Submitted:

22 December 2025

Posted:

23 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

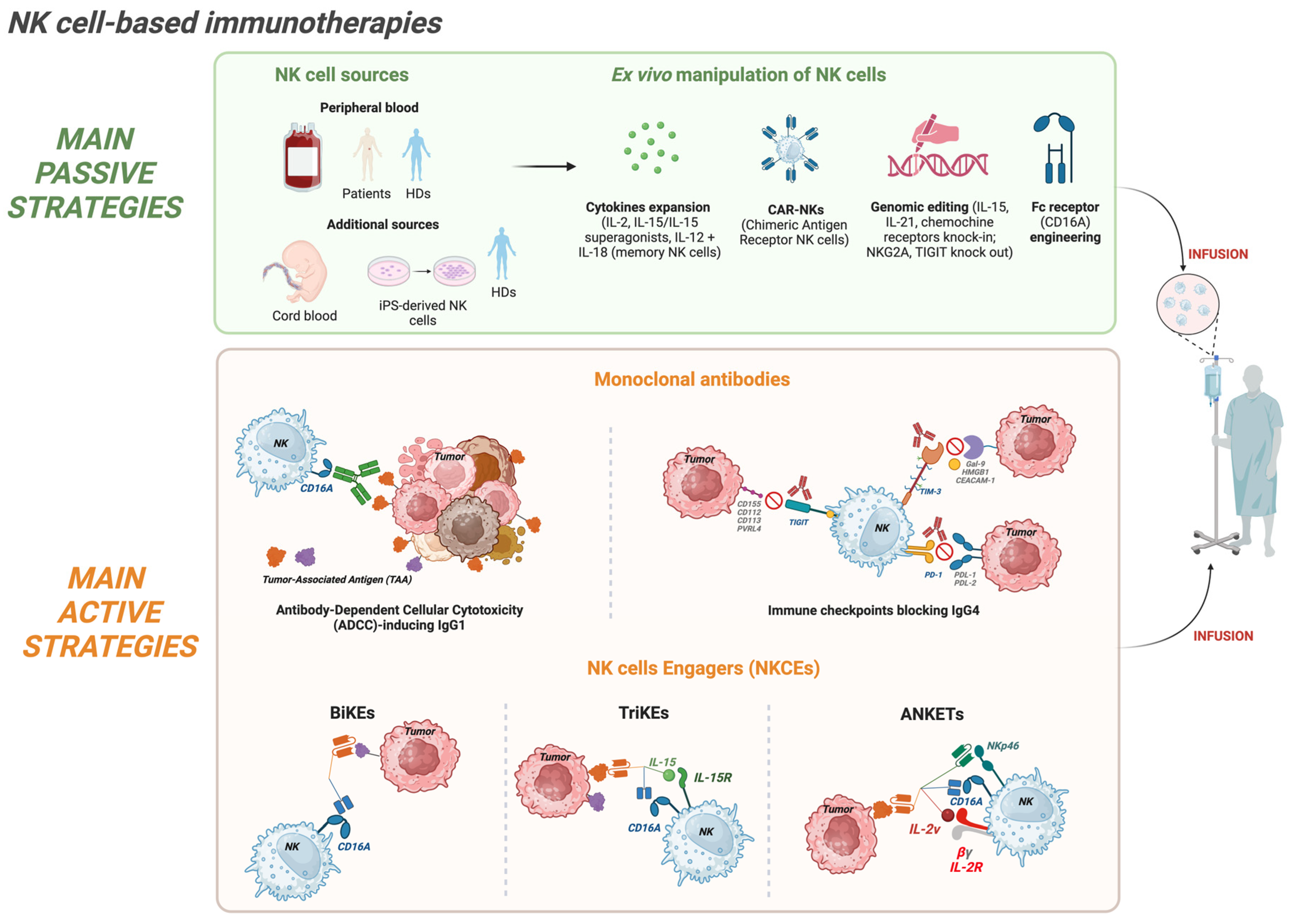

2. NK Cell-Based Immunotherapies in Oncology: Approaches, Mechanisms, and Challenges

2.1. Passive Strategies: Adoptive NK Cell Transfer

2.2. Active Strategies: NK Cell Engagers (NKCEs)

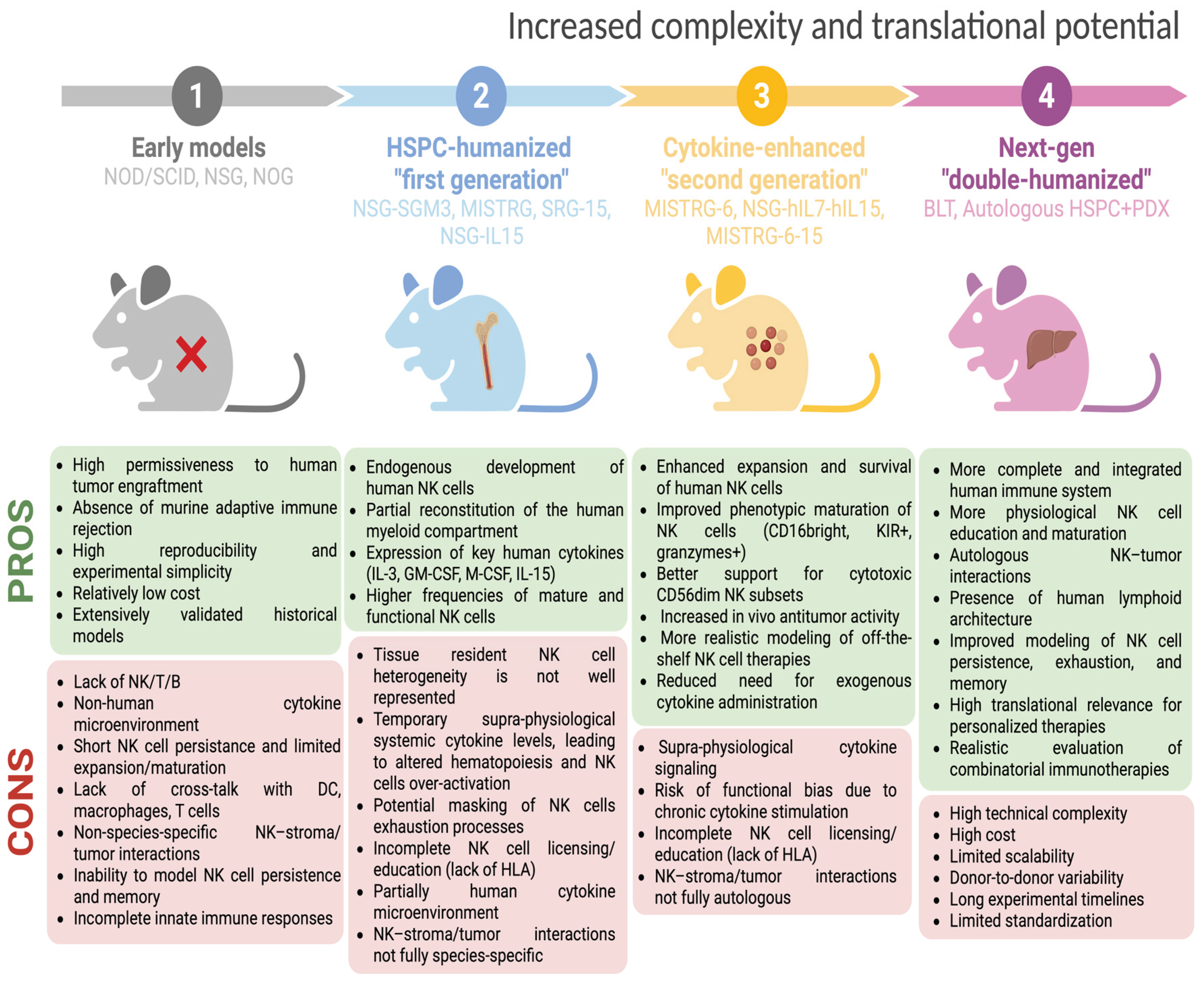

3. Preclinical Humanized Mouse Models for Assessing NK Cell-Based Strategies

3.1. Early Immunodeficient Models

3.2. Progress Towards the First Humanized Immunodeficient Models to Study Human NK Cells

4. Burning Challenges and Limitations of Current Humanized Mouse Models for Studying NK Cell-Based Therapies

5. Next-Generation Humanized Mouse Models and Innovative Technologies Unraveling Human NK Cell Dynamics in Tumor Immunity

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interests

Abbreviations

| ADCC | Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity |

| ALL | Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia |

| AML | Acute Myeloid Leukemia |

| ANKETs | Antibody-based NK cell Engager Therapeutics |

| B-NHL | B cell Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma |

| BiKEs | Bispecific NK cell Engagers |

| BM | Bone Marrow |

| CAR-NK | Chimeric Antigen Receptor-Natura Killer |

| CIML | Cytokine Induced Memory Like |

| CRS | Cytokine Release Syndrome |

| DC | Dendritic Cell |

| GvHD | Graft versus Host Disease |

| HD | Healthy donor |

| hESCs | Human Embryonic Stem Cells |

| HSC | Hematopoietic Stem Cell |

| HSPCs | Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cells |

| hu-BLT | Human BM Liver Thymus |

| IL-2 | Interleukin-2 |

| IL-2v | IL-2 variant |

| ILC | Innate Lymphoid Cell |

| iPSC | Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell |

| KIR | Killer Ig-like Receptor |

| mAbs | monoclonal Antibodies |

| MISTRG | M-CSFh/h IL-3/GM-CSFh/h SIRPαh/h TPOh/h RAG2-/- IL2Rg-/- |

| NCR | Natural cytotoxicity receptors |

| NK | Natural Killer |

| NKCEs | NK Cell Engagers |

| NOD/SCID | Non Obese Diabetic/Severe Combined Immunodeficient |

| NOG | NOD/Shi-scid/IL2Rγnull |

| NSG | NOD/SCID/γcnull |

| NSG-IL15 | transgenic for human IL-15 |

| NSG-SGM3 | NOD-scid IL2rγ⁻/⁻ transgenic for human SCF, GM-CSF, and IL-3 |

| PB | Peripheral Blood |

| PDX | Patient Derived Xenograft |

| sc RNA-seq | single-cell RNA-sequencing |

| scFv | single-chain variable Fragment |

| SRG-15 | RAG2⁻/⁻ IL2Rg⁻/⁻ transgenic for human IL-15 |

| TAAs | Tumor Associated Antigens |

| TCEs | T Cell Engagers |

| TME | Tumor Microenvironment |

| Tregs | Regulatory T cells |

| TriKEs | Trispecific NK cell Engagers |

| UBC | Umbilical Cord Blood |

References

- L. Chiossone, P. Y. Dumas, M. Vienne, and E. Vivier, “Author Correction: Natural killer cells and other innate lymphoid cells in cancer,” Nat Rev Immunol, vol. 18, no. 11, p. 726, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- F. Bellora et al., “Human NK cells and NK receptors,” Immunol Lett, vol. 161, no. 2, pp. 168–173, 2014. [CrossRef]

- L. Rebuffet et al., “High-dimensional single-cell analysis of human natural killer cell heterogeneity,” Nat Immunol, vol. 25, no. 8, pp. 1474–1488, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. D. Scoville, A. G. Freud, and M. A. Caligiuri, “Modeling Human Natural Killer Cell Development in the Era of Innate Lymphoid Cells,” Front Immunol, vol. 8, no. MAR, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. Quatrini, M. Della Chiesa, S. Sivori, M. C. Mingari, D. Pende, and L. Moretta, “Human NK cells, their receptors and function,” Eur J Immunol, vol. 51, no. 7, pp. 1566–1579, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. Borrego, M. J. Robertson, J. Ritz, J. Peña, and R. Solana, “CD69 is a stimulatory receptor for natural killer cell and its cytotoxic effect is blocked by CD94 inhibitory receptor,” Immunology, vol. 97, no. 1, pp. 159–165, 1999. [CrossRef]

- N. Anfossi et al., “Human NK cell education by inhibitory receptors for MHC class I,” Immunity, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 331–342, Aug. 2006. [CrossRef]

- S. Sivori et al., “NK cells and ILCs in tumor immunotherapy,” Mol Aspects Med, vol. 80, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Ni and C. Dong, “New B7 Family Checkpoints in Human Cancers,” Mol Cancer Ther, vol. 16, no. 7, pp. 1203–1211, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Moretta et al., “Activating receptors and coreceptors involved in human natural killer cell-mediated cytolysis,” Annu Rev Immunol, vol. 19, pp. 197–223, 2001. [CrossRef]

- A.G. Freud, B. L. Mundy-Bosse, J. Yu, and M. A. Caligiuri, “The broad spectrum of human natural killer cell diversity,” Immunity, vol. 47, no. 5, p. 820, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. Peng and R. Sun, “Liver-resident NK cells and their potential functions,” Cell Mol Immunol, vol. 14, no. 11, p. 890, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- G. Lugthart et al., “Human Lymphoid Tissues Harbor a Distinct CD69+CXCR6+ NK Cell Population,” J Immunol, vol. 197, no. 1, pp. 78–84, Jul. 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. E. Melsen et al., “Human Bone Marrow-Resident Natural Killer Cells Have a Unique Transcriptional Profile and Resemble Resident Memory CD8+ T Cells,” Front Immunol, vol. 9, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. López-Botet, A. De Maria, A. Muntasell, M. Della Chiesa, and C. Vilches, “Adaptive NK cell response to human cytomegalovirus: Facts and open issues,” Semin Immunol, vol. 65, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Peng, G. Sferruzza, L. Yang, L. Zhou, and S. Chen, “CAR-T and CAR-NK as cellular cancer immunotherapy for solid tumors,” Cell Mol Immunol, vol. 21, no. 10, pp. 1089–1108, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Basar, M. Daher, and K. Rezvani, “Next-generation cell therapies: the emerging role of CAR-NK cells,” Blood Adv, vol. 4, no. 22, pp. 5868–5876, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. J. Laskowski, A. Biederstädt, and K. Rezvani, “Natural killer cells in antitumour adoptive cell immunotherapy,” Nature Reviews Cancer 2022 22:10, vol. 22, no. 10, pp. 557–575, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Liu, V. Galat, Y. Galat4, Y. K. A. Lee, D. Wainwright, and J. Wu, “NK cell-based cancer immunotherapy: from basic biology to clinical development,” J Hematol Oncol, vol. 14, no. 1, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Shimasaki, A. Jain, and D. Campana, “NK cells for cancer immunotherapy,” Nat Rev Drug Discov, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 200–218, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Ma, J. Yu, and M. A. Caligiuri, “Natural killer cell-based immunotherapy for cancer,” J Immunol, vol. 214, no. 7, pp. 1444–1456, Jul. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. D. Blunt and S. I. Khakoo, “Harnessing natural killer cell effector function against cancer,” Immunotherapy advances, vol. 4, no. 1, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Myers and J. S. Miller, “Exploring the NK cell platform for cancer immunotherapy,” Nat Rev Clin Oncol, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 85–100, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Biederstädt and K. Rezvani, “Engineered natural killer cells for cancer therapy,” Cancer Cell, vol. 43, no. 11, pp. 1987–2013, Nov. 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. S. Miller et al., “Successful adoptive transfer and in vivo expansion of human haploidentical NK cells in patients with cancer,” Blood, vol. 105, no. 8, pp. 3051–3057, Apr. 2005. [CrossRef]

- W. Wang, A. K. Erbe, J. A. Hank, Z. S. Morris, and P. M. Sondel, “NK Cell-Mediated Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity in Cancer Immunotherapy,” Front Immunol, vol. 6, no. JUL, 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. Wiernik et al., “Targeting natural killer cells to acute myeloid leukemia in vitro with a CD16 x 33 bispecific killer cell engager and ADAM17 inhibition,” Clin Cancer Res, vol. 19, no. 14, pp. 3844–3855, Jul. 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. K. Gleason et al., “CD16xCD33 bispecific killer cell engager (BiKE) activates NK cells against primary MDS and MDSC CD33+ targets,” Blood, vol. 123, no. 19, p. 3016, May 2014. [CrossRef]

- F. Oh, M. Felices, B. Kodal, J. S. Miller, and D. A. Vallera, “Immunotherapeutic Development of a Tri-Specific NK Cell Engager Recognizing BCMA,” Immuno, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 237–249, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Fenis, O. Demaria, L. Gauthier, E. Vivier, and E. Narni-Mancinelli, “New immune cell engagers for cancer immunotherapy,” Nat Rev Immunol, vol. 24, no. 7, pp. 471–486, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Zhu, Y. Bai, Y. Nan, and D. Ju, “Natural killer cell engagers: From bi-specific to tri-specific and tetra-specific engagers for enhanced cancer immunotherapy,” Clin Transl Med, vol. 14, no. 11, p. e70046, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- O. Demaria et al., “Antitumor immunity induced by antibody-based natural killer cell engager therapeutics armed with not-alpha IL-2 variant,” Cell Rep Med, vol. 3, no. 10, p. 100783, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Li, M. Niu, W. Zhang, S. Qin, J. Zhou, and M. Yi, “CAR-NK cells for cancer immunotherapy: recent advances and future directions,” Front Immunol, vol. 15, p. 1361194, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- E. Liu et al., “Use of CAR-Transduced Natural Killer Cells in CD19-Positive Lymphoid Tumors,” N Engl J Med, vol. 382, no. 6, pp. 545–553, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Karagiannis and S. Il Kim, “iPSC-Derived Natural Killer Cells for Cancer Immunotherapy,” Mol Cells, vol. 44, no. 8, pp. 541–548, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Chen et al., “Recent advances in tumor immunotherapy based on NK cells,” Front Immunol, vol. 16, p. 1595533, Aug. 2025. [CrossRef]

- G. D. Lizana-Vasquez, M. Torres-Lugo, R. B. Dixon, J. D. Powderly, and R. F. Warin, “The application of autologous cancer immunotherapies in the age of memory-NK cells,” Front Immunol, vol. 14, p. 1167666, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. Sakamoto et al., “Phase I clinical trial of autologous NK cell therapy using novel expansion method in patients with advanced digestive cancer,” J Transl Med, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 277-, Aug. 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Tarannum, R. Romee, and R. M. Shapiro, “Innovative Strategies to Improve the Clinical Application of NK Cell-Based Immunotherapy,” Front Immunol, vol. 13, p. 859177, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Kundu, L. Durkan, M. O’Dwyer, and E. Szegezdi, “Protocol for isolation and expansion of natural killer cells from human peripheral blood scalable for clinical applications,” Biol Methods Protoc, vol. 10, no. 1, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Khanal and N. Bhattarai, “A Scalable Protocol for Ex Vivo Production of CAR-Engineered Human NK Cells,” Methods Protoc, vol. 8, no. 5, p. 102, Sep. 2025. [CrossRef]

- E. M. McErlean and H. O. McCarthy, “Non-viral approaches in CAR-NK cell engineering: connecting natural killer cell biology and gene delivery,” J Nanobiotechnology, vol. 22, no. 1, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. G. Lamb, H. G. Rangarajan, B. P. Tullius, and D. A. Lee, “Natural killer cell therapy for hematologic malignancies: successes, challenges, and the future,” Stem Cell Research & Therapy 2021 12:1, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 211-, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Harada et al., “Clinical Applications of Natural Killer Cells,” Natural Killer Cells, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- O. Lim, M. Y. Jung, Y. K. Hwang, and E. C. Shin, “Present and Future of Allogeneic Natural Killer Cell Therapy,” Front Immunol, vol. 6, no. JUN, p. 286, 2015. [CrossRef]

- H. Klingemann, “The NK-92 cell line-30 years later: its impact on natural killer cell research and treatment of cancer,” Cytotherapy, vol. 25, no. 5, pp. 451–457, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Sun, M. Elliott, and F. Souza-Fonseca-Guimaraes, “Engineered iPSC-derived natural killer cells: recent innovations in translational innate anti-cancer immunotherapy,” Clin Transl Immunology, vol. 14, no. 7, p. e70045, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- E. A. Grimm, A. Mazumder, H. Z. Zhang, and S. A. Rosenberg, “Lymphokine-activated killer cell phenomenon. Lysis of natural killer-resistant fresh solid tumor cells by interleukin 2-activated autologous human peripheral blood lymphocytes,” J Exp Med, vol. 155, no. 6, pp. 1823–1841, 1982. [CrossRef]

- A.K. Ali, N. Nandagopal, and S. H. Lee, “IL-15–PI3K–AKT–mTOR: A Critical Pathway in the Life Journey of Natural Killer Cells,” Front Immunol, vol. 6, no. JUN, p. 355, 2015. [CrossRef]

- A.H. Pillet, J. Thèze, and T. Rose, “Interleukin (IL)-2 and IL-15 have different effects on human natural killer lymphocytes,” Hum Immunol, vol. 72, no. 11, pp. 1013–1017, Nov. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yang and A. Lundqvist, “Immunomodulatory Effects of IL-2 and IL-15; Implications for Cancer Immunotherapy,” Cancers (Basel), vol. 12, no. 12, p. 3586, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. R. Rhode et al., “Comparison of the superagonist complex, ALT-803, to IL15 as cancer immunotherapeutics in animal models,” Cancer Immunol Res, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 49–60, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- I. Terrén, A. Orrantia, G. Astarloa-Pando, A. Amarilla-Irusta, O. Zenarruzabeitia, and F. Borrego, “Cytokine-Induced Memory-Like NK Cells: From the Basics to Clinical Applications,” Front Immunol, vol. 13, p. 884648, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- J.W. Leong et al., “Preactivation with IL-12, IL-15, and IL-18 Induces CD25 and a Functional High-Affinity IL-2 Receptor on Human Cytokine-Induced Memory-like Natural Killer Cells,” Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 463–473, Apr. 2014. [CrossRef]

- P. R. Kennedy, M. Felices, and J. S. Miller, “Challenges to the broad application of allogeneic natural killer cell immunotherapy of cancer,” Stem Cell Research & Therapy 2022 13:1, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 165-, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Fang et al., “Advances in NK cell production,” Cell Mol Immunol, vol. 19, no. 4, p. 460, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- V. K. Singh, “Natural killer cell-based Immunotherapy for Solid tumors: A Comprehensive Review,” 2025, Accessed: Nov. 13, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://ijbc.ir.

- L.V. Jørgensen, E. B. Christensen, M. B. Barnkob, and T. Barington, “The clinical landscape of CAR NK cells,” Experimental Hematology & Oncology 2025 14:1, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 46-, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. Basar, M. Daher, and K. Rezvani, “Next-generation cell therapies: the emerging role of CAR-NK cells,” Blood Adv, vol. 4, no. 22, pp. 5868–5876, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Müller et al., “High Cytotoxic Efficiency of Lentivirally and Alpharetrovirally Engineered CD19-Specific Chimeric Antigen Receptor Natural Killer Cells Against Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia,” Front Immunol, vol. 10, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Herrera et al., “Adult peripheral blood and umbilical cord blood NK cells are good sources for effective CAR therapy against CD19 positive leukemic cells,” Sci Rep, vol. 9, no. 1, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. Liu et al., “Cord blood NK cells engineered to express IL-15 and a CD19-targeted CAR show long-term persistence and potent antitumor activity,” Leukemia, vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 520–531, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, C. Zhang, M. He, W. Xing, R. Hou, and H. Zhang, “Co-expression of IL-21-Enhanced NKG2D CAR-NK cell therapy for lung cancer,” BMC Cancer, vol. 24, no. 1, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- X. Wang et al., “Co-expression of IL-15 and CCL21 strengthens CAR-NK cells to eliminate tumors in concert with T cells and equips them with PI3K/AKT/mTOR signal signature,” J Immunother Cancer, vol. 13, no. 6, Jun. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Carlsten et al., “Efficient mRNA-Based Genetic Engineering of Human NK Cells with High-Affinity CD16 and CCR7 Augments Rituximab-Induced ADCC against Lymphoma and Targets NK Cell Migration toward the Lymph Node-Associated Chemokine CCL19,” Front Immunol, vol. 7, no. MAR, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- F. F. Feigl et al., “Efficient Redirection of NK Cells by Genetic Modification with Chemokine Receptors CCR4 and CCR2B,” Int J Mol Sci, vol. 24, no. 4, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M.F. Hasan et al., “Knockout of the inhibitory receptor TIGIT enhances the antitumor response of ex vivo expanded NK cells and prevents fratricide with therapeutic Fc-active TIGIT antibodies,” J Immunother Cancer, vol. 11, no. 12, p. e007502, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Bexte et al., “CRISPR-Cas9 based gene editing of the immune checkpoint NKG2A enhances NK cell mediated cytotoxicity against multiple myeloma,” Oncoimmunology, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 2081415, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Bexte et al., “CRISPR/Cas9 editing of NKG2A improves the efficacy of primary CD33-directed chimeric antigen receptor natural killer cells,” Nature Communications 2024 15:1, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 8439-, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- W. Qiao, P. Dong, H. Chen, and J. Zhang, “Advances in Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Natural Killer Cell Therapy,” Cells 2024, Vol. 13, Page 1976, vol. 13, no. 23, p. 1976, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhu et al., “Metabolic Reprograming via Deletion of CISH in Human iPSC-Derived NK Cells Promotes In Vivo Persistence and Enhances Anti-tumor Activity,” Cell Stem Cell, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 224-237.e6, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Cai, B. Lu, X. Zhao, S. Zhou, and Y. Li, “iPSC-derived NK cells engineered with CD226 effectively control acute myeloid leukemia,” Exp Hematol Oncol, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 93-, Dec. 2025. [CrossRef]

- K. M. Snyder et al., “iPSC-derived natural killer cells expressing the FcγR fusion CD64/16A can be armed with antibodies for multitumor antigen targeting,” J Immunother Cancer, vol. 11, no. 12, p. e007280, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Fukutani et al., “Human iPSC-derived NK cells armed with CCL19, CCR2B, high-affinity CD16, IL-15, and NKG2D complex enhance anti-solid tumor activity,” Stem Cell Research and Therapy , vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 373-, Dec. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Gauthier, C. Laroye, D. Bensoussan, C. Boura, and V. Decot Nat, “Natural killer cells and monoclonal antibodies: Two partners for successful antibody dependent cytotoxicity against tumor cells,” Crit Rev Oncol Hematol, vol. 160, p. 103261, 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Vincken, U. Armendáriz-Martínez, and A. Ruiz-Sáenz, “ADCC: the rock band led by therapeutic antibodies, tumor and immune cells,” Front Immunol, vol. 16, p. 1548292, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- H. S. Rugo et al., “Efficacy of Margetuximab vs Trastuzumab in Patients With Pretreated ERBB2-Positive Advanced Breast Cancer: A Phase 3 Randomized Clinical Trial,” JAMA Oncol, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 573–584, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. N. Vo et al., “NK cell activation and recovery of NK cell subsets in lymphoma patients after obinutuzumab and lenalidomide treatment,” Oncoimmunology, vol. 7, no. 4, p. e1409322, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. J. van der Horst, I. S. Nijhof, T. Mutis, and M. E. D. Chamuleau, “Fc-Engineered Antibodies with Enhanced Fc-Effector Function for the Treatment of B-Cell Malignancies,” Cancers (Basel), vol. 12, no. 10, p. 3041, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. T. Abdeldaim and K. Schindowski, “Fc-Engineered Therapeutic Antibodies: Recent Advances and Future Directions,” Pharmaceutics, vol. 15, no. 10, p. 2402, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. J. Dixon, J. Wu, and B. Walcheck, “Engineering Anti-Tumor Monoclonal Antibodies and Fc Receptors to Enhance ADCC by Human NK Cells,” Cancers 2021, Vol. 13, Page 312, vol. 13, no. 2, p. 312, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chu et al., “Combinatorial immunotherapy of N-803 (IL-15 superagonist) and dinutuximab with ex vivo expanded natural killer cells significantly enhances in vitro cytotoxicity against GD2+ pediatric solid tumors and in vivo survival of xenografted immunodeficient NSG mice,” J Immunother Cancer, vol. 9, no. 7, p. 2267, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. Antosova et al., “SOT101 induces NK cell cytotoxicity and potentiates antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity and anti-tumor activity,” Front Immunol, vol. 13, p. 989895, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. P. Patel et al., “Phase 1/2 study of monalizumab plus durvalumab in patients with advanced solid tumors,” J Immunother Cancer, vol. 12, no. 2, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Felices et al., “CD16-IL15-CD33 Trispecific Killer Engager (TriKE) induces NK cell expansion, persistence, and myeloid blast antigen specific killing.,” The Journal of Immunology, vol. 196, no. 1_Supplement, pp. 75.8-75.8, May 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Phung, J. S. Miller, and M. Felices, “Bi-specific and Tri-specific NK Cell Engagers: The New Avenue of Targeted NK Cell Immunotherapy,” Mol Diagn Ther, vol. 25, no. 5, pp. 577–592, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Gauthier et al., “Control of acute myeloid leukemia by a trifunctional NKp46-CD16a-NK cell engager targeting CD123,” Nat Biotechnol, vol. 41, no. 9, pp. 1296–1306, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. B. Reusing et al., “CD16xCD33 Bispecific Killer Cell Engager (BiKE) as potential immunotherapeutic in pediatric patients with AML and biphenotypic ALL,” Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy, vol. 70, no. 12, pp. 3701–3708, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Schmitt et al., “The bispecific innate cell engager AFM28 eliminates CD123+ leukemic stem and progenitor cells in AML and MDS,” Nat Commun, vol. 16, no. 1, Dec. 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Kiefer et al., “Dual Targeting of Glioblastoma Cells with Bispecific Killer Cell Engagers Directed to EGFR and ErbB2 (HER2) Facilitates Effective Elimination by NKG2D-CAR-Engineered NK Cells,” Cells, vol. 13, no. 3, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Felices et al., “Potent Cytolytic Activity and Specific IL15 Delivery in a Second-Generation Trispecific Killer Engager,” Cancer Immunol Res, vol. 8, no. 9, pp. 1139–1149, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Winidmanokul, A. Panya, and S. Okada, “Tri-specific killer engager: unleashing multi-synergic power against cancer,” Open Exploration 2019 5:2, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 432–448, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. Colomar-Carando et al., “Exploiting Natural Killer Cell Engagers to Control Pediatric B-cell Precursor Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia,” Cancer Immunol Res, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 291–302, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A.N. Shouse, K. M. LaPorte, and T. R. Malek, “Interleukin-2 signaling in the regulation of T cell biology in autoimmunity and cancer,” Immunity, vol. 57, no. 3, pp. 414–428, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- E. F. Conant, K. R. Fox, and W. T. Miller, “Pulmonary edema as a complication of interleukin-2 therapy,” AJR Am J Roentgenol, vol. 152, no. 4, pp. 749–752, 1989. [CrossRef]

- O. Demaria et al., “Preclinical assessment of IPH6501, a first-in-class IL2v-armed tetraspecific NK cell engager directed against CD20 for R/R B-NHL, in comparison with a CD20-targeting T cell engager.,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, vol. 42, no. 16_suppl, pp. 7030–7030, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Shang, S. Hu, and X. Wang, “Targeting natural killer cells: from basic biology to clinical application in hematologic malignancies,” Exp Hematol Oncol, vol. 13, no. 1, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. H. Shin, E. Oh, and D. Minn, “Current Developments in NK Cell Engagers for Cancer Immunotherapy: Focus on CD16A and NKp46,” Immune Netw, vol. 24, no. 5, p. e34, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Zhang, H. Soleimani Samarkhazan, Z. Pooraskari, and A. Bayani, “Beyond CAR-T: Engineered NK cell therapies (CAR-NK, NKCEs) in next-generation cancer immunotherapy,” Crit Rev Oncol Hematol, vol. 214, p. 104912, Oct. 2025. [CrossRef]

- T. Huan, B. Guan, H. Li, X. Tu, C. Zhang, and B. Tang, “Principles and current clinical landscape of NK cell engaging bispecific antibody against cancer,” Hum Vaccin Immunother, vol. 19, no. 2, p. 2256904, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. C. M. Van der Loo, H. Hanenberg, R. J. Cooper, F. Y. Luo, E. N. Lazaridis, and D. A. Williams, “Nonobese Diabetic/Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (NOD/SCID) Mouse as a Model System to Study the Engraftment and Mobilization of Human Peripheral Blood Stem Cells,” Blood, vol. 92, no. 7, pp. 2556–2570, Oct. 1998. [CrossRef]

- M. Ito et al., “NOD/SCID/gamma(c)(null) mouse: an excellent recipient mouse model for engraftment of human cells,” Blood, vol. 100, no. 9, pp. 3175–3182, Nov. 2002. [CrossRef]

- M. Ito, K. Kobayashi, and T. Nakahata, “NOD/Shi-scid IL2rgamma(null) (NOG) mice more appropriate for humanized mouse models,” Curr Top Microbiol Immunol, vol. 324, pp. 53–76, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Castriconi et al., “Human NK cell infusions prolong survival of metastatic human neuroblastoma-bearing NOD/scid mice,” Cancer Immunol Immunother, vol. 56, no. 11, pp. 1733–1742, Nov. 2007. [CrossRef]

- J. S. Hoogstad-van Evert et al., “Umbilical cord blood CD34+ progenitor-derived NK cells efficiently kill ovarian cancer spheroids and intraperitoneal tumors in NOD/SCID/IL2Rgnull mice,” Oncoimmunology, vol. 6, no. 8, Aug. 2017. [CrossRef]

- U. Siegler, C. P. Kalberer, P. Nowbakht, S. Sendelov, S. Meyer-Monard, and A. Wodnar-Filipowicz, “Activated natural killer cells from patients with acute myeloid leukemia are cytotoxic against autologous leukemic blasts in NOD/SCID mice,” Leukemia, vol. 19, no. 12, pp. 2215–2222, 2005. [CrossRef]

- M. Shiokawa et al., “In vivo assay of human NK-dependent ADCC using NOD/SCID/gammac(null) (NOG) mice,” Biochem Biophys Res Commun, vol. 399, no. 4, pp. 733–737, Sep. 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. Parodi et al., “Murine models to study human NK cells in human solid tumors,” Front Immunol, vol. 14, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. T. Kim, G. Bresson-Tan, and J. A. Zack, “Current Advances in Humanized Mouse Models for Studying NK Cells and HIV Infection,” Microorganisms, vol. 11, no. 8, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. A et al., “Corrigendum: Development and function of human innate immune cells in a humanized mouse model,” Nat Biotechnol, vol. 35, no. 12, p. 1211, 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. De Jong and T. Maina, “Of Mice and Humans: Are They the Same?—Implications in Cancer Translational Research,” Journal of Nuclear Medicine, vol. 51, no. 4, pp. 501–504, Apr. 2010. [CrossRef]

- S. Mun, H. J. Lee, and P. Kim, “Rebuilding the microenvironment of primary tumors in humans: a focus on stroma,” Experimental & Molecular Medicine 2024 56:3, vol. 56, no. 3, pp. 527–548, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Xu et al., “New genetic and epigenetic insights into the chemokine system: the latest discoveries aiding progression toward precision medicine,” Cell Mol Immunol, vol. 20, no. 7, pp. 739–776, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Chamberlain, K. Wright, A. Rot, B. Ashton, and J. Middleton, “Murine mesenchymal stem cells exhibit a restricted repertoire of functional chemokine receptors: comparison with human,” PLoS One, vol. 3, no. 8, Aug. 2008. [CrossRef]

- N. B. Horowitz, I. Mohammad, U. Y. Moreno-Nieves, I. Koliesnik, Q. Tran, and J. B. Sunwoo, “Humanized Mouse Models for the Advancement of Innate Lymphoid Cell-Based Cancer Immunotherapies,” Front Immunol, vol. 12, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Zlotnik, O. Yoshie, and H. Nomiyama, “The chemokine and chemokine receptor superfamilies and their molecular evolution,” Genome Biol, vol. 7, no. 12, Dec. 2006. [CrossRef]

- M. Wunderlich, F.-S. Chou, B. Mizukawa, K. A. Link, and J. C. Mulloy, “A New Immunodeficient Mouse Strain, NOD/SCID IL2Rγ−/− SGM3, Promotes Enhanced Human Hematopoietic Cell Xenografts with a Robust T Cell Component.,” Blood, vol. 114, no. 22, pp. 3524–3524, Nov. 2009. [CrossRef]

- D. Herndler-Brandstetter et al., “Humanized mouse model supports development, function, and tissue residency of human natural killer cells,” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 114, no. 45, pp. E9626–E9634, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Brehm, K.-E. Aryee, L. Bruzenksi, D. L. Greiner, L. D. Shultz, and J. Keck, “Transgenic expression of human IL15 in NOD-scid IL2rgnull (NSG) mice enhances the development and survival of functional human NK cells,” The Journal of Immunology, vol. 200, no. Supplement_1, pp. 103.20-103.20, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. E. Aryee et al., “Enhanced development of functional human NK cells in NOD-scid-IL2rgnull mice expressing human IL15,” FASEB J, vol. 36, no. 9, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S.A. Abeynaike et al., “Human Hematopoietic Stem Cell Engrafted IL-15 Transgenic NSG Mice Support Robust NK Cell Responses and Sustained HIV-1 Infection,” Viruses, vol. 15, no. 2, p. 365, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Chuprin et al., “Humanized mouse models for immuno-oncology research,” Nat Rev Clin Oncol, vol. 20, no. 3, p. 192, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T.M. Allen et al., “Humanized immune system mouse models: progress, challenges and opportunities,” Nature Immunology 2019 20:7, vol. 20, no. 7, pp. 770–774, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Chen et al., “The development and improvement of immunodeficient mice and humanized immune system mouse models,” Front Immunol, vol. 13, p. 1007579, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Cooper et al., “Human natural killer cells: a unique innate immunoregulatory role for the CD56bright subset,” Blood, vol. 97, no. 10, pp. 3146–3151, May 2001. [CrossRef]

- A. Poli, T. Michel, M. Thérésine, E. Andrès, F. Hentges, and J. Zimmer, “CD56bright natural killer (NK) cells: an important NK cell subset,” Immunology, vol. 126, no. 4, p. 458, 2009. [CrossRef]

- F. Bellora et al., “The interaction of human natural killer cells with either unpolarized or polarized macrophages results in different functional outcomes,” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 107, no. 50, pp. 21659–21664, Dec. 2010. [CrossRef]

- E. Vivier, E. Tomasello, M. Baratin, T. Walzer, and S. Ugolini, “Functions of natural killer cells,” Nat Immunol, vol. 9, no. 5, pp. 503–510, May 2008. [CrossRef]

- L. Yin, X.-J. Wang, D.-X. Chen, X.-N. Liu, and X.-J. Wang, “Humanized mouse model: a review on preclinical applications for cancer immunotherapy,” Am J Cancer Res, vol. 10, no. 12, p. 4568, 2020, Accessed: Dec. 05, 2025. [Online]. Available.

- C. M. Sungur et al., “Human NK cells confer protection against HIV-1 infection in humanized mice,” J Clin Invest, vol. 132, no. 24, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Shen et al., “Unraveling NK cell heterogeneity through single-cell sequencing: insights from physiological and tumor contexts for clinical applications,” Front Immunol, vol. 16, p. 1612352, Jul. 2025. [CrossRef]

- E. Hashemi and S. Malarkannan, “Tissue-Resident NK Cells: Development, Maturation, and Clinical Relevance,” Cancers (Basel), vol. 12, no. 6, pp. 1–23, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. Le, R. K. Reeves, and L. R. McKinnon, “The functional diversity of tissue-resident natural killer cells against infection,” Immunology, vol. 167, no. 1, pp. 28–39, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Z. Pan, Y. S. Ye, C. Liu, and W. Li, “Role of liver-resident NK cells in liver immunity,” Hepatol Int, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 315–324, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- I. Filipovic et al., “29-Color Flow Cytometry: Unraveling Human Liver NK Cell Repertoire Diversity,” Front Immunol, vol. 10, p. 494855, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Soleimanian and R. Yaghobi, “Harnessing Memory NK Cell to Protect Against COVID-19,” Front Pharmacol, vol. 11, p. 560516, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. Brownlie et al., “Expansions of adaptive-like NK cells with a tissue-resident phenotype in human lung and blood,” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 118, no. 11, p. e2016580118, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- X. W. Wei, Y. C. Zhang, F. Wu, F. J. Tian, and Y. Lin, “The role of extravillous trophoblasts and uterine NK cells in vascular remodeling during pregnancy,” Front Immunol, vol. 13, p. 951482, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Faas and P. de Vos, “Uterine NK cells and macrophages in pregnancy,” Placenta, vol. 56, pp. 44–52, Aug. 2017. [CrossRef]

- G. Ferlazzo et al., “Distinct roles of IL-12 and IL-15 in human natural killer cell activation by dendritic cells from secondary lymphoid organs,” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 101, no. 47, pp. 16606–16611, Nov. 2004. [CrossRef]

- R. Thomas and X. Yang, “NK-DC Crosstalk in Immunity to Microbial Infection,” J Immunol Res, vol. 2016, 2016. [CrossRef]

- O. Chijioke and C. Münz, “Dendritic cell derived cytokines in human natural killer cell differentiation and activation,” Front Immunol, vol. 4, no. NOV, 2013. [CrossRef]

- N. D. Huntington et al., “IL-15 trans-presentation promotes human NK cell development and differentiation in vivo,” J Exp Med, vol. 206, no. 1, pp. 25–34, Jan. 2009. [CrossRef]

- C. Flahou, T. Morishima, H. Takizawa, and N. Sugimoto, “Fit-For-All iPSC-Derived Cell Therapies and Their Evaluation in Humanized Mice With NK Cell Immunity,” Front Immunol, vol. 12, p. 662360, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Mian, F. Anjos-Afonso, and D. Bonnet, “Advances in Human Immune System Mouse Models for Studying Human Hematopoiesis and Cancer Immunotherapy,” Front Immunol, vol. 11, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Zalfa and S. Paust, “Natural Killer Cell Interactions With Myeloid Derived Suppressor Cells in the Tumor Microenvironment and Implications for Cancer Immunotherapy,” Front Immunol, vol. 12, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Guil-Luna, C. Sedlik, and E. Piaggio, “Humanized Mouse Models to Evaluate Cancer Immunotherapeutics,” Annu Rev Cancer Biol, vol. 5, no. Volume 5, 2021, pp. 119–136, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Gu, J. Li, M. Y. Li, and Y. Liu, “Patient-derived xenograft model in cancer: establishment and applications,” MedComm (Beijing), vol. 6, no. 2, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. Jin, K. Yoshimura, M. Sewastjanow-Silva, S. Song, and J. A. Ajani, “Challenges and Prospects of Patient-Derived Xenografts for Cancer Research,” Cancers (Basel), vol. 15, no. 17, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Jackson and G. J. Thomas, “Human tissue models in cancer research: looking beyond the mouse,” Dis Model Mech, vol. 10, no. 8, p. 939, Aug. 2017. [CrossRef]

- B. Olson, Y. Li, Y. Lin, E. T. Liu, and A. Patnaik, “Mouse Models for Cancer Immunotherapy Research,” Cancer Discov, vol. 8, no. 11, pp. 1358–1365, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. Stripecke et al., “Innovations, challenges, and minimal information for standardization of humanized mice,” EMBO Mol Med, vol. 12, no. 7, p. e8662, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- W. N. Liu et al., “Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals anti-tumor potency of CD56+ NK cells and CD8+ T cells in humanized mice via PD-1 and TIGIT co-targeting,” Mol Ther, vol. 32, no. 11, pp. 3895–3914, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. Morcillo-Martín-Romo et al., “The Role of NK Cells in Cancer Immunotherapy: Mechanisms, Evasion Strategies, and Therapeutic Advances,” Biomedicines 2025, Vol. 13, Page 857, vol. 13, no. 4, p. 857, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. Paolini and R. Molfetta, “Dysregulation of DNAM-1-Mediated NK Cell Anti-Cancer Responses in the Tumor Microenvironment,” Cancers 2023, Vol. 15, Page 4616, vol. 15, no. 18, p. 4616, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Carrega et al., “Natural killer cells infiltrating human nonsmall-cell lung cancer are enriched in CD56 bright CD16(-) cells and display an impaired capability to kill tumor cells,” Cancer, vol. 112, no. 4, pp. 863–875, Feb. 2008. [CrossRef]

- H. Jia, H. Yang, H. Xiong, and K. Q. Luo, “NK cell exhaustion in the tumor microenvironment,” Front Immunol, vol. 14, p. 1303605, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Bi and Z. Tian, “NK cell exhaustion,” Front Immunol, vol. 8, no. JUN, p. 278004, Jun. 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. T. Kim and J. A. Zack, “A humanized mouse model to study NK cell biology during HIV infection,” J Clin Invest, vol. 132, no. 24, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Rafei et al., “CREM is a regulatory checkpoint of CAR and IL-15 signalling in NK cells,” Nature 2025 643:8073, vol. 643, no. 8073, pp. 1076–1086, Jun. 2025. [CrossRef]

- X. Xu et al., “Signaling intact membrane-bound IL-15 enables potent anti-tumor activity and safety of CAR-NK cells,” Front Immunol, vol. 16, p. 1658580, Sep. 2025. [CrossRef]

- D. Feng et al., “Expression of membrane-bound Interleukin-15 sustains the growth and survival of CAR-NK cells,” Int Immunopharmacol, vol. 166, p. 115577, Dec. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Felices et al., “Continuous treatment with IL-15 exhausts human NK cells via a metabolic defect,” JCI Insight, vol. 3, no. 3, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Matsuda et al., “Human NK cell development in hIL-7 and hIL-15 knockin NOD/SCID/IL2rgKO mice,” Life Sci Alliance, vol. 2, no. 2, p. e201800195, 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Chen et al., “Comparison of NSG-Quad and MISTRG-6 humanized mice for modeling circulating and tumor-infiltrating human myeloid cells,” Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev, vol. 33, no. 2, p. 101487, Jun. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Chiorazzi et al., “Autologous humanized PDX modeling for immuno-oncology recapitulates features of the human tumor microenvironment,” J Immunother Cancer, vol. 11, no. 7, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Kaur, P. Topchyan, and A. Jewett, “Supercharged Natural Killer (sNK) Cells Inhibit Melanoma Tumor Progression and Restore Endogenous NK Cell Function in Humanized BLT Mice,” Cancers (Basel), vol. 17, no. 15, p. 2430, Aug. 2025. [CrossRef]

- K. Kaur and A. Jewett, “Differences in Tumor Growth and Differentiation in NSG and Humanized-BLT Mice; Analysis of Human vs. Humanized-BLT-Derived NK Expansion and Functions,” Cancers (Basel), vol. 15, no. 1, p. 112, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. Koning Christelle Retière, D. Salvatori, D. H. Raulet, J. Jeroen van Bergen, A. Thompson, and M. van Pel, “Humanized Mouse Model Expression Level and Frequency in a HLA Reduces Killer Cell Ig-like Receptor Downloaded from,” J Immunol The Journal of Immunology at, vol. 190, pp. 2880–2885, 2013. [CrossRef]

- V. Landtwing et al., “Cognate HLA absence in trans diminishes human NK cell education,” J Clin Invest, vol. 126, no. 10, pp. 3772–3782, Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- L. Li et al., “Loss of metabolic fitness drives tumor resistance after CAR-NK cell therapy and can be overcome by cytokine engineering,” Sci Adv, vol. 9, no. 30, p. eadd6997, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. T. Pham et al., “In Vivo PET Imaging of 89Zr-Labeled Natural Killer Cells and the Modulating Effects of a Therapeutic Antibody,” J Nucl Med, vol. 65, no. 7, pp. 1035–1042, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. Sato et al., “In-vivo tracking of adoptively transferred natural killer-cells in rhesus macaques using 89Zirconium-oxine cell labeling and PET imaging,” Clin Cancer Res, vol. 26, no. 11, p. 2573, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).