1. Introduction and Background

Nonprofit institutions (NPIs) have historically occupied a crucial role in delivering social goods, particularly in domains where government or private sector interventions remain insufficient. Their contributions include poverty alleviation, health care delivery, community empowerment, and educational access. However, over the past two decades, the landscape in which NPIs operate has become increasingly volatile. Declining state subsidies, shrinking philanthropic donations, and growing competition for limited resources have placed severe strains on the sustainability of traditional nonprofit models [

1]. This resource scarcity has prompted organizational leaders to search for new strategies that enhance resilience while preserving their core missions.

A central adaptation strategy has been the adoption of hybrid forms that blend social value creation with commercial logics. These hybrid entities, often described as social enterprises (SEs), pursue financial sustainability through entrepreneurial activity while continuing to prioritize social missions [

2]. The shift represents not only a change in funding strategies but also a deeper institutional transformation. Social enterprises must simultaneously operate within nonprofit logics of altruism and accountability while embedding business-oriented practices that demand efficiency, innovation, and market responsiveness.

The emergence of SEs is closely linked to broader global trends in public management and governance. In many regions, austerity policies have restructured state financing for social services, creating expectations that nonprofit actors assume expanded responsibilities [

3]. Similarly, demographic changes and rising social inequality have increased demand for nonprofit interventions, further intensifying the competition for scarce philanthropic resources. Against this backdrop, SEs are positioned as a viable model that can integrate entrepreneurial strategies into social missions.

Scholars have characterized this transformation as a form of institutional entrepreneurship, where leaders actively reshape organizational fields by introducing novel practices that diverge from established norms [

4]. Chief executive officers, finance directors, and senior managers act as institutional entrepreneurs when they embed commercial activities within nonprofit structures. This agency-driven process highlights that the evolution of NPIs into SEs is not merely a reactive adjustment to environmental pressures but a proactive redesign of institutional logics.

Existing research has emphasized the tensions SEs face in managing dual logics of social mission and economic sustainability. These tensions manifest in dilemmas about resource allocation, stakeholder communication, and accountability [

5]. Some studies suggest compartmentalization, where social and economic activities are managed separately, while others advocate integration, where the two logics are intertwined at every level. However, much of this literature focuses on established SEs, leaving a relative gap in understanding the early stages of transformation.

The process of transformation typically unfolds in stages. First, organizations adopt entrepreneurial revenue-generation strategies such as fee-for-service models, social retail ventures, or partnerships with private firms [

6]. Second, they undergo professionalization, adopting business-like structures such as performance monitoring, marketing systems, and managerial accounting. Third, organizations must build legitimacy by reassuring stakeholders that their commercial activities reinforce rather than compromise social objectives [

7]. This sequential yet overlapping process reflects the dynamic balancing act required to sustain a dual mission.

From a theoretical perspective, the transformation of NPIs into SEs has implications for how institutional work is understood. It challenges assumptions about the rigidity of organizational fields and demonstrates that actors can actively reshape the rules of engagement. In particular, nonprofit leaders serve as cultural brokers who translate market practices into socially acceptable forms [

8]. This translation is vital in maintaining trust with donors, beneficiaries, and regulators while simultaneously building credibility with business partners.

From a practical standpoint, nonprofit leaders increasingly recognize that reliance on donations and grants alone is unsustainable. By cultivating earned-income streams, organizations not only secure greater autonomy but also gain strategic flexibility to invest in innovation. Yet these gains are accompanied by risks. Over-commercialization may invite criticism of mission drift, while insufficient commercialization can leave organizations financially vulnerable [

9]. Navigating this delicate balance requires deliberate strategy and adaptive leadership.

In addition to organizational challenges, the evolution of SEs raises normative questions about the role of nonprofits in society. Are nonprofits diluting their missions by engaging in commercial activities, or are they pragmatically enhancing their capacity for impact? Scholars have argued that far from undermining their values, entrepreneurial models can expand the scope and scale of social change initiatives when managed responsibly [

10]. This debate underscores the ethical dimensions of nonprofit transformation.

The UK context provides a particularly salient case for studying these dynamics. Government austerity measures following the 2008 financial crisis drastically reduced public funding for charities, compelling many NPIs to adopt commercial logics to survive [

11]. At the same time, social entrepreneurship has been actively promoted as a policy solution, leading to a vibrant ecosystem of hybrid organizations. These dynamics create fertile ground for analyzing the drivers, processes, and implications of nonprofit transformation.

Ultimately, the introduction and background highlight why understanding nonprofit evolution is both academically significant and practically urgent. As nonprofits navigate resource scarcity and legitimacy pressures, their ability to evolve into SEs becomes a determinant of long-term survival and relevance. This paper seeks to contribute to this discourse by analyzing how organizational leaders embed commercial practices, professionalize operations, and legitimize dual missions in the early stages of transformation.

In summary, the transformation of nonprofits into social enterprises can be seen as an iterative process shaped by entrepreneurial adaptation, institutional work, and stakeholder negotiation. By framing this process through the lens of institutional entrepreneurship, the study not only documents emerging practices but also provides insights into how hybrid organizations can sustain both social and economic imperatives. The following sections will elaborate on related literature, research methodology, empirical findings, and implications for theory and practice.

2. Literature Review on Nonprofit Transformation

The evolution of nonprofit institutions (NPIs) into social enterprises (SEs) has been widely debated in organizational studies and social entrepreneurship literature. Scholars have examined the motivations, mechanisms, and consequences of this transformation, noting the complexity of managing hybrid identities that combine social missions with commercial strategies [

12]. This literature review synthesizes key themes, highlighting conceptual frameworks, governance approaches, and empirical insights that inform the understanding of nonprofit transformation.

2.1. Conceptualizations of Social Enterprise

The term social enterprise has been defined in multiple ways across regions. European perspectives often emphasize collective ownership, cooperative structures, and strong social missions, while U.S.-based definitions focus on earned-income strategies and entrepreneurial revenue generation [

1,

3]. This divergence reflects broader institutional logics: European SEs tend to align with solidarity and cooperative traditions, whereas American SEs often adopt market-based approaches that prioritize self-sufficiency. These conceptual variations underscore the importance of context in shaping nonprofit transformation.

2.2. Hybrid Organizations and Institutional Complexity

Nonprofits that adopt commercial practices are frequently described as hybrid organizations because they straddle competing logics of social welfare and economic efficiency. Scholars such as Battilana and Dorado [

5] argue that hybrids are inherently unstable unless carefully managed through structural or cultural mechanisms. Strategies to address this complexity include compartmentalization (keeping logics separate), selective integration (blending certain practices), and full integration (merging logics into a unified organizational identity). Each approach presents trade-offs in terms of flexibility, legitimacy, and stakeholder trust.

2.3. Governance Challenges

The governance of SEs has been a recurring theme in the literature. Boards of directors and senior executives are often tasked with balancing competing imperatives, leading to questions about accountability structures and decision-making processes [

9]. Some studies emphasize the risks of mission drift, where commercial imperatives overshadow social objectives, while others suggest that entrepreneurial strategies can strengthen nonprofits by diversifying revenue streams. This debate reflects broader concerns about whether commercialization enhances or undermines nonprofit missions.

2.4. Legitimacy and Stakeholder Engagement

Legitimacy has been identified as a critical dimension of nonprofit transformation. Organizations must persuade donors, clients, employees, and regulators that their hybrid model authentically serves social goals [

7]. Mechanisms to build legitimacy include transparent reporting, communication of social impact, and reinvestment of commercial revenues into mission-driven activities. Researchers such as Tracey et al. [

4] note that legitimacy-building often requires deliberate institutional work, where leaders actively shape perceptions and narratives around hybrid practices.

2.5. Professionalization of Nonprofits

Professionalization is another important theme in the transformation literature. As nonprofits adopt business-like practices, they introduce managerial systems, financial controls, and performance monitoring tools [

13]. While professionalization increases efficiency and credibility, critics argue that it may erode participatory values and volunteer-driven cultures. The dual pressures of efficiency and inclusivity remain unresolved, creating ongoing tensions in hybrid organizations.

2.6. Revenue Generation Models

Studies have catalogued various entrepreneurial strategies adopted by SEs, including fee-for-service arrangements, microfinance, social retail ventures, and cross-sector partnerships [

14]. These models enable nonprofits to reduce dependency on external donors while cultivating sustainable revenue streams. However, the appropriateness of each model depends on the organization’s mission, market context, and stakeholder expectations. Comparative studies reveal that while earned-income models are common in the United States, European SEs often prioritize cooperative ventures supported by government frameworks [

15].

2.7. Comparative Perspectives

Cross-national analyses reveal significant variations in how SEs emerge and function. For example, Defourny and Nyssens [

1] highlight that European SEs are often embedded within welfare regimes, whereas U.S. SEs arise from entrepreneurial cultures with minimal state intervention. These differences have implications for nonprofit transformation: European NPIs often integrate commercial practices as supplements to strong welfare systems, while U.S. NPIs adopt them as survival strategies in competitive markets. Such comparative insights broaden the understanding of institutional entrepreneurship across contexts.

2.8. Institutional Entrepreneurship

Institutional entrepreneurship provides a valuable theoretical lens to explain how leaders drive nonprofit transformation. According to Mair and Marti [

8], institutional entrepreneurs not only exploit opportunities but also reshape institutional environments by legitimizing new practices. Leaders of SEs act as change agents who introduce commercial logics into nonprofit fields, constructing new forms of organizational legitimacy. This perspective emphasizes agency and innovation in the transformation process, distinguishing it from purely reactive adaptations.

2.9. Ethical Debates

The literature also raises ethical concerns about nonprofit commercialization. Critics warn that the pursuit of market revenues risks diluting social missions and excluding marginalized beneficiaries unable to pay for services [

10]. Others counter that commercialization enhances autonomy and sustainability, enabling organizations to scale their impact responsibly. This ongoing debate reflects divergent views about the appropriate role of markets in addressing social challenges.

2.10. Gaps in Existing Research

Despite extensive scholarship, several gaps remain. Much of the literature emphasizes the challenges of managing hybrid identities after transformation, but relatively few studies focus on the early stages of adoption, when nonprofits first experiment with commercial practices. Additionally, empirical work is often constrained to small samples or single-case studies, limiting generalizability. Broader, multi-sectoral analyses are needed to capture the diversity of nonprofit transformations across contexts.

2.11. Integration into Present Study

The present study addresses these gaps by focusing on the initial stages of nonprofit transformation in the United Kingdom. By applying the lens of institutional entrepreneurship, it highlights how leaders embed commercial practices, professionalize structures, and build legitimacy from the outset. This approach provides a process-oriented understanding of hybridization, complementing existing research that has primarily focused on post-transformation dilemmas.

2.12. Summary of Literature Review

In summary, the literature on nonprofit transformation underscores the complexity of blending social and economic logics within hybrid organizations. Key themes include conceptual diversity, governance challenges, legitimacy concerns, professionalization, revenue models, and ethical debates. While prior research provides valuable insights, further empirical investigation is necessary to understand how NPIs navigate the initial adoption of commercial practices. The present study builds upon this foundation, offering an empirical contribution that enhances theoretical and practical understanding of nonprofit evolution.

3. Research Methodology

This study adopts a qualitative, multiple-case research design to examine how nonprofit institutions (NPIs) in the United Kingdom initiate and navigate transformation into social enterprises (SEs). A qualitative approach is appropriate given the processual, practice-based, and context-dependent nature of organizational transformation and institutional entrepreneurship [

16,

17]. By investigating several NPIs at different stages of change, the design enables analytical generalization and pattern matching across cases rather than statistical inference.

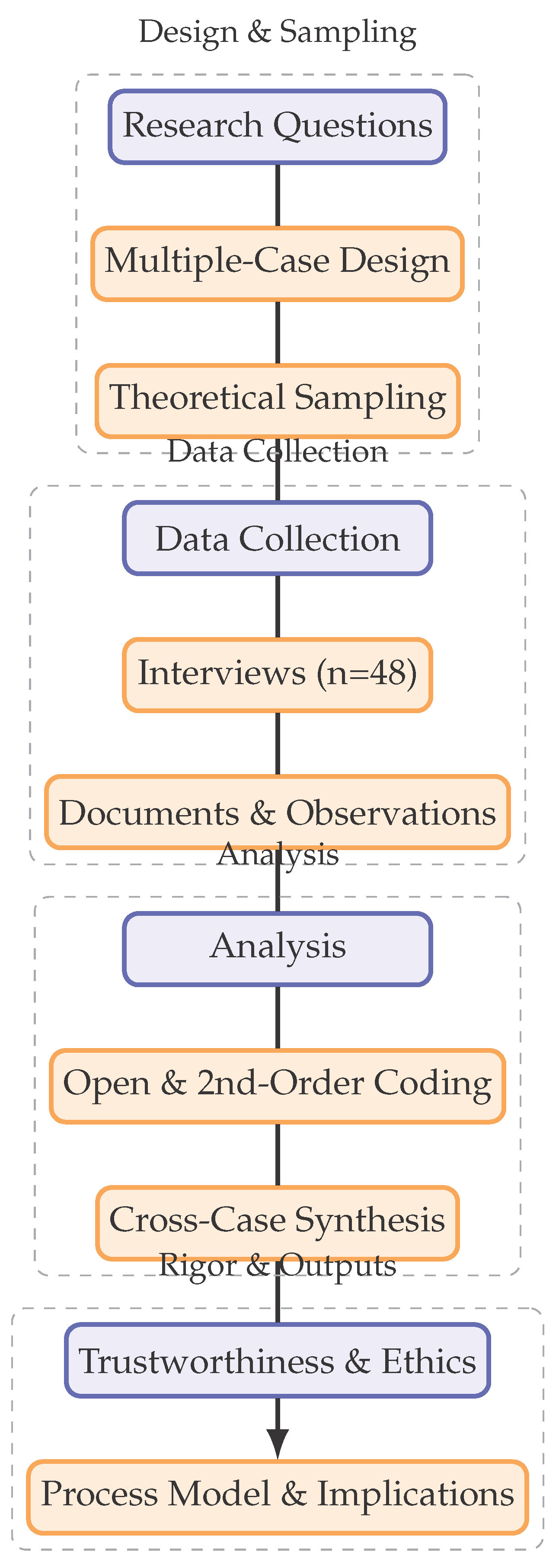

3.1. Research Questions and Design Logic

The inquiry is guided by the following questions: (RQ1) How do nonprofit leaders introduce and legitimize commercial practices in mission-driven organizations? (RQ2) What organizational routines and governance mechanisms support professionalization during early transformation? (RQ3) How do stakeholders perceive and negotiate tensions between social and market logics? The logic of a multiple-case design strengthens external validity through replication across sites and supports theoretical extension to hybrid-organization and institutional-entrepreneurship literatures [

4,

17].

3.2. Sampling Strategy

We employed purposive, theoretical sampling to select cases that exhibited variation on key dimensions: organizational size (micro to medium), service domain (health, education, community services), funding mix (grant-heavy vs. earned-income emerging), and stage of transformation (initiation, consolidation, early scaling). Initial candidates were drawn from UK charity registers and social enterprise directories; subsequent cases were added via maximum-variation and negative-case sampling to test emergent explanations [

18]. The final sample comprised six focal NPIs and four auxiliary informant organizations (funders, support agencies).

3.3. Data Sources and Collection

Primary data consisted of 48 semi-structured interviews (45–90 minutes each) with chief executives, finance directors, program managers, trustees, and frontline staff. Interviews explored strategy formation, revenue experimentation, governance changes, and stakeholder reactions. Secondary data included annual reports, board minutes, strategy decks, impact statements, regulator filings, and websites. Non-participant observations of board or committee meetings (where permitted) complemented interview data and enabled triangulation [

16]. All interviews were audio-recorded with consent and professionally transcribed.

3.4. Interview Protocol and Ethics

The interview guide balanced consistency and flexibility, using open-ended prompts, critical incidents, and timeline elicitation to reconstruct transformation processes. Ethical approval was obtained from the host institution; participants received information sheets, could withdraw at any time, and are anonymized using role-based pseudonyms. Sensitive financial details were aggregated to protect confidentiality. Data were stored on encrypted, access-controlled repositories following institutional policies and GDPR principles.

3.5. Analytic Procedure

Analysis followed a structured inductive approach combining the Gioia methodology (1st-order informant-centric coding, 2nd-order themes, and aggregate dimensions) with reflexive thematic analysis to preserve contextual nuance [

19,

20]. We began with open coding of interview segments, labeling actions (e.g., “piloting fee-for-service,” “revising board subcommittees”) and meanings (e.g., “protecting mission integrity”). Codes were iteratively clustered into themes such as entrepreneurial experimentation, professionalization routines, and legitimacy work, which later informed a staged process model.

3.6. Cross-Case Synthesis and Pattern Matching

Within-case narratives were developed for each organization, then compared across cases to surface convergent and divergent patterns. We used visual displays and matrices to examine co-occurrence of mechanisms (e.g., revenue pilots co-emerging with impact reporting upgrades) and to test rival explanations (e.g., resource slack vs. leadership framing). Pattern matching and explanation building enhanced internal validity [

16].

3.7. Reliability and Trustworthiness

To enhance reliability, we maintained a transparent chain of evidence linking raw data to codes, themes, and claims. Two researchers independently coded a 25% subset and discussed discrepancies to calibrate the codebook. We used member reflections (sharing interim thematic maps with a subset of participants) to test interpretive resonance, and triangulated across interviews, documents, and observations. Trustworthiness was further supported through reflexive memos and an audit trail [

21].

3.8. Researcher Positionality

Given the interpretive orientation of the study, we documented researcher assumptions regarding social enterprise efficacy, public-sector austerity, and commercialization risks. Reflexive practices (analytic memos, peer debriefs) were used to check confirmation bias and to separate emic accounts from etic interpretations.

3.9. Data Management and Transparency

All transcripts and documents were managed using qualitative analysis software with role-based access. We retained codebooks, thematic schemas, and case memos as supplementary materials. While full datasets cannot be publicly released due to confidentiality, the codebook, anonymized quotes, and the case-selection rubric are available upon request, subject to ethics protocols.

3.10. Limitations

The study focuses on UK NPIs; transferability to other institutional contexts (e.g., Continental Europe, U.S.) should be considered with caution. Additionally, self-report biases may affect executive accounts; triangulation and document analysis mitigate but do not eliminate this risk. The longitudinal window captures early transformation, potentially under-representing late-stage scaling challenges.

3.11. Methodological Rigor Summary

Overall, the design integrates theoretical sampling, multi-source triangulation, systematic coding, cross-case synthesis, and reflexive practices to yield a credible, processual account of nonprofit transformation. The resulting evidence supports a staged model that connects entrepreneurial experimentation, professionalization, and legitimacy work.

Figure 1.

Research design overview: multiple-case logic, theoretical sampling, multi-source data collection, and structured inductive analysis leading to a staged process model.

Figure 1.

Research design overview: multiple-case logic, theoretical sampling, multi-source data collection, and structured inductive analysis leading to a staged process model.

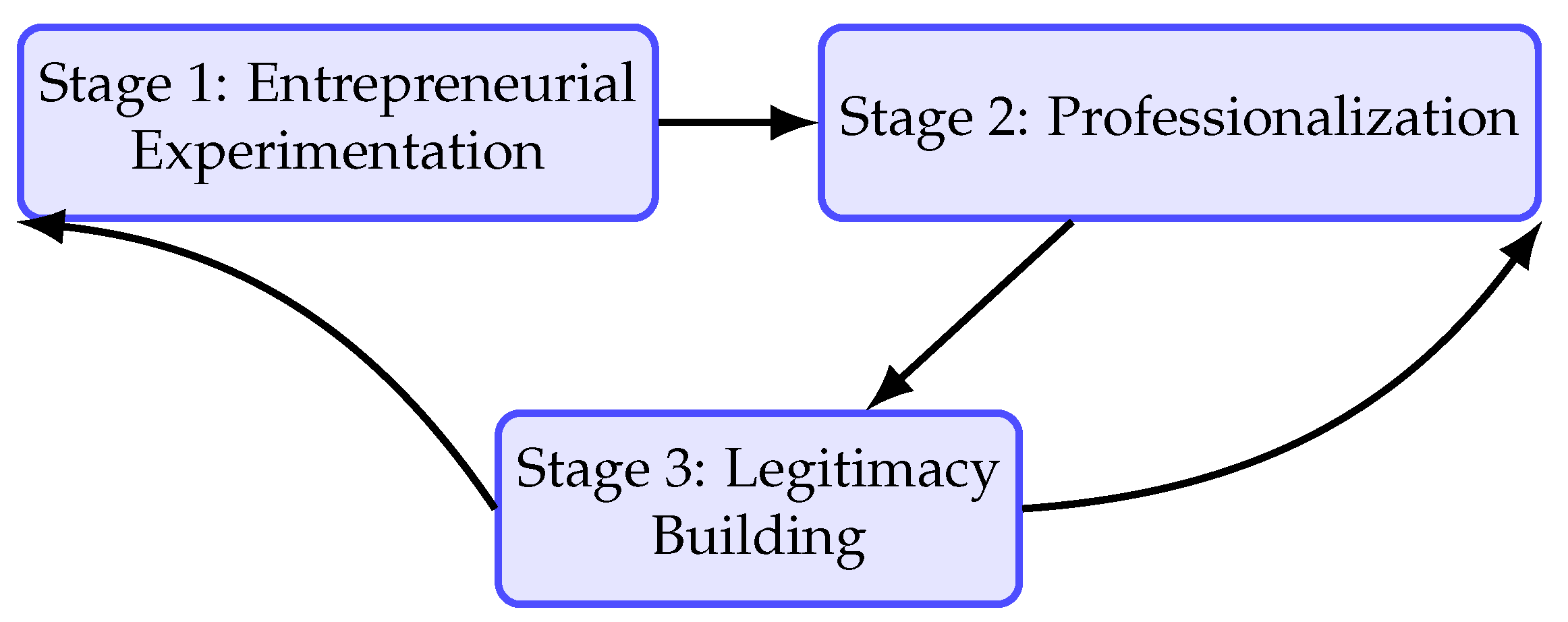

4. Findings: Stages of Transformation

The analysis of six focal nonprofit institutions (NPIs) and four auxiliary informants revealed a three-stage process through which organizations navigated transformation into social enterprises (SEs). These stages—entrepreneurial experimentation, professionalization, and legitimacy building—emerged inductively from interview narratives, documents, and observations. While sequential, the stages were often iterative and overlapping, with feedback loops shaping organizational trajectories. Below, we elaborate each stage with illustrative practices and mechanisms.

4.1. Stage 1: Entrepreneurial Experimentation

Organizations began their transformation journey by piloting entrepreneurial activities that supplemented or replaced declining grant income. Common practices included introducing fee-for-service models, launching social retail ventures, and establishing partnerships with private firms. For example, one health-focused nonprofit initiated a subscription-based wellness program, while an education-oriented charity developed training workshops for paying clients. These initiatives were framed as experiments, with leaders emphasizing the need to “test the waters” without fully committing resources.

Interviewees described entrepreneurial experimentation as high-risk but necessary, especially in an environment of resource scarcity. Leaders leveraged board networks and external consultants to design revenue pilots, often starting small to minimize exposure. Failure was not uncommon—several initiatives were discontinued after poor uptake—but learning was explicitly incorporated into subsequent trials. This stage was characterized by organizational agility, opportunism, and a willingness to depart from traditional nonprofit norms.

4.2. Stage 2: Professionalization

Once entrepreneurial activities demonstrated viability, nonprofits undertook professionalization to integrate these practices into organizational structures. Professionalization involved adopting formal management systems, financial controls, and performance metrics. For instance, one organization introduced customer-relationship management software to track paying clients, while another established a dedicated social enterprise unit within its governance structure.

Professionalization also encompassed capacity building. Staff were trained in marketing, sales, and financial literacy—skills historically peripheral to nonprofit work. Board committees were restructured to include members with business expertise, such as retired executives or accountants. This infusion of commercial competencies enabled nonprofits to manage their entrepreneurial ventures with greater rigor and accountability. Professionalization marked a cultural shift: organizations increasingly embraced business language and practices while continuing to articulate their social mission.

4.3. Stage 3: Legitimacy Building

The third stage centered on constructing legitimacy among stakeholders who might question the compatibility of commercial activities with social missions. Legitimacy-building efforts included transparent communication, impact reporting, and reinvestment narratives. For instance, organizations highlighted how profits from social ventures directly funded core services, thereby reframing commercialization as mission-enhancing rather than mission-drifting.

External recognition played a critical role. Certifications (e.g., Social Enterprise Mark), awards, and endorsements from government or philanthropic bodies provided symbolic validation. Leaders emphasized storytelling as a legitimacy strategy, sharing narratives of beneficiaries whose lives improved due to income from entrepreneurial activities. Importantly, legitimacy-building was not only directed outward but also inward—towards staff and volunteers who sometimes felt uneasy about the “corporatization” of their organizations.

4.4. Iterative and Overlapping Dynamics

Although entrepreneurial experimentation typically preceded professionalization and legitimacy-building, these stages were not strictly linear. Several organizations returned to experimentation after failed ventures, while legitimacy concerns often accelerated professionalization. For example, one nonprofit fast-tracked its impact measurement systems after donors questioned whether fee-based programs aligned with its mission. Thus, the transformation process was dynamic, recursive, and shaped by external pressures as much as internal choices.

4.5. Cross-Case Patterns

Comparative analysis revealed three cross-case patterns. First, leadership framing was pivotal: organizations where CEOs positioned commercialization as mission-aligned experienced smoother transitions. Second, board composition strongly influenced outcomes: boards with business-savvy members facilitated quicker professionalization. Third, stakeholder engagement moderated legitimacy challenges: nonprofits that proactively involved donors and beneficiaries in co-designing entrepreneurial initiatives encountered less resistance. These patterns underscore the interdependence of stages and the role of institutional work.

4.6. Illustrative Conceptual Model

The findings can be summarized in a process model that links entrepreneurial experimentation, professionalization, and legitimacy-building in a recursive cycle (

Figure 2). The model highlights both sequential flow and feedback loops, illustrating the dynamic nature of nonprofit transformation.

4.7. Summary of Practices

To further clarify the findings,

Table 1 summarizes the key practices identified at each stage.

5. Discussion and Implications

The findings of this study shed light on how nonprofit institutions (NPIs) navigate the complex transformation into social enterprises (SEs). By unpacking the three stages of entrepreneurial experimentation, professionalization, and legitimacy building, we extend existing scholarship on hybrid organizations and institutional entrepreneurship. This section discusses theoretical contributions, managerial implications, and policy relevance, while also considering broader societal debates about nonprofit commercialization.

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

Our study contributes to hybrid organization literature by presenting a staged, processual account of nonprofit transformation. Prior work has often portrayed hybridity as a static organizational form characterized by the coexistence of social and commercial logics [

22]. In contrast, we demonstrate that hybridity evolves through iterative experimentation, gradual professionalization, and contested legitimacy work. This dynamic, recursive model underscores the temporal dimension of nonprofit transformation, aligning with calls for more process-oriented theorizing in organizational studies [

23].

A second theoretical contribution lies in highlighting the role of institutional entrepreneurship. Leaders in our cases did not simply adopt commercial practices reactively; they actively reframed them as mission-aligned and mobilized resources to institutionalize them. This finding supports the argument that institutional entrepreneurs are not only opportunity exploiters but also meaning makers who reshape field-level understandings of what constitutes legitimate nonprofit practice [

8]. Thus, nonprofit transformation is not merely adaptation under pressure but a proactive act of institutional work.

5.2. Implications for Governance

From a governance perspective, the study illustrates that board composition and expertise are critical in mediating transformation outcomes. Boards with business-savvy members accelerated professionalization by introducing financial controls, CRM systems, and market-oriented strategies. However, these same boards had to engage in deliberate legitimacy work to assure stakeholders that commercialization was mission-enhancing. This dual role underscores the governance paradox of hybrid organizations: they must simultaneously adopt market discipline and preserve social legitimacy [

9].

5.3. Managerial Implications

For nonprofit leaders, the staged model offers actionable insights. In the entrepreneurial experimentation stage, leaders can treat new ventures as low-stakes pilots that foster organizational learning. In the professionalization stage, building commercial competencies while retaining social values is crucial to avoid mission drift. In the legitimacy stage, transparent communication, storytelling, and certifications provide assurance to stakeholders. The recursive nature of these stages suggests that leaders should embrace iteration, expecting failures and feedback loops rather than linear progress.

5.4. Stakeholder Engagement

Stakeholder engagement emerges as both a challenge and a solution. Beneficiaries, donors, and volunteers often view commercialization with suspicion, fearing that vulnerable populations may be excluded. Our findings indicate that organizations that co-designed entrepreneurial initiatives with stakeholders encountered less resistance and built stronger legitimacy. This reinforces the idea that stakeholder inclusion is not peripheral but central to the sustainability of hybrid organizations [

24].

5.5. Implications for Policymakers

For policymakers, the findings highlight the importance of supportive institutional environments. Regulatory frameworks, tax incentives, and accreditation schemes can lower the barriers to nonprofit transformation and help organizations signal legitimacy. For example, certification programs like the Social Enterprise Mark provide a standardized way for organizations to demonstrate their mission alignment while adopting commercial models. Policymakers can thus play an enabling role by institutionalizing pathways that legitimize hybridity.

5.6. Sectoral Implications

At the sectoral level, the study illustrates how nonprofit transformation contributes to the diversification of service provision. By blending social and market logics, SEs can complement public services, especially under conditions of austerity and welfare retrenchment. However, this diversification raises questions about equity: to what extent do market-oriented nonprofits risk excluding those unable to pay? The legitimacy stage provides a partial safeguard, but structural inequalities may persist. Addressing these concerns requires sector-wide dialogue on balancing sustainability with inclusivity.

5.7. Ethical and Normative Considerations

The commercialization of nonprofits is not value-neutral. Critics argue that marketization risks undermining the solidarity, voluntarism, and inclusivity that traditionally define the sector [

10]. Our study does not resolve this debate but shows how organizations actively negotiate these tensions through legitimacy-building practices. Ethical dilemmas are integral to nonprofit transformation and require ongoing reflexivity. This highlights the need for hybrid organizations to institutionalize ethical deliberation alongside managerial professionalism.

5.8. Policy-Practice Gaps

One striking observation is the gap between policy rhetoric and organizational practice. While governments often champion social enterprise as a panacea for public-sector austerity, our cases reveal the micro-level struggles and risks inherent in transformation. Policymakers should temper expectations and acknowledge that building sustainable hybrids requires time, experimentation, and institutional support. Without such recognition, the burden of innovation may unfairly fall on under-resourced nonprofits.

5.9. Resilience and Adaptation

The recursive, iterative nature of nonprofit transformation underscores organizational resilience. The ability to pivot after failed ventures, reframe commercial activities as mission-aligned, and professionalize structures under pressure reflects remarkable adaptive capacity. This resilience challenges deficit-based narratives that portray nonprofits as passive victims of austerity. Instead, nonprofits emerge as entrepreneurial actors capable of innovation and institutional change.

5.10. Contribution to Broader Debates

Our findings contribute to broader debates about the role of markets in addressing social challenges. By illustrating how nonprofits selectively integrate commercial practices, the study provides a middle ground between critics who fear mission drift and advocates who celebrate entrepreneurialism. The staged model shows that commercialization is not inherently harmful or beneficial; its outcomes depend on leadership framing, governance structures, and stakeholder engagement.

5.11. Implications for Future Theory Development

The study also points toward future theoretical development. The recursive model of nonprofit transformation invites integration with theories of organizational learning, resource dependence, and paradox management. Exploring how nonprofits manage competing logics over time could enrich theorizations of hybrid organizations. Comparative research across national contexts would further illuminate how institutional environments condition transformation processes.

5.12. Summary

In sum, this discussion situates the empirical findings within theoretical, managerial, and policy debates. By framing nonprofit transformation as a staged yet iterative process of experimentation, professionalization, and legitimacy building, the study contributes to hybrid organization and institutional entrepreneurship literatures. It also offers practical insights for leaders and policymakers navigating the uncertain terrain of nonprofit commercialization.

6. Conclusion and Future Directions

This study has examined how nonprofit institutions (NPIs) in the United Kingdom evolve into social enterprises (SEs) through a staged process of entrepreneurial experimentation, professionalization, and legitimacy building. Drawing on six in-depth case studies, the findings highlight the recursive and iterative nature of nonprofit transformation. Rather than a linear journey, transformation emerged as a dynamic process shaped by leadership framing, governance structures, and stakeholder engagement.

6.1. Contributions to Theory

The research contributes to hybrid organization and institutional entrepreneurship literatures by presenting a process model that foregrounds temporal sequencing and feedback loops. Previous studies often portrayed hybridity as a fixed structural arrangement [

22], but our findings show how hybrid identities are actively constructed and reconstructed over time. This aligns with calls for more dynamic theorization of hybrid organizations [

23] and situates nonprofit leaders as institutional entrepreneurs engaged in meaning-making and legitimacy work [

8].

6.2. Contributions to Practice

For practitioners, the staged model offers a roadmap for navigating nonprofit transformation. Leaders can use entrepreneurial experimentation to test revenue models while mitigating risk, professionalization to embed commercial practices with accountability, and legitimacy-building to sustain stakeholder trust. By recognizing the recursive nature of the process, practitioners can anticipate the likelihood of setbacks and prepare for adaptive responses. Importantly, the model underscores that commercialization need not imply mission drift if it is transparently framed as mission-enhancing.

6.3. Contributions to Policy

For policymakers, the findings reinforce the importance of creating enabling environments for nonprofit transformation. Accreditation schemes, fiscal incentives, and technical support can reduce the risks associated with entrepreneurial initiatives. Policymakers should recognize that transformation is not instantaneous but requires iterative learning, professionalization, and legitimacy work. By providing stable institutional scaffolding, governments and intermediaries can support nonprofits in developing sustainable hybrid forms.

6.4. Broader Societal Implications

The commercialization of nonprofits raises fundamental questions about equity, inclusivity, and the role of markets in addressing social problems. Our study shows how legitimacy practices partially address these tensions, but broader societal debates remain unresolved. The findings highlight the need for ongoing ethical reflection within organizations and sector-wide dialogue about balancing financial sustainability with social justice. Future nonprofit evolution will depend not only on organizational strategies but also on collective deliberations about the values underpinning social innovation.

6.5. Limitations of the Study

While the study provides rich qualitative insights, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the cases are limited to the UK context, where policy frameworks and funding dynamics differ from other regions. Transferability to contexts such as Continental Europe, North America, or the Global South should be approached cautiously. Second, the study captures early and mid-stage transformations but provides limited evidence on long-term scaling outcomes. Third, as with most qualitative studies, self-report bias is possible, although triangulation and document analysis mitigated this risk.

6.6. Avenues for Future Research

Future research can build on these findings in several ways. Cross-national comparative studies would illuminate how institutional environments condition nonprofit transformation. Longitudinal research could trace how hybrids sustain legitimacy over time and manage tensions between social and market logics in later stages of growth. Quantitative studies could test hypotheses about the relationships between board composition, stakeholder engagement, and transformation success. Experimental or quasi-experimental designs might explore how policy interventions (e.g., subsidies, certifications) affect nonprofit commercialization trajectories.

6.7. Technology and Digital Transformation

Another promising avenue is the role of digital technologies in nonprofit evolution. Emerging evidence suggests that digital fundraising platforms, data analytics, and online service delivery reshape the resource environment of nonprofits [

25]. Investigating how digital tools intersect with entrepreneurial experimentation, professionalization, and legitimacy-building could expand the model presented here.

6.8. Intersection with Social Finance

The rise of impact investing and blended finance opens further research opportunities. How do nonprofits negotiate with investors who expect financial returns alongside social impact? Future work could examine the tensions and synergies between philanthropic capital, government grants, and private investment, and how these funding sources shape organizational transformation. The financial dimension is likely to become increasingly important as nonprofits pursue sustainability in competitive environments.

6.9. Global South Perspectives

The experiences of nonprofits in the Global South remain underexplored in hybrid organization research. Contexts characterized by resource scarcity, weaker regulatory systems, and informal economies may produce distinct transformation pathways. Studying these contexts could challenge assumptions derived from Global North cases and enrich theoretical understanding of nonprofit hybridity.

6.10. Contribution to Organizational Learning Theory

The recursive model of nonprofit transformation also invites integration with organizational learning theory. Failures in entrepreneurial experimentation often catalyzed adaptive learning, while professionalization institutionalized lessons into formal structures. Legitimacy-building practices reinforced organizational memory by codifying narratives of mission alignment. Future research could deepen this intersection by examining the micro-processes of learning in hybrid organizations.

6.11. Toward a Holistic Research Agenda

Taken together, these future directions call for a more holistic, multi-disciplinary approach to studying nonprofit evolution. Insights from organizational studies, public policy, ethics, finance, and information systems could be integrated to build a richer understanding of how nonprofits navigate transformation. Such cross-disciplinary research would better capture the complexity and dynamism of nonprofit innovation in practice.

6.12. Closing Reflection

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that nonprofit transformation into social enterprise is neither linear nor uniform. It is a recursive, staged process shaped by entrepreneurial experimentation, professionalization, and legitimacy-building. By situating nonprofits as active institutional entrepreneurs, we highlight their capacity for resilience and innovation in resource-constrained environments. The findings not only advance academic debates but also provide practical guidance for leaders and policymakers striving to balance sustainability with social mission. Future research that expands, contextualizes, and diversifies these insights will be vital for supporting the continued evolution of the nonprofit sector.