1. Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is a leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide, with a 5-year survival rate of only 11% in the United States [

1]. The lethality of this disease underscores the importance of early and accurate diagnosis. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle biopsy (EUS-FNB) has become a standard method for obtaining tissue from solid pancreatic masses (SPMs), offering high diagnostic accuracy with minimal invasiveness. Traditionally, EUS-guided tissue acquisition (EUS-TA) relied on fine-needle aspiration (FNA) in conjunction with rapid on-site cytopathologic evaluation (ROSE), which allows real-time assessment of specimen adequacy and guides the number of needle passes. However, the routine use of ROSE has declined in many institutions due to its resource-intensive nature and limited availability of cytopathologists. In response, the emergence of core biopsy techniques using novel needle designs—such as Franseen-tip or fork-tip needles—has significantly improved tissue yield and histologic quality [

2], potentially obviating the need for ROSE. Recent systematic reviews have reported that these contemporary FNB needles can achieve diagnostic accuracy comparable to or exceeding that of FNA with ROSE [

3], particularly when a minimum of two to three passes is performed. Chalhoub et al. found that while three passes improved diagnostic parameters over one or two, additional passes beyond the third conferred minimal benefit [

4]. Notably, their data supported that two passes using modern Franseen or fork-tip needles were sufficient to meet American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) and American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) benchmarks for diagnostic accuracy (≥70%) and tissue adequacy (≥85%) [

5].

In parallel, macroscopic on-site evaluation (MOSE), where visible white core length is used as a surrogate for histologic adequacy and gross-eyed method (white core tissue seen) have been proposed as practical alternatives to ROSE, particularly in resource-limited settings. Touch imprint cytology (TIC) also demonstrated comparable diagnostic performance to histology, further supporting the notion that non-ROSE methods can maintain diagnostic integrity [

6].

Despite these developments, the optimal number of needle passes for EUS-FNB in the absence of ROSE, particularly when relying on gross-eyed methods, remains poorly defined in real-world clinical settings. Moreover, there is a paucity of studies evaluating this approach in dedicated cohorts of pancreatic malignancy.

This study aimed to assess the diagnostic accuracy, diagnostic yield rate, and tissue adequacy of EUS-FNB in patients with pancreatic malignancy using a gross-eyed evaluation of tissue quality with fanning technique and less puncture numbers (2 instead of 3). Since less puncture numbers could be safer and have less side effects. The optimal numbers to balance diagnosis and side effects are important. Given emerging concerns regarding needle tract seeding after EUS-guided tissue acquisition [

7], particularly in patients undergoing surgical resection, minimizing unnecessary passes has become increasingly important.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Patient Selection

This retrospective, single-center study was conducted at Tri-Service General Hospital in Taiwan, a tertiary referral hospital, from January 2022 to December 2024. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB approval number: A202405188). Informed consent was waived given the retrospective nature of the research. Patients were included if they were ≥18 years of age and had definite diagnosis of pancreatic malignancy. Exclusion criteria were: (1) diagnosis made by non-EUS modalities, including surgical pathology or CT-guided biopsy, (2) diagnosis made by lesions of metastatic sites other than pancreas, or (3) EUS-FNB procedures with fewer than three needle passes.

EUS-FNB Procedure and MOSE Protocol

All EUS-FNB procedures were performed using a linear-array echoendoscope (GF-UCT260; Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan) with either a 22-gauge or 19-gauge needle. Fanning technique was routinely used in every puncture and procedures were conducted under conscious sedation. The needle choice and suction technique (slow-pull or standard syringe suction) were determined at the discretion of the endosonographer. Rapid on-site evaluation (ROSE) was not available during the study period. Instead, specimen adequacy was assessed intra-procedurally using gross-eyed method. After each pass, the aspirated specimen was expelled onto a piece of filter paper using the stylet. Gross-eyed evaluation was performed by the endoscopist, who visually inspected the sample for whitish, worm-like tissue cores. Whether the initial two passes yielded visible core or were composed predominantly of blood and clot, a third pass was routinely performed. No additional needle passes were made beyond the third. All samples were immediately fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for histologic processing.

Final Diagnosis and Histologic Confirmation

The final diagnosis of malignancy was confirmed by histopathology. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, neuroendocrine tumors, GISTs and pancreatic carcinomas were all classified as malignant. Cytologic diagnoses categorized as “malignant” or “suspicious for malignancy” were considered positive.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was diagnostic accuracy, defined as the proportion of cases in which the EUS-FNB diagnosis was concordant with the final surgical pathology. Secondary outcomes included tissue adequacy, defined as the presence of sufficient cellular or histologic material on histopathology to allow for a pathologic interpretation, regardless of whether a definitive diagnosis was achieved and diagnostic yield rate, defined as the proportion of cases in which EUS-FNB yielded a definitive diagnosis of malignancy or benignity on pathology. Cases with “atypical,” or “non-diagnostic” reports were not counted as diagnostic.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD). Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages, and comparisons were performed using Chi-square test. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

Patient Characteristics

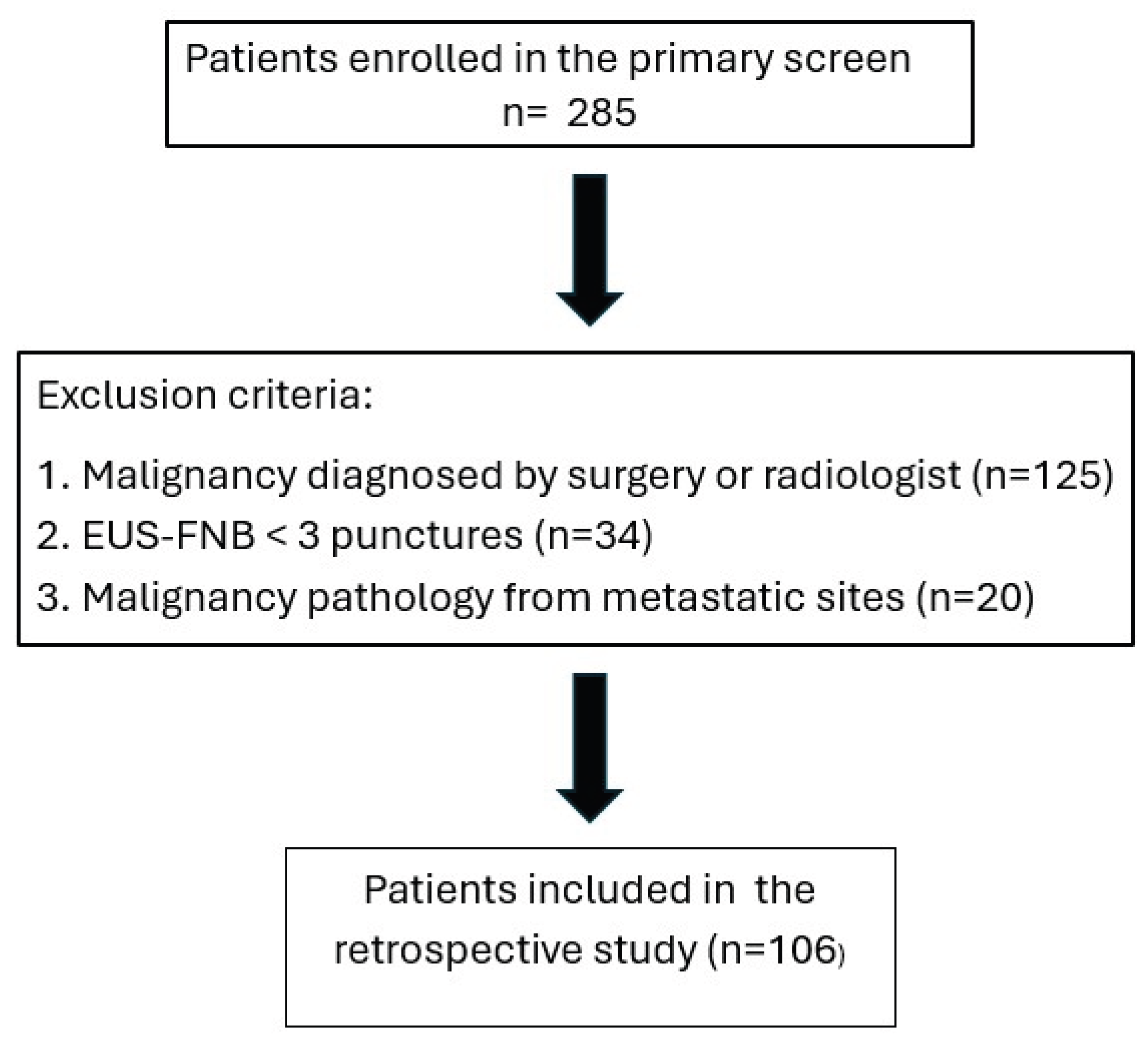

A total of 285 patients were diagnosed of pancreatic malignancy during the study period. After applying exclusion criteria—diagnosis established by non EUS modalities (n=125), EUS-FNB procedure fewer than three needle passes (n=34), or diagnosis based on metastatic lesion (n=20)—106 patients were included in the final analysis (

Figure 1).

The mean age of enrolled patients was 68.8 ± 10.2 years, and 51.9% were male. The majority of patients (83%) were diagnosed with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), followed by neuroendocrine tumors (9.4%), other neoplasms (5.7%) and carcinoma (1.9%). The PDAC group had a mean age of 68.8 ± 10.2 years, with 48.9% being male. Detailed demographics and clinical features, including smoking, alcohol use, diabetes, viral hepatitis status, tumor location, disease stage and tumor size, are summarized in

Table 1

Tumors were most commonly located in the pancreatic head (n=38), followed by tail (n=25), body (n=24), uncinate process (n=14) and neck (n=6). Disease stage distribution was: Stage I (n=16), Stage II (n=13), Stage III (n=16), and Stage IV (n=61). Lesions ≥20 mm accounted for 93.4% (n=99) of cases.

Tissue Adequacy

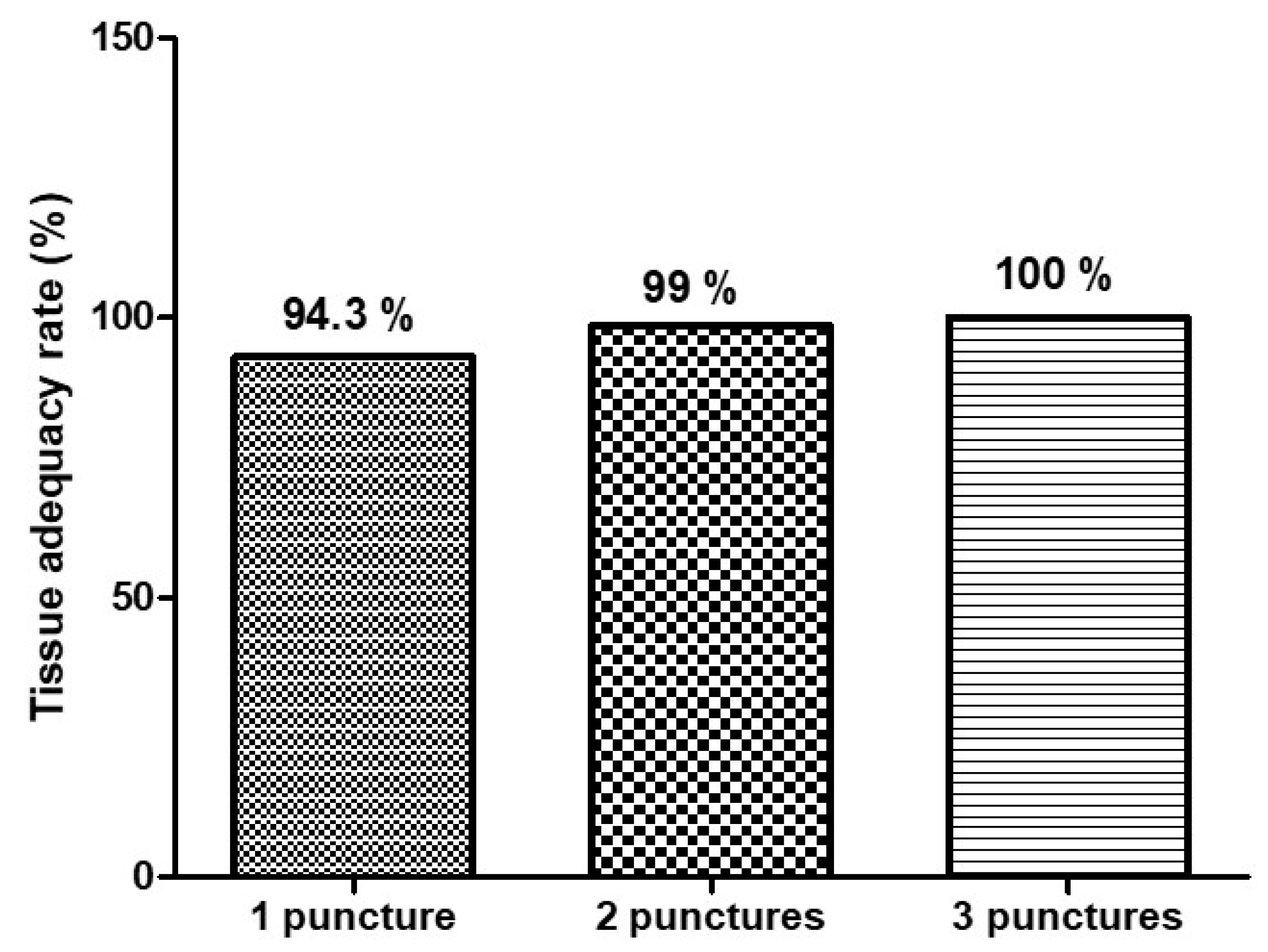

Tissue adequacy, defined by histologic assessment of samples containing sufficient material for diagnosis, was high across all groups:

1 pass: 94.3%

2 passes: 99%

3 passes: 100%

Although adequacy increased incrementally, all groups exceeded the benchmark of 85% proposed by ASGE for EUS-guided sampling quality. The majority of patients reached tissue adequacy within two passes based on gross-eyed evaluation (

Figure 3), supporting the role of gross-eyed method in reducing unnecessary punctures.

Diagnostic Yield Rate

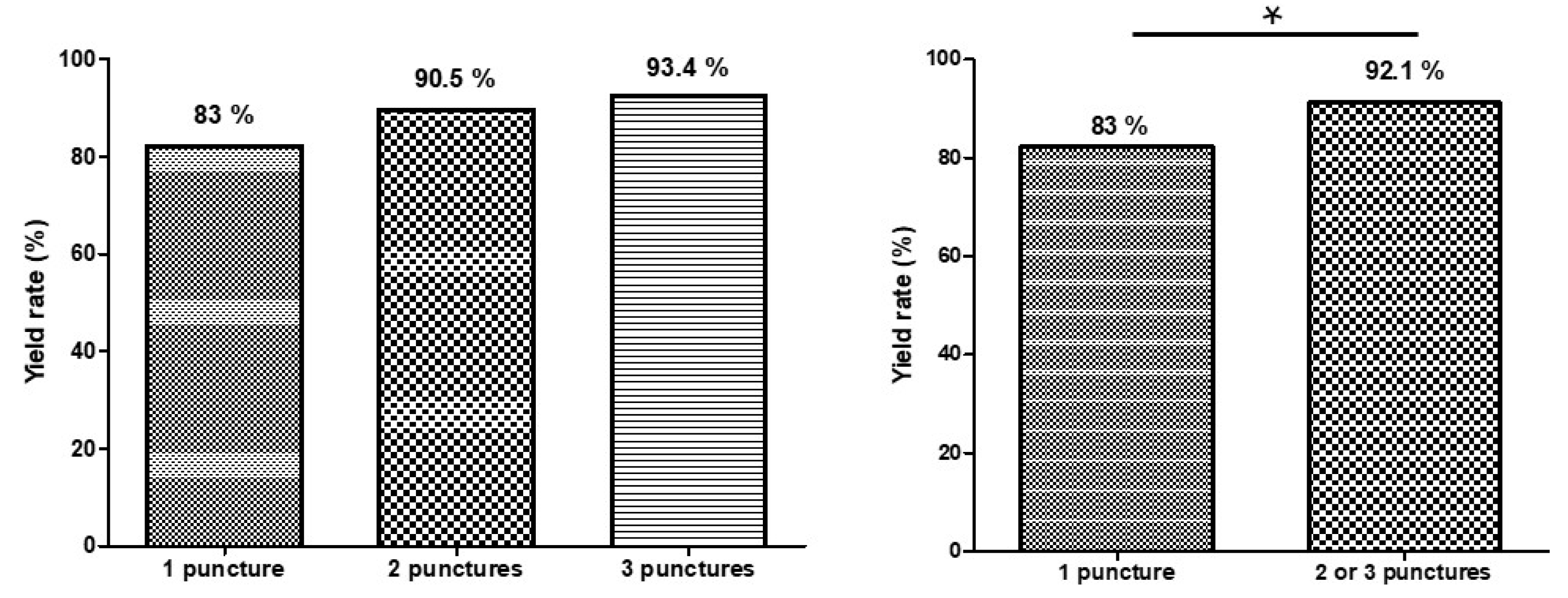

The overall diagnostic yield—defined as the proportion of cases yielding a definitive benign or malignant diagnosis—mirrored the accuracy trend:

1 pass: 83%

2 passes: 90.5%

3 passes: 93.4%

A small subset of cases remained “non-diagnostic” or “atypical” despite adequate tissue, highlighting the interpretative limitations of cytology alone. The yield rate improved significantly from one pass to two or three passes (

Figure 4), which aligns with prior randomized trials comparing EUS-FNB with and without ROSE [

8].

(A) Comparison of diagnostic yield rate by number of needle passes

(B) Comparison of diagnostic yield rate between one pass and two or three passes

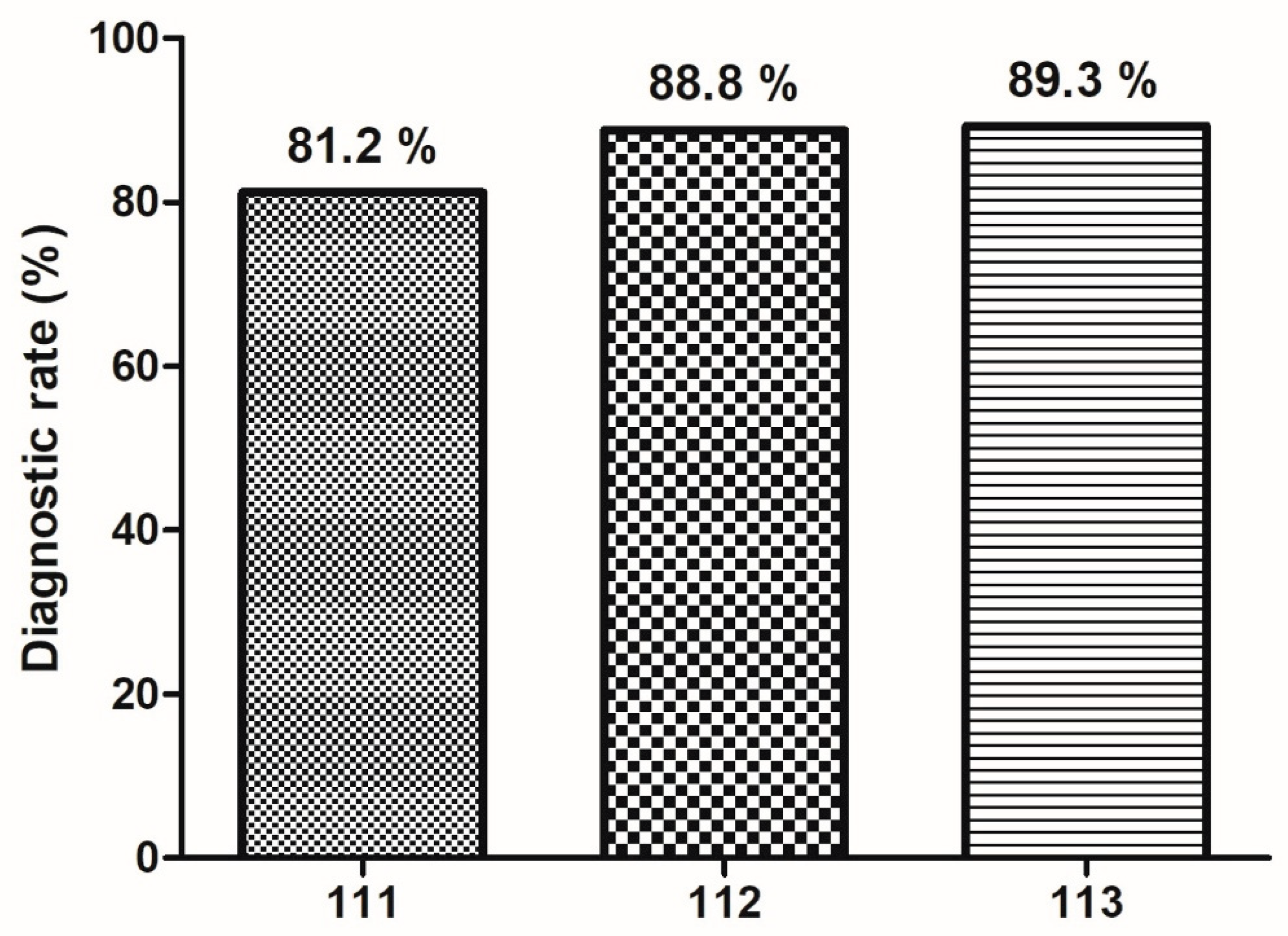

Annual Trends in Diagnostic Accuracy of EUS-FNB by Number of Needle Passes

Diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNB has demonstrated a progressive increase across three years, irrespective of the number of needle passes. Diagnostic rate improved from 81.2% to 89.3% overally (

Figure 5). This upward trend suggests enhanced procedural performance over time.

Univariable Analysis of Misdiagnosis at One Pass

No significant association was found between misdiagnosis at one pass and tumor location (head vs. body/tail, p=0.83), tumor size (≥20 mm vs. <20 mm, p=0.46), or needle type (19G vs. 22G, p=0.31). Details of factors associated with misdiagnosis at one puncture are summarized in

Table 2.

Safety and Procedural Metrics

No adverse events such as pancreatitis, bleeding, or infection were reported in the 106 analyzed cases. All procedures were completed without interruption, and gross-eyed method was feasible in 100% of cases.

4. Discussion

It has been known that EUS-FNB with fanning technique is superior to standard approach to get tissue for diagnosis. [

3]. In our previous experience, even without the use of MOSE, the diagnostic rate is still high. To address this issue, all procedure was done by fanning technique and we evaluated the sample quality by gross-eye method in the absence of ROSE and MOSE.

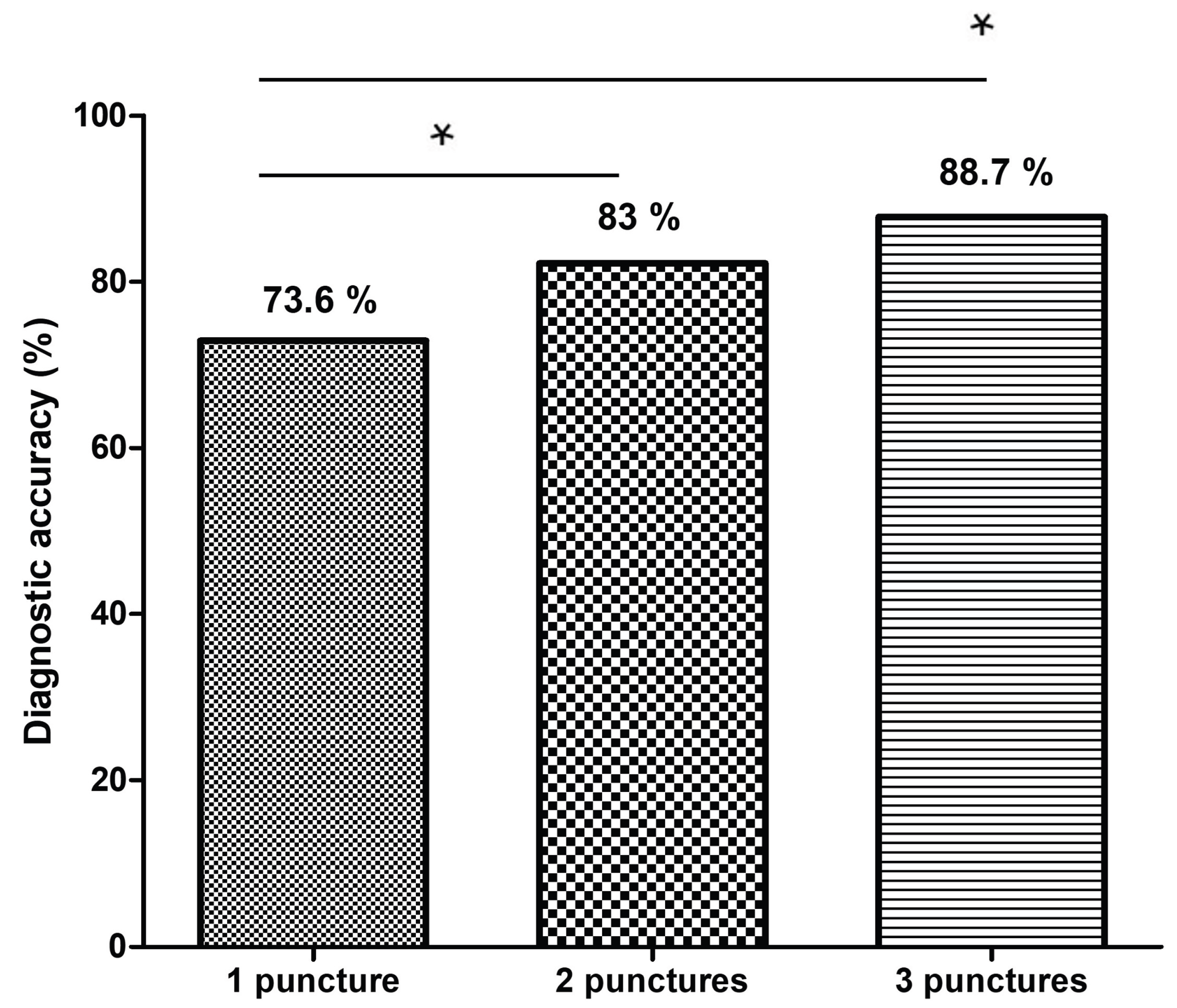

The diagnostic accuracy improved from 73.6% with one pass to 83% with two passes, and reached 88.7% with three passes. This plateau beyond the second pass is consistent with prior literature [

4]. Chalhoub et al. reported a pooled diagnostic accuracy of 91.5% for pancreatic lesions with three or more passes, but also found that modern FNB needles often achieved benchmark tissue adequacy (≥85%) with just two passes [

4]. Our findings similarly suggest that increasing the number of passes beyond two may not meaningfully improve diagnostic outcomes when a gross-eyed method is employed to guide tissue acquisition.

In line with this, a longitudinal analysis of our institutional data revealed a consistent year-over-year improvement in diagnostic accuracy across all passes. These trends suggest that, beyond procedural standardization, accumulated operator experience, refined tissue handling techniques, and possibly improvements in needle design or gross-eyed evaulation all contribute to better diagnostic outcomes over time.

Importantly, tissue adequacy in our cohort was high across all groups (94.3% for one pass, 99% for two, and 100% for three passes), exceeding ASGE thresholds and aligning with recent randomized controlled trials evaluating MOSE. Mangiavillano et al. demonstrated in a large multicenter RCT that EUS-FNB with MOSE had non-inferior diagnostic accuracy compared to conventional three-pass FNB [

9], while significantly reducing the number of required punctures. Our study builds on this evidence by showing that gross-eyed guided two-pass EUS-FNB is not only diagnostically sufficient, but also feasible without ROSE.

The gross-eyed technique we employed relies on real-time visual inspection of visible white core fragments. This method is simple, cost-effective, and well-suited to centers lacking cytopathology support. While the presence of visible core does not always guarantee diagnostic yield, our findings indicate that its use as a surrogate for tissue adequacy was highly reliable.

Furthermore, our diagnostic yield (proportion of cases with definitive malignant or benign diagnosis) closely mirrored diagnostic accuracy, reaffirming the utility of two passes in high-performing centers with experienced operators. The minimal rate of inadequate samples or indeterminate diagnoses also supports the robustness of the gross-eyed assessment in determining when to cease sampling.

The safety profile of our cohort was favorable, with no reported adverse events. This is particularly relevant in the context of pass minimization. Excessive punctures have been associated with increased complication risk, including bleeding and post-procedural pancreatitis. Our strategy minimizes unnecessary needle passes and aligns with principles of patient safety and procedural efficiency.

From a broader perspective, our use of gross-eyed assessment gains additional validation from a recent study by Lin et al., which investigated the biological content of red material obtained during EUS-FNB [

10]. While traditional MOSE emphasizes measurement of white core length to assess specimen adequacy [

11,

12], Lin’s study demonstrated that red material—often abundant but traditionally disregarded—contains a significantly higher amount of tumor DNA and shows high concordance in K-ras mutation profiles compared to white cores. These findings suggest that even when white cores are small or not clearly visible, red material should not be dismissed as merely blood contamination but rather recognized as a potentially rich source of tumor content, particularly for molecular analysis. Such results support the validity of the gross-eyed method, which does not require millimeter-scale measurements of white core length but rather depends on visual identification of tissue. This approach can help minimize the need for repeated needle passes and improve procedural throughput.

Furthermore, minimizing the number of passes aligns with safety considerations. Needle tract seeding, while rare, is an increasingly recognized risk of EUS-guided procedures. Studies have reported cases of tumor seeeding along the needle tract, particularly in patients undergoing distal pancreatectomy or subsequent curative surgery [

7]. By establishing a two-pass protocol with reliable gross-eyed assessment, clinicians can balance diagnostic accuracy and tissue adequacy while mitigating procedural risks.

This study has several limitations. First, it was a retrospective, single-center analysis, which may limit the generalizability of findings. Second, the gross-eyed assessment was not validated against objective core length measurements or histologic core content, although adequacy was confirmed post hoc by pathology. Third, inter-operator variability in assessing macroscopic adequacy was not formally analyzed. Lastly, we excluded patients with fewer than three needle passes, potentially underestimating the diagnostic yield of single-pass FNB in truly minimal puncture strategies.

5. Conclusions

In patients undergoing EUS-FNB with fanning technique for pancreatic malignancy without ROSE, two needle passes guided by gross-eyed evaluation provide optimal diagnostic accuracy. Additional passes beyond two confer minimal benefits and may be unnecessary in most clinical settings. The gross-eyed method is a practical and effective alternative to ROSE and supports a simplified, cost-effective, and safe strategy for tissue acquisition in pancreatic malignancy diagnosis.

Author Contributions

TJ-C and HW-C; methodology, HW-C; software and validation, TJ-C and HW-C; formal analysis, TJ-C; data curation, TJ-C; writing—original draft preparation, HW-C and JC-Lin; writing—review and editing, HW-C and JC-Lin; supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Approval of the research protocol by an Institutional Reviewer Board: Tri-Service General Hospital institutional review board (IRB approval number: A202405188, approval date 16 January 2025) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to retrospective study design.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to restrictions of patient privacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contribution provided by the Evidence-based Practice and Policymaking Committee, Tri-Service General Hospital, National Defense Medical Center, Taipei, Taiwan.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EUS-FNB |

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle biopsy |

| SPMs |

Solid pancreatic masses |

| ROSE |

Rapid on-site cytopathologic evaluation |

| PDAC |

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma |

| MOSE |

Macroscopic on-site evaluation |

| TIC |

Touch imprint cytology |

References

- Dudley, B; Brand, RE. Pancreatic Cancer Surveillance and Novel Strategies for Screening. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2022, 32(1), 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkolfakis, P; Crinò, SF; Tziatzios, G; Ramai, D; Papaefthymiou, A; Papanikolaou, I; et al. Comparative diagnostic performance of end-cutting fine-needle biopsy needles for EUS tissue sampling of solid pancreatic masses: A network meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc 2022, 95, 1067–77.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bang, J Y; Magee, S H; Ramesh, J; Trevino, J M; Varadarajulu, S. Randomized trial comparing fanning with standard technique for endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of solid pancreatic mass lesions. Endoscopy 2013, 45(6), 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, YI; Chatterjee, A; Berger, R; Kanber, Y; Wyse, J; Lam, E; et al. EUS-guided fine-needle biopsy versus aspiration with ROSE in pancreatic lesions: A multicenter randomized trial. Endoscopy 2022, 54, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalhoub, JM; Hawa, F; GranthamT; Lester, J; Carpenter, ES; Mendoza-Ladd, A; et al. Effect of the number of passes on diagnostic performance of EUS fine-needle biopsy of solid pancreatic masses: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc 2024, 100(4), 595–604. e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wani, S; Wallace, MB; Cohen, J; Pike, IM; Adler, DG; Kochman, ML; et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute. Quality indicators for EUS. Gastrointest Endosc 2015, 81, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crinò, SF; Larghi, A; Bernardoni, L; Parisi, A; Frulloni, L; Gabbrielli, A; et al. Touch imprint cytology on endoscopic ultrasound fine-needle biopsy provides comparable sample quality and diagnostic yield to standard endoscopic ultrasound fine-needle aspiration specimens in the evaluation of solid pancreatic lesions. Cytopathology 2019, 30(2), 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakatsubo, R; Yamamoto, K; Itoi, T; Sofuni, A; Tsuchiya, T; Ishii, K; et al. Histopathological evaluation of needle tract seeding caused by EUS-fine-needle biopsy based on resected specimens from patients with solid pancreatic masses: An analysis of 73 consecutive cases. Endosc Ultrasound 2021, 10, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Crinò, SF; Mitri, RD; Nguyen, NQ; Tarantino, I; Nucci, GD; Deprez, PH; et al. Endoscopic Ultrasound–guided Fine-needle Biopsy With or Without Rapid On-site Evaluation for Diagnosis of Solid Pancreatic Lesions: A Randomized Controlled Non-Inferiority Trial. Gastroenterology 2021, 161, 899–909. e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangiavillano, B; Crinò, SF; Facciorusso, A; Matteo, FD; Barbera, C; Larghi, A; et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle biopsy with or without macroscopic on-site evaluation: A randomized controlled noninferiority trial. Endoscopy 2023, 55, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, MY; Su, YY; Yu, YT; Huang, CJ; Sheu, BS; Chang, WL; et al. Investigation into the content of red material in EUS-guided pancreatic cancer biopsies. Gastrointest Endosc 2023, 97, 1083–1091.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneko, J; Ishiwatari, H; Sasaki, K; Yasuda, I; Takahashi, K; Imura, J; et al. Macroscopic visible core length can predict the histological sample quantity in endoscopic ultrasound-guided tissue acquisition: Multicenter prospective study. Dig Endosc 2022, 34(3), 622–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stigliano, S; Balassone, V; Biasutto, D; Covotta, F; Signoretti, M; Matteo, FMD; et al. Accuracy of visual on-site evaluation (Vose) In predicting the adequacy of EUS-guided fine needle biopsy: A single center prospective study. Pancreatology 2021, 21, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |