Submitted:

19 December 2025

Posted:

22 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

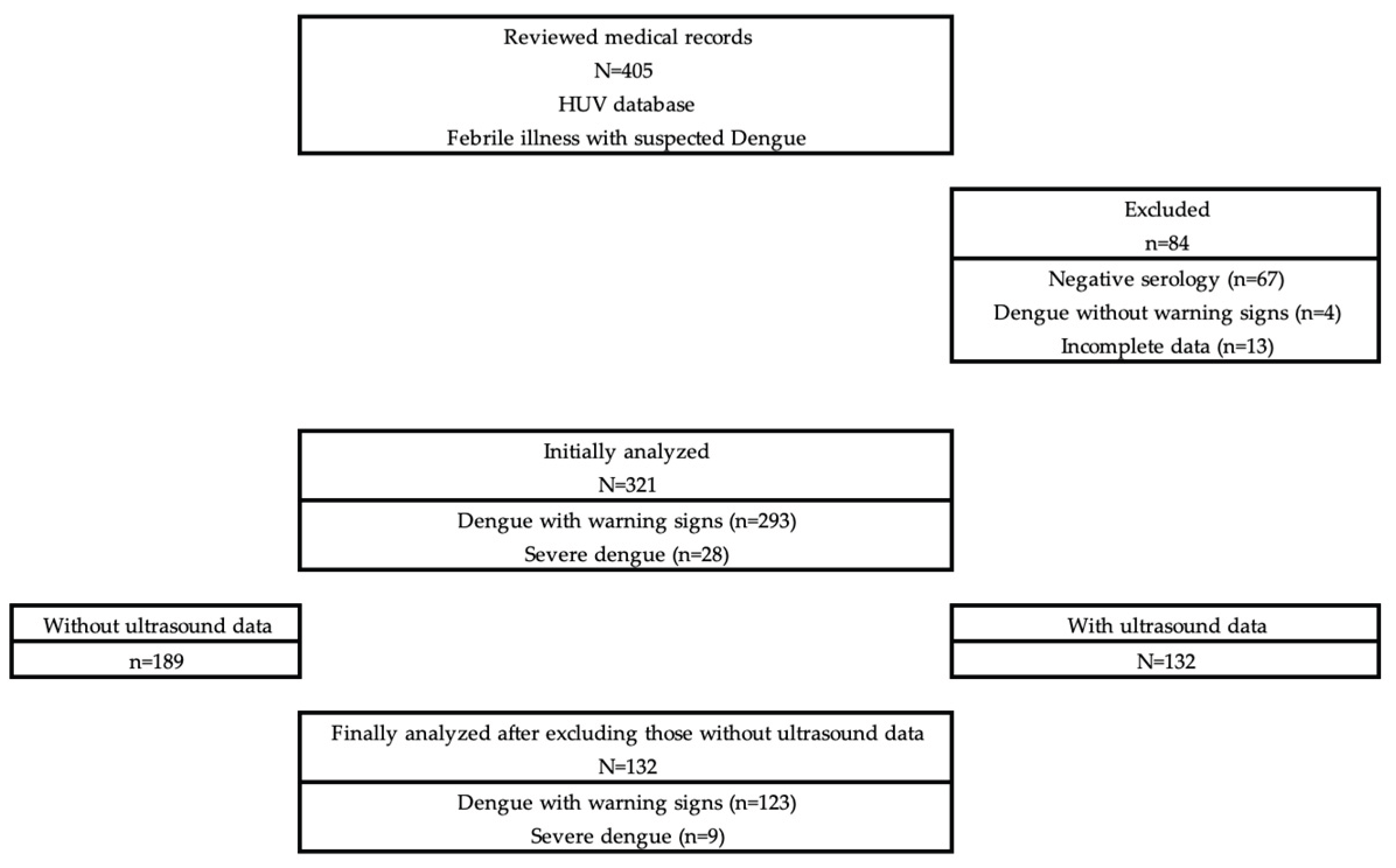

Background/Objectives: Dengue is one of the leading causes of morbidity in children in endemic regions. Capillary leakage is the pathophysiological hallmark of severe dengue, and ultrasound has established as a sensitive tool for its early detection. However, evidence in pediatric population remains limited. The aim of this study was to identify the presence of capillary leakage detected by ultrasound and its associations in children with dengue. Methods: Observational/descriptive/cross-sectional/retrospective study conducted in patients between 6-months and 14-years-old with confirmed dengue and warning signs or severe dengue, treated at the Hospital Universitario del Valle in Cali, Colombia, between July 2019 and June 2020. Ultrasound examinations were performed and interpreted by radiologists following an institutional standardized protocol. Associations with capillary leakage were evaluated using the chi-square test and their respective OR and 95%CI. Results: A total of 132 children were included. Ultrasound capillary leakage was identified in 95.5%, mainly ascites (83.3%), pleural effusion (46.2%), hepatomegaly (40.9%), and vesicular thickening (39.4%). Associated factors were belonging to school/adolescent group (OR=13.52; 95%CI=1.41–646.51; p=0.0031), elevated alanine aminotransferase (OR=11.06; 95%CI=1.32–94.82; p=0.0007), and aminotransferase levels grades C–D (OR=6.87; 95%CI=0.82–54.59; p=0.0110). Thrombocytopenia and hypoalbuminemia were common. Three deaths (0.9%) occurred in the initially confirmed cohort prior to ultrasound-based inclusion, all of whom presented multiple risk factors for capillary leakage. Conclusions: In this cohort ultrasound showed high sensitivity for detecting capillary leakage in pediatric dengue and was associated with school-age/adolescents and liver involvement. Its systematic use could improve early identification of severe forms and optimize clinical management in resource-limited settings.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics

3.2. Imaging

3.3. Possible Risk Factors

3.4. Mortality

4. Discussion

4.1. Prevalence of Capillary Leakage Ultrasound Findings

4.2. Implementation of Ultrasound Protocols and Serial Assessment

4.3. Factors Associated with Capillary Leakage

4.4. Clinical Implications, Prognostic Value, and Mortality

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| IFN-γ | Interferon gamma |

| IL | Interleukins |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| HUV | Hospital Universitario del Valle "Evaristo García" |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| χ² | Chi-square |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| 95%CI | 95% confidence intervals |

| X±SD | Mean ± standard deviation |

| POCUS | Point-of-care ultrasound |

References

- Foucambert, P.; Esbrand, F.D.; Zafar, S.; Panthangi, V.; Cyril, A.R.; Raju, A.; et al. Efficacy of Dengue Vaccines in the Prevention of Severe Dengue in Children: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e28916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilder-Smith, A.; Eng-Eong, O.; Horstick, O.; Wills, B. Dengue. Lancet 2019, 393, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moras, E.; Achappa, B.; Murlimanju, B.V.; Naveen, G.M.; Holla, R.; Madi, D.; et al. Early diagnostic markers in predicting the severity of dengue disease. Biotech 2022, 12, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabaan, A.A.; Alshengeti, A.; Alrasheed, H.A.; Al-Subaie, M.F.; Aljohani, M.H.; Almutawif, Y.A.; et al. Dengue virus infection in Saudi Arabia from 2003 to 2023: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pathog Glob Health 2024, 118, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Morales, A.J.; López-Medina, E.; Arboleda, I.; Cardona-Ospina, J.A.; Castellanos, J.E.; Faccini-Martínez, A.A.; et al. The Epidemiological Impact of Dengue in Colombia: A Systematic Review. J Trop Med Hyg 2025, 112, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hause, A.M.; Perez-Padilla, J.; Horiuchi, K.; Han, G.S.; Hunsperger, E.; Aiwazian, J.; et al. Epidemiology of Dengue among Children Aged <18 Months—Puerto Rico, 1999–2011. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2016, 94, 404–408. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, S.; Ramanathan, R.; Kumar, S. Clinical Profile of Dengue Fever in Children: A Study from Southern Odisha, India. Scientifica (Cairo) 2016, 6391594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- L'Azou, M.; Moureau, A.; Sarti, E.; Nealon, J.; Zambrano, B.; Wartel, T.A.; et al. Symptomatic Dengue in Children in 10 Asian and Latin American Countries. N Engl J Med 2016, 374, 1155–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malarnangai, G.A.; Jasinge, E.; Gunasena, S.; Samaranayake, D.; Prasanta, M.; Pujitha, V. Evaluation of biochemical and haematological changes in dengue fever and dengue hemorrhagic fever in Sri Lankan children: a prospective follow up study. BMC Pediatr 2019, 19, 87. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, D.; Bhriguvanshi, A. Clinical Profile, Liver Dysfunction and Outcome of Dengue Infection in Children: A Prospective Observational Study. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2020, 39, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Samal, S.; Rout, S.; Kumar, C.; Sahu, M.C.; Das, B. Immunomodulation in dengue: towards deciphering dengue severity markers. Cell Commun Signal 2024, 22, 451. [Google Scholar]

- Mercado-Hernández, R.; Myers, R.; Bustos, F.A.; Zambrana, J.V.; López, B.; Sánchez, N.; et al. Obesity Is Associated With Increased Pediatric Dengue Virus Infection and Disease: A 9-Year Cohort Study in Managua, Nicaragua. Clin Infect Dis 2024, 79, 1102–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, C.; Ahmed, H.; Sharma, P.; Seetharami, E.; Nayak, K.; Singla, M.; et al. Severe disease during both primary and secondary dengue virus infections in pediatric populations. Nat Med 2024, 30, 670–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivasubramanian, K.; Bharath, R.; Kakithakara, L.; Kumar, M.; Banerjee, A. Key Laboratory Markers for Early Detection of Severe Dengue. Viruses 2025, 17, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chathurani, P.; Weeratunga, P.; Deepika, S.; Lakshitha, N.; Rodrigo, C.; Rajapakse, S. Rational use of ultrasonography with triaging of patients to detect dengue plasma leakage in resource limited settings: a prospective cohort study. Trop Med Int Health 2021, 26, 993–1001. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, L.; Huang, X.; Luo, J.; Zhao, Y.; Hong, S.; Wang, X.; et al. Secondary cross infection with dengue virus serotype 2/3 aggravates vascular leakage in BALB/c mice. J Med Virol 2022, 94, 4338–4347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaagaard, M.D.; Oliveira, L.; Evangelista, M.V.P.; Wegener, A.; Holm, A.E.; Vestergaard, L.S.; et al. Frequency of pleural effusion in dengue patients by severity, age and imaging modality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis 2023, 23, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyama, H.; Chierakul, W.; Charunwatthana, P.; Sanguanwongse, N.; Phonrat, B.; Silachamroon, U.; et al. Lung Ultrasound Findings of Patients with Dengue Infection: A Prospective Observational Study. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2021, 105, 766–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, L.; Prieto, I.; Zuluaga, D.; Ropero, D.; Dewan, N.; Kirsch, J.D. Evaluation of remote radiologist interpreted point of care ultrasound for suspected dengue patients is a primary health care facility in Colombia. Infect Dis Poverty 2023, 12, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleeson, T.; Pagnarith, Y.; Habsreng, E.; Lindsay, R.; Hill, M.; Sanseverino, A.; et al. Dengue Management in Triage using Ultrasound in children from Cambodia: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Reg Health West Pac 2022, 19, 100371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewan, N.; Zuluaga, D.; Osorio, L.; Krienke, M.E.; Bakker, C.; Kirsch, J. Ultrasound in Dengue: A Scoping Review. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2021, 104, 826–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doriguetto, B.; Dalmo, D. Ultrasound Assessment of Hepatobiliary and Splenic Changes in Patients With Dengue and Warning Signs During the Acute and Recovery Phases. J Ultrasound Med 2019, 38, 2015–2024. [Google Scholar]

- Santhosh, V.R.; Patil, P.G.; Srinath, M.G.; Kumar, A.; Jain, A.; Archana, M. Sonography in the Diagnosis and Assessment of Dengue Fever. J Clin Imaging Sci 2014, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélard, S.; Tamarozzi, F.; Bustinduy, A.L.; Wallrauch, C.; Grobusch, M.P.; Kuhn, W.; et al. Point-of- Care Ultrasound Assessment of Tropical Infectious Diseases—A Review of Applications and Perspectives. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2016, 94, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, A.; Doniger, S.J. Point-of-Care Ultrasound for the Pediatric Hospitalist's Practice. Hosp Pediatr 2019, 9, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaminstein, D.; Kuhn, W.T.; Huang, D.; Burleson, S.L. Perspectives on Point-of-Care Ultrasound Use in Pediatric Tropical Infectious Disease. Pediatr Emerg Med J 2019, 20, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, C.D.; de Mel, S.; Shi, C.; Uvindu, B.; de Mel, P.; Shalindi, M.; et al. Admission ultrasonography as a predictive tool for thrombocytopenia and disease severity in dengue infection. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2021, 115, 1396–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Dengue: guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control, New edition; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- de Souza, L.J.; Alves, J.G.; Ribeiro, R.M.; Gicovate, C.; Bastos, D.A.; da Silva, E.W.; et al. Aminotransferase changes and acute hepatitis in patients with dengue fever: analysis of 1,585 cases. Braz J Infect Dis 2004, 8, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantillano, E.M.; Domínguez-Rojas, J.; Almazan, J.D.; Banegas, L.; Portillo, M.; Ponce, J. Proposed Protocol for the Focused Analysis of Dengue Fever by Serial Ultrasound in Pediatric Patients: The AEDES Protocol. Med Sci J Adv Resear 2025, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Parmar, J.; Mohan, C.; Kumar, G.P.; Vora, M. Ultrasound is Not Useful as a Screening Tool for Dengue Fever. Pol J Radiol 2017, 82, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanh, L.; Tat, D.; Ngoc, T.; Hoang-Thanh, H.; Thi-Hoai, T.; Ngoc, T.; et al. Pediatric Profound Dengue Shock Syndrome and Use of Point-of-Care Ultrasound During Mechanical Ventilation to Guide Treatment: Single-Center Retrospective Study, 2013–2021. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2024, 25, e177–e185. [Google Scholar]

| Sociodemographic variables | |

| Age (years) | |

| Mean ± standard deviation (X±SD) | 7.8±3.6 |

| Range | 0.6-14 |

| Age groups (n, %) | |

| Infants (6 months to 2 years old) | 11 (8.3) |

| Toddlers (>2 to 4 years old) | 28 (21.2) |

| Schoolchildren (5 to ≤12 years old) | 72 (54.6) |

| Adolescents (13 to ≤18 years old) | 21 (15.9) |

| Gender (n, %) | |

| Female | 63 (47.7) |

| Male | 69 (52.3) |

| Origin (n, %) | |

| Cali | 73 (56.2) |

| Valle del Cauca | 49 (37.7) |

| Outside Valle del Cauca | 8 (6.2) |

| Clinical variables | |

| Type of infection (n, %) | |

| Primary | 31 (23.5) |

| Secondary | 101 (76.5) |

| Nutritional status (n=76) | |

| According to Body Mass Index (n, %) | |

| Eutrophic | 41 (54.0) |

| Malnourished | 35 (46.0) |

| Symptoms (n, %) | |

| Abdominal pain | 104 (80.0) |

| Vomiting | 61 (50.0) |

| Epistaxis | 33 (26.6) |

| Diarrhea | 20 (16.7) |

| Hospital stay | |

| Mean ± standard deviation (X±SD) | 4.1±3.2 days |

| Prolonged hospital stay (>5 days) (n, %) | 38 (29.0) |

| Intensive Care Unit (n, %) | 33 (25.0) |

| Paraclinical variables | |

| Aminotransferases (X±SD) | |

| Aspartate aminotransferase IU/L | 271±530 |

| Alanine aminotransferase IU/L | 124±142 |

| Degree of aminotransferaseemia according to de Souza classification (n, %) | |

| A (normal) | 0 (0.0) |

| B (elevated between 1 to 3 times) | 19 (14.4) |

| C (elevated between >3 to 10 times) | 72 (54.6) |

| D (elevated >10 times) | 41 (31.1) |

| Albumin (n=97) | |

| Mean ± standard deviation (X±SD) | 3.31±0.59 g/dL |

| Hypoalbuminemia (<3.5 g/dL) (n, %) | 55 (56.7) |

| Mild hypoalbuminemia (3.0-3.5 g/dL) (n, %) | 27 (27.8) |

| Moderate hypoalbuminemia (2.5-3.0 g/dL) (n, %) | 18 (18.5) |

| Severe hypoalbuminemia (2.0-2.5 g/dL) (n, %) | 9 (9.2) |

| Critically low hypoalbuminemia (<2.0 g/dL) (n, %) | 1 (1.0) |

| Coagulation times (n=128) | |

| Prothrombin time (X±SD) | 11.2±1.1 seconds |

| Partial Thromboplastin Time (X±SD) | 43.4±9.7 seconds |

| International Normalized Ratio (X±SD) | 1.02±0.13 |

| Prolonged times (n, %) | 1 (0.8) |

| Platelets | |

| Mean ± standard deviation (X±SD) | 73.750±62.514/μL |

| Thrombocytopenia (<150.000/μL) (n, %) | 115 (87.1) |

| Mild thrombocytopenia (100.000-150.000/μL) (n, %) | 16 (12.1) |

| Moderate thrombocytopenia (50.000-99.999/μL) (n, %) | 36 (27.2) |

| Severe thrombocytopenia (<50.000/μL) (n, %) | 63 (47.7) |

| Leukocytes | |

| Mean ± standard deviation (X±SD) | 4903±3008/mm³ |

| Leukopenia (<4500/mm³) (n, %) | 72 (54.6) |

| Leukocytosis (>10000/mm³) (n, %) | 8 (6.1) |

| Therapeutic management (n, %) | |

| Intravenous albumin | 64 (48.5) |

| Requirement for blood products | 4 (3.0) |

| All | Dengue with warning signs | Severe Dengue | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=126 | n=123 (93.2) | n=9 (6.8) | ||

| Ascites | 110 (83.3) | 101 (82.1) | 9 (100.0) | 0.183 |

| Pleural effusion | 61 (46.2) | 56 (45.5) | 5 (55.6) | 0.405 |

| Hepatomegaly | 54 (40.9) | 51 (41.5) | 3 (33.3) | 0.457 |

| Thickened gallbladder | 52 (39.4) | 49 (39.8) | 3 (33.3) | 0.496 |

| Pericardial effusion | 4 (3.0) | 3 (2.4) | 1 (11.1) | 0.249 |

| Capillary leakage | OR | 95%CI | p | ||

| Yes 126 (95.4) |

No 6 (4.6) |

||||

| Age groups | |||||

| Infants | 10 (7.9) | 1 (16.7) | 0.43 | 0.04-22.39 | 0.4497 |

| Toddlers | 24 (19.1) | 4 (66.7) | 0.11 | 0.01-0.89 | 0.0053 |

| Schoolchildren-Adolescents | 92 (73.0) | 1 (16.7) | 13.52 | 1.41-646.51 | 0.0031 |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 61 (48.4) | 2 (33.3) | 1.00 | 0.4700 | |

| Male | 65 (51.6) | 4 (66.7) | 0.53 | 0.04-3.88 | |

| Origin | |||||

| Cali | 69 (55.7) | 4 (66.7) | 0.62 | 0.05-4.57 | 0.5952 |

| Valle del Cauca | 47 (37.9) | 2 (33.3) | 1.22 | 0.16-13.96 | 0.8215 |

| Outside Valle del Cauca | 8 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | n/a | ||

| Type of infection | |||||

| Primary | 29 (23.0) | 2 (33.3) | 1.00 | 0.5602 | |

| Secondary | 97 (77.0) | 4 (66.7) | 1.67 | 0.14-12.30 | |

| Dengue classification | |||||

| With warning signs | 117 (92.8) | 6 (100.0) |

0.649 |

||

| Severe | 9 (7.2) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Symptoms | |||||

| Abdominal pain | 100 (80.7) | 4 (66.7) | 2.08 | 0.17-15.42 | 0.4031 |

| Vomiting | 59 (50.0) | 2 (33.3) | 1.00 | 0.07-14.21 | 1.00 |

| Hospital stay | 4.0±3.2 | 5.5±2.7 | 0.2614 | ||

| Prolonged hospital stay | 35 (28.0) | 3 (50.0) | 0.38 | 0.05-3.06 | 0.2461 |

| Intensive Care Unit | 32 (25.4) | 1 (16.7) | 1.70 | 0.18-82.97 | 0.6295 |

| Paraclinical variables | |||||

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 109 (86.5) | 3 (50.0) | n/a | ||

| Alanine aminotransferase | 116 (92.1) | 3 (50.0) | 11.60 | 1.32-94.82 | 0.0007 |

| Degree of aminotransferaseemia according to de Souza classification | |||||

| A | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | n/a | ||

| B | 16 (12.7) | 3 (50.0) | 0.14 | 0.01-1.20 | 0.0110 |

| C+D | 110 (87.3) | 3 (50.0) | 6.87 | 0.82-54.59 | 0.0110 |

| Albumin (X±SD) | 3.31±0.58 | 3.17±0.74 | 0.6408 | ||

| Hypoalbuminemia | 53 (56.7) | 2 (50.0) | 1.32 | 0.09-18.95 | 0.7824 |

| Mild hypoalbuminemia | 26 (49.0) | 1 (50.0) | 1.30 | 0.06-79.59 | 0.8334 |

| Moderate hypoalbuminemia | 18 (33.9) | 0 (0.0) | n/a | ||

| Severe hypoalbuminemia | 8 (15.1) | 1 (50.0) | 0.40 | 0.01-26.51 | 0.4626 |

| Critically low hypoalbuminemia | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | n/a | ||

| Platelets (X±SD) | 71.666±60.897/μL | 117.500±85.289/μL | 0.0793 | ||

| Thrombocytopenia | 110 (87.3) | 5 (83.3) | 1.37 | 0.02-13.45 | 0.7768 |

| Mild thrombocytopenia | 14 (12.7) | 2 (40.0) | 0.21 | 0.02-2.88 | 0.0848 |

| Moderate thrombocytopenia | 34 (30.9) | 2 (40.0) | 0.67 | 0.07-8.40 | 0.6681 |

| Severe thrombocytopenia | 62 (56.4) | 1 (20.0) | 5.16 | 0.48-258.42 | 0.1101 |

| Leukocytes (X±SD) | 4881±3046 | 5358±2199 | 0.7058 | ||

| Leukopenia | 69 (54.8) | 3 (50.0) | 1.21 | 0.15-9.37 | 0.8190 |

| Leukocytosis | 8 (6.4) | 0 (0.0) | n/a | ||

| Imaging variables | |||||

| Pleural effusion on chest X-ray | 84 (66.6) | 2 (33.3) | 4.09 | 0.55-46.49 | 0.0879 |

| Time from symptom onset to ultrasound (X±SD) | 6.0+/-2.0 | 6.0+/-2.7 | 1.0000 | ||

| Delay in performing the ultrasound | 50 (39.7) | 3 (50.0) | 1.01 | 0.08-9.31 | 0.9915 |

| Therapeutic management | |||||

| Intravenous albumin | 63 (50.0) | 1 (16.7) | 5.0 | 0.53-240.12 | 0.1104 |

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| School-age/adolescent | + | - | - |

| Alanine aminotransferase | + | + | + |

| Grade C-D of aminotransferaseemia according to the de Souza classification | + | + | + |

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary infection | + | + | - |

| Abdominal pain | + | + | + |

| Alanine aminotransferase | + | + | + |

| Grade of aminotransferaseemia according to de Souza classification | C | D | D |

| Hypoalbuminemia | Mild | Mild | Mild |

| Severe thrombocytopenia | Mild | + | + |

| Pleural effusion on X-ray | + | - | + |

| Requirement for intravenous albumin | + | - | + |

| Requirement for blood products | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).