Submitted:

22 December 2025

Posted:

23 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Literature Review

Youth Health and Structural Determinants in Africa

Poverty as the Fundamental Determinant of Health Inequality

Age-Differentiated Health Vulnerability

Theoretical Foundations for Age as a Moderator

Empirical Evidence on Age-Differentiated Poverty Effects

Rationale for the Current Study

Materials and Methods

Data Source and Study Design

Sampling and Data Collection

Ethical Considerations

Measures

Dependent Variables

- Gone without healthcare at least once – a binary variable (1 = yes, 0 = no) indicating whether respondents reported going without needed healthcare services at least once in the previous 12 months. Nearly 60% yes and 40% no responses were recorded for which reason a complementary log-log regression was selected.

- Paid a bribe to access healthcare – a binary variable (1 = yes, 0 = no) capturing whether respondents reported paying a bribe or gift to obtain healthcare during the same period. Almost 11% yes and 89% no responses were obtained, and negative log-log regression model was adopted.

- Difficulty in accessing healthcare – a binary variable (1 = yes, 0 = no) measuring respondents’ self-reported difficulty in obtaining medical care when needed. About 30% yes and 70% no responses were obtained, and negative log-log regression model was executed.

Independent Variables

- Poverty status was operationalised using Afrobarometer’s Lived Poverty Index (LPI), which captures the frequency with which individuals go without basic necessities such as food, clean water, or medical care. Higher scores indicate greater material deprivation.

- Age was measured as a continuous variable (in years) and re-categorised into four mutually-exclusive groups for regression models. For moderation analysis, interaction terms between age groups and poverty were constructed.

- Control variables included sex, educational attainment, employment status, urban-rural residence, and country fixed effects to account for structural and contextual variation across national settings.

Statistical Analysis

- Bivariate complementary log-log (cloglog) regression model predicting the likelihood of having gone without healthcare at least once. The cloglog link was chosen due to the asymmetric distribution of the outcome and its appropriateness for modeling binary rare-event data.

- Bivariate and multivariate negative log-log regression models predicting the probability of paying a bribe to access healthcare. The bivariate models examined the unadjusted relationships between poverty, age, and the dependent variable, while multivariate models adjusted for all control variables.

- Bivariate and multivariate negative log-log regression models predicting difficulty in accessing healthcare, following the same modeling strategy as above.

Results

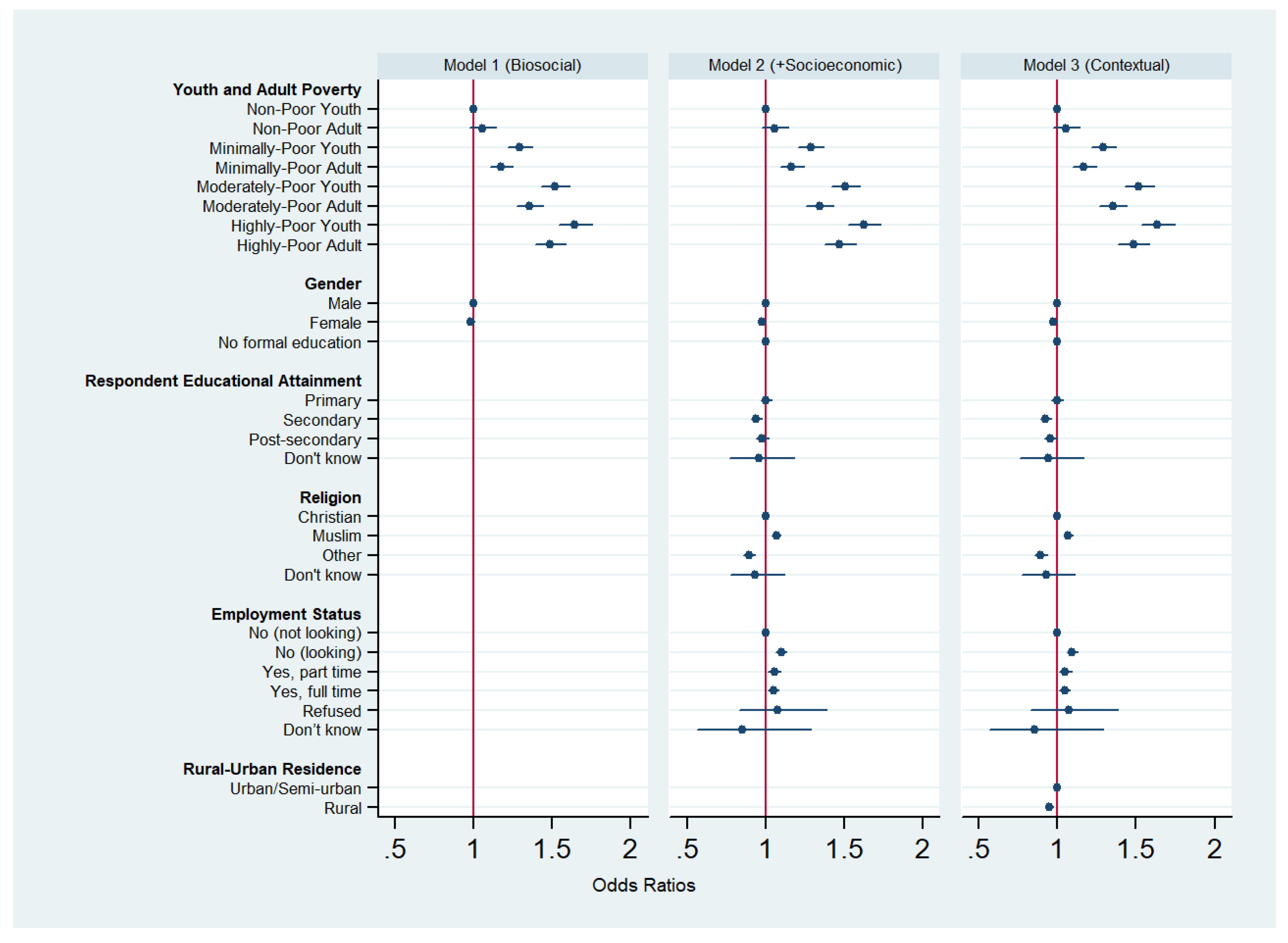

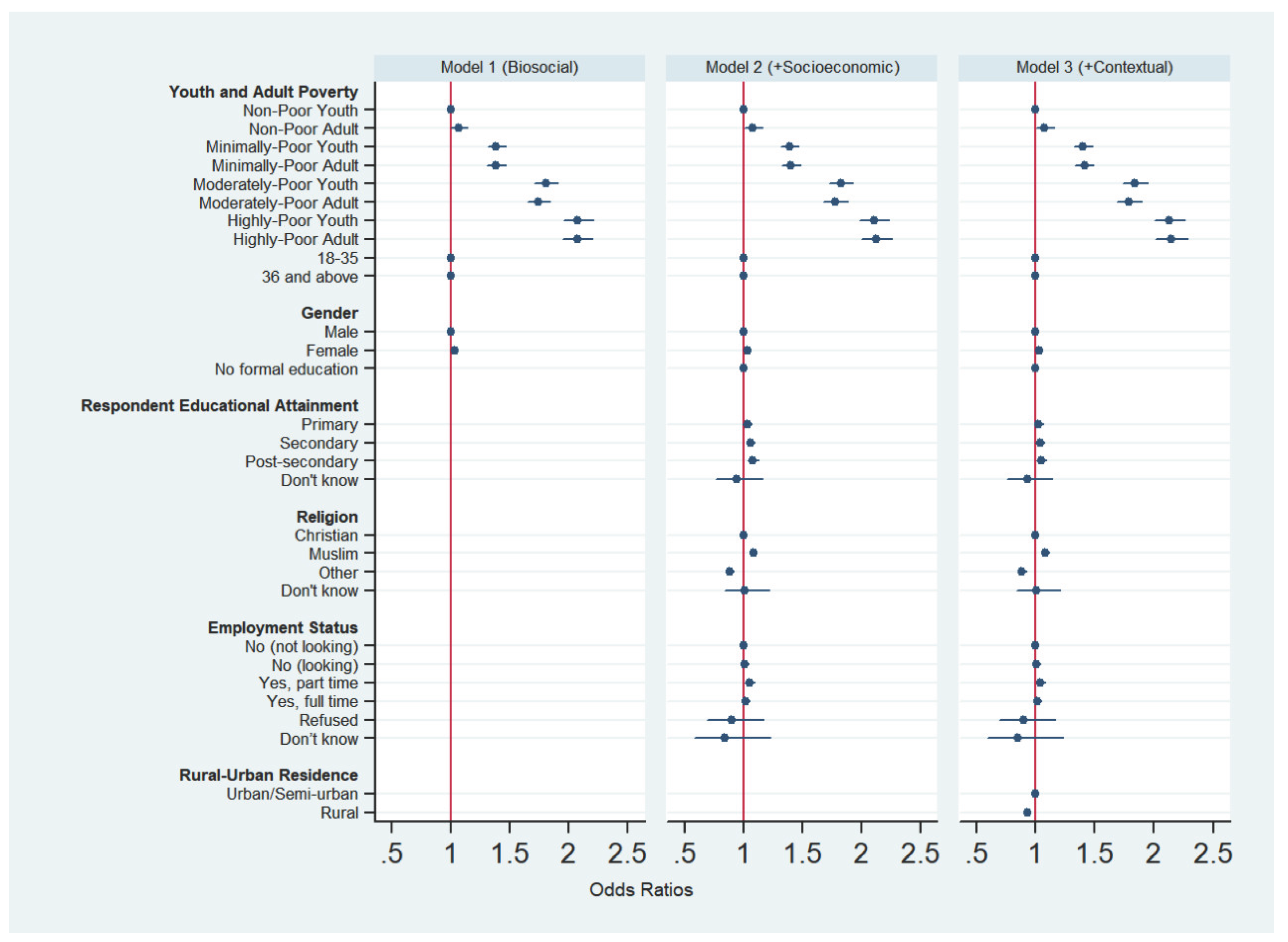

Poverty as a Core Determinant of Healthcare Inequality

Age, Youth Vulnerability, and the Moderation of Poverty

Mediation and Suppression Effects: What the Multivariate Transition Reveals?

Healthcare Integrity vs. Accessibility: Distinct but Connected Outcomes

Policy and Research Implications

Limitations

Conclusion

Funding

References

- Alkire, S.; Santos, M. E. Measuring Acute Poverty in the Developing World: Robustness and Scope of the Multidimensional Poverty Index. World Development 2014, 59, 251–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asongu, S. A.; Diop, S. Bribing to Escape Poverty in Africa. International Journal of Public Administration 2025, 48(1), 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, D. J. The origins of the developmental origins theory. J Intern Med 2007, 261(5), 412–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, M. M.; Walker, S. P.; Fernald, L. C. H.; Andersen, C. T.; DiGirolamo, A. M.; Lu, C.; Grantham-McGregor, S. Early childhood development coming of age: science through the life course. Lancet 2017, 389(10064), 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braveman, P.; Gottlieb, L. The social determinants of health: it’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep 2014, 129 Suppl 2(Suppl 2), 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukari, C.; Seth, S.; Yalonetkzy, G. Corruption can cause healthcare deprivation: Evidence from 29 sub-Saharan African countries. World Development 2024, 180, 106630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, A.; Lubotsky, D.; Paxson, C. Economic Status and Health in Childhood: The Origins of the Gradient. Am Econ Rev 2002, 92(5), 1308–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.; Martin, A. D.; Matthews, K. A. Understanding Health Disparities: The Role of Race and Socioeconomic Status in Children’s Health. American Journal of Public Health 2006, 96(4), 702–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicchetti, D.; Rogosch, F. A. A developmental psychopathology perspective on adolescence. J Consult Clin Psychol 2002, 70(1), 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, J.; Stabile, M. Socioeconomic Status and Child Health: Why Is the Relationship Stronger for Older Children? Am Econ Rev 2003, 93(5), 1813–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, G. H.; Johnson, M. K.; Crosnoe, R. The Emergence and Development of Life Course Theory. In Handbook of the Life Course; Mortimer, J. T., Shanahan, M. J., Eds.; Springer US, 2003; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, K. F.; Shippee, T. P.; Schafer, M. H. Cumulative inequality theory for research on aging and the life course. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fotso, J.-C. Urban–rural differentials in child malnutrition: Trends and socioeconomic correlates in sub-Saharan Africa. Health & Place 2007, 13(1), 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Prina, A. M.; Ma, Y.; Aceituno, D.; Mayston, R. Inequalities in Older age and Primary Health Care Utilization in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. Int J Health Serv 2022, 52(1), 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gluckman, P. D.; Hanson, M. A.; Beedle, A. S. Early life events and their consequences for later disease: a life history and evolutionary perspective. Am J Hum Biol 2007, 19(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodburn, E. A.; Ross, D. Young people’s health in developing countries: A neglected problem and opportunity. Health policy and planning 2000, 15, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J. Examining Determinants of Corruption at the Individual Level in South Asia. Economies 2023, 11(7). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckman, J. J. Skill formation and the economics of investing in disadvantaged children. Science 2006, 312(5782), 1900–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, L. D.; Galobardes, B.; Matijasevich, A.; Gordon, D.; Johnston, D.; Onwujekwe, O.; Hargreaves, J. R. Measuring socio-economic position for epidemiological studies in low- and middle-income countries: a methods of measurement in epidemiology paper. Int J Epidemiol 2012, 41(3), 871–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, A.; Vogt, V.; Quentin, W. Effect of corruption on perceived difficulties in healthcare access in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS One 2019, 14(8), e0220583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICF International. Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) Program: Key Indicators Report; M. I. Calverton, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Justesen, M. K.; Bjørnskov, C. Exploiting the Poor: Bureaucratic Corruption and Poverty in Africa. World Development 2014, 58, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabia, E.; Goodman, C.; Balabanova, D.; Muraya, K.; Molyneux, S.; Barasa, E. The hidden financial burden of healthcare: a systematic literature review of informal payments in Sub-Saharan Africa. Wellcome Open Research 2021, 6, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuh, D.; Ben-Shlomo, Y.; Lynch, J.; Hallqvist, J.; Power, C. Life course epidemiology. J Epidemiol Community Health 2003, 57(10), 778–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Link, B. G.; Phelan, J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav 1995, Spec No, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackenbach, J. P. The persistence of health inequalities in modern welfare states: the explanation of a paradox. Soc Sci Med 2012, 75(4), 761–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marmot, M. The Health Gap: The Challenge of an Unequal World: the argument. Int J Epidemiol 2017, 46(4), 1312–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLoyd, V. C. Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. Am Psychol 1998, 53(2), 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naher, N.; Hoque, R.; Hassan, M. S.; Balabanova, D.; Adams, A. M.; Ahmed, S. M. The influence of corruption and governance in the delivery of frontline health care services in the public sector: a scoping review of current and future prospects in low and middle-income countries of south and south-east Asia. BMC public health 2020, 20(1), 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwokolo, C.; Onwujekwe, O.; McKee, M.; Ojiakor, I.; Angell, B.; Balabanova, D. Household health-seeking behaviour and response to Informal payment: does economic status matter? Health Economics Review 2025, 15(1), 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, G. I.; Sibomana, O. Understanding Health Inequality, Disparity and Inequity in Africa: A Rapid Review of Concepts, Root Causes, and Strategic Solutions. Public Health Chall 2025, 4(1), e70040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.; Flisher, A. J.; Hetrick, S.; McGorry, P. Mental health of young people: a global public-health challenge. Lancet 2007, 369(9569), 1302–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettifor, A. E.; van der Straten, A.; Dunbar, M. S.; Shiboski, S. C.; Padian, N. S. Early age of first sex: a risk factor for HIV infection among women in Zimbabwe. Aids 2004, 18(10), 1435–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, J. C.; Link, B. G.; Tehranifar, P. Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: theory, evidence, and policy implications. J Health Soc Behav 2010, 51 Suppl, S28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, L. M.; Daelmans, B.; Lombardi, J.; Heymann, J.; Boo, F. L.; Behrman, J. R.; Darmstadt, G. L. Investing in the foundation of sustainable development: pathways to scale up for early childhood development. Lancet 2017, 389(10064), 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rock, A.; Barrington, C.; Abdoulayi, S.; Tsoka, M.; Mvula, P.; Handa, S. Social networks, social participation, and health among youth living in extreme poverty in rural Malawi. Social science & medicine 2016, 170, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, S. M.; Afifi, R. A.; Bearinger, L. H.; Blakemore, S. J.; Dick, B.; Ezeh, A. C.; Patton, G. C. Adolescence: a foundation for future health. Lancet 2012, 379(9826), 1630–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shonkoff, J. P.; Boyce, W. T.; McEwen, B. S. Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities: building a new framework for health promotion and disease prevention. Jama 2009, 301(21), 2252–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shonkoff, J. P.; Garner, A. S. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics 2012, 129(1), e232-246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J. P.; Smith, G. C. Long-term economic costs of psychological problems during childhood. Soc Sci Med 2010, 71(1), 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommersguter-Reichmann, M.; Reichmann, G. Untangling the corruption maze: exploring the complexity of corruption in the health sector. Health Econ Rev 2024, 14(1), 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, C.; Kassa, S. The ambivalence of social networks and their role in spurring and potential for curbing petty corruption: Comparative insights from East Africa. In Basel Institute on Governance; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children’s Fund. The State of the World’s Children 2021: On My Mind—Promoting, protecting and caring for children’s mental health; Unicef: New York, Issue, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Poel, E.; O’Donnell, O.; Van Doorslaer, E. Are urban children really healthier? Evidence from 47 developing countries. Soc Sci Med 2007, 65(10), 1986–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victora, C. G.; Adair, L.; Fall, C.; Hallal, P. C.; Martorell, R.; Richter, L.; Sachdev, H. S. Maternal and child undernutrition: consequences for adult health and human capital. The Lancet 2008, 371(9609), 340–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagmiller, R. L., Jr.; Lennon, M. C.; Kuang, L.; Aber, J. L.; Alberti, P. M. The Dynamics of Economic Disadvantage and Children’s Life Chances. American Sociological Review 2006, 71(5), 847–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO, G. WHO methods and data sources for life tables 1990-2016. Global health estimates technical paper; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health 2018; World Health Organization, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. World health statistics 2020 2020.

| Variable | Odds Ratio | SE | P-Value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lived Poverty (Ref: No Lived Poverty) | |||||

| Low Lived Poverty | 1.209 | 0.027 | 0.000 | 1.157 | 1.264 |

| Moderate Lived Poverty | 1.408 | 0.031 | 0.000 | 1.348 | 1.471 |

| High Lived Poverty | 1.530 | 0.036 | 0.000 | 1.461 | 1.602 |

| Youth & Adult Poverty (Ref: Non-poor youth) | |||||

| Non-Poor Adult | 1.056 | 0.042 | 0.171 | 0.977 | 1.142 |

| Minimally-Poor Youth | 1.294 | 0.040 | 0.000 | 1.217 | 1.375 |

| Minimally-Poor Adult | 1.175 | 0.038 | 0.000 | 1.104 | 1.252 |

| Moderately-Poor Youth | 1.518 | 0.047 | 0.000 | 1.428 | 1.613 |

| Moderately-Poor Adult | 1.359 | 0.043 | 0.000 | 1.277 | 1.447 |

| Highly-Poor Youth | 1.644 | 0.054 | 0.000 | 1.542 | 1.753 |

| Highly-Poor Adult | 1.490 | 0.050 | 0.000 | 1.396 | 1.590 |

| Life Stage (Youth Ref: 35 years or younger) | |||||

| Adult (36 years and older) | 0.916 | 0.011 | 0.000 | 0.894 | 0.937 |

| Gender/Sex (Ref: Male) | |||||

| Female | 0.989 | 0.012 | 0.365 | 0.967 | 1.012 |

| Educational Attainment (Ref: No formal education) | |||||

| Primary education | 0.976 | 0.017 | 0.164 | 0.944 | 1.010 |

| Secondary education | 0.919 | 0.015 | 0.000 | 0.890 | 0.950 |

| Post-secondary education | 0.929 | 0.018 | 0.000 | 0.894 | 0.965 |

| Religion (Ref: Christian) | |||||

| Muslim | 1.065 | 0.014 | 0.000 | 1.039 | 1.092 |

| Others | 0.888 | 0.019 | 0.000 | 0.851 | 0.927 |

| Employment Status (Ref: No (not looking)) | |||||

| No (looking) | 1.104 | 0.016 | 0.000 | 1.073 | 1.137 |

| Yes, part time | 1.036 | 0.020 | 0.069 | 0.997 | 1.075 |

| Yes, full time | 0.991 | 0.016 | 0.566 | 0.960 | 1.022 |

| Urbanicity (Ref: Urban residence) | |||||

| Rural residence | 0.996 | 0.012 | 0.730 | 0.973 | 1.019 |

| Variable | Odds Ratio | SE | P-Value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lived Poverty (Ref: No Lived Poverty) | |||||

| Low Lived Poverty | 1.341 | 0.027 | 0.000 | 1.289 | 1.395 |

| Moderate Lived Poverty | 1.720 | 0.035 | 0.000 | 1.653 | 1.790 |

| High Lived Poverty | 2.010 | 0.044 | 0.000 | 1.925 | 2.098 |

| Youth & Adult Poverty (Ref: Non-poor youth) | |||||

| Non-Poor Adult | 1.063 | 0.037 | 0.082 | 0.992 | 1.139 |

| Minimally-Poor Youth | 1.383 | 0.038 | 0.000 | 1.310 | 1.461 |

| Minimally-Poor Adult | 1.378 | 0.039 | 0.000 | 1.302 | 1.457 |

| Moderately-Poor Youth | 1.802 | 0.050 | 0.000 | 1.706 | 1.903 |

| Moderately-Poor Adult | 1.735 | 0.050 | 0.000 | 1.641 | 1.836 |

| Highly-Poor Youth | 2.075 | 0.063 | 0.000 | 1.955 | 2.202 |

| Highly-Poor Adult | 2.065 | 0.064 | 0.000 | 1.943 | 2.194 |

| Life Stage (Youth Ref: 35 years or younger) | |||||

| Adult (36 years and older) | 0.991 | 0.012 | 0.461 | 0.969 | 1.014 |

| Gender/Sex (Ref: Male) | |||||

| Female | 1.033 | 0.012 | 0.005 | 1.010 | 1.057 |

| Educational Attainment (Ref: No formal education) | |||||

| Primary education | 0.963 | 0.017 | 0.030 | 0.931 | 0.996 |

| Secondary education | 0.953 | 0.016 | 0.003 | 0.923 | 0.984 |

| Post-secondary education | 0.922 | 0.018 | 0.000 | 0.888 | 0.958 |

| Religion (Ref: Christian) | |||||

| Muslim | 1.075 | 0.014 | 0.000 | 1.049 | 1.102 |

| Others | 0.857 | 0.018 | 0.000 | 0.824 | 0.892 |

| Employment Status (Ref: No (not looking)) | |||||

| No (looking) | 1.024 | 0.015 | 0.101 | 0.995 | 1.054 |

| Yes, part time | 1.014 | 0.019 | 0.464 | 0.977 | 1.052 |

| Yes, full time | 0.938 | 0.015 | 0.000 | 0.910 | 0.967 |

| Urbanicity (Ref: Urban residence) | |||||

| Rural residence | 0.994 | 0.012 | 0.591 | 0.971 | 1.017 |

| Variable | Odds Ratio | SE | P-Value | 95% CI | Odds Ratio | SE | P-Value | 95% CI | Odds Ratio | SE | P-Value | 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Youth & Adult Poverty (Ref: Non-poor youth) | |||||||||||||||

| Non-Poor Adult | 1.054 | 0.042 | 0.186 | 0.975 | 1.140 | 1.056 | 0.042 | 0.171 | 0.977 | 1.143 | 1.054 | 0.042 | 0.188 | 0.975 | 1.141 |

| Minimally-Poor Youth | 1.293 | 0.040 | 0.000 | 1.216 | 1.374 | 1.286 | 0.040 | 0.000 | 1.210 | 1.368 | 1.291 | 0.041 | 0.000 | 1.214 | 1.373 |

| Minimally-Poor Adult | 1.173 | 0.038 | 0.000 | 1.101 | 1.249 | 1.166 | 0.038 | 0.000 | 1.093 | 1.243 | 1.169 | 0.038 | 0.000 | 1.096 | 1.246 |

| Moderately-Poor Youth | 1.517 | 0.047 | 0.000 | 1.428 | 1.612 | 1.506 | 0.047 | 0.000 | 1.416 | 1.602 | 1.516 | 0.048 | 0.000 | 1.426 | 1.613 |

| Moderately-Poor Adult | 1.357 | 0.043 | 0.000 | 1.275 | 1.444 | 1.342 | 0.044 | 0.000 | 1.259 | 1.430 | 1.351 | 0.044 | 0.000 | 1.268 | 1.440 |

| Highly-Poor Youth | 1.644 | 0.054 | 0.000 | 1.542 | 1.753 | 1.625 | 0.054 | 0.000 | 1.523 | 1.734 | 1.637 | 0.054 | 0.000 | 1.534 | 1.747 |

| Highly-Poor Adult | 1.487 | 0.050 | 0.000 | 1.393 | 1.588 | 1.472 | 0.050 | 0.000 | 1.377 | 1.574 | 1.483 | 0.051 | 0.000 | 1.387 | 1.586 |

| Life Stage (Youth Ref: 35 years or younger) | |||||||||||||||

| Adult (36 years and older) | Omitted owing to collinearity | ||||||||||||||

| Gender/Sex (Ref: Male) | |||||||||||||||

| Female | 0.980 | 0.012 | 0.083 | 0.957 | 1.003 | 0.978 | 0.012 | 0.067 | 0.955 | 1.002 | 0.975 | 0.012 | 0.040 | 0.952 | 0.999 |

| Educational Attainment (Ref: No formal education) | |||||||||||||||

| Primary education | 1.003 | 0.018 | 0.871 | 0.968 | 1.039 | 0.996 | 0.018 | 0.835 | 0.962 | 1.032 | |||||

| Secondary education | 0.940 | 0.017 | 0.001 | 0.907 | 0.974 | 0.923 | 0.017 | 0.000 | 0.890 | 0.957 | |||||

| Post-secondary education | 0.978 | 0.021 | 0.301 | 0.938 | 1.020 | 0.955 | 0.021 | 0.038 | 0.915 | 0.998 | |||||

| Religion (Ref: Christian) | |||||||||||||||

| Muslim | 1.068 | 0.014 | 0.000 | 1.040 | 1.097 | 1.067 | 0.014 | 0.000 | 1.039 | 1.095 | |||||

| Others | 0.894 | 0.020 | 0.000 | 0.856 | 0.933 | 0.892 | 0.020 | 0.000 | 0.855 | 0.932 | |||||

| Employment Status (Ref: No (not looking)) | |||||||||||||||

| No (looking) | 1.098 | 0.017 | 0.000 | 1.066 | 1.132 | 1.094 | 0.017 | 0.000 | 1.062 | 1.128 | |||||

| Yes, part time | 1.055 | 0.021 | 0.007 | 1.015 | 1.096 | 1.049 | 0.021 | 0.014 | 1.010 | 1.091 | |||||

| Yes, full time | 1.049 | 0.018 | 0.004 | 1.015 | 1.085 | 1.045 | 0.018 | 0.010 | 1.010 | 1.080 | |||||

| Urbanicity (Ref: Urban residence) | |||||||||||||||

| Rural residence | 0.948 | 0.012 | 0.000 | 0.924 | 0.972 | ||||||||||

| Variable | Odds Ratio | SE | P-Value | 95% CI | Odds Ratio | SE | P-Value | 95% CI | Odds Ratio | SE | P-Value | 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Youth & Adult Poverty (Ref: Non-poor youth) | |||||||||||||||

| Non-Poor Adult | 1.065 | 0.037 | 0.073 | 0.994 | 1.141 | 1.0782 | 0.0382 | 0.0340 | 1.0059 | 1.1557 | 1.075 | 0.038 | 0.042 | 1.002 | 1.152 |

| Minimally-Poor Youth | 1.384 | 0.038 | 0.000 | 1.311 | 1.461 | 1.3920 | 0.0389 | 0.0000 | 1.3177 | 1.4704 | 1.398 | 0.039 | 0.000 | 1.324 | 1.477 |

| Minimally-Poor Adult | 1.382 | 0.040 | 0.000 | 1.306 | 1.461 | 1.4040 | 0.0408 | 0.0000 | 1.3263 | 1.4863 | 1.409 | 0.041 | 0.000 | 1.331 | 1.492 |

| Moderately-Poor Youth | 1.802 | 0.050 | 0.000 | 1.706 | 1.903 | 1.8227 | 0.0516 | 0.0000 | 1.7243 | 1.9266 | 1.839 | 0.052 | 0.000 | 1.740 | 1.944 |

| Moderately-Poor Adult | 1.740 | 0.050 | 0.000 | 1.645 | 1.841 | 1.7756 | 0.0521 | 0.0000 | 1.6764 | 1.8806 | 1.791 | 0.053 | 0.000 | 1.691 | 1.897 |

| Highly-Poor Youth | 2.074 | 0.063 | 0.000 | 1.955 | 2.201 | 2.1060 | 0.0647 | 0.0000 | 1.9829 | 2.2367 | 2.128 | 0.066 | 0.000 | 2.004 | 2.261 |

| Highly-Poor Adult | 2.069 | 0.064 | 0.000 | 1.948 | 2.199 | 2.1256 | 0.0675 | 0.0000 | 1.9974 | 2.2620 | 2.146 | 0.068 | 0.000 | 2.016 | 2.284 |

| Life Stage (Youth Ref: 35 years or younger) | |||||||||||||||

| Adult (36 years and older) | Omitted owing to collinearity | ||||||||||||||

| Gender/Sex (Ref: Male) | |||||||||||||||

| Female | 1.031 | 0.012 | 0.010 | 1.007 | 1.055 | 1.038 | 0.012 | 0.002 | 1.013 | 1.062 | 1.033 | 0.012 | 0.006 | 1.009 | 1.058 |

| Educational Attainment (Ref: No formal education) | |||||||||||||||

| Primary education | 1.032 | 0.019 | 0.084 | 0.996 | 1.069 | 1.023 | 0.018 | 0.207 | 0.987 | 1.060 | |||||

| Secondary education | 1.059 | 0.019 | 0.001 | 1.023 | 1.097 | 1.035 | 0.019 | 0.060 | 0.999 | 1.073 | |||||

| Post-secondary education | 1.079 | 0.023 | 0.000 | 1.035 | 1.125 | 1.047 | 0.023 | 0.037 | 1.003 | 1.092 | |||||

| Religion (Ref: Christian) | |||||||||||||||

| Muslim | 1.084 | 0.014 | 0.000 | 1.056 | 1.113 | 1.082 | 0.014 | 0.000 | 1.054 | 1.111 | |||||

| Others | 0.883 | 0.018 | 0.000 | 0.848 | 0.920 | 0.882 | 0.018 | 0.000 | 0.847 | 0.919 | |||||

| Employment Status (Ref: No (not looking)) | |||||||||||||||

| No (looking) | 1.011 | 0.015 | 0.471 | 0.981 | 1.042 | 1.006 | 0.015 | 0.688 | 0.976 | 1.037 | |||||

| Yes, part time | 1.048 | 0.020 | 0.015 | 1.009 | 1.089 | 1.041 | 0.020 | 0.038 | 1.002 | 1.081 | |||||

| Yes, full time | 1.019 | 0.017 | 0.251 | 0.987 | 1.052 | 1.012 | 0.017 | 0.461 | 0.980 | 1.045 | |||||

| Urbanicity (Ref: Urban residence) | |||||||||||||||

| Rural residence | 0.931 | 0.012 | 0.000 | 0.908 | 0.954 | ||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).