Submitted:

23 December 2025

Posted:

24 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

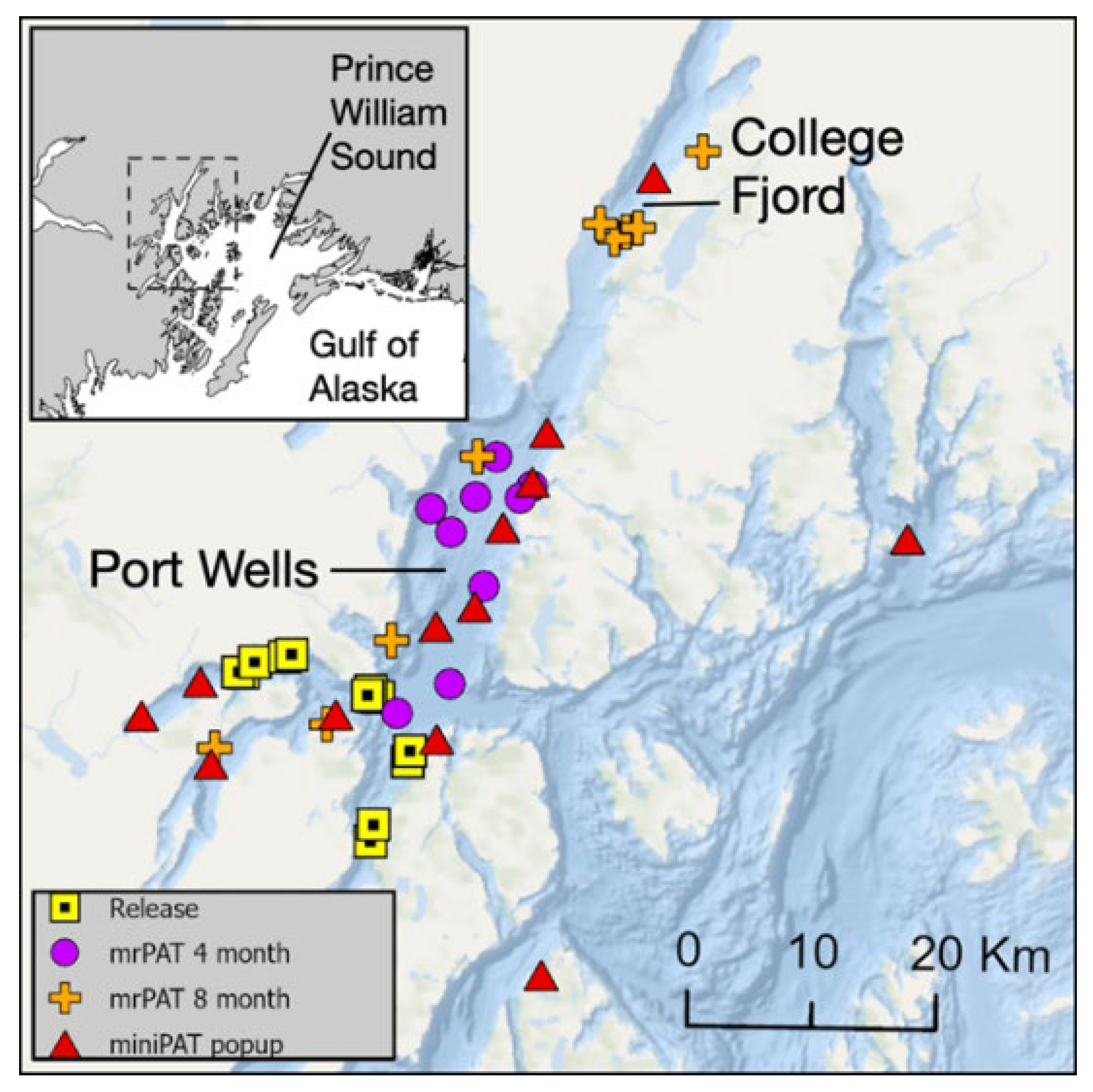

Study Location and Sampling Operations

Satellite Transmitter Deployments

Data Analysis

Horizontal Displacement

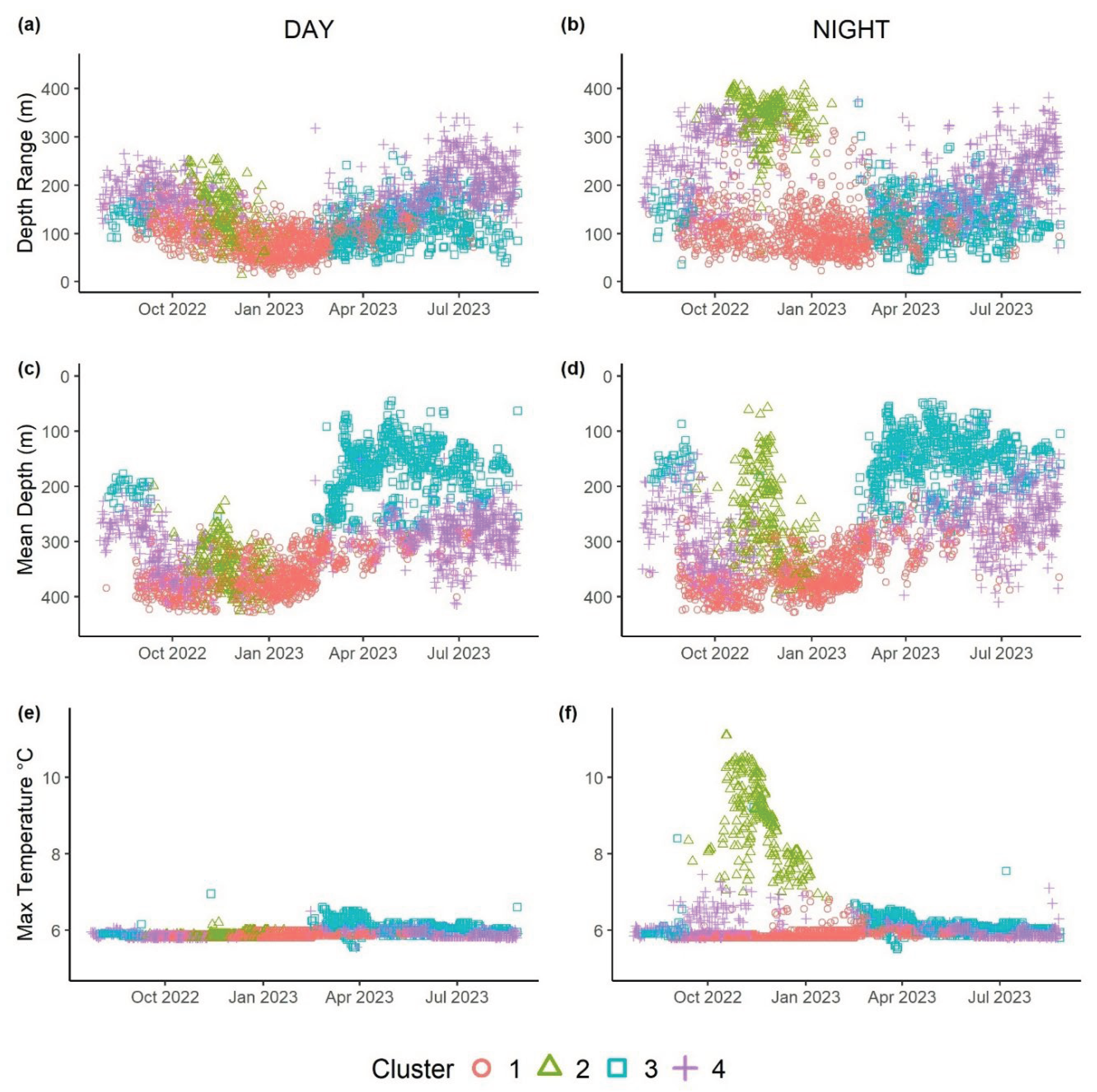

Diel Variation in Depth and Temperature

Seasonal Variation in Depth and Temperature

3. Results

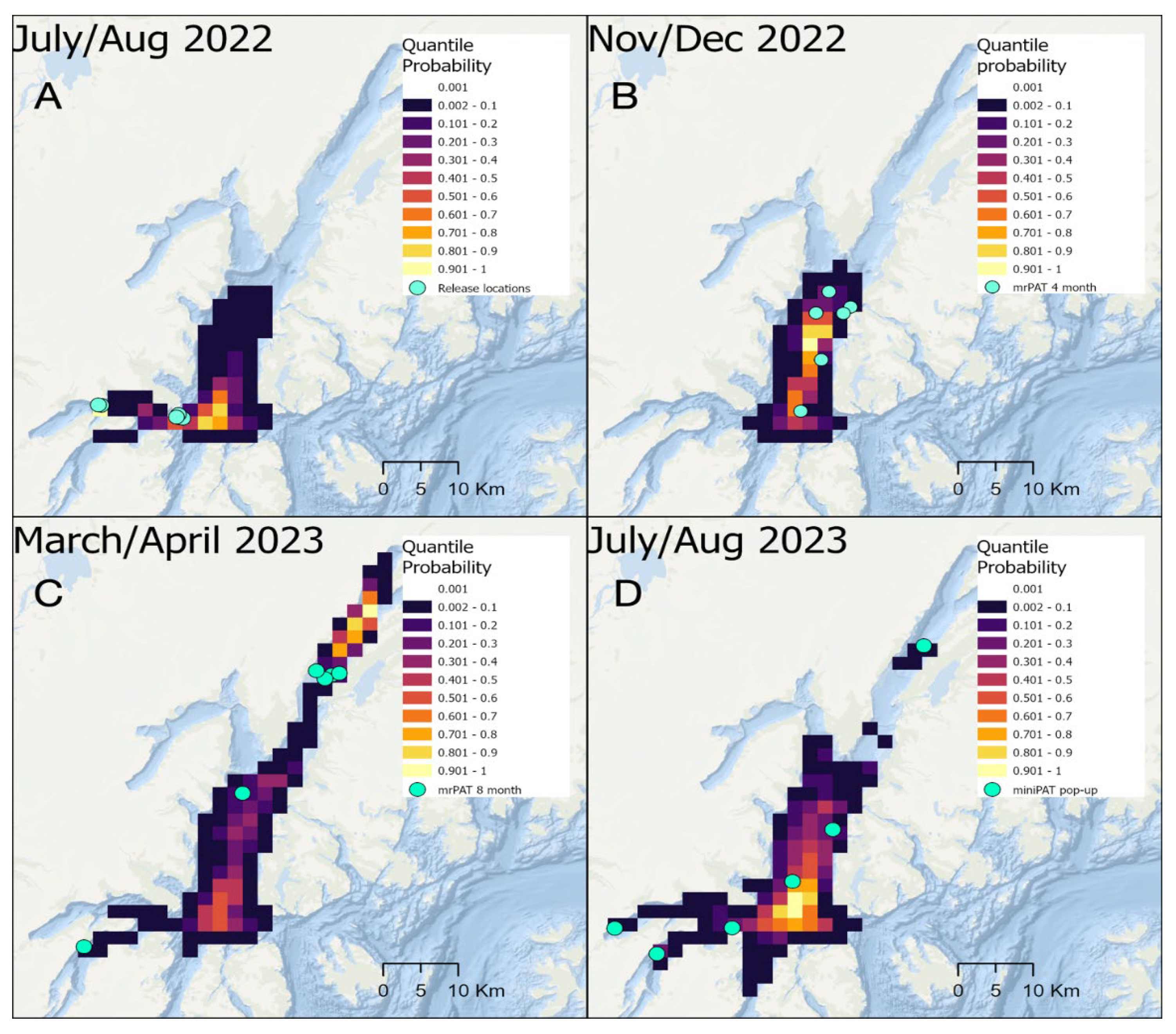

3.1. Horizontal Movement

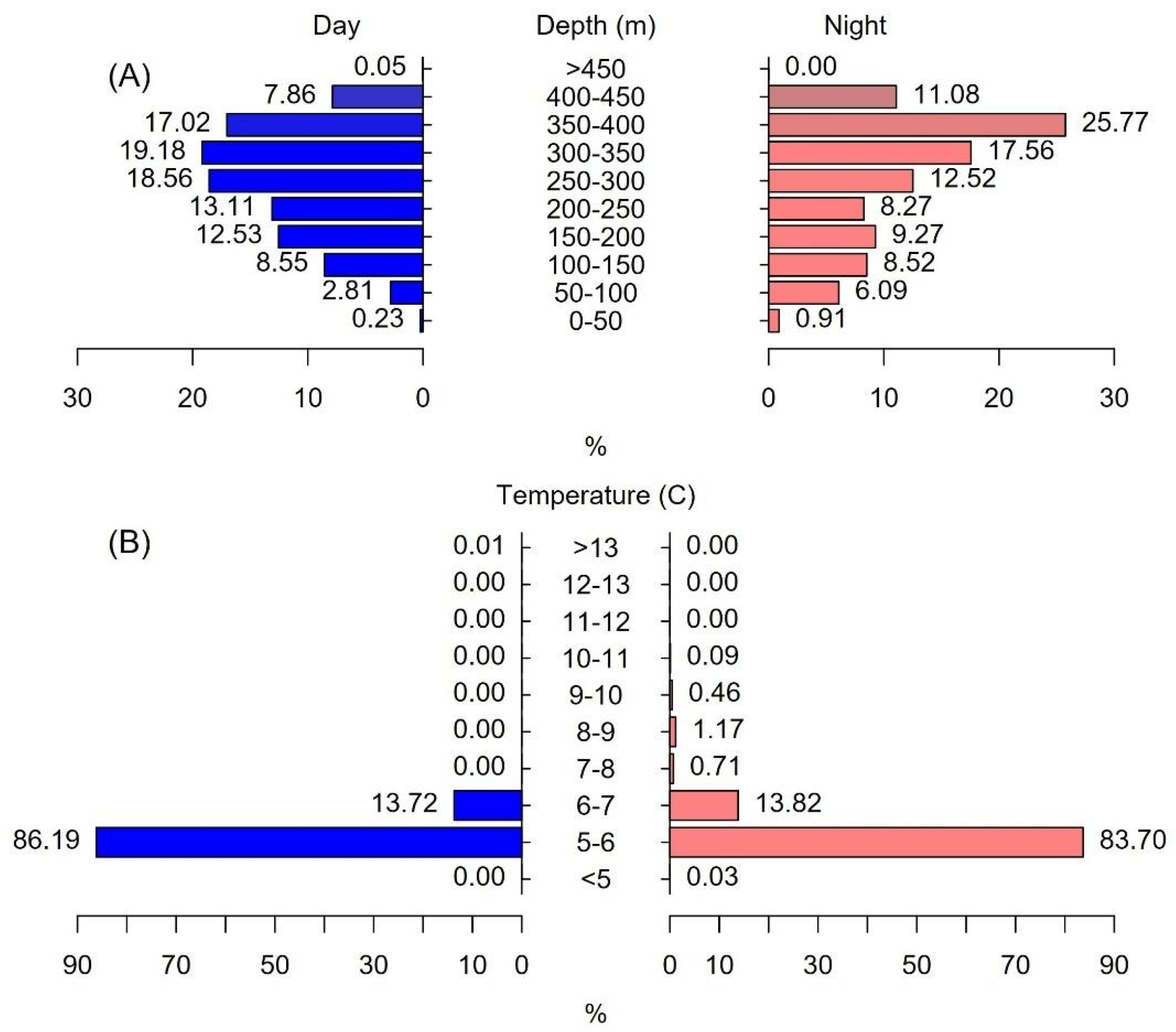

3.2. Diel Variation in Depth and Temperature

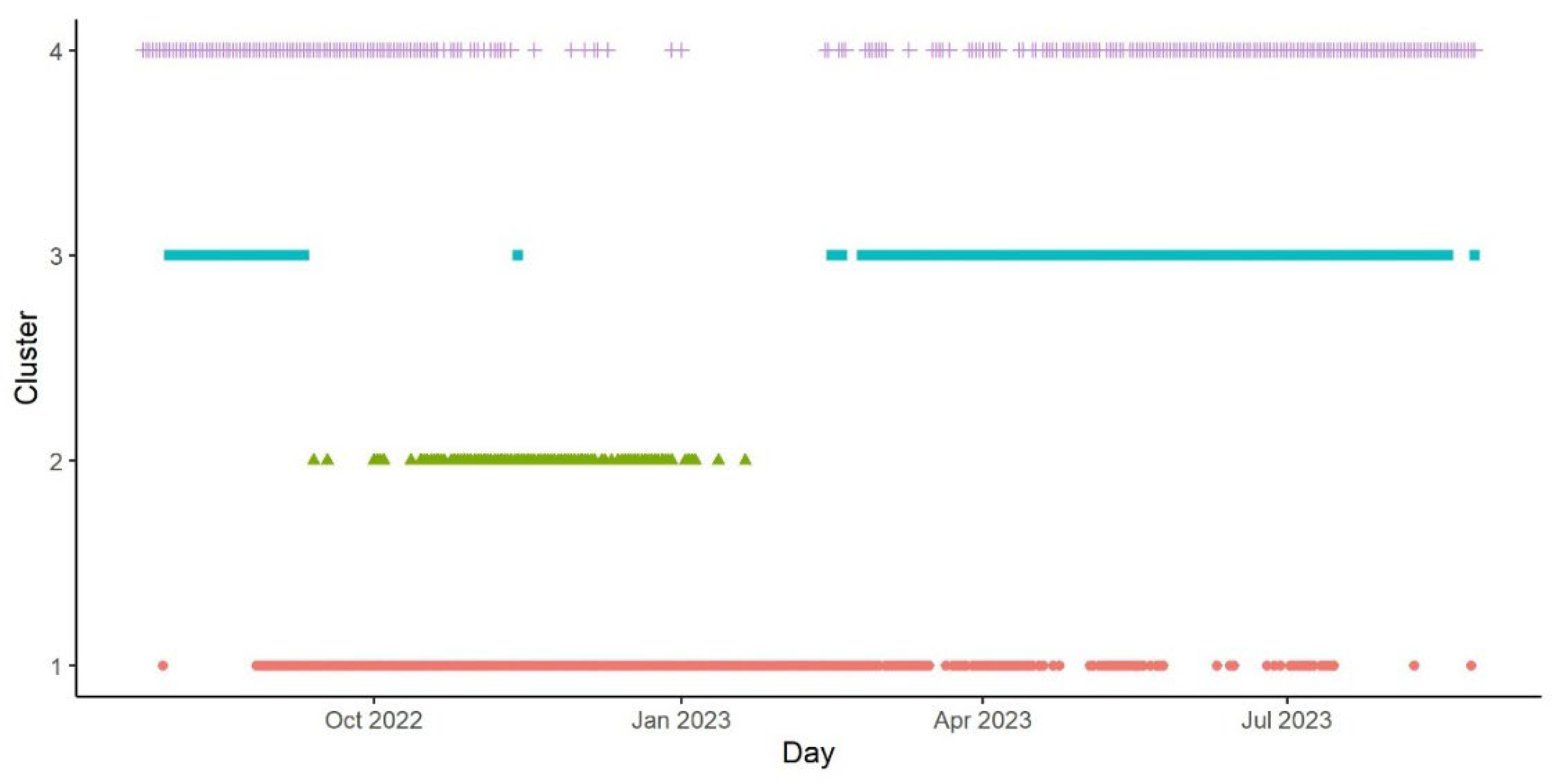

3.3. Seasonal Variation in Depth and Temperature

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PSS | Pacific sleeper shark |

| PWS | Prince William Sound |

| HMM | Hidden Markov model |

References

- Myers, R. A.; Baum, J. K.; Shepherd, T. D.; Powers, S. P.; Peterson, C. H. Cascading effects of the loss of apex predatory sharks from a coastal ocean. Science 2007, 315, 1846–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlaff, A. M.; Heupel, M. R.; Simpfendorfer, C. A. Influence of environmental factors on shark and ray movement, behaviour and habitat use: a review. Reviews in fish biology and fisheries 2014, 24, 1089–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comfort, C. M.; Weng, K. C. Vertical habitat and behaviour of the bluntnose sixgill shark in Hawaii. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography 2015, 115, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nay, T. J.; Longbottom, R. J.; Gervais, C. R.; Johansen, J. L.; Steffensen, J. F.; Rummer, J. L.; Hoey, A. S. Regulate or tolerate: Thermal strategy of a coral reef flat resident, the epaulette shark, Hemiscyllium ocellatum. Journal of Fish Biology 2021, 98, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, D. W.; Wearmouth, V. J.; Southall, E. J.; Hill, J. M.; Moore, P.; Rawlinson, K.; Morritt, D. Hunt warm, rest cool: bioenergetic strategy underlying diel vertical migration of a benthic shark. Journal of Animal Ecology 2006, 75, 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, C. D.; Arostegui, M. C.; Thorrold, S. R.; Papastamatiou, Y. P.; Gaube, P.; Fontes, J.; Afonso, P. The functional and ecological significance of deep diving by large marine predators. Annual Review of Marine Science 2022, 14, 129–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hight, B. V.; Lowe, C. G. Elevated body temperatures of adult female leopard sharks, Triakis semifasciata, while aggregating in shallow nearshore embayments: evidence for behavioral thermoregulation? Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 2007, 352, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, M. P. Distribution, habitat and movement of juvenile smooth hammerhead sharks (Sphyrna zygaena) in northern New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 2016, 50, 506–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, R. K.; Vaudo, J. J.; Sousa, L. L.; Sampson, M.; Wetherbee, B. M.; Shivji, M. S. Seasonal movements and habitat use of juvenile smooth hammerhead sharks in the western North Atlantic Ocean and significance for management. Frontiers in Marine Science 2020, 7, 566364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J. E.; Hedges, K. J.; Kessel, S. T.; Hussey, N. E. Multi-year acoustic tracking reveals transient movements, recurring hotspots, and apparent seasonality in the coastal-offshore presence of Greenland sharks (Somniosus microcephalus). Frontiers in Marine Science 2022, 9, 902854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, Y.; Matsumoto, Y.; Sato, T.; Kawato, M.; Tsuchida, S. First record of swimming speed of the Pacific sleeper shark Somniosus pacificus using a baited camera array. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 2021, 101, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claassens, L.; Phillips, B.; Ebert, D. A.; Delaney, D.; Henning, B.; Nestor, V.; Giddens, J. First records of the Pacific sleeper shark Somniosus cf. pacificus in the western tropical Pacific. Journal of Fish Biology 2023, 103, 1214–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Zhong, J.; Chen, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xie, W.; Yin, K. Southwestward expansion of the Pacific sleeper shark’s (Somniosus pacificus) known distribution into the South China Sea. Animals 2024, 14, 2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matta, M. E.; Tribuzio, C. A.; Davidson, L. N.; Fuller, K. R.; Dunne, G. C.; Andrews, A. H. A review of the Pacific sleeper shark Somniosus pacificus: biology and fishery interactions. Polar Biology 2024, 47, 433–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, D. L.; Sigler, M. F. Trends in area-weighted CPUE of Pacific sleeper sharks Somniosus pacificus in the northeast Pacific Ocean determined from sablefish longline surveys. Alaska Fishery Research Bulletin 2007, 12, 292316. [Google Scholar]

- Tribuzio, C.A.; Matta, M.E.; Echave, K.; Rodgveller, C. Assessment of the Shark stock complex in the Gulf of Alaska; North Pacific Fishery Management Council: Anchorage, AK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Di Lorenzo, E.; Mantua, N. Multi-year persistence of the 2014/15 North Pacific marine heatwave. Nature Climate Change 2016, 6, 1042–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbeaux, S. J.; Holsman, K.; Zador, S. Marine heatwave stress test of ecosystem-based fisheries management in the Gulf of Alaska Pacific cod fishery. Frontiers in Marine Science 2020, 7, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piatt, J. F.; Parrish, J. K.; Renner, H. M.; Schoen, S. K.; Jones, T. T.; Arimitsu, M. L.; Sydeman, W. J. Extreme mortality and reproductive failure of common murres resulting from the northeast Pacific marine heatwave of 2014-2016. PloS one 2020, 15, e0226087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, H. M.; Piatt, J. F.; Renner, M.; Drummond, B. A.; Laufenberg, J. S.; Parrish, J. K. Catastrophic and persistent loss of common murres after a marine heatwave. Science 2024, 386, 1272–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulbert, L. B.; Sigler, M. F.; Lunsford, C. R. Depth and movement behaviour of the Pacific sleeper shark in the north-east Pacific Ocean. Journal of fish biology 2006, 69, 406–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halverson, M. J.; Bélanger, C.; Gay, S. M., III. Seasonal transport variations in the straits connecting Prince William Sound to the Gulf of Alaska. Continental Shelf Research 2013, 63, S63–S78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussey, N. E.; Cosandey-Godin, A.; Walter, R. P.; Hedges, K. J.; VanGerwen-Toyne, M.; Barkley, A. N.; Fisk, A. T. Juvenile Greenland sharks Somniosus microcephalus (Bloch & Schneider, 1801) in the canadian arctic. Polar biology 2015, 38, 493–504. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, T. R.; Bishop, A.; Guthridge, J.; Hocking, R.; Horning, M.; Lowe, C. G. Capture, husbandry, and oxygen consumption rate of juvenile Pacific sleeper sharks (Somniosus pacificus). Environmental Biology of Fishes 2022, 105, 1519–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, D. G.; Robertson, C. J. R.; Murray, M. D. Validating locations from CLS: Argos satellite telemetry. Notornis 2007, 54, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, D. P.; Robinson, P. W.; Arnould, J. P.; Harrison, A. L.; Simmons, S. E.; Hassrick, J. L.; Crocker, D. E. Accuracy of ARGOS locations of pinnipeds at-sea estimated using Fastloc GPS. PloS one 2010, 5, e8677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussey, N. E.; Orr, J.; Fisk, A. T.; Hedges, K. J.; Ferguson, S. H.; Barkley, A. N. Mark report satellite tags (mrPATs) to detail large-scale horizontal movements of deep water species: First results for the Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus). Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers 2018, 134, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoolihan, J. P.; Luo, J.; Abascal, F. J.; Campana, S. E.; De Metrio, G.; Dewar, H.; Rooker, J. R. Evaluating post-release behaviour modification in large pelagic fish deployed with pop-up satellite archival tags. ICES Journal of Marine Science 2011, 68, 880–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, M. W.; Righton, D.; Thygesen, U. H.; Andersen, K. H.; Madsen, H. Geolocation of North Sea cod (Gadus morhua) using hidden Markov models and behavioural switching. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2008, 65, 2367–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thygesen, U. H.; Pedersen, M. W.; Madsen, H. Geolocating fish using hidden Markov models and data storage tags. In Tagging and tracking of marine animals with electronic devices; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2009; pp. 277–293. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, J. K.; Bryan, D. R.; Rand, K. M.; Arostegui, M. C.; Braun, C. D.; Galuardi, B.; McDermott, S. F. Geolocation of a demersal fish (Pacific cod) in a high-latitude island chain (Aleutian Islands, Alaska). Animal Biotelemetry 2023, 11, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J. K.; Tribuzio, C. A. Development and parameterization of a data likelihood model for geolocation of a bentho-pelagic fish in the North Pacific Ocean. Ecological Modelling 2023, 478, 110282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, A. C.; Norcross, B. L.; Wilson, D.; Nielsen, J. L. Evaluating light-based geolocation for estimating demersal fish movements in high latitudes. Fishery Bulletin 2006, 104, 571–579. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, J.K.; McDermott, S.; Rand, K.; Dawson, L.; Bryan, D.R.; Britt, L.; Kotwicki, S.; Nichol, D. Insights into the northward shift of Pacific cod in warming Bering Sea waters from pop-up satellite archival tags. Canadian Journal of Fisheries & Aquatic Sciences 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musyl, M. K.; Brill, R.; Curran, D. S.; Fragoso, N. M.; McNaughton, L.; Nielsen, A.; Moyes, C. D. Postrelease survival, vertical and horizontal movements, and thermal habitats of five species of pelagic sharks in the central Pacific Ocean. Fishery Bulletin 2011, 109, 341. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; O’Reilly, K. M.; Perry, G. L.; Taylor, G. A.; Dennis, T. E. Extending the functionality of behavioural change-point analysis with k-means clustering: a case study with the little penguin (Eudyptula minor). PloS one 2015, 10, e0122811. [Google Scholar]

- Kinney, M. J.; Carvalho, F.; Kai, M.; Semba, Y.; Liu, K. M.; Tsai, W. P.; Teo, S. L. H. Cluster analysis used to re-examine fleet definitions of North Pacific fisheries with spatiotemporal consideration of blue shark size and sex data. PIFSC Working Paper 2022, WP-22-001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseeuw, P. J. Silhouettes: a graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster analysis. Journal of computational and applied mathematics 1987, 20, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassambara, A.; Mundt, F. Factoextra: extract and visualize the results of multivariate data analyses, R package version 1.0. 7. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Taggart, Jim; Philip Hooge; National Park Service. unpublished data.

- Carlson, J. K.; Heupel, M. R.; Bethea, D. M.; Hollensead, L. D. Coastal habitat use and residency of juvenile Atlantic sharpnose sharks (Rhizoprionodon terraenovae). Estuaries and Coasts 2008, 31, 931–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C. F.; Lyons, K.; Jorgensen, S. J.; O’Sullivan, J.; Winkler, C.; Weng, K. C.; Lowe, C. G. Quantifying habitat selection and variability in habitat suitability for juvenile white sharks. PloS one 2019, 14, e0214642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, J. E.; Hedges, K. J.; Hussey, N. E. Seasonal residency, activity space, and use of deep-water channels by Greenland sharks (Somniosus microcephalus) in an Arctic fjord system. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2022, 79, 314–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S. W.; Thedinga, J. F.; Neff, A. D.; Harris, P. M.; Lindeberg, M. R.; Maselko, J. M.; Rice, S. D. Fish assemblages in nearshore habitats of Prince William Sound, Alaska. Northwest Science 2010, 84, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigler, M. F.; Hulbert, L. B.; Lunsford, C. R.; Thompson, N. H.; Burek, K.; O’Corry-Crowe, G.; Hirons, A. C. Diet of Pacific sleeper shark, a potential Steller sea lion predator, in the north-east Pacific Ocean. Journal of Fish Biology 2006, 69, 392–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlheim, M.; Schulman-Janiger, A.; Black, N.; Ternullo, R.; Ellifrit, D.; Balcomb, K., III. Eastern temperate North Pacific offshore killer whales (Orcinus orca): Occurrence, movements, and insights into feeding ecology. Marine Mammal Science 2008, 24, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schorr, G. S.; Hanson, M. B.; Falcone, E. A.; Emmons, C. K.; Jarvis, S. M.; Andrews, R. D.; Keen, E. M. Movements and diving behavior of the Eastern North Pacific offshore killer whale (Orcinus orca). Frontiers in Marine Science 2022, 9, 854893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisk, A. T.; Lydersen, C.; Kovacs, K. M. Archival pop-off tag tracking of Greenland sharks Somniosus microcephalus in the High Arctic waters of Svalbard, Norway. Marine Ecology Progress Series 2012, 468, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campana, S. E.; Fisk, A. T.; Klimley, A. P. Movements of Arctic and northwest Atlantic Greenland sharks (Somniosus microcephalus) monitored with archival satellite pop-up tags suggest long-range migrations. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography 2015, 115, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Wang, J. Interannual variability and sensitivity study of the ocean circulation and thermohaline structure in Prince William Sound, Alaska. Continental Shelf Research 2004, 24, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Santo, V.; Bennett, W. A. Is post-feeding thermotaxis advantageous in elasmobranch fishes? Journal of Fish Biology 2011, 78, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ste-Marie, E.; Watanabe, Y. Y.; Semmens, J. M.; Marcoux, M.; Hussey, N. E. A first look at the metabolic rate of Greenland sharks (Somniosus microcephalus) in the Canadian Arctic. Scientific reports 2020, 10, 19297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arimitsu, M. L.; Piatt, J. F.; Madison, E. N.; Conaway, J. S.; Hillgruber, N. Oceanographic gradients and seabird prey community dynamics in glacial fjords. Fisheries Oceanography 2012, 21, 148–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Womble, J. N.; Gende, S. M. Post-breeding season migrations of a top predator, the harbor seal (Phoca vitulina richardii), from a marine protected area in Alaska. PloS one 2013, 8, e55386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lydersen, C.; Assmy, P.; Falk-Petersen, S.; Kohler, J.; Kovacs, K. M.; Reigstad, M.; Zajaczkowski, M. The importance of tidewater glaciers for marine mammals and seabirds in Svalbard, Norway. Journal of Marine Systems 2014, 129, 452–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hop, H.; Wold, A.; Vihtakari, M.; Assmy, P.; Kuklinski, P.; Kwasniewski, S.; Steen, H. Tidewater glaciers as “climate refugia” for zooplankton-dependent food web in Kongsfjorden, Svalbard. Frontiers in Marine Science 2023, 10, 1161912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straneo, F.; Heimbach, P. North Atlantic warming and the retreat of Greenland’s outlet glaciers. Nature 2013, 504, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNabb, R. W.; Hock, R. Alaska tidewater glacier terminus positions, 1948–2012. Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface 2014, 119, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachtsheim, D. A.; Ryan, S.; Schröder, M.; Jensen, L.; Oosthuizen, W. C.; Bester, M. N.; Bornemann, H. Foraging behaviour of Weddell seals (Leptonychotes weddellii) in connection to oceanographic conditions in the southern Weddell Sea. Progress in Oceanography 2019, 173, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazen, E. L.; Abrahms, B.; Brodie, S.; Carroll, G.; Jacox, M. G.; Savoca, M. S.; Bograd, S. J. Marine top predators as climate and ecosystem sentinels. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 2019, 17, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bestley, S.; Ropert-Coudert, Y.; Bengtson Nash, S.; Brooks, C. M.; Cotté, C.; Dewar, M.; Wienecke, B. Marine ecosystem assessment for the Southern Ocean: birds and marine mammals in a changing climate. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 2020, 8, 566936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, C. R.; Roquet, F.; Baudel, S.; Belbeoch, M.; Bestley, S.; Blight, C.; Woodward, B. Animal borne ocean sensors–AniBOS–An essential component of the global ocean observing system. Frontiers in Marine Science 2021, 8, 751840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Shark ID | Release Date | Sex | TL (cm) | Time at liberty (Days) | MiniPAT Recovery | mrPAT 120d | mrPAT 240d | Acoustic tag |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SP22-01 | 6/24/22 | M | 229 | 17 | REC | 120 | 241 | E |

| SP22-02 | 6/24/22 | F | 284 | 31 | REC | 32 | 26 | E |

| SP22-03 | 7/12/22 | M | 241 | 357 | Argos-172 | 120 | 148 | E |

| SP22-04 | 7/13/22 | F | 305 | 86 | REC | 89 | 83 | E |

| SP22-05 | 7/22/22 | F | 248 | 365 | REC | 121 | 241 | - |

| SP22-06 | 7/22/22 | F | >300* | - | - | - | - | - |

| SP22-07 | 7/24/22 | F | 244 | - | - | - | - | - |

| SP22-08 | 7/24/22 | F | 230 | 365 | REC | 121 | 191 | - |

| SP22-09 | 8/11/22 | F | 175¥ | - | - | - | - | E |

| SP22-10 | 8/12/22 | M | 343 | 365 | Argos-440 | 120 | 241 | E |

| SP22-11 | 8/14/22 | F | 262 | 46 | Argos-892 | - | - | - |

| SP22-12 | 8/25/22 | F | 321 | 365 | REC | 121 | 241 | E |

| SP22-13 | 8/25/22 | M | 280 | 365 | REC | 121 | 241 | E |

| SP22-14 | 8/25/22 | M | 273 | 365 | REC | 121 | 241 | I |

| SP22-15 | 8/27/22 | F | 253 | 365 | REC | 121 | 241 | E |

| SP22-16 | 8/27/22 | F | 271 | 365 | REC | 121 | 241 | I |

| Shark ID | Release -4mo mrPAT (120d) | 4mo mrPAT-8mo mrPAT (120d) | 8mo mrPAT-miniPAT PopUp (120d) | Release -miniPAT PopUp (367 d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SP22_05 | 20.6 | 25.3 | 1.1 | 7.6 |

| SP22_08 | 23.7 | * | * | 8.5 |

| SP22_12 | 16.1 | 18.3 | 25.6 | 23.9 |

| SP22_13 | 6.3 | 38.8 | 54.9 | 18.7 |

| SP22_14 | 20.9 | 22.3 | 26.2 | 17.0 |

| SP22_15 | 19.8 | 22.1 | 30.0 | 7.5 |

| SP22_16 | 21.7 | 20.4 | 5.8 | 47.5 |

| Mean | 18.4 | 24.5 | 23.9 | 18.7 |

| S.d. | 5.8 | 7.4 | 17.6 | 14.2 |

| Day | Night | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster | n | Depth Range (m) | Mean Depth (m) | Max Temp (°C) | Depth Range (m) | Mean Depth (m) | Max Temp (°C) |

| 1 | 980 | -0.643 | 0.743 | -0.461 | -0.634 | 0.866 | -0.400 |

| 2 | 240 | 0.075 | 0.587 | -0.452 | 1.873 | -0.052 | 2.838 |

| 3 | 363 | -0.216 | -1.404 | 0.977 | -0.428 | -1.257 | -0.167 |

| 4 | 686 | 1.093 | 0.034 | -0.089 | 0.646 | -0.054 | -0.267 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).