1. Introduction

Avian immunosuppressive and neoplastic diseases, such as Marek’s disease (MD), avian leukosis (AL), reticuloendotheliosis (RE), and chicken infectious anemia (CIA), are major epidemics in chicken flocks characterized by lymphoid hyperplasia, tumour formation, and severe immunosuppression, leading to vaccine failures, secondary infections and substantial economic losses to the poultry industry worldwide [

1]. MD is caused by pathogenic Marek’s disease virus (MDV) and induces serious immune organ atrophy, neural damage, and lymphoproliferative tumours that ultimately cause a large number of deaths. Globally, the direct economic losses resulting from MD outbreaks are estimated annually at 1-2 billion US dollars [

2]. For decades, efficient control of MD has relied primarily on vaccination. However, the continuously expanded scale of poultry farming and the sustained high immune pressure imposed by long-term vaccination programs have led to a significant increase in MDV virulence [

3]. Some epidemic MDV strains, including the very virulent plus MDV (vv+MDV) and particularly the emerging hypervirulent variants of MDV (HV-MDV) [

4,

5,

6], have significantly evaded the protection conferred by classical MD vaccines and caused frequent outbreaks of MD all over the world, especially in Asia countries [

7], thereby posing a serious threat to the global poultry industry.

In addition to MDV, co-infections of avian leukosis virus (ALV), reticuloendotheliosis virus (REV), and even chicken infectious anemia virus (CIAV) further aggravate immunosuppression and tumourigenesis in chicken flocks, posing a major challenge to poultry health. To date, no commercial vaccine is available for the control of AL, and it completely relies on stringent biosecurity measures and continuous eradication programs in breeding stocks to minimize viral prevalence. For REV co-infection, it rarely occurs as a primary etiological event but can exacerbate secondary immunopathological conditions in affected flocks. Nevertheless, its overall epidemiological impact on modern poultry production remains relatively limited [

6]. However, for CIA, another major immunosuppressive disease caused by CIAV and typically affecting young chicks lacking maternal antibodies, it leads to lymphoid organ atrophy, aplastic anemia, and subcutaneous and muscular hemorrhages in hosts, displaying a high morbidity in infected flocks [

8]. Most seriously, CIAV infection usually undermines the protection efficacy induced by other poultry vaccines and predisposes birds to potential secondary infections caused by diverse pathogenic agents, thereby resulting in considerable indirect economic losses [

9].

CIAV belongs to the genus Gyrovirus within the family Anelloviridae [

10] and has a small circular single-stranded DNA genome of approximately 2.3 kb that encodes three overlapping open reading frames (ORFs), designated VP1, VP2, and VP3 [

11]. VP1, the sole capsid protein, is highly immunogenic and capable of eliciting protective neutralizing antibodies. VP2 acts as a multifunctional scaffolding protein with intrinsic phosphatase activity that facilitates the proper folding of VP1, thereby promoting the exposure of key antigenic epitopes and enhancing antibody recognition [

12,

13]. Moreover, VP2 has been reported to act as an apoptosis-inducing factor, suggesting a crucial role in CIAV-mediated cytopathogenicity [

14]. VP3, also known as apoptin, serves as a principal virulence determinant of CIAV [

15]. Both VP2 and VP3 are relatively conserved among CIAV isolates, whereas residues 139-151 of VP1 represent a hypervariable region that is closely associated with virulence and commonly used for molecular epidemiological and phylogenetic analysis [

16]. Since the first report in 1979 [

17], CIAV has spread globally to be one of the most common infectious diseases in poultry. China is the world’s largest poultry producer that sustains more than 16 billion birds annually, including a population exceeding 1 billion laying hens. Since 2019, large-scale outbreaks of immunosuppressive and neoplastic diseases have re-emerged across the commercial poultry industry in China [

4,

5,

6]. Our previous work has revealed that the prevalence of HV-MDV, partially co-infected with ALV and/or REV, was the predominant causative agent responsible for the frequent outbreaks of tumour cases in vaccinated chicken flocks during 2020-2021 [

4,

5,

6]. However, since 2022, numerous clinical cases with tumour-bearing birds and potentially associated with CIAV infection have been reported by field veterinarians, resulting in substantial economic losses in poultry farms. To elucidate the current epidemiological landscape of CIAV and MDV co-infections in chickens, we have conducted a systematic investigation on clinical suspected tumour cases across 72 affected poultry farms distributed in central China during 2020-2023. Furthermore, genetic and phylogenetic analysis were performed based on the viral genomes and VP1 genes of currently circulating CIAV viruses to characterize the molecular evolution and provide a scientific foundation for future effective prevention and control of the disease.

2. Materials and Methods

1.1. Sample Collection

The liver and spleen samples were collected from 211 chickens of different breeds and ages exhibiting suspected tumour lesions across 72 commercial poultry farms located in Henan, Shandong, Anhui and Shanxi Provinces in central China. Samples from 30 cases obtained during 2020-2021 were derived from our previous investigations [

6], while additional specimens from 42 cases collected during 2022-2023 were newly included in this study (sampling sites shown in

Figure 1). Detailed background information on the recently collected samples and clinical cases is summarized in

Table S1.

1.2. DNA Extraction

Approximately 10 mg of each liver or spleen samples were suspended in 500 μL of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) in a 1.5-mL Eppendorf tube containing two autoclaved stainless-steel beads. The tissues were homogenized at 50 Hz for 5 min at 4°C using an automated tissue grinder (SCIENTZ-48L; Xinzhi Biologicals, China), followed by three freeze-thaw cycles at -20°C for 30 min each. The homogenates were then centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 5 min, and the resulting supernatants were collected and stored at -80°C until further processing. Genomic DNA was extracted using the TIANamp Genomic DNA Kit (Tiangen Biotech, China) according to the manufacturer's protocols. DNA concentrations were determined, standardized to 300 ng/μl and stored at -20℃ until use.

1.3. PCR Amplification of MDV

The meq gene, specific to MDV-1, was amplified using the primer pair MDV-meq-F/R [

6], with primer sequences listed in

Table S2. DNA extracted from 77 samples collected across 42 farms during 2022-2023 was selected for initial screening. Each of 20 μL PCR reaction mixture contained 10 μL 2× EasyTaq PCR SuperMix (+dye; TransGen Biotech, China), 8 μL of ddH₂O, 0.5 μL of each primer (10 μM), and 1 μL of template DNA (100 ng). The thermal cycling program was set as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 58°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Amplified products were separated by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel and visualized using a gel documentation system under UV illumination.

1.4. PCR Amplification of CIAV

Three pairs of CIAV-specific primers covering the entire viral genome [

18] were synthesized by Sangong Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China), and the primer sequences are listed in

Table S2. The most efficient primer pair, CIAV-2F/2R, was used for the first round of screening of all the clinical samples collected during 2020-2023. Each of 20 μL PCR reaction contained 10 μL of 2× EasyTaq PCR SuperMix (+dye; TransGen Biotech, China), 8 μL of ddH₂O, 0.5 μL of each primer (10 μM), and 1 μL of template DNA (300 ng). Cycling parameters were set as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min, with a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Amplified products were separated by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized using a gel documentation system under UV illumination.

1.5. Cloning and Sequencing of CIAV Genome

Twenty CIAV-positive liver samples collected from different poultry farms were selected for full-genome amplification using the three primer pairs listed in

Table S2 [

18]. PCR amplifications for VP1, VP2, and VP3 genes were performed as previously described, yielding amplicons of 842 bp, 990 bp, and 737 bp respectively. The PCR products were verified by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, purified using a gel extraction kit (Tiangen Biotechnology, China), and cloned into the pMD18-T vector (TaKaRa Biotechnology, Japan). The recombinant plasmids were then transformed into Escherichia coli DH5α. Positive clones were identified and subjected to Sanger sequencing (General Biosystems, China). The resulting sequences were validated using BLAST and assembled into complete genomes with DNASTAR software (DNASTAR Inc., Madison, WI, USA). All newly obtained CIAV genome sequences were deposited in GenBank database, and accession numbers are provided in

Table S3.

1.6. Phylogenetic Analysis

The whole genome sequences of 91 CIAV reference strains were collected from GenBank (

Table S3). The complete viral genome and VP1 genes of 111 CIAV isolates, including 20 viruses newly obtained in this study, were separately aligned and analyzed using MEGA v11 [

19]. Phylogenetic trees were separately constructed using the neighbour-joining method with 1,000 bootstrap replicates and further refined in iTOL v6 [

20].

1.7. Sequence Analysis of the VP1 Gene and UTRs of CIAV Isolates

The homology of VP1 amino acid (aa) sequences between 20 newly obtained CIAV isolates and 91 reference strains was analyzed using DNASTAR MegAlign (DNASTAR Inc., Madison, WI, USA). Key mutations in the VP1 hypervariable region (aa 139-151) were examined for potential associations with pathogenicity among epidemic CIAV Chinese strains. Additionally, the untranslated regions (UTRs) of 20 newly obtained CIAV isolates were analyzed and characterized to evaluate possible regulatory variations.

1.8. Whole Gene Recombination Analysis of CIAV

Recombination events in the viral genomes of 20 newly obtained CIAV isolates and 91 reference strains were analyzed using RDP5 software [

21], which utilizes seven algorithms including RDP, GENECONV, BootScan, MaxChi, Chimaera, SiScan, and 3Seq. Events supported by at least five algorithms were considered as significant.

3. Results

2.1. CIAV Infection in MD Tumour-Bearing Chicken Flocks During 2020-2021

To evaluate the prevalence of CIAV and co-infections in poultry farms with tumour-bearing cases between 2020 and 2021, liver samples collected from 30 chicken flocks across central China [

6] were retrospectively screened for CIAV infection. As shown in

Table 1, the overall positive rate of CIAV infection in individual birds was 40.0% (58/145), and for detected chicken flocks, co-infection of CIAV+MDV reached to a positive rate of 66.7% (20/30). Regionally, as listed in

Table 2, Henan province (n=26 flocks) exhibited individual- and flock-level positive rates of 36.8% (46/125) and 65.4% (17/26) respectively, whereas Shandong province (n=4 flocks) showed correspondingly higher rates of 60.0% (12/20) and 75.0% (3/4). Interestedly, CIAV co-infection was confirmed in 66.7% (20/30) of detected flocks, while none of CIAV mono-infection (0/30) was observed in these MD tumour-bearing chicken flocks. For these 30 cases, based on the collected background data [

6], the onset ages of disease distributing for MDV and CIAV infections were both concentrated to 60-120 days, with a median age of 90 days (

Figure 2 A and B, blue bars).

2.2. Prevalence and Infections of MDV and CIAV in Poultry Farms During 2022-2023

To investigate the current infection dynamics of CIAV and MDV in poultry farms with tumour outbreaks, a comprehensive molecular survey was conducted on 42 diseased flocks collected from Henan, Shandong, and Shanxi provinces in central China during 2022-2023 (

Figure 1). Regionally, as shown in

Table 2, Henan province (n=37 flocks) showed CIAV positive rate of 47.4% (27/57) at the individual level and 54.1% (20/37) at the flock level, while in Shandong province (n=4 flocks), the flock-level rate reached to 75.0% (3/4). The overall CIAV positive rate was 45.5% (30/66) at the individual level and 54.8% (23/42) at the flock level, whereas the corresponding MDV positive rate was 54.5% (42/77) and 45.2% (19/42), respectively (

Table 3). However, the mono-infections of CIAV or MDV were detected in 26.2% (11/42) and 16.7% (7/42) of flocks, respectively, whereas co-infections involving both viruses occurred in 28.6% (12/42) of flocks. Unexpectedly, based on the collected data of the onset age of disease in layers, as shown in

Table S1 and

Figure 2 (A and B, red bars), the onset days of MD and CIA cases with tumours mainly ranged from 60-260 days, with a promoted median age of 180 days.

2.3. Whole-Genome Sequencing and Recombination Analysis of CIAV Isolates

A total of 20 strongly CIAV-positive samples confirmed by PCR amplification, as demonstrated in

Figure 3, were subjected to full-genome amplification using three primer pairs covering the entire viral genome (

Table S2). Successfully, the amplified products were cloned, sequenced, and assembled into 20 complete circular genomes, with GenBank Acc. Nos. listed in

Table S3. All isolates possessed the canonical 2,298-bp genome without insertions or deletions. Pairwise nucleotide identities among the 20 isolates ranged from 96.6% (e.g. CIAV-HNLK2 vs CIAV-HNLY1-1) to 99.7% (e.g. CIAV-HNYY1 vs CIAV-SDCX2). Compared to the vaccine strains Cux-1 and Del-Ros, the highest sequence identities were observed in CIAV-HNAY (98.0% and 98.6%, respectively), whereas CIAV-HNLY1-1 exhibited the lowest identities (96.6% and 96.9%, respectively). When compared with the virulent field strain YN04, nucleotide identities ranged from 96.7% (CIAV-HNLY1-1) to 99.5% (CIAV-HNPY), indicating a close evolutionary relationship between the new isolates and previous circulating virulent lineages. The recombination analysis performed in RDP5 using seven algorithms had not found any significant recombination events in the newly sequenced genomes of 20 CIAV isolates.

2.4. Phylogenetic Analysis of Current Circulating CIAV Viruses

Whole-genome and VP1 gene sequences from the 20 new CIAV isolates, together with 91 reference sequences listed in

Table S3, were aligned and analyzed for phylogenetic reconstruction. Based on the whole-genome phylogeny, all strains were resolved into four distinct clades A, B, C and D (

Figure 4A). Clade A comprised two isolates exclusively from Australia, whereas clade B contained three early Chinese strains. Clade C represented a dominant global lineage that included isolates from Asia, Europe, North and South America, and Africa. It was further subdivided into two subclades: C1 (predominantly Asian isolates-88.5% (46/52) from China, along with South Korea, India, Vietnam, and Japan) and C2 (vaccine strains Cux-1, Del-Ros, and 26P4, together with diverse global isolates). Clade D comprised geographically diverse isolates from multiple continents, including Asia, Europe, Africa, the Americas, and Australia. Among the newly obtained Chinese CIAV isolates, 17 clustered within clade C1, two within C2, and one within B, while none were assigned to clades A or D. The VP1 gene-based phylogenetic tree exhibited an almost identical topology to the whole-genome phylogenetic tree (

Figure 4 B), confirming consistent clustering patterns across both datasets. Overall, the current prevalent Chinese CIAV isolates clustered primarily in clade C1, forming a geographically distinct lineage that exhibited spatial clustering but no evident temporal differentiation.

2.5. Mutations of Amino Acid Residues in VP1 Proteins of Circulating CIAV Viruses

Alignment of the 450-amino-acid VP1 proteins from 20 new CIAV isolates and 16 reference strains with known virulence have revealed 30 amino acid substitutions, corresponding to an overall variability of 6.7% (

Table 4). Notably, residue 394, a principal molecular determinant of CIAV virulence, was found to be consistently encoded glutamine (Q) in all 20 isolates, whereas for histidine (H), indicative of attenuated virulence, was not detected in any of the new isolates. Further analysis of the hypervariable region (amino acids 139-151) has revealed distinct sequence heterogeneity among these isolates. Four isolates (CIAV-HNZC1, CIAV-HNLY1-1, CIAV-HNXY, CIAV-HNXY5) possessed glutamine (Q) at both positions 139 and 144, whereas the remaining isolates encoded lysine (K) and glutamic acid (E) at these respective positions.

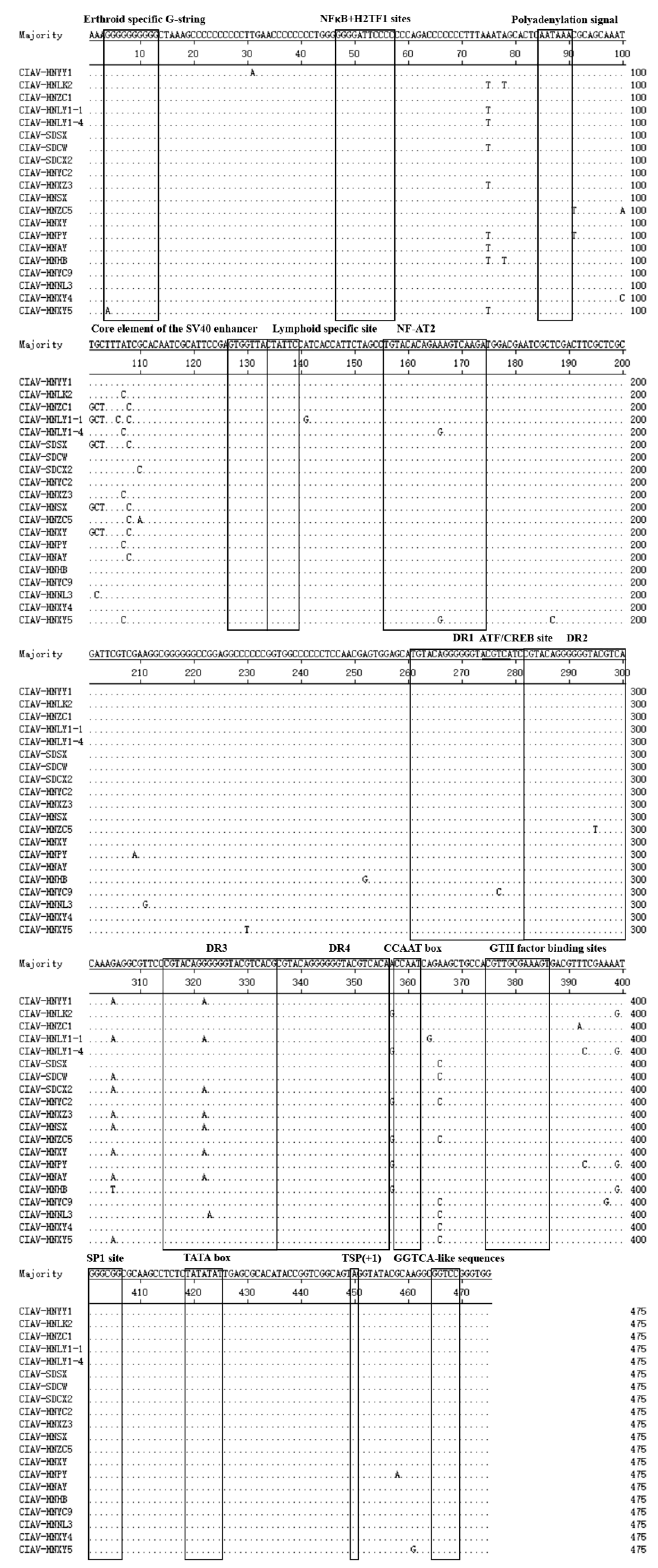

2.6. Sequence Analysis of the UTRs of Circulating CIAV Isolates

Alignment of the UTR sequences of 20 new CIAV isolates has revealed that the nucleotide identities ranged from 96.6% to 100%, with the lowest similarity observed between CIAV-HNLY1-1 and CIAV-HNPY (96.6%), and a complete identity between CIAV-HNSX and CIAV-HNXY (100%). Comparative analysis of the conserved regulatory motifs has demonstrated nucleotide substitutions within the NF-AT2, ATF/CREB, and DR3 elements, whereas no variation was observed in the lymphoid-specific site, SV40 enhancer core element, polyadenylation signal, NFκB+H2TF1 sites, and erythroid-specific G-string (

Figure 5). Four direct repeat (DR) regions were consistently detected within the UTRs, among which DR3 exhibited substitutions in 40% (8/20) of isolates. Additionally, single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were also observed in both NF-AT2 and ATF/CREB regulatory motifs (

Figure 5).

4. Discussion

CIAV is a major immunosuppressive pathogen in poultry and has achieved worldwide dissemination since it was first isolated and identified in Japan in 1979 [

17]. The virus causes severe immunosuppression in young chicks by impairing both humoral and cellular immune responses. Furthermore, co-infection with other avian immunosuppressive and neoplastic pathogens such as MDV, ALV, and REV, can further synergistically exacerbate disease severity, leading to markedly increased morbidity and mortality in flocks [

6,

22,

23]. Our previous work [

6] has demonstrated that recent outbreaks of avian neoplastic diseases in China are primarily driven by epidemic HV-MDV viruses, partially co-infected with ALV and/or REV. However, the potential role of CIAV and its co-infection under these cases remains insufficiently understood. To clarify this question, an overall epidemiological investigation was conducted across 72 poultry farms in central China from 2020 to 2023, focusing on CIAV prevalence in tumour-suspected cases. Surprisingly, our data revealed a highly flock-level CIAV positive rate reached to 59.7% (43/72), markedly exceeding the previously reported infection rates [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29] and indicating an escalating prevalence of CIAV in recent years. In the years 2020-2021, co-infection of MDV+CIAV was dominant in 66.7% (20/30) flocks, but mono-infections of MDV or CIAV were only observed in 30.0% (9/30) and 0% flocks, respectively. It means that all CIAV infection during this period occurred almost exclusively as a secondary infection. By contrast, data obtained from 2022-2023 has revealed a significant epidemiological shift, as the co-infections of MDV+CIAV declined to 28.6% (12/42), while CIAV mono-infections significantly increased to 26.2% (11/42). This epidemiological trend indicates that CIAV, previously defined primarily to secondary infection, has recently emerged as an independent pathogen capable of inducing serious clinical diseases.

When compared with the previously reported MDV and CIAV co-infection rates of 11.1% and 4.69% [

24,

30], the substantially higher values detected in this study underscore the escalating severity of both secondary and primary infections of CIAV in contemporary poultry production. Furthermore, previous investigations have demonstrated that CIAV infection reduces the protective efficacy of the CVI988/Rispens vaccine against MDV, thereby enhancing the virulence and pathogenic potential of both vMDV and vvMDV strains [

31,

32]. Over the past decade, immunosuppressive and neoplastic diseases, such as MD, have continuously affected commercial poultry populations despite widespread vaccination efforts [

6,

23,

33]. The present findings indicate that co-infection of MDV+CIAV represents a major etiological factor in the recurrent outbreaks in vaccinated chicken flocks. Such co-infections likely exacerbate immune dysfunction and promote tumourigenesis, highlighting an urgent need to incorporate CIAV surveillance and control into integrated immunization and biosecurity measures. In recent work, a recombinant MDV vaccine strain rMS-∆Meq expressing CIAV VP1 and VP2, showed promise in protecting against CIAV [

34], suggesting that bivalent vaccines could effectively control the co-infected immunosuppressive agents.

Phylogenetic analyses of both whole viral genomes and VP1 genes from 20 newly obtained CIAV isolates and 91 reference strains produced consistent topologies, resolving four major clades A, B, C and D). Clade C represented the most widely distributed lineage and was further subdivided into subclades C1 and C2. Subclade C1 consisted almost exclusively of Asian strains, with 88.5% (46/52) of the isolates originating in China. Seventeen newly identified isolates such as CIAV-HNXZ3, CIAV-HNPY and CIAV-HNAY were clustered tightly within C1 along with the highly pathogenic YN04, indicating an ongoing circulation among contemporary Chinese field strains. In contrast, subclade C2 encompassed strains from geographically diverse regions (e.g., the United States, Iran, Germany, New Zealand, India, Malaysia, and Italy) with only a few representatives from China. Two novel isolates (CIAV-HNZC1 and CIAV-HNXY) were positioned within subclade C2 but remained phylogenetically distant from the classical vaccine strains 26P4, Cux-1, and Del-Ros that also reside in this subclade. This distant clustering pattern suggests that these viruses may represent foreign-introduced lineages that have undergone a local adaptive evolution. No novel isolate was assigned to clade D, which contained a mixture of global strains from multiple continents in the world. Notably, one isolate (CIAV-HNLY1-1) was clustered within clade B along with a previously reported canine-derived CIAV strain [

35], suggesting a potential risk of cross-species transmission. Overall, Chinese CIAV isolates predominantly clustered into a distinct lineage within subclade C1, demonstrating geographical clustering and regional genetic specificity. Analysis of the whole viral genomes had not revealed evidence for recombination among the 20 newly CIAV isolates, indicating a relative genetic stability of the currently circulating viruses. Nevertheless, the presence of isolates in clades C2 and B, including lineages potentially of interspecies origin, underscores the increasing epidemiological and genetic complexity of CIAV. These findings highlight the importance of continuous molecular surveillance, phylogenetic monitoring, and early-warning systems to track the emergence and spread of novel CIAV variants.

The VP1 protein, the sole structural protein of CIAV, exhibits the highest sequence variability among viral genes, underscoring the significance of amino acid substitution analysis in understanding viral evolution and pathogenicity [

16]. Previous studies have identified glutamine (Q) at position 394 of VP1 as a critical molecular determinant of high pathogenicity in CIAV isolates [

35,

36]. Consistently, all 20 new isolates analyzed in this study contained Q at this position, indicating a potentially pathogenic capacity. Furthermore, amino acid residues at positions 139 and 144 have been shown to affect viral replication and propagation efficiency in host cells, with strains harboring Q at both positions exhibiting markedly reduced replication rates [

16]. Four double-Q variants such as CIAV-HNZC1, CIAV-HNLY1-1, CIAV-HNXY, and CIAV-HNXY5 have been presently identified, but the impact on replication kinetics and pathogenicity warrants further experimental evaluation. In addition, nucleotide polymorphisms were identified within the DR3 and ATF/CREB regulatory motifs in the UTRs of several CIAV isolates. The functional implications of these mutations remain unclear, which may affect viral transcriptional regulation and/or replication efficiency but needs to be further investigated.

In summary, this study comprehensively investigated CIAV+MDV co-infections in tumour-bearing chicken flocks across central China during 2020-2023, together with a molecular evolutionary analysis of circulating CIAV viruses. Our data have further confirmed that the epidemic HV-MDV viruses, in combination with CIAV co-infections, are primarily responsible for the resurgence of immunosuppressive and neoplastic diseases in vaccinated poultry populations. Notably, the significant increases in both CIAV co-infection and mono-infection compared with previous reports have highlighted the emerging challenges for future control of the disease. Most circulating Chinese CIAV isolates are clustered in subclade C1 and form a unique regional genotype, whereas the presence of a few isolates in subclade C2 and clade B suggests increasing genetic and epidemiological diversification. Amino acid profiling of VP1 identified molecular signatures associated with high pathogenic potential, consistent with previous literature on CIAV virulence in mono-infections and supported by recent field observations from clinical veterinarians. These findings characterize the current molecular epidemiological landscape of CIAV in tumour-bearing chicken flocks in China and provide an important basis for the development of targeted diagnostic and control measures against this re-emerging pathogen.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

https://www.mdpi.com/article/doi/s1, Table S1: Background information of suspected clinical cases of avian neoplastic diseases collected from poultry farms in central China during 2022-2023. Table S2: Primers used for PCR amplification of MDV or CIAV genes in this study. Table S3: Background information of the newly obtained and reference CIAV isolates.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L. and Z.-H.Y. ; methodology, F.H. and B.S.; software, F.H. and B.S.; validation, L.-P.Z., M.T., S.-G.W. and W.-K.Z.; formal analysis, F.H. and B.S.; investigation, F.H., G.-X.L., Y.-X.Z., Z.Y., Z.-F.P. and Q.L.; resources, J.L., Z.-H.Y., G.-X.L., Y.-X.Z. and Z.Y.; data curation, F.H. and B.S.; writing—original draft preparation, F.H. and B.S.; writing—review and editing, J.L., S.-G.W. and Y.-X.Y.; visualization, F.H. and B.S.; supervision, J.L. and Z.-H.Y.; project administration, J.L.; funding acquisition, J.L. and Z.-H.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant numbers U21A20260 & 32473015, the Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province, grant numbers 232300421009 & 252300421279, the Key R&D and Promotion Project of Henan Province, grant number 252102111027, the Central Government-Guided Local Science and Technology Development Fund Project of Henan Province, grant number 2025ZYYD05, the Autonomous innovation project of Henan Academy of Agricultural Sciences, grant number 2025ZC154, the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), grant numbers BBS/E/I/00007038, BBS/E/PI/23NB0003 & BBS/OS/NW/000007. The APC was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China and Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully thank Prof. Venugopal Nair (AOV group, The Pirbright Institute, UK) for reading through the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Swayne, D.E.; Boulianne, M.; Logue, C.M.; McDougald, L.R.; Nair, V.; Suarez, D.L. Diseases of Poultry; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 550-586.

- Kennedy, D.A.; Cairns, C.; Jones, M.J.; Bell, A.S.; Salathé, R.M.; Baigent, S.J.; Nair, V.K.; Dunn, P.A.; Read, A.F. Industry-Wide Surveillance of Marek's Disease Virus on Commercial Poultry Farms. Avian Dis 2017, 61, 153-164. [CrossRef]

- Witter, R.L. Increased virulence of Marek's disease virus field isolates. Avian Dis 1997, 41, 149-163.

- Liu, J.L.; Teng, M.; Zheng, L.P.; Zhu, F.X.; Ma, S.X.; Li, L.Y.; Zhang, Z.H.; Chai, S.J.; Yao, Y.; Luo, J. Emerging Hypervirulent Marek's Disease Virus Variants Significantly Overcome Protection Conferred by Commercial Vaccines. Viruses 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Teng, M.; Zheng, L.P.; Li, H.Z.; Ma, S.M.; Zhu, Z.J.; Chai, S.J.; Yao, Y.; Nair, V.; Zhang, G.P.; Luo, J. Pathogenicity and Pathotype Analysis of Henan Isolates of Marek's Disease Virus Reveal Long-Term Circulation of Highly Virulent MDV Variant in China. Viruses 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.P.; Teng, M.; Li, G.X.; Zhang, W.K.; Wang, W.D.; Liu, J.L.; Li, L.Y.; Yao, Y.; Nair, V.; Luo, J. Current Epidemiology and Co-Infections of Avian Immunosuppressive and Neoplastic Diseases in Chicken Flocks in Central China. Viruses 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Zeb, J.; Hussain, S.; Aziz, M.U.; Circella, E.; Casalino, G.; Camarda, A.; Yang, G.; Buchon, N.; Sparagano, O. A Review on the Marek's Disease Outbreak and Its Virulence-Related meq Genovariation in Asia between 2011 and 2021. Animals (Basel) 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Adair, B.M. Immunopathogenesis of chicken anemia virus infection. Dev Comp Immunol 2000, 24, 247-255. [CrossRef]

- Balamurugan, V.; Kataria, J.M. Economically important non-oncogenic immunosuppressive viral diseases of chicken--current status. Vet Res Commun 2006, 30, 541-566. [CrossRef]

- International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). Current ICTV Taxonomy Release. Available online: https://ictv.global/taxonomy/taxondetails?taxnode_id=19930761 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Noteborn, M.H.; de Boer, G.F.; van Roozelaar, D.J.; Karreman, C.; Kranenburg, O.; Vos, J.G.; Jeurissen, S.H.; Hoeben, R.C.; Zantema, A.; Koch, G.; et al. Characterization of cloned chicken anemia virus DNA that contains all elements for the infectious replication cycle. J Virol 1991, 65, 3131-3139. [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.A.; Jackson, D.C.; Crabb, B.S.; Browning, G.F. Chicken anemia virus VP2 is a novel dual specificity protein phosphatase. J Biol Chem 2002, 277, 39566-39573. [CrossRef]

- Noteborn, M.H.; Verschueren, C.A.; Koch, G.; Van der Eb, A.J. Simultaneous expression of recombinant baculovirus-encoded chicken anaemia virus (CAV) proteins VP1 and VP2 is required for formation of the CAV-specific neutralizing epitope. J Gen Virol 1998, 79 ( Pt 12), 3073-3077. [CrossRef]

- Kaffashi, A.; Pagel, C.N.; Noormohammadi, A.H.; Browning, G.F. Evidence of apoptosis induced by viral protein 2 of chicken anaemia virus. Arch Virol 2015, 160, 2557-2563. [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Liang, Y.; Teodoro, J.G. The Role of Apoptin in Chicken Anemia Virus Replication. Pathogens 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Renshaw, R.W.; Soiné, C.; Weinkle, T.; O'Connell, P.H.; Ohashi, K.; Watson, S.; Lucio, B.; Harrington, S.; Schat, K.A. A hypervariable region in VP1 of chicken infectious anemia virus mediates rate of spread and cell tropism in tissue culture. J Virol 1996, 70, 8872-8878. [CrossRef]

- Yuasa, N.; Taniguchi, T.; Yoshida, I. Isolation and some characteristics of an agent inducing anemia in chicks. Avian diseases 1979, 366-385.

- Wang, X.W.; Feng, J.; Jin, J.X.; Zhu, X.J.; Sun, A.J.; Liu, H.Y.; Wang, J.J.; Wang, R.; Yang, X.; Chen, L.; et al. Molecular Epidemiology and Pathogenic Characterization of Novel Chicken Infectious Anemia Viruses in Henan Province of China. Front Vet Sci 2022, 9, 871826. [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol Biol Evol 2021, 38, 3022-3027. [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res 2024, 52, W78-w82. [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.P.; Varsani, A.; Roumagnac, P.; Botha, G.; Maslamoney, S.; Schwab, T.; Kelz, Z.; Kumar, V.; Murrell, B. RDP5: a computer program for analyzing recombination in, and removing signals of recombination from, nucleotide sequence datasets. Virus Evol 2021, 7, veaa087. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Lin, L.; Shi, M.; Li, H.; Gu, Z.; Li, M.; Gao, Y.; Teng, H.; Mo, M.; Wei, T.; Wei, P. Vertical transmission of ALV from ALV-J positive parents caused severe immunosuppression and significantly reduced marek's disease vaccine efficacy in three-yellow chickens. Vet Microbiol 2020, 244, 108683. [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Li, M.; Wang, P.; Wang, W.; Li, H.; Gao, Y.; Lin, L.; Huang, T.; Wei, P. An outbreak in three-yellow chickens with clinical tumors of high mortality caused by the coinfection of reticuloendotheliosis virus and Marek's disease virus: a speculated reticuloendotheliosis virus contamination plays an important role in the case. Poult Sci 2021, 100, 19-25. [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, X.; Ji, J.; Yao, L.; Kan, Y.; Xie, Q.; Bi, Y. Molecular Characteristics of Chicken Infectious Anemia Virus in Central and Eastern China from 2020 to 2022. Animals (Basel) 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Deng, X.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, Z.; Xie, L.; Luo, S.; Fan, Q.; Zeng, T.; Huang, J.; Wang, S. Molecular characterization of chicken anemia virus in Guangxi Province, southern China, from 2018 to 2020. J Vet Sci 2022, 23, e63. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Yin, M.; Zhao, P.; Guo, L.; Wang, Y. Genomic Characterization of Chicken Anemia Virus in Broilers in Shandong Province, China, 2020-2021. Front Vet Sci 2022, 9, 816860. [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.; Huang, Y.; Wang, L.; Luo, J.; Yan, N.; Zhang, L.; Huang, H.; Zhou, J.; Li, Z.; Xu, C. Genomic Sequence and Pathogenicity of the Chicken Anemia Virus Isolated From Chicken in Yunnan Province, China. Front Vet Sci 2022, 9, 860134. [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Wang, Z.; Lei, X.; Lu, J.; Yan, Z.; Qin, J.; Chen, F.; Xie, Q.; Lin, W. Epidemiology, molecular characterization, and recombination analysis of chicken anemia virus in Guangdong province, China. Arch Virol 2020, 165, 1409-1417. [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Tuo, T.; Gao, X.; Han, C.; Yan, N.; Liu, A.; Gao, H.; Gao, Y.; Cui, H.; Liu, C.; et al. Molecular epidemiology of chicken anaemia virus in sick chickens in China from 2014 to 2015. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0210696. [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Zhong, Q.; Jin, W.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Peng, D. Epidemiological Study of the Co-infection of Immunosuppressive Poultry Pathogens in Tissue Samples of Chickens in Jiangsu Province, China from 2016 to 2022. Pakistan Veterinary Journal 2024, 44.

- Zhang, Y.; Cui, N.; Han, N.; Wu, J.; Cui, Z.; Su, S. Depression of Vaccinal Immunity to Marek's Disease by Infection with Chicken Infectious Anemia Virus. Front Microbiol 2017, 8, 1863. [CrossRef]

- Miles, A.M.; Reddy, S.M.; Morgan, R.W. Coinfection of specific-pathogen-free chickens with Marek's disease virus (MDV) and chicken infectious anemia virus: effect of MDV pathotype. Avian Dis 2001, 45, 9-18.

- Wannaratana, S.; Prakairungnamthip, D.; Tunterak, W.; Charoenvisal, N.; Limpavithayakul, K.; Areeraksakul, P.; Sasipreeyajan, J.; Thontiravong, A. Pathogenicity and transmissibility of Marek's disease virus isolated from chickens in Thailand. Poult Sci 2025, 104, 105519. [CrossRef]

- Ge, C.; Lu, H.; Han, J.; Sun, G.; Li, S.; Lan, X.; Liu, Y.; Yu, M.; Hu, X.; Hu, M.; et al. Recombinant Marek's disease virus expressing VP1 and VP2 proteins provides robust immune protection against chicken infectious anemia virus. Front Microbiol 2024, 15, 1515415. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fang, L.; Cui, S.; Fu, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Cui, Z.; Chang, S.; Shi, W.; Zhao, P. Genomic Characterization of Recent Chicken Anemia Virus Isolates in China. Front Microbiol 2017, 8, 401. [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, S.; Imada, T.; Kaji, N.; Mase, M.; Tsukamoto, K.; Tanimura, N.; Yuasa, N. Identification of a genetic determinant of pathogenicity in chicken anaemia virus. J Gen Virol 2001, 82, 1233-1238. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).