATT&CK for ICS tactics and technique descriptions, and expert knowledge based on ICSSIM attack analysis.

The objectives and detailed configurations of each case (sizes of normal and attack datasets, training/validation/test splits, and evaluation methods) are described in Section 5.

5. Experimental Setup

This section describes the experimental setup used to evaluate the performance of the proposed smart-factory-oriented LLM-based intrusion detection system. The experiments are conducted on the ICSSIM-based smart-factory simulation environment introduced in

Section 3 and the data preprocessing and synthesis procedures presented in

Section 4. We first define the task and dataset configuration and then describe the model and fine-tuning settings, evaluation metrics, and overall experimental procedure.

5.1. Datasets

5.1.1. Task Definition

The task in this study is a seven-class multiclass classification problem, in which the LLM takes as input a natural-language description of a single network behavior and predicts whether the behavior is normal (Benign) or corresponds to one of six attack types: Unauthorized Command Message, Modify Parameter, Spoof Reporting Message, Remote System Discovery, Adversary-in-the-Middle, or Remote System Information Discovery.

Input sentences are generated through the preprocessing pipeline described in Section 4. From traffic collected in PCAP format, we extract the necessary fields, such as source and destination IP addresses, port numbers, Modbus function codes, register addresses and values, and request/response direction, and then convert them into human-readable natural-language sentences. This representation allows the LLM to interpret network behavior in the smart-factory environment not as a list of individual fields but as a semantically meaningful behavior description.

5.1.2. Data Composition and Splits

The dataset is divided into three parts: training, validation, and test. Normal data are generated by collecting HMI–PLC traffic while the ICSSIM environment operates in normal mode and then applying the preprocessing procedure described in Section 4. For each split (train/validation/test), samples are adjusted so that identical normal behaviors do not appear in multiple splits, in order to prevent the model from overfitting to specific patterns.

In the training and validation datasets, we intentionally construct an imbalanced ratio between normal and attack samples to reflect realistic network conditions. The test dataset is composed solely of real traffic collected by executing the six attack scenarios in the ICSSIM environment, and no synthetic data are included. Normal samples are extracted from normal-operation segments before and after each attack, whereas attack samples are taken from attack traffic observed during each scenario. The sizes of the training, validation, and test datasets and the ratio of normal to attack samples are summarized in

Table 4.

The number of samples per attack type in the test dataset is shown in

Table 5. The same test dataset is used across all cases so that the impact of differences in training-data composition on performance can be compared fairly.

5.2. Model and Fine-Tuning Settings

This subsection describes the base language model, QLoRA configuration, prompt template, and training hyperparameters used in the experiments. The three cases (1–3) defined in Section 4.3 differ only in their data composition; the fine-tuning settings described in this subsection are kept identical across all cases for a fair comparison.

5.2.1. Base Model and QLoRA Configuration

We use Meta’s Llama 3.1 8B Instruct model as the base language model. This instruction-tuned LLM is pre-trained to generate appropriate responses to natural-language prompts, making it suitable for the task of determining whether an input description of network behavior corresponds to an intrusion and, if so, to which attack type.

To enable efficient experimentation on a single GPU, we apply 4-bit quantization when loading the model. The weights are quantized using the NF4 4-bit format, while computations are performed in 16-bit bfloat16 precision. The tokenizer is identical to that of Llama 3.1 8B Instruct, and one special token is designated as the padding token to align sequence lengths.

Fine-tuning is performed using the QLoRA approach. The 4-bit quantized base model weights are frozen, and only low-rank adapter (LoRA) parameters are trained. The LoRA configuration is as follows:

rank

scaling

dropout

LoRA adapters are inserted into the main self-attention and feed-forward layers of Llama 3.1 by targeting the following modules:

target_module :q_proj, k_proj, v_proj, o_proj, gate_proj, up_proj, down_proj

This allows efficient domain-specific fine-tuning under constrained GPU memory without updating all model parameters.

5.2.2. Prompt Template

Fine-tuning is performed in a supervised-learning setting. Each data sample consists of a natural-language description of a single network behavior and a corresponding security analysis result (label). In the prompt, the model is explicitly instructed to act as a network security analyst for the smart-factory environment. The prompt template includes the elements summarized in

Table 6.

The model is trained to produce, for each network behavior, (1) the intrusion status (Benign/Malicious), (2) if malicious, one of the six attack types, and (3) the reasoning behind the decision. This final response format is embedded in the output field of each training example, and the prompt generation function concatenates the instruction (role, rules, environment, and examples) and the response (ground-truth answer) into a single text used as supervised fine-tuning (SFT) data.

5.2.3. Training Hyperparameters

Fine-tuning is performed using the SFTTrainer from the TRL library, with the main training hyperparameters set as follows:

Maximum sequence length: 2,048 tokens

-

Batching and optimization

- -

per_device_train_batch_size

- -

per_device_eval_batch_size

- -

gradient_accumulation_steps

- -

optimizer: AdamW (8-bit, optim="adamw_8bit")

- -

learning rate:

- -

weight decay:

- -

learning-rate schedule: constant with 50 warmup steps

-

Training steps and evaluation

- -

maximum training steps (max_steps): 700

- -

evaluation interval (eval_steps): 50

- -

checkpoint saving interval (save_steps): 700

- -

logging interval (logging_steps): 10

All three cases (1–3) use the same hyperparameters and training strategy. As described in Section 5.1, only the composition of normal and attack samples in the training and validation datasets differs. For each case, an independent model is trained and evaluated using the same metrics defined in Section 5.3.

5.3. Evaluation Metrics

For each case, the trained model is evaluated on the same test dataset (ICSSIM traffic). During evaluation, we use the same prompt structure as in training, but only the sentence describing the network behavior is provided as input, and the model’s generated response is parsed to determine the predicted class.

The response parsing rules are as follows:

If the response begins with Benign, the sample is classified as normal.

If the response begins with Malicious: and is followed by one of the six attack types, the sample is classified as the corresponding attack type.

Intrusion detection systems operate in environments with severe class imbalance, and overall accuracy alone is insufficient to assess model performance. Furthermore, because the number of samples is not perfectly balanced across normal/attack and among different attack types, overall accuracy does not fully reflect per-class performance. Therefore, we use the following metrics to evaluate the model:

From a practical intrusion detection perspective, we also analyze how effectively the model detects attacks without missing them and how often it incorrectly flags normal behavior as malicious, thereby assessing its performance in distinguishing between normal and attack traffic.

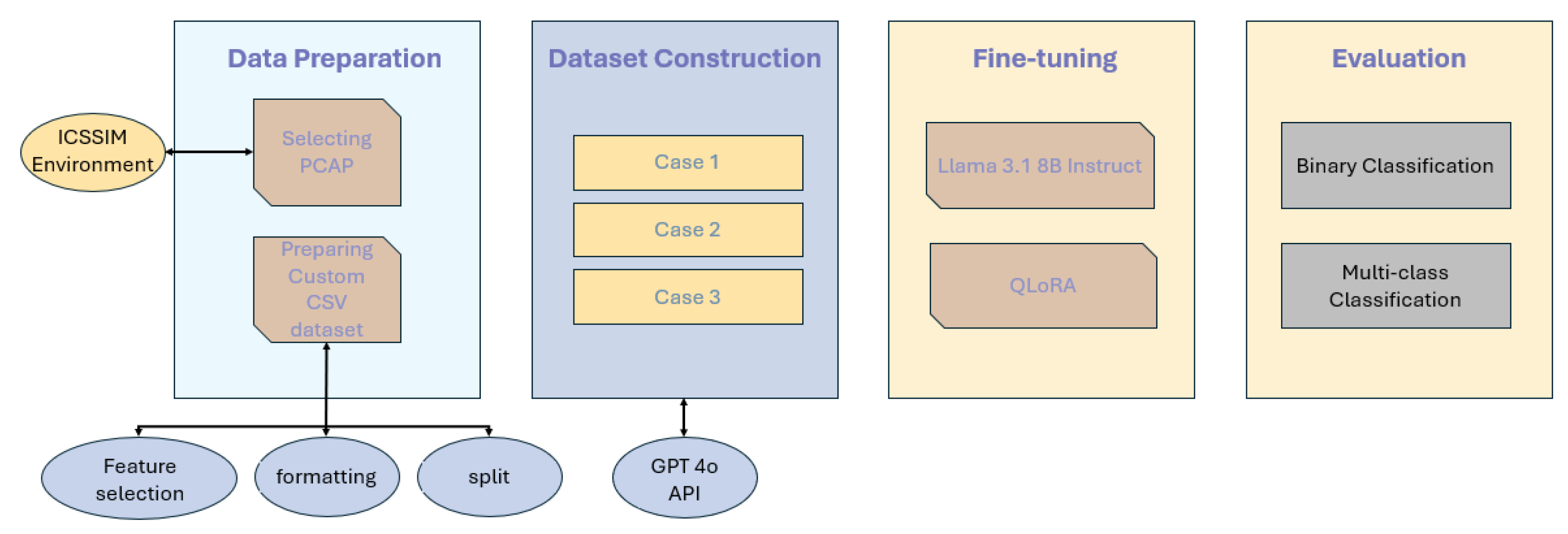

5.4. Experimental Procedure

The overall experimental procedure in this study is summarized in

Figure 8. We first execute normal operation and the six attack scenarios in the ICSSIM-based smart-factory environment and collect network traffic in PCAP format. The collected traffic is then preprocessed and converted into natural-language form according to the method described in

Section 4 to construct the dataset. The converted data are split into training, validation, and test sets, and the test dataset is composed exclusively of real traffic and shared across all cases.

For each training case, the normal-data configuration is kept fixed, while the attack data are constructed by varying the level of domain knowledge included during synthetic data generation (statistical information, MITRE knowledge, and expert knowledge). Using these datasets, we fine-tune the Llama 3.1 8B Instruct model with the QLoRA configuration.

Finally, for each case, we feed the common test dataset to the trained model and compare performance based on the metrics defined in

Section 5.3. Through this analysis, we evaluate how effectively the LLM-based intrusion detection model trained with the proposed synthetic data generation method can detect real attacks in OT/ICS environments where normal–attack imbalance is severe and attack data are difficult to obtain in sufficient quantity.

6. Experimental Results

In this section, we analyze the results of fine-tuning the Llama 3.1 8B Instruct model using the settings described in

Section 5. For the three cases defined according to the composition of synthetic data, we evaluate performance from two perspectives: (1) binary classification of normal versus attack traffic and (2) multiclass classification of the six attack types.

6.1. Binary Classification Performance

Table 7 summarizes the binary classification performance for each case when distinguishing normal versus attack traffic. Precision and recall are computed with respect to the attack class.

In Case 1 and Case 2, the attack recall is 0.500 and 0.524, respectively, meaning that only about half of the 206 attack samples are detected as attacks. However, all samples predicted as attacks are indeed attacks, resulting in a precision of 1.000 for the attack class. This behavior reflects the prompt design, which instructs the model to “make conservative decisions when evidence is insufficient,” leading the model to adopt a conservative strategy in attack detection. While no normal traffic is misclassified as attacks, missing roughly half of the actual attacks is insufficient for practical use as an intrusion detection system.

In contrast, Case 3 achieves a substantially higher overall accuracy of 99.61%, with an attack recall of 0.995, where 205 out of 206 attack samples are correctly detected as attacks, and all 52 normal samples are correctly classified as normal. This demonstrates that incorporating expert knowledge about the ICSSIM environment into the synthetic data, in addition to statistical information and MITRE knowledge, significantly improves attack detection performance even from the binary classification perspective.

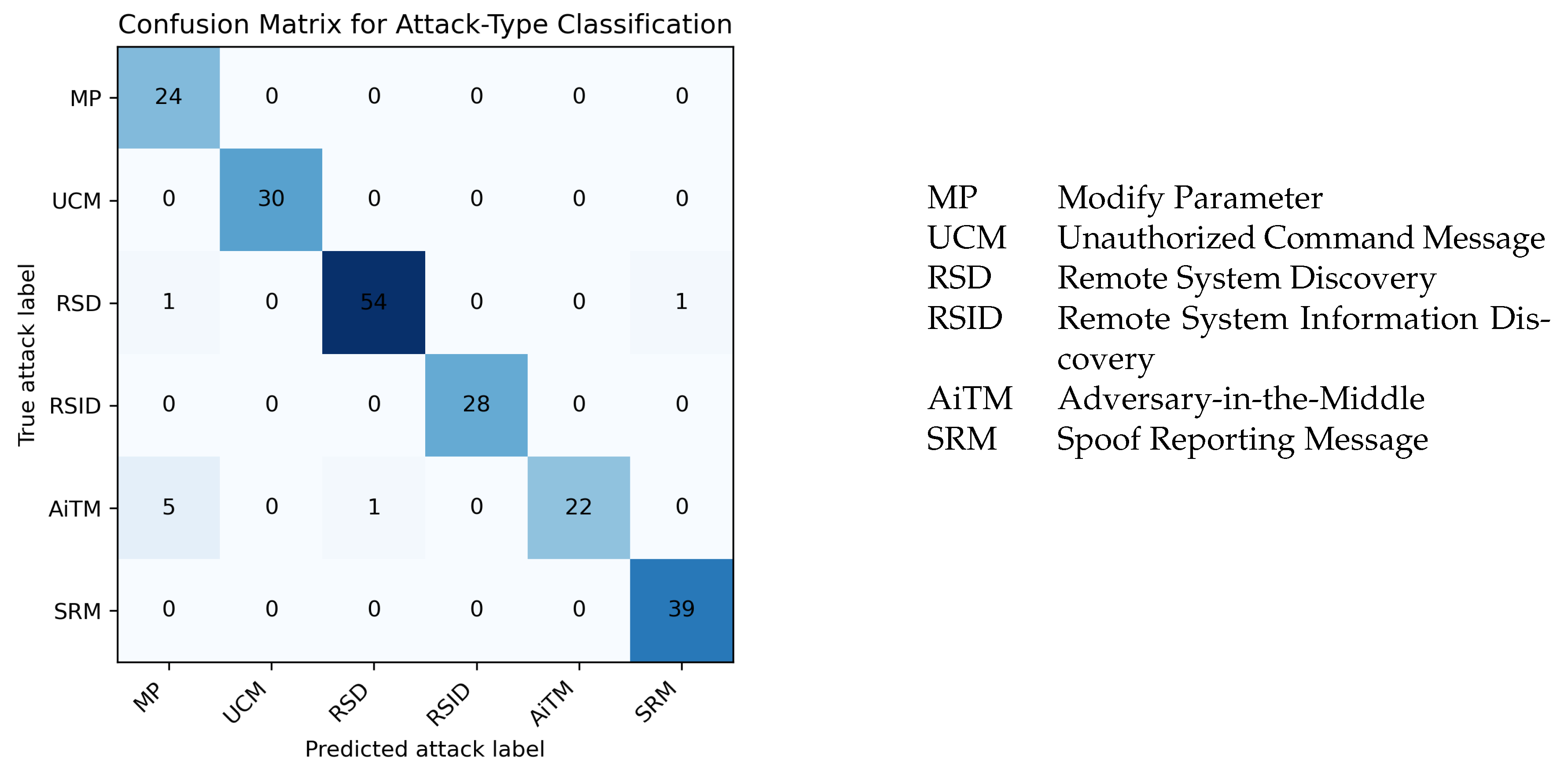

6.2. Attack-Type Classification

In this subsection, we evaluate how well the model distinguishes among the six attack types for samples labeled as attacks. Attack-type classification is performed only on the 206 samples whose true label is

Malicious. For these samples, we compute precision, recall, and F1-score for each of the six attack types. Cases where normal traffic is misclassified as a particular attack type are reflected in the binary classification metrics in

Section 6.1. The overall attack-type accuracy and macro F1-score for each case are summarized in

Table 8.

In Case 1 and Case 2, the performance in distinguishing among the six attack types is very low. The attack-type accuracy is around 0.14, which is not much better than the expected accuracy of random guessing among six classes (about 16.7%), and the macro F1-score is below 0.20. In contrast, Case 3 achieves an attack-type accuracy and macro F1-score both close to 0.95, indicating that the model can accurately classify the six attack types at a fine-grained level.

6.2.1. Per-Attack-Type Performance in Case 1

Case 1 is the setting in which synthetic attack data are generated using only statistical information derived from normal traffic, and the overall attack-type classification performance is limited, as shown in

Table 9.

Among the six types, Unauthorized Command Message achieves the relatively best performance, followed by Adversary-in-the-Middle (AiTM) with modest but non-trivial performance. This suggests that comparatively simple patterns such as device permissions (read/write) can be learned to some extent from normal-traffic statistics alone.

For the remaining four attack types, however, most samples are misclassified as Benign or as other attack types, resulting in an F1-score of 0. For example, Spoof Reporting Message involves behaviors in which register values, function codes, and device roles interact in a structured manner. Because the synthetic data in Case 1 do not sufficiently capture such structural information, the LLM fails to clearly distinguish between different attack scenarios.

6.2.2. Per-Attack-Type Performance in Case 2

Case 2 generates synthetic attack data using both normal-traffic statistical information and MITRE ATT&CK for ICS tactics and technique descriptions. Overall performance remains similar to that of Case 1, as shown in

Table 10, and the per-attack-type results are as follows.

The performance for Unauthorized Command Message improves compared to Case 1: all 30 attacks of this type are detected while maintaining a reasonable precision. This suggests that MITRE descriptions related to “unauthorized control commands” or “policy-violating actions” are reflected in the synthetic data, enabling more stable detection of this particular type.

However, the model also tends to over-rely on Unauthorized Command Message, misclassifying some samples of other attack types as this category. For the remaining attack types, the model still fails to provide meaningful discrimination, similar to Case 1. This indicates that while MITRE descriptions help the model conceptually understand attack tactics and techniques, they do not fully specify environment-specific details such as protocol fields, addressing schemes, and device-role relationships in a particular OT/ICS setting. As a result, the synthetic data may be biased toward certain attack patterns.

6.2.3. Per-Attack-Type Analysis in Case 3

Case 3 combines statistical information, MITRE ATT&CK knowledge, and expert knowledge obtained from executing attacks in the ICSSIM environment, leading to a significant improvement in attack-type classification performance, as shown in

Table 11. A detailed breakdown by attack type is shown in

Figure 9.

For Modify Parameter, the model correctly detects all 24 attacks but misclassifies 6 samples of other types as Modify Parameter. This can be interpreted as a result of domain knowledge such as “setpoints and thresholds are changed via write requests to specific registers” being sufficiently reflected in the synthetic data, enabling the model to distinguish between ordinary control writes and parameter-modification attacks.

Unauthorized Command Message is detected perfectly, with all 30 attacks correctly identified and no false positives, stabilizing the already high performance observed in Case 2. Remote System Discovery correctly detects 54 out of 56 attacks, and Remote System Information Discovery correctly detects all 28 attacks, showing that information-gathering behaviors such as port scanning, probing, and device identification are well captured in the synthetic data.

For Adversary-in-the-Middle (AiTM), the model detects 22 out of 29 attacks, missing 7. AiTM attacks must be distinguished based on session-level characteristics such as sequence ordering, latency, and path asymmetry rather than on individual packet features. However, because the sentence-level textual representation and synthetic data used in this work do not fully capture such long-term dependencies, the model reliably detects samples with clear patterns but fails to consistently distinguish shorter or weaker patterns from ordinary TCP communication.

Finally, for Spoof Reporting Message, the model correctly detects 39 attacks and misclassifies only 1 sample. Synthetic data for this attack type were generated such that PLCs report sensor values to HMIs with register-level patterns that differ clearly from normal traffic, enabling the model to reliably discriminate these spoofed reports.

Overall, Case 1 captures only simple policy-violation patterns and fails to distinguish most attack types, whereas Case 2 achieves partial improvement only for Unauthorized Command Message. In contrast, Case 3 achieves high precision and recall across all six attack types. This confirms that when synthetic data generation incorporates not only statistical information and MITRE knowledge but also expert knowledge reflecting real system behavior, an LLM-based intrusion detection system can perform reliable attack-type classification.

7. Discussion and Limitations

This study evaluates the feasibility of applying an LLM-based intrusion detection system in OT/ICS environments by alleviating the scarcity of real attack data and class imbalance through carefully designed synthetic data. As shown in the results of

Section 6, the mere use of synthetic data is not sufficient; the level and fidelity of domain knowledge incorporated into the synthesis process emerge as key factors determining performance.

First, the results of Case 1 and Case 2 align with existing criticisms that “models trained solely on synthetic data are difficult to deploy in real environments.” In Case 1, where synthetic attack data are generated using only normal-traffic statistics, the model detects only about half of the actual attacks in binary classification and achieves near-random performance in attack-type classification. Case 2, which additionally incorporates MITRE ATT&CK for ICS knowledge, still falls short of practical use as a detector, except for Unauthorized Command Message.

This indicates that OT/ICS network attack patterns cannot be fully captured by simple statistical anomalies or abstract attack descriptions alone. In particular, when environment-specific information such as register addresses, values, ranges, and device-role relationships is insufficient, the LLM lacks decisive cues to distinguish attacks from normal behavior.

In contrast, Case 3 shows that when synthetic data incorporate (1) statistical information derived from normal traffic, (2) tactics and technique descriptions from MITRE ATT&CK for ICS, and (3) expert knowledge obtained from actually executing attacks in the ICSSIM environment, an LLM-based intrusion detection system can achieve practically usable performance in both binary and attack-type classification. When synthetic data explicitly encode which function-code–and-register combinations characterize each attack, which HMIs and PLCs exchange requests and responses, and how the communication flow differs from normal behavior, the model can reliably classify the six attack types. This suggests that the core issue is not “synthetic data” per se but rather synthetic data that lack sufficient domain knowledge.

Traditional OT/ICS intrusion detection studies have mainly converted packet fields and statistical characteristics into numerical feature vectors and fed them into ML/DL models. In contrast, this work describes source/destination IPs and ports, Modbus/TCP function codes, and register ranges as natural-language sentences and trains the LLM to respond in the form “Benign” or “Malicious: <Attack type>, Reason: <…>.” As a result, in actual outputs, the model can generate explanations such as “This is classified as Unauthorized Command Message because monitoring-only HMI1 used a write function code to modify control registers.” Such explanations can help OT/ICS operators intuitively understand why a packet (or behavior) is classified as an attack and thus contribute to the development of explainable ICS intrusion detection systems.

From the perspective of data imbalance, this study also suggests that “systematic design of synthetic data based on limited real normal and attack samples may be more effective than indiscriminately collecting large amounts of data.” In real OT/ICS environments, systems often operate continuously for long periods, and attack occurrences are extremely rare compared to normal behavior. There are practical limitations to increasing the amount of attack data by exposing real systems to risk or forcefully staging numerous attack scenarios.

Our approach combining statistical information from normal operation, public knowledge frameworks such as MITRE ATT&CK, and domain-expert analysis in LLM prompts to generate synthetic data based on a relatively small set of real normal and attack samples demonstrates that it is possible to achieve meaningful detection performance for real attacks. This suggests a realistic alternative for environments where attack data are inherently scarce.

However, this study has the following limitations:

Limited process domain: The experimental environment is restricted to a bottle-filling process modeled in ICSSIM. Additional validation is required to generalize the approach to other industrial processes such as power, gas, and water treatment.

Limited attack coverage: The attack scenarios focus on six techniques from MITRE ATT&CK for ICS. Future work should explore a broader range of tactics and technique combinations.

Transaction-level text representation: The textual representation focuses on individual transactions, which limits performance for attacks such as AiTM that must be understood at the session or sequence level.

Despite these limitations, this study is meaningful in that it demonstrates the practical potential of LLM-based intrusion detection systems in OT/ICS environments by leveraging domain-knowledge-infused synthetic data and natural-language representations of network behavior.

8. Conclusions

This study proposes and evaluates a method that uses synthetic data to mitigate the scarcity of real attack data and class imbalance in LLM-based intrusion detection systems for smart-factory environments. Using the ICSSIM simulator, we construct an OT/ICS network environment consisting of HMIs, PLCs, sensors, and actuators, implement six attack scenarios, capture the resulting traffic, and convert it into natural-language form suitable for LLM training and evaluation.

In particular, we combine statistical information from normal traffic, knowledge from MITRE ATT&CK for ICS, and domain expert knowledge to generate synthetic attack data via the GPT API and fine-tune the Llama 3.1 8B Instruct model using QLoRA. The results show that synthetic data generated using only statistical information (Case 1) or statistical information plus MITRE knowledge (Case 2) yield insufficient performance in both binary and attack-type classification for practical deployment as an intrusion detection system.

In contrast, Case 3, which uses synthetic data incorporating statistical information, MITRE knowledge, and expert knowledge, achieves a binary classification accuracy of 99.61%, an attack-type classification accuracy of 95.63%, and a macro F1-score of 0.952. This demonstrates that the key factor determining LLM-based intrusion detection performance is not simply whether synthetic data are used but the level and quality of domain knowledge injected into the synthesis process.

Furthermore, by expressing network traffic as natural-language descriptions and training the LLM to output not only the intrusion status and attack type but also the reasoning behind its decisions, we show that explainable ICS intrusion detection is feasible beyond mere alert generation. This can help OT/ICS operators more easily interpret the meaning of alerts and prioritize incident response.

Overall, this study (1) shows that synthetic data combining statistical information, public knowledge frameworks, and domain-expert analysis can be a realistic alternative to address the scarcity of real attack data in OT/ICS environments; (2) demonstrates that domain-knowledge-infused natural-language representations of network behavior enable LLMs to serve as smart-factory-oriented intrusion detection models; and (3) suggests the feasibility of explainable ICS intrusion detection systems.

Future work includes extending the approach to other industrial domains and protocols (e.g., DNP3, BACnet), developing textual representations that capture session- and sequence-level information, and exploring diverse LLM architectures and multi-agent combinations to further broaden the applicability and reliability of LLM-based intrusion detection in OT/ICS environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A. and H.K.; data curation, S.A. and S.P.; funding acquisition, S.-J.C.; investigation,H.C. and J.K.; methodology, S.A. and S. P.; project administration, H.K. and S.-J.C.; resources, S.A. and S.-J.C.; software, S.A. and S. P.; supervision, H.K. and S.-J.C.; validation, H.K. and H.C.; visualization,S.A.; writing—original draft, S.A.; writing—review and editing, H.K. and S.-J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the MSIT (Ministry of Science and ICT), Korea, under the ICAN (ICT Challenge and Advanced Network of HRD) support program (IITP-2023-00259867) supervised by the IITP (Institute for Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation). This work was also supported by the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP) and the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE) of the Republic of Korea (No. RS-2021-KP002461).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available because the experiments are part of an ongoing research project. The dataset may be made available from the corresponding author on reasonable request after the completion of the project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Patera, L.; Garbugli, A.; Bujari, A.; Scotece, D.; Corradi, A. A layered middleware for ot/it convergence to empower industry 5.0 applications. Sensors 2021, 22, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhirani, L.L.; Armstrong, E.; Newe, T. Industrial IoT, cyber threats, and standards landscape: Evaluation and roadmap. Sensors 2021, 21, 3901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopstein, A.; Nguyen, C.; O’Fallon, C.; Hastings, N.; Wollman, D.A. NIST Framework and Roadmap for Smart Grid Interoperability Standards, Release 4.0. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eden, P.; Blyth, A.; Jones, K.; Soulsby, H.; Burnap, P.; Cherdantseva, Y.; Stoddart, K. SCADA System Forensic Analysis Within IIoT. In Cybersecurity for Industry 4.0: Analysis for Design and Manufacturing; Thames, L., Schaefer, D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; pp. 73–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machaka, V.; Figueroa-Lorenzo, S.; Arrizabalaga, S.; Elduayen-Echave, B.; Hernantes, J. Assessing the impact of Modbus/TCP protocol attacks on critical infrastructure: WWTP case study. Computers and Electrical Engineering 2025, 126, 110485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nankya, M.; Chataut, R.; Akl, R. Securing industrial control systems: Components, cyber threats, and machine learning-driven defense strategies. Sensors 2023, 23, 8840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koay, A.M.; Ko, R.K.L.; Hettema, H.; Radke, K. Machine learning in industrial control system (ICS) security: current landscape, opportunities and challenges. Journal of Intelligent Information Systems 2023, 60, 377–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stouffer, K.A.; Pease, M.; Tang, C.; Zimmerman, T.; Pillitteri, V.Y.; Lightman, S.; Hahn, A.; Saravia, S.; Sherule, A.; Thompson, M. Guide to Operational Technology (OT) Security. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrocki, M.; Schmidt, T.C.; Wählisch, M. Uncovering vulnerable industrial control systems from the internet core. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1901.04411. [Google Scholar]

- Cheminod, M.; Durante, L.; Valenzano, A. Review of security issues in industrial networks. IEEE transactions on industrial informatics 2012, 9, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, N.; Kaiser, F.K.; Giladi, S.; Sharabi, S.; Moyal, R.; Shpolyansky, S.; Murillo, A.; Elyashar, A.; Puzis, R. Labeling network intrusion detection system (NIDS) rules with MITRE ATT&CK techniques: Machine learning vs. large language models. Big Data and Cognitive Computing 2025, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, X.; Xu, J.; Li, J.; Xie, D.; Long, W.; Ngai, E.C. Large language models for network intrusion detection systems: Foundations, implementations, and future directions. arXiv arXiv:2507.04752. [CrossRef]

- Cui, T.; Lin, X.; Li, S.; Chen, M.; Yin, Q.; Li, Q.; Xu, K. Trafficllm: Enhancing large language models for network traffic analysis with generic traffic representation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.04222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhafsi, A.; Sinha, R.; Agia, C.; Schmerling, E.; Nesnas, I.A.; Pavone, M. Semantic anomaly detection with large language models. Autonomous Robots 2023, 47, 1035–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, S.; Khan, S.; Parkinson, S. LLM-based event log analysis techniques: A survey. arXiv arXiv:2502.00677. [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Huang, S.; Luan, Z.; Yang, S.; Fung, C.; Yang, H.; Qian, D.; Shang, J.; Xiao, Z.; Wu, Z. Loggpt: Exploring chatgpt for log-based anomaly detection. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on High Performance Computing & Communications, Data Science & Systems, Smart City & Dependability in Sensor, Cloud & Big Data Systems & Application (HPCC/DSS/SmartCity/DependSys), 2023; IEEE; pp. 273–280. [Google Scholar]

- Alnasser, O.; Al Muhtadi, J.; Saleem, K.; Shrestha, S. Signature and anomaly based intrusion detection system for secure IoTs and V2G communication. ALEXANDRIA ENGINEERING JOURNAL 2025, 125, 424–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, U.; Nazir, M.; Sarwar, A.; Ali, T.; Aggoune, E.H.M.; Shahzad, T.; Khan, M.A. Signature-based intrusion detection using machine learning and deep learning approaches empowered with fuzzy clustering. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldschmidt, P.; Chudá, D. Network intrusion datasets: A survey, limitations, and recommendations. Computers & Security 2025, 156, 104510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flood, R.; Engelen, G.; Aspinall, D.; Desmet, L. Bad design smells in benchmark nids datasets. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 9th European Symposium on Security and Privacy (EuroS&P), 2024; IEEE; pp. 658–675. [Google Scholar]

- Dehlaghi-Ghadim, A.; Moghadam, M.H.; Balador, A.; Hansson, H. Anomaly detection dataset for industrial control systems. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 107982–107996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, S.; Khan, S.; Parkinson, S. LLM-based event log analysis techniques: A survey. arXiv;arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.00677. [Google Scholar]

- Houssel, P.R.; Singh, P.; Layeghy, S.; Portmann, M. Towards explainable network intrusion detection using large language models. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Big Data Computing, Applications and Technologies (BDCAT), 2024; IEEE; pp. 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Tejero-Fernández, J.J.; Sánchez-Macián, A. Evaluating Language Models For Threat Detection in IoT Security Logs. arXiv arXiv:2507.02390. [CrossRef]

- Otoum, Y.; Asad, A.; Nayak, A. Llm-based threat detection and prevention framework for iot ecosystems. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.00240. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Wang, S.; Gao, J.; Qiu, T.; Wang, Z.; Wan, H.; Zhao, X. Deep Learning-based Intrusion Detection Systems: A Survey. arXiv arXiv:2504.07839. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Fang, W.; Zhu, C.; Song, G.; Zhang, W. Toward Deep Learning based Intrusion Detection System: A Survey. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 6th International Conference on Big Data Engineering, 2024; pp. 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hozouri, A.; Mirzaei, A.; Effatparvar, M. A comprehensive survey on intrusion detection systems with advances in machine learning, deep learning and emerging cybersecurity challenges. Discover Artificial Intelligence 2025, 5, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrag, M.A.; Ndhlovu, M.; Tihanyi, N.; Cordeiro, L.C.; Debbah, M.; Lestable, T. Revolutionizing cyber threat detection with large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.14263, 195–202. [Google Scholar]

- Tejero-Fernández, J.J.; Sánchez-Macián, A. Evaluating Language Models For Threat Detection in IoT Security Logs. arXiv arXiv:2507.02390. [CrossRef]

- Alsuwaiket, M.A. ZeroDay-LLM: A Large Language Model Framework for Zero-Day Threat Detection in Cybersecurity. Information 2025, 16, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehlaghi-Ghadim, A.; Balador, A.; Moghadam, M.H.; Hansson, H.; Conti, M. ICSSIM—a framework for building industrial control systems security testbeds. Computers in Industry 2023, 148, 103906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, R.R.R.; Sadre, R.; Pras, A. Exploiting traffic periodicity in industrial control networks. International journal of critical infrastructure protection 2016, 13, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, X. Enhanced Intrusion Detection for ICS Using MS1DCNN and Transformer to Tackle Data Imbalance. Sensors 2024, 24, 7883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javeed, D.; Saeed, M.S.; Ahmad, I.; Kumar, P.; Jolfaei, A.; Tahir, M. An intelligent intrusion detection system for smart consumer electronics network. IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics 2023, 69, 906–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Architecture of the ICSSIM environment.

Figure 1.

Architecture of the ICSSIM environment.

Figure 2.

Unauthorized Command Message attack scenario example.

Figure 2.

Unauthorized Command Message attack scenario example.

Figure 3.

Wireshark capture of network-scanning traffic during the Remote System Discovery attack.

Figure 3.

Wireshark capture of network-scanning traffic during the Remote System Discovery attack.

Figure 4.

Wireshark capture of network-scanning traffic during the Remote System Discovery attack.

Figure 4.

Wireshark capture of network-scanning traffic during the Remote System Discovery attack.

Figure 5.

Pipeline for constructing the benign dataset from ICSSIM traffic.

Figure 5.

Pipeline for constructing the benign dataset from ICSSIM traffic.

Figure 6.

Examples of register-value patterns observed in normal ICSSIM operation.

Figure 6.

Examples of register-value patterns observed in normal ICSSIM operation.

Figure 7.

Pipeline for generating GPT-based synthetic attack data from ICSSIM traffic.

Figure 7.

Pipeline for generating GPT-based synthetic attack data from ICSSIM traffic.

Figure 8.

Overall experimental procedure for training and evaluating the LLM-based intrusion detection model.

Figure 8.

Overall experimental procedure for training and evaluating the LLM-based intrusion detection model.

Figure 9.

Confusion matrix of attack-type classification results for Case 3.

Figure 9.

Confusion matrix of attack-type classification results for Case 3.

| MP |

Modify Parameter |

| UCM |

Unauthorized Command Message |

| RSD |

Remote System Discovery |

| RSID |

Remote System Information Discovery |

| AiTM |

Adversary-in-the-Middle |

| SRM |

Spoof Reporting Message |

Table 1.

Main assumptions for designing attack scenarios.

Table 1.

Main assumptions for designing attack scenarios.

| Item |

Description |

| Compromise point |

An HMI or PLC inside the OT network is already in a compromised state. |

| Attacker location |

Inside the control network (no separate external attacker node). |

| Attacker privileges |

From the compromised HMI/PLC, the attacker can execute system commands and abuse existing Modbus/TCP channels between HMIs and PLCs. |

| Attack target |

PLC register values, control commands, etc. |

| Constraints |

We focus on attacks whose behavior can be observed at the network level. |

| Observation point |

Modbus/TCP and other protocols between HMIs and PLCs observed at a mirror port on the control switch. |

| Detection cues |

Function code changes, register value modifications, scanning behavior, etc. |

Table 2.

Example CSV columns and values extracted from pcap file.

Table 2.

Example CSV columns and values extracted from pcap file.

| Column name |

Description |

Example |

| src_ip |

Source IP address |

192.168.0.11 |

| src_port |

Source TCP port |

502 |

| dst_ip |

Destination IP address |

192.168.0.12 |

| dst_port |

Destination TCP port |

34048 |

| protocol |

Protocol name |

Modbus/TCP, TCP |

| direction |

Packet direction with respect to Modbus/TCP |

Query |

| frame_len |

Total frame length including L2 header |

78 |

| tcp_flags |

TCP flag string |

PSH, ACK |

| trans_id |

Modbus transaction ID (request/response matching) |

13795 |

| func_code |

Function code (e.g., 3, 6, 16) |

3 (Read Holding Register) |

| register_start |

First register address |

4 |

| register_count |

Number of consecutive registers |

2 |

| register_value |

List of register values |

2:0; 3:65000 |

Table 3.

Template and example for Modbus/TCP natural language conversion.

Table 3.

Template and example for Modbus/TCP natural language conversion.

| Modbus/TCP natural language conversion format |

“From source IP [src_ip] port [src_port] to destination IP [dst_ip] port [dst_port], a Modbus/TCP [query/response] was transmitted with function code [function_code] requesting [quantity] values from register [start_address] through register [end_address], and the packet length at the time of the request was [frame_len] bytes.” |

| Example |

“From source IP 192.168.0.11 port 34048 to destination IP 192.168.0.12 port 502, a Modbus/TCP query was transmitted with function code 3 (Read Holding Registers), requesting 2 values from register 22 through register 23, and the packet length at the time of the request was 78 bytes.” |

Table 4.

Sizes of benign and malicious samples in the training, validation, and test datasets.

Table 4.

Sizes of benign and malicious samples in the training, validation, and test datasets.

| |

Benign |

Malicious |

| Train |

5,000 |

1,500 (250 samples per attack) |

| Validation |

50 |

300 (50 samples per attack) |

| Test |

52 |

206 |

Table 5.

Number of malicious samples per attack type in the test dataset.

Table 5.

Number of malicious samples per attack type in the test dataset.

| Remote System Discovery |

56 |

| Adversary-in-the-Middle |

29 |

| Unauthorized Command Message |

30 |

| Modify Parameter |

24 |

| Spoof Reporting Message |

39 |

| Remote System Information Discovery |

28 |

| Sum |

206 |

Table 6.

Components of the prompt template used for supervised fine-tuning.

Table 6.

Components of the prompt template used for supervised fine-tuning.

| Role and task definition |

Explicitly specify that the model acts as a smart-factory network security analyst. Instruct it to make conservative decisions and avoid guessing when evidence is insufficient. |

| Output format rules |

If the traffic is benign, output “Benign”. If it is malicious, output “Malicious: <Attack type>”. Also output “Reason: <the basis for that assessment>”. |

| Environment information |

Provide a description of the ICSSIM process and the OT/ICS network configuration. |

| Few-shot examples |

Include one Benign example and one example for each attack type as few-shot demonstrations. |

Table 7.

Binary classification performance for normal vs. attack traffic. Precision and recall are computed with respect to the attack class.

Table 7.

Binary classification performance for normal vs. attack traffic. Precision and recall are computed with respect to the attack class.

| Case |

Accuracy (%) |

Precision |

Recall |

F1-score |

| Case 1 |

60.08 |

1.000 |

0.500 |

0.667 |

| Case 2 |

62.02 |

1.000 |

0.524 |

0.688 |

| Case 3 |

99.61 |

1.000 |

0.995 |

0.998 |

Table 8.

Attack-type classification performance on the 206 malicious samples in the test dataset.

Table 8.

Attack-type classification performance on the 206 malicious samples in the test dataset.

| Case |

Type accuracy (%) |

Macro F1-score |

| Case 1 |

14.08 |

0.170 |

| Case 2 |

14.56 |

0.147 |

| Case 3 |

95.63 |

0.952 |

Table 9.

Per-attack-type precision, recall, and F1-score for Case 1.

Table 9.

Per-attack-type precision, recall, and F1-score for Case 1.

| Attack type |

Precision |

Recall |

F1-score |

| Modify Parameter |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Unauthorized Command Message |

0.750 |

0.800 |

0.774 |

| Remote System Discovery |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Remote System Information Discovery |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| AiTM |

0.417 |

0.172 |

0.244 |

| Spoof Reporting Message |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Table 10.

Per-attack-type precision, recall, and F1-score for Case 2.

Table 10.

Per-attack-type precision, recall, and F1-score for Case 2.

| Attack type |

Precision |

Recall |

F1-score |

| Modify Parameter |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Unauthorized Command Message |

0.789 |

1.000 |

0.882 |

| Remote System Discovery |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Remote System Information Discovery |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| AiTM |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Spoof Reporting Message |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Table 11.

Per-attack-type precision, recall, and F1-score for Case 3.

Table 11.

Per-attack-type precision, recall, and F1-score for Case 3.

| Attack type |

Precision |

Recall |

F1-score |

| Modify Parameter |

0.800 |

1.000 |

0.889 |

| Unauthorized Command Message |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| Remote System Discovery |

0.982 |

0.964 |

0.973 |

| Remote System Information Discovery |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| AiTM |

1.000 |

0.759 |

0.863 |

| Spoof Reporting Message |

0.975 |

1.000 |

0.987 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).