Submitted:

23 December 2025

Posted:

24 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

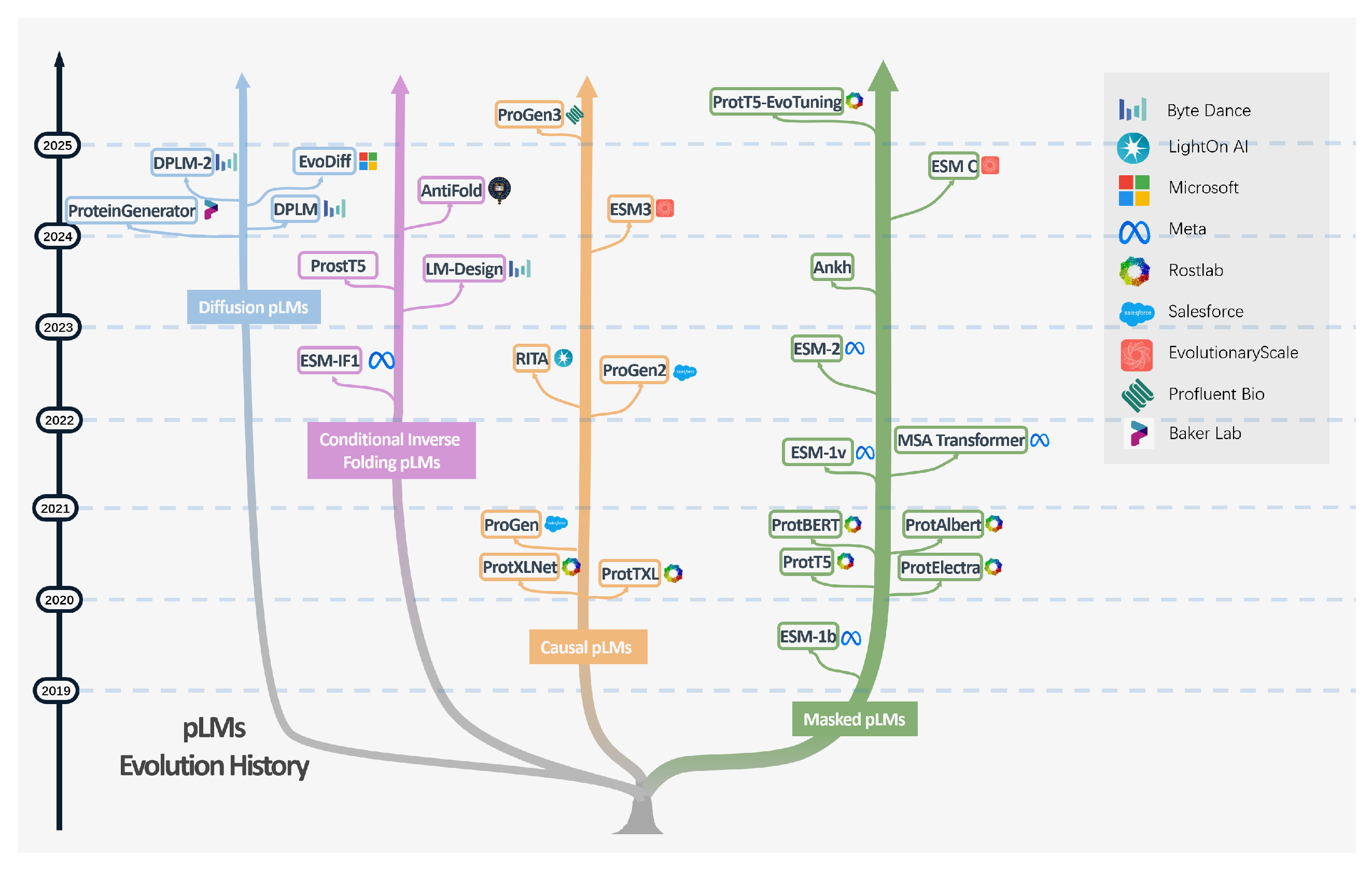

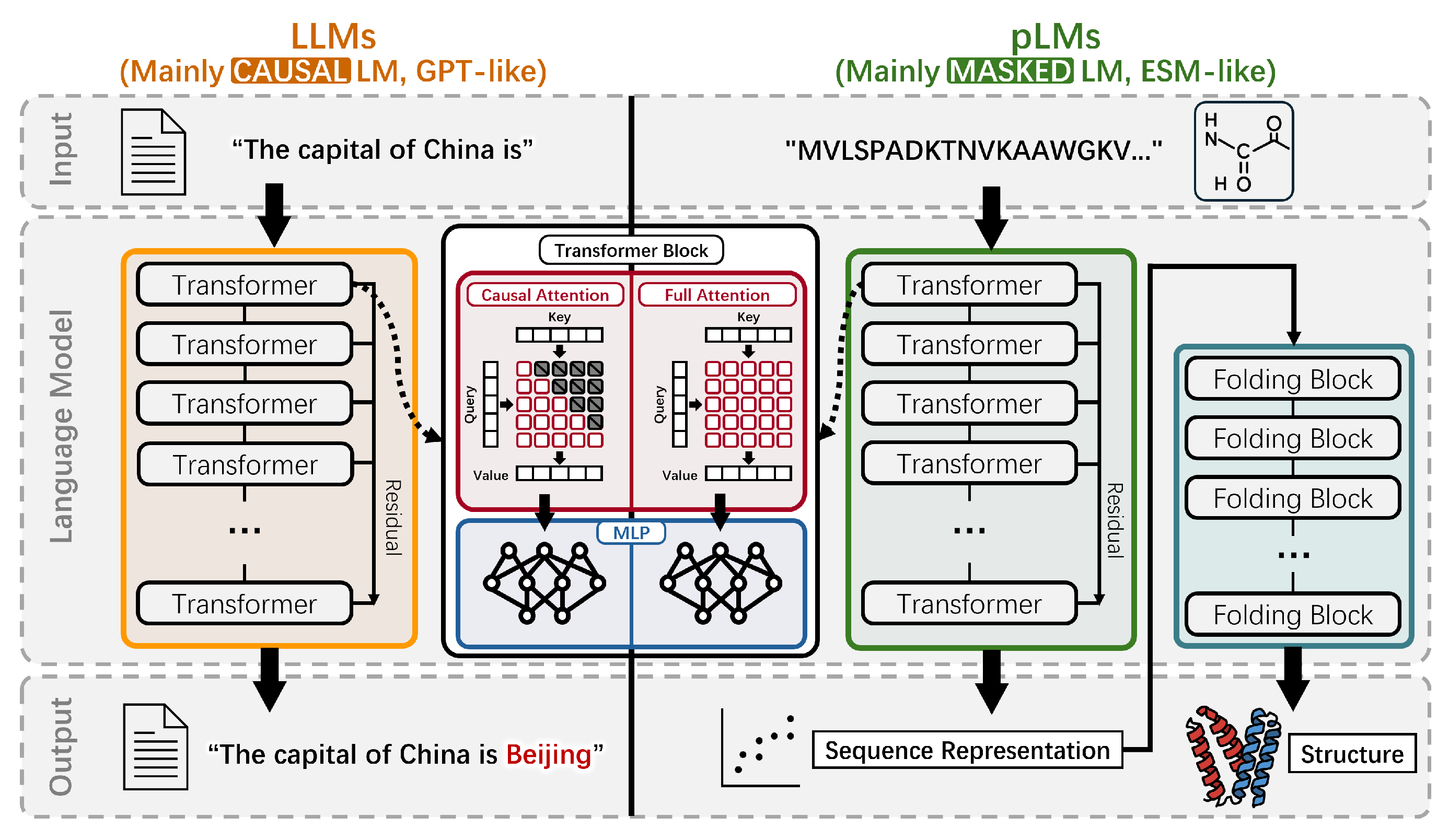

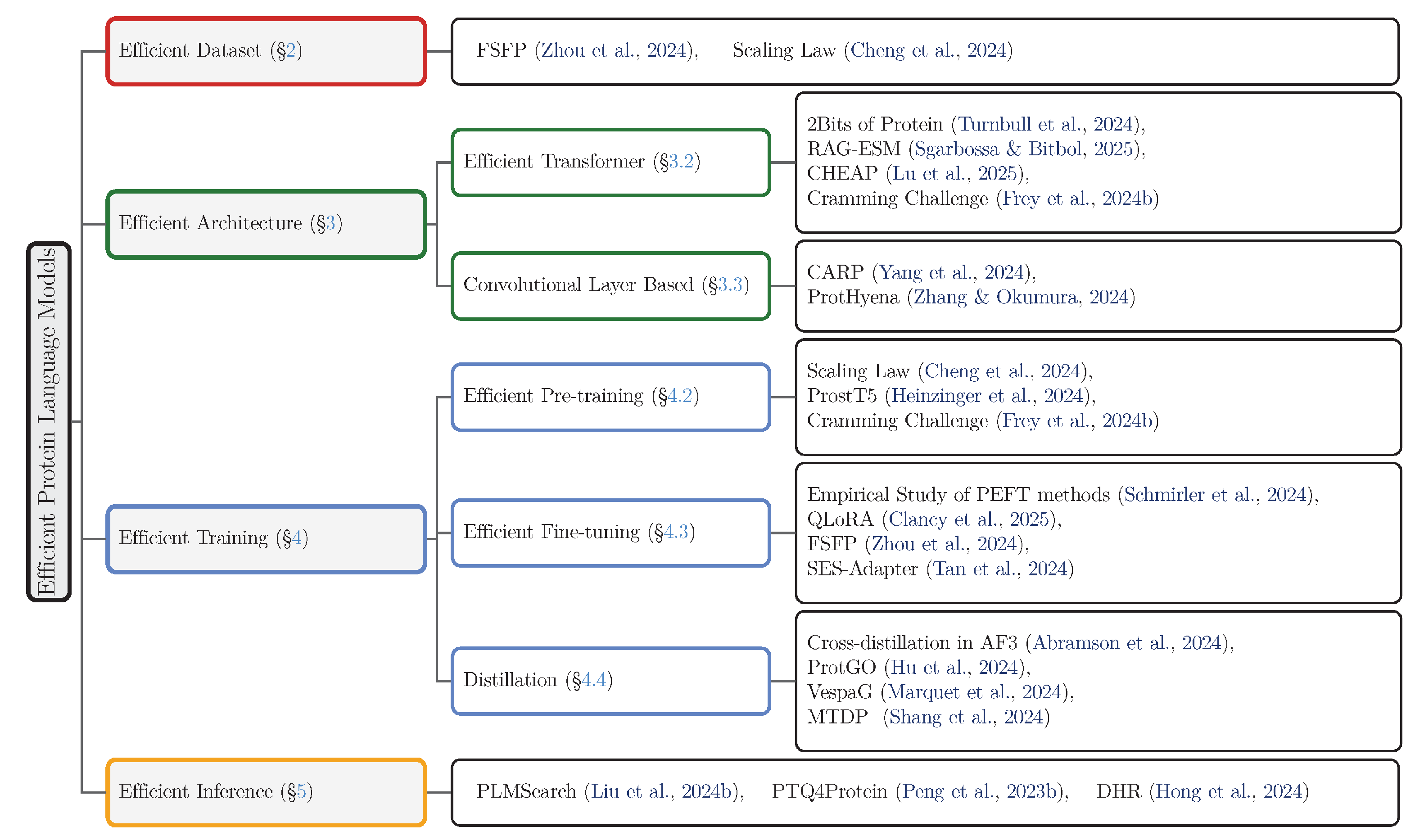

1. Introduction

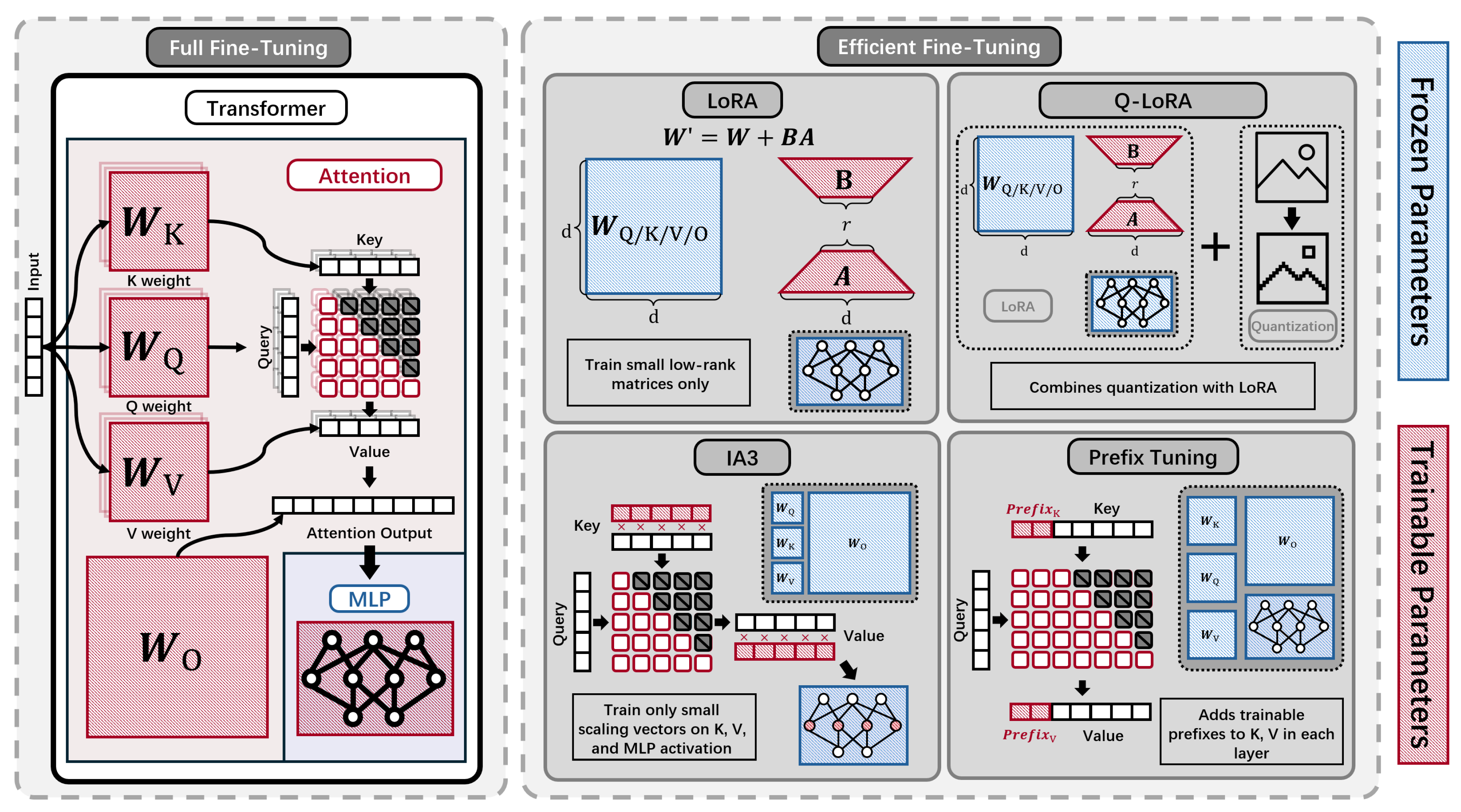

- Training Efficiency: Optimizing the training procedures, including computational resource allocation guided by scaling laws [21], efficient fine-tuning techniques [22,30,31], and knowledge distillation [39] approaches that transfer knowledge from larger, teacher models to compact, efficient student models [33,34,35,36].

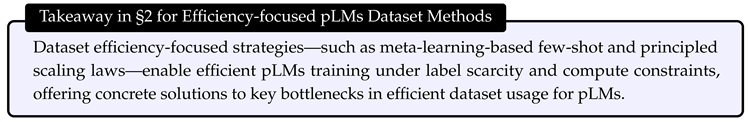

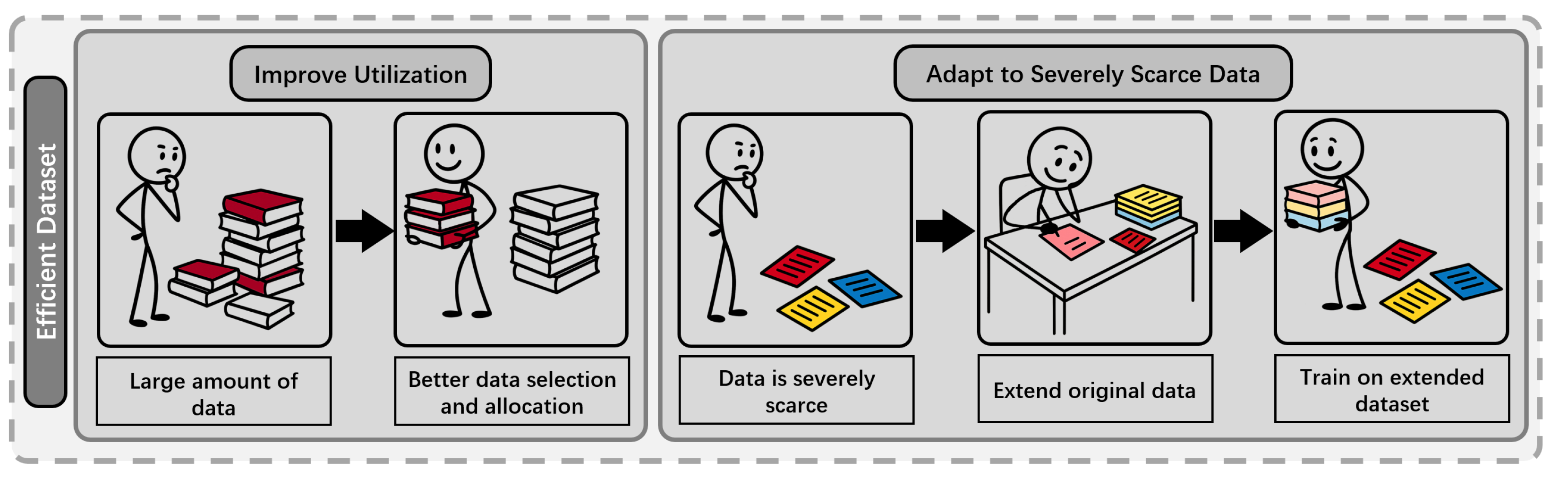

2. Datasets for Efficient pLMs

2.1. Background and Challenges

- Paucity of Labeled Data: A critical bottleneck in many real-world applications, such as protein engineering and A field of molecular biology that aims to understand the function of genes and proteins, often at a genome-wide scale. (functional genomics), is the extreme scarcity of experimentally validated labels. Often, only a few dozen labeled protein variants are available, posing a fundamental impediment to traditional supervised fine-tuning and demanding highly data-efficient adaptation methods [22].

- Absence of Principled Scaling Guidelines: Given a finite computational-budget, determining the optimal allocation between model parameter count and training data volume remains a significant challenge. An unprincipled approach, such as aggressively scaling model size while repeatedly cycling through a small dataset, can lead to suboptimal training dynamics, including premature convergence, overfitting, and a failure to capitalize on the model’s architectural capacity [21].

2.2. Efficient Dataset Methods

- Meta-Learning: These auxiliary tasks are used for meta-training via MAML [58], equipping the pLM for rapid adaptation.

- Parameter-Efficient Adaptation: To prevent overfitting under few-shot settings [59], FSFP freezes the backbone pLM and trains LoRA [41] parameters during meta-training and when transferring to target task; meta-learning yields a better initialization of the LoRA parameters, and the subsequent adaptation continues to update these parameters.

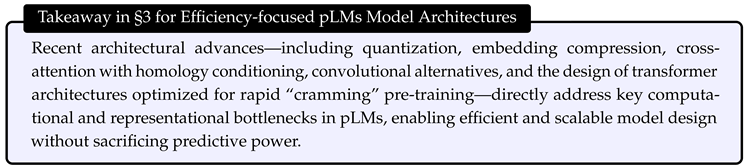

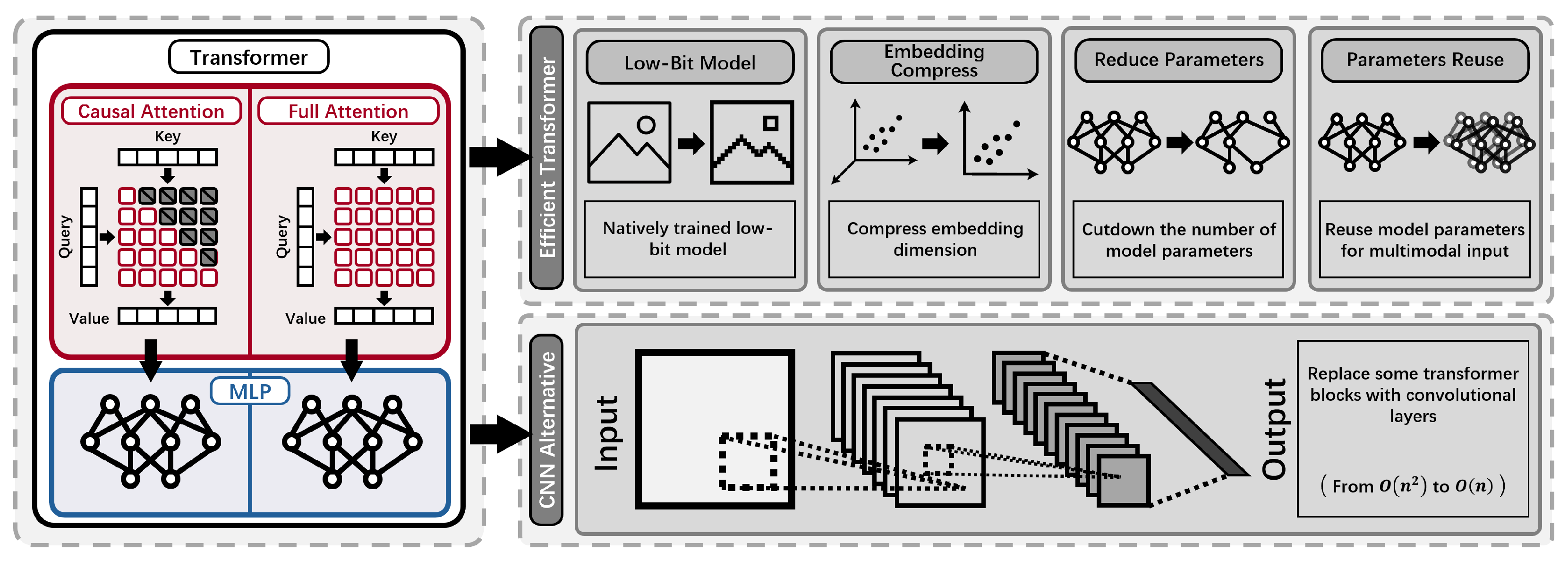

3. Efficient Architecture

3.1. Background and Challenges

- High Computational and Memory Cost: Standard transformer-based pLMs require quadratic time and memory with respect to sequence length, leading to prohibitive resource demands for long proteins or large models. The use of full-precision weights and high-dimensional embeddings further increases GPU and energy costs, particularly during large-scale training and deployment [1,5,24,26,27].

- Redundancy and Massive Activations in Embeddings: Protein embeddings in large models are highly compressible, indicating over-parameterization, and also exhibit massive activations in certain channels, leading to inefficient memory use [26].

- Limited Inductive Bias and Information Integration: Existing architectures may not efficiently leverage important biological information, such as evolutionary relationships or sequence homology, constraining their performance and flexibility in specialized tasks [25].

3.2. Efficient Transformer

- Continuous Compression: CHEAP enables up to channel compression and sequence length compression through a learnable bottleneck, allowing backbone structure reconstruction with less than Å root-mean-squared distance [85] at channel compression, and maintaining sequence recovery above until fewer than 8 channels remain. To address abnormal massive activations in certain embedding channels, CHEAP introduces per-channel normalization [86,87], further improving compressibility.

3.3. Convolutional Layer Based Methods

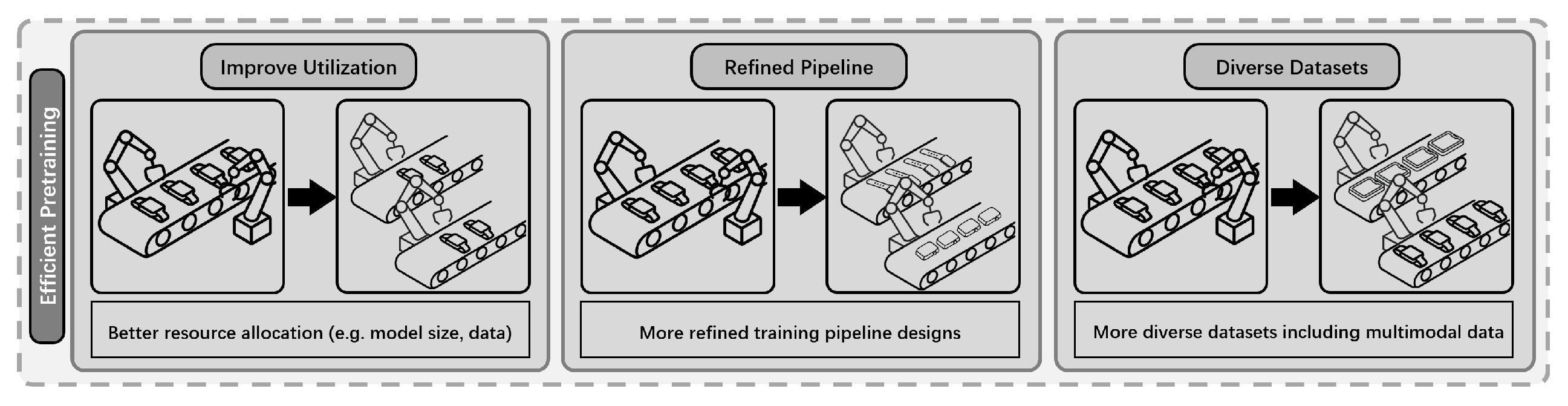

4. Efficient Training

4.1. Background and Challenges

-

Challenges in Pre-training:

- -

- -

- Limited Structural Integration: Most pre-training pipelines rely solely on sequence data, whereas structural information remains underutilized, which may ultimately limit both the efficiency and generalization capabilities of the models [29].

-

Challenges in Fine-tuning:

- -

- -

- -

- Low Data Efficiency: Adapting models to new tasks with limited labeled data can be inefficient, as conventional fine-tuning is prone to overfitting and resource waste [22].

-

Challenges in Distillation:

- -

- -

4.2. Efficient Pre-Training Methods

| Category | Method | Brief Description |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-training | Scaling Law [21] | Empirical study on pLMs optimal data/model allocation. |

| Structure Integration [29] | Joint sequence-structure pre-training (e.g., ProstT5). | |

| Cramming Challenge [23] | Train a performant pLM in 24 hours on a single GPU. | |

| Fine-tuning | A study of PEFT Methods [30] | LoRA for parameter-efficient tuning. |

| QLoRA [31] | 4-bit quantization + LoRA for efficient fine-tuning. | |

| SES-Adapter [32] | Structure-aware adapters for cross-modal representation. | |

| FSFP [22] | few-shot with meta-learning and LoRA. | |

| Distillation | Cross-distillation in AlphaFold3 [33] | Distillation from a single large teacher-model. |

| ProtGO [34] | Transferring functional and structural knowledge. | |

| VespaG [35] | Distillation via evolutionary expert supervision. | |

| MTDP [36] | Aggregating knowledge from multiple teacher models. |

- Multimodal Pre-training: By encoding 3D structures from AlphaFoldDB [124] as 3Di-token sequences, and expanding the vocabulary with 3Di tokens, ProstT5 applies span-based denoising objectives to both AA and 3Di sequences, teaching the model new structural tokens while avoiding catastrophic forgetting of sequence information.

- Bi-directional Translation Objectives: ProstT5 is trained to translate between AA and 3Di representations using direction tags (<fold2AA>, <AA2fold>), enabling both “folding” (AA→3Di) and “inverse folding” (3Di→AA), thus robustly linking sequence and structure information.

- Random initialization: All model weights are initialized randomly.

- On-the-fly masked language modeling: Masked language modeling is performed directly on UniRef50 [12] splits, with all data processing (e.g., tokenization, filtering, sorting) occurring on-the-fly during training, and no offline pre-processing.

- Large effective batch size: Training employs a batch size of 128, sequence length of 512, and gradients are accumulated over 16 steps for an effective batch of 2048 sequences.

- Critical hyperparameter tuning: The optimizer is AdamW [128] with carefully tuned parameters. The learning rate schedule is central: the optimal regime employs a fast warmup [129,130] to a peak learning rate of over 1,000 steps, followed by a slow linear decay [131] to near zero over the remaining steps, with training capped at 50,000 updates.

4.3. Efficient Fine-Tuning Methods

- Efficiency and accuracy: By freezing most model weights and only updating a small fraction (e.g., 0.25% for LoRA), PEFT methods, such as LoRA, achieved nearly equivalent accuracy to full fine-tuning.

- Training speedup and memory savings: For larger models, LoRA offered up to a 4.5× training speedup with comparable GPU memory requirements, and required saving only adapter weights, further improving efficiency.

- Compatibility and resource efficiency: LoRA, DoRA, and similar methods are compatible with mixed precision, gradient accumulation, and CPU-offloading, enabling fine-tuning even on 8GB or 16GB GPUs.

- Method comparison: Among PEFT methods, LoRA was generally most compute-efficient for large pLMs, with DoRA sometimes up to 30% slower, and all PEFT methods yielded average prediction gains of 61.3% compared to using static embeddings.

4.4. Efficient Training via Distillation

- Joint supervision with ground-truth and teacher outputs: AlphaFold 3 is explicitly optimized to align its outputs not only with experimental ground-truth structures, but also with reliable teacher-generated structures. This enables the model to learn more physically realistic disorder regions, as teacher-generated structures tend to represent unstructured segments as extended loops, reducing hallucinated compact order in intrinsically disordered regions.

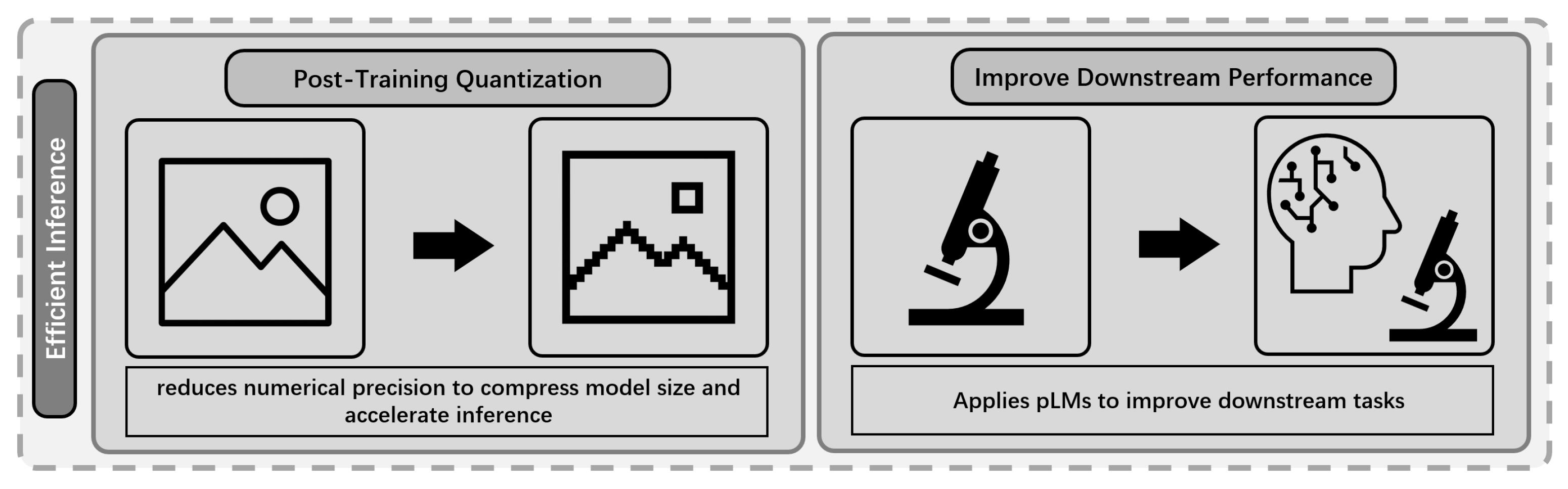

5. Efficient Inference

5.1. Background and Challenges

- Resource Constraints: The inference process of large pLMs require substantial computation and memory, hindering deployment in resource-limited settings [38].

- Inference Latency: Traditional alignment-based and MSA methods are inherently slow and cannot efficiently scale to large databases, which is critical for many practical applications, such as proteome-wide A bioinformatics method used to identify sequences with a shared evolutionary ancestry, typically by comparing a query sequence against a database. (homology search) [20,37].

5.2. Efficient Inference

- PfamClan-based pre-filtering: PfamClan [168] assigns proteins to evolutionarily related superfamilies (clans); this stage retains only protein pairs sharing the same clan, ensuring high recall while greatly reducing the candidate search space.

- SS-predictor: A bilinear neural network is trained to predict structural similarity (TM-score [169]) between protein pairs based on pLM embeddings; it integrates predicted TM-scores with cosine similarity, capturing global and local sequence features for remote homolog detection.

- PLMAlign: For top-scoring pairs, per-residue alignment is performed using pLM embeddings to refine hit precision and enhance biological relevance.

- Dual-encoder architecture: Both query and candidate sequences are embedded into dense vectors using a pair of ESM-initialized encoders, allowing alignment-free similarity calculation.

- Contrastive learning: The dual-encoders are trained to embed homologous pairs close together and nonhomologous pairs far apart, enabling effective discrimination via dot-product scoring.

6. Future Directions

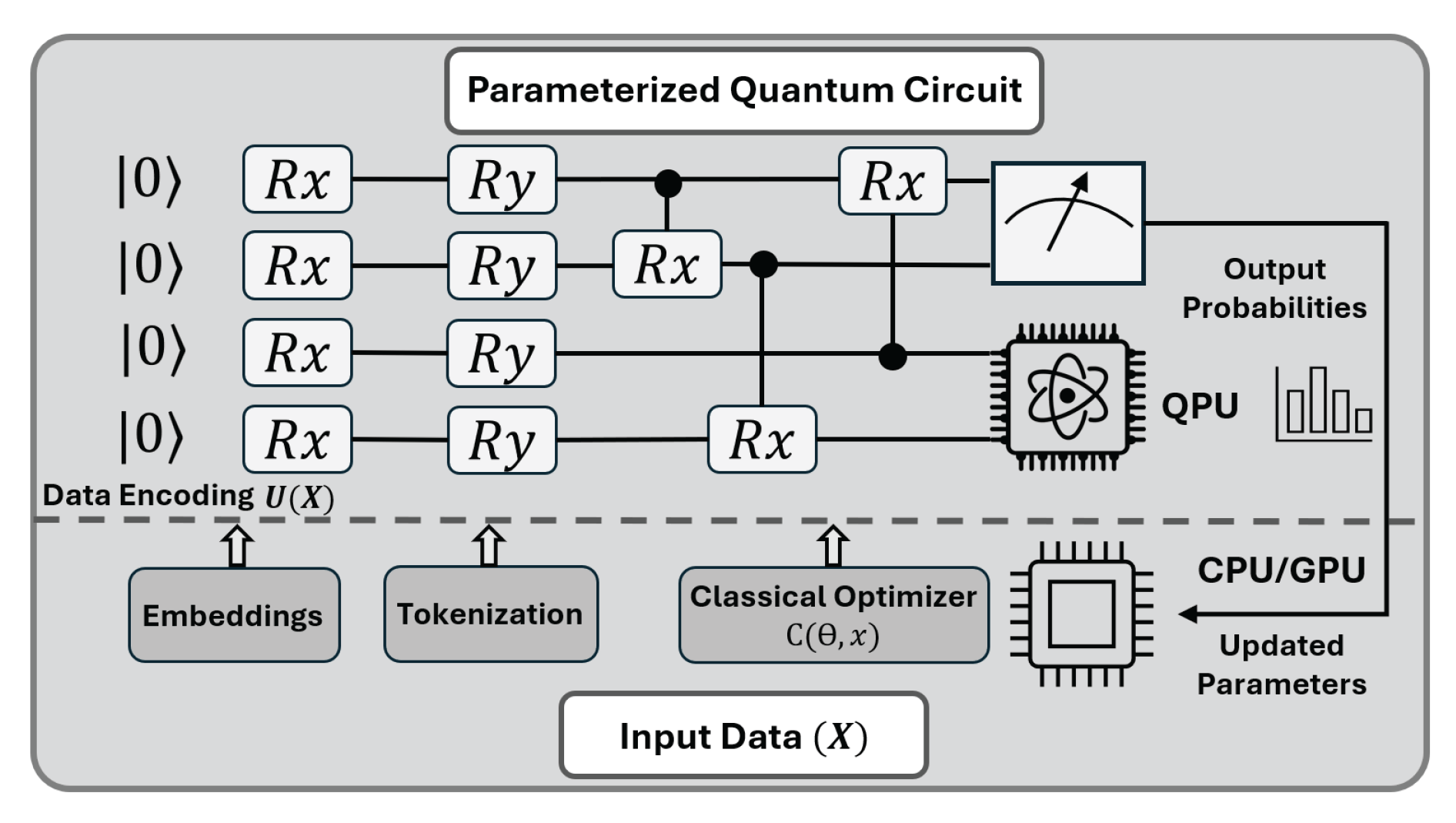

Quantum Algorithms for Protein Structure Prediction

Hybrid quantum–classical Transformers as a path toward quantum PLMs.

7. Conclusions

References

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 conference of the North American chapter of the association for computational linguistics: human language technologies 2019, volume 1 (long and short papers), 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Bepler, T.; Berger, B. Learning protein sequence embeddings using information from structure. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1902.08661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgari, E.; Mofrad, M.R. Continuous distributed representation of biological sequences for deep proteomics and genomics. PloS one 2015, 10, e0141287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rives, A.; Meier, J.; Sercu, T.; Goyal, S.; Lin, Z.; Liu, J.; Guo, D.; Ott, M.; Zitnick, C.L.; Ma, J.; et al. Biological structure and function emerge from scaling unsupervised learning to 250 million protein sequences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2021, 118, e2016239118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elnaggar, A.; Heinzinger, M.; Dallago, C.; Rehawi, G.; Wang, Y.; Jones, L.; Gibbs, T.; Feher, T.; Angerer, C.; Steinegger, M.; et al. Prottrans: Toward understanding the language of life through self-supervised learning. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2021, 44, 7112–7127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Akin, H.; Rao, R.; Hie, B.; Zhu, Z.; Lu, W.; Smetanin, N.; Verkuil, R.; Kabeli, O.; Shmueli, Y.; et al. Evolutionary-scale prediction of atomic-level protein structure with a language model. Science 2023, 379, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.X.; Liang, F.; Xia, Y.H.; Zhao, K.L.; Hou, M.H.; Zhang, G.J. Recent advances and challenges in protein structure prediction. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2023, 64, 76–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, J.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ren, Z.; Sun, R.; Wang, H.; Wan, G.; Lu, P.; et al. Protein large language models: A comprehensive survey. arXiv arXiv:2502.17504. [CrossRef]

- Burley, S.K.; Bhikadiya, C.; Bi, C.; Bittrich, S.; Chen, L.; Crichlow, G.V.; Christie, C.H.; Dalenberg, K.; Di Costanzo, L.; Duarte, J.M.; et al. RCSB Protein Data Bank: powerful new tools for exploring 3D structures of biological macromolecules for basic and applied research and education in fundamental biology, biomedicine, biotechnology, bioengineering and energy sciences. Nucleic acids research 2021, 49, D437–D451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consortium, T.U. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase in 2021. Nucleic acids research 2021, 49, D480–D489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzek, B.E.; Wang, Y.; Huang, H.; McGarvey, P.B.; Wu, C.H.; Consortium, U. UniRef clusters: a comprehensive and scalable alternative for improving sequence similarity searches. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 926–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ofer, D.; Brandes, N.; Linial, M. The language of proteins: NLP, machine learning & protein sequences. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 2021, 19, 1750–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferruz, N.; Schmidt, S.; Höcker, B. ProtGPT2 is a deep unsupervised language model for protein design. Nature communications 2022, 13, 4348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, J.; Roth, S.; Arnold, K.; Kiefer, F.; Schmidt, T.; Bordoli, L.; Schwede, T. The Protein Model Portal—a comprehensive resource for protein structure and model information. Database 2013, 2013, bat031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kryshtafovych, A.; Schwede, T.; Topf, M.; Fidelis, K.; Moult, J. Critical assessment of methods of protein structure prediction (CASP)—Round XIV. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics 2021, 89, 1607–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strubell, E.; Ganesh, A.; McCallum, A. Energy and Policy Considerations for Deep Learning in NLP. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.02243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strubell, E.; Ganesh, A.; McCallum, A. Energy and policy considerations for modern deep learning research. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence 2020, Vol. 34, 13693–13696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, J.; McCandlish, S.; Henighan, T.; Brown, T.B.; Chess, B.; Child, R.; Gray, S.; Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Amodei, D. Scaling laws for neural language models. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2001.08361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, L.; Hu, Z.; Sun, S.; Tang, X.; Wang, J.; Tan, Q.; Zheng, L.; Wang, S.; Xu, S.; King, I.; et al. Fast, sensitive detection of protein homologs using deep dense retrieval. Nature Biotechnology 2024, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Chen, B.; Li, P.; Gong, J.; Tang, J.; Song, L. Training compute-optimal protein language models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 37, 69386–69418. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Y.; Wu, B.; Li, M.; Hong, L.; Tan, P. Enhancing efficiency of protein language models with minimal wet-lab data through few-shot learning. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 5566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, N.C.; Joren, T.; Ismail, A.A.; Goodman, A.; Bonneau, R.; Cho, K.; Gligorijević, V. Cramming Protein Language Model Training in 24 GPU Hours. bioRxiv 2024, 2024–05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, O.M.; Baioumy, M.; Deane, C. 2Bits of Protein: Efficient Protein Language Models at the Scale of 2-bits. In Proceedings of the ICML 2024 Workshop on Efficient and Accessible Foundation Models for Biological Discovery, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sgarbossa, D.; Bitbol, A.F. RAG-ESM: Improving pretrained protein language models via sequence retrieval. bioRxiv 2025, 2025–04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, A.X.; Yan, W.; Yang, K.K.; Gligorijevic, V.; Cho, K.; Abbeel, P.; Bonneau, R.; Frey, N.C. Tokenized and continuous embedding compressions of protein sequence and structure. Patterns 2025, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.K.; Fusi, N.; Lu, A.X. Convolutions are competitive with transformers for protein sequence pretraining. Cell Systems 2024, 15, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Okumura, M. Prothyena: A fast and efficient foundation protein language model at single amino acid resolution. bioRxiv 2024, 2024–01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinzinger, M.; Weissenow, K.; Sanchez, J.G.; Henkel, A.; Mirdita, M.; Steinegger, M.; Rost, B. Bilingual language model for protein sequence and structure. NAR Genomics and Bioinformatics 2024, 6, lqae150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmirler, R.; Heinzinger, M.; Rost, B. Fine-tuning protein language models boosts predictions across diverse tasks. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 7407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, S.; Zeisler, I.Y.; Bayat, P.; Xie, M.; White, V.; Perkins, S.; Bayat, S.; Pardee, K. Assessing Quantization and Efficient Fine-Tuning for Protein Language Models. In Proceedings of the ICLR 2025 Workshop on Generative and Experimental Perspectives for Biomolecular Design, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Y.; Li, M.; Zhou, B.; Zhong, B.; Zheng, L.; Tan, P.; Zhou, Z.; Yu, H.; Fan, G.; Hong, L. Simple, efficient, and scalable structure-aware adapter boosts protein language models. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2024, 64, 6338–6349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, B.; Tan, C.; Xu, Y.; Gao, Z.; Xia, J.; Wu, L.; Li, S.Z. Protgo: Function-guided protein modeling for unified representation learning. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 37, 88581–88604. [Google Scholar]

- Marquet, C.; Schlensok, J.; Abakarova, M.; Rost, B.; Laine, E. Expert-guided protein language models enable accurate and blazingly fast fitness prediction. Bioinformatics 2024, 40, btae621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Peng, C.; Ji, Y.; Guan, J.; Cai, D.; Tang, X.; Sun, Y. Accurate and efficient protein embedding using multi-teacher distillation learning. Bioinformatics 2024, 40, btae567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, Z.; You, R.; Xie, C.; Wei, H.; Xiong, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhu, S. PLMSearch: Protein language model powers accurate and fast sequence search for remote homology. Nature communications 2024, 15, 2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Yang, F.; Sun, N.; Chen, S.; Jiang, Y.; Pan, A. Exploring Post-Training Quantization of Protein Language Models. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), 2023; IEEE; pp. 602–608. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton, G.; Vinyals, O.; Dean, J. Distilling the knowledge in a neural network. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1503.02531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Huang, Y.; Lin, H.; Li, S.Z. A survey on protein representation learning: Retrospect and prospect. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2301.00813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, W.; et al. Lora: Low-rank adaptation of large language models. ICLR 2022, 1, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, J.; McCandlish, S.; Henighan, T.; Brown, T.B.; Chess, B.; Child, R.; Gray, S.; Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Amodei, D. Scaling laws for neural language models. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2001.08361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Narasimhan, K.; Salimans, T.; Sutskever, I.; et al. Improving language understanding by generative pre-training. Advances in neural information processing systems; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in neural information processing systems 2020, 33, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Sennrich, R.; Haddow, B.; Birch, A. Neural machine translation of rare words with subword units. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1508.07909. [Google Scholar]

- Kudo, T.; Richardson, J. SentencePiece: A simple and language independent subword tokenizer and detokenizer for neural text processing. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1808.06226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.L.; Almeida, A.; Beracochea, M.; Boland, M.; Burgin, J.; Cochrane, G.; Crusoe, M.R.; Kale, V.; Potter, S.C.; Richardson, L.J.; et al. MGnify: the microbiome analysis resource in 2020. Nucleic acids research 2020, 48, D570–D578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, J.; Borgeaud, S.; Mensch, A.; Buchatskaya, E.; Cai, T.; Rutherford, E.; Casas, D.d.L.; Hendricks, L.A.; Welbl, J.; Clark, A.; et al. Training compute-optimal large language models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.15556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffel, C.; Shazeer, N.; Roberts, A.; Lee, K.; Narang, S.; Matena, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, P.J. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. Journal of machine learning research 2020, 21, 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, P.A.; Krause, A.; Arnold, F.H. Navigating the protein fitness landscape with Gaussian processes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2013, 110, E193–E201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Qin, T.; Liu, T.Y.; Tsai, M.F.; Li, H. Learning to rank: from pairwise approach to listwise approach. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 24th international conference on Machine learning, 2007; pp. 129–136. [Google Scholar]

- Buller, A.R.; Van Roye, P.; Cahn, J.K.; Scheele, R.A.; Herger, M.; Arnold, F.H. Directed evolution mimics allosteric activation by stepwise tuning of the conformational ensemble. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2018, 140, 7256–7266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowler, D.M.; Fields, S. Deep mutational scanning: a new style of protein science. Nature methods 2014, 11, 801–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melamed, D.; Young, D.L.; Gamble, C.E.; Miller, C.R.; Fields, S. Deep mutational scanning of an RRM domain of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae poly (A)-binding protein. Rna 2013, 19, 1537–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laine, E.; Karami, Y.; Carbone, A. GEMME: a simple and fast global epistatic model predicting mutational effects. Molecular biology and evolution 2019, 36, 2604–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.D.; Higgins, D.G.; Gibson, T.J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic acids research 1994, 22, 4673–4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirdita, M.; Schütze, K.; Moriwaki, Y.; Heo, L.; Ovchinnikov, S.; Steinegger, M. ColabFold: making protein folding accessible to all. Nature methods 2022, 19, 679–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, C.; Abbeel, P.; Levine, S. Model-agnostic meta-learning for fast adaptation of deep networks. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2017; pp. 1126–1135. [Google Scholar]

- Snell, J.; Swersky, K.; Zemel, R. Prototypical networks for few-shot learning. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Notin, P.; Kollasch, A.; Ritter, D.; Van Niekerk, L.; Paul, S.; Spinner, H.; Rollins, N.; Shaw, A.; Orenbuch, R.; Weitzman, R.; et al. Proteingym: Large-scale benchmarks for protein fitness prediction and design. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2023, 36, 64331–64379. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, J.; Rao, R.; Verkuil, R.; Liu, J.; Sercu, T.; Rives, A. Language models enable zero-shot prediction of the effects of mutations on protein function. Advances in neural information processing systems 2021, 34, 29287–29303. [Google Scholar]

- Su, J.; Han, C.; Zhou, Y.; Shan, J.; Zhou, X.; Yuan, F. Saprot: Protein language modeling with structure-aware vocabulary. BioRxiv 2023, 2023–10. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.; Verkuil, R.; Liu, J.; Lin, Z.; Hie, B.; Sercu, T.; Lerer, A.; Rives, A. Learning inverse folding from millions of predicted structures. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2022; pp. 8946–8970. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Child, R.; Luan, D.; Amodei, D.; Sutskever, I.; et al. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAI blog 2019, 1, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Hestness, J.; Narang, S.; Ardalani, N.; Diamos, G.; Jun, H.; Kianinejad, H.; Patwary, M.M.A.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, Y. Deep learning scaling is predictable, empirically. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1712.00409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelofs, R.; Shankar, V.; Recht, B.; Fridovich-Keil, S.; Hardt, M.; Miller, J.; Schmidt, L. A meta-analysis of overfitting in machine learning. Advances in neural information processing systems 2019, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Nayfach, S.; Roux, S.; Seshadri, R.; Udwary, D.; Varghese, N.; Schulz, F.; Wu, D.; Paez-Espino, D.; Chen, I.M.; Huntemann, M.; et al. A genomic catalog of Earth’s microbiomes. Nature biotechnology 2021, 39, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalchbrenner, N.; Espeholt, L.; Simonyan, K.; Oord, A.; Graves, A.; Kavukcuoglu, K. Neural machine translation in linear time. arXiv arXiv:1610.10099. [CrossRef]

- Gehring, J.; Auli, M.; Grangier, D.; Yarats, D.; Dauphin, Y.N. Convolutional sequence to sequence learning. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2017; pp. 1243–1252. [Google Scholar]

- Tay, Y.; Dehghani, M.; Bahri, D.; Metzler, D. Efficient Transformers: A Survey. arXiv 2022, arXiv:cs. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantar, E.; Ashkboos, S.; Hoefler, T.; Alistarh, D. Gptq: Accurate post-training quantization for generative pre-trained transformers. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.17323. [Google Scholar]

- Frankle, J.; Carbin, M. The lottery ticket hypothesis: Finding sparse, trainable neural networks. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.03635. [Google Scholar]

- Hopf, T.A.; Ingraham, J.B.; Poelwijk, F.J.; Schärfe, C.P.; Springer, M.; Sander, C.; Marks, D.S. Mutation effects predicted from sequence co-variation. Nature biotechnology 2017, 35, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courbariaux, M.; Hubara, I.; Soudry, D.; El-Yaniv, R.; Bengio, Y. Binarized neural networks: Training deep neural networks with weights and activations constrained to+ 1 or-1. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1602.02830. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S.; Wang, H.; Ma, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, W.; Huang, S.; Dong, L.; Wang, R.; Xue, J.; Wei, F. The era of 1-bit llms: All large language models are in 1.58 bits. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.177641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Liu, B.; Wang, X.; Zhang, B.; Yan, J. Ternary weight networks. arXiv arXiv:1605.04711.

- Zhu, C.; Han, S.; Mao, H.; Dally, W.J. Trained ternary quantization. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1612.01064. [Google Scholar]

- Banner, R.; Nahshan, Y.; Soudry, D. Post training 4-bit quantization of convolutional networks for rapid-deployment. Advances in neural information processing systems 2019, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Notin, P.; Dias, M.; Frazer, J.; Marchena-Hurtado, J.; Gomez, A.N.; Marks, D.; Gal, Y. Tranception: protein fitness prediction with autoregressive transformers and inference-time retrieval. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2022; pp. 16990–17017. [Google Scholar]

- Alley, E.C.; Khimulya, G.; Biswas, S.; AlQuraishi, M.; Church, G.M. Unified rational protein engineering with sequence-based deep representation learning. Nature methods 2019, 16, 1315–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frey, N.C.; Joren, T.; Ismail, A.A.; Goodman, A.; Bonneau, R.; Cho, K.; Gligorijević, V. Cramming protein language model training in 24 gpu hours. bioRxiv 2024, 2024–05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, A.; Yang, K.; Deng, J. Stacked hourglass networks for human pose estimation. In Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision, 2016; Springer; pp. 483–499. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Welling, M. Auto-encoding variational bayes. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1312.6114. [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch, W. A solution for the best rotation to relate two sets of vectors. Foundations of Crystallography 1976, 32, 922–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba, J.L.; Kiros, J.R.; Hinton, G.E. Layer normalization. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1607.06450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioffe, S.; Szegedy, C. Batch normalization: Accelerating deep network training by reducing internal covariate shift. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. pmlr, 2015; pp. 448–456. [Google Scholar]

- Mentzer, F.; Minnen, D.; Agustsson, E.; Tschannen, M. Finite scalar quantization: Vq-vae made simple. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.15505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gerven, M.; Bohte, S. Artificial neural networks as models of neural information processing. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Oord, A.; Vinyals, O.; et al. Neural discrete representation learning. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of molecular biology 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remmert, M.; Biegert, A.; Hauser, A.; Söding, J. HHblits: lightning-fast iterative protein sequence searching by HMM-HMM alignment. Nature methods 2012, 9, 173–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, R.M.; Liu, J.; Verkuil, R.; Meier, J.; Canny, J.; Abbeel, P.; Sercu, T.; Rives, A. MSA transformer. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2021; pp. 8844–8856. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, J.; Johnson, D.D.; Ho, J.; Tarlow, D.; Van Den Berg, R. Structured denoising diffusion models in discrete state-spaces. Advances in neural information processing systems 2021, 34, 17981–17993. [Google Scholar]

- Hoogeboom, E.; Nielsen, D.; Jaini, P.; Forré, P.; Welling, M. Argmax flows and multinomial diffusion: Learning categorical distributions. Advances in neural information processing systems 2021, 34, 12454–12465. [Google Scholar]

- Steinegger, M.; Söding, J. MMseqs2 enables sensitive protein sequence searching for the analysis of massive data sets. Nature biotechnology 2017, 35, 1026–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vig, J.; Belinkov, Y. Analyzing the structure of attention in a transformer language model. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.04284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needleman, S.B.; Wunsch, C.D. A general method applicable to the search for similarities in the amino acid sequence of two proteins. Journal of molecular biology 1970, 48, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauparas, J.; Anishchenko, I.; Bennett, N.; Bai, H.; Ragotte, R.J.; Milles, L.F.; Wicky, B.I.; Courbet, A.; de Haas, R.J.; Bethel, N.; et al. Robust deep learning–based protein sequence design using ProteinMPNN. Science 2022, 378, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Gable, A.L.; Nastou, K.C.; Lyon, D.; Kirsch, R.; Pyysalo, S.; Doncheva, N.T.; Legeay, M.; Fang, T.; Bork, P.; et al. The STRING database in 2021: customizable protein–protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic acids research 2021, 49, D605–D612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Koltun, V. Multi-scale context aggregation by dilated convolutions. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1511.07122. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.C.; Papandreou, G.; Kokkinos, I.; Murphy, K.; Yuille, A.L. Deeplab: Semantic image segmentation with deep convolutional nets, atrous convolution, and fully connected crfs. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2017, 40, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poli, M.; Massaroli, S.; Nguyen, E.; Fu, D.Y.; Dao, T.; Baccus, S.; Bengio, Y.; Ermon, S.; Ré, C. Hyena hierarchy: Towards larger convolutional language models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2023; pp. 28043–28078. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, A.; Goel, K.; Ré, C. Efficiently modeling long sequences with structured state spaces. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.00396. [Google Scholar]

- Dauphin, Y.N.; Fan, A.; Auli, M.; Grangier, D. Language modeling with gated convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2017; pp. 933–941. [Google Scholar]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural computation 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandes, N.; Ofer, D.; Peleg, Y.; Rappoport, N.; Linial, M. ProteinBERT: a universal deep-learning model of protein sequence and function. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 2102–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, L.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; Almeida, D.; Wainwright, C.; Mishkin, P.; Zhang, C.; Agarwal, S.; Slama, K.; Ray, A.; et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. Advances in neural information processing systems 2022, 35, 27730–27744. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Z.; Wang, P.; Zhu, Q.; Xu, R.; Song, J.; Bi, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, M.; Li, Y.; Wu, Y.; et al. Deepseekmath: Pushing the limits of mathematical reasoning in open language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.03300. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, J.; Ruder, S. Universal language model fine-tuning for text classification. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1801.06146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, J.; Yu, B.; Maybank, S.J.; Tao, D. Knowledge distillation: A survey. International journal of computer vision 2021, 129, 1789–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanh, V.; Debut, L.; Chaumond, J.; Wolf, T. DistilBERT, a distilled version of BERT: smaller, faster, cheaper and lighter. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1910.01108. [Google Scholar]

- Min, S.; Lee, B.; Yoon, S. Deep learning in bioinformatics. Briefings in bioinformatics 2017, 18, 851–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gligorijević, V.; Renfrew, P.D.; Kosciolek, T.; Leman, J.K.; Berenberg, D.; Vatanen, T.; Chandler, C.; Taylor, B.C.; Fisk, I.M.; Vlamakis, H.; et al. Structure-based protein function prediction using graph convolutional networks. Nature communications 2021, 12, 3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Yu, H.; Song, X.; Liu, R.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, D. Mobilebert: a compact task-agnostic bert for resource-limited devices. arXiv arXiv:2004.02984.

- Srivastava, N.; Hinton, G.; Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Salakhutdinov, R. Dropout: a simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. The journal of machine learning research 2014, 15, 1929–1958. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, N.; Qin, Y.; Yang, G.; Wei, F.; Yang, Z.; Su, Y.; Hu, S.; Chen, Y.; Chan, C.M.; Chen, W.; et al. Delta tuning: A comprehensive study of parameter efficient methods for pre-trained language models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.06904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houlsby, N.; Giurgiu, A.; Jastrzebski, S.; Morrone, B.; De Laroussilhe, Q.; Gesmundo, A.; Attariyan, M.; Gelly, S. Parameter-efficient transfer learning for NLP. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2019; pp. 2790–2799. [Google Scholar]

- Lester, B.; Al-Rfou, R.; Constant, N. The power of scale for parameter-efficient prompt tuning. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.08691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.L.; Liang, P. Prefix-tuning: Optimizing continuous prompts for generation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2101.00190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzadeh, S.I.; Farajtabar, M.; Li, A.; Levine, N.; Matsukawa, A.; Ghasemzadeh, H. Improved knowledge distillation via teacher assistant. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence 2020, Vol. 34, 5191–5198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, D.; Brown, T.; Conerly, T.; DasSarma, N.; Drain, D.; El-Showk, S.; Elhage, N.; Hatfield-Dodds, Z.; Henighan, T.; Hume, T.; et al. Scaling laws and interpretability of learning from repeated data. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.10487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, B.; Eismann, S.; Suriana, P.; Townshend, R.J.; Dror, R. Learning from protein structure with geometric vector perceptrons. arXiv arXiv:2009.01411. [CrossRef]

- Varadi, M.; Bertoni, D.; Magana, P.; Paramval, U.; Pidruchna, I.; Radhakrishnan, M.; Tsenkov, M.; Nair, S.; Mirdita, M.; Yeo, J.; et al. AlphaFold Protein Structure Database in 2024: providing structure coverage for over 214 million protein sequences. Nucleic acids research 2024, 52, D368–D375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kempen, M.; Kim, S.S.; Tumescheit, C.; Mirdita, M.; Lee, J.; Gilchrist, C.L.; Söding, J.; Steinegger, M. Fast and accurate protein structure search with Foldseek. Nature biotechnology 2024, 42, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rost, B. Twilight zone of protein sequence alignments. Protein engineering 1999, 12, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillitoe, I.; Bordin, N.; Dawson, N.; Waman, V.P.; Ashford, P.; Scholes, H.M.; Pang, C.S.; Woodridge, L.; Rauer, C.; Sen, N.; et al. CATH: increased structural coverage of functional space. Nucleic acids research 2021, 49, D266–D273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. Decoupled weight decay regularization. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.05101. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, P.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; Noordhuis, P.; Wesolowski, L.; Kyrola, A.; Tulloch, A.; Jia, Y.; He, K. Accurate, large minibatch sgd: Training imagenet in 1 hour. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.02677. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Liu, X.; Gao, J.; Chen, W.; Han, J. Understanding the difficulty of training transformers. arXiv arXiv:2004.08249. [CrossRef]

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. Sgdr: Stochastic gradient descent with warm restarts. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1608.03983. [Google Scholar]

- Bergstra, J.; Bengio, Y. Random search for hyper-parameter optimization. The journal of machine learning research 2012, 13, 281–305. [Google Scholar]

- Snoek, J.; Larochelle, H.; Adams, R.P. Practical bayesian optimization of machine learning algorithms. Advances in neural information processing systems 2012, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, W.; et al. Lora: Low-rank adaptation of large language models. ICLR 2022, 1, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.Y.; Wang, C.Y.; Yin, H.; Molchanov, P.; Wang, Y.C.F.; Cheng, K.T.; Chen, M.H. Dora: Weight-decomposed low-rank adaptation. In Proceedings of the Forty-first International Conference on Machine Learning, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Tam, D.; Muqeeth, M.; Mohta, J.; Huang, T.; Bansal, M.; Raffel, C.A. Few-shot parameter-efficient fine-tuning is better and cheaper than in-context learning. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 1950–1965. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.L.; Liang, P. Prefix-tuning: Optimizing continuous prompts for generation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2101.00190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettmers, T.; Pagnoni, A.; Holtzman, A.; Zettlemoyer, L. Qlora: Efficient finetuning of quantized llms. Advances in neural information processing systems 2023, 36, 10088–10115. [Google Scholar]

- Team, E. “ESM Cambrian: Revealing the mysteries of proteins with unsupervised learning”. 2024. Available online: https://www.evolutionaryscale.ai/blog/esm-cambrian.

- Elnaggar, A.; Essam, H.; Salah-Eldin, W.; Moustafa, W.; Elkerdawy, M.; Rochereau, C.; Rost, B. Ankh: Optimized protein language model unlocks general-purpose modelling. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.06568. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkisyan, K.S.; Bolotin, D.A.; Meer, M.V.; Usmanova, D.R.; Mishin, A.S.; Sharonov, G.V.; Ivankov, D.N.; Bozhanova, N.G.; Baranov, M.S.; Soylemez, O.; et al. Local fitness landscape of the green fluorescent protein. Nature 2016, 533, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocklin, G.J.; Chidyausiku, T.M.; Goreshnik, I.; Ford, A.; Houliston, S.; Lemak, A.; Carter, L.; Ravichandran, R.; Mulligan, V.K.; Chevalier, A.; et al. Global analysis of protein folding using massively parallel design, synthesis, and testing. Science 2017, 357, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, H.M.; Westbrook, J.; Feng, Z.; Gilliland, G.; Bhat, T.N.; Weissig, H.; Shindyalov, I.N.; Bourne, P.E. The protein data bank. Nucleic acids research 2000, 28, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klausen, M.S.; Jespersen, M.C.; Nielsen, H.; Jensen, K.K.; Jurtz, V.I.; Soenderby, C.K.; Sommer, M.O.A.; Winther, O.; Nielsen, M.; Petersen, B.; et al. NetSurfP-2.0: Improved prediction of protein structural features by integrated deep learning. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics 2019, 87, 520–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, F.; Liu, T.Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, W.; Li, H. Listwise approach to learning to rank: theory and algorithm. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 25th international conference on Machine learning, 2008; pp. 1192–1199. [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch, W.; Sander, C. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers: Original Research on Biomolecules 1983, 22, 2577–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagoruyko, S.; Komodakis, N. Paying more attention to attention: Improving the performance of convolutional neural networks via attention transfer. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1612.03928. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, T. A survey of model compression and acceleration for deep neural networks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1710.09282. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.; Mao, H.; Dally, W.J. Deep compression: Compressing deep neural networks with pruning, trained quantization and huffman coding. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1510.00149. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Yoon, K.J. Knowledge distillation and student-teacher learning for visual intelligence: A review and new outlooks. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2021, 44, 3048–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geffen, Y.; Ofran, Y.; Unger, R. DistilProtBert: a distilled protein language model used to distinguish between real proteins and their randomly shuffled counterparts. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, ii95–ii98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.L.; Juergens, D.; Bennett, N.R.; Trippe, B.L.; Yim, J.; Eisenach, H.E.; Ahern, W.; Borst, A.J.; Ragotte, R.J.; Milles, L.F.; et al. De novo design of protein structure and function with RFdiffusion. Nature 2023, 620, 1089–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.; O’Neill, M.; Pritzel, A.; Antropova, N.; Senior, A.; Green, T.; Žídek, A.; Bates, R.; Blackwell, S.; Yim, J.; et al. Protein complex prediction with AlphaFold-Multimer. biorxiv 2021, 2021–10. [Google Scholar]

- Židek, A. AlphaFold v.2.3.0 Technical Note. 2022. Available online: https://github.com/google-deepmind/alphafold/blob/main/docs/technical_note_v2.3.0.md.

- Lee, D.H.; et al. Pseudo-label: The simple and efficient semi-supervised learning method for deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the Workshop on challenges in representation learning, ICML. Atlanta, 2013; Vol. 3, p. 896. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Q.; Luong, M.T.; Hovy, E.; Le, Q.V. Self-training with noisy student improves imagenet classification. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020; pp. 10687–10698. [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner, M.; Ball, C.A.; Blake, J.A.; Botstein, D.; Butler, H.; Cherry, J.M.; Davis, A.P.; Dolinski, K.; Dwight, S.S.; Eppig, J.T.; et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nature genetics 2000, 25, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksander, S.A.; Balhoff, J.; Carbon, S.; Cherry, J.M.; Drabkin, H.J.; Ebert, D.; Feuermann, M.; Gaudet, P.; Harris, N.L.; et al. The gene ontology knowledgebase in 2023. Genetics 2023, 224, iyad031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kullback, S.; Leibler, R.A. On information and sufficiency. The annals of mathematical statistics 1951, 22, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bairoch, A. The ENZYME database in 2000. Nucleic acids research 2000, 28, 304–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Shou, L.; Pei, J.; Lin, W.; Gong, M.; Fu, Y.; Jiang, D. Reinforced multi-teacher selection for knowledge distillation. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence 2021, Vol. 35, 14284–14291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, B.; Kligys, S.; Chen, B.; Zhu, M.; Tang, M.; Howard, A.; Adam, H.; Kalenichenko, D. Quantization and training of neural networks for efficient integer-arithmetic-only inference. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018; pp. 2704–2713. [Google Scholar]

- Nagel, M.; Fournarakis, M.; Amjad, R.A.; Bondarenko, Y.; Van Baalen, M.; Blankevoort, T. A white paper on neural network quantization. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.08295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondarenko, Y.; Nagel, M.; Blankevoort, T. Understanding and overcoming the challenges of efficient transformer quantization. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.12948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, P.; Perez, E.; Piktus, A.; Petroni, F.; Karpukhin, V.; Goyal, N.; Küttler, H.; Lewis, M.; Yih, W.t.; Rocktäschel, T.; et al. Retrieval-augmented generation for knowledge-intensive nlp tasks. Advances in neural information processing systems 2020, 33, 9459–9474. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Skolnick, J. Scoring function for automated assessment of protein structure template quality. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics 2004, 57, 702–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, J.; Barbato, A.; Behringer, D.; Studer, G.; Roth, S.; Bertoni, M.; Mostaguir, K.; Gumienny, R.; Schwede, T. Continuous Automated Model EvaluatiOn (CAMEO) complementing the critical assessment of structure prediction in CASP12. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics 2018, 86, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mistry, J.; Chuguransky, S.; Williams, L.; Qureshi, M.; Salazar, G.A.; Sonnhammer, E.L.; Tosatto, S.C.; Paladin, L.; Raj, S.; Richardson, L.J.; et al. Pfam: The protein families database in 2021. Nucleic acids research 2021, 49, D412–D419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Skolnick, J. TM-align: a protein structure alignment algorithm based on the TM-score. Nucleic acids research 2005, 33, 2302–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, J.; Douze, M.; Jégou, H. Billion-scale similarity search with GPUs. IEEE Transactions on Big Data 2019, 7, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkov, Y.A.; Yashunin, D.A. Efficient and robust approximate nearest neighbor search using hierarchical navigable small world graphs. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2018, 42, 824–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, S.R. Accelerated profile HMM searches. PLoS computational biology 2011, 7, e1002195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morcos, F.; Pagnani, A.; Lunt, B.; Bertolino, A.; Marks, D.S.; Sander, C.; Zecchina, R.; Onuchic, J.N.; Hwa, T.; Weigt, M. Direct-coupling analysis of residue coevolution captures native contacts across many protein families. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2011, 108, E1293–E1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinegger, M.; Söding, J. Clustering huge protein sequence sets in linear time. Nature communications 2018, 9, 2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, A.; Barkoutsos, P.K.; Woerner, S.; Tavernelli, I. Resource-efficient quantum algorithm for protein folding. npj Quantum Information 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandarana, P.; Hegade, N.N.; Montalban, I.; Solano, E.; Chen, X. Digitized Counterdiabatic Quantum Algorithm for Protein Folding. Physical Review Applied 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doga, H.; Raubenolt, B.; Cumbo, F.; Joshi, J.; DiFilippo, F.P.; Qin, J.; Blankenberg, D.; Shehab, O. A Perspective on Protein Structure Prediction Using Quantum Computers. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 2024, 20, 3359–3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.H.; Doga, H.; Raubenolt, B.; Mostame, S.; DiSanto, N.; Cumbo, F.; Joshi, J.; Linn, H.; Gaffney, M.; Holden, A.; et al. Quantum Algorithm for Protein Structure Prediction Using the Face-Centered Cubic Lattice. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.08955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, R.; Chang, W.L. Quantum speedup for protein structure prediction. IEEE Transactions on NanoBioscience 2021, 20, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babej, T.; Ing, C.; Fingerhuth, M. Coarse-grained lattice protein folding on a quantum annealer. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1811.00713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fingerhuth, M.; Babej, T.; Ing, C. A quantum alternating operator ansatz with hard and soft constraints for lattice protein folding. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.13411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdomo, A.; Truncik, C.; Tubert-Brohman, I.; Rose, G.; Áspuru-Guzik, A. Construction of model hamiltonians for adiabatic quantum computation and its application to finding low-energy conformations of lattice protein models. Physical Review A 2008, 78, 012320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdomo-Ortiz, A.; Dickson, N.; Drew-Brook, M.; Rose, G.; Áspuru-Guzik, A. Finding low-energy conformations of lattice protein models by quantum annealing. Scientific Reports 2012, 2, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babbush, R.; Perdomo-Ortiz, A.; O’Gorman, B.; Macready, W.; Áspuru-Guzik, A. Construction of energy functions for lattice heteropolymer models: Efficient encodings for constraint satisfaction programming and quantum annealing. In Advances in Chemical Physics; John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2014; Vol. 155, pp. 201–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godzik, A.; Kolinski, A.; Skolnick, J. Lattice representations of globular proteins: How good are they? Journal of Computational Chemistry 1993, 14, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaldone, A.M.; Shee, Y.; Kyro, G.W.; Farag, M.H.; Chandani, Z.; Kyoseva, E.; Batista, V.S. A Hybrid Transformer Architecture with a Quantized Self-Attention Mechanism Applied to Molecular Generation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:quant. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NVIDIA Corporation. CUDA-Q: A Platform for Hybrid Quantum–Classical Computing Version 0.12.0. 2025. Available online: https://github.com/NVIDIA/cuda-quantum.

- NVIDIA Corporation. CUDA-Q Documentation (latest). 2025. Available online: https://nvidia.github.io/cuda-quantum/latest/.

| Category | Method | Brief Description |

|---|---|---|

| Transformer-based | 2Bits of Protein [24] | Training with ternary weights for memory and compute efficiency. |

| RAG-ESM [25] | Lightweight retrieval-augmented model with parameter-sharing. | |

| CHEAP [26] | Compressing high-dimensional embeddings while preserving structure. | |

| Cramming Challenge [23] | Train a performant pLM in 24 hours on a single GPU. | |

| CNN-based | CARP [27] | Using dilated-convolutions (ByteNet-style) to replace attention layers. |

| Hyena operator [28] | Implicit long convolutions for subquadratic scaling on long sequences. |

| Category | Method | Brief Description |

|---|---|---|

| Inference | PLMSearch [37] | Efficient remote homology search using learned embeddings. |

| PTQ4Protein [38] | PTQ for reducing inference memory and compute. | |

| DHR [20] | Transforms protein homology detection from pairwise alignment into vector retrieval. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).