Submitted:

22 December 2025

Posted:

23 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Conventional Mobility Aids

- White Canes: Reliable for ground-level texture and immediate obstacles but lack vertical coverage and cannot detect overhead hazards [9].

- Guide Dogs: Highly effective for navigation and safety but are expensive (typically $40,000-60,000 USD), require extensive training (18-24 months), and are limited in availability with only about 10,000 guide dogs serving millions of visually impaired people in the United States alone [10].

2.2. Vision-Based Assistive Technology

- High Cost: Specialized hardware such as OrCam MyEye ($4,500) and Envision Glasses ($3,500) are often prohibitively expensive for widespread adoption [12].

- Computation Heavy: Many systems require connection to cloud servers, introducing latency (typically 200-500ms) and raising privacy concerns regarding continuous video streaming [15].

2.3. Gaps in Current Research

- Limited Detection of Overhead Obstacles: Most camera-based systems focus on forward-facing or ground-level detection, missing hazards at head height.

- Insufficient Detection of Negative Obstacles: Steps, holes, curbs, and drop-offs represent significant fall risks but are poorly addressed by current systems [20].

- Form Factor Issues: User studies indicate preferences for discrete wearables over glasses or headsets due to social acceptance and comfort during extended use [21].

2.4. Mobile AI Advancements

- Lightweight Neural Networks: Howard et al. [3] introduced MobileNets with depthwise separable convolutions, achieving efficient real-time object detection on smartphones and embedded devices with minimal computational overhead.

- Edge Computing: AI runs directly on mobile devices, reducing latency to under 50ms and preserving privacy without relying on cloud processing [23].

- Depth Estimation: Mobile AI can predict distances from single camera streams using monocular depth estimation techniques, improving obstacle awareness [24].

- Energy-Efficient Inference: Quantized and pruned models minimize power consumption to 500-800mW, allowing 6-8 hours of continuous operation on typical smartphone batteries [25].

3. Proposed System

3.1. Hardware Architecture

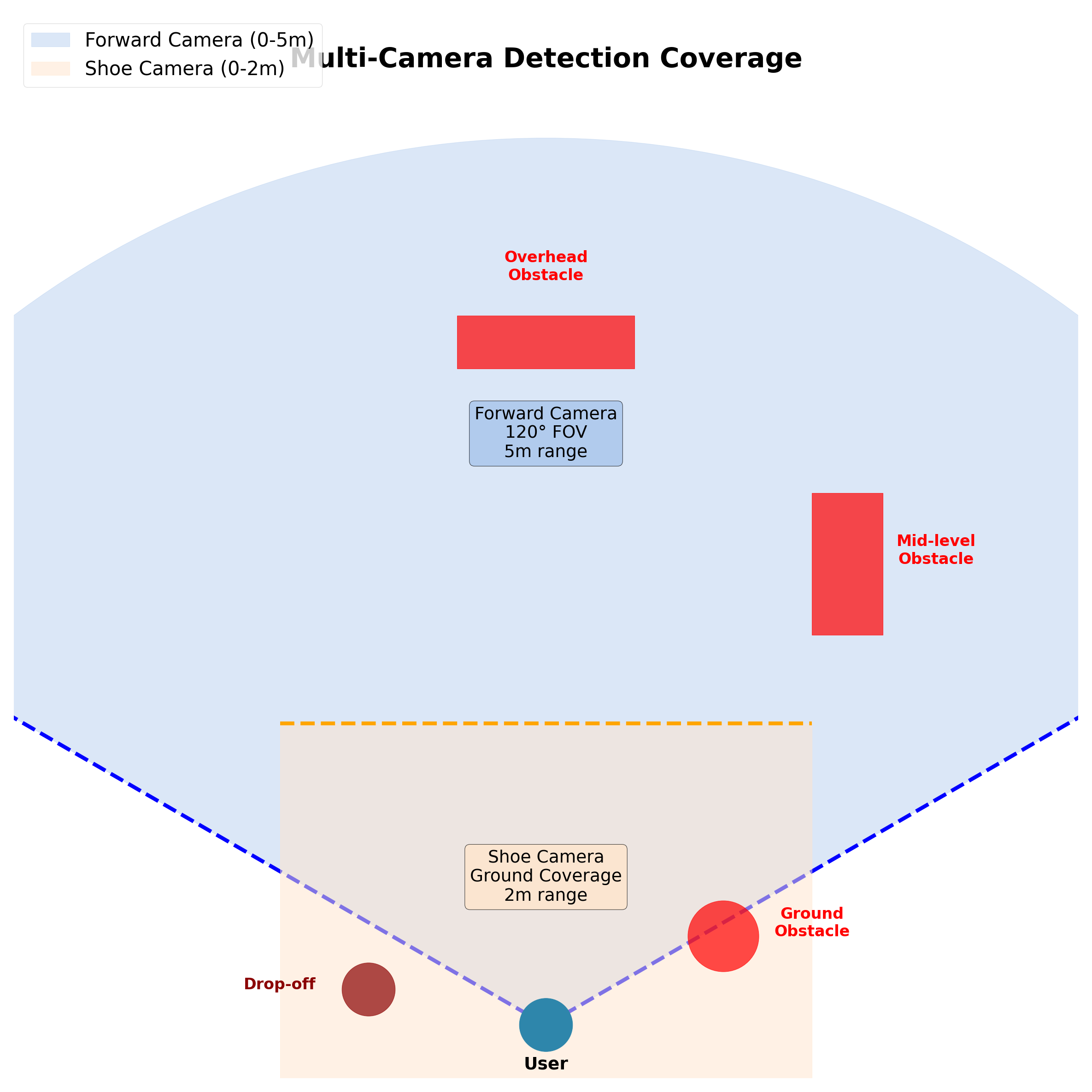

- Camera Module A (Forward Camera): A wide-angle sensor (120° field of view) mounted on a smartphone (chest pocket) or a discrete clip-on module. This covers eye-level and mid-level obstacles up to 5 meters distance.

- Camera Module B (Downward Camera): A specialized micro-camera (e.g., ESP32-CAM or similar, ~$10) mounted on the shoe or ankle. This is critical for surface-level detection (puddles, curbs, stairs) within 2 meters.

- Processing Unit: Computing is handled via a standard Android smartphone (Snapdragon 6-series or higher) or a Raspberry Pi Zero 2W (~$15) for a standalone variant.

- Feedback Interface: Bone-conduction headphones (e.g., AfterShokz, ~$80) provide audio cues without blocking ambient environmental sounds, ensuring the user remains aware of traffic and other auditory signals critical for safety [26].

3.2. Software Architecture

- Image Acquisition: Captures video streams at 15-60 FPS depending on lighting conditions and processing load.

- Image Preprocessing: Includes resizing to model input dimensions (typically 320x320 or 416x416), histogram equalization for light correction, and normalization.

- Depth Estimation: Uses monocular depth prediction networks (e.g., MiDaS [24]) to calculate the distance of obstacles in real-time.

- Object Prioritization Module: A logic layer that ranks obstacles based on immediate risk using time-to-collision metrics (e.g., a fast-approaching wall at 1.5 seconds is higher priority than a distant bench at 10 seconds).

- Feedback Module: Converts the highest priority threat into spatial audio (indicating direction using stereo panning) or haptic vibration patterns (frequency indicates urgency, pattern indicates obstacle type).

3.3. Wearable Integration and Novel Design Features

- Shoe-Mounted Advantage: The unique placement on the shoe allows for the detection of “negative obstacles” (drop-offs, stairs, curbs) and low-hanging trip hazards that chest-mounted cameras often miss due to occlusion by the user’s own body. This approach was inspired by terrain analysis systems in robotics [28].

4. Methods

4.1. Experimental Design

- Indoor Environments: Hallways with varying light conditions (50-1000 lux), cluttered spaces with furniture, and doorways.

- Outdoor Environments: Sidewalks with curbs, pedestrian crossings, parks with natural obstacles, and urban streets with dynamic elements.

- Surface Variations: Concrete, asphalt, grass, tile, and gravel to ensure the shoe camera handles texture variance and surface discontinuities.

- Hazard Scenarios: Controlled tests with overhead signage (1.8-2.2m height), simulated potholes (10-30cm depth), and temporary obstacles.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

- Mean Average Precision (mAP): For detection accuracy across different obstacle types, computed at IoU thresholds of 0.5 and 0.75.

- False Positive Rate (FPR): To ensure users are not annoyed by phantom alerts (target <5% FPR).

- False Negative Rate (FNR): Critical safety metric measuring missed obstacles (target <2% FNR for critical hazards).

- System Latency: Time from obstacle detection to user feedback, measured in milliseconds (target <100ms).

- User Confidence Score: Self-reported confidence levels (1-10 scale) before and after system use, using standardized questionnaires.

4.3. Dataset Selection and Training

- COCO Dataset: For general object detection training with 80 object categories and 200,000+ labeled images [31].

- Cityscapes: For outdoor urban navigation scenarios with 5,000 high-quality annotated images from 50 cities [32].

- NYU Depth Dataset V2: For indoor depth estimation with 1,449 densely labeled RGBD images [33].

- Custom Dataset: Shoe-level perspective images capturing negative obstacles, curbs, and stairs from below will need to be collected and annotated (target: 2,000+ images across diverse conditions).

4.4. Ethical Considerations

- Participant safety during navigation tests with immediate intervention protocols

- Privacy protection through on-device processing with no data storage or transmission

- Accessibility of consent materials in Braille and audio formats

- Right to withdraw at any time without penalty

5. Discussion

5.1. Performance Considerations

5.2. Privacy and Data Security

5.3. User Experience and Feedback Preferences

5.4. Limitations and Future Directions

- Weather Dependency: Heavy rain, snow, or fog significantly degrade camera performance. Weather-resistant enclosures and sensor fusion with ultrasonic sensors may mitigate this limitation.

- Battery Life: Continuous operation at high frame rates drains batteries in 3-5 hours. Adaptive frame rate adjustment and sleep modes during stationary periods can extend usage to 8-10 hours.

- Training Data: The custom shoe-level dataset requires substantial effort to collect and annotate. Synthetic data generation using 3D rendering engines may accelerate this process [38].

- User Acceptance: Long-term user studies are needed to assess real-world adoption, usability, and integration with existing mobility strategies [39].

6. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. World Report on Vision; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241516570 (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Tapu, R.; Mocanu, B.; Zaharia, T. Wearable assistive devices for visually impaired: A state of the art survey. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2020, 137, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. MobileNets: Efficient Convolutional Neural Networks for Mobile Vision Applications. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 7464–7475. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.; Wang, K.; Yi, W.; Lian, S. Deep Learning based Wearable Assistive System for Visually Impaired People. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW), Seoul, Korea, 27–28 October 2019; pp. 1339–1346. [Google Scholar]

- Elmannai, W.; Elleithy, K. Sensor-based assistive devices for visually-impaired people: Current status, challenges, and future directions. Sensors 2017, 17, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pundlik, S.; Tomasi, M.; Luo, G. Evaluation of a portable collision warning device for patients with peripheral vision loss in an obstacle course. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2015, 56, 2571–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dakopoulos, D.; Bourbakis, N.G. Wearable obstacle avoidance electronic travel aids for blind: A survey. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. C 2010, 40, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, J.; Sato, D.; Asakawa, S.; Dong, H.; Kitani, K.M.; Asakawa, C. Virtual navigation for blind people: Building sequential representations of the real-world. In Proceedings of the 19th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, Baltimore, MD, USA, 29 October–1 November 2017; pp. 280–289. [Google Scholar]

- Elmannai, W.; Elleithy, K. Sensor-based assistive devices for visually-impaired people: Current status, challenges, and future directions. Sensors 2017, 17, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poggi, M.; Mattoccia, S. Deep learning for assistive computer vision. In Computer Vision for Assistive Healthcare; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 25–51. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, T.; Dehlawi, Z.; Kohno, T. In situ with bystanders of augmented reality glasses: Perspectives on recording and privacy-mediating technologies. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Toronto, ON, Canada, 26 April–1 May 2014; pp. 2377–2386. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Yan, S.; Feng, J. Advancements in Smart Wearable Mobility Aids for Visual Impairments: A Bibliometric Narrative Review. Sensors 2024, 24, 7986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, D.; Oh, U.; Naito, K.; Takagi, H.; Kitani, K.; Asakawa, C. NavCog3: An evaluation of a smartphone-based blind indoor navigation assistant with semantic features in a large-scale environment. In Proceedings of the 19th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, Baltimore, MD, USA, 29 October–1 November 2017; pp. 270–279. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Pan, H.; Zhang, C.; Tian, Y. RGB-D image-based detection of stairs, pedestrian crosswalks and traffic signs. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2014, 25, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuriakose, B.; Shrestha, R.; Sandnes, F.E. Wearables for persons with blindness and low vision: form factor matters. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2024, 19, 1961–1973. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, J.; Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Li, Y.; Lian, S.; Liu, D. Wearable travel aid for environment perception and navigation of visually impaired people. Electronics 2019, 8, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nada, A.A.; Fakhr, M.A.; Seddik, A.F. Assistive infrared sensor based smart stick for blind people. In Proceedings of the 2015 Science and Information Conference (SAI), London, UK, 28–30 July 2015; pp. 1149–1154. [Google Scholar]

- Pradeep, V.; Medioni, G.; Weiland, J. Robot vision for the visually impaired. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, San Diego, CA, USA, 20–25 June 2005; pp. 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kandalan, R.N.; Namuduri, K. Techniques for constructing indoor navigation systems for the visually impaired: A review. IEEE Trans. Hum. Mach. Syst. 2020, 50, 492–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, K.; Sonsare, P.; Borkar, D.; Patil, A.; Kulkarni, V. MOLO: A hybrid approach using MobileNet and YOLO for object detection on resource constrained devices. Discov. Artif. Intell. 2025, 5, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, D.; Ullah, S.; Nabi, S. Revolutionizing Real-Time Object Detection: YOLO and MobileNet SSD Integration. J. Comput. Biomed. Inform. 2023, 6, 242–259. [Google Scholar]

- Ranftl, R.; Lasinger, K.; Hafner, D.; Schindler, K.; Koltun, V. Towards robust monocular depth estimation: Mixing datasets for zero-shot cross-dataset transfer. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2022, 44, 1623–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, B.; Kligys, S.; Chen, B.; Zhu, M.; Tang, M.; Howard, A.; Adam, H.; Kalenichenko, D. Quantization and training of neural networks for efficient integer-arithmetic-only inference. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 2704–2713. [Google Scholar]

- Maidenbaum, S.; Hanassy, S.; Abboud, S.; Buchs, G.; Chebat, D.R.; Levy-Tzedek, S.; Amedi, A. The ‘EyeCane’, a new electronic travel aid for the blind: Technology, behavior & swift learning. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 2014, 32, 813–824. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single shot multibox detector. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bellone, M.; Reina, G.; Caltagirone, L.; Wahde, M. Learning traversability from point clouds in challenging scenarios. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2018, 19, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everingham, M.; Eslami, S.M.A.; Van Gool, L.; Williams, C.K.I.; Winn, J.; Zisserman, A. The Pascal Visual Object Classes challenge: A retrospective. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2015, 111, 98–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuriakose, B.; Shrestha, R.; Sandnes, F.E. Tools and technologies for blind and visually impaired navigation support: A review. IETE Tech. Rev. 2022, 39, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft COCO: Common objects in context. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; pp. 740–755. [Google Scholar]

- Cordts, M.; Omran, M.; Ramos, S.; Rehfeld, T.; Enzweiler, M.; Benenson, R.; Franke, U.; Roth, S.; Schiele, B. The Cityscapes dataset for semantic urban scene understanding. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 3213–3223. [Google Scholar]

- Silberman, N.; Hoiem, D.; Kohli, P.; Fergus, R. Indoor segmentation and support inference from RGBD images. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Florence, Italy, 7–13 October 2012; pp. 746–760. [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Chen, Q.; Xu, J.; Koltun, V. Learning to see in the dark. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 3291–3300. [Google Scholar]

- Coughlan, J.M.; Miele, J.A. AR4VI: AR as an accessibility tool for people with visual impairments. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality Adjunct (ISMAR-Adjunct), Munich, Germany, 10–12 September 2017; pp. 288–292. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Hu, S.; Boularias, A. Multimodal feedback for navigation assistance of visually impaired individuals. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Brisbane, Australia, 21–25 May 2018; pp. 4545–4550. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Roberson, M.; Barto, C.; Mehta, R.; Sridhar, S.N.; Rosaen, K.; Vasudevan, R. Driving in the matrix: Can virtual worlds replace human-generated annotations for real world tasks? In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Singapore, 29 May–3 June 2017; pp. 746–753. [Google Scholar]

- Manduchi, R.; Coughlan, J.M. The last meter: Blind visual guidance to a target. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, San Jose, CA, USA, 7–12 May 2016; pp. 3113–3122. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).