1. Introduction

Viral outbreaks have caused severe global morbidity and mortality over the past century. Five hundred million people infected and at least 500 million dead in the 1918 influenza pandemic. [

1] Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) has been responsible for about 44.1 million deaths, while approximately 41 million people were living with it by 2024. [

2] Additionally, hepatitis B virus impacts over 250 million people worldwide and led to about 1.1 million deaths in 2022. [

3] The past 20 years show high rates of virus-related infections such as the SARS-CoV epidemic in 2003, the swine flu epidemic in 2009, the MERS-CoV epidemic in 2012, the Ebola outbreak in West Africa from 2013 to 2016, the Zika virus disease epidemic from 2015 to 2016, the COVID-19 pandemic spanning from 2019 to 2022, as well as more recent outbreaks like Mpox (2022–2023) and dengue (2024–2025). [

2] Growing global travel, urbanization, and climate change now allow viruses to spread rapidly, increasing the urgency for novel antiviral strategies. [

4]

As of 1st of August 2025, 39 antiviral combinations and 98 antiviral agents have been approved against 13 human viruses, including VZV, CMV, HSV, HIV, HBV, HCV, HPV, Ebola virus, variola virus, molluscum contagiosum virus, RSV, SARS-CoV-2, and influenza virus. [

2] Most only suppress replication and do not cure latent or chronic infection. [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9] Thus, developing low-cost non-pharmacological modalities that can destroy viruses is an ongoing worldwide health priority. Recent advances in physical virology demonstrate that viral particles act as nanoscale mechanical systems with quantifiable stiffness, elasticity and vibrational modes which can provide such an approach. [

10,

11]

Based on theoretical and computational models, there are specific resonance frequencies within viruses in which externally applied acoustic energy increases oscillation in the capsid, envelopes, or surface glycoproteins, resulting in structural collapse, loss of infectivity and irreversible deformation [

12,

13] Enveloped viruses may also be more prone to mechanical damage in this manner because of their composite structure where a lipid bilayer envelope is studded with spike glycoproteins surrounding a protein capsid and nucleic acid core. This spike proteins protrude from virus surface indicate mechanically vulnerable and susceptible structures [

12]. Ultrasound, an established technology for diagnostic examination and treatment, has thus been recommended as a potential method for provision of a controlled mechanical energy capable of disrupting the viral ultrastructure without chemical materials [

14].

The study was originally designed to evaluate destruction of the virus by measuring topographical changes with advanced imaging like Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) or electron microscopy (EM). Since these instruments were not available for biological samples, the methodology was modified to monitor changes in the values of cycle threshold (Ct) as a rough indicator of viral disruption. Although indirect, these observations provide preliminary experimental support for ultrasound-mediated viral disruption and warrant future examinations employing high-resolution imaging modalities such as AFM or cryo-EM to correlate acoustic exposure with structural damage. It is important to note that the implications of this approach are not restricted to SARS-CoV-2. If resonance-based mechanical disruption is successful, that is a widely applicable strategy against other enveloped viruses (e.g., recognized pathogens like HIV and hepatitis viruses), and even emerging viral threats. Therefore, elucidation on the impact of viral structure, envelope composition, and spike architecture on acoustic susceptibility may also lead to the development of a low-cost non-pharmacological antiviral modality relevant to contemporary and future pandemics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

A true experimental design with both pre and post-test was used for evaluating the ultrasound effects on SARS-CoV-2. The experiment was conducted in public health main laboratory in a controlled laboratory environment, equipped with biosafety measures to handle viral samples safely and effectively.

2.2. Sample Preparation and Study Experiment

Viral transport medium (VTM) from nasal swabs of confirmed COVID-19 patients was collected. A volume of 0.5 ml of viral suspension was added to 2.5 ml of distilled water and mixed well in a 6 ml sized test tube. Ultrasound transducer was placed inside the tube, keeping the 2 cm distance from the tip of the transducer to the bottom of the tube to ensure that the virus suspension can be set on the focus length of transducer.

The ultrasound functioning generator, Textronix AFG31051, was configured with the following settings:

Mode: Burst

Frequency: 25 MHz

Phase: 0°

Amplitude: 7 Vpp

Offset: 0 mV

Burst Mode Type: N Cycles

Cycles per Burst: 25

Trigger Delay: 0 ns

Trigger Source: internal

Trigger Interval: 1 ms (1000 bursts/sec)

Burst Duration: 1 µs (from 25 cycles @ 25 MHz)

Repetition Rate: 1,000 bursts/sec (1 kHz)

Output Control: Manual (ON/OFF)

The power output of the generator was calculated at 7 Vpp to be approximately 122 mW, which is within the 125-mW limit specified for the transducer. Using a 25 MHz focused immersion transducer with Surface area of 3.17 ×10^ (-5) m2 and a medium approximated to water (density (ρ)=1000 kg/m3), the acoustic pressure was calculated using this equation √2ρcI. The resulting acoustic pressure was 107.5kPa, slightly exceeding the 0.1 MP threshold needed for virus destruction as suggested by modelling research.

Each sample was exposed to ultrasound for a fixed duration of 5 minutes. Post ultrasound application, Ct values were estimated again to assess changes in viral load.

After applying the ultrasound waves CT values were recorded again for each sample. The following Cutoff values were used to categorize the values into groups:

2.3. Statistical analysis

SPSS software on windows operating system was used to describe and analyse data. Descriptive results include frequency, mean and standard deviation of all variables were performed to present demographic data and Ct values differences. Moreover, paired sample t-test, and Monte Carlo test was used to evaluate the significance of the difference between the pretest and post-test values and viral loads. Effect size was calculated to measure the magnitude of this difference. Cohen’s d calculated using the formula

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of The Study Population and Ct Value Distribution

Table 1 shows that the age ranged between 1 month and 88 years with mean value of 28.67 ± 26.240. Among the study population, 29.5% were children aged less than 5 years, 4.5% were aged 5 to 14 years, and 9.1% were aged over 75 years. Regarding gender prevalence, male sex was accounted for 40.9% and female for 59.1%. Fig. 1 provides the boxplot depicting the comparison between post-test and pretest Ct values which demonstrates a symmetrical centered distribution with value 6 which is also at the center between lower third and upper third quartiles. Furthermore, the normal Q-Q plot for the difference scores (

Figure 2) suggests that most cases fall approximately on the diagonal reference line, indicating a normal distribution. These findings are also supported by a Shapiro-Wilk test (P = 0.126) and hence the parametric statistical analysis (paired t-test) can be used in subsequent analysis.

3.2. Figures, Tables and Schemes

Figure 1.

Boxplot of the computed post-test and pretest Ct values differences.

Figure 1.

Boxplot of the computed post-test and pretest Ct values differences.

Figure 2.

Normal Q-Q plot of the computed post-test and pretest Ct values differences.

Figure 2.

Normal Q-Q plot of the computed post-test and pretest Ct values differences.

Table 1.

Distribution of the cases according to their demographic data and Shapiro-Wilk normality test for difference between post and pretest Ct values.

Table 1.

Distribution of the cases according to their demographic data and Shapiro-Wilk normality test for difference between post and pretest Ct values.

| Personal Characteristics |

No. (44) |

Personal Characteristics |

|

Age by years

< 5

5-

14-

≥ 75

Mean ± SD#= 28.67 ± 26.240 |

13

2

25

4 |

29.5

4.5

56.8

9.1 |

|

Sex

Male

Female |

18

26 |

40.9

59.1 |

Difference between Post-test and Pretest Ct Values

Min

Max

Mean ± SD1 |

1

10

6.08±2.510 |

|

Shapiro-Wilk Test for Normality

P value |

0.126 |

|

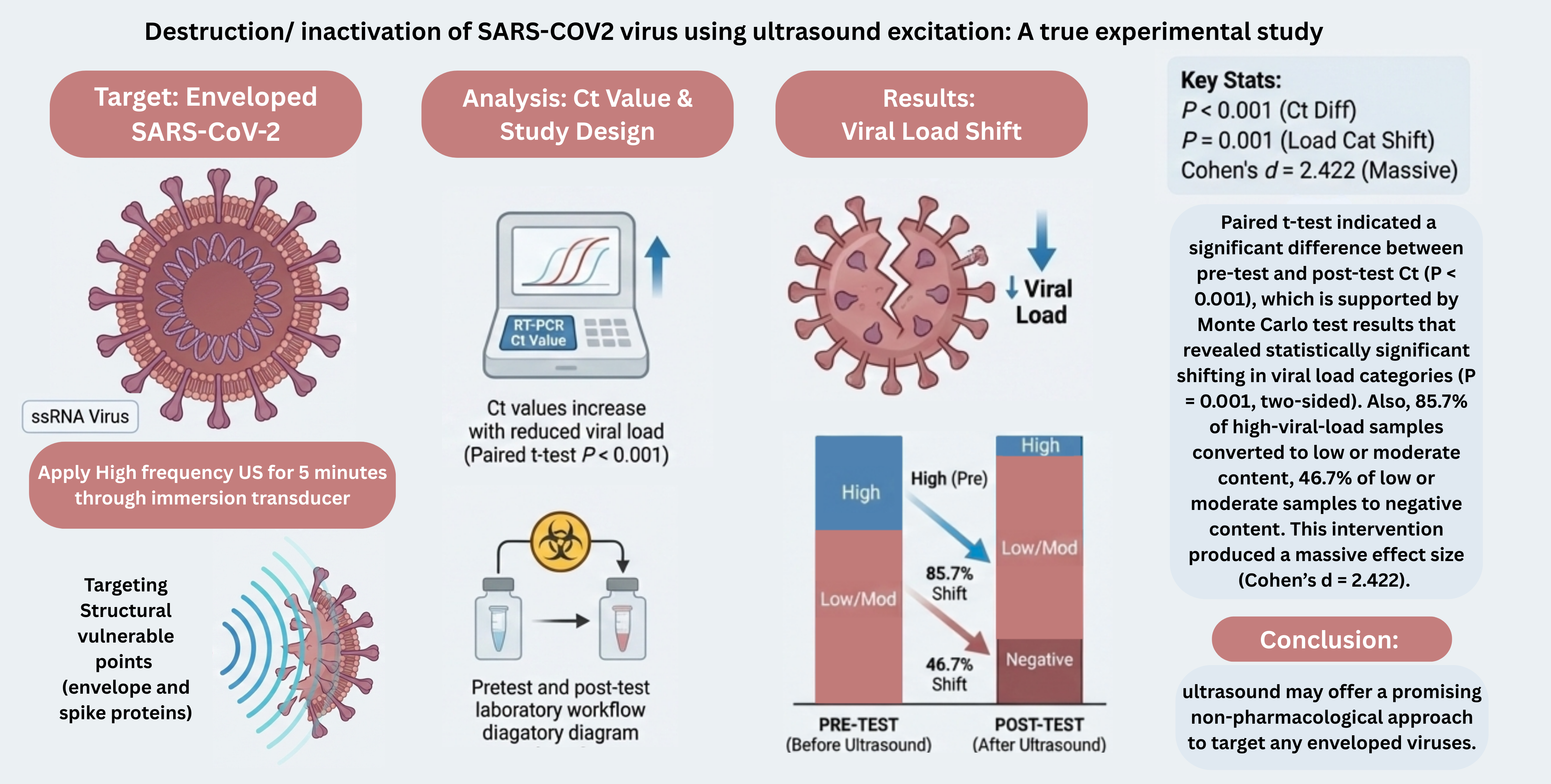

3.3. Changes In Viral Load Categories

It was found that 85.7% of patients with a high viral load in the pretest shifted to low / moderate viral load in the post-test. Additionally, 46.7% of patients with low/moderate viral load became negative in the post-test. The Monte Carlo test results indicated a statistically significant relationship between pre and post-test viral load categories, with a 2- sided P value of 0.001 (99% confidence interval).

Figure 3 illustrates distribution of SARS-CoV-2 real-time RT-PCR cycle threshold (Ct) categories before and after ultrasound exposure. Prior to ultrasound application, 68.2% of samples fell into the low-to-moderate viral load category and 31.8% into the high viral load category. Following ultrasound treatment, 31.8% of the samples became PCR-negative, 4.6% remained in the high viral load category, and 63.6% were classified as low-to-moderate viral load, indicating a marked shift toward reduced detectable viral RNA after ultrasound exposure.

Table 2.

Distribution of changes in viral load categories between pretest and post-test measurements.

Table 2.

Distribution of changes in viral load categories between pretest and post-test measurements.

| Posttest |

High viral load |

Low / Moderate load |

Negative |

Total |

| Pretest |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

| High viral load |

2 |

14.3 |

12 |

85.7 |

0 |

0 |

14 |

| Low Moderate viral load |

0 |

0 |

16 |

53.3 |

14 |

46.7 |

30 |

| Total |

2 |

4.5 |

28 |

63.6 |

14 |

31.8 |

44 |

| Test of Significance |

Monte Carlo p-value: 0.001 (2-sided) |

3.4. Paired-Sample T-Test Results

According to the

Table 3, there was significant statistical increase on the Ct values guest from the pretest (Mean ± SD = 28.13 ± 7.090) to the post-test (Mean ± SD = 34.21 ± 5.908). The t value of the mean difference is -16.065 (P < 0.001). In addition, the effect size (Cohen’s d) is -2.422.

4. Discussion

The current findings indicate that the Ct value of a liquid sample infected with SARS-CoV-2 treated with focused high-frequency ultrasound at 25 MHz has increased significantly, which suggests a decrease of amplifiable viral RNA. The degree of this effect was significant, with a large effect size, indicating that the changes were not only statistically significant but also biologically relevant. These results accept the main research hypothesis and suggest that optimal coupling of high-frequency ultrasound to a liquid environment might hinder the viral integrity and replication ability most probably via mechanical, rather than thermal or chemical mechanisms. The generated frequency-dependent focused experiment tool is promoted by the theoretical and computational models of Wierzbicki et al. [

12], who concluded that SARS-CoV-2 displays mechanical resonance properties because of its viscoelastic core–shell structure, including lipid envelope and spike protein assemblies. According to such models, if high acoustic pressure is supplied in a liquid medium, resonance modes are expected to induce envelope instability and spike failure within few minutes. Importantly, the current study satisfies critical physical requirements to evaluate this hypothesis: The transducer was directly immersed in the liquid viral medium to eliminate air–liquid impedance mismatch. This ensures true ultrasound propagation through the sample with minimal loss. The acoustic pressure was also determined (~107.5 kPa) as a function of intensity, medium properties, and transducer area. This promotes mechanistic interpretation (e.g., comparison with resonance thresholds predicted by Wierzbicki et al. [

12] modeling). The probe concentrates energy at a defined location (focus) in the sample. This creates locally high mechanical stress, unlike diffuse fields created by diagnostic ultrasound probes. Collectively, these conditions facilitate the effective transfer of mechanical energy to viral particles and inform a mechanistic explanation for the observed decrease in viral RNA load.

Recent experimental studies also support the idea that ultrasound can negatively influence the viability of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro, despite the different experimental setups and with different frequency domains. Veras et al. used commercial diagnostic ultrasound probes with different frequencies 3–12, 5–10, and 6–18 MHz that used to expose viral suspensions or infected culture media (applied externally through the container wall) for 30 min. The infectiveness of the virus was determined by TCID₅₀, and immunofluorescence staining for spike protein and dsRNA, demonstrating a frequency-dependent decrease in infectivity with the 5–10 MHz band that had reliable efficacy in comparing Wuhan, Delta, and Gamma strains. Critically, though, the investigators preserved the mechanical index under clinically regulated conditions (~0.3–0.5) without a noticeable increase in temperature consistent with a mechanical versus thermal influence. High-resolution SEM and AFM imaging further observed aberrant viral morphology e.g., envelopes and spike disruption.[

15] Despite the convergent conclusions, the methodological and physical contrasts between the two studies appear substantial and potentially justify the differences in effective frequency ranges and biological readouts.

Medical probes radiate short, broadband acoustic pulses that have multiple harmonic and sideband components, not a discrete frequency [

16], and viral suspensions are commonly exposed to these diffuse acoustic fields over long periods (≈30 minutes in Veras et al. study).[

2] Such long exposure may accounts for cumulative mechanical fatigue and indirect excitation of vulnerable vibrational modes, even when the nominal center frequency can be in the low-MHz range. In comparison, the current study utilized a narrowband focused immersion transducer at a specific frequency (25 MHz) directly coupled with the viral medium and delivered for only 5 minutes yet achieved a significant increase in Ct values and large effect size. This means that efficient acoustic coupling, frequency specificity and focal pressure concentration could offset shorter exposure times by providing mechanical energy to the viral particles directly. Therefore, the variations in effective frequencies and duration of exposure between the two studies are due to differences in acoustic bandwidth, energy localization, and coupling efficiency rather than competing resonance behaviors. Combined, these results further suggest that SARS-CoV-2 has frequency-dependent mechanical vulnerability, which may be compromised by broadband, low-intensity ultrasound (for long duration) or by focused, high-frequency ultrasonography (for short duration exposure) when acoustic delivery features are enhanced.

One other study examined viral inactivation by ultrasound at lower frequencies and higher intensities, in combination with chemical sensitizers such as methylene blue (MB). Lu et al. demonstrated with ultrasound (in low-mid-MHz (~1.8 MHz) at high acoustic intensities (0.63–2.16 W/cm²), especially when combined with MB, 10⁵–10⁷-fold reduction in viral titers, via mainly cavitation-driven and sonochemical pathways involving reactive oxygen species.[

17] This study consistently prove that the viral lipid envelope of the enveloped viruses not only show mechanical vulnerability but also chemical vulnerability.[

18,

19] Nonetheless, such approaches are clearly different from the current work, since they rely on chemical intermediates and cavitation, in contrast to our study that deliberately isolates pure acoustic–mechanical effects at high frequency, without use of sensitizers.

Conversely, a recent low-frequency survey with Ct rises at 40 kHz described using an air-coupled ultrasound setting, in which the transducers were placed about 10 cm away from liquid samples, not including any immersion or acoustic coupling. [

20] Physically, an acoustic-based design such as this prohibits a purposeful transfer of ultrasound energy to the liquid phase, especially at frequencies of MHz, due to the extreme attenuation and large acoustic impedance mismatch at the air–liquid interface.[

21] Effects, even at kilohertz, would not be considered to be due to resonance-driven phenomena, and probably to a type of indirect mechanical agitation or experimental artifact. Furthermore, the AFM was the only visualization of viral morphology before ultrasound exposure, offering no direct structural evidence of resonance-induced damage after exposure. These basic methodological limitations are limiting reasons for comparing with direct immersion-based, liquid-coupled ultrasound exposure in the current study.

Thus, the current findings indicate that ultrasound–virus interactions strongly depend on frequency, coupling conditions, transducer design, and energy delivery geometry, which has been previously reported in the literature. Here we build on this evidence, with a high-frequency (25 MHz) immersion ultrasound study showing that concentrated high frequency immersion ultrasound of this nature substantially decreases the viral RNA load, which provides additional support for resonance- or mechanically mediated disruption as a possible approach. Some limitations need to be acknowledged. Viral load reduction was also deduced by Ct shifts, not by direct infectivity assays or structural imaging, which does not determine the exact site or the mode of viral damage per se. Second, the experiment was performed in vitro and ignored the multidimensional role of biological fluids or host factors. However, the significant effect size and statistical robustness of these findings present a solid basis for future studies. Future research might directed to (i) confirm ultrasound induced viral destruction using high-resolution imaging modalities as AFM and SEM to study the topography and analyze the surface integrity of virus particles; (ii) generalize the effect of ultrasound on viral disruption by expanding the experiment on other clinically relevant enveloped viruses, as HIV; (iii) to further investigate the use of the method in more controlled extracorporeal conditions, such as blood or plasma circulation systems; and (iv) to assess the safety, efficacy, and biological relevance of ultrasound-based viral inactivation techniques in suitable animal models. Together, this work will contribute to a better validation of the results of the different ultrasound platforms and to move ultrasound towards an achievable non-pharmacological antiviral approach.

5. Conclusions

The current study demonstrating the potential use of ultrasound waves to significantly reduce viral load in COVID-19 positive samples, as suggested by increased Ct values. Although promising, these results need to be confirmed in larger studies and more direct measures of viral structural injury. Ultrasound may therefore be a useful tool in combatting enveloped viruses more effectively and may act as a complement to any arsenal we may already have against pathogenic viruses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization was carried out by H.A. Methodology was collaboratively by all authors. Software implementation, formal analysis, data curation, visualization, project administration, and preparation of the original draft were performed by H.A. Validation, investigation, and provision of resources were conducted collaboratively by all authors. Manuscript review and editing were completed by H.A. Supervision and funding acquisition were provided by A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The Kuwait Foundation for the Advancement of Sciences (KFAS), grant number P N 2 3 1 3 M N 1 7 6.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Permanent Committee for the Coordination of Medical and Health Research, Ministry of Health, Kuwait (Research number 1936/2022, approved on 9 February 2022).

Data Availability Statement

Research data were available with corresponding author and will be provided when reasonably requested. Public achievement of data is limited due to privacy/ ethical restrictions due to involvement of human driven biological samples.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Sallam Kouritem, Assistant Professor of Mechanical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Alexandria University, Egypt, for his valuable scientific consultation and technical guidance throughout the course of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AFM |

Atomic Force Microscope |

| COVID-19 |

Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| Ct |

Cycle Threshold |

| HIV |

Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| MHz |

Megahertz |

| MB |

Methylene Blue |

| RT-PCR |

Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| SARS-CoV-2 |

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

| SEM |

Scanning Electron Microscope |

| US |

Ultrasound |

| VTM |

viral Transport Medium |

| |

|

References

- Xiao, Y.; Sheng, Z.; Williams, SL; Taubenberger, JK. Two complete 1918 influenza A/H1N1 pandemic virus genomes characterized by next-generation sequencing using RNA isolated from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded autopsy lung tissue samples along with evidence of secondary bacterial co-infection. Mbio Available from. 2024, e0321823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J; Song, Q; Zhang, P; Deng, L; Gao, F; Deng, Y; et al. AntiviralDB: an expert-curated database of antiviral agents against human infectious diseases. mBio Available from. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrapu, S.; Kumar, R. Chronic hepatitis B: Prevent, diagnose, and treat before the point of no return. World J. Hepatol. 2024, 16, 1151–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nova, N.; Athni, T.S.; Childs, M.; Mandle, L.; Mordecai, E.A. Global Change and Emerging Infectious Diseases. Annu Rev Resour Economics 2022, 14, 333–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowman, M.C.; Archin, N.M.; Margolis, D.M. Pharmaceutical approaches to eradication of persistent HIV infection. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2009, 11, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooney, J.P.; Allison, C.C.; Preston, S.; Pellegrini, M. Therapeutic manipulation of host cell death pathways to facilitate clearance of persistent viral infections. J Leukoc Biol 2018, 103, 287–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, M.; Wills, M.R.; Sinclair, J. HCMV Antivirals and Strategies to Target the Latent Reservoir. Viruses 2021, 13, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyerowitz, E. A.; Li, Y. Review: The Landscape of Antiviral Therapy for COVID-19 in the Era of Widespread Population Immunity and Omicron-Lineage Viruses. Clin Infect Dis. 2024, 78, 908–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murashkina, S.; Budanova, Е. Modern Methods of Herpes Treatment: from Traditional Antiviral Therapy through Vaccines, and Genetic Engineering (review). Russ J Skin Venereal Dis. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzón, P.; Maity, S.; Roos, W.H. Physical Virology: From Virus Self-Assembly to Particle Mechanics. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews-nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology 2020, 12, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- França, Á.R.S.; Filho, J.F.S.D.; dos Santos, C.C.; Coimbra, L.D.; Marques, R.E.; Barbosa, L.R.S.; Santos-Oliveira, R.; Souza, P.F.N.; Alencar, L.M.R. Unraveling the Nanomechanical and Vibrational Properties of the Mayaro Virus. ACS omega 2024, 9, 48397–48404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wierzbicki, T.; Li, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, J. Effect of Receptors on the Resonant and Transient Harmonic Vibrations of Coronavirus. Journal of The Mechanics and Physics of Solids 2021, 150, 104369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kervalishvili, P.J. Vibrational Spectroscopy of Nanobiosystems and Concept of Resonance Therapy. Šromebi - Sak’art’velos tek’nikuri universiteti 2024, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadraeian, M.; Kabakova, I.V.; Zhou, J.; Jin, D. Virus Inactivation by Matching the Vibrational Resonance. Applied physics reviews 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veras, F.P.; Martins, R.B.; Arruda, E.; Cunha, F.Q.; Bruno, O.M. Ultrasound Treatment Inhibits SARS-CoV-2 in Vitro Infectivity. bioRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.; Hoff, L.; Eggen, T. Sources of 2 Nd Harmonic Generation in a Medical Ultrasound Probe. Internaltional Ultrasonics Symposium, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, N.; Tian, Y.; Wei, L.; Zhang, G.; Xie, C.; He, T.; Xu, Y.; Wang, G. Effect of Ultrasound with Methylene Blue as Sound Sensitive Agent on Virus Inactivation. Medicine in novel technology and devices 2022, 17, 100204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalenko, I.; Kholina, E.G.; Fedorov, V.; Khruschev, S.S.; Vasyuchenko, E.; Meerovich, G.; Strakhovskaya, M. Interaction of Methylene Blue with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Envelope Revealed by Molecular Modeling. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krasilnikov, M.S.; Denisov, V.Ya.; Korshun, V.A.; Ustinov, A.V.; Alferova, V.A. Membrane-Targeting Antivirals. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 7276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canbolat, O.; Canbolat, F.; Ergün, M.A.; Yiğit, S.; Bozdayı, G. Investigation of the Effect of Low-Power, Low-Frequency Ultrasound Application on SARS-COV-2. Türk biyokimya dergisi 2024, 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Dong, H.; Zhao, S.; Chen, M.; Fang, D. Wireless Acoustic Energy Harvesting through an Air-Water Metasurface with Dual Coupling Resonators. Physical review applied 2024, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).