Submitted:

21 December 2025

Posted:

22 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Mutations in ATP7B impair biliary copper excretion and copper–ceruloplasmin release, causing hepatic copper overload in Wilson’s disease (WD). Metallothionein (MT), a key intracellular copper buffering agent, is overexpressed in WD liver. We evaluated the diagnostic significance of MT immunostaining in explanted livers from hepatic and neurological WD, including untreated cases and those receiving short- versus long-term chelation. Histochemical and immunohistochemical analyses were performed. Our results show that MT overexpression progresses to irreversible accumulation. Sustained copper-induced redox cycles promote MT polymerisation, aggregation, and resistance to proteolysis, accompanied by oxidative stress, lysosomal dysfunction, and hepatocellular injury. MT localises to bile canaliculus membranes, hepatocyte nuclei, lysosomes, and mesenchymal cells, suggesting discrete roles in disease mechanisms. Given the persistent MT accumulation despite prolonged chelation, we propose that MT fails to neutralise excess copper in WD; instead, polymerised MT traps Cu+, depleting the cytosolic copper pool destined to ATP7B-mediated ceruloplasmin loading, plasma secretion, and biliary export. Accordingly, MT dysregulation emerges as central to WD pathogenesis and supports MT immunohistochemistry as a sensitive diagnostic adjunct. These findings provide a rationale for developing more efficient chelators that mobilise hepatic copper stores without causing MT build-up, potentially improving outcomes.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

Patient 1 (Neurological Wilson’s Disease)

Patient 2 (Cholangiocarcinoma Case)

Patient 3 (Acute on Chronic Liver Failure)

Patient 4 (Decompensated Cirrhosis)

Patient 5 (Decompensated Cirrhosis)

3. Methods

4. Results

Macroscopy

Histopathology

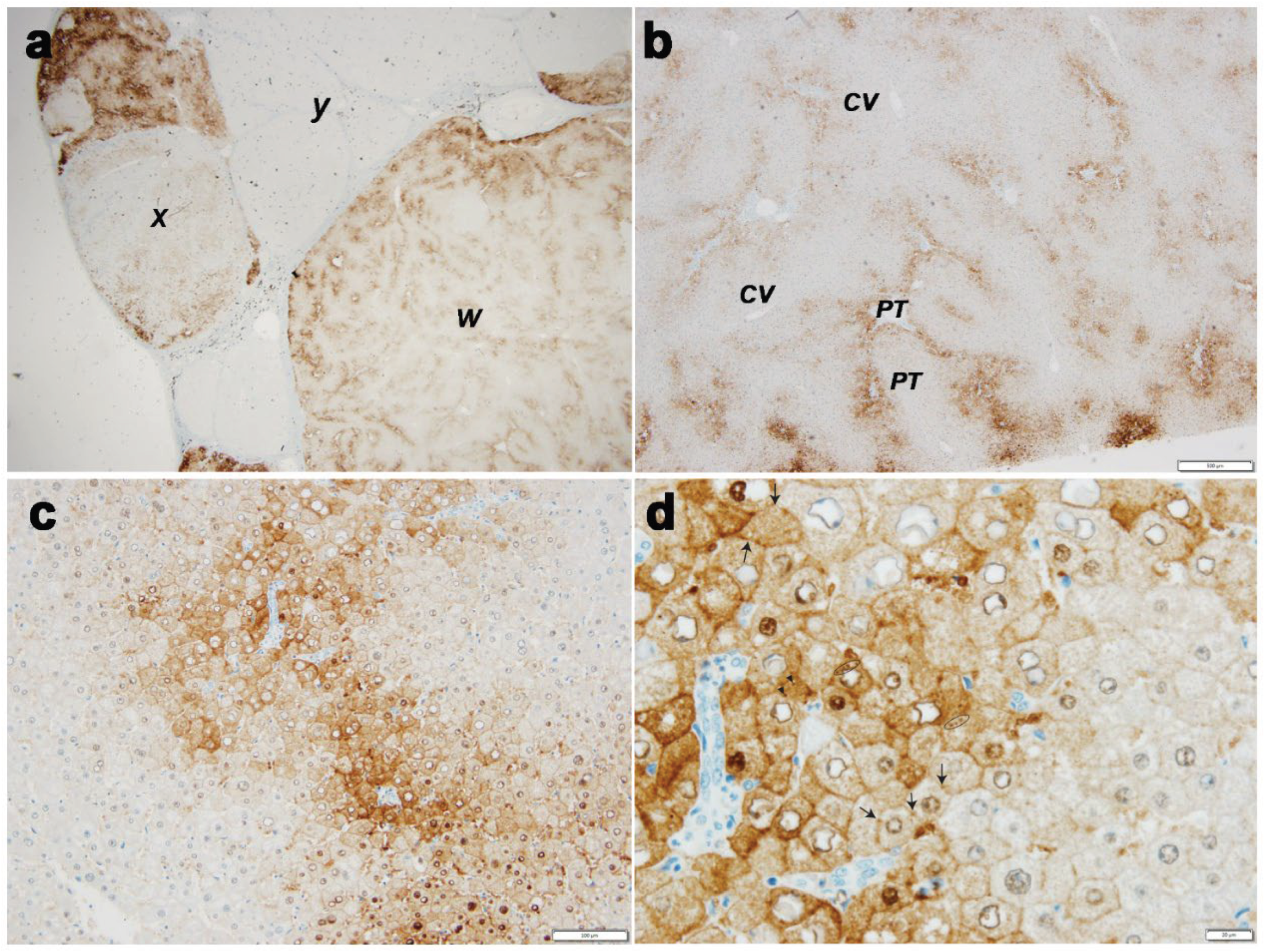

Case 1 (Figure 1, Panel 1)

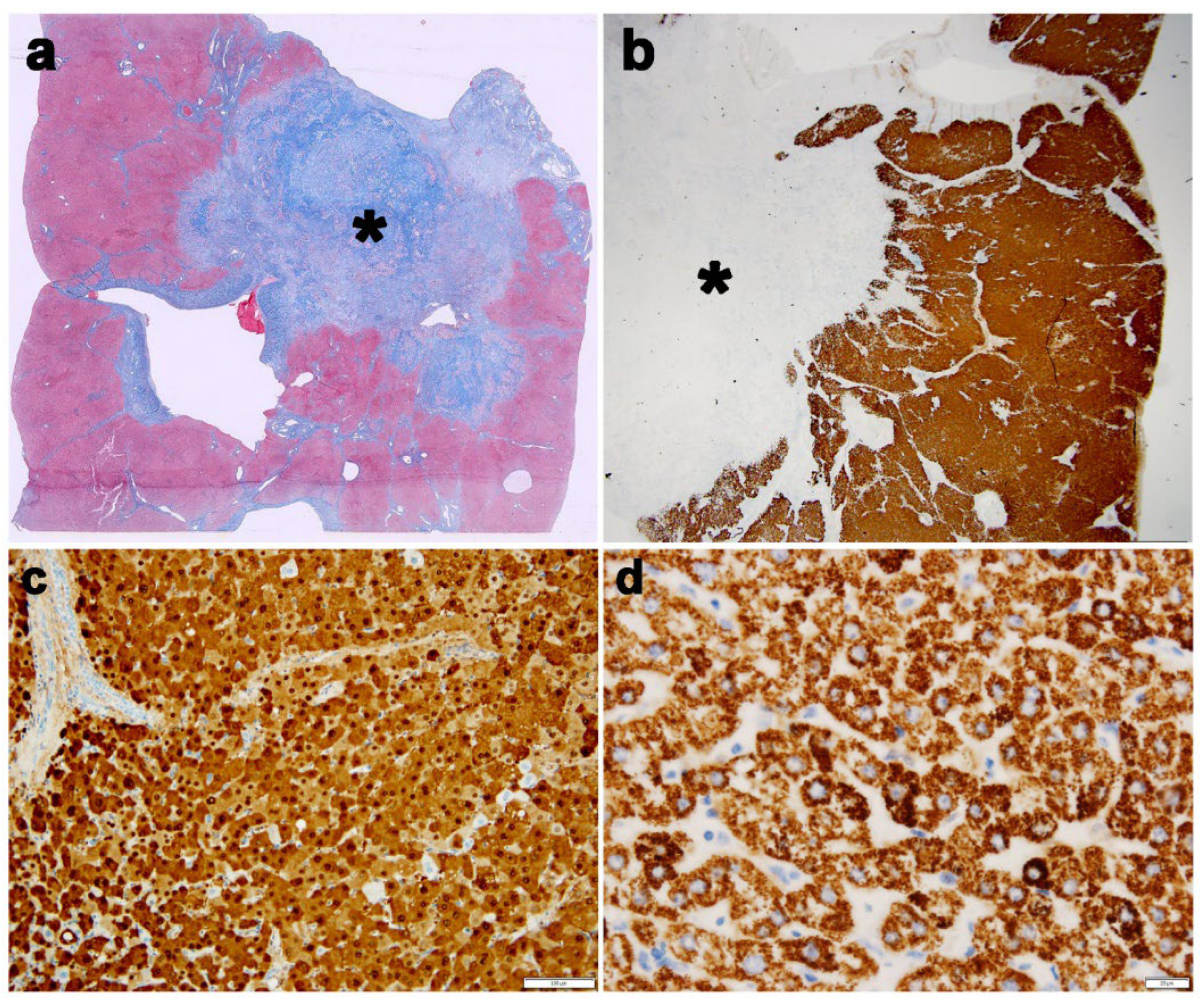

Case 2 (Figure 2, Panel 2)

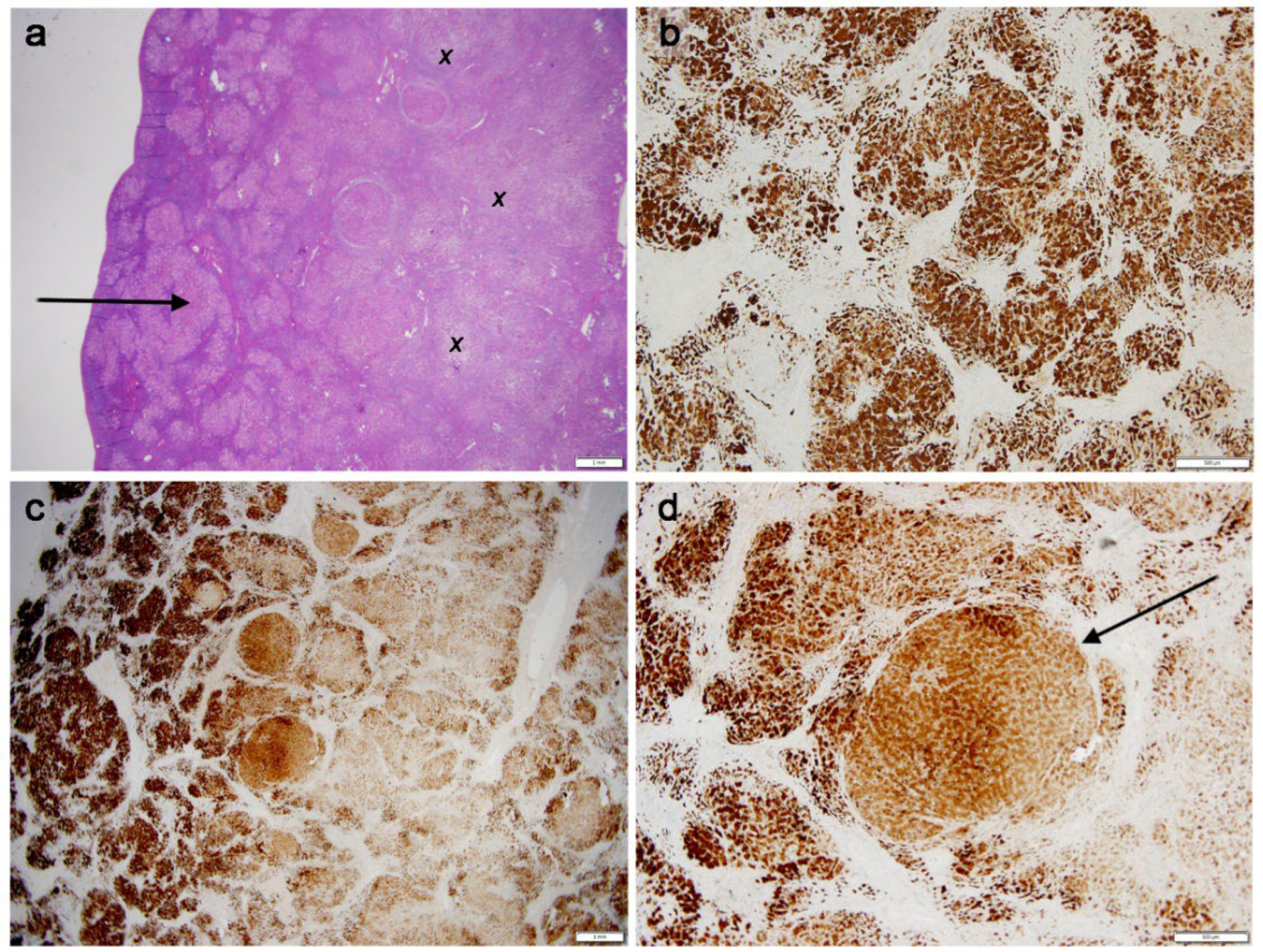

Cases 3 (Figure 3, Panel 3)

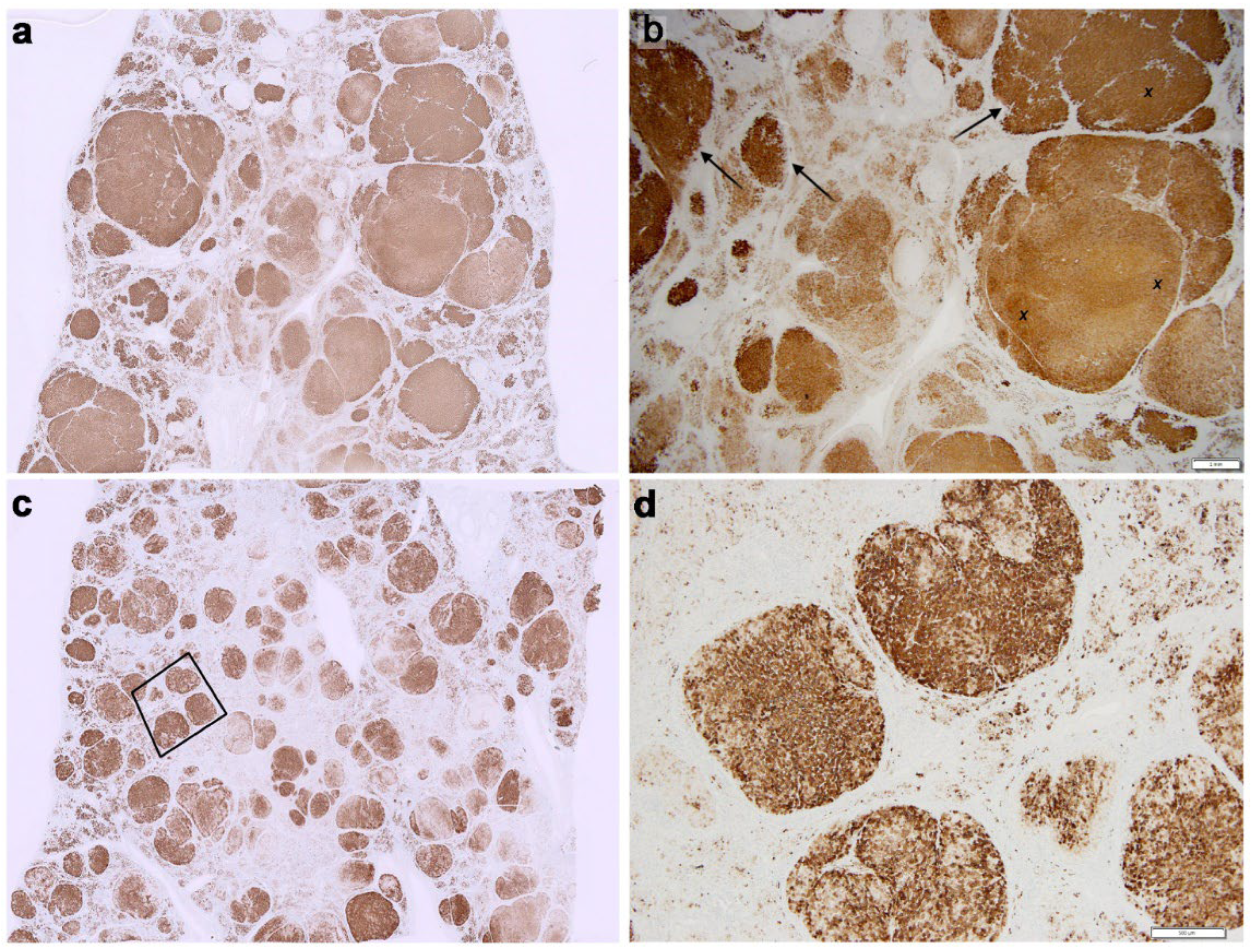

Case 4 (Figure 4, Panel 4 a,b)

Case 5 (Figure 4, Panel 4 c,d)

5. Discussion

- Mechanism of MT accumulation

- Meaning of MT subcellular localisations under physiological conditions and in WD

- Proposed role of copper and MT extra-hepatocytic deposits in WD diagnosis and progression

- MT–CP relationship

5.1. Mechanism of MT Accumulation

5.2. Meaning of MT Subcellular Localisations Under Physiological Conditions and in WD

5.3. Proposed Role of Copper and MT Extrahepatocytic Deposits in WD Diagnosis and Progression

5.4. MT–CP Relationship

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bull, P.C.; Thomas, G.R.; Rommens, J.M.; Forbes, J.R.; Cox, D.W. The Wilson disease gene is a putative copper transporting P–type ATPase similar to the Menkes gene. Nat. Genet. 1993, 5, 327–337. [CrossRef]

- A Roberts, E.; Schilsky, M.L. Current and Emerging Issues in Wilson’s Disease. New Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 922–938. [CrossRef]

- Członkowska A, Litwin T, Dusek P, Ferenci P, Lutsenko S, Medici V, Rybakowski JK, Weiss KH, Schilsky ML. Wilson disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:21.

- Lalioti, V.; Muruais, G.; Tsuchiya, Y.; Pulido, D.; Sandoval, I.V. Molecular mechanisms of copper homeostasis. Front. Biosci. 2009, 14, 4878–903. [CrossRef]

- Lutsenko, S. Dynamic and cell-specific transport networks for intracellular copper ions. J. Cell Sci. 2021, 134. [CrossRef]

- Delangle P. Mintz E: Chelation therapy in Wilson’s disease: from D-penicillamine to the design of selective bioinspired intracellular Cu chelators: Dalton Trans. 2012;41: 6359-70.

- Rowan, D.J.; Mangalaparthi, K.K.; Singh, S.; Moreira, R.K.; Mounajjed, T.; Lamps, L.; Westerhoff, M.; Cheng, J.; Bellizzi, A.M.; Allende, D.S.; et al. Metallothionein immunohistochemistry has high sensitivity and specificity for detection of Wilson disease. Mod. Pathol. 2022, 35, 946–955. [CrossRef]

- Wiethoff, H.; Mohr, I.; Fichtner, A.; Merle, U.; Schirmacher, P.; Weiss, K.H.; Longerich, T. Metallothionein: a game changer in histopathological diagnosis of Wilson disease. Histopathology 2023, 83, 936–948. [CrossRef]

- Stokes NL Patil A, et al. Validation of Metallothionein Immunohistochemistry as a High Sensitive Screening Test for Wilson Disease. Mod Pathol 2025;38:1-7.

- Stromeyer, F.W.; Ishak, K.G. Histology of the Liver in Wilson’s Disease: A Study of 34 Cases. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1980, 73, 12–24. [CrossRef]

- Faa, G.; Nurchi, V.; Demelia, L.; Ambu, R.; Parodo, G.; Congiu, T.; Sciot, R.; Van Eyken, P.; Silvagni, R.; Crisponi, G. Uneven hepatic copper distribution in Wilson's disease. J. Hepatol. 1995, 22, 303–308. [CrossRef]

- Mulder, T.; Janssens, A.; Verspaget, H.; van Hattum, J.; Lamers, C. Metallothionein concentration in the liver of patients with Wilson's disease, primary biliary cirrhosis, and liver metastasis of colorectal cancer. J. Hepatol. 1992, 16, 346–350. [CrossRef]

- Sugawara, N.; Sato, M.; Yuasa, M.; Sugawara, C. Biliary Excretion of Copper, Metallothionein, and Glutathione into Long-Evans Cinnamon Rats: A Convincing Animal Model for Wilson Disease. Biochem. Mol. Med. 1995, 55, 38–42. [CrossRef]

- Zhang CC, Volkman M, Tuma S, Stremmel W. Metallothionein is elevated in liver and duodenum of Atp7b (-/-) mice. Biometals 2018;31:617-625.

- Bremner, I.; Mehra, R.K.; Sato, M. Metallothionein in blood, bile, and urine. Experientia Suppl 1987;52:507-517.

- Cherian MG. The significance of the nuclear and cytoplasmic localization of metallothionein in human liver and tumor cells. Environ Health Perspect. 1994;102 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):131-5.

- Mehra, R.K.; Bremner, I. Species differences in the occurrence of copper-metallothionein in the particulate fractions of the liver of copper-loaded animals. Biochem. J. 1984, 219, 539–546. [CrossRef]

- Sternlieb, I. Hepatic lysosomal copper-thionein. Experientia Suppl 1987;52: 647-653.

- Sakurai, H.; Nakajima, K.; Kamada, H.; Satoh, H.; Otaki, N.; Kimura, M.; Kawano, K.; Hagino, T. Copper-Metallothionein Distribution in the Liver of Long-Evans Cinnamon Rats: Studies on Immunohistochemical Staining, Metal Determination, Gel Filtration and Electron Spin Resonance Spectroscopy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993, 192, 893–898. [CrossRef]

- Hanaichi T, Kidokoro R, Hayashi H, Sakamoto N. Electron probe X-ray analysis on human hepatocellular lysosomes with copper deposits: copper binding to a thiol-protein in lysosomes. Lab Invest. 1984;51:592-7.

- Chowrimootoo, G.F.E.; Ahmed, H.A.; Seymour, C.A. New insights into the pathogenesis of copper toxicosis in Wilson's disease: evidence for copper incorporation and defective canalicular transport of caeruloplasmin. Biochem. J. 1996, 315, 851–855. [CrossRef]

- Koch, K.A.; Peña, M.M.O.; Thiele, D.J. Copper-binding motifs in catalysis, transport, detoxification and signaling. Chem. Biol. 1997, 4, 549–560. [CrossRef]

- Tapia, L.; González-Agüero, M.; Cisternas, M.F.; Suazo, M.; Cambiazo, V.; Uauy, R.; González, M. Metallothionein is crucial for safe intracellular copper storage and cell survival at normal and supra-physiological exposure levels. Biochem. J. 2004, 378, 617–624. [CrossRef]

- Heilmaier, H.; Jiang, J.; Greim, H.; Schramel, P.; Summer, K. D-penicillamine induces rat hepatic metallothionein. Toxicology 1986, 42, 23–31. [CrossRef]

- McArdle, H.J.; Kyriakou, P.; Grimes, A.; Mercer, J.F.; Danks, D.M. The effect of d-penicillamine on metallothionein mRNA levels and copper distribution in mouse hepatocytes. Chem. Interactions 1990, 75, 315–324. [CrossRef]

- Fabisiak, J.P.; Tyurin, V.A.; Tyurina, Y.Y.; Borisenko, G.G.; Korotaeva, A.; Pitt, B.R.; Lazo, J.S.; Kagan, V.E. Redox Regulation of Copper–Metallothionein. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1999, 363, 171–181. [CrossRef]

- Jiang LJ, Maret W, Vallee BL. The ATP-metallothionein complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 1998;95:9146-9.

- A Roberts, E.; Schilsky, M.L. Current and Emerging Issues in Wilson’s Disease. New Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 922–938. [CrossRef]

- Blockhuys, S.; Celauro, E.; Hildesjö, C.; Feizi, A.; Stål, O.; Fierro-González, J.C.; Wittung-Stafshede, P. Defining the human copper proteome and analysis of its expression variation in cancers. Metallomics 2017, 9, 112–123. [CrossRef]

- Haase, H.; Maret, W. Partial oxidation and oxidative polymerization of metallothionein. Electrophoresis 2008, 29, 4169–4176. [CrossRef]

- Krizkova, S.; Adam, V.; Kizek, R. Study of metallothionein oxidation by using of chip CE. Electrophoresis 2009, 30, 4029–4033. [CrossRef]

- Křížková, S.; Masařík, M.; Eckschlager, T.; Adam, V.; Kizek, R. Effects of redox conditions and zinc(II) ions on metallothionein aggregation revealed by chip capillary electrophoresis. J. Chromatogr. A 2010, 1217, 7966–7971. [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.P. Redox potential of GSH/GSSG couple: assay and biological significance. Methods Enzymol. 2002;348:93-112.

- Rafter, G.W. The effect of copper on glutathione metabolism in human leukocytes. Biol. Trace Element Res. 1982, 4, 191–197. [CrossRef]

- Farinati, F.; Cardin, R.; D’inca, R.; Naccarato, R.; Sturniolo, G.C. Zinc treatment prevents lipid peroxidation and increases glutathione availability in Wilson’s disease. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 2003, 141, 372–377. [CrossRef]

- Fabisiak JP, Pearce LL, Borisenko GG, Tyhurina YY, Tyurin VA, Razzack J, Lazo JS, Pitt BR, Kagan VE. Bifunctional ani/prooxidant potential of metallothionein: redox signal of copper bindng and release Antioxid Redox Signal 1999;1:3-349.

- Suzuki, K.T.; Rui, M.; Ueda, J.; Ozawa, T. Production of hydroxyl radicals by copper-containing metallothionein: roles as prooxidant. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1996, 141, 231–7.

- Zischka Hans, Lichtmannegger Josef. Cellular copper toxicity: a critical appraisal of Fenton-chemistry-based oxidative stress in Wilson disease. Wilson Disease, Pathogenesis, Molecular Mechanisms, Diagnosis, Treatment and Monitoring. 2019; pages 65-81. Edited by Karl Heinz Weissand Michel Schilsky.

- Cousins, R.J. Absorption, transport, and hepatic metabolism of copper and zinc: special reference to metallothionein and ceruloplasmin.. Physiol. Rev. 1985, 65, 238–309. [CrossRef]

- Hou, T.; Xu, X.; An, Y.; Ru, B.; Bi, R. Cysteine-independent polymerization of metallothioneins in solutions and in crystals. Protein Sci. 2000, 9, 2302–2312. [CrossRef]

- Ralle M, Huster D, Vogt S, Schirrmeister W, Burkhead JL, Capps TR, Gray L, Lai B, Maryon E, Lutsenko S. Wilson disease at a single cell level: intracellular copper trafficking activates compartment-specific responses in hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 2010; 285:30875-83.

- Wooton-Kee, C.R.; Jain, A.K.; Wagner, M.; Grusak, M.A.; Finegold, M.J.; Lutsenko, S.; Moore, D.D. Elevated copper impairs hepatic nuclear receptor function in Wilson’s disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 3449–3460. [CrossRef]

- Dev, S.; Kruse, R.L.; Hamilton, J.P.; Lutsenko, S. Wilson Disease: Update on Pathophysiology and Treatment. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 871877. [CrossRef]

- Huster, D.; Lutsenko, S. Wilson disease: not just a copper disorder. Analysis of a Wilson disease model demonstrates the link between copper and lipid metabolism. Mol. Biosyst. 2007, 3, 816–824. [CrossRef]

- Elmes, M.E.; Clarkson, J.P.; Mahy, N.J.; Jasant, B. Metallothionein and copper in liver disease with copper retention—a histopathological study. J. Pathol. 1989, 158, 131–137. [CrossRef]

- NARTEY, N.; FREI, J.; CHERIAN, M. HEPATIC COPPER AND METALLOTHIONEIN DISTRIBUTION IN WILSONS-DISEASE (HEPATOLENTICULAR DEGENERATION). Lab Invest. 1987, 57, 397–401.

- GOLDFISCHER, S. LOCALIZATION OF COPPER IN PERICANALICULAR GRANULES (LYSOSOMES) OF LIVER IN WILSONS DISEASE (HEPATOLENTICULAR DEGENERATION). Am J Pathol. 1965, 46, 977–+.

- Jonas L, Fulda G, Salameh T, Schmidt W, Kroning G, Hoopt UT, Nizze H. Electron microscopic detection of copper in the liver of two patients with morbus Wilson by FELS and EDX. Ultrasct Pathol 2001;25:111-8.

- Beltramini, M.; Lerch, K. Luminescence properties of neurospora copper metallothionein. FEBS Lett. 1981, 127, 201–203. [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.B.; Myers, B.M.; Kost, L.J.; Kuntz, S.M.; LaRusso, N.F. Biliary copper excretion by hepatocyte lysosomes in the rat. Major excretory pathway in experimental copper overload.. J. Clin. Investig. 1989, 83, 30–39. [CrossRef]

- Myers, B.M.; Prendergast, F.G.; Holman, R.; Kuntz, S.M.; Larusso, N.F. Alterations in hepatocyte lysosomes in experimental hepatic copper overload in rats. Gastroenterology 1993, 105, 1814–1823. [CrossRef]

- Summer, K.H.; Lichtmannegger, J.; Bandow, N.; Choi, D.W.; DiSpirito, A.A.; Michalke, B. The biogenic methanobactin is an effective chelator for copper in a rat model for Wilson disease. J. Trace Elements Med. Biol. 2011, 25, 36–41. [CrossRef]

- Sternlieb, I.; Hamer, C.v.D.; Morell, A.G.; Alpert, S.; Gregoriadis, G.; Scheinberg, I.H. Lysosomal Defect of Hepatic Copper Excretion in Wilson's Disease (Hepatolenticular Degeneration). Gastroenterology 1973, 64, 99–105. [CrossRef]

- Schemberg JH, Jaffe ME, Sternilieb I. Thr use of trientine in preventing the effects of interrupting penicillamine therapy in Wilson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1987;31:300-313.

- Ping, C.C.; Hassan, Y.; Aziz, N.A.; Ghazali, R.; Awaisu, A. Discontinuation of penicillamine in the absence of alternative orphan drugs (trientine?zinc): a case of decompensated liver cirrhosis in Wilson's disease. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2007, 32, 101–107. [CrossRef]

- Marecek, Z.; Heyrovský, A.; Volek, V. The effect of long term treatment with penicillamine on the copper content in the liver in patients with Wilson's disease. Acta Hepato-Gastroenterologica 1975, 22, 292–6.

- Evering, W.; Haywood, S.; Bremner, I.; Wood, A.M.; Trafford, J. The protective role of metallothionein in copper-overload: II. Transport and excretion of immunoreactive MT-1 in blood, bile and urine of copper-loaded rats. Chem. Interactions 1991, 78, 297–305. [CrossRef]

- Kurz, T.; Eaton, J.W.; Brunk, U.T. Redox Activity Within the Lysosomal Compartment: Implications for Aging and Apoptosis. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2010, 13, 511–523. [CrossRef]

- Lutsenko S. Atp7b-/- mice as a model for studies of Wilson’s disease. Biochen Soc trans 2008;36:123-128.

- Whitehouse, M.W.; Walker, W.R. Copper and inflammation. Inflamm. Res. 1978, 8, 85–90. [CrossRef]

- Milanino R, Conforti A, Franco L, Marrella M, Velo G. Copper and inflammation--a possible rationale for the pharmacological manipulation of inflammatory disorders. Agents Actions. 1985;16:504-513.

- White, C.; Lee, J.; Kambe, T.; Fritsche, K.; Petris, M.J. A Role for the ATP7A Copper-transporting ATPase in Macrophage Bactericidal Activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 33949–33956. [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.-Y.; Garnica, A.D.; Rennert, O.M. Inducibility of Metallothionein Biosynthesis in Cultured Normal and Menkes Kinky Hair Disease Fibroblasts: Effects of Copper and Cadmium. Pediatr. Res. 1979, 13, 197–203. [CrossRef]

- Sass-Kortsak A, Cherniak M, Geiger DW, Slater R. Observations on ceruloplasmin in Wilson’s disease. J Clin Invest 1959; 38:1672-82.

- European Association for the Study of the Liver EASL, clinical practice guidelines: Wilson’s disease. J Hepatol 2012;56: 671-685.

- Kaler SG. Menkes disease. Adv Pediatr. 1994;41:263-304.

- Alsaif HS, Alkuraya FS. IDEDNIK Syndrome. 2024 Nov 14. In: Adam MP, Bick S, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Amemiya A, editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993–2025.

- Martinelli, D.; Travaglini, L.; Drouin, C.A.; Ceballos-Picot, I.; Rizza, T.; Bertini, E.; Carrozzo, R.; Petrini, S.; de Lonlay, P.; El Hachem, M.; et al. MEDNIK syndrome: a novel defect of copper metabolism treatable by zinc acetate therapy. Brain 2013, 136, 872–881. [CrossRef]

- Loréal, O.; Turlin, B.; Pigeon, C.; Moisan, A.; Ropert, M.; Morice, P.; Gandon, Y.; Jouanolle, A.-M.; Vérin, M.; Hider, R.C.; et al. Aceruloplasminemia: new clinical, pathophysiological and therapeutic insights. J. Hepatol. 2002, 36, 851–856. [CrossRef]

- Nunes, V.S.; Andrade, A.R.; Guedes, A.L.V.; A Diniz, M.; Oliveira, C.P.; Cançado, E.L.R. DISTINCT PHENOTYPE OF NON-ALCOHOLIC FATTY LIVER DISEASE IN PATIENTS WITH LOW LEVELS OF FREE COPPER AND OF CERULOPLASMIN. Arq. de Gastroenterol. 2020, 57, 249–253. [CrossRef]

- Wang Q, D, Wang M, Zhou M, Chem P, Liu L, Xinxin LM, Shen Z, Liu X, Chen T. A novel non- invasive approach based on serum ceruloplasmin for identifying non-alcoholic steato-hepatitis patients in the non-diabetic population. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:900794.

- Evans, G.; Majors, P.F.; Cornatzer, W. Induction of ceruloplasmin synthesis by copper. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1970, 41, 1120–1125. [CrossRef]

- Sternlieb, I.; Morell, A.G.; Tucker, W.D.; Greene, M.W.; Scheinberg, I.H. THE INCORPORATION OF COPPER INTO CERULOPLASMIN IN VIVO: STUDIES WITH COPPER64 AND COPPER67*. J. Clin. Investig. 1961, 40, 1834–1840. [CrossRef]

- Jeunet, F.; Richterich, R. [Bile and ceruloplasmin. Study in vitro by the aid of perfusion of the isolated rat liver]. J. Physiol. 1962, 54, 729–37.

- Aisen, P.; Morell, A.G.; Alpert, S.; Sternlieb, I. Biliary Excretion of Cæruloplasmin Copper. Nature 1964, 203, 873–874. [CrossRef]

- Puchkova, LV Aleĭnikova, TD Verbina, IA Zakharova, ET Pliss, MG Gaĭtskhoki, vs. Biosintez dvukh molekuliarnykh form tseruloplazmina v pecheni krysy i ikh poliarnaia sekretsiia v krovotok i v zhelch’ [Biosynthesis of two molecular forms of ceruloplasmin in rat liver and their polar secretion into the blood stream and bile]. Biokhimiia. 1993;58:1893-1901.

- Davis W, Chowrimootoo GFE, Seymour C A. Defective biliary copper excretion in Wilson’s disease: the role of ceruloplasmin. Eur J Clin Invest. 1996; 26:893-901.

- Sabatini, D.D.; Kreibich, G.; Morimoto, T.; Adesnik, M. Mechanisms for the incorporation of proteins in membranes and organelles.. J. Cell Biol. 1982, 92, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- M’hammed, A Pasquin J Furton, A Waldron, C Mateescu, MA. Oxidative aggregation of ceruloplasmin induced by hydrogen peroxide is prevented by pyruvate. Free Rad Res 2004;39:19-36.

- Vasiliyev, VB. Looking for a partner: ceruloplasmin-protein interactions. Biometals 2919;37:195-210.

- Callea, F, Ray, MB Desmet, VJ. Alpha-I-antitrypsin and copper in the liver. Histopathology. 1981;5:415-424.

- Griffiths, S.W.; King, J.; Cooney, C.L. The Reactivity and Oxidation Pathway of Cysteine 232 in Recombinant Human α1-Antitrypsin. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 25486–25492. [CrossRef]

| Patient | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Age | 14 years | 67 | 49 years | 9 years | 15 years |

| Sex | F | F | M | F | F |

| Ethnics | Albania | Italy | Italy | Italy | Romania |

| Diagnosis | Neurological WD & liver cirrhosis |

CCA, CLD & neurological symptoms | ACLD | ACLD | ACLD |

| Age at diagnosis | 14 years | 34 years | 4 years | 9 years | 16 years |

| Date of Tx | 14 years | 62 years | 49 years | 9 years | 16 years |

| Interval between diagnosis and Tx | 4 months | 2 months | 44 years | 12 months | 4 months |

| Tx Center | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| CP | <8.45 | 11 | 10.5 | 7 | 16 |

| Cu tissue | 580 | 1.1 | 1.013 | 1.013 | 1.23 |

| ATP7B mutation | c.1772G>A(p.Gly591Asp); c.3207C>A (p.His1069Gln) | H1069Q D918N |

ND | c.3207C>A(p.His1069Gln) c.304dupC(p.Met769fsTer26) | c.2293G>A(p.Asp765Asn);c.2906G>A(p.Asp969Gln) |

| KFR | YES | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Treatment | NO | PNA+ Trientine | PNA, trientine | PNA+Zinc | Zinc+PNA |

| Treatment duration | 4 months | 28 years | 42 years, discontinous | 2 months | 5 months |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.