1. Introduction

While swimming is widely regarded as a sport with a low risk of traumatic injury—particularly those related to high-impact contact—the aquatic environment presents distinct dermatological challenges. These range from unique aquagenic conditions to common cutaneous infections [

1,

2,

3]. Consequently, microbial colonization in public swimming facilities remains a critical concern in sports medicine, as pool environments often function as reservoirs for pathogenic microorganisms [

4,

5].

A primary concern in this setting is the prevalence of superficial fungal infections (dermatomycoses), caused principally by dermatophytes that colonize keratinized tissues such as the epidermis, hair, and nails without deeper invasion [

6]. Epidemiological data indicate that 10–25% of the global population is affected by these infections [

7,

8]. Such conditions are particularly relevant for athletes training in warm, humid environments that facilitate microbial proliferation [

9,

10]. Evidence suggests a higher prevalence among elite athletes, driven by risk factors including occlusive microenvironments, hyperhidrosis, and skin micro-trauma. Furthermore, locker rooms and shower facilities act as high-risk transmission zones, potentially compromising athletes’ dermatological health and performance [

9,

11].

Tinea pedis, commonly known as athlete’s foot, is a superficial fungal infection primarily caused by dermatophytes of the

Trichophyton genus. While historical data and specific population studies often cite a prevalence of approximately 15% in developed countries, recent global estimates vary significantly, with some reviews suggesting a lower general population prevalence of around 3% [

12,

13]. Interdigital maceration disrupts the skin barrier, facilitating infection. Since dermatophytes persist on abiotic surfaces, such as tiles and textiles, walking barefoot in communal areas constitutes the primary mode of transmission [

1]. In the context of swimming, tinea pedis prevalence has been reported at approximately 8.5%, with males exhibiting higher susceptibility than females [

14].

Pityriasis versicolor is a prevalent, often recurrent superficial infection of the stratum corneum caused by lipophilic yeasts of the genus

Malassezia. Clinically, it presents as hypopigmented or hyperpigmented scaly macules, predominantly affecting the upper trunk in adults [

15,

16]. Key predisposing factors include genetic susceptibility, immunosuppression, and ambient humidity. The condition exhibits distinct seasonality with summer exacerbations, while prevalence varies significantly by climate (over 40% in tropical vs. 0.5–1% in temperate regions) [

17]. However, high environmental exposure markedly increases rates, reaching 15.5% in fishing communities and 2.1% in sailors [

17]. Similarly, athletes show heightened susceptibility, with prevalence of 12.1% in football players and 9.5% in swimmers [

18].

Tinea unguium (onychomycosis), a fungal infection of the nail unit caused predominantly by dermatophytes (70–80%), accounts for approximately 50% of all nail dystrophies [

19]. The global prevalence is estimated at 5.5%, falling within the broad range of previously reported estimates (2%–8%) [

20]. Risk factors include trauma, humidity, and occlusive footwear, making the condition common among swimmers. Beyond aesthetic concerns, tinea unguium can cause pain and discomfort during physical activity [

9]. Notably, studies involving recreational swimmers have reported alarming prevalence rates, reaching up to 26% in males, highlighting the high risk associated with aquatic facilities [

21].

The aim of this study is to assess the prevalence of cutaneous fungal infections among Greek competitive swimmers. Current literature on this specific demographic is scarce, as the majority of prior research has predominantly focused on the general population, recreational swimmers, or athletes participating in other sporting disciplines [

20,

21,

22].

It is hypothesized that the rigors of competitive swimming, alongside specific hygiene habits and the use of communal equipment, heighten the susceptibility to infections. Currently, the paucity of epidemiological evidence regarding this demographic in Greece constitutes a significant gap in the literature. This research aims to bridge that divide by offering region-specific data, which is essential for establishing targeted, evidence-based preventive measures that safeguard training continuity and athletic performance.

2. Materials and Methods

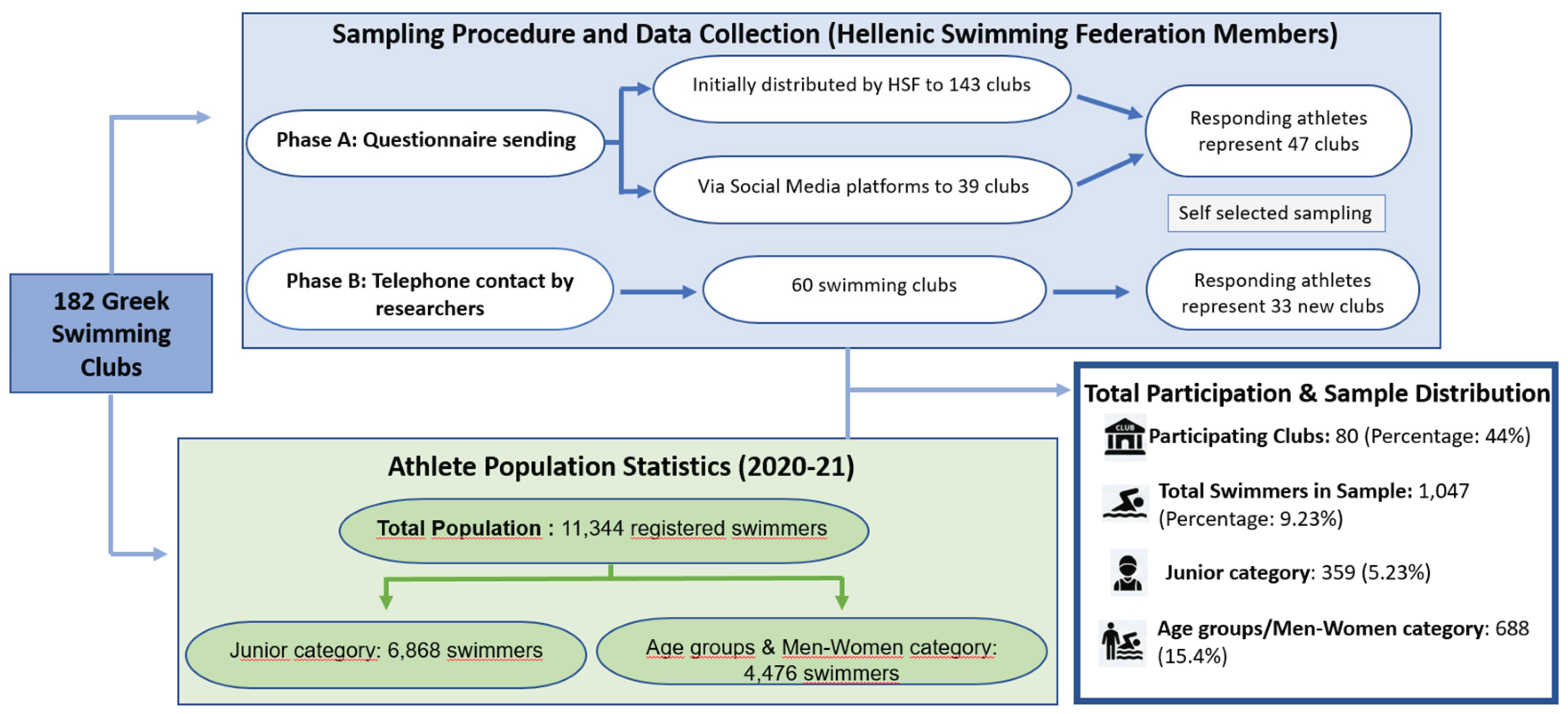

This cross-sectional study investigated the prevalence of cutaneous superficial fungal infections in Greek competitive swimmers. Ethical clearance was granted by the University of West Attica (Ref: 52645, 20 July 2020) and the Hellenic Swimming Federation (Ref: 787, 15 March 2019). Data were collected via an online survey administered between June and December 2021. Due to the logistical difficulties in accessing the total population of competitive swimmers in Greece, a self-selection sampling strategy was deemed the only viable approach.

Recruitment targeted 182 swimming clubs nationwide, resulting in participation from 80 clubs. The data collection process was executed in two distinct phases:

In phase A the Hellenic Swimming Federation emailed the questionnaire to 143 registered clubs. The remaining 39 clubs, for whom contact details were unavailable, were notified via social media. Respondents in this phase self-reported their club affiliation (Supplementary S1).

In phase B in order to increase participation, researchers directly contacted coaches and managers of clubs that did not respond in phase A. Sixty clubs were selected for telephone follow-up; swimmers from 33 of these clubs subsequently completed the survey.

The target population consisted of 11,344 swimmers (or their parents) registered with the Hellenic Swimming Federation during the 2020–21 season. A total of 1,047 competitive swimmers participated (9.23% of the population), a sample size deemed statistically representative [

22]. The cohort included the “Junior category” (ages 9–12), “Age Group categories” (sub-grouped as 13–14, 15–16, and 17–18 years), and the “Men–Women category”. Participation was voluntary and anonymous (

Figure 1).

As part of a broader study on dermatological conditions, the questionnaire underwent rigorous validation [

23]. Content validity was confirmed by a dermatologist and a methodology expert. The questionnaire consisted of closed-ended questions, categorized as either dichotomous or multiple-choice, with the option for multiple answers. Reliability was assessed via a test-retest procedure involving 57 members of one swimming club over a 15-day interval [

24]. Feedback from the initial version regarding question clarity—specifically concerning skin conditions—led to the inclusion of explanatory notes in the final version. Agreement between the two administrations was calculated using Cohen’s Kappa (κ), yielding a value of 0.75. This indicates good reliability, largely attributed to the refinements made based on pilot feedback.

The final questionnaire was administered via Google Forms and comprised two main sections: (1) demographics, training habits, and general skin health, and (2) specific fungal infection details. For the purpose of this specific study, data were extracted regarding demographics, training practices, the seasonality and timing of infections. Supplementary data were collected regarding the training environment (facility type), training load (years of experience and daily duration), and specific pool-related behaviors. The survey also queried family history of fungal infections. To minimize recall bias, participants reporting recurrent infections were instructed to provide details specific to their most recent episode, as this is typically remembered with greater accuracy (Supplementary S1).

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS version 26.0. Categorical variables are reported as frequencies (n) and percentages (%). Bivariate associations between categorical variables were assessed using the Chi-square test, while the Chi-square trend test was utilized to examine relationships involving ordinal variables. Bivariate correlations were conducted to identify potential links between cutaneous fungal infections and demographic or training factors (e.g., gender, facility type, years of training, weekly/daily training load) as well as behavioral habits (e.g., walking barefoot, equipment sharing).

Multivariate logistic regression models were employed to evaluate the impact of specific behavioral and equipment-related risk factors on cutaneous fungal infections. Multivariable models assessed behavioral and clinical factors associated with fungal infections. For tinea pedis, exposures included placing clothes or bathrobes on benches and the use of fins, paddles, kickboards, flip-flops, towels, and swimming suits. For pityriasis versicolor, analyzed variables were placing clothes or bathrobes on benches, kickboard use, and a family history of the infection. For tinea unguium, factors included the use of kickboards, flip-flops, and swimming suits. Associations are reported as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

A total of 1,047 swimmers participated in the study (response rate: 9.23%), comprising 577 females (55.1%) and 470 males (44.9%). The majority trained at outdoor facilities (n = 637, 60.8%), whereas 470 participants (39.2%) trained in indoor facilities. The most represented age group was 9–12 years (n = 359, 34.3%), followed by 13–14 years (n = 231, 22.0%), 15–16 years (n = 194, 18.6%), 17–18 years (n = 112, 10.6%), and ≥18 years (n = 151, 14.4%). Training experience was predominantly 7–9 years (n = 265, 25.3%) and 4–6 years (n = 262, 25.0%). Approximately half of the participants (n = 541) reported a daily training duration of two hours, based on responses from both athletes and their parents.

3.2. General Characteristics of Cutaneous Fungal Infections and Their Association with Training Routines

3.2.1. Tinea Pedis

A total of 167 swimmers (16%) reported tinea pedis, and almost one - third experienced a single episode. Winter saw the most cases (

n = 88), followed by lower rates in spring (

n = 35, 20.5%), summer (

n = 27, 15.9%), and autumn (

n = 20, 11.8%). During treatment, 114 swimmers (68.3%) continued their training, whereas 53 suspended it. Medical advice from a dermatologist was reported by 53.9% (

n = 90), while 44.9% (

n = 75) handled the condition without medical assistance. (

Table 1).

Prompted by existing literature, we investigated the association between tinea pedis and tinea unguium. Our analysis revealed that 17.4% (n=24) of swimmers with tinea pedis presented with concomitant tinea unguium. This association was found to be statistically significant, with a remarkably high probability of co-occurrence (OR 3.061; 95% CI: 1.248–7.507; p<0.001).

Bivariate analysis using tinea pedis showed that:

Females demonstrated a higher prevalence (n = 102, 17.7%) than males (n = 65, 13.8%).

The swimming categories variable demonstrated a statistically significant difference, with adult swimmers showing the highest prevalence of tinea pedis (n = 43, 28.5%) (p<0.001).

Long-term swimmers and those who trained daily exhibited a higher prevalence of tinea pedis compared with the other groups. (

Table 2).

3.2.2. Pityriasis Versicolor

Pityriasis versicolor was reported by 33 swimmers (3.2%). Most cases (

n = 24, 72.7%) occurred once, while four swimmers (12.1%) reported it more than six times. The torso (

n = 14, 53.8%) was the most affected site of the body. More than half of the infections (

n = 24, 58.5%) occurred in summer. Training continued without interruption for 66.7% (

n = 22) of the participants while 33.3% (

n = 11) stop training for less than one week. Dermatological consultation and treatment were sought by 81.8% (

n = 27), and 18.2% (

n = 6) self-treated (

Table 1).

The bivariate analysis revealed that:

No significant gender difference was found.

The highest prevalence appeared in adult swimmers (n = 14, 9.3%) with the remaining categories showing similar percentages (p=0.01).

Significant association was observed with both years of training (

p < 0.001) and daily training duration. Specifically, swimmers training up to 2 hours daily exhibited the highest infection rate (

n = 25, 4.6%,

p < 0.001). (

Table 2).

3.2.3. Tinea Unguium

Tinea Unguium was reported by 35 swimmers (3.3%). In 57.1% (

n = 20) of cases, the condition occurred only once. The infection was reported by nearly half of the participants in the winter season. The majority (

n = 21, 60%) continued training, while 74.3% (

n = 26) consulted a dermatologist and received treatment. A smaller proportion (

n = 9, 25.7%) self-managed the infection (

Table 1).

The bivariate analysis revealed that:

Females demonstrated a higher prevalence (n = 23, 4%) than males (n = 12, 2.6%).

A statistically significant difference was observed among swimming categories, with adult swimmers exhibiting the highest prevalence of tinea unguium (n = 21, 13.9%) (p=0.001); a finding consistent with their long-term engagement in swimming (p<0.001).

The type of swimming facility showed statistical significance, with participants using indoor swimming pools exhibiting a higher rate of tinea unguium (

n = 20, 4.7%) (

p<0.027) (

Table 2).

3.3. Correlation Between Swimmers’ Behavior and Habits and the Development of Cutaneous Fungal Infections

Statistical analysis was performed to investigate the relationship between behavioral factors in the pool area and cutaneous fungal infections. Tinea pedis showed a significant association with the sharing of swimming equipment, specifically fins (

p = 0.05), paddles (

p< 0.001), kickboards (

p=0.043), flip-flops (

p<0.001), towels or bathrobes (

p<0.001), and swimming suits (

p=0.002). Subsequent analysis indicated that sharing flip-flops (OR 2.081, 95% CI: 1.398-3.098,

p<0.001), towel/bathrobe (OR 2.484, 95% CI: 1542-4.004

p<0.001) and puddles (OR 1.447, 95% CI: 1.004-2.087,

p = 0.048) increased the risk of tinea pedis. (

Table 3).

Regarding pityriasis versicolor, 29 swimmers (4%) reported placing personal clothing on pool benches. This practice was associated with a fourfold increase in the risk of infection (OR 4.034, 95% CI: 1.404–11.596, p=0.007). Additionally, sharing kickboards and having a family history of the infection were significant risk factors. Specifically, the odds of developing pityriasis versicolor doubled for those sharing kickboards (OR 2.497, 95% CI: 1.033–6.037, p=0.05) and tripled for individuals with a family history of the condition (OR 3.537, 95% CI: 1.641–7.625, p=0.001).

Behaviors reported by the 33 subjects affected by tinea unguium included walking barefoot on pool decks (

n=25, 3.3%) and placing bathrobes or clothes on benches (

n=28, 4.1%). Statistical analysis further identified that sharing kickboards (

p = 0.049), flip-flops (

p = 0.05), and swimming suits (

p = 0.003) were significant factors associated with the infection. (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

Swimming pools constitute a specific environment where high humidity and temperature favor the growth and transmission of pathogenic fungi [

25,

26]. Consequently, cutaneous fungal infections, are frequently observed among swimmers, often with higher prevalence rates compared to the general population. While the presence of dermatophytes on pool surfaces and decks is well-documented [

27], the specific behavioral factors contributing to transmission among competitive athletes remain under-explored. In this investigation, we aimed to investigate the prevalence of these infections in competitive swimmers and to evaluate the role of hygiene habits and equipment sharing in the spread of the disease.

Our data revealed a 16% prevalence of tinea pedis among competitive swimmers, falling within the 13.2–22.2% range observed in students attending swimming lessons [

1,

28]. Notably, this rate is substantially higher than the estimated 3% prevalence reported in the general global population [

13]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to specifically investigate the prevalence of fungal infections within the competitive swimming population.

We observed a female predilection (17.7%), which stands in contrast to general population data where prevalence is typically higher in males than females [

29]. Similarly, other population-based study has reported male-to-female prevalence ratios ranging from 2:1 to 3:1, attributed to behavioral factors such as occlusive training shoes and higher exposure in communal facilities [

30]. Furthermore, susceptibility appeared to be a function of cumulative exposure; age and systematic training program were positively associated with infection rates, which escalated from 11.6% in adolescents to 28.5% in older groups [

13]. Similarly, the prevalence in our pre-competitive pediatric cohort (6.1%) exceeded the 4% baseline reported for the general pediatric population [

31,

32], though it is worth noting that pediatric rates exhibit significant heterogeneity across studies [

33].

A notable finding was the link between shared equipment and infection [

32,

33]. These findings corroborate reports of fungal contamination in pool water and surfaces [

27], a risk exemplified by the high prevalence of mixed infections (46%) observed in pool employees [

34]. Crucially, our study identified a strong statistical correlation between tinea pedis and the sharing of equipment—specifically fins, paddles, kickboards, and towels [

35]. These items serve as fomite vectors, facilitating transmission through direct contact with plantar and palmar surfaces. Data analysis revealed a significant correlation between the infection and the concomitant presence of tinea unguium. [

21,

36].

The observed 3.2% prevalence of pityriasis versicolor exceeds the 0.8–1.1% range typically reported for general populations in temperate climates [

16,

17], yet remains substantially lower than the 28.5% seen in tropical regions [

17]. Our findings align with the 3.8% prevalence observed in recreational pool users [

37], yet contrast with the 9.5% reported by Aytimur et al. [

38] in a small cohort of swimmers. Thus, the warm and humid environment of swimming facilities appears to be a key factor in disease development, further exacerbated by the environmental conditions in Greece, particularly during warmer seasons.

While Pityriasis versicolor affected both sexes, age emerged as a key determinant, peaking in adolescents and young adults. This predilection is attributed to maximal sebaceous activity, which provides a lipid-rich substrate for yeast proliferation—a susceptibility likely compounded by cumulative exposure to the aquatic environment [

8,

17,

39]. Of particular significance was the robust statistical correlation between truncal lesions and the use of shared swimming aids, specifically kickboards. A similar risk was noted with placing garments on communal benches [

8,

40]. To our knowledge, the specific implication of kickboards has not been previously documented, highlighting a potential novel fomite transmission route. In contrast, the strong association observed with a positive family history aligns with established data suggesting a genetic susceptibility to the infection [

41]. The clinical appearance of the lesions drove health-seeking behavior in the majority of participants. Regarding prevention, while earlier protocols recommended the temporary exclusion of infected swimmers and rigorous facility disinfection [

37], such strict containment measures are rarely implemented in modern practice.

The prevalence of tinea unguium in our study was recorded at 3.3%. This finding closely corresponds to population-based data from Europe and North America, which place the general population rate at approximately 4.3% [

42]. Broader reports, in the same regions, showing rates range from 8.7% to 24% [

43]. This contrasts sharply with the 40% prevalence reported in recreational swimmers [

21], a discrepancy likely attributable to that cohort’s older age profile (>30 years) and non-competitive status [

21]. Studies specifically investigating dermatomycoses in competitive-level swimmers were not identified in the existing literature. Although female swimmers exhibited a slightly higher rate (4%) than males (2.6%), the difference was not statistically significant. This contrasts with literature often reporting a male predominance [

44], though some studies attribute rising rates in women to occlusive footwear and increased athletic participation [

45,

46].

Athlete age appeared to be associated with the manifestation of the disease, as well as with the duration (years and hours) of training. Infection was less common among children, a finding likely attributable to lower exposure to contaminated environments and faster nail growth rates [

47]. Toenails were the predominant site of infection, a finding likely attributable to their slower growth dynamics and direct, repeated contact with fungal reservoirs on pool decks and locker room floors. [

27,

46]. Furthermore, it was observed that sharing swimming suits may contribute to the transmission of the infection. Notably, indoor facilities were associated with a higher prevalence of onychomycosis (4.9%) compared to outdoor facilities (2.4%), likely due to higher environmental humidity. Given the requirement for prolonged therapeutic regimens, the majority of affected participants sought specialist dermatological care; notably, however, this did not result in training discontinuation.

The present study has certain limitations. The cross-sectional design precludes establishing causality, while self-reporting may introduce recall bias. However, selection bias was mitigated by the robust sample size targeting the entire population. Diagnoses relied on clinical assessment rather than microbiological confirmation; nevertheless, data validity is supported by the fact that most participants had received prior specialist diagnosis and antifungal treatment. Additionally, environmental determinants, such as pool water physicochemical quality, were not evaluated. Future research should incorporate these variables for a holistic risk assessment. Finally, as the study focused on competitive swimmers in a warm climate, findings may not be fully generalizable to recreational users or colder geographic regions.

This study elucidates the epidemiology of superficial fungal infections in competitive swimmers, underscoring the critical role of shared fomites in transmission. These findings necessitate revised preventive strategies [

48]. Crucially, as training often continues during infection, educational interventions emphasizing hygiene, protective footwear, and the avoidance of shared equipment are paramount [

21,

48,

49]. Concurrently, rigorous facility disinfection is essential to mitigate environmental fungal loads [

37,

50]. Future research should quantify environmental contamination to establish safer training conditions and clear ‘return-to-play’ guidelines.

5. Conclusions

The data presented herein hold particular relevance for competitive swimmers in Greece. The notable prevalence of these three superficial fungal infections points to a specific risk profile for this group, driven by the aquatic setting and hygiene practices related to communal equipment. Mitigating the impact of these infections necessitates a shift towards rigorous preventive measures, increased awareness, and timely medical intervention to protect the well-being of the swimming population.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org, S1: Questionnaire.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.S. and E.R.; methodology, E.S. and N.T.; software, E.S. and V.-S.G.; validation, N.T. and E.S.; formal analysis, E.S.; investigation, N.T.; resources, E.R.; data curation, E.S. and V.-S.G.; writing—original draft preparation, E.S.; writing—review and editing, E.R.; visualization, V.K.; supervision, E.R.; project administration, V.K.; funding acquisition, V.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

“This research received no external funding”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of West Attica (52645/20 July 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

“Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.”.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”.

References

- Tlougan, B.E.; Podjasek, J.O.; Adams, B.B. Aquatic sports dermatoses: Part 1. In the water: Freshwater dermatoses. Int. J. Dermatol 2010, 49, 874–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rallis, E.; Sfiri, E.; Tertipi, N.; Kefala, V. Molluscum contagiosum among Greek young competitive swimmers. J. Sports. Med. Phys. Fit. 2020, 60, 1307–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sfyri, E.; Tertipi, N.; Kefala, V.; Rallis, E. Prevalence of Plantar Warts, Genital Warts, and Herpetic Infections in Greek Competitive Swimmers. Viruses 2024, 16, 1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basley, R.S.; Basley, G.C.; Palmer, A.H.; Garcia, M.A. Special skin symptoms seen in swimmers. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2000, 43, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sfyri, E.; Kefala, V.; Papageorgiou, E.; Mavridou, A.; Beloukas, A.; Rallis, E. Viral cutaneous infections in swimmers: A preliminary study. Water 2021, 13, 3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruithoff, C.; Gamal, A.; McCormick, T.S.; Ghannoum, M.A. Dermatophyte Infections Worldwide: Increase in Incidence and Associated Antifungal Resistance. Life 2024, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.D.; Denning, D.W.; Gow, N.A.; Levitz, S.M.; Netea, M.G.; White, T. C. Hidden killers: human fungal infections. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4(165), 165rv13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tertipi, N.; Sfyri, E.; Kefala, V.; Rallis, E. Fungal Skin Infections in Beach Volleyball Athletes in Greece. Hygiene 2024, 4, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winokur, C.R.; Dexter, W.W. Fungal infections and parasitic infestations in sports: Expedient identification and treatment. Phys. Sports Μed. 2004, 32, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, T.K.; Dash, S.R.; Sahu, P.; Tiwari, S.P. A systematic review of dermatophytosis: symptoms, and treatments. Asian J. Pharm. Edu. Research 2024, 13(3-s), 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassiri-Jahromi, S.; Khaksar, A.A. Prevalence of cutaneous fungal infections among sports-active individuals. Annals Trop. Med. Pub. Health 2010, 3(2), 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashbee, H.R.; Evans, E.G.V. Fungi and skin. Microbiology today 2000, 27, 132–134. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, A. K.; Barankin, B.; Lam, J.M.; Leong, K.F.; Hon, K.L. Tinea pedis: an updated review. Drugs context 2023, 12, 2023-5-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seebacher, C.; Bouchara, J.P.; Mignon, B. Updates on the epidemiology of dermatophyte infections. Mycopath 2008, 166, 335–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudiello, F.; Tommasino, N.; D’Ascenzo, S.; Scalvenzi, M.; Foggia, L. Atypical forms of pityriasis versicolor. JAAD Case Reports 2025, 64, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łabędź, N.; Navarrete-Dechent, C.; Kubisiak-Rzepczyk, H.; Bowszyc-Dmochowska, M.; Pogorzelska-Antkowiak, A.; Pietkiewicz, P. Pityriasis Versicolor—A Narrative Review on the Diagnosis and Management. Life 2023, 13, 2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo-Erchiga, V.; Delgado Florencio, V. Malassezia yeasts and pityriasis versicolor. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2006, 19, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aytimur, D.; Ertam, I.; Ergun, M. Characteristics of sports – related dermatoses for different types of sports: A cross – sectional study. J. Dermatol. 2005, 32, 620–625. [Google Scholar]

- Maraki, S.; Mavromanolaki, V.E. Epidemiology of onychomycosis in Crete, Greece: a 12-year study. Mycoses 2016, 59(12), 798–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.K.; Versteeg, S.G.; Shear, N.H. Onychomycosis in the 21st Century: An Update on Diagnosis, Epidemiology, and Treatment. J. Cut. Med. Surg. 2017, 21(6), 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gudnadottir, G.; Hilmarsdottir, I.; Sigurgeirsson, B. Onychomicosis in Icelandic swimmers. Acta Derm. Venereol. 1999, 79(5), 376–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daggett, C.; Brodell, R.T.; Daniel, C.R.; Jackson, J. Onychomycosis in Athletes. Am. J. Clin. Derm. 2019, 20(5), 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charan, J.; Biswas, T. How to calculate sample size for different study designs in medical research? Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2013, 35, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopcakova, J.; Danculincova Veselska, Z.; Kalman, M.; Filakovska Bobakova, D.; Sigmundova, D.; Madarasova Geckova, A.; Klein, D.; van Dijk, J.P.; Reijneveld, S.A. Test-Retest Reliability of a Questionnaire on Motives for Physical Activity Among Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub. Health 2020, 17, 7551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, N.; Dabiri, S.; Getso, M. I.; Damani, E.; Modrek, M. J.; Parandin, F.; Raissi, V.; Yarahmadi, M.; Shamsaei, S.; Soleimani, A.; Amiri, S.; Arghavan, B.; Raiesi, O. Fungal contamination of indoor public swimming pools and their dominant physical and chemical properties. J. Prev. Med. Hygiene 2022, 62(4), E879–E884. [Google Scholar]

- Sarmadian, H.; Hazbavi, Y.; Didehdar, M.; Ghannadzadeh, M. J.; Hajihossein, R.; Khosravi, M.; Ghasemikhah, R. Fungal and parasitic contamination of indoor public swimming pools in Arak, Iran. J. Par. Dis. 2020, 44(4), 786–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekowati, Y.; Ferrero, G.; Kennedy, M.D.; de Roda Husman, A-M.; Schets, F.M. Potential transmission pathways of clinically relevant fungi in indoor swimming pool facilities. Int. J. Hyg. Envir. Health 2018, 221(8), 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, B.B. Sport Dermatology; Springer: NY, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Perea, S; Ramos, MJ; Garau, M; et al. Prevalence and risk factors of tinea unguium and tinea pedis in the general population in Spain. J Clin Microbiol. 2000, 38(9), 3226–3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havlickova, H.; Czaika, A.V.; Friedrich, M. Epidemiological trends in skin mycoses worldwide. J. Mycoses 2008, 4, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triviño-Duran, L.; Torres-Rodriguez, J.M.; Martinez-Roig, A.; Cortina, C.; Belver, V.; Perez-Gonzalez, M.; Jansa, J.M. Prevalence of tinea capitis and tinea pedis in Barcelona schoolchildren. Ped. Infect. Dis. J. 2005, 24(2), 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerg Stenderup, J.E.; Goandal, N.F.; Lindhardt Saunte, D.M. Systematic Review of the Prevalence of Tinea Pedis in Children. Ped. Derm. 2025, 42(3), 539–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rychlik, K.; Sternicka, J.; Zabłotna, M.; Nowicki, R.J.; Bieniaszewski, L.; Purzycka-Bohdan, D. Superficial Fungal Infections in the Pediatric Dermatological Population of Northern Poland. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemer, A.; Grunwald, M.H.; Davidovici, B.; Nathansohn, N.; Amichai, B. A novel two-step kit for topical treatment of tineapedis — an open study. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2010, 24(9), 1099–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łazicka, P.; Jakubowska, E.; Tarnowska, J. Approaches to the diagnosis of Cutaneous Diseases Among Swimmers: Causes, Symptoms, Prevention, Treatment. Qual. Sport 2025, 37, 56586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.; Athanasoula, E.; Lee, W.; Mahmudova, N.; Vlahovic, T.C. Environmental and Genetic Factors on the Development of Onychomycosis. J. Fungi 2015, 1, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talari, S.A.; Vali, G.R.; Vakily, Z. The prevalence of pityriasis versicolor and its relationship with serum levels of cholesterol and triglyceride among swimmers in Kashan and Aran-Bidgol swimming pools in 2001. Flor. Fauna (Jhansi) 2003, 9(2), 99–101. [Google Scholar]

- Aytimur, D.; Ertam, I.; Ergun, M. Characteristics of sports – related dermatoses for different types of sports: A cross – sectional study. J Dermatol 2005, 32, 620–625. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, N.; Sharma, M.; Saxena, V.N. Clinico-mycological profile of dermatophytosis in Jaipur, Rajasthan. Ind. J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2008, 74(3), 274–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karray, M.; McKinney, W. Tinea Versicolor, Stat Pearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2021, [Internet], Bookshelf ID: NBK482500.

- He, S.M.; Du, W.D.; Yang, S.; Zhou, S.M.; Li, W.; Wang, J.; Xiao, F.L.; Xu, S.J.; Zhang, X.J. The genetic epidemiology of tinea versicolor in China. Mycopath. 2008, 165(2), 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigurgeirsson, B.; Baran, R. The prevalence of onychomycosis in the global population: a literature study. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2014, 28(11), 1480–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.K.; Stec, N.; Summerbell, R.C.; Shear, N.H.; Piguet, V.; Tosti, A.; Piraccini, B.M. Onychomycosis: a review. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, 1972–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkila, H.; Stubb, S. The prevalence of onychomycosis in Finland. Br. J. Dermatol 1995, 133, 699–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sais, G.; Jucgla, A.; Peyri, J. Prevalence of dermatophyte onychomycosis in Spain a cross-sectional study. Br. J. Dermatol. 1995, 132, 758–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigopoulos, D.; Gregoriou, S. Onychomycosis. In Katsambas A.D., editor. European handbook of dermatological treatments. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, 2015, 681-690.

- Kaur, R.; Kashyap, B.; Bhalla, P. Onychomycosis-epidemiology, diagnosis and management. Ind. J. Med. Microb. 2008, 26(2), 108–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Guidelines for Safe Recreational-Water Environments Final Draft for Consultation: Volume 2: Swimming Pools, Spas and Similar Recreational-Water Environments; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006, 48–49.

- Pasquarella, C.; Veronesi, L.; Napoli, C.; Castaldi, S.; Pasquarella, M.L.; Saccani, E.; Colucci, M.E.; Auxilia, F.; Gallè, F.; Di Onofrio, V.; et al. What About Behaviors in Swimming Pools? Results of an Italian Multicenter Study. Microchem. J. 2014, 112, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E-nomothesia.gr. Hygiene Provision C1/443/1973-Law B-87/24-1-1973. Available online: https://www.e-nomothesia.gr/ygeionomikos-kanonismos-diatakseis/kolumbetikes-dexamenes/yd-g1-443-1973.html (accessed on 22 October 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).