Submitted:

22 December 2025

Posted:

23 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Validation of Pluripotent State Prior to Cardiomyocyte Differentiation

2.2. Establishing the Optimal Carfilzomib Dose for hiPSC-CMs Experiments

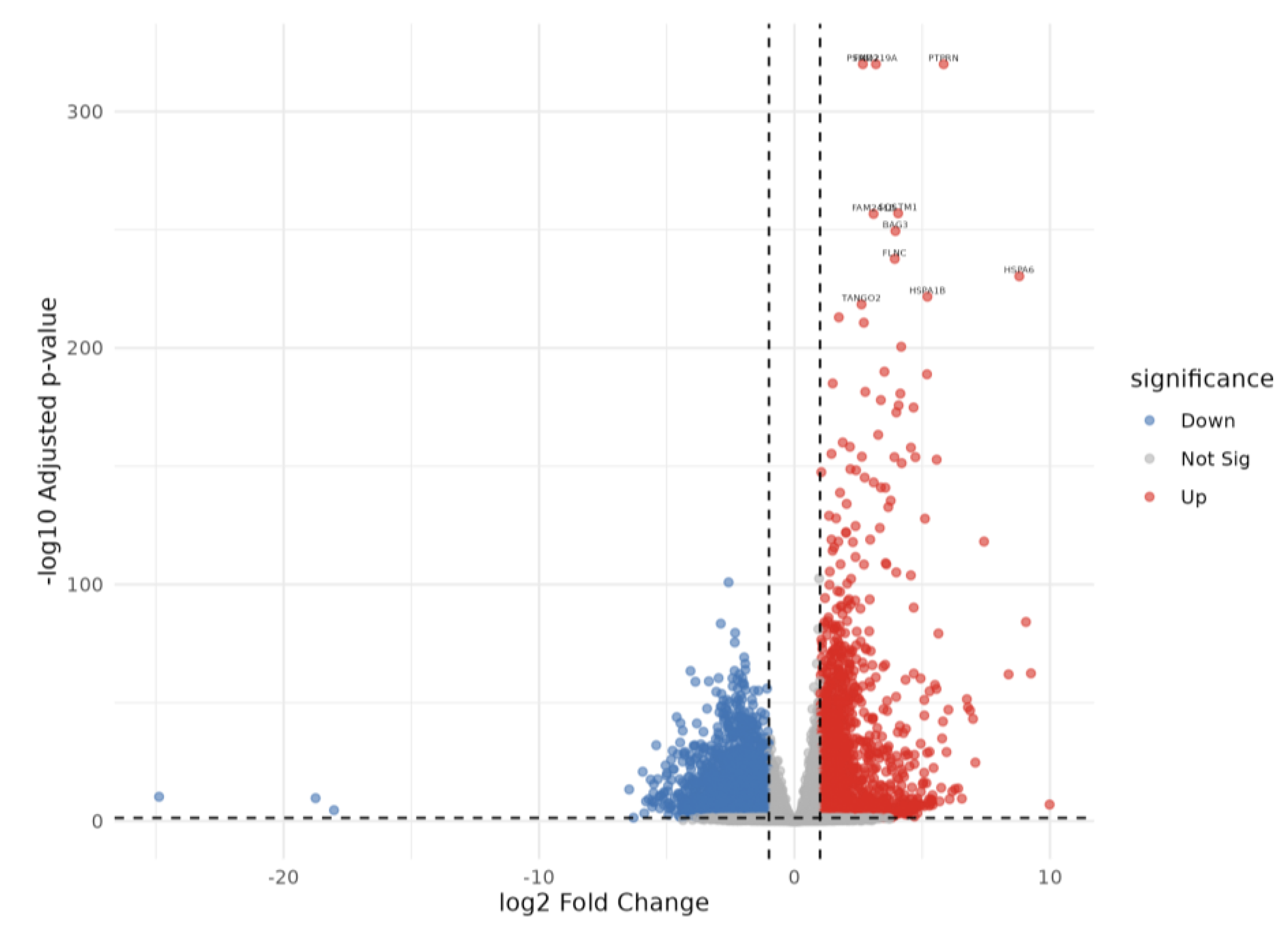

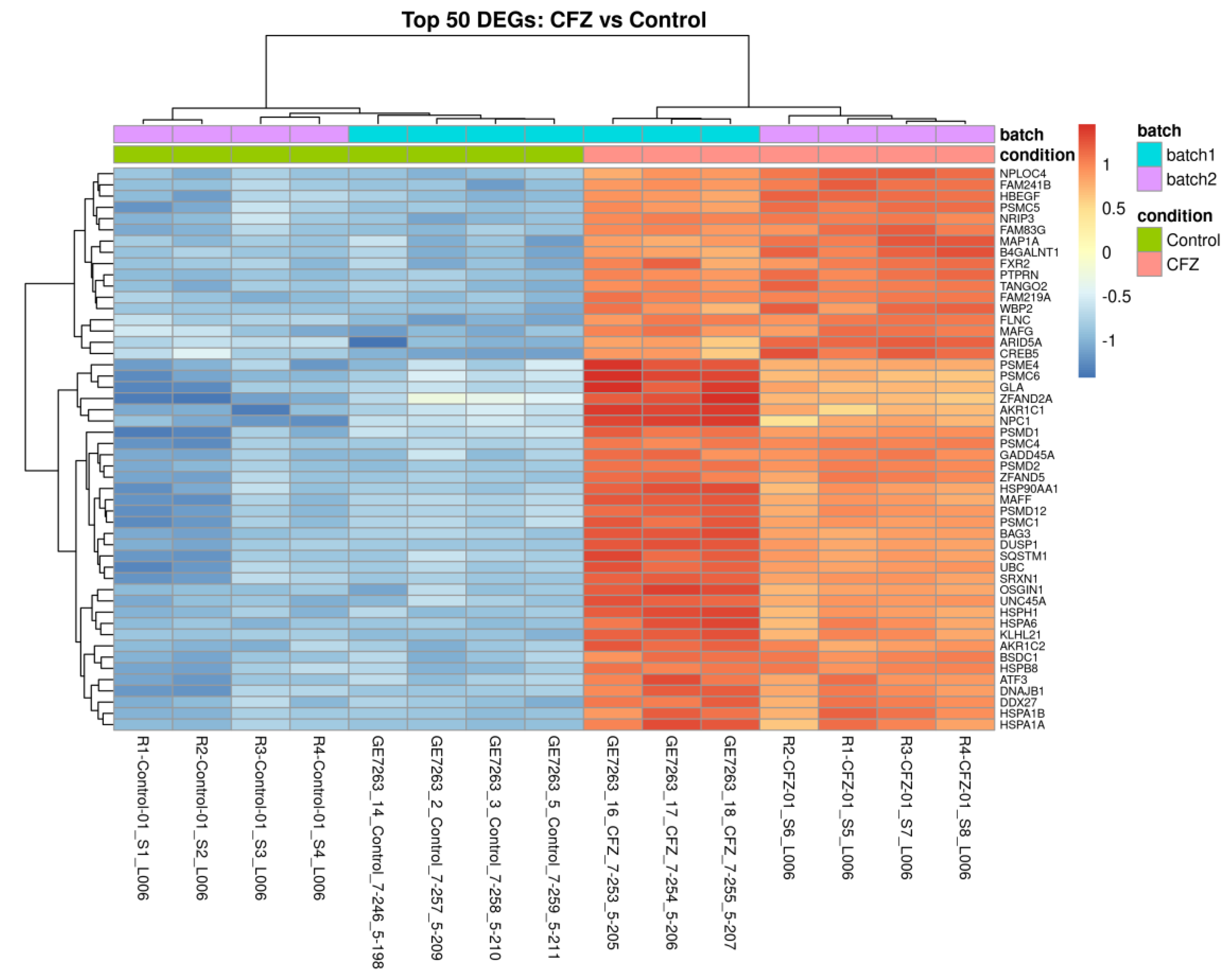

2.3. Differentially Expressed Genes in CFZ vs Control

2.4. Functional Enrichment of CFZ-Induced Gene Expression Changes

2.5. Transcriptomic Clustering Reveals Metabolic Reprogramming with Limited Sarcomeric Recovery in CFZ + Atorvastatin–Treated Cardiomyocytes

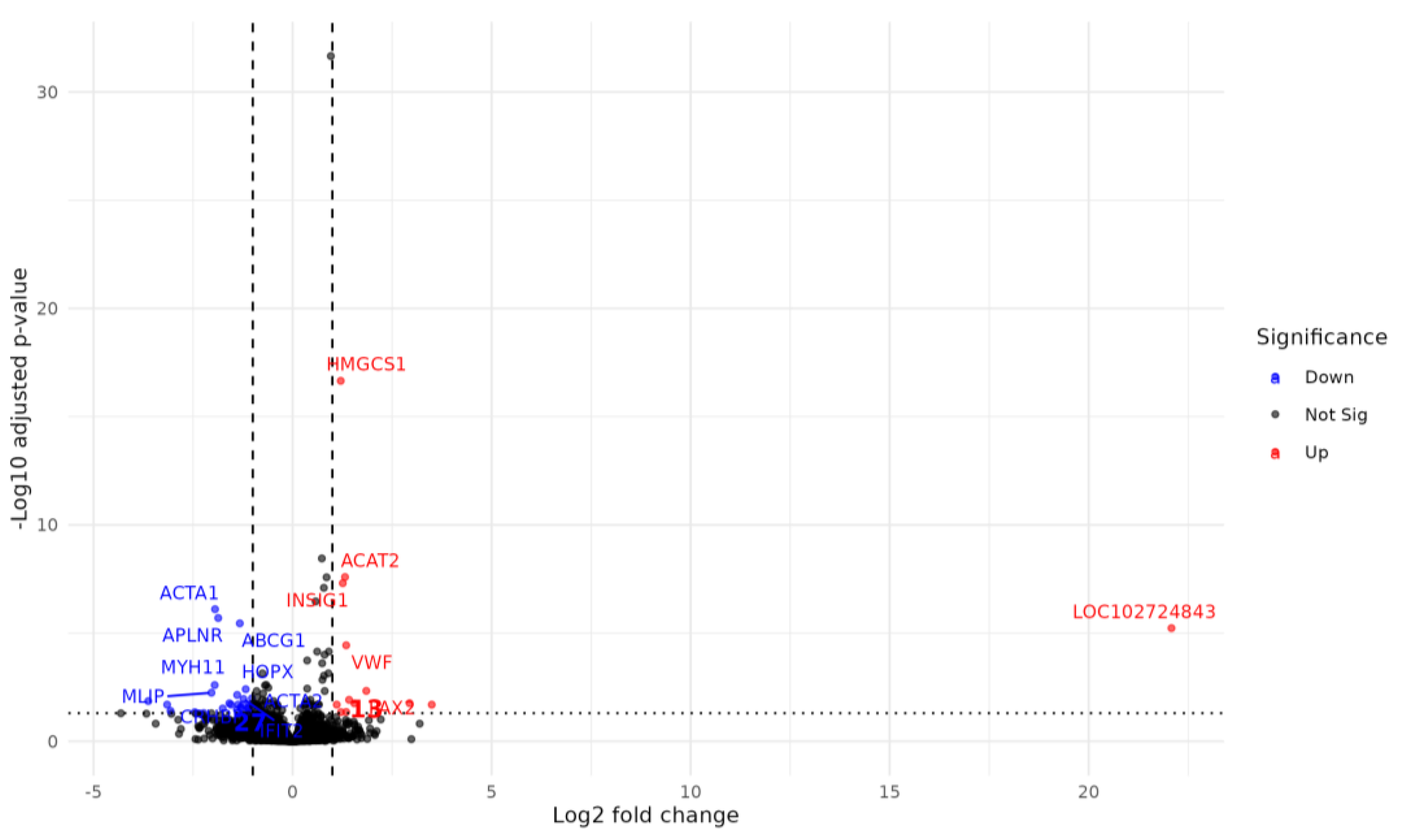

2.6. Atorvastatin Reverses a Subset of CFZ-Induced Transcriptional Alterations

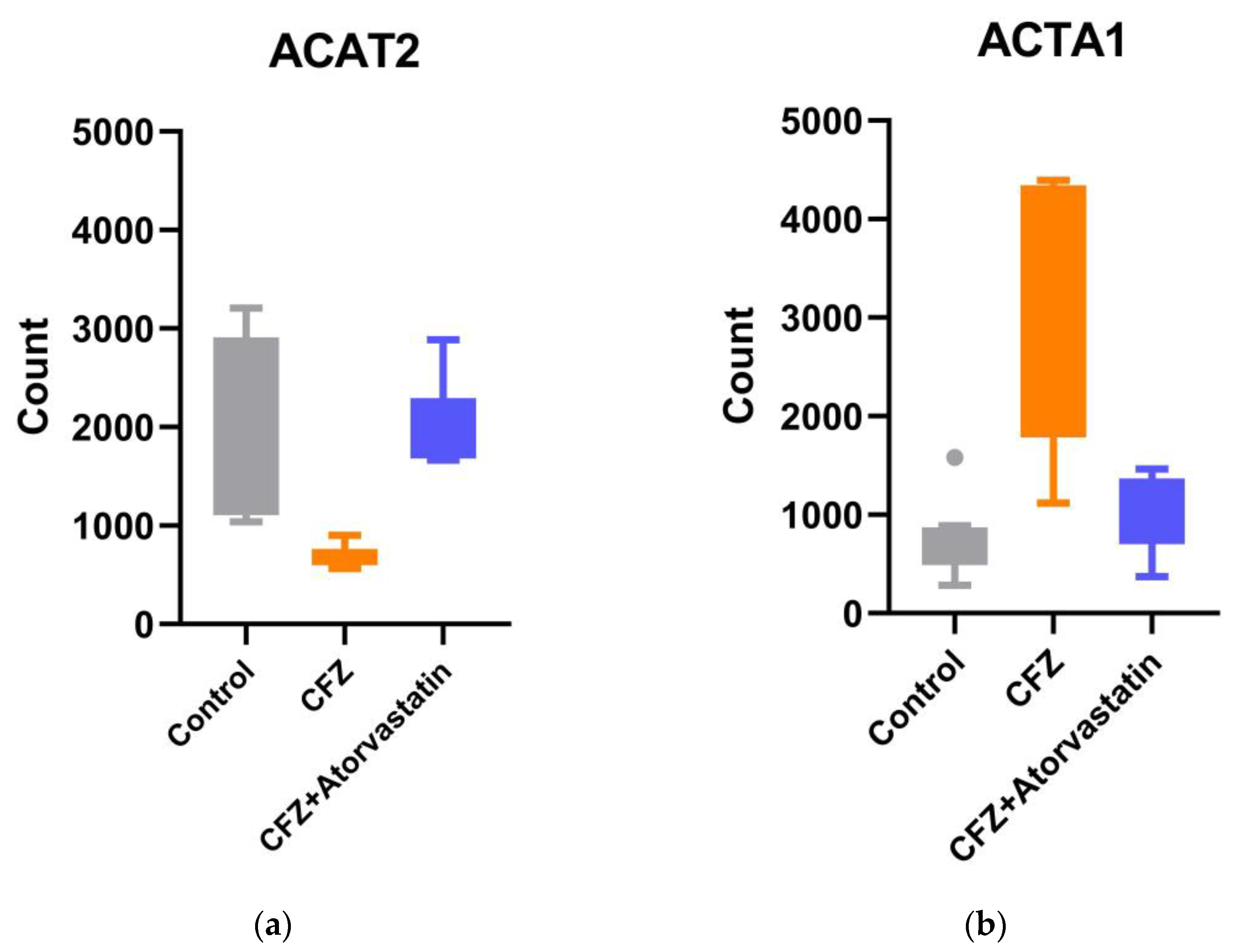

2.7. Validation of RNA-Seq Findings by qPCR

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Human-Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived cardiomyocyte Differentiation

4.2. Drug Preparation and Treatment

4.3. Quantitative Reverse Transcription– Polymerase Chain Reaction

4.4. RNA Library and RNA Sequencing

4.5. RNA-Seq Analysis and Differential Expression Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CFZ | Carfilzomib |

| CVAE hiPSC-CMs |

Cardiovascular adverse event human induced pluripotent stem cell–derived cardiomyocytes |

| ROS MM |

Reactive Oxygen Species multiple myeloma |

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J Clin 2025, 75, 10–45. [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, S.V. Multiple Myeloma: 2024 Update on Diagnosis, Risk-Stratification, and Management. Am J Hematol 2024, 99, 1802–1824. [CrossRef]

- Waxman, A.J.; Clasen, S.; Hwang, W.-T.; Garfall, A.; Vogl, D.T.; Carver, J.; O’Quinn, R.; Cohen, A.D.; Stadtmauer, E.A.; Ky, B.; et al. Carfilzomib-Associated Cardiovascular Adverse Events. JAMA Oncol 2018, 4, e174519. [CrossRef]

- Georgiopoulos, G.; Makris, N.; Laina, A.; Theodorakakou, F.; Briasoulis, A.; Trougakos, I.P.; Dimopoulos, M.-A.; Kastritis, E.; Stamatelopoulos, K. Cardiovascular Toxicity of Proteasome Inhibitors: Underlying Mechanisms and Management Strategies: JACC: CardioOncology State-of-the-Art Review. JACC CardioOncol 2023, 5, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Asselin, B.L.; Devidas, M.; Chen, L.; Franco, V.I.; Pullen, J.; Borowitz, M.J.; Hutchison, R.E.; Ravindranath, Y.; Armenian, S.H.; Camitta, B.M.; et al. Cardioprotection and Safety of Dexrazoxane in Patients Treated for Newly Diagnosed T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia or Advanced-Stage Lymphoblastic Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: A Report of the Children’s Oncology Group Randomized Trial Pediatric Oncology Grou. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2016, 34, 854–862. [CrossRef]

- Koutsoukis, A.; Ntalianis, A.; Repasos, E.; Kastritis, E.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Paraskevaidis, I. Cardio-Oncology: A Focus on Cardiotoxicity. European Cardiology Review 2018, 13, 64–69. [CrossRef]

- Henry, M.L.; Niu, J.; Zhang, N.; Giordano, S.H.; Chavez-MacGregor, M. Cardiotoxicity and Cardiac Monitoring Among Chemotherapy-Treated Breast Cancer Patients. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2018, 11, 1084–1093. [CrossRef]

- Collins, R.; Reith, C.; Emberson, J.; Armitage, J.; Baigent, C.; Blackwell, L.; Blumenthal, R.; Danesh, J.; Smith, G.D.; DeMets, D.; et al. Interpretation of the Evidence for the Efficacy and Safety of Statin Therapy. The Lancet 2016, 388, 2532–2561. [CrossRef]

- Dehnavi, S.; Kiani, A.; Sadeghi, M.; Biregani, A.F.; Banach, M.; Atkin, S.L.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Sahebkar, A. Targeting AMPK by Statins: A Potential Therapeutic Approach. Drugs 2021, 81, 923–933. [CrossRef]

- Acar, Z.; Kale, A.; Turgut, M.; Demircan, S.; Durna, K.; Demir, S.; Meriç, M.; Ağaç, M.T. Efficiency of Atorvastatin in the Protection of Anthracycline-Induced Cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011, 58, 988–989. [CrossRef]

- Neilan, T.G.; Quinaglia, T.; Onoue, T.; Mahmood, S.S.; Drobni, Z.D.; Gilman, H.K.; Smith, A.; Heemelaar, J.C.; Brahmbhatt, P.; Ho, J.S.; et al. Atorvastatin for Anthracycline-Associated Cardiac Dysfunction. JAMA 2023, 330, 528. [CrossRef]

- Hundley, W.G.; D’Agostino, R.; Crotts, T.; Craver, K.; Hackney, M.H.; Jordan, J.H.; Ky, B.; Wagner, L.I.; Herrington, D.M.; Yeboah, J.; et al. Statins and Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction Following Doxorubicin Treatment. NEJM Evidence 2022, 1. [CrossRef]

- Efentakis, P.; Varela, A.; Lamprou, S.; Papanagnou, E.-D.; Chatzistefanou, M.; Christodoulou, A.; Davos, C.H.; Gavriatopoulou, M.; Trougakos, I.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; et al. Implications and Hidden Toxicity of Cardiometabolic Syndrome and Early-Stage Heart Failure in Carfilzomib-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Br J Pharmacol 2024, 181, 2964–2990. [CrossRef]

- Burridge, P.W.; Holmström, A.; Wu, J.C. Chemically Defined Culture and Cardiomyocyte Differentiation of Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. Curr Protoc Hum Genet 2015, 87. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Tanabe, K.; Ohnuki, M.; Narita, M.; Ichisaka, T.; Tomoda, K.; Yamanaka, S. Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Adult Human Fibroblasts by Defined Factors. Cell 2007, 131, 861–872. [CrossRef]

- Burridge, P.W.; Li, Y.F.; Matsa, E.; Wu, H.; Ong, S.-G.; Sharma, A.; Holmström, A.; Chang, A.C.; Coronado, M.J.; Ebert, A.D.; et al. Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes Recapitulate the Predilection of Breast Cancer Patients to Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Nat Med 2016, 22, 547–556. [CrossRef]

- Kitani, T.; Ong, S.-G.; Lam, C.K.; Rhee, J.-W.; Zhang, J.Z.; Oikonomopoulos, A.; Ma, N.; Tian, L.; Lee, J.; Telli, M.L.; et al. Human-Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Model of Trastuzumab-Induced Cardiac Dysfunction in Patients With Breast Cancer. Circulation 2019, 139, 2451–2465. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Burridge, P.W.; McKeithan, W.L.; Serrano, R.; Shukla, P.; Sayed, N.; Churko, J.M.; Kitani, T.; Wu, H.; Holmström, A.; et al. High-Throughput Screening of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Cardiotoxicity with Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Sci Transl Med 2017, 9. [CrossRef]

- Forghani, P.; Rashid, A.; Sun, F.; Liu, R.; Li, D.; Lee, M.R.; Hwang, H.; Maxwell, J.T.; Mandawat, A.; Wu, R.; et al. Carfilzomib Treatment Causes Molecular and Functional Alterations of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes. J Am Heart Assoc 2021, 10, e022247. [CrossRef]

- Pohl, C.; Dikic, I. Cellular Quality Control by the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System and Autophagy. Science 2019, 366, 818–822. [CrossRef]

- Jayaweera, S.P.E.; Wanigasinghe Kanakanamge, S.P.; Rajalingam, D.; Silva, G.N. Carfilzomib: A Promising Proteasome Inhibitor for the Treatment of Relapsed and Refractory Multiple Myeloma. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 740796. [CrossRef]

- Yee, A.J. The Role of Carfilzomib in Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma. Ther Adv Hematol 2021, 12, 20406207211019612. [CrossRef]

- Willis, M.S.; Townley-Tilson, W.H.D.; Kang, E.Y.; Homeister, J.W.; Patterson, C. Sent to Destroy: The Ubiquitin Proteasome System Regulates Cell Signaling and Protein Quality Control in Cardiovascular Development and Disease. Circ Res 2010, 106, 463–478. [CrossRef]

- Haertle, L.; Buenache, N.; Cuesta Hernández, H.N.; Simicek, M.; Snaurova, R.; Rapado, I.; Martinez, N.; López-Muñoz, N.; Sánchez-Pina, J.M.; Munawar, U.; et al. Genetic Alterations in Members of the Proteasome 26S Subunit, AAA-ATPase (PSMC) Gene Family in the Light of Proteasome Inhibitor Resistance in Multiple Myeloma. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Bogomolovas, J.; Wu, T.; Zhang, W.; Liu, C.; Veevers, J.; Stroud, M.J.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, X.; Mu, Y.; et al. Loss-of-Function Mutations in Co-Chaperone BAG3 Destabilize Small HSPs and Cause Cardiomyopathy. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2017, 127, 3189–3200. [CrossRef]

- Knezevic, T.; Myers, V.D.; Gordon, J.; Tilley, D.G.; Sharp, T.E.; Wang, J.; Khalili, K.; Cheung, J.Y.; Feldman, A.M. BAG3: A New Player in the Heart Failure Paradigm. Heart Fail Rev 2015, 20, 423–434. [CrossRef]

- Lakda, S.; Davies, R.H.; Hingorani, A.D.; Paliwal, N. A Systematic Review of GWAS on CMR Imaging Traits: Genetic Insights into Cardiovascular Structure, Function, and Diseases. EBioMedicine 2025, 121, 105992. [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, S.; Nathan, S.; Kar, B.; Gregoric, I.D.; Li, Y.-P. The Role of Extracellular Heat Shock Proteins in Cardiovascular Diseases. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Genga, M.F.; Cuenca, S.; Dal Ferro, M.; Zorio, E.; Salgado-Aranda, R.; Climent, V.; Padrón-Barthe, L.; Duro-Aguado, I.; Jiménez-Jáimez, J.; Hidalgo-Olivares, V.M.; et al. Truncating FLNC Mutations Are Associated With High-Risk Dilated and Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathies. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016, 68, 2440–2451. [CrossRef]

- Franaszczyk, M.; Bilinska, Z.T.; Sobieszczańska-Małek, M.; Michalak, E.; Sleszycka, J.; Sioma, A.; Małek, Ł.A.; Kaczmarska, D.; Walczak, E.; Włodarski, P.; et al. The BAG3 Gene Variants in Polish Patients with Dilated Cardiomyopathy: Four Novel Mutations and a Genotype-Phenotype Correlation. J Transl Med 2014, 12, 192. [CrossRef]

- Norton, N.; Li, D.; Rieder, M.J.; Siegfried, J.D.; Rampersaud, E.; Züchner, S.; Mangos, S.; Gonzalez-Quintana, J.; Wang, L.; McGee, S.; et al. Genome-Wide Studies of Copy Number Variation and Exome Sequencing Identify Rare Variants in BAG3 as a Cause of Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Am J Hum Genet 2011, 88, 273–282. [CrossRef]

- Oberwallner, B.; Brodarac, A.; Anić, P.; Šarić, T.; Wassilew, K.; Neef, K.; Choi, Y.-H.; Stamm, C. Human Cardiac Extracellular Matrix Supports Myocardial Lineage Commitment of Pluripotent Stem Cells. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2015, 47, 416–425; discussion 425. [CrossRef]

- Danhof, S.; Schreder, M.; Rasche, L.; Strifler, S.; Einsele, H.; Knop, S. ‘Real-Life’ Experience of Preapproval Carfilzomib-Based Therapy in Myeloma - Analysis of Cardiac Toxicity and Predisposing Factors. Eur J Haematol 2016, 97, 25–32. [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, S.R.; Williams, A.J. Patterns of Interaction between Anthraquinone Drugs and the Calcium-Release Channel from Cardiac Sarcoplasmic Reticulum. Circ Res 1990, 67, 272–283. [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-F.; Su, W.-C.; Su, C.-C.; Chung, M.-W.; Chang, J.; Li, Y.-Y.; Kao, Y.-J.; Chen, W.-P.; Daniels, M.J. High-Throughput Optical Controlling and Recording Calcium Signal in IPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes for Toxicity Testing and Phenotypic Drug Screening. J Vis Exp 2022. [CrossRef]

- Jannuzzi, A.T.; Arslan, S.; Yilmaz, A.M.; Sari, G.; Beklen, H.; Méndez, L.; Fedorova, M.; Arga, K.Y.; Karademir Yilmaz, B.; Alpertunga, B. Higher Proteotoxic Stress Rather than Mitochondrial Damage Is Involved in Higher Neurotoxicity of Bortezomib Compared to Carfilzomib. Redox Biol 2020, 32, 101502. [CrossRef]

- Jannuzzi, A.T.; Korkmaz, N.S.; Gunaydin Akyildiz, A.; Arslan Eseryel, S.; Karademir Yilmaz, B.; Alpertunga, B. Molecular Cardiotoxic Effects of Proteasome Inhibitors Carfilzomib and Ixazomib and Their Combination with Dexamethasone Involve Mitochondrial Dysregulation. Cardiovasc Toxicol 2023, 23, 121–131. [CrossRef]

- Fiore, C.; Trézéguet, V.; Le Saux, A.; Roux, P.; Schwimmer, C.; Dianoux, A.C.; Noel, F.; Lauquin, G.J.-M.; Brandolin, G.; Vignais, P.V. The Mitochondrial ADP/ATP Carrier: Structural, Physiological and Pathological Aspects. Biochimie 1998, 80, 137–150. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, L.; Jia, K.; Chen, C.; Li, Z.; Zhao, J.; Hu, J.; Zhang, H.; Fan, Q.; Huang, C.; Xie, H.; et al. DYRK1B-STAT3 Drives Cardiac Hypertrophy and Heart Failure by Impairing Mitochondrial Bioenergetics. Circulation 2022, 145, 829–846. [CrossRef]

- Da Dalt, L.; Cabodevilla, A.G.; Goldberg, I.J.; Norata, G.D. Cardiac Lipid Metabolism, Mitochondrial Function, and Heart Failure. Cardiovasc Res 2023, 119, 1905–1914. [CrossRef]

- Hinton, A.; Claypool, S.M.; Neikirk, K.; Senoo, N.; Wanjalla, C.N.; Kirabo, A.; Williams, C.R. Mitochondrial Structure and Function in Human Heart Failure. Circ Res 2024, 135, 372–396. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zheng, A.; Xu, X.; Shi, Z.; Yang, M.; Sun, S.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Xiao, Q.; et al. Nrf3-Mediated Mitochondrial Superoxide Promotes Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis and Impairs Cardiac Functions by Suppressing Pitx2. Circulation 2025, 151, 1024–1046. [CrossRef]

- Deavall, D.G.; Martin, E.A.; Horner, J.M.; Roberts, R. Drug-Induced Oxidative Stress and Toxicity. J Toxicol 2012, 2012, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Angsutararux, P.; Luanpitpong, S.; Issaragrisil, S. Chemotherapy-Induced Cardiotoxicity: Overview of the Roles of Oxidative Stress. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2015, 2015, 13. [CrossRef]

- Chouchani, E.T.; Pell, V.R.; Gaude, E.; Aksentijević, D.; Sundier, S.Y.; Robb, E.L.; Logan, A.; Nadtochiy, S.M.; Ord, E.N.J.; Smith, A.C.; et al. Ischaemic Accumulation of Succinate Controls Reperfusion Injury through Mitochondrial ROS. Nature 2014, 515, 431–435. [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, M. Apoptosis-Related Genes Expressed in Cardiovascular Development and Disease: An EST Approach. Cardiovasc Res 2000, 45, 621–629. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Luo, Y.; Wen, Y.; Wang, D.; Li, J.; Fan, Z. Semaglutide Inhibits Ischemia/Reperfusion-Induced Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis through Activating PKG/PKCε/ERK1/2 Pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2023, 647, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Makin, G.; Hickman, J.A. Apoptosis and Cancer Chemotherapy. Cell Tissue Res 2000, 301, 143–152.

- Yaomura, T.; Tsuboi, N.; Urahama, Y.; Hobo, A.; Sugimoto, K.; Miyoshi, J.; Matsuguchi, T.; Reiji, K.; Matsuo, S.; Yuzawa, Y. Serine/Threonine Kinase, Cot/Tpl2, Regulates Renal Cell Apoptosis in Ischaemia/Reperfusion Injury. Nephrology (Carlton) 2008, 13, 397–404. [CrossRef]

- Mohassel, P.; Mammen, A.L. Anti-HMGCR Myopathy. J Neuromuscul Dis 2018, 5, 11–20. [CrossRef]

- Selva-O’Callaghan, A.; Alvarado-Cardenas, M.; Pinal-Fernández, I.; Trallero-Araguás, E.; Milisenda, J.C.; Martínez, M.Á.; Marín, A.; Labrador-Horrillo, M.; Juárez, C.; Grau-Junyent, J.M. Statin-Induced Myalgia and Myositis: An Update on Pathogenesis and Clinical Recommendations. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2018, 14, 215–224. [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.A.; Sun, L.; Rao, Y.; Ordureau, A.; Lewis, J.S.; An, H. Activity-Based Probes and Chemical Proteomics Uncover the Biological Impact of Targeting HMG-CoA Synthase 1 in the Mevalonate Pathway. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2025, 301, 110660. [CrossRef]

- Theusch, E.; Kim, K.; Stevens, K.; Smith, J.D.; Chen, Y.-D.I.; Rotter, J.I.; Nickerson, D.A.; Medina, M.W. Statin-Induced Expression Change of INSIG1 in Lymphoblastoid Cell Lines Correlates with Plasma Triglyceride Statin Response in a Sex-Specific Manner. Pharmacogenomics J 2017, 17, 222–229. [CrossRef]

- Pramfalk, C.; Angelin, B.; Eriksson, M.; Parini, P. Cholesterol Regulates ACAT2 Gene Expression and Enzyme Activity in Human Hepatoma Cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2007, 364, 402–409. [CrossRef]

- Varet, H.; Brillet-Guéguen, L.; Coppée, J.-Y.; Dillies, M.-A. SARTools: A DESeq2- and EdgeR-Based R Pipeline for Comprehensive Differential Analysis of RNA-Seq Data. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0157022. [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for RNA-Seq Data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 2014, 15, 550. [CrossRef]

- Patro, R.; Duggal, G.; Love, M.I.; Irizarry, R.A.; Kingsford, C. Salmon Provides Fast and Bias-Aware Quantification of Transcript Expression. Nat Methods 2017, 14, 417–419. [CrossRef]

- Soneson, C.; Love, M.I.; Robinson, M.D. Differential Analyses for RNA-Seq: Transcript-Level Estimates Improve Gene-Level Inferences. F1000Res 2015, 4, 1521. [CrossRef]

- Wickham, Hadley. Ggplot2 : Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer, 2016; ISBN 9783319242774.

- Durinck, S.; Spellman, P.T.; Birney, E.; Huber, W. Mapping Identifiers for the Integration of Genomic Datasets with the R/Bioconductor Package BiomaRt. Nat Protoc 2009, 4, 1184–1191. [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.Y.; Tan, C.M.; Kou, Y.; Duan, Q.; Wang, Z.; Meirelles, G.V.; Clark, N.R.; Ma’ayan, A. Enrichr: Interactive and Collaborative HTML5 Gene List Enrichment Analysis Tool. BMC Bioinformatics 2013, 14, 128. [CrossRef]

| Gene Symbol | GENE Name | GENE ID | CFZ vs. Controls | CFZ + atorvastatin vs. CFZ | ||

| Log2 Fold Change | Padj | Log2 Fold Change | Padj | |||

| ACAT2 | Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase 2 | ENSG00000120437 | -1.20 | 7.53E-10 | 1.32 | 2.57E-08 |

| ACTA1 | actin alpha 1, skeletal muscle | ENSG00000143632 | 2.31 | 1.68E-13 | -1.95 | 7.89E-07 |

| PAX2 | paired box 2 | ENSG00000075891 | -4.57 | 5.45E-29 | 1.85 | 0.0047 |

| CRHBP | corticotropin releasing hormone binding protein | ENSG00000145708 | 1.71 | 1.79E-07 | -1.39 | 0.0072 |

| IFIT2 | interferon induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 2 | ENSG00000119922 | 1.20 | 7.15E-05 | -1.23 | 0.011 |

| PLA2G3 | phospholipase A2 group III | ENSG00000100078 | -1.97 | 1.06E-08 | 1.42 | 0.012 |

| VSX2 | visual system homeobox 2 | ENSG00000119614 | -4.69 | 1.23E-10 | 2.94 | 0.017 |

| PCDHA2 | protocadherin alpha 2 | ENSG00000204969 | -1.20 | 0.0036 | 1.55 | 0.018 |

| PTGER2 | prostaglandin E receptor 2 (EP2) | ENSG00000125384 | 1.02 | 0.0148 | -1.59 | 0.018 |

| DERL3 | derlin 3 | ENSG00000099958 | -2.82 | 3.01E-25 | 1.11 | 0.020 |

| NDST4 | N-deacetylase/N-sulfotransferase 4 | ENSG00000138653 | -6.47 | 4.64E-14 | 3.50 | 0.020 |

| TMEM178B | transmembrane protein 178B | ENSG00000261115 | -2.28 | 4.35E-12 | 1.22 | 0.045 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).