Submitted:

19 December 2025

Posted:

22 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of P(EDOT-co-Py)@MWCNT Hybrid

2.2. Material Characterization

2.3. Preparation of the Electrodes

2.4. Electrochemical Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

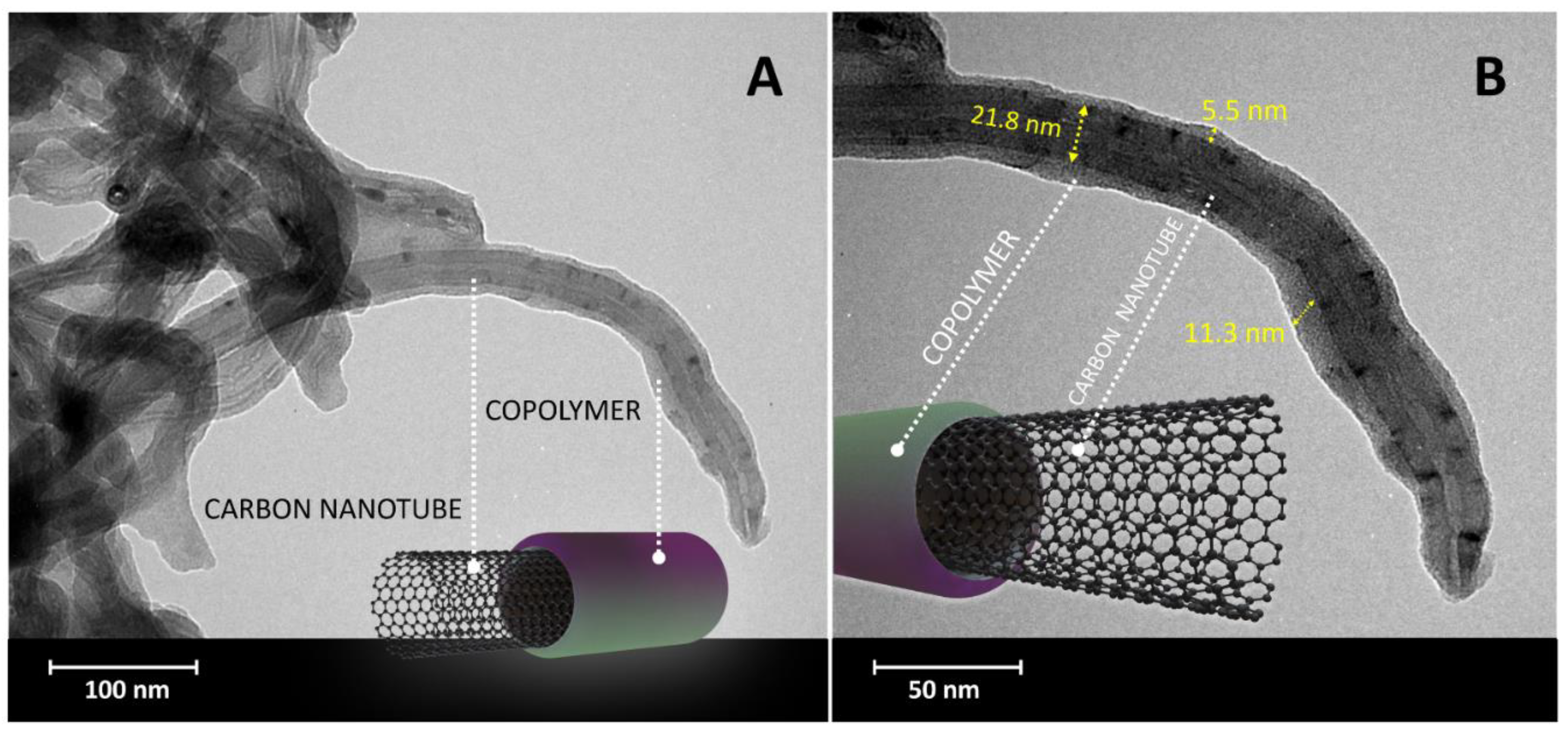

3.1. Material Characterization

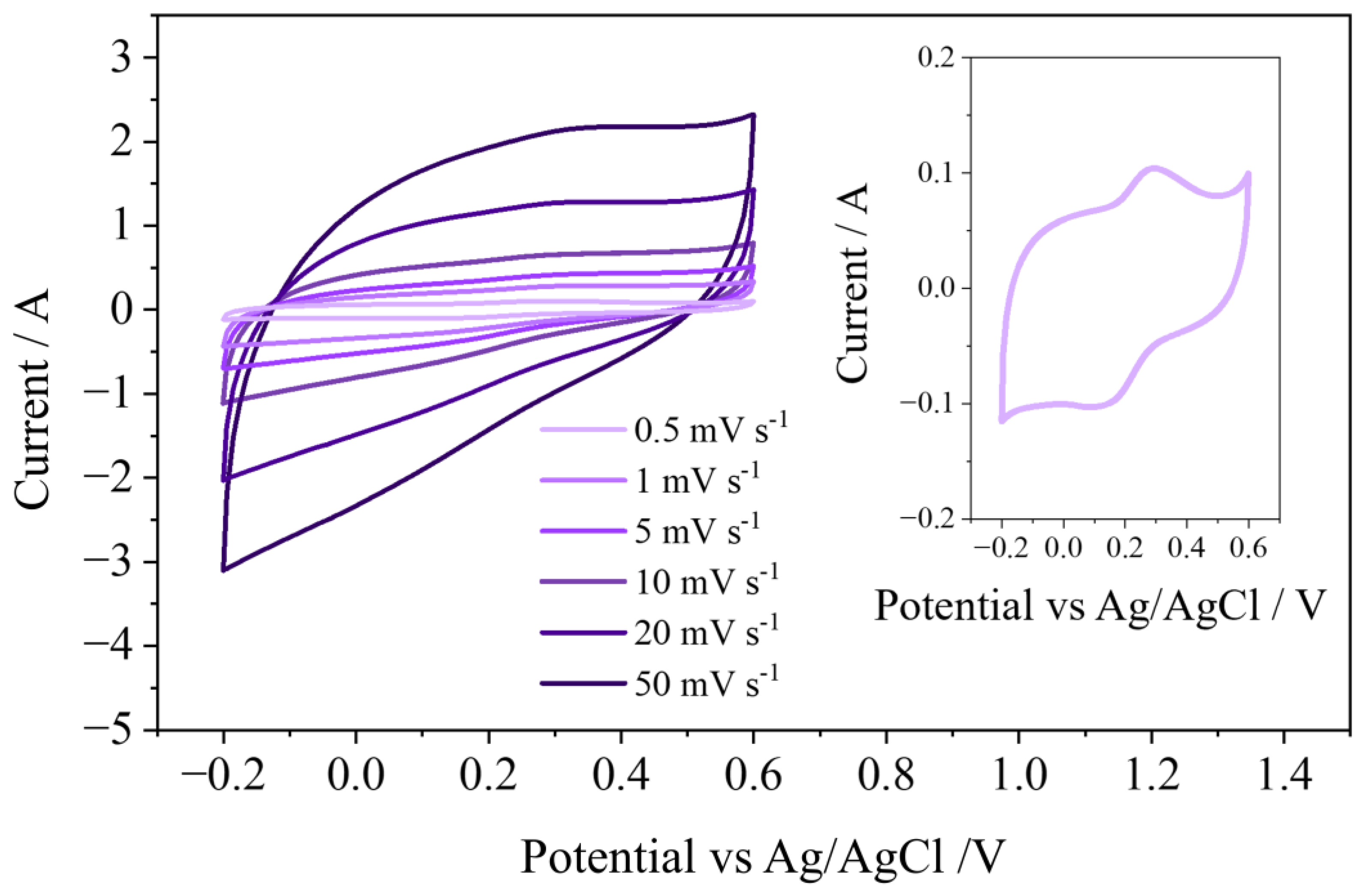

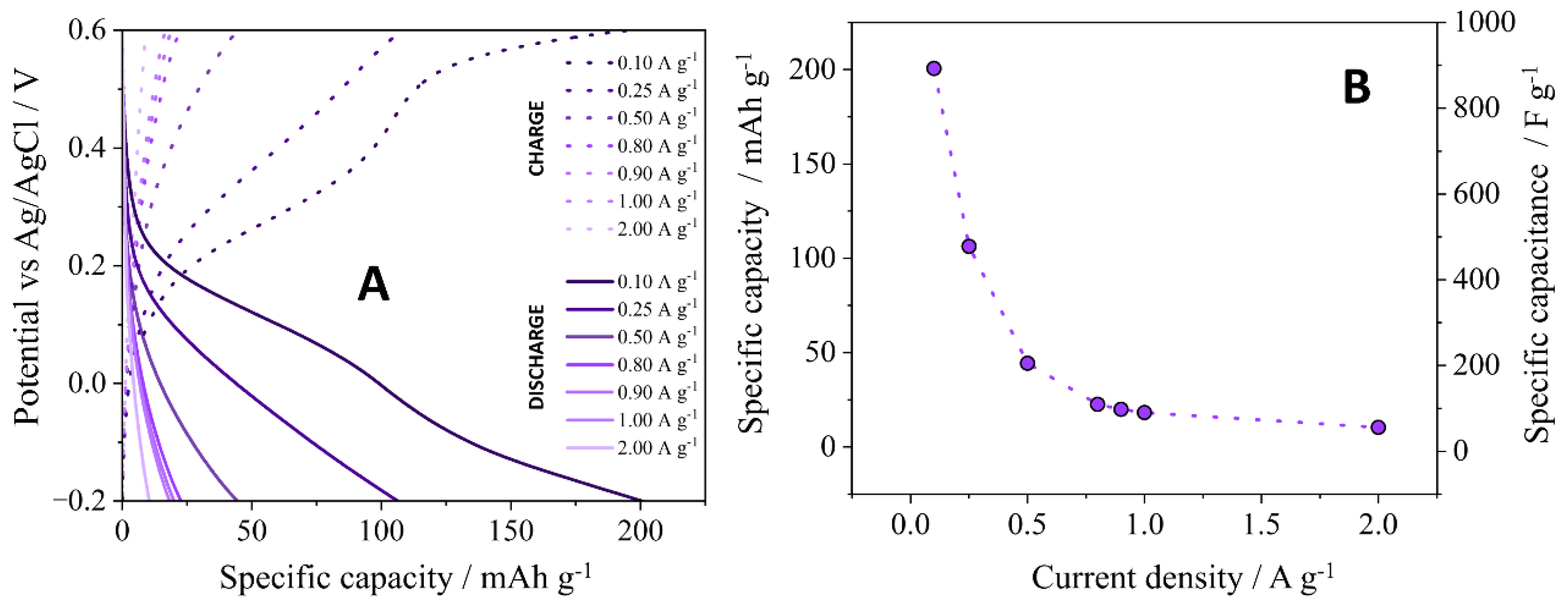

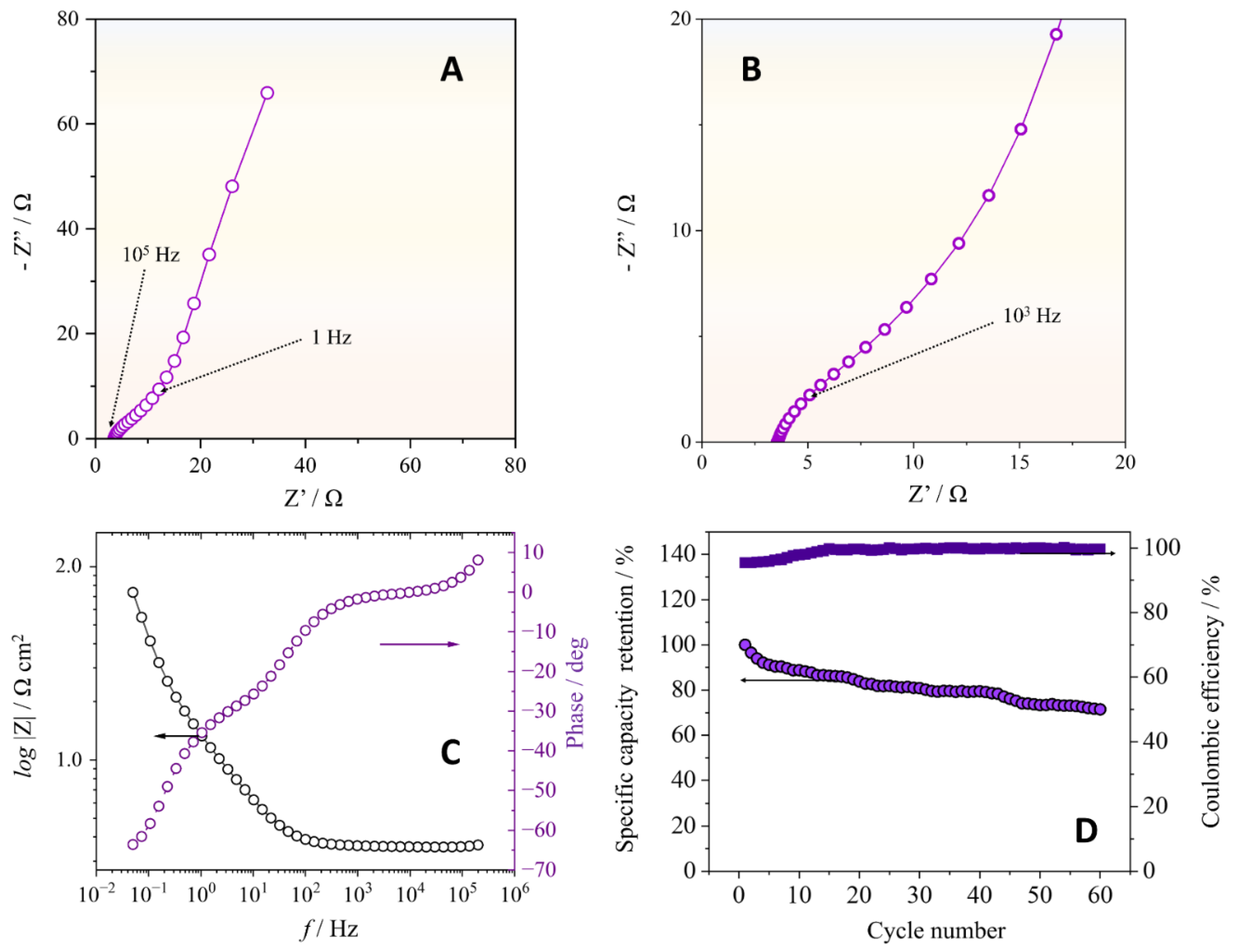

3.2. Electrochemical Characterization

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EDOT | 3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene |

| Py | pyrrole |

| MWCNT | multi-walled carbon nanotubes |

| TGA | thermogravimetric analysis |

| FTIR | Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy |

| XPS | X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy |

| TEM | transmission electron microscopy |

| P(EDOT-co-Py)@MWCNT hybrid | (poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene-co-pyrrol)@MWCNT hybrid |

| LIBs | lithium-ion batteries |

| AIBs | aluminum-ion batteries |

| AISCs | aluminum-ion supercapacitors |

| PBAs | Prussian Blue Analogues |

| CP | conducting polymer |

| PSS | poly(4-styrenesulfonate |

| PAc | polyacetylene |

| PANI | polyaniline |

| PPP | poly(p-phenylene) |

| PPV | poly(p-phenylenevinylene), |

| PTh | polythiophene |

| CNTs | carbon nanotubes |

| SWCNTs | single-walled carbon nanotubes |

| AlCl3–[EMIm]Cl | 1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride-aluminum chloride |

| (P(EDOT-co-PyMP) | poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene-co-3-(pyrrol-1-methyl)pyridine) |

| (P(EDOT-co-MPy) | poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene-co-methylpyrrole) |

| CV | cyclic voltammetry |

| GCD | galvanostatic charge–discharge |

| EIS | electrochemical impedance spectroscopy |

| DAP | 1,3-diaminopropane |

| TCC | 3-thiophene carbonyl chloride |

| PTFE | Polytetrafluoroethylene |

| NMP | N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone |

| PVDF | polyvinylidene fluoride |

| Csp | Specific capacitance |

| Esp | energy density |

| Psp | power density |

| ε | coulombic efficiency |

| I | applied current, |

| t | time |

| V | potential, |

| m | active mass of the electrode |

| Vdischarge | is the maximum potential at the end of the discharge, after the ohmic drop |

| dTG | thermogravimetric derivative |

References

- Kazazi, M.; Abdollahi, P.; Mirzaei-Moghadam, M. High surface area TiO2 nanospheres as a high-rate anode material for aqueous aluminium-ion batteries. Solid State Ionics 2017, 300, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacin, M.R.; Johansson, P.; Dominko, R.; Dlugatch, B.; Aurbach, D.; Li, Z.; Fichtner, M.; Lužanin, O.; Bitenc, J.; Wei, Z.; Glaser, C.; Janek, J.; Fernández-Barquín, A.; Mainar, A.R.; Leonet, O.; Urdampilleta, I.; Blázquez, J.A.; Tchitchekova, D.S.; Ponrouch, A.; Canepa, P.; Gautam, G.S.; Casilda, R.S.R.G.; Martinez-Cisneros, C.S.; Torres, N.U.; Varez, A.; Sanchez, J.-Y.; Kravchyk, K.V.; Kovalenko, M.V.; Teck, A.A.; Shiel, H.; Stephens, I.E.L.; Ryan, M.P.; Zemlyanushin, E.; Dsoke, S.; Grieco, R.; Patil, N.; Marcilla, R.; Gao, X.; Carmalt, C.J.; He, G.; Titirici, M.-M. Roadmap on multivalent batteries. J. Phys. Energy 2024, 6, 031501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melzack, N.; Wills, R.G.A. A Review of Energy Storage Mechanisms in Aqueous Aluminium Technology. Front. Chem. Eng. 2022, 4, 778265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.K.X.; Paul, S. Beyond Lithium: Future Battery Technologies for Sustainable Energy Storage. Energies 2024, 17, 5768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Shao, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Kaner, R.B. Aluminum-Ion-Intercalation Supercapacitors with Ultrahigh Areal Capacitance and Highly Enhanced Cycling Stability: Power Supply for Flexible Electrochromic Devices. Small 2017, 13, 1700380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Zhao, Y.; Mao, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Leong, K.W.; Luo, S.; Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Xuan, J.; Yang, S.; Chen, Y.; Leung, D.Y.C. High-Energy SWCNT Cathode for Aqueous Al-Ion Battery Boosted by Multi-Ion Intercalation Chemistry. Advanced Energy Materials 2011, 11, 2101514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, Z.A.; Imtiaz, S.; Razaq, R.; Ji, S.; Huang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Anderson, J.A. Cathode materials for rechargeable aluminum batteries: current status and progress. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 5646–5660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Pan, G.L.; Li, G.R.; Gao, X.P. Copper hexacyanoferrate nanoparticles as cathode material for aqueous Al-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 959–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Li, H.; Fu, T.; Hwang, B.-J.; Li, X.; Zhao, J. One-Dimensional Cu 2– x Se Nanorods as the Cathode Material for High-Performance Aluminum-Ion Battery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 17942–17949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Jiang, B.; Xiong, W.; Sun, H.; Lin, Z.; Hu, L.; Tu, J.; Hou, J.; Zhu, H.; Jiao, S. A new cathode material for super-valent battery based on aluminium ion intercalation and deintercalation. Sci Rep 2013, 3, 3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, J.; Fernando, J.F.S.; Sayeed, M.A.; Tang, C.; Golberg, D.; Du, A.; Ostrikov, K. (Ken); O’Mullane, A.P. Exploring Aluminum-Ion Insertion into Magnesium-Doped Manjiroite (MnO2 ) Nanorods in Aqueous Solution. ChemElectroChem 2021, 8, 1048–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legein, C.; Morgan, B.J.; Fayon, F.; Koketsu, T.; Ma, J.; Body, M.; Sarou-Kanian, V.; Wei, X.; Heggen, M.; Borkiewicz, O.J.; Strasser, P.; Dambournet, D. Atomic Insights into Aluminium-Ion Insertion in Defective Anatase for Batteries. Angew Chem Int Ed 2020, 59, 19247–19253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nacimiento, F.; Cabello, M.; Alcántara, R.; Lavela, P.; Tirado, J.L. NASICON-type Na3V2(PO4)3 as a new positive electrode material for rechargeable aluminium battery. Electrochimica Acta 2018, 260, 798–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, R.; Lan, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Ling, H.; Zhang, F.; Zhi, C.; Bai, X.; Wang, W. Reversible Intercalation of Al-Ions in Poly(3,4-Ethylenedioxythiophene):Poly(4-Styrenesulfonate) Electrode for Aqueous Electrochemical Capacitors with High Energy Density. Energy Tech 2021, 9, 2001036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Gu, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhu, B.; Liu, Y.; Fu, Y.; Shi, J.; Tang, W. High-rate and long-cycle sodium dual-ion batteries via extended π-conjugated polymer for −45-60 °C operation. Chemical Engineering Journal 2025, 520, 166152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinayak, V.J. Vipu; Deshmukh, K.; Murthy, V.R.K.; Pasha, S.K.K. Conducting polymer based nanocomposites for supercapacitor applications: A review of recent advances, challenges and future prospects. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 100, 113551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavan, U.D.; Prajith, P.; Kandasubramanian, B. Polypyrrole based cathode material for battery application. Chemical Engineering Journal Advances 2022, 12, 100416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meer, S.; Kausar, A.; Iqbal, T. Trends in Conducting Polymer and Hybrids of Conducting Polymer/Carbon Nanotube: A Review. Polymer-Plastics Technology and Engineering 2016, 55, 1416–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Shi, Y.; Yin, B.; Wen, H.; Li, H.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Ma, T. Conductive polymer networks: enabling high-performance zinc-ion batteries via dual-ion storage mechanism and structural suppression. Applied Surface Science 2025, 713, 164351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groenendaal, L.; Jonas, F.; Freitag, D.; Pielartzik, H.; Reynolds, J.R. Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) and Its Derivatives: Past, Present, and Future. Adv. Mater. 2000, 12, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, K.D.; Wang, T.; Smoukov, S.K. Multidimensional performance optimization of conducting polymer-based supercapacitor electrodes. Sustainable Energy Fuels 2017, 1, 1857–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wu, J.; Ran, F. Poly(3, 4-Ethylenedioxythiophene) as Promising Energy Storage Materials in Zinc-Ion Batteries. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2024, 45, 2400476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallaev, R. Conductive Polymer Thin Films for Energy Storage and Conversion: Supercapacitors, Batteries, and Solar Cells. Polymers 2025, 17, 2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadac, K.; Nowaczyk, A.; Nowaczyk, J. Synthesis and characterization of new copolymer of pyrrole and 3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene synthesized by electrochemical route. Synthetic Metals 2015, 206, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodský, J.; Migliaccio, L.; Sahalianov, I.; Zítka, O.; Neužil, P.; Gablech, I. Advancements in PEDOT-based electrochemical sensors for water quality monitoring: From synthesis to applications. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2025, 183, 118115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Chen, X.; Huang, J.; Jiang, H.; Chen, W.; Chen, Y. Molecular size matching of dopant in polypyrrole and anion in dual-ion battery enhancing the energy storage ability and dynamics of polypyrrole cathode. Chemical Engineering Journal 2025, 510, 161471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, M.; Pei, Z.; Xue, Q.; Huang, Y.; Zhi, C. Nanostructured Polypyrrole as a flexible electrode material of supercapacitor. Nano Energy 2016, 22, 422–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.Z. Understanding supercapacitors based on nano-hybrid materials with interfacial conjugation. Progress in Natural Science: Materials International 2013, 23, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanmugam, A.; Vanitha, C.; Almansour, A.I.; Karuppasamy, K.; Maiyalagan, T.; Kim, H.-S.; Vikraman, D.; Alfantazi, A. Unveiling the PEDOT-polypyrrole hybrid electrode for the electrochemical sensing of dopamine. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 10989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, T.; Liu, P.; Zhang, J.; Xu, J.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, P.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Lu, X.; Wen, Y. Multiwalled Carbon Nanotube-N-Doped Graphene/Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):Poly(styrenesulfonate) Nanohybrid for Electrochemical Application in Intelligent Sensors and Supercapacitors. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 28452–28462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacerda, G.R.D.B.S.; Dos Santos Junior, G.A.; Rocco, M.L.M.; Lavall, R.L.; Matencio, T.; Calado, H.D.R. Development of a new hybrid CNT-TEPA@poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene-co-3-(pyrrol-1-methyl)pyridine) for application as electrode active material in supercapacitors. Polymer 2020, 194, 122368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nong, J.; Glassman, P.M.; Shuvaev, V.V.; Reyes-Esteves, S.; Descamps, H.C.; Kiseleva, R.Y.; Papp, T.E.; Alameh, M.-G.; Tam, Y.K.; Mui, B.L.; Omo-Lamai, S.; Zamora, M.E.; Shuvaeva, T.; Arguiri, E.; Gong, X.; Brysgel, T.V.; Tan, A.W.; Woolfork, A.G.; Weljie, A.; Thaiss, C.A.; Myerson, J.W.; Weissman, D.; Kasner, S.E.; Parhiz, H.; Muzykantov, V.R.; Brenner, J.S.; Marcos-Contreras, O.A. Targeting lipid nanoparticles to the blood-brain barrier to ameliorate acute ischemic stroke. Molecular Therapy 2024, 32, 1344–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bramnik, N.; Roy, S.; Di Benedetto, G.; Zunino, J.L.; Mitra, S. Flexible zinc–carbon batteries with multiwalled carbon nanotube/conductive polymer cathode matrix. Journal of Power Sources 2013, 237, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Cai, K.; Chen, Y.; Chen, L. Research progress on conducting polymer based supercapacitor electrode materials. Nano Energy 2017, 36, 268–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, A.S.; Varghese, S.M.; Rakhi, R.B.; Peethambharan, S.K. Synergistic effect of solvent addition and temperature treatment on conductivity enhancement of MWCNTs: PEDOT:PSS composite ink for electrodes in all printed solid-state micro-supercapacitors. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 495, 153495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, H.; Wang, J.; Tu, J.; Lei, H.; Jiao, S. Aluminum-Ion Asymmetric Supercapacitor Incorporating Carbon Nanotubes and an Ionic Liquid Electrolyte: Al/AlCl3 -[EMIm]Cl/CNTs. Energy Tech 2016, 4, 1112–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Yin, J.; Zhao, M.; Xie, D.; Xie, K.; Cui, Y.; Li, Q.; Li, C. Polypyrrole @ carbon nanotube as a long-life positive electrode for aluminum-ion batteries. Materials Letters 2025, 390, 138398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacerda, G.R.D.B.S.; Dos Santos Junior, G.A.; Rocco, M.L.M.; Lavall, R.L.; Matencio, T.; Calado, H.D.R. Development of nanohybrids based on carbon nanotubes/P(EDOT-co-MPy) and P(EDOT-co-PyMP) copolymers as electrode materials for aqueous supercapacitors. Electrochimica Acta 2020, 335, 135637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerrard, W.; Thrush, M. Reactions in Carboxylic Acid-Thionyl Chloride Systems. J. Chem. Soc 1953, 2117–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Chau, M.T.; Thao, P.T.B.; Nhan, L.T. Near-electrode effects of ferroelectric nanocomposites filled with pristine and oxidized multiwalled carbon nanotubes at low frequencies. Ferroelectrics 2023, 602, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šolić, M.; Maletić, S.; Isakovski, M.K.; Nikić, J.; Watson, M.; Kónya, Z.; Rončević, S. Removing low levels of Cd(II) and Pb(II) by adsorption on two types of oxidized multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2021, 9, 105402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Song, M.; Li, T.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, A. Water-soluble carboxymethyl chitosan (WSCC)-modified single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) provide efficient adsorption of Pb(ii) from water. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 6821–6830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimi, K.; Riahi, S.; Abbasi, M.; Fakhroueian, Z. Modification of multi-walled carbon nanotubes by 1,3-diaminopropane to increase CO2 adsorption capacity. Journal of Environmental Management 2019, 242, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirmiran, T.S.; Riahi, S.; Abbasi, M.; Mohammadi-Khanaposhtani, M. Synergistic improvement of CO2 adsorption using functionalized MWCNTs by a simultaneous combination of two amines. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2025, 13, 119213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Jamal, R.; Zhang, L.; Wang, M.; Abdiryim, T. The structure and properties of PEDOT synthesized by template-free solution method. Nanoscale Res Lett 2014, 9, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Zhou, W.; Ma, X.; Chen, S.; Ming, S.; Lin, K.; Lu, B.; Xu, J. Capacitive performance of electrodeposited PEDOS and a comparative study with PEDOT. Electrochimica Acta 2016, 220, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewidy, D.; Gadallah, A.-S.; Fattah, G.A. Electroluminescence enhancement of glass/ITO/PEDOT:PSS/MEH-PPV/PEDOT:PSS/Al OLED by thermal annealing. Journal of Molecular Structure 2017, 1130, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Sun, X.; Liu, D.; Liu, X.; Du, X.; Li, S.; Xing, X.; Cheng, X.; Bi, D.; Qiu, D. Facile Synthesis of Novel Conducting Copolymers Based on N-Furfuryl Pyrrole and 3,4-Ethylenedioxythiophene with Enhanced Optoelectrochemical Performances Towards Electrochromic Application. Molecules 2024, 30, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Alam, I.; Hossen, M.R.; Azim, F.; Anjum, N.; Faruk, M.O.; Rahman, M.M.; Okoli, O.I. Facile Synthesis of Conductive Copolymers and Its Supercapacitor Application. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Cartagena, M.E.; Bernal-Martínez, J.; Banda-Villanueva, A.; Magaña, I.; Córdova, T.; Ledezma-Pérez, A.; Fernández-Tavizón, S.; Díaz De León, R. A Comparative Study of Biomimetic Synthesis of EDOT-Pyrrole and EDOT-Aniline Copolymers by Peroxidase-like Catalysts: Towards Tunable Semiconductive Organic Materials. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 915264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Odayni, A.-B.; Alsubaie, F.S.; Abdu, N.A.Y.; Al-Kahtani, H.M.; Saeed, W.S. Adsorption Kinetics of Methyl Orange from Model Polluted Water onto N-Doped Activated Carbons Prepared from N-Containing Polymers. Polymers 2023, 15, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman Khan, M.M.; Islam, M.; Amin, Md.K.; Paul, S.K.; Rahman, S.; Talukder, Md.M.; Rahman, Md.M. Simplistic fabrication of aniline and pyrrole-based poly(Ani-co-Py) for efficient photocatalytic performance and supercapacitors. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 37860–37869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-García, F.; Canché-Escamilla, G.; Ocampo-Flores, A.L.; Roquero-Tejeda, P.; Ordóñez, L.C. Controlled Size Nano-Polypyrrole Synthetized in Micro-Emulsions as Pt Support for the Ethanol Electro-Oxidation Reaction. International Journal of Electrochemical Science 2013, 8, 3794–3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasupuleti, K.S.; Bak, N.-H.; Peta, K.R.; Kim, S.-G.; Cho, H.D.; Kim, M.-D. Enhanced sensitivity of langasite-based surface acoustic wave CO gas sensor using highly porous Ppy@PEDOT:PSS hybrid nanocomposite. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2022, 363, 131786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarac, A.S.; Nmez, G.S.; Cebeci, F.C. Electrochemical synthesis and structural studies of polypyrroles, poly(3,4-ethylene-dioxythiophene)s and copolymers of pyrrole and 3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene on carbon fibre microelectrodes. j. of Applied Electrochemistry 2003, 33, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Li, M.; Wang, D.; Zhou, S.; Peng, C. Interfacial Synthesis of Free-Standing Asymmetrical PPY-PEDOT Copolymer Film with 3D Network Structure for Supercapacitors. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 164, A1820–A1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.F.; Zhang, L.; Peng, H.; Travas-Sejdic, J.; Kilmartin, P.A. Free radical scavenging properties of polypyrrole and poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene). Current Applied Physics 2008, 8, 316–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulandaivalu, S.; Zainal, Z.; Sulaiman, Y. Influence of Monomer Concentration on the Morphologies and Electrochemical Properties of PEDOT, PANI, and PPy Prepared from Aqueous Solution. International Journal of Polymer Science 2016, 2016, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Cartagena, M.E.; Bernal-Martínez, J.; Banda-Villanueva, A.; Magaña, I.; Córdova, T.; Ledezma-Pérez, A.; Fernández-Tavizón, S.; Díaz De León, R. A Comparative Study of Biomimetic Synthesis of EDOT-Pyrrole and EDOT-Aniline Copolymers by Peroxidase-like Catalysts: Towards Tunable Semiconductive Organic Materials. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 915264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radhakrishnan, S.; Sumathi, C.; Umar, A.; Jae Kim, S.; Wilson, J.; Dharuman, V. Polypyrrole–poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)–Ag (PPy–PEDOT–Ag) nanocomposite films for label-free electrochemical DNA sensing. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2013, 47, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lay, M.; Pèlach, M.À.; Pellicer, N.; Tarrés, J.A.; Bun, K.N.; Vilaseca, F. Smart nanopaper based on cellulose nanofibers with hybrid PEDOT:PSS/polypyrrole for energy storage devices. Carbohydrate Polymers 2017, 165, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brachetti-Sibaja, S.B.; Palma-Ramírez, D.; Torres-Huerta, A.M.; Domínguez-Crespo, M.A.; Dorantes-Rosales, H.J.; Rodríguez-Salazar, A.E.; Ramírez-Meneses, E. CVD Conditions for MWCNTs Production and Their Effects on the Optical and Electrical Properties of PPy/MWCNTs, PANI/MWCNTs Nanocomposites by In Situ Electropolymerization. Polymers 2021, 13, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vellingiri, L.; Annamalai, K.; Kandasamy, R.; Kombiah, I. Characterization and hydrogen storage properties of SnO2 functionalized MWCNT nanocomposites. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 10396–10409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanheiro, T.L.D.A.; Cristóvan, F.H.; Machado, J.P.B.; Tada, D.B.; Durán, N.; Lemes, A.P. Effect of MWCNT functionalization on thermal and electrical properties of PHBV/MWCNT nanocomposites. J. Mater. Res. 2015, 30, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, E.R.; Oishi, S.S.; Botelho, E.C. Analysis of chemical polymerization between functionalized MWCNT and poly(furfuryl alcohol) composite. Polímeros 2018, 28, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.-L.; Qing, C.; Zhang, R.; Wu, S.-Q.; Xu, Z.-H.; Wang, Y.-H.; Du, K.; Yin, Q.-J. rGO/CNTs/PEDOT: PSS ternary composites with enhanced thermoelectric properties. Synthetic Metals 2023, 300, 117493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, P.; Mandal, S.; Sarkar, A.; Kargupta, K.; Banerjee, D. Pure organic dual phase polypyrrole wrapped single-walled carbon nanotube hybrid nano-photocatalyst for solar hydrogen generation. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry 2025, 462, 116210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.P.P.; Trigueiro, J.P.C.; Calado, H.D.R.; Silva, G.G. Poly(3-hexylthiophene)-multi-walled carbon nanotube (1:1) hybrids: Structure and electrochemical properties. Electrochimica Acta 2016, 209, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.W.; Kim, T.; Kim, Y.S.; Choi, H.S.; Lim, H.J.; Yang, S.J.; Park, C.R. Surface modifications for the effective dispersion of carbon nanotubes in solvents and polymers. Carbon 2012, 50, 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Gu, M.; Guo, Y.; Pan, X.; Mu, G. Effects of carbon nanotube functionalization on the mechanical and thermal properties of epoxy composites. Carbon 2009, 47, 1723–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasdevan, N.; Mohd Abdah, M.A.A.; Sulaiman, Y. Facile Electrodeposition of Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) on Poly(vinyl alcohol) Nanofibers as the Positive Electrode for High-Performance Asymmetric Supercapacitor. Energies 2019, 12, 3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, W.M.; Ribeiro, H.; Seara, L.M.; Calado, H.D.R.; Ferlauto, A.S.; Paniago, R.M.; Leite, C.F.; Silva, G.G. Surface properties of oxidized and aminated multi-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2012, 23, 1078–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigueiro, J.P.C.; Silva, G.G.; Lavall, R.L.; Furtado, C.A.; Oliveira, S.; Ferlauto, A.S.; Lacerda, R.G.; Ladeira, L.O.; Liu, J.-W.; Frost, R.L.; George, G.A. Purity Evaluation of Carbon Nanotube Materials by Thermogravimetric, TEM, and SEM Methods. J. Nanosci. Nanotech 2007, 7, 3477–3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.; Chen, Q.; Lessner, P. Thermal Stability Investigation of PEDOT Films from Chemical Oxidation and Prepolymerized Dispersion. Electrochemistry 2013, 81, 801–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, A.; Jiang, L.; Yue, J.; Tong, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Lin, Z.; Liu, B.; Wu, C.; Suo, L.; Hu, Y.-S.; Li, H.; Chen, L. Water-in-Salt Electrolyte Promotes High-Capacity FeFe(CN)6 Cathode for Aqueous Al-Ion Battery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 41356–41362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ates, M. Review study of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and equivalent electrical circuits of conducting polymers on carbon surfaces. Progress in Organic Coatings 2011, 71, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Sun, R.; Xiong, F.; Pei, C.; Han, K.; Peng, C.; Fan, Y.; Yang, W.; An, Q.; Mai, L. A rechargeable aluminum-ion battery based on a VS2 nanosheet cathode. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 22563–22568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Bi, X.; Bai, Y.; Wu, C.; Gu, S.; Chen, S.; Wu, F.; Amine, K.; Lu, J. Open-Structured V2 O5 · n H2 O Nanoflakes as Highly Reversible Cathode Material for Monovalent and Multivalent Intercalation Batteries. Advanced Energy Materials 2017, 7, 1602720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Niu, B.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Kang, F. Rechargeable Aluminum-Ion Battery Based on MoS2 Microsphere Cathode. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 9451–9459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).