Introduction

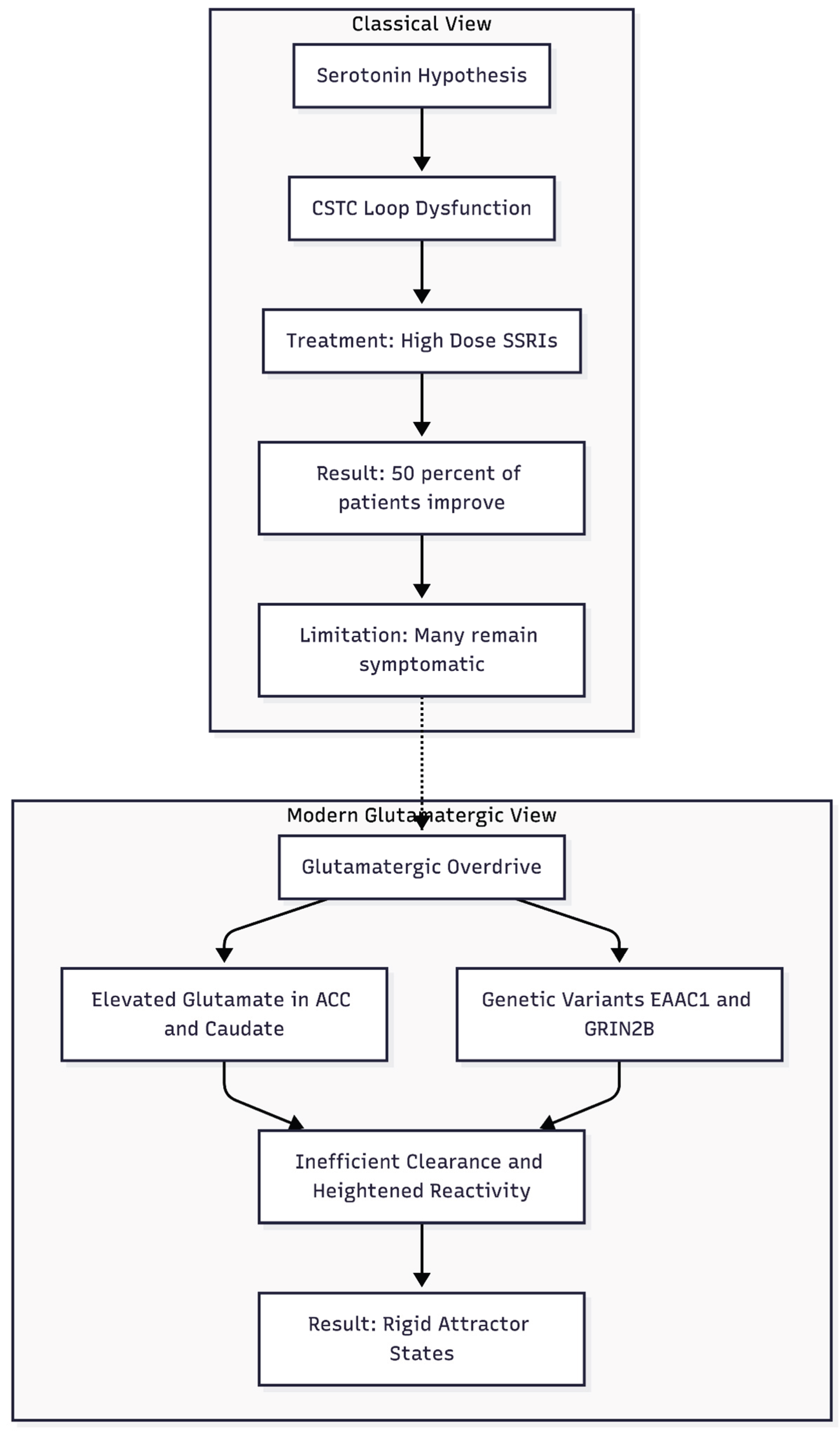

From Serotonin to Synapses: Why the Classical Model Proved Incomplete

For much of the late-twentieth century obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) was framed almost exclusively as a disturbance of serotonin within the cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical (CSTC) loop (

Figure 1). That view emerged from imaging work showing orbitofrontal hyper-metabolism and, more pragmatically, from the observation that high-dose selective serotonin-re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) reduce Yale-Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale scores in approximately one half of patients [

1]. Yet the model never fully explained why a large minority remain symptomatic after two or more adequate SSRI courses, even when antipsychotics are added [

2]. Nor could it account for the curious fact that symptom intensity often fluctuates with circadian arousal, hormonal shifts, or acute stress—contexts known to modulate glutamate far more than serotonin. As treatment-resistance accumulated in clinics, interest naturally shifted toward the neural mechanisms that sculpt synaptic strength rather than those that merely adjust transmitter tone.

Glutamatergic Overdrive in the CSTC Circuit

Proton-magnetic resonance spectroscopy and cerebrospinal-fluid studies have repeatedly documented elevated glutamate or Glx (glutamate + glutamine) in the anterior cingulate cortex and caudate of adults and children with OCD, with levels often predicting clinical severity [

3,

4]. Parallel genetic work has identified functional variants in the neuronal glutamate transporter EAAC1/SLC1A1 as well as in NMDA-receptor subunits such as GRIN2B [

5]. Together these findings suggest that inefficient clearance or heightened receptor reactivity allows excitatory drive to linger, biasing CSTC micro-circuits toward persistent high-frequency firing.

Rodent data give the hypothesis mechanistic depth. Sapap3-knockout mice lack a postsynaptic scaffold protein required for the normal anchoring of NMDA and AMPA receptors. The mutants display exuberant striatal dendritic spines, compulsive self-grooming, and anxiety-like avoidance—behaviours that abate when NMDA signalling is toned down [

6]. Such work portrays OCD less as a chemically starved brain than as one caught in rigid attractor states created by maladaptive long-term potentiation.

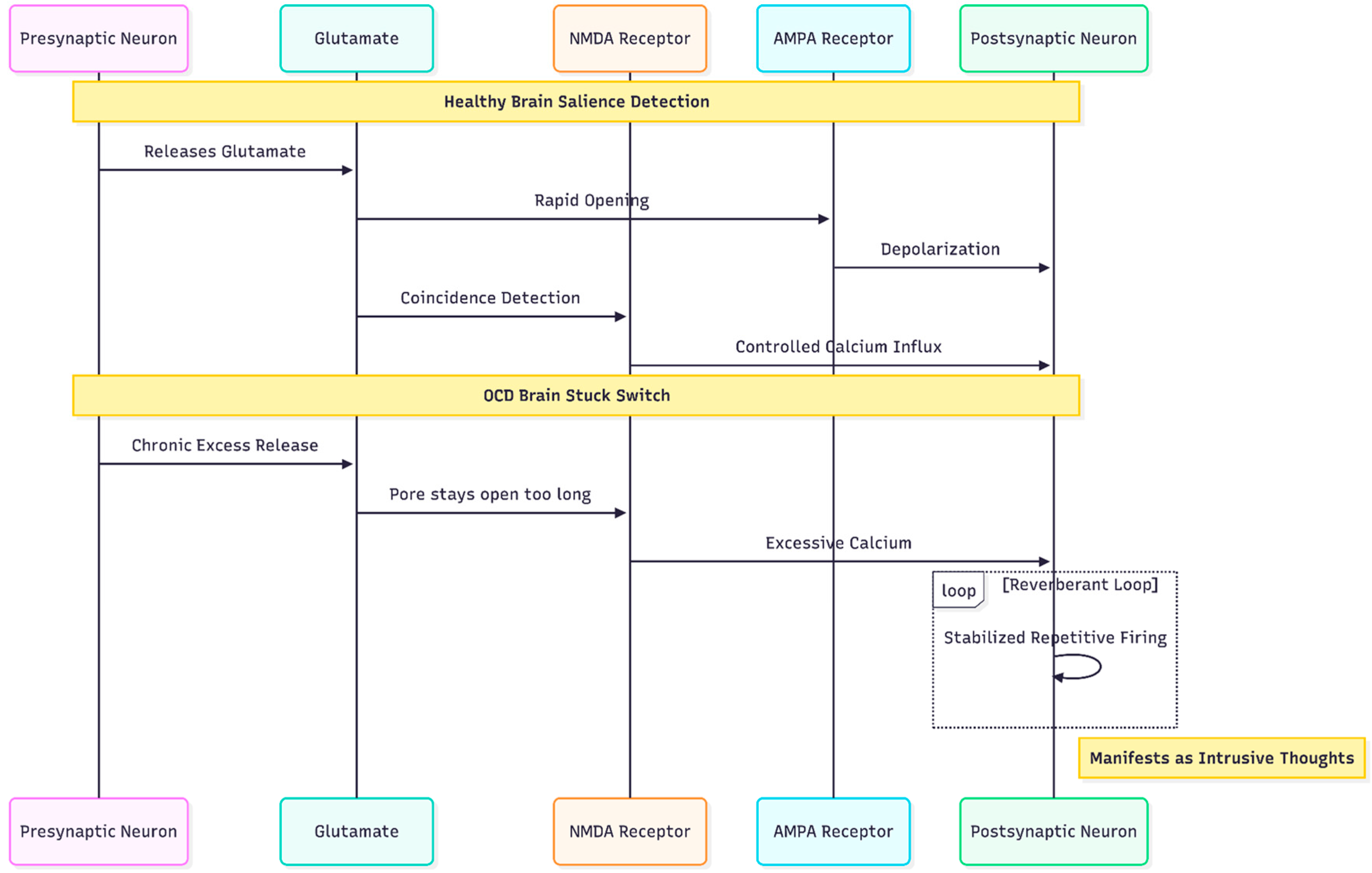

NMDA, AMPA, and the "Stuck Switch" in OCD

Within the glutamatergic system the NMDA receptor occupies a unique position. Because it requires both ligand binding and postsynaptic depolarisation, it acts as a coincidence detector, admitting calcium only when pre- and post-synaptic elements fire together. In the healthy brain that property allows NMDA channels to encode salience. In OCD, however, chronically elevated glutamate appears to keep NMDA pores open too long on striatal medium spiny neurons, stabilising reverberant loops that patients experience as intrusive thoughts and ritual urges [

4].

The puzzle is further complicated by the AMPA receptor, whose rapid opening normally provides the depolarising pre-condition for NMDA activation. If AMPA trafficking is blunted—an effect seen in stress models—or if AMPA throughput is excessive relative to NMDA current, the delicate timing that underlies synaptic pruning and consolidation unravels. The result is either under-learning of adaptive cues or over-learning of threat cues, both hallmarks of OCD phenomenology (

Figure 2).

Ketamine as Proof-of-Concept for Rapid Circuit Resetting

Few clinical observations have shaken psychopharmacology as thoroughly as the discovery that a single sub-anaesthetic dose of ketamine can lift severe depression and, in smaller studies, markedly reduce compulsive symptoms within hours [

7]. The cascade begins with a transient block at the NR2B-enriched NMDA receptors located on pre-frontal interneurons, an action that paradoxically releases a pulse of glutamate [

8]. That surge lands on AMPA receptors, evokes a calcium inflow, triggers brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) release, and activates the mammalian-target-of-rapamycin (mTOR) pathway. Within twenty-four hours new dendritic spines appear in medial pre-frontal cortex and hippocampus, correlating with the duration of symptom relief [

9]. When AMPA receptors are pharmacologically blocked with NBQX, both mood and anti-obsessional benefits vanish [

10], underscoring that NMDA antagonism is the spark, but AMPA throughput is the flame.

Despite this elegant biology, ketamine's clinical uptake is hindered by cost, dissociation, and the need for monitored infusions. Intranasal esketamine solves some problems but remains expensive and delivers only the first half of the cascade; it blocks NMDA receptors yet does little to amplify AMPA currents, leading to a slower onset and shorter durability than intravenous ketamine [

11].

Design Logic of the Cheung Glutamatergic Regimen

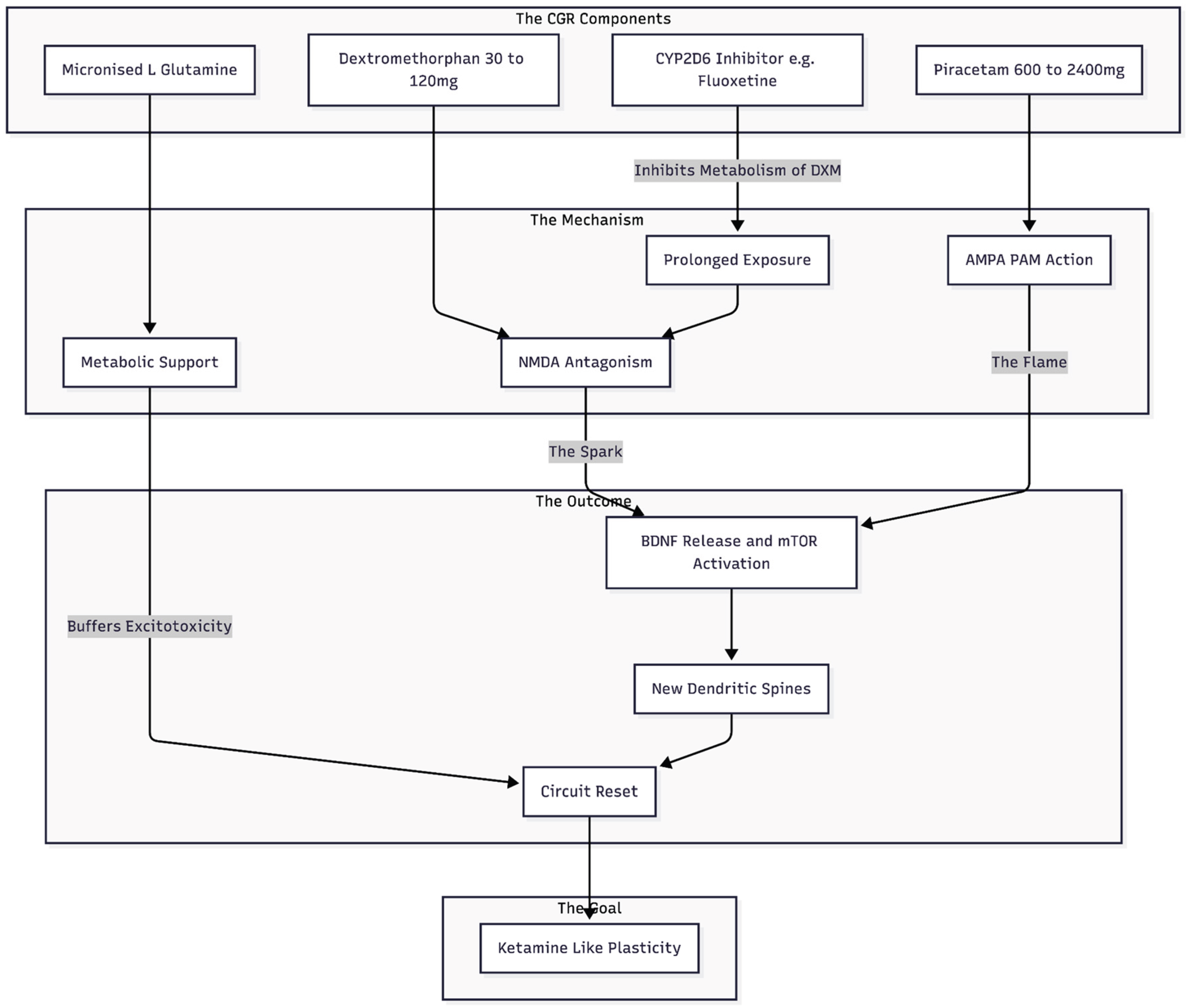

In 2025, Cheung proposed a four-component, fully oral protocol—now referred to as the Cheung Glutamatergic Regimen (CGR)—designed to reproduce ketamine's plasticity sequence at supermarket prices [

12]. The elements are deliberately simple:

The design obeys the same chronological logic that underlies ketamine therapy: NMDA inhibition first, AMPA facilitation second, then metabolic support. Because all agents are generic, oral, and well characterised, the regimen can be customised easily—DXM raised or lowered according to dissociative tolerance; the inhibitor switched from fluoxetine to paroxetine in ultrarapid metabolisers; piracetam titrated to cognitive comfort; glutamine increased during periods of inflammatory stress.

Figure 3.

The CGR Architecture: A four-part oral regimen designed to mimic ketamine. DXM provides the initial NMDA block (protected by a CYP2D6 inhibitor), Piracetam amplifies the resulting signal at AMPA receptors, and Glutamine provides the necessary fuel and protection for synaptic repair.

Figure 3.

The CGR Architecture: A four-part oral regimen designed to mimic ketamine. DXM provides the initial NMDA block (protected by a CYP2D6 inhibitor), Piracetam amplifies the resulting signal at AMPA receptors, and Glutamine provides the necessary fuel and protection for synaptic repair.

Clinical Experience to Date

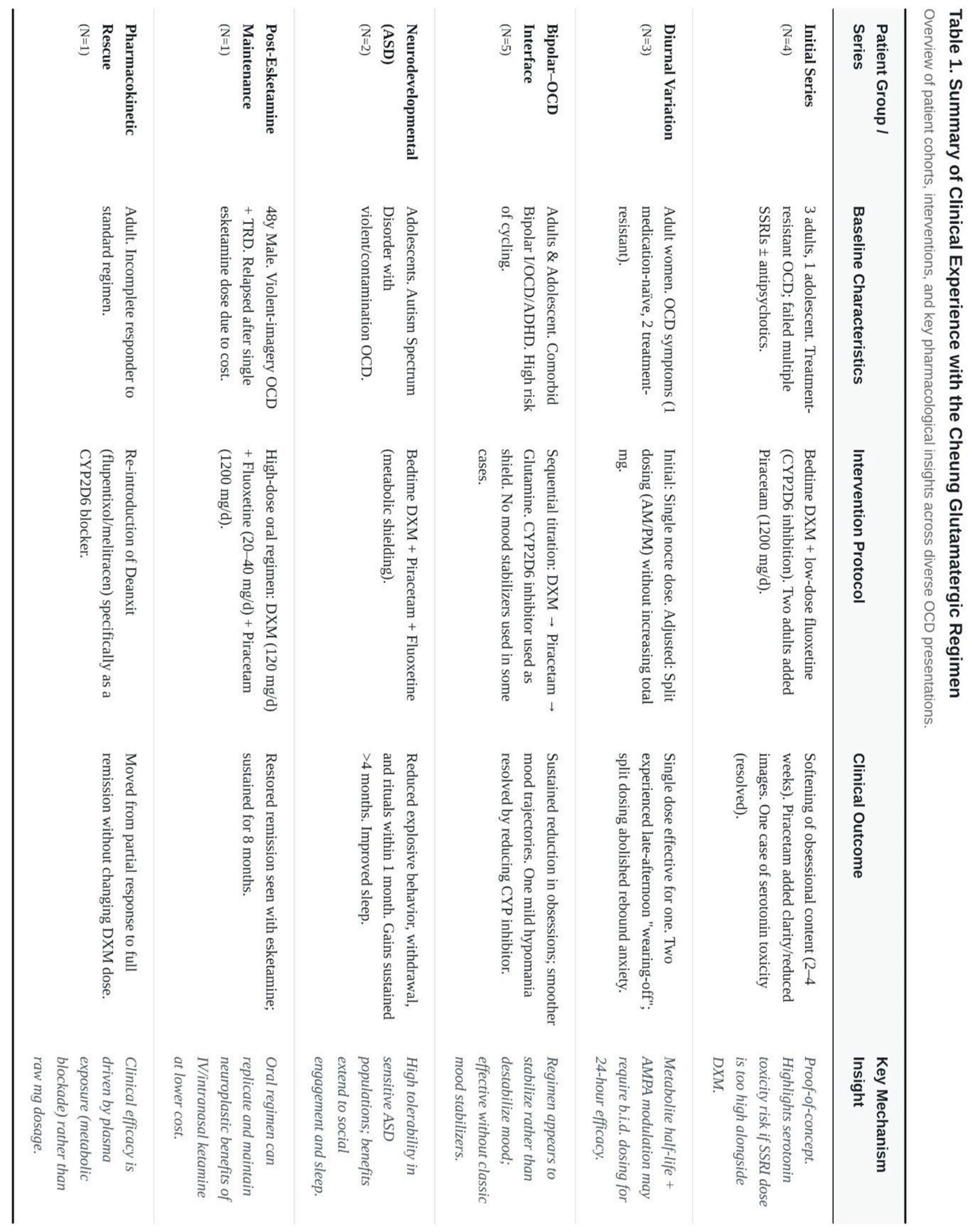

(Table 1 as a summary of all findings.)

Initial Four-Patient Series

The earliest description involved four consecutive patients: three adults and an adolescent, all of whom had failed multiple selective-serotonin-re-uptake inhibitor (SSRI) trials and, in most cases, antipsychotic augmentation [

19]. Bedtime DXM, held in circulation by low-dose fluoxetine, produced a perceptible softening of obsessional content within two to four weeks. Two of the adults later added piracetam 1 200 mg per day and reported an extra lift—clearer thought flow, fewer intrusive images, and easier delay of rituals—without fresh side-effects. One woman experienced brief tachycardia after her SSRI was doubled; symptoms resolved when the fluoxetine dose was reduced, illustrating the serotonin-toxicity risk that shadows any combination of DXM and strong CYP2D6 blockade.

Diurnal "Wearing-Off" and Split Dosing

A follow-up report turned to dose timing [

20]. Three adult women began treatment with a single nocte capsule containing DXM 30–45 mg plus piracetam 600–1 200 mg. One, who was otherwise medication-naïve, went into durable remission on that simple schedule. The other two felt well on waking but noticed anxiety and checking urges creeping back by late afternoon. Moving half the dose to the morning abolished the rebound without raising the daily milligram total. The observation implies that, for some metabolisers, the active metabolite dextrorphan plus the AMPA "boost" of piracetam cannot maintain a full twenty-four-hour effect—a practical detail rather than a flaw of mechanism.

Bipolar–OCD Presentations

Several write-ups explored patients sitting on the bipolar–OCD frontier, a notoriously hard-to-treat territory where standard antidepressants may provoke hypomania or rapid cycling.

Adult Series – In a three-case sequence, low-dose DXM was introduced first, piracetam second, and glutamine only when residual fatigue persisted [

21]. All three showed sustained cuts in obsession severity and smoother mood trajectories. One patient did tip into a mild, short-lived hypomania; reducing the CYP2D6 inhibitor, while keeping piracetam steady, calmed the episode without erasing the anti-obsessional benefit.

Mixed Comorbidity – A single-case note documented the same approach in a man with bipolar I disorder, OCD, and ADHD [

22]. Here, the regimen replaced both lithium and high-dose antipsychotics, yet mood swings settled and rituals faded over a six-month follow-up.

Adolescent Course – In a 17-year-old boarding-school student, a bedtime stack of fluoxetine 10 mg, DXM 30 mg, and piracetam 600 mg brought intrusive suicidal images and mood lability under control within weeks [

23]. A small afternoon "top-up" was later added to match a consistent 3 p.m. dip. Notably, no classic mood stabiliser was ever started.

Neurodevelopmental Contexts

Two extended case narratives focused on autistic teenagers with violent or contamination-driven OCD [

24,

25]. In both, bedtime DXM plus piracetam, supported by fluoxetine for metabolic shielding, reduced explosive behaviour, social withdrawal, and compulsive rituals within the first month and held gains for at least four months. Parents reported better sleep hygiene and revived extracurricular interests—outcomes that carry added weight in the context of autism-spectrum disorder (ASD), where many psychotropics are poorly tolerated.

Post-Esketamine Maintenance

One of the most illustrative stories concerns a 48-year-old man who responded dramatically to a single intranasal esketamine session but could not afford maintenance dosing [

25]. Over two years, unrelenting violent-imagery OCD accrued on top of treatment-resistant depression. The oral Cheung regimen—DXM 120 mg/day, fluoxetine 20–40 mg/day, piracetam 1 200 mg/day—restored the initial esketamine-level remission and has kept it for eight months at one-tenth the cost of clinic-based ketamine.

Pharmacokinetic Tweaks and CYP2D6 "Rescue"

Another vignette underlines the need for reliable CYP2D6 inhibition [

26]. An incomplete responder on DXM + piracetam alone moved into full remission only after Deanxit (flupentixol/melitracen), itself a moderate CYP2D6 blocker, was re-introduced. Nothing else in the regimen changed, strengthening the argument that plasma exposure to DXM—not simply the mg dose swallowed—controls clinical outcome.

Dosing and Scheduling Strategies for the Cheung Glutamatergic Regimen in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Rationale for a Flexible Schedule

The Cheung Glutamatergic Regimen (CGR) was never conceived as a fixed "one-size-fits-all" protocol. Instead, it grew out of day-to-day adjustments made in outpatient practice while clinicians watched how obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) symptoms waxed and waned across the twenty-four-hour cycle. Two practical facts shape those adjustments. First, each pillar of the stack—dextromethorphan (DXM), a CYP2D6 inhibitor, piracetam, and, in selected cases, L-glutamine—follows its own pharmacokinetic curve. Second, intrusive thoughts and ritual urgency often show diurnal peaks, most commonly in the late afternoon when mental energy dips and environmental cues thin out. A schedule that ignores either fact risks early "wearing-off" or, at the other extreme, needless side-effects from over-dosing.

The experience now spans more than fifty individual cases drawn from seven linked case reports and series [

12,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Although sample sizes remain small, internal consistency is high enough to outline pragmatic rules that clinicians can test in their own settings. The paragraphs below distil those rules while preserving the exact dose ranges, timing tricks, and safety caveats already in print.

Starting the Regimen: Bedtime as Default

1. Entry dose of dextromethorphan.

Most adults and older adolescents begin at DXM 30 mg per day, delivered as two 15-mg tablets taken together after the evening meal. The justification is two-fold. First, 30 mg is well below antitussive "plateau doses" associated with dissociation, so daytime impairment is unlikely. Second, cortical glutamate turnover and slow-wave sleep–linked synaptic housekeeping both rise at night; aligning the NMDA block with this natural plasticity window appears to enhance tolerability and, in a subset of patients, accelerates response [

20].

2. Immediate pharmacokinetic support.

Because extensive CYP2D6 metabolisers can clear DXM in a few hours, a modest CYP2D6 inhibitor is started on the same night. In routine practice three options dominate:

Fluoxetine 10–40 mg nightly

Paroxetine 10–20 mg nightly

Deanxit ® (flupentixol 0.5 mg + melitracen 10 mg) one tablet nightly

Fluoxetine 10 mg usually suffices; ultrarapid metabolisers sometimes need 20–40 mg or a switch to paroxetine [

21]. Deanxit, used chiefly when an anxiolytic lift is desired, offers milder CYP2D6 inhibition but can still double DXM exposure [

19].

3. Piracetam could be withheld at baseline.

In treatment-naïve or mildly resistant OCD, piracetam is often deferred for two weeks, allowing DXM kinetics to stabilise and any serotonergic side-effects to surface first. When added, the opening dose is 600 mg once nightly with DXM, mirroring the entry pattern that brought a full remission in a newly diagnosed nurse within seventeen days [

20].

When Bedtime-Only Works

Roughly one-third of individuals—typically younger patients with shorter illness duration—achieve sustained remission on nothing more than the bedtime stack: DXM 30–45 mg, fluoxetine 10–20 mg, and piracetam 600 mg [

20,

23]. The common denominators in this subgroup are:

Low prior drug exposure. These patients have not cycled through multiple high-dose SSRIs or antipsychotics that might blunt plasticity.

Stable mornings with predictable sleep-wake cycles. They drift into slow-wave sleep easily, so a nocte surge in cortical glutamate dovetails with endogenous pruning.

Minimal afternoon triggers. Work or study schedules provide structure until evening, buffering against diurnal rebound.

For them, once-nightly dosing offers obvious advantages: fewer daytime pills, lower peak-trough swings, and reduced risk of serotonin toxicity because the SSRI is confined to night.

Recognising and Fixing Late-Day Rebound

A larger fraction—perhaps half in published series—feel well each morning yet notice obsessive drift, somatic tension, or checking pressure between 16:00 and 18:00. Miss F's "what-if wave" after 17:00 [

20] and the adolescent boy's midday slump in Canada [

24] typify the pattern. Plasma studies were not run, but pharmacokinetic logic is persuasive: the half-life of piracetam (~5 h in older adults, shorter in youth) and the decline of active DXM/dextrorphan levels around 12 h post-dose leave a therapeutic gap.

Split-dosing algorithm

Keep total daily dose unchanged at first. Move half the DXM and piracetam to 07:00–08:00 while leaving the CYP2D6 blocker at bedtime.

Re-assess. In Miss F, PHQ-9 fell from 5 → 2 and GAD-7 from 16 → 9 once the regimen shifted to DXM 30 mg + piracetam 600 mg twice daily [

20].

Escalate only if rebound persists. For entrenched afternoon spikes, total daily DXM may rise to 60–90 mg and piracetam to 1 200 mg in two divided doses. Case 2 in the bipolar-OCD series stabilised at exactly that level [

21].

Safety note. Fluoxetine stays nocte to limit serotonergic overlap; if morning activation emerges, clinicians favour trimming DXM rather than adding a daylight SSRI dose.

High-Dose or Thrice-Daily Schedules in Severe Resistance

Treatment-exhausted cases—long-standing OCD with comorbid bipolarity or psychotic features—sometimes require higher trough levels. Case 3 in the bipolar-OCD paper illustrates a ceiling strategy: DXM 60 mg twice daily, piracetam 600 mg twice, plus Deanxit for kinetics [

21]. The escalation unfolded over ten weeks:

Baseline: DXM 30 mg BD produced partial lift.

Phase-in: Dose climbed by 15 mg every two weeks; mood activation was checked by reducing fluoxetine duration rather than piracetam.

Consolidation: At 120 mg/day DXM the patient still scored PHQ-9 24 until piracetam entered; remission followed within six weeks.

Thrice-daily schedules are rare but documented. The 31-year-old man with violent imagery tolerated DXM 15 mg four times daily (total 120 mg) before a morning-evening split was deemed simpler [

19]. With doses this high, monitoring for tachycardia or tremor is mandatory; one serotonin-toxicity scare appeared only after fluoxetine rose to 20 mg alongside DXM 60 mg [

19]. Cutting the SSRI in half resolved symptoms inside 48 h.

Special Populations

1. Bipolar-OCD overlap

In bipolar spectra, every prescriber fears a switch. The accumulated case work suggests three guard-rails:

Most switches resolved inside a week with that tactic, supporting the idea that NMDA antagonism, not AMPA modulation, drives early activation.

2. Adolescents with ASD or ADHD

Both Miss L (20 y) and the 15-year-old autistic pianist [

23] responded to 45 mg DXM + 1 200 mg piracetam given exclusively at bedtime. Younger brains show brisker plasticity; bedtime-only suffices and avoids daytime sedation. Parents must, however, watch for transient tremor—mild effects reported in the adolescent series.

3. Older adults

The 68-year-old hypochondriacal case reached remission on DXM 30 mg + piracetam 600 mg nightly, aided by bupropion's CYP2D6 block [

26]. Age-slowed clearance argues against aggressive titration. Morning heaviness, if it appears, usually reflects co-sedatives; trimming mirtazapine or lemborexant lifted fatigue without eroding OCD gains in that patient.

Adverse Reactions Observed to Date

The Cheung Glutamatergic Regimen (CGR) rests on medicines that have circulated for decades—dextromethorphan, fluoxetine or another CYP2D6 inhibitor, the nootropic piracetam, and, in selected cases, dietary L-glutamine. Individually, each compound enjoys a wide therapeutic margin; the novelty lies in administering them together, at low to moderate doses, to tilt cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical circuitry from NMDA- to AMPA-dominant signalling. Predictably, the combination introduces interaction risks that do not surface when the agents are used in isolation. Across the seven case series currently in the public domain [

12,

16,

19,

20,

21,

22], the side-effect picture has been reassuring but not negligible.

Autonomic arousal. The most frequent untoward effect is a short-lived rise in heart rate or a vague "inner tremor." Incidence hovers around one in ten patients, clustering within the first two weeks after an SSRI increment on top of an established DXM dose. The pattern matches a mild, pre-syndromal serotonin-toxicity state: sympathetic drive increases, yet altered mental status and clonus are absent. In the index series of four treatment-resistant OCD cases, tachycardia resolved within forty-eight hours when fluoxetine was stepped back from 20 mg to 10 mg while DXM 60 mg was held steady [

19]. No intravenous cyproheptadine or hospitalisation was required, underscoring that early dose correction is usually sufficient.

Tremor and jitteriness. Fine postural tremor, typically in the fingers, appears in roughly 15 % of patients. It is dose-related, worsens with caffeine, and fades after a week or two without specific treatment. Reducing the evening DXM fraction by 15 mg or shifting piracetam from morning to bedtime often quiets the symptom [

20].

Mood activation in bipolar spectra. In mixed mood-OCD presentations, the CGR has both alleviated depression and, occasionally, stirred hypomanic sparks. Cheung [

21] describes two brief activations: one after rapid up-titration of fluoxetine to 40 mg in a patient already on DXM 60 mg; another after introducing bupropion as a daytime CYP2D6 inhibitor. Both flares subsided when the NMDA component—or the kinetic booster—was trimmed, while piracetam and mood stabilisers were left intact. Importantly, no episode escalated to full mania or required inpatient care, but the experience argues for starting SSRI blockers at the low end (fluoxetine 10 mg or Deanxit ½–1 tablet) and titrating only when obsessive content persists.

Insomnia versus somnolence. DXM itself is neither a pronounced stimulant nor sedative at antitussive doses, yet timing matters. Administered before breakfast, it can extend sleep latency in sensitive individuals; when taken after supper it occasionally deepens early-night slow-wave sleep to the point of morning "grogginess." The remedy is pragmatic—swap morning dosing for noon, or trim concurrent sedatives such as mirtazapine, lemborexant or clonazepam [

26]. In the 68-year-old hypochondriacal case, halving lemborexant to 1.25 mg alongside a reduction of mirtazapine from 45 mg to 15 mg erased next-day lethargy without sacrificing the newly consolidated sleep window.

Methodological and Conceptual Limitations

The evidence base remains strictly naturalistic. All published observations originate from one metropolitan clinic; no randomisation, blinding or comparator arm has yet been attempted. Symptom tracking leans on PHQ-9 and GAD-7 because they are quick to administer in private practice; Y-BOCS data, though ideal, are sporadic. Similarly, hypomania is diagnosed based on clinical impression rather than formal Young-Mania scores. This is similar to how psychiatry works in the real world, but it makes meta-analysis harder and leaves room for expectancy bias.

Concomitant medications cloud attribution. Patients retained mood stabilisers, antipsychotics, benzodiazepines or hypnotics, adjusted independently of CGR. Although temporal associations—onset of benefit within two to four weeks of DXM introduction; relapse within days of stopping the glutamatergic agents—are compelling [

22], definitive causality awaits controlled withdrawal-rechallenge designs.

Duration of follow-up rarely exceeds nine months. Ketamine literature shows that tolerance or tachyphylaxis can appear with chronic NMDA blockade; whether a similar plateau awaits long-term CGR users is unknown. Likewise, the neurocognitive impact of years-long piracetam exposure remains uncharted in psychiatric samples.

Finally, the regimen operates on the premise that an NMDA-triggered glutamate burst, funnelled through AMPA, resets maladaptive synapses. Magnetic-resonance spectroscopy or ^11C-UCB-J PET has not yet been employed to confirm synaptic-density gains after oral DXM + piracetam. Without such mechanistic corroboration, the explanatory model, though persuasive, remains provisional.

Conclusions

Early reports present the CGR as an inexpensive, oral, and remarkably fast route to quelling treatment-resistant OCD, even when it cohabits with bipolarity or neurodevelopmental disorders. The side-effect burden, while modest, clusters around predictable pharmacodynamic junctures—serotonergic overlap, rapid NMDA up-titration, and high piracetam peaks. Most events are mild, reversible, and manageable through dose adjustment rather than discontinuation.

The limitations are equally clear. Evidence stems from uncontrolled series, formal OCD metrics are sporadic, and neurobiological validation is pending. Randomised, double-blind trials that stratify by CYP2D6 genotype, incorporate Y-BOCS and Mania scales, and extend observation beyond one year are now warranted. Parallel MRS or PET imaging could verify whether synaptic-density gains accompany clinical change, clinching the mechanistic argument.

In the meantime, clinicians intrigued by the regimen should proceed with cautious optimism—embracing its flexibility, respecting its interaction risks, and documenting outcomes rigorously. If larger trials confirm current impressions, the CGR may open an urgently needed middle road between serotonin-only pharmacology and resource-intensive ketamine infusion programmes.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no competing interests. The Cheung Glutamatergic Regimen described in this review was proposed and reported by the author in prior publications, but no financial or other conflicts arise from this work.

References

- Hirschtritt, M. E., Bloch, M. H., Mathews, C. A. (2017). Obsessive-compulsive disorder: Advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA, 317(13), 1358–1367.

- Dold, M., Aigner, M., Lanzenberger, R., et al. (2015). Antipsychotic augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: An update meta-analysis of double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 18(9), pyv047. [CrossRef]

- Karthik, S., Sharma, L. P., Narayanaswamy, J. C. (2020). Investigating the role of glutamate in obsessive-compulsive disorder: Current perspectives. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 16, 1003–1013. [CrossRef]

- Pittenger, C., Bloch, M. H., Williams, K. (2011). Glutamate abnormalities in obsessive compulsive disorder: Neurobiology, pathophysiology, and treatment. Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 132(3), 314–332. [CrossRef]

- Alonso, P., Gratacós, M., Segalàs, C., et al. (2012). Association between the NMDA glutamate receptor GRIN2B gene and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience, 37(4), 273–281. [CrossRef]

- Welch, J. M., Lu, J., Rodriguiz, R. M., et al. (2007). Cortico-striatal synaptic defects and OCD-like behaviours in Sapap3-mutant mice. Nature, 448(7156), 894–900. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, C. I., Kegeles, L. S., Levinson, A., et al. (2013). Randomized controlled crossover trial of ketamine in obsessive-compulsive disorder: Proof-of-concept. Neuropsychopharmacology, 38(12), 2475–2483. [CrossRef]

- Berman, R. M., Cappiello, A., Anand, A., et al. (2000). Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients. Biological Psychiatry, 47(4), 351–354. [CrossRef]

- Li, N., Lee, B., Liu, R. J., et al. (2010). mTOR-dependent synapse formation underlies the rapid antidepressant effects of NMDA antagonists. Science, 329(5994), 959–964. [CrossRef]

- Maeng, S., Zarate, C. A. Jr., Du, J., et al. (2008). Cellular mechanisms underlying the antidepressant effects of ketamine: Role of AMPA receptors. Biological Psychiatry, 63(4), 349–352.

- McCarthy, B., Bunn, H., Santalucia, M., et al. (2023). Dextromethorphan-bupropion (Auvelity) for the treatment of major depressive disorder. Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neuroscience, 21(4), 609–616. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, N. (2025). DXM, CYP2D6-inhibiting antidepressants, piracetam, and glutamine: Proposing a ketamine-class antidepressant regimen with existing drugs. Preprints.

- Crewe, H. K., Lennard, M. S., Tucker, G. T., et al. (1992). The effect of selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors on cytochrome P4502D6 (CYP2D6) activity in human liver microsomes. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 34(3), 262–265. [CrossRef]

- Preskorn, S. H., Shah, R., Neff, M., et al. (2007). The potential for clinically significant drug-drug interactions involving the CYP 2D6 system: Effects with fluoxetine and paroxetine versus sertraline. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 13(1), 5–12. [CrossRef]

- Koike, H., Iijima, M., Chaki, S. (2011). Involvement of AMPA receptor in both the rapid and sustained antidepressant-like effects of ketamine in animal models. Behavioural Brain Research, 224(1), 107–111. [CrossRef]

- Winblad, B. (2005). Piracetam: A review of pharmacological properties and clinical uses. CNS Drug Reviews, 11(2), 169–182. [CrossRef]

- Son, H., Baek, J. H., Go, B. S., et al. (2018). Glutamine has antidepressive effects through increments of glutamate and glutamine levels and glutamatergic activity in the medial prefrontal cortex. Neuropharmacology, 143, 143–152. [CrossRef]

- Baek, J. H., Jung, S., Son, H., et al. (2020). Glutamine supplementation prevents chronic stress-induced mild cognitive impairment. Nutrients, 12(4), 910. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, N. (2025). Case series: Marked improvement in treatment-resistant obsessive–compulsive symptoms with over-the-counter glutamatergic augmentation in routine clinical practice. Preprints.

- Cheung, N. (2025). Dosing schedules for dextromethorphan and piracetam in OCD: A case series on diurnal symptom patterns and split-dosing strategies. Preprints.

- Cheung, N. (2025). Oral NMDA and AMPA modulation for refractory obsessive-compulsive symptoms in bipolar disorder: A case series of routine clinical outcomes. Preprints.

- Cheung, N. (2025). Stabilizing the triple comorbidity: A case report of oral glutamatergic augmentation in a patient with bipolar I, OCD, and ADHD. Preprints.

- Cheung, N. (2025). Achieving mood stabilization without mood stabilizers: A retrospective case observation of an adolescent with bipolar-OCD symptoms treated via the NMDA–AMPA axis. Preprints.

- Cheung, N. (2025). Remission of refractory obsessive–compulsive symptoms in an adolescent with autism spectrum disorder: A case report and a review on synaptic plasticity. Preprints.

- Cheung, N. (2025). Cheung's regimen series: Successful conversion from one dose of esketamine to a low-cost oral ketamine-class glutamatergic regimen in treatment-resistant depression and OCD. Preprints.

- Cheung, N. (2025). Rapid remission of refractory hypochondriacal OCD in an elderly patient under glutamatergic augmentation: A high-resolution case observation. Preprints.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).