Submitted:

21 December 2025

Posted:

22 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Screening and Data Extraction

2.4. Risk of Bias Assessment

| Study | Randomisation Process | Deviations from intended interventions | Missing outcome data | Measurement of the outcome | Selection of the reported result | Overall Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alford et al. [33] |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| García et al. [34] |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Giles et al. [35] |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Lassiter et al. [36] |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Liu and Rong [37] |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Ozan et al. [38] |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Peacock et al. [39] |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Seidl et al. [40] |  |

|

|

|

|

|

2.5. Data Synthesis

3. Results

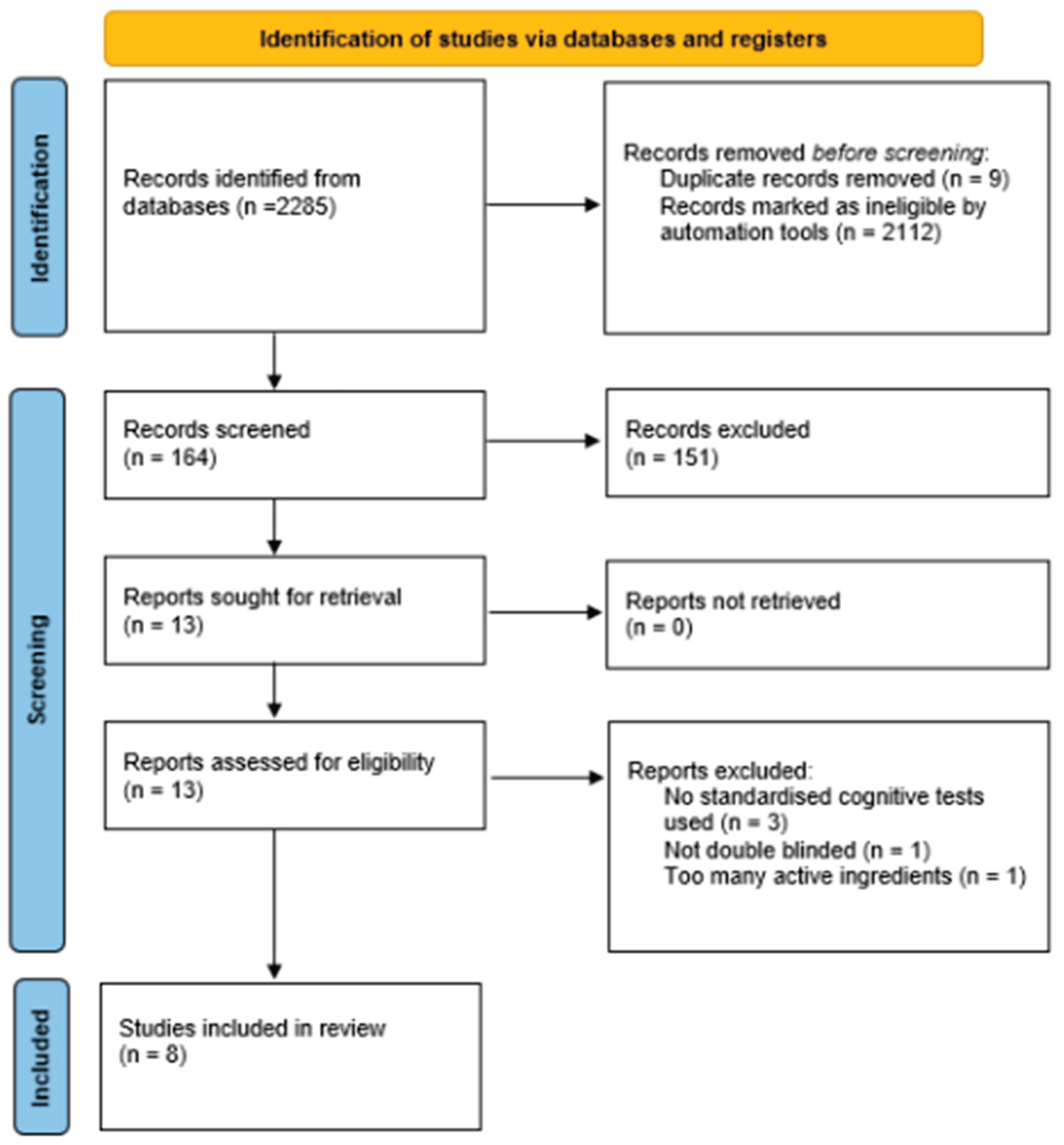

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Included Studies

3.3. Taurine and Cognitive Function

3.3.1. Attention

3.3.2. Executive Function

3.3.3. Working Memory & Immediate Recall

3.3.4. Reaction Time

3.4.. Taurine and Mood

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SCAA | Sulphur-containing amino acid |

References

- Evseeva, O.; Evseeva, S.; Dudarenko, T. The impact of human activity on the global warming. E3S Web of Conferences, 2021; EDP Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, J.E. Global warming has accelerated: are the united nations and the public well-informed? Environment Science and Policy for Sustainable Development 2025, 67(1), 6–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, A. Climate change and human health: impacts, vulnerability and public health. Public health 2006, 120(7), 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patz, J.A. Impact of regional climate change on human health. Nature 2005, 438(7066), 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, T.; Von Braun, J. Climate change impacts on global food security. Science 2013, 341(6145), 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crippa, M. Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions. Nature food 2021, 2(3), 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO, W.H.O. Sustainable healthy diets: Guiding principles; Food & Agriculture Org, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. Reducing climate change impacts from the global food system through diet shifts. Nature Climate Change 2024, 14(9), 943–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. The lancet 2019, 393(10170), 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, C.R. Effect of different tryptophan sources on amino acids availability to the brain and mood in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology 2008, 201, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAfee, A.J. Red meat consumption: An overview of the risks and benefits. Meat science 2010, 84(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, H. Neurodegenerative processes accelerated by protein malnutrition and decelerated by essential amino acids in a tauopathy mouse model. Science advances 2021, 7(43), p. eabd5046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venero, J.L. Changes in neurotransmitter levels associated with the deficiency of some essential amino acids in the diet. British journal of nutrition 1992, 68(2), 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aamer, H. Exploring Taurine's Potential in Alzheimer’s Treatment: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus 2024, 16(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elshorbagy, A. Amino acid changes during transition to a vegan diet supplemented with fish in healthy humans . European Journal of Nutrition 2017, 56(5), 1953–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, J.A. Plasma concentrations and intakes of amino acids in male meat-eaters, fish-eaters, vegetarians and vegans: a cross-sectional analysis in the EPIC-Oxford cohort . European journal of clinical nutrition 2016, 70(3), 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colovic, M.B. Sulphur-containing amino acids: protective role against free radicals and heavy metals . Current medicinal chemistry 2018, 25(3), 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosnan, J.T.; Brosnan, M.E. The sulfur-containing amino acids: an overview . The Journal of nutrition 2006, 136(6), 1636S–1640S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcinkiewicz, J.; Kontny, E. Taurine and inflammatory diseases. Amino acids 2014, 46(1), 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldron, M. The effects of oral taurine on resting blood pressure in humans: A meta-analysis. Current hypertension reports 2018, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, M.; Ahmed, K.; Yim, J.-E. Beneficial effects of taurine on metabolic parameters in animals and humans. Journal of Obesity & Metabolic Syndrome 2022, 31(2), p. 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.-Y.; Kang, Y.-S. Taurine protects glutamate neurotoxicity in motor neuron cells. In in Taurine 10; Springer, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Leon, R. Protective function of taurine in glutamate -induced apoptosis in cultured neurons. Journal of neuroscience research 2009, 87(5), 1185–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G. Amino acids: metabolism, functions, and nutrition . Amino acids 2009, 37, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, C.-L. Taurine improves the spatial learning and memory ability impaired by sub-chronic manganese exposure. Journal of biomedical science 2014, 21(1), p. 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y. Taurine alleviates chronic social defeat stress-induced depression by protecting cortical neurons from dendritic spine loss . Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology 2023, 43(2), 827–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Yuan, M.; Zhang, W. The major biogenic amine metabolites in mood disorders . Frontiers in Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1460631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouraki, V. Association of amine biomarkers with incident dementia and Alzheimer's disease in the Framingham Study . Alzheimer's & Dementia 2017, 13(12), 1327–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P. Taurine deficiency as a driver of aging . Science 2023, 380(6649), p. eabn9257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews . bmj 2021, 372. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, W.S. The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions . ACP journal club 1995, 123(3), A12–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials . bmj 2019, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alford, C.; Cox, H.; Wescott, R. The effects of red bull energy drink on human performance and mood . Amino acids 2001, 21, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, A. Acute effects of energy drinks in medical students . European journal of nutrition 2017, 56, 2081–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giles, G.E. Differential cognitive effects of energy drink ingredients: caffeine, taurine, and glucose . Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior 2012, 102(4), 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassiter, D.G. Effect of an energy drink on physical and cognitive performance in trained cyclists . Journal of Caffeine Research 2012, 2(4), 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Rong, W. Effects of taurine combined with caffeine on repetitive sprint exercise performance and cognition in a hypoxic environment . Scientific Reports 2025, 15(1), 5386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozan, M. Does single or combined caffeine and taurine supplementation improve athletic and cognitive performance without affecting fatigue level in elite boxers? A double-blind, placebo-controlled study . Nutrients 2022, 14(20), 4399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, A.; Martin, F.H.; Carr, A. Energy drink ingredients. Contribution of caffeine and taurine to performance outcomes . Appetite 2013, 64, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidl, R. A taurine and caffeine-containing drink stimulates cognitive performance and well-being . Amino acids 2000, 19, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, N.-y. Interaction between taurine and GABAA/glycine receptors in neurons of the rat anteroventral cochlear nucleus . Brain research 2012, 1472, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, F. Taurine is a potent activator of extrasynaptic GABAA receptors in the thalamus . Journal of Neuroscience 2008, 28(1), 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripps, H.; Shen, W. taurine: a “very essential” amino acid. Molecular vision 2012, 18, 2673. [Google Scholar]

- Di Monte, D.A.; Chan, P.; Sandy, M.S. Glutathione in Parkinson's disease: a link between oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage? Annals of Neurology Official Journal of the American Neurological Association and the Child Neurology Society 1992, 32(S1), S111–S115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menzie, J. Taurine and central nervous system disorders . Amino acids 2014, 46(1), 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Box, A.G. Individual differences influence exercise behavior: how personality, motivation, and behavioral regulation vary among exercise mode preferences . Heliyon 2019, 5(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ide, K.; Secher, N.H. Cerebral blood flow and metabolism during exercise. Progress in neurobiology 2000, 61(4), 397–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambourne, K.; Tomporowski, P. The effect of exercise-induced arousal on cognitive task performance: a meta-regression analysis . In Brain research; 2010; Volume 1341, pp. 12–24. [Google Scholar]

- McMorris, T.; Tomporowski, P.; Audiffren, M. Exercise and cognitive function; John Wiley & Sons, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Young, H.A.; Freegard, G.; Benton, D. Mediterranean diet, interoception and mental health: Is it time to look beyond the ‘Gut-brain axis’? Physiology & Behavior 2022, 257, 113964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romijn, A.R. Perspective: advancing dietary guidance for cognitive health—focus on solutions to harmonize test selection, implementation, and evaluation . Advances in Nutrition 2023, 14(3), 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, H.A. Multi-nutrient interventions and cognitive ageing: are we barking up the right tree? Nutrition Research Reviews 2023, 36(2), 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.M.J. Unveiling Dietary Complexity: A Scoping Review and Reporting Guidance for Network Analysis in Dietary Pattern Research . Nutrients 2025, 17(20), 3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, C.E. Metabolic adaptations to methionine restriction that benefit health and lifespan in rodents . Exp Gerontol 2013, 48(7), 654–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Sinha, R.; Richie, J.P., Jr. Disease prevention and delayed aging by dietary sulfur amino acid restriction: translational implications . Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2018, 1418(1), 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lail, H. Effects of Dietary Methionine Restriction on Cognition in Mice . Nutrients 2023, 15(23), 4950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolt, E. Sulfur amino acid restriction, energy metabolism and obesity: a study protocol of an 8-week randomized controlled dietary intervention with whole foods and amino acid supplements . J Transl Med 2021, 19(1), p. 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, T. Dietary sulfur amino acid restriction in humans with overweight and obesity: Evidence of an altered plasma and urine sulfurome, and a novel metabolic signature that correlates with loss of fat mass and adipose tissue gene expression . Redox Biol 2024, 73, 103192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santulli, G. Functional role of taurine in aging and cardiovascular health: an updated overview . Nutrients 2023, 15(19), 4236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion | Exclusion | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Studies involving healthy adults aged 18 years and over were eligible. No restrictions were placed on gender, ethnicity, or geographical location. | Animal studies, as well as those involving children or participants with neurodegenerative diseases or metabolic disorders, were excluded to maintain relevance to the primary population of interest. |

| Intervention | Supplementation of one or more SCAA (e.g., taurine, methionine, or cysteine), administered alone or in combination with up to four ingredients (e.g., caffeine, glucose). | Studies using over four total ingredients in the intervention, or those including medications as comparators, were excluded to avoid confounding effects. |

| Comparison | Must include a placebo control group. | Does not include a placebo control group. |

| Outcomes | Studies must include outcomes related to cognition (e.g., memory, attention, reaction time, executive function) and/or mood (e.g., anxiety, depression, emotional well-being), measured through validated scales or cognitive tests. | Studies which did not focus on facets of cognitive function and / or mood as outcomes. |

| Context | Studies conducted in contexts of either: 1. Dietary Depletion/Restoration: (e.g., low habitual SCAA intake, plant-based diet transitions). 2. Acute Supplementation/Enhancement: (e.g., supradietary dosing in replete individuals). |

Contexts involving clinical malnutrition, disease-related deficiency, or recovery from surgery/trauma. |

| Study type | Peer reviewed, double-blind, placebo-controlled RCTs. | Non-peer reviewed, non-randomised trials, cohort or case-control studies, observational designs, and any studies lacking a placebo control were excluded. |

| Publication Language | English language. | Published not using English Language. |

| Reference | Population | Aims | Design | Intervention & dosage | Cognitive tests | Mood Measures | Main Findings | Habitual diet / SCAA status assessed? | Authors Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alford et al. [33] | 3 studies* Study 1: N=10 (5f, 5m) aged 18-30 Study 2: N=14 (7f, 7m) aged 18-35 Study3: N= 12 (5f, 7m) aged 20-21 Total N=36 (17f, 19m) aged 18-35 healthy, moderate CAF users |

To investigate the effects of Red Bull Energy Drink on physical endurance (aerobic and anaerobic), psychomotor performance (reaction time, concentration, memory), subjective alertness, and mood. | Double-blind, repeated-measures, randomised crossover across three separate studies. Each study completed within a 4-week period with a one week break for each participant between their two testing sessions. Participants received Red Bull, water (still or carbonated), or a PLA (Still water replaced carbonated water in the 3rd study). |

All studies used a single dose combo of Red Bull (250ml) which included: TAU 1g, CAF 80mg, Glucose 5.25g, Glucuronolactone 600mg Study 1 PLA = carbonated water Study 2 PLA = carbonated water OR no drink control Study 3 PLA = Still water OR "Dummy Energy drink" (flavoured carbonated water) |

5-Choice reaction time ‘Concentration Task’ Immediate Recall Memory Task |

VAS scale - 100mm | Red Bull significantly improved choice reaction time, concentration, and immediate recall compared to control drinks and PLA. Participants reported increased alertness after consuming Red Bull compared to PLA and control drinks. |

No – only caffeine-use status (moderate CAF users) recorded; no assessment of habitual diet or SCAA intake | Red Bull Energy Drink improves both mental and physical performance, including reaction time, memory, concentration, and endurance. These effects are attributed to the combined ingredients, CAF, TAU, and glucose. The drink also increases subjective alertness without significant cardiovascular side effects at rest. Authors commend TAU for “other” positive effects on mood |

| García et al. [34] | N=80 healthy medical students (50m, 30f) mean age 21.45 All participants had consumed energy drinks in their lifetime |

To determine the acute effects of different energy drinks on cardiovascular parameters, stress levels, and working memory in medical students. | Double-blinded, randomised placebo-controlled trial. 4 groups: Control group (carbonated water) Groups A, B & C were commercially available energy drinks Tests were conducted before and after consumption of intervention. |

Single dose Energy drink intervention: All drinks 460ml A: CAF = 149.5mg, Glucose=23g, TAU=0g B: CAF=147.2mg, Glucose=49.6, TAU=1.84g C: CAF= 155mg, Glucose=52.8g, TAU= 1.95g Control: carbonated water |

N-back Task | State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) | Group A showed an increase in working memory performance (no TAU) compared to the control, but no significant differences between groups were found. The STAI test showed a decrease in anxiety in group C. |

No – prior energy drink exposure noted; no systematic assessment of habitual diet, TAU, or SCAA intake | The results highlight the variability of energy drink effects on physiological and cognitive functions, likely due to differing compositions of the drinks. Authors suggest anxiety reduction could be due to ingredient composition. |

| Giles et al. [35] | N=48 Habitual CAF consumers, 18M, 30F Good health, CAF consumers (200 mg/day+), non-smokers, No use of prescription medication except for oral contraceptives. |

To evaluate the individual and combined effects of CAF, TAU, and glucose on cognitive performance and mood in habitual CAF consumers who were CAF-deprived for 24 hours. | Double blind mixed design Within subject, 4 conditions, 3-day washout: Within-participants factors: CAF and TAU treatment. Between-participants factor: glucose treatment or PLA. |

Single dose, combined and PLA separated by a 3-day washout: PLA= 0 CAF+ 0 TAU TAU= 0 CAF+ 2000mg TAU CAF= 200mg CAF+ 0mg TAU CAF*TAU= 200mg + 2000mg Between group factor: Half participants administered 50g Glucose (250mlGLU+sparkling water) or PLA (250ml sparkling water+250ml PLA) |

Attention (alerting, orienting, Executive control), Reaction Time, Working Memory & Psychomotor Performance Attention Network Test (ANT) N-back Task Reaction Time Task (RTT) |

Mood states, CAF withdrawal symptoms Profile of Mood States (POMS) Withdrawal Questionnaire (WQ) |

TAU increased choice reaction time accuracy and improved reaction times in particular working memory tasks (verbal and object N-back). TAU+GLU increased orienting attention Glucose improved object working memory in combination with CAF CAF improved executive control, working memory, and reduced reaction times. It also increased tension, vigour, and reduced fatigue and withdrawal symptoms. |

No – caffeine consumption used as inclusion criterion; no assessment of habitual diet or SCAA intake | TAU had inconsistent effects on mood and cognitive performance. CAF was the main driver of cognitive performance improvements, particularly in attention, working memory, and psychomotor performance. Glucose had limited effects on cognitive performance, and its interaction with CAF and TAU requires further research. |

| Lassiter et al. [36] | N= 15 healthy, trained cyclists (7f, 8 m), aged 20-45 years. | To evaluate the effect of an ED containing CAF, carbohydrates, TAU, and Panax ginseng on cycling time-trial performance and cognitive performance at rest, during exercise, and after exercise. |

Double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised, crossover repeated measures. Each participant completed two experimental trials separated by 6-21 days Participants consumed either the ED or a PLA following a 12-hour fast and CAF abstention followed by a 35km cycling time trial course after intervention. |

Single dose Energy drink intervention: 480 mL containing 54 g carbohydrate, 160 mg CAF, 2 g TAU, 400 mg Panax ginseng PLA = 480mL 0 kcal, CAF-free, no herbal or amino acids. |

Choice Reaction Time Task Go/no-go task (executive function) Stroop Test Tapping task - taps per second psychomotor control test |

N/a | Improved performance was observed on the executive function task and reduced movement times after the race in both the choice reaction and executive function tasks, this was a time effect, PLA also improved post-race. Stroop test reaction times improved post-race but showed no significant treatment effects. Energy drink intervention increased taps per second in the tapping task both pre- and post-exercise compared to PLA. |

No – trained athlete status reported; no habitual diet or SCAA intake assessed | The energy drink enhanced both aerobic performance and certain aspects of cognitive function (tapping speed, executive function) during and after exercise. |

| Liu and Rong [37] | N=16 healthy male university footballers (mean 23.7 y) |

Assess acute effects of TAU, CAF, and TAU+CAF on cognition (Stroop) and exercise performance under hypoxia | Double-blind randomised placebo-controlled crossover RCT 4 groups : PLA, CAF, TAU, TAU*CAF Tests were 60 min after ingestion, 3-day washout period |

Single dose and combination, 3-day washout CAF = 5mg/kg TAU = 50mg/kg TAU*CAF= 50+5mg/kg PLA= maltodextrin 5mg/kg Stroop was administered after a physical warm up (BL), after an exhaustion test (MID), and after intense sprinting (END). |

Stroop task | N/a | CAF improved reaction time vs PLA for congruent and incongruent Stroop trials, no change in accuracy. TAU alone showed no significant results For incongruent and congruent trials, CAF had significantly faster RT than both TAU and PLA. For incongruent trials, CAF improved RT vs TAU*CAF. |

No – no habitual diet or SCAA intake reported | CAF is the primary driver of for cognitive enhancement in Stroop task performance. TAU alone or with CAF is ineffective did not enhance performance during the Stroop task |

|

Ozan et al. [38] |

N=20 male, elite boxers (>10 years’ experience) 18-24 years old (M=22.14±1.42) |

To evaluate the effects of CAF, TAU, and their combination CAF*TAU compared to PLA on athletic performance and exercise-induced fatigue cognitive performance levels. | Double-blind randomised crossover. Four conditions: CAF, TAU, CAF*TAU, PLA All conditions met by each participant in a 72-hour period. |

Single dose, combination, and PLA within 72 hours window. TAU=3g CAF= 6mg/kg CAF*TAU= 6mg/kg + 3g PLA = 300mg of Maltodextrin |

Reaction times and accuracy Stroop test |

N/a | CAF*TAU improved cognitive reaction times and accuracy compared to PLA. TAU significantly improved incongruent Stroop trial accuracy and incongruent trial reaction times vs PLA |

No – no habitual diet or SCAA intake reported | Co-ingesting CAF and TAU improves anaerobic performance, balance, agility, and cognitive function in elite male boxers more effectively than either supplement alone or PLA. |

| Peacock et al. [39] | N=19 right-handed females 19-22 years old (M=20.8) |

To investigate the independent and combined effects of CAF and TAU on behavioural performance, specifically reaction time. | Double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover design. Four counterbalanced conditions: PLA, TAU, CAF, CAF*TAU participant’s sessions were separated by a 2-7-day washout period |

Single dose, combined and PLA separated by 2-7-day washout TAU=1g CAF=80mg PLA=matched to active counterparts' weight with cornflour |

Reaction times (Visual Oddball Task) Stimulus Degradation Task: Measures reaction time to identify digits at three levels of visual degradation (intact, low degradation, high degradation). |

N/a | Non-significant effects of TAU for reaction times in either task. No significant effects of CAF on visual oddball task. CAF significantly improved reaction times in the stimulus degradation task compared to PLA. CAF*TAU did not enhance reaction times compared to CAF. TAU may attenuate CAF's beneficial effects on reaction time. |

No – no habitual diet or SCAA intake reported | Treatments are task dependent. TAU did not have significant independent effects on reaction time and may attenuate CAF’s performance-enhancing effects in particular tasks. The interaction between CAF and TAU requires further research to understand its impact on performance outcomes |

|

Seidl et al. [40] |

N=10 graduate students (23.9 years old ±2.5) 6 female, 4 male Regular CAF consumers n=5 Non-CAF consumers n=5 All healthy, non-smokers |

To evaluate the combined effects of CAF, TAU, and glucuronolactone (CTG) on cognitive performance and mood (replicated quantities of Red Bull drink). To test whether cognitive and mood effects of these ingredients occur at night, when participants are expected to be more fatigued. |

Double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover, repeated-measures design. Two test sessions separated by at least one week. Participants were randomly assigned to receive either CTG or PLA (wheat-bran capsules) and then switched for the other session. All participants had abstained from CAF and alcohol for at least 24 hours before the test. |

Single dose : 1g TAU, 80 mg CAF + 600mg glucuronolactone across 7 capsules Capsules taken with 250ml water |

D2 test of attention P300 ERP wave |

Basler-Befindlichkeitsbogen Questionnaire |

CAF, TAU, glucuronolactone combination improved RT and D2 attention scores vs PLA P300 latency slowed in PLA. CAF, TAU, glucuronolactone group showed non-significant shorter P300 latencies in comparison with pretreatment. PLA experienced significant decline in well-being, vitality, and social extroversion by the end of the session. The active intervention group did not show this decline. |

No – CAF-user vs non-user status recorded; no broader habitual diet or SCAA measures | The combination of CAF, TAU, and glucuronolactone (CTG) significantly improves cognitive performance and mood, especially during periods of fatigue (late night). These effects are not merely due to reversing CAF withdrawal, as non-CAF users benefited similarly to CAF users. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).