Submitted:

21 December 2025

Posted:

22 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Clinical Sample Collection, DNA Isolation and initial Species Identification

Whole Genome Sequencing and Genome Assembly

Overall Genome Relatedness Indices

3. Results

3.1. Identification of 21 Serratia spp. from Severe Bacterial Infections via Clinical Routine Diagnostics

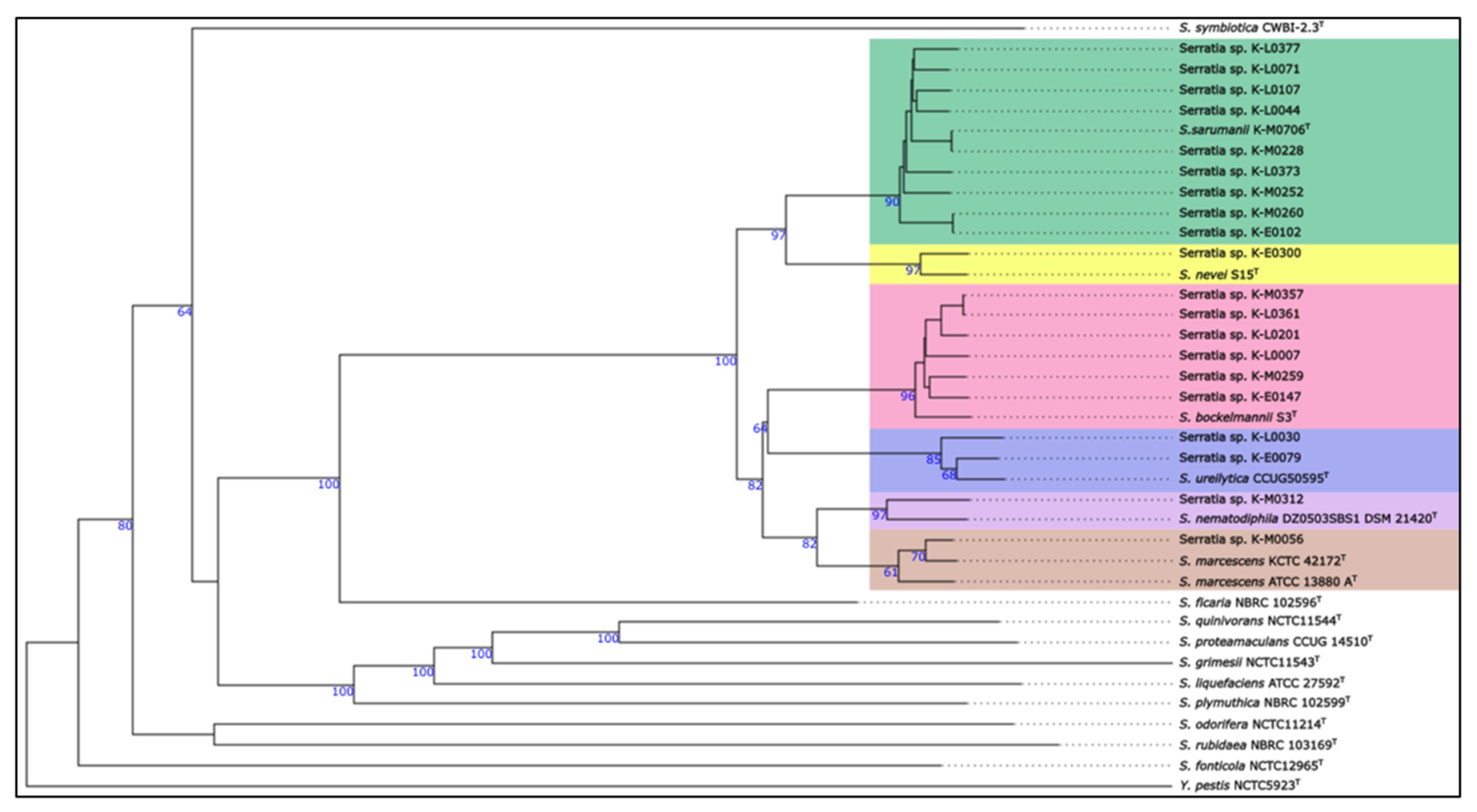

3.2. Whole Genome Comparison Using dDDH and ANI Reveals Serratia sarumanii as the Dominant Species Within the Regional Clinical Serratia Isolates

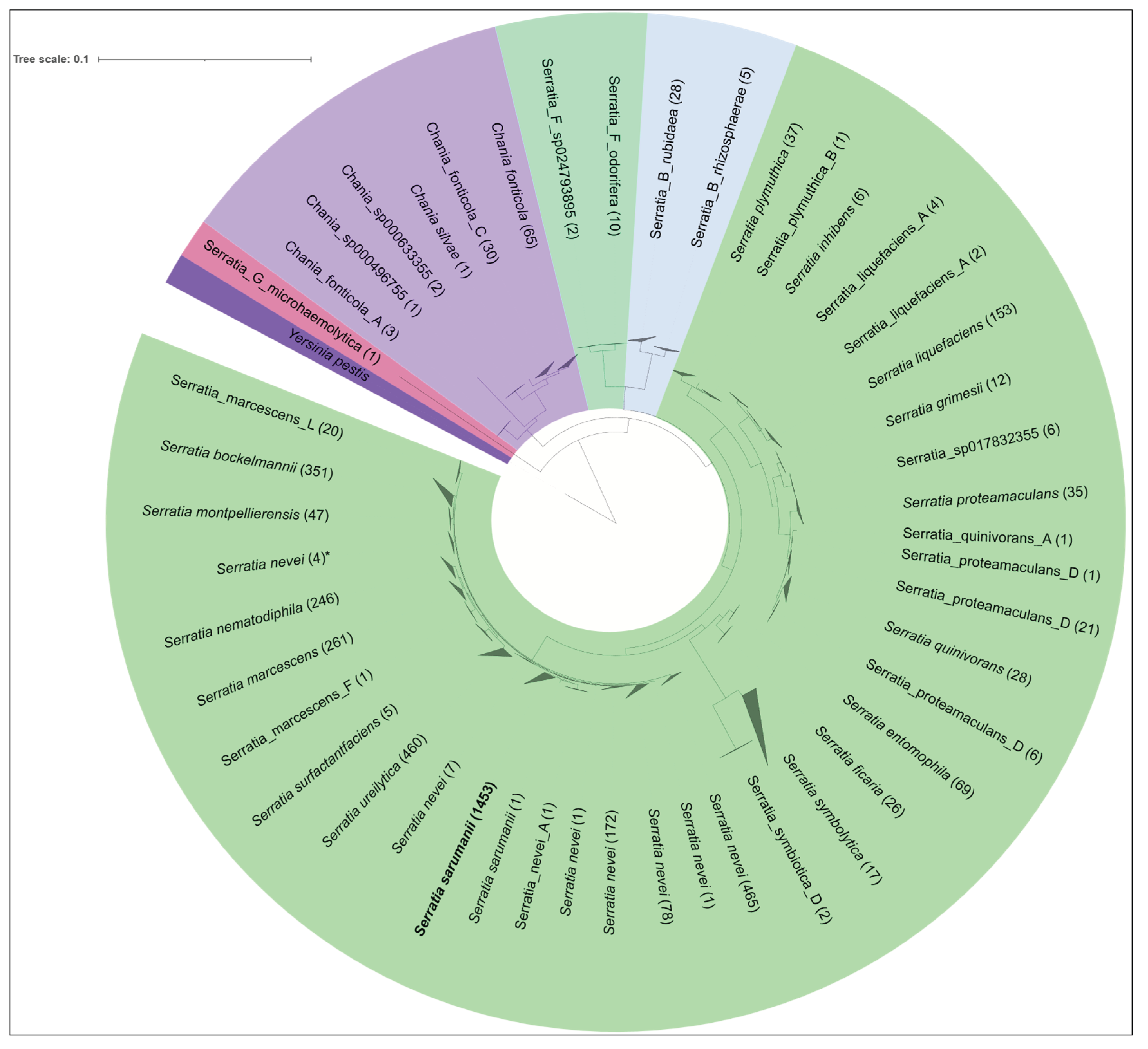

3.3. Classification of the Serratia Genome Sequences within the NCBI Nucleotide Database Confirms Serratia sarumanii to Be the Most Abundant Species Within the ‘Serratia marcescens Complex’ (SMC)

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- de Araújo, H.W.; Fukushima, K.; Takaki, G.M. Prodigiosin Production by Serratia marcescens UCP 1549 Using Renewable-Resources as a Low Cost Substrate. Molecules 2010, 15, 6931–6940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeolu, M.; Alnajar, S.; Naushad, S.; Gupta, R.S. Genome-based phylogeny and taxonomy of the ‘Enterobacteriales’: Proposal for Enterobacterales ord. nov. divided into the families Enterobacteriaceae, Erwiniaceae fam. nov., Pectobacteriaceae fam. nov., Yersiniaceae fam. nov., Hafniaceae fam. nov., Morganellaceae fam. nov., and Budviciaceae fam. nov. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 2016, 66, 5575–5599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioannou, P.; Alexakis, K.; Spentzouri, D.; Kofteridis, D.P. Infective endocarditis by. Serratia species: a systematic review 2022, 34, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahlen, S.D. Serratia infections: From military experiments to current practice. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 2011, 24, 755–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, T.; Mondal, A.; Bandyopadhyay, T.K.; Bhunia, B. Prodigiosin production and recovery from Serratia marcescens: process development and cost–benefit analysis. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2022, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccirilli, A.; Cherubini, S.; Brisdelli, F.; Fazii, P.; Stanziale, A.; Di Valerio, S.; Chiavaroli, V.; Principe, L.; Perilli, M. Molecular Characterization by Whole-Genome Sequencing of Clinical and Environmental Serratia marcescens Strains Isolated during an Outbreak in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU). Diagnostics 2022, Vol. 12 12, 2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Yi, J.; Han, G.; Qiao, L. MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry in Clinical Analysis and Research. ACS Measurement Science Au 2022, 2, 385–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizzini, A.; Greub, G. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry, a revolution in clinical microbial identification. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2010, 16, 1614–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Ahn, D.; Kang, M.; Park, J.; Ryu, D.; Jo, Y.; Song, J.; Ryu, J.S.; Choi, G.; Chung, H.J.; et al. Rapid species identification of pathogenic bacteria from a minute quantity exploiting three-dimensional quantitative phase imaging and artificial neural network. Light Sci Appl 2022, 11, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klages, L.J.; Kaup, O.; Busche, T.; Kalinowski, J.; Rückert-Reed, C. Classification of a novel Serratia species, isolated from a wound swab in North Rhine-Westphalia: Proposal of Serratia sarumanii sp. nov. Systematic and Applied Microbiology 2024, 47, 126527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, T.; Taniguchi, I.; Nakamura, K.; Nagano, D.S.; Nishida, R.; Gotoh, Y.; Ogura, Y.; Sato, M.P.; Iguchi, A.; Murase, K.; et al. Global population structure of the Serratia marcescens complex and identification of hospital-adapted lineages in the complex. Microb. Genom. 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aracil-Gisbert, S.; Fernández-De-Bobadilla, M.D.; Guerra-Pinto, N.; Serrano-Calleja, S.; Pérez-Cobas, A.E.; Soriano, C.; de Pablo, R.; Lanza, V.F.; Pérez-Viso, B.; Reuters, S.; et al. The ICU environment contributes to the endemicity of the "Serratia marcescens complex" in the hospital setting. mBio 2024, 15, e0305423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolmogorov, M.; Bickhart, D.M.; Behsaz, B.; Gurevich, A.; Rayko, M.; Shin, S.B.; Kuhn, K.; Yuan, J.; Polevikov, E.; Smith, T.P.L.; et al. metaFlye: scalable long-read metagenome assembly using repeat graphs. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 1103–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wick, R.R.; Schultz, M.B.; Zobel, J.; Holt, K.E. Bandage: interactive visualization of de novo genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 3350–3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatusova, T.; DiCuccio, M.; Badretdin, A.; Chetvernin, V.; Nawrocki, E.P.; Zaslavsky, L.; Lomsadze, A.; Pruitt, K.D.; Borodovsky, M.; Ostell, J. NCBI prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res 2016, 44, 6614–6624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Göker, M. TYGS is an automated high-throughput platform for state-of-the-art genome-based taxonomy. Nature Communications 2019, 10:1 2019(10), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Carbasse, J.S.; Peinado-Olarte, R.L.; Göker, M. TYGS and LPSN: a database tandem for fast and reliable genome-based classification and nomenclature of prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, D801–D807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arahal, D.R.; Bull, C.T.; Busse, H.-J.; Christensen, H.; Chuvochina, M.; Dedysh, S.N.; Fournier, P.-E.; Konstantinidis, K.T.; Parker, C.T.; Rossello-Mora, R.; et al. Guidelines for interpreting the International Code of Nomenclature of Prokaryotes and for preparing a Request for an Opinion. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 2023, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaumeil, P.-A.; Mussig, A.J.; Hugenholtz, P.; Parks, D.H. GTDB-Tk v2: memory friendly classification with the genome taxonomy database. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 5315–5316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, D.H.; Chuvochina, M.; Rinke, C.; Mussig, A.J.; Chaumeil, P.-A.; Hugenholtz, P. GTDB: an ongoing census of bacterial and archaeal diversity through a phylogenetically consistent, rank normalized and complete genome-based taxonomy. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, D785–D794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Auch, A.F.; Klenk, H.P.; Göker, M. Genome sequence-based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinformatics 2013, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henares, D.; Cubero, M.; Martinez-de-Albeniz, I.; Arranz, A.; Rocafort, M.; Brotons, P.; Perez-Argüello, A.; Troyano, M.J.; Gene, A.; Lluansi, A.; et al. Rapid identification of a Serratia marcescens outbreak in a neonatal intensive care unit by third-generation long-read nanopore sequencing. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2025, 14, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalifa, H.O.; Kayama, S.; Elbediwi, M.; Yu, L.; Hayashi, W.; Sugawara, Y.; Mohamed, M.-Y.I.; Ramadan, H.; Habib, I.; Matsumoto, T.; et al. Genetic basis of carbapenem-resistant clinical Serratia marcescens in Japan. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2025, 42, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taxt, A.M.; Eldholm, V.; Kols, N.I.; Haugan, M.S.; Raffelsberger, N.; Asfeldt, A.M.; Ingebretsen, A.; Blomfeldt, A.; Kilhus, K.S.; Lindemann, P.C.; et al. A national outbreak of Serratia marcescens complex: investigation reveals genomic population structure but no source, Norway, June 2021 to February 2023. Euro Surveill. 2025, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prjibelski, A.; Antipov, D.; Meleshko, D.; Lapidus, A.; Korobeynikov, A. Using SPAdes De Novo Assembler. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics 2020, 70, e102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, G.G.R.; Charlesworth, J.; Miller, E.L.; Casey, M.J.; Lloyd, C.T.; Gottschalk, M.; Tucker, A.W.D.; Welch, J.J.; Weinert, L.A. Genome Reduction Is Associated with Bacterial Pathogenicity across Different Scales of Temporal and Ecological Divergence. Mol Biol Evol 2021, 38, 1570–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Li, Z.; Liu, X.; Li, Z.; Lei, Z.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Yang, X.; Lu, B. In-host intra- and inter-species transfer of blaKPC-2 and blaNDM-1 in Serratia marcescens and its local and global epidemiology. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2024, 64, 107327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample name | Hospital of origin1 | Collected from | Identification method2 | Source |

| K-E0079 | EvKB | blood | MS, BA | this study |

| K-E0102 | EvKB | peritoneal lavage | MS, BA | this study |

| K-E0147 | EvKB | blood | MS, BA | this study |

| K-E0300 | EvKB | blood | MS, BA | this study |

| K-L0007 | KL | blood | MS, BA | this study |

| K-L0030 | KL | blood | MS, BA | this study |

| K-L0044 | KL | blood | MS, BA | this study |

| K-L0071 | KL | blood | MS, BA | this study |

| K-L0107 | KL | blood | MS, BA | this study |

| K-L0201 | KL | blood | MS, BA | this study |

| K-L0361 | KL | blood | MS, BA | this study |

| K-L0373 | KL | punctation (aszites) | MS, BA | this study |

| K-L0377 | KL | blood | MS, BA | this study |

| K-M0056 | KMB | blood | BA | this study |

| K-M0228 | KMB | wound swab | BA | [10] |

| K-M0252 | KMB | urine | BA | [10] |

| K-M0259 | KMB | wound swab | BA | this study |

| K-M0260 | KMB | wound swab | BA | [10] |

| K-M0312 | KMB | blood | BA | this study |

| K-M0357 | KMB | bronchial secret | BA | this study |

| K-M0706 | KMB | wound swab | BA | [10] |

| Sample name | Assigned species | dDDH [%] to closest type strain1 | ANI [%]2 | AF [%]3 |

| K-E0079 | Serratia ureilytica | 92.0 | 99.02 | 93.70 |

| K-E0102 | Serratia sarumanii | 90.4 | 98.80 | 93.00 |

| K-E0147 | Serratia bockelmannii | 90.3 | 98.75 | 91.90 |

| K-E0300 | Serratia nevei | 91.5 | 98.86 | 90.10 |

| K-L0007 | Serratia bockelmannii | 90.1 | 98.61 | 90.40 |

| K-L0030 | Serratia ureilytica | 88.5 | 98.53 | 93.60 |

| K-L0044 | Serratia sarumanii | 93.4 | 99.03 | 96.80 |

| K-L0071 | Serratia sarumanii | 93.2 | 99.08 | 96.80 |

| K-L0107 | Serratia sarumanii | 93.1 | 99.02 | 96.30 |

| K-L0201 | Serratia bockelmannii | 90.5 | 98.73 | 90.60 |

| K-L0361 | Serratia bockelmannii | 90.9 | 98.80 | 91.40 |

| K-L0373 | Serratia sarumanii | 92.0 | 98.92 | 95.00 |

| K-L0377 | Serratia sarumanii | 92.0 | 98.92 | 95.20 |

| K-M0056 | Serratia marcescens | 94.9 | 98.75 | 94.60 |

| K-M0228 | Serratia sarumanii | 100.0 | 100.00 | 99.90 |

| K-M0252 | Serratia sarumanii | 91.4 | 98.80 | 95.80 |

| K-M0259 | Serratia bockelmannii | 90.5 | 98.75 | 92.00 |

| K-M0260 | Serratia sarumanii | 90.0 | 98.58 | 93.30 |

| K-M0312 | Serratia nematodiphila | 84.9 | 98.24 | 88.00 |

| K-M0357 | Serratia bockelmannii | 90.7 | 98.75 | 91.20 |

| K-M0706 | Serratia sarumanii | 100.0 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).