1. Introduction

Diabetes is a chronic metabolic disorder characterized by elevated blood glucose levels leading to serious complications. There are two types of diabetes that are common. Type 2 diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) occurs when the body becomes resistant to insulin or produces limited insulin. T2DM accounts for most cases globally, while Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus (T1DM), also known as juvenile diabetes, results from pancreatic insulin deficiency, producing insignificant or no insulin at all[

1]. Globally, over 830 million people have diabetes, with the majority of cases from middle-income countries[

2]. The global prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance was 374 million in 2019, projected to 454 million in 2030, and 548 million by 2045[

3], with an estimated projection of diabetes mellitus to 693 million by 2045[

4]. The prevalence of type 2 diabetes has grown significantly in recent years, primarily due to the rise in obesity and sedentary lifestyles[

5]

Diabetes mellitus (DM) was first described by Aretaeus of Cappadocia in the 2nd century AD, with the term

mellitus. Later added by Thomas Willis in the 17th century relating to the sweet taste of urine. Over time, major scientific milestones, including those by Claude Bernard, Oskar Minkowski, Joseph Von Mering, and the discovery of insulin by Banting and Macleod, have contributed to our current understanding of diabetes and its management [

6]. Diabetes mellitus is among the twenty-first century's most alarming public health challenges[

7]. Urbanization, obesity, hypertension, and physical inactivity are key drivers of diabetes [

8]. Debatably, there are underreported diabetes related mortalities due to attribution to complications like cardiovascular disease[

9].

Pharmacological treatments are widely used to manage T2DM. However, the complexity of diabetes mellitus, characterized by insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction, often necessitates multiple drug therapy, impeding the optimal glycemic control [

10]. However, non-pharmacological interventions, particularly medical nutrition therapy (MNT), weight management, and physical activity, play a vital role in the prevention and management of T2DM [

11,

12]. Despite dietary efforts, glycemic control remains suboptimal, highlighting the need for improved patient motivation and structured lifestyle interventions[

13].

Thus, establishing diabetes as a chronic, escalating global health crisis with a well-documented historical context. The disease's complexity necessitates a multifaceted management approach, where, despite pharmacological advances, non-pharmacological strategies like lifestyle modification remain fundamentally important for effective control.

2. Nonpharmacological Factors Influencing Diabetic Interventions

2.1. Dietary Interventions

Dietary or nutritional intervention significantly reduces blood sugar levels in Type 2 diabetes (T2D) and improves insulin sensitivity[

14]. Similarly, the Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet promotes a diet rich in potassium and magnesium while reducing sodium intake. It emphasizes vegetables, whole grains, fruits, fish, poultry, nuts, beans, and low low-fat diet, which is effective in lowering blood pressure and reducing the risk of diabetes[

15]. Similarly, the Mediterranean diet, primarily referring to plant-based foods, lowers the risk of type 2 diabetes. It improves glycemic control by reducing HbA1c from 0.1% to 0.6%. [

16]. The diets high in glycemic load, like processed foods and sugar-sweetened beverages, increase the risk of T2DM[

17]. Low glycemic index (LG) food helps in moderating glycemic management when intertwined with personalized intensive nutrition education and counseling in managing type 2 diabetes[

18], reduction of obesity, hyperlipidemia, and cardiovascular disease[

19,

20]. Dietary Approaches for diabetic patients are not a one-size-fits-all approach; different patients require specific dietary therapies based on their nutritional state and stage of diabetes progression. For instance, during the initial stages, weight reduction and calorie-restricted diets are applicable irrespective of the composition[

21]. According to the American diabetes association, normal postprandial blood glucose levels are <140mg/dl, prediabetes is indicated at 140-199mg/dl, and diabetes is diagnosed at ≥200mg/dl after 2 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test[

22]. A combination of the DASH diet with physical activity helps to maintain a normal BMI AND Achieve immediate blood pressure control in older patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension[

23].[

24]. A high-fiber diet improves glucose homeostasis in type 2 DM patients. It also enriches gut microbes and reduces opportunistic pathogens [

25]. Small and frequent meals are essential in diabetic patients [

26].

Therefore, structured dietary plans like the DASH and Mediterranean diets, along with low-glycemic and high-fiber foods, form a cornerstone of effective T2DM management. These interventions highlight that successful glycemic control is achievable through personalized, evidence-based nutritional strategies rather than a universal approach.

2.2. Physical Activity

Regular physical activity has been widely recognized as an effective strategy in moderating the risk of T2DM. The physiological mechanisms underlying the benefits of physical activity are multifaceted. It involves improvements in insulin sensitivity, glucose homeostasis, and overall metabolic functions [

27]. Further, regular physical activity has been associated with a reduction in the risk of coronary heart disease, venous thromboembolic events, and cerebrovascular disease compared to inactivity [

28]. Thus, daily exercise is key for managing diabetes and obesity, with recommended dietary modifications[

29]. Similarly, blood lipid profiles and cardiac health can be maintained with several aerobic exercises at high intensity, to resistance training.[

30]. Aerobic exercise reduces VLDL and triglycerides of the lipid profile in T2DM [

31],[

32]. Further, enhances physical stamina and quality of life, particularly for those with comorbidities like obesity. With a proper exercise and diet combination, diabetes can be reduced by 20%[

33]. However, untrained individuals need a consultant or an expert before starting the exercise regimen to evaluate potential health issues and ensure safety [

34]. Although it doesn’t have a dramatic role in glycemic control[

35]. Physical activity has emerged as a crucial component in the comprehensive management of type 2 diabetes[

36].

Therefore, regular physical activity is a cornerstone of T2DM management, conferring benefits that extend beyond improved insulin sensitivity and glycemic control to encompass cardiovascular and metabolic health. A structured and safely implemented exercise regimen is essential for mitigating diabetes-related complications and enhancing overall quality of life.

2.3. Behavioral and Psychological Interventions

Psychological interventions effectively reduce diabetes related distress and HbA1c levels, though more rigorous studies are needed to fully evaluate their clinical potential[

37]. Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) improves the self-management practice of type 2 diabetic patients[

38]. It also helps to manage depressive symptoms, treatment adherence, sustain motivation, and develop a positive attitude toward life[

39]. Similarly, mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) training also shows similar outcomes by reducing anxiety, depressive symptoms, along with a reduction in serum cortisol level in older adults with T2DM, ultimately enhancing the quality of life[

40,

41]. Even regular diabetic counselling helps lower the incidence of cardiovascular events and deaths among diabetic patients[

42]. Therefore, psychological stability improves the overall lifestyle. Lifestyle interventions to standard diabetes treatment in patients, even with TB and diabetes, also showed a significant reduction in HbA1c [

43]. Additionally, maintaining positivity is crucial as negative emotions like distress and depression worsen glycemic control and reduce self-management ability[

44].

Thus, it is evident that behavioral and psychological interventions target the mental and emotional dimensions of diabetes care. Techniques such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and mindfulness not only alleviate distress and depression but also critically enhance self-management adherence and motivation. This establishes psychological well-being as an indispensable component of a holistic lifestyle approach, directly influencing glycemic control and overall quality of life.

2.4. Self-Monitoring and Self-Management Education

Diabetic awareness, education, knowledge, and self-care behavior, among patients and families, help manage type 2 diabetes mellitus efficiently[

45]. Similarly, the Community Service Program (CSP) with interactive sessions and awareness enhances self-management among T2DM patients [

46]. Additionally, a personalized approach to blood glucose self-monitoring effectively reduces late complications, increases safety by lowering hypoglycemia, and improves disease management. It is effective in patients with intensified insulin or pump therapy, where structured and frequent monitoring can enhance glycemic control and variability[

47]. To further intensify the progress of telemedicine and mobile phone messaging applications, enhance convenient home monitoring, which is cost-effective and provides easy education and motivation. Similarly, videoconferencing allows face-to-face interactions, enabling better assessment of patients and facilitating remote training on various diabetes-related aspects[

48]. Therefore, to obtain better results, patients with poorly controlled blood sugars can enroll in commercial remote diabetes monitoring programs, which have shown enhanced HbA1c control, treatment satisfaction, and overall positive experience similar to the patients receiving specialized care at diabetic centers. Thus, integration of diabetes remote monitoring programs into routine clinical care can maximize the benefits with a low financial burden[

49]. This gives a better management option rather than only a self-monitoring process, where patients sometimes misinterpret and, on rare occasions, have proved to be contraindicatory.[

50].

Therefore, self-management education and technology-assisted monitoring make the critical link that translates lifestyle and psychological interventions into daily practice. By empowering patients with knowledge and real-time feedback tools, these strategies enable personalized, proactive disease management, ultimately enhancing safety, improving glycemic control, and solidifying the effectiveness of the entire treatment plan.

2.5. Weight Management

Weight management is vital in the mitigation or moderation of diabetes; obesity, which is marked by a BMI ≥30 kg/m², is a real risk. Again, physical activity is crucial in managing obesity and mitigating health risks associated with excess weight[

51]. Exercise contributes to weight loss and metabolic control; however, effects are less pronounced than dietary changes, with average weight loss at 3.4 lbs. and a reduced glycosylated hemoglobin by 0.8%. Combined diet, exercise, and behavioral therapy yield moderate improvements[

52]. Thus, weight reduction is a primary act to manage diabetes[

53]. Diabetes and obesity are globally rising chronic disorders interconnected through BMI, insulin resistance, and pancreatic β-cell dysfunction. The development of diabetes is linked to β-islet cell impairment and insulin resistance, with early-life weight gain increasing the risk of type 1 diabetes[

54].

Visceral obesity contributes to diabetes development by releasing free fatty acids and inflammatory cytokines that promote insulin resistance. Hence, Type 2 diabetes mellitus is influenced by a combination of insulin resistance, insulin deficiency, genetic predispositions, and environmental factors like increased weight gain and decreased physical activity [

55]. Hence, lifestyle changes, including modest weight loss (5-10%) and 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity weekly, effectively reduce the risk of Type 2 diabetes mellitus [

56]. So, Lifestyle and dietary modification are essential to manage insulin resistance and prevent type 2 diabetes, with interventions like low-carbohydrate and Mediterranean diets[

57]. For this reason, dietary changes and physical activity are critical in diabetes management and are endorsed globally, with clinical evidence supporting the benefits of modest weight loss (5%-10%) on glycemic and metabolic outcomes[

58]. Healthcare professionals should also consider sex-related differences in individuals with type 1 diabetes. Both men and women report similar challenges with time management for physical activity, though women additionally manage hormonal fluctuations due to menstruation[

59].

Therefore, weight management is a non-negotiable component in breaking the cycle of obesity-driven diabetes. By demonstrating that targeted lifestyle modifications to achieve modest weight loss directly counteract the core mechanisms of insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction. It provides a clear and evidence-based imperative for making weight control a central goal in clinical and self-management practices.

2.6. Sleep Quality and Diabetes

Poor sleep quality is linked to macrovascular disease in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). This means that how well a person sleeps may impact their risk of heart-related issues in the context of T2DM[

60]. In one 14-year-long study, about 18% of initially healthy participants developed diabetes, which was associated with both short sleep (<5 hours) and long sleep (>10 hours). Notably, those sleeping >10 hours were more likely to develop diabetes due to reduced insulin secretory function[

61]. Quality sleep significantly impacts the blood glucose levels in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus, highlighting the need to maintain good sleep quality to enhance blood glucose levels[

62]. Although there are controversies over the association between sleep and diabetes mellitus. As sleep quality is compromised in diabetic patients; however, there is no significant association between sleep quality and intensifying glycemic levels in elderly patients with type-2 DM [

63]. but a notable relationship between sleep quality and glycemic control among diabetic individuals is indicated [

64]. [

60,

61,

62].

Therefore, sleep habits directly impact one's blood sugar level. Both insufficient sleep and excessively long sleep can disrupt the body's insulin function and increase heart disease risk, making quality sleep a vital, which is often overlooked, part of diabetes management.

2.7. Smoking and Diabetes

Among smokers, the risk of obesity rises with the amount smoked; heavy smokers are more likely to be obese than light smokers. After quitting, obesity risk decreases over time but remains higher than that of current smokers for over 30 years, eventually equaling the risk of never-smokers[

65]. Diabetic smokers are at a higher risk of experiencing aggravated periodontal status. They have a higher plaque index compared to non-diabetic and healthy smokers[

66]. Similarly, Maternal smoking frequency is linked to childhood status like overweight and obesity. Obese mothers influence the weight anomalies in children which requires relevant interventions like support programs, healthy food promotion, and physical activity, educational programs to reduce tobacco consumption among pregnant women and caregivers are vital[

67].

Smokers typically have poor diets and gain about 4.67 kg within 12 months of quitting. Weight management in smokers is challenging, necessitating treatments targeting nicotine addiction and post-cessation weight gain. Adolescents who smoke often have similar or higher BMIs than nonsmokers. Metabolic factors like ghrelin and leptin may affect smoking behaviors[

68]. Current and former smoking are associated with increased waist circumference (WC) among overweight/obese women who are heavy smokers, showing an increase of 4.48 cm WC compared to normal-weight never smokers. Regular health checks can prevent the risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes in smokers[

69]. Continuous exposure to secondhand smoke (SHS) elevates the risk for obesity in boys during early adolescence, as it is highly associated with higher BMI. Thus, quitting SHS helps prevent obesity in early adolescence[

70]. Caffeine and tobacco products have detrimental effects on young university students. Similarly, higher energy drink consumption, along with tobacco and smoking, has contributed to weight gain. There is a strong association between central obesity and smoking, increased age, and BMI, indicating specific risk factors for central obesity among male university students[

71]. The combination of obesity and smoking increases circulatory disease mortality risk 6- to 11-fold in individuals under 65 compared to normal-weight non-smokers[

72]. However, Smoking cessation is associated with a decrease in systolic blood pressure. However, weight gain is common in those who quit smoking[

73].

Therefore, Smoking and obesity form a vicious cycle that significantly increases diabetes and heart disease risk. While quitting is essential, it requires proactive weight management strategies, as the metabolic damage from smoking can persist for years, affecting even those exposed to secondhand smoke.

2.8. Alcohol and Diabetes

The association between alcohol consumption and T2DM was primarily observed in overweight and obese individuals (those with a BMI above 25 kg/m²). This suggests that BMI may play a crucial role in mediating the effects of alcohol on diabetes risk[

74]. Furthermore, gender may play a role in how alcohol consumption affects the risk of developing T2DM[

75]. Moderate alcohol consumption is associated with a decreased incidence of diabetes mellitus and a decreased incidence of heart disease in persons with diabetes[

76]. Moderate alcohol consumption reduces the risk of diabetes and improves cardiovascular health. However, it depends on factors like the type of alcoholic beverages, gender, and body mass index[

77]. Therefore, moderate alcohol consumption reduces about 30% of the risk of type 2 DM [

78,

79]. Contrastingly, high alcohol consumption and binge drinking can raise the risk of type 2 DM[

80,

81]. Chronic heavy consumption deteriorates glucose tolerance and insulin resistance, and this may be one of the mechanisms involved in the malignant effect of alcohol on the development of diabetes[

82].

Therefore, the relationship between alcohol and diabetes is a double-edged sword. Moderate intake might lower risk, but excessive consumption reliably promotes insulin resistance and disease progression. Similarly, Body Mass Index (BMI) is a critical factor, along with being overweight, that significantly increases the risk of T2DM.

Table 1.

Summary of Lifestyle Interventions in Diabetes Management.

Table 1.

Summary of Lifestyle Interventions in Diabetes Management.

| Intervention Categories |

Key Components of the Mechanism |

Primary Outcomes/ Benefits |

Challenges |

Key Evidence and Recommendation |

Reference |

| Diet Modification |

Mediterranean and DASH diets moderated the caloric intake. |

Improved glycemic control, reduced diabetes risk |

Patient adherence, nutritional balance |

Consistent meal planning. High fiber, limited fat, and carbohydrate. |

[14] [19] [16]. |

| Physical Activity |

Enhances insulin sensitivity, burns glucose |

Reduce the risk of CHD, increase insulin sensitivity |

Risk of hypoglycemia, patient motivation |

Regular physical activity. Avoid a sedentary lifestyle |

[36] [33,28,27] |

| Weight Management |

Reduces insulin resistance, lowers inflammation |

Improved glycemic control, reduced medication needs |

Long-term adherence, lifestyle changes |

5-10% body weight reduction |

[58] [51,52,55] |

| Stress Management |

Reduces cortisol levels, improves insulin sensitivity |

Stabilizes blood sugar, enhances well-being |

Consistency in practice, identifying stressors |

Daily relaxation techniques, meditation |

[[40,41,43,42]. |

| Sleep Management |

Regulates hormonal balance, reduces insulin resistance |

Better glycemic control, improved energy levels |

Sleep disturbances, lifestyle factors |

6-8 hours of quality sleep |

[60,61,62]. |

| Self-Monitoring & Education |

Enhances disease management and awareness |

Improved glycemic control, better treatment adherence |

Patient education and awareness |

Regular monitoring, use of technology |

[47,50,49,48]. |

| Smoking Cessation |

Reduces systemic inflammation, improves overall health |

Decreased risk of complications, improved oral health |

Weight gains post-cessation |

Immediate cessation; support programs |

[66,69,73,72] |

| Alcohol Consumption |

Moderate intake reduces diabetes risk; excessive intake worsens glycemic control |

Improved cardiovascular health with moderation |

Risk of high intake and its impact |

Moderate consumption; avoid excessive drinking |

[74,75,76,78,79]. |

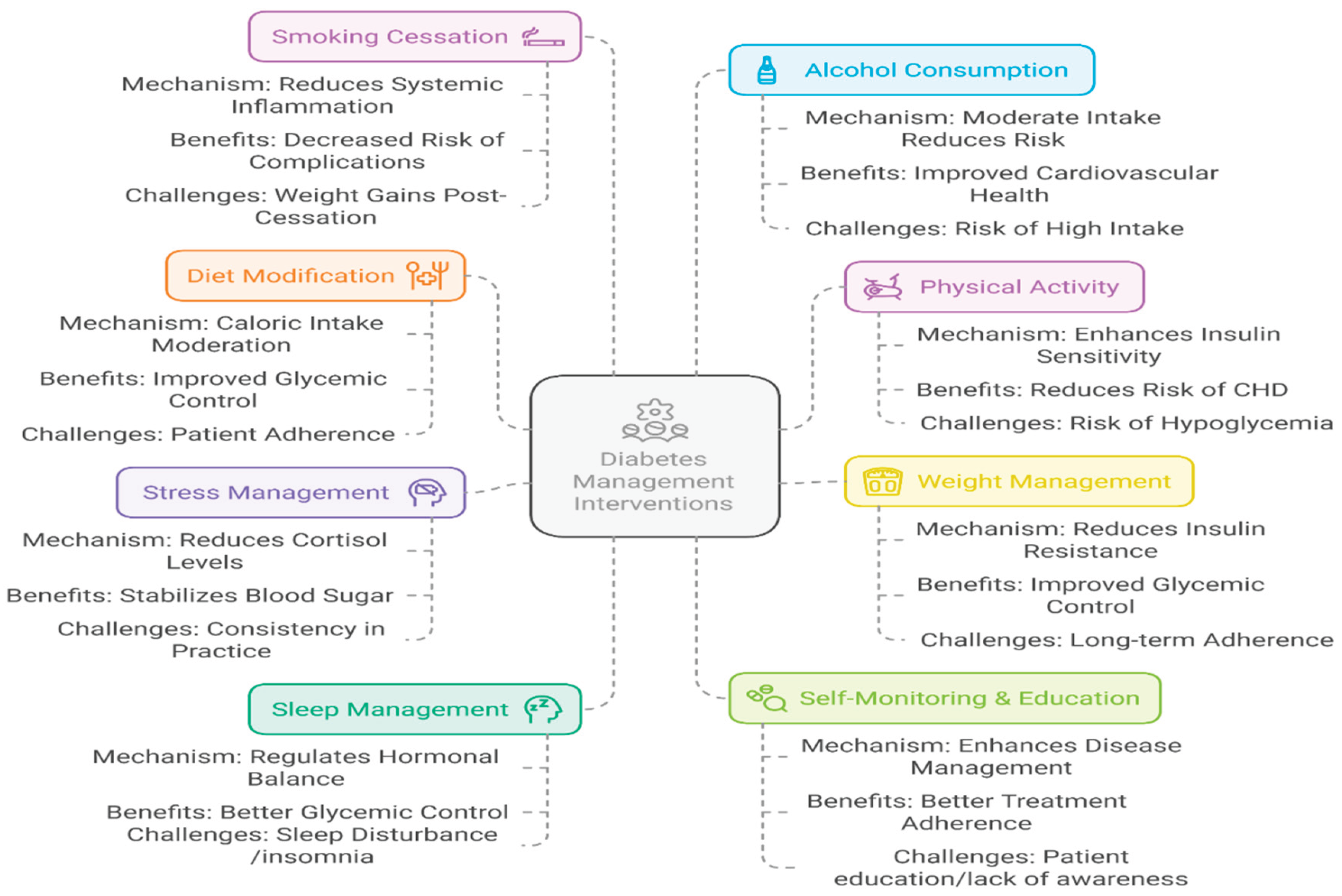

Figure 1.

Lifestyle modification for diabetes intervention.

Figure 1.

Lifestyle modification for diabetes intervention.

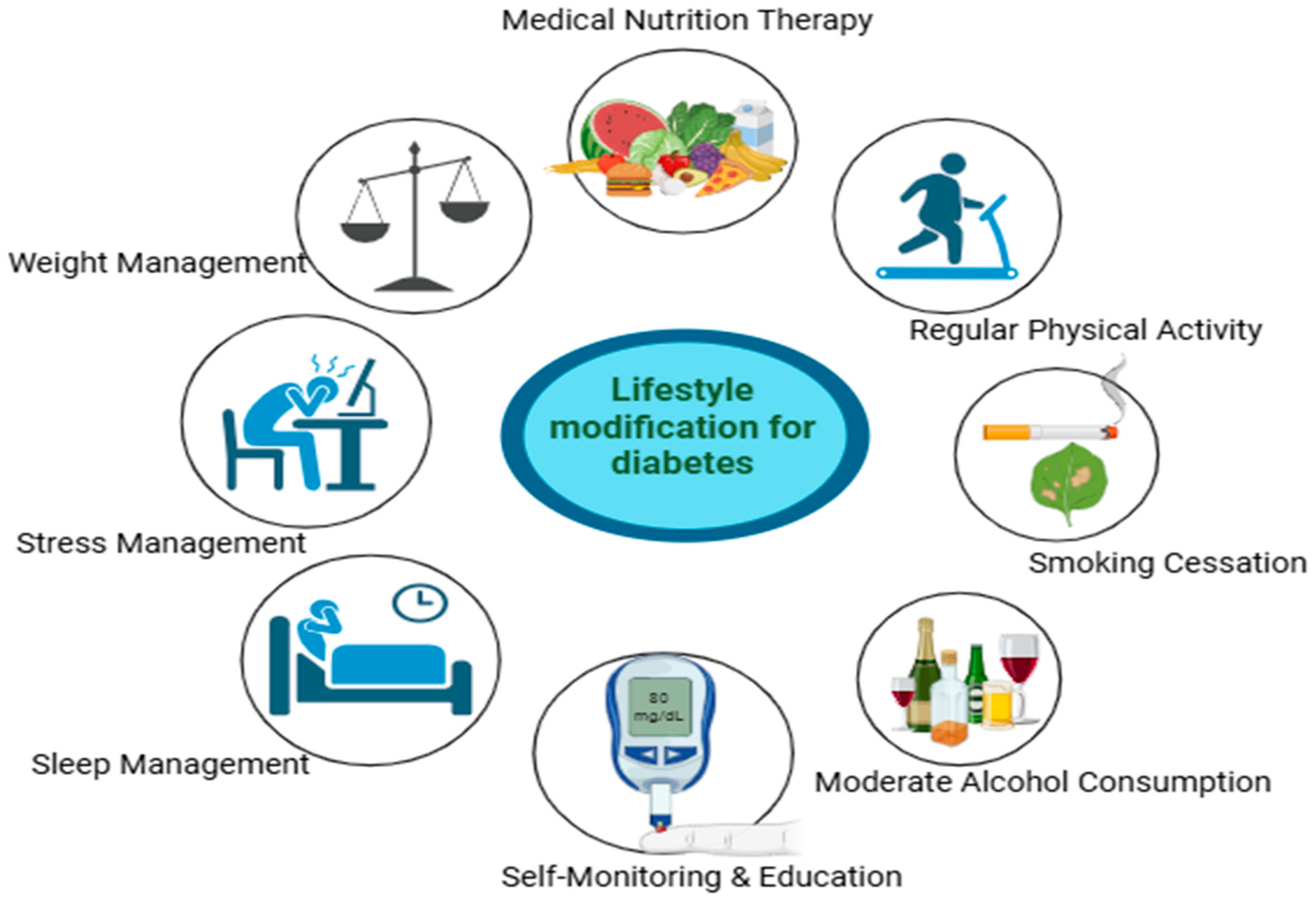

Figure 2.

A holistic framework for the non-pharmacological management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus.

Figure 2.

A holistic framework for the non-pharmacological management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus.

3. Summary

The lifestyle-related strategies are cornerstone approaches for managing Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Evidence demonstrates that dietary interventions, particularly the Mediterranean and DASH diets, function by modulating specific nutritional factors such as fiber content, glycemic index, and fatty acid profiles to improve metabolic outcomes. The combination of these diets with sustained physical activity and behavioral improvement to achieve modest weight loss forms an effective strategy for improving insulin sensitivity and glycemic control. Furthermore, addressing often overlooked factors such as sleep hygiene, stress through cognitive-behavioral therapy, and smoking cessation is essential for a comprehensive and holistic treatment model. This collective, multi-faceted approach offers a powerful, sustainable, and low-risk paradigm to reduce the disease burden of T2DM, presenting a significant opportunity for public health initiatives and future research in nutritional science and preventive medicine.

Funding

This study has not been funded by an external funding agency.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

Acknowledgment

Yadap Prasad Timsina sincerely thanks the Royal Thimphu College (Bhutan) for providing all the necessary support and platform.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- WHO. Diabetes. WHO 2022. https://www.who.int/health-topics/diabetes#tab=tab_1 (accessed May 17, 2025).

- Diabetes n.d. https://www.who.int/health-topics/diabetes#tab=tab_1 (accessed May 17, 2025).

- 2045 n.d.

- Liu J, Ren ZH, Qiang H, Wu J, Shen M, Zhang L, et al. Trends in the incidence of diabetes mellitus: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017 and implications for diabetes mellitus prevention. BMC Public Health 2020;20. [CrossRef]

- Colberg SR, Sigal RJ, Fernhall B, Regensteiner JG, Blissmer BJ, Rubin RR, et al. Exercise and type 2 diabetes: The American College of Sports Medicine and the American Diabetes Association: Joint position statement. Diabetes Care 2010;33. [CrossRef]

- Karamanou M. Milestones in the history of diabetes mellitus: The main contributors. World J Diabetes 2016;7:1. [CrossRef]

- Zimmet PZ, Magliano DJ, Herman WH, Shaw JE. Diabetes: A 21st century challenge. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014;2:56–64. [CrossRef]

- Cho NH, Shaw JE, Karuranga S, Huang Y, da Rocha Fernandes JD, Ohlrogge AW, et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2018;138:271–81. [CrossRef]

- Kharroubi AT. Diabetes mellitus: The epidemic of the century. World J Diabetes 2015;6:850. [CrossRef]

- Raveendran A V., Chacko EC, Pappachan JM. Non-pharmacological treatment options in the management of diabetes mellitus. Eur Endocrinol 2020;14:31–9. [CrossRef]

- MacLean CD, Littenberg B, Kennedy AG. Limitations of diabetes pharmacotherapy: Results from the Vermont Diabetes Information System study. BMC Fam Pract 2006;7. [CrossRef]

- Egan AM, Dinneen SF. What is diabetes? Medicine (United Kingdom) 2019;47:1–4. [CrossRef]

- Herath L, Kamalsiri M, Inthuja P, Gamage GP, Vidanage D. Non-pharmacological Methods Used in the Management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus by a Selected Group of People with T2DM in Colombo District, Sri Lanka: A Mixed-Method Study. Journal of Diabetology 2024;15:165–72. [CrossRef]

- Wei S, Li C, Wang Z, Chen Y. Nutritional strategies for intervention of diabetes and improvement of β-cell function. Biosci Rep 2023;43. [CrossRef]

- Padma V. DASH Diet in Preventing Hypertension. Adv Biol Res (Rennes) 2014;8:94–6. [CrossRef]

- Esposito K, Giugliano D. Mediterranean diet and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2014;30:34–40. [CrossRef]

- Toi PL, Anothaisintawee T, Chaikledkaew U, Briones JR, Reutrakul S, Thakkinstian A. Preventive role of diet interventions and dietary factors in type 2 diabetes mellitus: An umbrella review. Nutrients 2020;12:1–17. [CrossRef]

- Subhan FB, Fernando DN, Thorlakson J, Chan CB. Dietary Interventions for Type 2 Diabetes in South Asian Populations—A Systematic Review. Curr Nutr Rep 2023;12:39–55. [CrossRef]

- Effect of diet on type 2 diabetes mellitus: A review Introduction. n.d.

- McMacken M, Shah S. A plant-based diet for the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes. Journal of Geriatric Cardiology 2017;14:342–54. [CrossRef]

- Grundy SM. Dietary Therapy in Diabetes Mellitus Is There a Single Best Diet? n.d.

- Diabetes Diagnosis & Tests | ADA n.d. https://diabetes.org/about-diabetes/diagnosis (accessed May 18, 2025).

- Hinderliter AL, Babyak MA, Sherwood A, Blumenthal JA. The DASH diet and insulin sensitivity. Curr Hypertens Rep 2011;13:67–73. [CrossRef]

- Duncan AD, Peters BS, Rivas C, Goff LM. Reducing risk of Type 2 diabetes in HIV: a mixed-methods investigation of the STOP-Diabetes diet and physical activity intervention. Diabetic Medicine 2020;37:1705–14. [CrossRef]

- Chen L, Liu B, Ren L, Du H, Fei C, Qian C, et al. High-fiber diet ameliorates gut microbiota, serum metabolism and emotional mood in type 2 diabetes patients. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2023;13. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Hu Y, Qin LQ, Dong JY. Meal frequency and incidence of type 2 diabetes: A prospective study. British Journal of Nutrition 2022;128:273–8. [CrossRef]

- Burr JF, Rowan CP, Jamnik VK, Riddell MC. The role of physical activity in type 2 diabetes prevention: Physiological and practical perspectives. Physician and Sportsmedicine 2010;38:72–82. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong MEG, Green J, Reeves GK, Beral V, Cairns BJ. Frequent physical activity may not reduce vascular disease risk as much as moderate activity: Large prospective study of women in the United Kingdom. Circulation 2015;131:721–9. [CrossRef]

- Kirwan JP, Sacks J, Nieuwoudt S. The essential role of exercise in the management of type 2 diabetes. Cleve Clin J Med 2017;84:S15–21. [CrossRef]

- Mann S, Beedie C, Jimenez A. Differential effects of aerobic exercise, resistance training and combined exercise modalities on cholesterol and the lipid profile: review, synthesis and recommendations. Sports Medicine 2014;44:211–21. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwala J, Sharma S, Jain A, Sarkar A. Effects of aerobic exercise on blood glucose levels and lipid profile in Diabetes Mellitus type 2 subjects. 2016.

- Yardley JE, Kenny GP, Perkins BA, Riddell MC, Balaa N, Malcolm J, et al. Resistance versus aerobic exercise. Diabetes Care 2013;36:537–42. [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo AP, Ibrahimli S, Castells J, Jaramillo L, Moncada D, Revilla Huerta JC. Physical Activity as a Lifestyle Modification in Patients With Multiple Comorbidities: Emphasizing More on Obese, Prediabetic, and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients. Cureus 2023. [CrossRef]

- Savikj M, Zierath JR. Train like an athlete: applying exercise interventions to manage type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2020;63:1491–9. [CrossRef]

- Yang Z, Scott CA, Mao C, Tang J, Farmer AJ. Resistance exercise versus aerobic exercise for type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine 2014;44:487–99. [CrossRef]

- Burr JF, Rowan CP, Jamnik VK, Riddell MC. The role of physical activity in type 2 diabetes prevention: Physiological and practical perspectives. Physician and Sportsmedicine 2010;38:72–82. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt CB, van Loon BJP, Vergouwen ACM, Snoek FJ, Honig A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological interventions in people with diabetes and elevated diabetes-distress. Diabetic Medicine 2018;35:1157–72. [CrossRef]

- Exploring the role of CBT in the self-management of type 2 diabetes n.d.

- Abbas Q, Latif S, Ayaz Habib H, Shahzad S, Sarwar U, Shahzadi M, et al. Cognitive behavior therapy for diabetes distress, depression, health anxiety, quality of life and treatment adherence among patients with type-II diabetes mellitus: a randomized control trial. BMC Psychiatry 2023;23. [CrossRef]

- Sayadi AR, Seyed Bagheri SH, Khodadadi A, Jafari Torababadi R. The effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) training on serum cortisol levels, depression, stress, and anxiety in type 2 diabetic older adults during the COVID-19 outbreak. J Med Life 2022;15:1493–501. [CrossRef]

- Fisher V, Li WW, Malabu U. The effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on the mental health, HbA1C, and mindfulness of diabetes patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Appl Psychol Health Well Being 2023;15:1733–49. [CrossRef]

- Zhang H, Goldberg SI, Hosomura N, Shubina M, Simonson DC, Testa MA, et al. Lifestyle counseling and long-term clinical outcomes in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care 2019;42:1833–6. [CrossRef]

- Godwin IU, Atulomah N. Effect of Lifestyle Modification Intervention on Diabetes Mellitus Treatment Outcomes in Tuberculosis Patients with Diabetes Mellitus in Southwest Nigeria. Texila International Journal of Public Health 2023;11. [CrossRef]

- Chew B-H. Psychological aspects of diabetes care: Effecting behavioral change in patients. World J Diabetes 2014;5:796. [CrossRef]

- Uly N, Fadli F, Iskandar R. Relationship between Self-Care Behavior and Diabetes Self-Management Education in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus Type 2. Open Access Maced J Med Sci 2022;10:1648–51. [CrossRef]

- Puspasari S, Imam Hardiansyah C, Nurdina G, Permana S, Antika Rizki Kusuma Putri T. Edukasi Berbasis Self Management untuk Meningkatkan Self Care pada Diabetes Mellitus Tipe 2. Address : Jl Ahmad n.d.;4. [CrossRef]

- Wascher TC, Stechemesser L, Harreiter J. Blood glucose self monitoring. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2023;135:143–6. [CrossRef]

- Kesavadev J, Mohan V. A Multidisciplinary Reviews Journal Reducing the Cost of Diabetes Care with Telemedicine, Smartphone, and Home Monitoring. JournalIiscErnet.in J Indian Inst Sci 2023;103:1–231.

- Amante DJ, Harlan DM, Lemon SC, McManus DD, Olaitan OO, Pagoto SL, et al. Evaluation of a diabetes remote monitoring program facilitated by connected glucose meters for patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes: Randomized crossover trial. JMIR Diabetes 2021;6. [CrossRef]

- Souza VP de, Dos Santos ECB, Angelim RC de M, Teixeira CR de S, Martins RD. Knowledge and Practices of Users With Diabetes Mellitus on Capillary Blood Glucose Self-Monitoring at Home / Conhecimento e Práticas de Usuários com Diabetes Mellitus Sobre a Automonitorização da Glicemia Capilar no Domicilio. Revista de Pesquisa Cuidado é Fundamental Online 2018;10:737–45. [CrossRef]

- Wharton S, Costanian C, Gershon T, Christensen RAG. Obesity and Diabetes. The Diabetes Textbook, Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019, p. 597–610. [CrossRef]

- the University of Texas-Houston Health Science Center, Houston; and the San Antonio Co-i-hv. vol. 19. 1996.

- Hamman RF, Wing RR, Edelstein SL, Lachin JM, Bray GA, Delahanty L, et al. Effect of weight loss with lifestyle intervention on risk of diabetes. Diabetes Care 2006;29:2102–7. [CrossRef]

- Al-Goblan AS, Al-Alfi MA, Khan MZ. Mechanism linking diabetes mellitus and obesity. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity 2014;7:587–91. [CrossRef]

- Kumar BH. International Journal of Biomedical Research Relation between Type 2 Diabetes and obesity: A review n.d. [CrossRef]

- Serván PR. Obesity and Diabetes. Nutr Hosp 2013;28:138–43.

- Obesity and diabetes n.d.

- Lau DCW, Teoh H. Benefits of Modest Weight Loss on the Management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Can J Diabetes 2013;37:128–34. [CrossRef]

- Logan JE, Prévost M, Brazeau A-S, Hart S, Maldaner M, Scrase S, et al. The Impact of Gender on Physical Activity Preferences and Barriers in Adults with Type 1 Diabetes: A Qualitative Study. Can J Diabetes 2024. [CrossRef]

- Magri CJ, Xuereb S, Xuereb R-A, Xuereb RG, Fava S, Galea J. Sleep measures and cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clinical Medicine 2023:clinmed2022-0442. [CrossRef]

- Jang J ha, Kim W, Moon JS, Roh E, Kang JG, Lee SJ, et al. Association between Sleep Duration and Incident Diabetes Mellitus in Healthy Subjects: A 14-Year Longitudinal Cohort Study. J Clin Med 2023;12. [CrossRef]

- Alwi F, Leli Herawati, Hizrah Hanim Lubis, Mersi Ekaputri, Razyda Hayati. Quality of Sleep and Blood Glucose of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. International Journal of Public Health Excellence (IJPHE) 2023;2:574–7. [CrossRef]

- Khamchet S, Buawangpong N, Pinyopornpanish K, Nantsupawat T, Angkurawaranon C, Choksomngam Y, et al. Sleep Quality and Associated Factors in Elderly Patients with Type-2 Diabetes Mellitus. Siriraj Med J 2023;75:392–8. [CrossRef]

- MaryMinolin T, Divya S. Assess the Association between Sleep quality and Glycemic control among patients with diabetes mellitus. CARDIOMETRY 2023:226–30. [CrossRef]

- Dare S, Mackay DF, Pell JP. Relationship between smoking and obesity: A cross-sectional study of 499,504 middle-aged adults in the UK general population. PLoS One 2015;10. [CrossRef]

- Farhoodi I, Parsay S, Hekmatfar S, Musavi S, Mortazavi Z. Effect of Cigarette Smoking on Periodontal Status of Diabetic Patients. Avicenna Journal of Dental Research 2021;13:62–6. [CrossRef]

- Nkomo NY, Simo-Kengne BD, Biyase M. Maternal tobacco smoking and childhood obesity in South Africa: A cohort study. PLoS One 2023;18. [CrossRef]

- Chao AM, Wadden TA, Ashare RL, Loughead J, Schmidt HD. Tobacco Smoking, Eating Behaviors, and Body Weight: a Review. Curr Addict Rep 2019;6:191–9. [CrossRef]

- Tuovinen EL, Saarni SE, Männistö S, Borodulin K, Patja K, Kinnunen TH, et al. Smoking status and abdominal obesity among normal- and overweight/obese adults: Population-based FINRISK study. Prev Med Rep 2016;4:324–30. [CrossRef]

- Miyamura K, Nawa N, Isumi A, Doi S, Ochi M, Fujiwara T. Impact of exposure to secondhand smoke on the risk of obesity in early adolescence. Pediatr Res 2023;93:260–6. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed Ali M, Helou M, Al-Sayed Ahmad M, Al Ali R, Damiri B. Risk of Tobacco Smoking and Consumption of Energy Drinks on Obesity and Central Obesity Among Male University Students. Cureus 2022. [CrossRef]

- Freedman DM, Sigurdson AJ, Rajaraman P, Doody MM, Linet MS, Ron E. The Mortality Risk of Smoking and Obesity Combined. Am J Prev Med 2006;31:355–62. [CrossRef]

- Suutari-Jääskö A, Ylitalo A, Ronkaine J, Huikuri H, Kesäniemi YA, Ukkola OH. Smoking cessation and obesity-related morbidities and mortality in a 20-year followup study. PLoS One 2022;17. [CrossRef]

- the-relationship-between-alcohol-consumption-body-mass-index-430ki2u0zb n.d.

- Song J, Lin WQ. Association between alcohol consumption and incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus in Japanese men: a secondary analysis of a Retrospective Cohort Study. BMC Endocr Disord 2023;23. [CrossRef]

- Howard AA, Arnsten JH, Gourevitch MN. Effect of Alcohol Consumption on Diabetes Mellitus A Systematic Review Background: Both diabetes mellitus and alcohol consumption. 2004.

- Polsky S, Akturk HK. Alcohol Consumption, Diabetes Risk, and Cardiovascular Disease Within Diabetes. Curr Diab Rep 2017;17. [CrossRef]

- Koppes LLJ, Dekker JM, Hendriks HFJ, Bouter LM, Heine RJ. Moderate Alcohol Consumption Lowers the Risk of Type 2 Diabetes A meta-analysis of prospective observational studies From the. vol. 28. 2005.

- Chen C, Sun Z, Xu W, Tan J, Li D, Wu Y, et al. Associations between alcohol intake and diabetic retinopathy risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Endocr Disord 2020;20. [CrossRef]

- Carlsson S, Hammar N, Grill V, Kaprio J. Alcohol Consumption and the Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes A 20-year follow-up of the Finnish Twin Cohort Study. 2003.

- Beulens JWJ, Stolk RP, Van Der Schouw YT, Grobbee DE, Hendriks HFJ, Bots ML. Alcohol Consumption and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes Among Older Women. 2005.

- Kim SJ, Kim DJ. Alcoholism and diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab J 2012;36:108–15. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).