1. Introduction

TIR imaging technology breaks through the dependence of traditional optical imaging on illumination conditions and exhibits excellent performance in surveillance and tracking under nighttime and low-light environments. Thus, it is widely applied in fields such as military security, smart cities and forest fire prevention[

1]. However, current TIR imaging equipment still has significant shortcomings in spatial resolution. Due to the limited number of photosensitive units that can be integrated per unit area of TIR sensors, HR TIR cameras are usually accompanied by problems such as high manufacturing costs, large power consumption and high heat dissipation requirements. Their size and weight are also difficult to meet the lightweight and low energy consumption requirements of UAV platforms[

2]. Therefore, improving the resolution of TIR images at the hardware level is not only technically complex and costly, but also has low engineering feasibility in mobile platforms such as UAVs and large-scale application scenarios. To overcome the limitations of hardware conditions, researchers have shifted their focus to improving the resolution of TIR images through software technologies.

However, existing image SR technologies are quite sensitive to noise and temperature fluctuations in TIR imaging. They have weak capabilities in reconstructing detailed information and complex textures, and lack the supplementation of contextual information, resulting in poor consistency between reconstructed structures and semantics. For example, problems such as edge blurring and geometric distortion may occur[

3].

At present, TIR cameras mounted on micro and small UAV platforms are generally integrated with dual-mode imaging systems (TIR and VIS), which can realize the synchronous acquisition of VIS images and TIR images. HR VIS images contain richer texture information. If they can be used in the SR process of TIR images, they can well compensate for the lack of detailed features in TIR images.

Given the poor performance of SR relying solely on TIR images, some research works have attempted to introduce VIS images to assist in the SR reconstruction of TIR images. For example, Almasri et al.[

4] proposed a multimodal VIS-TIR fusion model, which fuses detailed information from VIS images into TIR images based on the FSRCNN model to enhance the textures of TIR images. Gupta et al.[

5] proposed the UGSR model, which uses dense blocks to alleviate the gradient vanishing problem in deep neural networks and focuses on regions where VIS and TIR features are highly correlated through a spatial attention module, thereby realizing VIS-guided SR reconstruction of TIR images. However, in general, the SR reconstruction of UAV TIR images currently has the following four main problems:

Existing methods fail to consider the temperature characteristics of TIR images: There are many methods that use VIS images to assist in the SR reconstruction of TIR images, but most focus on the fusion of textures or image features without considering the temperature information of TIR images. As a result, although the reconstruction results are visually improved, the consistency of temperature information before and after reconstruction cannot be guaranteed, thereby weakening the practical value of TIR images in heat-sensitive fields.

Model training is highly dependent on ground truth images, with limited generalization ability: Most existing SR methods use HR ground truth images and downsampled LR images for training and validation. The models are highly dependent on data, and for complex and variable application scenarios, their transfer and generalization abilities are poor, which limits the promotion of the models in practical applications.

Existing SR models have insufficient anti-noise interference ability in texture feature reconstruction: Existing SR models mainly extract features through the sliding convolution of convolution kernels on images. For TIR imaging disturbed by factors such as noise, this method lacks effective anti-interference and feature enhancement mechanisms, making it impossible to suppress noise while retaining real texture features.

The sufficient transfer of textures from VIS images is ignored: In the process of using VIS images to enhance TIR images, existing methods often focus on the transfer of edge information and neglect the sufficient extraction of textures[

6] , leading to the problem of blurred textures in the reconstructed TIR images.

To address the aforementioned issues, this paper proposes a TIR image SR method based on diffusion models and cross-modal transfer. Firstly, considering the thermal radiation characteristics of different ground objects, the method assigns different conversion coefficients to the detailed textures corresponding to different ground objects in HR VIS images during the inference process of the diffusion model. This converts the brightness information of VIS images into temperature information in TIR images, thereby maintaining temperature consistency as much as possible while transferring textures.

Secondly, diffusion models are adopted as the foundation of the proposed method. They possess strong generative capabilities and robustness to complex data distributions. Additionally, diffusion models can take LR images as conditions and iteratively estimate noise-free HR images through conditional denoising, which can solve the problem of noise interference during SR reconstruction.

Thirdly, by gradually transferring multi-scale VIS textures during the inference process of the diffusion model, the method guides the SR reconstruction of TIR images without relying on HR ground truth images. This avoids the dependence of existing models on HR ground truth images during training and improves the generalization ability of the model.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews related research;

Section 3 describes the research method;

Section 4 introduces the dataset, experimental methods, and evaluation metrics;

Section 5 presents the results;

Section 6 provides a discussion;

Section 7 summarizes the paper.

2. Related Work

The purpose of image SR is to improve the resolution and quality of LR images. Relevant research works can be roughly divided into three categories: Single Image Super-Resolution (SISR) methods, Reference-Based Super-Resolution (Ref-SR) methods, and image fusion methods, which are briefly described as follows.

2.1. Single Image Super-Resolution

The main problem of SISR methods is that their processing process is an ill-posed problem with no unique solution. Therefore, various prior knowledge or assumptions need to be used to constrain the solution process to obtain relatively reasonable SR reconstruction results. SISR methods can be divided into traditional SR methods and deep learning-based SR methods.

2.1.1. Traditional SR Methods

Traditional SR methods mainly establish the mapping relationship between LR images and HR images based on interpolation or modeling. They achieve a certain improvement in image resolution but have significant limitations.

Interpolation-based methods estimate missing pixel values using adjacent pixel values in LR images to generate higher-resolution images. Examples include bicubic interpolation[

7], edge-directed interpolation[

8], and wavelet transform interpolation[

9]. These methods are simple in computation and fast in speed, but they do not consider the semantic structure, texture features, or statistical priors of images. They are prone to aliasing and have limited ability to recover image details.

Reconstruction model-based methods construct corresponding image reconstruction models according to the principle of image degradation. They use statistical characteristics such as local self-similarity and gradient distribution of images as prior knowledge to reconstruct HR images from LR images. Such methods include Iterative Back Projection[

10], Projection onto Convex Sets[

11], and Maximum A Posteriori[

12]. These methods have a certain degree of interpretability but are built on ideal image degradation models. Additionally, the time cost of multiple iterative solutions is high, making it difficult to cope with complex image degradation in real scenarios and limiting their practicality.

2.1.2. Deep Learning-Based SR Methods

These methods are mainly used to address the SR problem of VIS images. For the sake of comparison, we first elaborate on the SR methods for VIS images, and then those for TIR images.

In recent years, researchers have conducted in-depth studies on the SR of VIS images by virtue of deep learning techniques and achieved abundant results. In terms of specific methods, they can be roughly categorized into four types: Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR)-oriented methods, Generative Adversarial Network (GAN)-based methods, Flow-based methods, and Diffusion Model-based methods.

PSNR-oriented methods aim to minimize the L1 or L2 loss function between the original and super-resolved images. SRCNN proposed by Dong et al.[

13] is the first image SR model based on Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). Composed of three convolutional layers, it directly learns the end-to-end mapping relationship between LR images and HR images. To solve the problem of complex upsampling computation in SRCNN, Shi et al.[

14] put forward the ESPCN method. It pioneered the use of Sub-pixel Convolutional Layers to rearrange LR feature maps into HR images, realizing more efficient upsampling.

PSNR-oriented methods are quite intuitive and have simple network structures. They can achieve high scores in quantitative evaluation metrics such as PSNR and Structural Similarity (SSIM). However, due to their excessive focus on pixel differences, they tend to perform smoothing during feature learning. This makes it difficult to effectively reconstruct detailed information and complex textures, resulting in insufficient improvement in the visual effect of the generated images, which often lack natural texture features and realism.

GAN-based methods utilize a discriminator to evaluate the generated images, guiding the generator to continuously optimize the generation results so as to enhance image quality. Ledig et al.[

15] took the lead in proposing the SRGAN model for SR image enhancement based on GAN. By integrating the Super-Resolution Residual Network (SRResNet), adversarial loss, and perceptual loss, this model improved both the quality and texture details of super-resolved images. Building on SRGAN, Wang et al.[

16] proposed ESRGAN (Enhanced SRGAN) by optimizing the designs of the generator, discriminator, and loss function, which alleviated the artifact problem existing in images generated by SRGAN.

In addition to optimizing PSNR, GAN-based methods can generate high-quality images with richer detailed features and improve the visual effect of images. Nevertheless, their training process is unstable and consumes substantial computing resources. Moreover, adversarial training may lead to the emergence of erroneous texture features in the super-resolved images.

Flow-based methods adopt invertible flow models to map LR images to the latent space, and then generate super-resolved images through inverse transformation. SRFlow, proposed by Lugmayr et al[

17], is the first flow-based model for SR image generation. This model regards the SR task as a problem of learning the conditional probability distribution of HR images. By designing a conditional normalizing flow architecture and training with negative log-likelihood as the loss function, it achieved better results than GAN-based models. However, it requires a long training time and yields lower scores in evaluation metrics like PSNR and SSIM when compared with models trained solely using reconstruction loss functions. Jo et al.[

18] improved SRFlow and proposed SRFlow-DA. They expanded the receptive field by stacking more convolutional layers and adjusted the network structure to reduce the number of parameters and training time, while also achieving higher scores in evaluation metrics.

Flow-based methods solve the problem of unstable adversarial training in GAN-based methods through a training strategy that maximizes log-likelihood. The flow models they employ provide a clear probability distribution for the generated images and enhance the interpretability of the generation process. Nevertheless, these methods suffer from high model complexity, requiring substantial computing resources and training time. Furthermore, they have high requirements for the resolution of the input images to be super-resolved. When dealing with images of excessively low quality, their SR results are less effective than those of other methods such as GAN-based methods.

Diffusion-based methods operate via a two-stage probabilistic process: a forward diffusion process that gradually adds Gaussian noise to the data, and a reverse denoising process that iteratively reconstructs the signal. SR3 proposed by Saharia et al.[

19] is the first method that applies diffusion models to image SR. The images generated by SR3 have clear textures, and the model possesses strong versatility. However, it has the problems of detail loss and semantic distortion. The SRDiff method proposed by Li et al.[

20] introduces residual prediction, taking the difference between HR images and upsampled LR images as input. This enables the model to focus on detail restoration, accelerating model convergence while achieving better results, yet it also faces the issue of semantic distortion.

Diffusion Model-based image SR methods can generate high-quality images. They feature stable training processes and strong versatility, making them quite ideal image SR methods at present. Nevertheless, they also have drawbacks such as high computational costs, proneness to color deviation, and the lack of a unified comparison benchmark[

21].

- 2.

SR Methods for TIR Images

In recent years, due to the remarkable achievements in the SR reconstruction of VIS images, an increasing number of scholars have attempted to apply VIS image SR methods to the SR reconstruction of TIR images.

Representative works include the following: Inspired by SRCNN[

13], Choi et al.[

22] proposed the TEN method, which uses a shallow convolutional neural network for the SR reconstruction of TIR images. However, limited by the scarcity of HR TIR datasets, this study trained the model using VIS image data. Essentially, this work applies a model trained on VIS data to the SR of TIR images, resulting in certain semantic deviations in the super-resolved TIR images. By comparing different training domains such as the grayscale domain and the brightness domain, Lee et al.[

23] determined that the brightness domain is the optimal training domain and proposed the TIECNN model based on the brightness domain and residual learning. This model converges quickly and improves the overall quality of super-resolved TIR images, but it is insufficient in enhancing image details, leading to obviously blurred textures. Chen et al.[

24] proposed the IERN model, which is trained on the DIV2K dataset[

25]. It adopts a lightweight iterative reconstruction mechanism based on linear compressed skip connections to gradually restore image texture information. The model is efficient and lightweight, but it relies on HR TIR images for training, resulting in limited transferability and generalization ability.

In general, the SISR methods for TIR images currently face the following main challenges:

Due to the lack of HR TIR datasets[

26], some SR methods use VIS image data for training. However, the differences in features between VIS and TIR images lead to semantic deviations in the SR reconstruction results, which fail to accurately reflect the true information of TIR images.

Although some SR methods can accelerate model convergence and improve the overall image quality, they are ineffective in enhancing the details of TIR images. The image textures remain relatively blurred, making it difficult to meet the requirements of high-precision applications.

Some SR methods are trained using HR TIR images and their corresponding LR images obtained via bicubic downsampling. Since model training relies on specific HR TIR images and degradation methods, the generalization ability of the model is limited, and it is difficult to maintain stable SR performance under different scenarios or data conditions.

2.2. Reference-Based Super-Resolution Methods

To address the issues that SISR methods require large-scale HR image datasets and that a single LR image itself contains limited information[

27], some researchers have proposed using similar HR reference images as prior knowledge to assist in SR reconstruction. However, there are often significant differences between reference images and LR images in key dimensions such as content composition and shooting perspective. How to accurately extract and transfer effective texture information from reference images to achieve high-quality compensation of LR image details has become a key bottleneck restricting the development of this technology[

28].

2.2.1. Methods for VIS Images

Representative research works include the following: Zhang et al.[

29] proposed the SRNTT model, which uses a pre-trained VGG network to extract features of LR images and reference images respectively. It searches for locally similar textures in the feature space to construct exchange feature maps, and then integrates them into the SR reconstruction network through a texture transfer model. Although this method improves the accuracy of detail reconstruction by utilizing similar content from reference images, it requires texture transmission and matching across multiple feature layers, and demands a high degree of content similarity between reference images and the target LR image. Building on this, Yang et al.[

30] introduced the Transformer architecture and proposed the TTSR model. It uses an attention mechanism to search for corresponding relationships of deep features between LR images and reference images, and simultaneously incorporates a transfer-aware loss to constrain the similarity of texture features from reference images, thereby achieving better texture transfer effects. However, it requires a large number of patch match computations. To address this issue, Lu et al.[

31] proposed the MASA model, which adopts a coarse-to-fine accelerated matching strategy and a spatially adaptive feature distribution mapping strategy to narrow the search space, thereby reducing the complexity of matching computations. In addition, Cao et al.[

28] proposed the DATSR model using deformable convolution. It determines relevant positions by calculating feature similarity, and then adaptively transfers textures around these relevant positions using improved deformable convolution. This model can judge whether to transfer information from reference images when the reference images lack relevant texture information, thus enhancing the model's robustness. Nevertheless, when the LR image itself is deficient in texture information, it is difficult to supplement sufficient detail information, making it impossible to achieve ideal reconstruction results.

In general, Ref-SR methods alleviate the ill-posed problem of SISR methods to a certain extent by introducing texture information from reference images. However, they have high requirements for the richness and clarity of image features used for computation. When the LR image has blurred textures or the reference image lacks features, the reconstructed image suffers from detail loss or incompleteness[

32].

2.2.2. Methods for TIR Images

Most Ref-SR methods for TIR images adopt HR VIS images as reference images. Compared with TIR images, HR VIS images have lower acquisition costs and contain richer detail information. They can guide the SR process of TIR images and improve reconstruction accuracy and detail consistency[

33].

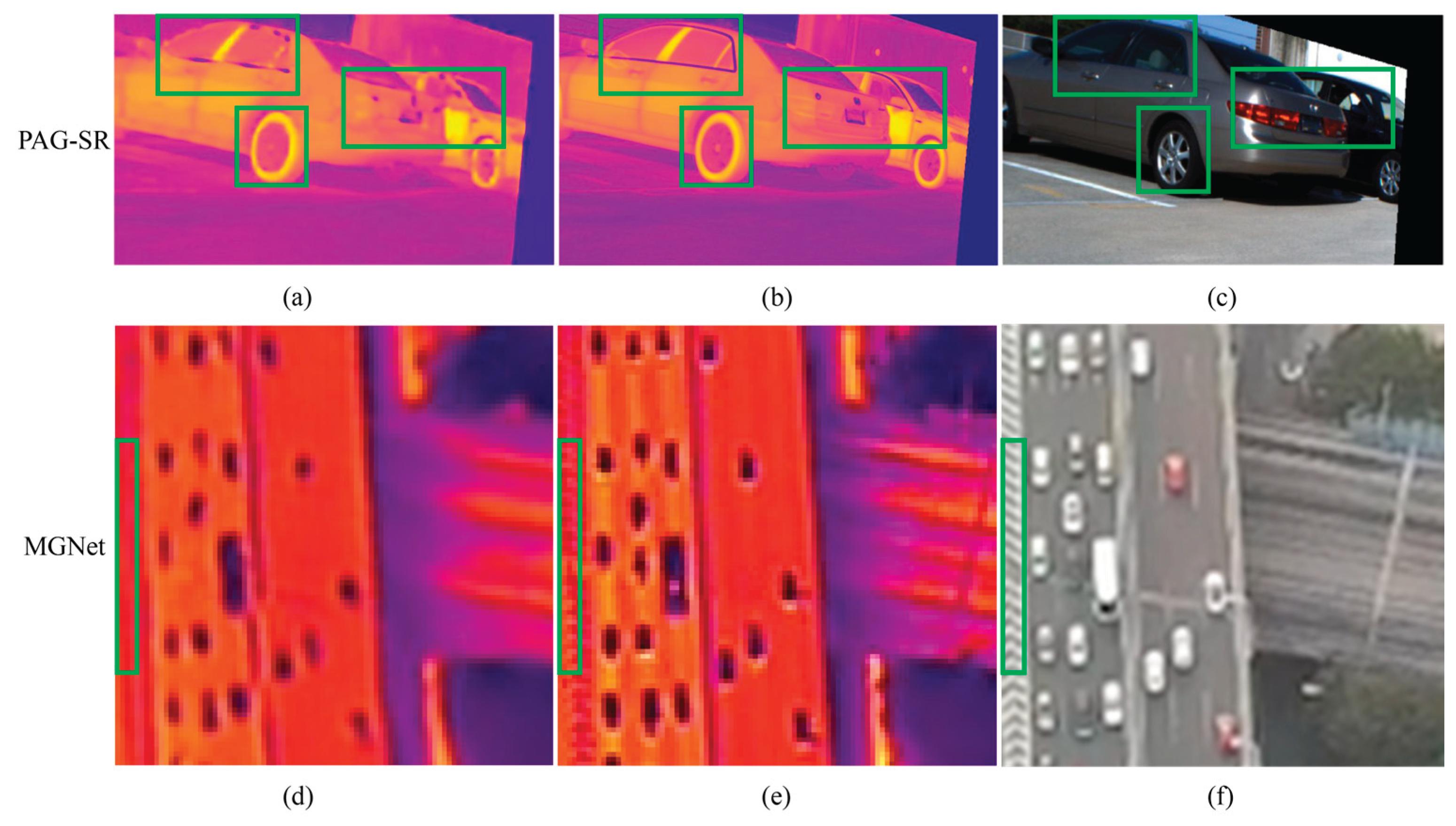

Representative works include the following: Almasri et al.[

34] proposed a GAN-based model, constructing a dual-branch generative network that includes TIR images and corresponding VIS images. It uses the abundant texture details of VIS images as guiding information to enhance the detail reconstruction of TIR images. However, the training instability of GAN may generate false textures, which impairs the authenticity of SR reconstruction. Gupta et al.[

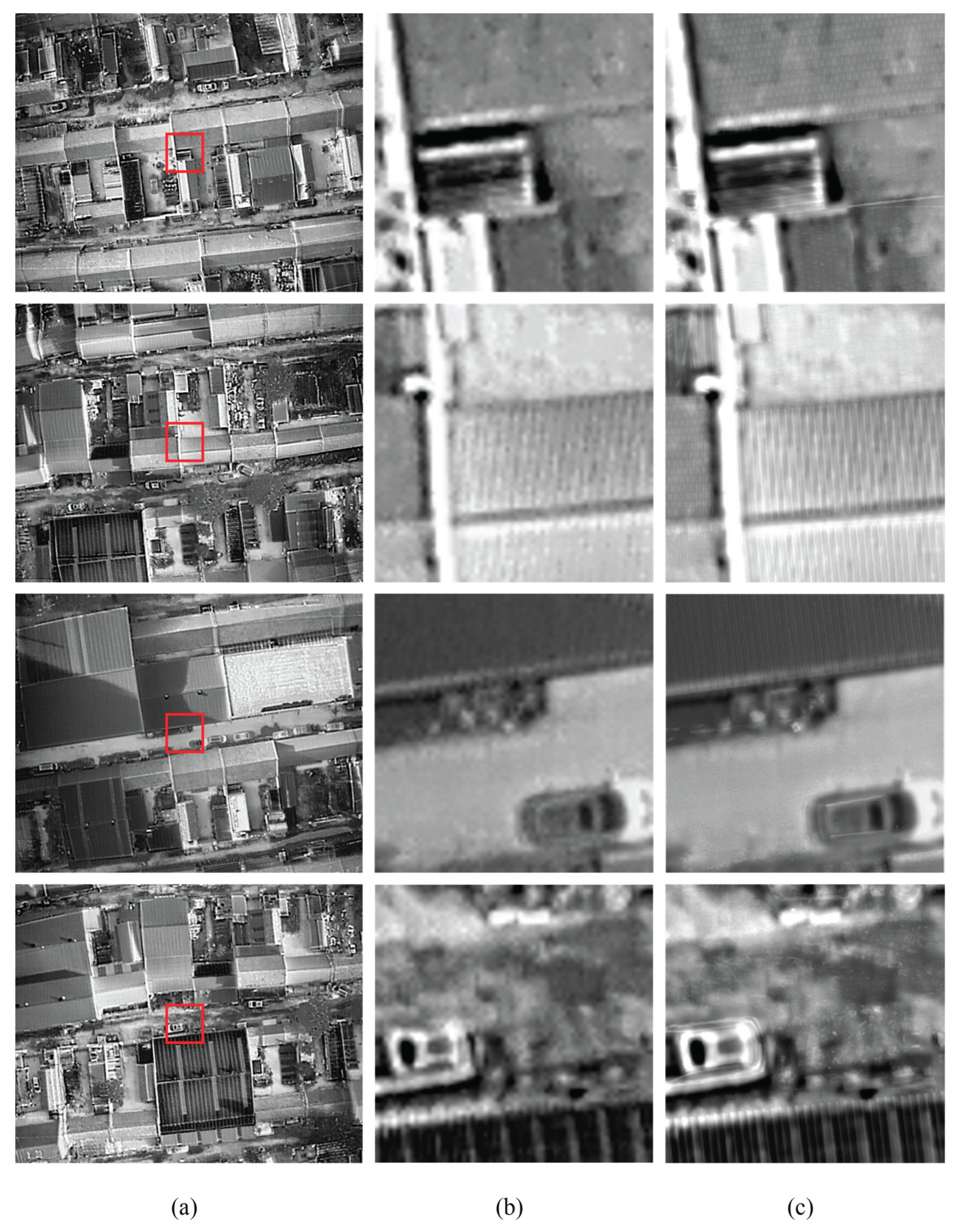

35] proposed the PAG-SR method, focusing on the problems of blurring and artifacts in thermal image SR. It extracts multi-scale edge information from VIS images and adds it to TIR images through an attention fusion module, effectively addressing the uncertainty issue of GAN models. Nevertheless, this method is limited to extracting edge information from VIS images and ignores texture details. As shown in

Figure 1(a), the car surfaces in the reconstructed results exhibit unnatural geometric distortion and texture confusion. Zhao et al.[

6] proposed the MGNet method, which extracts information from VIS images in three aspects: ground object categories, edge information, and deep features, providing multi-faceted guidance for the SR reconstruction of TIR images. It achieves good reconstruction results in terms of details and structure but still suffers from partial texture loss. As shown in

Figure 1(d), compared with the real HR image in

Figure 1(e), the ground markings are missing in the reconstructed image. In addition, this method focuses on extracting information from VIS images without considering the temperature information of TIR images, failing to maintain the temperature consistency of TIR images before and after reconstruction, which makes it difficult to meet the needs of application scenarios highly dependent on temperature information.

In general, existing Ref-SR methods for TIR images not only share the same problems as SISR methods but also have the following two additional issues:

Neglect the physical differences between VIS and TIR images: The HR of VIS images stems from the representation of color differences, while that of TIR images originates from the reflection of temperature differences. Different colors or textures in VIS images may correspond to the same temperature. Therefore, transferring different colors or textures will cause temperature changes in TIR images, thereby damaging the temperature consistency before and after SR. Existing methods often treat all colors or textures to be transferred equally, failing to consider the inherent thermal radiation characteristics of objects and unable to maintain the authenticity of temperature information while enhancing detail performance.

In addition, during the transfer of VIS features, the transfer of internal detailed textures is insufficient. As a result, the super-resolved TIR images mainly improve the clarity of the overall edge parts, while the internal details remain relatively blurred, as shown in

Figure 1.

Since fusing VIS can also enhance the resolution of TIR images, we briefly review the relevant research work on image fusion below.

2.3. VIS and TIR Image Fusion Methods

In recent years, image fusion has achieved extensive development in the field of image processing. In the remote sensing domain, the fusion of multi-source remote sensing data has also yielded remarkable results. For instance, Shopovska et al.[

36] extracted saliency maps of pedestrians from TIR and VIS images through a saliency detection network, guiding a residual convolutional fusion network to fuse the dual-modal images into an RGB-style output. This visually highlights pedestrian target regions but fails to preserve the temperature information in the original TIR images. Xu et al.[

37] proposed a fusion method based on frequency-domain filtering, which achieves image fusion by extracting high-frequency details from VIS images and low-frequency distributions from TIR images in the frequency domain. While this improves the detail performance of the fused images, it does not introduce temperature consistency constraints, resulting in fused results that only reflect the relative temperature distribution and cannot retain the physically meaningful absolute temperature information in TIR images.

On UAV platforms, synchronously acquired VIS and TIR images share similar structural features. Their fusion can overcome the inherent limitations of each modality. Representative works include the following: Kacker et al.[

38] proposed a GAN-based fusion method, utilizing an improved U-Net architecture to fuse TIR and VIS images, enhancing the robustness of flame detection in complex scenarios. However, the fused images are RGB-style pseudo-color images that cannot well preserve the temperature information of TIR images, making them unsuitable for tasks requiring quantitative thermal analysis. Motayyeb et al.[

39] proposed a TIR and VIS image fusion method based on 3D point cloud registration, realizing point cloud alignment and fusion through SfM (Structure from Motion) and ICP (Iterative Closest Point). The resulting fused orthophotos for monitoring thermal leakage on building facades improve the resolution of TIR images and the accuracy of heat source localization. Nevertheless, the fused results only reflect the relative differences in temperature distribution and cannot obtain absolute temperature information, limiting their application in tasks such as quantitative energy consumption analysis.

In general, existing VIS and TIR image fusion methods do not fully consider maintaining the temperature consistency of TIR images before and after fusion. Additionally, compared with the aforementioned SR methods, existing fusion methods generally focus on the contribution of VIS information to structural details and visual perception. However, introducing excessive VIS features during the fusion process will weaken the application value of temperature information in TIR images.

To address the problems of existing methods, this paper proposes a SR method that does not require HR TIR images as ground truth for supervision. The core idea of the method is to decouple the enhancement of basic structures from the transfer of detailed textures. This fully leverages the advantages of diffusion models in restoring basic components, while introducing a multi-scale texture extraction and emissivity-guided selective transfer strategy. Under the premise of maintaining temperature information consistency as much as possible, VIS textures are gradually transferred to TIR images, achieving SR enhancement of UAV TIR images.

3. Methods

The method proposed in this paper consists of three core modules: (1) the Multi-Stage Decomposition Latent Low-Rank Representation (MS-DLatLRR) module, which is used to extract multi-scale texture details from VIS images; (2) the Prior-Information Emissivity-Guided Coefficient Mapping (PI-EGCM) module, which calculates the transfer intensity of texture information in VIS images while maintaining temperature consistency as much as possible; (3) the Multi-Prior constrained Denoising Diffusion Null-Space Model (MP-DDNM) module , which realizes SR reconstruction and noise suppression of TIR images. These three modules cooperate with each other to jointly improve the resolution and texture details of TIR images while ensuring the authenticity of temperature information.

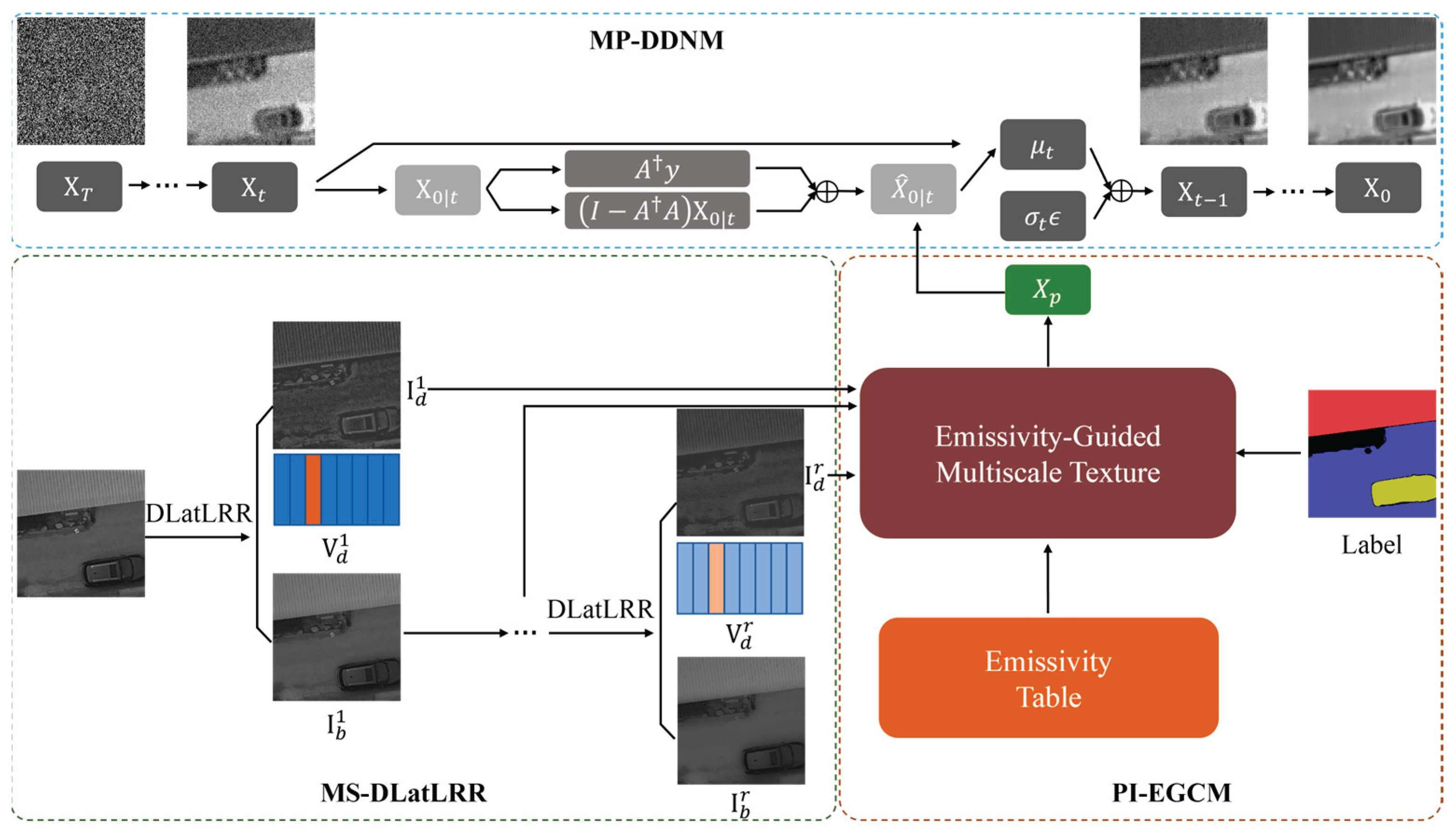

Figure 2 shows the overall workflow of the method.

First, considering that convolutional neural networks may suffer from structural distortion or feature loss during feature extraction, we designed a more interpretable Multi-Stage Decomposition Latent Low-Rank Representation (MS-DLatLRR) module to extract multi-scale texture details from VIS images. Compared with CNN-based feature extraction methods, DLatLRR can decompose more natural texture features through mathematical optimization based on the local self-similarity of images, avoiding artifact problems that neural networks may introduce. Meanwhile, we adopt a multi-stage decomposition strategy to address the issue that a single decomposition cannot fully extract multi-level details. We reconstruct the detail vector matrices obtained from each decomposition separately to obtain a sequence of multi-scale detail images, forming a coarse-to-fine multi-scale feature representation.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the overall workflow, including (1) Multi-Stage Decomposition Latent Low-Rank Representation (MS-DLatLRR); (2) Prior-Informed Emissivity-Guided Coefficient Mapping (PI-EGCM); (3) Multi-Prior constrained Denoising Diffusion Null-Space Model (MP-DDNM).

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the overall workflow, including (1) Multi-Stage Decomposition Latent Low-Rank Representation (MS-DLatLRR); (2) Prior-Informed Emissivity-Guided Coefficient Mapping (PI-EGCM); (3) Multi-Prior constrained Denoising Diffusion Null-Space Model (MP-DDNM).

Second, given the insufficient attention paid to the temperature consistency of TIR images before and after SR in existing studies, we designed the Prior-Informed Emissivity-Guided Coefficient Mapping (PI-EGCM) module based on prior information such as material emissivity and ground object classification. This module calculates the intensity of VIS texture transfer according to the thermal radiation characteristics of different ground objects, thereby realizing certain constraints on temperature consistency before and after SR during the texture transfer process.

Finally, inspired by Ho et al.[

40] and Wang et al.[

41] , we adopted a diffusion model as the backbone network for SR and constructed the Multi-Prior Constrained Denoising Diffusion Null-Space Model (MP-DDNM). Compared with the limitation of traditional deep learning methods that rely on HR ground truth for supervision, this model progressively guides the SR reconstruction of TIR images by introducing a series of VIS texture prior maps. It can break through the strong dependence on HR TIR ground truth images and improve the practical application value of TIR image SR technology.

3.1. Multi-Stage Decomposition Latent Low-Rank Representation(MS-DLatLRR)

3.1.1. Fundamental Principles, Advantages, and Limitations of DLatLRR

The DLatLRR method is based on the Latent Low-Rank Representation (LatLRR) theory, performing decomposition on the input image to obtain the image's detailed information. Specifically, the LatLRR theory formulates the image decomposition problem as an optimization problem expressed by the following formula:

Here, λ denotes the balance coefficient, represents the nuclear norm (i.e., the sum of the singular values of a matrix), and indicates the norm. X denotes the observed data matrix, Z is the low-rank coefficient matrix, L is the projection matrix, and E is the sparse noise matrix.

To decompose the texture details in VIS images, the DLatLRR method needs to use the projection matrix

L to extract texture features from the observed data matrix

X. In specific implementation, image patches

p are first extracted using a sliding window of size

n×

n with a step size of

s. Each image patch is converted into a column vector and stacked into a matrix

P , which is expressed as:

where vec(

p) denotes the vectorization of image block

p, and

M represents the number of image patches, and

R denotes the real matrix space. After converting the image

I into a matrix

P(

I) suitable for LatLRR decomposition, the texture features

are extracted using the projection matrix

L learned by LatLRR:

Here,

is the detail vector matrix, representing the extracted texture features. Each column of

corresponds to the vector representation of a detail image patch. By reconstructing the extracted texture features back into the image space, the detail image

of the original image

I is obtained.

where

R(·) denotes the image reconstruction operation, which reshapes the texture features in the vector space into image patches, splices them back into the image space, and takes the pixel-wise average of overlapping regions. On this basis, the base image

containing the low-rank structure can be obtained by subtracting the detail component from the original image

I:

Through the above operations, the DLatLRR method can effectively separate the image texture details from the low-rank base, providing high-quality decomposed data for subsequent image processing tasks.

Compared with the deep learning methods based on convolutional neural networks (CNNs) adopted in [

34], [

35] and [

6], the DLatLRR method can decompose more natural texture features according to the local self-similarity of images. It avoids the artifact problem that CNNs may introduce, and the extracted features are more consistent with the physical properties of images. In addition, DLatLRR does not rely on large-scale training data and has a stable calculation process, without issues such as gradient vanishing or explosion. It is suitable for processing various types of image data, can better preserve the original structural information of images, and avoids structural distortion or feature loss that may occur when CNNs perform feature extraction.

However, directly applying the DLatLRR method to cross-modal texture transfer tasks has certain limitations. The DLatLRR method usually performs only one decomposition, making it difficult to fully extract the hierarchical multi-scale detail information in images and unable to meet the diffusion model’s demand for multi-scale texture information at different timesteps. For complex VIS images, a single decomposition may fail to fully extract texture details at all levels, especially for weak texture regions, where the extraction effect is limited. Furthermore, the generation process of diffusion models has phased characteristics: early timesteps require strong texture information, while late timesteps need weak texture information, which cannot be provided by a single decomposition. Therefore, direct application of DLatLRR is difficult to meet the requirements of TIR image SR.

3.1.2. MS-DLatLRR: Multi-stage Decomposition Strategy

Inspired by Lee et al.[

23], we convert the VIS image I from the RGB color space to the HSV space. We then utilize the brightness channel most similar to the TIR channel.

Let

denote the initial base image. For a total of

r decomposition stages, the

i-th decomposition process is as follows:

Among these, is the detail vector matrix of the -th layer. It is obtained by applying a sliding window segmentation of to the base image from the previous layer, followed by vector stacking and projection matrix operation L. denotes the reconstructed spatial detail map for layer , obtained via the reconstruction operator . is the base image for layer , derived by subtracting the detail image from the base image of the previous layer. After r decompositions, we obtain r detail images , representing the texture features extracted from VIS images.

This strategy not only solves the problem of single detail expression in the DLatLRR method but also enhances the multi-scale expression ability of textures through iterative decomposition. Specifically, each decomposition extracts details from the residual base image of the previous layer, thereby obtaining a coarse-to-fine multi-scale feature representation. Early decomposition layers mainly extract prominent edge structures and textures, while late decomposition layers extract low-contrast weak texture regions. This hierarchical multi-scale detail sequence is highly consistent with the iterative generation mechanism of diffusion models that refine images from coarse to fine during inference. Therefore, introducing it into the inference process of diffusion models can better support cross-modal texture transfer.

3.2. Prior-Informed Emissivity-Guided Coefficient Mapping (PI-EGCM)

Due to the physical limitations of TIR sensors, the acquired images generally suffer from low spatial resolution and insufficient texture details. In contrast, synchronously collected VIS images possess higher spatial resolution and abundant texture information, which can reflect key visual features such as the surface material, edges, and geometric shapes of ground objects. Therefore, cross-modal transfer of VIS images to guide the detail reconstruction of TIR images has become an effective strategy to improve the spatial resolution of TIR images.

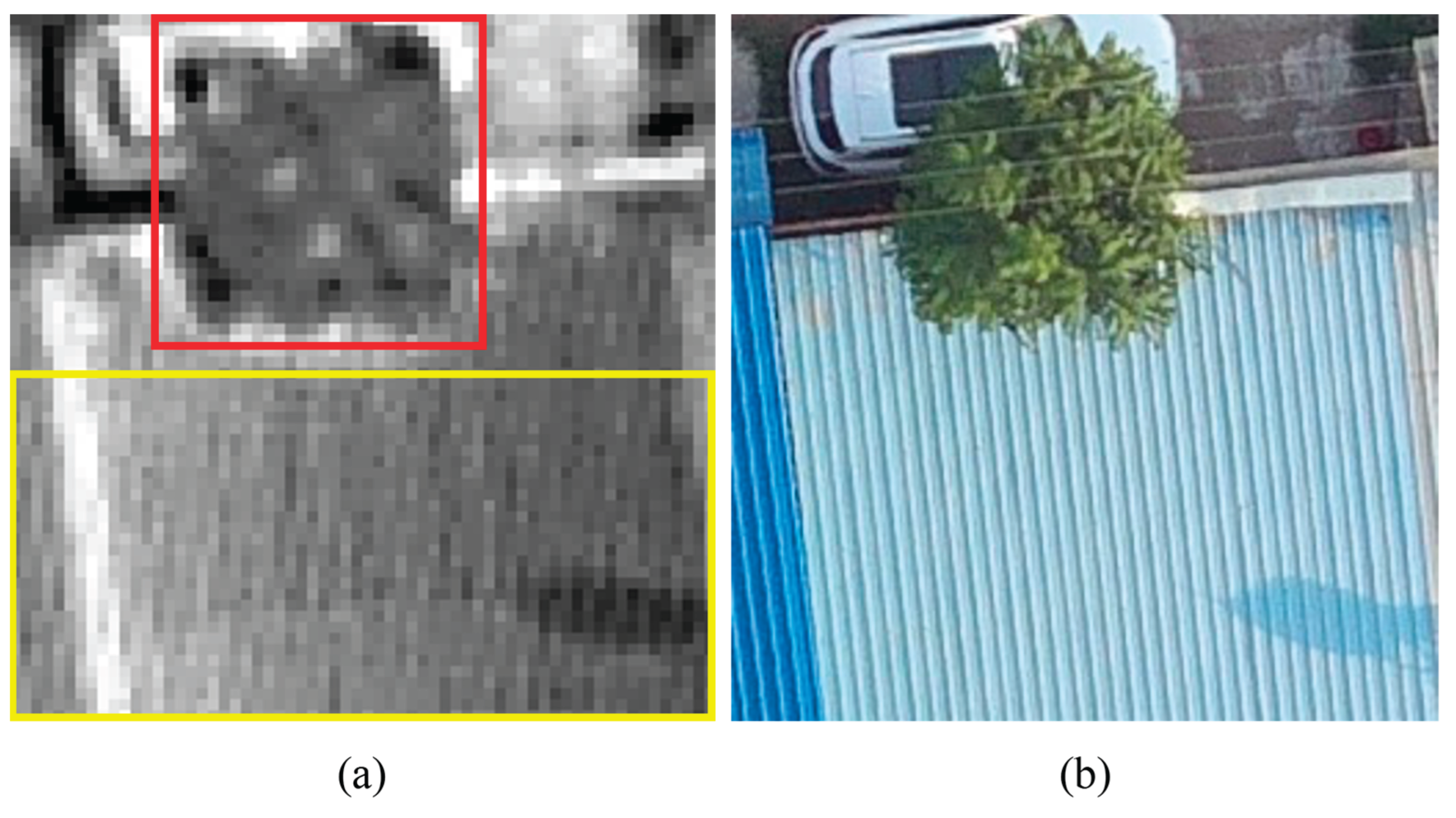

As shown in

Figure 3, different ground objects exhibit significant differences in emissivity. For objects with high emissivity, such as vegetation, TIR images can well reflect the true temperature of the objects. Introducing information from VIS images will significantly reduce the temperature authenticity of TIR images. Thus, it is necessary to reduce the introduction of VIS texture information for such ground objects to maintain their temperature characteristics in TIR images as much as possible. For objects with low emissivity, such as metals, their imaging in TIR images is easily interfered by ambient temperature. Introducing corresponding detail information from VIS images can enhance their texture expression in TIR images.

Meanwhile, considering the differences in imaging mechanisms between VIS and TIR images, we propose an emissivity-guided texture transfer principle. The main purpose of this principle is to avoid the distortion of temperature information in TIR images caused by cross-modal transfer:

- 1.

The texture changes in VIS images reflect the changes in material and structure to a certain extent, and such changes have a certain similarity to the temperature changes in TIR images;

- 2.

Ground objects of different materials in VIS images generally have different thermal radiation characteristics. During the texture transfer process, different conversion coefficients can be assigned to express this difference;

- 3.

VIS texture transfer can enhance the details of TIR images, but the temperature consistency of TIR images before and after conversion should be ensured as much as possible.

Based on this principle, we propose a specific VIS texture transfer method as follows:

First, based on the principle of thermal radiation, the radiation value received by the TIR sensor under ideal conditions satisfies the following formula:

where

T denotes the thermal radiation value received by the TIR sensor, reflecting the radiometric temperature of the detected object; ε∈[0,1] denotes the emissivity of the object, reflecting the object’s ability to radiate heat;

denotes the true temperature of the object;

denotes the equivalent temperature of environmental radiation, reflecting the thermal reflection effect of the environment on the object’s surface.

Figure 3.

TIR images and VIS images of different land cover types. The vegetation in the red box has high emissivity, and its imaging process is less affected by ambient temperature; the metal in the yellow box has low emissivity, which is greatly affected by ambient temperature and exhibits obvious noise.

Figure 3.

TIR images and VIS images of different land cover types. The vegetation in the red box has high emissivity, and its imaging process is less affected by ambient temperature; the metal in the yellow box has low emissivity, which is greatly affected by ambient temperature and exhibits obvious noise.

Formula (9) clarifies that the observed temperature of an object is the weighted sum of the object’s own radiation and environmental radiation, where the weight is related to the emissivity ε. This provides a solid theoretical basis for introducing differentiated conversion coefficients in cross-modal transfer.

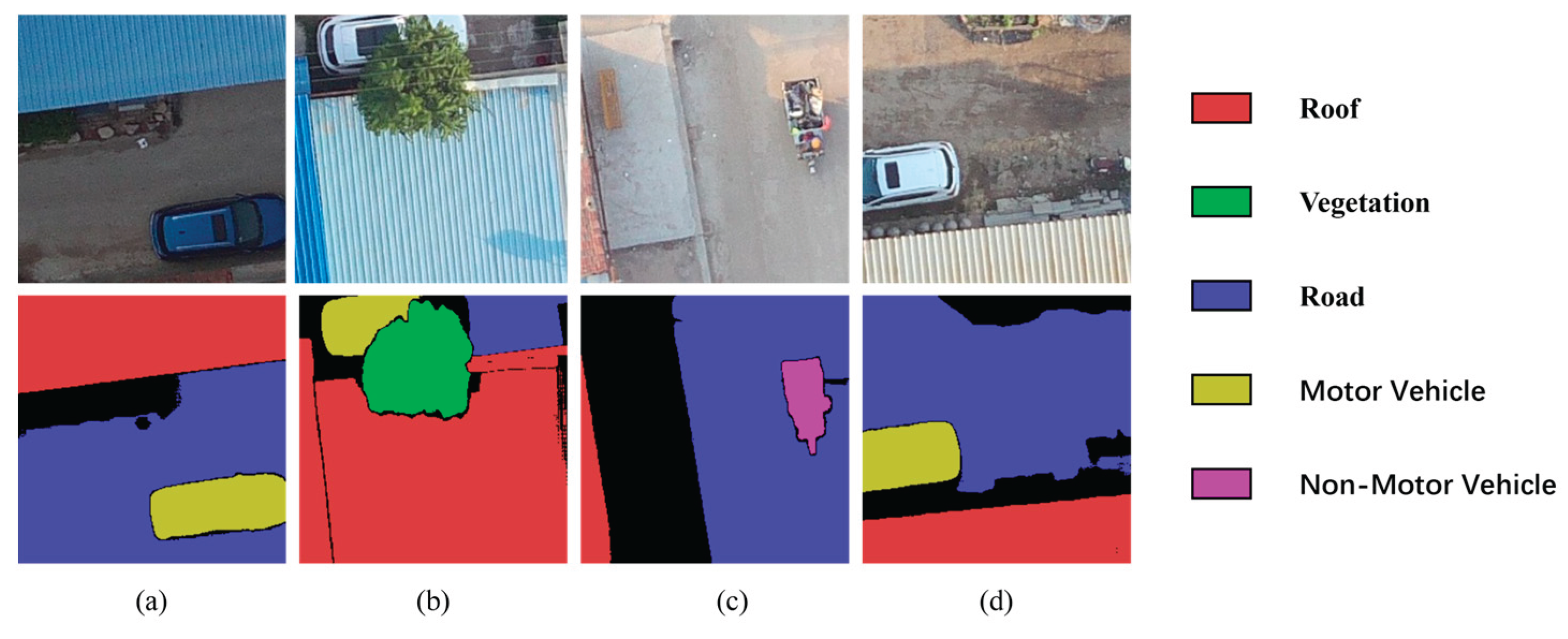

Second, for VIS images, we use a semantic segmentation algorithm to obtain a ground object classification map (as shown in the second row of

Figure 4). Assuming the ground object category at pixel

is

, it should satisfy a mapping relationship with thermal emissivity ε., namely:

Studies have shown that the mapping function f(·) in this formula is difficult to obtain. Therefore, in general, ε is estimated based on ground object classification results and thermodynamic prior knowledge[

42].

Third, we calculate the conversion coefficient for texture transfer based on the emissivity of ground objects.

Transforming formula (9), we can get:

Formula (11) shows that 1-ε is numerically equal to the ratio of "the difference between the true temperature and the detected temperature" to "the difference between the true temperature and the environmental temperature". This relationship has a clear physical meaning: it measures the proportion of the detection deviation caused by environmental radiation to the theoretically maximum possible deviation. The larger this ratio, the more severely the TIR signal here is disturbed by the environment, and the less effective detail information it can provide on its own, thus requiring more supplementary VIS detail information. Therefore, we take 1-ε as the conversion coefficient ω for the intensity of VIS texture transfer.

Figure 4.

Land cover classification map of VIS images.

Figure 4.

Land cover classification map of VIS images.

As shown in

Figure 4, assuming the TIR image is perfectly aligned with the VIS image to be transferred, for any pixel

in the TIR image, if the emissivity of the corresponding ground object is

, the conversion coefficient

of the VIS detail image is defined as:

The design of this formula follows the principle: the higher the emissivity ε of the ground object, the smaller the conversion coefficient ω. Formula (9) indicates that for objects with high emissivity (ε approaching 1), , meaning they are dominated by their own thermal radiation, and their TIR information has high physical fidelity. Therefore, stronger constraints should be imposed during texture transfer to avoid damaging their physical authenticity. Conversely, for objects with low emissivity (ε approaching 0), , meaning they are dominated by environmental thermal radiation, and their TIR information is susceptible to environmental interference with significant uncertainty, thus showing higher tolerance for the introduction of VIS textures.

By calculating the conversion coefficient of the VIS image to be transferred pixel by pixel, a complete prior information-based emissivity-guided coefficient map can be obtained, providing support for subsequent accurate texture transfer based on the diffusion model.

3.3. Multi-Prior Constrained Denoising Diffusion Null-Space Model (MP-DDNM)

Considering that diffusion models, despite their powerful generative capabilities and robustness to complex data distributions, struggle to directly and accurately transfer multi-scale texture prior information from VIS images through their standard conditional denoising process, we propose the Multi-Prior Constrained Denoising Diffusion Null-Space Model (MP-DDNM). Based on the Diffusion Denoising Probabilistic Model (DDPM), this method takes the multi-scale detail information extracted by MS-DLatLRR and the guided coefficient map ω generated by PI-EGCM as prior information. It introduces them in a phased and region-adaptive manner during the inference process of the diffusion model, enhancing the details of the generated image using cross-modal prior information while strictly retaining the conditional constraints of the LR TIR input.

According to the basic framework of the diffusion model defined in the Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Model (DDPM) proposed by Ho et al.[

40], the diffusion model consists of a T-step forward process and a T-step reverse process. The forward process gradually adds random noise to the data, while the reverse process sequentially estimates and removes the noise to generate the required image data. In the forward process, the current state

is obtained by gradually adding noise:

where

is calculated from the preset scaling factor

:

The reverse process sequentially estimates

from

through the posterior distribution to gradually restore the image:

Here,

is the estimated value of

at timestep

t derived from Formula (13), i.e.:

Reconstructing the original image directly from the noisy image is a single mapping, making it difficult to balance the reconstruction authenticity and data consistency of the image. Therefore, Wang et al.[

41] introduced the theory of Range-Null Space Decomposition (RND). In the RND theory, an image can be decomposed into a range space component and a null space component, representing data consistency and authenticity, respectively. In the entire image, data consistency reflects the basic structural features of the image, while authenticity reflects the finer detail features. For image SR tasks without considering additional noise, it can be described by a linear model:

Here,

,

,

denote the HR ground truth image, the linear degradation operator, and the LR degraded image, respectively, and

represents the real matrix space. In the process of solving the super-resolved image from the LR image

y, two constraints need to be satisfied to ensure the quality of image SR:

where

denotes the data distribution of the HR ground truth image. Formula (18) describes data consistency, meaning that the super-resolved image must be consistent with the input LR image after being processed by the degradation operator. Formula (19) describes data authenticity, meaning that the super-resolved image should conform to the data distribution of the input image. Through a series of derivations, the correction formula for

is given as:

where

is the pseudoinverse of

A, and

is the corrected value of

obtained through range-null space decomposition, including including the range-space term

and the null-space term

.

To achieve the synergy between multi-scale texture priors and the diffusion generation process, we designed a dynamic regulation scheme for the inference phase of MP-DDNM. Considering that image generation by diffusion models is an iterative denoising process from coarse to fine—early timesteps mainly generate the overall contour and structural information of the image, while late timesteps focus on the restoration and refinement of detailed textures—we introduce the multi-scale decomposition results as prior constraints into the stepwise adjustment process of the diffusion model for more effective detail transfer and structural guidance.

Specifically, we perform r iterative decompositions on VIS images using the MS-DLatLRR method to obtain a sequence of multi-scale detail images . Among them, early decomposition layers (e.g., ) mainly extract prominent structural edges and strong textures in the image, while late decomposition layers (e.g., ) extract low-contrast weak texture regions. This multi-scale representation transitioning from high-intensity structural features to subtle texture features is highly consistent in mechanism with the iterative generation logic of diffusion models, which refines from rough contours to detailed perfection during inference.

Therefore, to establish a temporal correspondence between multi-scale priors and diffusion inference phases, we designed a timestep mapping guidance strategy. This strategy maps the sequence of multi-scale detail images to corresponding timesteps in the diffusion process, and converts each corresponding detail image into a prior constraint term for the timestep , thereby realizing the gradual transfer and dynamic regulation of VIS image details. Unlike image fusion, we do not directly perform linear combination of image pixels; instead, we achieve fine-grained regulation of the generation process and enhancement of semantic consistency through the structural guidance of cross-modal prior information on the diffusion path. This guidance method not only finely regulates the generation process to avoid artifacts or modal conflicts caused by simple fusion but also effectively preserves the inherent temperature distribution characteristics of TIR images, thereby enhancing the semantic consistency and physical authenticity of SR results.

The specific implementation for MP-DDNM is as follows:

During DDNM inference, assuming the total number of inference steps is

T, we divide it into

r phases, with each phase having a timestep interval of

. For the

i-th phase, the corresponding starting timestep is

At this timestep, the

i-th layer detail image

is converted into the prior constraint term

. Specifically, we perform element-wise multiplication (i.e., Hadamard product, denoted as ⊙ between

and the emissivity-guided coefficient map

ω generated by the PI-EGCM module to obtain the prior constraint term

for this layer:

Here, ⊙ denotes the operation of multiplying corresponding elements of two matrices. During different phases of DDNM inference, are sequentially introduced into the inference process. Thus, this strategy manifests as phase-wise regulation in the time domain and region-aware adaptive regulation in the spatial domain.

To enhance the texture features of TIR images, we introduce the prior constraint term

containing VIS image texture information at specific timesteps, modifying formula (22) as follows :

Since the sampling operation of the diffusion model is performed in the latent space, injecting the prior information into the null space will not affect the data consistency of the known range space term . The prior constraint term performs region-adaptive adjustment on the texture information of VIS images to enhance the detail expression of TIR images within the null space and guide the generation process, making the reconstructed results better conform to the distribution of real HR images, thereby improving the data authenticity of the reconstruction.

Through the dual regulation of temporal guidance and region adaptation, we achieve the joint constraint of multi-scale details on inference timesteps and spatial positions. This enables the texture details in VIS images to be gradually transferred to key phases of the diffusion model generation process while maintaining the temperature consistency of TIR images, enhancing the detail expression ability and structural integrity of super-resolved images.

The algorithm flow of MP-DDNM is shown in

Table 1.

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Platform and Dataset

The hardware platform used in our experiments is a DELL PowerEdge T640 tower server, with the main configurations as follows: the CPU consists of 4 Intel Xeon Silver 4116 processors with a base operating frequency of 2.10 GHz; the system memory is 128 GB with a working frequency of 2666 MHz; the GPU includes 2 NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090D cards, each equipped with 24 GB of G6X video memory. The PyTorch framework is adopted for the implementation of deep learning models.

Existing paired UAV TIR and VIS datasets are mainly used for target detection and tracking. There is still a lack of high-quality datasets tailored for cross-modal image reconstruction, especially for TIR image SR. For example, the VGTSR dataset established by Zhao et al.[

6] is mainly collected in the core urban areas with dense high-rise buildings. Limited by the high flight altitude of UAVs and the limited imaging resolution of the equipped VIS sensors, the ground details in VIS images exhibit blurred textures and weakened edges, which are difficult to meet the requirements of tasks such as texture transfer. In addition, a large number of shadowed areas formed by the occlusion of high-rise buildings in urban environments further interfere with the integrity of ground object texture extraction in VIS images and reduce the transfer accuracy of detailed structures. The existence of shadowed areas leads to blurred ground object boundaries, affecting the accuracy of semantic segmentation and thus the accurate estimation of emissivity.

Therefore, we collected a dataset containing 300 pairs of UAV VIS and TIR images using a DJI M300 UAV and a DJI ZENMUSE XT2 camera, as shown in

Figure 5. The shooting scenes mainly cover rural areas in the evening to effectively reduce the interference of flight altitude and high-rise building shadows on image quality. The original resolutions of the VIS and TIR images collected by the UAV are 4000×3000 and 640×512, respectively. To ensure the spatial alignment and content fidelity of different modal images, we cropped a 64×64 resolution window area at the center of each TIR image as the TIR image dataset for experiments. Meanwhile, we scaled and cropped the VIS images for alignment, obtaining a VIS image dataset with a resolution of 256×256, as shown in

Figure 6 (a) and (b).

Furthermore, we employed the Segment Anything Model(SAM) to perform semantic segmentation on the VIS images. This process extracted and annotated five typical ground object categories: roofs, vegetation, roads, motor vehicles, and non-motorized vehicles. These semantic labels provide the foundational ground truth for mapping material-specific thermal emissivity in the subsequent PI-EGCM module.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics and Parameter Configuration

To comprehensively evaluate the reconstruction effect of super-resolved images, we used traditional full-reference metrics represented by Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) and Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM), as well as perceptual quality metrics represented by Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS) and Natural Image Quality Evaluator (NIQE). Quantitative analysis of reconstruction results was conducted from two aspects: pixel accuracy and visual perception quality. Meanwhile, to further distinguish our SR reconstruction method from image fusion methods, we used Mean Squared Error (MSE) to measure the temperature consistency during the reconstruction process.

For parameter configuration in the MP-DDNM model: we adopted a linear noise scheduling strategy and manually constructed an average pooling operator for the SR task , thereby obtaining a concise pseudoinverse operator . The model was fine-tuned based on a 256×256 resolution denoising diffusion model pre-trained on the ImageNet dataset. Experimental verification shows that setting the number of timesteps achieves a good balance between inference quality and computational efficiency. The start and end points of the linear noise schedule are set to and , respectively, to ensure the smoothness of the noise addition process. For each timestep, we set the noise intensity parameter of the observed image, thereby gradually smoothing the noise disturbances in the original image during inference and improving the model's adaptability to real noise environments.

In the MS-DLatLRR model: we adopted a sliding window strategy for image block processing, setting the sliding window size n=16 and sliding step s=1 to achieve high-density local feature extraction. For the decomposition structure, we set the number of decomposition layers r=4 and the regularization term weight λ=0.4 to extract multi-scale detail features.

In the PI-EGCM module: we referenced existing thermal emissivity statistical tables to assign representative thermal emissivity values to the land cover categories obtained through semantic segmentation, as shown in

Table 2.

5. Results

To verify the comprehensive performance of the proposed method in detail reconstruction and temperature consistency preservation, we conducted comparative analyses with representative image SR and image fusion methods that have publicly available code. The SR methods include ESRGAN, Real-ESRGAN, TTSR, and DDNM, while the image fusion method is represented by MDLatLRR. Through comparisons of quantitative metrics and visualization results, we comprehensively evaluated the performance of these methods in TIR image SR reconstruction tasks.

To avoid evaluation biases caused by synthetic degradation, we used our self-constructed paired dataset of real-scene TIR and VIS images for evaluation. Unlike most existing SR methods, we did not use LR TIR images synthesized through idealized degradation methods such as bicubic downsampling; instead, we directly adopted originally collected TIR images for SR reconstruction. This scheme aligns with practical application scenarios and has higher practical value.

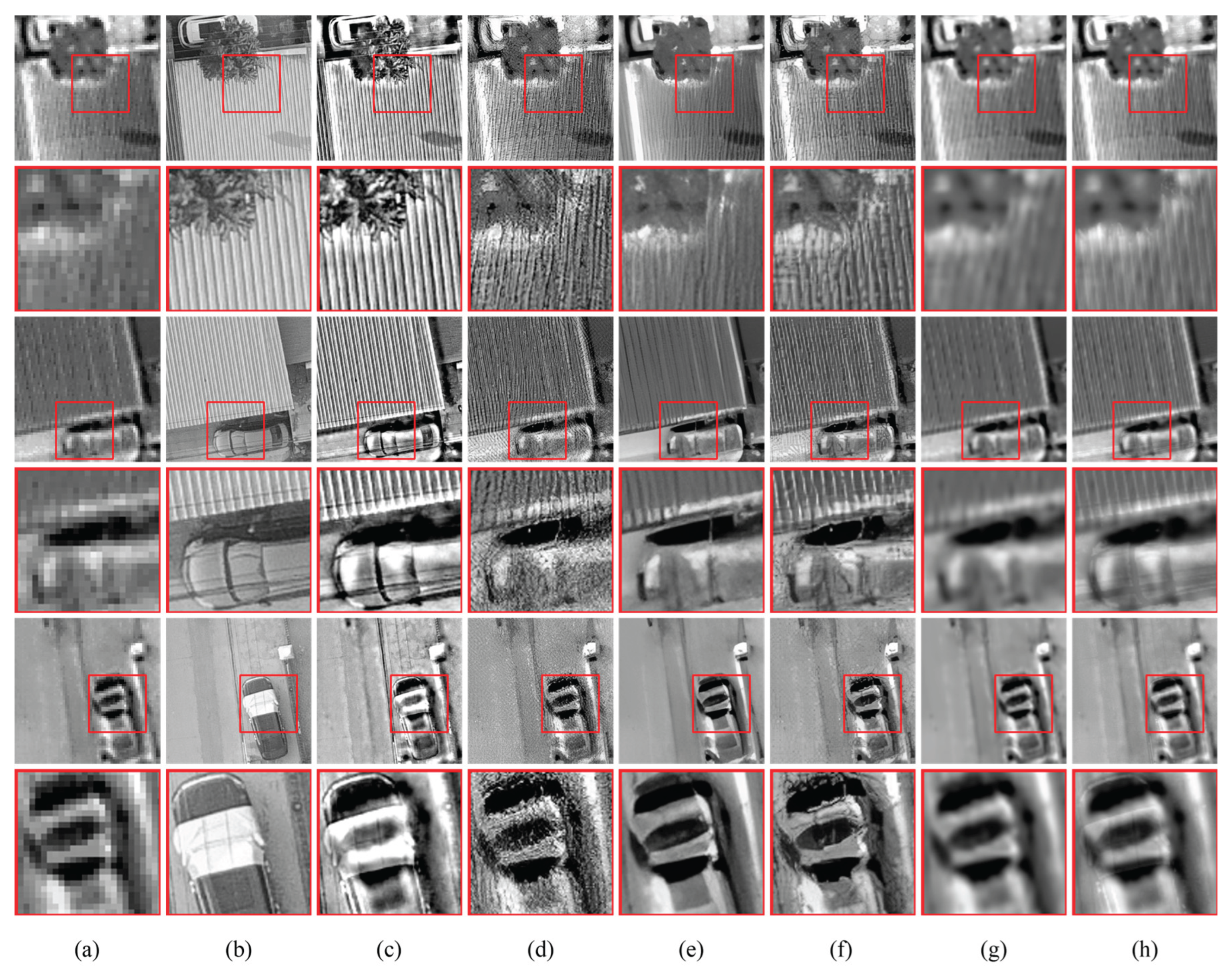

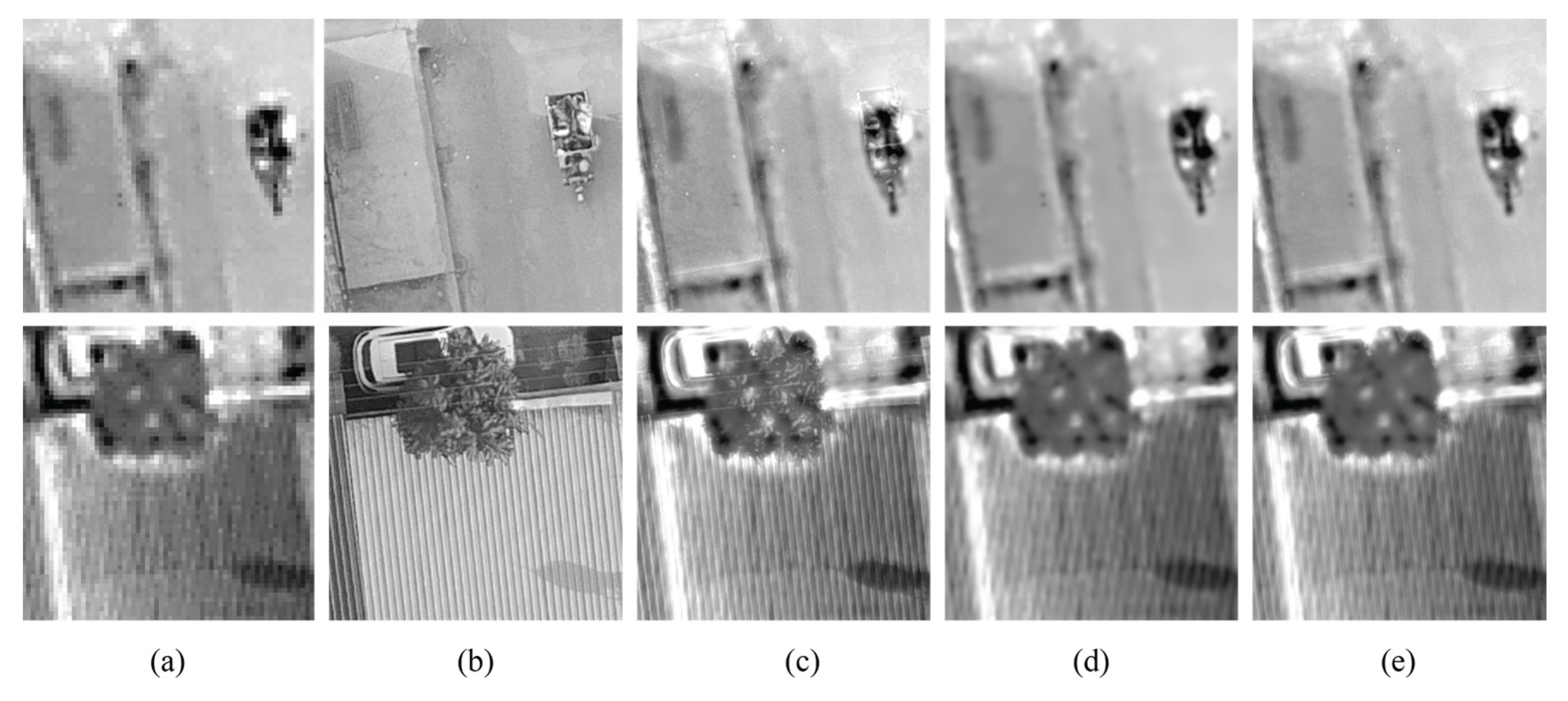

Figure 6 shows the visual effect comparison between our method and other methods. It can be observed that all methods enhance image clarity and structural information to varying degrees, with larger-scale effect diagrams provided in

Figure A1 of

Appendix A. To more intuitively observe the performance of reconstructed images at the detail level, we enlarged local regions of the images in Rows 6, 7, and 8 of

Figure 6 in

Figure 7. Comparative analysis reveals that GAN-based methods such as ESRGAN and Real-ESRGAN, while enhancing image visual quality, tend to introduce messy pseudo-texture noise or over-smoothed regions, leading to significant local detail distortion. TTSR uses reference image guidance for texture matching and transfer, which can enhance detail information to a certain extent. However, in cross-modal scenarios, due to semantic and structural differences between the reference VIS image and the TIR image to be super-resolved, texture transfer lacks accuracy, resulting in distortion phenomena such as structural misalignment. As an unsupervised image reconstruction method based on diffusion models, DDNM mainly focuses on the reconstruction of the base component, lacking explicit modeling and guidance for texture information. The generated images are overall smooth without obvious artifacts but have blurred texture details, lacking sufficient texture richness and local detail information.

In contrast, our method can better reconstruct texture details of structural ground objects such as roofs and vehicles while ensuring temperature consistency. Meanwhile, it achieves fidelity for high-emissivity regions such as vegetation, avoiding the impact of excessive texture guidance from VIS images on temperature authenticity, and realizing a balance between detail enhancement and temperature preservation.

Figure 6.

Comparison of our method with existing image fusion and SR techniques. (a) Original TIR image; (b) VIS brightness image; (c) MDLatLRR; (d) ESRGAN; (e) Real-ESRGAN; (f) TTSR; (g) DDNM; (h) ours.

Figure 6.

Comparison of our method with existing image fusion and SR techniques. (a) Original TIR image; (b) VIS brightness image; (c) MDLatLRR; (d) ESRGAN; (e) Real-ESRGAN; (f) TTSR; (g) DDNM; (h) ours.

To objectively evaluate the reconstruction performance of the proposed method in TIR image SR tasks, we adopted five commonly used metrics for quantitative comparison: PSNR, SSIM, LPIPS, NIQE, and MSE. Among them, PSNR, SSIM, and LPIPS are full-reference metrics that require HR ground truth images as references for calculation. Due to the lack of real HR TIR images, we used images generated by bicubic downsampling for SR reconstruction and metric computation. NIQE is a no-reference image quality assessment metric, so it can be directly used to evaluate the reconstruction effect of each method on real degraded TIR images. For temperature consistency evaluation, we used bicubic upsampled images as temperature references, and measured the model’s performance in temperature preservation by calculating the MSE between the reconstruction results and these references.

Table 3 presents the comparative results of the proposed method and several representative methods on these metrics. Analysis of the metric values in

Table 3 shows that DDNM achieved the optimal performance in PSNR and MSE, indicating its significant advantages in pixel reconstruction accuracy and temperature consistency. However, its LPIPS value is as high as 0.422, suggesting that the reconstructed image details are relatively blurred at the perceptual level, lacking subjective visual quality.

Figure 7.

Comparison of local magnifications for rows 6, 7, and 8 in

Figure 6. (a) Original TIR image; (b) VIS brightness image; (c) MDLatLRR; (d) ESRGAN; (e) Real-ESRGAN; (f) TTSR; (g) DDNM; (h) ours.

Figure 7.

Comparison of local magnifications for rows 6, 7, and 8 in

Figure 6. (a) Original TIR image; (b) VIS brightness image; (c) MDLatLRR; (d) ESRGAN; (e) Real-ESRGAN; (f) TTSR; (g) DDNM; (h) ours.

In contrast, the proposed method achieved the best results in SSIM and NIQE, demonstrating superior performance in structural recovery capability and natural perceptual quality. In addition, the proposed method outperformed most comparative methods in LPIPS, showing better texture fidelity. Regarding MSE, although slightly higher than DDNM, it is far superior to other methods, especially image fusion methods like MDLatLRR. This indicates that our method effectively improves detail performance while maintaining temperature consistency.

Comprehensive analysis shows that the proposed method achieves a good balance among multiple metrics. It not only possesses strong structural restoration and detail expression capabilities but also effectively preserves the temperature authenticity of TIR images, fully demonstrating the effectiveness of the multi-scale detail transfer and emissivity-guided transfer strategies.

Table 3.

Quantitative Evaluation Metrics for SR Methods.

Table 3.

Quantitative Evaluation Metrics for SR Methods.

| Method |

PSNR |

SSIM |

LPIPS |

NIQE |

MSE |

| MDLatLRR |

14.274 |

0.486 |

0.213 |

14.443 |

2481.403 |

| ESRGAN |

18.549 |

0.482 |

0.202 |

12.406 |

838.669 |

| Real-ESRGAN |

20.181 |

0.553 |

0.256 |

8.948 |

200.911 |

| TTSR |

19.618 |

0.549 |

0.165 |

8.611 |

303.013 |

| DDNM |

21.607 |

0.598 |

0.422 |

10.693 |

10.751 |

| Ours |

20.813 |

0.626 |

0.201 |

8.414 |

72.801 |

6. Discussion

6.1. Ablation Experiments

To further explore the effectiveness and contribution of the design of each core module in the proposed method, this section presents ablation experiments. The role of each module in the overall framework is verified by removing key components.

As shown in

Figure 8 (c), after removing the PI-EGCM module, the lack of emissivity guidance leads to obvious over-bright texture in non-motor vehicle and vegetation areas, and the introduced artifacts seriously damage the physical consistency of the temperature distribution. As shown in

Figure 8 (d), removing the MS-DLatLRR module results in insufficient texture extraction, leading to overall blurred reconstruction results and unclear structures such as roofs and roads. In contrast, as shown in

Figure 8 (e), the complete method proposed in this paper achieves high-quality SR reconstruction with clear details and natural structures while maintaining temperature consistency as much as possible. Therefore, both modules are indispensable for generating high-quality super-resolved image.

Table 4 presents the quantitative evaluation metrics of different ablation experiments. Our complete method achieves the optimal quantitative results. In contrast, the absence of the PI-EGCM module or the MS-DLatLRR module leads to performance degradation. Specifically, removing the PI-EGCM module reduces PSNR and SSIM by 1.961 and 0.118, respectively, while increasing LPIPS, NIQE, and MSE by 0.011, 5.125, and 280.951, respectively. Removing the MS-DLatLRR module decreases PSNR and SSIM by 1.24 and 0.023, respectively, and increases LPIPS, NIQE, and MSE by 0.194, 2.439, and 12.875, respectively.

In summary, the ablation experiments fully verify the rationality and indispensability of each proposed module from both qualitative and quantitative perspectives. The PI-EGCM ensures the physical credibility of cross-modal transfer, and the MS-DLatLRR enables high-quality extraction and transfer of texture features. All modules work synergistically to achieve the superior performance of the proposed method in TIR image SR task.

Table 4.

Quantitative Evaluation Results of Ablation Experiments.

Table 4.

Quantitative Evaluation Results of Ablation Experiments.

| Model Configuration |

PSNR |

SSIM |

LPIPS |

NIQE |

MSE |

| Ours w/o PI-EGCM |

18.852 |

0.508 |

0.212 |

13.539 |

353.752 |

| Ours w/o MS-DLatLRR |

19.573 |

0.603 |

0.395 |

10.853 |

85.676 |

| Ours(full) |

20.813 |

0.626 |

0.201 |

8.414 |

72.801 |

6.2. Texture Transfer Guided by Thermal Emissivity

The PI-EGCM module constructs a weight map using the emissivity of ground objects, enabling region-adaptive regulation of the transfer intensity of VIS textures during the SR reconstruction of TIR images. Experimental results show that this method effectively suppresses temperature drift caused by texture transfer in high-emissivity regions, while enhancing the ability to recover structural details in low-emissivity regions, thereby comprehensively improving the temperature consistency and structural integrity of reconstructed images.

However, the current PI-EGCM module relies on offline-generated land cover classification maps and empirical estimation of emissivity, failing to dynamically perceive fine-grained material differences in scenes. In complex scenarios, emissivity estimation may be inaccurate in certain mixed-material regions or shadowed areas, which in turn affects the accuracy of texture transfer, leading to insufficient local enhancement or detail loss.

In addition, the current conversion function adopts a linear approach, which does not consider nonlinear variation characteristics between different emissivity values nor integrates spatial features such as the inherent structural complexity of VIS images. Therefore, in texture-dense or boundary-blurred regions, weight assignment remains rough, making it difficult to give full play to the refined regulatory role of cross-modal guidance.

To address the above issues, future research can be carried out in two directions. On one hand, consider introducing a material-aware estimation module based on deep neural networks, fusing image semantic information with TIR statistical features to achieve more refined emissivity mapping. On the other hand, further optimize the conversion method by adopting nonlinear mapping functions or adaptive regulation strategies to improve the fitting ability of the weight map to real thermophysical properties, thereby realizing more robust and credible texture transfer regulation.

6.3. Multi-stage Decomposition Latent Low-Rank Representation

Although MS-DLatLRR can extract multi-scale structural texture information from VIS images and guide the detail enhancement of TIR images in different inference stages, it still has certain limitations in texture scale selection and transfer matching. Specifically, the different scale layers (such as edges and weak textures) generated during the low-rank decomposition process are not always strictly aligned with the semantic stages of the diffusion model's generation process. In some regions with blurred textures or missing textures in TIR images, the transferred detail information may be difficult to exert an enhancing effect.

To address this issue, we adopted a phase-correspondence strategy, injecting the i-th layer decomposition map into the -th timestep to achieve progressive structural enhancement. However, the current method relies on a fixed mapping relationship between decomposition layers and timesteps, lacking the ability to adaptively perceive the local structural complexity of target regions, which leads to a certain risk of misalignment in scenes with large texture scale variations.

In addition, the current multi-scale details are still obtained based on fixed decomposition parameters, and the differences between different images have not been fully utilized. In some low-contrast regions, the extracted detail maps may still be insufficient to support obvious structural restoration, and may even introduce artifacts or over-enhancement problems.

In future research, we plan to combine deep perception methods to design a learnable scale adaptation module, which dynamically selects the most suitable texture scale according to the current generation state of TIR images. Meanwhile, we may consider introducing a local attention mechanism to perform perceptual screening of candidate regions before texture transfer, so as to further improve the semantic relevance and spatial consistency of the transferred information.

6.4. Diffusion Generation Process Under VIS Priors

Although the introduction of multi-stage VIS texture priors has significantly improved the detail reconstruction quality of TIR images, MP-DDNM still faces certain challenges in reconstructing regions with complex structures and rapid texture changes. Since this module relies on detail information in VIS images, in regions where textures are extremely sparse in the original TIR images or where there are large VIS-TIR modal differences (such as glass reflections and obstacle edges), the injected priors may not be fully aligned with the TIR structure, thereby causing misleading enhancement or edge artifacts.

To alleviate this issue, we introduce multi-scale VIS detail maps at specific timesteps of the diffusion process and combine them with an emissivity-guided conversion method to control the transfer intensity of prior information phase by phase. This reduces the risk of prior misguidance to a certain extent and improves the model’s adaptability to different ground objects.

However, the current injection method still mainly relies on preset time nodes and static weight maps, lacking the ability to dynamically perceive the current image state and contextual information during the generation process. Therefore, when TIR images have extreme temperature differences, severe imaging degradation, or extreme texture loss, multi-prior injection may still cause structural deviation or overfitting problems.

In subsequent research, we plan to introduce a context-aware regulation strategy, such as using a learnable attention mechanism or a conditional discriminative network to dynamically adjust the intensity and timing of prior injection. In addition, we may consider leveraging inter-frame redundant information in thermal imaging sequences to achieve more stable and semantically consistent prior extraction, thereby further enhancing the spatial continuity and detail expression ability of TIR images.

7. Conclusions

This paper proposes an unsupervised SR method for UAV TIR images that does not require HR ground truth supervision. It innovatively integrates the generative capability of diffusion models in base structure restoration with the advantages of cross-modal texture transfer strategies in detail enhancement. The method consists of three key modules: first, the Multi-Stage Decomposition Latent Low-Rank (MS-DLatLRR) is adopted to extract multi-scale salient texture features from paired VIS images; second, the Prior-Informed Emissivity-Guided Cross-modal transfer Module (PI-EGCM) is designed to realize selective guidance and phased transfer of cross-modal detail information; finally, the Multi-Prior Constrained Denoising Diffusion Null-Space Model (MP-DDNM) is used to achieve structural recovery and noise suppression of TIR images, hereby enhancing detail performance while maintaining the physical consistency of TIR imaging.

In addition, we constructed a paired dataset of VIS-TIR images under real scenarios and conducted systematic quantitative analysis and qualitative comparison experiments. The results show that the proposed method outperforms current mainstream image SR and fusion methods in multiple evaluation metrics. Particularly, it significantly improves detail clarity and structural integrity while maintaining temperature consistency, avoiding common problems such as pseudo-textures and structural mismatches caused by overfitting or cross-modal differences, and exhibits stronger generalization ability and practical value.

Future research can further integrate multi-temporal TIR data, scene semantic understanding, and multi-modal self-supervised pre-training frameworks to enhance cross-scale consistency modeling and detail recovery capabilities. Meanwhile, exploring lightweight deployment schemes will enable real-time application of the model in edge computing scenarios such as UAVs and security detection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.L. and M.S.; Methodology, D.L. and M.S.; Validation, K.C.K; Resources, K.C.K; Data curation, X.W.; Writing—review & editing, D.L., M.S., X.W. and K.C.K; Visualization, X.W.; Supervision, M.S.; Funding acquisition, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 42171327, and supported by the High‐Performance Computing Platform of Peking University.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Figure A1. Comparison of SR results. (a) Original TIR image; (b) Localized enlargement of TIR image; (c) SR result image.

Figure A1.

Figure A1. Comparison of SR results. (a) Original TIR image; (b) Localized enlargement of TIR image; (c) SR result image.

References

- Wilson, A.N.; Gupta, K.A.; Koduru, B.H.; Kumar, A.; Jha, A.; Cenkeramaddi, L.R. Recent Advances in Thermal Imaging and Its Applications Using Machine Learning: A Review. IEEE Sensors J. 2023, 23, 3395–3407. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.X.B.; Rosser, K.; Chahl, J. A Review of Modern Thermal Imaging Sensor Technology and Applications for Autonomous Aerial Navigation. J. Imaging 2021, 7, 217. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, X. Learning Continuous Image Representation with Local Implicit Image Function 2021.

- Almasri, F.; Debeir, O. Multimodal Sensor Fusion In Single Thermal Image Super-Resolution 2018.

- Gupta, H.; Mitra, K. Toward Unaligned Guided Thermal Super-Resolution. IEEE Trans. on Image Process. 2022, 31, 433–445. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; Xiao, Y.; Tang, J. Thermal UAV Image Super-Resolution Guided by Multiple Visible Cues. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing 2023, 61, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Keys, R. Cubic Convolution Interpolation for Digital Image Processing. IEEE Trans. Acoust., Speech, Signal Process. 1981, 29, 1153–1160. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Orchard, M.T. New Edge-Directed Interpolation. IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON IMAGE PROCESSING 2001, 10.

- Ford, C.; Etter, D.M. Wavelet Basis Reconstruction of Nonuniformly Sampled Data. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II 1998, 45, 1165–1168. [CrossRef]

- Irani, M.; Peleg, S. Improving Resolution by Image Registration. CVGIP: Graphical Models and Image Processing 1991, 53, 231–239. [CrossRef]

- Stark, H.; Oskoui, P. High-Resolution Image Recovery from Image-Plane Arrays, Using Convex Projections.

- Schultz, R.R.; Stevenson, R.L. Extraction of High-Resolution Frames from Video Sequences. IEEE Trans. on Image Process. 1996, 5, 996–1011. [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Loy, C.C.; He, K.; Tang, X. Image Super-Resolution Using Deep Convolutional Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2016, 38, 295–307. [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Caballero, J.; Huszár, F.; Totz, J.; Aitken, A.P.; Bishop, R.; Rueckert, D.; Wang, Z. Real-Time Single Image and Video Super-Resolution Using an Efficient Sub-Pixel Convolutional Neural Network 2016.

- Ledig, C.; Theis, L.; Huszar, F.; Caballero, J.; Cunningham, A.; Acosta, A.; Aitken, A.; Tejani, A.; Totz, J.; Wang, Z.; et al. Photo-Realistic Single Image Super-Resolution Using a Generative Adversarial Network. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE: Honolulu, HI, July 2017; pp. 105–114.

- Wang, X.; Yu, K.; Wu, S.; Gu, J.; Liu, Y.; Dong, C.; Qiao, Y.; Loy, C.C. ESRGAN: Enhanced Super-Resolution Generative Adversarial Networks. In Computer Vision – ECCV 2018 Workshops; Leal-Taixé, L., Roth, S., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; Vol. 11133, pp. 63–79 ISBN 978-3-030-11020-8.

- Lugmayr, A.; Danelljan, M.; Gool, L.V.; Timofte, R. SRFlow: Learning the Super-Resolution Space with Normalizing Flow 2020.

- Jo, Y.; Yang, S.; Kim, S.J. SRFlow-DA: Super-Resolution Using Normalizing Flow with Deep Convolutional Block. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW); IEEE: Nashville, TN, USA, June 2021; pp. 364–372.

- Saharia, C.; Ho, J.; Chan, W.; Salimans, T.; Fleet, D.J.; Norouzi, M. Image Super-Resolution via Iterative Refinement 2021.

- Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Chang, M.; Feng, H.; Xu, Z.; Li, Q.; Chen, Y. SRDiff: Single Image Super-Resolution with Diffusion Probabilistic Models 2021.

- Moser, B.B.; Shanbhag, A.S.; Raue, F.; Frolov, S.; Palacio, S.; Dengel, A. Diffusion Models, Image Super-Resolution And Everything: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learning Syst. 2024, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Kim, N.; Hwang, S.; Kweon, I.S. Thermal Image Enhancement Using Convolutional Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS); IEEE: Daejeon, South Korea, October 2016; pp. 223–230.

- Lee, K.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.; Hwang, S.; Lee, S. Brightness-Based Convolutional Neural Network for Thermal Image Enhancement. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 26867–26879. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Tang, R.; Anisetti, M.; Yang, X. A Lightweight Iterative Error Reconstruction Network for Infrared Image Super-Resolution in Smart Grid. Sustainable Cities and Society 2021, 66, 102520. [CrossRef]